Adipose-Specific Cytokines as Modulators of Reproductive Activity

Abstract

1. Introduction

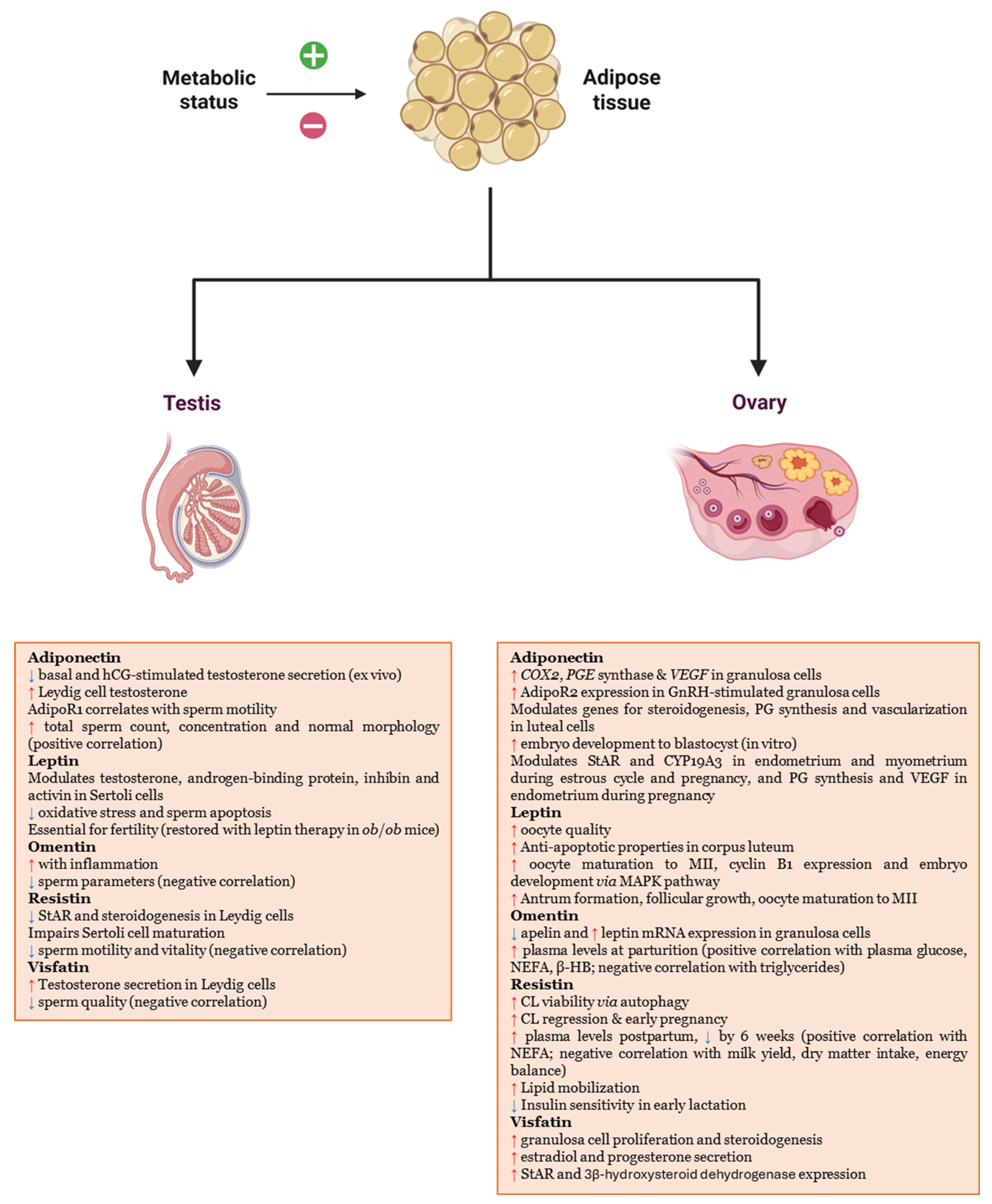

2. Adiponectin

2.1. Male

2.2. Female

3. Leptin

3.1. Male

3.2. Female

4. Omentin

4.1. Male

4.2. Female

5. Resistin

5.1. Male

5.2. Female

6. Visfatin

6.1. Male

6.2. Female

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AdipoR | Adiponectin receptor |

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| APN | Adiponectin |

| BAT | Brown adipose tissue |

| BTB | Blood-testicular barrier |

| CAP1 | Adenylate-cyclase-associated protein 1 |

| CL | Corpus luteum |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| ERK | Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| GH | Growth hormone |

| HMW | High-molecular-weight |

| IGF | Insulin-like growth factor |

| IL | Interleukin |

| IRS | Insulin Receptor Substrates |

| IRβ | Insulin Receptor β subunit |

| ITLN | Intelectin |

| JAK | Janus kinase |

| JNK | c-Jun N-terminal kinase |

| KISS | Kisspeptin |

| LEPR | Leptin Receptor |

| LMW | Low-molecular-weight |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| MMW | Medium-molecular-weight |

| NAMPT | Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer |

| PG | Prostaglandin |

| PKB | Protein Kinase B |

| PPAR | Peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor |

| StAR | Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory |

| STAT | Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

| TLR | Toll-like receptor |

| VEGF | Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor |

| WAT | White adipose tissue |

References

- Zwick, R.K.; Guerrero-Juarez, C.F.; Horsley, V.; Plikus, M.V. Anatomical, Physiological, and Functional Diversity of Adipose Tissue. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, H. Fine structure and lipid formation in fat cells of the perimeningeal tissue of lampreys under normal and experimental conditions. Z. Zellforsch. Mikrosk. Anat. 1968, 84, 585–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driskell, R.R.; Jahoda, C.A.B.; Chuong, C.-M.; Watt, F.M.; Horsley, V. Defining Dermal Adipose Tissue. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottaviani, E.; Malagoli, D.; Franceschi, C. The Evolution of the Adipose Tissue: A Neglected Enigma. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 174, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fève, B.; Cinti, S.; Beaupère, C.; Vatier, C.; Vigouroux, C.; Vali, A.; Capeau, J.; Grosfeld, A.; Moldes, M. Pink Adipose Tissue: A Paradigm of Adipose Tissue Plasticity. Ann. D’endocrinologie 2024, 85, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, L.A. Morphology and Relationships of the Orangutan Fatty Cheek Pads. Am. J. Primatol. 1989, 17, 305–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, C.J.; McLellan, W.A.; Rommel, S.A.; Gay, D.M.; Dillaman, R.M.; Pabst, D.A. Morphology of the Melon and Its Tendinous Connections to the Facial Muscles in Bottlenose Dolphins (Tursiops Truncatus). J. Morphol. 2008, 269, 820–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissengruber, G.E.; Egger, G.F.; Hutchinson, J.R.; Groenewald, H.B.; Elsässer, L.; Famini, D.; Forstenpointner, G. The Structure of the Cushions in the Feet of African Elephants (Loxodonta Africana). J. Anat. 2006, 209, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell-Rodwell, C.E. Keeping an “Ear” to the Ground: Seismic Communication in Elephants. Physiology 2007, 22, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoumi, M.; Faulconnier, Y.; Tabarani, A.; Sghiri, A.; Faye, B.; Chilliard, Y. Effects of Feeding Level on Body Weight, Hump Size, Lipid Content and Adipocyte Volume in the Dromedary Camel. Anim. Res. 2005, 54, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestris, E.; De Pergola, G.; Rosania, R.; Loverro, G. Obesity as Disruptor of the Female Fertility. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, M.; Oliveira, T.; Fernandes, R. State of the Art Paper Biochemistry of Adipose Tissue: An Endocrine Organ. Arch. Med. Sci. 2013, 9, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirichenko, T.V.; Markina, Y.V.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Varaeva, Y.R.; Starodubova, A.V. The Role of Adipokines in Inflammatory Mechanisms of Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yang, L.; Guo, Z.; Yao, N.; Zhang, S.; Pu, P. Obesity and Its Impact on Female Reproductive Health: Unraveling the Connections. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 14, 1326546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E.B. The Complex Role of Adipokines in Obesity, Inflammation, and Autoimmunity. Clin. Sci. 2021, 135, 731–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, K.; Stasiak, O.; Przybysz, P.; Grymowicz, M.; Smolarczyk, R. The Impact of the Endocrine and Immunological Function of Adipose Tissue on Reproduction in Women with Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahl, S.; Guenther, M.; Zhao, S.; James, R.; Marks, J.; Szabo, A.; Kidambi, S. Adiponectin Levels Differentiate Metabolically Healthy vs Unhealthy among Obese and Nonobese White Individuals. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 4172–4180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.M.D. Adiponectin: Role in Physiology and Pathophysiology. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2020, 11, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.M.; Doss, H.M.; Kim, K.S. Multifaceted Physiological Roles of Adiponectin in Inflammation and Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, Y.; Yamauchi, T.; Waki, H.; Tsuchida, A.; Hara, K.; Yago, H.; Miyazaki, O.; Ebinuma, H.; Kadowaki, T. Selective Purification and Characterization of Adiponectin Multimer Species from Human Plasma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 356, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, T.; Kamon, J.; Ito, Y.; Tsuchida, A.; Yokomizo, T.; Kita, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Miyagishi, M.; Hara, K.; Tsunoda, M.; et al. Cloning of Adiponectin Receptors That Mediate Antidiabetic Metabolic Effects. Nature 2003, 423, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hug, C.; Wang, J.; Ahmad, N.S.; Bogan, J.S.; Tsao, T.-S.; Lodish, H.F. T-Cadherin Is a Receptor for Hexameric and High-Molecular-Weight Forms of Acrp30/Adiponectin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 10308–10313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rak, A.; Mellouk, N.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Adiponectin and Resistin: Potential Metabolic Signals Affecting Hypothalamo-Pituitary Gonadal Axis in Females and Males of Different Species. Reproduction 2017, 153, R215–R226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, W.L.; Xia, J.Y.; Johnson, J.A.; Sun, K.; Pearson, M.J.; Sharma, A.X.; Quittner-Strom, E.; Tippetts, T.S.; Gordillo, R.; Scherer, P.E. Inducible Overexpression of Adiponectin Receptors Highlight the Roles of Adiponectin-Induced Ceramidase Signaling in Lipid and Glucose Homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 2017, 6, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.-P.; Lv, W.-S.; Yang, J.; Nie, A.-F.; Cheng, X.-B.; Yang, Y.; Ge, Y.; Li, X.-Y.; Ning, G. Globular Adiponectin Inhibits GnRH Secretion from GT1-7 Hypothalamic GnRH Neurons by Induction of Hyperpolarization of Membrane Potential. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 371, 756–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, J.-P.; Liu, C.; Bi, W.-K.; Hu, Y.-T.; Chen, Q.; Huang, H.; Liang, J.-X.; Li, L.-T.; Lin, L.-X.; Chen, G. Adiponectin Inhibits KISS1 Gene Transcription through AMPK and Specificity Protein-1 in the Hypothalamic GT1-7 Neurons. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 214, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiezun, M.; Smolinska, N.; Maleszka, A.; Dobrzyn, K.; Szeszko, K.; Kaminski, T. Adiponectin Expression in the Porcine Pituitary during the Estrous Cycle and Its Effect on LH and FSH Secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014, 307, E1038–E1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pacheco, F.; Martinez-Fuentes, A.J.; Tovar, S.; Pinilla, L.; Tena-Sempere, M.; Dieguez, C.; Castaño, J.P.; Malagon, M.M. Regulation of Pituitary Cell Function by Adiponectin. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 401–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, M.; Tang, Q.; Olefsky, J.M.; Mellon, P.L.; Webster, N.J.G. Adiponectin Activates Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase and Decreases Luteinizing Hormone Secretion in LβT2 Gonadotropes. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 760–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, M.; Brown, R.; Imran, S.A.; Ur, E. Adipokine Gene Expression in Brain and Pituitary Gland. Neuroendocrinology 2007, 86, 191–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Kuang, M.; Nie, H.; Bai, W.; Sun, L.; Wang, F.; Mao, D.; Wang, Z. Impact of Food Restriction on the Expression of the Adiponectin System and Genes in the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Ovarian Axis of Pre-Pubertal Ewes. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2016, 51, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Pérez, A.; Sánchez-Jiménez, F.; Maymó, J.; Dueñas, J.L.; Varone, C.; Sánchez-Margalet, V. Role of Leptin in Female Reproduction. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. (CCLM) 2015, 53, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quennell, J.H.; Mulligan, A.C.; Tups, A.; Liu, X.; Phipps, S.J.; Kemp, C.J.; Herbison, A.E.; Grattan, D.R.; Anderson, G.M. Leptin Indirectly Regulates Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neuronal Function. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 2805–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrine, J.C.P.; Franci, C.R.; Del Bianco-Borges, B. Leptin Actions through the Nitrergic System to Modulate the Hypothalamic Expression of the Kiss1 mRNA in the Female Rat. Brain Res. 2020, 1728, 146574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childs, G.V.; Odle, A.K.; MacNicol, M.C.; MacNicol, A.M. The Importance of Leptin to Reproduction. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqaa204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, N.; CarlLee, T.; Syed, M.M.; Odle, A.K.; Cozart, M.A.; Haney, A.C.; Allensworth-James, M.L.; Beneš, H.; Childs, G.V. Selective Deletion of Leptin Receptors in Gonadotropes Reveals Activin and GnRH-Binding Sites as Leptin Targets in Support of Fertility. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 4027–4042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odle, A.K.; Akhter, N.; Syed, M.M.; Allensworth-James, M.L.; Beneš, H.; Melgar Castillo, A.I.; MacNicol, M.C.; MacNicol, A.M.; Childs, G.V. Leptin Regulation of Gonadotrope Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Receptors as a Metabolic Checkpoint and Gateway to Reproductive Competence. Front. Endocrinol. 2018, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suter, K.J.; Pohl, C.R.; Wilson, M.E. Circulating Concentrations of Nocturnal Leptin, Growth Hormone, and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I Increase before the Onset of Puberty in Agonadal Male Monkeys: Potential Signals for the Initiation of Puberty1. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunetti, L.; Orlando, G.; Ferrante, C.; Recinella, L.; Leone, S.; Chiavaroli, A.; Di Nisio, C.; Shohreh, R.; Manippa, F.; Ricciuti, A. Orexigenic Effects of Omentin-1 Related to Decreased CART and CRH Gene Expression and Increased Norepinephrine Synthesis and Release in the Hypothalamus. Peptides 2013, 44, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, S.; Sengupta, P.; Jegasothy, R.; Akhigbe, R.E. Resistin and Visfatin: ‘Connecting Threads’ of Immunity, Energy Modulations and Male Reproduction. Chem. Biol. Lett. 2021, 8, 192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Fadeil, M.R.; Abd Allah, E.S.; Iraqy, H.M.; Elgamal, D.A.; Abdel-Ghani, M.A. Experimental Obesity and Diabetes Reduce Male Fertility: Potential Involvement of Hypothalamic Kiss-1, Pituitary Nitric Oxide, Serum Vaspin and Visfatin. Pathophysiology 2019, 26, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caminos, J.E.; Nogueiras, R.; Gaytán, F.; Pineda, R.; González, C.R.; Barreiro, M.L.; Castaño, J.P.; Malagón, M.M.; Pinilla, L.; Toppari, J.; et al. Novel Expression and Direct Effects of Adiponectin in the Rat Testis. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 3390–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, D.; Paré, A.; Jean, S.; Martin, L.J. Adiponectin Influences Progesterone Production from MA-10 Leydig Cells in a Dose-Dependent Manner. Endocrine 2015, 48, 957–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadivar, A.; Heidari Khoei, H.; Hassanpour, H.; Golestanfar, A.; Ghanaei, H. Correlation of Adiponectin mRNA Abundance and Its Receptors with Quantitative Parameters of Sperm Motility in Rams. Int. J. Fertil. Steril. 2016, 10, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Kratzsch, D.; Schaab, M.; Scholz, M.; Grunewald, S.; Thiery, J.; Paasch, U.; Kratzsch, J. Seminal Plasma Adipokine Levels Are Correlated with Functional Characteristics of Spermatozoa. Fertil. Steril. 2013, 99, 1256–1263.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Barbitta, M.; Maranesi, M.; Mercati, F.; Marini, D.; Anipchenko, P.; Grispoldi, L.; Cenci-Goga, B.T.; Zerani, M.; Dall’Aglio, C. Presence, Tissue Localization, and Gene Expression of the Adiponectin Receptor 1 in Testis and Accessory Glands of Male Rams during the Non-Breeding Season. Animals 2023, 13, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jope, T.; Lammert, A.; Kratzsch, J.; Paasch, U.; Glander, H.-J. Leptin and Leptin Receptor in Human Seminal Plasma and in Human Spermatozoa. Int. J. Androl. 2003, 26, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almabhouh, F.A.; Osman, K.; Siti Fatimah, I.; Sergey, G.; Gnanou, J.; Singh, H.J. Effects of Leptin on Sperm Count and Morphology in Sprague-Dawley Rats and Their Reversibility Following a 6-Week Recovery Period. Andrologia 2015, 47, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, C.F.; Zamoner, A. Thyroid Hormone and Leptin in the Testis. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.B.; Walker, W.H. The Regulation of Spermatogenesis by Androgens. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2014, 30, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhao, G.; Song, Y.; Haire, A.; Yang, A.; Zhao, X.; Wusiman, A. Presence of Leptin and Its Receptor in the Ram Reproductive System and in Vitro Effect of Leptin on Sperm Quality. PeerJ 2022, 10, e13982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.F.; Aguila, M.B.; Mandarim-de-Lacerda, C.A. Impaired Steroidogenesis in the Testis of Leptin-Deficient Mice (Ob/Ob. -/-). Acta Histochem. 2017, 119, 508–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önel, T.; Ayla, S.; Keskin, İ.; Parlayan, C.; Yiğitbaşı, T.; Kolbaşı, B.; Yelke, T.V.; Ustabaş, T.Ş. Leptin in Sperm Analysis Can Be a New Indicator. Acta Histochem. 2019, 121, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutari, C.; Pappas, P.D.; Mintziori, G.; Nigdelis, M.P.; Athanasiadis, L.; Goulis, D.G.; Mantzoros, C.S. The Effect of Underweight on Female and Male Reproduction. Metabolism 2020, 107, 154229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, E.; Signorini, C.; Noto, D.; Tripodi, S.A.; Menchiari, A.; Sorrentino, E.; Collodel, G. Seminal Levels of Omentin-1/ITLN1 in Inflammatory Conditions Related to Male Infertility and Localization in Spermatozoa and Tissues of Male Reproductive System. J. Inflamm. Res. 2022, 15, 2019–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumaud, P.; Martin, L.J. Roles of Leptin, Adiponectin and Resistin in the Transcriptional Regulation of Steroidogenic Genes Contributing to Decreased Leydig Cells Function in Obesity. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2015, 24, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, I.V.; Yango, P.; Svechnikov, K.; Tran, N.D.; Söder, O. Adipocytokines May Delay Pubertal Maturation of Human Sertoli Cells. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2019, 31, 1395–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, E.; Collodel, G.; Mazzi, L.; Campagna, M.; Iacoponi, F.; Figura, N. Resistin, Interleukin-6, Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha, and Human Semen Parameters in the Presence of Leukocytospermia, Smoking Habit, and Varicocele. Fertil. Steril. 2014, 102, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, W.; Yousaf, I.; Latif, R.; Aslam, M. Effect of Visfatin on Testicular Steroidogenesis in Purified Leydig Cells. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad 2012, 24, 62–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rahmanifar, F.; Tabandeh, M.R. Adiponectin and Its Receptors Gene Expression in the Reproductive Tract of Ram. Small Rumin. Res. 2012, 105, 263–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledoux, S.; Campos, D.B.; Lopes, F.L.; Dobias-Goff, M.; Palin, M.F.; Murphy, B.D. Adiponectin Induces Periovulatory Changes in Ovarian Follicular Cells. Endocrinology 2006, 147, 5178–5186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thaqi, G.; Berisha, B.; Pfaffl, M.W. Expression Dynamics of Adipokines during Induced Ovulation in the Bovine Follicles and Early Corpus Luteum. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2024, 59, e14624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeszko, K.; Smolinska, N.; Kiezun, M.; Dobrzyn, K.; Maleszka, A.; Kaminski, T. The Influence of Adiponectin on the Transcriptomic Profile of Porcine Luteal Cells. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2016, 16, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chappaz, E.; Albornoz, M.S.; Campos, D.; Che, L.; Palin, M.F.; Murphy, B.D.; Bordignon, V. Adiponectin Enhances in Vitro Development of Swine Embryos. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2008, 35, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brochu-Gaudreau, K.; Beaudry, D.; Blouin, R.; Bordignon, V.; Murphy, B.D.; Palin, M.-F. Adiponectin Regulates Gene Expression in the Porcine Uterus; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008; ISBN 0006-3363. [Google Scholar]

- Maleszka, A.; Smolinska, N.; Nitkiewicz, A.; Kiezun, M.; Chojnowska, K.; Dobrzyn, K.; Szwaczek, H.; Kaminski, T. Adiponectin Expression in the Porcine Ovary during the Oestrous Cycle and Its Effect on Ovarian Steroidogenesis. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2014, 2014, 957076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiezun, M.; Dobrzyn, K.; Zaobidna, E.; Rytelewska, E.; Kisielewska, K.; Gudelska, M.; Orzechowska, K.; Kopij, G.; Szymanska, K.; Kaminska, B.; et al. Adiponectin Affects Uterine Steroidogenesis during Early Pregnancy and the Oestrous Cycle: An in Vitro Study. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2022, 245, 107067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoraszczuk, E.Ł.; Ptak, A. In Vitro Effect of Leptin on Growth Hormone (GH)- and Insulin-Like Growth Factor-I (IGF-I)-Stimulated Progesterone Secretion and Apoptosis in Developing and Mature Corpora Lutea of Pig Ovaries. J. Reprod. Dev. 2005, 51, 727–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecia, J.A.; Forcada, F.; Palacín, I.; Sánchez-Prieto, L.; Sosa, C.; Fernández-Foren, A.; Meikle, A. Undernutrition Affects Embryo Quality of Superovulated Ewes. Zygote 2015, 23, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estienne, A.; Brossaud, A.; Reverchon, M.; Ramé, C.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. Adipokines Expression and Effects in Oocyte Maturation, Fertilization and Early Embryo Development: Lessons from Mammals and Birds. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoraszczuk, E.L.; Rak, A.; Wójtowicz, A.; Ptak, A.; Wojciechowicz, T.; Nowak, K.W. Gh and Igf-i Increase Leptin Receptor Expression in Prepubertal Pig Ovaries: The Role of Leptin in Steroid Secretion and Cell Apoptosis. Acta Vet. Hung. 2006, 54, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.; Zhu, H.; Dyce, P.W.; Petrik, J.; Li, J. Leptin Enhances Oocyte Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Maturation via the Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Pathway. Endocrinology 2004, 145, 5355–5363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wołodko, K.; Castillo-fernandez, J.; Kelsey, G.; Galvão, A. Revisiting the Impact of Local Leptin Signaling in Folliculogenesis and Oocyte Maturation in Obese Mothers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.; Paczkowski, M.; Krisher, R.L. The Effect of Leptin on Maturing Porcine Oocytes Is Dependent on Glucose Concentration. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2012, 79, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalamma, P.; Kona, S.S.R.; Praveen Chakravarthi, V.; Siva Kumar, A.V.N.; Punyakumari, B.; Rao, V.H. Effect of Leptin on in Vitro Development of Ovine Preantral Ovarian Follicles. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pich, K.; Respekta-Długosz, N.; Dawid, M.; Rame, C.; Smolińska, N.; Dupont, J.; Rak, A. In Vitro Effect of Omentin-1 on Level of Other Adipokines in Granulosa Cells from Ovaries of Large White and Meishan Pigs. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2025, 274, 107783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aygormez, S.; Atakisi, E. Investigation of Omentin-1 and Metabolic Parameters in Periparturient Cows. J. Hell. Vet. Med. Soc. 2021, 72, 2733–2740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurowska, P.; Gazdzik, K.; Jasinska, A.; Mlyczynska, E.; Wachowska, D.; Rak, A. Resistin as a New Player in the Regulation of Porcine Corpus Luteum Luteolysis: In Vitro Effect on Proliferation/Viability, Apoptosis and Autophagy. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2023, 74, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaqi, G.; Berisha, B.; Pfaffl, M.W. Expression of Locally Produced Adipokines and Their Receptors during Different Physiological and Reproductive Stages in the Bovine Corpus Luteum. Animals 2023, 13, 1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, M.; Ramé, C.; Cognié, J.; Briant, E.; Elis, S.; Guillaume, D.; Dupont, J. Resistin in Dairy Cows: Plasma Concentrations during Early Lactation, Expression and Potential Role in Adipose Tissue. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.; Locher, L.; Huber, K.; Kenéz, Á.; Rehage, J.; Tienken, R.; Meyer, U.; Dänicke, S.; Sauerwein, H.; Mielenz, M. Longitudinal Changes in Adipose Tissue of Dairy Cows from Late Pregnancy to Lactation. Part 1: The Adipokines Apelin and Resistin and Their Relationship to Receptors Linked with Lipolysis. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 1549–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, M.; Rame, C.; Bunel, A.; Chen, W.; Froment, P.; Dupont, J. VISFATIN (NAMPT) Improves in Vitro IGF1-Induced Steroidogenesis and IGF1 Receptor Signaling through SIRT1 in Bovine Granulosa Cells. Biol. Reprod. 2016, 94, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, A.T.; Knight, P.A.; David Smith, W.; Pate, J.A.; Miller, H.R.P.; Pemberton, A.D. Expression of Three Intelectins in Sheep and Response to a Th2 Environment. Vet. Res. 2009, 40, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhlhausler, B.S.; Duffield, J.A.; McMillen, I.C. Increased Maternal Nutrition Stimulates Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor-γ, Adiponectin, and Leptin Messenger Ribonucleic Acid Expression in Adipose Tissue before Birth. Endocrinology 2007, 148, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, C.M.; Vickers, M.H. The Role of Adipokines in Developmental Programming: Evidence from Animal Models. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 242, T81–T94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.; Bal, N.C. Adipokines from White Adipose Tissue in Regulation of Whole Body Energy Homeostasis. Biochimie 2023, 204, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoane-Collazo, P.; Martínez-Sánchez, N.; Milbank, E.; Contreras, C. Incendiary Leptin. Nutrients 2020, 12, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cravo, R.M.; Margatho, L.O.; Osborne-Lawrence, S.; Donato, J.; Atkin, S.; Bookout, A.L.; Rovinsky, S.; Frazão, R.; Lee, C.E.; Gautron, L.; et al. Characterization of Kiss1 Neurons Using Transgenic Mouse Models. Neuroscience 2011, 173, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, C.L.; Williams, P.A.; Milne, J.S.; Aitken, R.P.; Wallace, J.M. Orexigenic Gene Expression in Late Gestation Ovine Foetal Hypothalamus Is Sensitive to Maternal Undernutrition and Realimentation. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2015, 27, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuersunjiang, N.; Odhiambo, J.F.; Shasa, D.R.; Smith, A.M.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Ford, S.P. Maternal Obesity Programs Reduced Leptin Signaling in the Pituitary and Altered GH/IGF1 Axis Function Leading to Increased Adiposity in Adult Sheep Offspring. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaideen, M.; Önel, T.; Yıldırım, E.; Yaba, A. The Role of Leptin in the Male Reproductive System. J. Turk. Ger. Gynecol. Assoc. 2024, 25, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, I.A.; Durairajanayagam, D.; Singh, H.J. Leptin and Its Actions on Reproduction in Males. Asian J. Androl. 2019, 21, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, X.; Hu, L.; Li, H. Exogenous Leptin Affects Sperm Parameters and Impairs Blood Testis Barrier Integrity in Adult Male Mice. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, G.K.; Sea, T.L.; Olatinwo, M.O.; Simorangkir, D.; Ford, G.D.; Ford, B.D.; Mann, D.R. Influence of a Leptin Deficiency on Testicular Morphology, Germ Cell Apoptosis, and Expression Levels of Apoptosis-Related Genes in the Mouse. J. Androl. 2006, 27, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavaud, C.; Ferlay, A.; Faulconnier, Y.; Bocquier, F.; Kann, G.; Chilliard, Y. Plasma Leptin Concentration in Adult Cattle: Effects of Breed, Adiposity, Feeding Level, and Meal Intake. J. Anim. Sci. 2002, 80, 1317–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bispham, J.; Gopalakrishnan, G.S.; Dandrea, J.; Wilson, V.; Budge, H.; Keisler, D.H.; Broughton Pipkin, F.; Stephenson, T.; Symonds, M.E. Maternal Endocrine Adaptation throughout Pregnancy to Nutritional Manipulation: Consequences for Maternal Plasma Leptin and Cortisol and the Programming of Fetal Adipose Tissue Development. Endocrinology 2003, 144, 3575–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bispham, J.; Budge, H.; Mostyn, A.; Dandrea, J.; Clarke, L.; Keisler, D.H.; Symonds, M.E.; Stephenson, T. Ambient Temperature, Maternal Dexamethasone, and Postnatal Ontogeny of Leptin in the Neonatal Lamb. Pediatr. Res. 2002, 52, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.A.; Choi, K.M. Newly Discovered Adipokines: Pathophysiological Link between Obesity and Cardiometabolic Disorders. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 568800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.; Pollet-Villard, X.; Reverchon, M.; Mellouk, N.; Levy, R. Adipokines in Human Reproduction. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 2015, 24, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, H. Vascular Effects of Novel Adipocytokines: Focus on Vascular Contractility and Inflammatory Responses. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, X.; Li, X.; Liu, F.; Tan, H.; Shang, D. Omentin Inhibits TNF-α-Induced Expression of Adhesion Molecules in Endothelial Cells via ERK/NF-κB Pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 425, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Respekta, N.; Pich, K.; Mlyczyńska, E.; Dobrzyń, K.; Ramé, C.; Kamiński, T.; Smolińska, N.; Dupont, J.; Rak, A. Plasma Level of Omentin-1, Its Expression, and Its Regulation by Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone and Gonadotropins in Porcine Anterior Pituitary Cells. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 19325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, F.F.; Amarante, M.d.S.M.; Oliveira, D.S.; Vasques-Monteiro, I.M.L.; Souza-Mello, V.; Daleprane, J.B.; Camillo, C.D.S. Obesity, White Adipose Tissue, and Adipokines Signaling in Male Reproduction. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2025, 69, e70054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pich, K.; Respekta, N.; Kurowska, P.; Rame, C.; Dobrzyń, K.; Smolińska, N.; Dupont, J.; Rak, A. Omentin Expression in the Ovarian Follicles of Large White and Meishan Sows during the Oestrous Cycle and in Vitro Effect of Gonadotropins and Steroids on Its Level: Role of ERK1/2 and PI3K Signaling Pathways. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0297875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.D.; Rajala, M.W.; Rossetti, L.; Scherer, P.E.; Shapiro, L. Disulfide-Dependent Multimeric Assembly of Resistin Family Hormones. Science 2004, 304, 1154–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarkowski, A.; Bjersing, J.; Shestakov, A.; Bokarewa, M.I. Resistin Competes with Lipopolysaccharide for Binding to Toll-like Receptor 4. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 1419–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maillard, V.; Elis, S.; Desmarchais, A.; Hivelin, C.; Lardic, L.; Lomet, D.; Uzbekova, S.; Monget, P.; Dupont, J. Visfatin and Resistin in Gonadotroph Cells: Expression, Regulation of LH Secretion and Signalling Pathways. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2017, 29, 2479–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.K.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, H.; Park, S.J.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, G.B.; Lee, Y.S.; Kim, J.B.; Kim, K.K.; Suh, S.W. Crystal Structure of Visfatin/Pre-B Cell Colony-Enhancing Factor 1/Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase, Free and in Complex with the Anti-Cancer Agent FK-866. J. Mol. Biol. 2006, 362, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, G.; Garten, A.; Petzold, S.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G.; Blüher, M.; Stumvoll, M.; Fasshauer, M. Visfatin/PBEF/Nampt: Structure, Regulation and Potential Function of a Novel Adipokine. Clin. Sci. 2008, 115, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, J.; Mills, K.F.; Yoon, M.J.; Imai, S. Nicotinamide Mononucleotide, a Key NAD+ Intermediate, Treats the Pathophysiology of Diet-and Age-Induced Diabetes in Mice. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, C.B.; Mayer, A.L.; Zhang, Y.; Franczyk, M.; Ballentine, S.; Yoshino, J.; DeBosch, B.J. SIRT1 Selectively Exerts the Metabolic Protective Effects of Hepatocyte Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saddi-Rosa, P.; Oliveira, C.S.; Giuffrida, F.M.; Reis, A.F. Visfatin, Glucose Metabolism and Vascular Disease: A Review of Evidence. Diabetol. Metab. Syndr. 2010, 2, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlyczyńska, E.; Kieżun, M.; Kurowska, P.; Dawid, M.; Pich, K.; Respekta, N.; Daudon, M.; Rytelewska, E.; Dobrzyń, K.; Kamińska, B.; et al. New Aspects of Corpus Luteum Regulation in Physiological and Pathological Conditions: Involvement of Adipokines and Neuropeptides. Cells 2022, 11, 957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminska, B.; Kurowicka, B.; Kiezun, M.; Dobrzyn, K.; Kisielewska, K.; Gudelska, M.; Kopij, G.; Szymanska, K.; Zarzecka, B.; Koker, O.; et al. The Role of Adipokines in the Control of Pituitary Functions. Animals 2024, 14, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shasa, D.R.; Odhiambo, J.F.; Long, N.M.; Tuersunjiang, N.; Nathanielsz, P.W.; Ford, S.P. Multigenerational Impact of Maternal Overnutrition/Obesity in the Sheep on the Neonatal Leptin Surge in Granddaughters. Int. J. Obes. 2015, 39, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.J.; Choi, S.-E.; Jeon, J.Y.; Han, S.J.; Kim, D.J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, K.W.; Kim, H.J. Visfatin Induces Inflammation and Insulin Resistance via the NF-κB and STAT3 Signaling Pathways in Hepatocytes. J. Diabetes Res. 2019, 2019, 4021623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorena, K.; Jachimowicz-Duda, O.; Ślęzak, D.; Robakowska, M.; Mrugacz, M. Adipokines and Obesity. Potential Link to Metabolic Disorders and Chronic Complications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannarella, R.; Crafa, A.; Curto, R.; Condorelli, R.A.; La Vignera, S.; Calogero, A.E. Obesity and Male Fertility Disorders. Mol. Asp. Med. 2024, 97, 101273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ocon-Grove, O.M.; Krzysik-Walker, S.M.; Maddineni, S.R.; Hendricks, G.L.; Ramachandran, R. NAMPT (Visfatin) in the Chicken Testis: Influence of Sexual Maturation on Cellular Localization, Plasma Levels and Gene and Protein Expression. Reproduction 2010, 139, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riammer, S.; Garten, A.; Schaab, M.; Grunewald, S.; Kiess, W.; Kratzsch, J.; Paasch, U. Nicotinamide Phosphoribosyltransferase Production in Human Spermatozoa Is Influenced by Maturation Stage. Andrology 2016, 4, 1045–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeremy, M.; Gurusubramanian, G.; Roy, V.K. Localization Pattern of Visfatin (NAMPT) in d-Galactose Induced Aged Rat Testis. Ann. Anat.-Anat. Anz. 2017, 211, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choubey, M.; Nikolettos, N. Editorial: Adipose Tissue and Adipokines: Their Roles in Human Reproduction. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1497744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolettos, K.; Vlahos, N.; Pagonopoulou, O.; Nikolettos, N.; Zikopoulos, K.; Tsikouras, P.; Kontomanolis, E.; Damaskos, C.; Garmpis, N.; Psilopatis, I.; et al. The Association between Leptin, Adiponectin Levels and the Ovarian Reserve in Women of Reproductive Age. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1369248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Xue, X.; Zhou, J.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, B.; Ou, G.; Zhou, Q. Male Infertility Risk and Plasma Lipidome: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1412684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.A.; Scherer, P.E. Update on Adipose Tissue and Cancer. Endocr. Rev. 2023, 44, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reytor-González, C.; Simancas-Racines, D.; Román-Galeano, N.M.; Campuzano-Donoso, M.; Carella, A.M.; Zambrano-Villacres, R.; Marinelli, T.; Coppola, L.; Marchetti, M.; Galasso, M.; et al. Obesity and Breast Cancer: Exploring the Nexus of Chronic Inflammation, Metabolic Dysregulation, and Nutritional Strategies. Food Agric. Immunol. 2025, 36, 2521270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carapeto, B.F.A.; Pisani, L.P. Cancer and Obesity: The Role of Adipokines in Their Interaction. Nutrire 2025, 50, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duggan, C.; Irwin, M.L.; Xiao, L.; Henderson, K.D.; Smith, A.W.; Baumgartner, R.N.; Baumgartner, K.B.; Bernstein, L.; Ballard-Barbash, R.; McTiernan, A. Associations of Insulin Resistance and Adiponectin with Mortality in Women with Breast Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocian-Jastrzębska, A.; Malczewska-Herman, A.; Kos-Kudła, B. Role of Leptin and Adiponectin in Carcinogenesis. Cancers 2023, 15, 4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, S.R.; Skolariki, A.; Zameer, M.Z.; Lord, S.R. Implications of Obesity and Insulin Resistance for the Treatment of Oestrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2024, 131, 1724–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dec, P.; Poniewierska-Baran, A.; Modrzejewski, A.; Pawlik, A. The Role of Omentin-1 in Cancers Development and Progression. Cancers 2023, 15, 3797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobre, M.-Z.; Virgolici, B.; Timnea, O. Key Roles of Brown, Subcutaneous, and Visceral Adipose Tissues in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Hernández, A.; de las Heras, N.; Gálvez, B.G.; Fernández-Marcelo, T.; Fernández-Millán, E.; Escribano, Ó. New Mediators in the Crosstalk between Different Adipose Tissues. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vetrani, C.; Di Nisio, A.; Paschou, S.A.; Barrea, L.; Muscogiuri, G.; Graziadio, C.; Savastano, S.; Colao, A.; on behalf of the Obesity Programs of Nutrition, Education, Research and Assessment (OPERA) Group. From Gut Microbiota through Low-Grade Inflammation to Obesity: Key Players and Potential Targets. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Montoro, J.I.; Damas-Fuentes, M.; Fernández-García, J.C.; Tinahones, F.J. Role of the Gut Microbiome in Beta Cell and Adipose Tissue Crosstalk: A Review. Front. Endocrinol. 2022, 13, 869951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Adipokines | Effects |

|---|---|

| Adiponectin | AdipoRs present in the hypothalamus, particularly in the hypothalamic GnRH neuron cells [23]. |

| Inhibition of KISS 1 gene transcription and GnRH secretion [25,26]. | |

| Increase in FSH release in primary pituitary cells [27]. | |

| Reduction in LH secretion and GnRH-induced LH release in pituitary cell cultures [28,29]. | |

| AdipoRs present in gonadotropin-producing cells [30]. Restricted feeding increases serum adiponectin and downregulates GnRH, LHβ, and FSHβ production [31]. | |

| Leptin | Stimulation of GnRH secretion, mediated by KISS [32,33]. |

| Energy status and circulating leptin levels modulate GnRH neurons with disrupting GnRH pulsatile release [14,34,35]. | |

| LEPRs present in pituitary cells [36]. | |

| Increase in mRNA expression for activin in gonadotropes [37]. | |

| Stimulation of GH–IGF-1 axis and, in turn, of GnRH and LH release [38]. | |

| Omentin | Direct action on hypothalamic neurons; however, the effect on GnRH release remains unknown [39]. |

| Resistin | Inhibitory effect on LH secretion [40]. |

| Visfatin | Effects on GnRH secretion from the hypothalamus and LH from the pituitary [16]. |

| Reduction in hypothalamic KISS-1 mRNA expression [41]. |

| Adipokines | Effects |

|---|---|

| Adiponectin | Inhibition of basal and human choriogonadotropin-stimulated testosterone secretion Ex Vivo [42]. |

| Induction of testosterone production from the Leydig cells [43]. | |

| Indices of sperm motility significantly correlated with the expression of AdipoR1 [44]. | |

| Positive association with sperm concentration, total sperm count, and percentage of spermatozoa with normal morphology [45]. | |

| AdipoR1 presence and location and its gene expression in the reproductive tissues of the male ram, during its nonbreeding season [46]. | |

| Leptin | Receptors in spermatozoa, germ cells, somatic cells, epididymis-mis, Leydig cells, Sertoli cells and epithelial cells of seminal vesicles and prostate [47,48]. |

| Modulation of testosterone production in Leydig cells and androgen-binding protein, testicular fluid, inhibin, activin in Sertoli cells [49,50]. | |

| Reduction in oxidative stress and sperm apoptosis [51]. | |

| In male ob/ob mice, the absence of leptin leads to a lack of fertility, which is restored with leptin therapy [52,53,54]. | |

| Omentin | Inflammatory conditions increase its levels, while they are negatively correlated with sperm parameters [55]. |

| Resistin | In Leydig cells, decrease in STAR expression and steroidogenesis [56]. |

| In Sertoli cells, interruption of maturation and maintenance of the prepubertal quiescent state [57]. | |

| Negative correlation with sperm motility and vitality [58]. | |

| Visfatin | In cultured Leydig cells, induction of testosterone secretion [59]. |

| Negative correlation with sperm parameters [41]. |

| Adipokines | Effects |

|---|---|

| Adiponectin | Stimulation of genes for COX2, PGE synthase, and VEGF, in granulosa cells [61]. |

| Upregulation of AdipoR2 in GnRH-treated granulosa cells [62]. | |

| Modulation of genes for steroidogenesis, PG synthesis, and vascularization in luteal cells [63]. | |

| In vitro improvement of embryo development to the blastocyst stage [64]. | |

| Affects PG synthesis and VEGF expression in endometrial cells during pregnancy [65]. | |

| Modulation of StAR and CYP19A3 in the endometrium and myometrium during pregnancy and estrous cycle [66,67]. | |

| Leptin | Modulation of estradiol secretion in vitro [68]. Food deprivation, which determines low levels of leptin, reduces oocyte quality [69,70]. |

| Antiapoptotic properties by suppressing caspase-3 activity and counteracting IGF-I effects in CL [71]. | |

| Activation of the MAPK pathway, increase in oocyte maturation to metaphase II stage, expression of cyclin B1 and embryo development [72,73]. | |

| Protection of oocytes from high-glucose-level damage, enhancing glycolysis and maturation [74]. | |

| Increase in antrum formation, follicular growth, and the proportion of oocytes reaching metaphase II [75]. | |

| Omentin | Modulation of mRNA expression for adipokines and their receptors in granulosa cells, reducing apelin levels and increasing those of leptin [76]. |

| Levels were significantly higher at delivery compared to the pre- and post-parturition and positively correlated with plasma glucose, non-esterified fatty acids and β-hydroxybutyrate, and negatively with triglycerides [77]. | |

| Resistin | Enhances porcine luteal cell viability through autophagy, supporting CL function [78] Local involvement in CL regulation [79]. Oscillating expression related to pregnancy [80,81]. Positively correlated with NEFA; negatively with milk yield, DMI, and energy balance [80]. Recombinant resistin promotes lipid mobilization [80]. Early lactation reduces insulin sensitivity via reduction in IRβ, IRS-1/2, PKB, and MAPK/ERK1/2 phosphorylation [80]. |

| Visfatin | Supports granulosa cell steroidogenesis and proliferation [82]. |

| Alone or with IGF1 increases estradiol and progesterone, promoting follicular function and oocyte maturation [82]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez-Barbitta, M.; Biagini, A.; Costanzi, E.; Maranesi, M.; García-Díez, J.; Saraiva, C.; Goga, B.C.; Zerani, M. Adipose-Specific Cytokines as Modulators of Reproductive Activity. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123067

Martinez-Barbitta M, Biagini A, Costanzi E, Maranesi M, García-Díez J, Saraiva C, Goga BC, Zerani M. Adipose-Specific Cytokines as Modulators of Reproductive Activity. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123067

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez-Barbitta, Marcelo, Andrea Biagini, Egidia Costanzi, Margherita Maranesi, Juan García-Díez, Cristina Saraiva, Beniamino Cenci Goga, and Massimo Zerani. 2025. "Adipose-Specific Cytokines as Modulators of Reproductive Activity" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123067

APA StyleMartinez-Barbitta, M., Biagini, A., Costanzi, E., Maranesi, M., García-Díez, J., Saraiva, C., Goga, B. C., & Zerani, M. (2025). Adipose-Specific Cytokines as Modulators of Reproductive Activity. Biomedicines, 13(12), 3067. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123067