A Bird with No Name Was Born, Then Gone: A Child’s Processing of Early Adoption through Art Therapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Adoption as a Traumatic Event

1.2. Adoption as a Psycho-Socio-Developmental Challenge

1.3. Art Therapy with Children Who Have Been Adopted

1.4. Something to Hold on to: The Importance of Metaphors and Transitional Objects

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study as a Methodology

2.2. Case Background

3. Case Illustration (Results)

3.1. Into the Pain: Forming Attachments despite Failures

3.2. From Deep Inside: Making Messes, Tolerating and Exploring Their Meaning

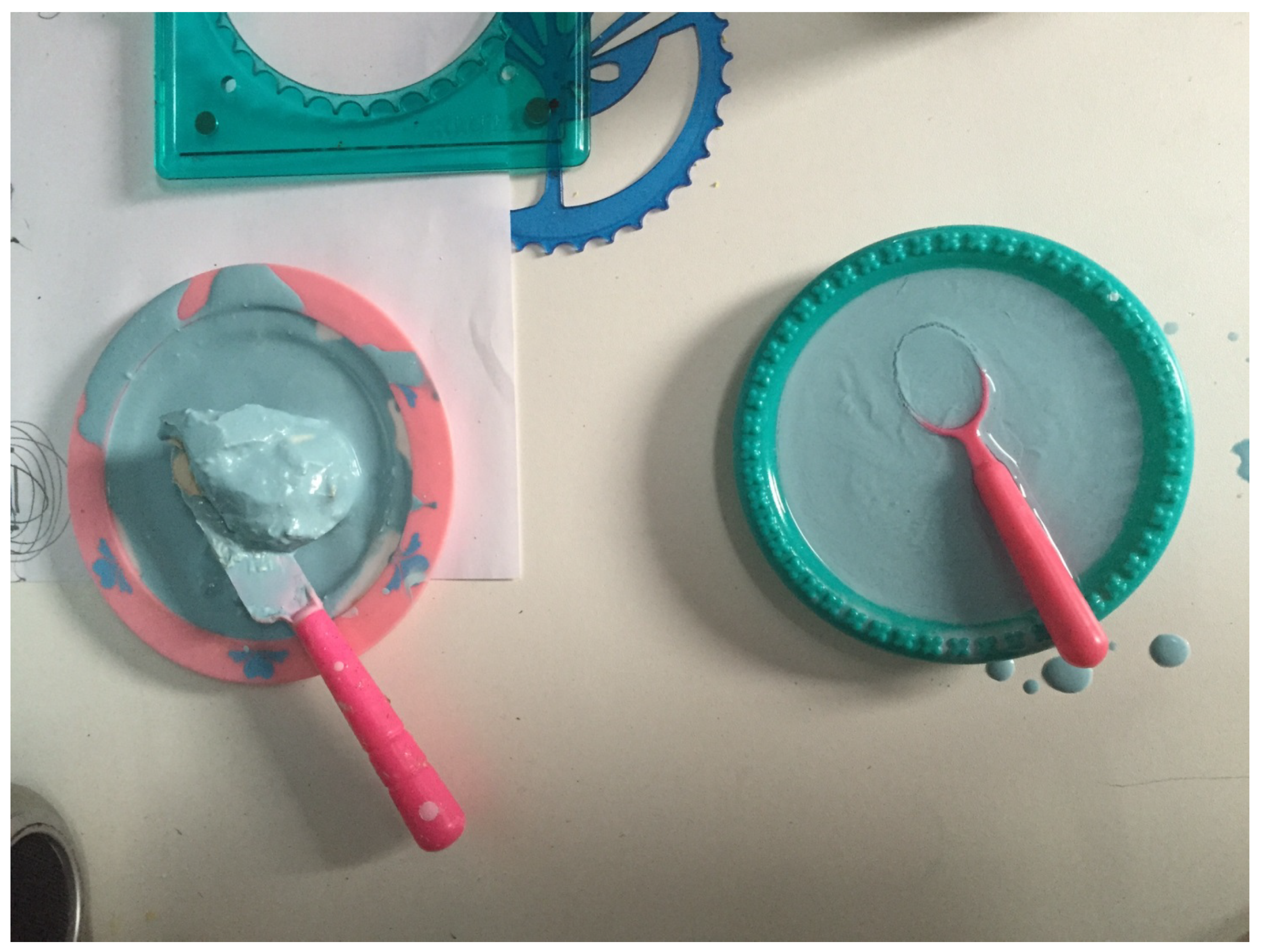

3.3. Art as Nurturing

3.4. Emerging: Supporting Connection and Validation with Parents

3.5. Individuating/Separating: Creative Experiments with Separating While Staying Connected

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinz, L. Art Therapy Approaches with Unbonded Children and Adolescents. In Creative Arts Therapies Approaches in Adoption and Foster Care; Betts, J.D., Ed.; Thomas: Springfield, IL, USA, 2003; pp. 191–213. ISBN 0398073880. [Google Scholar]

- Adoptionnetwork.com. US Adoption Statistics. 2022. Available online: https://adoptionnetwork.com/adoption-myths-facts/domestic-us-statistics (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Trends in Foster Care and Adoption. AFCARS, FY 2010–2019. Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/resource/trends-in-foster-care-and-adoption (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Robertson, B. Drawing a Blank: Art Therapy for adolescent adoptees. Am. J. Art Ther. 2001, 39, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Malloy, J.N. Post-ASFA Permanency Planning for Children in Foster Care: Clinical and Ethical Considerations for Art Therapists. Art Ther. 2017, 34, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henley, D. Attachment disorders in post-institutionalized adopted children: Art therapy approaches to reactivity and detachment. Arts Psychother. 2005, 32, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, S.J. Describing the Post-Adoption Mental Health Support Needs of Adoptive Families: Implications for Occupational Therapy. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 2022, 38, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, P.A.; Kline, A. Trauma through a Child’s Eyes: Awakening the Ordinary Miracle of Healing; North Atlantic Books: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2006; ISBN 10.1556436300. [Google Scholar]

- Klorer, P.G. Expressive Therapy with Severely Maltreated Children: Neuroscience Contributions. J. Am. Art Ther. Assoc. 2005, 22, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M. Factors Effecting Post-Permanency Adjustment for Children in Adoption or Guardianship Placements: An Ecological Systems Analysis. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2016, 66, 131–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyzer, K. A Literature Review of Art Therapy with Children 0–6 Years and Their Families; Publication of the Infants’ Home, Ashfield/University of Western Sydney, Research Centre for Social Justice and Social Change: Sydney, Australia, 2008; pp. 1–43. [Google Scholar]

- Proulx, L. Strengthening Emotional Ties through Parent-Child-Dyad Art Therapy: Interventions with Infants and Preschoolers; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 2003; ISBN 1843107139. [Google Scholar]

- Case, C. Observations of Children Cutting up, Cutting out and Sticking down. Int. J. Art Ther. 2006, 11, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.E. Fostering Attachment in the Face of Systemic Disruption: Clinical Treatment with Children in Foster Care and the Adoption and Safe Families Act. Smith Coll. Stud. Soc. Work. 2011, 81, 62–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malchiodi, C.A. Art Therapy, Attachment, and Parent–Child Dyads. In Creative Arts and Play Therapy for Attachment Problems; Malchiodi, C.A., Crenshaw, D.A., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 52–66. ISBN 1462523706. [Google Scholar]

- American Art Therapy Association. About Art Therapy. Available online: https://arttherapy.org/about-art-therapy/ (accessed on 15 March 2023).

- Hinz, L.D. Expressive Therapies Continuum: Use and Value Demonstrated with Case Study (Le continuum des thérapies par l’expression: étude de cas démontrant leur utilité et valeur). Can. Art Ther. Assoc. J. 2015, 28, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drewes, A.A. Helping Foster Care Children Heal from Broken Attachments. In Creative Arts and Play Therapy for Attachment Problems; Malchiodi, C.A., Crenshaw, D.A., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 197–214. ISBN 1462523706. [Google Scholar]

- Metzl, E.S. Art Is Fun, Art Is Serious Business, and Everything in between: Learning from Art Therapy Research and Practice with Children and Teens. Child 2022, 9, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, F. The Making of Mess in Art Therapy: Attachment, Trauma and the Brain. Int. J. Art Ther. 2004, 9, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, E.; Rubin, L. Counter-Transference Play: Informing and Enhancing Therapist Self-Awareness through Play. Int. Play. Ther. 2005, 14, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, C. (Ed.) . Family Art Therapy: Foundations of Theory and Practice; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2011; ISBN 97811389969544. [Google Scholar]

- Lareau, A. Unequal Childhoods: Class, Race, and Family Life, 2nd ed.; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011; ISBN 978-0-520-27142-5. [Google Scholar]

- Case, C. Authenticity and Survival: Working with Children in Chaos. Inscape 2003, 8, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, C. Imagining Animals: Art, Psychotherapy and Primitive States of Mind; Routledge: Abingdon-on-Thames, UK, 2005; ISBN 9781583919583. [Google Scholar]

- Malchiodi, C.A. Creative Arts Therapy Approaches to Attachment Issues. In Creative Arts and Play Therapy for Attachment Problems; Malchiodi, C.A., Crenshaw, D.A., Eds.; Guilford: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 3–17. ISBN 1462523706. [Google Scholar]

- Gavron, T.; Mayseless, O. Creating art together as a transformative process in parent-child Relations: The therapeutic aspects of the Joint Painting Procedure. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao Wong, A.C.; Hung Ho, R.T. Applying Joint Painting Procedure to Understand Implicit Mother–Child Relationship in the Context of Intimate Partner Violence. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2022, 21, 16094069221078759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, E.; Bostelmann, E. Social Media and Art Therapy Services: Adapting and Evolving. Art Ther. 2022, 39, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Johns, S.; Romanik, L.; Glasscock, V. Response Art to Develop a Social Justice Stance for Art Therapists. Art Ther. 2022, 39, 108–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karcher, O.P. Sociopolitical Oppression, Trauma, and Healing: Moving toward a social justice art therapy framework. Art Ther. 2017, 13, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapitan, L. Social Action in Practice: Shifting the ethnocentric lens in cross-cultural art therapy encounters. Art Ther. 2015, 32, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Metzl, E.S. A Bird with No Name Was Born, Then Gone: A Child’s Processing of Early Adoption through Art Therapy. Children 2023, 10, 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10040751

Metzl ES. A Bird with No Name Was Born, Then Gone: A Child’s Processing of Early Adoption through Art Therapy. Children. 2023; 10(4):751. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10040751

Chicago/Turabian StyleMetzl, Einat S. 2023. "A Bird with No Name Was Born, Then Gone: A Child’s Processing of Early Adoption through Art Therapy" Children 10, no. 4: 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10040751

APA StyleMetzl, E. S. (2023). A Bird with No Name Was Born, Then Gone: A Child’s Processing of Early Adoption through Art Therapy. Children, 10(4), 751. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10040751