Abstract

Background/Objectives: Human colostrum plays a crucial role in early microbial colonization, immune development, and gut health of newborns. Its microbiota is highly dynamic and influenced by numerous factors, yet the determinants remain poorly understood. This systematic review aims to investigate the composition of colostrum microbiota and the intrinsic and extrinsic factors that influence its diversity and abundance. Methods: PubMed and Scopus were systematically searched using a prespecified search phrase. Data on microbial composition, diversity, and influencing factors were extracted and analyzed. The systematic review is registered in PROSPERO (CRD42025644017). Results: A total of 44 eligible studies involving 1982 colostrum samples were identified. Colostrum microbiota consists predominantly of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, with core genera including Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, and Bifidobacterium. Some studies reported higher diversity in colostrum compared to mature milk, while others noted elevated bacterial abundance in the former. Factors influencing colostrum microbiota include maternal BMI, delivery mode, gestational age, diet, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), maternal stress, maternal age, secretor status, perinatal antibiotic exposure, neonatal gender, geographic location, feeding type, milk collection method, and mastitis. Conclusions: Colostrum hosts a diverse and dynamic microbiota shaped by multiple maternal, neonatal, and environmental factors. Understanding these influences is crucial for optimizing infant health outcomes, emphasizing the need for further research on the functional roles of colostrum’s microbiota.

1. Introduction

Human milk is widely recognized as the optimal source of nutrition for infants, providing a dynamic blend of nutritional and bioactive components tailored to meet the needs of newborns. Its composition is not static, and it changes by various factors such as the stage of lactation, maternal health, and environmental influences [1,2,3]. Human colostrum is uniquely adapted to satisfy the early immunological and nutritional requirements of neonates. Compared to mature milk, colostrum contains higher concentrations of immunoglobulins, growth factors, cytokines, immune cells, and other bioactive compounds that confer immune protection, support gut health, and offer immediate defense against infections [1,2,3,4,5,6].

Breastfeeding offers a well-known range of significant short- and long-term health benefits for infants. It protects against infections, reduces the risk of necrotizing enterocolitis, and minimizes allergic conditions [7,8,9,10,11]. Breastfed infants may also have a lower likelihood of obesity later in life and reduced risk of metabolic syndrome in adulthood. In addition, studies suggest that breastfed children often perform better on intelligence tests, suggesting cognitive benefits associated with breastfeeding [12,13].

Colostrum, provided through early breastfeeding, provides even more distinct and immediate health benefits, particularly for populations such as preterm or low-birth-weight infants that face many challenges postpartum. Early breastfeeding reduces neonatal mortality, lowers the incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis, offers protection against late-onset sepsis, leads to faster achievement of full enteral feeding, and quicker recovery to birth weight, parameters that are crucial for the survival and health optimization of susceptible infants [14,15,16].

Growing research data suggests that breast milk hosts its own unique microbiota, which may play a crucial role in promoting health benefits both for mothers by supporting mammary gland health and infants by aiding gut colonization, thus providing defense against pathogens, fostering immune system development, and assisting in nutrient digestion [17].

The initial microbial colonization of infants is accelerated rapidly after birth, primarily derived from the maternal microbiota, which serves as the infant’s main microbial source [18]. Maternal breast milk, especially colostrum, plays a significant role in this process, as it introduces beneficial microbes that contribute to infant gut colonization and supports infant but also maternal health [19]. Differences in gut microbiota between breastfed and formula-fed infants underscore the importance of this microbial transfer. Studies show that exclusively breastfed infants exhibit gut microbiota with lower diversity, yet higher relative abundance of beneficial bacteria, when compared to formula-fed infants [20,21].

The composition of an infant’s intestinal microbiota is essential for immune system development and is linked to various long-term health outcomes. A disrupted or imbalanced microbiota in infancy is associated with increased risk of allergic conditions, chronic inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, type 1 Diabetes, and reduced vaccine efficacy [20,22,23,24,25,26].

Despite the recognized role of breast milk microbiota in early-life health, limited information exists on the composition and variability of microbiota, especially for colostrum, and even less is understood about the factors influencing it. This systematic review aims to summarize current evidence on the microbiota of human colostrum, examining its composition, diversity, and potential roles in neonatal gut colonization and immune development. It also seeks to identify intrinsic (e.g., maternal health, mode of delivery) and extrinsic (e.g., environment, diet, antibiotics) factors that influence colostrum microbiota, and to highlight gaps in knowledge to guide future research on early-life microbial transfer.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review is in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [27]. A prespecified protocol was formulated and registered in PROSPERO (CRD42025644017) and is available online. Full protocol details can be found in the Data Supplement.

2.1. Search Strategy

Two authors (AT and NAX) independently conducted the literature search. Any discrepancy was solved by discussion between them. PubMed and Scopus were systematically searched along with the references of retrieved articles. A search phrase was formulated using Boolean logic and a combination of terms related to human milk and its microbial content. The main keywords included the following: “human milk,” “breast milk,” “colostrum,” “microbiota,” “microbiome,” “microflora,” and “flora”. “Human milk,” “breast milk,” and “colostrum” represent different stages and terminologies of lactation, while “microbiota,” “microbiome,” “microflora,” and “flora” encompass various terms used in the literature to describe microbial communities. All relevant literature in English up until 17 June 2025 was retrieved with no time restrictions. We considered for inclusion studies providing collective data on colostrum microbiota, which was defined as the milk produced during the first 5 days postpartum. Studies were excluded if they (i) studied pasteurized milk; (ii) did not clearly specify the type of milk analyzed; or (iii) involved milk collected after five days postpartum. Additionally, reference lists of selected articles were reviewed to identify other potentially relevant studies. All observational studies (cohort studies, cross-sectional studies, case–control studies, case series, case reports) and clinical trials referring to colostrum’s microbiota will be included. Review articles, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, as well as conference proceedings, will be excluded.

2.2. Data Extraction

A prespecified table including data on the name of the first author, publication year, country of research, participant characteristics (e.g., maternal age, prior antibiotic use, probiotic supplementation, gestational age, mode of delivery, feeding method), milk sample size, timing and method of milk collection, microbiota analysis techniques, and key findings related to microbial diversity, abundance, and associations with influencing factors was utilized. Data extraction and quality assessment were performed independently by two authors (AT, EK). Any disagreements between the initial reviewers were resolved through discussion; if a consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer was involved to achieve resolution (NAX).

2.3. Outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest were the following: (1) the identification and characterization of colostrum microbiota, with particular attention to dominant genera and species reported across studies, and (2) the factors influencing colostrum colonization, including maternal characteristics (e.g., health status, antibiotic use), mode of delivery, gestational age, and environmental or hospital-related exposures.

3. Results

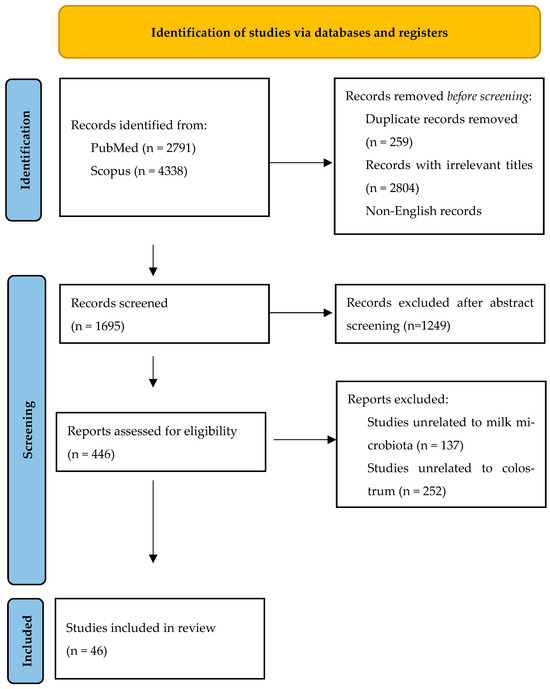

A total of 7129 articles were initially retrieved, 2791 of which were from PubMed and 4338 from Scopus. After eliminating 2597 duplicates, 2804 records with irrelevant titles, and 33 non-English records, 1698 articles remained for abstract screening. Of these, 446 studies were sought for retrieval, and 41 studies were included in the final analysis. Additionally, 5 relevant studies were identified through manual reference searching, bringing the total number of studies included in this review to 46, as depicted in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

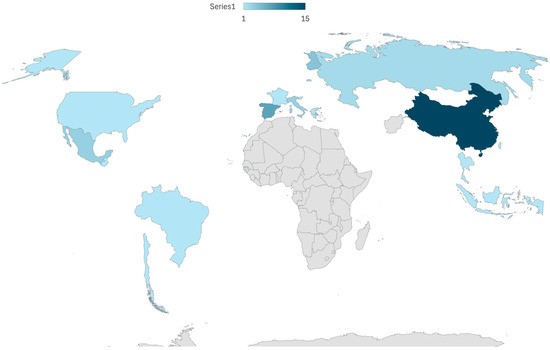

The 46 studies investigated colostrum samples from 2352 mothers (Table 1) [17,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71]. The studies were conducted across 17 countries, with the majority (18) taking place in a single country, and one study conducted in two countries. The countries represented include China (15 studies), Spain (7 studies), Finland (4 studies), Mexico (3 studies), Russia (2 studies), Italy (3 studies), and one study each in Guatemala, Brazil, Burundi, Chile, France, Gambia, Greece, Indonesia, Slovenia, Taiwan, Thailand, Switzerland, and the USA. A comprehensive map of the represented countries is presented below (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Study Characteristics.

Figure 2.

Map of the represented countries.

Among the 46 studies, 5 studies specifically targeted lactic acid bacteria [36,39,51,53,72], one study examined bacteria typically found in the mother’s gut [55], one study analyzed the presence of fungi [29], and one study investigated methanogenic archaea [17]. A variety of methodologies were employed to analyze the microbiota, including bacterial culture (1 study), polymerase chain reaction (PCR) (5 studies), matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) (3 studies), 16S rRNA gene sequencing (15 studies), and metagenomic shotgun sequencing (1 study). Eleven (11) studies used two methods, and four studies employed three different methods for microbiota analysis.

Regarding the DNA extraction methods, 15 different DNA extraction kits were utilized. The sequencing was performed using seven different sequencing machines, including Genome Sequencer FLX, Ion Torrent PGM, Illumina MiSeq, Illumina HiSeq 2500, Illumina NovaSeq 6000, Illumina HiSeq 3000, and the PacBio Sequel sequencer. These studies targeted five different hypervariable regions (V1–V3, V3, V3–V4, V4, V3–V5) and used nine different databases for taxonomic classification, including Ribosomal Database Project (RDP), Greengenes, Silva, NCBI BLAST, Kraken2, RefSeq, Myla Database (BioMérieux), GenBank, and MicroSEQ ID.

Information on study design and results regarding each of the included studies can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Results of the included studies.

3.1. General Composition

3.1.1. Bacteria

The bacterial diversity in colostrum varied across studies, with up to 465 genera, 645 species, and 7900 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) detected [57,71]. The number of OTUs identified per colostrum sample ranged from 122 to 341 [55,57]. Bacterial loads reported by culture-based methods ranged from 3.7 × 102 to 1.1 × 109 genome equivalents (GE) per mL [54,70], while qPCR methods detected bacterial loads between 104 and 106 CFU/mL [28,29].

Regarding bacterial abundance and diversity, Khodayar-Pardo et al. reported that colostrum has the lowest total bacterial count, with a progressive increase in total bacteria and specific groups like Bifidobacterium and Enterococcus spp. across lactation, leading to a more enriched microbial profile in mature milk [48]. Similarly, Boix-Amorós et al. observed lower diversity in colostrum and a peak in bacterial diversity during transition milk, though they noted a greater abundance of Acinetobacter in colostrum, while Staphylococcus remained dominant across all lactation stages [29]. Conversely, other studies highlighted higher bacterial abundance in colostrum. Cabrera-Rubio et al. reported that colostrum exhibits higher diversity compared to 1-month and 6-month milk samples, suggesting a decline in bacterial diversity as milk matures [32]. Collado et al. reported higher counts of Enterococcus in colostrum, whereas mature milk showed increased abundance of Staphylococcus aureus and Clostridium coccoides, indicating a shift in microbial composition over time [34]. Similarly, Xie et al. emphasized the greater heterogeneity and a notable presence of environmental bacteria in colostrum, suggesting elevated microbial abundance during this early stage of lactation [71]. In line with this, Liu et al. reported that microbial diversity increases as milk progresses from colostrum to mature milk, with Firmicutes and Proteobacteria as the dominant phyla and core genera such as Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Serratia, and Corynebacterium, highlighting the dynamic nature of microbial composition across lactation [50]. Additionally, Qi et al. observed that colostrum exhibits a higher abundance of specific genera such as Bifidobacterium, Fusicatenibacter, and Blautia, which decrease as lactation progresses, while genera like Staphylococcus remain prominent throughout all stages [55].

The predominant phyla in colostrum were Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, while Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes were less abundant [49,57,61,66,67]. Additional phyla identified included Acidobacteria, Armatimonadetes, Chlamydiae, and Verrucomicrobia [28,29,31,57]. Core genera consistently identified across studies included Bifidobacterium spp., Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus, with Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium breve detected in nearly all samples [28]. Other genera commonly found in colostrum included Staphylococcus, Acinetobacter, Pseudomonas, Lactobacillus, and Clostridium clusters XIVa-XIVb [29,31]. Wyatt et al. reported high prevalence of Streptococcus and Micrococci, while Tang et al. and Obermajer et al. observed the presence of Enterobacteriaceae, including Acinetobacter and Stenotrophomonas [54,60,70].

Several studies showed that colostrum contains higher bacterial diversity compared to both maternal and infant feces. Cabrera-Rubio et al. reported that colostrum harbored greater diversity than both infant and maternal feces [31]. Singh et al. noted that colostrum contained a higher number of amplicon sequence variants (ASVs) than infant feces, while Qi et al. highlighted significant bacterial transfer from colostrum to infant feces [55,57]. Xie et al. also confirmed differences in microbiota composition between colostrum and infant feces [71].

3.1.2. Probiotic Bacteria

Damaceno et al. reported the presence of Lactobacillus gasseri and Bifidobacterium breve in colostrum samples, with higher prevalence in vaginal deliveries and mothers with normal BMI [36]. Dubos et al. reported that 55.3% of colostrum samples were positive for Lactobacillus, with Lactobacillus plantarum being the most abundant species (64% of isolates), followed by Lactobacillus fermentum (16%) [42]. Martin et al. identified Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus fermentum in breast milk isolates from mother–infant pairs, as well as Enterococcus faecium in both breast milk and infant feces [19]. Nikolopoulou et al. detected Bifidobacterium in 61.5% of colostrum samples, with Bifidobacterium longum and Bifidobacterium bifidum as the most prevalent species [53]. Lactobacillus was found in 46.2% of samples, with both Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus detected in 76.9% of colostrum samples.

3.1.3. Microbes Other than Bacteria

Boix-Amorós et al. reported a median fungal load in colostrum of 4.1 × 105 cells/mL, with similar levels observed in transitional milk (4.5 × 105 cells/mL) and lower levels in mature milk (2.8 × 105 cells/mL). Fungal DNA was detected in 16 of the 18 colostrum samples, with dominant fungal genera including Malassezia, Candida, and Saccharomyces. Malassezia was found in all colostrum samples where fungi were detected but was not isolated in culture [30].

Togo et al. analyzed 20 samples from 13 mothers for methanogenic archaea, with positive cultures in 9 out of 20 samples (3 colostrum and 6 milk samples). M. smithii was isolated in eight samples from five mothers, while M. oralis was isolated in one milk sample. Real-time PCR detection in 136 samples revealed M. smithii in 27.3% of colostrum samples (32/117) and 26.3% of milk samples (5/19), with a median DNA concentration of 463 copies/mL in colostrum [17].

3.2. Factors That Influence Breast Milk Microbiota

3.2.1. Diet

Dietary factors can influence the composition of colostrum microbiota, and studies focus on the effects of macronutrients, micronutrients, and specific dietary patterns. Drago et al. found differences in the microbial hubs of colostrum between Italian and Burundian mothers, likely due to dietary differences between them. The Italian diet, rich in animal proteins, fats, and sugars, was associated with bacterial hubs like Abiotrophia spp. and Parabacteroides spp., while the Burundian plant-based diet resulted in bacterial hubs such as Aquabacterium spp. and Rhizobium spp., reflecting the influence of fiber-rich foods on the microbiome [40].

Nikolopoulou et al. reported that women who consumed yogurt regularly had a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in their colostrum, suggesting that probiotic intake through diet could contribute to these bacterial populations [53]. Williams et al. observed that maternal intake of saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids was negatively associated with Corynebacterium, while carbohydrate intake (lactose and disaccharides) was negatively associated with Firmicutes in colostrum [68]. Additionally, micronutrients such as pantothenic acid, riboflavin, and calcium were associated with Veillonella and Streptococcus, highlighting the impact of micronutrient intake on microbiota composition.

Tapia Gonzalez et al. [62] reported that non-nutritive sweeteners (NNS) did not significantly affect the diversity of colostrum microbiota, although some shifts were observed in specific genera, such as an increase in Bifidobacterium and a decrease in Staphylococcus and Blautia with higher NNS consumption. Tang et al. [60] noted that Hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), a persistent organic pollutant commonly found in fish, was associated with changes in microbial diversity, with Pseudomonas and Enterococcus showing notable alterations in colostrum from high HCH exposure groups.

3.2.2. Maternal Body Mass Index

Maternal BMI influences the microbiota composition in colostrum. Cabrera-Rubio et al. and Collado et al. observed higher bacterial counts of Lactobacillus and Staphylococcus in colostrum from overweight or obese mothers compared to that from mothers with normal BMI [31,34]. Cabrera-Rubio et al. further reported a reduction in bacterial diversity in colostrum from obese mothers, which diminished in later lactation stages [31]. Similarly, Dave et al. found that a higher maternal pre-pregnancy BMI correlated with a lower relative abundance of Streptococcus but higher overall microbial diversity in breast milk [37].

Studies showed that Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus detection in colostrum decreases with increasing maternal BMI. Nikolopoulou et al. reported that Lactobacillus positivity dropped significantly in mothers with higher BMI [53]. Additionally, Togo et al. reported that the prevalence of M. smithii was lower in obese mothers compared to lean or overweight mothers [17].

3.2.3. Delivery Mode

Delivery mode influences the microbial composition of colostrum, and several studies highlight differences between vaginal and cesarean delivery in terms of bacterial diversity and composition. Cabrera-Rubio et al. and Khodayar-Pardo et al. reported that colostrum from cesarean deliveries had higher total bacterial concentrations and altered bacterial composition compared to vaginal deliveries, with an increased abundance of certain families such as Carnobacteriaceae and Streptococcus spp., while Bifidobacterium spp. was more frequently detected in vaginal deliveries [31,48].

Toscano et al. noted that colostrum from vaginal delivery had slightly higher biodiversity, with significantly higher levels of Streptococcus and Haemophilus, whereas cesarean delivery colostrum showed increased levels of Finegoldia, Halomonas, Prevotella, Pseudomonas, and Staphylococcus [63]. Additionally, Mastromarino et al. found that vaginal delivery was associated with significantly higher levels of Lactobacilli and Bifidobacteria in colostrum, whereas cesarean delivery showed no such increase [51].

In terms of microbial networks, Toscano et al. identified distinct bacterial hubs for both delivery modes, with Ruminococcus and Peptostreptococcus being key nodes in cesarean colostrum, while Rhodanobacter and Achromobacter were central in vaginal delivery colostrum [63]. Similarly, Xie et al. reported that cesarean delivery colostrum exhibited higher diversity compared to vaginal delivery, with distinct microbial profiles identified through principal component analysis (PCA) [71].

3.2.4. Gestational Age

Gestational age influences the microbiota composition of breast milk, with notable differences between preterm and term samples. Du et al. reported that gestational age did not significantly affect alpha or beta diversity in breast milk [41]. However, Khodayar-Pardo et al. observed that Bifidobacterium spp. levels were higher in milk from full-term infants across all stages of lactation, with significant differences noted in colostrum, transitional milk, and mature milk (p = 0.003, p = 0.005, p = 0.014), while Enterococcus spp. levels were lower in term milk, particularly colostrum (p = 0.045) [48].

Moles et al. reported higher bacterial counts in mature milk compared to colostrum for extremely preterm infants, with significantly higher frequencies of Enterococci (p = 0.000), Lactobacilli (p = 0.041), and Enterobacteria (p = 0.038) in mature milk [52]. Additionally, Singh et al. found that preterm breast milk had higher microbial richness and diversity compared to term milk, with significant differences in the Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes phyla. Genera such as Faecalibacterium, Prevotella, Clostridium, Bacteroides, and Enterobacter were more abundant in preterm samples, whereas term milk showed higher levels of OD1 phyla and enrichment in Staphylococcus epidermidis, unclassified Veillonella, and unclassified OD1 species [57].

3.2.5. Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs)

HMOs in colostrum influence microbial composition. Aakko et al. reported a positive correlation between total HMO concentration and the presence of Bifidobacterium spp. (ρ = 0.63, p = 0.036), and sialylated HMOs strongly correlated with Bifidobacterium breve (ρ = 0.84, p = 0.001) while fucosylated HMOs correlated with Akkermansiamuciniphila (ρ = 0.70, p = 0.017). Sun et al. observed significant correlations between specific HMOs and bacterial taxa: Lactobacillus was positively correlated with LNT (r = 0.250, p = 0.037), while Staphylococcus was negatively correlated with DS-LNT (r = −0.240, p = 0.045). Streptococcus in colostrum showed positive correlations with LNFP II, LNFP III, and 3-SL (p < 0.05), suggesting that HMOs modulate the presence of specific bacterial taxa [59,73]. Additionally, differences in HMO profiles were observed based on maternal characteristics: non-fucosylated HMOs were lower in milk from mothers who delivered vaginally compared to cesarean deliveries (p = 0.038), while fucosylated HMOs were higher in primipara compared to multipara mothers (p = 0.030). Cabrera-Rubio et al. further highlighted that the presence of certain HMOs, such as 2′FL, was associated with higher levels of Lactobacillus in secretor colostrum, while Ge et al. reported that Staphylococcus and Gemella were negatively correlated with several HMOs in colostrum, including 3′-SL, LNT2, LSTc, and total HMOs. In contrast, Serratia, Pseudomonas, and Stenotrophomonas showed significant positive correlations with multiple HMOs, especially LNT2 and total HMOs [32,45].

3.2.6. Maternal Secretor Status

Maternal secretor status influences the microbiota composition in colostrum. Cabrera-Rubio et al. found that colostrum from secretor mothers had significantly higher levels of Lactobacillus spp. (p = 0.0004), Streptococcus spp. (p = 0.0030), and Enterococcus spp. (p = 0.014) compared to non-secretors. However, Bifidobacterium spp. levels were lower in secretor colostrum (p = 0.040). Secretor colostrum also had higher concentrations of 2′-fucosyllactose (2′FL) and lacto-N-fucopentaose I (LNFP I), while non-secretor colostrum contained higher levels of LNFP II and lacto-N-difucohexaose II (LNDFH II). Additionally, a positive association between higher Lactobacillus levels and 2′FL was observed (Spearman’s rho = 0.542, p = 0.038) [32].

3.2.7. Maternal Age

Maternal age influences the microbiota composition in human milk, though the effects are not always consistent across studies. Corona-Cervantes et al. reported a slight tendency for a decrease in milk richness (Chao1) with increasing maternal age, while diversity (Shannon) tended to increase with the number of days postpartum [35]. Nikolopoulou et al. observed a decline in the presence of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in milk samples as maternal age increased, with 100% of women aged 18–29 having positive samples, compared to only 26.1% in women aged 35–39 and 0% in women aged 45 and older [53]. However, Wan et al. found no statistically significant differences in microbial diversity or richness between mothers aged ≤ 30 and >30 (p = 0.35 for diversity and p = 0.79 for richness) [65].

3.2.8. Macronutrients of Colostrum and Fungi

Boix-Amorós et al. found significant correlations between fungal load and milk components, suggesting that certain macronutrients might influence fungal populations in breast milk. Fungal load was positively correlated with fat content and non-fatty solids (NFS), indicating that both fat and specific non-fatty nutrients may support fungal presence. Specific fungal genera also showed associations with milk components: Malassezia displayed a strong positive correlation with bacterial load (Spearman’s ρ = 0.93, p = 0.007) and lactose content (ρ = 0.78, p = 0.048), while Candida was positively correlated with protein content (ρ = 0.77, p = 0.044), suggesting that protein may specifically support this genus. In contrast, Lodderomyces exhibited a negative correlation with human somatic cells (ρ = −0.79, p = 0.035), indicating an inverse relationship between immune cell concentrations and fungal presence [30].

IL-6

Collado et al. reported that higher IL-6 levels correlated with higher Staphylococcus counts in normal-weight mothers (r = 0.628, p = 0.039). However, in overweight mothers, higher IL-6 levels were associated with lower Akkermansiamuciniphila counts (r = −0.738, p = 0.015), suggesting that IL-6 may play a role in modulating the microbiota composition of colostrum, with distinct effects depending on maternal weight status [34].

3.2.9. Probiotics During Pregnancy

Two studies (70 and 66 participants) investigated the effects of probiotic supplementation during pregnancy on the microbiota in colostrum. Dewanto et al. reported that Bifidobacterium animalis lactis HNO19 (DR10) was detected in 14% of mothers in the probiotic group at birth, increasing to 20% at 3 months postpartum, while the placebo group showed no detectable DR10. However, no significant differences were found in total microbiota or in Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium levels between the groups at either time point [39]. In contrast, Mastromarino et al. observed that the probiotic-supplemented group had significantly higher counts of Lactobacilli (4.5 × 103 cells/mL) and Bifidobacteria (1.7 × 104 cells/mL) in colostrum compared to the placebo group [51].

3.2.10. Geographic Location

Geographic location also influences the composition of colostrum microbiota, with differences noted in bacterial diversity and specific bacterial hubs between regions. Nikolopoulou et al. found a higher prevalence of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium in colostrum from rural areas compared to urban areas, with 97.1% of rural samples testing positive vs. 33.8% in urban samples [53]. Similarly, Wan et al. reported significant differences in microbial diversity and richness across cities, with genus-level variations in colostrum microbial composition [65]. In terms of bacterial hubs, Drago et al. identified Aciditerrimonas spp. as the central node in Italian colostrum, while Aquabacterium spp. was the central node in Burundian colostrum, reflecting differences driven by environmental exposure and dietary influences [40].

3.2.11. Perinatal Antibiotic Exposure

Perinatal antibiotic exposure has varying effects on breast milk microbiota composition. Du et al. and Ji et al. reported no significant impact on microbial diversity or composition in breast milk following intrapartum or post-delivery antibiotic treatment (Cefuroxime (CXM), Ceftriaxone (CFX)) [41,46]. However, specific shifts were observed; for instance, Du et al. noted enrichment of Lachnospiraceae in the milk of mothers who received Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis (IAP), while Ji et al. found Pseudomonas and Clostridiaceae to be more abundant in certain antibiotic-treated groups. In contrast, Wang et al. observed significant changes in colostrum microbiota after post-delivery antibiotic treatment, with decreased alpha diversity and reductions in genera like Actinomyces and Clostridium [66]. Singh et al. reported no significant changes in colostrum microbiota associated with antibiotic use during delivery [57].

3.2.12. Gender of the Neonate

The gender of the neonate influences the composition of breast milk microbiota in some studies. Du et al. reported no significant differences in alpha and beta diversity based on infant gender; however, specific genera varied, with Streptococcaceae enriched in the milk of mothers with female infants, while Roseburia and Alcaligenaceae were more abundant in the milk of mothers with male infants [41]. Similarly, Gamez-Valdez et al. observed gender-related differences in microbial composition in the context of obesity and gestational diabetes. Higher levels of Gemella and Staphylococcus were detected in the obesity-female group, while Prevotella and Rhodobacteraceae were enriched in the GDM-female subgroup [44]. Additionally, Williams et al. found that milk from mothers of male infants had higher levels of Streptococcus and lower levels of Staphylococcus compared to milk from mothers of female infants [68].

3.2.13. Maternal Stress

In two studies, maternal stress was found to affect the composition of human milk microbiota [38,43]. Fernández-Tuñas et al. reported that milk from low-stress mothers had higher microbial diversity (Shannon index of 1.19) compared to milk from high-stress mothers (0.99). In high-stress mothers, Proteobacteria increased from 12.5% on day 3 to 44.4% on day 15, while Firmicutes decreased from 87.5% to 55.6%. In contrast, for low-stress mothers, Firmicutes remained dominant with a slight increase in Proteobacteria. Other phyla, such as Actinobacteria and Bacteroidetes, were rarely detected [43]. Respectively, Deflorin et al. reported that prenatal generalized anxiety and postpartum anxiety both negatively correlated with the colostrum microbiome, although there was no association between maternal mental health scores and alpha or beta diversity (false discovery rate (FDR) > 0.05) [38].

3.2.14. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM)

Gámez-Valdez et al. reported that Staphylococcus was more abundant in GDM mothers, with levels higher in both the GDM-female group (15.6%) and the GDM-male group (21.9%) compared to controls. Prevotella was also more abundant in GDM mothers (6.1% in GD-F and 6.8% in GD-M) than in healthy controls (4.8%), with higher levels in females. Both Corynebacterium and Anaerococcus were significantly enriched in GDM colostrum compared to controls. GDM colostrum exhibited higher alpha diversity than controls, with GDM-females showing greater diversity than GDM-males. Distinct taxonomic differences were also noted, including increased Burkholderia in the obesity-female group and Rhodobacteraceae and Xanthobacteraceae in the GDM-female group [44].

3.2.15. Feeding Type

Feeding type influences the relationship between maternal milk and infant gut microbiota, based on Li et al. who found that in the breastfeeding (BF) group, there were more consistent and specific correlations between maternal milk and infant gut microbiota. In contrast, the mixed feeding (MF) group displayed a greater variety of species correlated between breast milk and the infant’s gut, indicating that mixed feeding introduces additional variability to microbiota. This suggests that breastfeeding may support a more stable microbial environment, while mixed feeding introduces greater diversity [49].

3.2.16. Milk Collection Methods

The way of milk collection influences the bacterial load and composition of breast milk microbiota. Sakwinska et al. compared two collection protocols: a standard protocol and an aseptic protocol. The standard protocol showed a significantly higher total bacterial load compared to the aseptic protocol, with a median of 7.5 × 104 counts/mL vs. 7.8 × 103 counts/mL at 5–11 days postpartum (p < 0.0001). However, this difference was not significant at earlier or later time points. Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli were detected in very few samples, with slightly higher proportions in the aseptic protocol. Performing 16S rRNA gene sequencing revealed more bacterial DNA in standard protocol samples, with Staphylococcus and Streptococcus making up 42% and 40% of the microbiota, respectively, in both protocols. In contrast, aseptic samples showed a significantly lower abundance of Acinetobacter (1.8%) compared to standard protocol samples (32%). Multivariate analysis confirmed significant differences in microbiota composition between the two collection methods, underscoring the impact of collection protocol on the milk microbiota profile [56].

3.2.17. Mastitis

Tao et al. compared colostrum from healthy women and women with mastitis, highlighting key differences. In healthy women, colostrum had significantly higher levels of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium compared to Staphylococcus and Streptococcus (p < 0.0001). In mastitis milk (from both affected and unaffected breasts), these beneficial bacteria were significantly lower. In mastitis cases caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S.A.) or Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Staphylococcus levels in colostrum were lower than in the affected breast but similar to the unaffected breast. However, in Staphylococcus epidermidis (S.E.) or Staphylococcus lentus (S.L.)-mediated mastitis, Staphylococcus levels in colostrum were similar to or higher than in mastitis milk. Bifidobacterium levels remained higher in colostrum than in both affected and unaffected breasts of Staphylococcus-related mastitis patients (p < 0.01). In non-bacterial mastitis cases, colostrum showed significantly higher bacterial levels compared to mastitis milk (p < 0.01). Cytokine analysis revealed significantly higher levels of IL-6 and IL-8 in mastitis milk compared to colostrum, while CRP, TNF-α, and IL-1 levels showed no significant differences between the two groups [61].

3.2.18. HPV Infection

HPV infection was detected in both breast milk and infant oral samples, and Tuominen et al. reported that 8.6% of mothers’ breast milk samples tested positive for HPV DNA, compared to 40% of infant oral samples. The bacterial composition in colostrum revealed that Firmicutes (79.7%), Proteobacteria (14.1%), Actinobacteria (5.2%), and Bacteroides (0.5%) were the predominant phyla. Notably, Proteobacteria was significantly more abundant in breast milk compared to the infant oral cavity (4.5%, p = 0.0082), while Bacteroides was more abundant in the infant oral cavity (6.0%, p = 0.009). The shared core microbiota between breast milk and the infant oral cavity included genera such as Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Rothia, and Veillonella [64].

Although no significant differences in species richness, diversity, or microbial composition were found between HPV-positive and HPV-negative breast milk samples, breast milk showed higher microbial diversity, compared to the infant oral cavity (p = 0.0043, Shannon index), and distinct clustering patterns (p = 0.0001, RDA). Additionally, HPV-positive infant oral samples exhibited a distinct clustering pattern compared to HPV-negative samples (p = 0.036, RDA). Levels of Veillonella dispar were significantly higher in HPV-negative infant oral samples at both the genus (p = 0.025) and species (p = 0.048) levels [64].

3.2.19. Gestational Hypertension

Gestational affects the microbial composition in breast milk, particularly in mothers with gestational prehypertension. Wan et al. observed that mothers with gestational hypertension had lower microbial diversity and richness in their colostrum compared to normotensive mothers, with significant differences (p < 0.05). Additionally, Lactobacillus abundance in colostrum was lower in prehypertensive mothers, with a trend towards significance in colostrum (p = 0.09) and a significant decrease in transitional milk (p = 0.004) [65].

3.2.20. Ethnicity

Ethnicity influences the microbial composition of breast milk. Xie et al. compared colostrum microbiota between Li and Han ethnic groups, noting significant differences at both phylum and genus levels. In the Li ethnic group, Proteobacteria (66.5%) was the dominant phylum, followed by Firmicutes (29.5%), while in the Han ethnic group, Firmicutes (46.5%) was most dominant, followed by Proteobacteria (43.7%). At the genus level, Cupriavidus (26.28%), Staphylococcus (17.36%), and Streptococcus (13.11%) were the most abundant in the Li group, while Acinetobacter (28.72%), Staphylococcus (28.38%), and Streptococcus (9.45%) dominated in the Han group [71].

Species-level analysis revealed differences in abundance, with Cupriavidus lacunae and Streptococcus himalayensis being more abundant in the Li group, and Staphylococcus petrasii and Acinetobacter proteolyticus being more prominent in the Han group. Additionally, Han mothers exhibited higher alpha diversity (Chao1 and Ace indices) compared to Li mothers. Beta-diversity analysis showed a distinct separation between the two ethnic groups. Differences were also noted in the core microbiota, with Cupriavidus lacunae and Streptococcus himalayensis significantly abundant in the Li group, and Staphylococcus petrasii and Acinetobacter proteolyticus more prevalent in the Han group. Delivery mode further influenced the microbiota, with Han mothers sharing a core microbiota of Acinetobacter, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus between cesarean and vaginal deliveries, while Li mothers shared genera such as Cupriavidus, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus [71].

3.2.21. Parity

Parity was reported to have no significant effect on the diversity of breast milk microbiota. Du et al. found that both alpha and beta diversity measures showed no significant differences between milk samples from mothers with varying numbers of pregnancies [41].

3.2.22. Entero-Mammary Pathway

The concept of the entero-mammary pathway proposes that maternal gut bacteria can translocate to the mammary glands and colonize breast milk, including colostrum [41]. In the study by Du et al., colostrum exhibited greater microbial abundance and a distinct composition compared to nipple skin, with 111 unique OTUs, supporting the hypothesis of an entero-mammary pathway. Anaerobes such as Bifidobacterium, Pantoea, and Enterobacteriaceae were mainly identified in colostrum, while Staphylococcus, Bacteroides, and Parabacteroides dominated the nipple skin. Infant sex, gestational age, and maternal factors (e.g., delivery mode, IAP) showed limited influence on diversity, though cesarean delivery and full-term birth were associated with increased Bifidobacteria [41].

4. Discussion

The results of our study indicate that colostrum microbiota is diverse and predominantly consists of genera such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Enterococcus, with significant presence of Acinetobacter, Prevotella, Corynebacterium, and Rhodobacteraceae. Additionally, the presence of other microbial groups, including fungi and archaea, was observed.

Based on the studies included in this review, there is evidence suggesting that factors such as maternal body mass index (BMI), delivery mode, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), feeding type, and geographic location influence the composition of colostrum microbiota. Additionally, maternal stress, perinatal antibiotic exposure, maternal age, and maternal secretor status were also identified as potential factors affecting the microbiota. However, many of the studies were small and the results varied across different populations and conditions. Therefore, caution should be exercised in drawing definitive conclusions about the relative impact of these factors on the composition of colostrum microbiota.

Various mechanisms were described regarding the mechanism by which microbes reach and colonize colostrum. One such mechanism involves retrograde flow, where breast milk (BM) flows back into the mammary ducts, allowing bacteria to enter the mammary glands [74]. Studies, such as Cortez et al., suggest that BM may contribute to the colonization of the infant’s oral cavity, as buccal administration of colostrum altered the oral microbiota in low-birth-weight infants [75]. Additionally, bacteria were detected in colostrum before suckling, indicating that microbes are present in the milk prior to the infant’s first feed [36]. Maternal skin microbiota is also a possible source of colostrum microbes, with skin-associated bacteria like Staphylococcus, Cutibacterium, and Corynebacterium found in BM [76]. Moreover, the entero-mammary pathway, where gut bacteria migrate to the mammary glands, is thought to play a part, particularly for anaerobic bacteria such as Bifidobacterium [76]. Finally, bacterial translocation, a physiological event heightened during pregnancy and lactation as described in rodents, may also contribute to the influx of bacteria into colostrum [77]. These mechanisms highlight the multifaceted nature of microbial colonization in colostrum.

Several studies reported higher diversity in colostrum microbiota compared to mature breast milk. Khodayar-Pardo et al. found greater microbial diversity in colostrum, while Xie et al. noted higher microbial richness in colostrum, although no significant differences in diversity indices were observed [48,71]. Boix-Amoros et al. found no significant differences across colostrum, transitional milk, and mature milk, but highlighted that non-viable bacteria and extracellular DNA could affect qPCR results, suggesting that viable bacterial numbers may be lower than reported [29]. These findings suggest that colostrum is a more diverse source of microorganisms. The increased microbial diversity in colostrum is likely due to the open tight junctions of the mammary gland epithelium in the early days post-birth, allowing the transport of immune cells into the mammary gland [76]. High leucocyte levels in colostrum reflect the need for immunological protection in the newborn. These immune cells are closely associated with a significant proportion of milk bacteria, influencing the milk microbiota composition. As lactation progresses, immune cell populations decrease, causing changes in milk microbiota composition [4].

Some studies reported that colostrum contains a higher bacterial diversity compared to both maternal and infant feces [31,57]. Xie et al. highlighted the significant transfer of bacteria from colostrum to infant feces, further confirming differences in microbiota composition between the two [71]. This raises the following question: why is it important to present such a diverse colostrum microbiota? Boix Amoros et al. suggests that no correlation between human and bacterial cells was found in milk, indicating that the milk microbiota is not perceived as an infection by the mother’s immune system [29]. Instead, the immune response is directed toward specific microorganisms like Staphylococcus, without triggering an inflammatory response in the mammary ducts. The presence of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) in colostrum is of particular interest due to their antimicrobial properties. LAB produce antimicrobial peptides, such as bacteriocins, which are considered promising natural preservatives and therapeutic agents [78,79]. LAB inhibit the growth of harmful pathogens such as Bacillus cereus, E. coli, E. faecalis, Listeria monocytogenes, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and Salmonella serotype Enteritidis [80]. Moreover, Weissella, a genus of LAB, inhibits biofilm formation and exhibits anti-inflammatory effects, further highlighting the protective role of colostrum microbiota in infant health [81].

In addition to antimicrobial properties, the colostrum microbiota provides several health benefits for both the infant and the mother. Research by Suarez Martinez et al. indicates that colostrum contains diverse bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Streptococcus, which are essential for the early colonization of the infant gut [82]. These bacteria aid in digestion and contribute to the maturation of the immune system. Furthermore, studies showed that the microbiota in colostrum is more diverse than that in mature milk, with genera like Weissella and Leuconostoc being more prevalent in colostrum. As a result, breastfed infants have a gut microbiota that is less diverse but richer in beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, which are associated with a lower risk of allergies and improved immune function [83,84]. Bifidobacterium, for example, releases short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate and propionate, which lower stool pH and create an unfavorable environment for pathogenic bacteria, reducing the risk of food allergies [85].

The composition of the breast milk microbiota also plays a role in maternal health. Heikkla et al. found that species such as S. epidermidis, S. salivarius, E. faecalis, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, and Leuconostoc suppress the growth of S. aureus, a major cause of mastitis [86]. Differences in the milk microbiota could explain why some women experience recurrent mastitis while others do not, suggesting that a healthy and diverse milk microbiota may help protect mothers from infections like mastitis [82].

Several maternal and environmental factors appear to influence the composition of breast milk microbiota. The stage of lactation plays a central role, with colostrum generally showing higher bacterial diversity compared to transitional and mature milk [29,48]. Mode of delivery has also been consistently associated with microbial differences, with vaginal birth favoring the transfer of maternal vaginal and gut microbes, whereas cesarean section is linked to altered microbial communities in milk [31,49]. Maternal characteristics, including BMI and GDM, further shape microbial profiles, with overweight mothers and those with GDM showing reduced bacterial diversity and altered abundance of genera such as Staphylococcus and Lactobacillus [31]. Geographic location and maternal diet also appear to contribute, as differences appear in milk microbiota composition between women in Europe, Africa, and Asia, suggesting the influence of environmental exposures and nutritional patterns [40,65].Additional influences include maternal age, parity, perinatal antibiotic use, infant sex, and even milk collection method, which may introduce external bacteria [41,56].

Our study has limitations. Firstly, most studies included in this review were designed as observational cohorts, which are prone to residual confounding. Secondly, the heterogeneity among included studies regarding study design, sample size, data collection methods, and analysis limited the ability to perform a meta-analysis and made direct comparisons challenging. Also, some studies had small sample sizes, which may affect the reliability of the findings. Lastly, language restrictions may have led to the exclusion of relevant studies.

5. Conclusions

In summary, colostrum contains a highly diverse microbiota, predominantly comprising genera such as Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Enterococcus, along with other microbial groups including fungi and archaea. The composition and diversity of this microbiota are shaped by a range of intrinsic factors, such as maternal body mass index (BMI), age, secretor status, stress levels, and health conditions like gestational diabetes, as well as extrinsic factors, including delivery mode, antibiotic exposure, feeding practices, and geographic location.

Colostrum microbiota plays a pivotal role in both infant and maternal health. In infants, it promotes early gut colonization, aids digestion, supports immune system maturation, and provides protection against pathogens through mechanisms such as the production of antimicrobial peptides by lactic acid bacteria. In mothers, a diverse milk microbiota may help prevent infections such as mastitis and contribute to overall mammary gland health.

This microbiota plays a crucial role in promoting maternal and infant health, particularly in the early stages of life. Interventions aimed at enhancing the beneficial properties of colostrum or improving its microbial composition could offer significant opportunities to positively impact infant health, especially in promoting gut health and immune development. Further research with larger, well-designed studies is needed, focusing on the identification of the full range of microbes in colostrum, including fungi, archaea, and viruses, and exploring the interactions between these microbes and their potential effects on infant health.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children12101336/s1, PRISMA checklist; PROSPERO registered protocol.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.T. and E.K.; methodology, A.T.; formal analysis, A.T.; investigation, A.T.; data curation, A.T., E.K. and N.A.X.; writing—A.T. and N.A.X.; writing—review and editing, N.A.X.; supervision, T.B. and R.S.; project administration, T.B., R.S., N.I., Z.I., P.V. and S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ballard, O.; Morrow, A.L. Human Milk Composition. Pediatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013, 60, 49–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garofoli, F.; Civardi, E.; Pisoni, C.; Angelini, M.; Ghirardello, S. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Allergic Properties of Colostrum from Mothers of Full-Term and Preterm Babies: The Importance of Maternal Lactation in the First Days. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellote, C.; Casillas, R.; Ramírez-Santana, C.; Pérez-Cano, F.J.; Castell, M.; Moretones, M.G.; López-Sabater, M.C.; Franch, Í. Premature Delivery Influences the Immunological Composition of Colostrum and Transitional and Mature Human Milk. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 1181–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassiotou, F.; Geddes, D.T.; Hartmann, P.E. Cells in Human Milk. J. Hum. Lact. 2013, 29, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, W.L.; Theil, P.K. Perspectives on Immunoglobulins in Colostrum and Milk. Nutrients 2011, 3, 442–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bardanzellu, F.; Fanos, V.; Reali, A. “Omics” in Human Colostrum and Mature Milk: Looking to Old Data with New Eyes. Nutrients 2017, 9, 843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duijts, L.; Jaddoe, V.W.V.; Hofman, A.; Moll, H.A. Prolonged and Exclusive Breastfeeding Reduces the Risk of Infectious Diseases in Infancy. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e18–e25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladomenou, F.; Moschandreas, J.; Kafatos, A.; Tselentis, Y.; Galanakis, E. Protective effect of exclusive breastfeeding against infections during infancy: A prospective study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2010, 95, 1004–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinzen-Derr, J.; Poindexter, B.; Wrage, L.; Morrow, A.L.; Stoll, B.; Donovan, E.F. Role of human milk in extremely low birth weight infants’ risk of necrotizing enterocolitis or death. J. Perinatol. 2008, 29, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munblit, D.; Verhasselt, V. Allergy prevention by breastfeeding: Possible mechanisms and evidence from human cohorts. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 16, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, F.; Comberiati, P.; Munblit, D.; Piacentini, G.L.; Antoniazzi, E.; Zanoni, L.; Boner, A.L.; Peroni, D.G. Breast-Milk Characteristics Protecting Against Allergy. Endocr. Metab. Immune Disord. Drug Targets 2014, 14, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, M.W. Risk of Overweight Among Adolescents Who Were Breastfed as Infants. JAMA 2001, 285, 2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelishadi, R.; Farajian, S. The protective effects of breastfeeding on chronic non-communicable diseases in adulthood: A review of evidence. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2014, 3, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anne, R.P.; Kumar, J.; Kumar, P.; Meena, J. Effect of oropharyngeal colostrum therapy on neonatal sepsis in preterm neonates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2023, 78, 471–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.; Meena, J.; Ranjan, A.; Kumar, P. Oropharyngeal application of colostrum or mother’s own milk in preterm infants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Rev. 2023, 81, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Z.Y.; Huang, C.; Lei, L.; Chen, L.C.; Wei, L.J.; Zhou, J.; Martins, C.C. The effect of oropharyngeal colostrum administration on the clinical outcomes of premature infants: A meta-analysis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2023, 144, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Togo, A.; Grine, G.; Khelaifia, S.; des Robert, C.; Brevaut, V.; Caputo, A.; Baptiste, E.; Bonnet, M.; Levasseur, A.; Drancourt, M.; et al. Culture of Methanogenic Archaea from Human Colostrum and Milk. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannaraj, P.S.; Li, F.; Cerini, C.; Bender, J.M.; Yang, S.; Rollie, A.; Adisetiyo, H.; Zabih, S.; Lincez, P.J.; Bittinger, K.; et al. Association Between Breast Milk Bacterial Communities and Establishment and Development of the Infant Gut Microbiome. JAMA Pediatr. 2017, 171, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, V.; Maldonado-Barragán, A.; Moles, L.; Rodriguez-Baños, M.; Campo Rdel Fernández, L.; Fernández, L.; Jiménez, E.; Fernández, M.; Rodríguez, J.M.; Delgado, S.; et al. Sharing of Bacterial Strains Between Breast Milk and Infant Feces. J. Hum. Lact. 2012, 28, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Curtis, N. The influence of the intestinal microbiome on vaccine responses. Vaccine 2018, 36, 4433–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, C.J.; Ajami, N.J.; O’Brien, J.L.; Hutchinson, D.S.; Smith, D.P.; Wong, M.C.; Ross, M.C.; Lloyd, R.E.; Doddapaneni, H.; Metcalf, G.A.; et al. Temporal development of the gut microbiome in early childhood from the TEDDY study. Nature 2018, 562, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, M.C.; Stiemsma, L.T.; Amenyogbe, N.; Brown, E.M.; Finlay, B. The Intestinal Microbiome in Early Life: Health and Disease. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knights, D.; Lassen, K.G.; Xavier, R.J. Advances in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis: Linking host genetics and the microbiome. Gut 2013, 62, 1505–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridaura, V.K.; Faith, J.J.; Rey, F.E.; Cheng, J.; Duncan, A.E.; Kau, A.L.; Griffin, N.W.; Lombard, V.; Henrissat, B.; Bain, J.; et al. Gut Microbiota from Twins Discordant for Obesity Modulate Metabolism in Mice. Science 2013, 341, 6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostic, A.D.; Gevers, D.; Siljander, H.; Vatanen, T.; Hyötyläinen, T.; Hämäläinen, A.M.; Peet, A.; Tillmann, V.; Salo, H.; Virtanen, S.M.; et al. The Dynamics of the Human Infant Gut Microbiome in Development and in Progression toward Type 1 Diabetes. Cell Host Microbe 2015, 17, 260–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, V.; Ali, A.; Fuentes, S.; Korpela, K.; Kazi, M.; Tate, J.; Arakawa, Y.; Axelin, A.; Bode, L.; Browne, H.; et al. Rotavirus vaccine response correlates with the infant gut microbiota composition in Pakistan. Gut Microbes 2017, 9, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grainger, M.; Haddaway, N. Evidence Synthesis Hackathon. PRISMA2020. 2025. Available online: https://www.eshackathon.org/software/PRISMA2020.html (accessed on 31 May 2025).

- Urashima, T.; Ajisaka, K.; Ujihara, T.; Nakazaki, E. Recent advances in the science of human milk oligosaccharides. BBA Adv. 2025, 7, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boix-Amorós, A.; Collado, M.C.; Mira, A. Relationship between Milk Microbiota, Bacterial Load, Macronutrients, and Human Cells during Lactation. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boix-Amorós, A.; Martinez-Costa, C.; Querol, A.; Collado, M.C.; Mira, A. Multiple Approaches Detect the Presence of Fungi in Human Breastmilk Samples from Healthy Mothers. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Collado, M.C.; Laitinen, K.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E.; Mira, A. The human milk microbiome changes over lactation and is shaped by maternal weight and mode of delivery. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Rubio, R.; Kunz, C.; Rudloff, S.; García-Mantrana, I.; Crehuá-Gaudiza, E.; Martínez-Costa, C. Association of Maternal Secretor Status and Human Milk Oligosaccharides With Milk Microbiota. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2019, 68, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.W.; Lin, Y.L.; Huang, M.S. Profiles of commensal and opportunistic bacteria in human milk from healthy donors in Taiwan. J. Food Drug Anal. 2018, 26, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, M.C.; Laitinen, K.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Maternal weight and excessive weight gain during pregnancy modify the immunomodulatory potential of breast milk. Pediatr. Res. 2012, 72, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corona-Cervantes, K.; García-González, I.; Villalobos-Flores, L.E.; Hernández-Quiroz, F.; Piña-Escobedo, A.; Hoyo-Vadillo, C.; Rangel-Calvillo, M.N.; García-Mena, J. Human milk microbiota associated with early colonization of the neonatal gut in Mexican newborns. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damaceno, Q.S.; Souza, J.P.; Nicoli, J.R.; Paula, R.L.; Assis, G.B.; Figueiredo, H.C.; Azevedo, V.; Martins, F.S. Evaluation of Potential Probiotics Isolated from Human Milk and Colostrum. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2017, 9, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davé, V.; Street, K.; Francis, S.; Bradman, A.; Riley, L.; Eskenazi, B. Bacterial microbiome of breast milk and child saliva from low-income Mexican-American women and children. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 79, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deflorin, N.; Ehlert, U.; Amiel Castro, R.T. Associations of Maternal Salivary Cortisol and Psychological Symptoms With Human Milk’s Microbiome Composition. Biopsychosoc. Sci. Med. 2025, 87, 33–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewanto, N.E.F.; Firmansyah, A.; Sungkar, A.; Dharmasetiawani, N.; Sastroasmoro, S.; Kresno, S.B.; Hadi, U. The effect of Bifidobacterium animalis lactis HNO19 supplementation among pregnant and lactating women on interleukin-8 level in breast milk and infant’s gut mucosal integrity. Med. J. Indones. 2017, 26, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drago, L.; Toscano, M.; De Grandi, R.; Grossi, E.; Padovani, E.M.; Peroni, D.G. Microbiota network and mathematic microbe mutualism in colostrum and mature milk collected in two different geographic areas: Italy versus Burundi. ISME J. 2016, 11, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.; Qiu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Huang, Z.; Xie, R.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Liu, J.; et al. Comparative study on the microbiota of colostrum and nipple skin from lactating mothers separated from their newborn at birth in China. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 932495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubos, C.; Vega, N.; Carvallo, C.; Navarrete, P.; Cerda, C.; Brunser, O.; Gotteland, M. Identification of Lactobacillus spp. in colostrum from Chilean mothers. Arch. Latinoam. Nutr. 2011, 61, 66–68. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Tuñas Mdel, C.; Pérez-Muñuzuri, A.; Trastoy-Pena, R.; Pérez del Molino, M.L.; Couce, M.L. Effects of Maternal Stress on Breast Milk Production and the Microbiota of Very Premature Infants. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gámez-Valdez, J.S.; García-Mazcorro, J.F.; Montoya-Rincón, A.H.; Rodríguez-Reyes, D.L.; Jiménez-Blanco, G.; Rodríguez, M.T.A.; López, R.; Torres, E.; Hernández, C.; Sánchez, P.; et al. Differential analysis of the bacterial community in colostrum samples from women with gestational diabetes mellitus and obesity. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 24373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, H.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, H.; Sun, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Q.; Huang, M.; et al. Human milk microbiota and oligosaccharides in colostrum and mature milk: Comparison and correlation. Front. Nutr. 2024, 11, 1512700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhang, G.; Xu, S.; Xiang, Q.; Huang, M.; Zhao, M.; Li, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, J.; et al. Antibiotic treatments to mothers during the perinatal period leaving hidden trouble on infants. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2022, 181, 3459–3471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karampatsas, K.; Faal, A.; Jaiteh, M.; Garcia-Perez, I.; Aller, S.; Shaw, A.G.; Kampmann, B.; Prentice, A.; Moore, S.E.; Lloyd-Price, J.; et al. Gastrointestinal, vaginal, nasopharyngeal, and breast milk microbiota profiles and breast milk metabolomic changes in Gambian infants over the first two months of lactation: A prospective cohort study. Medicine 2022, 101, e31419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodayar-Pardo, P.; Mira-Pascual, L.; Collado, M.C.; Martínez-Costa, C. Impact of lactation stage, gestational age and mode of delivery on breast milk microbiota. J. Perinatol. 2014, 34, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhou, Q.; Peng, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Huang, Y.; et al. The Effect of Breast Milk Microbiota on the Composition of Infant Gut Microbiota: A Cohort Study. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, W.; Jiang, T.; Chen, L. Diversity and temporal dynamics of breast milk microbiome and its influencing factors in Chinese women during the first 6 months postpartum. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1016759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastromarino, P.; Capobianco, D.; Miccheli, A.; Praticò, G.; Campagna, G.; Laforgia, N.; Marcellini, S.; Salimei, E.; Menghini, P.; Mattarelli, P.; et al. Administration of a multistrain probiotic product (VSL#3) to women in the perinatal period differentially affects breast milk beneficial microbiota in relation to mode of delivery. Pharmacol. Res. 2015, 95–96, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, L.; Manzano, S.; Fernández, L.; Montilla, A.; Corzo, N.; Ares, S.; Rueda, R.; Maldonado, A.; Rodríguez, M.; Martín, V.; et al. Bacteriological, biochemical, and immunological properties of colostrum and mature milk from mothers of extremely preterm infants. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2015, 60, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolopoulou, G.; Tsironi, T.; Halvatsiotis, P.; Petropoulou, E.; Genaris, N.; Vougiouklaki, D.; Koutelidakis, A.; Papadimitriou, A.; Vasileiou, A.; Antoniou, C.; et al. Analysis of the major probiotics in healthy women’s breast milk by realtime PCR: Factors affecting the presence of those bacteria. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obermajer, T.; Lipoglavšek, L.; Tompa, G.; Treven, P.; Lorbeg, P.M.; Matijašić, B.B.; Rupnik, M.; Novak, F.; Klančar, U.; Štrukelj, B.; et al. Colostrum of healthy Slovenian mothers: Microbiota composition and bacteriocin gene prevalence. PLoS ONE 2014, 10, e0123324. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.; Zhou, J.; Tu, H.; Tu, R.; Chang, H.; Chen, J.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, M.; et al. Lactation-dependent vertical transmission of natural probiotics from the mother to the infant gut through breast milk. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 304–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakwinska, O.; Moine, D.; Delley, M.; Combremont, S.; Rezzonico, E.; Descombes, P.; Vinyes-Pares, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, P.; Thakkar, S.K. Microbiota in Breast Milk of Chinese Lactating Mothers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, P.; Al Mohannadi, N.; Murugesan, S.; Almarzooqi, F.; Kabeer, B.S.A.; Marr, A.K.; Kino, T.; Brummaier, T.; Terranegra, A.; McGready, R.; et al. Unveiling the dynamics of the breast milk microbiome: Impact of lactation stage and gestational age. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solís, G.; de Los Reyes-Gavilan, C.G.; Fernández, N.; Margolles, A.; Gueimonde, M. Establishment and development of lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria microbiota in breast-milk and the infant gut. Anaerobe 2010, 16, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Tao, L.; Qian, C.; Xue, P.P.; Du, S.S.; Tao, Y.N. Human milk oligosaccharides: Bridging the gap in intestinal microbiota between mothers and infants. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1386421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, M.; Xu, C.; Chen, K.; Yan, Q.; Mao, W.; Liu, W.; Ritz, B. Hexachlorocyclohexane exposure alters the microbiome of colostrum in Chinese breastfeeding mothers. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254 Pt A, 112900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.N.; Tong, X.K.; Qian, C.; Wan, H.; Zuo, J.P. Microbial quantitation of colostrum from healthy breastfeeding women and milk from mastitis patients. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2020, 9, 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia-González, A.; Vélez-Ixta, J.M.; Bueno-Hernández, N.; Piña-Escobedo, A.; Briones-Garduño, J.C.; de la Rosa-Ruiz, L.; Aguayo-Guerrero, J.; Mendoza-Martínez, V.M.; Snowball-del-Pilar, L.; Escobedo, G.; et al. Maternal Consumption of Non-Nutritive Sweeteners during Pregnancy Is Associated with Alterations in the Colostrum Microbiota. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toscano, M.; De Grandi, R.; Peroni, D.G.; Grossi, E.; Facchin, V.; Comberiati, P.; Drago, L. Impact of delivery mode on the colostrum microbiota composition. BMC Microbiol. 2017, 17, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuominen, H.; Rautava, S.; Collado, M.C.; Syrjänen, S.; Rautava, J. HPV infection and bacterial microbiota in breast milk and infant oral mucosa. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Jiang, J.; Lu, M.; Tong, W.; Zhou, R.; Li, J.; Yuan, J.; Wang, F.; Li, D. Human milk microbiota development during lactation and its relation to maternal geographic location and gestational hypertensive status. Gut Microbes 2020, 11, 1438–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.; Zou, J.; Zhang, C.; Yan, H.; Ye, X.; Chen, Y. Microbial community structure of colostrum in women with antibiotic exposure immediately after delivery. Breastfeed. Med. 2022, 17, 940–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Xia, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Q.; Yang, Z.; Ren, J. Microbial diversity and correlation between breast milk and the infant gut. Foods 2023, 12, 1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.E.; Carrothers, J.M.; Lackey, K.A.; Beatty, N.F.; York, M.A.; Brooker, S.L.; Peterson, H.K.; Eppensteiner, E.; Serao, M.C.; Kellermayer, R. Human milk microbial community structure is relatively stable and related to variations in macronutrient and micronutrient intakes in healthy lactating women. J. Nutr. 2017, 147, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.E.; Carrothers, J.M.; Lackey, K.A.; Beatty, N.F.; Brooker, S.L.; Peterson, H.K.; Eppensteiner, E.; Serao, M.C.; Kellermayer, R.; Bode, L. Strong multivariate relations exist among milk, oral, and fecal microbiomes in mother-infant dyads during the first six months postpartum. J. Nutr. 2019, 149, 902–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, R.G.; Mata, L.J. Bacteria in colostrum and milk of Guatemalan Indian women. J. Trop. Pediatr. 1969, 15, 159–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Zhang, H.; Ni, Y.; Peng, Y. Contrasting Diversity and Composition of Human Colostrum Microbiota in a Maternal Cohort With Different Ethnic Origins but Shared Physical Geography (Island Scale). Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 934232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, R.; Langa, S.; Reviriego, C.; Jiménez, E.; Marín, M.L.; Xaus, J.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, J.M. Human milk is a source of lactic acid bacteria for the infant gut. J. Pediatr. 2003, 143, 754–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aakko, J.; Kumar, H.; Rautava, S.; Wise, A.; Autran, C.; Bode, L.; Isolauri, E.; Salminen, S. Human Milk Oligosaccharide Categories Define the Microbiota Composition in Human Colostrum. Benef. Microbes 2017, 8, 563–567. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28726512/ (accessed on 17 June 2025). [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, D.T.; Kent, J.C.; Owens, R.A.; Hartmann, P.E. Ultrasound Imaging of Milk Ejection in the Breast of Lactating Women. Pediatrics 2004, 113, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortez, R.V.; Fernandes, A.; Sparvoli, L.G.; Padilha, M.; Feferbaum, R.; Neto, C.M.; Taddei, C.R. Impact of oropharyngeal administration of colostrum in preterm newborns’ oral microbiome. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; McLoughlin, G.; Nicol, M.; Geddes, D.; Stinson, L. Residents or tourists: Is the lactating mammary gland colonized by residential microbiota? Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, P.F.; Doré, J.; Leclerc, M.; Levenez, F.; Benyacoub, J.; Serrant, P.; Segura-Roggero, I.; Schiffrin, E.J.; Donnet-Hughes, A. Bacterial imprinting of the neonatal immune system: Lessons from maternal cells? Pediatrics 2007, 119, e724–e732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.; Jobby, R. Bacteriocins from lactic acid bacteria and their potential clinical applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 194, 4377–4399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arqués, J.L.; Rodríguez, E.; Langa, S.; Landete, J.M.; Medina, M. Antimicrobial Activity of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Dairy Products and Gut: Effect on Pathogens. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 584183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, N.A.; Saraiva Ma, F.; Duarte Ea, A.; de Carvalho, E.A.; Vieira, B.B.; Evangelista-Barreto, N.S. Probiotic properties of lactic acid bacteria isolated from human milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 811–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.S.; Lee, N.K.; Choi, A.J.; Choe, J.S.; Bae, C.H.; Paik, H.D. Anti-Inflammatory Potential of Probiotic Strain Weissella cibaria JW15 Isolated from Kimchi through Regulation of NF-κB and MAPKs Pathways in LPS-Induced RAW 264.7 Cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Martínez, C.; Santaella-Pascual, M.; Yagüe-Guirao, G.; Martínez-Graciá, C. Infant gut microbiota colonization: Influence of prenatal and postnatal factors, focusing on diet. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1236254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalliomäki, M.; Kirjavainen, P.; Eerola, E.; Kero, P.; Salminen, S.; Isolauri, E. Distinct patterns of neonatal gut microflora in infants in whom atopy was and was not developing. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2001, 107, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odiase, E.; Frank, D.N.; Young, B.E.; Robertson, C.E.; Kofonow, J.M.; Davis, K.N.; Schuster, M.; Li, J.; Nicholson, J.K.; Smith, K. The gut microbiota differ in exclusively breastfed and formula-fed United States infants and are associated with growth status. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 2612–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayen, S.M.; den Hartog Jager, C.F.; Knulst, A.C.; Knol, E.F.; Garssen, J.; Willemsen, L.E.M.; van Esch, B.C.A.M.; Pasmans, S.G.M.A.; Knipping, K.; Savelkoul, H.F.J. Non-digestible oligosaccharides can suppress basophil degranulation in whole blood of peanut-allergic patients. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heikkila, M.P.; Saris, P.E.J. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus by the commensal bacteria of human milk. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).