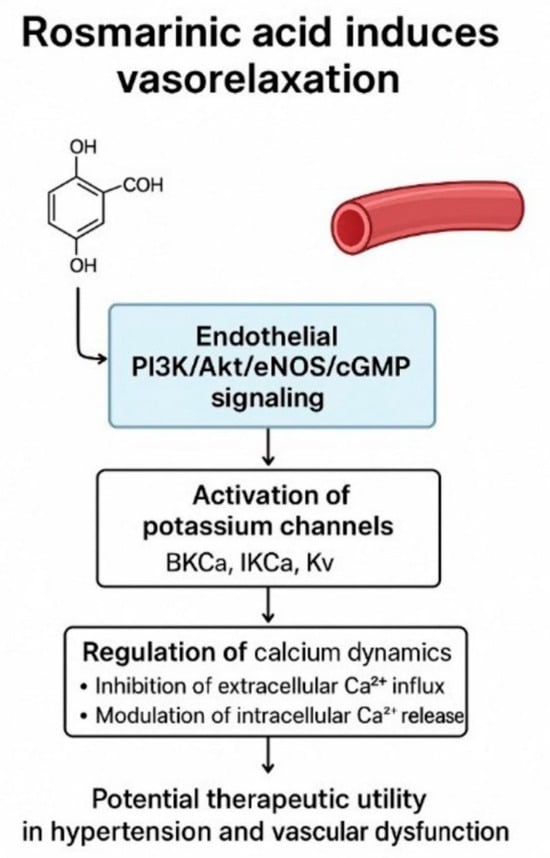

Rosmarinic Acid Induces Vasorelaxation via Endothelium-Dependent, Potassium Channel-Related, and Calcium-Modulated Pathways: Evidence from Rat Aortic Rings

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval and Experimental Animals

2.2. General Study Design and Experimental Protocol

2.3. Investigation of the Roles of Endothelium-Dependent Pathways, Other Possible Mechanisms, and Potassium Channels in RA-Induced Vasorelaxation

2.4. Investigating the Role of Extracellular Calcium Sources in RA-Induced Vasorelaxation

2.5. Investigating the Role of Intracellular Calcium Sources in RA-Induced Vasorelaxation

2.6. Investigating the Role of the PKC Signaling Pathway in RA-Induced Vasorelaxation

2.7. Investigation of the Effect of RA on Ang II-Induced Vasorelaxation

2.8. Drugs

2.9. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. RA-Induced Vasorelaxation in Rat Thoracic Aorta

3.2. Roles of Endothelium-Dependent Mechanisms in RA-Induced Vasorelaxation

3.3. Contributions of Other Potential Signaling Pathways to RA-Induced Vasorelaxation

3.4. Contribution of Potassium Channel Activation to RA-Induced Vasorelaxation

3.5. Role of Extracellular Calcium Sources

3.6. Role of Intracellular Calcium Sources

3.7. Role of the PKC Signaling Pathway

3.8. Role of the Renin-Angiotensin System

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. In Global Report on Hypertension: The Race Against a Silent Killer; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K.T.; Stefanescu, A.; He, J. The global epidemiology of hypertension. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2020, 16, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, R.; An, J.; Bellows, B.K.; Moran, A.E.; Zhang, Y. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control among US young adults, 2003–2023. Am. J. Hypertens. 2025, 38, 551–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryar, C.D.; Kit, B.; Carroll, M.D.; Afful, J. Hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control among adults age 18 and older: United States, August 2021–August 2023. NCHS Data Brief 2024, 511, CS354233. [Google Scholar]

- Prabha, C.; Bera, O.P.; Mantri, N.; Kaushal, R.; Goel, A.D.; Gupta, M.K.; Charan, J.; Joshi, N.; Bhardwaj, P. National prevalence and regional variation in the burden of hypertension in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wira, C.R., 3rd; Kearns, T.; Fleming-Nouri, A.; Tyrrell, J.D.; Wira, C.M.; Aydin, A. Considering adverse effects of common antihypertensive medications in the ED. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2024, 26, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alp, C.; Karahan, I.; Kalcık, M. Adverse reactions associated with the use of antihypertensive drugs: Review in the light of current literature. Turk. J. Clin. Lab. 2018, 4, 342–347. [Google Scholar]

- Battistoni, A.; Tocci, G.; Coluccia, R.; Burnier, M.; Ruilope, L.M.; Volpe, M. Antihypertensive drugs and the risk of cancer: A critical review of available evidence and perspective. J. Hypertens. 2020, 38, 1005–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albasri, A.; Hattle, M.; Koshiaris, C.; Dunnigan, A.; Paxton, B.; Fox, S.E.; Smith, M.; Archer, L.; Levis, B.; Payne, R.A.; et al. Association between antihypertensive treatment and adverse events: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, 372, n189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Jhawat, V. Induction of type 2 diabetes mellitus with antihypertensive therapy: Is there any role of alpha adducin, ACE, and IRS-1 gene? Value Health Reg. Issues 2017, 12, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Y.; Tang, X.; Xie, L.; Meng, G.; Ji, Y. Aliskiren improves endothelium-dependent relaxation of thoracic aorta by activating PI3K/Akt/eNOS signal pathway in SHR. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2016, 43, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ataei Ataabadi, E.; Golshiri, K.; Jüttner, A.; Krenning, G.; Danser, A.H.J.; Roks, A.J.M. Nitric oxide–cGMP signaling in hypertension: Current and future options for pharmacotherapy. Hypertension 2020, 76, 1055–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, J.A.; Kirkby, N.S. Eicosanoids, prostacyclin and cyclooxygenase in the cardiovascular system. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 176, 1038–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, D.C.; Naveed, M.; Gordon, A.; Majeed, F.; Saeed, M.; Ogbuke, M.I.; Atif, M.; Zubair, H.M.; Changxing, L. β-Adrenergic receptor: An essential target in cardiovascular diseases. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 25, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, D.; Syed, A.U.; Prada, M.P.; Nystoriak, M.A.; Santana, L.F.; Nieves-Cintrón, M.; Navedo, M.F. Calcium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Adv. Pharmacol. 2017, 78, 49–87. [Google Scholar]

- Tykocki, N.R.; Boerman, E.M.; Jackson, W.F. Smooth muscle ion channels and regulation of vascular tone in resistance arteries and arterioles. Compr. Physiol. 2017, 7, 485–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forrester, S.J.; Booz, G.W.; Sigmund, C.D.; Coffman, T.M.; Kawai, T.; Rizzo, V.; Scalia, R.; Eguchi, S. Angiotensin II signal transduction: An update on mechanisms of physiology and pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2018, 98, 1627–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alagawany, M.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Farag, M.R.; Gopi, M.; Karthik, K.; Malik, Y.S.; Dhama, K. Rosmarinic acid: Modes of action, medicinal values and health benefits. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 2017, 18, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alavi, M.S.; Fanoudi, S.; Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar, M.; Mehri, S.; Hosseinzadeh, H. An updated review of protective effects of rosemary and its active constituents against natural and chemical toxicities. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1313–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birtić, S.; Dussort, P.; Pierre, F.X.; Bily, A.C.; Roller, M. Carnosic acid. Phytochemistry 2015, 115, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loussouarn, M.; Krieger-Liszkay, A.; Svilar, L.; Bily, A.; Birtić, S.; Havaux, M. Carnosic acid and carnosol, two major antioxidants of rosemary, act through different mechanisms. Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 1381–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, M.; Imran, M.; Gondal, T.A.; Imran, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Amir, R.M.; Sajid, M.W.; Qaisrani, T.B.; Atif, M.; Hussain, G.; et al. Therapeutic potential of rosmarinic acid: A comprehensive review. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 3139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor, S.; Mohammad, T.; Rub, M.A.; Raza, A.; Azum, N.; Yadav, D.K.; Hassan, M.I.; Asiri, A.M. Biomedical features and therapeutic potential of rosmarinic acid. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2022, 45, 205–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar, M.K.; Anwar, S.; Hasan, G.M.; Shamsi, A.; Islam, A.; Parvez, S.; Hassan, M.I. Comprehensive insights into biological roles of rosmarinic acid: Implications in diabetes, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, M.A.; Samaha, A.A.; Ballan, S.; Saleh, A.I.; Iratni, R.; Eid, A.H. Salvia fruticosa induces vasorelaxation in rat isolated thoracic aorta: Role of the PI3K/Akt/eNOS/NO/cGMP signaling pathway. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Shah, A.J.; Khan, T.; Roberts, R. Mechanism underlying the vasodilation induced by diosmetin in porcine coronary artery. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 884, 173400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.S.; Loh, Y.C.; Tew, W.Y.; Yam, M.F. Vasorelaxant effect of 3,5,4′-trihydroxy-trans-stilbene (resveratrol) and its underlying mechanism. Inflammopharmacology 2020, 28, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, T.; Shah, A.J.; Roberts, R. Mechanisms mediating the vasodilatory effects of juglone in porcine isolated coronary artery. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 866, 172815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.; Mun, S.Y.; Zhuang, W.; Jeong, J.; Kim, H.R.; Park, H.; Han, E.T.; Han, J.H.; Chun, W.; Li, H.; et al. The antidiabetic drug ipragliflozin induces vasorelaxation of rabbit femoral artery by activating a Kv channel, the SERCA pump, and the PKA signaling pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 972, 176589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.Y.; Zhao, W.R.; Shi, W.T.; Xiao, Y.; Ma, Z.L.; Xue, J.G.; Zhang, L.Q.; Ye, Q.; Chen, X.L.; Tang, J.Y. Endothelial-dependent and independent vascular relaxation effect of tetrahydropalmatine on rat aorta. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, J.C.; da Silva, R.C.V.; Costa, P.; da Silva, L.M.; Cassemiro, N.S.; Gasparotto Junior, A.; Silva, D.B.; de Souza, P. Role of K+ and Ca2+ channels in the vasodilator effects of Plectranthus barbatus (Brazilian boldo) in hypertensive rats. Cardiovasc. Ther. 2023, 2023, 9948707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, C.S.; Yam, M.F. Mechanism of vasorelaxation induced by 3′-hydroxy-5,6,7,4′-tetramethoxyflavone in the rat aortic ring assay. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2018, 391, 561–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, K.; Bessho, N.; Kaneko, N.; Okudaira, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Kobayashi, T. Glucagon-like peptide-1 increased the vascular relaxation response via AMPK/Akt signaling in diabetic mice aortas. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 865, 172776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneda, H.; Otomo, R.; Sasaki, N.; Omi, T.; Sato, T.; Kaneda, T. Endothelium-independent vasodilator effects of nobiletin in rat aorta. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 140, 48–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero, M.S.; Nuñez, S.; Les, F.; Castro, M.; Gómez-Rincón, C.; Arruebo, M.P.; Plaza, M.Á.; Köhler, R.; López, V. The potential role of everlasting flower (Helichrysum stoechas Moench) as an antihypertensive agent: Vasorelaxant effects in the rat aorta. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.; Park, J.; Choi, H.Y.; Bu, Y.; Lee, K. Antihypertensive effects of Lindera erythrocarpa Makino via NO/cGMP pathway and Ca2+ and K+ channels. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirel, S.; Sahinturk, S.; Isbil, N.; Ozyener, F. Physiological role of K+ channels in irisin-induced vasodilation in rat thoracic aorta. Peptides 2022, 147, 170685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoo, A.; van Zanten, J.J.C.S.V.; Metsios, G.S.; Carroll, D.; Kitas, G.D. The endothelium and its role in regulating vascular tone. Open Cardiovasc. Med. J. 2010, 4, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.; Vanhoutte, P.M.; Leung, S.W. Vascular nitric oxide: Beyond eNOS. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2015, 129, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghigo, A.; Li, M. Phosphoinositide 3-kinase: Friend and foe in cardiovascular disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2015, 6, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, F. The cGMP system: Components and function. Biol. Chem. 2020, 401, 447–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serreli, G.; Deiana, M. Role of dietary polyphenols in the activity and expression of nitric oxide synthases: A review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.F.; Liu, F.; Qiao, M.M.; Shu, H.Z.; Li, X.C.; Peng, C.; Xiong, L. Vasorelaxant effect of curcubisabolanin A isolated from Curcuma longa through the PI3K/Akt/eNOS signaling pathway. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2022, 294, 115332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Fu, B.; Xu, B.; Mi, X.; Li, G.; Ma, C.; Xie, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Z. Rosmarinic acid alleviates the endothelial dysfunction induced by hydrogen peroxide in rat aortic rings via activation of AMPK. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2017, 2017, 7091904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, W.F. Potassium channels in regulation of vascular smooth muscle contraction and growth. Adv. Pharmacol. 2017, 78, 89–144. [Google Scholar]

- Dogan, M.F.; Yildiz, O.; Arslan, S.O.; Ulusoy, K.G. Potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle: A pathophysiological and pharmacological perspective. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 2019, 33, 504–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazmand, S.; Fereidouni, E.; Mahmoudabady, M.; Hosseini, M. Teucrium polium-induced vasorelaxation mediated by endothelium-dependent and endothelium-independent mechanisms in isolated rat thoracic aorta. Pharmacogn. Res. 2017, 9, 372–377. [Google Scholar]

- Redel-Traub, G.; Sampson, K.J.; Kass, R.S.; Bohnen, M.S. Potassium channels as therapeutic targets in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Shin, S.; Park, J.; Choi, H.Y.; Lee, K. Vasorelaxant effects and its mechanisms of the rhizome of Acorus gramineus on isolated rat thoracic aorta. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 4386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudo, R.; Yuui, K.; Kasuda, S. Endothelium-independent relaxation of vascular smooth muscle induced by persimmon-derived polyphenol phytocomplex in rats. Nutrients 2021, 14, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manville, R.W.; Baldwin, S.N.; Eriksen, E.Ø.; Jepps, T.A.; Abbott, G.W. Medicinal plant rosemary relaxes blood vessels by activating vascular smooth muscle KCNQ channels. FASEB J. 2023, 37, e23125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amberg, G.C.; Navedo, M.F. Calcium dynamics in vascular smooth muscle. Microcirculation 2013, 20, 281–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.; Khalil, R.A. Calcium signaling dynamics in vascular cells and their dysregulation in vascular disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touyz, R.M.; Alves-Lopes, R.; Rios, F.J.; Camargo, L.L.; Anagnostopoulou, A.; Arner, A.; Montezano, A.C. Vascular smooth muscle contraction in hypertension. Cardiovasc. Res. 2018, 114, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, Y. Ca2+ microdomains in vascular smooth muscle cells: Roles in vascular tone regulation and hypertension. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2025, 158, 59–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasannarong, M.; Saengsirisuwan, V.; Surapongchai, J.; Buniam, J.; Chukijrungroat, N.; Rattanavichit, Y. Rosmarinic acid improves hypertension and skeletal muscle glucose transport in angiotensin II-treated rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Effect | Conc. | PE Cont. (mg) | pD2 | Rmax (%) | n | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosmarinic acid | Vasorelaxant effect | 10−10–10−5 M | 1362.63 ± 18.36 | 7.67 ± 0.04 | 93.70 ± 5.26 | 8 | - |

| Rosmarinic acid (E-) | Vasorelaxant effect | 10−10–10−5 M | 1450.75 ± 45.44 | 5.26 ± 0.18 | 46.57 ± 7.88 | 8 | - |

| LY294002 | PI3K inhibitor | 10 µM | 1421.79 ± 38.56 | 4.17 ± 0.11 | 34.97 ± 4.47 | 8 | [25] |

| Triciribine | Akt inhibitor | 10 µM | 1452.24 ± 38.54 | 4.57 ± 0.18 | 39.84 ± 5.93 | 8 | [25] |

| L-NAME | eNOS inhibitor | 100 µM | 1452.53 ± 39.69 | 5.27 ± 0.14 | 47.81 ± 6.09 | 8 | [36] |

| ODQ | sGC inhibitor | 10 µM | 1393.33 ± 15.42 | 5.02 ± 0.09 | 43.95 ± 7.74 | 8 | [27] |

| Methylene blue | cGMP inhibitor | 10 µM | 1389.41 ± 14.72 | 5.57 ± 0.12 | 50.02 ± 7.75 | 8 | [27] |

| KT5823 | PKG inhibitor | 1 µM | 1419.00 ± 17.80 | 4.37 ± 0.11 | 37.60 ± 5.03 | 8 | [29] |

| Dorsomorphin | AMPK inhibitor | 1 µM | 1425.27 ± 18.97 | 7.47 ± 0.16 | 88.57 ± 4.45 | 8 | [33] |

| Indomethacin | Cyclooxygenase inhibitor | 10 µM | 1429.99 ± 18.01 | 7.53 ± 0.05 | 89.74 ± 5.13 | 8 | [27] |

| SQ22536 | Adenylate cyclase inhibitor | 50 µM | 1398.38 ± 34.35 | 7.59 ± 0.08 | 88.89 ± 3.98 | 8 | [29] |

| Propranolol | Beta-adrenergic receptor blocker | 1 µM | 1435.93 ± 42.92 | 7.46 ± 0.05 | 88.07 ± 4.56 | 8 | [27] |

| Atropine | Muscarinic receptor blocker | 1 µM | 1437.38 ± 36.42 | 7.65 ± 0.09 | 89.42 ± 4.49 | 8 | [27] |

| Tetraethylammonium | Potassium channel blocker | 1 mM | 1372.99 ± 15,84 | 5.09 ± 0.15 | 45.46 ± 7.21 | 8 | [27] |

| Iberiotoxin | BKCa channel blocker | 10 nM | 1442.11 ± 43.40 | 5.79 ± 0.12 | 56.13 ± 9.53 | 8 | [34] |

| TRAM-34 | IKCa channel blocker | 1 µM | 1436.32 ± 62.49 | 5.37 ± 0.14 | 48.89 ± 6.91 | 8 | [35] |

| Apamin | SKCa channel blocker | 1 µM | 1431.24 ± 42.23 | 7.57 ± 0.05 | 88.68 ± 4.99 | 8 | [35] |

| Glyburide | KATP channel blocker | 10 µM | 1422.27 ± 44.28 | 7.59 ± 0.06 | 86.79 ± 6.35 | 8 | [27] |

| 4-Aminopyridine | Kv channel blocker | 1 mM | 1416.24 ± 20.74 | 6.07 ± 0.11 | 59.99 ± 7.64 | 8 | [27] |

| XE-991 | Kv7.1–7.5 blocker | 10 µM | 1411.53 ± 69.88 | 6.37 ± 0.10 | 64.34 ± 5.54 | 8 | [29] |

| Anandamide | K2P channel blocker | 10 µM | 1429.44 ± 18.28 | 7.66 ± 0.06 | 86.98 ± 6.45 | 8 | [37] |

| BaCl2 | Kir channel blocker | 10 µM | 1438.80 ± 36.83 | 7.46 ± 0.07 | 87.82 ± 6.34 | 8 | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sahinturk, S.; Isbil, N. Rosmarinic Acid Induces Vasorelaxation via Endothelium-Dependent, Potassium Channel-Related, and Calcium-Modulated Pathways: Evidence from Rat Aortic Rings. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2936. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122936

Sahinturk S, Isbil N. Rosmarinic Acid Induces Vasorelaxation via Endothelium-Dependent, Potassium Channel-Related, and Calcium-Modulated Pathways: Evidence from Rat Aortic Rings. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):2936. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122936

Chicago/Turabian StyleSahinturk, Serdar, and Naciye Isbil. 2025. "Rosmarinic Acid Induces Vasorelaxation via Endothelium-Dependent, Potassium Channel-Related, and Calcium-Modulated Pathways: Evidence from Rat Aortic Rings" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 2936. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122936

APA StyleSahinturk, S., & Isbil, N. (2025). Rosmarinic Acid Induces Vasorelaxation via Endothelium-Dependent, Potassium Channel-Related, and Calcium-Modulated Pathways: Evidence from Rat Aortic Rings. Biomedicines, 13(12), 2936. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13122936