Abstract

Due to a national shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists, pediatric primary care providers (PCPs) are often responsible for the screening, evaluation, and treatment of mental health disorders. COVID-19 pandemic stay-at-home orders decreased access to mental health care and increased behavioral and emotional difficulties in children and adolescents. Despite increased demand upon clinicians, little is known about mental health care delivery in the pediatric primary care setting during the pandemic. This focus group study explored the experiences of pediatric PCPs and clinical staff delivering mental health care during the pandemic. Transcripts from nine focus groups with San Francisco Bay Area primary care practices between April and August 2020 were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. Providers expressed challenges at the patient-, provider-, and system-levels. Many providers reported increased patient mental health symptomatology during the pandemic, which was often intertwined with patients’ social determinants of health. Clinicians discussed the burden of the pandemic their own wellness, and how the rapid shift to telehealth primary care and mental health services seemed to hinder the availability and effectiveness of many resources. The findings from this study can inform the creation of new supports for PCPs and clinical staff providing mental health care.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus (COVID-19) public health crisis and its associated social and economic repercussions have exacerbated problems of access to mental health care for youth [1]. High rates of depression, anxiety, and overall worse mental health have been reported among children and adolescents since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing demand for mental health services [2,3]. However, even before the pandemic, there have been significant mental health access issues in the setting of a severe national shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists and other mental health professionals [4,5]. The communities most critically affected by this workforce shortage are rural, low-income, and racial/ethnic minoritized youth—often served in safety-net settings like federally qualified health centers (FQHC) [6,7]. These communities are at higher risk of mental health challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic [8].

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, one study found that over one-third (34.8%) of youth between the ages of 2–21 received their outpatient mental health care from a primary care provider (PCP) only [9]. Given the increased risk of developing mental health symptoms and decreased access to mental health services during the pandemic (with reductions in school-based mental health) [1], pediatric PCPs and clinical staff (e.g., nurses, social workers, and integrated-care psychologists) have become critical for evaluating and treating youth with mental health concerns. Despite this, many PCPs have long expressed that they often do not feel comfortable treating or managing mental health conditions, or do not feel they have adequate time to address mental health problems in primary care [10,11]. Therefore, there is growing need for psychiatrists and other mental health specialists to support and partner with their primary care colleagues to deliver adequate mental health services during the pandemic and in its aftermath. Promising supports include integrated behavioral health programs, such as child psychiatry access lines, which provide PCPs with real-time telephonic consultation with child psychiatrists [12,13,14].

However, little is known about mental health service delivery in pediatric primary care during the COVID-19 pandemic. This qualitative research study aimed to understand the experiences of pediatric PCPs and clinical staff delivering mental health care during the pandemic through focus group interviews to improve integrated behavioral health programs that support primary care.

2. Methods

This focus group study was designed to understand mental health care delivery experiences among pediatric PCPs and clinical staff. This study was nested within a larger effort to implement the UCSF Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Portal (CAPP) program, modeled after other psychiatric access programs [12,13], which provides free telephonic pediatric psychiatry consultation to PCPs throughout California. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) Checklist was used to guide this study [15].

2.1. Recruitment

We recruited a convenience sample of community clinics and FQHCs in the San Francisco Bay Area that were participating in the initial launch of the UCSF CAPP program April to August 2020. We emailed the clinic manager to solicit clinician participation in a focus group at the time of UCSF CAPP enrollment. Focus groups were recruited until data saturation was achieved.

The main inclusion criterion for participants from these clinics was the provision of pediatric clinical services at the clinic. We included pediatricians, nurse practitioners, an advice nurse, family medicine physicians, social workers, psychologists, and a community health worker. Non-direct patient care staff members, such as administrative staff, were excluded. All participants completed informed consent and received a $50 gift card for their participation. Ethical approval (IRB number 2019-117) was obtained from the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland institutional review board.

2.2. Study Procedures

Focus groups took place online via secure video conferencing services between April and August 2020. Each focus group consisted of clinicians from the same primary care practice. As this study was nested within the UCSF CAPP enrollment process, participants received an orientation to UCSF CAPP and then participated in the focus group. Focus groups lasted ~45 min and were audio recorded on an encrypted device. A child psychiatrist (CML) trained in qualitative research methods moderated the focus groups, and a notetaker (JL, AK, NP) was present. Additionally, we collected de-identified demographic information on all participants (Table 1).

Table 1.

Participant demographics.

The semi-structured focus group interview guide (available upon request) for this study was developed by study researchers (CML, PS) based on prior experience providing child psychiatric consultation to primary care providers and was pilot tested at one pediatric primary care clinic in 2019. The guide was developed to understand the practice’s capacity to treat mental health care among child and adolescent patients, referral systems, and facilitators and barriers to mental health care delivery, and it was initially deployed in April 2020. As this period coincided with the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, additional questions specifically querying provider experiences during the pandemic were added and IRB-approved by June 2020. Of note, the study sample was restricted to those focus groups that discussed the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Data Analysis

Focus group audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and coded independently by two graduate-student researchers (JL, AK) using ATLAS.ti Mac (Version 8.4.4). The researchers utilized a thematic analysis approach, which involved an inductive and iterative process of coding and interpretation to derive themes [16]. A preliminary codebook was created by several members (JL, AK, BL, NP) of the research team. Two researchers (JL, AK) independently applied the codebook to the transcripts, then compared their coded transcripts, and consolidated them into a single ATLAS.ti file. Any differences were resolved through discussion and consensus. Further discussions identified key themes related to the COVID-19 pandemic. We then organized these themes into domains by applying an existing social-ecological framework [17], which posits that individual, relationship, community, and societal factors converge and interact to influence health. We chose this framework because the social-ecological model recognizes that an individual child does not exist in isolation but is nested within family and clinician relationships, community contexts, and social policies. We represented participant quotes by clinic number.

4. Results

Overall, we conducted 11 focus groups. However, we excluded two focus groups from the analysis because these groups did not receive the COVID-19-specific questions and did not discuss experiences pertaining to COVID-19. Therefore, we analyzed comments from a total of nine focus groups. Each focus group consisted of two to ten providers from a pediatric primary care clinic across five San Francisco Bay Area counties: Alameda, Contra Costa, Marin, San Francisco, and San Mateo. Upon recruitment, 50 providers indicated their intent to participate. A total of 48 providers completed the focus group interview. Among those providers, 54% (26/48) worked in FQHCs, and 46% (22/48) worked in community practices (Table 1).

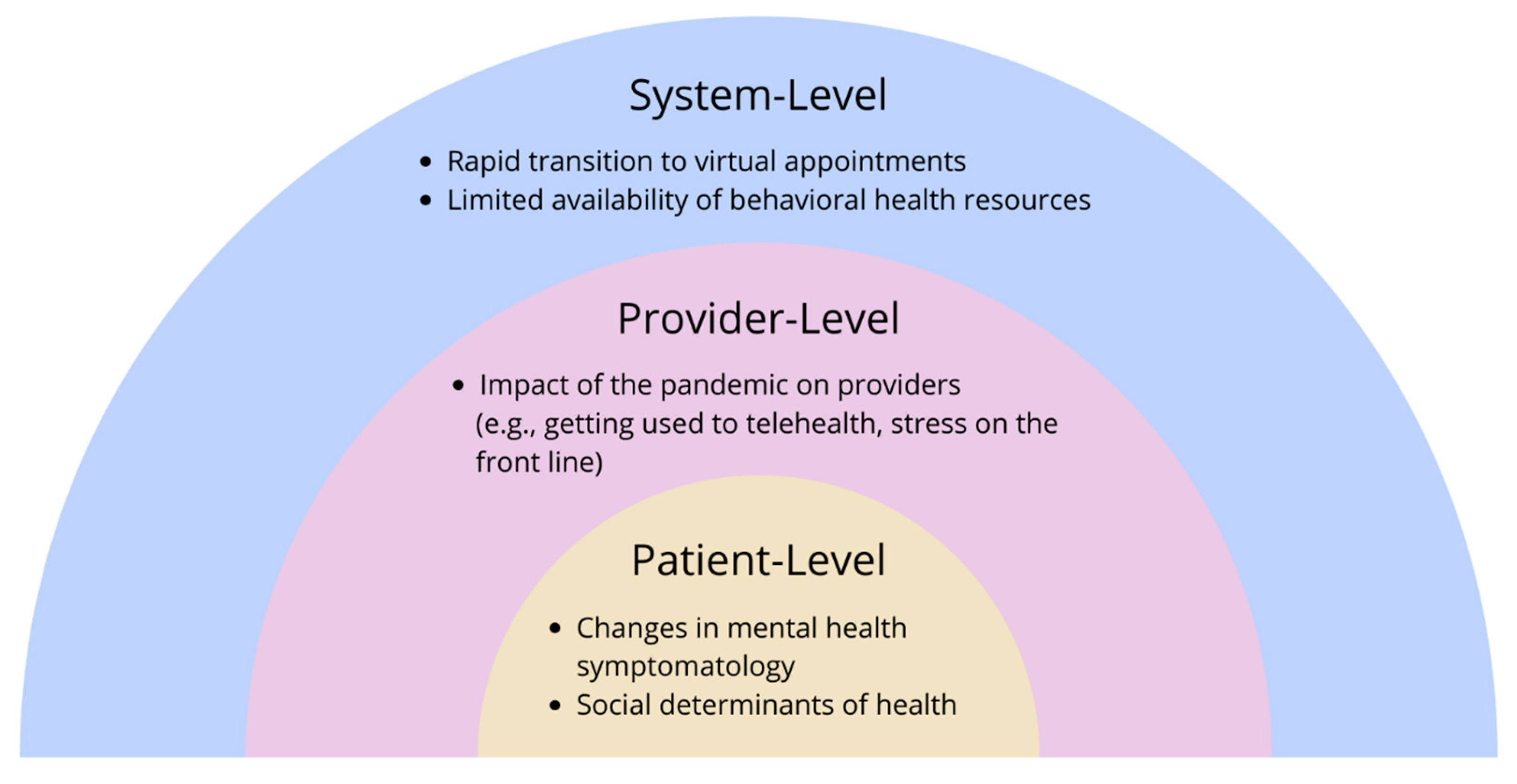

We identified five main themes derived from the data: (1) rapid transition to virtual appointments, (2) limited availability of behavioral health resources, (3) impact of the pandemic on providers, (4) changes in mental health symptomatology, and (5) social determinants of health (See Table 2 for additional quotes). Applying a social-ecological framework, we organized themes into three domains: system-, provider-, and patient-level (Figure 1). In this context, the individual experiences of the patients and providers, as well as their interpersonal interactions, occur within the context of the mental health care system and society. These simultaneous, evolving interactions sum to influence a provider’s experience providing mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

Domains, Themes, and Representative Quotes from Providers on the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health Care Delivery in Pediatric Primary Care.

Figure 1.

Factors influencing pediatric primary care providers’ ability to deliver mental health care during the COVID-19 pandemic as reported by participants, an adapted social-ecological framework.

5. System-Level Domain

5.1. Rapid Transition to Virtual Appointments

As clinics transitioned to virtual appointments during the pandemic, providers across focus groups described virtual appointments as both a facilitator for and barrier to care. Providers noted that virtual appointments were convenient for patients due to reduced cost and travel time, and increased accessibility for people living with physical disabilities. One provider wondered whether the “anonymity” of virtual appointments could reduce fears of stigma associated with seeking behavioral health care (Clinic 8). However, loss of the patient-provider connection was a frequent concern as providers reported challenges engaging with patients, especially young children, and building relationships with new patients via telehealth.

Another consequence of the shift to virtual appointments was screening challenges. Providers reported barriers to screening for mental illness, substance use, and adverse childhood experiences because most screenings were formerly conducted via a self-report questionnaire in the waiting room. For example, a provider reported that the lack of routine wellness appointments during the pandemic provided fewer opportunities to screen patients for mental health concerns and connect them to resources (Clinic 6).

Another concern was confidentiality. Several providers reported concerns about patients’ access to private spaces, particularly for those living in shared family homes, which they believe hindered patients’ ability to be honest and vulnerable during virtual appointments: “It’s two families living in a single bedroom home or the whole family is in a room. So at least when they come into the clinic, we have the opportunity to kick the parent out, ask really private questions” (Clinic 5).

5.2. Limited Availability of Behavioral Health Resources

Clinic sites with integrated behavioral health services or clinic coordinators that help schedule mental health visits reported new challenges with their warm hand-off models during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, warm hand-off models typically involved an in-person introduction to a referral coordinator during the visit. During the pandemic, providers reported that separate phone calls to the patient from the physician and coordinator had disintegrated the collaboration inherent to the warm hand-off model. Ultimately, this contributed to a disconnect between routine health services and mental health services.

Providers’ experiences with mental health referral processes varied. Some providers reported that they had not noticed changes to their mental health referral process, while others reported difficulties because of mental health clinics being closed or overwhelmed during the pandemic. Providers suggested that the capacity of these referrals was also limited by a lack of staffing: office staff were more frequently taking sick leave or time off to care for family members. Among those who commented that they had not noticed a change in the referral process, one provider suggested that it was too soon to notice (August 2020) because prior to the pandemic there was already a lengthy waiting period.

Several providers commented on the effect of the pandemic on school-based resources: “Parents are really stressed… and not getting as much support from the schools” (Clinic 1). Although some school-based resources remained available, many students who previously relied on these resources for learning disabilities or other wellness services lost access during the pandemic due to school closures.

6. Provider-Level Domain

Impact of the Pandemic on Providers

Providers discussed the increased stress that they experienced working in the medical setting during the pandemic. Some spoke explicitly about the fear of dying from COVID-19: “As clinicians, you have your own fear… I don’t want to catch it. I don’t want to die from COVID” (Clinic 3). Providers from community clinics shared the financial stresses of running a healthcare business during a pandemic: “We count ourselves fortunate that we’re still open. I know lot of other practices are not, and so there is that stress. It’s a tough time” (Clinic 3). Some providers also discussed the emotional challenges of being a “de facto trusted reference” for patient families, given the lack of a unified national message in the first few months of the pandemic (Clinic 3).

Providers creatively adapted services to meet patients’ needs during the pandemic, sometimes dramatically changing their workflow and workload. Some examples included shifting clinic services to remote formats, having weekly telehealth check-ins with patients who were unable to see their therapist, and creating internal processes to offer direct counseling to households in which a family member tested positive for COVID-19. Another stated impact on providers was the need for more time to interact with patients during check-ups, video visits, and phone calls to address the impact of COVID-19 on patients’ lives and health.

7. Patient-Level Domain

7.1. Changes in Mental Health Symptomatology

Providers observed increases in mental health symptoms among patients, especially anxiety, depression, and loneliness. For example, a clinician noted, “We’ve done some surveying of community needs after COVID hit and shelter-in-place, [which] revealed a heightened level of anxiety and recurring trauma, depressive feelings, sense of chaos and shortage in the world, and just in general a heightened need” (Clinic 8). Providers attributed some of these symptoms to social isolation and/or increased time at home with family. Providers described a cascade of stress from parents to children during the pandemic, highlighting how community disparities “trickle down” to affect kids (Clinic 7).

Somatic symptoms were also commonly observed, including upticks in stomachaches, worsening diabetes, and worsening hypertension. Providers suspected that in some cases these symptoms could be attributed to underlying behavioral health concerns: “I feel like I’m seeing somatization if that’s the right word. I mean the number of kids in the past two and a half weeks who have had stomach aches or accidents… is probably more than the previous three months put together” (Clinic 3).

Providers recalled parental/guardian concerns encountered during the pandemic, including video gaming addiction, running away from home, or suicidal ideation: “Three-year-olds, four-year-olds, and five-year-olds, are really starting to act out and say kind of troubling things about wanting to die and wanting to kill themselves” (Clinic 4).

Conversely, many providers also reported that school closures during the pandemic had positive effects on mental health for some of their patients. They observed that students affected by social anxiety, bullying, and academic challenges experienced relief from school-based stressors while sheltering-in-place: “A lot of the kids who are suffering from some social anxiety because they were going to school, all of a sudden they felt great” (Clinic 5).

In parallel to the overall increased mental and behavioral health symptoms observed by providers, two practices discussed the increased utilization of behavioral health services among patients. One practice reported a 25% increase in utilization of behavioral health services across three clinic sites, and another noted an increase in therapy needs.

7.2. Social Determinants of Health

Many clinicians discussed the impact of families’ socioeconomic status (SES) on pediatric mental health during the pandemic. A clinician in a community practice primarily serving patients with private insurance observed that their patients’ demographics allowed them to access outdoor yard space at home, which helped them cope with isolation: “I feel like a lot of our families and their kids seem to be coping really well and that might be kind of our demographics. Where—it’s easier. They have houses with yards and some of them are still having help come in” (Clinic 2).

Providers in FQHC practices discussed the economic hardships faced by their patients’ families during the pandemic. Some reported an increase in patients due to families losing employment and corresponding insurance. Additionally, FQHC providers discussed socioeconomic barriers to virtual care, such inability to pay the phone bill or lacking access to technology to access healthcare appointments. They described the necessity of considering a patient family’s SES when determining a course of mental health care. Another provider noted that the civil unrest against racial injustice following the murder of George Floyd in the summer of 2020 compounded the burdens and uncertainty of the pandemic.

8. Discussion

This study revealed experiences of pediatric primary care clinicians delivering mental health care in primary care settings during the first year of the COVID-pandemic. Overall, healthcare services changed fundamentally at the system level, given the rapid shift to virtual appointments for mental health care, which resulted in both facilitators and barriers to care. Providers stated that virtual appointments facilitated medical visits because they reduced the need for patient and family travel to the clinic. However, PCPs also reported patients’ difficulties with accessing technology (devices, Internet, etc.), computer literacy, and obtaining private areas for telehealth visits—all of which they attributed to low SES. Other clinical literature has noted the financial burden of telehealth on families [18], and this speaks to the need to partner with government or community agencies that may provide technology resources. If a PCP is sensing that a patient is lacking privacy at home, then that patient may need to be prioritized for an in-person visit. Providers also acknowledged difficulty in engaging with pediatric patients, particularly young children, via telehealth, which has been cited in the literature as a significant barrier to remote mental health treatment [19,20]. However, clinicians may work on engaging the adult caregiver as an ally in establishing a therapeutic alliance with the child, for example asking the adult to facilitate play with the patient. Nonetheless, as the pandemic progresses, a hybrid care model incorporating options for both virtual and in-person mental health appointments should be considered.

Overall, the pandemic exacerbated pre-existing challenges to the provision of mental health care in primary care. While there was some variation in experience, many providers reported perceiving a reduction in available behavioral health resources. Providers reported long wait times for patient mental health referrals that existed well before the pandemic. The significant challenge in referring patients to specialty mental health care due to the limited mental health workforce could be mitigated by integrated and consultative care models, such as the Collaborative Care Model or Child Psychiatry Access Programs, which help to extend the reach of child mental health specialists [21,22].

Providers themselves also reported experiencing new stressors during the pandemic, including personal fears of COVID-19 infection and increased workloads from adapting services to the pandemic. Clinicians noted that there was the need for more time to interact with patients during telehealth encounters to address the impact of COVID-19 on patients’ lives. Because the focus groups were conducted early in the pandemic, this finding may be attributable to an initial adjustment to the pandemic. However, considering increased and ongoing stress from multiple sources during the pandemic, assessing and supporting healthcare worker well-being is critical.

At the patient level, providers observed increased patient symptomatology and socioeconomic stress. In many cases, our findings in this study aligned with existing literature suggesting that the pandemic has had an overall negative effect on child and adolescent mental health [1,2,23]. While some providers in our study noticed that children with social anxiety, bullying, and academic challenges initially experienced relief during school closures, the literature supports that lockdown conditions prevented exposure to feared situations and reinforced avoidant behaviors, likely making existing mental health conditions worse when schools reopened [24]. Providers described how patients’ pandemic living situations (e.g., overcrowding, lack of private spaces) affected mental health. Providers also discussed elevated stress among families with essential workers due to increased risk for infection or loss of employment. The provision of mental health care requires awareness of patients’ SES and resources both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

9. Limitations

This study represents a subset of providers in one metropolitan area and may not be generalizable to all providers, particularly those practicing in rural settings. Nonetheless, our study included a diverse group of providers across the San Francisco Bay Area. Additionally, the experiences of providers from different delivery settings were included, reflecting a socioeconomically diverse range of patient populations.

The timeline of our study allowed us to observe the impact of the rapidly changing pandemic at different points in time; however, this hindered comparisons between practices. Specifically, FQHC and community practice providers were interviewed at different times during the pandemic. Focus groups with community practices took place between April and August 2020, while focus groups with FQHCs took place in August 2020. Provider quotes were obtained at one point in time and may not represent changing perceptions throughout the pandemic.

10. Conclusions

Our study highlights the longstanding and increasing mental health needs of children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as the increasing complexity of mental health problems that PCPs regularly face in primary care. PCPs have highlighted the increasing challenges to their workloads and their own wellbeing. As the pandemic continues to impact our most vulnerable communities, the findings from this study can inform new collaborations between specialty mental health and primary care to support PCPs and clinical staff delivering mental health care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.L. and C.M.; Methodology, C.M.L. and S.A.; Validation, C.M.L., J.L. and A.K.; Formal Analysis, C.M.L., J.L., A.K., B.L. and N.P.; Investigation, C.M.L., J.L., A.K., B.L. and N.P.; Resources, C.M.L. and P.S.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, C.M.L., J.L., A.K. and B.L.; Writing—Review & Editing, C.M.L., J.L., A.K., B.L., N.P., S.A., P.S. and C.M.; Visualization, C.M.L., J.L. and A.K.; Supervision, C.M.L., P.S. and C.M.; Project Administration, C.M.L. and N.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Lee was supported by funding from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Pilot Research Award for Early Faculty and Child and Adolescent Fellows; and the Hellman Fellows Program. Steinbuchel received grant support from the California Department of Health Care Services, the Health Resources Services Agency, and ACEs Aware. These funding sources had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital Oakland (protocol code 2019-117 and date of approval 25 February 2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Steinbuchel serves as an advisor for Little Otter Health and has received stock options.

References

- Golberstein, E.; Wen, H.; Miller, B.F. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) and Mental Health for Children and Adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 819–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marques de Miranda, D.; da Silva Athanasio, B.; Sena Oliveira, A.C.; Simoes, E.S.A.C. How is COVID-19 pandemic impacting mental health of children and adolescents? Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samji, H.; Wu, J.; Ladak, A.; Vossen, C.; Stewart, E.; Dove, N.; Long, D.; Snell, G. Review: Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and youth—A systematic review. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022, 27, 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AACAP Releases Workforce Maps Illustrating Severe Shortage of Child and Adolescent Psychiatrists. 2018. Available online: https://www.aacap.org/AACAP/Press/Press_Releases/2018/Severe_Shortage_of_Child_and_Adolescent_Psychiatrists_Illustrated_in_AAACP_Workforce_maps.aspx (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- U.S. Public Health Service. Report of the Surgeon General’s Conference on Children’s Mental Health: A National Action Agenda; Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2000.

- McBain, R.K.; Kofner, A.; Stein, B.D.; Cantor, J.H.; Vogt, W.B.; Yu, H. Growth and Distribution of Child Psychiatrists in the United States: 2007–2016. Pediatrics 2019, 144, e20191576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cummings, J.R.; Ji, X.; Druss, B.G. Mental Health Service Use by Medicaid-Enrolled Children and Adolescents in Primary Care Safety-Net Clinics. Psychiatr. Serv. 2020, 71, 328–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protecting Youth Mental Health: The U.S. Surgeon General’s Advisory; Office of the Surgeon General: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Anderson, L.E.; Chen, M.L.; Perrin, J.M.; Van Cleave, J. Outpatient Visits and Medication Prescribing for US Children With Mental Health Conditions. Pediatrics 2015, 136, e1178–e1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Stein, R.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Kerker, B. Beyond ADHD: How Well Are We Doing? Acad. Pediatr. 2016, 16, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Horwitz, S.M.; Kelleher, K.J.; Stein, R.E.; Storfer-Isser, A.; Youngstrom, E.A.; Park, E.R.; Heneghan, A.M.; Jensen, P.S.; O’Connor, K.G.; Hoagwood, K.E. Barriers to the identification and management of psychosocial issues in children and maternal depression. Pediatrics 2007, 119, e208–e218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Straus, J.; Sarvet, B. Behavioral Health Care For Children: The Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project. Health Aff. 2014, 33, 2153–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hilt, R.J.; Romaire, M.A.; McDonell, M.G.; Sears, J.M.; Krupski, A.; Thompson, J.N.; Myers, J.; Trupin, E.W. The Partnership Access Line: Evaluating a child psychiatry consult program in Washington State. JAMA Pediatr. 2013, 167, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Malas, N.; Klein, E.; Tengelitsch, E.; Kramer, A.; Marcus, S.; Quigley, J. Exploring the Telepsychiatry Experience: Primary Care Provider Perception of the Michigan Child Collaborative Care (MC3) Program. Psychosomatics 2019, 60, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Merriam, S.B.; Grenier, R.S. Qualitative Research in Practice: Examples for Discussion and Analysis, 2nd ed.; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Aisbitt, G.M.; Nolte, T.; Fonagy, P. Editorial Perspective: The digital divide—Inequalities in remote therapy for children and adolescents. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlRasheed, R.; Woodard, G.S.; Nguyen, J.; Daniels, A.; Park, N.; Berliner, L.; Dorsey, S. Transitioning to Telehealth for COVID-19 and Beyond: Perspectives of Community Mental Health Clinicians. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 2022, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffnung, G.; Feigenbaum, E.; Schechter, A.; Guttman, D.; Zemon, V.; Schechter, I. Children and Telehealth in Mental Healthcare: What We Have Learned From COVID-19 and 40,000+ Sessions. Psychiatr. Res. Clin. Pract. 2021, 3, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonek, J.; Lee, C.M.; Harrison, A.; Mangurian, C.; Tolou-Shams, M. Key Components of Effective Pediatric Integrated Mental Health Care Models: A Systematic Review. JAMA Pediatr. 2020, 174, 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, A.E.; Platt, R.E.; Bettencourt, A.F.; Serhal, E.; Burkey, M.D.; Sikov, J.; Vidal, C.; Stratton, J.; Polk, S.; Jain, S.; et al. Implementation of Off-Site Integrated Care for Children: A Scoping Review. Harv. Rev. Psychiatr. 2019, 27, 342–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, M.L.; Smali, E.; Richkin, T.; Pincus, H.A.; Chung, H. A novel continuum-based framework for translating behavioral health integration to primary care settings. Transl. Behav. Med. 2020, 10, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samantaray, N.N.; Kar, N.; Mishra, S.R. A follow-up study on treatment effects of cognitive-behavioral therapy on social anxiety disorder: Impact of COVID-19 fear during post-lockdown period. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 310, 114439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).