Abstract

Background/Objectives: Guided imagery techniques, which include mentally picturing motions or activities to help motor recovery, are an important part of neuroplasticity-based motor therapy in stroke patients. Motor imagery (MI) is a kind of guided imagery in neurorehabilitation that focuses on mentally rehearsing certain motor actions in order to improve performance. This systematic review aims to evaluate the current evidence on guided imagery techniques and identify their therapeutic potential in stroke motor rehabilitation. Methods: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) published in the English language were identified from an online search of PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, EBSCOhost, and Scopus databases without a specific search time frame. The inclusion criteria take into account guided imagery interventions and evaluate their impact on motor recovery through validated clinical, neurophysiological, or functional assessments. This review has been registered on Open OSF with the following number: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/3D7MF. Results: This review synthesized 41 RCTs on MI in stroke rehabilitation, with 996 participants in the intervention group and 757 in the control group (average age 50–70, 35% female). MI showed advantages for gait, balance, and upper limb function; however, the RoB 2 evaluation revealed ‘some concerns’ related to allocation concealment, blinding, and selective reporting issues. Integrating MI with gait training or action observation (AO) seems to improve motor recovery, especially in balance and walking. Technological methods like brain–computer interfaces (BCIs) and hybrid models that combine MI with circuit training hold potential for enhancing functional mobility and motor results. Conclusions: Guided imagery shows promise as a beneficial adjunct in stroke rehabilitation, with the potential to improve motor recovery across several domains such as gait, upper limb function, and balance.

1. Introduction

In 1970, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined a stroke as ‘rapidly developed clinical signs of focal (or global) disturbance of cerebral function, lasting more than 24 h or leading to death, with no apparent cause other than of vascular origin’ [1,2]. According to the WHO, each year 12.2 million new cases are diagnosed, and 6.5 million deaths are reported around the globe [3,4]. Motor rehabilitation is essential for recovery after a stroke because neurological damage frequently results in major deficits in motor abilities, coordination, and movement [5,6,7]. Stroke survivors often face hemiparesis, muscle weakness, spasticity, and diminished fine motor skills, which can greatly impair their capacity to carry out daily tasks autonomously [8,9,10]. These motor impairments not only hinder physical capability but also lead to a deterioration in overall life quality, elevating the likelihood of depression, social seclusion, and extended disability [11,12]. Successful motor rehabilitation approaches seek to reinstate movement patterns, improve neuromuscular control, and foster neuroplasticity, which is the capacity of the nervous system to compensate for injury by strengthening existing connections, forming new synapses, and recruiting alternative neural networks to regain motor, sensory, or cognitive abilities. In recovery from stroke, neuroplasticity is one of the main mechanisms that underlie functional recovery by facilitating cortical reorganization and the recovery of lost motor function via experience-dependent synaptic modifications. The brain also undergoes a number of plastic alterations after a stroke, including dendritic sprouting, axonal remodeling, and cortical excitability changes, particularly in motor-related areas including the primary motor cortex (M1), premotor cortex, and supplementary motor area [13,14,15]. These changes are directed by therapeutic interventions to augment the brain’s inherent capacity to reorganize after an injury. Guided imagery methods, which include mentally imagining motions or activities to aid motor recovery, are an important component of neuroplasticity-based motor rehabilitation [16,17]. MI activates neural circuits similar to those engaged during actual movement execution, involving M1, the premotor cortex, the cerebellum, and the basal ganglia. This common neural representation indicates that MI may strengthen current motor pathways, elevate corticospinal excitability, and improve functional connectivity among motor and sensory areas [18]. Another significant neuroplastic mechanism associated with guided imagery is its capacity to improve sensory–motor integration. Because MI necessitates that individuals visualize and “experience” movement in their minds, it activates proprioceptive and kinesthetic processing routes, enhancing the connection between motor intentions and sensory input [19]. This integration is crucial for enhancing motor programs and maximizing motor control, especially in individuals rehabilitating from stroke, where sensorimotor impairments can pose a major obstacle to functional progress. These strategies are based on the idea that imagining a movement activates brain pathways similar to those used during actual physical performance, strengthening motor circuits even when no observable movement happens [20,21]. Guided imagery can be presented in several ways. A therapist, for example, might vocally lead a patient through an organized mental exercise, explaining each movement in detail and urging them to picture sensations like muscle contraction, joint movement, or even the sense of holding an object in their hand [22,23]. This method is most effective when tailored to the individual’s specific deficits, progressively increasing the complexity of imagined activities as their recovery advances [24,25]. Technology-assisted guided imagery has made great progress, including virtual reality, BCIs, and robots to improve motor rehabilitation [26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. BCIs give real-time feedback, reinforcing sensorimotor pathways, whereas robotic-assisted treatment enhances visualization by allowing for regulated, repeated motions, bridging the gap between mental rehearsal and execution [33,34,35,36,37]. Similarly, neurophysiological and neuromodulation approaches aid in the assessment and enhancement of neuroplasticity. Electroencephalography (EEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) monitor brain activity changes [38], while transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) and transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) regulate cortical excitability, therefore maximizing neuronal reconfiguration [39,40]. Together, these technologies improve rehabilitation tactics by providing individualized, data-driven approaches to stroke recovery. MI is a specialized use of guided imagery in neurorehabilitation that focuses on mentally practicing certain motor activities in order to enhance functionality [41]. Motor imagery training (MIT) is especially useful for stroke survivors who have limited mobility because it activates the sensorimotor cortex without needing actual movement [42]. MI protocols for stroke recovery often include planned exercises in which patients envision themselves doing motions like gripping an item, extending their arm, or walking [43]. These exercises can be supplemented with kinesthetic imaging, in which participants mentally feel the sensation of movement, or visual imagery, in which they picture themselves completing the activity from a first- or third-person perspective [44,45]. When combined with other rehabilitation approaches (such as mirror therapy, robotic-assisted training, or neuromodulation), MI can dramatically speed up recovery by strengthening the neural circuits responsible for motor control [46]. Although growing evidence supports the use of guided imagery in stroke rehabilitation, its precise impact on motor recovery remains unclear. Significant gaps persist in understanding the most effective ways to deliver these interventions, including whether guided imagery should be applied alone or in combination with other rehabilitation approaches such as physical therapy, neuromodulation, or virtual reality training, and under what specific conditions it yields the greatest benefits. Additionally, key parameters such as the optimal frequency, intensity, and duration of guided imagery sessions have not been systematically established, making it difficult to standardize treatment protocols and compare findings across studies. The heterogeneity in outcome measures, ranging from functional motor assessments to neurophysiological markers and patient-reported experiences, further complicates the ability to draw definitive conclusions about its clinical efficacy.

This systematic review seeks to fill these gaps by compiling results solely from RCTs, offering a more thorough assessment of the efficacy of guided imagery for motor rehabilitation in individuals who have had a stroke. This review aims to pinpoint best practices for implementing guided imagery by thoroughly examining methodological differences, intervention protocols, and reported results, while also emphasizing areas that need more investigation and providing evidence-based suggestions for its incorporation into regular stroke rehabilitation programs. The rationale behind this review stems from the increasing recognition of neuroplasticity as a key mechanism in post-stroke motor recovery. Traditional rehabilitation approaches primarily rely on physical movement to stimulate motor pathways, yet many stroke patients experience significant mobility restrictions that limit their ability to engage in active training. Guided imagery offers a non-invasive, accessible alternative that can stimulate sensorimotor circuits even in the absence of overt movement, potentially accelerating functional recovery. This review is grounded in the Motor Simulation Theory and the Hebbian Theory of neuroplasticity [47,48]. The first one suggests that mentally rehearsing movements engages neural networks in the same way as physical execution, reinforcing motor representations and facilitating skill acquisition. Meanwhile, Hebbian plasticity emphasizes the principle that “neurons that fire together, wire together”, highlighting how repeated activation of sensorimotor pathways (whether through actual movement or mental practice) can strengthen synaptic connections. By integrating these frameworks, this review will assess how guided imagery techniques leverage neuroplastic mechanisms to enhance motor function, providing insights into their role as a complementary rehabilitation strategy. To further illustrate the role of guided imagery in stroke rehabilitation, Table 1 provides a detailed comparison of key techniques, their underlying neural mechanisms, application contexts, and associated neurophysiological measurements that support their therapeutic effectiveness [49,50,51,52,53].

Table 1.

Overview of guided imagery techniques and motor imagery in stroke rehabilitation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

This systematic review employs a structured approach without applying a specific search period to ensure a comprehensive exploration of the available evidence on guided imagery techniques in stroke motor rehabilitation. By not restricting the timeframe, the review aims to capture all relevant studies, regardless of publication date, that contribute to understanding the evolution of research and advancements in this field. This approach ensures a broader perspective while maintaining focus on the most recent and applicable findings. We performed an extensive literature search using the PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, EBSCOhost, and Scopus databases, utilizing the keywords (All Fields: “Guided Imagery”) AND (All Fields: “Stroke”) AND (All Fields: “Motor Rehabilitation”) from 15 November 2024 to 9 January 2025. These databases were carefully selected to cover the broadest possible range of peer-reviewed literature in the fields relevant to this review. PubMed was selected for its deep representation of biomedical research, particularly its rich indexing of neurological disorders and rehabilitation research. Web of Science was considered for its multidisciplinary coverage and its citation tracking functionality, which allows identification of seminal works in the field. Embase was selected for its long-standing reputation for providing broad coverage of clinical and pharmacological studies, particularly in neurorehabilitation studies. EBSCOhost made a range of specialist health sciences databases available. Additionally, Scopus was selected for its broad multidisciplinary coverage and sophisticated citation analysis capabilities that help reflect the diversity of studies included in the retrieved field. Only RCTs involving adults and published in English were included in this review. By using these databases, we sought to maximize the robustness and therefore validity of our strategy, reduce the possibility of missing important studies, and allow for the inclusion of high-quality, diverse evidence.

2.1.1. Data Extraction

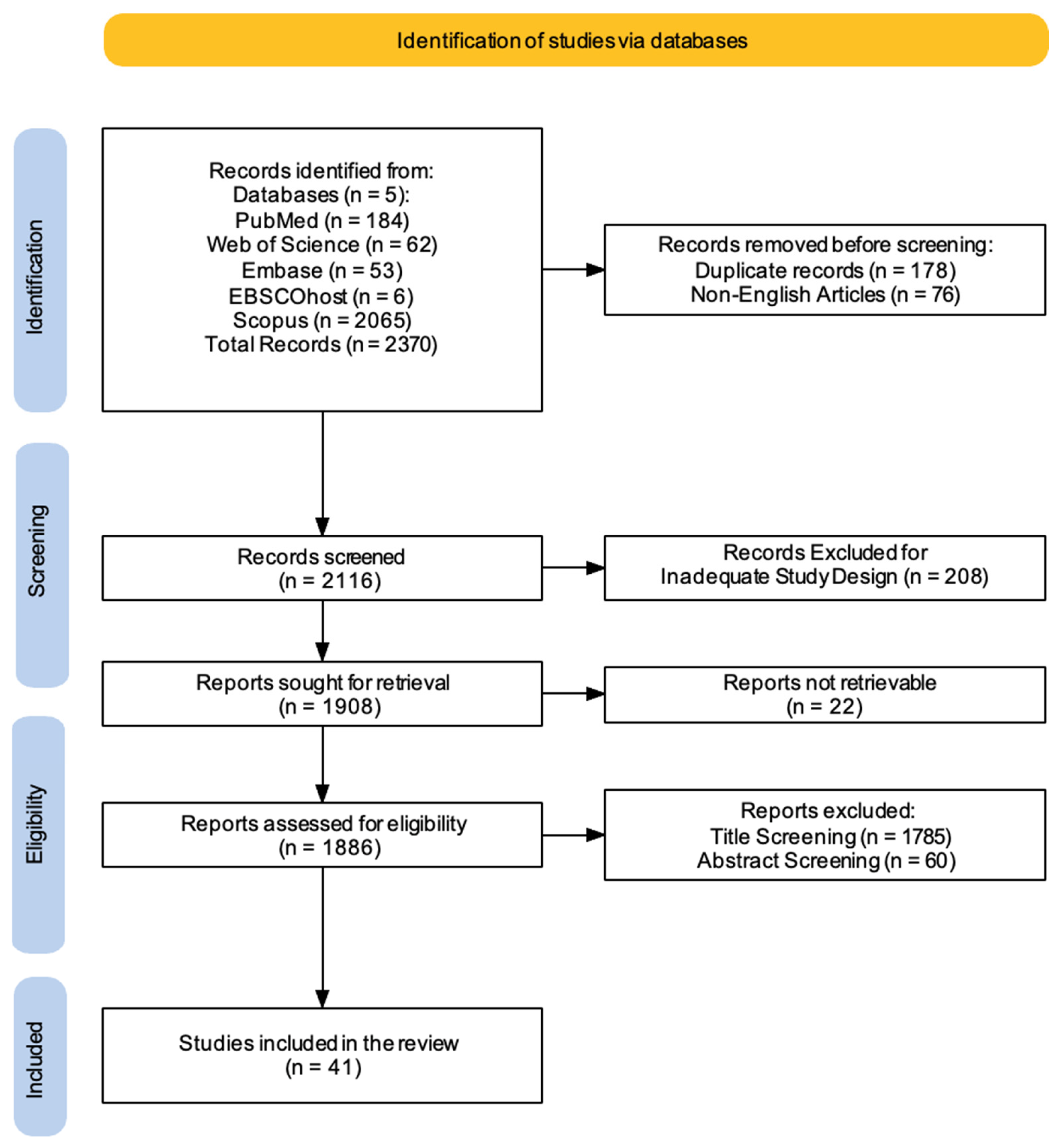

Two reviewers (AC, AM) performed independent searches to improve transparency and accuracy in locating pertinent studies. The search strategy was iteratively refined by testing different combinations of keywords, Boolean operators, and controlled vocabulary (e.g., MeSH terms) to maximize sensitivity and specificity. The PRISMA flowchart was employed to depict the process (identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion) for choosing relevant studies, as shown in Figure 1 [54]. The Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2) framework was applied to assess bias risk in the RCTs included in this review. A detailed protocol for assessing bias, aligned with the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, was followed to maintain methodological rigor. Additionally, two researchers (AC, AM) screened all articles based on titles, abstracts, and full texts, conducting independent data extraction, article gathering, and cross-validation to minimize bias risks (e.g., missing results bias, publication bias, time lag bias, language bias). The gathered data included study design, sample size, characteristics of participants, types of strokes, specifics of the guided and MI intervention, duration, assessed outcomes, and findings. The researchers (AC, AM) reviewed complete text articles considered suitable for the study, and if there were disagreements regarding the inclusion and exclusion criteria, a final decision was reached by a third researcher (RSC). Discrepancies between reviewers during the screening or data extraction process were also resolved through discussion, with unresolved cases adjudicated by a third reviewer (RSC). Additionally, the concordance between the two evaluators (AC and AM) was evaluated through the kappa statistic. The kappa score, which has a recognized threshold for significant agreement established at >0.61, was understood to indicate substantial alignment among the reviewers. This standard guarantees a strong assessment of inter-rater reliability, highlighting the attainment of a significant degree of consensus in the data extraction procedure. Data extraction and organization were facilitated using Microsoft Excel, which streamlined the process and minimized human error. The software allowed for efficient management of large datasets, enabling reviewers to systematically record study characteristics, risk of bias assessments, and outcome data. Custom extraction sheets were designed within the software to ensure consistency and adherence to the predefined inclusion/exclusion criteria. Additionally, the software provided features such as tagging, filtering, and sorting, which facilitated the resolution of discrepancies and expedited the cross-validation process. The compilation of articles was subsequently refined for relevance, assessed, and summarized, with main topics highlighted from the summary according to the inclusion/exclusion standards. This systematic review has been registered on Open OSF under the following number: DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/3D7MF.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram of evaluated studies.

2.1.2. Data Synthesis

Data synthesis was conducted using narrative methods and quantitative analysis to tackle the variety of guided and MI interventions and types of strokes included. This method allowed us to identify key themes, commonalities, and differences across the research landscape. Effect sizes and evidence certainty from diverse studies reflecting various interventions and stroke populations were reported. Studies were grouped based on intervention types, patient characteristics, and reported outcomes to highlight consistencies and discrepancies. Throughout the synthesis process, the inclusion of a multidisciplinary team ensured a balanced interpretation of the data. Regular discussions and consensus meetings among reviewers helped mitigate potential biases in qualitative assessments and ensured consistency in categorizing and interpreting outcomes. This integrated approach combined qualitative insights with quantitative precision, offering a holistic understanding of the research landscape while addressing the complexities inherent in the studies.

2.2. PICO Evaluation

We applied the PICO model (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) to create our search terms.

The target population consists of adults who have had a stroke. The intervention being studied is guided MI, a technique that includes mentally imitating certain motor actions to improve brain plasticity and motor recovery. This will be compared against traditional motor rehabilitation treatments, such as physical therapy alone or no intervention at all, to establish its relative efficacy. The key outcomes of interest are gains in motor function, mobility, and overall recovery rates, while secondary goals include quality of life, patient adherence to therapy, and cognitive engagement throughout rehabilitation.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for this systematic review focused on identifying research studies that explored the impact of guided imagery techniques, with an emphasis on MI, on motor rehabilitation outcomes in stroke patients. To be eligible, studies needed to investigate guided imagery interventions and assess their effects on motor recovery using validated clinical, neurophysiological, or functional measures. Included articles were required to provide a clear description of the guided imagery protocols, including their structure, duration, and delivery methods, along with measurable outcomes related to motor function, mobility, or recovery. Included studies targeted adult participants (≥18 years) diagnosed with stroke and presenting motor impairments. The review specifically considered guided imagery techniques delivered either through technological devices, such as BCIs and robotic devices, or guided by a human operator, such as a clinician or therapist. The review included primary research encompassing only RCTs. This decision was based on the need to ensure a high level of evidence and minimize the risk of bias when assessing the impact of guided imagery techniques on motor rehabilitation outcomes in stroke patients. RCTs are considered the gold standard for evaluating the efficacy of interventions due to their rigorous methodology, which includes randomization and control groups to isolate the effects of the intervention. Furthermore, to ensure a comprehensive and reliable analysis, only full-text articles published in English were included.

2.4. Exclusion Criteria

To maintain the review’s focus on the impact of guided imagery techniques on motor rehabilitation outcomes in stroke patients, several exclusion criteria were established. Studies were excluded if they investigated interventions unrelated to guided imagery, such as pharmacological approaches, or general physical rehabilitation where guided imagery was not the central intervention. Research targeting populations other than stroke patients, including studies involving mixed neurological conditions without a distinct analysis for stroke participants, was also excluded. Additionally, studies involving children or adolescents under 18 years of age, or those that did not clearly define motor impairments linked to strokes, were omitted to ensure relevance to the review’s objectives. Articles that failed to provide adequate detail on the structure, duration, or delivery of guided imagery protocols, or that did not use validated clinical, neurophysiological, or functional measures to assess outcomes, were excluded. Only RCTs were considered, meaning non-randomized studies, feasibility studies, observational research, longitudinal studies, retrospective studies, and study protocols were excluded to uphold methodological rigor and allow for reliable causal inferences. Reviews, theoretical papers, or meta-analyses were not included, as the review aimed to synthesize primary experimental evidence. Finally, studies published in languages other than English, or available only as abstracts, posters, or conference proceedings, were excluded due to the lack of comprehensive data. Research involving animal models or preclinical studies was also omitted, as the review’s focus was on clinical applications in human populations. This careful selection process ensured that the included studies provided robust, high-quality evidence relevant to stroke rehabilitation. Table 2 provides an overview of the methodology employed for this systematic review.

Table 2.

Detailed summary of the systematic review methodology.

3. Results

A comprehensive literature search was carried out using five electronic databases. This initial search yielded a total of 2370 records. Before formal screening commenced, 178 duplicate records were identified and removed, along with 76 non-English articles. This left 2116 records for title and abstract screening. Following this initial screening phase, 208 records were excluded based on inadequate study design, leaving 1908 reports for full-text retrieval. However, despite efforts to obtain these articles (e.g., emailing corresponding authors, consulting libraries, exploring open-access sources, checking institutional resources, and using research networks), 22 reports could not be retrieved. The remaining 1886 reports underwent a thorough assessment for eligibility. During this stage, a further 1785 reports were excluded based on title screening, and an additional 60 were excluded after abstract screening. This rigorous selection process resulted in a final set of 41 studies that met the pre-defined inclusion criteria and were therefore included in this review (Figure 1).

3.1. Quality of Included Studies—Risk of Bias

To ensure a thorough evaluation of methodological quality, we conducted a detailed assessment of bias risk using established and recognized tools specifically designed for the study design of the included papers [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. This systematic approach provided a robust framework for identifying potential limitations and inconsistencies in research methods, enabling a transparent and reliable comprehension of the findings within the broader context of evidence.

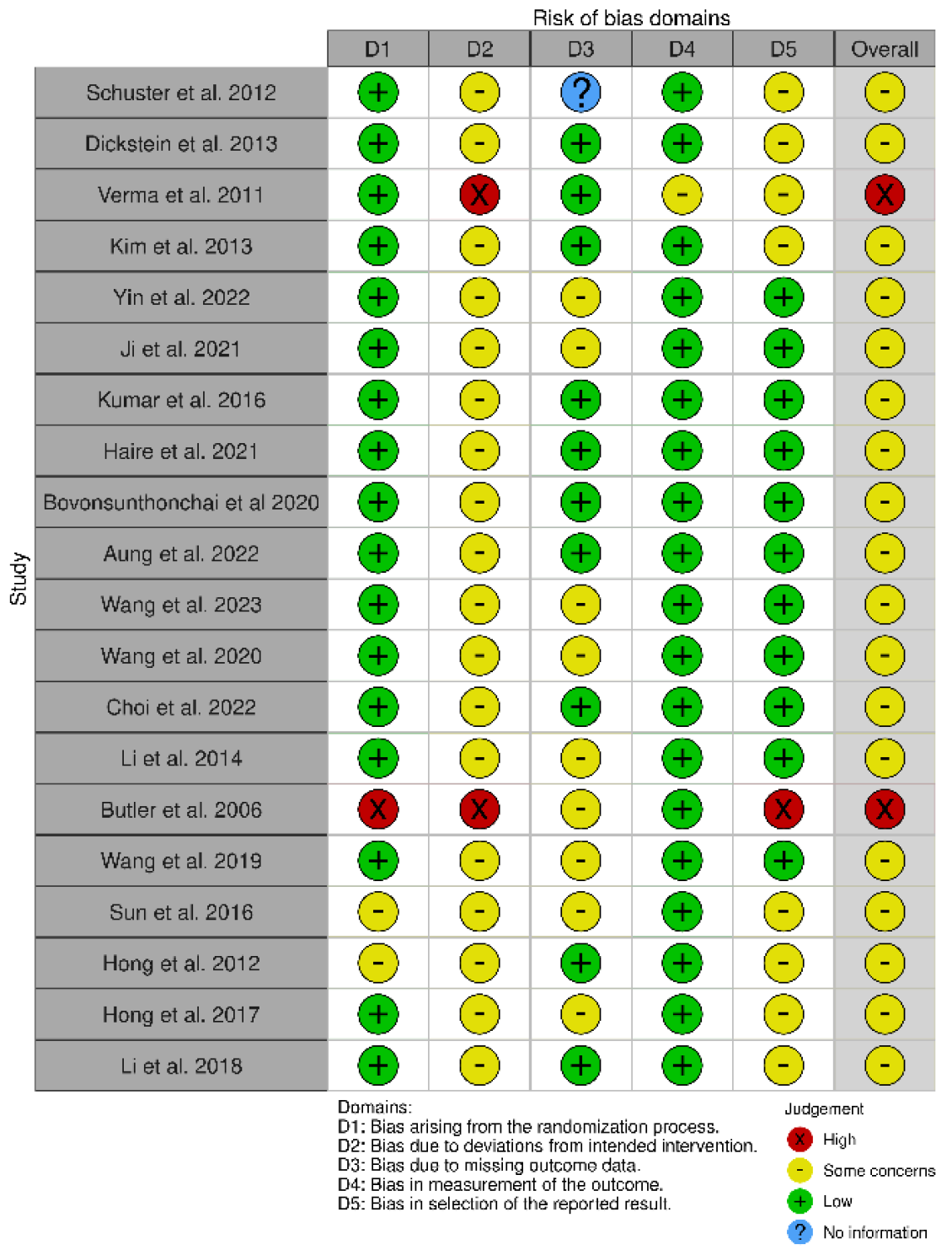

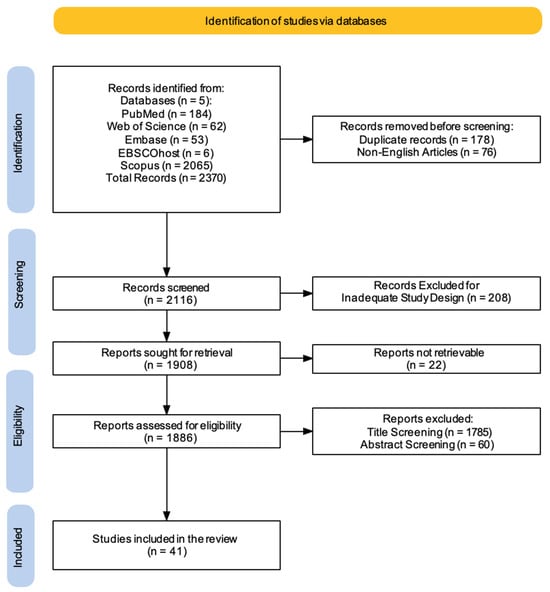

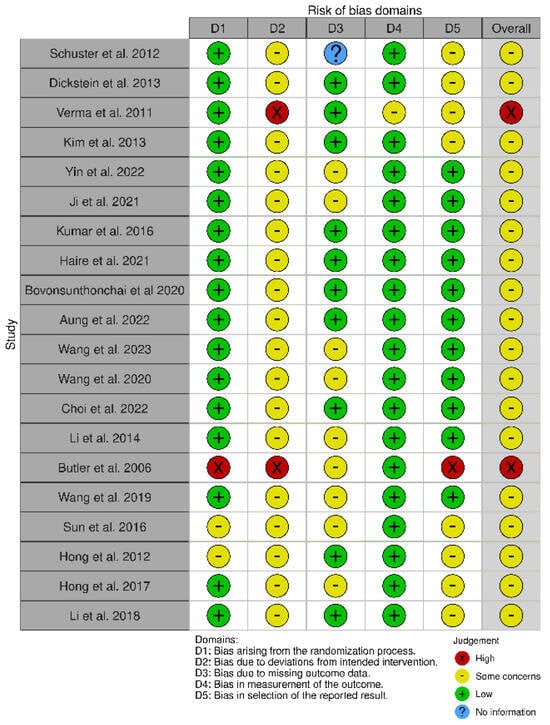

Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for Randomized Trials (RoB 2)

All forty-one studies were RCTs [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. We used the updated Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2) tool, which covers five domains: (i) bias arising from the randomization process, (ii) bias due to deviations from the intended intervention, (iii) bias due to missing data on the results, (iv) bias in the measurement of the outcome, and (v) bias in the selection of the reported result (Figure 2 and Figure 3) [96].

Figure 2.

Risk of Bias (RoB) of included RCT studies [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75].

Figure 3.

Risk of Bias (RoB) of included RCT studies [76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95].

The RoB 2 assessment revealed that most studies fell into the “some concerns” category for overall risk of bias, with only one study (Mihara et al. [65]) achieving a “low risk” rating across all domains. A notable trend emerged, with studies such as Ma et al. [53], Pichiorri et al. [56], Zafar et al. [57], and Ang et al. [58,59] consistently displaying “some concerns” in key domains, particularly related to deviations from intended interventions (D2) and selective reporting (D5). This pattern suggests recurring methodological limitations that may affect the reliability of their findings. Several common issues were observed across studies. Allocation concealment and randomization reporting were often insufficiently detailed, as seen in Luo [69] and Frolov et al. [70], increasing the risk of selection bias. Similarly, partial or poorly implemented blinding, particularly in studies relying on subjective outcome measures, was evident in Liu et al. [62] and Brunner et al. [63], raising concerns about performance and detection bias. The handling of missing data was another frequent challenge, with studies such as Wang et al. [86] and Wang et al. [87] providing limited transparency regarding their data management strategies. In certain cases, the risk of bias was more pronounced. Ang et al. [66] and Verma et al. [78] demonstrated high risk in multiple domains, including performance bias and selective outcome reporting, which significantly undermines the credibility of their conclusions. Butler et al. [90] also exhibited high risk across several domains, particularly in deviations from intended interventions and selective reporting, reflecting broader methodological concerns in early rehabilitation research. Interestingly, even among the stronger studies, concerns remained regarding selective reporting (D5). While Mihara et al. [65] demonstrated the most robust methodological rigor, studies such as Kang et al. [67] and Kim et al. [68] still exhibited “some concerns” in this domain, underscoring the need for improved transparency in reporting research outcomes. These findings carry significant implications for interpreting the existing body of evidence. The recognized methodological constraints, especially those concerning randomization and blinding, greatly affect how we interpret our results. Ambiguous or insufficient randomization methods could result in selection bias, possibly causing disparities between intervention groups that might influence study results. This constraint diminishes the certainty in assigning the observed effects exclusively to the interventions being studied. Likewise, insufficient blinding, particularly in research employing subjective outcome metrics, creates issues related to performance and detection bias. Expectations of participants and assessors can affect outcome evaluations, possibly exaggerating treatment effects. These biases together diminish the confidence in the evidence, complicating the assessment of the actual effectiveness of interventions. Thus, although our synthesis offers important perspectives on existing research trends, prudence is advisable when extending results to wider clinical applications. Tackling these methodological weaknesses in upcoming trials will be essential for reinforcing the evidence foundation and guaranteeing more dependable conclusions about the efficacy of neurorehabilitation approaches.

3.2. Synthesis of Evidence

All the 41 included studies investigated the application of guided imagery techniques, including MI for motor rehabilitation in strokes (see Table 3). Looking at the age ranges of participants, we found a normal distribution for stroke research, comprising middle-aged and older persons, with mean ages ranging from 50 to 70 years old in most studies. In evaluating the sample sizes of both the treatment and control groups, the studies showed a certain level of consistency. Although there was some fluctuation, the mean number of participants in both the treatment and control groups was roughly 20. This indicates that researchers usually sought comparable group sizes to ensure balance and consistency among interventions. Nonetheless, it is crucial to recognize that certain studies had smaller sample sizes, whereas others had larger ones, which could influence the statistical power of each study. Concerning sex distribution, the research typically indicated a larger share of male participants. On average, around 65% of the individuals in both the treatment and control groups were male. This higher incidence in males aligns with noted trends in stroke demographics, indicating that men are statistically more prone to having strokes compared to women. The duration of the intervention varied. Some studies used relatively brief treatments (a few weeks), whereas others used lengthier programs (many months). Furthermore, the studies used a variety of methods to evaluate upper extremity function, including both impairment-based measures like the Fugl–Meyer Assessment (FMA) and activity-based measures like the Action Research Arm Test (ARAT) and the Wolf Motor Function Test (WMFT). Furthermore, the examined research provided a mixed picture in terms of impact sizes and evidentiary certainty. Some studies suggested moderate to substantial benefits, particularly when guided imagery was paired with other treatments. The level of confidence in evidence also varies. Many studies are characterized as having “moderate” assurance of evidence. This frequently indicates research design flaws, such as limited sample numbers, a lack of blinding, or ambiguous randomization processes. The studies frequently integrate guided imagery with traditional physical therapy interventions, such as range of motion exercises, task-specific training, and constraint-induced movement therapy. This combination likely creates a synergistic effect, where guided imagery amplifies the benefits of conventional rehabilitation techniques. Essentially, guided imagery seems to prime the brain and nervous system for motor learning and functional improvement, making other therapies more effective.

Table 3.

Summary of the included studies.

To further investigate all the obtained results, we sequentially summarized the primary insights regarding how guided imagery techniques impact motor stroke rehabilitation [55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. The first fifteen studies analyzed MI in stroke rehabilitation [57,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85]; the other eleven articles investigated the combined use of MI and BCI [55,56,58,59,60,62,63,66,68,69,70]. Five studies investigated the impact of neurofeedback and non-invasive brain stimulation techniques combined with MI [61,64,65,67,71], while the last ten papers explored the neuroplastic effects of MI [86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95].

Safety and Adverse Events

Across the multiple RCTs investigating MI for stroke rehabilitation, MI treatments, whether used alone or in combination with other therapies, consistently show a positive safety profile. No serious adverse events were directly attributable to MI in any of the reviewed studies. While some research incorporated combined interventions like MI with robotic therapy, BCIs, functional electrical stimulation (FES), or non-invasive brain stimulation (e.g., tDCS, TMS), these additions did not introduce significant safety concerns beyond the known risks associated with the individual components themselves. The most commonly reported “adverse events” were related to the underlying condition of the stroke (e.g., falls, pain, fatigue, muscle soreness, or discomfort related to other concurrent therapies), rather than the MI intervention. Generally, MI protocols, including those focused on gait, upper limb function, and other motor recovery domains, were well tolerated by participants. Although detailed safety data may not have been the primary focus of every study, the accumulated evidence strongly suggests that MI-based rehabilitation is a safe and well-tolerated approach for stroke patients. No consistent pattern of adverse events related specifically to MI emerged from the analyzed literature.

3.3. Motor Imagery in Stroke Rehabilitation: Gait, Upper Limb Function, and Beyond

A growing body of research highlights the potential of MI as a valuable tool in stroke rehabilitation, with numerous studies exploring its impact on various aspects of motor recovery. A first RCT (n = 44 stroke patients, n = 27 healthy controls) looked at the effect of MIT on gait recovery in sub-acute stroke patients. After six weeks, the MIT group, who received normal therapy as well as 30 min daily MIT sessions, improved their gait velocity much more than the muscular relaxation group. While all groups improved lower extremity function, the MIT group had greater increases in kinesthetic MI capacity [72]. Another RCT (n = 10 MI, n = 15 action observation, n = 11 action execution) explored the impact of MI on the autonomic nervous system (ANS) during walking in chronic stroke patients. While action execution significantly increased heart rate and decreased the mean RR interval, indicating ANS activation, MI did not elicit significant changes in ANS activity [73]. Cho et al. examined the impact of MIT combined with gait training on balance and gait (n = 28 chronic stroke patients). The experimental group (n = 15) received both MIT and gait training, while the control group (n = 13) received only gait training. After six weeks, the MIT group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in functional reach, timed up-and-go, 10 m walk, and FMA scores compared to the control group [74]. An RCT investigated the effectiveness of MIT on upper limb motor recovery (n = 121 stroke patients). Participants were assigned to either an MIT group, an attention-placebo control group, or a normal care control group. While all groups showed improvement, no significant differences in recovery (ARAT score, grip strength, manual dexterity) were found between the MIT group and the control groups after four weeks of training [75]. Schuster and colleagues investigated the impact of embedded or added MIT on a complex motor task (“Going down, laying on the floor, and getting up again”) (n = 41 stroke patients). While all groups (embedded MI, added MI, control) improved their performance time on the task after a two-week intervention, no significant differences were found between the groups [76]. Dickstein and his team examined the impact of integrated MI on ambulation (n = 23 community-dwelling stroke survivors). Participants received either integrated MI or a control treatment (upper extremity exercises) for four weeks, with the control group crossing over to integrated MI in the second phase. Integrated MI significantly improved indoor walking speed compared to the control treatment, with gains maintained at follow-up. However, no significant improvements were observed in community ambulation or fall-related self-efficacy [77]. Verma et al. investigated the impact of task-oriented circuit class training (TOCCT) combined with MI on gait rehabilitation (n = 30 subacute stroke patients). The experimental group (n = 15) received MI followed by TOCCT, while the control group (n = 15) received conventional Bobath-based therapy. After two weeks, the MI + TOCCT group showed significantly greater improvements in functional ambulation, gait speed, endurance, and gait quality compared to the control group [78]. Kim and colleagues compared action observation training (AOT), MIT, and physical training on dynamic balance and gait (n = 27 chronic stroke patients). Participants received 4 weeks of training. AOT showed significant improvements compared to physical training in the timed up-and-go (TUG) test, gait speed, cadence, and single limb support. While both AOT and MIT improved dynamic balance and gait, AOT demonstrated superior gains, suggesting that visually learning movements enhances motor recovery more effectively than MI alone [79]. Yin and his team explored the impact of MIT combined with conventional rehabilitation on lower limb motor recovery (n = 32 chronic stroke patients). The experimental group received MIT in addition to standard care, while the control group received only standard care. After six weeks, the MIT group showed significantly greater improvements in lower extremity motor function, balance, and activities of daily living compared to the control group [80]. Another RCT investigated the impact of a home-based graded motor imagery (GMI) program on upper limb motor function (n = 37 chronic stroke patients). The GMI group received implicit MI, explicit MI, and mirror therapy, while the control group received conventional therapy only. After 8 weeks, the GMI group showed significantly greater improvement in upper limb motor function compared to the control group, suggesting that GMI can be a useful adjunct to conventional rehabilitation for improving upper extremity function post-stroke [81]. Kumar and colleagues examined the effect of adding MI to task-oriented training on paretic lower extremity muscle strength and gait performance (n = 40 ambulant stroke patients). The experimental group received MI training with audio guidance in addition to task-oriented exercises, while the control group received task-oriented exercises alone. After three weeks, the MI group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in hip flexor/extensor strength, knee extensor strength, ankle dorsiflexor strength, and gait speed compared to the control group [82]. Haire et al. investigated the effects of therapeutic instrumental music performance (TIMP) with and without MI on cognitive and affective outcomes (n = 30 chronic stroke patients). Participants were assigned to TIMP only, TIMP with cued MI (TIMP + cuedMI), or TIMP with MI (TIMP + MI) groups. The TIMP + MI group showed significant improvement in cognitive flexibility, while the TIMP + cuedMI group demonstrated significant positive affect changes [83]. An RCT investigated the effects of MI combined with structured progressive circuit class therapy (SPCCT) on gait and muscle strength (n = 40 stroke patients). The experimental group received MI training before SPCCT, while the control group received health education before SPCCT. After 4 weeks, the MI group showed significantly greater improvements in gait speed, cadence, step length, and hip/knee extensor strength compared to the control group [84]. Aung et al. investigated the impact of MI combined with SPCCT on functional mobility (n = 40 post-stroke patients). The experimental group received MI before SPCCT, while the control group received health education before SPCCT. After 4 weeks, the MI group demonstrated significantly greater improvements in step test scores (affected and unaffected limbs), 6 min walk test distance, and TUG test performance compared to the control group [85]. An RCT involved 29 stroke patients (15 in the experimental group, 14 in the control group) who completed an 8-week intervention. The experimental group received MI along with traditional motor rehabilitation, while the control group received only the latter. Results showed significant improvements in mobility, balance, and fall risk in the MI group [57]. The findings underscore the potential of MI as a valuable adjunct to conventional rehabilitation approaches for individuals seeking to regain motor function after stroke.

3.4. Brain–Computer Interface and Motor Imagery for Stroke Rehabilitation: An Overview of Clinical Studies

Several RCTs have investigated the efficacy of MI-based BCI rehabilitation for stroke patients, with varying results. A first RCT investigated the effects of MI-based BCI rehabilitation on upper limb motor function and brain activation (n = 40 chronic stroke patients). The experimental group received MI-BCI training combined with conventional therapy, while the control group received conventional therapy alone. Post-intervention, the MI-BCI group showed significant improvement in upper extremity motor function compared to the control group, accompanied by increased activation in motor-related brain regions during motor execution and imagery tasks [55]. Pichiorri et al. investigated the impact of BCI-supported MI training on upper limb motor recovery (n = 28 subacute stroke patients). Participants were assigned to either a BCI-supported MI group or a control group receiving MI training alone. After 1 month, the BCI group showed a trend towards greater improvement in the primary outcome measure, the arm section of the FMA, compared to the control group, suggesting that the added BCI assistance may enhance the benefits of MI for motor rehabilitation [56]. Ang and his team explored the impact of BCI-based MI training combined with robotic therapy on upper limb motor function (n = 26 chronic stroke patients). The experimental group received BCI-MI training with robotic feedback, while the control group received robotic therapy alone. After 4 weeks, both groups showed significant improvements in upper limb motor function, with no significant difference between groups, suggesting that BCI-MI training may offer comparable benefits to robotic therapy with fewer repetitions [58]. Another RCT investigated the effects of tDCS combined with MI-based BCI and robotic therapy on upper limb motor recovery (n = 19 chronic stroke patients). Participants were assigned to either a tDCS with MI-BCI and robotic therapy group or a sham-tDCS group. While both groups showed motor function improvements after 2 weeks of intervention, no significant difference was observed between the groups. However, the tDCS group demonstrated significantly higher online accuracy in MI-BCI performance and a higher event-related desynchronization laterality coefficient, suggesting that tDCS may facilitate MI in chronic stroke patients [59]. Another paper investigated the ability to operate an EEG-based MI-BCI and the efficacy of MI-BCI with robotic feedback on motor recovery (n = 54 BCI-naïve hemiparetic stroke patients). Results showed that 89% of patients could operate the MI-BCI better than chance, with no correlation between MI-BCI ability and baseline motor function. A subset of these patients (n = 26) was then randomized into either the MI-BCI with robotic feedback group or the robotic rehabilitation group. While the robotic rehabilitation group showed earlier motor function improvements, both groups achieved significant improvements post-rehabilitation and at 2-month follow-up, with no significant difference between groups [60]. Liu and colleagues investigated the effects of MI-based BCI training combined with conventional rehabilitation on upper limb motor function and attention (n = 60 subacute stroke patients). The experimental group received MI-BCI training with FES in addition to conventional therapy, while the control group received conventional therapy alone. After 3 weeks, the MI-BCI group showed significant improvements in upper limb motor function and attention compared to the control group [62]. Brunner and his team investigated the effects of BCI training on upper limb motor recovery (n = 40 acute stroke patients). The experimental group received BCI training with FES as part of their standard upper limb rehabilitation, while the control group received standard rehabilitation alone. After 3 months, both groups showed improvements in upper limb motor function, but no significant difference was found between the groups. However, EEG analysis in the BCI group revealed significant changes in brain activity associated with MI [63]. A clinical trial (n = 19 BCI-naïve hemiparetic stroke patients recruited; 5 completed 10 rehabilitation sessions) is investigating the effects of tDCS combined with MI-based BCI and robotic feedback on upper limb stroke rehabilitation. Preliminary results from the completed sessions show no significant difference in the online accuracy of MI detection between the tDCS and sham-tDCS groups. However, offline analysis suggests that the tDCS group may exhibit higher accuracy in classifying MI compared to the sham group, hinting at a potential facilitating effect of tDCS on MI, although this requires further investigation with a larger sample size. The study also found that 68% of the stroke patients screened were able to operate the MI-BCI better than chance [66]. Kim et al. investigated the effects of MI-contingent BCI training on upper limb function and neural connectivity (n = 25 chronic stroke patients). The experimental group received BCI training with FES contingent on successful MI, while the control group received FES independent of MI. After 4 weeks, the MI-contingent group showed significant improvements in wrist extensor muscle strength compared to the control group. Additionally, this group exhibited increased neural connectivity in brain regions associated with motor control [68]. Another RCT investigated the effects of BCI rehabilitation combined with conventional rehabilitation on lower limb motor function (n = 64 acute ischemic stroke patients). The experimental group received BCI-controlled electrical stimulation in addition to conventional rehabilitation, while the control group received conventional rehabilitation alone. After 2 weeks, the experimental group showed significantly greater improvements in lower limb motor function, walking ability, and activities of daily living compared to the control group [69]. Frolov and his team investigated the effects of BCI training combined with a hand exoskeleton on upper limb motor recovery (n = 74 subacute and chronic stroke patients). The experimental group received BCI-controlled exoskeleton training, where the exoskeleton’s movements were contingent on the patient’s MI, while the control group received passive exoskeleton movements. After 10 sessions, the BCI group showed significant improvements in hand function (grasp, pinch, gross movements) compared to the control group, highlighting the role of MI in driving motor recovery through BCI-mediated feedback. While overall arm function improved in both groups, the BCI group demonstrated greater gains in hand-specific tasks [70]. Collectively, these studies suggest that MI-BCI can be a valuable tool for stroke rehabilitation, but its optimal implementation and comparative effectiveness relative to other therapies require additional investigation.

3.5. The Impact of Augmented Motor Imagery on Post-Stroke Rehabilitation: Exploring Neurofeedback and Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation Techniques

A variety of studies have explored the use of neurofeedback and non-invasive brain stimulation techniques in conjunction with MI to enhance upper limb motor recovery in stroke patients. A pilot study investigated the effects of MI with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) neurofeedback on upper limb motor recovery in 20 subcortical stroke patients. Participants were randomized into two groups: one receiving real-time feedback of their brain activity during MI (REAL group) and a control group receiving sham feedback (SHAM group). After a two-week intervention (three sessions/week), the REAL group showed significant improvements in hand/finger function (FMA) compared to the SHAM group, suggesting that NIRS-guided MI enhances motor recovery by increasing activation in the ipsilesional premotor area [61]. Kasho et al. investigated the effects of combining visual motor imagery (VMI) with tDCS on upper limb motor recovery in 64 chronic stroke patients. Participants were assigned to either a VMI-plus-tDCS group or a VMI-only control group. Results showed significant improvements in both the FMA and the ARAT scores in the combined VM” and’tDCS group compared to the control group, indicating that the addition of VM” and’tDCS enhances motor rehabilitation outcomes. Specifically, the combined therapy group demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in upper limb function [63]. Mihara and colleagues (n = 54) investigated the impact of functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) neurofeedback combined with gait and balance-related MI on post-stroke gait disturbances. The real feedback group, receiving genuine neurofeedback of their supplementary motor area (SMA) activity during MI, showed significantly greater improvement in the TUG test compared to the sham feedback group [65]. Kang et al. (n = 17) investigated the effects of combining low-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (LF-rTMS), audio-based MI, and electrical stimulation (ES) on upper extremity motor recovery in subacute stroke patients. The experimental group, receiving LF-rTMS, audio-based MI, and active ES, showed significantly greater improvement in the FMA scores compared to the control group, which received LF-rTMS, audio-based MI, and sham ES [67]. One last RCT (n = 42) explored the effects of combining LF-rTMS with audio-based MI on upper limb motor recovery in chronic stroke patients. The experimental group, receiving LF-rTMS and MI, demonstrated significantly greater improvements in the WMFT, FMA, MBI, and Box and Block Test compared to the control group, which received LF-rTMS and audiotape-led relaxation [71]. The findings suggest that integrating MI with techniques like NIRS, tDCS, and rTMS may enhance motor recovery beyond what is achievable with MI alone, although further research is needed to optimize these interventions.

3.6. Neuroplastic Effects of Motor Imagery Training in Stroke Rehabilitation: Evidence from RCTs

Recent studies have explored the efficacy of MI-based interventions in improving upper limb function and promoting cortical reorganization in stroke patients. An RCT (n = 39 patients) investigated the effects of MIT combined with conventional rehabilitation on upper limb motor recovery and associated brain activity in chronic stroke patients. The MIT group showed significantly greater improvements in the upper extremity Fugl–Meyer score compared to the control group receiving only conventional rehabilitation. Task-based fMRI revealed that MIT led to decreased compensatory brain activation in the contralesional sensorimotor cortex and increased functional connectivity within the ipsilesional hemisphere, specifically between the ipsilesional M1 and putamen, correlating with clinical improvements [86]. Wang et al. examined the impact of MIT on brain activity and motor recovery in 31 stroke patients. The MIT group, receiving MIT in addition to conventional rehabilitation, showed significantly greater improvement in the FM-UL score compared to the control group. fMRI analysis revealed that MIT increased activity in the ipsilesional inferior parietal lobule (IPL) and enhanced functional connectivity between the IPL and other brain regions associated with motor planning and learning [87]. Choi et al. investigated the impact of combining AO with MI on upper extremity function and corticospinal activation in 45 subacute stroke patients. The experimental group, receiving AO with MI, showed significantly greater improvements in the FMA-UE and Motor Activity Log compared to the control group receiving AO alone. While both groups showed increased motor-evoked potentials amplitude, the AO with MI group demonstrated a significantly greater change [88]. Li et al. investigated the impact of an MI-based BCI combined with FES on upper extremity motor recovery in 15 subacute stroke patients. The BCI-FES group showed significant improvements in both FMA and ARAT scores after 8 weeks of training. Furthermore, this group exhibited stronger event-related desynchronization in the affected sensorimotor cortex, suggesting increased neural activity related to MI [89]. A pilot study explored the effects of mental practice combined with constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) on upper extremity motor recovery in four stroke patients. One patient receiving CIMT alone showed improvements in motor function and increased bilateral cortical activation. Another patient, receiving only mental practice, showed slight improvements in some measures but they were not clinically meaningful. Two patients receiving combined CIMT and mental practice showed improvements in motor function and mental imagery abilities, with one exhibiting focal contralateral activation in the motor cortex [90]. An RCT investigated the effects of MIT combined with conventional rehabilitation therapy (CRT) on motor recovery in 31 subcortical stroke patients. The MIT group showed significantly greater improvement in Fugl–Meyer Upper Limb scores compared to the CRT-only group. fMRI analysis revealed increased functional connectivity within specific brain regions related to MI and learning in the MIT group, along with an increased clustering coefficient, suggesting improved local information processing efficiency [91]. Sun et al. investigated the impact of MIT combined with CRT on motor recovery in 18 chronic stroke patients with severe hemiparesis. The MIT group showed significantly greater improvement in Fugl–Meyer Upper Limb scores compared to the CRT-only group after 4 weeks. fMRI analysis revealed two patterns of cortical reorganization: increased activation in the contralateral sensorimotor cortex and a focusing of activation in the same section with an increased laterality index [92]. Hong and colleagues compared the effects of mental imagery training combined with electromyography-triggered electrical stimulation (MIT-EMG) to FES alone on motor recovery in 14 stroke patients. The MIT-EMG group showed significantly greater improvement in the upper extremity component of the FMA compared to the FES group. MIT-EMG also led to increased cerebral glucose metabolism in specific brain regions associated with motor control, suggesting that MI facilitated cortical reorganization and enhanced motor recovery [93]. Another study with 19 patients investigated the combined effects of MI-BCI training and tDCS on motor recovery after stroke. While both MI-BCI with tDCS and MI-BCI with sham-tDCS groups showed improved motor function, there was no significant difference between the groups. However, the tDCS group exhibited increased white matter integrity in brain regions associated with motor control and enhanced cerebral blood flow in the sensorimotor cortex, suggesting that tDCS may have further promoted neuroplasticity [94]. One last RCT investigated the effects of MIT combined with traditional rehabilitation versus traditional rehabilitation alone on hand function in 20 stroke patients. The traditional rehabilitation group showed significantly greater improvement in ARAT and FMA scores compared to the traditional-rehabilitation-alone group after 4 weeks. Additionally, the traditional-rehabilitation group exhibited increased motor-evoked potentials amplitude and improved white matter integrity in the dorsal pathways, suggesting that MIT enhanced motor recovery by promoting neuroplasticity in these pathways [95]. The observed improvements in motor function and neural connectivity highlight the potential of MI as a complementary approach in post-stroke rehabilitation.

4. Discussion

MI has become a promising method in post-stroke rehabilitation, especially for enhancing gait speed, postural stability, and upper limb performance. When used alongside traditional rehabilitation, MI seems to improve motor recovery, though its effectiveness differs based on intervention intensity, patient involvement, and methodological aspects. Although certain studies indicate notable functional improvements, others propose that MI might not provide any extra advantages beyond traditional therapy, emphasizing the necessity for more standardized protocols and personalized treatment methods. Aside from motor function, MI’s effects on autonomic regulation and cognitive flexibility are still minimal when utilized alone. Nevertheless, when combined with multisensory feedback, like action observation or therapeutic music, it might enhance cognitive and emotional health. This indicates that MI’s possibilities go beyond motor recovery, affecting wider elements of neurorehabilitation. The combination of MI and BCI technology has yielded encouraging outcomes, especially in the rehabilitation of upper limbs, exhibiting significant enhancements in motor functions and cortical activation. Nonetheless, comparative research shows that MI-BCI training yields results comparable to robotic-assisted therapy, indicating that its effectiveness may rely on personal neuroplasticity, commitment, and the particular rehabilitation setting.

4.1. From Theory to Practice: Integrating Mental Imagery for Improved Motor Function

Our comprehensive synthesis significantly builds upon a growing body of literature that highlights the benefits of guided imagery in stroke rehabilitation, yet it explicitly addresses a critical gap: the specific impact of these techniques on motor recovery. Although previous studies have reported overall improvements in patient outcomes, such as enhanced quality of life and reduced anxiety [97,98], few have systematically focused on quantifying the motor benefits that guided imagery can provide. In many cases, the literature has concentrated on general rehabilitation outcomes rather than delineating the precise mechanisms and efficacy in enhancing motor function [99]. Our work not only confirms the positive trends observed in earlier investigations [100] but also offers a more detailed synthesis of how guided imagery can be optimally integrated with conventional therapeutic modalities to improve motor recovery in stroke patients. The evidence consistently supports the use of MI as a valuable adjunct to traditional rehabilitation approaches, with significant improvements in key motor functions. For instance, several studies have demonstrated that MI, when incorporated into task-oriented exercises or circuit class therapies, significantly improves lower extremity strength, functional mobility, and overall gait quality, highlighting the importance of this approach in enhancing functional independence post-stroke [78,81]. Moreover, our synthesis underscores the varying effects of MIT depending on its integration into different rehabilitation strategies. In particular, the addition of MI to SPCCT has been shown to boost muscle strength, particularly in the hip, knee, and ankle regions, as well as improve gait speed and step length, resulting in more efficient ambulatory patterns [84]. This suggests that MI not only enhances motor performance in terms of voluntary movement control but also contributes to muscle strengthening, which is critical for improving functional mobility in stroke survivors. Similar improvements were observed when MI was combined with task-oriented training for paretic lower extremities, where significant enhancements in muscle strength and gait performance were recorded, particularly in patients with chronic stroke [82]. The benefits of MI are not limited to physical function; the integration of MI with therapies such as TIMP also demonstrates positive effects on cognitive and emotional outcomes, such as cognitive flexibility and affective responses [83]. This multidimensional impact of MI suggests that its role extends beyond purely motor recovery and may also contribute to enhancing quality of life by addressing emotional and cognitive aspects of rehabilitation. This approach bridges the gap by mapping out the specific delivery methods and intervention protocols that are most effective, thereby providing clinicians with actionable insights and reinforcing the notion that guided imagery can be a critical adjunct in stroke rehabilitation programs.

4.2. Bridging the Gap Between Intention and Execution: The Impact of BCI-Based Motor Imagery in Stroke Recovery

The incorporation of advanced technologies such as BCIs, robotics, and non-invasive brain stimulation into guided or MI protocols represents a transformative development in the field of stroke rehabilitation. BCI-based MIT leverages real-time neural feedback to dynamically engage and reinforce motor pathways, potentially accelerating the recovery process [101]. BCI-based MIT has been widely explored for its potential to enhance neuroplasticity and promote motor recovery. But how does it compare to traditional approaches? On one hand, numerous studies suggest that BCI-MI therapy can significantly improve upper limb function after a stroke, particularly in patients with severe impairments [55,56,58]. By decoding brain activity in real time, BCI provides immediate feedback, reinforcing neural pathways associated with movement. Theoretically, this should accelerate motor relearning, but does it always work in practice? Some RCTs, such as Ma et al. [55], Pichiorri et al. [56], Ang et al. [58], and Liu et al. [62], explored in this review have demonstrated superior recovery rates with BCI-MI compared to standard therapy, particularly when combined with FES or robot-assisted rehabilitation. There is compelling evidence that the integration of these instruments into these protocols could offer significant enhancements in motor performance, particularly in terms of gait dynamics and upper limb strength. This suggests that BCI does not just train the brain; it helps bridge the gap between intention and execution. However, other studies indicate no significant differences between BCI-MI and conventional therapy, leading to questions about who benefits most from these interventions [59,60,66]. Are we seeing a true neuroplastic effect, or are the improvements simply a result of increased patient engagement? These mixed findings underscore the complexity of translating neurotechnological advancements into clinically effective interventions. One critical factor to consider is inter-individual variability; not all patients exhibit the same capacity for MI, and differences in brain lesion location, cognitive function, and neural plasticity could influence the effectiveness of BCI training. This raises the question of whether BCI should be tailored to specific patient subgroups rather than being applied as a one-size-fits-all approach. Moreover, the observed improvements might not be solely attributable to neuroplastic changes. Some researchers argue that the intensive, engaging nature of BCI training itself could drive functional recovery, irrespective of the neural mechanisms involved. If this is the case, how much of the benefit comes from BCI-specific processes, and how much is due to increased patient motivation and participation? Addressing these uncertainties requires well-designed, large-scale clinical trials that not only compare BCI-MI to conventional therapy but also explore its long-term sustainability. While short-term gains have been reported, do these improvements translate into lasting functional independence, or do they plateau once therapy ends? Furthermore, cost-effectiveness and accessibility remain key barriers to widespread clinical implementation; without solutions to these challenges, BCI-based rehabilitation may remain confined to research settings rather than becoming a standard clinical tool. Thus, while the integration of BCI into MI therapy represents an exciting frontier, the current body of evidence suggests that we are not yet at a definitive paradigm shift. Instead, we are at a crucial stage of refinement and validation, where the next steps will determine whether BCI-based rehabilitation can truly revolutionize stroke recovery or remain an adjunct therapy for select cases. Future research should focus on identifying clear biomarkers for patient selection, optimizing training protocols, and ensuring real-world applicability to fully harness the potential of these technologies. Emphasis should also be placed on longitudinal studies to assess the sustainability of these improvements over time, as well as on exploring the cost-effectiveness and scalability of technology-integrated rehabilitation programs in diverse clinical settings.

4.3. Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Motor Imagery in Stroke Recovery Through Neuroplastic Changes

The neuroplastic effects induced by guided imagery techniques are increasingly recognized as a cornerstone of their therapeutic potential in stroke rehabilitation. Several studies have provided robust evidence that MIT can facilitate significant neurophysiological changes, which in turn contribute to motor recovery [86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95]. For example, research by Wang et al. [87] revealed that guided imagery not only enhances activation in motor-related areas of the ipsilesional cortex but also improves functional connectivity within the motor network. Similarly, Choi et al. [88] demonstrated that combining AO with MI resulted in a more pronounced increase in motor-evoked potentials, suggesting that these interventions stimulate compensatory neural mechanisms. Li et al. [89] further corroborated these findings by showing that integrating a BCI-FES approach with MI leads to greater event-related desynchronization in affected cortical regions, thereby providing objective neurophysiological evidence of enhanced cortical reorganization. These neuroplastic adaptations are vital, as they indicate the brain’s ability to reorganize and form new neural connections in response to rehabilitation, ultimately supporting improved motor function. These findings align with the growing body of literature supporting the role of neuroplasticity in stroke recovery [102,103,104]. The enhanced functional connectivity, increased activity in motor-related areas, and improvements in motor function reported in these studies underscore the potential of MI as a robust therapeutic tool [87,88,89]. Clinical applications of these neuroplastic effects in motor rehabilitation are promising. For example, integrating MIT into conventional rehabilitation protocols could improve outcomes for patients with both chronic and subacute strokes by enhancing motor recovery and accelerating the reorganization of the sensorimotor cortex [105]. Furthermore, the use of imagery-based interventions, in combination with AO or tDCS, holds the potential to improve neural efficiency and function even in patients with severe hemiparesis, where traditional approaches may have limited efficacy. Future research should focus on leveraging advanced neuroimaging techniques, such as fMRI and diffusion tensor imaging, to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying these changes. Additionally, there is a need for studies that explore individualized guided imagery protocols based on patients’ unique neurophysiological profiles, thereby optimizing the intervention’s effectiveness and contributing to the development of personalized rehabilitation strategies that could dramatically improve long-term functional outcomes.

4.4. The Strength of Evidence: Methodological Challenges and Future Pathways in Guided Imagery Research

While this review encompasses extensive work focused solely on treating strokes through guided imagery, including MI, the overall confidence in the resulting evidence remains moderate, indicating a need for caution. It is still uncertain whether the support can be provided solely for the use of MI. Although trials typically indicate positive effects, especially when used alongside standard treatment, there are not enough high-quality data to recommend its exclusive use. This is in part due to the relative scarcity of trials that compare the exclusive use of MI with various forms of intervention or against the treatment/no-treatment controls. Furthermore, methodological issues such as limited sample sizes, lack of blinding, and inconsistent randomization add to the complexity of the situation. To determine the genuine effectiveness of the sole use of MI, future research must adopt more rigorous study designs, such as those involving adequately sized groups following identical protocols and those employing blinded trials. One major challenge is the inconsistency in reported benefits. Some report a moderate to considerable improvement, whereas others indicate no notable change. Several factors likely contribute to these mixed results. Firstly, the location and severity of the stroke, along with the duration following the stroke, significantly differ across studies and influence the patient response to MI. Secondly, the approach to treating MI differs greatly—some use brief and mild interventions while others implement structured and intensive therapies. Third, researchers assess motor improvement differently: some prioritize impairment-based measures (like the FMA), while others prioritize activity-based measures (such as the Action Research Arm Test). These obstacles complicate drawing study conclusions and make it challenging to align study results. Another problem is the heterogeneity of the included studies, which restricts the capacity to conduct a significant meta-analysis. In the absence of a standardized method for defining participant traits, intervention procedures, and outcome metrics, synthesizing results to offer clear clinical direction becomes difficult. Upcoming studies should strive for enhanced methodological consistency, explicitly detailing MI protocols, outlining target populations, and employing validated, standardized assessment instruments to enhance comparability between studies. Even with these obstacles, there is thrilling potential in merging guided imagery with new technologies such as BCI, neurofeedback, and non-invasive brain stimulation. These methods might improve the efficacy of MI, yet significant questions persist: What are the best parameters (frequency, duration, intensity) for combining MI with technology? In what ways can these interventions be tailored to meet the specific needs of individual patients? What are the neural processes that account for the noticed advantages? In what ways does the treatment using combined MI technology differ from MI by itself or technology by itself? What are the lasting impacts on motor skills and overall well-being? Answering these queries will be crucial for establishing evidence-based protocols that enhance the clinical effectiveness of guided imagery in stroke recovery. Although MI shows potential, its complete capability can only be unlocked through robust, well-structured research that enhances its application and pinpoints its most efficient use cases.

4.5. Strengths and Limitations

This systematic review presents a comprehensive and rigorous approach to understanding the effects of guided imagery rehabilitation on motor recovery among individuals with stroke. The strengths of the review are evident in its methodological design, transparency, and the thoroughness with which the search strategy was implemented. By systematically searching multiple well-regarded databases such as PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, EBSCOhost, and Scopus, the review captures a wide range of relevant studies, ensuring a diverse and high-quality representation of the field. This comprehensive approach enhances the likelihood of capturing all relevant research, thereby minimizing potential biases associated with an overly narrow scope. Another significant strength of the review lies in its rigorous assessment of the risk of bias, using established frameworks like the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2 tool for randomized trials. A notable strength of this review is its focus on the integration of guided imagery with other cutting-edge rehabilitation technologies, such as BCIs, robotic devices, and non-invasive brain stimulations. By examining how guided imagery can be combined with these technologies, the review highlights the potential for synergistic effects and more effective rehabilitation outcomes. This focus on technology integration is particularly relevant in the context of modern rehabilitation practices, where technology plays an increasingly important role. Furthermore, the review delves into the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying the benefits of guided imagery. By exploring how guided imagery can influence brain plasticity, cortical excitability, interhemispheric balance, and functional connectivity, the review provides valuable insights into the therapeutic potential of this technique. This emphasis on the neurophysiological aspects of guided imagery is crucial for understanding how it works and for developing more targeted and effective interventions. Moreover, the review emphasizes the safety of this approach, highlighting that guided imagery is a non-invasive, low-risk intervention that can be seamlessly integrated into conventional rehabilitation protocols without posing significant risks to patients. Given its passive nature, guided imagery does not require physical exertion, making it particularly suitable for individuals with severe motor impairments or those at risk of secondary complications from intensive physical training.

However, this review also has limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. While the comprehensive search strategy is a strength, the restriction to English-language publications introduces the possibility of language bias. Potentially valuable research published in other languages may have been excluded, which could limit the generalizability of the review’s conclusions, particularly if non-English studies report different findings or highlight unique cultural or contextual factors relevant to guided imagery interventions. Another limitation stems from the heterogeneity of the included studies. While the review focused on RCTs to maximize methodological rigor, variations in intervention protocols (e.g., type of guided imagery, duration and frequency of sessions, combination with other therapies), participant characteristics (e.g., stroke severity, time since stroke, comorbidities), and outcome measures pose a challenge for synthesizing the data and drawing definitive conclusions about the effectiveness of guided imagery. This heterogeneity makes it difficult to conduct a meta-analysis to quantitatively pool the results of the included studies. While the narrative synthesis approach adopted in the review addresses this limitation to some extent by providing a qualitative overview of the findings, it also acknowledges the inherent complexities in comparing and contrasting studies with diverse methodologies. Finally, the review acknowledges the inherent challenge of definitively linking observed improvements in motor function directly to guided imagery itself. As many studies combined guided imagery with other rehabilitation interventions, such as conventional physical therapy or occupational therapy, it can be difficult to isolate the specific contribution of guided imagery to the observed outcomes.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, guided imagery, particularly MI, shows promise as a valuable adjunct in stroke rehabilitation, potentially enhancing motor recovery across various domains like gait, upper limb function, and balance. Combining MI with technologies like BCIs, robotics, and neurofeedback may further optimize outcomes by leveraging neuroplasticity mechanisms. While the evidence suggests positive trends, methodological limitations in many studies, including risk of bias and heterogeneity, necessitate cautious interpretation. Future research should prioritize rigorous, large-scale RCTs with standardized protocols and long-term follow-ups to solidify these findings and establish best practices. Ultimately, personalized guided imagery interventions, tailored to individual patient needs, hold significant potential for improving post-stroke motor rehabilitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., A.M. (Alfredo Manuli) and F.A.A.; methodology, F.A.A., A.M. (Alfredo Manuli), S.C. and A.M. (Annalisa Militi); validation, A.C., M.G.M., A.M.D.N., S.P., S.C. and F.A.A.; resources, R.S.C., M.G.M., A.M. (Alfredo Manuli) and A.M. (Annalisa Militi); data curation, A.M.D.N., A.M. (Alfredo Manuli), S.P., S.C. and M.G.M.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and F.A.A.; writing—review and editing, R.S.C. and A.M. (Alfredo Manuli); visualization, A.M.D.N., A.M. (Annalisa Militi), S.P. and S.C.; supervision, R.S.C. and A.Q.; project administration, R.S.C. and A.Q.; funding acquisition, A.Q. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Current Research Funds 2025, Ministry of Health, Italy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

As this systematic review involves secondary data analysis from previously published studies, no new ethical approval was required.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Aho, K.; Harmsen, P.; Hatano, S.; Marquardsen, J.; Smirnov, V.E.; Strasser, T. Cerebrovascular disease in the community: Results of a WHO collaborative study. Bull. World Health Organ. 1980, 58, 113–130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bernoud-Hubac, N.; Lo Van, A.; Lazar, A.N.; Lagarde, M. Ischemic Brain Injury: Involvement of Lipids in the Pathophysiology of Stroke and Therapeutic Strategies. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.O.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P.; FGrupper, M.; Rautalin, I. World Stroke Organization: Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2025. Int. J. Stroke 2025, 20, 132–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigin, V.L.; Brainin, M.; Norrving, B.; Martins, S.; Sacco, R.L.; Hacke, W.; Fisher, M.; Pandian, J.; Lindsay, P. World Stroke Organization (WSO): Global Stroke Fact Sheet 2022. Int. J. Stroke 2022, 17, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwakkel, G.; Stinear, C.; Essers, B.; Munoz-Novoa, M.; Branscheidt, M.; Cabanas-Valdés, R.; Lakičević, S.; Lampropoulou, S.; Luft, A.R.; Marque, P.; et al. Motor rehabilitation after stroke: European Stroke Organisation (ESO) consensus-based definition and guiding framework. Eur. Stroke J. 2023, 8, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; He, Y.; Wang, D.; Rezaei, M.J. Stroke rehabilitation: From diagnosis to therapy. Front. Neurol. 2024, 15, 1402729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Wang, Y.; Gou, H.; Xiao, H.; Chen, T. Strength Training of the Nonhemiplegic Side Promotes Motor Function Recovery in Patients With Stroke: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2023, 104, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S. Stroke Recovery Is a Journey: Prediction and Potentials of Motor Recovery after a Stroke from a Practical Perspective. Life 2023, 13, 2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verstraeten, S.; Mark, R.E.; Dieleman, J.; van Rijsbergen, M.; de Kort, P.; Sitskoorn, M.M. Motor Impairment Three Months Post Stroke Implies A Corresponding Cognitive Deficit. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2020, 29, 105119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gans, S.D.; Michaels, E.; Thaler, D.E.; Leung, L.Y. Detection of symptoms of late complications after stroke in young survivors with active surveillance versus usual care. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 4023–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]