Abstract

Background: Basic healthcare may significantly decrease neonatal morbidity and mortality. Attention to this, particularly in populations where rates of potentially preventable illness and death within the first weeks of life are extremely high, will have a positive impact on global health. Objective: This manuscript presents the development and impact of a quality improvement programme to reduce the evidence–practice gap in care for neonates admitted to the NICU in a public hospital in India. The programme was locally customised for optimal and sustainable results. Method: The backbone of the project was educational exchange of neonatal nurses and physicians between Norway and India. Areas of potential improvement in the care for the neonates were mainly identified by the clinicians and focus areas were subject to dynamic changes over time. In addition, a service centre for lactation counselling and milk banking was established. Progress over the timeframe 2017–2019 was compared with baseline data. Results: The project has shown that after a collaborative effort, there is a significant reduction in mortality from 11% in the year 2016 to 5.5% in the year 2019. The morbidity was reduced, as illustrated by the decrease in the proportion of neonates with culture-proven sepsis. Nutrition improved with consumption of human milk by the NICU-admitted neonates remarkably increasing from one third to more than three forth of their total intake, and weight gain in a subgroup was shown to increase. With the introduction of family participatory care, hours of skin-to-skin contact for the neonates significantly increased. Additional indicators of improved care were also observed. Conclusions: It is feasible to reduce neonatal mortality and morbidity in a low- and middle-income hospitalised population by improving basic care including nutrition relatively inexpensively when utilising human resources.

1. Introduction

In 2019, 2.4 million children died in the neonatal period defined as the first 28 days of life [1]. The global neonatal mortality rate (NMR) was 17 deaths per 1000 live births that year. Corresponding numbers for India and Norway were 21.7 and 1.4, respectively [1]. Although NMRs have declined significantly since 1990, increased efforts are necessary to achieve the third Sustainable Development Goal “Good health and well-being” [2]. In many neonatal care units in low- and middle-income countries, basic care practice is suboptimal and a main underlying reason for acute and chronic morbidity and mortality. Interventions such as promoting early enteral feeding and intake of mother’s own milk (MOM), maintaining hand hygiene and both providing necessary and minimising irrational use of antibiotics, involvement of parents, and reducing the exposure to stress have been depicted to improve various neonatal outcome parameters [3].

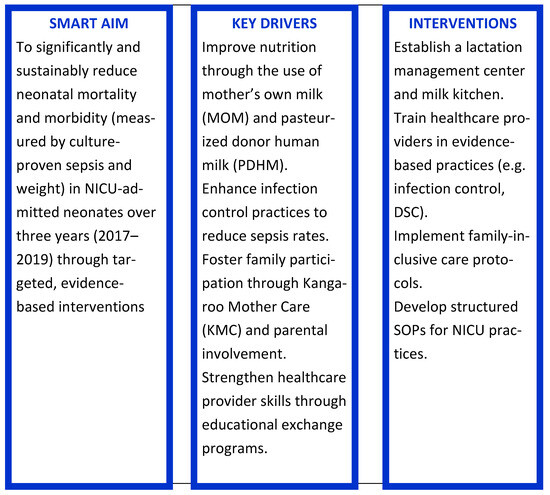

The project entitled “Oslo-Delhi: Improve newborn care” [4] aimed to narrow the gap between theoretical knowledge and active practice of optimised neonatal basic care through collaboration across cultural and social contexts. The two key components were educational exchange of nurses and physicians between neonatal intensive care units (NICU) in New Delhi, India and Oslo, Norway, and establishing a lactation centre with a bank for human milk. The main goal of this Quality Improvement Initiative was to enhance the basic care of sick and premature neonates (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A Quality Improvement Initiative [5]. SMART Specific Measurable Achievable Relevant Time-bound.

2. Methods

Target population and training setting: All neonates admitted to the 80 bedded, level III NICUs at Lady Hardinge Medical College and Kalawati Saran Children’s Hospital (LHMC and KSCH), New Delhi, India during the timeframe of January 2017 to December 2019. The 47 bedded level IV NICU at Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway was the location for exchange. Neonates admitted to this hospital are not reported in this manuscript.

The framework for the project was constructed on a template provided by the Norwegian Agency for Exchange Cooperation, employing educational exchange for learning and development [6]. A total of 12 Indian nurses, 6 Indian physicians, and 9 Norwegian nurses spent 3–18 months at the foreign location in a 3-year relay. In addition, Norwegian resource personnel skilled in human milk banking, administration, education, neonatal care, and infection control participated as per the needs during various timeframes of the project.

Partners’ discussion and previous experience derived from a similar project involving Oslo University Hospital and JK Lone Hospital, Jaipur, India [7], identified the areas of potential improvements. This determined the objectives of the project. Focus areas and cost-effective ways to achieve quality improvements were sought by applying a patient-centred model of care, rather than the more traditional approach merely supporting the provision of services in keeping with established guidelines. “Participant observation” was the most important tool in facilitating collaboration for the continuous development and customisation of this dynamic project.

Empowerment and skills of health providers were enhanced by exposure to a wide range of patient scenarios and different settings to be handled in collaboration with foreign colleagues, and by theory sessions. The framework of the project was reviewed every year.

2.1. Education and Training

Areas of focus included nutrition, hygiene, pain management, kangaroo mother care (KMC), developmental supportive care (DSC), non-invasive mechanical ventilation, resuscitation, temperature control, teamwork, and maintenance of medical equipment (Supplement S1).

Collaborative task- and discussion-based learning were the main approaches. Indian and Norwegian health providers worked together bedside in the two countries’ NICUs, customising activities according to their individual strengths and skills. Patient management as well as different systems and infrastructure at the respective units were observed and discussed.

Teaching sessions and scenario trainings in small groups were frequently arranged, with “topic of the week” (Table 1). Most topics were repeated several weeks. Protocols and standard operational procedures customised to local conditions were constructed (Table 1).

Table 1.

“Topic of the week”, new protocols and Standard Operational Procedure during the three-year project period.

During the tenure of 3 years, survey questions were answered twice by the participants. This provided information on their knowledge of different topics and the activities were modified accordingly (Supplement S2).

With the purpose to empower healthcare providers to continuously take appropriate actions on crucial improvement areas and to facilitate for sustainability, three inter-disciplinary study groups were established, with a primary focus on nutrition, hygiene and housekeeping, and DSC. They met approximately twice a month.

Seminars were conducted twice a year to educate the healthcare providers and equally important to enhance their teaching skills necessary for long term improvements. The last year this was expanded to a two-day seminar with participants and speakers also from outside the project [8].

2.2. Providing Human Milk

A comprehensive lactation management centre (CLMC), ‘Vatsalya Maatri Amrit Kosh’ (literal meaning: ‘a storehouse of mother’s unconditional love and nectar’), was established in the hospital to provide lactation support and to provide pasteurised donor human milk (PDHM) in cases where sufficient MOM is not available. To accomplish this, lactation counsellors and milk bank operators were engaged and trained, and facilities for collection of surplus milk from suitable mothers, processing, storage and dispersion PDHM were established [9] (Table 2).

Table 2.

The “lactation centre curriculum”.

Lactation counselling was offered to groups of women in all antenatal, maternity, neonatal, and some paediatric wards, with complementary individual sessions as and when required. Awareness of the benefits of human milk and (preferably exclusive) breastfeeding, practical assistance and ally of the women’s anxieties were addressed. Mothers of neonates not yet able to suckle directly on the breast due to prematurity or severe illness, were encouraged and helped to express their milk manually or via a breast pump to initiate and sustain production until their neonate managed to suckle. This expressed milk was fed to the infant by gavage or cup.

Women with surplus production were invited to donate to the milk bank. Neonates of GA < 32 weeks or weight < 1500 g were offered (if informed consent from the parents) PDHM as a bridge to support during the first two weeks of life, if MOM was insufficient.

Milk kitchens were set up in the neonatal units to organise thawing and distribution (and in some cases fortification) of PDHM and artificial formula in an aseptic manner.

2.3. Outcome Measures

Mortality rates among neonates admitted to the NICU were documented on monthly basis. Clinical as well as culture-proven sepsis and antibiotic utilisation rates (defined as the proportion of neonates that had received at least one kind of antibiotics to the total number of neonates discharged) were recorded on a daily basis. As quality indicators of neonatal care, nasal injuries due to non-invasive respiratory support and duration of KMC were documented by the nursing personnel in the bedside monitoring sheets. Quality of nutrition was assessed based on daily consumption of MOM, PDHM, and formula, respectively, in the ward, and by the weight change in the first two weeks of life recorded early in the project (2nd month) and repeated 2.5 years later.

Involved personnel reported their own activities and observations of the project’s impact every third month. These reports were utilised for unstructured and qualitative measures such as attitude towards changes, parental involvement, and effect of training (e.g., resuscitation and DSC).

Altered design and practice of physical and work environment such as logistics, teamwork, maintenance of equipment, and more, were noted.

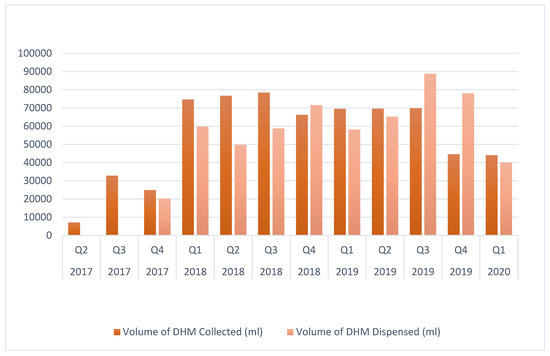

The functionality of the human milk bank was followed through data on the amount of milk donated and that dispensed to the neonatal unit.

Statistical tools: p-values calculated using Pearson’s Chi Square for categorical variables, ANOVA for parametric references.

3. Results

3.1. Mortality, Morbidity and Demographics

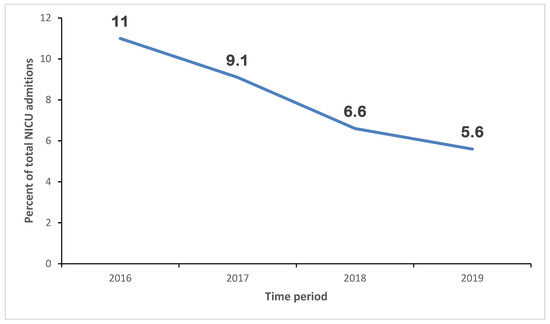

The mortality rate in the NICU was reduced to almost half across the study period from 2016 to 2019 (Figure 2). Notably, despite an increase in the number of neonates admitted to the intensive care unit, a larger proportion being small for gestational age (SGA) and more neonates needing short respiratory support after birth. There is an improvement in the proportion of women receiving appropriate antenatal care and those offered with complete coverage of antenatal steroids. Other demographic characteristics did not differ significantly (Table 3).

Figure 2.

Neonatal mortality rates over 4 years (2016–2019).

Table 3.

Year-wise demographic profile of infants admitted to the neonatal unit (2016–2019).

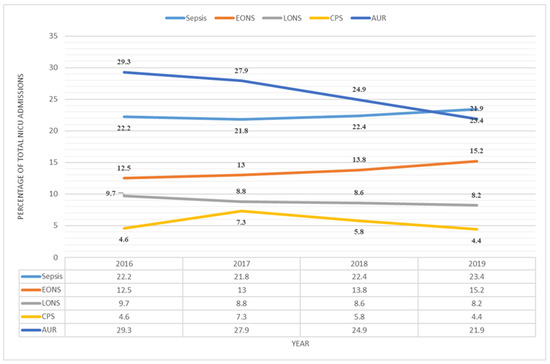

Morbidity, as indicated by the proportion of neonates with culture-proven sepsis, as well as overall antibiotic utilisation rates in NICU, showed a statistically significant decline from 2016 to 2019 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sepsis in NICU-admitted neonates. Sepsis’ includes all cases with clinical, probable, or culture-proven sepsis. Clinical sepsis is defined as presence of signs and/or symptoms attributable to neonatal sepsis with negative sepsis screen and blood culture. Probable sepsis is defined as presence of signs and/or symptoms attributable to neonatal sepsis along with a positive sepsis screen, but blood culture is negative. CPS: Culture proven sepsis is defined as isolation of microorganism from blood culture in a baby with signs and/or symptoms attributable to sepsis with or without a positive sepsis screen. EONS: Early onset sepsis refers to presentation before 72 h of life. LONS: Late onset sepsis refers to presentation after 72 h of life. AUR: Antibiotic utilisation rate defines the proportion of neonates that received at least one antibiotic therapy to the total number of patients discharged.

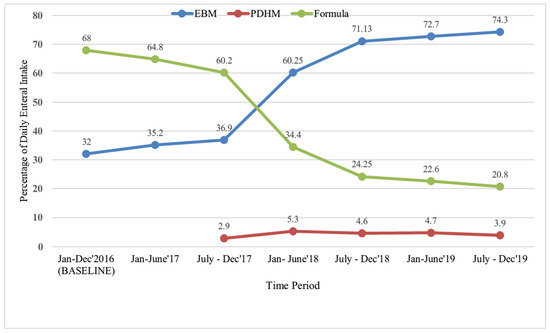

3.2. Nutrition

Daily consumption of MOM by the infants in the NICU increased significantly while the use of baby formula decreased (Figure 4). Sick and small neonates were prioritised to receive available PDHM if their MOM volume was insufficient.

Figure 4.

Enteral nutrition of neonates in the NICU. Percentage of different types of milk consumed in the NICU in different time intervals. EBM, expressed breast milk; PDHM, pasteurised donor human milk.

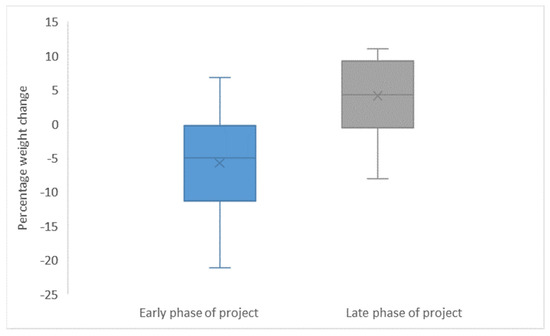

The overall percentage change in weight of GA infants < 32 w from birth to two weeks decreased by mean (SD) 5.7 (7.0) in the initial phase of the project period and increased by mean (SD) 4.1 (5.2) in the late phase (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Weight change in the first 14 d of life in infants GA < 32 w early versus late in the project period. Mean and SD weight change for individual neonates born < 32 w GA investigated in the early phase (2nd month) and in the late phase (2 ½ year later).

3.3. Additional Indicators of Care

DSC and “Structured observation sheets” were implemented for better observation, understanding of the needs and optimal handling of neonates according to their behaviour. As their daily routines, nurses also ensured control of external stimuli, clustering of nursing care activities, non-pharmacological pain management, and strengthening of parent involvement. Parents became active in the care of their hospitalised neonates. Improved understanding, along with a change in attitude towards KMC evolved. Other qualitative observations include improved resuscitation after focusing on standard operational procedures and teamwork in scenario training. Table 4 depicts quantitative data on KMC and nasal injury. Duration of skin-to-skin contact for individuals increased. A greater proportion of neonates, including those extremely premature and those on non-invasive respiratory support, received KMC. More caretakers, mothers, and others, engaged. There was a significant reduction in the proportion of nasal injuries due to non-invasive respiratory support, particularly the most severe (Table 4).

Table 4.

Frequency of nasal injuries and duration of KMC.

3.4. Implemented Routines

Routines for infection control were attended to in several ways. Focus on hand hygiene intensified and accomplished by adding new washing facilities at the entrances and making hand disinfectants more available. Immediate sorting of waste and laundry in appropriate bags in stands replaced heaps on the floor. Construction work was performed to hinder vermin in the wards. Protocols for routines and responsibility for regular cleaning of incubators, milk kitchen equipment, and more were framed and implemented.

According to the qualitative reports, better teamwork was obtained, as illustrated by the more consistent and accurate handover reports, dividing responsibility for the particular patients, and empowerment of colleagues through competence sharing and debriefing.

Efforts to maintain medical equipment were made by designating responsibilities to individual personnel to follow up routines for use, service, and repair (such as ensuring sufficient water in the cPAP-machine, choosing crucial alarms, organising service of ventilators).

3.5. The Comprehensive Lactation Management Centre (CLMC)

The CLMC offers individual assistance and helps all lactating women on a daily basis irrespective of whether their baby was admitted to the NICU or not. The most common challenges that interfere with the early initiation of breastfeeding include primiparous mothers, preterm born neonates admitted to the NICU, and engorgement of breasts.

The main goal was to provide MOM to all infants, using PDHM mainly as a bridge. The turnover in the milk bank was quite stable (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Quarterly depiction of the volume of donor human milk (DHM) collected and disbursed.

Contribution to “National guidelines and SOPs of Indian milk banks” was a ripple effect of developing the lactation centre, as SOPs developed locally to some extent served as references for drafting the national ones [10].

4. Discussion

The goal of the project “Oslo-Delhi: Improve newborn care” was to enhance the basic care of sick and premature neonates by narrowing the gap between the theory of optimal neonatal care and locally customised practise, and by establishing a lactation centre. Basic care is required for the wellbeing of all neonates, necessary for the survival of sick and premature neonates, and fundamental for all advanced medical treatment of neonates. A bundle of awareness, knowledge, skills, practical actions and efforts was implemented. The impact of the project is illustrated with various indicators. Due to the synergistic nature of the interventions, separate evaluation of the variables cannot be defined.

The mortality rate in the NICU decreased despite a larger and more vulnerable population. The proportion of SGA neonates and neonates suffering from early onset neonatal sepsis (EONS) was higher. EONS is mainly caused by factors occurring before admittance to the NICU; hence, it is not controllable [11]. The share of neonates with late onset neonatal sepsis (LONS) and culture-proven sepsis was reduced; however, and lower antibiotic utilisation rates resulted in reduced morbidity. The focus on infection prevention and augmenting the developing immune system (i.e., by providing human milk and limiting exposure to antibiotics), enhances this. Antimicrobial stewardship indicates better care as these drugs may also harm and, therefore, should be subjected to strict indications [12,13,14]. Decreased mortality and morbidity indicate better care, as do less cases of nasal injuries (for which nursing skills are crucial), more KMC, and better weight gain. The documented increase in nutrition with human milk is tantamount to better nutrition in this population [15]. In addition to increased growth, adequate nutrition is necessary for achieving optimal neurodevelopment [16] and greatly enhances the immune system [17,18]. Our results are in accordance with WHO: “child deaths can be prevented by providing immediate breastfeeding, improving access to skilled health professionals for antenatal, birth, and postnatal care, improving access to nutrition and micronutrients, promoting knowledge of dangers”.

Factors contributing to optimal care for neonates are described in the literature. The amount of information appears overwhelming, and it is challenging to prioritise and combine elements that are effective and feasible for a particular location. It may be more time consuming than what can be afforded to determine appropriate improvements. An external collaborating partner may observe the situation from a different angle and base considerations on alternate experiences, thus contributing to different solutions. Together, collaborators obtain a broader perspective of the present situation and a larger base of experience to separate futile and potentially significant measures to develop plans [19]. Returned exchanged personnel add to this as they have been exposed to different solutions, practised unfamiliar routines, and experienced results of these.

The exchange of health providers is beneficial for more reasons. Implementing changes in basic routines, especially those requiring more effort without necessarily immediately having a big impact, calls for patience, trust, and understanding amongst the staff which may require raised health literacy as well as altered attitude. It is recognised that not only knowledge and skills but also an attitude to own labour efforts and self-confidence are crucial [20,21]. Performing one’s professional skills in a different context and milieu often results in new perceptions of one’s own labour, which may influence attitude. Accordingly, personnel engaged in the project reported a positive attitude towards change and higher empowerment as a major change.

In addition to educational exchange, the project comprised development of a lactation centre. Nutrition is a ladder to higher levels of health support. The lactation centre facilitates many steps on this ladder. It serves as a source for developing and sharing knowledge and skills between colleagues and mothers. Furthermore, donated surplus milk serves a dual purpose. The receiving neonates avoid early exposure to formula and the donors keep up their production till their own neonates need more milk. Potential donors would otherwise not express milk, thereby staggering their production in a critical phase as well as increasing the risk of engorged breasts or discarding the milk because they lack access to a private freezer for storage. After MOM, PDHM is the second-best nutrition. Milk kitchens in the neonatal units are extended arms of the milk bank for safe defrosting and distribution of PDHM to the neonates. The development of a National guidelines and SOPs of Indian milk banks illustrates how a system and infrastructure alterations the results from individual efforts and attitudes.

Leading causes of neonatal morbidity and mortality, such as prematurity and infections, are largely preventable. India harbours health centres delivering top world-class perinatal care. The variation between locations causes unnecessary high national NMR. We believe that projects like the one described here, demonstrating improvements achieved by relatively limited economic resources, may be a step in the direction of the grander vision “Good health and wellbeing for all (SDG 3)”. Providing evidence for cost-effective measures may be a way for the global society to incentivize, urge, and support national efforts for extended sustainable overall improvement.

5. Conclusions

Care of hospitalised neonates was enhanced through educational exchange and facilitation for exploiting the potential of human milk. Mortality and morbidity were reduced. Reciprocal partnership, prioritising competence sharing, and comprehensive focus areas may effectively support “Better health for all”.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children12030326/s1, Supplement S1: Expected project; Supplement S2: Survey.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.H. and S.N.; data curation, K.H., G.K. and I.T.; formal analysis, K.H., S.G. and G.K.; investigation, K.H., S.G. and G.K.; methodology, K.H. and S.N.; project administration, K.H. and S.N.; resources, K.H.; validation, K.H.; writing—original draft, K.H.; writing—review and editing, K.H., S.G., G.K., I.A.H., J.J. and S.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The project was funded by NOREC (Organisational ID: NO 981965132) and Oslo University Hospital, Norway.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical aspects of the project were discussed with and approved by all parties, including hospital authorities and Institutional ethics committees (Ref: Project description and agreement 112912E2), NO 981965132 on 25 October 2016. All analysed data are anonymous. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Data Availability Statement

All material is available from the authors on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to technical limitations.

Acknowledgments

We extend our gratitude to the healthcare professionals and administrative teams in Department of Neonatology, LHMC and KSCH, India and Department of Neonatal Intensive Care, Division of Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine, Oslo University Hospital Oslo, Norway for their support and participation in the educational exchange programme. We thank the Department of Global Health, Division of Emergencies and Critical Care, Oslo University Hospital Oslo Norway led by Kristin Schjølberg for administrating the collaboration project and Anne Marie Hagen Grøvslien for invaluable efforts in developing the lactation centre. We are especially grateful to the participants whose dedication was instrumental in bridging the evidence–practice gap in neonatal care. Our heartfelt appreciation also goes to the families of the hospitalised neonates, whose trust and resilience motivated our efforts.

Conflicts of Interest

There were no potential conflicts of interest and no opportunity costs.

References

- Unicef. Neonatal Mortality. Available online: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-survival/neonatal-mortality/ (accessed on 22 February 2021).

- Hug, L.; Alexander, M.; You, D.; Alkema, L. National, regional, and global levels and trends in neonatal mortality between 1990 and 2017, with scenario-based prokections to 2013: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2019, 7, e710–e720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Atawi, K.; Elhalik, M.; Dash, S. Quality improvement initiatives in neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for improved care outcomes—A review of evidence. J. Pediatr. Neonatal Care 2019, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NOREC. Improved Newborn Care Programme 2017–2022. Available online: https://www.norec.no/prosjekter/improved-newborn-care-programme-2017-2020/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Ogrinc, G.; Davies, L.; Goodman, D.; Batalden, P.; Davidoff, F.; Stevens, D. SQUIRE 2.0 (Standards for QUality Improvement Reporting Excellence): Revised publication guidelines from a detailed consensus process. BMJ Qual. Saf. 2016, 25, 986–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NOREC. Collaboration Agreement Application Templates. Available online: https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=c45ee220adb943bbJmltdHM9MTcyNDExMjAwMCZpZ3VpZD0zNTYxM2VkNS1iZDEzLTYwMGUtM2YyOS0yYTM0YmNlNjYxMmImaW5zaWQ9NTM5NA&ptn=3&ver=2&hsh=3&fclid=35613ed5-bd13-600e-3f29-2a34bce6612b&psq=NOREC+template&u=a1aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cubm9yZWMubm8vZW4vbmV3cy9ncmFudC1yZWNpcGllbnRzL3VwZGF0ZWQtY29sbGFib3JhdGlvbi1hZ3JlZW1lbnQtYXBwbGljYXRpb24tdGVtcGxhdGVzLw&ntb=1 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Haaland, K.; Sitaraman, S. Increased breastfeeding; an educational exchange program between India and Norway improving newborn health in a low- and middle-income hospital population. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2022, 41, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nangia, S. Indo Norwegian CME on Advances in Noenatology. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwimzfHIz86IAxW7PRAIHZ9WE6sQFnoECBwQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.nnfi.org%2Fassests%2Fupload%2Fupcoming-pdf%2FScientific_Programme-_Final_20_2_2020_Final_(1).pdf&usg=AOvVaw0CKoKL6wZvezoiG6kDKENe&opi=89978449 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Weaver, G.; Sachdeva, R.C. Treatment Methods of Donor Human Milk: Recommendations for Milk Banks in India. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2016, 69 (Suppl. S2), 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. National Guidelines on Lactation Management Centres in Public Health Facilities. Available online: https://nhm.gov.in/images/pdf/Nutrition/LMU-guidelines/National_Guidelines_Lactation_Management_Centres.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Simonsen, K.A.; Anderson-Berry, A.L.; Delair, S.F.; Davies, H.D. Early-onset neonatal sepsis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 21–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajar, P.; Saugstad, O.D.; Berild, D.; Dutta, A.; Greisen, G.; Lausten-Thomsen, U.; Mande, S.S.; Nangia, S.; Petersen, F.C.; Dahle, U.R.; et al. Antibiotic Stewardship in Premature Infants: A Systematic Review. Neonatology 2020, 117, 673–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shekhar, S.; Petersen, F.C. The Dark Side of Antibiotics: Adverse Effects on the Infant Immune Defense Against Infection. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 544460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzan-Yulzari, A.; Turta, O.; Belogolovski, A.; Ziv, O.; Kunz, C.; Perschbacher, S.; Neuman, H.; Pasolli, E.; Oz, A.; Ben-Amram, H.; et al. Neonatal antibiotic exposure impairs child growth during the first six years of life by perturbing intestinal microbial colonization. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidelines on Optimal Feeding of Low Birth-Weight Infants in Low- and Middle-Income Countries; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Fenton, T.R.; Merlino Barr, S.; Elmrayed, S.; Alshaikh, B. Expected and Desirable Preterm and Small Infant Growth Patterns. Adv. Nutr. 2024, 15, 100220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celik, E.; Cemali, O.; Sahin, T.O.; Deveci, G.; Bicer, N.C.; Hirfanoglu, I.M.; Agagunduz, D.; Budan, F. Human Breast Milk Exosomes: Affecting Factors, Their Possible Health Outcomes, and Future Directions in Dietetics. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Natal, A.C.C.; de Paula Menezes, R.; de Brito Roder, D.V.D. Role of maternal milk in providing a healthy intestinal microbiome for the preterm neonate. Pediatr. Res. 2024, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ward, C.L.; Shaw, D.; Anane-Sarpong, E.; Sankoh, O.; Tanner, M.; Elger, B. Defining Health Research for Development: The perspective of stakeholders from an international health research partnership in Ghana and Tanzania. Dev. World Bioeth 2018, 18, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Liu, M.; Wang, X.; Hsu, M. Interventions to support the psychological empowerment of nurses: A scoping review. Front. Public Health 2024, 12, 1427234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Niu, Y.; Xin, Y.; Hou, X. Emergency department nurses’ intrinsic motivation: A bridge between empowering leadership and thriving at work. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2024, 77, 101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).