Abstract

Financial risk early warning systems are essential for proactive risk management in volatile markets, particularly for emerging economies such as China. This study develops a hybrid deep learning model integrating Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs) to enhance the accuracy and robustness of financial risk prediction. Using firm-level quarterly financial data from Chinese listed companies, the proposed model is benchmarked against standalone CNN, LSTM, and GRU architectures. Experimental results show that the hybrid CNN–LSTM–GRU model achieves superior performance across all evaluation metrics, with prediction accuracy reaching 93.5%, precision reaching 92.2%, recall reaching 91.8%, and F1-score reaching 92.0%, significantly outperforming individual models. Moreover, the hybrid approach demonstrates faster convergence than LSTM and improved class balance compared to CNN and GRU, reducing false negatives for high-risk firms—a critical aspect for early intervention. These findings highlight the hybrid model’s robustness and real-world applicability, offering regulators, investors, and policymakers a reliable tool for timely financial risk detection and informed decision-making. By combining high predictive power with computational efficiency, the proposed system provides a practical framework for strengthening financial stability in emerging and dynamic markets.

1. Introduction

Financial risk management has become increasingly critical amid heightened global volatility and economic uncertainty. Recent shocks from the COVID-19 pandemic, commodity price swings, and geopolitical tensions have increased funding cost volatility, supply disruptions, and margin pressure for firms worldwide Agyapong (2024); Financial Stability Board (2022); World Bank Group (2024). Internally, companies may compound these external pressures through poor investment decisions, leverage mismanagement, weak governance, or liquidity mismatches, all of which elevate the probability of financial distress Laeven and Valencia (2020). If such risks are not identified and mitigated early, even solvent firms can rapidly spiral into distress or failure during periods of market stress Reinhart and Rogoff (2009). It is therefore essential to develop robust financial risk-monitoring and early warning systems (EWSs) that alert decision-makers before vulnerabilities crystallize into crises. Historical evidence shows that financial crises impose large economic, fiscal, and social costs and are often preceded by extended periods of credit expansion, asset price misalignment, or other abnormal macro-financial movements Kaminsky et al. (1998).

In response, researchers and policymakers have long sought to construct quantitative EWS frameworks capable of signaling impending episodes ranging from firm-level bankruptcy to banking, currency, or broader financial crises Chohan et al. (2025); Drehmann et al. (2014). Conceptually, an early warning model functions as a monitoring and alerting mechanism that maps patterns in financial, market, and macroeconomic data into probabilistic assessments of distress or regime change Altman (1968). Traditional EWS approaches relied heavily on accounting-based financial statement ratios to evaluate firm health—an approach dating back to classic work on ratio analysis and default prediction Beaver (1966). Over time, research progressed from univariate ratios to discriminant analysis, logit/probit models, survival/hazard models, and multi-indicator signaling frameworks used in macroprudential surveillance Ohlson (1980).

In the past decade, artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have opened new frontiers in financial risk prediction by learning complex, nonlinear interactions that traditional parametric models often miss. Studies show that ML approaches—such as support vector machines, boosting, bagging, and Random Forests—can materially improve bankruptcy classification accuracy relative to logistic regression and other statistical benchmarks Butt (2025); Hosaka (2019). Deep learning has further extended these gains: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have successfully extracted predictive structure from transformed financial ratio “images”, while recurrent architectures such as Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) networks capture temporal dependencies critical for dynamic risk assessment Hosaka (2019).

Despite these advances, important research gaps remain in the context of China’s rapidly evolving financial markets. The number of Chinese listed companies continues to increase, underscoring the fundamental growth of the market Li et al. (2023). However, empirical, data-driven EWS studies for this sector remain limited; much of the literature highlights credit risk issues and widespread corporate indebtedness and defaults. Moreover, many existing studies remain descriptive or regulatory in focus rather than predictive Li et al. (2023); Song et al. (2023). A further limitation is the predominant reliance on low-frequency or annual data, which may fail to capture the fast-moving liquidity and credit conditions of digital financial activity Song et al. (2023). Additionally, the failure of numerous peer-to-peer (P2P) lending platforms due to fraud and systemic weaknesses has further exposed deficiencies in the risk-monitoring infrastructure Song et al. (2023).

To address these gaps, this study develops a deep learning-based financial risk early warning framework tailored to China’s financial markets, with particular relevance for digitally enabled and fast-moving segments. Further, unlike most studies relying solely on annual financial statements, our dataset leverages quarterly firm-level financial indicators. While not as granular as intraday or daily data, quarterly reporting represents higher-frequency information relative to annual data, enabling more timely early warning signals for financial risk detection. We focus on three neural network families suited to structured data: Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). We further propose a hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU architecture that integrates local feature extraction with both short- and long-horizon temporal learning to improve early warning performance. To our knowledge, few studies have empirically evaluated such hybrid deep learning models for financial risk early warning in the Chinese context using granular, higher-frequency inputs Song et al. (2023). Our research is guided by three questions:

- Do deep learning models (LSTM, GRU, and CNN) outperform traditional risk prediction approaches in China?

- Does a hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU architecture provide more reliable and timely early warnings than standalone models?

- How can improved model accuracy translate into actionable benefits for financial stability, regulatory oversight, and risk management?

This study makes four key contributions:

- It introduces and empirically tests a hybrid deep learning framework for financial risk early warning in a data-rich but risk-intensive emerging market.

- It demonstrates the value of incorporating higher-frequency firm-level and market-based indicators for timely signal detection.

- It provides evidence relevant to China’s financial ecosystem, offering practical implications for regulatory and institutional stakeholders.

- It contributes to the literature on financial distress prediction by showing how deep learning can be integrated into early warning workflows for proactive intervention.

2. Literature Review

To position our contribution, we review the evolution of financial risk early warning systems (EWSs) across three strands: (i) machine learning (non-deep) approaches, (ii) deep learning and hybrid neural architectures, and (iii) China-specific studies. Each strand ends with an analytical summary table. We then close with a brief gap analysis that motivates our hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU design.

2.1. Machine Learning Approaches

Classical statistical EWS models-discriminant analysis, logit/probit, survival models, and signaling frameworks struggle with nonlinearities and complex interactions Altman (1968); Ohlson (1980). Machine learning (ML) methods such as Support Vector Machines (SVMs), decision trees, and ensemble learners (e.g., Random Forests, boosting, bagging) have been shown to outperform these classical baselines in many settings by flexibly modeling such nonlinear structures.

Researchers in Barboza et al. (2017) reported that ensemble models achieved accuracies up to 87%, substantially higher than traditional methods. In a macroprudential context, Alessi and Detken (2018) demonstrated that Random Forests can effectively identify excessive credit growth and leverage associated with systemic risk in Europe. However, the authors in Beutel et al. (2019) cautioned that complex ML models may overfit and that, in some out-of-sample settings, simpler (e.g., logit) models can still dominate. Recent work has also emphasized interpretability: Tran et al. (2022) integrated SHAP (Shapley Additive Explanations) to enhance transparency in financial distress prediction for Vietnamese firms.

2.2. Deep Learning and Hybrid Models

Deep learning (DL) has further advanced EWS by capturing high-dimensional, nonlinear, and temporal dependencies that even flexible ML models may miss. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have been applied to transformed financial ratios (e.g., images), delivering significant accuracy gains in bankruptcy prediction Hosaka (2019). Recurrent architectures—Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) and Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs)—address vanishing/exploding gradients and can retain temporal structure crucial for financial time series Cho et al. (2014); Greff et al. (2016); Hochreiter and Schmidhuber (1997); Staudemeyer and Morris (2019); Yu et al. (2019).

Attention mechanisms and hybrid pipelines are increasingly popular. IN Ouyang et al. (2021) employed an Attention-LSTM with mixed numeric and text features to warn about systemic risk in China’s financial markets, outperforming conventional LSTMs. Authors in Chen and Long (2023) proposed FA-PSO-LSTM (factor analysis + particle swarm optimization to tune LSTM), reporting improved accuracy and robustness. More broadly, hybrid models are motivated by the intuition that CNNs capture local/short-term patterns, LSTMs have long-term dependencies, and GRUs efficiently handle medium-term dynamics—suggesting potential complementarities that can be exploited for EWS.

2.3. China-Specific AI-Based EWS Research

China’s rapidly digitizing and expanding financial landscape has prompted a growing body of AI-enabled EWS research, but most studies remain constrained to specific sectors, use low-frequency indicators, or emphasize descriptive/regulatory insights over predictive performance.

Researchers in Song et al. (2023) combined K-means clustering and a backpropagation (BP) neural network to classify 136 fintech firms into risk classes, achieving >99% accuracy. Authors in Zhao et al. (2022) built a BP neural network to warn of systemic risks from local government implicit debt, attaining low training error. researchers in Metawa and Metawa (2021) proposed a decision tree-based EWS for internet finance risk, achieving ∼90% accuracy. Meanwhile, authors in Li et al. (2023) designed a CNN-LSTM with attention for listed company credit risk, demonstrating the promise of hybrid DL architectures in China’s market. However, these studies generally underutilize higher-frequency data and often do not exploit the complementary strengths of multiple DL families in a single unified framework. Table 1 summarizes all these models.

Table 1.

AI-based EWS studies in the Chinese financial market.

2.4. Gap and Research Positioning

While (i) ML methods outperform traditional econometric baselines and (ii) DL and hybrid DL models show strong potential for financial EWS, important gaps remain in the Chinese context:

- Many studies rely on annual or other low-frequency variables, missing the benefits of quarterly or more granular datasets that can better capture firm-level financial dynamics Song et al. (2023).

- Few works jointly exploit CNN (local feature extraction), LSTM (long-term memory), and GRU (computationally efficient short-/medium-term capture) within a unified EWS pipeline tailored to China.

- There is limited evidence translating improved predictive accuracy into concrete early warning and supervisory utilities for Chinese regulators and financial institutions.

We address these gaps by proposing and empirically testing a hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU architecture on granular, higher-frequency inputs from China’s financial markets, and by benchmarking it against its single-model counterparts. Our findings aim to inform both the academic literature on financial distress prediction and the practical design of deployable early warning tools in China.

2.5. Our Positioning and Contribution

Our research builds on and extends these prior studies in three key ways:

- We use quarterly firm-level financial data, which provides higher-frequency information relative to annual reporting typically used in financial risk prediction studies. This improves the granularity and timeliness of early warning signals compared to annual datasets.

- We propose a hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU architecture, combining the strengths of spatial pattern recognition (CNN), long-term memory (LSTM), and efficient sequence learning (GRU). To the best of our knowledge, few empirical studies in China have implemented this particular hybrid architecture.

- Our empirical evaluation benchmarks the hybrid model against standalone CNN, LSTM, and GRU models, providing robust evidence of its superiority across accuracy, convergence, and class balance metrics.

These enhancements are particularly relevant for China’s fast-evolving financial landscape, where real-time risk detection, digital finance oversight, and proactive regulatory tools are becoming increasingly vital. Our work contributes both to the global academic literature on financial EWS using deep learning and to the localized development of actionable AI solutions for China’s regulatory and financial ecosystem.

3. Methods

This section outlines the methodology of the study, describing each deep learning architecture and the proposed hybrid model used for financial risk early warning in China’s listed companies.

3.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are a class of neural networks designed to extract important local patterns from sequential or grid-structured data. In this study, CNNs are used to capture short-term dependencies from financial time-series input sequences before passing them to recurrent layers for long-term dependency learning Li et al. (2023); Qin (2022).

The fundamental operation in CNN is convolution. A kernel (or filter) slides across the input sequence and applies a linear operation to a fixed-size segment. If x is the input sequence, w the kernel weights, and b the bias term, the 1D convolution operation at position i is computed as follows:

For multi-channel input data, the operation extends across all channels. After convolution, a nonlinear activation function is applied. The Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU) is most commonly used:

To reduce dimensionality and mitigate overfitting, pooling operations are used. For instance, maxpooling over a segment is given by the following:

The resulting feature maps are flattened and passed to a fully connected (dense) layer. The final output is generated using activation functions such as sigmoid or softmax:

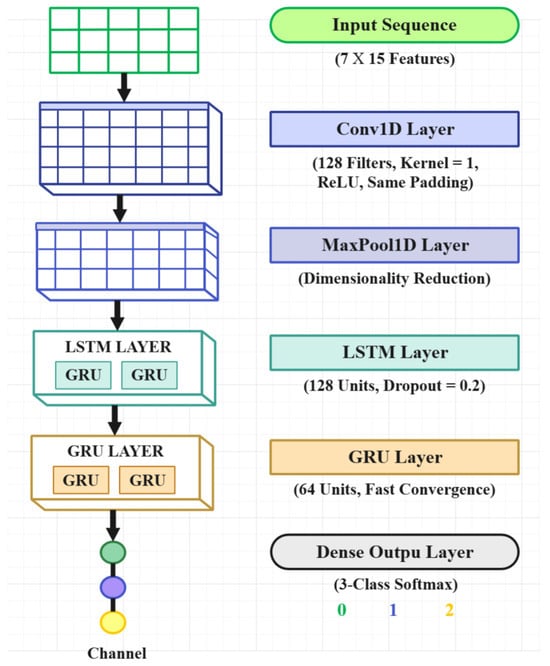

In this study, the CNN is configured with 128 filters, a kernel size of 1, ReLU activation, and ‘same‘ padding. This CNN layer is followed by LSTM and GRU layers to capture hierarchical temporal features, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The hybrid approach of CNN-LSTM and GRU.

3.2. Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM)

LSTM networks are a specialized form of Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) designed to overcome vanishing and exploding gradient problems when learning long-term dependencies. LSTMs incorporate a memory cell and three gating mechanisms—input, forget, and output gates—to control information flow Greff et al. (2016); Hochreiter and Schmidhuber (1997); Staudemeyer and Morris (2019); Yu et al. (2019).

The forget gate determines which information to discard from the previous cell state:

The input gate regulates which new information is stored in the cell:

The updated cell state is computed as follows:

The output gate and hidden state are as follows:

These gates enable the LSTM to dynamically retain or discard information at each time step, allowing for the modeling of long-term sequential patterns.

3.3. Gated Recurrent Units (GRUs)

GRU is a simplified variant of LSTM, introduced by Cho et al. (2014), that merges the forget and input gates into a single update gate, reducing computational load while retaining performance. GRU employs two gates: update and reset.

The update gate controls how much of the previous state to carry forward:

The reset gate adjusts how much of the past to forget:

The candidate hidden state and final hidden state are computed as follows:

GRUs are particularly efficient for modeling medium-term dependencies in time-series data.

3.4. Hybrid CNN–LSTM–GRU Architecture

3.4.1. Input Layer

The hybrid model begins with an input layer consisting of a feature matrix representing quarterly firm-level financial indicators across solvency, profitability, operational capacity, growth potential, and liquidity dimensions. Where T is a sliding time window of past observations. Each row corresponds to a single time step, while each column represents one of the financial indicators, enabling the model to learn both temporal and cross-sectional dependencies.

3.4.2. CNN Layer: Local Feature Extraction

The first stage of the architecture applies a one-dimensional convolutional layer to extract short-term local features from the time-series data. If denotes the feature vector at time t, the convolutional operation with kernel w and bias b is defined as follows:

where K is the kernel size and is the ReLU activation . A MaxPooling operation is subsequently applied as

to retain the most dominant features while reducing dimensionality. This stage allows the network to detect micro-level fluctuations in financial indicators that could signal early warning signs.

3.4.3. LSTM Layer: Long-Term Temporal Dependencies

The output from the CNN is passed to a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) layer to capture long-horizon temporal dependencies. At each time step t, the LSTM maintains a cell state and hidden state using gating mechanisms:

The cell state and hidden state are updated as

where is the output gate and ⊙ denotes elementwise multiplication. This enables the LSTM to selectively retain information relevant to gradual financial risk accumulation over several quarters.

3.4.4. GRU Layer: Efficient Sequential Refinement

To further enhance computational efficiency and capture medium-term temporal dynamics, the LSTM output is fed into a Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) layer. At each time step t, the GRU computes

Here, and represent the update and reset gates, respectively, which control how much past information is carried forward. This design reduces the number of parameters relative to LSTM, enabling faster convergence while preserving accuracy.

3.4.5. Dense Output Layer: Risk Classification

Finally, the output from the GRU layer is passed to a fully connected dense layer with a softmax activation to generate class probabilities over the three financial risk categories, i.e., low, medium, and high:

where denotes the number of classes. The model is trained using categorical cross-entropy loss

to optimize classification performance across all risk levels.

The novelty of this hybrid CNN–LSTM–GRU architecture lies in its hierarchical feature extraction strategy. CNN captures local fluctuations in financial indicators, LSTM models long-horizon dependencies, and GRU provides computationally efficient refinement of temporal dynamics. Unlike prior works relying on single-model architectures, this unified design achieves superior predictive accuracy, balanced class detection, and faster convergence, as demonstrated in our experiments. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, this is among the first studies to apply such a hybrid architecture for quarter-ahead financial risk forecasting in Chinese listed companies, thereby bridging methodological innovation with practical early warning applications.

3.5. Prediction Horizon and Scale

Forecast Setting: Let denote the sequence of T past quarters for firm i (where T is a sliding time window of past observations), and the model learns a mapping such that , i.e., a one-step-ahead () quarterly prediction of the three-class risk label.

Temporal scales: We set the input window to quarters and fix this value for training (2015–2019), validation (2020–2021), and testing (2022–2023) to ensure consistency across all splits. Short-term dynamics are defined as patterns within 1–2 quarters, whereas long-term dynamics capture dependencies spanning up to eight quarters. The CNN emphasizes short local patterns, the LSTM retains long-horizon structure, and the GRU refines short- and mid-range signals efficiently.

Output and decision: The final dense layer yields (softmax) over {Low, Medium, High}. The predicted class is given by . Thresholds may be adjusted to prioritize recall for High-risk firms in supervisory settings. The hybrid architecture is presented in Figure 1.

4. Results and Analysis

4.1. Data Source

All data used in this study were obtained from the CSMAR (China Stock Market and Accounting Research) database. The analysis focuses on A-share listed companies traded on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. The sample selection includes all companies based on financial availability and completeness.

The selection of financial indicators is strongly supported by recent empirical evidence. Studies employing ensemble-based models consistently demonstrate that liquidity, leverage, profitability, and cash flow ratios are among the most influential predictors of corporate bankruptcy and financial distress. Furthermore, advanced feature-selection techniques such as minimum-redundancy maximum-relevancy–Support Vector Machine–recursive feature elimination (MRMR-SVM-RFE) have been widely adopted to enhance predictive performance while reducing dimensionality, ensuring that the most informative variables are retained without introducing noise or redundancy Ding and Yan (2024).

In addition, modern machine learning methods, including artificial neural networks (ANNs), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and generative adversarial networks (GANs), have validated the critical role of these indicators in financial distress prediction D’Ercole and Me (2025); Gajdosikova and Michulek (2025). Professional frameworks and early warning systems also emphasize liquidity and leverage measures as fundamental signals for detecting early stages of financial distress. Together, this evidence justifies the inclusion of these financial indicators in our study as both theoretically sound and empirically robust predictors. Table 2 summarizes the variables and its details.

Table 2.

Variable codes with short names, descriptions, and notes.

4.2. Experimental Pipeline

The experimental process comprises the following stages:

- Data Collection and Preprocessing: Quarterly financial ratio data are cleaned to remove outliers and missing entries. The data are then normalized and reshaped into sequences suitable for CNN and recurrent model inputs.

- Model Training: The models are trained using categorical cross-entropy as the loss function and the Adam optimizer. Hyperparameters are selected via validation-based tuning, and dropout is used where applicable to control overfitting.

- Model Evaluation: Performance is measured using standard classification metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. In addition, confusion matrices and training/validation loss curves are generated to interpret model behavior.

- Prediction and Risk Analysis: The final model is applied to the test set, and predictions are analyzed relative to ground truth to assess its real-world applicability for financial risk detection.

4.3. Experimental Environment

The experiments were conducted using Google Colab with a high-performance GPU (NVIDIA Tesla P100 with 40 GB memory), and 12 GB of RAM. The software environment consisted of Python 3.8.10 as the primary programming language, with TensorFlow 2.8.0 and PyTorch 1.11.0 serving as the main deep learning libraries. For machine learning and data handling, Scikit-learn 1.0.2, Pandas 1.4.2, and NumPy 1.21.5 were employed, while Matplotlib 3.5.1 was used for data visualization. This configuration ensured reproducibility and efficiency for quarterly firm-level financial data modeling, enabling the models to be trained and validated at scale within a practical time frame.

4.4. Data Description and Preprocessing

4.4.1. Descriptive Statistics

We provide comprehensive descriptive statistics for all fifteen financial indicators, including the mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and quartile values. Table 3 presents these details to enable readers to understand the data’s distribution, variability, and scale.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of Financial Indicators.

4.4.2. Data Cleaning Procedures

The dataset underwent rigorous preprocessing as follows:

- Missing Data: Variables with more than 20% missing values were excluded. The remaining missing values were imputed using the median to ensure robustness against skewed distributions.

- Outlier Treatment: Outliers were identified using the Interquartile Range (IQR) method:Winsorization at the 1st and 99th percentiles was applied to minimize their influence while retaining data integrity.

- Final Sample Size: After cleaning, the dataset comprised 4750 companies with 47,837 firm-quarter observations.

4.5. Model Hyperparameter Setting

Table 4 summarizes the key hyperparameters used across all deep learning and baseline models in this study. For the deep learning architectures (CNN, LSTM, GRU, and the hybrid CNN–LSTM–GRU model), the Adam optimizer was employed with a learning rate of 0.001, tuned via the validation set to ensure optimal convergence. A batch size of 64 was adopted to balance computational efficiency with gradient stability, while a dropout rate of 0.3 was applied across layers to prevent overfitting and improve generalization. The hybrid model sequentially integrates CNN for local feature extraction, LSTM for long-term dependencies, and GRU for computationally efficient refinement. For comparison, Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost were included as baseline models using default hyperparameters from standard machine learning libraries, providing a benchmark against non-sequential methods. These settings ensure a fair and transparent evaluation across all models under consistent experimental conditions.

Table 4.

Hyperparameter settings for all models used in the study.

4.6. Data Splitting Strategy

To prevent data leakage and ensure realistic forecasting, we employed a chronological time-based split rather than random sampling. Specifically, data from 2015 to 2019 was used for training, 2020–2021 for validation, and 2022–2023 for final testing. This approach guarantees that no future information leaks into the training set and that the test set represents a true out-of-sample period. Furthermore, all company observations within each time period were kept intact, and the validation set was reserved solely for hyperparameter tuning and model selection, while the test set was held out for unbiased evaluation. Rolling-window cross-validation was additionally performed as a robustness check to confirm the stability of results across multiple future periods.

4.7. Models Performance Evaluation

This section compares the performance of the proposed hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU model with three standalone models—CNN, GRU, and LSTM—to assess its predictive effectiveness in financial risk classification.

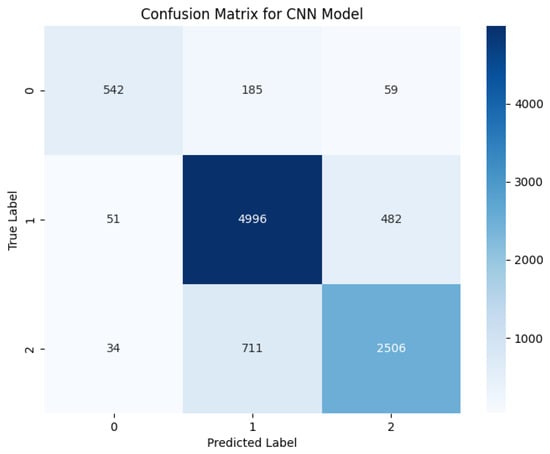

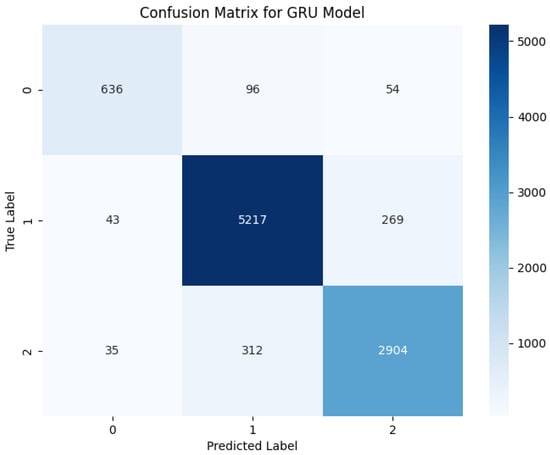

4.7.1. CNN Model Performance

Figure 2 presents the confusion matrix for the CNN model. It performs well on Class 1, with 4996 correct classifications, but shows substantial misclassifications for Classes 0 and 2. Specifically, Class 2 suffers from 711 instances misclassified as Class 1 and 34 as Class 0. For Class 0, 185 samples are labeled as Class 1 and 59 as Class 2.

Figure 2.

Confusion matrix for CNN model.

This highlights CNN’s limitations in capturing the temporal dependencies of firm-level high-frequency financial data, as it is inherently designed for spatial feature extraction. The model struggles with class boundaries where short-term volatility is pronounced.

Figure 3 shows the training and validation history. The CNN model reaches 87% training accuracy, but validation accuracy saturates at 84%. Slight overfitting is observed beyond epoch 20.

Figure 3.

Training history for CNN model.

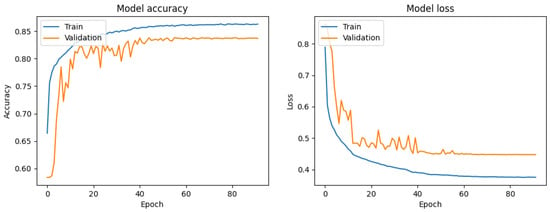

4.7.2. GRU Model Performance

Figure 4 shows the GRU model’s confusion matrix. It demonstrates notable improvements across all classes. Class 1 reaches 5217 correct classifications. Class 2 misclassifications drop to 312 and Class 0 to 96.

Figure 4.

Confusion matrix for GRU model.

As seen in Figure 5, the GRU model exhibits high training and validation accuracy (both above 92%) with minimal divergence and steadily declining loss, indicating excellent generalization.

Figure 5.

Training history for GRU model.

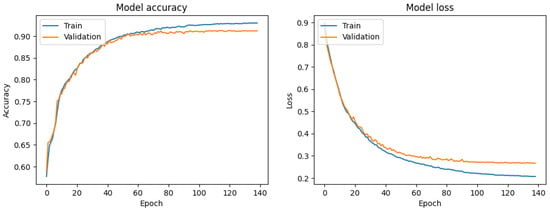

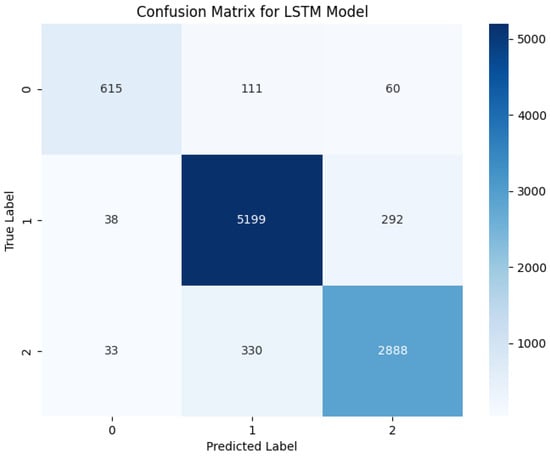

4.7.3. LSTM Model Performance

Figure 6 displays the confusion matrix for LSTM. Class 1 has 5199 correct predictions. Class 0 and Class 2 suffer from 111 and 330 misclassifications, respectively. LSTM handles long-term dependencies but appears to smooth out short-term fluctuations, affecting class separability.

Figure 6.

Confusion matrix for LSTM model.

Figure 7 shows gradual convergence to 92% training and 90% validation accuracy over 160 epochs. The learning curve is smooth but slower, indicating increased training time and potential for overfitting if not controlled.

Figure 7.

Training history for LSTM model.

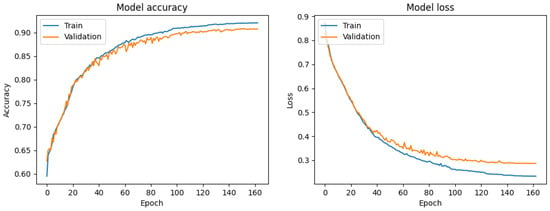

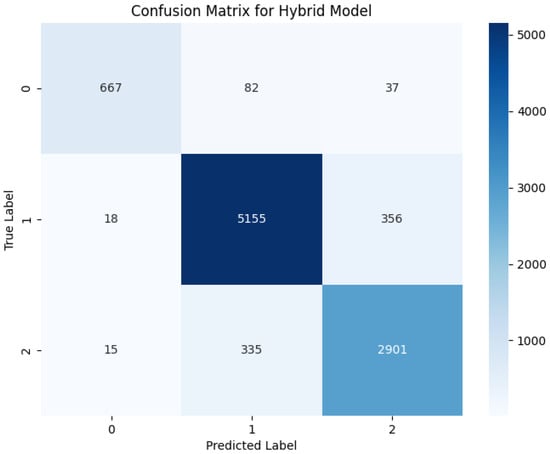

4.7.4. Hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU Model Performance

The hybrid model, shown in Figure 8, achieves the most balanced and accurate classification. Class 1 has 5155 correct predictions; Class 2 misclassifications fall to 335, and Class 0 sees only 82 samples misclassified.

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix for hybrid model.

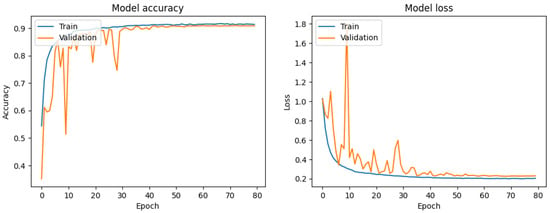

As illustrated in Figure 9, the hybrid model converges rapidly, reaching 92% validation accuracy within 30 epochs. The training and validation curves are tightly aligned, indicating stable learning and minimal overfitting. The hybrid approach effectively combines CNN’s pattern recognition, LSTM’s memory retention, and GRU’s efficiency to handle both local and long-range sequence variations.

Figure 9.

Training history for hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU model.

4.7.5. Comparison of the Models

Table 5 presents the comparative summary of all models across all matrices. The comparative analysis of the four models—CNN, GRU, LSTM, and Hybrid—reveals clear differences in predictive performance across key metrics, namely Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUC, and training time. The CNN model performs the weakest among the four, achieving an accuracy of 0.8409, a precision of 0.8449, a recall of 0.7880, and an F1-score of 0.8126, indicating it struggles with balanced classification, particularly in capturing all relevant positive cases, as reflected in the lower recall value. In contrast, the GRU model demonstrates superior overall performance, achieving the highest accuracy of 0.9154, along with strong precision (0.9060) and recall (0.8820) values, resulting in a balanced F1-Score of 0.8933. This makes it a well-rounded choice for classification tasks that require both sensitivity and specificity. The LSTM model follows closely, attaining an accuracy of 0.9097, precision of 0.9032, recall of 0.8704, and F1-score of 0.8855, reflecting its capability to model sequential dependencies effectively, though slightly underperforming compared to GRU in terms of recall and F1. The Hybrid model, however, surpasses all others in precision (0.9196) and achieves the highest F1-Score (0.9043), coupled with a strong recall of 0.8911 and accuracy of 0.9119, suggesting that its architecture successfully combines the strengths of individual models to deliver both accurate and balanced classification results. In addition, the inclusion of Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost shows that while these models achieved reasonable accuracies of 0.8921 and 0.9032, respectively, along with moderate AUC values of 0.8895 and 0.9022, they still underperformed compared to the deep learning approaches. Notably, the Hybrid CNN–LSTM–GRU model achieved the highest AUC of 0.9253, further confirming its superior ability to balance precision, recall, and F1-Score while maintaining robust discriminatory power across risk classes. Overall, while GRU leads in accuracy, the Hybrid model offers the best trade-off between precision, recall, and F1-Score, indicating robust and consistent predictive capability across classes. The computational time for training the hybrid model is relatively longer, but it provides an overall better performance across precision, recall, and F1-Score.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of all models across multiple metrics.

Table 6 reports the class-wise Precision and Recall for Low-, Medium-, and High-risk categories, along with the Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) and cross-validation accuracy for all models. The results show that the Hybrid CNN–LSTM–GRU model consistently achieves the highest performance across all classes, with Precision values of 0.90, 0.92, and 0.89 and Recall values of 0.91, 0.93, and 0.88 for Low-, Medium-, and High-risk classes, respectively. Its MCC score of 0.91 and cross-validation accuracy of 0.92 further confirm the model’s robustness and balanced classification ability. In contrast, traditional machine learning models such as RF and XGBoost perform reasonably well but fall short of the deep learning approaches, particularly in the High-risk class where accurate detection is critical for early warning systems.

Table 6.

Class-wise metrics, MCC, and cross-validation accuracy for all models.

4.7.6. Summary of Findings

The experimental results confirm that the following:

- CNN performs reasonably well in the majority class detection but struggles with temporal learning and minority classes.

- GRU offers strong performance and efficiency, particularly in short- to mid-term sequence modeling.

- LSTM models long-term dependencies reliably, but with higher computational cost and slower convergence.

- The hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU architecture delivers the best balance of accuracy, speed, and class separation, showing clear practical value for financial early warning.

These findings validate the hybrid model as a robust candidate for real-time financial risk detection, especially in volatile market conditions such as those in China’s evolving financial ecosystem.

5. Discussion

This comparative analysis of deep learning models—including CNN, GRU, LSTM, and the hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU—offers important insights into their effectiveness in forecasting quarterly firm-level financial data, providing higher-frequency information than annual datasets.

While CNN demonstrated moderate accuracy in identifying the dominant class, it failed to model sequential dependencies adequately. The model’s architecture is optimized for spatial feature extraction and is therefore insufficient for capturing temporal volatility in financial risk behavior. The confusion matrix and validation curves both reveal limited generalization, early learning saturation, and signs of mild overfitting.

The GRU model outperformed CNN with a more balanced classification across all classes. Its gating mechanisms enabled it to capture short- and medium-term dependencies efficiently, while also converging rapidly with stable learning dynamics. This makes GRU particularly suitable for time-sensitive applications in financial risk prediction.

The LSTM model also showed strong performance, especially in modeling long-term dependencies. However, it required longer training times and exhibited slightly higher misclassifications rates in the minority classes. Although its learning curve remained stable, the computational cost and complexity of LSTM reduce its practicality in real-time deployment without regularization.

The hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU model outperformed all other models in terms of accuracy, convergence speed, and balanced classification. It successfully integrated CNN’s ability to extract local patterns, LSTM’s strength in modeling long-term memory, and GRU’s efficiency in learning short-term dynamics. This combination allowed the model to detect fine-grained fluctuations in financial risk levels, making it a compelling candidate for use in early warning systems.

In practical terms, the hybrid model offers both high predictive accuracy and operational stability, enabling regulatory agencies, banks, and financial institutions to detect emerging risks earlier and more reliably. Its robustness under quarterly data conditions, providing higher-frequency information than annual data, indicates strong applicability to real-world financial monitoring systems in volatile environments such as China’s digital financial sector.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

This study introduces and empirically evaluates a novel hybrid deep learning model—CNN-LSTM-GRU—for early financial risk warning in the quarterly and dynamic environment of China’s financial markets, providing higher-frequency data relative to annual datasets. The model leverages the strengths of each architecture: CNN for spatial feature extraction, LSTM for long-term trend learning, and GRU for efficient short-term pattern recognition. The hybrid model demonstrates superior classification accuracy, convergence behavior, and generalization compared to the standalone CNN, LSTM, and GRU models.

Empirical findings, based on quarterly firm-level financial ratios, validate the hybrid model’s robustness and practical suitability for real-time financial monitoring. The CNN model, while strong in feature extraction, lacked memory and temporal learning capacity. The LSTM model was effective at modeling long-term sequences but required more training time and risked overfitting. The GRU model offered efficiency and stability but showed limitations in deep long-sequence learning. In contrast, the hybrid model combined their advantages into a reliable, fast-converging architecture suited for volatile financial environments.

This study contributes to the growing literature on hybrid deep learning in finance by demonstrating how different neural network architectures can be effectively integrated to model complex financial sequences, highlighting the importance of using higher-frequency financial data for timely and accurate early warnings, and providing a replicable methodological pipeline for financial risk prediction using structured firm-level indicators.

6.1. Policy Implications

The proposed hybrid model offers actionable tools for policymakers and financial regulators aiming to strengthen systemic resilience in a rapidly digitizing financial landscape. Its capability to detect micro-level changes in firm-level risk with minimal delay enables proactive supervisory interventions, facilitates integration into real-time risk-monitoring dashboards used by institutions such as the People’s Bank of China and the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission (CBIRC), and supports early detection of credit default risk, thereby enhancing credit evaluation processes and portfolio risk assessments.

While our hybrid CNN–LSTM–GRU model demonstrates strong predictive performance, future work will focus on enhancing its interpretability using frameworks such as SHAP and LIME to improve transparency for policymakers. Furthermore, the model aligns with broader financial innovation initiatives, including China’s Fintech Development Plan and global recommendations from the Financial Stability Board. Embedding such hybrid models into operational risk-monitoring tools can improve early responses, capital allocation, and regulatory planning.

6.2. Recommendations for Future Implementation

For full deployment, policymakers should consider building data access frameworks that support AI model training on real-time, high-frequency financial information, while simultaneously defining standards for explainability and promoting ethical AI governance in finance. They should also encourage partnerships between academic institutions, fintech firms, and regulatory bodies to ensure transparency, accountability, and adaptability of predictive models. Furthermore, fostering open financial data ecosystems will be essential to support the development of tailored early warning system (EWS) tools that align with national regulatory goals and enhance systemic resilience. As part of ongoing research, we plan to develop a fully functional prototype integrated with real-time dashboards and conduct case studies with regulatory partners to validate the model’s practical applicability in supervisory environments.

In sum, this hybrid CNN-LSTM-GRU architecture presents a high-performing, generalizable solution for financial risk early warning, with strong academic and practical value. It illustrates how deep learning models can be customized and operationalized to handle high-frequency financial data and offer new tools for informed decision-making in complex and evolving financial systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.L. and M.A.; methodology, M.A.C.; software, M.A.; validation, S.B., M.A. and T.L.; formal analysis, M.A.C.; investigation, S.B.; resources, M.A.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.C.; writing—review and editing, S.B., M.A.C., T.L.; visualization, M.A.C.; supervision, T.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the China Postdoctoral Workstation of Guangzhou Nansha Information Technology Park Co., Ltd., for Registration No. 364571 in the field of Applied Economics and Financial Technology.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of these data. Data were obtained from China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) and are available at https://data.csmar.com/ with the permission of China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR).

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Muhammad Ali Chohan and Teng Li were employed by Guangdong CAS Cogniser, Information Technology Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial of financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Agyapong, Joseph. 2024. Dynamic connectedness among commodity markets, sentiments and global shocks. SSRN Electronic Journal. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4721744 (accessed on 10 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- Alessi, Lucia, and Carsten Detken. 2018. Identifying excessive credit growth and leverage. Journal of Financial Stability 35: 215–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altman, Edward I. 1968. Financial ratios, discriminant analysis and the prediction of corporate bankruptcy. The Journal of Finance 23: 589–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, Fernando, Hiroshi Kimura, and Edward Altman. 2017. Machine learning models and bankruptcy prediction. Expert Systems with Applications 83: 405–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaver, William H. 1966. Financial ratios as predictors of failure. Journal of Accounting Research 4: 71–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, Johannes, Sven List, and Gregor von Schweinitz. 2019. Does machine learning help us predict banking crises? Journal of Financial Stability 45: 100693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, Shamaila. 2025. Dual neural paradigm: Gru-lstm hybrid for precision exchange rate predictions. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications 16: 1029–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Xia, and Zhen Long. 2023. E-commerce enterprises financial risk prediction based on fa-pso-lstm neural network deep learning model. Sustainability 15: 5882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Kyunghyun, Bart van Merriënboer, Caglar Gulcehre, Dzmitry Bahdanau, Fethi Bougares, Holger Schwenk, and Yoshua Bengio. 2014. Learning phrase representations using rnn encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation. arXiv arXiv:1406.1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, Muhammad Ali, Teng Li, Suresh Ramakrishnan, and Muhammad Sheraz. 2025. Artificial intelligence in financial risk early warning systems: A bibliometric and thematic analysis of emerging trends and insights. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science & Applications 16: 1336–51. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ercole, A., and Gianluigi Me. 2025. A novel approach to company bankruptcy prediction using convolutional neural networks and generative adversarial networks. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 7: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Yi, and Chun Yan. 2024. Corporate financial distress prediction: Based on multi-source data and feature selection. arXiv arXiv:2404.12610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drehmann, Mathias, Claudio Borio, and Kostas Tsatsaronis. 2014. Can we identify the financial cycle? In The Role of Central Banks in Financial Stability: How Has It Changed? Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 131–56. [Google Scholar]

- Financial Stability Board. 2022. Promoting Global Financial Stability: Annual Report. Available online: https://www.fsb.org/2022/11/promoting-global-financial-stability-2022-fsb-annual-report/ (accessed on 30 June 2025).

- Gajdosikova, Dominika, and Jakub Michulek. 2025. Artificial intelligence models for bankruptcy prediction in agriculture: Comparing the performance of artificial neural networks and decision trees. Agriculture 15: 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greff, Klaus, Rupesh Kumar Srivastava, Jan Koutník, Bas R. Steunebrink, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 2016. Lstm: A search space odyssey. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 28: 2222–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, Sepp, and Jürgen Schmidhuber. 1997. Long short-term memory. Neural Computation 9: 1735–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosaka, Tetsuo. 2019. Bankruptcy prediction using imaged financial ratios and convolutional neural networks. Expert Systems with Applications 117: 287–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminsky, Graciela, Saul Lizondo, and Carmen M. Reinhart. 1998. Leading indicators of currency crises. IMF Staff Papers 45: 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laeven, Luc, and Fabian Valencia. 2020. Systemic Banking Crises Database: A Timely Update in COVID-19 times. CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14569. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3594190 (accessed on 29 June 2025).

- Li, Jing, Chen Xu, Bai Feng, and Hao Zhao. 2023. Credit risk prediction model for listed companies based on cnn-lstm and attention mechanism. Electronics 12: 1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metawa, Nour, and Samir Metawa. 2021. Internet financial risk early warning based on big data analysis. American Journal of Business and Operations Research 3: 48–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlson, James A. 1980. Financial ratios and the probabilistic prediction of bankruptcy. Journal of Accounting Research 18: 109–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Zhiyong, Xingtong Yang, and Yiyang Lai. 2021. Systemic financial risk early warning of financial market in China using attention-lstm model. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance 56: 101383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Wei. 2022. Research on financial risk forecast model of listed companies based on convolutional neural network. Scientific Programming 2022: 3652931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, Carmen M., and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2009. The aftermath of financial crises. American Economic Review 99: 466–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Xiaoyang, Yue Jing, and Xiaozhu Qin. 2023. Bp neural network-based early warning model for financial risk of internet financial companies. Cogent Economics & Finance 11: 2210362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudemeyer, C. Ralf, and Eric Rothstein Morris. 2019. Understanding LSTM: A tutorial into long short-term memory recurrent neural networks. arXiv arXiv:1909.09586. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, Kim Long, Hoang Anh Le, Thanh Hien Nguyen, and Duc Trung Nguyen. 2022. Explainable machine learning for financial distress prediction: Evidence from Vietnam. Data 7: 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. 2024. Global Economic Prospects, June 2024. Washington: World Bank Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Yong, Xiaosheng Si, Changhua Hu, and Jianxun Zhang. 2019. A review of recurrent neural networks: Lstm cells and network architectures. Neural Computation 31: 1235–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Yinglan, Yi Li, Chen Feng, Chi Gong, and Hongru Tan. 2022. Early warning of systemic financial risk of local government implicit debt based on bp neural network model. Systems 10: 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.