Esophageal Lichen Planus—Contemporary Insights and Emerging Trends

Abstract

1. Lichen Planus

2. Pathogenesis of LP

3. Esophageal Lichen Planus

4. Diagnostic Features of ELP

4.1. Clinical Symptoms

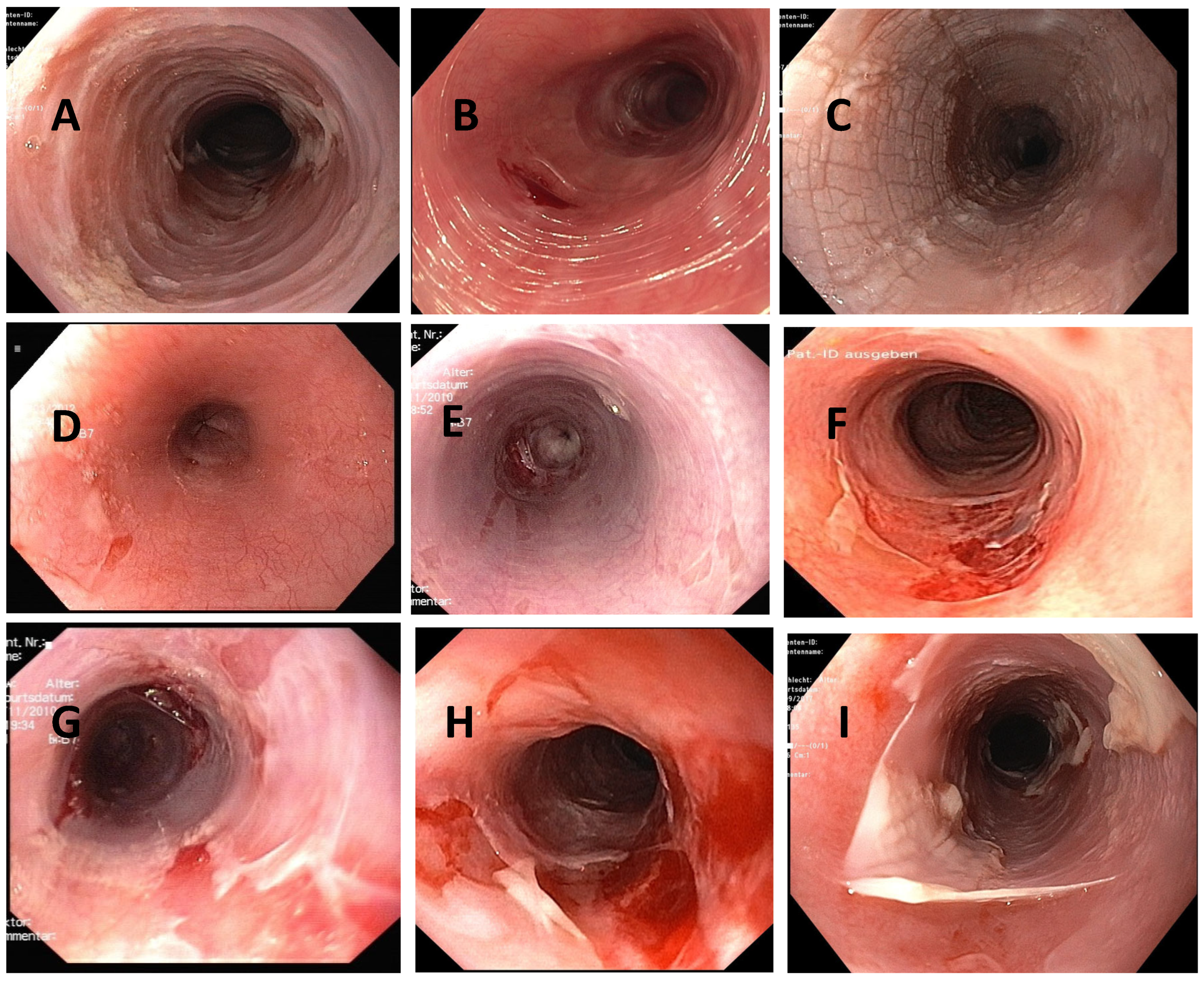

4.2. Macroscopy

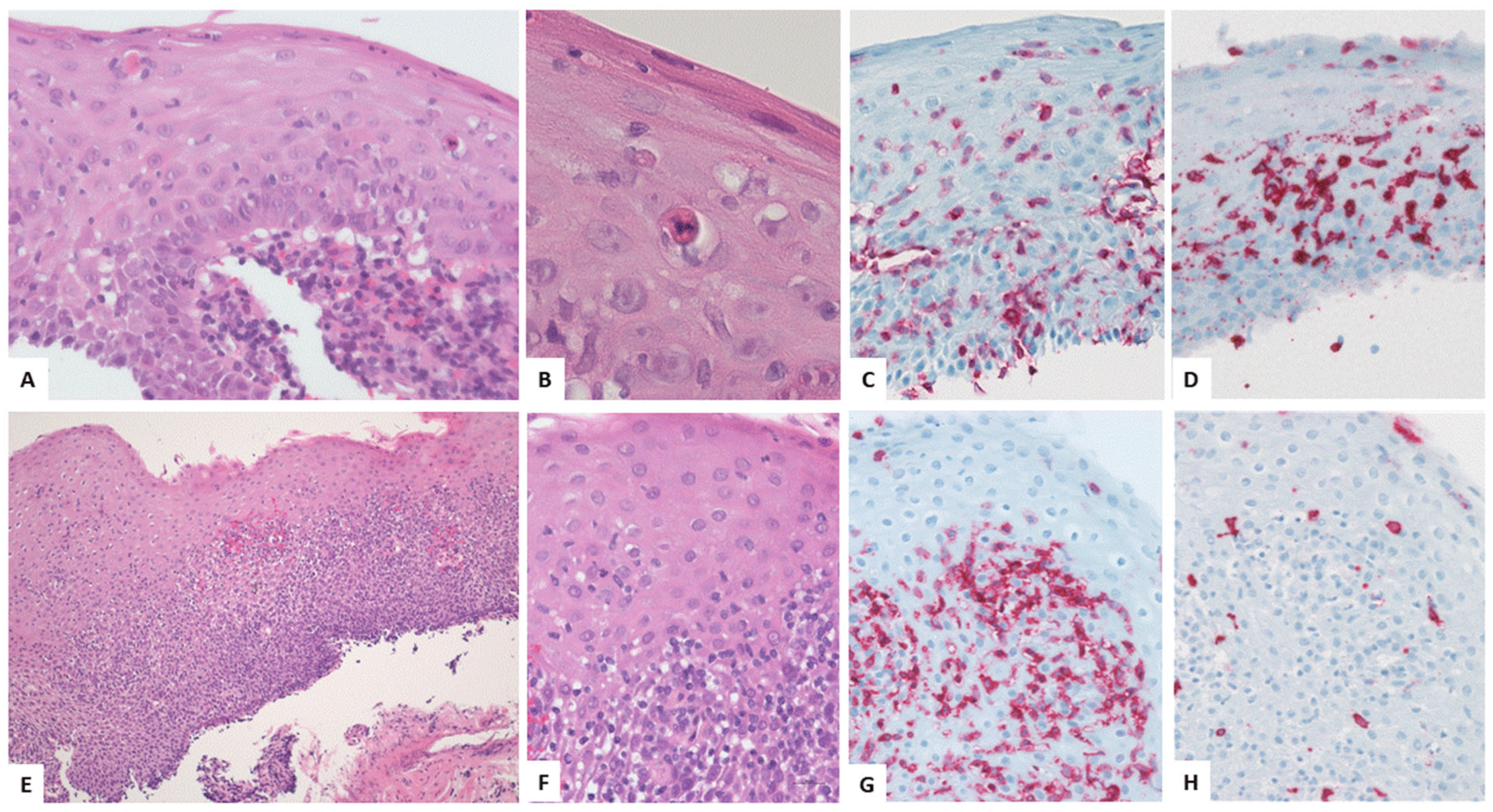

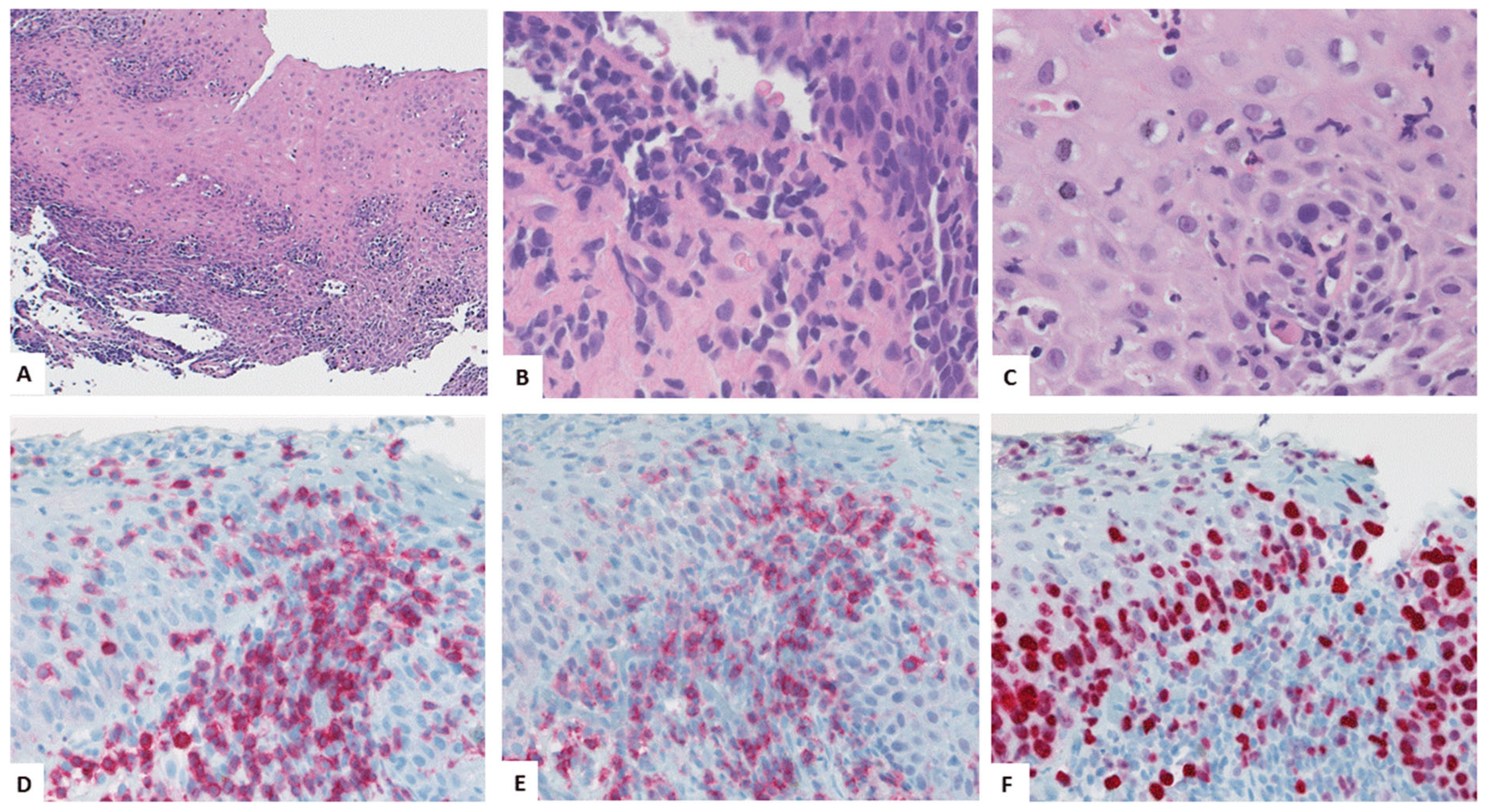

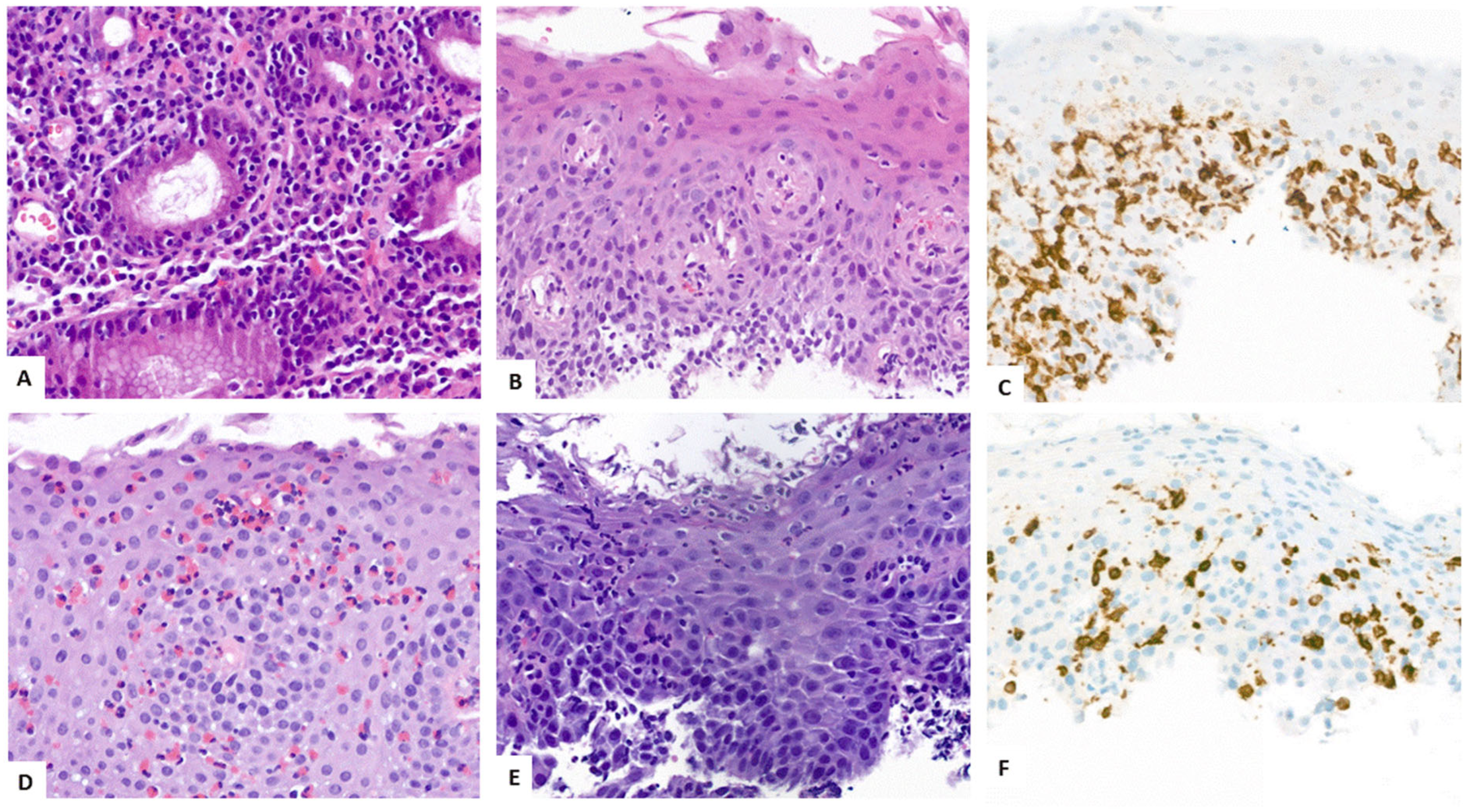

4.3. Key Morphologic and Immunophenotypic Features of ELP

4.4. ELP Histopathology: GENERAL Points and Caution

4.5. Direct Immunofluorescence

4.6. Proposed Criteria for Diagnosis of ELP

5. Differential Diagnoses

6. Therapy

6.1. Complications: Esophageal Stenosis and Food Impaction

6.2. ELP as Precancerous Condition

7. Proposal for Management of ELP

8. Emerging Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EGD | esophagogastroduodenoscopy |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor α |

| IFN-γ | interferon γ |

| SCC | squamous cell carcinoma |

| ILC1 cells | group 1 innate lymphoid cells |

| NKT | natural killer T-cells |

| NK | natural killer cells |

| EoE | eosinophilic esophagitis |

| APC | antigen presenting cells |

| MHC | major histocompatibility complex |

| JAK | janus kinase |

| STAT | signal transducers and activators of transcription |

| LP | lichen planus |

| ELP | esophageal lichen planus |

| EEM | esophageal epidermoid metaplasia |

References

- Le Cleach, L.; Chosidow, O. Clinical Practice. Lichen Planus. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 366, 723–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payette, M.J.; Weston, G.; Humphrey, S.; Yu, J.; Holland, K.E. Lichen Planus and Other Lichenoid Dermatoses: Kids Are Not Just Little People. Clin. Dermatol. 2015, 33, 631–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, G.; Payette, M. Update on Lichen Planus and Its Clinical Variants. Int. J. Women's Dermatol. 2015, 1, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimani, F.; Forchhammer, S.; Schloegl, A.; Ghoreschi, K.; Meier, K. Lichen Planus—A Clinical Guide. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. JDDG 2021, 19, 864–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhry, S.; Manmohan, G.; Yadav, K.A.; Madhulika, G. Lichen Planus—A Refractory Autoimmune Disorder. IP Indian J. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2023, 9, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Tang, X.; Zheng, X.; Ge, S.; Wen, H.; Lin, X.; Chen, Z.; Lu, L. Global Prevalence and Incidence Estimates of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.Á.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; González-Ruiz, I.; González-Ruiz, L.; Ayén, Á.; Lenouvel, D.; Ruiz-Ávila, I.; Ramos-García, P. Worldwide Prevalence of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 813–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Limketkai, B.N.; Montgomery, E.A. Recently Highlighted Non-Neoplastic Pathologic Entities of the Upper GI Tract and Their Clinical Significance. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014, 80, 960–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuten-Shorrer, M.; Menon, R.S.; Lerman, M.A. Mucocutaneous Diseases. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 64, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gru, A.A.; Salavaggione, A.L. Lichenoid and Interface Dermatoses. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2017, 34, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorouhi, F.; Davari, P.; Fazel, N. Cutaneous and Mucosal Lichen Planus: A Comprehensive Review of Clinical Subtypes, Risk Factors, Diagnosis, and Prognosis. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 742826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, S.; Choudhury, P.; Ahmad, S.A.; Alam, T.; Panigrahi, R.; Aziz, S.; Kaleem, S.M.; Priyadarshini, S.R.; Sahoo, P.K.; Hasan, S. Vitamin D in the Treatment of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, F.; Langan, E.A.; Recke, A. Lichen Planus Pemphigoides: From Lichenoid Inflammation to Autoantibody-Mediated Blistering. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannides, D.; Vakirlis, E.; Kemeny, L.; Marinovic, B.; Massone, C.; Murphy, R.; Nast, A.; Ronnevig, J.; Ruzicka, T.; Cooper, S.M.; et al. European S1 Guidelines on the Management of Lichen Planus: A Cooperation of the European Dermatology Forum with the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2020, 34, 1403–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodi, G.; Manfredi, M.; Mercadante, V.; Murphy, R.; Carrozzo, M. Interventions for Treating Oral Lichen Planus: Corticosteroid Therapies. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2, CD001168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Q. Updates on Immunological Mechanistic Insights and Targeting of the Oral Lichen Planus Microenvironment. Front. Immunol. 2023, 13, 1023213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarcón, I.; Alarcón, C.; Arellano, J. Overview of Lichen Planus Pathogenesis and Review of Possible Future Therapies. JAAD Rev. 2025, 3, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.-S.L.; Gould, A.; Kurago, Z.; Fantasia, J.; Muller, S. Diagnosis of Oral Lichen Planus: A Position Paper of the American Academy of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2016, 122, 332–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McParland, H.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral Lichenoid Contact Lesions to Mercury and Dental Amalgam—A Review. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 589569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasul, T.F.; Anderson, J.; Bergholz, D.R.; Faiz, A.; Prasad, R.R. Gold Dental Implant-Induced Oral Lichen Planus. Cureus 2022, 14, e21852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrente-Castells, E.; Figueiredo, R.; Berini-Aytés, L.; Gay-Escoda, C. Clinical Features of Oral Lichen Planus. A Retrospective Study of 65 Cases. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cirugia Bucal 2010, 15, e685–e690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassol-Spanemberg, J.; Rodríguez-de Rivera-Campillo, M.-E.; Otero-Rey, E.-M.; Estrugo-Devesa, A.; Jané-Salas, E.; López-López, J. Oral Lichen Planus and Its Relationship with Systemic Diseases. A Review of Evidence. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2018, 10, e938–e944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.; Ahmed, S.; Kiran, R.; Panigrahi, R.; Thachil, J.; Saeed, S. Oral Lichen Planus and Associated Comorbidities: An Approach to Holistic Health. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 3504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromme, M.; Schneider, C.V.; Schlapbach, C.; Cazzaniga, S.; Trautwein, C.; Rader, D.J.; Borradori, L.; Strnad, P. Comorbidities in Lichen Planus by Phenome-Wide Association Study in Two Biobank Population Cohorts. Br. J. Dermatol. 2022, 187, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgescu, S.R.; Tampa, M.; Mitran, M.I.; Mitran, C.I.; Sarbu, M.I.; Nicolae, I.; Matei, C.; Caruntu, C.; Neagu, M.; Popa, M.I. Potential Pathogenic Mechanisms Involved in the Association between Lichen Planus and Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Exp. Ther. Med. 2019, 17, 1045–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, Y.; Nishida, N.; Toyo-oka, L.; Kawaguchi, A.; Amoroso, A.; Carrozzo, M.; Sata, M.; Mizokami, M.; Tokunaga, K.; Tanaka, Y. Genome-Wide Association Study Identifies Risk Variants for Lichen Planus in Patients With Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 15, 937–944.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Porras-Carrique, T.; González-Moles, M.Á.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Ramos-García, P. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 1391–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerqueira, J.D.M.; Moura, J.R.; Arsati, F.; Lima-Arsati, Y.B.d.O.; Bittencourt, R.A.; Freitas, V.S. Psychological Disorders and Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9, e12363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adamo, D.; Calabria, E.; Coppola, N.; Lo Muzio, L.; Giuliani, M.; Bizzoca, M.E.; Azzi, L.; Croveri, F.; Colella, G.; Boschetti, C.E.; et al. Psychological Profile and Unexpected Pain in Oral Lichen Planus: A Case–Control Multicenter SIPMO Studya. Oral Dis. 2022, 28, 398–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eyerich, K.; Eyerich, S. Immune Response Patterns in Non-Communicable Inflammatory Skin Diseases. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2018, 32, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, J.W.; Kukreja, K.; Camisa, C.; Richter, J.E. Demystifying Esophageal Lichen Planus: A Comprehensive Review of a Rare Disease You Will See in Practice. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 117, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlov, M.; Levit, E.K.; Silvers, D.N.; Brichkov, I. Severe Esophageal Lichen Planus Treated With Tofacitinib. Cutis 2023, 111, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katzka, D.A.; Smyrk, T.C.; Bruce, A.J.; Romero, Y.; Alexander, J.A.; Murray, J.A. Variations in Presentations of Esophageal Involvement in Lichen Planus. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2010, 8, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, K.; Codipilly, D.C.; Sunjaya, D.; Fang, H.; Arora, A.S.; Katzka, D.A. Esophageal Lichen Planus Is Associated With a Significant Increase in Risk of Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2019, 17, 1902–1903.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrat, F.J.; Crow, M.K.; Ivashkiv, L.B. Interferon Target-Gene Expression and Epigenomic Signatures in Health and Disease. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 1574–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsky, W.; King, B.A. JAK Inhibitors in Dermatology: The Promise of a New Drug Class. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017, 76, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damsky, W.; Wang, A.; Olamiju, B.; Peterson, D.; Galan, A.; King, B. Treatment of Severe Lichen Planus with the JAK Inhibitor Tofacitinib. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020, 145, 1708–1710.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Tsoi, L.C.; Sarkar, M.K.; Xing, X.; Xue, K.; Uppala, R.; Berthier, C.C.; Zeng, C.; Patrick, M.; Billi, A.C.; et al. IFN-γ Enhances Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity against Keratinocytes via JAK2/STAT1 in Lichen Planus. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav7561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumfiel, C.M.; Patel, M.H.; Severson, K.J.; Zhang, N.; Li, X.; Quillen, J.K.; Zunich, S.M.; Branch, E.L.; Nelson, S.A.; Pittelkow, M.R.; et al. Ruxolitinib Cream in the Treatment of Cutaneous Lichen Planus: A Prospective, Open-Label Study. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2022, 142, 2109–2116.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solimani, F.; Meier, K.; Ghoreschi, K. Emerging Topical and Systemic JAK Inhibitors in Dermatology. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solimani, F.; Dilling, A.; Ghoreschi, F.C.; Nast, A.; Ghoreschi, K.; Meier, K. Upadacitinib for Treatment-Resistant Lichen Amyloidosis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. JEADV 2023, 37, e633–e635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didona, D.; Caposiena Caro, R.D.; Sequeira Santos, A.M.; Solimani, F.; Hertl, M. Therapeutic Strategies for Oral Lichen Planus: State of the Art and New Insights. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 997190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Shihabi, B.M.; Jackson, J.M. Dysphagia Due to Pharyngeal and Oesophageal Lichen Planus. J. Laryngol. Otol. 1982, 96, 567–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco, D.L.; Islam, S.R.; Lam-Himlin, D.M.; Fleischer, D.E.; Pasha, S.F. Presentation, Diagnosis, and Management of Esophageal Lichen Planus: A Series of Six Cases. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2015, 9, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, J.A.; Law, R.M.; Fiman, K.H.; Roberts, C.A. Esophageal Lichen Planus: A Case Report and Review of the Literature. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 2278–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miehlke, S.; Reinhold, B.; Schröder, S. Successful treatment of Lichen planus esophagitis with topical budesonide. Z. Gastroenterol. 2012, 50, 1104–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickens, C.M.; Heseltine, D.; Walton, S.; Bennett, J.R. The Oesophagus in Lichen Planus: An Endoscopic Study. BMJ 1990, 300, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quispel, R.; van Boxel, O.S.; Schipper, M.E.; Sigurdsson, V.; Canninga-van Dijk, M.R.; Kerckhoffs, A.; Smout, A.J.; Samsom, M.; Schwartz, M.P. High Prevalence of Esophageal Involvement in Lichen Planus: A Study Using Magnification Chromoendoscopy. Endoscopy 2009, 41, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schauer, F.; Monasterio, C.; Technau-Hafsi, K.; Kern, J.S.; Lazaro, A.; Deibert, P.; Hasselblatt, P.; Schwacha, H.; Heeg, S.; Brass, V.; et al. Esophageal Lichen Planus: Towards Diagnosis of an Underdiagnosed Disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2019, 54, 1189–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, L.P.; Lightdale, C.J.; Grossman, M.E. Lichen Planus of the Esophagus: What Dermatologists Need to Know. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2011, 65, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harewood, G.C.; Murray, J.A.; Cameron, A.J. Esophageal Lichen Planus: The Mayo Clinic Experience. Dis. Esophagus Off. J. Int. Soc. Dis. Esophagus ISDE 1999, 12, 309–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kern, J.S.; Technau-Hafsi, K.; Schwacha, H.; Kuhlmann, J.; Hirsch, G.; Brass, V.; Deibert, P.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Kreisel, W. Esophageal Involvement Is Frequent in Lichen Planus: Study in 32 Patients with Suggestion of Clinicopathologic Diagnostic Criteria and Therapeutic Implications. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monasterio, C.; Decker, A.; Schauer, F.; Büttner, N.; Schmidt, A.; Schmitt-Gräff, A.; Kreisel, W. Der Lichen planus des Ösophagus—Eine unterschätzte Erkrankung. Z. Gastroenterol. 2021, 59, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, A.; Schauer, F.; Lazaro, A.; Monasterio, C.; Schmidt, A.R.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Kreisel, W. Esophageal Lichen Planus: Current Knowledge, Challenges and Future Perspectives. World J. Gastroenterol. 2022, 28, 5893–5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diehl, R.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Kiritsi, D.; Kreisel, W.; Schmidt, A.; Decker, A.; Schauer, F. Esophageal Lichen Planus: A Prospective Interdisciplinary, Monocentric Cohort Study. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. JDDG 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumann, A.; Katzka, D.A. Diagnosis and Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Podboy, A.; Sunjaya, D.; Smyrk, T.C.; Murray, J.A.; Binder, M.; Katzka, D.A.; Alexander, J.A.; Halland, M. Oesophageal Lichen Planus: The Efficacy of Topical Steroid-Based Therapies. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2017, 45, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aby, E.S.; Eckmann, J.D.; Abimansour, J.; Katzka, D.A.; Beveridge, C.; Triggs, J.R.; Dbouk, M.; Abdi, T.; Turner, K.O.; Antunes, C.; et al. Esophageal Lichen Planus: A Descriptive Multicenter Report. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2023, 58, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blonski, W.; Slone, S.; Jacobs, J.W. Lichen Planus Esophagitis. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2023, 39, 308–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghai, M.B.; Parsa, N.; Sloan, J.A. The Current State of Esophageal Lichen Planus. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2025, 41, 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaaslan, S.; Qin, L.; Hissong, E.; Jessurun, J. A Reappraisal of Oesophageal Mucosal Biopsy Specimens Showing Sloughing. Histopathology 2025, 87, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coady, L.C.; Sheahan, K.; Brown, I.S.; Carneiro, F.; Gill, A.J.; Kumarasinghe, P.; Kushima, R.; Lauwers, G.Y.; Pai, R.K.; Shepherd, N.A.; et al. Esophageal Lymphocytosis: Exploring the Knowns and Unknowns of This Pattern of Esophageal Injury. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 18, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, C.A.; Ichiya, T.; Schmidt, P.T. Lymphocytic Oesophagitis, Eosinophilic Oesophagitis and Compound Lymphocytic-Eosinophilic Oesophagitis I: Histological and Immunohistochemical Findings. J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 70, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, D.T.; Hammer, S.; Langer, R.; Yantiss, R.K. Lymphocytic Esophagitis: An Update on Histologic Diagnosis, Endoscopic Findings, and Natural History. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1434, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittman, M.E. Lymphocytic Esophagitis: Current Understanding and Controversy. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2022, 46, e55–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, S.; Mohammadi, S.M.K.; Singhal, A.; Sonnenberg, A.; Genta, R.M.; Rugge, M. Lichenoid Esophagitis: A Clinicopathological Comparison with Lymphocytic and Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. JGLD 2025, 34, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salaria, S.N.; Abu Alfa, A.K.; Cruise, M.W.; Wood, L.D.; Montgomery, E.A. Lichenoid Esophagitis: Clinicopathologic Overlap with Established Esophageal Lichen Planus. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013, 37, 1889–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, J.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Kreisel, W.; Decker, A.; Schauer, F. Case Report: Lichenoid Esophagitis Revealing an HIV Infection. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1477787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Moles, M.Á.; Ruiz-Ávila, I.; González-Ruiz, L.; Ayén, Á.; Gil-Montoya, J.A.; Ramos-García, P. Malignant Transformation Risk of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review and Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. Oral Oncol. 2019, 96, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, A.L.; Fortuna, D.; Falk, G.W. Esophageal Lichen Planus and Development of Dysplasia. Gastro Hep Adv. 2023, 2, 35–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Moles, M.Á.; Ramos-García, P. An Evidence-Based Update on the Potential for Malignancy of Oral Lichen Planus and Related Conditions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2024, 16, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, L.S. Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid. Clin. Dermatol. 2001, 19, 703–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Maercke, P.; Günther, M.; Groth, W.; Gheorghiu, T.; Habermann, U. Lichen Ruber Mucosae with Esophageal Involvement. Endoscopy 1988, 20, 158–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malone, V.; Sheahan, K. Novel and Rare Forms of Oesophagitis. Histopathology 2021, 78, 4–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Straumann, A.; Spichtin, H.P.; Bernoulli, R.; Loosli, J.; Vögtlin, J. [Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis: A frequently overlooked disease with typical clinical aspects and discrete endoscopic findings]. Schweiz. Med. Wochenschr. 1994, 124, 1419–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Dellon, E.S. Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Diagnostic Tests and Criteria. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 28, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellon, E.S.; Liacouras, C.A.; Molina-Infante, J.; Furuta, G.T.; Spergel, J.M.; Zevit, N.; Spechler, S.J.; Attwood, S.E.; Straumann, A.; Aceves, S.S.; et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 1022–1033.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouphael, C.; Gordon, I.O.; Thota, P.N. Lymphocytic Esophagitis: Still an Enigma a Decade Later. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 949–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhondi, H. Sloughing Esophagitis: A Not so Common Entity. Int. J. Biomed. Sci. IJBS 2014, 10, 282–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokama, A.; Yamamoto, Y.-I.; Taira, K.; Nakamura, M.; Kobashigawa, C.; Nakamoto, M.; Hirata, T.; Kinjo, N.; Kinjo, F.; Takahashi, K.; et al. Esophagitis Dissecans Superficialis and Autoimmune Bullous Dermatoses: A Review. World J. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010, 2, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albert, D.M.; Ally, M.R.; Moawad, F.J. The Sloughing Esophagus: A Report of Five Cases. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 1816–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, J.E.; Rubenstein, J.H. Presentation and Epidemiology of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Gastroenterology 2018, 154, 267–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson-Knodell, C.L.; Codipilly, D.C.; Leggett, C.L. Making Dysphagia Easier to Swallow: A Review for the Practicing Clinician. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 965–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almashat, S.J.; Duan, L.; Goldsmith, J.D. Non-Reflux Esophagitis: A Review of Inflammatory Diseases of the Esophagus Exclusive of Reflux Esophagitis. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2014, 31, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, N.K.; Clarke, J.O. Evaluation and Management of Infectious Esophagitis in Immunocompromised and Immunocompetent Individuals. Curr. Treat. Options Gastroenterol. 2016, 14, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, K.M.; Katzka, D.A.; Raffals, L.E. Crohn’s Disease of the Esophagus: Clinical Features and Treatment Outcomes in the Biologic Era. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2015, 21, 2106–2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, K.; Tanida, S.; Inoue, N.; Kunisaki, R.; Kobayashi, K.; Nagahori, M.; Arai, K.; Uchino, M.; Koganei, K.; Kobayashi, T.; et al. Evidence-Based Diagnosis and Clinical Practice Guidelines for Intestinal Behçet’s Disease 2020 Edited by Intractable Diseases, the Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 679–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeiser, R.; Blazar, B.R. Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease—Biologic Process, Prevention, and Therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 2167–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colli Cruz, C.; Moura Nascimento Santos, M.J.; Wali, S.; Varatharajalu, K.; Thomas, A.; Wang, Y. Gastrointestinal Toxicities Associated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors Therapy: Risks and Management. Immunotherapy 2025, 17, 293–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greuter, T.; Safroneeva, E.; Bussmann, C.; Biedermann, L.; Vavricka, S.R.; Katzka, D.A.; Schoepfer, A.M.; Straumann, A. Maintenance Treatment Of Eosinophilic Esophagitis With Swallowed Topical Steroids Alters Disease Course Over A 5-Year Follow-up Period In Adult Patients. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 17, 419–428.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, M.; Mitchison, M.; Sweis, R. Lymphocytic Oesophagitis: Diagnosis and Management. Clin. Med. 2023, 23, 540–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, P.A.; Romano, R.C.; Moreira, R.K.; Ravi, K.; Sweetser, S. Esophagitis Dissecans Superficialis: Clinical, Endoscopic, and Histologic Features. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 2049–2057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mastracci, L.; Grillo, F.; Parente, P.; Unti, E.; Battista, S.; Spaggiari, P.; Campora, M.; Valle, L.; Fassan, M.; Fiocca, R. Non Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease Related Esophagitis: An Overview with a Histologic Diagnostic Approach. Pathologica 2020, 112, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruckner-Tuderman, L.; Has, C. Disorders of the Cutaneous Basement Membrane Zone--the Paradigm of Epidermolysis Bullosa. Matrix Biol. J. Int. Soc. Matrix Biol. 2014, 33, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kridin, K.; Kneiber, D.; Kowalski, E.H.; Valdebran, M.; Amber, K.T. Epidermolysis Bullosa Acquisita: A Comprehensive Review. Autoimmun. Rev. 2019, 18, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keate, R.F.; Williams, J.W.; Connolly, S.M. Lichen Planus Esophagitis: Report of Three Patients Treated with Oral Tacrolimus or Intraesophageal Corticosteroid Injections or Both. Dis. Esophagus Off. J. Int. Soc. Dis. Esophagus 2003, 16, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jobard-Drobacheff, C.; Blanc, D.; Quencez, E.; Zultak, M.; Paris, B.; Ottignon, Y.; Agache, P. Lichen Planus of the Oesophagus. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1988, 13, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolios, A.G.A.; Marques Maggio, E.; Gubler, C.; Cozzio, A.; Dummer, R.; French, L.E.; Navarini, A.A. Oral, Esophageal and Cutaneous Lichen Ruber Planus Controlled with Alitretinoin: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Dermatology 2013, 226, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, T.; Liang, S.; Sanagapalli, S. Budesonide Orodispersible Tablet for the Treatment of Refractory Esophageal Lichen Planus. ACG Case Rep. J. 2024, 11, e01460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagger-Jörgensen, H.; Abdulrasak, M.; Sandeman, K.; Binsalman, M.; Sjöberg, K. Oesophageal Lichen Planus Successfully Treated with Budesonide Orodispersible Tablets: A Case Report. Case Rep. Gastroenterol. 2024, 18, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wedgeworth, E.K.; Vlavianos, P.; Groves, C.J.; Neill, S.; Westaby, D. Management of Symptomatic Esophageal Involvement with Lichen Planus. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2009, 43, 915–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, M.S.; Zhao, L.; Gui, X.; Storr, M.; Andrews, C.N. Lichen Planus Is an Uncommon Cause of Nonspecific Proximal Esophageal Inflammation. Gut Liver 2013, 7, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reissmann, A.; Hahn, E.G.; Faller, G.; Herold, C.; Schwab, D. Sole Treatment of Lichen Planus-Associated Esophageal Stenosis with Injection of Corticosteroids. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006, 63, 168–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goñi Esarte, S.; Arín Letamendía, A.; Vila Costas, J.J.; Jiménez Pérez, F.J.; Ruiz-Clavijo García, D.; Carrascosa Gil, J.; Almendral López, M.L. [Rituximab as rescue therapy in refractory esophageal lichen planus]. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 36, 264–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bobadilla, J.; van der Hulst, R.W.; ten Kate, F.J.; Tytgat, G.N. Esophageal Lichen Planus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999, 50, 268–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbrook, R.; Riley, S. Esophageal Lichen Planus: Case Report and Literature Review. Dysphagia 2008, 23, 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafner, J.; Gubler, C.; Kaufmann, K.; Nobbe, S.; Navarini, A.A.; French, L.E. Apremilast Is Effective in Lichen Planus Mucosae-Associated Stenotic Esophagitis. Case Rep. Dermatol. 2016, 8, 224–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmentier, L.; Bron, B.-A.; Prins, C.; Samson, J.; Masouyé, I.; Borradori, L. Mucocutaneous Lichen Planus with Esophageal Involvement: Successful Treatment with an Anti-CD20 Monoclonal Antibody. Arch. Dermatol. 2008, 144, 1427–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eustace, K.; Clowry, J.; Kiely, C.; Murphy, G.M.; Harewood, G. The Challenges of Managing Refractory Oesphageal Lichen Planus. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2015, 184, 75–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieneck, V.; Decker, A.; Schmitt-Graeff, A.; Kreisel, W.; Schauer, F. Remission of Refractory Esophageal Lichen Planus Induced by Tofacitinib. Z. Gastroenterol. 2024, 62, 1384–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passeron, T.; Reinhardt, M.; Ehst, B.; Weiss, J.; Sluzevich, J.; Sticherling, M.; Reygagne, P.; Wohlrab, J.; Hertl, M.; Fazel, N.; et al. Secukinumab in Adult Patients with Lichen Planus: Efficacy and Safety Results from the Randomized Placebo-Controlled Proof-of-Concept PRELUDE Study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2024, 191, 680–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abduelmula, A.; Bagit, A.; Mufti, A.; Yeung, K.C.Y.; Yeung, J. The Use of Janus Kinase Inhibitors for Lichen Planus: An Evidence-Based Review. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2023, 27, 12034754231156100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoudi, H.; Daneshpajooh, M.; Dadkhahfar, S.; Robati, R.M.; Tehranchinia, Z.; Farokh, P.; Shariatnia, M.; Shahidi-Dadras, M.; Moravvej, H. Efficacy and Safety of Tofacitinib in the Treatment of Adults with Lichen Planopilaris: A Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2025, 162, 115129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, X.; Li, X.; Zhai, Z.; Zhang, M. JAK-STAT Pathway, Type I/II Cytokines, and New Potential Therapeutic Strategy for Autoimmune Bullous Diseases: Update on Pemphigus Vulgaris and Bullous Pemphigoid. Front. Immunol. 2025, 16, 1563286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kooybaran, N.R.; Petzold, G.; Schön, M.P.; Mössner, R. Esophageal Lichen Planus Successfully Treated with the JAK1/3 Inhibitor Tofacitinib. J. Dtsch. Dermatol. Ges. J. Ger. Soc. Dermatol. JDDG 2022, 20, 858–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, P.; Brun, A.; Zaidi, H.; Sejpal, D.V.; Trindade, A.J. Successful Treatment of a Persistent Esophageal Lichen Planus Stricture With a Fully Covered Metal Stent. ACG Case Rep. J. 2016, 3, 98–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, N.; Tapper, E.B.; Corban, C.; Sommers, T.; Leffler, D.A.; Lembo, A.J. The Clinical Predictors of Aetiology and Complications among 173 Patients Presenting to the Emergency Department with Oesophageal Food Bolus Impaction from 2004-2014. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2015, 42, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poincloux, L.; Rouquette, O.; Abergel, A. Endoscopic Treatment of Benign Esophageal Strictures: A Literature Review. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 11, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fugazza, A.; Repici, A. Endoscopic Management of Refractory Benign Esophageal Strictures. Dysphagia 2021, 36, 504–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, R.S.; Burns, M.M.; Gosselin, S. Ingestion of Caustic Substances. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 1739–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, P.; Jakobsson, M.; Heikinheimo, O.; Riska, A.; Gissler, M.; Pukkala, E. Cancer Risk of Lichen Planus: A Cohort Study of 13,100 Women in Finland. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halonen, P.; Jakobsson, M.; Heikinheimo, O.; Gissler, M.; Pukkala, E. Incidence of Lichen Planus and Subsequent Mortality in Finnish Women. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Kujan, O.; Shearston, K.; Farah, C.S. Oral Lichen Planus Has a Very Low Malignant Transformation Rate: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Using Strict Diagnostic and Inclusion Criteria. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 50, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arduino, P.G.; Magliano, A.; Gambino, A.; Macciotta, A.; Carbone, M.; Conrotto, D.; Karimi, D.; Carrozzo, M.; Broccoletti, R. Risk of Malignant Transformation in 3173 Subjects with Histopathologically Confirmed Oral Lichen Planus: A 33-Year Cohort Study in Northern Italy. Cancers 2021, 13, 5740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombeccari, G.P.; Pallotti, F.; Guzzi, G.; Spadari, F. Oral-Esophageal Lichen Planus Associated with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2008, 74, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chryssostalis, A.; Gaudric, M.; Terris, B.; Coriat, R.; Prat, F.; Chaussade, S. Esophageal Lichen Planus: A Series of Eight Cases Including a Patient with Esophageal Verrucous Carcinoma. A Case Series. Endoscopy 2008, 40, 764–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singhi, A.D.; Arnold, C.A.; Crowder, C.D.; Lam-Himlin, D.M.; Voltaggio, L.; Montgomery, E.A. Esophageal Leukoplakia or Epidermoid Metaplasia: A Clinicopathological Study of 18 Patients. Mod. Pathol. 2014, 27, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhi, A.D.; Arnold, C.A.; Lam-Himlin, D.M.; Nikiforova, M.N.; Voltaggio, L.; Canto, M.I.; McGrath, K.M.; Montgomery, E.A. Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Supports Epidermoid Metaplasia of the Esophagus as a Precursor to Esophageal Squamous Neoplasia. Mod. Pathol. 2017, 30, 1613–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.K.; Graham, R.P.; Murray, J.A. Epidermoid Metaplasia of the Esophagus. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2020, 95, 1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamboj, A.K.; Gibbens, Y.Y.; Hagen, C.E.; Wang, K.K.; Iyer, P.G.; Katzka, D.A. Esophageal Epidermoid Metaplasia: Clinical Characteristics and Risk of Esophageal Squamous Neoplasia. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 116, 1533–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellon, E.S. No Maintenance, No Gain in Long-Term Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2019, 17, 397–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blauvelt, A.; Chiricozzi, A. The Immunologic Role of IL-17 in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis Pathogenesis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2018, 55, 379–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutet, M.-A.; Nerviani, A.; Gallo Afflitto, G.; Pitzalis, C. Role of the IL-23/IL-17 Axis in Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis: The Clinical Importance of Its Divergence in Skin and Joints. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gueiros, L.; Arão, T.; Souza, T.; Vieira, C.; Gomez, R.; Almeida, O.; Lodi, G.; Leão, J. IL17A Polymorphism and Elevated IL17A Serum Levels Are Associated with Oral Lichen Planus. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul, N.; Shenoy, M. Role of Salivary and Serum IL17 and IL23 in the Pathogenesis of Oral Lichen Planus: A Systematic Review. Jundishapur J. Microbiol. 2022, 15, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Holstein, J.; Solimani, F.; Baum, C.; Meier, K.; Pollmann, R.; Didona, D.; Tekath, T.; Dugas, M.; Casadei, N.; Hudemann, C.; et al. Immunophenotyping in Pemphigus Reveals a TH17/TFH17 Cell–Dominated Immune Response Promoting Desmoglein1/3-Specific Autoantibody Production. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2021, 147, 2358–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grossberg, L.B.; Papamichael, K.; Cheifetz, A.S. Review Article: Emerging Drug Therapies in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 55, 789–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, D.; Ricciuto, A.; Lewis, A.; D’Amico, F.; Dhaliwal, J.; Griffiths, A.M.; Bettenworth, D.; Sandborn, W.J.; Sands, B.E.; Reinisch, W.; et al. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target Strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1570–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanizzi, F.; D’Amico, F.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S.; Dignass, A. Treatment Targets in IBD: Is It Time for New Strategies? Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2025, 77, 101990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centanni, L.; Cicerone, C.; Fanizzi, F.; D’Amico, F.; Furfaro, F.; Zilli, A.; Parigi, T.L.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Danese, S.; Allocca, M. Advancing Therapeutic Targets in IBD: Emerging Goals and Precision Medicine Approaches. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandborn, W.J.; Feagan, B.G.; D’Haens, G.; Wolf, D.C.; Jovanovic, I.; Hanauer, S.B.; Ghosh, S.; Petersen, A.; Hua, S.Y.; Lee, J.H.; et al. Ozanimod as Induction and Maintenance Therapy for Ulcerative Colitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 1280–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Goren, I.; Yang, B.; Lin, S.; Li, J.; Elias, M.; Fiocchi, C.; Rieder, F. The Sphingosine 1 Phosphate / Sphingosine 1 Phosphate Receptor Axis: A Unique Therapeutic Target in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 55, 277–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wils, P.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Etrasimod for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Immunotherapy 2023, 15, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Molina, C.; González-Suárez, B. Etrasimod: Modulating Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptors to Treat Ulcerative Colitis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 3890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Lopez de Turiso, F.; Guckian, K. Selective TYK2 Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutic Agents: A Patent Review (2019-2021). Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2022, 32, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellinato, F.; Gisondi, P.; Girolomoni, G. Latest Advances for the Treatment of Chronic Plaque Psoriasis with Biologics and Oral Small Molecules. Biol. Targets Ther. 2021, 15, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonciarz, M.; Pawlak-Buś, K.; Leszczyński, P.; Owczarek, W. TYK2 as a Therapeutic Target in the Treatment of Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases. Immunotherapy 2021, 13, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L. Selective Tyrosine Kinase 2 Inhibition for Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: New Hope on the Rise. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 2023–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, C.E.; Gooderham, M.; Beecker, J. TYK 2 Inhibitors for the Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions: The Evolution of JAK Inhibitors. Int. J. Dermatol. 2022, 61, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, R.P.S.; Gupta, A.; Kamarthi, N.; Malik, S.; Goel, S.; Gupta, S. Incidence of Oral Lichen Planus in Perimenopausal Women: A Cross-Sectional Study in Western Uttar Pradesh Population. J.-Life Health 2017, 8, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lavaee, F.; Bazrafkan, N.; Zarei, F.; Sardo, M.S. Follicular-Stimulating Hormone, Luteinizing Hormone, and Prolactin Serum Level in Patients with Oral Lichen Planus in Comparison to Healthy Population. BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 8679505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, A.; Kim, J.Y.; Kwak-Kim, J.; Lee, S.K. Menopause Is an Inflection Point of Age-Related Immune Changes in Women. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2021, 146, 103346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Authors, References and Publication Year | Cohort/Study Design | Number of ELP Cases | Further Manifestation Sites of LP | Macroscopic Findings as Described in the Manuscript | Histologic Findings as Described in the Manuscript | Symptoms | Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quispel [48] 2009 | 24 LP patients | 12 | oral and/or cutaneous (all) | whitish papules (10) hyperemic lesions (3) mucosal detachment (2) submucosal plaques (3) | lymphohistiocytic infiltrations para-/hyperkeratosis hyperplasia Civatte bodies glycogen acanthosis | dysphagia (4) odynophagia (3) heart burn (3) regurgitation (2) | |

| Katzka [33] 2010 | retrospective review (10 years) of data base/esophageal biopsies from patients with dysphagia | 27 (female 92%) | oral (19) genital (13) cutaneous (3) ELP as initial manifestation (13) | strictures (18) proximal (11), distal (3), both (4), mucosal detachment (11) erythema, plaques, whitish mucosa, superficial ulcerations Koebner effect after dilation | lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration damage of epithelial basal layer Civatte bodies squamous cell carcinoma (1) | dysphagia (27) odynophagia (2) | dilatation of strictures (17) prednisone (6) intralesional corticosteroids (2) swallowed fluticasone/budesonide (2) |

| Fox [50] 2011 | review of published ELP cases until 2009 (including 4 own cases) | 72 (female 87%) | oral (89%) genital (42%) cutaneous (38%) scalp (7%) nails (3%) eyes (1%) ELP as initial manifestation (14) | pseudomembranes, bleeding, fragility, inflammation

| Lichenoid lymphocytic infiltrates dysplasia/squamous cell carcinoma (6%) | dysphagia (81%) odynophagia (24%) weight loss (14%) heart burn regurgitation hoarseness asymptomatic (17%) | |

| Podboy [57] 2017 | retrospective analysis of a cohort of ELP-patients | 40 (female 80%) | cutaneous (4) oral (19 genital (15) ELP as only manifestation (13) | strictures (29) ring formation (29) ulcerations (8) mucosal detachment (6) other mucosal lesions (14) squamous cell carcinoma (2) | esophagitis (20) focal ulcerations (13) mucosal hyperplasia (10) intraepithelial lymphocytic infiltrate (13), eosinophilia (13) dyskeratosis (11) DIF in 20 cases: positive, lichenoid (2) equivocal (5) not evaluable because of mucosal detachment (13) | dysphagia for solid food (32) even for fluids (8) odynophagia (6) reflux (1) | topical corticosteroids

response rate: endoscopic (72.5%) clinical (62%) |

| Ravi [34] 2019 | retrospective analysis of ELP patients | 132 (female 80%) | “Clinical diagnosis” (77) | “Specific histology” (55) esophageal carcinoma (8) | response to topical steroids (84) immunosuppressive therapy (38) | ||

| Kern [52] 2016 Schauer [49] 2019 | 52 patients with proven LP on other site (♀ 75%) | 34

| oral 78–100% in ELP 78% in non-ELP) genital 44–61% in ELP 6% in non-ELP cutaneous 25–44% in ELP 28% in non-ELP | mucosal detachment

trachealization (10) stenosis/strictures (7) | epithelial detachment lymphocytic infiltration Civatte bodies dyskeratosis DIF: fibrinogen deposits (17) (85% in severe ELP) | dysphagia

| topical steroids (12)

|

| Aby [58] 2023 | Descriptive multicenter report | 78 ELP (female 86%) | Oral (14) Skin (6) Multisystemic (18) | Strictures (42) Denudation (39) Narrow caliber esophagus (21) | Not listed | Not mentioned | PPI alone Topical steroids Systemic steroids Intralesional steroids PPI + intralesional + topical steroids Immunosuppressors. |

| Diehl [55] 2025 | Prospective analysis of LP with dysphagia | 21 ELP (female 71%) | Oral (17) Genital (9) Nail (8), Hair (7) Skin (5), Anal (1), Eye (1) | Denudation (13) Hyperkeratosis (9) Trachealization (15) Stenosis (13) | Civatte bodies (7) Dyskeratosis (12) Epithelial detachment (7) Lymphocytic infiltrate (16) DIF: fibrinogen deposits (13) | Dysphagia Food bolus obstruction Heart burn | Not listed in detail |

| Decker [54] 2022 | Review | ||||||

| Jacobs [31] 2022 | Review | ||||||

| Blonski [59] 2023 | Review | ||||||

| Ghai [60] 2025 | Review |

| Macroscopic-endoscopic criteria | |

| Specific signs D Denudation/sloughing of the mucosa D1 Iatrogenic denudation (caused by biopsies) D2 Spontaneous localized denudation < 1 cm2 D3 Spontaneous spacious denudation > 1 cm2 | Possible signs S Stenosis/stricture S1 Passable with standard endoscope S2 Not passable with standard endoscope H Hyperkeratosis (whitish, rough mucosa) T Trachealization N None of the criteria fulfilled |

| Microscopic criteria—histopathology (HP) and direct immunofluorescence (F) | |

| HP Sloughing of the epithelia (subepithelial, intraepithelial) Lymphocytic infiltrate, mainly T-lymphocytes, subepithelial, intraepithelial, junctional (region of the basal membrane) Intraepithelial apoptosis of keratinocytes “Civatte bodies” Dyskeratosis HP0 negative HP1 weakly positive HP2 positive HP3 strong positive | F Fibrinogen deposits along the basal membrane F0 no visible reaction F1 weak positive, discrete deposits visible F2 marked fibrinogen deposits along the basal membrane |

| Grading | |

| Severe LP ≥D2 and HP ≥ 1 OR ≥D2 and F ≥ 1 Mild ELP D1 and HP ≥ 1 and/or F ≥ 1 OR S, H, T, N and HP ≥ 1 and F ≥ 1 No ELP Criteria not fulfilled in a patient with LP on other localization | |

| Chemical or physical damages Reflux esophagitis Chemical esophagitis (acids, leach) Radiation esophagitis Drug-induced esophagitis, e.g., NSAID, bisphosphonates, tetracyclines, KCl, ferric sulfate, ascorbic acid |

| Infectious esophagitis Candida spp. Viruses, e.g., Herpes simplex, CMV, HIV |

| Immune mediated esophagitis Eosinophilic esophagitis ELP Lymphocytic esophagitis Mucus membrane pemphigoid Pemphigus Lichenoid esophagitis Crohn’s disease GVHD Behçet’s disease Systemic sclerosis Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| Others Epidermolysis bullosa congenita or acquisita Esophageal intramural pseudodiverticulosis (EIPD) Sloughing esophagitis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kreisel, W.; Diehl, R.; Decker, A.; Lazaro, A.; Schauer, F.; Schmitt-Graeff, A. Esophageal Lichen Planus—Contemporary Insights and Emerging Trends. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112621

Kreisel W, Diehl R, Decker A, Lazaro A, Schauer F, Schmitt-Graeff A. Esophageal Lichen Planus—Contemporary Insights and Emerging Trends. Biomedicines. 2025; 13(11):2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112621

Chicago/Turabian StyleKreisel, Wolfgang, Rebecca Diehl, Annegrit Decker, Adhara Lazaro, Franziska Schauer, and Annette Schmitt-Graeff. 2025. "Esophageal Lichen Planus—Contemporary Insights and Emerging Trends" Biomedicines 13, no. 11: 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112621

APA StyleKreisel, W., Diehl, R., Decker, A., Lazaro, A., Schauer, F., & Schmitt-Graeff, A. (2025). Esophageal Lichen Planus—Contemporary Insights and Emerging Trends. Biomedicines, 13(11), 2621. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13112621