Abstract

Objective: Cardiac hypertrophy, a key feature and predisposing factor of heart failure, is mainly controlled by complex signaling cascades. Growth differentiation factor 6 (GDF6) plays critical roles in cell growth and cardiovascular homeostasis; however, its role and underlying mechanisms in cardiac hypertrophy remain unclear. Methods: Mice were intravenously injected with adeno-associated virus serotype 9 to overexpress and knock down GDF6 in murine hearts and then exposed to transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery to generate pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Echocardiographic, histological, and molecular analyses were performed to decipher the alterations to cardiac hypertrophy. In addition, neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were isolated and stimulated with phenylephrine (PE) to further validate its involvement in hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes. Results: GDF6 expression was elevated in murine hearts and NRVMs by ROS production under hypertrophic stimuli. GDF6 knockdown aggravated, while GDF6 overexpression attenuated, pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation, and dysfunction in vivo. Meanwhile, we found that GDF6 also prevented PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs in vitro. Mechanistically, GDF6 activated AMPKα to exert cardioprotective effects, and AMPKα inhibition significantly blocked the anti-hypertrophic effects of GDF6. Further studies showed that GDF6 activated AMPKα through the cAMP/Epac1 pathway, and that Epac1 knockdown abolished the protective effects of GDF6 against TAC- or PE-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo and in vitro. Conclusions: In general, our findings, for the first time, define GDF6 as a negative regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and show that supplementation of GDF6 may be of great therapeutic interest for heart failure.

1. Introduction

Cardiac hypertrophy is a key feature and predisposing factor of heart failure, which is characterized by myocyte enlargement, re-activation of fetal gene programs, chronic inflammation, and cardiac dysfunction [1,2,3,4]. Despite extensive studies, the mechanisms of cardiac hypertrophy remain poorly understood. Generally, cardiac hypertrophy is mainly controlled by complex signaling cascades, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/AKT), mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), calcineurin/nuclear factor of activated T cells (CaN/NFATs), etc. [1,5,6,7,8,9]. 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase α (AMPKα) was initially identified as an energy sensor to regulate intracellular metabolic homeostasis; however, emerging studies have defined it as an attractive molecular target to treat various cardiovascular diseases, including cardiac hypertrophy [10,11,12]. Stuck et al. found that angiotensin II (Ang II)-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy was accompanied by decreased activation of AMPKα, and that AMPKα activation significantly inhibited cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [13]. Zhang et al. reported that AMPKα deficiency had no effect on cardiac structure or function at baseline, but dramatically increased pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in mice [14]. Moreover, activating AMPKα also reduced inflammation in hypertrophic hearts and thereby prevented pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy [15,16]. Therefore, activating AMPKα is of great therapeutic interest for treating cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction.

Growth differentiation factors (GDFs) belong to the evolutionarily conserved transforming growth factor-β superfamily, and are mainly implicated in embryonic development [17]. GDF6 is a member of the GDFs family and plays critical roles in cell growth and cardiovascular homeostasis. Asai-Coakwell et al. detected an increased retinal apoptosis in GDF6-deficient zebrafish embryos [18]. Harrison et al. demonstrated that fibroblast-derived GDF6 facilitated vascular smooth muscle cell growth, thereby aggravating Ang II-induced vascular remodeling and hypertension [19]. In addition, GDF6 overexpression could promote the differentiation of C3H10T1/2 murine embryonic fibroblast cells to cardiomyocyte-like cells in vitro [20]. Wu et al. also found that GDF6 significantly augmented the endothelial angiogenesis and promoted the cardiac function recovery of infarcted hearts [21]. Yet, its role and underlying mechanisms in cardiac hypertrophy remain unclear. The present study tries to overexpress and knock down GDF6 in murine hearts using adeno-associated virus serotype 9 (AAV9) and then establishes transverse aortic constriction (TAC)-induced cardiac hypertrophy to decipher its role in pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction.

In our study, we detect an increased expression of GDF6 in hypertrophic hearts and cardiomyocytes. Gain- and loss-of-function studies indicate that GDF6 knockdown aggravates, while GDF6 overexpression attenuates, pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, inflammation, and dysfunction in vivo and in vitro. Mechanistically, GDF6 activates AMPKα through cyclic AMP/exchange protein that is directly activated by the cAMP 1 (cAMP/Epac1) pathway to exert cardioprotective effects, and AMPKα inhibition significantly blocks the anti-hypertrophic effects of GDF6. In summary, our findings, for the first time, define GDF6 as a negative regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and show that supplementation of GDF6 may be of great therapeutic interest for heart failure.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

Nanoparticle In Vivo Transfection Reagent (#5031) was purchased from Altogen Biosystems (Las Vegas, NV, USA). N-Acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC, #A7250), apocynin (APO, #178385), compound C (CpC, #171260), 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU, #B5002), (R)-(-)-phenylephrine hydrochloride (PE, #P6126), 2′,5′-dideoxyadenosine (2′5′-dd-Ado, an adenylyl cyclase/AC inhibitor, #D7408), and H-89 dihydrochloride hydrate (H89, a protein kinase A/PKA inhibitor, #B1427) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (#23227), TRIzol reagent (#15596026), Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Reagent (#13778150), Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 568 (#A-11011), and SlowFade™ Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI (#S36939) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (#11483188001) and FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master (#4913914001) were purchased from Roche (Basel, Switzerland). Mouse GDF6 ELISA Kit (#MBS034852) was purchased from MyBioSource (San Diego, CA, USA), and recombinant human GDF6 (rhGDF6, #120-04) was purchased from PeproTech (Cranbury, NJ, USA). Mouse IL-1 beta ELISA Kit (#ab197742), Rat IL-1 beta ELISA Kit (#ab255730), Mouse IL-6 ELISA Kit (#ab222503), Rat IL-6 ELISA Kit (#ab234570), Mouse TNF alpha ELISA Kit (#ab208348), Rat TNF alpha ELISA Kit (#ab236712), cAMP Assay Kit (#ab65355), and Protein Kinase A Kinase Activity Assay Kit (#ab139435) were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Active Rap1 Detection Kit (#8818) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). AAV9 carrying short hairpin RNA against GDF6 (AAV9-shGdf6), full-length mouse GDF6 (AAV9-Gdf6), or scramble controls (AAV9-shCtrl for AAV9-shGdf6 and AAV9-Ctrl for AAV9-Gdf6) under a cardiomyocyte-specific cTnT promoter were generated by Shanghai GeneChem Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Small interfering RNA against rat Epac1 (siEpac1, #SR506839), rat GDF6 (siGdf6, #SR513148), mouse Epac1 (#SR420934), and rat AMPKα2 (siAmpka2, #SR508585) were purchased from OriGene (Rockville, MD, USA).

2.2. Animals and Experiments

Male C57BL/6 mice (8–12 weeks, 22–28 g) were purchased from Beijing HFK Bioscience Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and kept in a SPF environment with controlled temperature (20–25 °C) and humidity (52–58%) under 12/12 h dark/light cycles. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Welfare & Ethics Committee of our hospital and were also in accordance with the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Institutes of Health Publication No. 85-23, revised 1996). TAC surgery was performed to establish pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy as previously described [2]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and then exposed to thoracotomy. Next, the transverse aortic arch was surgically isolated and ligated with a 27 G needle using a 7-0 thin thread. Then, the needle was removed, and adequate aortic constriction was verified by Doppler echocardiogram. Mice in sham groups received a similar thoracotomy with no ligation of the transverse aortic arch. To scavenge reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the heart, TAC-operated mice were treated with NAC (500 mg/kg/day) or APO (100 mg/kg/day) in the drinking water as previously described [22]. Four weeks before TAC or sham surgery, mice were intravenously injected with AAV9-shGdf6, AAV9-Gdf6, or matched controls (1 × 1011 viral genomes per mouse) to specifically knock down or overexpress GDF6 in murine hearts as previously described [23,24]. To inhibit AMPKα, mice were intraperitoneally injected with 20 mg/kg CpC every other day from 2 weeks after TAC surgery [25]. For Epac1 gene silence in vivo, mice were injected with chemically modified siEpac1 using a Nanoparticle In Vivo Transfection Reagent 3 times from 2 weeks after TAC surgery, as previously described [26]. Four weeks after TAC or sham surgery, all mice were euthanized by a cervical dislocation method, with the hearts, lungs, and tibias collected to calculate the heart weight to tibia length (HW/TL) and lung weight/tibia length (LW/TL) ratios.

2.3. Echocardiography

Cardiac function was measured by a Vevo 2100 ultrasound echocardiography system (VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada) as previously described [27,28,29]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized by 2% isoflurane, and then two-dimensional parasternal long-/short-axis views as well as an M-mode echocardiogram were captured, with the heart rate, left ventricle internal diameter at end-diastole (LVEDd), left ventricle internal diameter at end-systole (LVEDs), fractional shortening (FS), interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole (IVSd), and interventricular septal thickness at end-systole (IVSs) being calculated from at least 5 consecutive cardiac cycles.

2.4. Evaluation of Blood Pressure (BP)

BP was measured using a noninvasive CODA tail-cuff system (Kent Scientific, Litchfield, CT, USA) as previously described [30]. Briefly, mice were adapted and fixed in the pre-heating plate, with the tail or head placed in a hole or the nose fixator of the device, respectively. The pressurized tail sleeve was placed on the tail root, and the sensor was positioned near the pressurized tail sleeve. Next, the program was started, and BP values were recorded.

2.5. Western Blot

Total proteins were extracted from murine hearts and cells by RIPA lysis buffer containing a protease inhibitor cocktail and phosphatase inhibitors [31,32,33]. After quantification with a Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit and denaturation, equal amounts of total proteins were loaded, separated, and transferred onto PVDF membranes. Next, the membranes were blocked, incubated at 4 °C overnight with anti-GDF6 (#ab73288; Abcam), anti-β-actin (#ab8226; Abcam), anti-phospho-AMPKα (p-AMPKα, #2535; CST, Danvers, MA, USA), and anti-total-AMPKα (t-AMPKα, #5832; CST) at a dilution of 1:1000, and then incubated with horse radish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Afterwards, the protein bands were visualized via enhanced chemiluminescence and analyzed using Image Lab 6.0 software.

2.6. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total mRNA was extracted from murine hearts and cells by TRIzol reagent, and then converted to cDNA using a First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit following the manufacturer’s instructions [34,35,36,37]. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a FastStart Universal SYBR Green Master under the following conditions: 95 °C for 5 min, 95 °C for 45 s, and 60 °C for 1 min for 45 cycles. Gene expression was normalized to β-actin (encoded by Actb) gene expression, and primer sequences were as follows: Gdf6 5′-TAGCTTCCTCTGGGATTTGC-3′; 5′-GAGGAGGAGGACGAGGAGAT-3′; Actb 5′-CTGTCGAGTCGCGTCCACCC-3′; 5′-ATGCCGGAGCCGTTGTCGAC-3′; Nppa 5′-CACAGATCTGATGGATTTCAAGA-3′; 5′-CCTCATCTTCTACCGGCATC-3′; Nppb 5′-ATGGATCTCCTGAAGGTGCTGT-3′; 5′-GCAGCTTGAGATATGTGTCACC-3′; Myh6 5′-GCCCAGTACCTCCGAAAGTC-3′; 5′-GCCTTAACATACTCCTCCTTGTC-3′; Myh7 5′-CGCATCAAGGAGCTCACC-3′; 5′-CTGCAGCCGCAGTAGGTT-3′; Epac1 5′-TCTTACCAGCTAGTGTTCGAGC-3′; 5′-AATGCCGATATAGTCGCAGATG-3′.

2.7. GDF6 ELISA Assay

Heart homogenates and cell medium were prepared following the manufacturer’s instructions, added to the 96-well plates, and then incubated with 100 μL HRP-Conjugate Reagent at 37 °C for 1 h. After washing 4 times, 50 µL Chromogen Solution A and 50 µL Chromogen Solution B per well were added to the plates, which were then incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 15 min. This was followed by a reaction with 50 µL Stop Solution. Finally, the optical density was detected at 450 nm by a microplate reader.

2.8. Hematoxylin–Eosin Staining

Cross sectional area (CSA) of cardiomyocytes was evaluated by hematoxylin–eosin staining as previously described [38,39,40]. Briefly, hearts were harvested, fixed, dehydrated, embedded, and sectioned into 5 μm thick slices, which were then incubated with hematoxylin or eosin solution following standard protocols. CSA was calculated from more than 100 cells per group using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD, USA) in a blinded manner.

2.9. Cell Isolation and Treatments

Neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were isolated from 1- to 2-day-old Sprague–Dawley rats and incubated in DMEM/F12 containing 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS) as previously described, and BrdU (0.1 mmol/L) was used to inhibit the proliferation of cardiac fibroblasts in NRVMs [24,41]. To induce hypertrophic growth, NRVMs were incubated with 50 μmol/L PE for 24 h, while phosphate buffer saline (PBS) was used as the negative control. To inhibit ROS in vitro, NRVMs with PE stimulation were treated with NAC (10 mmol/L) or APO (100 µmol/L) as previously described [22]. For GDF6 silence in vitro, NRVMs were transfected with siGdf6 (50 nmol/L) for 6 h using a Lipofectamine RNAiMAX reagent, and then cultured in fresh DMEM/F12 containing 15% FBS for an additional 24 h before PE stimulation. Meanwhile, NRVMs were treated with rhGDF6 (4 µg/mL) or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 24 h in combination with PE stimulation to further investigate the role of GDF6 in vitro [19]. For AMPKα inhibition, NRVMs were pretreated with 20 μmol/L CpC for 12 h before rhGDF6 treatment [42]. To knock down Epac1, NRVMs were transfected with siEpac1 (50 nmol/L) for 6 h and cultured for an additional 24 h before rhGDF6 treatment. To inhibit AC or PKA, NRVMs were incubated with 2′5′-ddAdo (200 μmol/L) or H89 (10 μmol/L) in combination with rhGDF6 for 24 h.

2.10. Immunofluorescence Staining

Cell area was evaluated by immunofluorescence staining as previously described [43,44,45]. Briefly, NRVMs in coverslips were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 20 min, blocked with 10% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature, and then incubated with anti-sarcomeric α-actinin (#ab68167, Abcam) at 4 °C overnight. On the second day, coverslips were incubated with Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 568, and SlowFade™ Gold Antifade Mountant with DAPI for nuclei visualization.

2.11. Analysis of Intracellular cAMP Level, PKA Activity, Epac1 Activity and Inflammatory Cytokines

The levels of intracellular cAMP and PKA activity in NRVMs were analyzed using commercial kits, following the manufacturer’s instructions as previously described [46]. To evaluate Epac1 activity, the activity of downstream Rap1 was measured in NRVMs with GDF6 knockdown or supplementation using the Active Rap1 Detection Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The levels of inflammatory cytokines in the myocardium were measured using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as the mean ± S.D. and analyzed with SPSS 22.0 software. For animal experiments, n indicates different mice. For cell experiments, n indicates independent experiments. Student’s two-tailed t-test was performed to compare the means of two-group samples, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc test was applied for comparison of multiple groups. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. GDF6 Is Upregulated by ROS Production During Cardiac Hypertrophy

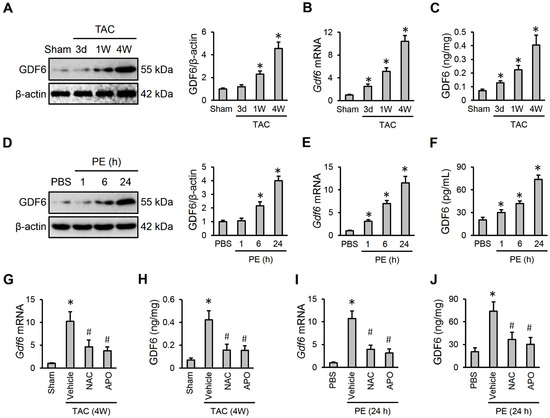

To explore the involvement of GDF6 in the pathogenesis of cardiac hypertrophy, we first determined whether GDF6 expression was altered during cardiac hypertrophy. As shown in Figure 1A,B, GDF6 mRNA and protein levels were gradually elevated in hypertrophic murine hearts. Using an ELISA kit, we also detected an upregulated GDF6 in murine hearts after TAC surgery (Figure 1C). To further clarify the alteration of GDF6, we also detected its expression during PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs. As shown in Figure 1D,E, GDF6 mRNA and protein levels in NRVMs were significantly elevated by PE stimulation. And the release of GDF6 to medium was also increased in the presence of PE (Figure 1F). ROS is implicated in various cardiovascular diseases, and is significantly elevated in hypertrophic hearts. Therefore, we detected whether ROS production contributed to increased GDF6 expression during cardiac hypertrophy by using the NADPH oxidase inhibitor APO or the ROS scavenger NAC. As shown in Figure 1G–J, both NAC and APO treatment significantly reversed GDF6 upregulation in hypertrophic hearts or NRVMs. These findings indicate that GDF6 is upregulated by ROS production during cardiac hypertrophy.

Figure 1.

Growth differentiation factor 6 (GDF6) is upregulated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) production during cardiac hypertrophy. (A,B) GDF6 mRNA and protein levels in murine hearts receiving sham or transverse aortic constriction (TAC) surgery. (C) GDF6 levels in murine hearts receiving sham or TAC surgery as determined by an ELISA kit. (D,E) GDF6 mRNA and protein levels in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) receiving phosphate buffer saline (PBS) or phenylephrine (PE) stimulation. (F) GDF6 levels in the medium from NRVMs receiving PBS or PE stimulation as determined by an ELISA kit. (G) GDF6 mRNA levels in murine hypertrophic hearts receiving N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) or apocynin (APO) treatment. (H) GDF6 levels in murine hypertrophic hearts receiving NAC or APO treatment as determined by an ELISA kit. (I) GDF6 mRNA levels in PE-stimulated NRVMs receiving NAC or APO treatment. (J) GDF6 levels in the medium from PE-stimulated NRVMs receiving NAC or APO treatment as determined by an ELISA kit. n = 6 per group. * p < 0.05 versus matched sham or PBS groups. In (G–J), * p < 0.05 versus matched sham or PBS groups, # p < 0.05 versus matched TAC-operated mice or PE-stimulated NRVMs receiving vehicle treatment. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey post hoc test was applied.

3.2. GDF6 Knockdown Aggravates Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy, Inflammation and Dysfunction

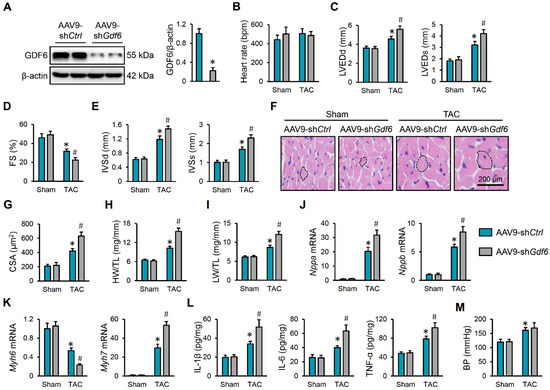

Next, mice were intravenously injected with AAV9-shGdf6 to specifically knock down GDF6 in murine hearts, and the efficiency was verified by Western blot (Figure 2A). As shown in Figure 2B–D, GDF6 knockdown did not affect the mice’s heart rate but further aggravated TAC-induced cardiac dilation and dysfunction in mice, as evidenced by increased LVEDd, LVEDs, and FS. Echocardiographic analysis also determined significant elevations of IVSd and IVSs in GDF6-silenced hearts, indicating exacerbated cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 2E). Consistently, hematoxylin–eosin staining revealed that GDF6 knockdown accelerated the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in response to pressure overload (Figure 2F,G). Meanwhile, we also detected increases in the HW/TL and LW/TL ratios in mice with AAV9-shGdf6 injection, which indicates an aggravated cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction (Figure 2H,I). In line with the phenotypic alterations, we found that GDF6 knockdown significantly elevated the mRNA levels of Nppa, Nppb, and Myh7, but further reduced the Myh6 mRNA level (Figure 2J,K). Chronic inflammation is a key feature and pathogenic factor of cardiac hypertrophy. Interestingly, we found that the increased levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in TAC-induced hearts were further elevated by GDF6 silence (Figure 2L). A previous study showed that GDF6 could facilitate vascular smooth muscle cell growth and that it aggravated Ang II-induced vascular remodeling and hypertension [19]. However, we found that GDF6 knockdown in murine hearts made no alteration to BP (Figure 2M). Collectively, we demonstrate that GDF6 knockdown aggravates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction.

Figure 2.

GDF6 knockdown aggravates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction. (A) GDF6 protein levels in murine hearts with AAV9-shCtrl or AAV9-shGdf6 injection. (B) Heart rate in sham- or TAC-operated mice with AAV9-shCtrl or AAV9-shGdf6 injection. (C,D) Left ventricle internal diameter at end-diastole (LVEDd), left ventricle internal diameter at end-systole (LVEDs), and fractional shortening (FS). (E) Interventricular septal thickness at end-diastole (IVSd) and interventricular septal thickness at end-systole (IVSs). (F,G) Hematoxylin–eosin staining of murine hearts and quantification of cross-sectional area (CSA). (H,I) Quantification of heart weight/tibia length (HW/TL) and lung weight/tibia length (LW/TL) ratios. (J,K) Nppa, Nppb, Myh7, and Myh6 mRNA levels in murine hearts. (L) The levels of inflammatory cytokines in the myocardium. (M) BP levels. n = 6 per group. * p < 0.05 versus matched sham mice receiving AAV9-shCtrl injection, # p < 0.05 versus matched TAC mice receiving AAV9-shCtrl injection. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test was applied. In (A), Student’s two-tailed t-test was performed.

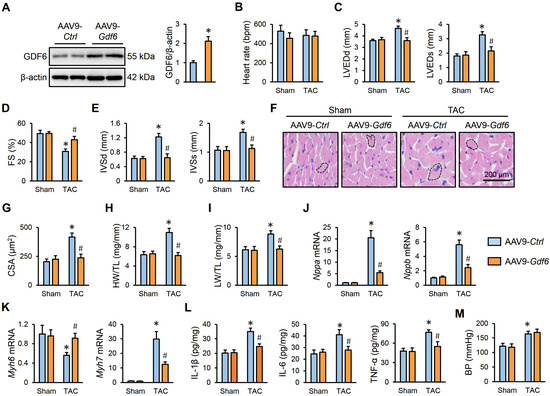

3.3. GDF6 Overexpression Attenuates Pressure Overload-Induced Cardiac Hypertrophy, Inflammation and Dysfunction

Then, mice were intravenously injected with AAV9-Gdf6 to specifically overexpress GDF6 in murine hearts, and the efficiency was verified by Western blot (Figure 3A). As shown in Figure 3B–D, GDF6 overexpression did not affect the heart rate, but significantly attenuated TAC-induced cardiac dilation and dysfunction in mice, as evidenced by decreased LVEDd, LVEDs, and FS. Echocardiographic analysis also determined significant decreases in the IVSd and IVSs in GDF6-overexpressed hearts, which indicates an improved cardiac hypertrophy (Figure 3E). Consistently, hematoxylin–eosin staining revealed that GDF6 overexpression delayed the hypertrophic growth of cardiomyocytes in response to pressure overload (Figure 3F,G). Meanwhile, we also detected decreases in HW/TL and LW/TL in mice with AAV9-Gdf6 injection, which indicates an improved cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction (Figure 3H,I). And the dysregulated mRNA expressions of hypertrophic markers were also restored by GDF6 overexpression (Figure 3J,K). Meanwhile, we found that the increased levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in TAC-induced hearts were dramatically inhibited by GDF6 overexpression (Figure 3L). In addition, we found that GDF6 overexpression in murine hearts also made no alteration to BP (Figure 3M). Taken together, our data reveal that GDF6 overexpression attenuates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction.

Figure 3.

GDF6 overexpression attenuates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction. (A) GDF6 protein levels in murine hearts injected with AAV9-Ctrl or AAV9-Gdf6. (B) Heart rate in sham- or TAC-operated mice with AAV9-Ctrl or AAV9-Gdf6 injection. (C,D) LVEDd, LVEDs, and FS. (E) IVSd and IVSs. (F,G) Hematoxylin–eosin staining of murine hearts and quantification of CSA. (H,I) Quantification of HW/TL and LW/TL. (J,K) Nppa, Nppb, Myh7, and Myh6 mRNA levels in murine hearts. (L) The levels of inflammatory cytokines in the myocardium. (M) BP levels. n = 6 per group. * p < 0.05 versus matched sham mice receiving AAV9-Ctrl injection, # p < 0.05 versus matched TAC mice receiving AAV9-Ctrl injection. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test was applied. In (A), Student’s two-tailed t-test was performed.

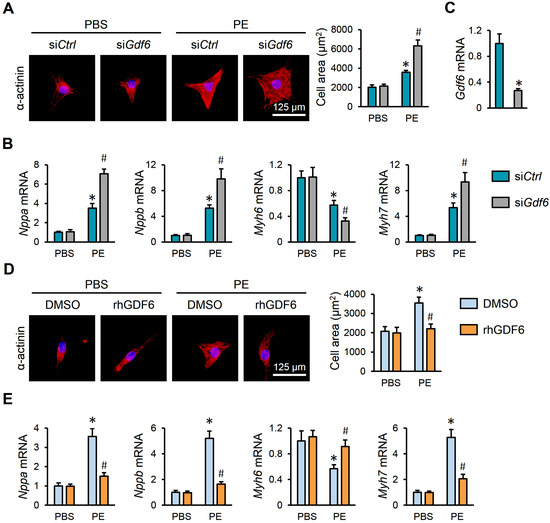

3.4. GDF6 Prevents PE-Induced Hypertrophic Growth of NRVMs

Additionally, NRVMs were isolated and stimulated with PE to further evaluate the role of GDF6 in vitro. As shown in Figure 4A, GDF6 knockdown significantly aggravated PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs. Meanwhile, the dysregulated mRNA levels of hypertrophic markers were further disarranged by GDF6 knockdown (Figure 4B,C). In contrast, supplementation with rhGDF6 significantly prevented PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs, as evidenced by a decreased cell area, decreased Nppa, Nppb, and Myh7 mRNA levels, and an increased Myh6 mRNA level (Figure 4D,E). These results suggest that GDF6 prevents PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs.

Figure 4.

GDF6 prevents PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of α-actinin and quantification of cell area in NRVMs with or without GDF6 knockdown. (B) Nppa, Nppb, Myh7, and Myh6 mRNA levels in NRVMs with or without GDF6 knockdown. (C) GDF6 mRNA levels in NRVMs with or without GDF6 knockdown. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of α-actinin and quantification of cell area in NRVMs with or without recombinant human GDF6 (rhGDF6) treatment. (E) Nppa, Nppb, Myh7, and Myh6 mRNA levels in NRVMs with or without rhGDF6 treatment. n = 6 per group. * p < 0.05 versus matched PBS NRVMs receiving siCtrl or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) treatment, # p < 0.05 versus matched PE NRVMs receiving siCtrl or DMSO treatment. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test was applied. In (C), Student’s two-tailed t-test was performed.

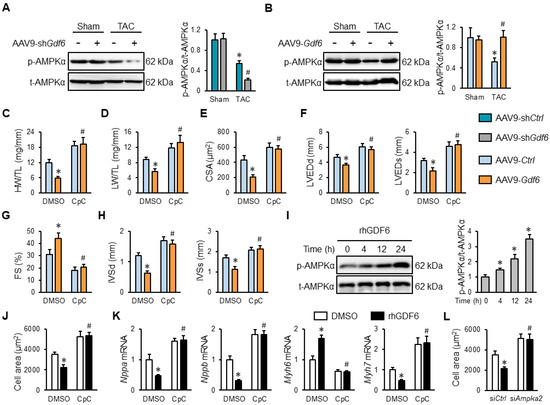

3.5. GDF6 Ameliorates Cardiac Hypertrophy Through Activating AMPKα In Vivo and In Vitro

AMPKα is an attractive molecular target to treat cardiac hypertrophy, and we herein investigated whether it was required for GDF6-mediated protection against cardiac hypertrophy [14]. As shown in Figure 5A,B, GDF6 knockdown decreased, while GDF6 overexpression increased, the AMPKα phosphorylation in hypertrophic hearts. To further validate the necessity of AMPKα, mice in TAC groups were intraperitoneally injected with 20 mg/kg CpC every other day from 2 weeks after TAC surgery to inhibit AMPKα [25]. As shown in Figure 5C,D, the inhibitory effects of GDF6 on the HW/TL and LW/TL ratios in TAC mice were completely blocked by CpC. And GDF6 overexpression also failed to prevent TAC-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in the presence of CpC, as evidenced by increased CSA (Figure 5E). Meanwhile, echocardiographic analysis also revealed that CpC treatment significantly blocked GDF6 overexpression-mediated protective effects against ventricular hypertrophy, dilation, and dysfunction, as evidenced by decreased FS and increased LVEDd, LVEDs, IVSd, and IVSs (Figure 5F–H). In addition, we also found that rhGDF6 activated AMPKα in a time-dependent manner (Figure 5I). Consistent with the in vivo findings, we demonstrated that rhGDF6-mediated inhibitory effects against PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs were also prevented by CpC treatment in vitro (Figure 5J,K). Moreover, AMPKα knockdown also prevented the inhibitory effects of rhGDF6 in PE-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, as evidenced by the increased cell area (Figure 5L). Our study implies that GDF6 ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy through activating AMPKα in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 5.

GDF6 ameliorates cardiac hypertrophy through activating 5′-adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase α (AMPKα) in vivo and in vitro. (A) AMPKα protein levels in sham- or TAC-operated murine hearts with AAV9-shCtrl or AAV9-shGdf6 injection. (B) AMPKα protein levels in sham- or TAC-operated murine hearts with AAV9-Ctrl or AAV9-Gdf6 injection. (C,D) HW/TL and LW/TL in TAC-operated mice injected with AAV9-shCtrl or AAV9-shGdf6 in the presence or absence of compound C (CpC). (E) Quantification of CSA. (F,G) FS, LVEDd, and LVEDs. (H) IVSd and IVSs. (I) AMPKα protein levels in rhGDF6-treated NRVMs at different time points. (J) Quantification of cell area in PE-stimulated NRVMs with or without rhGDF6 treatment in the presence or absence of CpC. (K) Nppa, Nppb, Myh7, and Myh6 mRNA levels in NRVMs. (L) Quantification of cell area in PE-stimulated NRVMs with or without rhGDF6 treatment in the presence or absence of siAmpka2 transfection. n = 6 per group. * p < 0.05 versus matched AAV9-Ctrl-injected TAC mice receiving DMSO treatment, # p < 0.05 versus matched AAV9-Gdf6-injected TAC mice receiving DMSO treatment. In (A,B), * p < 0.05 versus matched sham mice receiving AAV9-shCtrl or AAV9-Ctrl injection, # p < 0.05 versus matched TAC mice receiving AAV9-shCtrl or AAV9-Ctrl injection. In (I,J), * p < 0.05 versus matched DMSO-stimulated NRVMs under PE incubation, # p < 0.05 versus matched DMSO-stimulated NRVMs with rhGDF6 treatment under PE incubation. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test was applied.

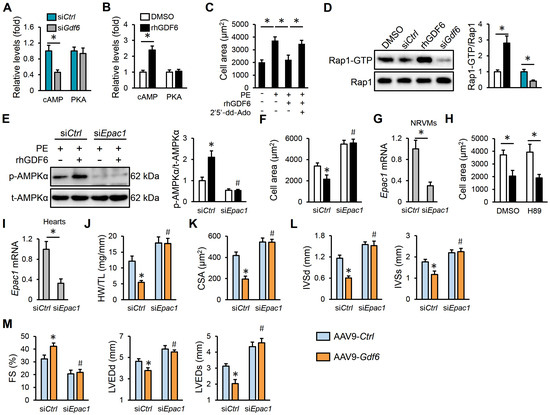

3.6. GDF6 Activates AMPKα Through cAMP/Epac1 Pathway

Finally, we explored the precise mechanism through which GDF6 activated AMPKα. The cAMP is a critical secondary messenger in transducing extracellular stimuli to intracellular signaling network, and acts as a classic upstream activator of AMPKα in a PKA-dependent manner [47]. As shown in Figure 6A,B, GDF6 knockdown decreased, while rhGDF6 treatment increased, intracellular cAMP levels in PE-stimulated NRVMs, without affecting PKA activities. However, the protective effects of rhGDF6 against PE-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy were prevented by 2′5′-dd-Ado, an AC inhibitor that reduces cAMP generation (Figure 6C). In addition to PKA, Epac1, the other downstream effector of cAMP, is a well-known activator of AMPKα [48,49]. We found that Epac1 was activated by rhGDF6, but inhibited by GDF6 knockdown, as evidenced by the downstream Rap1-GTP levels (Figure 6D). As shown in Figure 6E, Epac1 silence completely abolished rhGDF6-mediated AMPKα activation under PE stimulation. As expected, the anti-hypertrophic effects of rhGDF6 were also blocked in PE-treated NRVMs with Epac1 silence (Figure 6F,G). As expected, PKA inhibition did not affect the anti-hypertrophic effects of rhGDF6 in vitro (Figure 6H). To further validate the role of Epac in vivo, TAC mice were delivered with chemically modified siEpac1 using a Nanoparticle In Vivo Transfection Reagent from 2 weeks after TAC surgery, and the efficiency was validated by quantitative real-time PCR (Figure 6I). Consistent with the in vitro findings, Epac1 silence also blocked the anti-hypertrophic effects of GDF6 in mice, as evidenced by an increased HW/TL, CSA, IVSd, and IVSs (Figure 6J–L). Meanwhile, the improved cardiac dilation and dysfunction in GDF6-overexpressed hypertrophic hearts were also abolished by Epac1 silence (Figure 6M). Overall, our results reveal that GDF6 activates AMPKα through the cAMP/Epac1 pathway.

Figure 6.

GDF6 activates AMPKα through cyclic AMP/exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 1 (cAMP/Epac1) pathway. (A) The levels of cAMP and protein kinase A (PKA) activity in PE-stimulated NRVMs with or without GDF6 knockdown. (B) The levels of cAMP and PKA activity in PE-stimulated NRVMs with or without rhGDF6 treatment. (C) Quantification of cell area in rhGDF6-treated NRVMs with or without adenylyl cyclase (AC) inhibition. (D) Rap1-GTP and total Rap1 protein levels in PE-stimulated NRVMs treated with siGdf6 or rhGDF6. (E) AMPKα protein levels in PE-stimulated NRVMs with or without Epac1 silence in the presence or absence of rhGDF6. (F) Quantification of cell area. (G) Epac1 mRNA levels in NRVMs with or without Epac1 silence. (H) Quantification of cell area. (I) Epac1 mRNA levels in murine hearts with or without Epac1 silence. (J) HW/TL in TAC mice with or without Epac1 silence in the presence or absence of AAV9-Gdf6. (K) Quantification of CSA. (L) IVSd and IVSs. (M) FS, LVEDd, and LVEDs. n = 6 per group. * p < 0.05 versus matched AAV9-Ctrl-injected TAC mice receiving siCtrl injection, # p < 0.05 versus matched AAV9-Gdf6-injected TAC mice receiving siCtrl injection. In (A–D,G–I), * p < 0.05 versus the matched groups. In (E,F), * p < 0.05 versus matched siCtrl-transfected NRVMs with DMSO treatment under PE incubation, # p < 0.05 versus matched siCtrl-transfected NRVMs with rhGDF6 treatment under PE incubation. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey post hoc test was applied. In (A,B,D,G–I), Student’s two-tailed t-test was performed.

4. Discussion

Cardiac hypertrophy initially occurs as an adaptive response to maintain normal cardiac function and output under various pathological stimuli, which eventually predisposes to the occurrence of heart failure [1,2]. Generally, hypertension acts as the major contributor of hypertrophic growth of the heart, and TAC-induced pressure overload-associated cardiac hypertrophy is a well-accepted pathological model to investigate the molecular basis of cardiac hypertrophy [2]. In the present study, we established TAC-induced cardiac hypertrophy in mice and PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs, and detected an elevated GDF6 expression in murine hearts and NRVMs under hypertrophic stimuli. GDF6 knockdown aggravated, while GDF6 overexpression attenuated, pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in vivo. Meanwhile, we found that GDF6 also prevented PE-induced hypertrophic growth of NRVMs in vitro. Mechanistically, GDF6 activated AMPKα to exert the cardioprotective effects, and AMPKα inhibition significantly blocked the anti-hypertrophic effects of GDF6. Further studies showed that GDF6 activated AMPKα through the cAMP/Epac1 pathway, and that Epac1 knockdown abolished the protective effects of GDF6 against TAC- or PE-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo and in vitro. In general, our findings, for the first time, define GDF6 as a negative regulator cardiac hypertrophy and show that supplementation of GDF6 may be of great therapeutic interest for heart failure.

The regulation of cardiac hypertrophy is orchestrated by complex signaling cascades (e.g., PI3K/AKT, MAPKs, and CaN/NFATs), and targeting these pathways provides significant cardioprotections against hypertrophic growth of the heart [1]. Inflammation is also implicated in the pathogenesis of hypertrophic growth of the heart. AMPKα emerges as an attractive and effective molecular node to reduce inflammation and maintain cardiac homeostasis under different pathological stimuli. Zhang et al. previously found that AMPKα activation blocked the transdifferentiation and collagen synthesis of cardiac fibroblasts, leading to an improved fibrotic remodeling and cardiac dysfunction [41]. And Hu et al. recently also demonstrated that AMPKα activation inhibited aging-related inflammation, oxidative stress, and cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction [48]. In addition, AMPKα activation also prevented cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction. Li et al. reported that AMPKα activation stimulated autophagy and significantly blocked PE-induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [50]. Further, AMPKα activation also reduced protein O-GlcNAcylation and then counteracted cardiac hypertrophy [51]. Moreover, Nam et al. demonstrated that transient AMPKα activation before pressure overload could also effectively prevent adverse remodeling and cardiac dysfunction in mice [52]. In contrast, Myers et al. showed that treatment with a potent, direct, and allosteric activator of AMPKα, MK-8722, significantly improved glucose homeostasis but induced cardiac hypertrophy across species [53]. Therefore, it is of great therapeutic interest to find novel and specific activators of AMPKα for the treatment of cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction, especially endogenous activators. In this study, we observed a significant upregulation of GDF6 in hypertrophic hearts and NRVMs, and that GDF6 overexpression or supplementation effectively blocked TAC- or PE-induced cardiac hypertrophy in vivo and in vitro. AMPKα acts as a sensor of cellular energy status and is activated by increases in the cellular AMP/ATP ratio under metabolic stresses. Commonly, AMPKα is directly activated by the known upstream kinases, including LKB1 and CaMKKβ. GDF6 is a secretory factor, and transduces extracellular stimuli to the intracellular molecular network through membrane receptors and secondary messengers. cAMP is an important second messenger and upstream activator of AMPKα [47]. Roth et al. demonstrated that restoring the cAMP-generating capacity could improve cardiac hypertrophy and dysfunction in mice [54]. In addition, cardiomyocyte-secreted cAMP could be converted into its metabolite adenosine and then reduce cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis through adenosine receptors [55]. In contrast, other studies argued that cAMP could facilitate cardiac hypertrophy, and this discrepancy could be attributable to its different source [56,57]. Interestingly, previous studies have shown that the precise role of cAMP depends on where it is made. Different receptors producing spatially segregated pools of cAMP in discrete subcellular locations do not move freely throughout the cell, and subsequently trigger compartmentalized signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes [58,59]. Accordingly, β1-adrenergic receptor (AR) enhanced PKA-dependent phosphorylation of multiple target proteins, including L-type Ca2+ channels (LTCCs) and phospholamban; however, β2AR induces a cAMP-dependent response limited to LTCCs regulation [60]. PKA is a well-known downstream effector of cAMP and contributes to the progression of cardiac hypertrophy [61]. Interestingly, we found no alteration of PKA activity in PE-stimulated NRVMs with either GDF6 knockdown or rhGDF6 treatment. Instead, Epac1, the other target of cAMP, was required for the activation of AMPKα by GDF6. Consistently, Laurent et al. determined that stimulating Epac1 activated AMPKα-dependent autophagy, thereby preventing cardiomyocyte hypertrophy [62]. Herein, we observed that Epac1 silence abolished GDF6-mediated AMPKα activation and anti-hypertrophic effects in vivo and in vitro. Currently, no definite receptors for GDF6 have been identified. GDF6 belongs to the transforming growth factor-β superfamily, and potential receptors for GDFs have been identified, such as glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor receptor alpha-like, bone morphogenetic protein receptors, epidermal growth factor receptor, platelet-derived growth factor receptor, etc. In our study, we found that reducing cAMP generation with the AC inhibitor dramatically abolished the anti-hypertrophic role of rhGDF6, which indicates the potential involvement of G protein-coupled receptors in GDF6. Further studies are needed to identify the specific receptors for GDF6. Based on these findings, we propose that cAMP generated by the specific receptor for GDF6 induces a biased activation of the Epac1/AMPKα pathway.

In our study, neither GDF6 overexpression nor GDF6 knockdown affected cardiac morphology or function at basal conditions, which indicated that GDF6 manipulation did not induce any significant side effects. Meanwhile, treatment with recombinant human GDF6 also did not affect the cell morphology or viability in rat cardiomyocytes. These in vivo and in vitro data identified the safety of GDF6 manipulation for the treatment of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. For the possible off-target effects from systemic GDF6 administration, gene therapy with viral or non-viral vectors can be used in future studies. Of note, there are some limitations of the present study. First, the specific molecular mechanisms mediating GDF6 upregulation by ROS remain unclear. Second, whether GDF6 expressed by other cardiac cells also prevents pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure should be determined in further studies. Third, the precise receptor for GDF6 and the downstream compartmentalized cAMP signaling pathways in cardiomyocytes are elusive.

In general, our findings, for the first time, define GDF6 as a negative regulator of cardiac hypertrophy and show that supplementation of GDF6 with viral/non-viral vectors or systemic administration with nanoparticles may be of great therapeutic interest for heart failure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.R., W.R. and Z.W.; methodology, Q.R. and W.R.; software, Q.R. and W.R.; validation, Q.R., W.R. and Z.W.; formal analysis, Q.R., W.R. and Z.W.; investigation, Z.W.; resources, Q.R. and W.R.; data curation, Q.R. and W.R.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.R., W.R. and Z.W.; writing—review and editing, Q.R., W.R. and Z.W.; visualization, Q.R., W.R. and Z.W.; supervision, Q.R., W.R. and Z.W.; project administration, Q.R.; funding acquisition, Z.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 82300539).

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal procedures performed in this study were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (Approval Code: WDRY20201107, approved on 7 November 2020) and were in compliance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Heineke, J.; Molkentin, J.D. Regulation of cardiac hypertrophy by intracellular signalling pathways. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2006, 7, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.Y.; Zhang, Y.L.; Bai, J.; Liu, J.Q.; Li, H.H. VEGF-C/VEGFR-3 axis protects against pressure-overload induced cardiac dysfunction through regulation of lymphangiogenesis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, S.; Ke, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Chang, W. Lutein attenuates angiotensin II- induced cardiac remodeling by inhibiting AP-1/IL-11 signaling. Redox Biol. 2021, 44, 102020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Xu, S.; Huo, Y.; Sun, D.; Hu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Wang, P.; Li, Z.; Liang, M.; et al. Sorting nexin 3 induces heart failure via promoting retromer-dependent nuclear trafficking of STAT3. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2871–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Guo, Z.; Lan, R.; Cai, S.; Lin, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Liu, P. The poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation of BRD4 mediated by PARP1 promoted pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 1286–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, C.; Zhang, N.; Wei, W.Y.; Li, L.L.; Wu, H.M.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. Matrine attenuates pathological cardiac fibrosis via RPS5/p38 in mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2021, 42, 573–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Zhu, M.; Yin, R.; Dai, L.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J. Baicalin Mitigates Cardiac Hypertrophy and Fibrosis by Inhibiting the p85a Subunit of PI3K. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, H.; Wu, M.; Xie, H.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Duan, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Liao, W.; Chen, Y. Fas Apoptosis Inhibitory Molecule 2 Inhibits Pathological Cardiac Hypertrophy by Regulating the MAPK Signaling Pathway. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e34257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, R.; Lin, J.; Ma, Q.; Guo, H.; Huang, H.; Liang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Therapeutic Inhibition of LincRNA-p21 Protects Against Cardiac Hypertrophy. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 434–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, X.S.; Cong, X.X.; Gao, X.K.; Shi, Y.P.; Shi, L.J.; Wang, J.F.; Ni, C.Y.; He, M.J.; Xu, Y.; Yi, C.; et al. AMPK-mediated phosphorylation enhances the auto-inhibition of TBC1D17 to promote Rab5-dependent glucose uptake. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 3214–3234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Tsai, H.I.; Liu, Y.; Gao, J.; Wang, M.; Song, L.; Cao, X.; Xu, Z.; Chen, H.; et al. Branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase 2 regulates ferroptotic cell death in cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 1222–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Wei, W.; Zhang, N.; Wu, H.; Ma, Z.; Li, L.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q. Matrine attenuates oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via maintaining AMPKα/UCP2 pathway. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2019, 9, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuck, B.J.; Lenski, M.; Bohm, M.; Laufs, U. Metabolic switch and hypertrophy of cardiomyocytes following treatment with angiotensin II are prevented by AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 32562–32569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Hu, X.; Xu, X.; Fassett, J.; Zhu, G.; Viollet, B.; Xu, W.; Wiczer, B.; Bernlohr, D.A.; Bache, R.J.; et al. AMP activated protein kinase-α2 deficiency exacerbates pressure-overload-induced left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction in mice. Hypertension 2008, 52, 918–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Gao, L.; Zhang, D.; Yao, R.; Huang, Z.; Du, B.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, L.; Li, P.; Li, Y.; et al. C1QTNF1 attenuates angiotensin II-induced cardiac hypertrophy via activation of the AMPKα pathway. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2018, 121, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Han, X.; Yu, T.; Wang, M.; Luo, W.; Zou, C.; Li, X.; Li, G.; Wu, G.; Wang, Y.; et al. OTUD1 promotes pathological cardiac remodeling and heart failure by targeting STAT3 in cardiomyocytes. Theranostics 2023, 13, 2263–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rider, C.C.; Mulloy, B. Bone morphogenetic protein and growth differentiation factor cytokine families and their protein antagonists. Biochem. J. 2010, 429, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai-Coakwell, M.; March, L.; Dai, X.H.; Duval, M.; Lopez, I.; French, C.R.; Famulski, J.; De Baere, E.; Francis, P.J.; Sundaresan, P.; et al. Contribution of growth differentiation factor 6-dependent cell survival to early-onset retinal dystrophies. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2013, 22, 1432–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, C.B.; Trevelin, S.C.; Richards, D.A.; Santos, C.; Sawyer, G.; Markovinovic, A.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, M.; Brewer, A.C.; Yin, X.; et al. Fibroblast Nox2 (NADPH Oxidase-2) Regulates ANG II (Angiotensin II)-Induced Vascular Remodeling and Hypertension via Paracrine Signaling to Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscl. Throm. Vas. 2021, 41, 698–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wei, H.; Tan, J.; Chen, H.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Y. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 9 and 13 Induce C3H10T1/2 Cell Differentiation to Cardiomyocyte-Like Cells In Vitro. Cell Transplant. 2015, 24, 909–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Hu, W.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Xiao, C.; Fan, L.; Zhong, Z.; Chen, X.; Lv, K.; et al. A Novel Human Long Noncoding RNA SCDAL Promotes Angiogenesis through SNF5-Mediated GDF6 Expression. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2004629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.X.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, X.J.; Zhao, Y.C.; Deng, K.Q.; Jiang, X.; Wang, P.X.; Huang, Z.; Li, H. The ubiquitin E3 ligase TRAF6 exacerbates pathological cardiac hypertrophy via TAK1-dependent signalling. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, C.; Kong, C.Y.; Song, P.; Wu, H.M.; Xu, S.C.; Yuan, Y.P.; Deng, W.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. FNDC5 alleviates oxidative stress and cardiomyocyte apoptosis in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activating AKT. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 540–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, C.; Yuan, X.P.; Yuan, Y.P.; Song, P.; Kong, C.Y.; Teng, T.; Hu, M.; Xu, S.C.; Ma, Z.G.; et al. Osteocrin, a novel myokine, prevents diabetic cardiomyopathy via restoring proteasomal activity. Cell Death Dis. 2021, 12, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.G.; Dai, J.; Zhang, W.B.; Yuan, Y.; Liao, H.H.; Zhang, N.; Bian, Z.Y.; Tang, Q.Z. Protection against cardiac hypertrophy by geniposide involves the GLP-1 receptor/AMPKα signalling pathway. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 1502–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.J.; Ji, Y.X.; Zhang, P.; Deng, K.Q.; Gong, J.; Ren, S.; Wang, X.; Chen, I.; Wang, H.; et al. The long noncoding RNA Chaer defines an epigenetic checkpoint in cardiac hypertrophy. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncalves, L.S.; Sales, L.P.; Saito, T.R.; Campos, J.C.; Fernandes, A.L.; Natali, J.; Jensen, L.; Arnold, A.; Ramalho, L.; Bechara, L.; et al. Histidine dipeptides are key regulators of excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac muscle: Evidence from a novel CARNS1 knockout rat model. Redox Biol. 2021, 44, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Hu, C.; Yuan, Y.P.; Song, P.; Kong, C.Y.; Wu, H.M.; Xu, S.C.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. Endothelial ERG alleviates cardiac fibrosis via blocking endothelin-1-dependent paracrine mechanism. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2021, 37, 873–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, J.A.; Zhang, H.; Lin, H.; Gao, L.; Zhang, H.L.; Zhang, J.F.; Wang, C.Q.; Gu, J. Irisin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiac perivascular fibrosis through inhibiting endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition by regulating ROS accumulation and autophagy disorder in endothelial cells. Redox Biol. 2021, 46, 102120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Song, J.; Zhu, Z.; Peng, H.; Ding, X.; Yang, F.; Li, K.; Yu, X.; Yang, G.; Tao, Y.; et al. Compensatory role of endogenous sulfur dioxide in nitric oxide deficiency-induced hypertension. Redox Biol. 2021, 48, 102192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Pang, W.; Hou, L.; Liang, Y.; Han, X.; Luo, X.; Wang, P.; Zhang, X.; Li, L.; et al. YTHDC1-mediated augmentation of miR-30d in repressing pancreatic tumorigenesis via attenuation of RUNX1-induced transcriptional activation of Warburg effect. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 3105–3124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, W.; Qu, H.; Zhang, J.; Thongkum, A.; Dinh, T.N.; Kappeler, K.V.; Chen, Q.M. Far Upstream Binding Protein 1 (FUBP1) participates in translational regulation of Nrf2 protein under oxidative stress. Redox Biol. 2021, 41, 101906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, A.; Liang, Q.; Yang, X.; Dong, Q.; Fu, M.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; Ye, Y.; Lan, Z.; et al. Spermidine inhibits vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease through modulation of SIRT1 signaling pathway. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cao, Y.; Liu, C.; Wu, Z.; Shen, J.; Lu, J.; Liu, P. Isorhapontigenin protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via increasing YAP1 expression. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 680–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; Jiang, Z.; Gu, P.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; You, R.; Ba, Q.; et al. Rebalancing TGF-β/Smad7 signaling via Compound kushen injection in hepatic stellate cells protects against liver fibrosis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soriano-Arroquia, A.; Gostage, J.; Xia, Q.; Bardell, D.; McCormick, R.; McCloskey, E.; Bellantuono, I.; Clegg, P.; McDonagh, B.; Goljanek-Whysall, K. miR-24 and its target gene Prdx6 regulate viability and senescence of myogenic progenitors during aging. Aging Cell 2021, 20, e13475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Wei, W.Y.; Li, L.L.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. Osteocrin attenuates inflammation, oxidative stress, apoptosis, and cardiac dysfunction in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Clin. Transl. Med. 2020, 10, e124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Wahlang, B.; Thapa, M.; Head, K.Z.; Hardesty, J.E.; Srivastava, S.; Merchant, M.L.; Rai, S.N.; Prough, R.A.; Cave, M.C. Proteomics and metabolic phenotyping define principal roles for the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in mouse liver. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3806–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, H.; Bai, Q.; Yang, X.; Akakpo, J.Y.; Ji, L.; Yang, L.; Rulicke, T.; Zatloukal, K.; Jaeschke, H.; Ni, H.M.; et al. Dual roles of p62/SQSTM1 in the injury and recovery phases of acetaminophen-induced liver injury in mice. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 3791–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Xing, Y.; Liu, J.; Dong, D.; Liu, Y.; Qiao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, L. Lonicerin targets EZH2 to alleviate ulcerative colitis by autophagy-mediated NLRP3 inflammasome inactivation. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2021, 11, 2880–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, Z.G.; Yuan, Y.P.; Xu, S.C.; Wei, W.Y.; Song, P.; Kong, C.Y.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.Z. Rosmarinic acid attenuates cardiac fibrosis following long-term pressure overload via AMPKα/Smad3 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.L.; Zhao, K.C.; Yuan, W.; Zhou, F.; Song, H.Y.; Liu, G.L.; Huang, J.; Zou, J.J.; Zhao, B.; Xie, S.P. MicroRNA-31-5p Exacerbates Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Acute Lung Injury via Inactivating Cab39/AMPKα Pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 8822361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.X.; Ma, Z.G.; Wu, H.M.; Xu, S.C.; Song, P.; Kong, C.Y.; Yuan, Y.P.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.Z. Rosmarinic acid alleviates cardiomyocyte apoptosis via cardiac fibroblast in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2019, 15, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Song, C.; Lei, Y.; Xu, J.; Zhang, G.; Wang, W.; Song, G. Deubiquitinase USP39 and E3 ligase TRIM26 balance the level of ZEB1 ubiquitination and thereby determine the progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Death Differ. 2021, 28, 2315–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, D.; He, Z.; Fedorova, J.; Zhang, J.; Wood, E.; Zhang, X.; Kang, D.E.; Li, J. Sestrin2 maintains OXPHOS integrity to modulate cardiac substrate metabolism during ischemia and reperfusion. Redox Biol. 2021, 38, 101824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Song, P.; Yuan, Y.P.; Kong, C.Y.; Wu, H.M.; Xu, S.C.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. Meteorin-like protein attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activating cAMP/PKA/SIRT1 pathway. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, S.P.; Reoma, J.L.; Gamm, D.M.; Uhler, M.D. LKB1, a novel serine/threonine protein kinase and potential tumour suppressor, is phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and prenylated in vivo. Biochem. J. 2000, 345 Pt 3, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Zhang, X.; Hu, M.; Teng, T.; Yuan, Y.P.; Song, P.; Kong, C.Y.; Xu, S.C.; Ma, Z.G.; Tang, Q.Z. Fibronectin type III domain-containing 5 improves aging-related cardiac dysfunction in mice. Aging Cell 2022, 21, e13556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Arias, I.M. Bile acid stimulates hepatocyte polarization through a cAMP-Epac-MEK-LKB1-AMPK pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 1403–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Yao, F.; Su, Q.; Liu, D.; Xue, R.; Dai, G.; Fang, R.; Zeng, J.; Chen, Y.; et al. AMPK inhibits cardiac hypertrophy by promoting autophagy via mTORC1. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 558, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelinas, R.; Mailleux, F.; Dontaine, J.; Bultot, L.; Demeulder, B.; Ginion, A.; Daskalopoulos, E.P.; Esfahani, H.; Dubois-Deruy, E.; Lauzier, B.; et al. AMPK activation counteracts cardiac hypertrophy by reducing O-GlcNAcylation. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nam, D.H.; Kim, E.; Benham, A.; Park, H.K.; Soibam, B.; Taffet, G.E.; Kaelber, J.T.; Suh, J.H.; Taegtmeyer, H.; Entman, M.L.; et al. Transient activation of AMPK preceding left ventricular pressure overload reduces adverse remodeling and preserves left ventricular function. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, R.W.; Guan, H.P.; Ehrhart, J.; Petrov, A.; Prahalada, S.; Tozzo, E.; Yang, X.; Kurtz, M.M.; Trujillo, M.; Gonzalez, T.D.; et al. Systemic pan-AMPK activator MK-8722 improves glucose homeostasis but induces cardiac hypertrophy. Science 2017, 357, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roth, D.M.; Bayat, H.; Drumm, J.D.; Gao, M.H.; Swaney, J.S.; Ander, A.; Hammond, H.K. Adenylyl cyclase increases survival in cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2002, 105, 1989–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, Y.; Ahles, A.; Truong, D.J.; Baqi, Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Husse, B.; Hulot, J.S.; Foinquinos, A.; Thum, T.; Muller, C.E.; et al. Cardiac myocyte-secreted cAMP exerts paracrine action via adenosine receptor activation. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 5385–5397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Robinson, J.; Wang-Hu, J.; Jiang, L.; Freeman, D.A.; Rivkees, S.A.; Wendler, C.C. cAMP induces hypertrophy and alters DNA methylation in HL-1 cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol.-Cell Physiol. 2015, 309, C425–C436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoccarato, A.; Surdo, N.C.; Aronsen, J.M.; Fields, L.A.; Mancuso, L.; Dodoni, G.; Stangherlin, A.; Livie, C.; Jiang, H.; Sin, Y.Y.; et al. Cardiac Hypertrophy Is Inhibited by a Local Pool of cAMP Regulated by Phosphodiesterase 2. Circ. Res. 2015, 117, 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.R.; Sherpa, R.T.; Moshal, K.S.; Harvey, R.D. Compartmentalized cAMP signaling in cardiac ventricular myocytes. Cell Signal. 2022, 89, 110172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischmeister, R. Is cAMP good or bad? Depends on where it’s made. Circ. Res. 2006, 98, 582–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuschel, M.; Zhou, Y.Y.; Spurgeon, H.A.; Bartel, S.; Karczewski, P.; Zhang, S.J.; Krause, E.G.; Lakatta, E.G.; Xiao, R.P. β2-Adrenergic cAMP signaling is uncoupled from phosphorylation of cytoplasmic proteins in canine heart. Circulation 1999, 99, 2458–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, C.W.; Stelzer, J.E.; Greaser, M.L.; Powers, P.A.; Moss, R.L. Acceleration of crossbridge kinetics by protein kinase A phosphorylation of cardiac myosin binding protein C modulates cardiac function. Circ. Res. 2008, 103, 974–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, A.C.; Bisserier, M.; Lucas, A.; Tortosa, F.; Roumieux, M.; De Regibus, A.; Swiader, A.; Sainte-Marie, Y.; Heymes, C.; Vindis, C.; et al. Exchange protein directly activated by cAMP 1 promotes autophagy during cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015, 105, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).