Abstract

Objective: To evaluate the clinical and biochemical differences between pediatric patients with suspected foreign body aspiration (FBA) who had foreign bodies detected on bronchoscopy and those who did not. Methods: Patients undergoing bronchoscopy for suspected FBA were retrospectively divided into two groups: Group 1 (n = 59), with confirmed foreign body; Group 2 (n = 50), without foreign body. Age, blood gas parameters (pCO2, pO2, SpO2), and type and localization of foreign bodies were recorded and statistically compared. Results: The mean age was significantly lower in Group 1 (24.63 ± 12.32 months) than in Group 2 (37.12 ± 32.98 months; p = 0.014). Group 1 had significantly higher pCO2 levels (41.24 ± 13.37 mmHg vs. 31.53 ± 6.44 mmHg; p < 0.001) and lower pO2 levels (45.78 ± 12.18 mmHg vs. 53.98 ± 13.24 mmHg; p = 0.001). Oxygen saturation values showed no significant difference between groups (p = 0.19). Among confirmed cases, foreign bodies were located in the right bronchial system (56%), left bronchial system (41%), and trachea (3.4%). Conclusions: Children diagnosed with FBA were younger and exhibited greater abnormalities in blood gas parameters compared to those without FBA. While bronchoscopy remains essential for the definitive diagnosis and treatment of suspected FBA, our findings suggest that these results may play a significant role in reducing unnecessary bronchoscopies.

1. Introduction

Foreign body aspiration (FBA) is defined as the entry of a foreign material into the tracheobronchial system during respiration. FBA is particularly common in the pediatric population between 1 and 3 years of age and represents a potentially life-threatening condition. While it may present acutely with clinical manifestations such as cough, dyspnea, stridor, and asphyxia, chronic cases may be complicated by recurrent pneumonia or air trapping [1]. Approximately two-thirds of deaths related to FBA occur immediately at home following the event; however, in patients who reach the hospital, mortality rates are reported between 0 and 1.5% [2]. Multiple studies have emphasized that aspirated foreign bodies are most commonly lodged in the right main bronchus, with organic materials such as peanuts and almonds being predominant, and that urgent bronchoscopic removal is usually required [3].

Traditional diagnostic tools for FBA include physical examination, radiological imaging, and bronchoscopy, while the use of capnography and arterial/venous blood gas measurements has been very rarely detailed in the literature. Capnography, which is the monitoring of CO2 concentration in expired breath, and capnometry, which is the measurement of CO2 concentration, are non-invasive methods increasingly used to assess ventilation in critically ill patients. In particular, systematic investigations focusing on partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2) values are extremely limited. Case reports have suggested that hypercapnia may develop in patients with ventilation insufficiency, reflecting airway obstruction as part of the pathophysiology of FBA [4,5]. Especially in “ball-valve” type obstructions, distal air trapping and impaired gas exchange are likely to occur [6]. Thus, quantitative data derived from pCO2 measurements could potentially contribute to the diagnostic process of FBA. However, a systematic analysis statistically correlating pCO2 levels with the diagnosis and ventilatory impact of FBA is still lacking.

Preoperative oxygen saturation (SpO2) and the partial pressure of oxygen (pO2) values, although not sufficiently evaluated in the literature, have been considered potentially useful in determining the severity of suspected FBA and the necessity for bronchoscopy in anecdotal and small-scale studies. In a retrospective study, Zhang et al. reported that operative duration, foreign body size, and presence of pneumonia during bronchoscopy increased the risk of hypoxemia, thereby highlighting the importance of preoperative oxygenation parameters [7].

The aim of the present study was to analyze the role of preoperatively recorded pCO2, pO2, and SpO2 values in detecting the presence of tracheobronchial foreign bodies in patients presenting with suspected FBA. By doing so, we aimed to reduce unnecessary use of bronchoscopy, particularly in high-risk patients with comorbidities and increased morbidity and mortality.

2. Methods

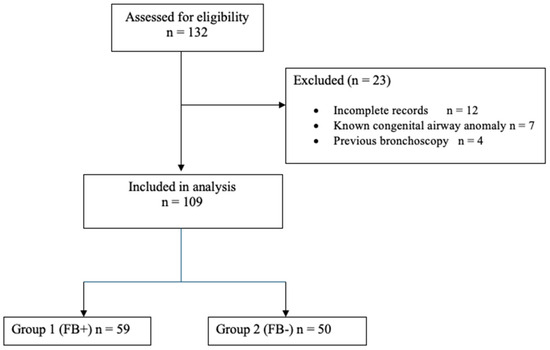

Between October 2021 and June 2025, patients presenting with suspected FBA were evaluated by thoracic surgeons. A total of 109 patients who continued to be clinically suspected of FBA after history, physical examination, and radiological imaging, and subsequently underwent bronchoscopy, were included in the study. Patients with incomplete records, known congenital airway malformations without suspected foreign body, or prior bronchoscopy during the study period were excluded. The patient selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection.

All patients with suspected FBA underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy (FOB) under general anesthesia in the operating room following insertion of a laryngeal mask airway (LMA). Patients in whom a tracheobronchial foreign body was observed during FOB were classified as Group 1 (n = 59), while those without a foreign body were classified as Group 2 (n = 50). For patients with confirmed FBA, rigid bronchoscopy was performed during the same session to remove the foreign body. Data including age, sex, presence and laterality of foreign body, and preoperative pO2, pCO2, and SpO2 values were recorded. All blood gas values are reported in mmHg, with kPa equivalents provided in parentheses where appropriate (1 mmHg ≈ 0.133 kPa). Additionally, the type of foreign body (organic vs. inorganic) was recorded for Group 1 (confirmed FBA) cases.

Preoperative respiratory and metabolic status was assessed using three complementary modalities:

- Venous blood gas analysis (Radiometer ABL90 FLEX analyzer, Radiometer Medical ApS, Copenhagen, Denmark) was performed immediately after peripheral intravenous cannulation in the operating room. A 1 mL sample was drawn from the antecubital vein, and pO2 (venous) values were recorded in mmHg (with kPa equivalents provided in results).

- Capnography was performed using a Dräger Infinity Delta monitor with mainstream sidestream sensor (Dräger Medical GmbH, Lübeck, Germany). End-tidal CO2 (ETCO2) was continuously measured during spontaneous breathing and reported as pCO2 (capnography-derived).

- Pulse oximetry (same Dräger monitor) provided continuous peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) values, recorded as the average over a stable 3 min period before any sedation or oxygen administration. All measurements were taken after a 5 min stabilization period with the child in a semi-upright position and before induction of anesthesia. The children were breathing spontaneously on room air and were not yet intubated or sedated during the measurement period

Preoperative data were prospectively compared with postoperative results.

Radiological findings (Unilateral hyperinflation, atelectasis and/or pneumonia, and normal chest radiograph) were recorded and compared between children with and without confirmed foreign body aspiration.

Statistical Analysis

The distribution of continuous variables was assessed for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Variables with normal distribution were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and compared between groups using the independent samples t-test. Non-normally distributed variables were reported as median (interquartile range) and compared with the Mann–Whitney U test (none in the present study). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate.

95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for all major between-group differences. To account for age as a potential confounder, a multivariate binary logistic regression model was constructed with confirmed foreign body aspiration as the dependent variable and age, pCO2, pO2, and SpO2 as independent variables. Results were reported as adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% CI.

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.5.1 (R Core Team, Vienna, Austria, 2024). A two-sided p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 109 patients were included in the study. Of these, 59 patients (54.1%) in whom a foreign body was detected during bronchoscopy were classified as Group 1, while 50 patients (45.9%) without a detected foreign body were classified as Group 2. The gender distribution was similar between the two groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic, venous blood gas, and non-invasive parameters between groups.

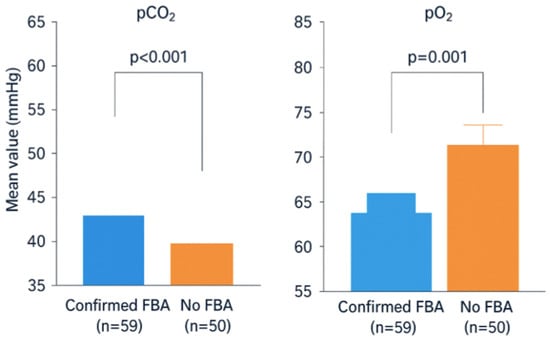

The mean age was 24.63 ± 12.32 months in Group 1 and 37.12 ± 32.98 months in Group 2, with a statistically significant difference between groups (p = 0.014). pCO2 was significantly higher in Group 1 (41.24 ± 13.37 mmHg) compared to Group 2 (31.53 ± 6.44 mmHg; p < 0.001). pO2 was lower in Group 1 (45.78 ± 12.18 mmHg) than in Group 2 (53.98 ± 13.24 mmHg; p = 0.001) (Figure 2). SpO2 was 73.44 ± 17.85 in Group 1 and 77.63 ± 15.64 in Group 2, though this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.19).

Figure 2.

Mean preoperative pCO2 (Capnography-derived) and pO2 (Venous Blood Gas) levels in children with confirmed foreign body aspiration (FBA) compared with those without FBA. The FBA group showed significantly higher pCO2 and lower pO2 values, indicating impaired gas exchange due to airway obstruction. Error bars represent the Standard Deviation (SD). pCO2: Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide (ETCO2 value obtained by Capnography device). pO2: Partial Pressure of Oxygen (Obtained via Venous Blood Gas (VBG) analysis).

Multivariate logistic regression adjusting for age confirmed that elevated pCO2 (adjusted OR 1.15, 95% CI 1.09–1.22, p < 0.001) and reduced pO2 (adjusted OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.89–0.97, p = 0.001) were independent predictors of confirmed foreign body aspiration, whereas SpO2 was not (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis for predictors of confirmed foreign body aspiration (adjusted for age).

Among patients with confirmed foreign body aspiration, 33 foreign bodies (56%) were localized in the right bronchial system, 24 (41%) in the left bronchial system, and 2 (3.4%) in the trachea (Table 3). Among the 59 patients in Group 1, 56 foreign bodies (94.9%) were organic (e.g., nuts, seeds), while 3 foreign bodies (5.1%) were inorganic (e.g., plastic fragments, pins). No intraoperative or postoperative morbidity or mortality was observed in any patient.

Table 3.

Distribution of foreign body localization (Group 1).

Distribution of foreign body localization among confirmed cases (Group 1): The right bronchial system was the most frequent site of foreign body impaction (56%), followed by the left bronchial system (41%) and trachea (3.4%).

Additionally, radiological findings differed significantly between the groups (Table 4). Normal chest X-ray was observed in 92% of patients without foreign body, whereas only 45.8% of those with confirmed foreign body had normal imaging (p < 0.001). Unilateral hyperinflation was the most common abnormal finding in Group 1 (30.5%).

Table 4.

Radiological findings in patients with and without confirmed foreign body aspiration.

4. Discussion

FBA is a life-threatening condition that requires urgent airway intervention, particularly in children. A detailed history and physical examination remain crucial in suspected cases. The most common clinical findings include cough, choking sensation, wheezing, and unilateral reduction in breath sounds, which should be supported with radiological assessment. However, normal imaging does not exclude the diagnosis of FBA.

In this prospective study, patients in Group 1 had a significantly lower mean age (24.63 ± 12.32 months) compared to Group 2 (37.12 ± 32.98 months; p = 0.014). This finding is consistent with previous pediatric FBA studies that report a high-risk profile in children under the age of three [8,9,10]. Large multicenter studies have shown that 50–80% of cases occur in the 1–3-year age group, while aspiration is less frequent but associated with higher morbidity and mortality in infants under one year of age [11]. In flexible bronchoscopy series, the median age is reported around 24 months, reflecting that most cases involve toddlers who have just begun walking and chewing [12]. Developmental factors, such as immature neuromotor coordination, lack of posterior teeth, oral exploratory behavior, and concurrent activities during feeding, increase the risk of FBA in younger children; therefore, both literature data and our findings suggest that the diagnostic threshold for suspicion should be lower in children under three years of age [13].

Capnography, or continuous end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring, is a non-invasive method that provides real-time assessment of CO2 levels in the body. CO2, produced during cellular metabolism, is transported to the lungs via circulation and exhaled. Continuous end-tidal CO2 monitoring provides valuable information about ventilation, metabolism, and circulation. It is commonly used in emergency departments, operating rooms, intensive care units, and during patient transport, particularly to confirm endotracheal tube placement [14]. During cardiopulmonary resuscitation, changes in cardiac output are reflected in end-tidal CO2 concentrations, and during sedation, capnography has been shown to detect respiratory failure earlier than pulse oximetry or respiratory rate alone. In our study, pCO2 levels were significantly higher in Group 1 (41.24 ± 13.37 mmHg), while pO2 levels were significantly lower (45.78 ± 12.18 mmHg). These findings demonstrate that FBA causes mechanical airway obstruction, restricting alveolar ventilation and resulting in alveolar hypoventilation with subsequent CO2 retention (hypercapnia), and impaired ventilation-perfusion balance, leading to hypoxemia [8,9,15,16]. Respiratory acidosis may become particularly severe in cases of delayed diagnosis or bilateral obstruction [17].

In partial obstructions, a “ball-valve” mechanism may occur due to airflow imbalance, leading to air trapping and further impairment of CO2 elimination [15]. The degree of hypercapnia correlates with the level and severity of obstruction, being more pronounced in proximal tracheobronchial occlusions [11]. In children, narrower airway anatomy predisposes to earlier ventilation-perfusion mismatch, resulting in a rapid rise in arterial CO2 pressure [18]. Recent clinical studies have also demonstrated that elevated pre-bronchoscopy pCO2 is an important predictor of foreign body presence [12,19].

Airway obstruction disrupts alveolar ventilation, leading to hypoxemia, which is most commonly manifested by reduced SpO2 levels [7]. However, in our study, no significant difference in oxygen saturation was observed between Group 1 (73.44 ± 17.85) and Group 2 (77.63 ± 15.64) (p = 0.19). The mean preoperative SpO2 values (73–78%) may appear unusually low for clinically stable children; however, this cohort consisted of highly symptomatic patients evaluated urgently. The measurements were obtained in the operating room environment on room air, before any sedation or oxygen supplementation. Many toddlers were anxious or crying intermittently, a well-recognized trigger for transient desaturation in partial airway obstruction [20].

Several possible explanations for the lack of significant difference between the groups are supported by the literature. First, in partial obstructions, airway patency may be partially preserved, allowing baseline SpO2 values to remain within normal limits, especially at rest [21]. Moreover, children possess strong compensatory mechanisms, and SpO2 may remain stable until hypoxemia develops, thereby masking early desaturation [10,15,22]. Indeed, some studies have demonstrated that the location and size of the foreign body are more predictive of clinical manifestations, while SpO2 tends to decline significantly only in cases of complete obstruction or severe ventilation–perfusion mismatch [20,21,22]. Finally, other studies have reported that low SpO2 levels are more commonly associated with delayed diagnoses or complicated cases, while no significant differences are seen in patients who present early [19].

Therefore, the lack of a significant association between SpO2 and FBA in our study appears consistent with the pathophysiological and clinical factors described in the literature.

Regarding localization, foreign bodies were detected in the right bronchial system in 56% of cases, the left bronchial system in 41%, and the trachea in 3.4%. This distribution aligns with previous studies, as the anatomical structure of the right main bronchus predisposes to higher rates of foreign body lodgment [15,16,18]. Although less frequent, tracheal foreign bodies may result in more severe respiratory compromise [23].

Regarding the characteristics of the aspirated materials, the overwhelming majority of foreign bodies found in Group 1 were organic (94.9%), aligning with previous large pediatric series which commonly cite nuts and seeds as the predominant aspirated materials. This high prevalence of organic material is crucial for interpreting our gas exchange findings. Organic foreign bodies often cause more severe airway mucosal inflammation, swelling, and greater bronchial obstruction due to their hygroscopic nature, potentially leading to a more pronounced ventilation-perfusion mismatch and, consequently, the significantly higher pCO2 and lower pO2 levels observed in our FBA cohort. While other variables such as size and chronicity were not analyzed, the strong predominance of organic materials in our study supports the finding of severe physiological compromise, which was the focus of our investigation.

Bronchoscopy remains the gold standard for both the diagnosis and treatment of FBA [23]. However, to avoid unnecessary procedures, integration of radiological findings, clinical history, and gas exchange parameters is recommended in selected cases [24]. Furthermore, developing algorithmic approaches based on gas exchange parameters and clinical profiles prior to bronchoscopy may play an important role in minimizing invasive interventions [10].

In cases where no foreign body was detected (Group 2), symptoms and findings were likely attributable to other respiratory pathologies such as viral infections, asthma, or bronchitis. Combining clinical and radiological findings increases diagnostic accuracy [8,9,10,15], which may partly explain why bronchoscopy was performed in some of these patients. The presence of these underlying inflammatory or obstructive conditions, which can also affect gas exchange, is implicitly acknowledged as a limitation of our study. While Group 2 exhibited significantly lower pCO2 and higher pO2 levels compared to Group 1, reflecting generally better gas exchange, it is plausible that the observed mean values for Group 2 are slightly altered by these mimics. Nevertheless, the clear distinction in gas exchange parameters supports the utility of blood gas analysis in distinguishing the more profound physiological impact of FBA from that of common pediatric respiratory mimics

This study has certain limitations. Being single-center reduces the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, while we included the type of foreign body, variables such as size and duration of aspiration and onset of symptoms were not included in the analysis. Future multicenter studies with larger cohorts should consider these parameters to provide a more comprehensive evaluation [9,16,18].

Table 5 presents the main differential diagnoses that should be considered when similar blood gas abnormalities (elevated pCO2 and/or reduced pO2) are observed in children with suspected foreign body aspiration. A witnessed choking episode and unilateral radiological findings remain the most reliable discriminators for FBA.

Table 5.

Differential diagnosis of abnormal blood gas parameters (↑ pCO2 and/or ↓ pO2) in children with suspected foreign body aspiration.

5. Conclusions

In our study, patients with bronchoscopy-confirmed foreign body aspiration were found to be younger in age, with elevated pCO2 and reduced pO2 levels. Based on these results and the current literature, we suggest that in patients aged 1–3 years presenting with suspected foreign body aspiration, pCO2 values above the normal range (35–45 mmHg) and pO2 values below normal may strongly support the likelihood of a tracheobronchial foreign body. However, given the high variability in pCO2 (SD ±13.37 mmHg) and potential clinical overlap, these parameters should be interpreted cautiously and strictly within the context of the overall clinical picture.

Although the difference in SpO2 did not reach clinical significance, our findings indicate that gas exchange parameters may serve as useful adjuncts in the diagnostic process. Furthermore, the predominance of the right bronchial system as the most common site of foreign body lodgment was reaffirmed. Clinical decision-makers should consider age, blood gas parameters, and the likelihood of localization collectively prior to bronchoscopy, in order to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures and enhance patient safety.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and T.A.; Methodology, M.K. and R.Y.; Software, M.K.; Validation, M.K., T.A. and R.Y.; Formal Analysis, M.K. and R.Y.; Investigation, M.K. and T.A.; Resources, M.K. and T.A.; Data Curation, M.K. and T.A.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.K., T.A. and R.Y.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.K., T.A. and R.Y.; Visualization, M.K.; Supervision, T.A.; Project Administration, M.K., T.A. and R.Y.; Funding Acquisition: M.K. and T.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Scientific research projects of Necmettin Erbakan University, grant number 211718008/2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Necmettin Erbakan University Faculty of Medicine (approved on 6 June 2020, protocol code 2020/2561).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants who were involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The research data can be requested from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available, as the authors want to carry out further analyses and publish them before the data can be made available to the public.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of the personnel in the operating room at the Necmettin Erbakan University Faculty of Meram, Konya, Türkiye.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Bajaj, D.; Sachdeva, A.; Deepak, D. Foreign body aspiration. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 5159–5175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarısoy, Ö.; Liman, Ş.T.; Aydoğan, M.; Topçu, S.; Burç, K.; Hatun, Ş. Çocukluk çağı yabancı cisim aspirasyonları:klinik ve radyolojik değerlendirme. Çocuk Sağlığı Ve Hast. Derg. 2007, 50, 96–101. [Google Scholar]

- Torsello, M.; Sicuranza, L.; Meucci, D.; Salvati, A.; Tropiano, M.L.; Santarsiero, S.; Calabrese, C.; D’oNghia, A.; Trozzi, M. Foreign body aspiration in children: Our pediatric tertiary care experience. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2024, 40, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvenshagen, L.N.; Grindheim, G.; Stene-Johansen, J.K.; Franer, E.; Kahrs, C.R.; Svennerholm, K.; Myhre, M.K.T. Foreign body aspiration in a child. Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 2025, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Ramos, J.J.; Marín-Medina, A.; Castillo-Cobian, A.A.; Felipe-Diego, O.G. Successful Management Foreign Body Aspiration Associated with Severe Respiratory Distress and Subcutaneous Emphysema: Case Report and Literature Review. Medicina 2022, 58, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkle, F.; Olives, T.D.; Merkle, S.; Rieves, A. Unusual foreign body aspiration in a 4-year-old patient. J. Am. Coll. Emerg. Physicians Open 2024, 5, e13284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.J.; Lin, M.Y.; Zhou, M.; Dan, Y.Z.; Gu, H.B.; Lu, G.L. Hypoxaemia risk in pediatric flexible bronchoscopy for foreign body removal: A retrospective study. BMC Pediatr. 2024, 24, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, Z.M.; Subha, S.T. A Five-Year Review on Pediatric Foreign Body Aspiration. Int. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 25, e193–e199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Ding, F.; An, Y.; Li, Y.; Pan, Z.; Wang, G.; Dai, J.; Li, H.; Wu, C. Occult foreign body aspirations in pediatric patients: 20-years of experience. BMC Pulm. Med. 2020, 20, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdem, A.O.; Etensel, B.; Yazıcı, M.; Karaca Özkısacık, S. Diagnostic Evaluation of Foreign Body Aspiration in Children. J. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 8, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Su, S.; Chen, C.; Yao, H.; Xiao, L. Tracheobronchial Foreign Bodies in Children: Experience From 1,328 Patients in China. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 873182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautin, A.; Marakhouski, K.; Pataleta, A.; Sanfirau, K. Flexible bronchoscopy for foreign body aspiration in children: A single-centre experience. World J. Clin. Pediatr. 2024, 13, 91275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Shubha, A.M. Unusual Airway Foreign Bodies in Children: Demographics and Management. J. Indian. Assoc. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 29, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhende, M.S.; Thompson, A.E.; Orr, R.A. Utility of end-tidal CO2 detector during stabilisation and transport of critically ill children. Pediatrics 1992, 89, 1042–1044. [Google Scholar]

- Shostak, E. Foreign body removal in children and adults: Review of available techniques and emerging technologies. AME Med. J. 2018, 3, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, A.; Murthy, V. Foreign body aspiration: A review of current strategies for management. Shanghai Chest 2021, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Zarie, H.; Yousef Alani, H.; Bukhari, A.A.; Ibrahim Shokry, H.; Rabeh Alshamani, M. Multidisciplinary Management of Foreign Body Aspiration in Pediatrics: A Case Complicated by Bilateral Pneumothorax and Respiratory Failure. Cureus 2025, 17, e78287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mîndru, D.E.; Păduraru, G.; Rusu, C.D.; Țarcă, E.; Azoicăi, A.N.; Roșu, S.T.; Curpăn, A.; Jitaru, I.M.C.; Pădureț, I.A.; Luca, A.C. Foreign Body Aspiration in Children-Retrospective Study and Management Novelties. Medicina 2023, 59, 1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Mitra, R.; Mondal, S.; Kumar, S.; Sengupta, A. Foreign Body Aspiration in Children and Emergency Rigid Bronchoscopy: A Retrospective Observational Study. Indian J. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2023, 75, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, S.S.; Bajpai, M.; Singh, A.; Baidya, D.K.; Jana, M. Foreign body in the bronchus in children: 22 years experience in a tertiary care paediatric centre. Afr. J. Paediatr. Surg. 2014, 11, 252–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.K.; Brown, K.; McGill, T.; Kenna, M.A.; Lund, D.P.; Healy, G.B. Airway foreign bodies (FB): A 10-year review. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2000, 56, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shlizerman, L.; Mazzawi, S.; Rakover, Y.; Ashkenazi, D. Foreign body aspiration in children: The effects of delayed diagnosis. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2010, 31, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fidkowski, C.W.; Zheng, H.; Firth, P.G. The anesthetic considerations of tracheobronchial foreign bodies in children: A literature review of 12,979 cases. Anesth. Analg. 2010, 111, 1016–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salih, A.M.; Alfaki, M.; Alam-Elhuda, D.M. Airway foreign bodies: A critical review for a common pediatric emergency. World J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 7, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).