Abstract

Background/Objectives: Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries frequently lead to long-term quadriceps impairments despite surgical repair. There is growing evidence that these deficits are caused in part by alterations in the central nervous system. Thus, transcranial neuromodulation (TNM) could be valuable in ACL rehabilitation. To systematically review randomized controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the effects of TNM on neurophysiological, functional, and safety outcomes in patients with ACL injury or reconstruction. Methods: We conducted searches on PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane. We considered all original studies evaluating TNM, including transcranial current stimulation (tCS) and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), in patients with ACL reconstruction or injury. Measures of corticospinal excitability, safety, balance, and muscle strength were assessed. We employed the Cochrane RoB 2 method to assess the risk of bias. Results: Seven studies comprising 129 participants (64 TNM, 65 controls) were included. Most studies applied transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) over the primary motor cortex contralateral to the ACL injury in conjunction with physical rehabilitation. Single-session protocols demonstrated minimal effects, whereas repeated sessions resulted in improvements in corticospinal excitability, quadriceps strength, and balance. No serious adverse events were reported; minor effects included transient headache or scalp tingling. The risk of bias was assessed as low to moderate across the studies. Conclusions: TNM appears to be safe and may enhance functional recovery in individuals with ACL injuries when administered in multiple sessions alongside standard rehabilitation. Further high-quality trials are necessary to determine optimal protocols and long-term outcomes.

1. Introduction

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are among the most frequent sports-related knee injuries [1,2], with an incidence of 7 cases per 10,000 people each year [3]. These injuries predominantly affect young and active individuals aged 20–35 years, with 65–75% of tears occurring during athletic activities such as soccer, handball, basketball, and skiing [4,5,6]. Nonetheless, 25–35% of ACL injuries also arise in non-athletic contexts [7]. Males constitute 58–73% of ACL injuries [8,9], although females are 4–8 times more likely to experience an ACL tear when exposure is considered [10,11]. An estimated 70% of affected athletes face a decline in their performance after an ACL tear [1]. ACL reconstruction (ACLR) is the main treatment option for ACL tears, with more than 75% of ACL tears undergoing surgery [6]. However, dynamic and functional instability may persist even after surgical reconstruction [1]. Some patients have unfavorable outcomes after ACLR [4]. Approximately 65% of athletes return to their pre-injury performance level, with even fewer (≈55%) resuming competitive-level activity [12,13]. Quadriceps muscle dysfunction is common and may persist for a prolonged time after ACLR, which can limit functional recovery [5,14].

From a biomechanical standpoint, leg muscles are crucial for stabilizing the knee post-injury. The hamstrings and hip abductors are particularly vital for reducing ACL strain and preventing re-injury, whereas excessive activation of the quadriceps and gastrocnemius may increase anterior tibial translation and ACL stress [15,16]. There is increasing evidence that ACL tears lead to significant alterations in the central nervous system (CNS) [14]. Corticospinal tract (CST) excitability is reduced following ACL tears, limiting motor control and lower extremity function [17]. Post-ACL injury, cortical reorganization occurs within the primary motor cortex, particularly in corticomotor pathways associated with the quadriceps [18,19,20]. These neuroplastic changes, which include altered intracortical and corticospinal excitabilities, contribute to impaired voluntary muscle activation and motor output [21,22]. CNS excitability alterations may contribute to quadriceps dysfunction following ACLR [23].

Traditionally, rehabilitation has concentrated on peripheral recovery; however, conventional physiotherapy methods—such as electrostimulation or isolated strengthening—demonstrate limited effectiveness in addressing central neurophysiological deficits [22]. Recent evidence underscores the significance of integrating neuromodulatory interventions that target both muscular and cortical levels to enhance recovery [24,25,26]. In certain patients, traditional rehabilitation approaches fail to restore quadriceps function fully [27], potentially due to a lack of restoration of normal CST neurophysiology. Therefore, there is growing interest in using interventions that modulate CST excitability in the rehabilitation after ACL injuries [1]. Transcranial neuromodulation (TNM) offers non-invasive and safe means to modulate CST excitability, for example, using transcranial current stimulation (tCS) or transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) [28,29]. TNM targeting the primary motor cortex (M1) can increase CST excitability and has been shown to improve functional recovery in targeted muscles [30,31].

A recent meta-analysis of 44 RCTs with 1555 post-stroke patients demonstrated that transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) improved upper extremity motor function (standardized mean difference = 0.22, 95% confidence interval: 0.12–0.32, p < 0.001) [32]. Krogh et al. [33] reported that 4 weeks of repetitive TMS combined with resistance training significantly improved Lower Extremity Motor Score (LEMS) in individuals with spinal cord injury compared to sham control. Given that motor cortex excitability may be reduced in ACLR patients, TNM may theoretically improve recovery by increasing CST activation during exercise [4,14]. However, while TNM has been shown to improve clinical outcomes in various neurological and musculoskeletal disorders [33,34,35,36], its efficacy in ACL injuries remains unclear. We aim to assess the existing evidence on the impact of TNM on ACL injuries. Our research question is articulated using the PICO framework as follows: In patients with anterior cruciate ligament injury or reconstruction (P), does transcranial neuromodulation (I), in comparison to usual care or sham stimulation (C), enhance neurophysiological, functional, and safety outcomes (O)? This inquiry directs the systematic evaluation of existing randomized controlled trials in this domain.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

We conducted this review in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [37] guidelines and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [38]. The systematic review process, including independent screening, data extraction, quality assessment, and synthesis, was conducted from 25 June to 25 July 2025, adhering to standard systematic review timelines for methodological rigor, and the protocol was registered in PROSPERO on 1 July 2025 under the ID: CRD420251080478.

2.2. Data Sources and Search Strategy

Four databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane) were searched from inception until April 2025, using the following keywords: “Transcranial Neuromodulation”, “Transcranial Electrical Stimulation”, “Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation”, and “Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction”. The detailed search strategy is illustrated in File S1. The systematic review process, including independent screening, data extraction, quality assessment, and synthesis, was conducted from June to July 2025, adhering to standard systematic review timelines for methodological rigor.

2.3. Inclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria were established using the PICO framework. We included any original study that assessed TNM on patients with ACL injury or after ACLR. Patients diagnosed with ACL injury or after ACLR comprised the population (P). Intervention (I): TNM regardless of modality (e.g., electrical, magnetic, ultrasound, or light-based) or stimulation frequency, while comparison (C) involved control groups receiving usual care or sham stimulation. Primary outcomes (O) of interest included neurophysiological, functional, and safety endpoints. We excluded studies that used peripheral stimulation, single-arm non-controlled studies, reviews, editorials, and animal studies. No restrictions were applied regarding language or publication year.

2.4. Study Selection

We imported the identified records into EndNote 2025 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) to remove duplicates. Two independent authors screened the title and abstract, followed by full-text screening of the relevant studies using the Rayyan website [39]. Moreover, we performed forward and backward citation analyses for the included studies. Any conflict between the authors was addressed through consensus.

2.5. Data Extraction

Two independent authors extracted the data using a predefined Excel sheet. The extracted data was the study summary, including study ID, study design, country, sample size for each group, ACL condition, type of TNM used, type of comparator, target brain region, concurrent treatments, follow-up duration, endpoints in each study, and conclusion. Baseline characteristics included: age, male sex, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI). Additionally, we completed a risk of bias assessment.

2.6. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

We employed the ROB2 tool to evaluate the risk of bias [40]. This instrument assessed the randomized clinical trials across five domains: the randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement bias, and reporting bias. The methodological quality of the included studies was independently evaluated by two reviewers (M.B.-A. and F.F.-V.). In instances of disagreement, a third and fourth reviewer (A.P.-L. and N.P.-L.) were consulted, and the final decision was reached through consensus among all reviewers.

2.7. Evidence Synthesis

Because of the variability in intervention regimen, outcome measures, and follow-up lengths, we used a descriptive evidence synthesis. No meta-analysis was performed. Conducting a quantitative synthesis through meta-analysis was not possible because of significant differences among the studies, including variations in species, pain models, types of seaweed, chemicals examined, study designs, and methods of measuring outcomes. Consequently, we opted for a narrative synthesis of the evidence to address this gap. This methodological decision aligns with the Cochrane guidelines, which recommend narrative synthesis when heterogeneity exceeds the appropriate statistical thresholds. We compared the main findings across different models and study contexts, organizing the studies by compound class and the seaweed species. Where applicable, we explored the potential mechanisms of action and examined the patterns of consistency or variability of the included studies. Furthermore, we analyzed stimulation parameter-outcome relationships to identify potentially optimal protocols, recognizing the clinical relevance of protocol optimization for future applications.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and Study Selection

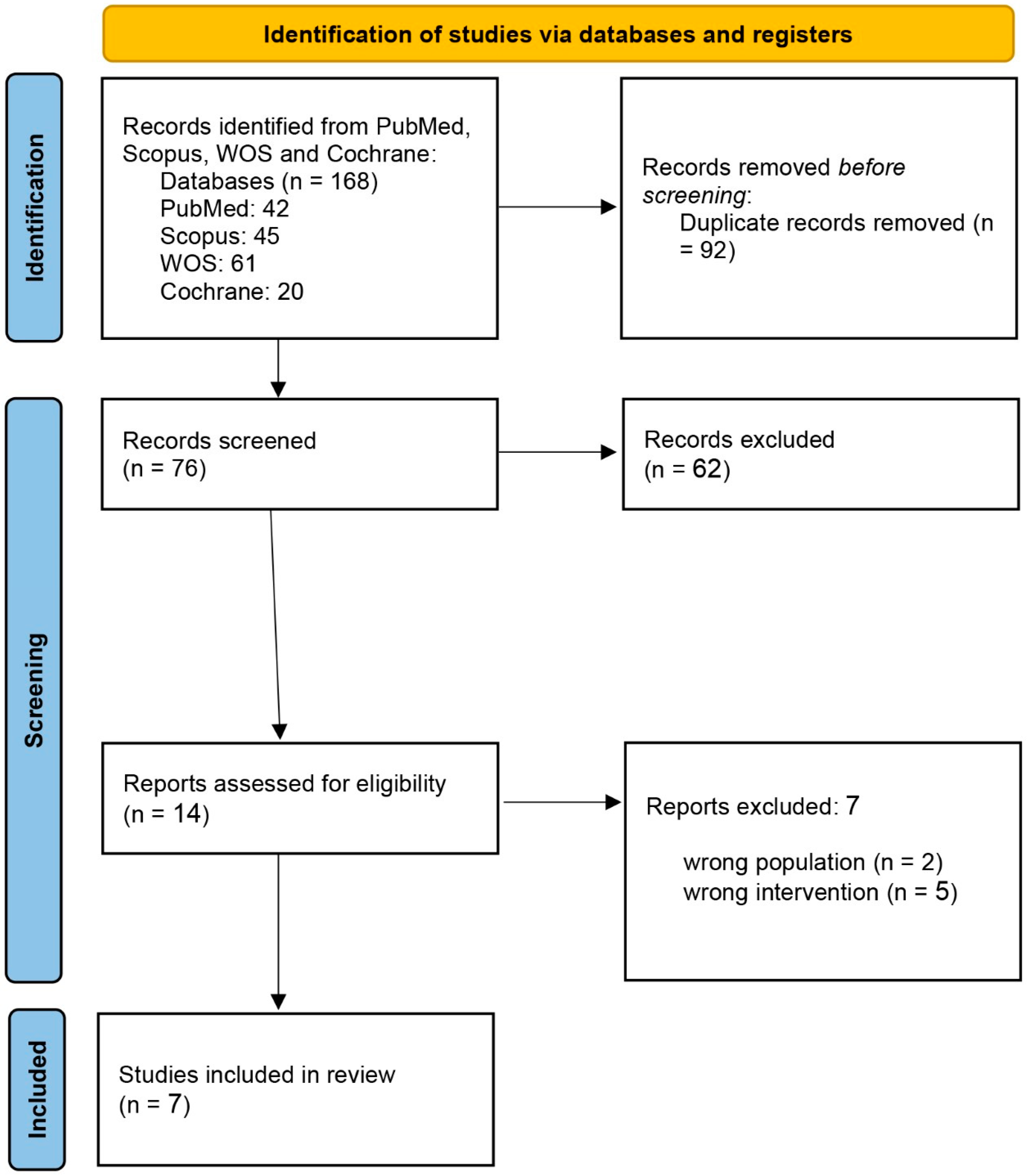

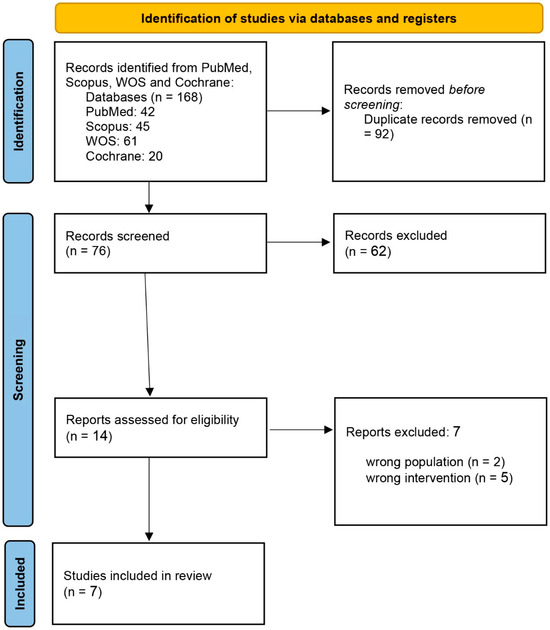

At the initial systematic search, 168 eligible studies were determined. Of these, 92 articles were duplicated, and another 62 were not qualified based on the information presented in the abstract. Finally, the full texts of 14 studies were reviewed, and 7 were included in the systematic review. The PRISMA flow chart of the selection process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the screening process.

3.2. Study Characteristics

Seven randomized controlled trials, including two cross-over trials [4,27], assessed TNM interventions in individuals with ACL injury or ACL reconstruction. Across all studies, there were a total of 129 participants with parallel-group and crossover designs (sample sizes per study ranged from 6 to 34 individuals).

The participants were predominantly young adults, with a mean age ranging from 20.6 to 34.8 years. Some studies, such as Reuter et al. [1], reported BMI values of 27.1 (SD = 3.6) in TNM and 25.9 (SD = 1.9) in controls. Several studies, such as Jamebozorgi et al. [23], enrolled only male participants. TNM modalities primarily targeted the primary motor cortex (M1), with six studies using tDCS with the anode over the motor cortex (M1) contralateral to the ACL injury (a-tDCS). In these tDCS studies, stimulation levels of 1 to 2.2 mA were applied for 20 min, with protocols varying from single sessions to ten sessions within a six-week timeframe. One study (Jamebozorgi et al., 2023) [23] used tDCS with the anode over Oz (occipital cortex) and the cathode over the right shoulder. Jamebozorgi et al. (2023) [23] aimed to enhance visual-proprioceptive integration to improve balance and proprioception outcomes. Flanagan et al. (2021) [41] utilized intermittent theta burst stimulation (iTBS) with M1 as the target. Follow-up assessments ranged from immediate post-intervention to six weeks. All studies except one (Flanagan et al., 2021) [41] used concurrent treatment as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of the included RCTs.

Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 provide the summary and main findings, and baseline characteristics of the included studies, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of Main Findings from Recent Studies on tDCS and Neuromuscular Function Following ACL Reconstruction.

Table 3.

Baseline characteristics of the participants.

Stimulation Parameters and Clinical Outcomes Analysis

Seven RCTs employed variable stimulation parameters: anodal tDCS intensity ranged from 1 to 2.2 mA, duration was consistently 20 min, and session frequency varied from single sessions to 10 sessions over 4–6 weeks. Six studies targeted the primary motor cortex (M1) contralateral to the ACL injury, while one study (Jamebozorgi et al., 2023) [23] used occipital cortex targeting for visual-proprioceptive integration.

Protocol Effectiveness Patterns: 1-Multi-session protocols (≥3 sessions) demonstrated superior clinical outcomes compared to single sessions; 2-M1 targeting showed consistent improvements in corticospinal excitability and muscle function; 3-Occipital targeting enhanced proprioception and balance measures specifically; 4-Session frequency rather than intensity appeared to be the primary determinant of clinical efficacy.

These findings suggest that protocol design (session number and cortical targeting) may be more critical than stimulation intensity for optimal clinical outcomes in ACL rehabilitation.

3.3. Patient Population

The participants in the studies had different stages of ACL pathology, including acute ACL rupture (Murphy et al., 2024 [6]; Reuter et al., 2024 [1]; Tohidirad et al., 2023 [2]), subacute injuries (Tohidirad et al., 2023 [2]), and post-operative ACL reconstruction (Zarzycki et al., 2025 [27]; Rush et al., 2020 [4]). Participants were generally enrolled if they had an ACL injury or underwent ACL reconstruction with adequate knee range of motion, minimal knee effusion, and no active infection. There were consistent exclusion criteria regarding previous knee surgery (aside from the ACL reconstruction), multi-ligament injuries, neuromuscular disorders, and contraindications to TNM (e.g., metal implants, history of seizures) [1,2,4,6,27].

3.4. Outcomes

The findings are presented descriptively, given the clinical and methodological heterogeneity across studies, which precludes meaningful statistical pooling. This approach allows for a transparent representation of diverse intervention protocols while maintaining methodological rigor appropriate for this emerging research area.

A broad range of outcomes was assessed across the studies, which can be categorized into three main domains.

Neurophysiological outcomes: Corticospinal excitability and motor cortex function showed variable responses in different studies. Two studies (Zarzycki et al., 2025 [27]; Rush et al., 2020 [4]) reported non-significant changes in active motor thresholds and muscle function following single-session TMS protocols. In contrast, Murphy et al. [6] demonstrated significant improvements in quadriceps intracortical inhibition and facilitation using multi-session tDCS protocols. Table 2 provides the detailed statistical findings for each study.

Functional performance and balance outcomes: Related to postural control, proprioception, and muscle function. Mixed findings were observed for balance and proprioception measurements across studies. Reuter et al. [1] observed non-significant reductions in medial-lateral and anterior–posterior center of pressure (CoP) displacements post-TNM, with no p-values reported. The CoP velocity also slightly declined in both groups. In contrast, Tohidirad et al. [2] reported significant improvements in several postural control metrics: CoP displacement in the y-axis for both legs increased by 26.68 mm (SD 10.43; p = 0.018), and APF at 60 ms rose by 9.23 N (SD 2.20; p = 0.001). Proprioception and dynamic balance were assessed using the joint position error and the Star Excursion Balance Test (SEBT), respectively. Jamebozorgi et al. [23] reported greater anterior SEBT improvements in the TNM group (12.4 cm, SD 0.23) than controls (1.5 cm, SD 0.83), but without statistical significance (p = 0.3). Knee joint position sense errors showed no significant between-group differences at 30°, 45°, or 90° (all p > 0.05). Table 2 provides detailed findings for each of the studies.

Rush et al. [4] evaluated muscle function and EMG activity and found non-significant changes in EMG (% change in vastus medialis: −12.1% vs. −18.9%, p = 0.31; vastus lateralis: −14.8% vs. −25.9%, p = 0.25), isometric strength (−8.9% vs. −10.1%, p = 0.75), and voluntary activation (−5.03% vs. −5.5%, p = 0.79). Patient-reported outcomes, including the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) subscales, showed modest improvements that were not statistically significant. For instance, KOOS pain improved by 2.8 points in the TNM group versus 0.6 points in the control group (p = 0.47), and KOOS symptoms improved by 4.7 versus 3.1 points (p = 0.09).

Safety outcomes: Adverse events were consistently minor and well tolerated across all studies. Minor symptoms, such as headache, sleepiness, and scalp tingling, were infrequent and resolved without intervention, with no serious adverse events reported. These safety findings are consistent with the established safety profiles of transcranial neuromodulation techniques in clinical populations. Table 2 provides detailed safety data for each of the studies.

Note on evidence visualization: Visual summaries, such as forest plots or direction-of-effect matrices, are most informative when sufficient homogeneous studies are available for statistical pooling. Given the clinical and methodological heterogeneity identified across our included studies (see Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3), such visualizations would not meaningfully contribute to the evidence synthesis and could potentially mislead readers about the certainty of available evidence.

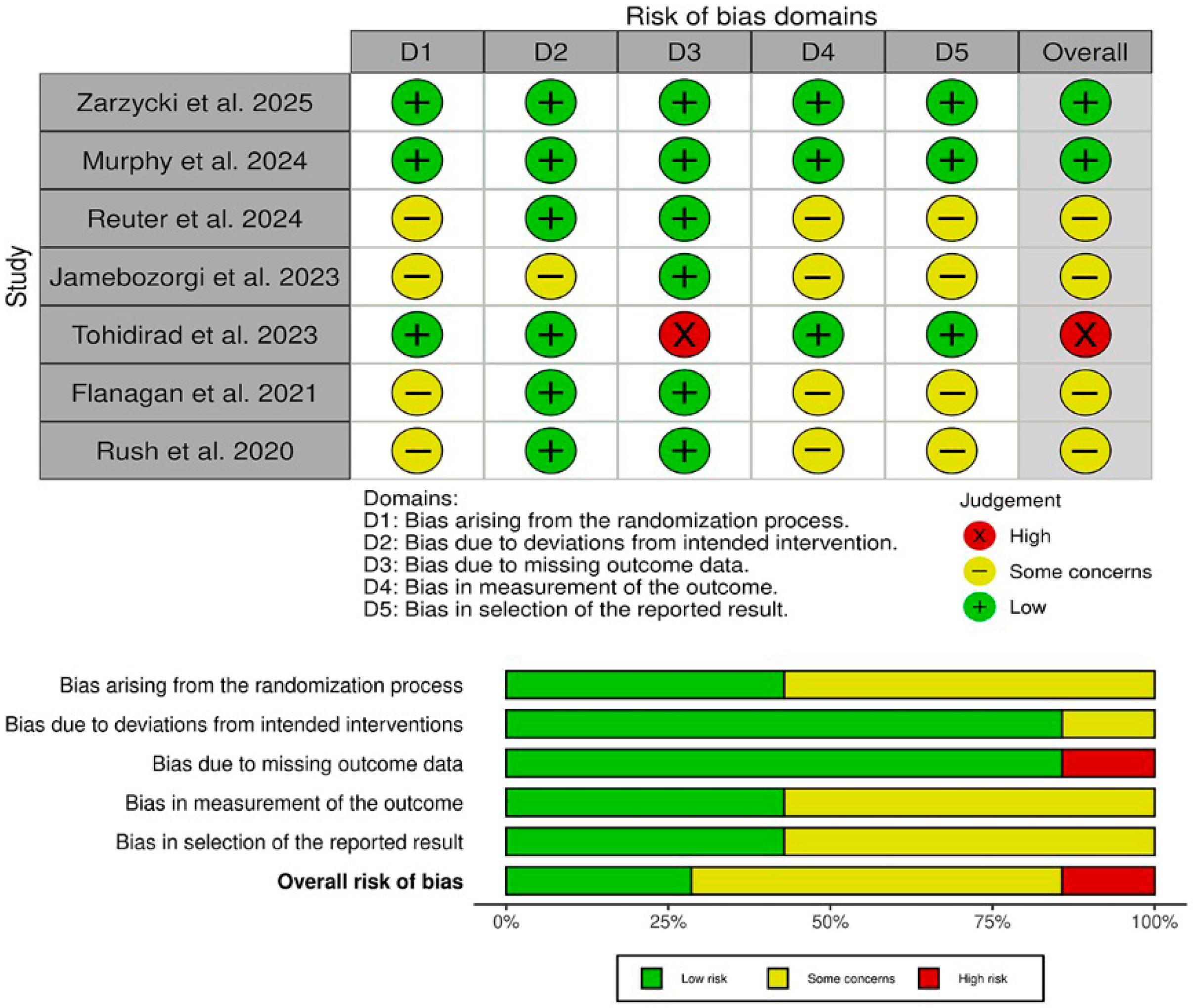

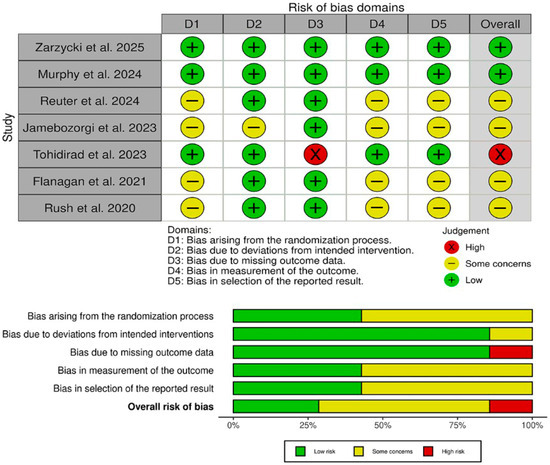

3.5. Risk of Bias

The risk of bias assessment using the Cochrane RoB 2 tool (Figure 2) revealed that two studies (Zarzycki et al. [27] and Murphy et al. [6]) achieved an overall low risk of bias, with all five domains (randomization, deviations from intended intervention, missing data, outcome measurement, and selective reporting) judged as low risk. One trial (Tohidirad et al. [2]) was rated high overall due to inadequate handling of missing outcome data (D3), despite low risk in other domains. The remaining four studies (Reuter et al. [1], Jamebozorgi et al. [23], Flanagan et al. [41], and Rush et al. [4]) each had “some concerns” overall, most often reflecting unclear allocation procedures (D1), incomplete blinding of outcome assessors (D4), or potential selective reporting (D5). These findings underscore that, while the two well-controlled RCTs provide the most reliable evidence, results from smaller pilot and quasi-experimental studies should be interpreted with caution.

Figure 2.

Quality assessment of risk of bias in the included trials. The upper panel presents a schematic representation of risks (low = green, unclear = yellow, and high = red) for specific types of biases of each of the studies in the review. The lower panel presents risks (low = green, unclear = yellow, and high = red) for the subtypes of biases of the combination of studies included in this review [1,2,4,6,23,41].

4. Discussion

This systematic review evaluates synthesized evidence from seven controlled trials examining TNM in ACL-injured populations. Our findings suggest TNM, especially paired with rehabilitation, might offer promise for enhancing functional outcomes. All, but one of the studies included in the review were conducted with tDCS, and in most cases the anode was placed over M1 contralateral to the injured ACL. Although single session tDCS protocols did not elicit changes in CST excitability or muscle contraction (i.e., strength), reductions in quadriceps inhibition [6,27] and improvements in dynamic stability [2] were observed after several sessions. This finding is consistent with the literature on noninvasive brain stimulation in other rehabilitation applications, which emphasizes the value of combination with physical, occupational, or speech therapy interventions, and highlights the need for multiple intervention sessions to achieve meaningful clinical outcomes. The single study with iTBS [41], points to the possibility of longer-lasting changes to brain organization and function, but the focus on injury phases suggests more work is needed to determine optimal timings and sequences for intervention with neuromodulation.

Cross-study comparisons are difficult owing to different co-interventions and protocols. Nonetheless, the findings support the value of integrating noninvasive brain stimulation techniques [42], particularly tDCS, into rehabilitation programs to improve motor recovery after ACL reconstruction surgery [30]. However, larger, well-controlled studies are needed, and the mechanisms of action remain unclear. For instance, Murphy et al. (2024) [6] found that multi-session tDCS with the anode applied to M1 during rehabilitation promotes suppression of quadriceps motor cortex intracortical inhibition and enhancement of intracortical facilitation. This alleviates the effects of AMI, which is a very common ACL injury complication and has a detrimental effect on neuromuscular function [4]. However, Jamebozorgi et al. [23] who combined tDCS with biofeedback found improved proprioception leading to the improved balance in athletes with ACL deficiency [23]. It is likely that TNM in ACL rehabilitation may have therapeutic effects related to different neurophysiological pathways. TNM may modulate and normalize CST excitability, reduce AMI, restore the balance of interhemispheric inhibition. improve dynamic balance by modulating hyperactive reflex arcs at the spinal level and strengthen sensorimotor integration and support the Hebbian plasticity hypothesis [43]. In any case, TNM combined with physical and other therapies can yield functional gains beyond those achieved with sham stimulation, suggesting that TNM can prime the motor system towards recovery [44].

The neurobiological mechanisms underlying the effects of TNM may involve the modulation of cortical excitability and synaptic plasticity [45]. Specifically, principles of Hebbian plasticity suggest that the repeated co-activation of cortical and muscular pathways can strengthen neural connections, thereby enhancing motor recovery [46]. Modulation of short-interval intracortical inhibition and intracortical facilitation (SICI/ICF) may alleviate AMI by reducing excessive cortical inhibition while promoting excitatory pathways [47]. Improvements in sensorimotor integration and proprioception may result from enhanced communication between sensory and motor cortical regions, thereby supporting coordinated movement and balance [48]. Furthermore, evidence from related interventions underscores the extensive neurophysiological and psychological potential of TNM and complementary practices. For instance, a study employing a single session of tDCS in conjunction with mirror therapy demonstrated a direct enhancement in the function of the dominant hand and an indirect improvement in the non-dominant hand [49]. This indicates that even acute neuromodulatory interventions can augment cortical plasticity and motor function. Additionally, mind–body interventions, such as a 3-month yoga and meditation retreat, have been associated with improvements in psychological well-being, increased BDNF and cortisol awakening response, and modulation of inflammatory markers [50]. These findings suggest that interventions targeting neuroplasticity and physiological regulation can facilitate mind–body integration, potentially complementing TNM in rehabilitation by supporting overall neural and systemic health.

Finding the ideal timing concerning injury or surgical intervention, identifying patient subgroups who respond well, and improving stimulation parameters (such as intensity, duration, and electrode montage) are critical areas. The integration of TNM with rehabilitation warrants further exploration to disentangle synergistic effects from confounding co-interventions. Multimodal assessments, along with neurophysiological (e.g., TMS, EEG), biomechanical, and patient-reported outcomes, are needed to clarify underlying mechanisms and functional relevance. Additionally, emerging technology that includes closed-loop NIBS and individualized dosing based on baseline cortical excitability might also enhance treatment precision and efficacy. Longitudinal studies comparing retention of benefits, re-damage risk, and return-to-sport metrics will be important for translating these neuromodulatory techniques into clinical exercise. NIBS techniques delivered over several sessions may enhance neuromuscular recovery following ACL injuries or reconstructive surgeries.

4.1. Limitations

In summary, this systematic review provides the first comprehensive synthesis of randomized controlled trial data on TNM for ACL rehabilitation. Overall, the available studies highlight the potential of TNM, particularly tDCS when paired with physical therapy, to promote ACL injury recovery and improve balance. However, the studies published to date are hindered by their small sample sizes, differing methodologies, and lack of follow-up, which prevents drawing firm conclusions and underscores the necessity for further evidence. Most available studies as single center with varying blinding and control settings, and a higher risk of bias. Furthermore, while the diversity of methods limits the comparability across studies, the complete absence of quantitative analysis diminishes the review’s evidential strength. Although a simple meta-analysis (e.g., standardized mean difference for muscle strength or balance) employing a random-effects model could have been considered, the heterogeneity of protocols and outcomes led us to provide a rationale for the absence of a meta-analysis.

Study quality considerations significantly impacted the evidence in our review. Two studies demonstrated a low risk of bias across all domains, providing high-certainty evidence, particularly for safety outcomes. However, most of the included studies (n = 4) showed “some concerns” primarily due to unclear allocation concealment and incomplete outcome assessor blinding, while one study was rated as having a high risk due to inadequate handling of missing data. The small sample sizes across most studies (6–34 participants) limit generalizability and increase uncertainty around effect estimates. These quality concerns suggest that while the TNM appears promising for ACL rehabilitation, the findings should be interpreted with appropriate caution, particularly for subjective functional outcomes. Future high-quality, large-scale trials are essential before definitive clinical recommendations can be formulated.

4.2. Implications for Future Research

There is a need for multi-center, large-scale randomized controlled trials with more precise parameters. Ideally, future studies would incorporate large participant pools, rigorous randomization and blinding, set stimulation parameters such as site, intensity, and dosage, and measure clinically relevant outcomes like quadriceps strength, functional performance, comprehensive patient-reported outcomes, and long-term multicenter follow-up. Addressing these limitations would enhance the generalizability of the findings and allow determination of the value of TNM in standard rehabilitation protocols following ACL surgeries.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines13123068/s1, Table S1. Search strategy table based on each database. File S1: PRISMA 2020 checklist neuromodulation in acl rehabilitation.

Author Contributions

J.V.-M., A.P.-L. and J.M.T.-M. conceived the idea. J.V.-M. and M.B.-A. designed the research workflow. E.J.-C., L.B.-V. and J.F.-T. searched the databases. M.B.-A. and F.J.F.-V. screened the retrieved records, extracted relevant data, assessed the quality of evidence, and A.P.-L. and N.P.-L. resolved the conflicts. J.V.-M., Á.P.-L. and J.M.T.-M. wrote the final manuscript. M.B.-A., E.J.-C., L.B.-V., J.F.-T., Á.P.-L., N.P.-L. and F.J.F.-V. supervised and review final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Conselleria d’Innovació, Universitats, Ciència i Societat Digital Grants: The Catholic University of Valencia University and Coordinació del Sistema Valencià d’Investigació, Ciència i Desenvolupament Tecnològic Pilot Grant CIGE/2023/9 (GE).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Catholic University of Valencia San Vicente Mártir for their contributions and help in the payment of the Open Access publication free.

Conflicts of Interest

Alvaro Pascual-Leone serves as a paid member of the scientific advisory boards for Neuroelectrics, Magstim Inc., TetraNeuron, Skin2Neuron, MedRhythms, Bitbrain, and AscenZion. He is co-founder of TI solutions and co-founder and chief medical officer of Linus Health. He is partly supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Bearak Family, Jack Satter Foundation, and BrightFocus Foundation. Alvaro Pascual-Leone is listed as an inventor on several issued and pending patents on the real-time integration of transcranial magnetic stimulation with electroencephalography and magnetic resonance imaging, and applications of noninvasive brain stimulation in various neurological disorders; as well as digital biomarkers of cognition and digital assessments for early diagnosis of dementia. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Reuter, S.; Lambert, C.; Schadt, M.; Imhoff, A.B.; Centner, C.; Herbst, E.; Stöcker, F.; Forkel, P. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation and sensorimotor training in anterior cruciate ligament patients: A sham-controlled pilot study. Sportverletz. Sportschaden 2024, 38, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidirad, Z.; Ehsani, F.; Bagheri, R.; Jaberzadeh, S. Priming effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on the effects of conventional physiotherapy on balance and muscle performance in athletes with anterior cruciate ligament injury. J. Sport Rehabil. 2023, 32, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, T.L.; Maradit Kremers, H.; Bryan, A.J.; Larson, D.R.; Dahm, D.L.; Levy, B.A.; Krych, A.J. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament tears and reconstruction: A 21-year population-based study. Am. J. Sports Med. 2016, 44, 1502–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rush, J.L.; Lepley, L.K.; Davi, S.; Lepley, A.S. The immediate effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on quadriceps muscle function in individuals with a history of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A preliminary investigation. J. Sport Rehabil. 2020, 29, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepley, A.S.; Gribble, P.A.; Thomas, A.C.; Tevald, M.A.; Sohn, D.H.; Pietrosimone, B.G. Quadriceps neural alterations in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed patients: A 6-month longitudinal investigation. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2015, 25, 828–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.C.; Sylvester, C.; White, C.; D’Alessandro, P.; Rio, E.K.; Vallence, A.M. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) modulates quadriceps motor cortex inhibition and facilitation during rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction: A triple-blind, randomised controlled proof-of-concept trial. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2024, 10, e002080. [Google Scholar]

- Gianotti, S.M.; Marshall, S.W.; Hume, P.A.; Bunt, L. Incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury and other knee ligament injuries: A national population-based study. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2009, 12, 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kvist, J.; Kartus, J.; Karlsson, J.; Forssblad, M. Results from the Swedish National Anterior Cruciate Ligament Register. Arthroscopy 2014, 30, 803–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, L.A.; Foni, N.O.; Antonioli, E.; Teixeira de Carvalho, R.; Paião, I.D.; Lenza, M.; Ferretti, M. Analysis of 500 anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions from a private institutional register. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, D.; Myer, G.D.; Bush, H.M.; Klugman, M.F.; Medina McKeon, J.M.; Hewett, T.E. Compliance with neuromuscular training and anterior cruciate ligament injury risk reduction in female athletes: A meta-analysis. J. Athl. Train. 2012, 47, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flaxman, T.E.; Smith, A.J.J.; Benoit, D.L. Sex-related differences in neuromuscular control: Implications for injury mechanisms or healthy stabilization strategies? J. Orthop. Res. 2014, 32, 310–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frobell, R.B.; Lohmander, L.S.; Roos, H.P. Acute rotational trauma to the knee: Poor agreement between clinical assessment and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 2007, 17, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, R.; Holme, I. Risk factors for sports injuries—A methodological approach. Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 384–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki, R.; Morton, S.M.; Charalambous, C.C.; Pietrosimone, B.; Williams, G.N.; Snyder-Mackler, L. Examination of corticospinal and spinal reflexive excitability during the course of postoperative rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2020, 50, 516–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, S.M.; Guzman, A.; Gardner, B.B.; Bryant, S.A.; del Sol, S.R.; McGahan, P.; Chen, J. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament injury: Review of current literature and recommendations. Curr. Rev. Musculoskelet. Med. 2022, 15, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higbie, S.; Kleihege, J.; Duncan, B.; Lowe, W.R.; Bailey, L. Utilizing hip abduction strength-to-body weight ratios in return to sport decision-making after ACL reconstruction. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 1295–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepley, L.K.; Palmieri-Smith, R.M. Quadriceps strength, muscle activation failure, and patient-reported function at the time of return to activity in patients following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A cross-sectional study. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 45, 1017–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, T.; Sayer, T.; Theisen, D.; Mierau, A. Functional brain plasticity associated with ACL injury: A scoping review of current evidence. Neural Plast. 2019, 2019, 3480512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, D.A.; Rush, J.; Glaviano, N.R.; Norte, G.E. Knee joint pathology and efferent pathway dysfunction: Mapping muscle inhibition from motor cortex to muscle force. Musculoskelet. Sci. Pract. 2024, 74, 103204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheurer, S.A.; Sherman, D.A.; Glaviano, N.R.; Ingersoll, C.D.; Norte, G.E. Corticomotor function is associated with quadriceps rate of torque development in individuals with ACL surgery. Exp. Brain Res. 2020, 238, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hortobágyi, T.; Richardson, S.P.; Lomarev, M.; Shamim, E.; Meunier, S.; Russman, H.; Dang, N.; Hallett, M. Chronic low-frequency rTMS of primary motor cortex diminishes exercise training-induced gains in maximal voluntary force in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 2009, 106, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muellbacher, W.; Ziemann, U.; Wissel, J.; Dang, N.; Kofler, M.; Facchini, S.; Boroojerdi, B.; Poewe, W.; Hallett, M. Early consolidation in human primary motor cortex. Nature 2002, 415, 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamebozorgi, A.; Rahimi, A.; Daryabor, A.; Kazemi, S.M.; Jamebozorgi, F. The effects of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) and biofeedback on proprioception and functional balance in athletes with ACL-deficiency. Middle East J. Rehabil. Health Stud. 2023, 10, e130364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, T.; Dong, X.N. The use of hamstring fatigue to reduce quadriceps inhibition after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Percept. Mot. Skills 2018, 125, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, J.M.; Kuenze, C.M.; Diduch, D.R.; Ingersoll, C.D. Quadriceps muscle function after rehabilitation with cryotherapy in patients with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. J. Athl. Train. 2014, 49, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonnery-Cottet, B.; Saithna, A.; Quelard, B.; Daggett, M.; Borade, A.; Ouanezar, H.; Thaunat, M.; Blakeney, W.G. Arthrogenic muscle inhibition after ACL reconstruction: A scoping review of the efficacy of interventions. Br. J. Sports Med. 2019, 53, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarzycki, R.; Leung, A.; Abraham, R.; Hammoud, S.; Perrone, M.; Kantak, S. Determining the safety, feasibility, and effects of anodal transcranial direct current stimulation on corticospinal excitability and quadriceps performance after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A randomized crossover design. Ann. Jt. 2025, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayaka, T.; Zoghi, M.; Farrell, M.; Egan, G.F.; Jaberzadeh, S. Does transcranial electrical stimulation enhance corticospinal excitability of the motor cortex in healthy individuals? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017, 46, 1968–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jannati, A.; Oberman, L.M.; Rotenberg, A.; Pascual-Leone, A. Assessing the mechanisms of brain plasticity by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuropsychopharmacology 2023, 48, 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefaucheur, J.-P.; André-Obadia, N.; Antal, A.; Ayache, S.S.; Baeken, C.; Benninger, D.H.; Cantello, R.M.; Cincotta, M.; de Carvalho, M.; De Ridder, D.; et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Clin. Neurophysiol. 2014, 125, 2150–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talelli, P.; Wallace, A.; Dileone, M.; Hoad, D.; Cheeran, B.; Oliver, R.; Rothwell, J.C. Theta burst stimulation in the rehabilitation of the upper limb: A semirandomized, placebo-controlled trial in chronic stroke patients. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair. 2012, 26, 976–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, X.; Zhang, N.; Shen, Z.; Guo, X.; Xing, J.; Tian, S.; Xing, Y. Transcranial direct current stimulation for upper extremity motor dysfunction in poststroke patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2024, 38, 749–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, S.; Aagaard, P.; Jønsson, A.B.; Figlewski, K.; Kasch, H. Effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on recovery in lower limb muscle strength and gait function following spinal cord injury: A randomized controlled trial. Spinal Cord 2022, 60, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Lu, T.; Yu, H.; Shen, J.; Chen, Z.; Yang, X.; Huang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, X.; et al. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for neuropathic pain and neuropsychiatric symptoms in traumatic brain injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neural Plast. 2022, 2022, 2036736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrey, S. A new way to treat central nervous system dysfunction caused by musculoskeletal injuries using transcranial direct current stimulation: A narrative review. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, W.; Idnani, S.; Kim, J. Transcranial direct current stimulation for orthopedic pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Brain Sci. 2024, 14, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.; Chandler, J.; Welch, V.; Higgins, J.P.; Thomas, J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: A new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2019, 10, ED000142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flemyng, E.; Moore, T.H.; Boutron, I.; Higgins, J.P.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Nejstgaard, C.H.; Dwan, K. Using Risk of Bias 2 to assess results from randomised controlled trials: Guidance from Cochrane. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2023, 28, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, S.D.; Proessl, F.; Dunn-Lewis, C.; Sterczala, A.J.; Connaboy, C.; Canino, M.C.; Beethe, A.Z.; Eagle, S.R.; Szivak, T.K.; Onate, J.A.; et al. Differences in brain structure and theta burst stimulation-induced plasticity implicate the corticomotor system in loss of function after musculoskeletal injury. J. Neurophysiol. 2021, 125, 1006–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zech, A.; Hübscher, M.; Vogt, L.; Banzer, W.; Hänsel, F.; Pfeifer, K. Neuromuscular training for rehabilitation of sports injuries: A systematic review. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1831–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittal, N.; Majdic, B.C.; Peterson, C.L. Intermittent Theta Burst Stimulation Modulates Biceps Brachii Corticomotor Excitability in Individuals with Tetraplegia. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2022, 19, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Jung, J.; Lee, S. Synergistic effects of joint-biased rehabilitation and combined transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) in chronic ankle instability: A single-blind, three-armed randomized controlled trial. Brain Sci. 2025, 15, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modulation of Cortical Excitability Induced by Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation: Influence of Timing and Geometrical Parameters and Underlying Mechanisms. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21056619/ (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Revill, K.P.; Haut, M.W.; Belagaje, S.R.; Nahab, F.; Drake, D.; Buetefisch, C.M. Hebbian-type primary motor cortex stimulation: A potential treatment of impaired hand function in chronic stroke patients. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2020, 34, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, S.K.; McNeil, C.J.; Butler, J.E.; Gandevia, S.C.; Taylor, J.L. Short-interval cortical inhibition and intracortical facilitation during submaximal voluntary contractions change with fatigue. Exp. Brain Res. 2016, 234, 2541–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.G.; Yun, S.J.; Farrens, A.J.; Johnson, C.A.; Reinkensmeyer, D.J. A systematic review of the learning dynamics of proprioception training: Specificity, acquisition, retention, and transfer. Neurorehabil. Neural Repair 2023, 37, 744–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wójcik, M.; Vlček, P.; Siatkowski, I.; Grünerová-Lippertová, M. Effects of a single tDCS with mirror therapy stimulation on hand function in healthy individuals. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2025, 19, 1607022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahn, B.R.; Goodman, M.S.; Peterson, C.T.; Maturi, R.; Mills, P.J. Yoga, meditation and mind-body health: Increased BDNF, cortisol awakening response, and altered inflammatory marker expression after a 3-month yoga and meditation retreat. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).