Abstract

Background/Objectives: The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly affected the lives of adolescents worldwide, especially those living with chronic diseases. This study aims to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases. Methods: This is a scoping review that follows the guidelines proposed by JBI. Eligibility criteria include articles focusing on adolescents aged 10 to 19 during the COVID-19 pandemic, regardless of chronic diseases. Searches were performed in PUBMED, LILACS, CINAHL, SCOPUS, grey literature, and manual searches in March 2024. Results: This review is composed of 35 articles. The analysis revealed two main categories: (1) Adolescents facing social isolation, school closure, and new family interactions, striving to reinvent themselves, and (2) Chasing the best decision: following up the chronic disease while fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. These categories encompass subcategories highlighting changes in social and family interactions and lifestyle habits. The findings suggest a multifaceted interaction of factors influencing adolescents’ well-being, including improved family bonding, heightened disease management, and increased stress and strains on resources. Conclusions: This review emphasizes the importance of long-term follow-up and social inclusion efforts for adolescents with chronic diseases and their families, addressing their unique needs during public health crises.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is emblematic of a modern public health crisis that has led to several changes in the world [1]. Actions to prevent the spread of the virus were adopted, and people’s daily lives have changed significantly [2]. Social distancing, school closures, the adoption of remote learning, and closures of outdoor recreational spaces and non-essential businesses were restrictions that inevitably affected the behavior, development, and well-being of children and their parents [3,4,5].

Although healthy children and adolescents are believed to be less susceptible to developing the severe form of the disease, those with chronic illnesses are characterized as a high-risk group for COVID-19 [6,7,8,9]. Chronic diseases (CD), defined as conditions that require continuous medical attention and have prolonged or indefinite durations, amplify the vulnerabilities of this population [10]. Adolescents with chronic illnesses are particularly vulnerable; the combination of their ongoing health needs and the restrictions imposed by the pandemic intensifies their dependence on caregivers, increasing the sense of uncertainty and the challenges of adapting to this new reality [11,12]. The caregiving burden borne by families of adolescents with chronic conditions poses multifaceted challenges, influencing familial dynamics and functioning [11,12,13].

Evidence shows that the pandemic has disproportionately affected the health of individuals under 18 and those with pre-existing health conditions, exacerbating existing disparities in healthcare access and outcomes, such as racial and economic ones [8]. Especially among adolescents, the period is marked by increased socialization and peer interaction, confronting a paradox of imposed isolation undermining developmental autonomy. This paradox is exacerbated for adolescents grappling with chronic diseases, mainly due to their dependency on parental support [14]. Because of treatment limitations and restricted follow-up procedures, these consequences can significantly affect the post-pandemic scenario. To restore healthcare continuity and enhance its effectiveness, it is crucial to pinpoint and comprehend the specific areas that require attention within this population [12,13,15]. While several studies have addressed the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents, to our knowledge, no review has been found in the literature that gathers evidence about the effects of COVID-19 on adolescents with chronic diseases. In this context, understanding the repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases can fill the gap in scientific knowledge. It can also provide information for health professionals to promote evidence-based care that meets the specific needs of this population [15,16]. Consequently, this review aims to explore the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

This is a scoping review, an increasingly common evidence synthesis used to answer broad research questions by mapping evidence from multiple sources [17]. Moreover, scoping review results are essential for identifying knowledge gaps that future research should fill and where additional research efforts are needed, particularly in contexts with limited financial resources for research investment [18,19].

The steps proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) were used to guide the development of this review: (I) Development of the research question; (II) Definition of inclusion criteria; (III) Development of search strategies; (IV) Screening and selection of studies; (V) Data extraction; (VI) Analysis of evidence; (VII) Presentation of results [20]. The checklist PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews) was used to guide this review report [19]. This review was not previously registered.

2.1. Search Methods and Selection Criteria

The PCC tool was used as a guide to formulate the research question [20]. The P is for population—adolescents with chronic diseases, C is for concept—impacts on daily life, and C is for context—COVID-19 pandemic. The developed research question is the following: What are the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic illnesses? The PCC structure search strategy comprised keywords, descriptors, and Boolean operators AND and OR. The searches were developed in the PubMed, CINAHL, LILACS, and SCOPUS databases. Each search strategy was adapted to the particularities of the databases, and an example is presented in Supplementary File S1.

Gray literature searches were conducted using Google Scholar. In addition, a manual search of the reference list of included studies was performed. The search was conducted in March 2024. Considering the authors’ language skills, the search was limited to studies published in Portuguese, Spanish, and English. We included primary or secondary studies conducted from March 2020 to January 2024, employing any methodological design or gray literature that addressed the routine of adolescents aged 10 to 19 years, as defined by the World Health Organization [10], living with chronic diseases [21], such as asthma, cystic fibrosis, and diabetes, during the COVID-19 pandemic. The focus was on physical health conditions. Studies published before March 2020 were excluded as we aimed to focus on the period after the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic in March 2020. Studies were excluded if they investigated the viewpoints of families or healthcare professionals, included both children and adolescents without providing separate analyses for each group, utilized data from hospital records only, consisted of opinion articles or expert consensus studies, and conference abstracts or proceedings.

2.2. Data Extraction and Analysis

Studies identified in the databases were screened to exclude duplicates and then exported to Rayyan® to verify titles and abstracts. This screening process was carried out independently by two reviewers. Any selection conflicts were resolved in a meeting between the reviewers. In the next phase, studies were read independently by the two reviewers in full. Selection conflicts were resolved in meetings to obtain the final sample. During this process, the inter-rater reliability obtained by Cohen’s Kappa was 0.87, indicating an almost perfect agreement between reviewers [22].

Two reviewers performed data extraction from the included studies. A form developed by the authors was created, and the information retrieved consisted of author, year, country, and objective; study design and data collection; population, sample, and chronic diseases; and primary outcomes. A third reviewer reviewed the extracted data [17].

For data analysis, the extracted data were coded according to the repercussions observed in the studies and then organized into categories and their respective subcategories [15]. Subsequently, a third reviewer thoroughly reviewed the data. Data were presented through tables, figures, and narrative descriptions.

3. Results

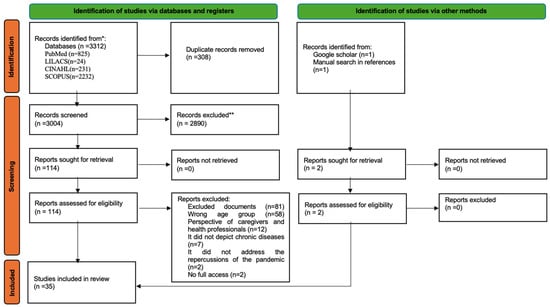

The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) shows the studies’ selection process through the review [23]. From 3312 articles, 35 were selected for the final sample.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the screening process (Source: [23]). [color reproduction on the web]. * According to the search strategy; ** Records excluded during the title/abstract screening phase.

3.1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the critical characteristics of the articles analyzed in this study. The research was conducted across several regions worldwide, with a notable concentration in Europe (n = 13; 37.1%), followed by the Americas (n = 12; 34.2%) and the Middle East (n = 7; 20%). Additionally, a smaller number of studies were carried out in Asia (n = 1; 2.9%), Africa (n = 1; 2.9%), and Oceania (n = 1; 2.9%).

Table 1.

Characterization table of included studies. * Studies in which participants’ ages are marked with an “*” had only the results pertaining to the inclusion criteria (adolescents aged 10–19 years) analyzed.

In general, the studies aimed to assess the adolescents’ psychosocial function and their quality of life (n = 29; 82.8%), the ongoing chronic disease follow-up in the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 15; 42.8%), and the adherence to COVID-19 preventive measures (n = 5; 14.3%). Six studies (17.1%) approached disparities in healthcare access and outcomes, although only one of them (2.8%) addressed the influences of racial issues on this aspect. Regarding study designs, 25 were quantitative (71.4%), 5 were qualitative (14.3%), and 5 used mixed methods (14.3%). The sample predominantly consisted of adolescents with type 1 or type 2 diabetes (n = 17; 48.6%), followed by those with intestinal inflammatory diseases (n = 5; 14.3%) and asthma (n = 5; 14.3%). Other diagnoses, such as cystic fibrosis, cancer, and heart/kidney diseases, were also represented in the sample. Eleven studies (31.4%) included parents’ perspectives or patients of different ages. Their results, however, allowed us to extract and analyze data related explicitly to adolescents independently.

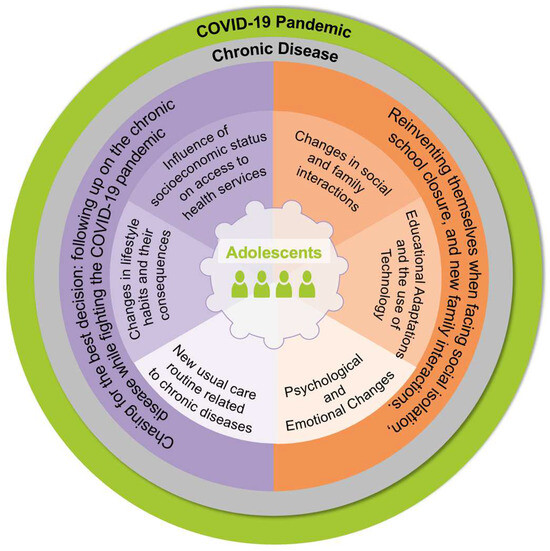

3.2. Categories and Subcategories

The main types of impacts were triggered mainly by the isolation from peers and families’ dynamics during the adjustment to the pandemic period, as represented in Table 2. The impacts described in the table were diverse and depended on various related aspects, which affected each family differently. Two categories and their respective subcategories summarize the findings: (1) Reinventing themselves when facing social isolation, school closure, and new family interactions and (2) Chasing for the best decision: following up the chronic disease while fighting the COVID-19 pandemic.

Table 2.

COVID-19 impacts and related affecting aspects on adolescents with chronic diseases.

3.2.1. Category 1—Reinventing Themselves When Facing Social Isolation, School Closure, and New Family Interactions

This category comprises three subcategories: (a) Changes in social and family interactions, (b) Educational adaptations and the use of technology, and (c) Psychological and emotional changes.

(a) Changes in social and family interactions: The COVID-19 pandemic brought about significant changes in the family and social interactions of adolescents with chronic diseases [25,51]. With the need to stay home, these adolescents spent more time with their families. This increased presence of parents in the household had a dual impact [25,29,30,53]. Some studies reported that this increased time at home was associated with higher satisfaction among adolescents regarding their daily interactions with their families [47,53]. However, other research indicated that for some adolescents, the prolonged time spent at home was linked to higher levels of physical and psychological violence from their families [16,33,36]. These negative experiences were often underestimated and adversely affected the emotional well-being of those involved [16,33,36]. Furthermore, economic concerns further exacerbated the situation, as some parents left their in-person work due to fear of transmitting the virus to their children, resulting in worsened economic conditions and increased family tension [27,29,34]. The absence of parental presence at home was linked to worsened psychosocial well-being among adolescents, highlighting the complex dynamics that emerged during this period [39].

Isolation from society, including extended family and friends, contributed to increased psychological stress within the core family [39]. Adolescents faced the added challenge of stigma associated with their underlying conditions, such as cystic fibrosis, mainly due to the association between its symptoms and the symptoms of COVID-19 [44]. This led to increased stress for both parents and adolescents. In this context, social support from external networks was limited, and the disruption to social norms caused by the pandemic had a significant psychological and emotional impact on these adolescents [33,44].

(b) Educational adaptations and the use of technology: In addressing these challenges, remote learning emerged as an alternative to continuing education. Interestingly, adolescents adapted well to the transition to the online environment, benefiting their psychosocial functioning through social media connections [39,47,51,53]. However, concerns regarding the quality of education and safety in traditional settings persisted, contributing to resistance toward returning to in-person learning [26,33,34].

(c) Psychological and emotional changes: The psychological and emotional repercussions of social isolation were multifaceted. As it reduced their fear of being infected with COVID-19, contributing to making adolescents with chronic diseases less psychologically affected than their health peers [36,39,40,52,56], it also led to adverse effects such as increased sedentary behavior, anxiety, and stress [16,27,41,50,52,54]. The pandemic created uncertainty about the future, mainly due to the lack of information regarding its effects on chronic disease, jeopardizing financial and educational matters [33,38,47]. Mental health and overall quality of life of this population were also affected, with a noted gender difference in these experiences throughout the pandemic, with girls being more affected than boys [33,37,38,39,56].

3.2.2. Category 2—Chasing for the Best Decision: Following Up on the Chronic Disease While Fighting the COVID-19 Pandemic

Three subcategories compose this category: (a) Influence of socioeconomic status on access to health services, (b) Changes in lifestyle habits and their consequences, and (c) New usual care routine related to chronic diseases.

(a) Influence of socioeconomic status on access to health services: The COVID-19 pandemic profoundly impacted healthcare services available to adolescents, particularly those from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds [24]. Adolescents relying solely on public healthcare services faced exacerbated challenges in managing chronic diseases due to the reallocation of resources to attend to emergent populations during COVID-19 [24,34]. Access to vital healthcare resources, including continuous monitoring devices for diabetes, became limited, resulting in worsened disease control and symptoms [29,45]. Conversely, adolescents with private medical–hospital insurance experienced improved disease management through telemedicine and maintained access to control devices, leading to better outcomes [24,28,29,32,41,49].

(b) New care routine related to chronic diseases: The pandemic’s disruptive effects extended beyond healthcare services and entered adolescents’ daily lives. Socioeconomic vulnerabilities, such as housing insecurity and income instability, impeded their capacity to manage chronic diseases effectively [28,29,43,49]. Fears of contracting COVID-19 deterred adolescents and their families from seeking in-person medical follow-up, leading to decreased healthcare continuity [26,51]. Misinformation about COVID-19 and its interaction with specific medications for the usual treatment of the chronic disease led some adolescents to discontinue their treatments [26,27].

Adolescents who had parental supervision at home supporting the disease management adhered more readily to treatment due to the maintenance or increase in monitoring of signs and symptoms [24,25,29,30,43,46,48,53,54]. Adolescents’ belief that chronic diseases could be a risk factor for a worse COVID-19 prognosis also contributed to better disease control [30]. On the other hand, routine for chronic disease control, such as monitoring and testing frequency, worsened when adolescents self-managed their care without parental supervision [28,32,37,45].

(c) Changes in lifestyle habits and their consequences: The adoption of self-management practices emerged as a potential solution to control chronic diseases, improving adherence to treatment and overall health [42,52,54,55]. Maintaining physical activity levels, practicing healthy nutrition, including participating in home-cooked meals, and adapting to new routines were crucial in promoting well-being [15,30,39,40,45,46,53,54]. However, prolonged isolation had adverse effects on lifestyle habits, leading to changes in sleep patterns, increased sedentary behavior, changes in eating patterns, and even the emergence of eating disorders [15,27,28,32,35,38,39,52,54]. There was a notable reduction in physical activity among adolescents with chronic diseases, who demonstrated poorer physical health compared to healthy peers [14]. Adolescents adapted to some COVID-19 prevention measures, such as frequent handwashing [27,34,44,51,52], while encountering difficulties with others, like using hand sanitizers and masks, particularly those with chronic skin conditions [26,34].

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases are represented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representation of the impact of the pandemic on the daily life of adolescents with chronic illnesses (Source: Authors) [color reproduction on the web].

4. Discussion

This review explored the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases. Constrained in their homes due to social isolation, adolescents transformed their living spaces into new worlds. Within these households, fundamental needs such as social interaction, mental and physical well-being, and financial stability became closely intertwined with family needs. In this context, families expanded their protective role against the pandemic’s dangers. Adolescents and families had the opportunity to collaborate toward common goals during these challenging times, finding new solutions and making adjustments that acted as windows to navigate this new reality. However, if there was an imbalance between the needs of the family and the adolescent, the stability of this new world could be compromised, leading to potential setbacks.

The studies included were developed all over the world, illustrating the global impact of the pandemic. However, there was relatively limited evidence from Asia, Africa, and Oceania, which may be attributed to lower-income countries’ restrictions on research development, mainly COVID-19 and its impact on people with chronic diseases [57,58,59].

The results of this review show a strengthening of family bonds due to social isolation. Through greater parental vigilance, adolescents adopted healthy lifestyle habits, such as cooking and starting physical exercises at home, which benefited chronic disease control. However, the separation from their peers and the family tensions resulting from this increased coexistence aroused feelings of loneliness and insecurities linked to the vulnerabilities of their chronic disease. Similarly, scientific evidence in different contexts suggests that increased coexistence between the adolescent and the family established a new family dynamic that supported relationships and alliances between family members and presented a willingness for more effective communication [43].

The fear of coronavirus infection among this population was also shown in our results as impacting family dynamics and social relationships. In this context, family isolation acts as a protection mechanism. The consistent presence of caregivers at home during the pandemic has also proven to facilitate the control of chronic disease symptoms, mainly due to the positive change in adolescents’ habits. Despite being evident during the pandemic, social isolation is already a frequent topic in studies with families of people diagnosed with chronic diseases, as caring for their loved ones becomes a priority of daily living [60,61]. In family functioning, activities and routines such as eating, sleeping, and working are present in the lives of these families [42]. The diagnosis of chronic disease in the family and the new care routine significantly influence their daily activities [60,61].

The literature indicates that the unexpected disruption of the family routine caused by the pandemic can lead to increased stress for caregivers, mainly due to the interruption of work and the added responsibilities of other family members [57,62]. Our results indicated that concerns regarding chronic diseases and the fear of contamination by the coronavirus were triggers to isolation, becoming central daily concerns. The family increased control over the adolescents and their routines as a protection mechanism. Although it benefits health, excessive control contributes to increased interfamily stress. The family financial burden was another critical factor for the stress intensification in family relationships found in our study. These results may be associated with the observed global trend of a significant increase in unemployment rates, mainly due to the closure of companies during the most critical phase of COVID-19 transmission [63,64]. Furthermore, the loss of support from the extended family in care due to isolation and the performance of new roles in the family routine, including educational support, also makes sense for the increased negative feelings [65,66].

As found in our review, in addition to losing their jobs, many guardians chose to move away from the in-person work environment to avoid bringing the disease to their children. Other studies developed with the adult population showed a higher incidence of mental health-related problems throughout the pandemic period [67], significantly among patients whose economic conditions deteriorated. The loss of their caregivers’ jobs was the main factor, and those who faced hunger experienced higher levels of sadness or hopelessness [67]. This fact was also observed in a German study [68], in which the impact of the failing socioeconomic status affected their access to quality health services [64,68]. Thus, the need to choose between leaving their jobs to protect and care for the patient and the financial needs of families represents a continuous and essential decision-making process faced by families [61,62].

These changes and decisions were also found in our results, consolidating the scientific evidence that legitimizes the significant impact of the pandemic on increasing fear and distress among adolescents. While existing literature indicates that parents of adolescents in a typical chronic disease diagnosis process face increased psychological distress [69], our results showed that in the population included, some families may have found it easier to manage mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to individuals without chronic diseases. The higher resilience of those families may justify this fact [61,70], developed by the adjustments in the family routine and family sacrifices, such as changes in employment status and the need for frequent medical follow-up, which families have known since the disease’s diagnosis [60,62].

Other differences were observed between healthy and diagnosed adolescents. The way adolescents with chronic diseases coped with the new routine, for example, was sometimes harmful. Two distinct contexts were experienced: the ability to overcome challenges through adaptations or the difficulty in overcoming the changes imposed by the new routine. Successful adaptations were represented by the excellent use of technologies in online teaching and health care modalities. Its use, however, also depended on the resources available to each family nucleus. Such resources were understood as material resources and systems of communication, organization, and family beliefs. These factors were also crucial in other contexts, including family systems, directly influencing their ability to deal with new challenges and barriers [61,69].

The difficulties in adapting were primarily related to stress, which made it difficult to reestablish the equilibrium of the family system and identify their feelings and experiences. Some of the studies in this review pointed to a distance between the teenager and the family resulting from this difficulty. The lack of supervision regarding the care and lifestyle of adolescents was one of the main consequences of these conflicts. The increase in interfamily violence reported in our results also caused harm to the well-being and health of this population. These barriers may be justified by the changes brought about by the COVID-19 period, which reinforced an already deficient pattern of interactions, making it increasingly difficult for adolescents to feel understood within their needs [69,71]. Such negative aspects are also closely related to social isolation, influencing and being influenced by the economic, social, and psychological consequences discussed previously [64,65]. This dynamic emphasizes the relationship between the adolescent and the family involved in the disease process, affecting the family’s functioning and ability to deal with challenges [72].

Thus, through the synthesis of the studies found, it was evident that the presence of the family was perceived as a critical element for the pandemic impact on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases. Parental surveillance was a protective factor for adopting healthier lifestyle habits and, consequently, adopting adaptations that allowed for maintaining and improving health conditions.

We could also identify both the strengths and limitations of our study. Notably, our investigation is a unique contribution to the literature, being up-to-date and offering a multi-faceted view of the various impacts of the pandemic on different aspects of the daily lives of adolescents with chronic illnesses, with no restrictions placed on their specific diagnosis. However, it is essential to acknowledge several limitations. Firstly, our focus was not on understanding mental health aspects, which is why related terms were not included in our search strategy. We recognize that this may have limited the comprehensiveness of our search. Additionally, the search was restricted to studies published in Spanish, English, and Portuguese, potentially excluding relevant research published in other languages. Nevertheless, this review was able to capture studies conducted in different countries. Although the original studies did not delve into the cultural and health contexts of the respective countries where they were conducted, it is important to highlight that the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the daily lives of adolescents with chronic diseases was influenced by the varying healthcare systems. Another notable limitation is that the majority of studies included in our review focused on adolescents with diabetes mellitus, with 17 out of 35 studies examining this particular condition. This highlights a significant gap in the research regarding other chronic diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, cancer, and heart/kidney diseases, which also affect adolescents and were impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic but have been less extensively studied.

4.1. Practical Implications

This study outlines challenges adolescents with chronic illnesses faced during the pandemic, including routine changes, healthcare access, and emotional well-being. Given the significant impact on psychological and emotional health identified in our findings, it is essential to prioritize the expansion of mental health services in response to future health crises. Enhancing access to psychological care can play a crucial role in alleviating the emotional strain experienced by these adolescents. These findings can guide professionals in supporting this population by identifying key areas of support and strategically allocating resources across diverse socioeconomic contexts.

4.2. Implications for Future Research

Future research should specifically focus on the dimensions of “psychosocial and emotional aspects” to gain a more nuanced understanding of these critical factors. By incorporating these elements into research strategies, studies can provide deeper insights into the mental health challenges faced by adolescents with chronic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. This targeted approach will enhance our understanding of the full impact of the pandemic on this vulnerable population and inform more effective interventions and support mechanisms. Additionally, future studies should also aim to explore how disparities in access and outcomes of healthcare services that already existed between people of color and white individuals were exacerbated by the pandemic. Addressing this gap could provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing health inequalities and guide strategies to mitigate such disparities in future public health crises.

5. Conclusions

The study explored how the COVID-19 pandemic affected adolescents with chronic diseases, highlighting its global implications. Due to social isolation, family bonds were strengthened, leading to healthier habits and better disease control through parental vigilance. However, separation from peers caused loneliness and insecurity, exacerbating their vulnerabilities. Increased family cohesion improved communication but also heightened concerns about coronavirus infection. Being isolated was a protective mechanism, but it also contributed to increased interfamily stress and financial burdens. Adolescents faced more significant stress due to disrupted routines and economic strain, which impacted family dynamics. Despite these challenges, the ability to adapt to changes and prioritize mental health contributed to their resilience. Successful adaptation depended on available resources and family beliefs. Overall, the study emphasizes the crucial role of family support in mitigating the pandemic’s impact on adolescents with chronic diseases, highlighting the importance of parental supervision in fostering healthier lifestyles and coping mechanisms. Moving forward, addressing the unique needs of adolescents with chronic illnesses during crises is crucial to guiding practice and conversations with this population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children11091047/s1, Supplementary File S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S. and L.C.N.; methodology, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L., R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A. and L.C.N.; software, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S. and M.d.L.; validation, R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A., P.S.D.B., M.H.P. and L.C.N.; formal analysis, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L., R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A., M.H.P. and L.C.N.; investigation, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L., R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A., M.H.P. and L.C.N.; resources, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L., R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A., M.H.P. and L.C.N.; data curation, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L., R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A., M.H.P. and L.C.N.; writing—original draft preparation, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L. and L.C.N.; writing—review and editing, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L., R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A., M.H.P. and L.C.N.; visualization, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S., M.d.L., R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A., M.H.P. and L.C.N.; supervision, R.R.N., A.C.A.B.L., W.d.A.A. and L.C.N.; project administration, G.C.M.-K., M.d.L. and L.C.N.; funding acquisition, G.C.M.-K., I.H.S. and L.C.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brazil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001 and the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), Brazil, Process No. 2022-1395.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Jairath, N.N.; Benetato, B.B.; O’Brien, S.L.; Griffin Agazio, J.B. Just-in-Time Qualitative Research: Methodological Guidelines Based on the COVID-19 Pandemic Experience. Nurs. Res. 2021, 70, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkhadry, S.W.; Salem, T.A.E.H.; Elshabrawy, A.; Goda, S.S.; Bahwashy, H.A.A.; Youssef, N.; Hussein, M.; Ghazy, R.M. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy among Parents of Children with Chronic Liver Diseases. Vaccines 2022, 10, 2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, A.M.M. A pandemia exacerbou os relacionamentos ou a solidão. Bol.-Acad. Paul. Psicol. 2020, 40, 192–204. [Google Scholar]

- Krijger, A.; Dulfer, K.; Van Oers, H.; Teela, L.; De Jong-van Kempen, B.; Van Els, A.; Haverman, L.; Joosten, K. Perceived Stress, Family Impact, and Changes in Physical and Social Daily Life Activities of Children with Chronic Somatic Conditions during the COVID-19 Pandemic. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raviv, T.; Warren, C.M.; Washburn, J.J.; Kanaley, M.K.; Eihentale, L.; Goldenthal, H.J.; Russo, J.; Martin, C.P.; Lombard, L.S.; Tully, J.; et al. Caregiver Perceptions of Children’s Psychological Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kompaniyets, L.; Agathis, N.T.; Nelson, J.M.; Preston, L.E.; Ko, J.Y.; Belay, B.; Pennington, A.F.; Danielson, M.L.; DeSisto, C.L.; Chevinsky, J.R.; et al. Underlying Medical Conditions Associated With Severe COVID-19 Illness Among Children. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e2111182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernell, S.; Howard, S.W. Use Your Words Carefully: What Is a Chronic Disease? Front. Public Health 2016, 4, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, J.P.B.; Neves, E.T.; Pitombeira, M.G.V.; Figueiredo, S.V.; Campos, D.B.; Gomes, I.L.V. Continuity of Care for Children with Special Healthcare Needs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2022, 75, e20210150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins-Filho, P.C.; Araújo, M.M.S.D.; Macêdo, T.S.D.; Ferreira, A.K.A.; Melo, M.C.F.D.; Freitas, J.L.D.M.; Silva, E.L.M.S.D.; Caldas, T.U.; Godoy, G.P.; Caldas, A.D.F., Jr. Assessing the Quality, Readability and Reliability of Online Information on COVID-19. RSD 2020, 9, e3591210680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The Adolescent Health Indicators Recommended by the Global Action for Measurement of Adolescent Health, 1st ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 1, ISBN 978-92-4-009219-8.

- Mendes, E.V. O Cuidado Das Condições Crônicas Na Atenção Primária à Saúde: O Imperativo Da Consolidação Da Estratégia Da Saúde Da Família; Organização Pan-Americana da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2012; ISBN 978-85-7967-078-7.

- Nascimento, L.C.; Rocha, S.M.M.; Hayes, V.H.; de Lima, R.A.G. Crianças com câncer e suas famílias. Rev. Esc. Enferm. USP 2005, 39, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neris, R.R.; Bolis, L.O.; Leite, A.C.A.B.; Alvarenga, W.D.A.; Garcia-Vivar, C.; Nascimento, L.C. Functioning of Structurally Diverse Families Living with Adolescents and Children with Chronic Disease: A Metasynthesis. J Nurs. Scholarsh. 2023, 55, 413–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, W.A.D.; Silva, J.L.D.; Andrade, A.L.M.; Micheli, D.D.; Carlos, D.M.; Silva, M.A.I. A Saúde Do Adolescente Em Tempos Da COVID-19: Scoping Review. Cad. Saúde Pública 2020, 36, e00150020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzolani, B.C.; Smaira, F.I.; Astley, C.; Iraha, A.Y.; Pinto, A.J.; Marques, I.G.; Cordeiro Amarante, M.; Rezende, N.S.; Sieczkowska, S.M.; Franco, T.C.; et al. Changes in Eating Habits and Sedentary Behavior During the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents With Chronic Conditions. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 714120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, R.T.; Lindoso, L.; Sousa, R.A.D.; Helito, A.C.; Ihara, B.P.; Strabelli, C.A.A.; Paradelas, L.M.V.; Carneiro, B.O.L.; Cardoso, M.P.R.; Souza, J.P.V.D.; et al. Emotional, Hyperactivity and Inattention Problems in Adolescents with Immunocompromising Chronic Diseases during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Clinics 2023, 78, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, D.; Davies, E.L.; Peters, M.D.J.; Tricco, A.C.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H.; Munn, Z. Undertaking a Scoping Review: A Practical Guide for Nursing and Midwifery Students, Clinicians, Researchers, and Academics. J. Adv. Nurs. 2021, 77, 2102–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, H.; Peters, M.; Godfrey, C.M.; McInerney, P.; Soares, C.B.; Parker, D. An Evidence-Based Approach to Scoping Reviews. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2016, 13, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOV.BR. Plano de Ações Estratégicas Para o Enfrentamento Das Doenças Crônicas Não Transmissíveis (DCNT) No Brasil: 2011–2022, 1st ed.; Brazil, Edition, Série B. Textos Básicos de Saúde; Ministério da Saúde: Brasília, Brazil, 2011; ISBN 978-85-334-1831-8.

- Viera, A.J.; Garrett, J.M. Understanding interobserver agreement: The kappa statistic. Fam. Med. 2005, 37, 360–363. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhussein, F.S.; Chesser, H.; Boscardin, W.J.; Gitelman, S.E.; Wong, J.C. Youth with Type 1 Diabetes Had Improvement in Continuous Glucose Monitoring Metrics During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Diabetes Technol. Ther. 2021, 23, 684–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, N.B.; Unsal, Y.; Canoruc Emet, D.; Mete Yesil, A.; Sencan, B.; Gonc, E.N.; Ozon, Z.A.; Ozmert, E.N.; Alikasifoglu, A. Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children with Congenital Adrenal Hyperplasia and Their Families. Turk. Arch. Pediatr. 2022, 57, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beytout, Q.; Pepiot, J.; Maruani, A.; Devulder, D.; Aubert, R.; Beylot-Barry, M.; Amici, J.-M.; Jullien, D.; Mahé, E. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Children with Psoriasis. Ann. Dermatol. Vénéréologie 2021, 148, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cekic, S.; Karali, Z.; Cicek, F.; Canitez, Y.; Sapan, N. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Adolescents with Asthma. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, H.P.; Wong, J.S.L.; Selveindran, N.M.; Hong, J.Y.H. Impact of COVID-19 Lockdown on Glycaemic Control and Lifestyle Changes in Children and Adolescents with Type 1 and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Endocrine 2021, 73, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Adhikari, S.; White, P.C. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Management of Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes. BMC Pediatr. 2022, 22, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusinato, M.; Martino, M.; Sartori, A.; Gabrielli, C.; Tassara, L.; Debertolis, G.; Righetto, E.; Moretti, C. Anxiety, Depression, and Glycemic Control during Covid-19 Pandemic in Youths with Type 1 Diabetes. J. Pediatr. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 34, 1089–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorfman, L.; Nassar, R.; Binjamin Ohana, D.; Oseran, I.; Matar, M.; Shamir, R.; Assa, A. Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease and the Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on Treatment Adherence and Patients’ Behavior. Pediatr. Res. 2021, 90, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhenawy, Y.I.; Eltonbary, K.Y. Glycemic Control among Children and Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes during COVID-19 Pandemic in Egypt: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Diabetes Dev. Ctries. 2021, 41, 389–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedele, F.; Martinelli, M.; Strisciuglio, C.; Dolce, P.; Giugliano, F.P.; Scarpato, E.; Staiano, A.; Miele, E. Health-Related Quality of Life in Pediatric Inflammatory Bowel Disease During COVID-19 Pandemic: A Prospective Study. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2022, 75, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, M.A.; Meyer, S.B.; Yessis, J.; Reaume, S.V.; Lipman, E.; Gorter, J.W. COVID-19-Related Psychological and Psychosocial Distress Among Parents and Youth With Physical Illness: A Longitudinal Study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 761968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gillon-Keren, M.; Propper-Lewinsohn, T.; David, M.; Liberman, A.; Phillip, M.; Oron, T. Exacerbation of Disordered Eating Behaviors in Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acta Diabetol. 2022, 59, 981–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helito, A.C.; Lindoso, L.; Sieczkowska, S.M.; Astley, C.; Queiroz, L.B.; Rose, N.; Santos, C.R.P.; Bolzan, T.; Peralta, R.M.I.A.; Franco, R.R.; et al. Poor Sleep Quality and Health-Related Quality of Life Impact in Adolescents with and without Chronic Immunosuppressive Conditions during COVID-19 Quarantine. Clinics 2021, 76, e3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoefnagels, J.W.; Schoen, A.B.; Van Der Laan, S.E.I.; Rodijk, L.H.; Van Der Ent, C.K.; Van De Putte, E.M.; Dalmeijer, G.W.; Nijhof, S.L. The Impact of the COVID-19 Outbreak on Mental Wellbeing in Children with a Chronic Condition Compared to Healthy Peers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaatmaca, B.; Selmanoğlu, A.; Toyran, M.; Emeksiz, Z.Ş.; Şenses Dinç, G.; Öden Akman, A.; Çöp, E.; Civelek, E.; Üneri, Ö.Ş.; Dibek Mısırlıoğlu, E. Quality of Life and the Psychological Status of the Adolescents with Asthma and Their Parents during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2022, 64, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindoso, L.; Astley, C.; Queiroz, L.B.; Gualano, B.; Pereira, R.M.R.; Tannuri, U.; Campos, L.M.M.D.A.; Lourenço, B.; Toma, R.K.; Medeiros, K.; et al. Physical and Mental Health Impacts during COVID-19 Quarantine in Adolescents with Preexisting Chronic Immunocompromised Conditions. J. Pediatr. 2022, 98, 350–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.M.; Stephens, S.; Ciftci-Kavaklioglu, B.; Berenbaum, T.; Ly, M.; Longoni, G.; Yeh, E.A. Pandemic-Associated Mental Health Changes in Youth with Neuroinflammatory Disorders. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2022, 58, 103468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mianowska, B.; Fedorczak, A.; Michalak, A.; Pokora, W.; Barańska-Nowicka, I.; Wilczyńska, M.; Szadkowska, A. Diabetes Related Distress in Children with Type 1 Diabetes before and during the COVID-19 Lockdown in Spring 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, A.L.; Albright, D.; Bauer, K.W.; Riley, H.O.; Hilliard, M.E.; Sturza, J.; Kaciroti, N.; Lo, S.L.; Clark, K.M.; Lee, J.M.; et al. Self-Regulation as a Protective Factor for Diabetes Distress and Adherence in Youth with Type 1 Diabetes During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2022, 47, 873–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passanisi, S.; Pecoraro, M.; Pira, F.; Alibrandi, A.; Donia, V.; Lonia, P.; Pajno, G.B.; Salzano, G.; Lombardo, F. Quarantine Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic From the Perspective of Pediatric Patients With Type 1 Diabetes: A Web-Based Survey. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, L.; Mirlashari, J.; Modaresi, M.; Pederson, A. Cough in Adolescent with Cystic Fibrosis, from Nightmare to COVID-19 Stigma: A Qualitative Thematic Analysis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 64, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telford, D.M.; Signal, D.M.; Hofman, P.L.; Gusso, S. Physical Activity in Adolescents with and without Type 1 Diabetes during the New Zealand COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown of 2020. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Troncone, A.; Chianese, A.; Cascella, C.; Zanfardino, A.; Piscopo, A.; Rollato, S.; Iafusco, D. Eating Problems in Youths with Type 1 Diabetes During and After Lockdown in Italy: An 8-Month Follow-Up Study. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2023, 30, 227–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanaz, M.; Yilmaz Yegit, C.; Ergenekon, A.P.; Toksoy Aksoy, A.; Bilicen, G.; Gokdemir, Y.; Erdem Eralp, E.; Rodopman Arman, A.; Karakoc, F.; Karadag, B. The Effect of Coronavirus Disease 2019 on Anxiety Levels of Children with Cystic Fibrosis and Healthy Peers. Pediatr. Int. 2022, 64, e15009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Dalmazi, G.; Maltoni, G.; Bongiorno, C.; Tucci, L.; Di Natale, V.; Moscatiello, S.; Laffi, G.; Pession, A.; Zucchini, S.; Pagotto, U. Comparison of the Effects of Lockdown Due to COVID-19 on Glucose Patterns among Children, Adolescents, and Adults with Type 1 Diabetes: CGM Study. BMJ Open Diab. Res. Care 2020, 8, e001664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Ryan, N.P.; Byrne, L.K.; Hendrieckx, C.; White, V. Psychological Distress Among Parents of Children With Chronic Health Conditions and Its Association With Unmet Supportive Care Needs and Children’s Quality of Life. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2023, 49, jsad074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noij, L.; Haarman, E.; Hashimoto, S.; Terheggen-Lagro, S.; Altenburg, J.; Twisk, J.; Verkleij, M. Depression, Anxiety, and Resilience during COVID-19 in Dutch Patients with Cystic Fibrosis or Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia and Their Caregivers. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2023, 58, 2025–2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucchetti, G.; Quarello, P.; Ferrari, A.; Silva, M.; Mercolini, F.; Sciarra, P.; Guido, A.; Peruzzi, L.; Colavero, P.; Montanaro, M.; et al. How Did Adolescents With Cancer Experience the COVID-19 Pandemic? A Report From Italian Pediatric Hematology Oncology Association Centers. J. Pediatr. Hematol./Oncol. 2023, 45, e683–e688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovira-Remisa, M.M.; Moreira, M.; Ventura, P.S.; Gonzalez-Alvarez, P.; Mestres, N.; Graterol Torres, F.; Joaquín, C.; Seuma, A.R.-P.; Del Mar Martínez-Colls, M.; Roche, A.; et al. Impact of COVID19 Pandemic on Patients with Rare Diseases in Spain, with a Special Focus on Inherited Metabolic Diseases. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2023, 35, 100962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremolada, M.; Cusinato, M.; D’Agnillo, A.; Negri, A.; Righetto, E.; Moretti, C. “One and a Half Years of Things We Could Have Done”: Multi-Method Analysis of the Narratives of Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiler, M.; Wittek, T.; Graf, T.; Bozic, I.; Nitsch, M.; Waldherr, K.; Karwautz, A.; Wagner, G.; Berger, G. Psychosocial Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Adolescents with Type-1-Diabetes: A Qualitative Interview Study Involving Adolescents and Parents. Behav. Med. 2023, 49, 412–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collins, C.M.; Céspedes, A.; Diggs, K.A.; Liu, J.; Bruzzese, J.-M. Adolescent Views on Asthma Severity and Management During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. Pulmonol. 2023, 36, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Framme, J.R.; Kim-Dorner, S.-J.; Heidtmann, B.; Kapellen, T.M.; Lange, K.; Kordonouri, O.; Saßmann, H. Health-Related Quality of Life among Adolescents with Type 1 Diabetes since the Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic in Germany. Fam. Med. Community Health 2023, 11, e002415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiquea, B.N.; Shetty, A.; Bhattacharya, O.; Afroz, A.; Billah, B. Global Epidemiology of COVID-19 Knowledge, Attitude and Practice: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e051447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, F. Ignorance, Orientalism and Sinophobia in Knowledge Production on COVID-19. Tijdschr. Voor Econ. En Soc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, V.H.A.; Caroci-Becker, A.; Venâncio, K.C.M.P.; Baraldi, N.G.; Durkin, A.C.; Riesco, M.L.G. COVID-19 and the Production of Knowledge Regarding Recommendations during Pregnancy: A Scoping Review. Rev. Lat.-Am. Enferm. 2020, 28, e3348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robison, J.; Fortinsky, R.; Kleppinger, A.; Shugrue, N.; Porter, M. A Broader View of Family Caregiving: Effects of Caregiving and Caregiver Conditions on Depressive Symptoms, Health, Work, and Social Isolation. J. Gerontol. Ser. B Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 2009, 64B, 788–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L.M.; Leahey, M. Nurses and Families: A Guide to Family Assessment and Intervention, 6th ed.; F.A. Davis: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-8036-2739-0. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrabissa, G.; Volpi, C.; Bottacchi, M.; Bertuzzi, V.; Guerrini Usubini, A.; Löffler-Stastka, H.; Prevendar, T.; Rapelli, G.; Cattivelli, R.; Castelnuovo, G.; et al. The Impact of Social Isolation during the COVID-19 Pandemic on Physical and Mental Health: The Lived Experience of Adolescents with Obesity and Their Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public health 2021, 18, 3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, G.L.; Lopez-Olivo, M.A.; Advani, P.G.; Ning, M.S.; Geng, Y.; Giordano, S.H.; Volk, R.J. Financial Burdens of Cancer Treatment: A Systematic Review of Risk Factors and Outcomes. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2019, 17, 1184–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDowell, C.P.; Herring, M.P.; Lansing, J.; Brower, C.; Meyer, J.D. Working From Home and Job Loss Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic Are Associated With Greater Time in Sedentary Behaviors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 597619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fegert, J.M.; Vitiello, B.; Plener, P.L.; Clemens, V. Challenges and Burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic for Child and Adolescent Mental Health: A Narrative Review to Highlight Clinical and Research Needs in the Acute Phase and the Long Return to Normality. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2020, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, L.V.D.S.; Calandri, I.L.; Slachevsky, A.; Graviotto, H.G.; Vieira, M.C.S.; Andrade, C.B.D.; Rossetti, A.P.; Generoso, A.B.; Carmona, K.C.; Pinto, L.A.C.; et al. Impact of Social Isolation on People with Dementia and Their Family Caregivers. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2021, 81, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.E.; Hertz, M.F.; DeGue, S.A.; Merlo, C.L.; Piepenbrink, R.P.; Le, V.D.; Dittus, P.J.; Houston, A.L.; Thornton, J.E.; Ethier, K.A. Family Economics and Mental Health Among High-School Students During COVID-19. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 64, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geweniger, A.; Barth, M.; Haddad, A.D.; Högl, H.; Insan, S.; Mund, A.; Langer, T. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health Outcomes of Healthy Children, Children With Special Health Care Needs and Their Caregivers–Results of a Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Pediatr. 2022, 10, 759066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prime, H.; Wade, M.; Browne, D.T. Risk and Resilience in Family Well-Being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am. Psychol. 2020, 75, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Chen, M.; Jiang, H.; Ren, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Dong, C. The Resilient Process of the Family after Diagnosis of Childhood Chronic Illness: A Qualitative Meta-Synthesis. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2022, 67, e180–e190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balenzano, C.; Moro, G.; Girardi, S. Families in the Pandemic Between Challenges and Opportunities: An Empirical Study of Parents with Preschool and School-Age Children. Ital. Sociol. Rev. 2020, 10, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usher, K.; Bhullar, N.; Durkin, J.; Gyamfi, N.; Jackson, D. Family Violence and COVID-19: Increased Vulnerability and Reduced Options for Support. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 549–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).