Abstract

Existing research has identified evidence-based strategies for mitigating fear and pain during needle procedures; yet, families often experience limited access to health professionals who deliver these interventions. Children may benefit from learning about such strategies in a developmentally appropriate and accessible format such as a picture book. This review aimed to summarize content related to needle procedures represented in picture books for 5- to 8-year-old children. Key terms were searched on Amazon, and the website was used to screen for relevant eligibility criteria. Three levels of screening and exclusions resulted in a final sample of 48 books. Quantitative content analysis was used to apply a coding scheme developed based on relevant Clinical Practice Guidelines and systematic reviews. Cohen’s Kappa indicated strong reliability, and frequencies were calculated to summarize the content. The books were published between 1981 and 2022. All 48 books included at least one evidence-based coping strategy. Distressing aspects such as scary visuals were often included (27.1%), as well as specific expressions of fear (52.1%) and pain (16.7%). Overall, this study paves the way for researchers interested in evaluating the effectiveness of picture books on children’s knowledge and self-efficacy, as well as creating interventions for coping.

1. Introduction

1.1. Overview

Undergoing needle procedures is a common experience throughout childhood [1]. In fact, children in Canada between the ages of 4 and 6 need vaccinations to start school and then continue to receive 1–2 yearly needles for booster and influenza vaccinations [2]. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, children are also being offered the COVID-19 vaccination and booster doses, which add to the over two dozen needles children may receive by the age of 18 [2]. Unfortunately, over half of children between the ages of 4 and 8 are fearful of needles to some extent with approximately 30% self-reporting high levels of fear [3]. This contributes to negative experiences with needle procedures. Ways to reduce needle fear are needed to prevent such negative experiences and promote vaccination uptake in children. Akin to their use for other health topics, children’s picture books may be an important source of developmentally appropriate education on needles and could be used by parents to help their child cope with their needle fear [4,5,6]. To our knowledge, there is no existing review summarizing the content of children’s picture books with respect to needles.

This study sought to capture what information picture books present to young children (5 to 8 years old) and their caregivers about needle procedures. The primary research question was: What content is available in existing commercially available children’s books regarding needle procedures? This study is part of a larger project aiming to include children’s voices in creating a needle fear intervention that includes a children’s book.

1.2. Childhood Needle Procedures and Needle Fear

As part of the recommended vaccination schedule, Canadian children may receive over two dozen needles before turning 18 [2]. According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, needle pain and fear are barriers to vaccination in 5 to 13% of children ages 18 and under [7]. Beyond vaccinations, children may also be fearful of other necessary needle procedures such as blood draws, which are used to monitor their health [8].

Needle fear is best understood as existing on a spectrum ranging from mild fear, which is normative, to high and clinically significant levels of fear [1]. While clinically significant levels of needle fear may warrant a diagnosis of Blood-Injection-Injury Phobia [9], high but subclinical levels of needle fear are also concerning due to their associated consequences. For example, highly fearful children may cry, freeze, or attempt to escape needle procedures [1]. This may impede the safe completion of the procedure.

High levels of needle fear are also associated with longer procedure times, increased pain, distressing memories related to the procedure that predict perceived pain at future appointments, and even ineffective pain management [1,3,10,11]. This creates a problematic cycle where fear and pain exacerbate each other and lead to adverse experiences with significant longitudinal implications. In fact, children with needle phobia may even need to be sedated to undergo routine needle procedures, which can entail additional risks [12]. Highly fearful children may also grow up and become parents who model needle fear to their own children, which further perpetuates this cycle [1]. As such, it is important to understand what resources exist that adequately equip young children and their caregivers with strategies to manage needle fear in order to “break the cycle” and ensure that needles that are important for both individual health (i.e., diagnosis, monitoring, treatment) and community health (i.e., community immunity from vaccination) are not delayed or avoided. The latter is critical following the COVID-19 pandemic, which highlighted the urgent need for targeted interventions that address needle fear as a barrier to vaccinations [7].

1.3. Needle Fear and Pain Management Strategies

Systematic reviews and resulting Clinical Practice Guidelines have identified evidence-based strategies for mitigating fear and pain during needle procedures for children. These strategies vary based on the level of fear (i.e., low to moderate vs. high), procedure type (e.g., vaccination), and type of intervention (e.g., psychological). Specifically, guidelines and systematic reviews exist for:

- (1)

- Low to moderate fear and needle pain management for vaccinations [13,14];

- (2)

- Exposure-based treatment for individuals with high levels of needle fear in the context of vaccinations [15,16];

- (3)

- Psychological interventions for needle procedures generally [17].

As venipuncture-specific guidance is more limited, recommendations for addressing children’s fear and pain during venipunctures can be extrapolated as relevant from guidance for vaccinations [13,14,15,16] and needle-related procedures generally [17,18].

Best practices for managing needle pain and fear from this evidence base are summarized in Table 1 according to the level of fear (high fear vs. low to moderate fear). For high levels of needle fear, exposure-based therapy (EBT) is recommended prior to the use of more typical pain and fear management strategies; however, for young children, the evidence is limited [15]. Muscle tension is another approach targeted towards those with high levels of needle fear who also experience vasovagal reactions such as dizziness and fainting [15]. EBT is considered the gold standard treatment for specific phobias [19,20] and involves gradual exposures in which patients face their feared stimuli or situation from least (e.g., seeing an illustrated needle in a book) to most feared (e.g., undergoing a vaccination) [21]. Receiving EBT from a trained professional is inaccessible for many due to the associated financial costs, lengthy waitlists, a shortage of trained clinicians, and social stigma [22]. Consequently, there is a serious need for more widely accessible interventions to support children with needle fear with learning how to manage their fear and cope during the procedure.

Table 1.

Recommended needle fear and pain management strategies for children ages 5–8 with other age specific information noted as relevant.

Low–moderate fear and pain management strategies for children ages 5 to 8 years old are grouped within the “5P” approach. The “5Ps” include process (e.g., clinician and parent education), procedural (e.g., avoiding aspiration for vaccinations), physical (e.g., positioning), pharmacological (e.g., topical anesthetics), and psychological interventions (e.g., distraction) [14].

1.4. Bibliotherapy and Children’s Picture Books

A promising method to support children with managing needle pain and fear is to equip them with information and coping strategies in a developmentally appropriate and engaging format that is conducive to their learning. More specifically, child and parent education about the other strategies presented in Table 1 could be achieved through children’s books. Books are a tool that can promote insight into personal challenges [23], and this has been known in the literature as “bibliotherapy”. In fact, books have been considered helpful for describing medical information to children as they provide both written and visual information concurrently, which may help enhance children’s comprehension, memory, and retention [24]. More specifically, children’s books have been used to provide developmentally appropriate education on anxiety [22,25] and health difficulties ranging from asthma to physical injuries and developmental disabilities [4,5,6]. They have also been used to facilitate children’s understanding of complex topics such as cancer, death, and grief [26,27,28], as well as components of medical procedures such anesthesia [29].

Tsao and colleagues created a picture book for pre-school-aged children in Taiwan that depicted a character undergoing a venipuncture [30]. They found that children in the picture book intervention group had significantly lower behavioral distress before, during, and after the venipuncture than children in the control group. While there may presently be other picture books that intend to prepare children for needle procedures [30], no known studies have summarized the included content and how consistent it is with evidence-based guidelines. It is important to explore what is currently available in children’s picture books that depict needle procedures to understand what is available for caregivers to support their children with managing their needle fear. Identifying strengths and relevant gaps in the books may ultimately inform the development of an evidence-based resource (e.g., a children’s picture book) that bridges knowledge to action gaps related to managing children’s pain and fear during needle procedures [31,32].

1.5. Objectives

The overarching objective of this study was to explore how existing children’s picture books present needle-related information and experiences using a rapid review methodology. Rapid reviews are an emergent method used to collect, analyze, and interpret evidence by streamlining or omitting certain steps to produce evidence in a resource-efficient, but systematic manner [33,34,35]. This methodology allowed us more flexibility to screen for and capture children’s picture books in comparison to other methods such as systematic or scoping reviews. By taking a rapid “snapshot” of children’s picture books on a platform that is constantly changing and updated (i.e., Amazon), this review could more quickly synthesize the evidence and inform interventions for needle fear.

The specific objectives of the review were to describe the content of children’s books related to:

- (1)

- What to expect during needle procedures (e.g., type of procedure, setting, people present);

- (2)

- Educational information related to needles (i.e., importance of needles, procedural and sensory information, adult-directed material for caregivers);

- (3)

- Expressions of needle fear and pain (i.e., crying, requesting support, verbal expressions (e.g., “that hurt!”, “I don’t want it!”));

- (4)

- Strategies for coping during needle procedures (i.e., evidence-based);

- (5)

- Unhelpful strategies and fear-inducing depictions of needles (i.e., not evidence-based strategies).

Given the exploratory nature of this study, no specific hypotheses were made.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

This review is part of a larger line of research on the creation of a needle fear intervention through a children’s book. Eligible books had to be picture books available for purchase in North America with a target age within 5 to 8 years. While picture books are also used by children ages four and under, this age range was excluded due to their more limited ability to report on future internal states different from their current state (e.g., anticipated fear) [36], which is an important component of the larger line of research.

Beyond the target age, to be eligible, the books had to reference in text and/or visually depict a vaccination or venipuncture procedure (e.g., blood draw). Needles associated with chronic conditions (e.g., finger pricks and insulin injections for diabetes, bone marrow aspirations and lumbar punctures for cancer, etc.) and needles provided at the dentists or vet were excluded as they would have differed in terms of children’s experiences, information needs, and the roles of parents and healthcare providers. Due to the geographical and cultural parameters of this study, only books in English were included. The specific screening criteria categories can be seen in Appendix A.

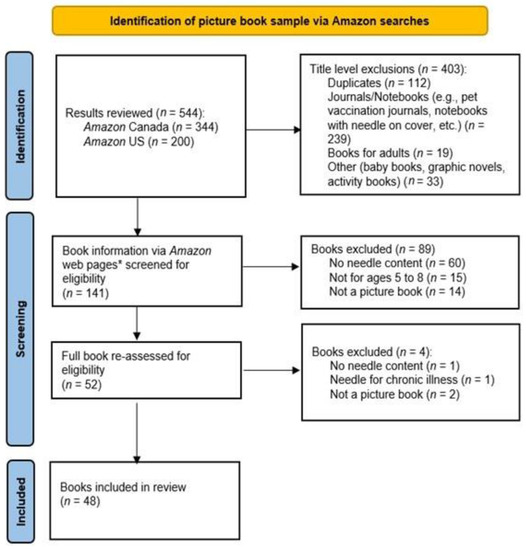

2.2. Search and Screening

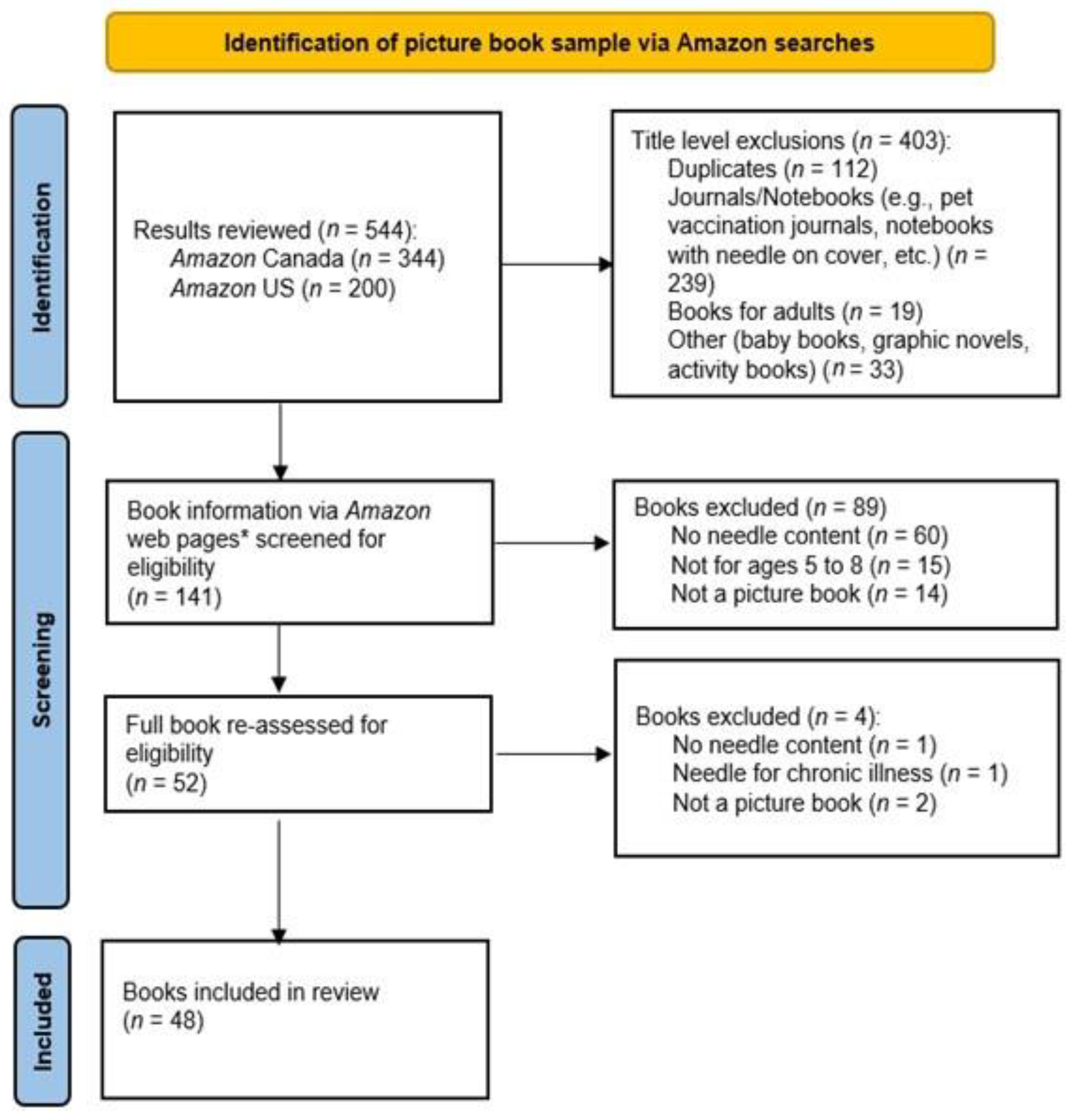

Two primary key terms (“Needle and Health”, “Doctor and Shot”) and three secondary key terms (““Needle” and “Vaccine””, “Vaccine”, “Check up”) were searched on Amazon, an online retailer that has been used to identify a sample in other similar studies [37,38,39]. The searches were conducted between 19 May and 23 May 2022. The first 100 results were reviewed for primary key terms followed by the first 50 results from secondary key term searches. Key terms were searched in the order listed above within the Children’s book section on Amazon Canada (primary, then secondary) followed by Amazon US (primary only due to repetitions). The picture book and English language filters were also turned on to refine each search. Search results were reviewed in the order featured on the website with any sponsored results automatically excluded; of note, the sponsored exclusions were not tracked; however, books that were “sponsored” (and, therefore, excluded) could also show up within the search results if relevant, and these were considered for inclusion. The books were first screened via Amazon web pages; for books meeting the inclusion criteria, the full book was obtained by purchasing a hard copy or e-book through Amazon or from a local library, when available. Full books were then assessed according to the previous screening criteria. Figure 1 outlines each stage of the screening process.

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram of book sample selection and screening method. * Amazon web pages include information such as author(s), cost, and options for ordering. They also include additional information about the book including, but not limited to book description, age range, reading level, reviews from purchasers, and book previews.

2.3. Analyses

Quantitative content analysis was used to evaluate the final sample of included picture books. This method is a systematic approach to describing the presence of specific content in the data [40,41,42]. This approach is typically used to analyze questionnaires or interviews, whereas this study examined children’s picture books. As such, our analyses involved assessing visual depictions of needle procedures, as well as important aspects of the narratives surrounding the procedure. We coded for both visual depictions and narrative/textual descriptions and did not distinguish between them, unless otherwise noted.

Researcher-developed deductive coding schemes for the picture books (Appendix B) and adult-directed supplementary material (Appendix C) were developed for the analysis based on needle pain and fear management Clinical Practice Guidelines and systematic reviews [14,15,16,17], the Child-Adult Medical Procedure Interaction Scale–Revised [43], an unpublished honors thesis on the depiction of needles in picture books, and expert input from study authors. The CAMPIS-R [43] is an observational behavior rating scale commonly used to capture adult and child behaviors during procedural pain, including child distress and coping, as well as adult “coping promoting” behaviors (e.g., distraction, command to engage in a coping strategy) and adult “distress promoting” behaviors (e.g., reassurance, criticism, apology). Thus, the CAMPIS-R informed categories related to depictions of commonly used, but unhelpful (not evidence-based) adult behaviors, as well as depictions of needle recipients that may impede coping (e.g., crying, verbal resistance).

For coding the children’s books, the primary investigator (H.N.) and two research assistants completed a training on the reference materials, coding scheme, and quantitative content analysis. All three individuals initially coded approximately 15% of the sample (i.e., 7 books). Coding was dichotomous for most categories (i.e., presence or absence of category) with some exceptions. For example, ominous or scary visual depictions of needles were coded on a 0–10 numerical rating scale (“no scary depictions” = 0, “mild” = 1–3, “moderate” = 4–6, “high” = 7–10). Cohen’s Kappa and percent agreement were used to calculate intercoder reliability (ICR) for each category. Percent reliability was calculated in addition to Cohen’s Kappa due to the latter being overly stringent for dichotomous coding (i.e., rating responses as either “0” or “1”). The lower end of the range in the Kappa values can be explained by there being a discrepancy in coding between raters on a category with very few responses.

Deriving ICR for each specific category allowed the primary investigator to assess and identify categories that needed refinement (e.g., categories < 0.7 were revisited); necessary modifications were made to the coding scheme. Refinement of categories included thorough discussion and consultation with the primary investigator’s supervisor (C.M.M.). Following the changes, the three coders re-coded the initial 7 books, as well as 3 more (i.e., 21% of the sample). Kappa and percent agreement were calculated again, and another round of minor revisions was made to the coding scheme through the same process. The two coders with the highest reliability then coded the remainder of the data. The final Kappa values from these two coders on the entire sample indicated strong overall reliability (M = 0.78; Median = 0.79; range: 0.43 to 1.0) and so did the percent agreement (M = 94.8%; Median = 95.8%; range: 77.1% to 100%).

A consensus-based coding approach was used to code the adult-directed supplementary material. Two authors of this work (A.T. and C.M.M.) who are also lead authors on the CPGs and systematic reviews on managing needle fear and pain, coded the adult supplementary sections together. Any disagreements were discussed until resolved. Frequencies were then calculated to summarize aspects of how needle procedures and related information are depicted in the sample of books.

3. Results

3.1. Overview

The sample included 48 children’s picture books (see Table 2 for the titles) with content related to needle procedures (see Figure 1). Unless otherwise noted, all analyses included the full sample of books (i.e., n = 48).

Table 2.

Summary of picture book sample, book costs, strategies included, and overall comments.

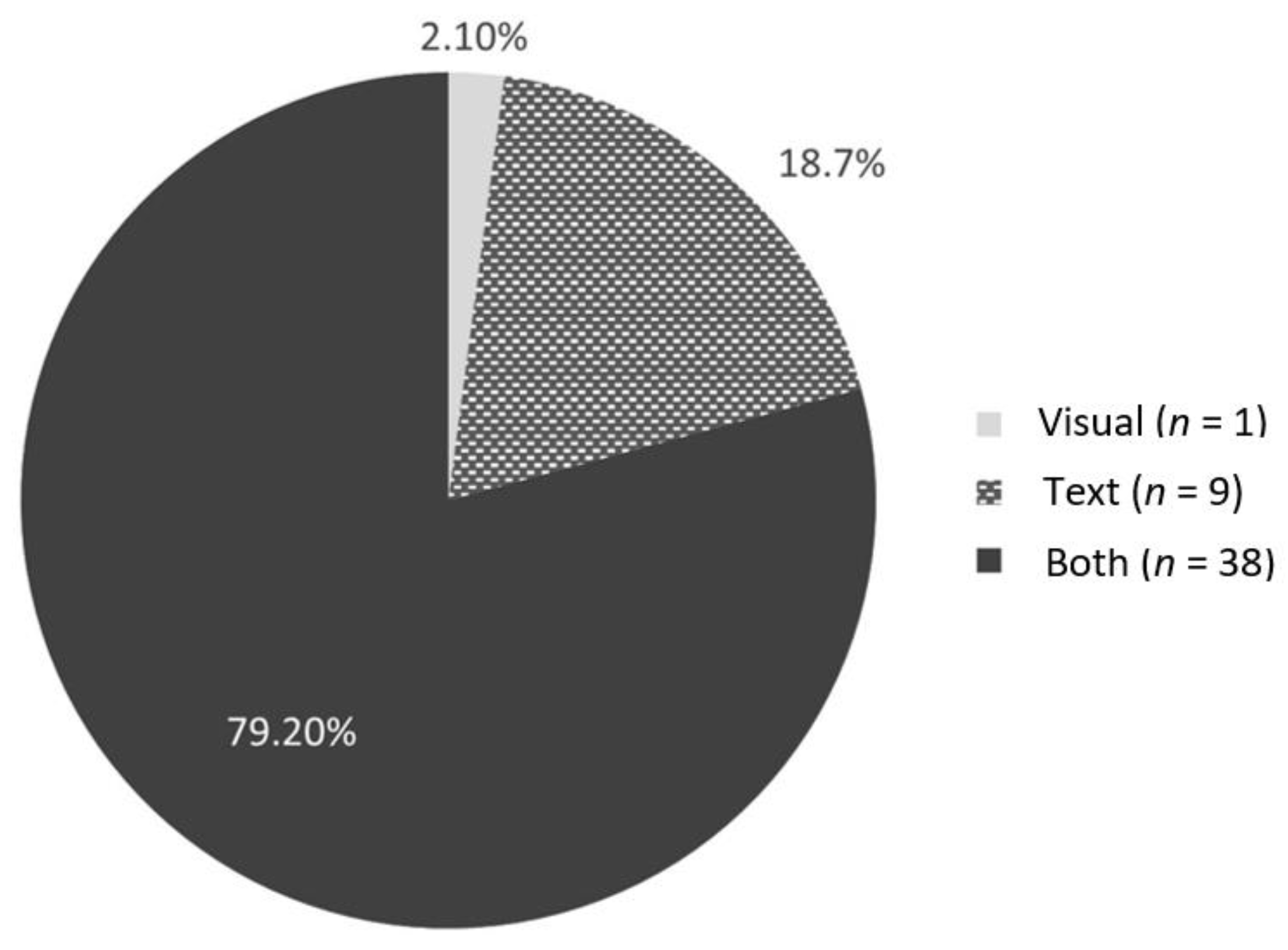

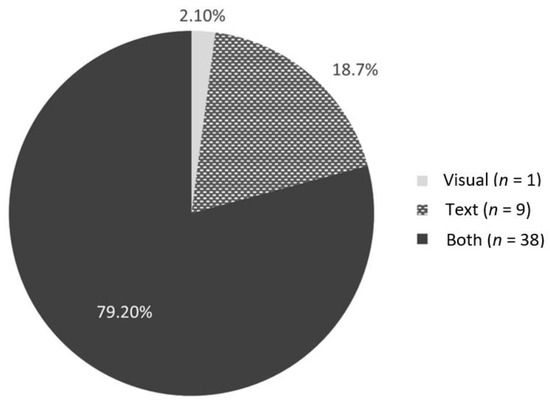

The books were published from 1981 to 2022; however, most (81.3%, n = 39) were published after 2015. The majority (64.6%; n = 31) are available in both hard copy and e-book formats. The average cost of the hard copy books was CAD 14.11 (Median = CAD 12.99, range = CAD 6.92 to 25.77), whereas the average cost of the e-books through KindleTM was CAD 4.15 (Median = CAD 6.19, range = CAD 0.99 to 9.99). Needle-related information and experiences were most often represented both visually and in text (Figure 2), and the majority of the sample (77.1%, n = 37) featured a character and narrative. A small number of books (6.3%, n = 8) did not depict a story line and were primarily educational information for children.

Figure 2.

Proportion of needle procedures depicted visually through pictures only, described in text only, or referenced both visually and within text (n = 48).

3.2. Objective 1: What to Expect during Needles

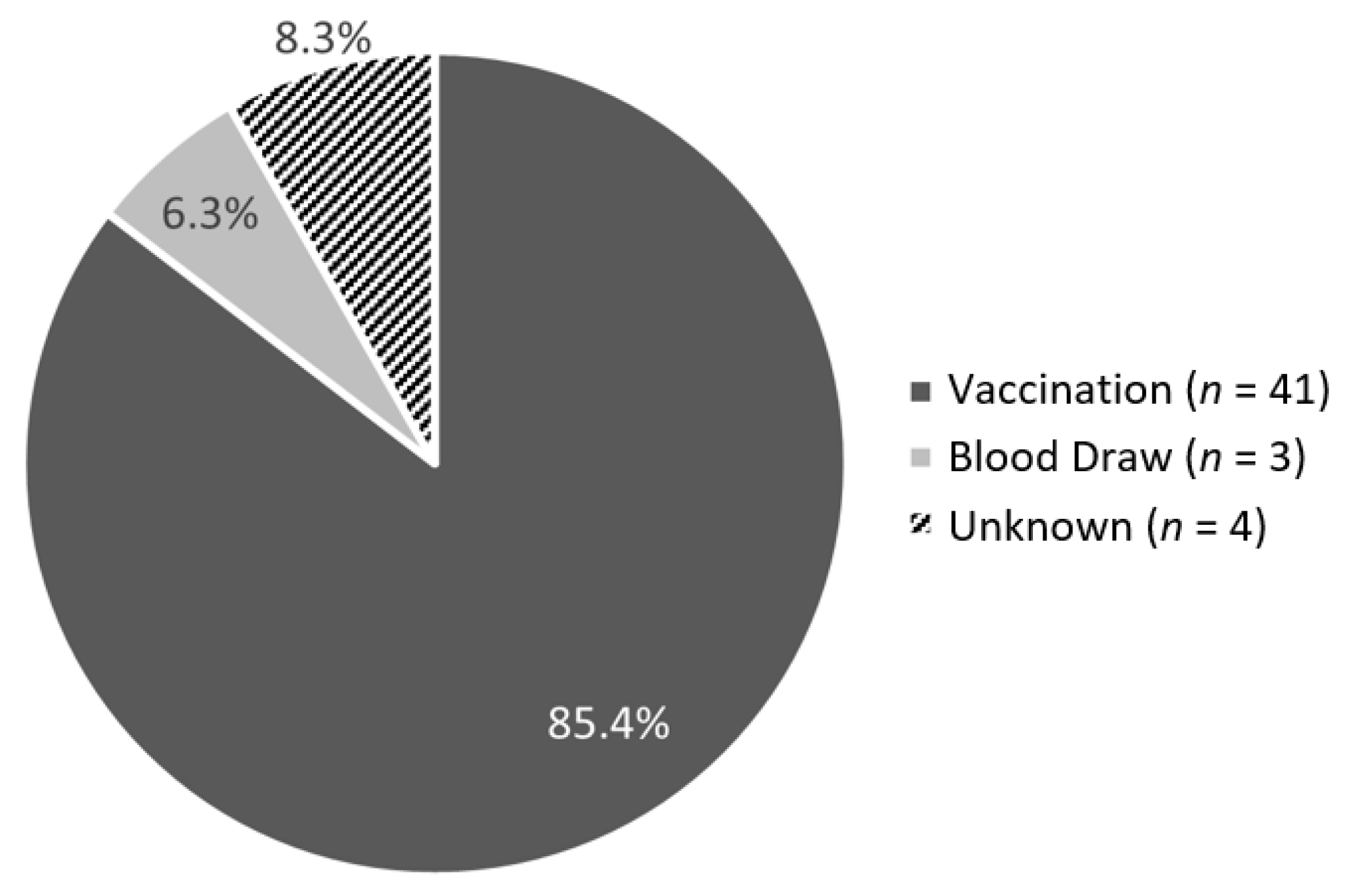

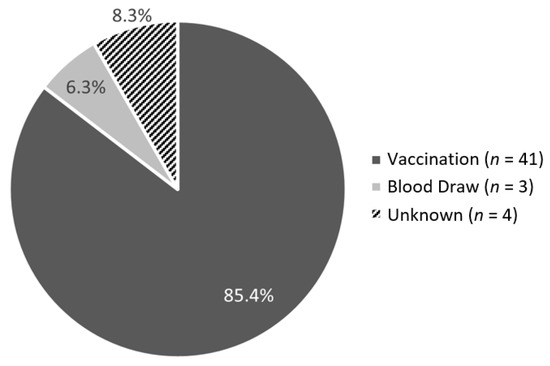

Figure 3 represents the breakdown of the types of needle procedures referenced in the sample, with the majority being vaccinations (85.4%, n = 41). The setting of each book was also examined to understand the context within which needles are typically presented. Most needle procedures (75%, n = 36) were set in a doctor’s clinic, hospital, or general exam room setting. Three books (6.3%) depicted the needle procedure in a school setting. No needle procedures were set within the home. The remaining books (10.4%, n = 5) fell into the “other” category and depicted random or unclear locations (e.g., field, boat, dream, etc.). In 66.7% of the sample (n = 32), only the needle procedure was referenced or depicted, whereas almost a third of the books (31.3%, n = 15) also included other procedures that commonly occur at doctor’s appointments such as checking height and weight, vision, breathing, and testing reflexes.

Figure 3.

Types of needle procedures represented within the sample (Ntotal = 48).

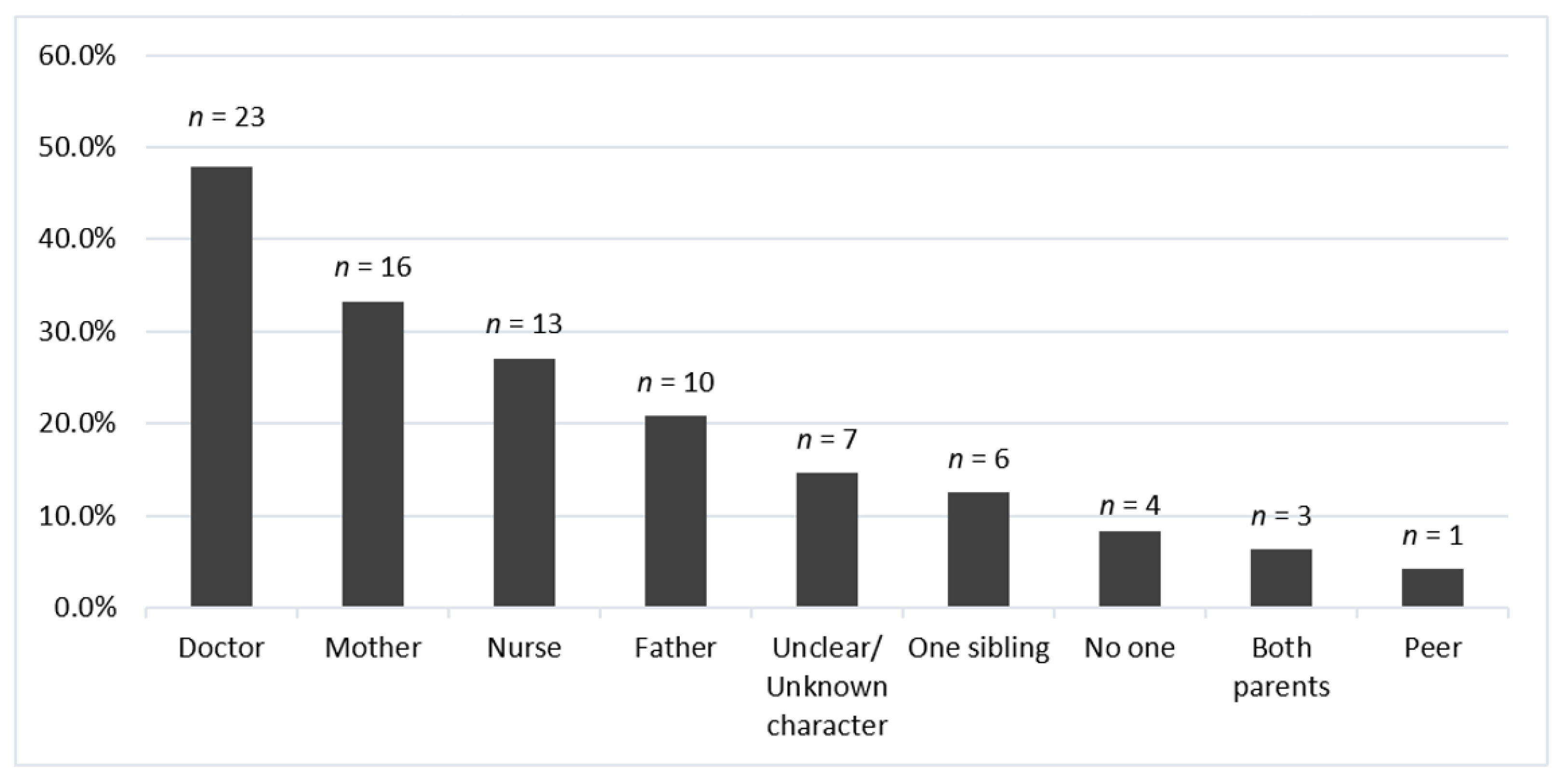

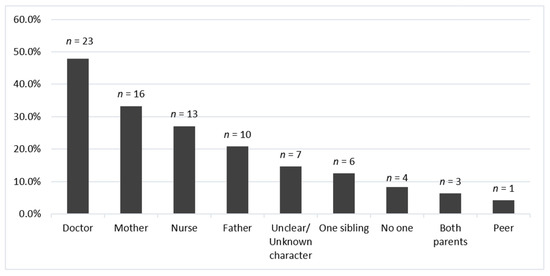

Regarding characters present during the procedure, a caregiver figure was present in 45.8% of the books (n = 22); of these, mothers were represented the most (72.7%, n = 16). Within clearly depicted healthcare providers, only doctors and nurses were represented. The list of coded characters is reflected in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Frequencies of characters other than the child present during needle procedures (Ntotal = 48). The following character categories had frequencies of 0%: multiple siblings, teacher, grandparent(s), child life specialist, mental health provider, pharmacist.

3.3. Objective 2: Educational Information about Needles

In regard to what children are learning about needles, sensory (i.e., what it will feel like) and procedural (i.e., what will happen) information was provided in 60.4% (n = 29) and 39.6% (n = 19) of the books, respectively. The importance or rationale for receiving a needle was explained in 81.3% (n = 39) of the books. Education about the procedure that was given in advance of the needle (e.g., at home, in the car, waiting room, etc.) was provided to the character or reader in approximately half the sample (52.1% n = 25).

Beyond the children’s story, 16.7% of the books (n = 8) featured an additional educational section targeted towards adults, which are summarized in Table 2. These adult-oriented sections ranged from 1 page of bullet point tips for getting a needle to a near 30-page guide outlining strategies to support caregivers of children with varying degrees of needle fear. The expertise of book authors who included supplementary adult-targeted material was also reviewed, and 62.5% of the books had an author (or authors) with relevant credentials or experience (e.g., child-life specialist, pediatrician, child psychologist, play therapist, etc.). Within the eight books, 50.0% (n = 4) provided a definition, description, or explanation of the fear of needle procedures that appeared to be accurate. Four books (50%) provided an explanation of how vaccinations work, and only 25.0% (n = 2) explained community (herd) immunity in a manner that seemed accurate. Fifty percent (n = 4) of the books with adult material referenced the use of mental visualization or imagination to cope with needle fear, and two books (25.0%) referred to providing children with a desirable item or experience following successful completion of a needle procedure (i.e., reward). Using cold vibration and topical anesthetics was also referenced in 25.0% (n = 2) of the adult sections. In the majority of adult-oriented sections (87.5%, n = 7), targeted parent and child education were included in many forms including lists with tips and guidance on how to use strategies (e.g., blowing bubbles, visualization).

Other helpful strategies referenced included parent presence during the needle (62.6%, n = 5), using neutral wording to signal the procedure (12.5%, n = 1), and avoiding excessive reassurance and false suggestions (50.0%, n = 4). Distraction was a key strategy present generally in 37.5% (n = 3) of the adult guides. Distraction using breathing specifically was included in 25.0% (n = 2) of the adult sections. Exposure-based therapy/modelling was referenced in only one of the adult sections (12.5%). None of the supplemental adult sections included references to evidence-based strategies such as avoiding aspiration, avoidance of restraint, providing the most-painful needle last, and using upright positioning, muscle tension, or applied tension. Qualitative impressions of each adult supplemental section are included in Table 2.

3.4. Objective 3: Expressions of Fear and Pain

In examining how specific expressions of fear and pain were represented within our sample, we found that approximately half of the full sample (52.1%, n = 25) included characters verbally expressing their fear of the needle procedure (e.g., “I’m scared”, “I’m afraid of needles”, etc.). In contrast, pain was verbally expressed in 16.7% of the books (n = 8). Verbal expressions of reassurance and/or false suggestion (e.g., “don’t worry, it won’t hurt”, “it will be fine”) were included in 29.2% of the books (n = 14). In 29.2% of the sample, the needle recipient sought information about the needle (e.g., “why do I need it?”, “will it hurt?”, “when will it end?”) (n = 14). Depictions and/or descriptions of crying, and verbal resistance (e.g., “I don’t want it”, “stop!”) were each included in 20.8% of the books (n = 10). Only one (2.1%) book depicted and/or described a character requesting emotional or physical support (e.g., “can you hold my hand?”, “hold me!”). In contrast, 12.5% (n = 6) of the sample depicted and/or described distress in some other manner (e.g., running away during procedure, hiding from needle, etc.).

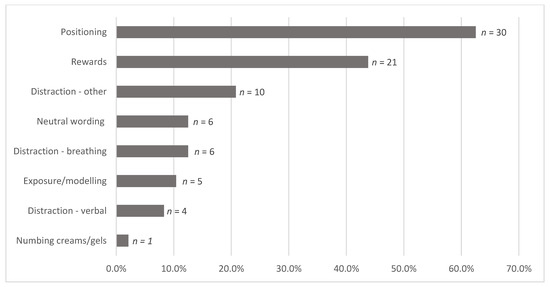

3.5. Objective 4: Coping Information for Needle Procedures

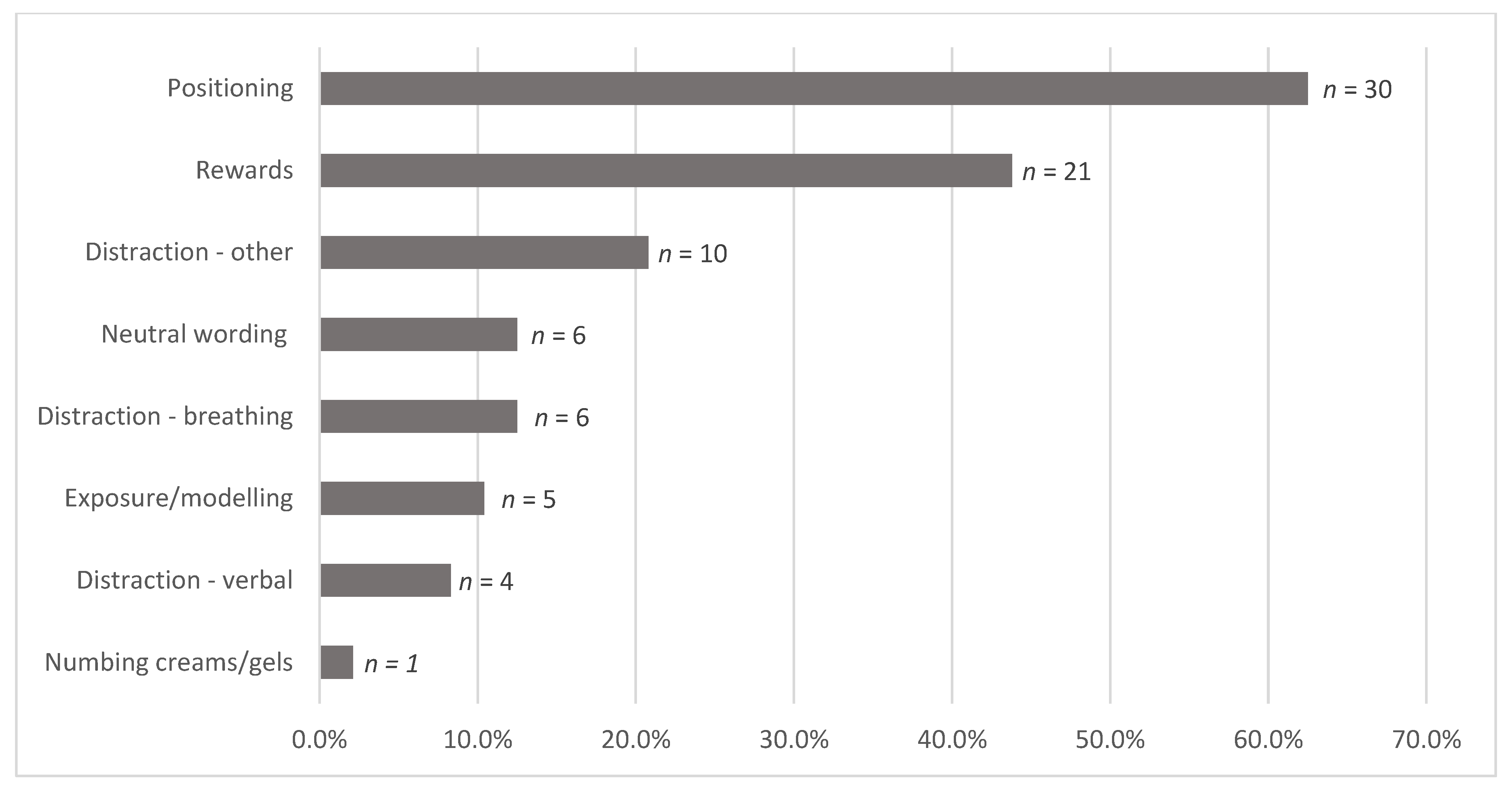

All 48 books (100%) included at least one evidence-based strategy for coping with needle fear, as reflected in Figure 5. Using upright positioning was commonly depicted (>60%). Forms of distraction beyond breathing, media, and verbal distraction were depicted or described in a fifth of the sample (20.8%, n = 10) and most often included guided imagery or visualization (e.g., picture self as a brave lion, imagine fish swimming in ocean), or singing. No distraction via media or technology (e.g., tablets, VR, phones, etc.) was depicted.

Figure 5.

Evidence-based and other helpful coping strategies (Ntotal = 48). The following strategy categories had frequencies of 0%: muscle tension, distraction: media.

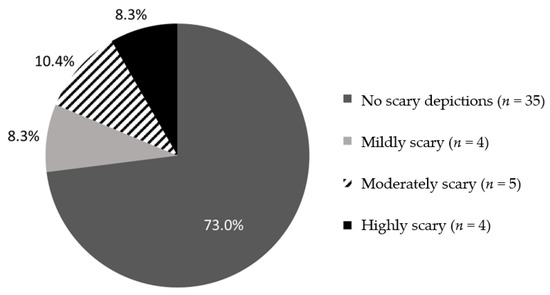

3.6. Objective 5: Unhelpful Strategies and Fear-Inducing Depictions

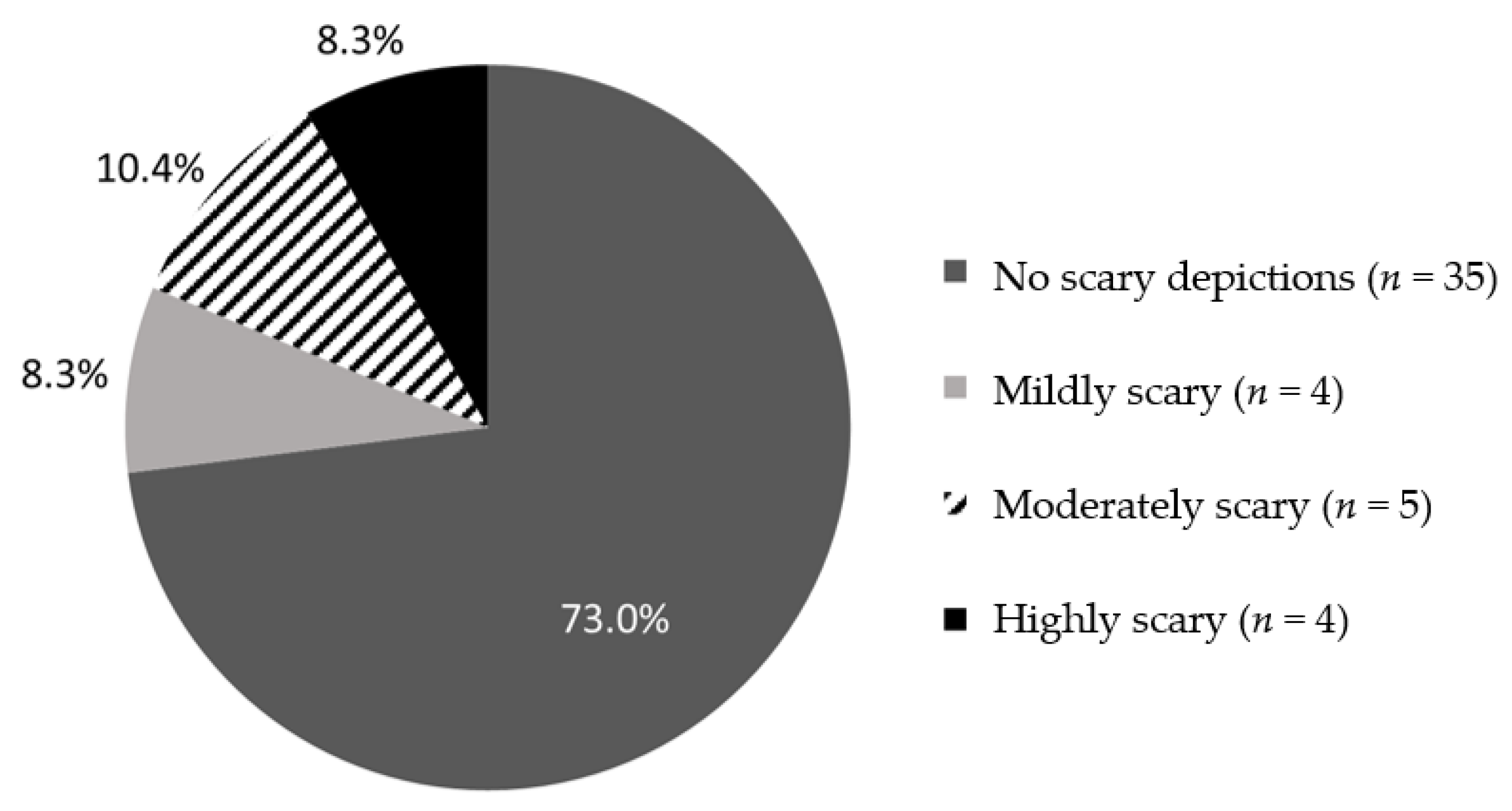

Strategies that are not promoted in Clinical Practice Guidelines and systematic reviews included the use of ice, vapocoolants, and oral pain medication. The use of ice was depicted in one book (2.1%), whereas the other aforementioned strategies were not referenced. Just over one quarter (27.1%; n = 13) included ominous or scary visual depictions (e.g., unrealistically large needles, dark or scary visuals, etc.); see Figure 6. In contrast, the presence of exaggerated or scary written descriptions were found in 8.3% of the books (coded dichotomously). Specific statements included that are associated with escalating distress included: apologies (2 books; 4.2%), simplified reassuring statements and false suggestions (e.g., “don’t worry”, “it won’t hurt”), which came up in 29.2% (n = 14) of the books, as well as criticism (“why are you crying so much?”), which was not present in any book. The use of restraint was not depicted in any of the 48 books.

Figure 6.

Frequency and intensity of scary visual depictions in children’s books as coded from “no scary depictions” = 0, “mild” = 1–3, “moderate” = 4–6, to “high” = 7–10 (Ntotal = 48).

4. Discussion

4.1. General Discussion

To our knowledge, this review is the first to explore content related to needle procedures in children’s picture books. The sample of picture books provided a “snapshot” of the kind of information children may receive at an early age in relation to needle procedures. Overall, vaccinations made up the majority of needle procedures included. This is unsurprising as most Canadian children ages 5 to 8 in Canada require mandatory vaccinations to attend school [2], making it a more pervasive procedure than childhood venipunctures. Yet, needle fears that stem from vaccinations may go on to generalize to other stimuli or procedures such as venipunctures [8], which were largely unrepresented within the books. Most needle procedures were also set in clinic, hospital, or general exam rooms, which is consistent with where needle appointments often take place. Mass immunization settings, which have grown in prevalence over the last few years [92], were not represented in the sample despite some books being published during the COVID-19 pandemic. A strength observed in most books (81%) was including an explanation for why needles are important. Many of these explanations were specific to vaccines, how they work, and what their function is on an individual and community level. Being exposed to the purpose and function of vaccinations may contribute to building children’s trust in their effectiveness. This is important because a driving factor of vaccine hesitancy is confidence and trust in the safety and effectiveness of vaccinations [93]. While having information about and an understanding of vaccinations early on may help protect children from the readily accessible negative concerns and unverified medical information that exists on online platforms [94], such rationale-based information is insufficient on its own. Children must be provided with information on how to prepare for and cope with the needle procedure. For example, 16.7% of the books targeted caregivers directly by providing them with educational information or tips at the end of the book, some of which they could directly use to teach their child coping strategies. This supplementary information varied in length (e.g., 1 page of tips, 30-page parent guide) and quality (vague information, contradictions, confusing). This is disappointing as caregivers are in the unique position to help prepare their child for the procedure beforehand, as well as support in coping during the procedure. It is evident that caregivers may benefit from a practical, evidence-based, structured guide for supporting their child with needle pain and fear.

Consistent with recommendations for vaccinations [13], many books provided information about how the needle procedure might feel (sensory information) and what might happen (procedural information). Interestingly, the former information was provided more often (60.4%) than the latter (39.6%). According to a study exploring 7- to 10-year-old children’s perspectives on physician check up’s/wellness visits, children who endorsed higher ratings of fear were more likely to want increased preparatory information and participation [95]. As such, authors seeking to prepare children for needles through books should consider including more descriptive and step-by-step information about the procedures (e.g., describe tying a tourniquet, cleaning insertion site, etc.).

Given the focus of the pediatric literature on pain during needles, it was surprising that verbal expressions of pain were only reported in 16.7% of the books. A potential explanation may be that authors are hesitant to make direct references to the inherently painful nature of pain due to concerns around instilling fear in children. In exploring what children may learn about coping with needle pain and fear from our sample, we noticed that several depicted strategies were consistent with existing systematic reviews and Clinical Practice Guidelines [13,14,15,16,17] including: upright positioning of the character receiving the needle, use of neutral wording, modelling and/or exposure (refers to modelling or exposure (“facing fears”) in advance of the needle procedure (e.g., showing character a needle before procedure, watching a video of needle before the procedure, demonstrating giving the needle to a stuffed toy, etc.)), the use of topical anesthetic creams or gels, and distraction using breathing. It was surprising that the books did not depict distraction techniques that involved media or technology of any kind (e.g., tablet, phone, virtual reality, etc.) given the accessibility of such technology and increasing empirical evidence [96,97].

In conjunction with evidence-based strategies, this study also aimed to examine depictions and descriptions of strategies that may be unhelpful or promote distress in children. We observed that many books had a “check up” narrative and depicted other procedures (e.g., reflex test, vision test) in addition to a needle procedure. This could be helpful in that needles are placed in a broader context and procedural information is being provided about these aspects. However, such content may also be difficult for fearful children to consume as a subset of children fear many aspects of their check up appointments beyond needles such as ear checks, throat swabs, and the use of the tongue depressor [95]. Examining these procedures and how children may perceive them was beyond the scope of this review; this should be considered in future research.

While evidence-based recommendations advise against making false suggestions to children such as “it won’t hurt”, 29.2% of the books included such reassuring statements and false suggestions. While research has emphasized the importance of being honest and preparing children for the sensory components of the procedure [1,36], it is unclear how directly children should be informed and educated about needle pain. Future research should explore how children perceive educational information about needle pain and its impact on their fear of needle procedures.

4.2. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research Directions

This review has a number of strengths including the use of a rigorous coding scheme developed from existing systematic reviews and Clinical Practice Guidelines [13,14,15,16,17], overall good reliability between coders indicated by Kappa values and percent agreement, and consensus-based coding of adult material by two of the lead authors of the aforementioned reviews and guidelines. Considerations of access were also at the forefront of this work. The Amazon website, which was carefully selected to identify the book sample, is more broadly accessible to parents in North America than traditional approaches (e.g., library catalogues, which may vary by community and region). More than half the sample was accessible in both hard copy and e-book format, with the latter being more affordable for families. This review also identified multiple books that caregivers can use to prepare their children for their needle appointments. Educating children in this manner may serve as a promising approach for reducing children’s distress during needle procedures, as demonstrated by Tsao and colleagues [30].

This review also has some limitations. While the sample was identified in May 2022, searches related to accessibility (i.e., book cost and format) were conducted in January 2023. There may be newer books or other evidence-based books that were not available through Amazon and, thus, could not be included. While some e-books may be accessed for “free” with an Amazon Kindle subscription, the sample did not include free books that would be accessible to low SES families and those who do not have an Amazon subscription, account, or access to the Internet. Another limitation concerns the focus of the coding scheme: the picture books were reviewed for very specific visual content and types of written statements, as opposed to a full thematic analysis of each book. While the latter would more fully identify the themes or “lessons” children are taking away from the books (e.g.: fears can be overcome; needles are here to help), capturing such abstract and varying narratives was beyond the scope of this review because: (a) they cannot be coded in a systematic manner consistent with the methodology required of a rapid review, and (b) we cannot infer the themes that would be most salient to children. Likewise, while this review considered how “scary” and “ominous” the books were, despite good reliability in the coding, variability was observed in what each coder found to be “scary” because fear is subjective. Thus, in future research, children should be asked to directly review and report on relevant themes and the depiction of needles in picture books as adults’ perspectives on what they think children learn or fear may be skewed and inaccurate. Furthermore, given that we did not code for socioeconomic class, religion, language (all books were in English), or ethnicity, understanding representation in children’s books related to needles remains an important area for future research.

While educational videos, educational pamphlets, and a multifaceted CARD™ System have been used to make evidence-based strategies for coping with needle fear and pain actionable [98,99], the CARD™ System is the only known widespread intervention that has been evaluated and to have demonstrated effectiveness and utility [100,101]. Without a systematic evaluation of the picture books, we cannot infer that any of them are effective in supporting children with their needle fear and pain, despite depicting evidence-based strategies.

Additionally, the study only screened for picture books written in English and available in North America. While examining books in other languages was beyond the scope of the study, it is important to recognize that other picture books describing and depicting needle procedures likely exist in other languages. Although differences in the provision of needles between regions and cultures may be challenging to represent in a single picture book, children globally would likely benefit from a free and accessible book that is consistent with evidence-based recommendations and can be translated easily.

Overall, this review will help researchers understand how needle procedures are presented to young children currently and what gaps may need to be addressed in an intervention that uses bibliography to support children with needle fear and their caregivers. For example, given the absence of depictions of mass vaccination clinics, authors should consider whether it may be beneficial to represent this unique vaccination setting in future books. This may be particularly important because mass immunization clinics are often overwhelming for highly fearful children, as well as conducive to experiencing Immunization Stress-Related Responses [102,103]. More generally, interventions that promote self-efficacy in caregivers and children may help reduce reliance on mental health professionals to treat needle fear and help prevent a myriad of consequences such as healthcare avoidance, modelling fear to others, and ineffective pain management [1,3]. Further research is needed to determine whether this form of educational intervention will appropriately meet the needs of children requiring support and whether this type of content can lead to improved management of pediatric needle fear and pain.

5. Conclusions

The present study is the only known review of picture books for 5- to 8-year-old children that depict or describe needle procedures. The results provided a “snapshot” of the kind of evidence-based information related to needle procedures currently accessible to young children and their caregivers. Overall, this study serves as an important first step towards the development of an e-resource for caregivers and children to gain the information and strategies needed to manage needle fear and pain more independently at home.

Author Contributions

This work is part of H.N.’s doctoral dissertation under the supervision of C.M.M. All listed authors meet the ICMJE authorship criteria. All authors discussed the results, commented on the manuscript, and contributed meaningfully to the manuscript’s development. Conceptualization, H.N., C.M.M., A.T. and K.A.B.; methodology, H.N., C.M.M., A.T. and K.A.B.; coding; H.N., O.D., A.T. and C.M.M.; analysis, H.N.; writing—original draft preparation, H.N.; writing—review and editing, H.N., C.M.M., O.D., A.T. and K.A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Infrastructure support was provided by the Canadian Foundation for Innovation and Ministry of Research Innovation funding awarded to C. Meghan McMurtry.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not Applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Screening criteria for identifying children’s picture book’s depicting needle procedures.

Table A1.

Screening criteria for identifying children’s picture book’s depicting needle procedures.

| # | Screening Criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | English | Yes | |

| No | |||

| 2 | For ages 5 to 8 (inclusive)? | Yes, explain why: (1 needed) | Listed age range includes ages 5 to 8 Listed Reading Level: Kindergarten Text Included Other: ___________ |

| No, explain why: (more than yes needed, if = then yes) | Listed age range < 5 Listed age range > 8 Only illustrations/ No text Reading Level: preschool Reading Level: Grade 4+ Other: ______________ | ||

| 3 | From the title, description, and/or preview, does the book appear to have content related to needles or a needle procedure (i.e., vaccinations, blood draws)? | Yes, explain why: (1 needed) | Needle related title Needle related description/comments Needle depicted in preview Other: _____________ |

| Yes, but content related to: | Diabetes (e.g., finger pricks, insulin injections) Cancer (e.g., biopsy, bone marrow aspiration) Other chronic illnesses Dentistry (e.g., needles for numbing) Veterinary Services (i.e., needle for an animal) | ||

| No, explain why: | Sewing/Knitting needles Taking chances Other: ________________ | ||

| 4 | Picture Book? | Yes, explain why: (1 needed) | Target age: 2 to 8 <1000 words More Illustrations than text ≤32 pages Dimensions ≤ 25 cm Other: ____________ |

| No, explain why: (more than yes needed, if = then yes) | More text than illustrations Has chapters >1000 words >32 pages Graphic Novel Other: _______________ | ||

| 5 | Eligible to order? | Yes | |

| No |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Coding scheme for children’s picture books informed by CPGs and systematic reviews on managing needle fear and pain.

Table A2.

Coding scheme for children’s picture books informed by CPGs and systematic reviews on managing needle fear and pain.

| Information based/educational (No characters or narrative, just explanations or facts) | 1 |

| Character/story based (consists of a narrative. e.g., character getting a needle procedure, character being educated about needles) | 2 | |

| Both information and story based (includes separate educational section and separate narrative-based story) | 3 | |

| Other (specify) | 4 | |

| ONLY described or explained (i.e., no needle or needle procedure is visually depicted) | 1 |

| ONLY pictured/depicted (i.e., a needle/injection/similar shaped object is visually seen) | 2 | |

| BOTH described/explained AND pictured/depicted | 3 | |

| Other (specify) | 4 | |

| Doctor’s clinic/Physician’s office/Hospital/General Exam Room | 0/1 |

| Home | 0/1 | |

| School | 0/1 | |

| Other (specify) | 0/1 | |

| Only needle procedure shown/described/depicted | 1 |

| Presence of ANY other procedures (e.g., throat check up, reflex test, stethoscope, etc. depicted explicitly) | 2 | |

| Other (specify) | 3 | |

| Blood draw/venipuncture (do NOT code unless explicitly mentioned, blood seen going in/out of needle) | 0/1 |

| Vaccination/ immunization/shot (do NOT code unless explicitly mentioned) | 0/1 | |

| Unknown Needle Procedure (a needle is depicted/mentioned but vaccination/blood draw are not explicitly mentioned, and the pictures do NOT depict blood going in/out of the needle) | 0/1 | |

| Other (specify here if it does not fall into any of the above categories) | 0/1 | |

| Parent (Mom) | 0/1 |

| Parent (Dad) | 0/1 | |

| Parents (more than one)- specify | 0/1 | |

| Grandparent (one) | 0/1 | |

| Grandparents (more than one) | 0/1 | |

| Friend/peer (one) | 0/1 | |

| Friends/peers (more than one) | 0/1 | |

| Sibling (one) | 0/1 | |

| Siblings (more than one) | 0/1 | |

| Teacher | 0/1 | |

| Nurse (only code if nurse is explicitly mentioned through wording of story or depicted in a picture. A character looking like a nurse (e.g., wearing nurse hat and uniform) is NOT sufficient to be coded into this category) | 0/1 | |

| Pharmacist | 0/1 | |

| Doctor/Physician (only code if doctor/doctor’s office is explicitly mentioned through wording of story or depicted in a picture (e.g., character has name tag with “Dr. Bear”) | 0/1 | |

| Child life specialist | 0/1 | |

| Mental health professional (e.g., psychologist, therapist, etc.) | 0/1 | |

| Other (specify; includes other health care providers that cannot be coded into any of the above categories) | 0/1 | |

| N/A (No others present) | 0/1 | |

| Restraint of character receiving needle (e.g., being held down to exam table, being held too tight by another character) | 0/1 |

| Application of ice (or other cold object (e.g., frozen bag of vegetables) | 0/1 | |

| Vapocoolants (i.e., cold spray) | 0/1 | |

| Oral Pain Medication (e.g., Tylenol, Advil, etc.) | 0/1 | |

| Tangible Rewards before or after the needle procedure. Can be mentioned, depicted, or both. Does NOT include verbal praise. (e.g., lollipop/sticker after needle, parent referencing going out to ice cream or buy a toy after the procedure) | 0/1 | |

| N/A (No Not Evidence-Based Strategies Depicted) | 0/1 | |

| Positioning–Sitting upright | 0/1 |

| Muscle Tension (e.g., description or depiction of tensing/squeezing muscles) | 0/1 | |

| Numbing creams, gels, and/or patches | 0/1 | |

| Distraction during the procedure–verbal (e.g., asking character an unrelated question during procedure, “what should we do after we’re done here?”) | 0/1 | |

| Distraction during the procedure–breathing toy (e.g., bubbles, pinwheel, etc.) | 0/1 | |

| Distraction during the procedure–media (e.g., showing a video and/or playing music) | 0/1 | |

| Distraction during the procedure–Other (please describe) (e.g., guided imagery) | 0/1 | |

| Neutral wording to signal the procedure (e.g., “here we go”, “here it comes”, “3, 2, 1…”) | 0/1 | |

| Presence of parent/caregiver character during needle procedure | 0/1 | |

| Character and/or reader education–procedural information (e.g., “now I am going to clean your arm”, “this part will take 2 min” etc.) | 0/1 | |

| Character and/or reader education–sensory information (e.g., “this may feel cold”, “you might feel a pinch”) | 0/1 | |

| Character and/or reader education–importance of needles/ purpose of procedure | 0/1 | |

| Character and/or reader education–in advance of procedure (e.g., at home, in the car, in waiting room, etc.) | 0/1 | |

| Exposure or “facing fears” in advance of procedure (e.g., showing character a needle before procedure, watching a video of needle before procedure, giving a toy a needle) | 0/1 | |

| Other (specify) | 0/1 | |

| N/A (None of the evidence-based strategies represented) | 0/1 | |

| Crying/Screaming (e.g., “Mr. Bear sobbed during the poke”, or depiction of tears, yelling, or screaming) | 0/1 |

| Verbal Resistance (e.g., “I don’t want it”, “Stop!”) | 0/1 | |

| Requesting emotional or physical support (e.g., “can you hold my hand?”, “hold me!”) | 0/1 | |

| Information seeking (e.g., “Why do I need it?”, “will it hurt?”, “when will it end?”) | 0/1 | |

| Verbal expression of fear (e.g., “that looks scary”, “I’m afraid of needles”) | 0/1 | |

| Verbal expression of pain (e.g., “oww!”, “that hurts!”, “it stings”) | 0/1 | |

| Other (specify) | 0/1 | |

| N/A (no distress behaviors represented) | 0/1 | |

Parent/peer/sibling: | Restraint of character receiving needle (e.g., being held down to exam table, being held too tight by another character; this does NOT include being held in a gentle hug) | 0/1 |

| Simplified reassurance and/or false suggestion (e.g., “don’t worry”, “it’s/you’re okay”, “it won’t hurt”, “it will be fine”) even if followed by helpful/evidence-based information | 0/1 | |

| Exaggerated or scary written descriptions of the needle and/or procedure (e.g., “the giant needle poked her arm”) | 0/1 | |

| Ominous or scary visual depictions (e.g., unrealistically large needle). If 1 in this category, specify rating of the book on a 1–10 NRS. | 0/1 | |

| Ominous or scary visual depictions RATING the book as a whole. 1–3: mildly scary or ominous 4–6: moderately scary or ominous 7–10: highly scary or ominous Code based on how ominous or scary a child would find the book as a whole. Do NOT rate each scary picture in the book. Rate based on the scariness of pictures in the book, NOT on the quantity of scary pictures. (i.e., a book with only one highly scary picture would get a rating higher than a book with multiple mildly scary books). | 1–10 | |

| Criticism (i.e., negatively evaluating character receiving the needle; e.g., “brave kids don’t cry”, “Why are you crying so much?”, “You didn’t use your breathing like I told you to”) | 0/1 | |

| Apology (i.e., verbalization of sorrow; e.g., “I’m sorry we have to do this”, “I wish I didn’t have to hurt you”, “we don’t like doing this either”) | 0/1 | |

| Other (specify) | 0/1 | |

| N/A (No distress promoting behavior) | 1 | |

| No | 0 |

| Yes (describe briefly) | 1 |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Coding scheme for supplementary adult material.

Table A3.

Coding scheme for supplementary adult material.

| # | Category | Notes | If Yes: | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Definition/Explanation of Needle Fear | A definition, description, or explanation of the fear of needle procedures. Can include references to anxiety or phobia related to needle procedures. May also include references to the prevalence of needle fear. | 0—No 1—Yes | If yes: 0—Seems inaccurate 1—Seems accurate (Please Describe) ________ | |

| 2 | Vaccination Info–How vaccines work | A description or explanation of how vaccines work (e.g., what is in vaccines, how they build immunity, they keep you from getting sick, etc.). Does not include how they work on a community level (i.e., community/herd immunity or limiting spread of disease). | 0—No 1—Yes | If yes: 0—Seems inaccurate 1—Seems accurate (Please Describe) ___________ | |

| 3 | Vaccination Info–Community/Herd Immunity | A description or explanation of community/herd immunity (i.e., by getting vaccinated, you are protecting others). This includes mention of how vaccines prevent the spread of infectious diseases in communities. | 0—No 1—Yes | If yes: 0—Seems inaccurate 1—Seems accurate (Please Describe) ___________ | |

| 4 | Vaccination Info-Other | Other information specific to vaccinations that refers to their importance or function (e.g., history of vaccines, how many vaccines are required, etc.) | 0—No 1—Yes | If yes: 0—Seems inaccurate 1—Seems accurate (Please Describe) ___________ | |

| 5 | Visualization/Guided Imagery | Refers to using mental visualization or imagination as a helpful strategy for needle fear (e.g., picture leaves floating down a stream in a forest) | 0—No 1—Yes | ||

| 6 | Rewards | Refers to providing children with a desirable item or experience following successful completion of a needle procedure (e.g., ice cream, new toy, sticker, etc.) | 0—No 1—Yes | ||

| 7 | Expertise | Writer or writers of the book have expertise in guidance. This could include an advanced graduate degree (MD, PhD, RN, MSW, PharmD, etc.), clinical experience (e.g., work with children with needle fear), or lived experience (e.g., parent of child with needle fear). | 0—No Expertise described 1—No relevant expertise 2—Yes, relevant expertise | If yes, please describe expertise (e.g., pediatric nurse, mom of child with NF, etc.) | |

| Clinical Practice Guidelines | |||||

| Category | Code any Accurate Mention of: | Reference | Y/N | If Yes, Describe | |

| 8 | Avoid aspiration (for vaccinations only) | Aspiration should not be used during intramuscular vaccine injections as the technique can increase pain. | [13] | 0—No 1—Yes | |

| 9 | Most painful needle last | As some vaccines are more painful than others, and many children receive multiple injections at a single visit, the most painful needle should be administered last. | [13] | 0/1 | |

| 10 | Positioning-Sitting upright | It is recommended that during the needle, children ages three and older sit upright rather than be lying in a supine position. This positioning has been shown to decrease fear and observed distress in children. | [13,14] | 0/1 | |

| 11 | Avoid restraining the child. | Forcibly restraining a child during the needle is advised against as it may increase the child’s fear. | [13] | 0/1 | |

| 12 | Muscle Tension | Muscle tension is recommended for children ages seven and above with a history of fainting. This occurs immediately before and during the needle | [13,16] | 0/1 | |

| 13 | Combination of Cold & Vibration (Buzzy) | The Buzzy Device, which applies vibration and cold above the needle insertion site immediately before and during the needle has been shown to be a promising intervention for reducing procedural pain and anxiety. | [18] | 0/1 | |

| 14 | Using topical anesthetics | Topical anesthetics block the transmission of pain signals from the skin (McLure & Rubin, 2005) and are recommended for children ages twelve and below. They can be in the form of numbing creams, gels, or patches. | [13] | 0/1 | |

| 15 | Clinician Education | It is recommended that clinicians administering the needle be educated on implementing needle pain and fear management strategies before the day of the needle | [13] | 0/1 | If yes, Describe: ________ |

| 16 | Parent Education | Educating parents on how to mitigate their child’s pain and fear both before and on the day of needle is recommended before and on the day of the needle to increase use of interventions during the needle | [13] | 0/1 | If yes, Describe: ________ |

| 17 | Child Education | Children ages 3 and up should be provided procedural (e.g., what will happen?) and sensory (e.g., how will it feel?) information and be taught how to use coping strategies. Such information should mostly be provided in advance. On the day of the procedure, children should be provided with neutral information and coping strategies. | [13] | 0/1 | If yes, Describe: ________ |

| 18 | Parent Presence | Parents of children aged 10 and younger should be present during the child’s needle. | [13] | 0/1 | |

| 19 | Neutral Wording to Signal Procedure | It is recommended to use neutral wording to signal the impending procedure to children (e.g., “here we go!”). | [13] | 0/1 | |

| 20 | Avoid Reassurance & False Suggestion | Repeated and simplified reassurance and false suggestions (e.g., “don’t worry”, “it’s okay”, “it won’t hurt”) can increase children’s distress and pain. | [13] | 0/1 | |

| 21 | Distraction | It is recommended that distraction be used to draw children’s attention away from the needle. For children ages 3 to 12, verbal, video, and music distractions are recommended. Does NOT include breathing interventions (See Code #22) | [13,17] | 0/1 | If yes, Describe: ________ |

| 22 | Breathing with Distraction | Breathing interventions, such as coughing, are recommended against. Instead, it is suggested that children breathe with a toy distraction during the needle (e.g., pinwheel, bubbles, etc.). | [13,17] | 0/1 | If yes, Describe: _______ |

| 23 | Exposure-based therapy (EBT) | For children ages 7 and above with high levels of needle fear, EBT is recommended. In fact, EBT is considered the gold standard treatment for specific phobias such as blood-injury injection phobia. | [13,15] | 0/1 | If yes, Describe: _______ |

| 24 | Applied Tension | For children ages 7 and above with high levels of needle fear and a history of fainting, applied tension is recommended rather than exposure-based therapy on its own. | [13,15] | 0/1 | |

References

- McMurtry, C.M.; Riddell, R.P.; Taddio, A.; Racine, N.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T.; Shah, V. Far from “Just a Poke”: Common Painful Needle Procedures and the Development of Needle Fear. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, S3–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Health Agency of Canada Provincial and Territorial Immunization Information—Canada.Ca. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/provincial-territorial-immunization-information.html (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Taddio, A.; Ipp, M.; Thivakaran, S.; Jamal, A.; Parikh, C.; Smart, S.; Sovran, J.; Stephens, D.; Katz, J. Survey of the Prevalence of Immunization Non-Compliance Due to Needle Fears in Children and Adults. Vaccine 2012, 30, 4807–4812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, L.D.; Calmes, D.P.; Bazargan, M.N. The Impact of Literacy Enhancement on Asthma-Related Outcomes among Underserved Children. J. Natl. Med. Assoc. 2008, 100, 892–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.C. Representations of Illness, Injury, and Health in Children’s Picture Books. Child. Health Care 2006, 35, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyches, T.T.; Prater, M.A. Characterization of Developmental Disability in Children’s Fiction. Div. Autism Dev. Disabil. 2005, 40, 202–216. [Google Scholar]

- Taddio, A.; McMurtry, C.M.; Logeman, C.; Gudzak, V.; de Boer, A.; Constantin, K.; Lee, S.; Moline, R.; Uleryk, E.; Chera, T.; et al. Prevalence of Pain and Fear as Barriers to Vaccination in Children—Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Vaccine 2022, 40, 7526–7537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J.G. Needle Phobia: A Neglected Diagnosis. J Fam Pract 1995, 41, 169–175. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; Volume 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T.; McGrath, P.J.; Klein, R.M.; Stewart, S.H. The Role of State Anxiety in Children’s Memories for Pain. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2012, 37, 567–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T.; McGrath, P.J.; Klein, R.M.; Stewart, S.H. The Influence of Children’s Pain Memories on Subsequent Pain Experience. Pain 2012, 153, 1563–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, D.R.; Elia, S.; Perrett, K.P. Immunizations under Sedation at a Paediatric Hospital in Melbourne, Australia from 2012–2016. Vaccine 2018, 36, 3681–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddio, A.; McMurtry, C.M.; Shah, V.; Riddell, R.P.; Chambers, C.T.; Noel, M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Rogers, J.; Bucci, L.M.; Mousmanis, P.; et al. Reducing Pain during Vaccine Injections: Clinicalpractice Guideline. CMAJ 2015, 187, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddio, A.; Shah, V.; McMurtry, C.M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Ipp, M.; Riddell, R.P.; Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T. Procedural and Physical Interventions for Vaccine Injections Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, S20–S37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurtry, C.M.; Taddio, A.; Noel, M.; Antony, M.M.; Chambers, C.T.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Pillai Riddell, R.; Shah, V.; MacDonald, N.E.; Rogers, J.; et al. Exposure-Based Interventions for the Management of Individuals with High Levels of Needle Fear across the Lifespan: A Clinical Practice Guideline and Call for Further Research. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016, 45, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurtry, C.M.; Noel, M.; Taddio, A.; Antony, M.M.; Asmundson, G.J.G.; Riddell, R.P.; Chambers, C.T.; Shah, V.; MacDonald, N.E.; Rogers, J.; et al. Interventions for Individuals with High Levels of Needle Fear: Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials and Quasi-Randomized Controlled Trials. Clin. J. Pain 2015, 31, S109–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birnie, K.A.; Noel, M.; Chambers, C.T.; Uman, L.S.; Parker, J.A. Psychological Interventions for Needle-Related Procedural Pain and Distress in Children and Adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballard, A.; Khadra, C.; Adler, S.; Trottier, E.D.; Le May, S. Efficacy of the Buzzy Device for Pain Management during Needle-Related Procedures: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. J. Pain 2019, 35, 532–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grös, D.F.; Antony, M.M. The Assessment and Treatment of Specific Phobias: A Review. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2006, 8, 298–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolitzky-Taylor, K.B.; Horowitz, J.D.; Powers, M.B.; Telch, M.J. Psychological Approaches in the Treatment of Specific Phobias: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2008, 28, 1021–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foa, E.; McLean, C. The Efficacy of Exposure Therapy for Anxiety-Related Disorders and Its Underlying Mechanisms: The Case of OCD and PTSD. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2016, 12, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLenon, J.; Rogers, M.A.M. The Fear of Needles: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heath, M.A.; Sheen, D.; Leavy, D.; Young, E.; Money, K. Resource to Facilitate Emotional Healing and Growth. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2016, 26, 563–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manworren, R.C.; Woodring, B. Evaluating Children’s Literature as a Source for Patient Education. Pediatr. Nurs. 1998, 24, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewis, K.M.; Amatya, K.; Coffman, M.F.; Ollendick, T.H. Treating Nighttime Fears in Young Children with Bibliotherapy: Evaluating Anxiety Symptoms and Monitoring Behavior Change. J. Anxiety Disord. 2015, 30, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poling, D.A.; Hupp, J.M. Death Sentences: A Content Analysis of Children’s Death Literature. J. Genet. Psychol. 2008, 169, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcom, N.L. Images of Heaven and the Spiritual Afterlife: Qualitative Analysis of Children’s Storybooks about Death, Dying, Grief, and Bereavement. OMEGA J. Death Dying 2011, 62, 51–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugge, K.E.; Helseth, S.; Darbyshire, P. Parents’ Experiences of a Family Support Program When a Parent Has Incurable Cancer. J. Clin. Nurs. 2009, 18, 3480–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlinson, S.C.; Short, J.A. The Representation of Anaesthesia in Children’s Literature*. Anaesthesia 2007, 62, 1033–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, Y.; Kuo, H.C.; Lee, H.C.; Yiin, S.J. Developing a Medical Picture Book for Reducing Venipuncture Distress in Preschool-Aged Children. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2017, 23, e12569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, C.T. From Evidence to Influence: Dissemination and Implementation of Scientific Knowledge for Improved Pain Research and Management. Pain 2018, 159, S56–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, N.E.; Chambers, C.T.; Parker, J.A.; Aubrey, E.; Jordan, I.; Richards, D.P.; Marianayagam, J.; Ali, S.; Campbell, F.; Finley, G.A.; et al. Bridging the Gap: Identifying Diverse Stakeholder Needs and Barriers to Accessing Evidence and Resources for Children’s Pain. Can. J. Pain 2022, 6, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garritty, C.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; King, V.J.; Hamel, C.; Kamel, C.; Affengruber, L.; Stevens, A. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group Offers Evidence-Informed Guidance to Conduct Rapid Reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 130, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamel, C.; Michaud, A.; Thuku, M.; Skidmore, B.; Stevens, A.; Garrity, C. Defining Rapid Reviews: A Systematic Scoping Review and Thematic Analysis of Definitions and Defining Characteristics of Rapid Reviews. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 129, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.; Langlois, E.; Straus, S. ; World Health Organization. Rapid Reviews to Strengthen Health Policy and Systems: A Practical Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jaaniste, T.; Hayes, B.; von Baeyer, C.L. Providing Children with Information about Forthcoming Medical Procedures: A Review and Synthesis. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 2007, 14, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, E.Y.; Carpenter, B.D.; Rieger, R.E. “what’s Wrong with Grandma?”: Depictions of Alzheimer’s Disease in Children’s Storybooks. Am. J. Alzheimers Dis. Other Demen. 2012, 27, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azano, A.P.; Tackett, M.; Sigmon, M. Understanding the Puzzle Behind the Pictures: A Content Analysis of Children’s Picture Books about Autism. AERA Open 2017, 3, 2332858417701682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lee, S.; Hu, Y.; Gao, H.; O’Connor, M. Talking about Maternal Breast Cancer with Young Children: A Content Analysis of Text in Children’s Books. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2015, 40, 609–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Connor, C.; Joffe, H. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2020, 19, 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, S.; Kyngäs, H. The Qualitative Content Analysis Process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, H.F.; Shannon, S.E. Three Approaches to Qualitative Content Analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005, 15, 1277–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blount, R.L.; Cohen, L.L.; Frank, N.C.; Bachanas, P.J.; Smith, A.J.; Manimala, M.R.; Pate, J.T.; Smith, S.; Bradberry, L.; Bridges, J.; et al. The Child-Adult Medical Procedure Interaction Scale-Revised: An Assessment of Validity 1. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 1997, 22, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anphalagan, S.; Anphalagan, S. Ahana Got A Vaccine! Independently Published: Traverse City, MI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lachapelle, B. Alpha Vaccination: An Animal Alphabet Vaccination Story; Lachapelle: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W.J.; Morco, Y. Betty’s Blood Test, 1st ed.; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Haynes, M.L. Bobby the Bulldog: Goes for a Blood Test; Haynes: Somerset, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Posner-Sanchez, A. Boomer Gets His Bounce Back (Disney Junior: Doc McStuffins); Golden/Disney: Glendale, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beny, K.; Heydenrych, E.; Gicovi, E. Brave Bora: A Story about Being Brave and Getting a Needle! 1st ed.; Mann, D., Ed.; Book Dash: Salt River, MO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Spray, M.; Leonova, V. Brave Jake: A Story about Being BRAVE at the Doctor; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Spray, M.; Leonova, V. Brave Kayla: A Story about Being BRAVE at the Doctor; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Badillos, J.; Laidlaw, J. Did You Know That Shots Give You SUPERPOWERS?: A Short Story to Help Kids Understand How Vaccines Help Keep Them Healthy. Badillos: Yakima, WA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers-McDaniel, T. Don’t Be Afraid (Mrs. Christian’s Daycare); Teaching Parables: Trussville, AL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zavod, D.; Orban, O.D. Ridiculopickulopot and the Shot; Matthew Zavod: Woodland, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Chen, T. Ellie Is Vaccinated: A Story about Getting the COVID-19 Vaccine; Ellie Adventures LLC: Frisco, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, H.E. Facing Your Fear of Shots; Pebble Books: Rocheport, MO, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, J.E. Fish Are Not Afraid of Doctors; Penguin Workshop: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- London, J.; Remkiewicz, F. Froggy Goes to the Doctor; Puffin Book: London, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Artis, K.E. Gracie Gets a Shot; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Baird, C.P.; Weese, L.; Maguire, S. How Do Shots Work?: Come with Us on an Adventure to the Doctor’s Office and Learn about Shots! Baird: Melbourne, Australia, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, S. It’s Time for Your Checkup: What to Expect When Going to a Doctor Visit; CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform: Scotts Valley, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, D.; Sanders, E. JJ’s Shot to Save the World: How to Become a Germ-Fighting Hero; Sanders Publishing: Columbia, SC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, A. Jojo Wonders, What Are Vaccines. 2021. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Jojo-wonders-what-are-vaccines/dp/B08VCJ4XTW (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Koffsky, A. Judah Maccabee Goes to the Doctor: A Story for Hanukkah; Apples & Honey Press: Springfield, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Block, L.; Block, A.; Rahmalia, D. Kelly Gets a Vaccine: How We Beat Coronavirus: How We Beat Coronavirus; Blockstar Publishing: Glendale, AZ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner, M.; Almora, K. Kelsey Hates the Needle; Newman Springs Publishing, Inc.: Red Bank, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bennet, G. Lions Aren’t Scared of Shots: A Story for Children about Visiting the Doctor; Magination Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, L. Little Shots for Little Tots; FriesenPress: Manitoba, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Audet, N.; Villeneuve, M. Maya Visits Her Doctor: Vaccination; Dr. Nicole Publishing: Laval, QC, Canada, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramani, D. Miss Violet Vaccine; Ramani: Rondweg, MC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Krayden, S. Needle Day. 2015. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Needle-Day-Shirley-Krayden-ebook/dp/B00V2S7WI2/ref=sr_1_2?crid=EMPYXSR6CRLW (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Scarry, R. Richard Scarry’s Nicky Goes to the Doctor; Random House Books for Young Readers: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zelinger, L. Please Explain Vaccines to Me: Because I HATE SHOTS! 1st ed.; Loving Healing Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Diesen, D.; Hanna, D. Pout-Pout Fish: Goes to the Doctor (A Pout-Pout Fish Paperback Adventure); Farrar, Straus and Giroux (BYR): New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dobler, S. Puppy Needs a Vaccine: Helping Kids Understand COVID-19 Vaccinations; Independently Published: Traverse City, MI, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, J.; Simone, L. Sammy the Shot: Preparing Children for Vaccinations; Senders Pediatrics: South Euclid, OH, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. Sofia and the Shot; Fuller Stories Inc.: Thornton, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- George, A.H.; Squirrel, A. Story of Vaccines. 2022. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Story-Vaccines-Childrens-biology-book-ebook/dp/B0B1BGDTLJ (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Flowers, M. Thank You for Getting Your Shots; Flowers: Detroit, MI, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Berenstain, S.; Berenstain, J. The Berenstain Bears Go to the Doctor; Random House Books for Young Readers: New York, NY, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Haider, A. The Boy Who Overcame His Fear of Needles! Haider: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, D.; Aaron, K. Ethan, Mia, and the Amazing Vaccine; Friedman: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, E.; Watson, L. The Measly Virus, 1st ed.; Watters Publishing: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dagostino, H.; Dagostino, K.; Gurido, L. The Pinch Pixie: Conquering Vaccine Fear with a Healthy Dose of Magic and a Pinch of Science; Dagostino: Nashville, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, E. The Real Life Super Power: A Creative Story for Children to Help Boost Their Bravery about Getting Shots at the Doctor’s Office; Maxwell: Nashville, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Singer, J. The Scared Sheep Needed a Shot. 2021. Available online: https://www.amazon.com/Scared-Sheep-Needed-Shot/dp/B092XBKD6S (accessed on 21 March 2023).

- Posard, E. The Shots Book: A Little Brother’s Superhero Tale; Posard: San Anselmo, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lardner, B. Vicky Gets a Vaccine; Pagemaster Publishing: Edmonton, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Knolls, B.; Shea, R.A. When a Shot Meant a Lot: A Story for Kids about the COVID-19 Vaccine; Knolls: New Castle, DE, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Feuti, N. Who Needs a Checkup?: An Acorn Book (Hello, Hedgehog #3); Scholastic Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, A.; Moldovan, I.; Jacons, K. You Are So Brave!: Ellie and Leo Go to the Doctor; Karen Jacobs: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goralnick, E.; Kaufmann, C.; Gawande, A.A. Mass-Vaccination Sites—An Essential Innovation to Curb the COVID-19 Pandemic. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, N.E.; Eskola, J.; Liang, X.; Chaudhuri, M.; Dube, E.; Gellin, B.; Goldstein, S.; Larson, H.; Manzo, M.L.; Reingold, A.; et al. Vaccine Hesitancy: Definition, Scope and Determinants. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4161–4164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, G.J.; Ewing-Nelson, S.R.; Mackey, L.; Schlitt, J.T.; Marathe, A.; Abbas, K.M.; Swarup, S. Semantic Network Analysis of Vaccine Sentiment in Online Social Media. Vaccine 2017, 35, 3621–3638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalley, J.S.; Morrongiello, B.A.; McMurtry, C.M. Children’s Perspectives on Outpatient Physician Visits: Capturing a Missing Voice in Patient-Centered Care. Children 2021, 8, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, O.; Wrzeciono, A.; Rutkowska, A.; Guzik, A.; Kiper, P.; Rutkowski, S. Virtual Reality Interventions for Needle-Related Procedural Pain, Fear and Anxiety—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 3248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setiawati, S. Distracting Effect of Watching Animation on Children’s Anxiety While Vaccination. Int. J. Med. Sci. Clin. Res. Stud. 2022, 2, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taddio, A.; McMurtry, C.M.; Bucci, L.M.; MacDonald, N.; Ilersich, A.N.T.; Ilersich, A.L.T.; Alfieri-Maiolo, A.; deVlaming-Kot, C.; Alderman, L.; Freedman, T.; et al. Overview of a Knowledge Translation (KT) Project to Improve the Vaccination Experience at School: The CARDTM System. Paediatr. Child Health 2019, 24, S3–S18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, D.; Larocque, C.; Reszel, J.; Harrold, J.; Aubertin, C. Be Sweet to Babies during Painful Procedures. Adv. Neonatal Care 2017, 17, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddio, A.; Morrison, J.; Gudzak, V.; Logeman, C.; McMurtry, C.M.; Bucci, L.M.; Shea, C.; MacDonald, N.E.; Yang, M. Integration of CARD (Comfort Ask Relax Distract) for COVID-19 Community Pharmacy Vaccination in Children: Effect on Implementation Outcomes. Can. Pharm. J. /Rev. Pharm. Can. 2022, 156, 17151635221139783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taddio, A.; Gudzak, V.; Jantzi, M.; Logeman, C.; Bucci, L.M.; MacDonald, N.E.; Moineddin, R. Impact of the CARD (Comfort Ask Relax Distract) System on School-Based Vaccinations: A Cluster Randomized Trial. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2802–2809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, M.S.; MacDonald, N.E.; McMurtry, C.M.; Balakrishnan, M.R.; Heininger, U.; Menning, L.; Benes, O.; Pless, R.; Zuber, P.L.F. Immunization Stress-Related Response—Redefining Immunization Anxiety-Related Reaction as an Adverse Event Following Immunization. Vaccine 2020, 38, 3015–3020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurtry, C.M. Managing Immunization Stress-Related Response: A Contributor to Sustaining Trust in Vaccines. Can. Commun. Dis. Rep. 2020, 46, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).