Abstract

Neighborhoods have been the focus of health researchers seeking to develop upstream strategies to mitigate downstream disease development. In recent years, neighborhoods have become a primary target in efforts to promote health and resilience following deleterious social conditions such as the climate crisis, extreme weather events, the global pandemic, and supply chain disruptions. Children are often the most vulnerable populations after experiencing unexpected shocks. To examine and describe conceptually the construct of Neighborhood Resilience, we conducted a comprehensive scoping review using the terms (“resilience” or “resiliency” or “resilient”) AND (“neighborhood”), utilizing MEDLINE (through PubMed) and CINAHL (through EBSCOhost) databases, to assess overall neighborhood themes that impact resilience. A total of 57 articles were extracted that met inclusion criteria. Extracted characteristics included study purpose, country of origin, key findings, environmental protective/risk factors. The analysis revealed a positive relationship between neighborhood resource density, neighborhood resiliency, and individual resiliency. This study reports the finding for studies with a population focus of pre-school age and school age children (1.5–18 years of age). Broadly, we identified that the primary goals regarding neighborhood resilience for childhood can be conceptualized as all activities and resources that (a) prevent trauma during childhood development and/or (b) mitigate or heal childhood trauma once it has occurred. This goal conceptually encompasses antecedents that increase protective factors and reduces risk factors for children and their families. This comprehensive look at the literature showed that a neighborhood’s ability to build, promote, and maintain resiliency is often largely dependent on the flexible resources (i.e., knowledge, money, power, prestige, and beneficial social connections) that are available.

1. Introduction

Recent global events that have impacted the widespread childhood experience for children include the 2008 global financial crisis [1], COVID-19 pandemic [2], loss of land and ecosystems [3], increased vector-borne illnesses [4,5], and agricultural instability [6]. Children and adolescents are especially vulnerable to these stressors for a variety of reasons [7,8]. The ability of a child or adolescent to appropriately overcome the stressors surrounding them is in part dependent on the strength and ability of the systems in which they are a part [9]. This includes neighborhoods. Social determinants of health and mental health may now include factors such as socioeconomic status and resource availability [10]. For example, critical access to healthcare services is often limited in underserved or disadvantaged communities. Similarly, ecological determinants of health include clean water and food access, along with neighborhood and community abilities to overcome the consequences of natural disasters [11].

Neighborhoods are a promising setting to promote health and resilience [12,13]. Neighborhood disadvantages have been associated with an increased overall stress burden experienced by residents of those neighborhoods. Conversely, residence in affluent neighborhoods is associated with low to normal stress burdens [12]. This is an especially important consideration when working with children and adolescents after exogenous shocks are experienced [14,15]. The collective efficacy experienced at the neighborhood level may be key to building the resilience capacity of the children and families who live there [16]. Despite the need to address upstream factors that impact health, prevention programs too often focus on individual-level health behaviors and risk factors [17,18].

This scoping review aims to develop a clear conceptual definition of resilience in the context of neighborhoods and children. The secondary aim of this study is to identify key risk and protective factors to be considered when developing neighborhood-level pediatric health promotion strategies. To address these aims, we comprehensively reviewed the literature on resilience in the neighborhood setting.

2. Materials and Methods

Scoping reviews are preferable to systematic reviews when study objectives relate to the clarification of key concepts and the identification of dimensions related to a concept [19]. As such, due to the exploratory nature of this research inquiry, a scoping review was chosen as the methodology for synthesizing the literature. Utilizing the scoping review framework described by Arksey and O’Malley (2005), we (a) identified our research inquiry, (b) identified search parameters, (c) defined the study selection, (d) charted the data, and (e) collated, summarized, and reported the results [20].

2.1. Search Terms, Sources of Data, and Inclusion Criteria

On 5 July 2022, we conducted searches using the search terms [(“resilience” or “resiliency” or “resilient”) AND (“neighborhood”)], utilizing MEDLINE (through PubMed) and CINAHL (through EBSCOhost) databases. Inclusion criteria included English language publication in a peer-reviewed journal and data collection involving human subjects. Although our search protocol focused on the general concept of neighborhood resilience, studies reported in this review were limited to those related to a pediatric population (pre-school and school-age children, e.g., children aged 1.5–18 years old). Articles were included if pediatric population and resilience were addressed in the contexts of neighborhoods. No date range was defined for this study (all studies through 5 July 2022 were considered).

The concept of neighborhood was not predefined by the reviewer team. Of interest to us was how the construct of “neighborhood” was conceptualized by the authors of the reviewed articles and the populations being studied [21]. Results were imported into Covidence™ [22], a software program that facilitates synthesis reviews. PROSPERO does not register scoping reviews; consequently, this study was not registered. All study procedures adhered to the PRISMA-ScR checklist for scoping reviews [23].

As part of our a priori protocol, we included any study that provided insight into the antecedents, attributes, or consequences of neighborhood resilience. Quality appraisal on each article was not conducted due to the exploratory conceptual focus. Study characteristics that were extracted included authors, year of publication, country in which the research was conducted, title, study design method, study purpose, population, sample size, and key findings.

2.2. Data Analysis Process

Two authors (SB and KD) independently reviewed the articles to assess if the inclusion criteria were met and were blinded to voting until all reviews had been conducted. Voting and evaluation interrater reliability for each decision stage was carried out in Covidence™. Cohen’s Kappa was used to determine interrater reliability during the initial screening of title and abstract for inclusion/exclusion and full-text inclusion/exclusion phases. The authors reconciled any discrepancies in the inclusion and exclusion reviews through routine synchronous discussion via Zoom. Additionally, authors memo’ed and met routinely to discuss findings during the analysis and synthesis phase. Covidence™ software was used to standardize the extraction process conducted by SB, which was verified by KD and KWY. The results of the extraction process were exported for analysis and development (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics for full-text reviews from database search conducted on 5 July 2022 using the search terms [(“resilience” or “resiliency” or “resilient”) AND (“neighborhood”)].

3. Results

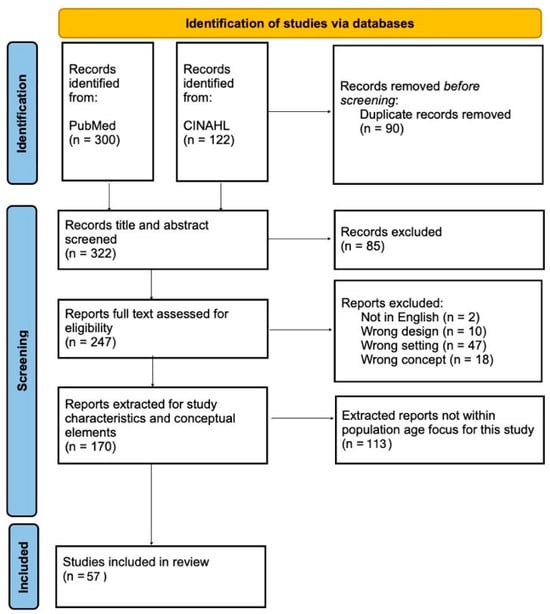

The initial search returned 422 articles with 90 duplications (Figure 1). Two authors independently screened the title and abstract of 332 articles and reviewed the full text of 247 articles. For the larger general search, which is beyond the scope of reporting in this manuscript, 170 articles met the inclusion criteria and were extracted for analysis. Included articles were published between 1994 and 2022. The primary reasons for excluding articles during the full-text review phase were because they did not focus on neighborhoods (N = 47) or resilience (N = 18). Articles were excluded if they were not a study (N = 10) or published in English (N = 2). All 170 articles were extracted for our larger neighborhood resilience analysis.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of database search conducted on 5 July 2022 using the search terms. [(“resilience” or “resiliency” or “resilient”) AND (“neighborhood”)].

To narrow the articles being reported for this manuscript, only 57 studies were retained for the narrowed inclusion criteria focusing on the pediatric population and pre-school age and school-age children (ages 1.5–18 years old).

3.1. Broad Themes

There was fair agreement between the reviewers for the title/abstract screening phase (Cohen’s κ = 0.39) and moderate agreement for the full-text reviews (κ = 0.47) between independent raters [81]. Broadly, the results suggest that neighborhood resilience for childhood can be conceptualized as all activities and attributes that (a) prevent trauma during childhood development and/or (b) mitigate or heal childhood trauma once it has occurred. This conceptually encompasses antecedents that increase protective factors and reduce risk factors for children and their families.

Authors of articles included in this study describe “skin-deep” resilience as the against-all-odds ability to rise above the traumas one has experienced in childhood [33]. Skin-deep resilience speaks to the phenomena where children of disadvantaged neighborhoods, through individual attributes such as conscientiousness and hard work, achieve external success such as high educational attainment or upward social economic mobility [82,83]. The individual attributes of high conscientiousness and productivity in work are correlated with less substance use and increased outward achievement, but these children also experience a higher prevalence of health conditions associated with cumulative “weathering” stress. Brody and Chen’s work is primarily focused on African–American youth. However, the weathering effect has also been noted in children who have experienced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) [84].

This concept of overcoming past trauma was addressed in the multiple studies that examined adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) [34,36,37,41,42,44,52,55,62,78,80]. In more recent years, the literature has cautioned that framing resilience as an individual attribute can re-victimize children who have been abused with the further critique that they lack the qualities needed to overcome their trauma. We identified studies on brain function as noteworthy [68], although, theoretically, we focused on studies regarding neighborhood and familial characteristics [29,30,31,32,43,47,49,50,53,56,70,71,74,75,77]. One study explored how an increase in resources contributes to positive childhood events (PCEs) [40].

We contrasted skin-deep resilience that is based on the attributes of an individual child and the potential of a deeper-rooted resilience that is supported across all the nested systems of a neighborhood. Two studies focused on environments that promote flourishing beyond the baseline and where access to flexible resources across all levels is crucial [28,58]. In these studies, the protective resilience that is provided through positive childhood experiences such as having a mentor, family resiliency, and networked community connections is discussed. Creating protective resilience was central to Breton’s (2001) work on neighborhood resilience. Breton posited that what makes a neighborhood resilient is social and physical resources that improve one’s ability to adapt. Initial resource availability and a state of equilibrium must be present, such that when disequilibrium occurs, whether by a disaster or similar event, resources may be tapped into to reinstate the equilibrium of the neighborhood [85]. Breton argues that this ability is dependent on resources and infrastructure and that policies that increase these resources must be protected.

After a review of the literature, we define the construct of neighborhood resilience as “the protective capacity of a neighborhood to restore itself, and promote adaption among citizens, after experiencing an adverse exogenous shock” [26,85]. The conceptualization of resilience and level of resilience addressed by reviewed articles can be found in Supplementary Table S1.

To aide conceptual exploration and refinement, notes on risk and protective factors are reported in Table 1. The findings can be thematically categorized into two groups: neighborhood advantages that exhibit a positive association with resilience and neighborhood disadvantages that demonstrate a negative association with resilience.

3.2. Neighborhood Advantages

Neighborhood advantages are all the protective factors that increase resilience for the citizens who live there. Within the context of promoting resilience among children, community connections emerged as a significant neighborhood advantage. Constructs such as neighborhood cohesion, collective efficacy, and neighborhood connectedness were identified as key factors. Neighborhood cohesion is defined as the degree to which neighbors are interconnected and supportive [64]. In neighborhoods with high collective efficacy, residents are more likely to take collective action on behalf of each other and the neighborhood as a whole [86,87]. Furthermore, neighborhood connectedness encompasses both the quality and quantity of relationships maintained among neighbors.

Predictably, neighborhoods that demonstrate collective efforts to increase resilience capacity and proactively prepare for the unforeseen serve as protective environments for children and families residing within them. Planning activities include assessing neighborhood resources and the availability of neighborhood services [88]. Other studies focused on developing a community understanding of resilience and how communities can prepare for future disasters [35,89] or hasten recovery post-disaster [90].

3.3. Neighborhood Disadvantages

Neighborhood disadvantages were conceptualized in this analysis as all risk factors that decreased the capacity for resilience and exhausted any banked capacity among citizens. The presence of disorder and perceived senses of being unsafe within a neighborhood are strongly associated with a decreased capacity for resilience. A primary goal in promoting resilience across the life-course is the prevention of childhood trauma. Neighborhood disorder and incivilities experienced in neighborhood spaces are clearly identified risk factors. Studies have consistently demonstrated that exposure to neighborhood violence [24] and perceived neighborhood disorder are associated with a decreased resilience capacity [48,69]. Similarly, perceived neighborhood incivilities decrease a neighborhood’s capacity for resilience. These incivilities include nuisance crimes [45,46].

4. Discussion

This study cataloged the multi-layered aspects of what makes a neighborhood resilient and how that resiliency can affect outcomes in children and adolescents. The analyzed studies highlight the effects of neighborhood stability and resource availability on individual health, wherein increased exposure to stressors and instability are linked to increased cumulative stress and chronic disease development. Given the significant influence of neighborhoods on health and wellness, it is imperative that neighborhood citizens recognize that an erosion of social capital occurs as resource availability is diminished [91]. Yet there are many neighborhood-level actions that can be taken that are not resource intensive but rather rely upon social capital and connectedness. Simple activities that engage neighbors in building social supports for each other and particularly for the children of the neighborhood will likely improve a sense of connectedness. One potential neighborhood action would be to collectively identify the risk factors and protective factors in their neighborhood. Once a consensus is built around identification, engaging in the superordinate goal of increasing the protective factors (flexible resources) in the neighborhood or mitigating risk would likely increase neighborhood resilience.

As a midrange theory, fundamental cause theory could explain this relationship between higher socioeconomic status neighborhoods wherein increased resources allowed for more resiliency [92]. In contrast, individuals residing in lower socioeconomic status neighborhoods face a disadvantage due to limited access to these flexible resources [93,94]. If basic needs are not being met for neighborhood citizens, no amount of creativity will convert absolute deprivation into flexible resources. However, building the capacity for resilience within a neighborhood could come in the form of creatively increasing the flexibility of the limited resources that are present. As such, neighborhoods with highly connected citizens will have an increased resilience capacity. Conversely, disadvantaged neighborhoods are more at risk for destabilization, possibly due to a lack of built social capital [95].

Children and adolescents are psychologically vulnerable. Developmental psychopathology frameworks explain that various stressors, including environmental, neurobiological, and emotional stressors, can increase the prevalence of adverse mental health outcomes based on developmental staging [96]. This review reinforces the positive relationship between increased access to flexible resources such as beneficial social connections, knowledge, money, power, and prestige, and increased neighborhood adaptive capacity. Favorable social conditions with flexible resources promote increased adaption to unforeseen events of all types [97].

Strengths and Limitations

A limitation of this study was the variability of independent reviewer voting as manifested by fair to moderate interrater reliability scores. This scoping review was exploratory by nature. Achieving an eventual consensus between two independent reviewers through memo’ing and discussion clarified the conclusions drawn.

An additional limitation was that we did not conduct quality appraisals on each article. We established an a priori protocol for our study and mitigated potential bias originating from our study. However, inclusion criteria for this study were based on the potential conceptual value and not the rigor of the reviewed study. Although all the included studies had conceptual value for the discourse of neighborhood resilience, not all reviewed studies were of quality or designed to, on their own, inform practice changes.

A strength of this scoping review is the comprehensiveness of the literature reviewed. Our specific objective was to review articles that contribute to the conceptual understanding of neighborhood resilience across all contexts found in the literature. As a result of the broad exploration undertaken by this study, the findings are presented in a concise and condensed manner, with greater emphasis on the wide breadth of literature than on detailed analysis. It is important to note that the intention of scoping reviews is to provide a broad assessment of the literature on a given topic and inform next steps, which we have effectively accomplished in this study.

5. Conclusions

With this study, we reviewed 28 years of literature and cataloged the risk factors and, perhaps more importantly, the protective factors of neighborhood resiliency. We have established the foundation on which our Extension community resource publications can be built upon. This scoping review contributes to the growing body of evidence regarding how neighborhood environmental factors influence the resilience of groups and individuals. This scoping review presents a foundation of how neighborhoods influence childhood resilience. Implications of this knowledge can help inform neighborhood health promotion strategies intended to build protective and resilient environments for children.

We recommend the next steps of this synthesized knowledge to be the future conceptual modeling of the core constructs of resilience in the neighborhood context. This scoping review can also contribute to discourse regarding the planning and policy development that directly affect resource availability in neighborhoods and, by proxy, promote positive health outcomes for youth.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/children10111791/s1, Table S1. Conceptualization of Resilience and Levels of Resilience.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.B. and K.D.; methodology, S.B. and K.D.; software, S.B. and K.D.; validation, S.B., K.D. and K.W.-Y.; formal analysis, S.B., K.D. and K.W.-Y.; investigation, S.B. and K.D.; data curation, S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.B.; writing—review and editing, S.B., K.D., K.W.-Y., J.P. and J.M.G.; visualization, S.B.; supervision, J.P. and J.M.G.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R25ES033452. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Shawna Beese received additional support for this study from the Lukins Scott & Betty Graduate Fellowship through the Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy & Public Service at Washington State University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not involve human subjects or related data. Thus, institutional review board approval was not sought.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their insights and comments. Shawna Beese and Kailie Drumm want to thank Jessica Castner for her leadership and mentoring through the Environmental Health Research Institute for Nurse and Clinician Scientists fellowship experience.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rajmil, L.; Fernandez de Sanmamed, M.J.; Choonara, I.; Faresjö, T.; Hjern, A.; Kozyrskyj, A.L.; Lucas, P.J.; Raat, H.; Séguin, L.; Spencer, N.; et al. Impact of the 2008 economic and financial crisis on child health: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 6528–6546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, S.; Roth, C.; Zimsen, T.; Bridson, T.L.; Sarnyai, Z.; McDermott, B. Adverse childhood experiences and allostatic load: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2022, 136, 104605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayhoe, K.; Wuebbles, D.J.; Easterling, D.R.; Fahey, D.W.; Doherty, S.; Kossin, J.P.; Sweet, W.V.; Vose, R.S.; Wehner, M.F. Chapter 2: Our Changing Climate. Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States. The Fourth National Climate Assessment; Global Change Research Program: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; Volume II. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminade, C.; Kovats, S.; Rocklov, J.; Tompkins, A.M.; Morse, A.P.; Colón-González, F.J.; Stenlund, H.; Martens, P.; Lloyd, S.J. Impact of climate change on global malaria distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3286–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.S.; Sharker, M.A.Y.; Rheman, S.; Hossain, S.; Mahmud, Z.H.; Islam, M.S.; Uddin, A.M.K.; Yunus, M.; Osman, M.S.; Ernst, R.; et al. Effects of local climate variability on transmission dynamics of cholera in Matlab, Bangladesh. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2009, 103, 1165–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Environmental Protection Agency. EPA Climate Change/Ag. 2016. Available online: https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/climate-impacts/climate-impacts-agriculture-and-food-supply_.html (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Waisel, D.B. Vulnerable populations in healthcare. Curr. Opin. Anaesthesiol. 2013, 26, 186–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vergunst, F.; Berry, H.L. Climate Change and Children’s Mental Health: A Developmental Perspective. Clin. Psychol. Sci. A J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2022, 10, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am. Psychol. 1977, 32, 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragavan, M.I.; Marcil, L.E.; Garg, A. Climate change as a social determinant of health. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20193169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, M.K.; Kennedy, A.M.; Witham, S.M. The interplay between social and ecological determinants of mental health for children and youth in the climate crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.; Amaro, J.; Lisi, C.; Fraga, S. Neighborhood Socioeconomic Deprivation and Allostatic Load: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beese, S.; Postma, J.; Graves, J.M. Allostatic Load Measurement: A Systematic Review of Reviews, Database Inventory, and Considerations for Neighborhood Research. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 17006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glewwe, P.; Hall, G. Are some groups more vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks than others? Hypothesis tests based on panel data from Peru. J. Dev. Econ. 1998, 56, 181–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanson, A.V.; Van Hoorn, J.; Burke, S.E.L. Responding to the Impacts of the Climate Crisis on Children and Youth. Child Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.-K.; Beach, S.R.H.; Simons, R.L. Biological embedding of neighborhood disadvantage and collective efficacy: Influences on chronic illness via accelerated cardiometabolic age. Dev. Psychopathol. 2018, 30, 1797–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butterfield, P.G. Thinking upstream: Nurturing a conceptual understanding of the societal context of health behavior. Adv. Nurs. Sci. 1990, 12, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez Roux, A.V.; Mair, C. Neighborhoods and health: Neighborhoods and health. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1186, 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchak, N.P.; Browning, C.R.; Calder, C.A.; Boettner, B. Activity Locations, Residential Segregation, and the Significance of Residential Neighborhood Boundary Perceptions. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 2758–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Covidence Systematic Review Software, Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available online: www.covidence.org (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisenberg, E.; Herrenkohl, T. Community Violence in Context: Risk and Resilience in Children and Families. J. Interpers. Violence 2008, 23, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anthony, E.K. Cluster Profiles of Youths Living in Urban Poverty: Factors Affecting Risk and Resilience. Soc. Work Res. 2008, 32, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, C.G.; Pontes, N.M. Use of Theory to Examine Health Responsibility in Urban Adolescents. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 2018, 38, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnett, M.A.; Mortensen, J.A.; Gonzalez, H.; Gonzalez, J.-M. Cultural Factors Moderating Links Between Neighborhood Disadvantage and Parenting and Coparenting Among Mexican Origin Families. Child Youth Care Forum 2016, 45, 927–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnhart, S.; Bode, M.; Gearhart, M.C.; Maguire-Jack, K. Supportive Neighborhoods, Family Resilience and Flourishing in Childhood and Adolescence. Children 2022, 9, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barzilay, R.; Moore, T.M.; Calkins, M.E.; Maliackel, L.; Jones, J.D.; Boyd, R.C.; Warrier, V.; Benton, T.D.; Oquendo, M.A.; Gur, R.C.; et al. Deconstructing the role of the exposome in youth suicidal ideation: Trauma, neighborhood environment, developmental and gender effects. Neurobiol. Stress 2021, 14, 100314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bethell, C.D.; Garner, A.S.; Gombojav, N.; Blackwell, C.; Heller, L.; Mendelson, T. Social and Relational Health Risks and Common Mental Health Problems Among US Children: The Mitigating Role of Family Resilience and Connection to Promote Positive Socioemotional and School-Related Outcomes. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2022, 31, 45–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boch, S.J.; Ford, J.L. Protective Factors to Promote Health and Flourishing in Black Youth Exposed to Parental Incarceration. Nurs. Res. 2021, 70, S63–S72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogar, S.; Young, S.; Woodruff, S.; Beyer, K.; Mitchell, R.; Johnson, S. More than gangsters and girl scouts: Environmental health perspectives of urban youth. Health Place 2018, 54, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, G.H.; Yu, T.; Chen, E.; Miller, G.E.; Kogan, S.M.; Beach, S.R.H. Is resilience only skin deep?: Rural African Americans’ socioeconomic status-related risk and competence in preadolescence and psychological adjustment and allostatic load at age 19. Psychol. Sci. 2013, 24, 1285–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, F.; Galanek, J.D.; Kretschmar, J.M.; Flannery, D.J. The impact of neighborhood disorganization on neighborhood exposure to violence, trauma symptoms, and social relationships among at-risk youth. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 146, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cagney, K.A.; Sterrett, D.; Benz, J.; Tompson, T. Social Resources and Community Resilience in the Wake of Superstorm Sandy. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0160824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, K.R.; McCreary, M.; Ford, J.D.; Rahmanian Koushkaki, S.; Kenan, K.N.; Zima, B.T. Validation of the Traumatic Events Screening Inventory for ACEs. Pediatrics 2019, 143, e20182546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.-K.; Teshome, T.; Smith, J. Neighborhood disadvantage, childhood adversity, bullying victimization, and adolescent depression: A multiple mediational analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 279, 554–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christodoulou, J.; Rotheram-Borus, M.J.; Hayati Rezvan, P.; Comulada, W.S.; Stewart, J.; Almirol, E.; Tomlinson, M. Where you live matters: Township neighborhood factors important to resilience among south African children from birth to 5 years of age. Prev. Med. 2022, 157, 106966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.; Ball, K.; Cleland, V.; Thornton, L.; Abbott, G.; McNaughton, S.A.; Campbell, K.J.; Brug, J.; Salmon, J.; Timperio, A. Maternal efficacy and sedentary behavior rules predict child obesity resilience. BMC Obes. 2015, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crouch, E.; Radcliff, E.; Merrell, M.A.; Hung, P.; Bennett, K.J. Positive Childhood Experiences Promote School Success. Matern. Child Health J. 2021, 25, 1646–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouch, E.; Radcliff, E.; Kelly, K.; Merrell, M.A.; Bennett, K.J. Examining the influence of positive childhood experiences on childhood overweight and obesity using a national sample. Prev. Med. 2022, 154, 106907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crush, E.; Arseneault, L.; Jaffee, S.R.; Danese, A.; Fisher, H.L. Protective Factors for Psychotic Symptoms Among Poly-victimized Children. Schizophr. Bull. 2018, 44, 691–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, E.M.; Frazier, S.L.; Hansen, E.; Patel, H.H.; Ahmed, Z.; Okeke, D.; Nardi, M.I.; Messiah, S.E. Two-Year Changes in Neighborhood Juvenile Arrests After Implementation of a Park-Based Afterschool Mental Health Promotion Program in Miami-Dade County, Florida, 2015–2017. Am. J. Public Health 2019, 109, S214–S220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Imperio, R.L.; Dubow, E.F.; Ippolito, M.F. Resilient and stress-affected adolescents in an urban setting. J. Clin. Child Psychol. 2000, 29, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, B.P.; Shin, R.Q.; Thakral, C.; Selders, M.; Vera, E. School engagement among urban adolescents of color: Does perception of social support and neighborhood safety really matter? J. Youth Adolesc. 2009, 38, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DaViera, A.L.; Roy, A.L.; Uriostegui, M.; Fiesta, D. Safe Spaces Embedded in Dangerous Contexts: How Chicago Youth Navigate Daily Life and Demonstrate Resilience in High-Crime Neighborhoods. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2020, 66, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deane, K.C.; Richards, M.; Bocanegra, K.; Santiago, C.D.; Scott, D.; Zakaryan, A.; Romero, E. Mexican American Urban Youth Perspectives on Neighborhood Stressors, Psychosocial Difficulties, and Coping: En Sus Propias Palabras. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2020, 29, 1780–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmelle, E.; Hagenlocher, M.; Kienberger, S.; Casas, I. A spatial model of socioeconomic and environmental determinants of dengue fever in Cali, Colombia. Acta Trop. 2016, 164, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiClemente, C.M.; Rice, C.M.; Quimby, D.; Richards, M.H.; Grimes, C.T.; Morency, M.M.; White, C.D.; Miller, K.M.; Pica, J.A. Resilience in Urban African American Adolescents: The Protective Enhancing Effects of Neighborhood, Family, and School Cohesion Following Violence Exposure. J. Early Adolesc. 2018, 38, 1286–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, A.C.; Ouellette, R.R.; D’Agostino, E.M.; Hansen, E.; Lee, T.; Frazier, S.L. Promoting healthy trajectories for urban middle school youth through county-funded, parks-based after-school programming. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49, 2795–2817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Keller, J.; Zhang, T.; Dempsey, D.R.; Roberts, H.; Jeans, K.A.; Stevens, W.; Borchard, J.; VanPelt, J.; Tulchin-Francis, K. Disparity in Built Environment and Its Impacts on Youths’ Physical Activity Behaviors During COVID-19 Pandemic Restrictions. J. Racial Ethn. Health Disparit. 2022, 10, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard-Garris, N.; Davis, M.M.; Szilagyi, M.; Kan, K. Childhood adversity and parent perceptions of child resilience. BMC Pediatr. 2018, 18, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, A.C.; Madden, P.A.; Grant, J.D.; McLaughlin, T.L.; Todorov, A.A.; Bucholz, K.K. Resiliency factors protecting against teenage alcohol use and smoking: Influences of religion, religious involvement and values, and ethnicity in the Missouri Adolescent Female Twin Study. Twin Res. Off. J. Int. Soc. Twin Stud. 1999, 2, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, C.S.; Bámaca-Colbert, M.Y.; Liu, C.; Plunkett, S.W.; Kern, B.L.; Behnke, A.O.; Washburn, I.J. Parenting Behaviors, Neighborhood Quality, and Substance Use in 9th and 10th Grade Latino Males. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2018, 27, 4103–4115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, M.R.; Yoon, S.; Berg, K.A.; Cage, J.L.; Perzynski, A.T. Promoting the development of resilient academic functioning in maltreated children. Child Abus. Negl. 2018, 75, 92–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopson, L.M.; Schiller, K.S.; Lawson, H.A. Exploring Linkages between School Climate, Behavioral Norms, Social Supports, and Academic Success. Soc. Work Res. 2014, 38, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, E.I.; Kilpatrick, T.; Bolland, A.; Bolland, J. Positive youth development in the context of household member contact with the criminal justice system. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 114, 105033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, V.; Hirai, A.H.; Ghandour, R.M.; Kogan, M.D. Parental Perception of Flourishing in School-Aged Children: 2011-2012 National Survey of Children’s Health. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. JDBP 2018, 39, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koinis Mitchell, D.; Klein Murdock, K.; McQuaid, E.L. Risk and Resilience in Urban Children with Asthma: A Conceptual Model and Exploratory Study. Child. Health Care 2004, 33, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Santiago, A.M. Cumulative Exposure to Neighborhood Conditions and Substance Use Initiation among Low-Income Latinx and African American Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenberg, C.S.; Gendrop, S.C.; Nencioli, M.; Adames, Z. Substance abuse among inner-city Hispanic women: Exploring resiliency. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Neonatal Nurs. JOGNN 1994, 23, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhi, D.; Brown, M.; Fromm Reed, S. Community-wide resilience mitigates adverse childhood experiences on adult and youth health, school/work, and problem behaviors. Am. Psychol. 2021, 76, 216–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, B.A.; Finney Rutten, L.J.; Wilson, P.M.; Kumar, S.; Phelan, S.; Jacobson, R.M.; Fan, C.; Agunwamba, A. The impact of positive contextual factors on the association between adverse family experiences and obesity in a National Survey of Children. Prev. Med. 2018, 116, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marçal, K.E.; Maguire-Jack, K. Informal supports, housing insecurity, and adolescent outcomes: Implications for promoting resilience. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 70, 178–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, S.C.; Clinkinbeard, S.S.; Thomas, R.M.; Evans, W.P. Risk and protective factors predictive of sense of coherence during adolescence. J. Health Psychol. 2007, 12, 281–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, A.; Hackman, D.; Baker, F.; Breslin, F.; Brown, S.; Dick, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Guillaume, M.; Kiss, O.; Lisdahl, K.; et al. Resilience to COVID-19: Socioeconomic Disadvantage Associated with Higher Positive Parent-youth Communication and Youth Disease-prevention Behavior. Res. Sq. 2021, rs.3.rs-444161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloy, M.; Curtis, K.; Tucker, S.; Previ, B.; Storrod, M.L.; Gordon, G.; Larson, M.; Webb, W.; Delacruz, M. Surviving All the Way to College: Pathways Out of One of America’s Most Crime Ridden Cities. J. Interpers. Violence 2021, 36, 4277–4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, G.E.; Chen, E.; Finegood, E.D.; Lam, P.H.; Weissman-Tsukamoto, R.; Leigh, A.K.K.; Hoffer, L.; Carroll, A.L.; Brody, G.H.; Parrish, T.B.; et al. Resting-State Functional Connectivity of the Central Executive Network Moderates the Relationship Between Neighborhood Violence and Proinflammatory Phenotype in Children. Biol. Psychiatry 2021, 90, 165–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nash, J.K.; Bowen, G.L. Perceived crime and informal social control in the neighborhood as a context for adolescent behavior: A risk and resilience perspective. Soc. Work Res. 1999, 23, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera, N.; Hammons, A.J.; Teran-Garcia, M.; Plaza-Delestre, M.; Fiese, B. Hispanic Parents’ Views of Family Physical Activity: Results from a Multisite Focus Group Investigation. Children 2021, 8, 740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prins, S.J.; Kajeepeta, S.; Hatzenbuehler, M.L.; Branas, C.C.; Metsch, L.R.; Russell, S.T. School Health Predictors of the School-to-Prison Pipeline: Substance Use and Developmental Risk and Resilience Factors. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2022, 70, 463–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.A.; Drabick, D.A.G.; Reynolds, M.D. Youth Withdrawal Moderates the Relationhips Between Neighborhood Factors and Internalizing Symptoms in Adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2016, 45, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabinowitz, J.A.; Powell, T.; Sadler, R.; Reboussin, B.; Green, K.; Milam, A.; Smart, M.; Furr-Holden, D.; Latimore, A.; Tandon, D. Neighborhood Profiles and Associations with Coping Behaviors among Low-Income Youth. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 494–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J.C.; Robles, R.R.; Colón, H.M.; Negrón, J.; Matos, T.D.; Calderón, J.; Pérez, O.M. Neighborhood disorganization, substance use, and violence among adolescents in Puerto Rico. J. Interpers. Violence 2008, 23, 1499–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasser, J.; Duprey, E.B.; Oshri, A. A longitudinal investigation of protective factors for bereaved maltreated youth. Child Abus. Negl. 2019, 96, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, H.C. “Missed, dissed, and pissed”: Making meaning of neighborhood risk, fear and anger management in urban black youth. Cult. Divers. Ment. Health 1997, 3, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanderbilt-Adriance, E.; Shaw, D.S. Neighborhood risk and the development of resilience. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2006, 1094, 359–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Choi, J.-K.; Shin, J. Long-term Neighborhood Effects on Adolescent Outcomes: Mediated through Adverse Childhood Experiences and Parenting Stress. J. Youth Adolesc. 2020, 49, 2160–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, E.; Ashley, D. The New Imperative: Reducing Adolescent-Related Violence by Building Resilient Adolescents. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, S43–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Yoon, S.; Maguire-Jack, K.; Knox, J.; Ploss, A. Socio-Ecological Predictors of Resilience Development Over Time Among Youth with a History of Maltreatment. Child Maltreatment 2021, 26, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisev, N.; Bell, J.S.; Chen, T.F. Interrater agreement and interrater reliability: Key concepts, approaches, and applications. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. RSAP 2013, 9, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brody, G.H.; Yu, T.; Beach, S.R.H. Resilience to adversity and the early origins of disease. Dev. Psychopathol. 2016, 28(4 pt 2), 1347–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, E.; Miller, G.E.; Brody, G.H.; Lei, M. Neighborhood Poverty, College Attendance, and Diverging Profiles of Substance Use and Allostatic Load in Rural African American Youth. Clin. Psychol. Sci. A J. Assoc. Psychol. Sci. 2015, 3, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurius, P.S.; Green, S.; Logan-Greene, P.; Longhi, D.; Song, C. Stress pathways to health inequalities: Embedding ACEs within social and behavioral contexts. Int. Public Health J. 2016, 8, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Breton, M. Neighborhood Resiliency. J. Community Pract. 2001, 9, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, A.A.; Wright, E.M.; Pinchevsky, G.M. The protective effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on adolescent substance use and violence following exposure to violence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1498–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.; Cohen, A.K. Behavioral adaptation among youth exposed to community violence: A longitudinal multidisciplinary study of family, peer and neighborhood-level protective factors. Prev. Sci. Off. J. Soc. Prev. Res. 2013, 14, 606–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ta, M.; Shankardass, K. Piloting the Use of Concept Mapping to Engage Geographic Communities for Stress and Resilience Planning in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slemp, C.C.; Sisco, S.; Jean, M.C.; Ahmed, M.S.; Kanarek, N.F.; Erös-Sarnyai, M.; Gonzalez, I.A.; Igusa, T.; Lane, K.; Tirado, F.P.; et al. Applying an Innovative Model of Disaster Resilience at the Neighborhood Level: The COPEWELL New York City Experience. Public Health Rep. 2020, 135, 565–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, E.L.; Barrett, N.D.; Edberg, M.C.; Seeger, M.W.; Santos-Burgoa, C. Resilience of Communities in Puerto Rico Following Hurricane Maria: Community-Based Preparedness and Communication Strategies. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2021, 17, e53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpiano, R.M. Neighborhood social capital and adult health: An empirical test of a Bourdieu-based model. Health Place 2007, 13, 639–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clouston, S.A.P.; Link, B.G. A retrospective on fundamental cause theory: State of the literature, and goals for the future. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2021, 47, 131–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, B.G.; Phelan, J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1995, 36, 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Diez-Roux, A.; Kawachi, I.; Levin, B. “Fundamental causes” of social inequalities in mortality: A test of the theory. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2004, 45, 265–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Broeder, L.; South, J.; Rothoff, A.; Bagnall, A.M.; Azarhoosh, F.; van der Linden, G.; Bharadwa, M.; Wagemakers, A. Community engagement in deprived neighbourhoods during the COVID-19 crisis: Perspectives for more resilient and healthier communities. Health Promot. Int. 2022, 37, daab098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Achenbach, T.M. Conceptualization of Developmental Psychopathology. In Handbook of Developmental Psychopathology; Lewis, M., Miller, S.M., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, J.C.; Link, B.G.; Tehranifar, P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: Theory, evidence, and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010, 51, S28–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).