Abstract

Background: Pediatric regional anesthesia has been driven by the gradual rise in the adoption of opioid-sparing strategies and the growing concern over the possible adverse effects of general anesthetics on neurodevelopment. Nonetheless, performing regional anesthesia studies in a pediatric population is challenging and accounts for the scarce evidence. This study aimed to review the scientific foundation of studies in cadavers to assess regional anesthesia techniques in children. Methods: We searched the following databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Web of Science. We included anatomical cadaver studies assessing peripheral nerve blocks in children. The core data collected from studies were included in tables and comprised block type, block evaluation, results, and conclusion. Results: The search identified 2409 studies, of which, 16 were anatomical studies on the pediatric population. The techniques evaluated were the erector spinae plane block, ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block, sciatic nerve block, maxillary nerve block, paravertebral block, femoral nerve block, radial nerve block, greater occipital nerve block, infraclavicular brachial plexus block, and infraorbital nerve block. Conclusion: Regional anesthesia techniques are commonly performed in children, but the lack of anatomical studies may result in reservations regarding the dispersion and absorption of local anesthetics. Further anatomical research on pediatric regional anesthesia may guide the practice.

1. Introduction

Regional anesthesia in pediatric anesthesia has gradually grown due to the widespread use of multimodal and opioid-sparing analgesia [1,2]. The recent concern over the potentially harmful effects of general anesthetics on neurodevelopment has further contributed to pediatric regional anesthesia development [3].

Although the Bier technique has been described in children since 1899 [4], and peripheral nerve blocks have been reported since 1963 in the pediatric population by Taylor et al. [5], there are few clinical pediatric studies due to the inherent challenges associated with performing clinical studies in this population [6,7].

The Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network has been investigating the practice, risks, and incidence of complications since 2007. According to the data presented, pediatric regional anesthesia is a safe practice with a relatively low risk of complications [8,9,10]. In contrast to the many anatomical studies developed in adults with a focus on regional anesthesia, studies on pediatric cadavers are still scarce.

This scoping review aims to create a descriptive summary of the included studies and identify gaps in the literature on anatomical studies in pediatric cadavers used to evaluate regional anesthesia techniques.

This review was based on the following research questions: Are there anatomical studies of peripheral nerve blocks in the pediatric population? Based on the studies published in cadavers, what is the existing evidence of anatomic studies for pediatric regional anesthesia techniques?

2. Methods

This scoping review strictly adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR, Table S1) [11]. The review protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework: https://osf.io/p3u6h/ accessed on 4 April 2024.

The systematic search strategy was performed on the following databases: MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, and Web of Science. Additionally, we manually searched the list of references of the articles selected. We used multiple combinations of the following MeSH terms: “Anatomy, Regional”, “Cadaver”, and “Nerve Block”. The complete search strategies are provided in the Table S2.

Following the PICOs strategy, our study’s target population was pediatric cadavers (under 18 years of age), who had undergone peripheral regional blocks which were analyzed during anatomical studies to assess the dispersion of the injected solutions and/or the anatomy of each particular block. There was no comparison group.

2.1. Selection of Studies

The studies considered eligible for inclusion in this scoping review were human anatomical studies evaluating any type of peripheral block in the pediatric population, including zero to 18 years of age. Central neuraxial block studies were not included, as well as studies in other species and articles without full text available, with no publication date, or in a language different from English. The reference lists of articles included in the review were screened for additional papers.

All identified records were uploaded to EndNote v.20 software (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA), and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by two independent reviewers (L.F.G.P. and V.C.Q.) to assess whether they met the inclusion criteria for the review.

Relevant papers were retrieved, and their citation details were uploaded into Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar). Full-text studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded, and any disagreements between reviewers were resolved through discussion or with a third reviewer (R.V.C.).

2.2. Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers (L.F.G.P. and V.C.Q.) used a data extraction tool developed by the reviewers (Table S3) to extract the summarized data from papers included in the scoping review. The data extracted included specific details about the year of the publication, the population studied, the block studied, cadaver characteristics, the block assessment, and the results relevant to the review question.

Any reviewer disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (R.V.C.). Where required, authors of papers were contacted by the contact email to request missing data.

2.3. Data Analysis and Presentation

The data collected from the selected studies were divided into two tables containing the primary data with the most significant emphasis on the block studied and how the block was assessed. Data were extracted from selected studies to an extraction chart, and the following information was included in the tables: publication year, name of authors, country where the study was performed, anesthesia block investigated, population, cadaver characteristics, block evaluation, results, and conclusion.

2.4. Secondary Analysis

As observed during the study selection phase, many anatomical studies related to anesthetic blocks were found in other populations and species. This interesting fact yielded a further analysis for this review, which will be presented as an infographic.

3. Results

3.1. Search

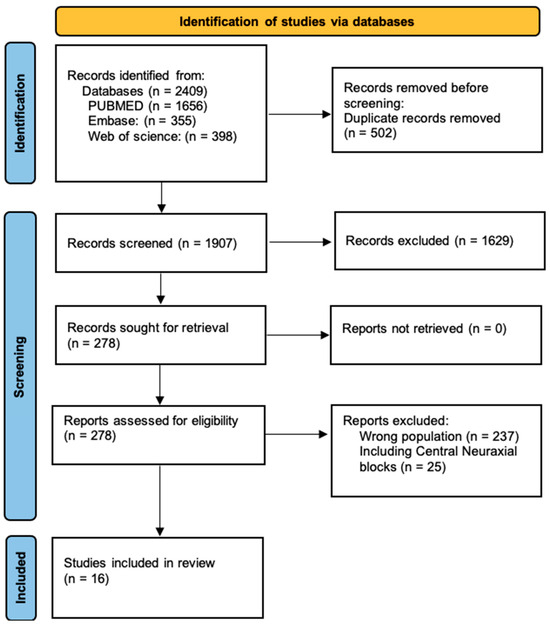

The systematic database search found 2409 studies. After removing 502 duplicates, 1907 studies were screened based on the title and abstract, and 1629 manuscripts were excluded. The full texts of 278 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 262 were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were 237 studies with the wrong population and 25 studies including central neuraxial blocks in the anatomical studies. A total of 16 studies were included in the review, and the study selection process is illustrated in the PRISMA flowchart diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for the present scoping review.

The studies selected were published between 1995 and 2024. The types of blocks in the studies were erector spinae plane blocks [12,13,14], ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve blocks [15,16], sciatic nerve blocks [17,18], maxillary nerve blocks [19], paravertebral blocks [20], femoral nerve blocks [21], radial nerve blocks [22], greater occipital nerve blocks [23,24], infraclavicular brachial plexus blocks [25], infraorbital nerve blocks [26], and dorsal penile nerve blocks [27].

The included studies were published in nine different journals, with the journal with the highest number of publications being Pediatric Anesthesia, which published six studies in total.

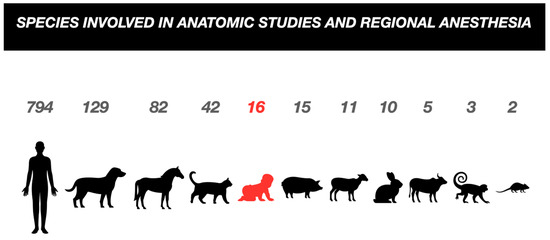

As part of a secondary analysis during the selection of studies, we compared regional anesthesia anatomical studies in different populations. As a result, adult humans comprised the studied population with the highest number of studies, 794 articles, followed by studies in dogs, horses, and cats, and only then in the pediatric human population. The data found in the search are summarized in the infographic below (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Infographic comparing the studied species, with the pediatric population highlighted in red.

Our comparison-based selection resulted in few studies in the pediatric population, probably due to the challenges inherent to performing research involving this population.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 1 and Table 2 depict and summarize the data collected in the studies. Table 1 describes the studies according to the population studied in the publications included in the scoping review.

Table 1.

Study characteristics according to population.

Table 2.

Assessment of the anesthesia block, results, and conclusions for each study included in the review.

Table 2 summarizes the assessment performed for each anesthesia block, results, and conclusions from the studies included.

4. Discussion

This scoping review analyzed regional anesthesia using cadavers in the pediatric population. Acknowledging how the topic has already been studied, which conclusions were consistent, and the existing knowledge gaps in the pediatric population are essential to the progress of pediatric regional anesthesia research.

When it comes to pediatric anesthesia, a committee with the council and board of the pediatric anesthesia societies of the United Kingdom, Ireland, New Zealand, and Australia chose pediatric regional anesthesia as the second main topic of interest for new research. And new discoveries for this population should not be based on the concept of children being “little adults” [28,29]. The differences in regional anesthesia between these populations are profound, from the anatomy that varies according to the age of the patient and the thinner muscles, fascia, and connective tissues compared to adults, to questions of pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics [29].

The subject was primarily studied through the performance of anatomical measurements (12 studies out of the 16 included) rather than the actual simulated performance of blocks in cadavers. Studies with block simulations investigated interfascial block techniques (erector spinae plane and paravertebral blocks), and in most of the studies, the dispersion was recorded and correlated with the injected volume [12,13,14,20].

In studies that aimed to simulate the block’s performance, injected solution dispersion was assessed through imaging such as a CT scan [14] or even ultrasonography [13]. Along with imaging tests, solution dispersion was confirmed by dissection after performing blocks.

The peripheral nerve blocks more frequently assessed by anatomical studies in the pediatric population were erector spinae plane block, with three studies included [12,13,14], and ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block [15,16] and greater occipital nerve block [23,24], with two studies included each.

When we analyzed the age of the subjects in the manuscripts in this scoping review, we found that most cadavers were below the first year of life. This age group has anatomical particularities, and there have been few clinical studies on this population due to the developmental stages that are still to come. This may justify the greater interest in research rather than just extrapolating the technique used in adults.

Developing research in vulnerable populations, such as pediatrics, is a challenging task. This can be seen in the fact that 70–90% of the drugs prescribed for this population are used off-label, showing that the lack of data derived from research in children is not limited to the subject of pediatric regional anesthesia but extends to all areas of medicine [30].

Taking into account the years of the publications included, we found a range between 1995 and 2024. We must bear in mind the technological availability of the time, mainly in the evolution of ultrasound and the study of sonoanatomy, both for performing anesthetic blocks and for evaluating the dispersion of the blocks performed.

Considering the conclusions of the selected studies, we realized that they agreed that, due to anatomical and physiological differences between adults and children, it would be inappropriate to extrapolate the findings obtained from an adult sample to the pediatric population.

This study can serve as a basis and guide for new anatomical studies on regional blocks in the pediatric population. In addition, it summarizes the results found in each anatomical study, compressing data on pertinent anatomical details for each block and on the evaluation of block dispersion, especially in studies in which there was simulation during the anatomical study.

After examining the literature, we observed gaps, such as the need to perform studies focusing on peripheral nerve block techniques commonly employed in pediatric patients, such as rectus sheath block and transversus abdominis plane block. There is a need to simulate blocks in anatomical studies to assess nerve block techniques, more accurate imaging tests to assess injected solution dispersion, and the possibility of analysis using Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

The main limitation of our review is the age of the existing anatomical studies, most of which are of the neonatal population. In addition, we could not ensure the state of preservation of the cadavers studied, including premature cadavers, using blocks guided by anatomical landmarks and the heterogeneity of the studies included.

Issues Related to Cadaver Preservation/Preparation

Different cadaver preparation and preservation types can influence the results in anatomical studies. In addition, characteristics of in vivo patients absent from cadavers also influence the evaluation of blocks, especially regarding their dispersion [23].

Such characteristics, which do not allow the cadaver model to mimic the clinical scenario fully, include blood circulation and muscle contraction (important points for diffusion), respiratory and body movement, postmortem turgor, and the concern that the area of dispersion will increase during dissection [31,32].

The temperature at which the cadaver is preserved also interferes with connective tissue viscosity. Hyaluronic acid (a key viscosity component) is susceptible to temperature change and acidosis. Dropping to a pH of 6.6 and decreasing cadaver temperature by 2 °C increases viscosity by up to 20% [31,33].

In addition to hyaluronic acid, the water in the interfascial connective tissue is considerably reduced, leading to high viscosity and resistance to injection in the fascial plane. Such biochemical and biomechanical characteristics may influence the extent and dispersion pattern of the injected solution, especially in interfascial blocks, depending on the type of preservation used [34].

5. Conclusions

Peripheral nerve blocks in pediatric patients are extensively used components of the opioid-sparing strategy. Anatomical studies on the subject are scarce, with a high diversity of studies that can still be developed. There are peripheral blocks that have not yet been addressed by studies on pediatric cadavers, thus providing a good opportunity for research in pediatric anesthesiology.

Most regional anesthesia techniques are based on the extrapolation of data from blocks performed in adults, which presents uncertainties to the practitioner regarding the dispersion and absorption of local anesthetics, toxic doses, and points of needle insertion. Thus, further anatomical studies are required in the pediatric population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children11060733/s1: Table S1: PRISMA-ScR checklist; Table S2: Complete search strategies; Table S3: Data extraction tool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: L.F.G.P. and V.C.Q. Data curation: L.F.G.P. Formal analysis: L.F.G.P. and V.C.Q. Investigation: L.F.G.P., R.V.C., M.J.C.C., A.v.S., A.B., V.C.Q., N.M.S.L., R.d.C.S. and B.d.F.B. Methodology: M.J.C.C. and V.C.Q. Project administration: V.C.Q. Supervision: M.J.C.C. and V.C.Q. Visualization: L.F.G.P. and V.C.Q. Writing—original draft: L.F.G.P., R.V.C., M.J.C.C. and V.C.Q. Writing—review and editing: A.v.S., A.B. and V.C.Q. Final Review—L.F.G.P., N.M.S.L., R.d.C.S. and B.d.F.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Heydinger, G.; Tobias, J.; Veneziano, G. Fundamentals and innovations in regional anaesthesia for infants and children. Anaesthesia 2021, 76 (Suppl. S1), 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendall, M.C.; Alves, L.J.C.; Suh, E.I.; McCormick, Z.L.; De Oliveira, G.S. Regional anesthesia to ameliorate postoperative analgesia outcomes in pediatric surgical patients: An updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Local. Reg. Anesth. 2018, 11, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, J.L.; Paule, M.G. Review of preclinical studies on pediatric general anesthesia-induced developmental neurotoxicity. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2017, 60, 2–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bier, A. Versuche über Cocainisirung des Rückenmarkes. Dtsch. Z. Chir. 1899, 51, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.; Wilson, F.M.; Roesch, R.; Stoelting, V.K. Prevention of the Oculo-Cardiac Reflex in Children. Comparison of Retrobulbar Block and Intravenous Atropine. Anesthesiology 1963, 24, 646–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, S.; Schaldenbrand, K.; Wallis, B.; De Oliveira, G.S., Jr. Regional anaesthesia to improve pain outcomes in paediatric surgical patients: A qualitative systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Br. J. Anaesth. 2014, 113, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S.; De Oliveira, G.S., Jr. Local anaesthetic dosage of peripheral nerve blocks in children: Analysis of 40 121 blocks from the Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network database. Br. J. Anaesth. 2018, 120, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaner, D.M.; Taenzer, A.H.; Walker, B.J.; Bosenberg, A.; Krane, E.J.; Suresh, S.; Wolf, C.; Martin, L.D. Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network (PRAN): A Multi-Institutional Study of the Use and Incidence of Complications of Pediatric Regional Anesthesia. Anesth. Analg. 2012, 115, 1353–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taenzer, A.H.; Herrick, M.; Hoyt, M.; Ramamurthi, R.J.; Walker, B.; Flack, S.H.; Bosenberg, A.; Franklin, A.; Polaner, D.M. Variation in pediatric local anesthetic dosing for peripheral nerve blocks: An analysis from the Pediatric Regional Anesthesia Network (PRAN). Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 45, 964–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, G.; McKendrick, M.; Taylor, A.; Lynch, J.; Ker, J.; Sadler, A.; Halcrow, J.; McKendrick, G.; Mustafa, A.; Seeley, J.; et al. Validity and reliability of metrics for translation of regional anaesthesia performance from cadavers to patients. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 368–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, S.; Mohr, D.; Bosenberg, A.; Van Schoor, A.N. A cadaveric study of the erector spinae plane block in a neonatal sample. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2020, 45, 386–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, S.; Mohr, D.; Bosenberg, A.; Van Schoor, A.N. The anatomical features of an ultrasound-guided erector spinae fascial plane block in a cadaveric neonatal sample. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2020, 30, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Govender, S.; Mohr, D.; Van Schoor, A.N.; Bosenberg, A. The extent of cranio-caudal spread within the erector spinae fascial plane space using computed tomography scanning in a neonatal cadaver. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2020, 30, 667–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Schoor, A.N.; Boon, J.M.; Bosenberg, A.T.; Abrahams, P.H.; Meiring, J.H. Anatomical considerations of the pediatric ilioinguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2005, 15, 371–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schoor, A.N.; Bosman, M.C.; Bosenberg, A.T. Revisiting the anatomy of the ilio-inguinal/iliohypogastric nerve block. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2013, 23, 390–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinoso-Barbero, F.; Saavedra, B.; Segura-Grau, E.; Llamas, A. Anatomical comparison of sciatic nerves between adults and newborns: Clinical implications for ultrasound guided block. J. Anat. 2014, 224, 108–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acar, A.A.; Bösenberg, A.T.; van Schoor, A.N. Anatomical description of the sciatic nerve block at the subgluteal region in a neonatal cadaver population. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2017, 27, 643–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigge, L.; van Schoor, A.N.; Bosman, M.C.; Bosenberg, A.T. Clinical anatomy of the maxillary nerve block in pediatric patients. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2014, 24, 1120–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albokrinov, A.A.; Fesenko, U.A. Spread of dye after single thoracolumbar paravertebral injection in infants. A cadaveric study. Eur. J. Anaesthesiol. 2014, 31, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cihan, E.; Buyukmumcu, M.; Ayd1n-Kabakc1, A.D.; Ak1n, D.; Gungorer, S. A Guideline for Femoral Nerve Block with the Age-Related Formulas Obtained from the Distances Between the Femoral Nerve and Surface Anatomical Landmarks in Fetal Cadavers. Int. J. Morphol. 2022, 40, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Aggarwal, A.; Sahni, D.; Harjeet, K.; Barnwal, M. Anatomical survey of terminal branching patterns of superficial branch of radial nerve in fetuses. Surg. Radiol. Anat. 2012, 34, 415–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prigge, L.; van Schoor, A.N.; Bosenberg, A.T. Anatomy of the greater occipital nerve block in infants. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2019, 29, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagmurkaya, U.; Uysal, I.I.; Kabakci, A. Definition of an Effective Site for Greater and Third Occipital Nerve Block in the Nuchal Region: A Fetal Cadaver Study. Turk. Neurosurg. 2023, 33, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosenberg, A.T.; Van Schoor, A.N.; Bosman, M.C. Infraclavicular Brachial Plexus Blocks. Comparison of Neonatal and Adult Anatomy; UPSpace: West Chester, PA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bösenberg, A.T.; Kimble, F.W. Infraorbital nerve block in neonates for cleft lip repair: Anatomical study and clinical application. Br. J. Anaesth. 1995, 74, 506–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zadrazil, M.; Feigl, G.; Opfermann, P.; Marhofer, P.; Marhofer, D.; Schmid, W. Ultrasound-Guided Dorsal Penile Nerve Block in Children: An Anatomical-Based Observational Study of a New Anesthesia Technique. Children 2023, 11, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, A.J. In search of the big question. Paediatr. Anaesth. 2012, 22, 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naik, V.M.; Fabila, T.S. Practicing pediatric regional anesthesia: Children are not small adults. J. Anaesthesiol. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 39, 167–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloomfield, F.H. The challenges of research participation by children. Pediatr. Res. 2015, 78, 109–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behr, A.U.; Chan, V.W.S.; Stecco, C. Living versus cadaver fascial plane injection. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2019, 45, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sondekoppam, R.V.; Tsui, B.C.H. “Minimally invasive” regional anesthesia and the expanding use of interfascial plane blocks: The need for more systematic evaluation. Can. J. Anaesth. 2019, 66, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavan, P.G.; Stecco, A.; Stern, R.; Stecco, C. Painful connections: Densification versus fibrosis of fascia. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2014, 18, 441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsharkawy, H.; Pawa, A.; Mariano, E.R. Interfascial Plane Blocks: Back to Basics. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2018, 43, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).