Acid–Base Status and Cerebral Oxygenation in Neonates: A Systematic Qualitative Review of the Literature

Highlights

- Studies with the lowest risk of bias mostly showed no significant correlations between cerebral oxygenation and acid base status.

- Further well-designed studies with minimal risk of bias are necessary to clarify this issue.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

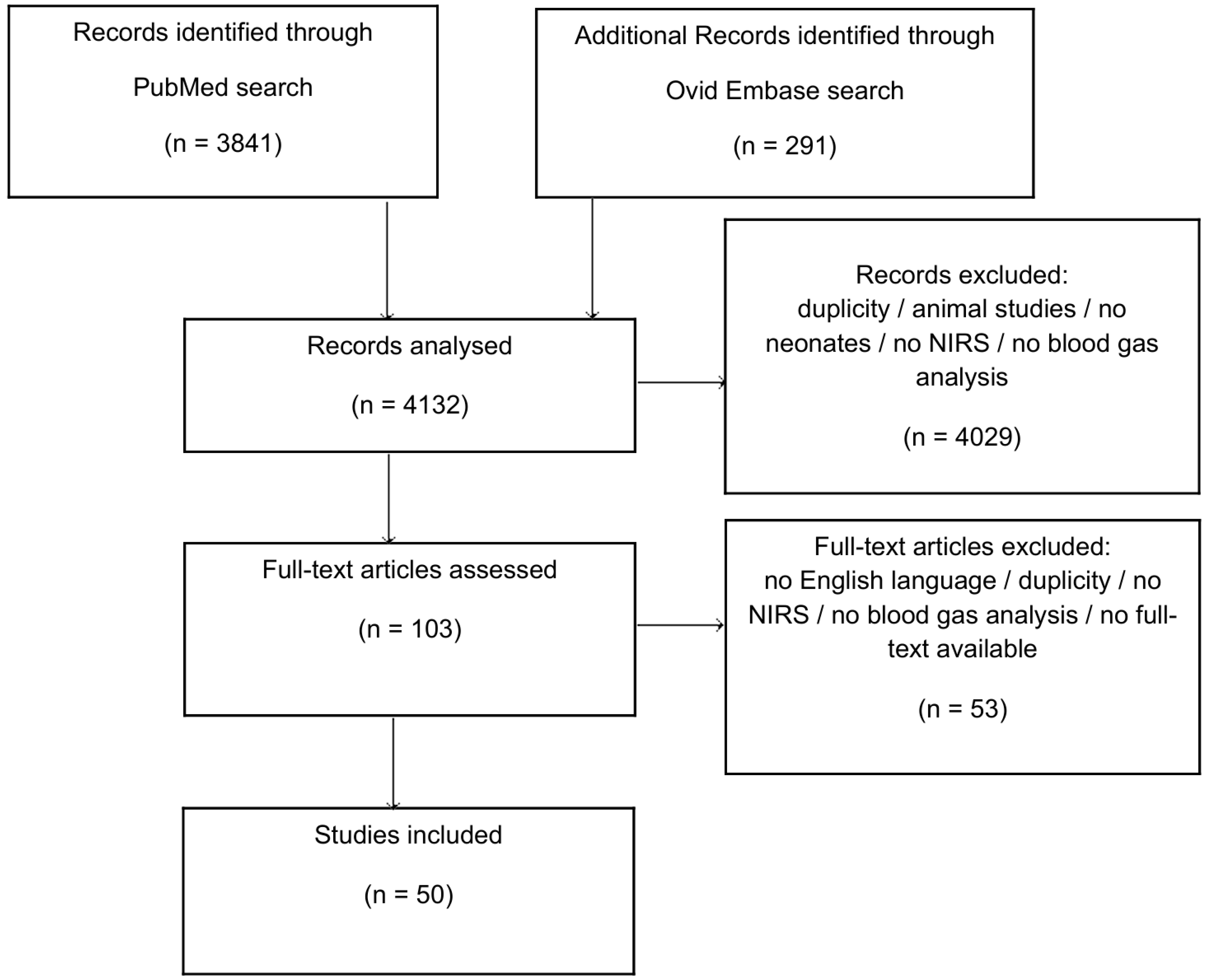

2.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

2.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria—Population

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria—Measurements (Exposure)

2.6. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria—Types of Publication

2.7. Study Selection

2.8. Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

3. Results

3.1. pH Value and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

3.2. Base Excess (BE) or Base Deficit (BD) and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

3.3. Bicarbonate (HCO3) and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

3.4. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias Assessment

4. Discussion

4.1. pH Value and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

4.2. Base Excess (BE) or Base Deficit (BD) and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

4.3. Bicarbonate (HCO3) and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

4.4. Studies Involving Neonates with Cardiovascular System Impairments

4.5. Studies During the Transition from Intra- to Extrauterine Life

4.6. Studies on Term and Preterm Neonates

4.7. Proposed Explanatory Model

4.7.1. pH and Cerebral Oxygenation

4.7.2. Base Excess (BE) or Base Deficit (BD) and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

4.7.3. Bicarbonate (HCO3) and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation

4.8. Risk-of-Bias Assessment of Studies Describing Correlations Between Parameters of Acid–Base Status and Cerebral Oxygenation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ad. | Administration |

| BD | Base deficit |

| BE | Base excess |

| CDH | Congenital diaphragmatic hernia |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| crSO2 | Cerebral regional oxygen saturation |

| EA | Esophageal atresia |

| FTOE | Fractional tissue oxygen extraction |

| HCO3 | Bicarbonate |

| HIE | Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy |

| IVH | Intraventricular hemorrhage |

| LVO | Left ventricular output |

| min | Minutes |

| NIRS | Near-infrared spectroscopy |

| n.r | Not reported |

| PA | Perinatal asphyxia; |

| PH-IVH | Pulmonary and intraventricular hemorrhage |

| PVL | Periventricular leukomalacia |

| RBC | Red blood cell |

| RVO | Right ventricular output |

| U.A. | Umbilical artery |

| U.V. | Umbilical venous |

References

- Handley, S.C.; Passarella, M.; Lee, H.C.; Lorch, S.A. Incidence Trends and Risk Factor Variation in Severe Intraventricular Hemorrhage across a Population Based Cohort Sara. J. Pediatr. 2018, 200, 24–29.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, Y.-C.; Ainslie, P.N. Blood pressure regulation IX: Cerebral autoregulation under blood pressure challenges. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2014, 114, 545–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badurdeen, S.; Roberts, C.; Blank, D.; Miller, S.; Stojanovska, V.; Davis, P.; Hooper, S.; Polglase, G. Haemodynamic instability and brain injury in neonates exposed to Hypoxia–Ischaemia. Brain Sci. 2019, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.V.; Klinger, A.; Yazdi, S.; Rahman, A.K.M.F.; Wright, S.; Barganier, A.; Ambalavanan, N.; Carlo, W.A.; Ramani, M. Prevention of severe brain injury in very preterm neonates: A quality improvement initiative. J. Perinatol. 2022, 42, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greisen, G. Autoregulation of cerebral blood flow in newborn babies. Early Hum. Dev. 2005, 81, 423–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yiş, U.; Kurul, S.H.; Kumral, A.; Cilaker, S.; Tuğyan, K.; Genç, Ş.; Yılmaz, O. Hyperoxic exposure leads to cell death in the developing brain. Brain Dev. 2008, 30, 556–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plomgaard, A.M.; Alderliesten, T.; Austin, T.; van Bel, F.; Benders, M.; Claris, O.; Dempsey, E.; Fumagalli, M.; Gluud, C.; Hagmann, C.; et al. Early biomarkers of brain injury and cerebral hypo- and hyperoxia in the SafeBoosC II trial. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0173440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, P.G.; Tan, A.; O’Donnell, C.P.; Schulze, A. Resuscitation of newborn infants with 100% oxygen or air: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2000, 364, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leijser, L.M.; de Vries, L.S. Preterm brain injury: Germinal matrix–intraventricular hemorrhage and post-hemorrhagic ventricular dilatation. In Handbook of Clinical Neurology; Elsevier B.V.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 162, pp. 173–199. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji, A.; Shah, V.; Shah, P.S. Periventricular/Intraventricular Hemorrhage and Neurodevelopmental Outcomes: A Meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2015, 136, 1132–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergani, P.; Locatelli, A.; Doria, V.; Assi, F.; Paterlini, G.; Pezzullo, J.C.; Ghidini, A. Intraventricular hemorrhage and periventricular leukomalacia in preterm infants. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004, 104, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, C.P.F.; Kamlin, C.O.F.; Davis, P.G.; Morley, C.J. Feasibility of and delay in obtaining pulse oximetry during neonatal resuscitation. J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 698–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finer, N.; Leone, T. Oxygen saturation monitoring for the preterm infant: The evidence basis for current practice. Pediatr. Res. 2009, 65, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, J.A.; Morley, C.J. Monitoring oxygen saturation and heart rate in the early neonatal period. Semin. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010, 15, 203–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baik, N.; Urlesberger, B.; Schwaberger, B.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Avian, A.; Pichler, G. Cerebral haemorrhage in preterm neonates: Does cerebral regional oxygen saturation during the immediate transition matter? Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015, 100, F422–F427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyttel-Sorensen, S.; Greisen, G.; Als-Nielsen, B.; Gluud, C. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring for prevention of brain injury in very preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD011506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suppan, E.; Pichler, G.; Binder-Heschl, C.; Schwaberger, B.; Urlesberger, B. Three Physiological Components That Influence Regional Cerebral Tissue Oxygen Saturation. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 913223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, S.; Thewissen, L.; Austin, T.; da Costa, C.S.; de Boode, W.P.; Dempsey, E.; Kooi, E.; Pellicer, A.; Rhee, C.J.; Riera, J.; et al. Near-infrared spectroscopy monitoring of neonatal cerebrovascular reactivity: Where are we now? Pediatr. Res. 2023, 96, 884–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, F.; Tarumi, T.; Liu, H.; Zhang, R.; Chalak, L. Wavelet coherence analysis of dynamic cerebral autoregulation in neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. NeuroImage Clin. 2016, 11, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichler, G.; Urlesberger, B.; Baik, N.; Schwaberger, B.; Binder-Heschl, C.; Avian, A.; Pansy, J.; Cheung, P.-Y.; Schmölzer, G.M. Cerebral Oxygen Saturation to Guide Oxygen Delivery in Preterm Neonates for the Immediate Transition after Birth: A 2-Center Randomized Controlled Pilot Feasibility Trial. J. Pediatr. 2016, 170, 73–78.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, S.; Wyllie, J. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010. Section 7. Resuscitation of babies at birth. Resuscitation 2010, 81, 1389–1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer, A.; Greisen, G.; Benders, M.; Claris, O.; Dempsey, E.; Fumagalli, M.; Gluud, C.; Hagmann, C.; Hellström-Westas, L.; Hyttel-Sorensen, S.; et al. The SafeBoosC phase II randomised clinical trial: A treatment guideline for targeted near-infrared-derived cerebral tissue oxygenation versus standard treatment in extremely preterm infants. Neonatology 2013, 104, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankins, G.D.V.; Speer, M. Defining the Pathogenesis and Pathophysiology of Neonatal Encephalopathy and Cerebral Palsy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 102, 628–636. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.L.; Yu, H.M.; Lin, J.; Chen, S.Q.; Liang, Z.Q.; Zhang, Z.Y. Mild hypothermia via selective head cooling as neuroprotective therapy in term neonates with perinatal asphyxia: An experience from a single neonatal intensive care unit. J. Perinatol. 2006, 26, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.S.; Melo, Â.; Fachada, A.H.; Solheiro, H.; Nogueira Martins, N. Umbilical Cord Blood Gas Analysis, Obstetric Performance and Perinatal Outcome. Rev. Bras. Ginecol. Obstet. 2018, 40, 740–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amigoni, A.; Mozzo, E.; Brugnaro, L.; Tiberio, I.; Pittarello, D.; Stellin, G.; Bonato, R. Four-side near-infrared spectroscopy measured in a paediatric population during surgery for congenital heart disease. Interact. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg. 2011, 12, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andres, R.; Saade, G.; Gilstrap, L.; Wilkins, I.; Witlin, A.; Zlatnik, F.; Hankins, G. Association between umbilical blood gas parameters and neonatal morbidity and death in neonates with pathologic fetal acidemia. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 181, 867–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 348: Umbilical cord blood gas and acid-base analysis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 108, 1319–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levene, M.I.; Fawer, C.-L.; Lamont, R.F. Risk factors in the development of intraventricular haemorrhage in the preterm neonate. Arch. Dis. Child. 1982, 57, 410–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yli, B.M.; Kjellmer, I. Pathophysiology of foetal oxygenation and cell damage during labour. Best. Pr. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 30, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P. Umbilical cord pH, blood gases, and lactate at birth: Normal values, interpretation, and clinical utility. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 228, S1222–S1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, E.M.; Naim, M.Y.; Lynch, J.M.; Goff, D.A.; Schwab, P.J.; Diaz, L.K.; Nicolson, S.C.; Montenegro, L.M.; Lavin, N.A.; Durduran, T.; et al. Sodium bicarbonate causes dose-dependent increases in cerebral blood flow in infants and children with single ventricle physiology. Pediatr. Res. 2013, 73, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matterberger, C.; Baik-Schneditz, N.; Schwaberger, B.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Mileder, L.; Pichler-Stachl, E.; Urlesberger, B.; Pichler, G. Blood Glucose and Cerebral Tissue Oxygenation Immediately after Birth—An Observational Study. J. Pediatr. 2018, 200, 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattersberger, C.; Baik-Schneditz, N.; Schwaberger, B.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Mileder, L.; Urlesberger, B.; Pichler, G. Acid-base and metabolic parameters and cerebral oxygenation during the immediate transition after birth—A two-center observational study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0283278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattersberger, C.; Schmölzer, G.M.; Urlesberger, B.; Pichler, G. Blood Glucose and Lactate Levels and Cerebral Oxygenation in Preterm and Term Neonates—A Systematic Qualitative Review of the Literature. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2021, 10, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bero, L.; Chartres, N.; Diong, J.; Fabbri, A.; Ghersi, D.; Lam, J.; Lau, A.; McDonald, S.; Mintzes, B.; Sutton, P.; et al. The risk of bias in observational studies of exposures (ROBINS-E) tool: Concerns arising from application to observational studies of exposures. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, C.J.; D’Antona, D.; Wyatt, J.S.; A Spencer, J.; Peebles, D.M.; O Reynolds, E. Fetal cerebral oxygenation measured by near-infrared spectroscopy shortly before birth and acid-base status at birth. Obstet. Gynecol. 1994, 50, 116–117. [Google Scholar]

- Naulaers, G. Cerebral tissue oxygenation index in very premature infants. Arch. Dis. Child.-Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002, 87, F189–F192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramamoorthy, C.; Tabbutt, S.; Kurth, C.D.; Steven, J.M.; Montenegro, L.M.; Durning, S.; Wernovsky, G.; Gaynor, J.W.; Spray, T.L.; Nicolson, S.C. Effects of Inspired Hypoxic and Hypercapnic Gas Mixtures on Cerebral Oxygen Saturation in Neonates with Univentricular Heart Defects. Anesthesiology 2002, 96, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andropoulos, D.B.; Stayer, S.A.; McKenzie, E.D.; Fraser, C.D.; Pigula, F.A.; Austin, E.H. Novel cerebral physiologic monitoring to guide low-flow cerebral perfusion during neonatal aortic arch reconstruction. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2003, 125, 491–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naulaers, G.; Morren, G.; Van Huffel, S.; Casaer, P.; Devlieger, H. Measurement of tissue oxygenation index during the first three days in premature born infants. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2003, 510, 379–383. [Google Scholar]

- von Siebenthal, K.; Keel, M.; Fauchère, J.C.; Dietz, V.; Haensse, D.; Wolf, U.; Helfenstein, U.; Bänziger, O.; Bucher, H.U.; Wolf, M. Variability of Cerebral Hemoglobin Concentration in Very Preterm Infants During the First 6 Hours of Life. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2005, 566, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Weiss, M.; Dullenkopf, A.; Kolarova, A.; Schulz, G.; Frey, B.; Baenziger, O. Near-infrared spectroscopic cerebral oxygenation reading in neonates and infants is associated with central venous oxygen saturation. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2005, 15, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, S.; Appleton, R.E.; Beirne, M.; Marson, A.G.; Weindling, A.M. Effect of carbon dioxide on background cerebral electrical activity and fractional oxygen extraction in very low birth weight infants just after birth. Pediatr. Res. 2005, 58, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Alfen-van Der Velden, A.A.E.M.; Hopman, J.C.W.; Klaessens, J.H.G.M.; Feuth, T.; Sengers, R.C.A.; Liem, K.D. Effects of Rapid versus Slow Infusion of Sodium Bicarbonate on Cerebral Hemodynamics and Oxygenation in Preterm Infants. Biol. Neonate. 2006, 90, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaramella, P.; Freato, F.; Quaresima, V.; Ferrari, M.; Bartocci, M.; Rubino, M.; Falcon, E.; Chiandetti, L. Surgical closure of patent ductus arteriosus reduces the cerebral tissue oxygenation index in preterm infants: A near-infrared spectroscopy and Doppler study. Pediatr. Int. 2006, 48, 305–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victor, S.; Appleton, R.E.; Beirne, M.; Marson, A.G.; Weindling, A.M. The relationship between cardiac output, cerebral electrical activity, cerebral fractional oxygen extraction and peripheral blood flow in premature newborn infants. Pediatr. Res. 2006, 60, 456–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaramella, P.; Saraceni, E.; Freato, F.; Falcon, E.; Suppiej, A.; Milan, A.; Laverda, A.M.; Chiandetti, L. Can tissue oxygenation index (TOI) and cotside neurophysiological variables predict outcome in depressed/asphyxiated newborn infants? Early Hum. Dev. 2007, 83, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvath, R.; Shore, S.; Schultz, S.E.; Rosenkranz, E.R.; Cousins, M.; Ricci, M. Cerebral and somatic oxygen saturation decrease after delayed sternal closure in children after cardiac surgery. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010, 139, 894–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishay, M.; Giacomello, L.; Retrosi, G.; Thyoka, M.; Nah, S.A.; McHoney, M.; De Coppi, P.; Brierley, J.; Scuplak, S.; Kiely, E.M.; et al. Decreased cerebral oxygen saturation during thoracoscopic repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia and esophageal atresia in infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2011, 46, 47–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunaydin, B.; Nas, T.; Biri, A.; Koc, E.; Koc, A.; McCusker, K. Effects of maternal supplementary oxygen on the newborn for elective cesarean deliveries under spinal anesthesia. J. Anesth. 2011, 25, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redlin, M.; Huebler, M.; Boettcher, W.; Kukucka, M. Minimizing intraoperative hemodilution by use of a very low priming volume cardiopulmonary bypass in neonates with transposition of the great arteries. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2011, 142, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bravo, M.D.C.; López, P.; Cabañas, F.; Pérez-Rodríguez, J.; Pérez-Fernández, E.; Pellicer, A. Acute effects of levosimendan on cerebral and systemic perfusion and oxygenation in newborns: An observational study. Neonatology 2011, 99, 217–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarti, A.; Manfrini, F.; Oggianu, A.; D’ORfeo, F.; Genova, S.; Silvano, R.; Pozzi, M. Non-invasive cerebral oximetry monitoring during cardiopulmonary bypass in congenital cardiac surgery: A starting point. Perfusion 2011, 26, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quarti, A.; Nardone, S.; Manfrini, F.; D’oRfeo, F.; Genova, S.; Silvano, R.; Pozzi, M. Effect of the adjunct of carbon dioxide during cardiopulmonary bypass on cerebral oxygenation. Perfusion 2013, 28, 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, J.; Möller, G. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy correlates to vital parameters during cardiopulmonary bypass surgery in children. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2013, 35, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pellicer, A.; Riera, J.; Lopez-Ortego, P.; Bravo, M.C.; Madero, R.; Perez-Rodriguez, J.; Labrandero, C.; Quero, J.; Buño, A.; Castro, L.; et al. Phase 1 study of two inodilators in neonates undergoing cardiovascular surgery. Pediatr. Res. 2013, 73, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conforti, A.; Giliberti, P.; Mondi, V.; Valfré, L.; Sgro, S.; Picardo, S.; Bagolan, P.; Dotta, A. Near infrared spectroscopy: Experience on esophageal atresia infants. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2014, 49, 1064–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer, J.P.; Parvez, B.; Chelala, M.; Alpan, G.; Lagamma, E.F. Monitoring regional tissue oxygen extraction in neonates <1250 g helps identify transfusion thresholds independent of hematocrit. J. Neonatal Perinatal Med. 2014, 7, 89–100. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.W.; Shin, W.J.; Park, I.; Chung, I.S.; Gwak, M.; Hwang, G.S. Splanchnic oxygen saturation immediately after weaning from cardiopulmonary bypass can predict early postoperative outcomes in children undergoing congenital heart surgery. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2014, 35, 587–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; McDonald, R.; Goyal, S.; Gossett, J.M.; Imamura, M.; Agarwal, A.; Butt, W.; Bhutta, A.T. Extubation failure in infants with shunt-dependent pulmonary blood flow and univentricular physiology. Cardiol. Young 2014, 24, 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintzer, J.P.; Parvez, B.; Alpan, G.; LaGamma, E.F. Effects of sodium bicarbonate correction of metabolic acidosis on regional tissue oxygenation in very low birth weight neonates. J. Perinatol. 2015, 35, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebius, M.J.; van der Laan, M.E.; Verhagen, E.A.; Roofthooft, M.T.; Bos, A.F.; Kooi, E.M. Cerebral oxygen saturation during the first 72h after birth in infants diagnosed prenatally with congenital heart disease. Early Hum. Dev. 2016, 103, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tytgat, S.H.A.J.; van Herwaarden, M.Y.A.; Stolwijk, L.J.; Keunen, K.; Benders, M.J.N.L.; de Graaff, J.C.; Milstein, D.M.J.; van der Zee, D.C.; Lemmers, P.M.A. Neonatal brain oxygenation during thoracoscopic correction of esophageal atresia. Surg. Endosc. Other Interv. Tech. 2015, 30, 2811–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torre, S.; Biondani, E.; Menon, T.; Marchi, D.; Franzoi, M.; Ferrarini, D.; Tabbì, R.; Hoxha, S.; Barozzi, L.; Faggian, G.; et al. Continuous Metabolic Monitoring in Infant Cardiac Surgery: Toward an Individualized Cardiopulmonary Bypass Strategy. Artif. Organs. 2016, 40, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix, L.M.L.; Weeke, L.C.; de Vries, L.S.; Groenendaal, F.; Baerts, W.; van Bel, F.; Lemmers, P.M.A. Carbon Dioxide Fluctuations Are Associated with Changes in Cerebral Oxygenation and Electrical Activity in Infants Born Preterm. J. Pediatr. 2017, 187, 66–72.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, C.L.; Oei, J.L.; Lui, K.; Schindler, T. Cerebral oxygenation as measured by Near-Infrared Spectroscopy in neonatal intensive care: Correlation with arterial oxygenation. Acta Paediatr. 2017, 106, 1073–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissen, M.; Cernaianu, G.; Thränhardt, R.; Vahdad, M.R.; Barenberg, K.; Tröbs, R.-B. Does metabolic alkalosis influence cerebral oxygenation in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J. Surg. Res. 2017, 212, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neunhoeffer, F.; Warmann, S.W.; Hofbeck, M.; Müller, A.; Fideler, F.; Seitz, G.; Schuhmann, M.U.; Kirschner, H.; Kumpf, M.; Fuchs, J. Elevated intrathoracic CO2 pressure during thoracoscopic surgery decreases regional cerebral oxygen saturation in neonates and infants-A pilot study. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2017, 27, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weeke, L.C.; Dix, L.M.L.; Groenendaal, F.; A Lemmers, P.M.; Dijkman, K.P.; Andriessen, P.; de Vries, L.S.; Toet, M.C. Severe hypercapnia causes reversible depression of aEEG background activity in neonates: An observational study. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2017, 102, F383–F388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katheria, A.C.; Brown, M.K.; Hassan, K.; Poeltler, D.M.; A Patel, D.; Brown, V.K.; Sauberan, J.B. Hemodynamic effects of sodium bicarbonate administration. J. Perinatol. 2017, 37, 518–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, M.; Uchida, T.; Itoh, H.; Suzuki, H.; Niwayama, M.; Kanayama, N. Tissue oxygen saturation levels from fetus to neonate. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2017, 43, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janaillac, M.; Beausoleil, T.P.; Barrington, K.J.; Raboisson, M.-J.; Karam, O.; Dehaes, M.; Lapointe, A. Correlations between near-infrared spectroscopy, perfusion index, and cardiac outputs in extremely preterm infants in the first 72 h of life. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2018, 177, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mebius, M.; Verhagen, E.; van der Laan, M.; Bos, A. Cerebral oxygen saturation and extraction in neonates with persistent pulmonary hypertension during the first 72 hours of life. Arch. Dis. Child. 2012, 97, A481–A482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Polavarapu, S.R.; Fitzgerald, G.D.; Contag, S.; Hoffman, S.B. Utility of prenatal Doppler ultrasound to predict neonatal impaired cerebral autoregulation. J. Perinatol. 2018, 38, 474–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beausoleil, T.P.; Janaillac, M.; Barrington, K.J.; Lapointe, A.; Dehaes, M. Cerebral oxygen saturation and peripheral perfusion in the extremely premature infant with intraventricular and/or pulmonary haemorrhage early in life. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costerus, S.; Vlot, J.; Van Rosmalen, J.; Wijnen, R.; Weber, F. Effects of Neonatal Thoracoscopic Surgery on Tissue Oxygenation: A Pilot Study on (Neuro-) Monitoring and Outcomes. Eur. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2019, 29, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, L.; Mahmoudzadeh, M.; Gondry, J.; Foulon, A.; Wallois, F. Dynamics of cortical oxy genation during immediate adaptation to extrauterine life. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loomba, R.S.; Villarreal, E.G.; Dyamenahalli, U.; Farias, J.S.; Flores, S. Acute Effects of Sodium Bicarbonate in Children with Congenital Heart Disease with Biventricular Circulation in Non-cardiac Arrest Situations. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2022, 43, 1723–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knieling, F.; Cesnjevar, R.; Regensburger, A.P.; Wagner, A.L.; Purbojo, A.; Dittrich, S.; Münch, F.; Neubert, A.; Woelfle, J.; Jüngert, J.; et al. Transfontanellar Contrast-enhanced US for Intraoperative Imaging of Cerebral Perfusion during Neonatal Arterial Switch Operation. Radiology 2022, 304, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savorgnan, F.; Loomba, R.S.; Flores, S.; Rusin, C.G.; Zheng, F.; Hassan, A.M.; Acosta, S. Descriptors of Failed Extubation in Norwood Patients Using Physiologic Data Streaming. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2023, 44, 396–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanasmaz, H.; Akan, A.; Yalçın, Ö.; Ölçücü, M.T.; Onar, S.; Kazanasmaz, Ö. Cerebral Tissue Oxygen Saturation Measurements in Perinatal Asphyxia Cases Treated with Therapeutic Hypothermia. Ther. Hypothermia Temp. Manag. 2023, 13, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, K.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, W.; Yang, A. Value of brain tissue oxygen saturation in neonatal respiratory distress syndrome: A clinical study. Eur. J. Transl. Myol. 2024, 34, 11863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dusleag, M.; Urlesberger, B.; Schwaberger, B.; Baik-Schneditz, N.; Schlatzer, C.; Wolfsberger, C.H.; Pichler, G. Acid base and metabolic parameters of the umbilical cord blood and cerebral oxygenation immediately after birth. Front. Pediatr. 2024, 12, 1385726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, J.A.; Galbraith, R.S.; Raymond, M.J.; Derrick, E.J. Cerebral blood flow velocity in term newborns following intrapartum fetal asphyxia. Acta Paediatr. Int. J. Paediatr. 1994, 83, 1012–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, J.D.; Margolis, T.I.; Kim, D. Mechanism of diminished contractile response to catecholamines during acidosis. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 1988, 254, H20–H27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noori, S.; Wu, T.W.; Seri, I. PH effects on cardiac function and systemic vascular resistance in preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 2013, 162, 958–963.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiberg, N.; Källén, K.; Olofsson, P. Base deficit estimation in umbilical cord blood is influenced by gestational age, choice of fetal fluid compartment, and algorithm for calculation. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 195, 1651–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.W.; Shackford, S.R.; Holbrook, T.L. Base deficit as a sensitive indicator of compensated shock and tissue oxygen utilization. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1991, 173, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, H.G.; Howe, C.A.; Chalifoux, C.J.; Hoiland, R.L.; Carr, J.M.J.R.; Brown, C.V.; Patrician, A.; Tremblay, J.C.; Panerai, R.B.; Robinson, T.G.; et al. Arterial carbon dioxide and bicarbonate rather than pH regulate cerebral blood flow in the setting of acute experimental metabolic alkalosis. J. Physiol. 2021, 599, 1439–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| First Author, Years | Study Design | Neonates | n | Device | NIRS Measurement, Time Point | Blood Sample, Time Point | NIRS Measurement, Duration | TOI or crSO2 or FTOE | pH, Mean Value | Association, Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldrich C.J., 1994 [38] | Prospective observational study | Fetus at delivery | 33 | n.r. | During the delivery | Immediately after birth | 10 min period 30 min before birth | n.r | n.r. | Yes Positive |

| Naulaers G., 2002 [39] | Observational study | Preterm neonates | 15 | NIRO 300 | Day 1–3 after birth | Before and after NIRS measurements | 30 min | Day 1: 57% Day 2: 66.1% Day 3: 76.1% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Ramamoorthy C., 2002 [40] | Randomized crossover trial | Preterm and term neonates | 15 | NIM | Day 3 after birth | At the end of base, 17% fractional inspired O2, second base, and 3% fractional inspired CO2 | 10–20 min period at base, during 17% fractional inspired O2, at second base, and during 3% fractional inspired CO2 | At base: 53%; 17% fractional inspired O2: 53%. At second base: 56%; 3% fractional inspired CO2: 68% | At base: 7.43; during 17% fractional inspired O2: 7.46; at second base: 7.45; during 3% fractional inspired CO2: 7.34 | n.r. |

| Andropoulos D.B., 2003 [41] | Prospective observational study | n.r. | 34 | INVOS 5100 | Day 13 (2–128) after birth | Every 10 to 20 min during bypass | At baseline full cardiopulmonary bypass flow, during low-flow cerebral perfusion, after repair full flow | At baseline: 87%; during low-flow cerebral perfusion: 88%; after full-flow repair: 86% | At baseline: 7.49; during low-flow cerebral perfusion: 7.52; after full-flow repair: 7.44 | n.r. |

| Naulaers G., 2003 [42] | Observational study | Preterm neonates | 15 | NIRO 300 | Day 1–3 after birth | Before and after NIRS measurements | 30 min | Day 1: 57% Day 2: 66.1% Day 3: 76.1% | n.r. | n.r. |

| von Siebenthal K., 2005 [43] | Observational study | Preterm neonates | 28 | Critikon Cerebral Oxygenation Monitor 2020 | Hours 0–6 after birth | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. | 7.26 | No |

| Weiss M., 2005 [44] | Prospective observational | Preterm and term neonates | 155 | NIRO 300 | Day 12 (0–365) after birth | During NIRS measurements | 30 min in 1 min intervals | 60.5% | 7.39 | No |

| Victor S., 2005 [45] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 22 | NIRO 500 | Day 1–3 after birth | Midway through an EEG recording | Once a day during EEG measurement from day 1 to 3 after birth | n.r. | Day 1: 7.3 Day 2: 7.3 Day 3: 7.3 | n.r. |

| van Alfen-van der Velden A.A.E.M., 2006 [46] | Randomized controlled study | Preterm neonates | 29 | OXYMON | n.r. | Before and 30 min after completion of HCO3 administration | From 10 min before until 45 min after HCO3 administration | n.r. | Before: 7.29 and 7.29; After: 7.33 and 7.35 | No |

| Zaramella P., 2006 [47] | Observational study | Preterm neonates | 16 | NIRO-300 | Day 7–33 after birth | 35th min before and 27th min after surgical manoeuvres | 27th min before and 14th and the 35th min after surgical manoeuvres | 35 min before manoeuvres: 61.1%; 14 min after manoeuvres: 56.6%; 27 min after manoeuvres: 55.8% | 35 min before manoeuvres: 7.27; 27 min after manoeuvres: 7.35 | n.r. |

| Victor S., 2006 [48] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 40 | NIRO 500 | Day 1–4 after birth | During NIRS measurements | One hour every day during the first four days after birth | Day 1: FTOE 0.35; Day 2: FTOE 0.29; Day 3: FTOE 0.30; Day 4: FTOE 0.30 | LVO: 7.33 RVO: 7.33 | n.r. |

| Zaramella P., 2007 [49] | Case–control study | Preterm and term neonates | 22 | NIRO-300 | Day 1 after birth | Within 1 h after birth | n.r. | Depressed/asphyxiated group: 75.3%; control group: 66.5%; normal 1-year outcome: 74.7%; abnormal 1-year outcome: 80.1% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Horvath R., 2009 [50] | Retrospective study | Neonates, infants and children | 36 | INVOS 5100B | Day 10 (1–510) after birth | 24 h before, during and 24 h after chest closure | 24 h before, during, and 24 h after chest closure | Before chest closure: 62.4%; after chest closure: 56.9% | Before chest closure: 7.41 after chest closure: 7.41 | n.r. |

| Bishay M., 2011 [51] | Prospective observational cohort study | Neonates and infants | 8 | INVOS | Day 0–314 after birth | Preoperatively, start, during, and end of surgery, 12 and 24 h postoperatively | Preoperatively, start, during, and end of surgery, 12 and 24 h postoperatively | Start: 87%; end: 75%; 12 h post-surgery: 74%; 24 h post-surgery: 73% | Start: 7.19; intraoperatively: 7.05; end: 7.28 | n.r. |

| Gunaydin B., 2011 [52] | Prospective randomized study | Term neonates | 90 | INVOS 5100 | Min 0–5 after birth | After the delivery | 1 interval during first 5 min after birth | n.r. | U.A. pH: 7.31, 7.29, and 7.24; U.V. pH: 7.35, 7.35, and 7.29 | n.r. |

| Redlin M., 2011 [53] | Retrospective study | Neonates | 23 | NIRO 200 | Day 2–17 after birth | Pre- and postoperatively, beginning, 15 min intervals during and end of CPB | Continuously before and after surgery and CPB | n.r. | Before surgery: 7.43 and 7.48; start CPB: 7.38 and 7.42; during CPB: 7.39 and 7.40; end of CPB: 7.40 and 7.43; after CPB: 7.41 and 7.44 | n.r. |

| Bravo M.D.C., 2011 [54] | Prospective uncontrolled case series observational study | Neonates and infants | 16 | NIRO-300 | Day 5–42 after birth | Beginning and end of the study | Continuously during 48 h in 20 s intervals | Δ –2.56% | Initial: 7.36; final: 7.42 | n.r. |

| Quarti A., 2011 [55] | Prospective observational study | Neonates, infants, children, and adults | 40 | INVOS 5100C | Year 8.4 (11 days—60 years) | Before CPB, during cooling, re-warming, weaning, and after CPB | During cardiopulmonary bypass surgery | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Amigoni A., 2011 [26] | Prospective observational study | Neonates, infants, and children | 16 | INVOS 5100C | Month 3.5 (0–66) after birth | Before and after surgical procedure and at start, middle, and end of CPB | Continuously during surgical procedure | Basal 55%; before CPB 42%; CPB start 42.5%; CPB middle 40.5%; CPB before stop 41%; CPB re-warming 46%; after CPB 42.5%; before discharge 50% | Basal: 7.41; CBP start: 7.45; CBP middle: 7.41; CPB before stop: 7.39; after CPB: 7.38 | Yes Negative |

| Quarti A., 2013 [56] | Prospective observational study | Neonates and infants | 19 | INVOS 5100C | Day 26 (6–120) after birth | Before CPB, at CPB starting, before and during CO2 flooding, after stopping CO2, and at the end of CPB | Before CPB, at CPB starting, before and during CO2 flooding, after stopping CO2 and at the end of CPB | Before CPB 54.7%; during CPB 47.7%; before CO2 52.9%; during CO2 63.4%; after CO2 55.8%; after CPB 51.9% | Before CPB: 7.36; during CPB: 7.54; before CO2: 7.50; during CO2: 7.41; after CO2: 7.46; after CPB: 7.38 | n.r. |

| Menke J., 2014 [57] | Prospective observational study | Neonates, infants, and children | 10 | Critikon Cerebral RedOx Monitor 2020 | Year 0–9 | 5 to 20 min intervals | Continuously before and during CPB surgery | 60.0% | 7.39 | No |

| Pellicer A., 2013 [58] | Pilot, phase 1 randomized, blinded clinical trail | Neonates and infants | 20 | NIRO 300 | Day 6–34 after birth | Before surgery, 6 h intervals during 24 h, 48, and 96 h | Immediately after surgery and continuously during the first day, for 4 h at 48 and 96 h post-surgery | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Conforti A., 2014 [59] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 13 | INVOS 5100C | n.r. | Preoperatively, interoperatively, end of surgery, 24 and 48 h postoperatively | Continuously 12 h before to 48 h after surgery | n.r. | n.r. | n.r. |

| Mintzer J.P., 2014 [60] | Prospective observational non-interventional study | Preterm neonates | 23 | INVOS 5100C | Day 3 (0–7) after birth | Before and after RBC transfusion | Continuously during the 7 days | RBC transfused vs. non-transfused Pre-RBC 69% vs. 79% Post-RBC 76% vs. 79% Post-RBC (24 h) 68% vs. 75% | RBS transfused group: 7.28; non-Transfused group: 7.33 | n.r. |

| Kim J.W., 2014 [61] | Retrospective study of prospective data | Neonates, infants, and children | 73 | INVOS 5100B | Month 3 (0.1–72) | After separation from CPB | Continuously after induction of anesthesia in a 5 min period | 57% | 7.35 | n.r. |

| Gupta P., 2014 [62] | Retrospective observational study | Neonates | 15 | n.r. | Day 19 (12–22) after birth | Before extubation | 6 h before and 6 h after extubation | Extubation failure: 56.0% and 57.0%; extubation success: 61.0% and 63.0% | Extubation failure: 7.4 and 7.4; extubation success: 7.4 and 7.4 | n.r. |

| Mintzer J.P., 2015 [63] | Prospective observational cohort study | Preterm neonates | 12 | INVOS 5100C | Day 1 to 7 after birth | During NIRS measurements | Continuously 1 h prior and 2 h immediately following procedure | 74% | Before: 7.23; after: 7.31 | No |

| Mebius M.J., 2016 [64] | Retrospective study | Preterm and term neonates | 56 | INVOS 4100c and 5100c | Day 0–3 after birth | Daily | Continuously within the first 72 h after birth | Day 1. 58.5% Day 2. 62.5% Day 3. 61.5% | 7.29 and 7.31 | No |

| Tytgat S.H.A.J., 2016 [65] | Single-center prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 15 | INVOS 4100-5100 | Days 2 (1–7) after birth | Baseline, after anesthesia induction, after CO2-insufflation, before CO2 exsufflation, and postoperatively 6, 12, and 24 h | Continuously at baseline, after anesthesia induction, 30 min after CO2 insufflation, 30 min before exsufflation, postoperatively 6, 12 and 24 h | After anesthesia induction: 77%; before CO2 insufflation: 73% | Baseline: 7.33; after CO2-insufflation: 7.25 | n.r. |

| Torres S., 2016 [66] | Prospective pilot study | Neonates, infants, and young children | 31 | INVOS 5100C | Day 11–2433 after birth | T0: During calibration T1: 5 min after aortic cross-clamp T2: 5 min after test start T3: At the end of the 20 min test T4: After clamp removal | Every 5 min during surgery on left and right hemisphere | Left Right T0: 55.3–55.2% T1: 55.8–55.1% T2: 53.9–52.9% T3: 55.3–54.2% T4: 55.5–54.8% | T0: 7.42 T1: 7.45 T2: 7.44 T3: 7.45 T4: 7.42 | n.r. |

| Dix L.M.L., 2017 [67] | Retrospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 38 | INVOS 5100C | Day 0–3 after birth | n.r. | Before, during and after fluctuation of CO2 | Before: 66.0% and 69.6%; during: 71.1% and 61.9%; after: 66.8% and 68.4% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Hunter C.L., 2017 [68] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 22 | NONIN SenSmart X-100 oximetry system | Day 6.2 (1–36) after birth | Single time point during NIRS measurements | 10 min before and after blood sample | Between 70% and 80% | n.r. | No |

| Nissen M., 2017 [69] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates and infants | 12 | INVOS 5100C | Day 43 (20–74) after birth | During NIRS measurements, once before restoration, and before and after surgery | Before restoration of metabolic alkalosis, 3 h before, 16 and 24 h after surgery in 30 min intervals | Before restoration 72.74%; before surgery 77.89%; after surgery 80.79% | n.r. | Yes negative |

| Neunhoeffer F., 2017 [70] | Prospective observational study | Neonates and infants | 15 | O2C device | Day 5 (1–150) and day 37 (1–68) after birth | Before operation, half-hourly during operation, and after surgery | Continuously before, during and after surgery | Before: 61.85% vs. 65.02%; during: 66.75% vs. 67.62%; after: 66.75% vs. 69.87% | Before: 7.38 vs. 7.39; during: 7.3 vs. 7.38; after: 7.32 vs. 7.34 | n.r. |

| Weeke L.C., 2017 [71] | Observational retrospective cohort study | Preterm and term neonates | 25 | INVOS 4100-5100 | Hour 120 (46.5–441.4) and hour 20.7 (7.2–131) after birth | 4 h intervals | Continuously 10 min before, during and/or after hypercapnia | Before: 66.54%; during: 68.36%; after: 65.91% | Before 7.26; during 7.02; after 7.27 | n.r. |

| Katheria A.C., 2017 [72] | Retrospective study | Preterm neonates | 36 | FORE-SIGHT | Day 1 after birth | Before and 1 h within HCO3 administration | Continuously in 10 min periods before, during and after HCO3 administration | n.r. | Before: 7.23; after: 7.28 | Yes Positive |

| Mukai M., 2017 [73] | n.r. | Term neonates | 35 | KN-15, ASTEM | From the second stage of labor to 5 min after birth | During NIRS measurement | Continuously during second stage of labor, crowning, immediately after birth, after the first cry, 1,3, and 5 minutes after the delivery | Second stage of labor: 50.3%; crowning: 32.7%; immediately after birth: 30.0%; after the first cry: 31.6%; 1 min: 50.6%; 3 min: 54.4%; 5 min: 56.8% | 7.297 | n.r. |

| Janaillac M., 2018 [74] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 20 | INVOS 5100 | Day 0–3 after birth | During NIRS measurements every 6 to 8 h | Continuously for 72 h in 30 min intervals | 6 h: 69% 24 h: 76% 48 h: 71% 72 h: 68% | 6 h: 7.29 24 h: 7.28 48 h: 7.25 72 h: 7.27 | No |

| Mebius M.J., 2018 [75] | Prospective observational study | Term neonates | 6 | n.r. | Day 0–3 after birth | n.r. | n.r. | Day 1: 77.5% and 0.19 Day 2: 82% and 0.12 Day 3: 78% and 0.16 | n.r. | No |

| Polavarapu S.R., 2018 [76] | Prospective cohort study | Preterm neonates | 47 | INVOS 5100C | Day 1 to 4 after birth | Cord blood analysis at time of delivery | Continuously during the first 96 h after birth | n.r. | U.A. pH: 7.24; U.V. pH: 7.30 | n.r. |

| Beausoleil T.P., 2018 [77] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 19 | INVOS 5100 | Day 0–3 after birth | During NIRS measurements every 6 to 8 h | Continuously during the first 72 h after birth | n.r. | PH-IVH: 7.24 Healthy controls: 7.28 | n.r. |

| Costerus S., 2019 [78] | Prospective observational pilot study | Term neonates | 10 | INVOS 5100C | Day 1.3–4.5 after birth | Baseline, every 30 min during surgery of CDH and EA | Baseline, every 30 min during insufflation | CDH baseline 82% EA baseline 91% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Leroy L., 2021 [79] | Prospective observational study | Term neonates | 20 | NIRO-200NX | Minute 2 to 10 after birth | Immediately after birth | 3 min to 10 min after birth | n.r. | 7.28 | Yes negative |

| Loomba R.S., 2022 [80] | Retrospective single-center study | n.r. | 23 | FORE-SIGHT | Month 15.4 ±30.8 | Baseline, 1 hour after HCO3 administration, and 2 hours after HCO3 administration | Baseline, 1 h after HCO3 administration, 2 h after HCO3 administration | Baseline: 64% 1 h after HCO3 administration: 65%; 2 h after HCO3 administration: 65% | Baseline: 7.24; 1 h after HCO3 administration: 7.31; 2 h after HCO3 administration: 7.30 | No |

| Knieling F., 2022 [81] | Prospective single-center cross-sectional diagnostic study | Term neonates | 12 | n.r. | Day 6.9 (2–16) after birth | Before (T1) and after (T5) surgery, during high flow of the CPB at 37 °C (T2), and at 25–28 °C (T3), during low flow of the CPB at 2–28 °C (T4) | Before (T1) and after (T5) surgery, during high flow of the CPB at 37 °C (T2), & at 25–28 °C (T3), during low flow of the CPB at 25–28 °C (T4) | T1: 44% T2: 53% T3: 67% T4: 62% T5: 76% | T1: 7.4 T2: 7.4 T3: 7.3 T4: 7.2 T5: 7.4 | n.r. |

| Savorgnan F., 2023 [82] | Single-center, retrospective analysis | Term neonates | 134 | n.r. | Day 7 (4–10) after birth | Baseline and within 6 h before extubation | Baseline, 10 min after extubation & 120–180 min post-extubation | Baseline: 57.9%; 10 min after extubation: −1.7% × min; 120–180 min post-extubation: −0.4% × min | Baseline: 7.38; within 6 h before extubation: 7.40 | n.r. |

| Mattersberger C., 2023 [34] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 157 | INVOS 5100 | Min 15 after birth | Between 10 to 20 min after birth | Continuously at 15th minute after birth | Preterm neonates: 82%; term neonates: 83%; preterm neonates: 0.13; term neonates: 0.14 | Preterm neonates: 7.267; term neonates: 7.293 | No in term neonates Yes in preterm neonates; crSO2: positive; FTOE: negative |

| Kazanasmaz H., 2023 [83] | Prospective observational study | Term neonates | 84 | MASIMO O3 | Hour < 6 after birth | Immediately after birth | Continuously for 10 min before starting therapeutic hypothermia | PA group: 67% and 67%; control group: 80% and 79% | 6.93 | Yes Positive |

| Cheng K. 2024 [84] | Randomized control study | Preterm neonates | 98 | n.r. | Day 4 to 9 after birth | Day 0–5 | within the first 72 h, 96 h and 120 h | 71.15% | 7.25 | n.r. |

| Dusleag M. 2024 [85] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 77 | INVOS 5100 | During the first 15 min after birth | Immediately after birth | during the first 15 min after birth | Preterm neonates: 44%; term neonates: 62.2% | Preterm neonates: 7.32; term neonates: 7.32 | No |

| First Author, Years | Study Design | Neonates | n | Device | NIRS Measurement, Time Point | Blood Sample, Time Point | NIRS Measurement, Duration | TOI or crSO2 or FTOE | Base Excess or Base Deficit, Mean Value | Association, Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldrich C.J., 1994 [38] | Prospective observational study | Fetus at delivery | 33 | n.r. | During the delivery | Immediately after birth | 10 min period 30 min before birth | n.r | n.r. | Yes Negative |

| Ramamoorthy C., 2002 [40] | Randomized crossover trial | Preterm and term neonates | 15 | NIM | Day 3 (2–14) after birth | At the end of base; 17% fractional inspired O2; second base; and 3% fractional inspired CO2 | 10–20 min period at base; during 17% fractional inspired O2; second base; and during 3% fractional inspired CO2 | At base: 53%l 17% fractional inspired O2: 53%; second base: 56%; 3% fractional inspired CO2: 68% | At base: 0.3; 17% fractional inspired O2: 0.1; second base: 0.6; 3% fractional inspired CO2: 1.3 | n.r. |

| Andropoulos D.B., 2003 [41] | Prospective observational study | n.r. | INVOS 5100 | Day 13 (2–128) after birth | Every 10 to 20 min during bypass | At baseline full cardiopulmonary bypass flow; during low-flow cerebral perfusion; and after repair full flow | At baseline: 87%; during low-flow cerebral perfusion: 88%; after repair full flow: 86% | At baseline: +1.0; during low-flow cerebral perfusion: +0.1; after full-flow repair: −1.5 | n.r. | |

| Weiss M., 2005 [44] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 155 | NIRO 300 | Day 12 (0–365) after birth | During NIRS measurements | 30 min in 1 min intervals | 60.5% | 0.8 mmol/L | No |

| Victor S., 2005 [45] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 22 | NIRO 500 | Day 1–3 after birth | Midway through an EEG recording | Once a day during EEG measurement from day 1 to 3 after birth | n.r. | −1.9 | n.r. |

| van Alfen-van der Velden A.A.E.M., 2006 [46] | Randomized controlled study | Preterm neonates | 29 | OXYMON | n.r. | Before and 30 min after completion of HCO3 administration | From 10 min before until 45 min after HCO3 administration | n.r. | Before: −7.6 l/l and −7.5 l/l; after: −4.3 l/l and −4.1 l/l | No |

| Victor S., 2006 [48] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 40 | NIRO 500 | Day 1–4 after birth | Once during NIRS measurements | 1 h every day during the first four days after birth | Day 1. FTOE: 0.35 Day 2. FTOE: 0.29 Day 3. FTOE: 0.30 Day 4. FTOE: 0.30 | 2.0 (9.6 to −1.3) | n.r. |

| Zaramella P., 2007 [49] | Case–control study | Preterm and term neonates | 22 | NIRO-300 | Day 1 after birth | Within 1 h after birth | n.r. | Depressed/asphyxiated group: 75.3%; control group: 66.5%; neonates with normal one-year outcome: 74.7%; neonates with abnormal one-year outcome: 80.1% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Horvath R., 2009 [50] | Retrospective study | Neonates, infants and children | 36 | INVOS 5100B | Day 10 (1–510) after birth | 24 h before chest closure, during chest closure, and 24 h after chest closure | 24 h before chest closure; during chest closure; and 24 h after chest closure | Before chest closure: 62.4%; after chest closure: 56.9% | Before chest closure: 2.1; after chest closure: 1.5 | n.r. |

| Gunaydin B., 2011 [52] | Prospective randomized study | Term neonates | 90 | INVOS 5100 | Min 0–5 after birth | After the delivery | 1 interval during first 5 min after birth | n.r. | U.A. BE: −2.52, −2.4, and −4.3 mmol/L; U.V. BE: −3.27, −3.18, and −4.8 mmol/L | n.r. |

| Redlin M., 2011 [53] | Retrospective study | Neonates | 23 | NIRO 200 | Day 2–17 after birth | Pre- and postoperatively At the beginning; 15 min intervals during and at the end of CPB | Continuously before and after surgery and CPB | n.r. | Before surgery: −0.5 and 0.5 mmol/L; start CPB: −4.4 and −2.0 mmol/L; during CPB: −4.1 and −1.7 mmol/L; end of CPB: −3.9 and −0.2 mmol/L; after CPB: −3.2 and −0.6 mmol/L | n.r. |

| Bravo M.D.C., 2011 [54] | Prospective, uncontrolled, case series observational study | Neonates and infants | 16 | NIRO-300 | Day 5–42 after birth | Beginning and end of the study | Continuously during 48 h in 20 s intervals | Δ –2.56% | Initial: 0.29; final: 2.6 | n.r. |

| Menke J., 2014 [57] | Prospective observational study | Neonates and children | 10 | Critikon Cerebral RedOx Monitor 2020 | Years 0–9 | 5–20 min intervals | Continuously before and during CPB surgery | 60.0% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Mintzer J.P., 2014 [60] | Prospective observational non-interventional study | Preterm neonates | 23 | INVOS 5100C | Day 3 (0–7) after birth | 60 min before, during, and 120 min after RBC transfusion | Continuously during the seven days | RBC transfused vs. non-transfused Pre-RBC 69% vs. 79% Post-RBC 76% vs. 79% Post-RBC (24 h) 68% vs. 75% | RBS transfused group: 4.8 mmol/L; non-transfused group: 4.9 mmol/L | n.r. |

| Gupta P., 2014 [62] | Retrospective observational study | Neonates | 15 | n.r. | Day 19 (12–22) after birth | Before extubation | 6 h before and 6 h after extubation | Extubation failure: 56.0% and 57.0%; extubation success: 61.0% and 63.0% | Extubation failure: 3.7 and 2.1; extubation success: 3.1 and 1.4 | n.r. |

| Mintzer J.P., 2015 [63] | Prospective observational cohort study | Preterm neonates | 12 | INVOS 5100C | Day 3 (2–5) after birth | During NIRS measurements | Continuously 1 h prior and 2 h immediately following procedure | 74% | Before: 7.6; after 3.4 | No |

| Torres S., 2016 [66] | Prospective pilot study | Neonates, infants, and young children | 31 | INVOS 5100C | Day 11–2433 after birth | T0: during calibration; T1: 5 min after aortic cross-clamp; T2: 5 min after test start; T3: at the end of the 20 min test; T4: after clamp removal | Every 5 min during surgery on left and right hemispheres | Left Right T0: 55.3–55.2% T1: 55.8–55.1% T2: 53.9–52.9% T3: 55.3–54.2% T4: 55.5–54.8% | T0: −1.1 mmol/L T1: 0.1 mmol/L T2: 0.9 mmol/L T3: 0.5 mmol/L T4: 0.3 mmol/L | n.r. |

| Hunter C.L., 2017 [68] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 22 | NONIN SenSmart X-100 oximetry system | Day 6.2 (1–36) after birth | Single time point during NIRS measurements | 10 min before and after blood sampling | Between 70% and 80% | n.r. | No |

| Nissen M., 2017 [69] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates and infants | 12 | INVOS 5100C | Days 43 (20–74) after birth | During NIRS measurements, once before restoration, and before and after surgery | Before restoration of metabolic alkalosis; 3 h before; 16 and 24 h after surgery in 30 min intervals | Before restoration: 72.74%; before surgery: 77.89%; after surgery: 80.79% | n.r. | Yes Negative |

| Weeke L.C., 2017 [71] | Observational retrospective cohort study | Preterm and term neonates | 25 | INVOS 4100-5100 | Hour 120 (46.5–441.4) and hour 20.7 (7.2–131) | 4 h intervals | Continuously 10 min before; during and/or after hypercapnia | Before: 66.54%; during: 68.36%; after: 65.91%; | Before: −4.39 mmol/L; during: −5.39 mmol/L; after: −4.22 mmol/L | n.r |

| Katheria A.C., 2017 [72] | Retrospective study | Preterm neonates | 36 | FORE-SIGHT | Day 1 after birth | Before and 1 h within HCO3 administration | Continuously in 10 min periods before, during, and after HCO3 administration | n.r. | Before: −8.9; After: −6.8 | Yes Negative |

| Costerus S., 2019 [78] | Prospective observational pilot study | Term neonates | 10 | INVOS 5100C | Day 1.3–4.5 after birth | Baseline, every 30 min during surgery of CDH and EA | Baseline and every 30 min during insufflation | CDH baseline: 82%; EA baseline: 91% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Leroy L., 2021 [79] | Prospective observational study | Term neonates | 20 | NIRO-200NX | Minute 1.75 after birth | Immediately after birth | From minute 3 to 10 after birth | n.r. | −2.3 mmol/L | Yes Negative |

| Mattersberger C., 2023 [34] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 157 | INVOS 5100 | During and immediately after the delivery | Between 10 and 20 min after birth | Continuously at 15th minute after birth | Preterm neonates 82% and term neonates 83%; preterm neonates 0.13 and term neonates 0.14 | Preterm neonates—2.3 mmol/L Term; neonates—0.9 mmol/L | No in term neonates; Yes in preterm neonates crSO2; positive FTOE; negative |

| Kazanasmaz H., 2023 [83] | Prospective observational study | Term neonates | 84 | MASIMO O3 | Hour < 6 after birth | Immediately after birth | Continuously for 10 min before starting therapeutic hypothermia | PA group: 67% and 67% Control group: 80% and 79% | 17.8 mmol/L | No |

| Dusleag M. 2024 [85] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 77 | INVOS 5100 | During the first 15 min after birth | Immediately after birth | during the first 15 min after birth | Preterm neonates: 44%; term neonates; 62.2% | Preterm neonates: 0.7 mmol/L; term neonates: 1.37 mmol/L | No |

| First Author, Years | Study Design | Neonates | n | Device | NIRS Measurement, Time Point | Blood Sample, Time Point | NIRS Measurement, Duration | TOI or crSO2 or FTOE | HCO3, Mean Value | Association, Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naulaers G., 2002 [39] | Observational study | Preterm neonates | 15 | NIRO 300 | Day 1–3 after birth | Before and after NIRS measurements | 30 min | Day 1. 57% Day 2. 66.1% Day 3. 76.1% | n.r. | n.r. |

| van Alfen-van der Velden A.A.E.M., 2006 [46] | Randomized controlled study | Preterm neonates | 29 | OXYMON | n.r. | Before and 30 min after completion of HCO3 administration | From 10 min before until 45 min after HCO3 administration | n.r. | Before: 18.4 mmol/L and 18.3 mmol/L; after: 21.1 mmol/L and 21.0 mmol/L | No |

| Bravo M.D.C., 2011 [54] | Prospective uncontrolled case series observational study | Neonates and infants | 16 | NIRO-300 | Day 5–42 after birth | Beginning and end of the study | Continuously during 48 h in 20 s intervals | Δ –2.56% | Initial: 27.2 mmol/L; final: 27.2 mmol/L | n.r. |

| Mintzer J.P., 2015 [63] | Prospective observational cohort study | Preterm and term neonates | 12 | INVOS 5100C | Day 3 (2–5) after birth | During NIRS measurements | Continuously 1 h prior and 2 h immediately following the procedure | 74% | 4.5 mL/kg −1 | No |

| Dix L.M.L., 2017 [67] | Retrospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 38 | INVOS 5100C | Day 0–3 after birth | n.r. | Before, during and after fluctuation of CO2 | Before: 66.0% and 69.6%; during: 71.1% and 61.9%; after: 66.8% and 68.4% | n.r. | n.r. |

| Hunter C.L., 2017 [68] | Prospective observational study | Preterm neonates | 22 | NONIN SenSmart X-100 oximetry system | Day 6.2 (1–36) after birth | Single time point during NIRS measurements | 10 min before and after blood sample | Between 70% and 80% | n.r. | No |

| Nissen M., 2017 [69] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates and infants | 12 | INVOS 5100C | Day 43 (20–74) after birth | During NIRS measurements, once before restoration, and before and after surgery | Before restoration of metabolic alkalosis, 3 h before, and 16 and 24 h after surgery in 30 min intervals | Before restoration: 72.74%; before surgery: 77.89%; after surgery: 80.79% | n.r. | Yes Negative |

| Weeke L.C., 2017 [71] | Observational retrospective cohort study | Preterm and term neonates | 25 | INVOS 4100-5100 | Hour 120 (46.5–441.4) and hour 20.7 (7.2–131) | 4 h intervals | Continuously 10 min before and during and/or after hypercapnia | Before: 66.54%; during: 68.36%; after: 65.91% | Before: 22.64 mmol/L; during: 25.14 mmol/L; after: 22.61 mmol/L | n.r |

| Katheria A.C., 2017 [72] | Retrospective study | Preterm neonates | 36 | FORE-SIGHT | Day 1 after birth | Before and 1 h within HCO3 administration | Continuously in 10 min periods before, during, and after HCO3 administration | n.r. | n.r. | Yes Positive |

| Loomba R.S., 2022 [80] | Retrospective single-center study | n.r. | 23 | FORE-SIGHT | Months 15.4 ± 30.8 | Baseline, 1 h after HCO3 administration, and 2 h after HCO3 administration | Baseline, 1 h after HCO3 administration, and 2 h after HCO3 administration | Baseline: 64%; 1 h after HCO3 administration: 65% 2 h after HCO3 administration: 65% | Baseline: 18 mEq/L; 1 h after HCO3 administration: 21 mEq/L; 2 h after HCO3 administration: 20 mEq/L | No |

| Savorgnan F., 2023 [82] | Single-center, retrospective analysis | Term neonates | 134 | n.r. | Day 7 (4–10) after birth | Baseline and within 6 h before extubation | At baseline, 10 min after extubation, and 120–180 min post-extubation | At baseline: 57.9%; 10 min after extubation: −1.7% × min; 120–180 min post-extubation: −0.4% × min | At baseline: 27 mEq/L; within 6 h before extubation: 27.0 mEq/L | n.r. |

| Mattersberger C., 2023 [34] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 157 | INVOS 5100 | During and immediately after the delivery | Between 10 to 20 min after birth | Continuously at 15th minute after birth | Preterm neonates 82% and term neonates 83%; preterm neonates 0.13 and term neonates 0.14 | Preterm neonates: 21.0 mmol/L; term neonates: 21.6 mmol/L | No in preterm neonates; yes in term neonates; FTOE positive |

| Dusleag M. 2024 [85] | Prospective observational study | Preterm and term neonates | 77 | INVOS 5100 | During the first 15 min after birth | Immediately after birth | During the first 15 min after birth | Preterm neonates: 44%; term neonates: 62.2% | Preterm neonates: 22.9 mmol/L; term neonates: 23.0 mmol/L | No |

| Author | Bias Due to Confounding | Bias Arising from Measurement of the Exposure | Bias in Selection of Participants into the Study | Bias Due to Post-Exposure Interventions | Bias Due to Missing Data | Bias Arising from Measurement of the Outcome | Bias in Selection of the Reported Result | Overall Risk of Bias Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldrich C.J., 1994 [38] | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | low risk | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | very high risk of bias |

| von Siebenthal K., 2005 [43] | low risk | low risk | some concerns | some concerns | some concerns | low risk | some concerns | some concerns |

| Weiss M., 2005 [44] | some concerns | low risk | low risk | some concerns | low risk | low risk | some concerns | some concerns |

| van Alfen-van der Velden A.A.E.M., 2006 [46] | low risk | low risk | low risk | some concerns | low risk | low risk | some concerns | some concerns |

| Amigoni A., 2011 [26] | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | some concerns | some concerns | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias |

| Menke J., 2014 [57] | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | some concerns | low risk | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias |

| Mintzer J.P., 2015 [63] | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | very high risk of bias |

| Mebius M.J., 2016 [64] | high risk of bias | low risk | high risk of bias | low risk | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | very high risk of bias |

| Hunter C.L., 2017 [68] | low risk | low risk | low risk | some concerns | low risk | low risk | some concerns | some concerns |

| Nissen M., 2017 [69] | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | very high risk of bias |

| Katheria A.C., 2017 [72] | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | some concerns | low risk | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias |

| Janaillac M., 2018 [74] | low risk | low risk | some concerns | some concerns | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias |

| Mebius M.J., 2018 [75] | some concerns | low risk | some concerns | some concerns | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias |

| Leroy L., 2021 [79] | low risk | low risk | low risk | low risk | low risk | low risk | some concerns | some concerns |

| Loomba R.S., 2022 [80] | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | very high risk of bias |

| Mattersberger C., 2023 [34] | low risk | low risk | low risk | low risk | high risk of bias | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias |

| Kazanasmaz H., 2023 [83] | some concerns | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias | low risk | low risk | some concerns | high risk of bias |

| Dusleag M. 2024 [85] | low risk | low risk | low risk | low risk | high risk of bias | high risk of bias | some concerns | very high risk of bias |

| ROBINS-E | Correlation Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| crSO2 or FTOE | |||||||

| Author | Overall Risk-of-Bias Rating | pH | BE or BD | HCO3 | |||

| Aldrich C.J., 1994 [38] | very high risk of bias | yes | + | yes | - | ||

| von Siebenthal K., 2005 [43] | some concerns | no | |||||

| Weiss M., 2005 [44] | some concerns | no | no | ||||

| van Alfen-van der Velden A.A.E.M., 2006 [46] | some concerns | no | no | no | |||

| Amigoni A., 2011 [26] | high risk of bias | yes | - | ||||

| Menke J., 2014 [57] | high risk of bias | no | |||||

| Mintzer J.P., 2015 [63] | very high risk of bias | no | no | no | |||

| Mebius M.J., 2016 [64] | very high risk of bias | no | |||||

| Hunter C.L., 2017 [68] | some concerns | no | no | no | |||

| Nissen M., 2017 [69] | very high risk of bias | yes | - | yes | - | yes | - |

| Katheria A.C., 2017 [72] | high risk of bias | yes | + | yes | - | yes | + |

| Janaillac M., 2018 [74] | high risk of bias | no | |||||

| Mebius M.J., 2018 [75] | high risk of bias | no | |||||

| Leroy L., 2021 [79] | some concerns | yes | - | yes | - | ||

| Loomba R.S., 2022 [80] | very high risk of bias | no | no | ||||

| Mattersberger C., 2023 [34] | high risk of bias | yes | + | yes | + | yes | |

| Kazanasmaz H., 2023 [83] | high risk of bias | yes | + | no | |||

| Dusleag M. 2024 [85] | very high risk of bias | no | no | no | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mattersberger, C.; Schwaberger, B.; Baik-Schneditz, N.; Pichler, G. Acid–Base Status and Cerebral Oxygenation in Neonates: A Systematic Qualitative Review of the Literature. Children 2025, 12, 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111549

Mattersberger C, Schwaberger B, Baik-Schneditz N, Pichler G. Acid–Base Status and Cerebral Oxygenation in Neonates: A Systematic Qualitative Review of the Literature. Children. 2025; 12(11):1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111549

Chicago/Turabian StyleMattersberger, Christian, Bernhard Schwaberger, Nariae Baik-Schneditz, and Gerhard Pichler. 2025. "Acid–Base Status and Cerebral Oxygenation in Neonates: A Systematic Qualitative Review of the Literature" Children 12, no. 11: 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111549

APA StyleMattersberger, C., Schwaberger, B., Baik-Schneditz, N., & Pichler, G. (2025). Acid–Base Status and Cerebral Oxygenation in Neonates: A Systematic Qualitative Review of the Literature. Children, 12(11), 1549. https://doi.org/10.3390/children12111549