Abstract

Chemerin, encoded by the RARRES2 gene, is an adipokine with potent immunometabolic functions mediated through CMKLR1, GPR1, and CCRL2. Its regulation is tissue- and context-dependent, conferring dual protective and pathogenic roles. In the upper GI tract, chemerin facilitates immune tolerance in Barrett’s adenocarcinoma and promotes invasion in esophageal and gastric cancers. In pancreatic disease, it acts as a biomarker of acute and chronic injury, while modulating β-cell function and carcinogenesis. In the liver, chemerin contributes to NAFLD/NASH pathogenesis with both anti-inflammatory and pro-steatotic actions, predicts prognosis in cirrhosis, and demonstrates tumor-suppressive potential in hepatocellular carcinoma. In IBD, chemerin exacerbates colitis via impaired macrophage polarization, yet protects epithelial antimicrobial defense, underscoring its context-specific biology. Collectively, these findings position chemerin as a versatile regulator bridging metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, and gastrointestinal malignancy, and as a potential candidate for biomarker development and therapeutic intervention.

1. Introduction

Adipokines are essential mediators that connect metabolic regulation with inflammatory and immune pathways. Among them, chemerin, encoded by RARRES2, has attracted increasing attention for its diverse biological actions. Through its receptors CMKLR1, GPR1, and CCRL2, chemerin influences glucose and lipid metabolism, immune cell recruitment, and tissue remodeling [1]. Its broad tissue distribution, including adipose tissue, liver, and lymphoid organs, positions it as a crucial link between metabolic and inflammatory processes [2]. Chemerin exhibits a context-dependent duality, acting as either an anti-inflammatory or proinflammatory factor depending on physiological and pathological conditions. Elevated circulating levels have been reported in various inflammatory disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and cancers [3,4,5,6], yet its functional outcomes appear highly variable and disease specific.

Within the gastrointestinal tract, adipokines play an important role in maintaining mucosal homeostasis and immune equilibrium [7]. Dysregulated chemerin expression and signaling have been implicated in several gastrointestinal disorders, including chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and malignancy [8,9,10]. However, most studies have focused on individual organs or disease contexts, resulting in a fragmented understanding of chemerin’s overall role in gastrointestinal physiology and pathology.

This review provides a comprehensive and integrative overview of chemerin in gastrointestinal diseases, emphasizing its molecular mechanisms, clinical relevance, and therapeutic potential. By synthesizing findings from experimental and clinical research, it advances beyond existing literature to present chemerin as a dynamic immunometabolic regulator whose context-dependent actions shape gastrointestinal inflammation, tissue repair, and carcinogenesis.

2. Chemerin Biology and Receptor Signaling

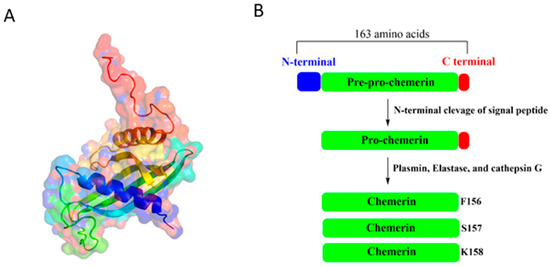

Chemerin, a 137-amino-acid protein encoded by the retinoic acid receptor responder 2 (RARRES2) gene (Figure 1A), is initially synthesized as the 163-amino-acid inactive precursor pre-pro-chemerin [11,12]. This precursor undergoes proteolytic processing, which involves the removal of the N-terminal signal peptide, to produce pro-chemerin with low bioactivity [13]. On the other hand, the removal of the amino acids within the C-terminal segment by plasmin, elastase, and cathepsin G activates chemerin and generates multiple isoforms, including chemerin-K158 (low activity), chemerin-S157 (highest activity), and chemerin-F156 (high activity) (Figure 1B), each exhibiting distinct binding affinities for chemerin receptors [11,14]. Given the crucial role of C-terminal proteolytic processing in regulating chemerin activity, several synthetic peptides, including chemerin-9, chemerin-13 [15], chemerin-15 [16], chemerin-20 [17], chemerin peptide analog CG34 [18], and cyclic peptide-9 [19], have been shown to exhibit bioactivity in various model systems, suggesting their potential utility for experimental or clinical applications.

Figure 1.

(A) 3D structure of chemerin (PDB ID: 8XGM) and (B) proteolytic processing of pre-pro-chemerin.

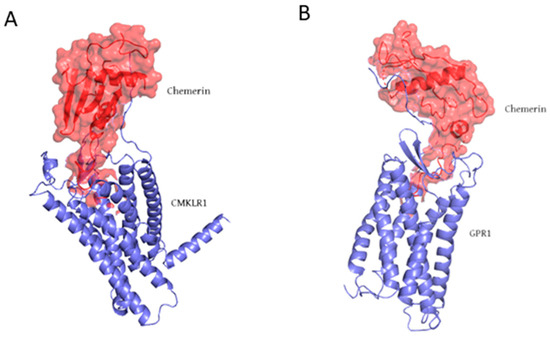

In addition to white adipose tissue and skin, chemerin is abundantly expressed in the lungs, liver, and colon, while lower levels of expression are observed in the small intestine. Circulating chemerin levels are positively correlated with proinflammatory markers, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and C-reactive protein (CRP), suggesting its role as a proinflammatory mediator [13,20]. Aside from its chemotactic function, chemerin, as an adipokine, is strongly linked to adipocyte differentiation, with loss of chemerin expression impairing adipogenesis. The complexity of chemerin biology arises in part from the presence of multiple protein isoforms exhibiting distinct bioactivities within both systemic circulation and local tissue environments. Chemerin exerts its biological effects by interacting with C-C chemokine receptor-like 2 (CCRL2), chemokine-like receptor 1 (CMKLR1) (Figure 2A), and G protein-coupled receptor 1 (GPR1) (Figure 2B) [21,22,23]. CMKLR1, also known as ChemR23, is widely expressed in adipose tissue, as well as in immune and endothelial cells [24]. Interaction with chemerin initiates several intracellular signaling pathways, including Ca2+ mobilization, inhibition of cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) production, and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) such as p42/p44 and p38. These downstream events induce a range of cellular responses, most notably chemotaxis, adipogenesis, and regulation of inflammatory pathways, and play a critical role in regulating diverse immunometabolic processes [25,26]. Consequently, this signaling pathway represents an attractive target for novel pharmacological interventions, with multiple candidate drugs already identified and progressing through various stages of clinical development [23].

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of (A) chemerin-CMKLR1 complex (PDB ID: 8ZJG) and (B) chemerin-GPR1 complex (PDB ID: 9L3Y). Chemerin is shown as a red surface, while CMKLR1 and GPR1 are shown in purple.

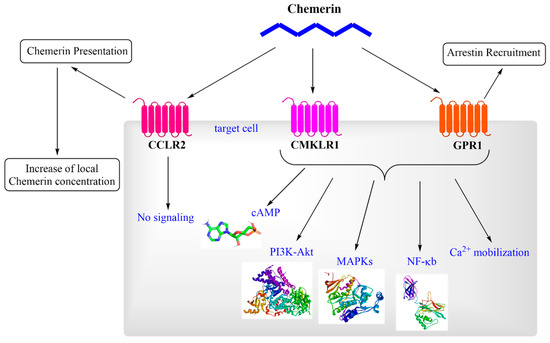

In contrast, CCRL2 functions as a non-signaling “decoy” receptor, binding chemerin without triggering downstream signaling events. Specifically, CCRL2 facilitates the presentation of chemerin to neighboring CMKLR1-expressing cells, thereby increasing local chemerin availability and amplifying CMKLR1-dependent responses [26]. CCRL2 is expressed in leukocytes, endothelial cells, and various other immune cell types, highlighting its role in modulating chemerin activity during inflammatory responses [27]. GPR1 shares structural homology with CMKLR1, but exhibits distinct functional properties. Although GPR1 binds chemerin with high affinity, it elicits only minimal Ca2+ mobilization compared to CMKLR1. Instead of classical G protein-dependent signaling, GPR1 primarily engages arrestin-mediated pathways. This mechanism leads to prolonged cellular outcomes such as receptor internalization and activation of alternative cascades, including MAPKs, which regulate long-term cellular functions. GPR1 expression is most prominent in the central nervous system and selected peripheral tissues, suggesting potential roles in neuroendocrine regulation and metabolic control. Although its precise physiological and pathological significance remains to be fully elucidated, the unique expression profile of GPR1 indicates functions distinct from those of CMKLR1 and CCRL2 [26,28,29]. Figure 3 provides a summarized overview of chemerin signaling, illustrating its interactions with receptors and downstream effects.

Figure 3.

Molecular pathways activated by chemerin. The abbreviations are as follows: CCRL2 (C-C chemokine receptor-like 2), CMKLR1 (chemokine-like receptor 1), GPR1 (G protein-coupled receptor 1), MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), cAMP (cyclic adenosine monophosphate), NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells), and PI3K-Akt (phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-Akt).

3. Chemerin in the Upper Gastrointestinal Tract

3.1. Chemerin in Esophageal Pathology

Chemerin expression is detectable in healthy esophageal epithelium, where it may function as a rapid-response mediator for the recruitment of effector immune cells, paralleling its role in other barrier tissues [30]. In disease states, chemerin expression is dynamically regulated and exerts a pivotal influence on esophageal pathology. In esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, chemerin acts as a stromal factor overexpressed by cancer-associated myofibroblasts, recruiting CMKLR1-expressing mesenchymal stromal cells to the tumor microenvironment, thereby fostering a pro-invasive and pro-angiogenic stroma [31]. Additionally, chemerin-stimulated mesenchymal stromal cells display enhanced secretion and adhesion, which in turn augments myofibroblast adhesion, migration, and proliferation [32]. Moreover, both patient-derived and commercial (OE21) esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cell lines express CMKLR1, and chemerin secreted by cancer-associated myofibroblasts drives their migration, invasion, and proliferation. It was further demonstrated that in the OE21 cell line, chemerin enhances invasion by inducing matrix metalloproteinase activity through PKC and MAPK activation. Notably, inhibiting chemerin actions through neutralization, small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown, or ChemR23 antagonism (CCX832) reduces invasion in both Boyden chamber and organotypic models, underscoring chemerin’s direct role in promoting tumor aggressiveness [33].

Regarding its role in esophageal adenocarcinoma, chemerin expression increases progressively from metaplastic to dysplastic and invasive stages during the transition from Barrett’s esophagus to adenocarcinoma, likely serving as a chemoattractant for myeloid dendritic cells that drive regulatory T-cell differentiation and suppress anti-tumor immunity, thereby facilitating malignant progression [30]. In patients with esophageal cancer and metabolic syndrome, an expedited surgical protocol was associated with greater reductions in circulating chemerin levels than the standard protocol, alongside decreases in inflammatory markers such as TNF-α, high-sensitivity CRP, and leptin; these changes coincided with improved lipid metabolism, nutritional recovery, and quality-of-life scores [34].

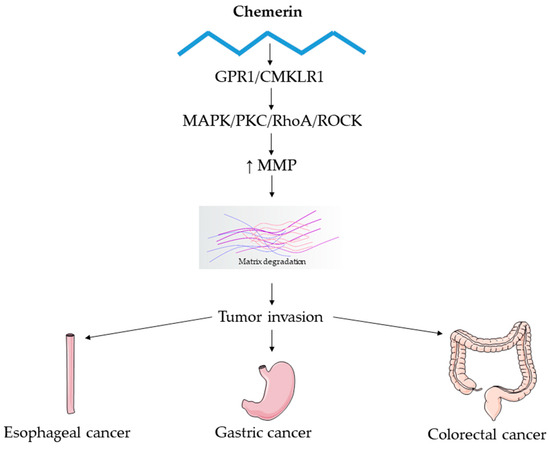

Overall, available data suggest that chemerin plays an aggressive role in esophageal cancer pathology (Figure 4). However, evidence is very scarce, primarily derived from in vitro studies and a single patient cohort, and further mechanistic and translational research is needed to clarify its receptor-specific effects and clinical relevance.

Figure 4.

Shared molecular mechanisms in esophageal, gastric, and colorectal cancers associated with chemerin signaling. This figure illustrates the shared molecular mechanisms underlying esophageal, gastric, and colorectal carcinogenesis, emphasizing the role of chemerin-mediated modulation of MMPs and their contribution to extracellular matrix degradation, tissue remodeling, and tumor invasion.

3.2. Chemerin in Gastric Pathology

Gastric cancer continues to be a significant global health issue, with nearly one million new diagnoses each year and over 650,000 deaths attributed to the disease. Recognized risk factors encompass Helicobacter pylori infection, dietary patterns, obesity, smoking, and genetic factors, highlighting the complex nature of gastric cancer development [35]. Adipokines are recognized as important modulators of gastric physiology and pathology, influencing metabolic signaling, mucosal inflammation, and tumor progression within the stomach [7]. Early evidence from Wang et al. [36] demonstrated elevated serum chemerin levels in gastric cancer patients (n = 36), detectable even at early stages and further increased in advanced and non-intestinal subtypes. In a larger cohort (n = 196), Zhang et al. [37] confirmed significantly higher preoperative plasma chemerin concentrations in gastric cancer patients compared with healthy controls, correlating with tumor stage, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, peritoneal spread, and poor prognosis. Chemerin was further identified as an independent prognostic marker for both overall and disease-free survival, showing strong predictive power for 5-year outcomes.

These clinical observations prompted further mechanistic studies demonstrating that chemerin promotes epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), migration, and invasion of gastric adenocarcinoma (AGS) cell lines via both GPR1 and CMKLR1, through activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), Ras homolog family member A/Rho-associated protein kinase (RhoA/ROCK), and protein kinase C (PKC) signaling pathways. This signaling cascade upregulates vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7), and interleukin-6 (IL-6), while downregulating tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases-1 and -2 (TIMP-1 and TIMP-2), thereby enhancing matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity and extracellular matrix degradation [36,38,39]. These effects occur without influencing cell proliferation, underscoring chemerin’s role as a key driver of invasiveness in gastric cancer. Moreover, Kumar et al. [39] identified cancer-associated myofibroblasts as the main source of chemerin within the gastric cancer microenvironment, confirming their own findings in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, where these cells were likewise shown to represent the principal chemerin source.

Furthermore, H. pylori infection has been shown to increase chemerin expression in gastric epithelial cell lines (KATO III and AGS) and to elevate its expression in gastric tissue from patients with chronic ulcers, suggesting that infection-driven inflammation may potentiate chemerin-mediated tumorigenic signaling [40].

However, the current evidence remains limited. Most findings derive from a small number of in vitro studies, without further replication or expansion of the proposed mechanisms, and lack in vivo validation. Clinical data are also restricted to single measurements, without evaluation of postoperative or longitudinal changes. Future large-scale, mechanistically integrated, and reproducible studies are essential to confirm chemerin’s biological significance, prognostic value, and therapeutic potential in gastric cancer.

4. Chemerin in Pancreas Pathology

Chemerin and its receptor CMKLR1 are expressed in adipose tissue, immune cells, and pancreatic β-cells, linking metabolic and inflammatory pathways to pancreatic physiology [41]. In clinical settings, elevated pre-procedural chemerin, together with insulin resistance, independently predicted the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis [42], suggesting that endogenous chemerin elevation reflects metabolic-inflammatory susceptibility, likely driven by adipose-derived inflammation. Similarly, Yin et al. [43] found higher serum chemerin levels in hyperlipidemia-induced pancreatitis, correlating with disease severity and suggesting its role as a biomarker of inflammatory burden. In contrast, in a rat model of caerulein-induced pancreatitis, chemerin pre-administration markedly reduced pancreatic injury, decreasing edema, serum amylase, and TNF-α levels. In vitro, it suppressed TNF-α expression and shifted NF-κB signaling toward non-canonical p50/p50/Bcl-3 complexes, limiting proinflammatory gene transcription [44]. Notably, these findings indicate that chemerin’s function is context-dependent: endogenous elevation reflects a predisposed and reactive metabolic–inflammatory state, whereas controlled exogenous activation exerts anti-inflammatory and cytoprotective effects. It cannot be excluded that this endogenous rise also represents a counter-regulatory or compensatory mechanism aimed at limiting excessive tissue injury, which would be consistent with experimental observations. Differences in timing, source (endogenous vs. exogenous), and study model (clinical vs. experimental) likely account for these divergent outcomes.

Regarding chemerin’s role in chronic pancreatitis, Adrych et al. [45] first reported increased serum chemerin levels in patients with chronic pancreatitis, independent of diabetes or BMI reduction, suggesting that chemerin reflects local inflammatory and fibrogenic activity rather than adiposity. Its correlation with profibrotic cytokines such as PDGF-BB and TGF-β1 supports a role in pancreatic stellate cell activation and fibrosis progression. Kiczmer et al. [46] confirmed persistent chemerin elevation in chronic pancreatitis and markedly elevated levels in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, with concentrations unrelated to BMI, implying disease-specific regulation. Mechanistically, chemerin may promote angiogenesis and stromal remodeling through CMKLR1-dependent MAPK/AKT signaling. Conversely, Tu et al. [47] found markedly reduced chemerin levels in pancreatogenic diabetes (type 3c), associated with β-cell dysfunction and reduced GLUT2 and PDX1 expression. Pharmacological CMKLR1 activation with the chemerin-9 agonist restored β-cell transcriptional programs and improved glucose tolerance.

Together, these findings highlight chemerin’s context-dependent duality: elevated in chronic inflammatory and neoplastic states, potentially reflecting reactive or compensatory fibrogenic activity, but decreased in advanced endocrine failure, where its deficiency becomes maladaptive (Table 1). Variability in disease stage, cellular source, and study design likely accounts for these discrepancies. However, current evidence remains limited. Most studies rely on small cohorts or in vitro and short-term experimental models, without serial measurements or receptor-level characterization. Future research should include longitudinal human studies to determine whether dynamic changes in chemerin levels parallel disease progression or resolution and to clarify whether chemerin acts predominantly as a marker of disease severity or a modulator of protective immune regulation in pancreatic diseases.

Table 1.

Key studies on chemerin in pancreatic pathology.

5. Chemerin in Liver Diseases

5.1. Chemerin and Fatty Liver Disease

5.1.1. Experimental Data

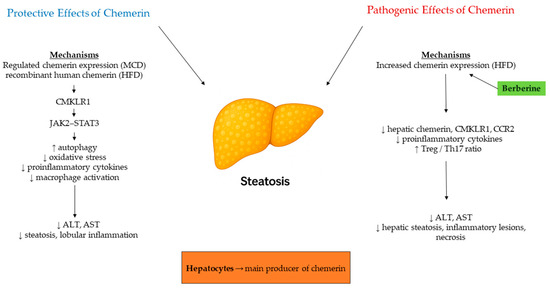

Chemerin is an adipokine that plays a significant role in the differentiation of adipocytes, the maintenance of glucose levels, and the regulation of inflammation [48]. Its strong connection to obesity and metabolic syndrome, two major risk factors for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), has established chemerin as a possible biomarker and mediator in the mechanisms behind NAFLD and its advanced form, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) [49]. The recent shift in terminology from NAFLD to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) has sharpened the focus on the metabolic factors underlying the condition, further emphasizing the importance of adipokines, such as chemerin [50,51]. Experimental models have provided essential insights into the complex role of chemerin in the development of fatty liver disease. Experimental evidence establishes hepatocytes as the principal hepatic source of chemerin, displaying markedly higher expression than other liver cell types. In human NAFLD and NASH, hepatic chemerin mRNA is consistently elevated, although corresponding protein levels show variable patterns, suggesting post-transcriptional regulation. In mouse models, diet-dependent differences were observed: the high-fat diet and ob/ob mice, which model simple hepatic steatosis, showed increased hepatic chemerin mRNA expression, while the Paigen and methionine–choline-deficient (MCD) diets, both inducing NASH with inflammation and fibrosis, led to increased hepatic and, partially, circulating chemerin [52]. Functionally, hepatocyte-specific chemerin overexpression in MCD-fed mice increased hepatic and serum chemerin but attenuated oxidative stress and macrophage-driven inflammation, reducing IL-6, CCL2, and osteopontin production [49]. Similarly, recombinant human chemerin treatment in high-fat diet mice alleviated steatosis and inflammation, improved insulin sensitivity, and decreased ALT/AST levels via CMKLR1-dependent JAK2–STAT3 activation, which enhanced autophagy and reduced oxidative stress [53,54]. In contrast, treatment with berberine notably improved NAS scores and diminished hepatocellular injury in rats with HFD-induced NASH. Simultaneously, it downregulated hepatic expression of chemerin, CMKLR1, and CCR2, while reducing proinflammatory cytokines. Beyond the hepatocellular benefits, berberine also reestablished the Treg/Th17 balance, indicating that chemerin/CMKLR1 signaling potentially plays a role in modulating both innate immunity and inflammation, as well as reshaping adaptive immune balance within the hepatic microenvironment [55]. Collectively, these experimental results emphasize the dual nature of chemerin in NAFLD/NASH (Figure 5). When properly regulated, chemerin exhibits hepatoprotective effects by suppressing inflammation, promoting autophagy, and reducing oxidative stress. Conversely, in proinflammatory metabolic conditions, excessive chemerin/CMKLR1 activity may exacerbate steatohepatitis, and its inhibition, as demonstrated by berberine, can yield beneficial effects. This context-sensitive behavior highlights the complexity of chemerin as a potential therapeutic target and a biomarker for disease stratification.

Figure 5.

Chemerin in experimental NAFLD/NASH. Hepatocytes are the main hepatic source, with increased expression under steatotic and inflammatory conditions. Experimental models show that balanced chemerin/CMKLR1 signaling reduces inflammation, oxidative stress, and improves insulin sensitivity, whereas berberine administration attenuates hepatic steatosis and necrosis by reducing chemerin, CMKLR1, and CCR2 expression. Arrows indicate direction of change (↑ increase, ↓ decrease).

5.1.2. Clinical Data

Clinical evidence consistently supports a link between circulating chemerin and systemic metabolic dysfunction. Elevated chemerin levels correlate with BMI, total body fat, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose metabolism, aligning with its proposed role as a biomarker of metabolic imbalance in NAFLD [51]. Multiple studies show increased serum chemerin in NAFLD and particularly in NASH, where it associates more closely with hepatocellular injury and inflammation than with fibrosis [56,57]. Therapeutic interventions such as L-carnitine and metformin have been shown to reduce chemerin levels alongside improvements in liver enzymes and insulin sensitivity, further reinforcing this metabolic association [58,59]. Moreover, in diabetic cohorts, Zhang et al. [60] identified chemerin as an independent risk factor for NAFLD, with levels increasing in parallel with steatosis severity and closely associated with obesity, dyslipidemia, and HOMA-IR. Comprehensive population-based research by Levin et al. [61] demonstrated strong associations between chemerin and hepatic steatosis, as measured by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), revealing a linear relationship in men and a U-shaped pattern in women, unaffected by other health complications.

At the tissue level, chemerin regulation shows considerable heterogeneity. Pohl et al. [62] reported reduced hepatic chemerin mRNA in NASH, inversely correlated with inflammation and fibrosis, indicating an extrahepatic source of circulating chemerin. Kajor et al. [63] further demonstrated that adipose tissue, rather than the liver, is the main contributor to systemic chemerin in morbid obesity. Similarly, Bekaert et al. [64] observed that lower chemerin expression in visceral adipose tissue was inversely associated with steatosis and NAFLD activity, suggesting impaired adipose–liver signaling in metabolic dysfunction. Together, these findings emphasize the tissue-specific and context-dependent regulation of chemerin and highlight the importance of considering adipose contributions when evaluating its role in metabolic liver disease. A recent meta-analysis confirms that circulating chemerin is elevated in MAFLD and NAFLD but not consistently in NASH, indicating that chemerin reflects metabolic dysfunction and steatosis more reliably than histological severity [65].

Collectively, these findings (Table 2) identify serum chemerin as a potential biomarker of metabolic dysfunction and hepatic steatosis, while its relationship with histological severity remains inconsistent. However, a key limitation across clinical studies is the discrepancy between elevated circulating chemerin and reduced hepatic expression reported in some tissue analyses. This divergence suggests that circulating chemerin may primarily originate from adipose tissue rather than the liver, reflecting systemic rather than hepatic metabolic activity.

Table 2.

Clinical Studies on Chemerin and MAFLD/NAFLD/NASH.

5.2. Chemerin in Liver Cirrhosis

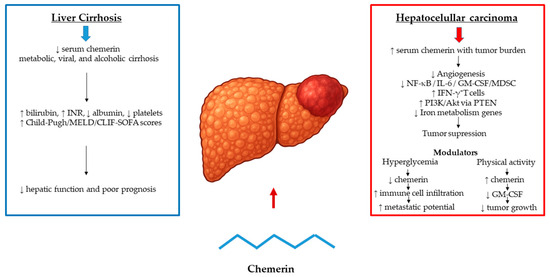

Chemerin, an adipokine with key immunometabolic functions, is mainly produced in the liver and adipose tissue and has been increasingly investigated as an indicator of hepatic functional status in cirrhosis. Early clinical investigations by Eisinger et al. [66] demonstrated that hepatic chemerin secretion declines with worsening liver function, with serum levels decreasing across Child–Pugh classes and reaching their lowest in Child C patients. This reduction reflected impaired coagulation rather than hepatic gene expression, indicating that circulating chemerin mirrors residual hepatic function rather than synthetic capacity alone. Horn et al. [67] further showed that low chemerin levels in decompensated cirrhosis correlate with bilirubin, albumin, INR, platelet count, and disease severity scores (Child–Pugh, MELD, CLIF-SOFA), with concentrations below 87 ng/mL independently predicting 28-day mortality or transplantation. Similarly, Peschel et al. [68] reported that chemerin correlates with hepatic dysfunction and fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C, independent of viral load or genotype, and remains unchanged after antiviral therapy, again reflecting liver function rather than viral activity. In alcoholic cirrhosis, Prystupa et al. [69] confirmed a progressive decline across Child–Pugh stages, strongly linked to bilirubin, INR, and albumin. Collectively, these studies identify low circulating chemerin as a consistent feature of advanced cirrhosis, reflecting hepatic dysfunction and portal hypertension, and suggesting potential, but still preliminary utility for risk assessment in end-stage liver disease (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Chemerin at the Crossroads of Cirrhosis and HCC. Chemerin levels decline with cirrhosis severity, correlating with impaired hepatic function and predicting short-term mortality. In HCC, circulating chemerin paradoxically rise with tumor burden supporting tumor-suppressive roles. Arrows indicate direction of change (↑ increase, ↓ decrease).

5.3. Chemerin in Liver Cancer

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the most common primary liver cancer, typically develops in cirrhotic livers and remains a major cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [70]. Among various adipokines implicated in hepatocarcinogenesis, chemerin has attracted attention due to its immunometabolic, angiogenic, and metabolic regulatory roles [71,72]. Yet, its function in HCC appears to be context-dependent. Circulating chemerin levels are reduced in cirrhosis and decline with worsening hepatic function, but paradoxically increase with tumor burden in HCC, sometimes approaching concentrations seen in healthy controls—likely reflecting compensatory release from non-tumorous tissue. [70]. Moreover, in the NASH-related HCC mouse model, chemerin expression and receptor activation remain unchanged between tumor-bearing and control groups, despite the presence of liver tumors suggesting that high endogenous chemerin is not sufficient to prevent hepatocarcinogenesis [73]. Overexpression of the active chemerin-156 isoform reduced the number of small lesions but failed to limit established tumor growth or alter inflammatory and fibrotic gene expression [49]. Similarly, in diabetic HCC models, hyperglycemia-induced suppression of chemerin was linked to a more immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, reduced immune cell infiltration, and enhanced metastatic potential [74].

Conversely, growing evidence supports a tumor-suppressive role for chemerin, particularly in early tumorigenesis. Lower serum and intratumoral chemerin levels in HCC patients correlate with poorer prognosis [70], while chemerin overexpression in mice inhibits angiogenesis, enhances immune activation, and suppresses NF-κB, IL-6, and GM-CSF signaling, leading to reduced myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation and increased IFN-γ–producing T cells [75,76]. Chemerin also modulates PI3K/Akt signaling via PTEN-dependent inhibition [77,78] and induces cell-cycle arrest in hepatoma cells through downregulation of iron metabolism genes and activation of the p53/p27/p21 axis [79]. These findings suggest that chemerin interferes with multiple tumor-promoting mechanisms, including proliferation, angiogenesis, and immune evasion. The heterogeneity of these findings likely reflects differences in disease etiology and population characteristics. While decreased chemerin levels have been reported in HBV-associated HCC in Asian cohorts, increased expression in NAFLD-related and idiopathic HCC has been noted in European studies, despite consistent CMKLR1 downregulation across tumor types, potentially limiting downstream signaling [80]. Environmental and systemic factors further influence this axis; for example, voluntary exercise enhances chemerin secretion from brown adipose tissue, reducing tumor growth through GM-CSF suppression and antiproliferative effects in HCC models [81]. Notably, in HCC, but not in colorectal cancer liver metastasis, adiponectin correlated with chemerin levels, suggesting a liver-specific pathogenic role [82].

Collectively, these observations suggest that chemerin exerts multifaceted, context-dependent effects in hepatocarcinogenesis, intersecting metabolic, immune, and angiogenic pathways, while its clinical utility remains to be fully defined.

6. Chemerin in Lower Gastrointestinal Tract Pathology

6.1. Chemerin in IBD

6.1.1. Experimental Data

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), encompassing Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic intestinal disorder driven by genetic, microbial, environmental, and immune factors [83]. Visceral adipose tissue actively contributes to mucosal inflammation through adipokine release, positioning chemerin as a potential immunometabolic mediator in IBD [6,84,85]. In dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced colitis, exogenous chemerin aggravated disease severity, causing greater weight loss, mucosal damage, and mortality, while elevating IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ levels. Mechanistically, chemerin disrupted IL-4/STAT6-dependent M2 macrophage polarization, reducing Arg-1, Ym1, FIZZ1, and IL-10 expression and impairing inflammation resolution. Neutralizing chemerin improved mucosal healing, underscoring its pathogenic contribution [86]. Chemerin and its receptor CMKLR1 are upregulated in colitis, particularly in the distal colon, with bioactive chemerin levels remaining high despite overall serum decline. CMKLR1-deficient mice displayed delayed disease onset and altered cytokine responses, but the final severity of the disease was comparable, suggesting that chemerin signaling primarily influences early inflammation rather than disease progression [87]. Therapeutic inhibition of chemerin, such as with cornelian cherry extract, attenuated trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) colitis by reducing TNF-α, IL-17, and chemerin, strengthening epithelial barrier integrity and limiting pathogenic E. coli [88]. Conversely, chemerin appears protective at the epithelial level: its absence, or loss of CMKLR1, increases susceptibility to neutrophilic colitis and colitis-associated cancer by downregulating lactoperoxidase (LPO), an enzyme essential for microbial control. Restoration of LPO reverses this phenotype, highlighting the chemerin-CMKLR1-LPO axis in mucosal defense [89].

Collectively, these insights position chemerin as a regulator that exerts context-dependent effects in experimental IBD: harmful when it obstructs macrophage-mediated inflammation resolution, but beneficial when it supports epithelial antimicrobial activity and microbial stability. This complexity underscores the potential of chemerin as both a marker of disease activity and a therapeutic target.

6.1.2. Clinical Data

Although research on chemerin in IBD remains limited, current evidence indicates dysregulated expression with possible clinical relevance. Weigert et al. [90] first reported elevated serum chemerin levels in both Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, particularly among men with Crohn’s disease, with gender-specific links to disease activity and duration. In contrast, Waluga et al. [91] found no significant differences compared to controls, suggesting heterogeneity across cohorts. Subsequent studies provided functional context: Terzoudis et al. [92] associated higher serum chemerin with osteoporosis in IBD, implying a role in extraintestinal metabolic complications, while Sochal et al. [93] observed increased levels during active disease, especially in ulcerative colitis, and normalization following anti-TNF therapy, suggesting responsiveness to inflammatory control. Beyond serum findings, Gunawan et al. [94] detected measurable urinary chemerin, markedly elevated in patients with high fecal calprotectin, introducing a potential noninvasive indicator of intestinal inflammation. A recent meta-analysis including 2717 participants (799 with Crohn’s disease, 520 with ulcerative colitis, and 609 healthy controls) demonstrated that circulating chemerin levels are significantly elevated in inflammatory bowel disease, especially during active phases. Based on these results, chemerin has been proposed as a potential biomarker for the diagnosis and monitoring of disease activity, reflecting its involvement in intestinal immune regulation and chronic inflammation [8].

Collectively, these studies highlight chemerin’s inconsistent systemic behavior but suggest its potential utility in reflecting disease activity, therapeutic response, and metabolic comorbidity in IBD.

6.2. Chemerin and Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a prevalent functional gastrointestinal disorder marked by recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, affecting up to 10% of the population. Its pathophysiology involves gut–brain axis dysregulation, microbial imbalance, immune alterations, and psychosocial stressors [95]. Increasing evidence also links IBS to metabolic syndrome, suggesting overlapping metabolic and inflammatory pathways [96]. Given chemerin’s established role in metabolic dysfunction [6], it has been proposed as a potential mediator connecting metabolic and intestinal disturbances, though dedicated research remains scarce. Recent studies have begun to explore this association. Baram et al. [97] reported elevated circulating chemerin levels in adults with IBS, particularly in diarrhea-predominant cases, correlating with symptom severity, abdominal pain, bloating, and psychosocial stress. Similarly, Roczniak et al. [98] found higher serum chemerin and lower omentin-1 in children with IBS, a pattern linked to insulin resistance and dyslipidemia, which persisted after metabolic adjustment. Notably, chemerin levels above 232.8 ng/mL demonstrated limited sensitivity (39%) but high specificity (87%) for distinguishing IBS patients from healthy individuals.

Collectively, these findings (Table 3) suggest that chemerin may represent a functional link between metabolic imbalance and intestinal dysregulation in IBS, with potential relevance for disease characterization rather than established diagnostic use. Further longitudinal studies are needed to clarify its mechanistic and clinical implications.

Table 3.

Clinical studies investigating chemerin in IBD and IBS.

6.3. Chemerin in Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

Worldwide, CRC represents one of the most prevalent cancers and remains a leading cause of cancer-associated mortality [99]. Growing evidence suggests that chemerin has a complex role in colorectal carcinogenesis, influencing early adenoma development, cancer risk, disease progression, and survival outcomes. In a case–control study, Yagi et al. [100] reported higher serum chemerin levels in men with colorectal adenomas, identifying it as an independent predictor of adenoma presence, while the EPIC-Potsdam cohort linked elevated baseline chemerin with an increased risk of colorectal cancer, particularly in the proximal colon, independent of BMI and inflammatory markers [101]. These findings suggest that chemerin may contribute to the adenoma-carcinoma sequence and CRC susceptibility.

In established disease, circulating chemerin is consistently elevated and correlates with TNM stage, CRP, CEA, CA19-9, and fibrinogen, reflecting both tumor burden and systemic inflammation [102,103]. Although early clinical studies suggested high diagnostic accuracy, these estimates likely overstate its predictive capacity. Beyond diagnosis, elevated chemerin in CRC survivors has been associated with greater fatigue and reduced quality of life [104], supporting its role as a marker of persistent systemic inflammation. Importantly, Waniczek et al. [105] extended these findings to saliva, demonstrating markedly elevated salivary chemerin levels in CRC patients with 99% specificity and 100% sensitivity at a cut-off of 231.24 ng/mL, though the small sample size limited the analysis and requires independent validation.

Mechanistically, recent studies reveal that chemerin modulates tumor angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling, and immune interactions. Increased CMKLR1 and MMP-9 expression in tumor tissue, along with links to VCAM-1, indicate that chemerin facilitates angiogenic and matrix-remodeling processes [106]. Kiczmer et al. further demonstrated that higher CMKLR1 expression is associated with lower vascularity and reduced tumor budding, implying that CMKLR1 may have a multifaceted role in colorectal cancer pathogenesis by regulating tumor architecture and shaping peritumoral immune infiltration [107]. Experimental activation of CMKLR1 with the chemerin analog CG34 enhanced colony formation, vascularization, and tumor growth in CRC models [18], while genetic and epigenetic analyses identified chemerin-associated regulatory loci within known CRC susceptibility regions [108]. Integrating single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, Qi et al. [109] uncovered a chemerin-mediated interaction between FAP+ fibroblasts and SPP1+ macrophages, fostering a desmoplastic, immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment linked to T-cell exclusion, poor survival, and resistance to anti–PD-L1 therapy.

Overall, available evidence indicates that chemerin-CMKLR1 signaling is involved in multiple stages of colorectal carcinogenesis (Figure 4), linking metabolic, inflammatory, and stromal pathways. However, its precise clinical relevance and therapeutic implications remain to be fully clarified.

7. Research Gaps and Future Perspectives

Although chemerin has been increasingly recognized as an important regulator of gastrointestinal physiology and pathology, several critical research gaps persist. Most existing evidence is derived from observational or in vitro studies, while mechanistic in vivo, longitudinal, and organ-specific models capable of clarifying receptor-dependent pathways across different regions of the gastrointestinal tract remain limited. The isoform-dependent activity of chemerin and its distinct signaling through CMKLR1, GPR1, and CCRL2 receptors [11,14] are still poorly characterized. Furthermore, the temporal and spatial dynamics of chemerin expression during the transition from acute to chronic inflammation, and ultimately to malignancy, have not been systematically investigated.

The relative contributions of circulating versus tissue-specific chemerin also remain unclear, particularly regarding its diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive value for disease activity and therapeutic response. Moreover, the lack of standardization in chemerin measurement methodologies, including variability in assay types, sample sources, and detection thresholds, limits the comparability of results across studies and hampers reliable biomarker validation. Importantly, many available studies have not adequately controlled for the confounding influence of obesity, a major determinant of circulating chemerin levels and a well-established risk factor for gastrointestinal disorders, which may obscure true disease-specific associations. Additionally, the interaction between chemerin and the gut microbiota remains largely unexplored, despite growing evidence that microbial metabolites can modulate adipokine signaling and mucosal immune responses [110].

Although chemerin and its receptors have been extensively implicated in inflammation, metabolic regulation, and tissue homeostasis [4], pharmacological manipulation of this axis remains in its infancy. The field still lacks clinically tested agonists or antagonists capable of selectively modulating chemerin signaling in humans. Most current data originate from preclinical studies employing peptide mimetics (e.g., chemerin-9, CG34) [47,107] or experimental small-molecule CMKLR1 (ChemR23) inhibitors (e.g., CCX832) [33], whose stability, receptor selectivity, and pharmacokinetic profiles remain suboptimal. Moreover, the dual and context-dependent role of chemerin adds further complexity to therapeutic targeting. Recent advances, including the resolution of the CMKLR1 crystal structure [23,111] and the development of agonistic monoclonal antibodies (e.g., OSE-230/ABBV-230) [112] that promote inflammatory resolution, highlight promising directions for translational research. However, several key questions remain unresolved: which receptor subtypes mediate beneficial versus deleterious effects, how proteolytic processing alters receptor bias, and under which temporal or tissue conditions therapeutic intervention would be both safe and effective.

Future research should integrate structural pharmacology, spatial transcriptomics, multi-omics profiling, and disease-stage-specific modeling to better define actionable therapeutic windows for chemerin modulation. Furthermore, longitudinal clinical cohorts, organoid-based disease models, and interventional studies are required to establish causal relationships, validate therapeutic efficacy, and translate preclinical discoveries into clinical applications.

8. Limitations

This review is limited by the heterogeneity of existing studies, including variations in patient populations, disease models, detection methods, and reporting of chemerin isoforms. The inclusion of both experimental and clinical data introduces interpretative complexity, as many studies lack standardized outcome measures. Furthermore, due to the narrative nature of this review, quantitative synthesis and meta-analytic validation were not feasible. Finally, publication bias and the predominance of small, single-center studies may have influenced the overall interpretation of chemerin’s role in gastrointestinal diseases.

9. Conclusions

Chemerin has emerged as a pivotal link between metabolism, inflammation, and gastrointestinal pathology. Evidence across studies indicates that altered chemerin signaling contributes to mucosal immune imbalance, fibrosis, and tumor progression within the gastrointestinal tract. However, its dual and context-dependent underscore the complexity of its biological actions. A deeper understanding of receptor-specific mechanisms, isoform diversity, and metabolic confounders such as obesity is essential to clarify chemerin’s precise role in gastrointestinal disease. Ultimately, advancing standardized methodologies, integrative multi-omics analyses, and translational research into receptor-selective agonists or antagonists will be critical to unlock chemerin’s diagnostic and therapeutic potential.

Author Contributions

E.D. and E.P. contributed equally to this work, designing and coordinating the study, performing the literature review, analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. I.C., M.M., I.S., D.R., V.M., T.N., L.S., E.C.L., S.V., S.S., K.C., H.P. and A.H. assisted in the study design, data analysis, and manuscript writing. I.C., L.S., N.I., N.U. and S.H. aided in data collection, interpretation, and manuscript preparation. D.P., M.N. and M.J. provided critical revisions and intellectual contributions to the manuscript. M.N. and M.J. offered expert guidance and critical revisions. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| AGS | Human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line |

| ALT | Alanine aminotransferase |

| AP | Alkaline phosphatase |

| AST | Aspartate aminotransferase |

| AUC | Area under the curve |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| CA19-9 | Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 |

| CCRL2 | C-C chemokine receptor-like 2 |

| CD | Crohn’s disease |

| CEA | Carcinoembryonic antigen |

| CLIF-SOFA | Chronic Liver Failure–Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| CMKLR1 | Chemokine-like receptor 1 (ChemR23) |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| CXCL1/2 | C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 1/2 |

| DAA | Direct-acting antivirals |

| DSS | Dextran sodium sulfate |

| EBV | Epstein–Barr virus |

| EGR1 | Early growth response 1 |

| EMT | Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| EPIC | European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition |

| ERCP | Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography |

| ERK | Extracellular signal–regulated kinase |

| ERK1/2 | Extracellular signal–regulated kinases 1 and 2 |

| FAP | Fibroblast activation protein |

| FIZZ1 | Found in inflammatory zone 1 (Resistin-like molecule alpha, RELMα) |

| FOS | FBJ murine osteosarcoma viral oncogene homolog (c-Fos) |

| GM-CSF | Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor |

| GPR1 | G protein–coupled receptor 1 |

| HBV | Hepatitis B virus |

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HLAP | Hyperlipidemia-induced acute pancreatitis |

| HR | Hazard ratio |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IBS | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL-10 | Interleukin-10 |

| IL-17 | Interleukin-17 |

| IL-4 | Interleukin-4 |

| IL-6 | Interleukin-6 |

| INR | International normalized ratio |

| KATO III | Human gastric cancer cell line KATO III |

| LC3 | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 |

| LC3-II | Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3-II |

| LPO | Lactoperoxidase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MAFLD | Metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease |

| MAP | Mean arterial pressure |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| MAPKs | Mitogen-activated protein kinases |

| MASLD | Metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease |

| MDSC | Myeloid-derived suppressor cell |

| MELD | Model for End-Stage Liver Disease |

| MKN28 | Human gastric cancer cell line MKN28 |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MUC2 | Mucin 2 |

| NAFLD | Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease |

| NASH | Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis |

| NF-κB | Nuclear factor kappa B |

| OR | Odds ratio |

| p38 | p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| PCT | Procalcitonin |

| PD-L1 | Programmed death-ligand 1 |

| PEP | Post-ERCP pancreatitis |

| PI3K | Phosphoinositide 3-kinase |

| PKC | Protein kinase C |

| PKM2 | Pyruvate kinase M2 |

| PTEN | Phosphatase and tensin homolog |

| RARRES2 | Retinoic acid receptor responder 2 (chemerin) |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic |

| ROCK | Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase |

| RhoA | Ras homolog family member A |

| SMMC7721 | Human hepatoma cell line SMMC-7721 |

| SPP1 | Secreted phosphoprotein 1 (osteopontin) |

| SRF | Serum response factor |

| STAT6 | Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 |

| TFF3 | Trefoil factor 3 |

| TIG2 | Tazarotene-induced gene 2 (chemerin) |

| TIMP | Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNBS | 2,4,6-Trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid |

| TRX1 | Thioredoxin 1 |

| UC | Ulcerative colitis |

| VAT | Visceral adipose tissue |

| VCL | Vinculin |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

| Ym1 | Chitinase-like protein 3 (Ym1/CHI3L3) |

| hsCRP | High-sensitivity C-reactive protein |

References

- Kirichenko, T.V.; Markina, Y.V.; Bogatyreva, A.I.; Tolstik, T.V.; Varaeva, Y.R.; Starodubova, A.V. The Role of Adipokines in Inflammatory Mechanisms of Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 14982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Leung, L.L.; Morser, J. Chemerin Forms: Their Generation and Activity. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wang, B. Chemerin in inflammatory diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta 2021, 517, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, G.; An, Q.; Xu, X.; Jin, Z.; Ding, J.; Hu, Y.; Du, Q.; Xu, J.; Xie, R. The role of Chemerin in human diseases. Cytokine 2023, 162, 156089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macvanin, M.T.; Rizzo, M.; Radovanovic, J.; Sonmez, A.; Paneni, F.; Isenovic, E.R. Role of Chemerin in Cardiovascular Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeck, O.; Buechler, C. Chemerin Signaling in Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.L.; Yang, Z.; Yang, S.S. Roles of Adipokines in Digestive Diseases: Markers of Inflammation, Metabolic Alteration and Disease Progression. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.; Xiang, Q.; Long, M.; Liao, J.; Wang, F.; Li, X. Chemerin as a biomarker of inflammatory bowel diseases: A meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechler, C. Chemerin in liver diseases. Endocrinol. Metab. Syndr. 2014, 3, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, W.J.; Zabel, B.A.; Pachynski, R.K. Mechanisms and Functions of Chemerin in Cancer: Potential Roles in Therapeutic Intervention. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 2772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, A.J.; Davenport, A.P. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology CIII: Chemerin Receptors CMKLR1 (Chemerin1) and GPR1 (Chemerin2) Nomenclature, Pharmacology, and Function. Pharmacol. Rev. 2018, 70, 174–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacenik, D.; Fichna, J. Chemerin in Immune Response and Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. Clin. Chim. Acta Int. J. Clin. Chem. 2020, 504, 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, G.; Liao, Q.; Lyu, W.; Liu, A.; Zhu, L.; Du, Y.; Ye, R.D. Cryo-EM structure of the human chemerin receptor 1-Gi protein complex bound to the C-terminal nonapeptide of chemerin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2214324120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buechler, C.; Feder, S.; Haberl, E.M.; Aslanidis, C. Chemerin Isoforms and Activity in Obesity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kennedy, A.J.; Yang, P.; Read, C.; Kuc, R.E.; Yang, L.; Taylor, E.J.A.; Taylor, C.W.; Maguire, J.J.; Davenport, A.P. Chemerin Elicits Potent Constrictor Actions via Chemokine-Like Receptor 1 (CMKLR1), Not G-Protein-Coupled Receptor 1 (GPR1), in Human and Rat Vasculature. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2016, 5, e004421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cash, J.L.; Bass, M.D.; Campbell, J.; Barnes, M.; Kubes, P.; Martin, P. Resolution Mediator Chemerin15 Reprograms the Wound Microenvironment to Promote Repair and Reduce Scarring. Curr. Biol. CB 2014, 24, 1406–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Huang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, P.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, T.; Zabel, B.A.; Zhang, J.V. Chemerin-Derived Peptide C-20 Suppressed Gonadal Steroidogenesis. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2014, 71, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Friebus-Kardash, J.; Schulz, P.; Reinicke, S.; Karthaus, C.; Schefer, Q.; Bandholtz, S.; Grötzinger, C. A Chemerin Peptide Analog Stimulates Tumor Growth in Two Xenograft Mouse Models of Human Colorectal Carcinoma. Cancers 2021, 14, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, T.F.; Czerniak, A.S.; Weiß, T.; Zellmann, T.; Zielke, L.; Els-Heindl, S.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G. Cyclic Derivatives of the Chemerin C-Terminus as Metabolically Stable Agonists at the Chemokine-like Receptor 1 for Cancer Treatment. Cancers 2021, 13, 3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfer, G.; Wu, Q.F. Chemerin: A multifaceted adipokine involved in metabolic disorders. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 238, R79–R94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylonakis, A.; Frountzas, M.; Lidoriki, I.; Kozadinos, A.; Kalfoutzou, A.; Karanikki, E.; Tsikrikou, I.; Kyriakidou, M.; Theodorou, D.; Toutouzas, K.G.; et al. The Role of Chemerin in Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer. Metabolites 2024, 14, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Yang, Y.; Huang, C.; Ge, L.; Xue, L.; Xiao, Z.; Xiao, T.; Zhao, H.; Ren, P.; Zhang, J.V. Chemerin: A Functional Adipokine in Reproductive Health and Diseases. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Ye, R.D. Structural basis for full-length chemerin recognition and signaling through chemerin receptor 1. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goralski, K.B.; McCarthy, T.C.; Hanniman, E.A.; Zabel, B.A.; Butcher, E.C.; Parlee, S.D.; Muruganandan, S.; Sinal, C.J. Chemerin, a Novel Adipokine That Regulates Adipogenesis and Adipocyte Metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282, 28175–28188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parolini, S.; Santoro, A.; Marcenaro, E.; Luini, W.; Massardi, L.; Facchetti, F.; Communi, D.; Parmentier, M.; Majorana, A.; Sironi, M.; et al. The Role of Chemerin in the Colocalization of NK and Dendritic Cell Subsets into Inflamed Tissues. Blood 2007, 109, 3625–3632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Henau, O.; Degroot, G.N.; Imbault, V.; Robert, V.; De Poorter, C.; Mcheik, S.; Galés, C.; Parmentier, M.; Springael, J.Y. Signaling Properties of Chemerin Receptors CMKLR1, GPR1 and CCRL. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0164179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Dhaou, C.; Del Prete, A.; Sozzani, S.; Parmentier, M. CCRL2 Modulates Physiological and Pathological Angiogenesis During Retinal Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 808455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degroot, G.N.; Lepage, V.; Parmentier, M.; Springael, J.Y. The Atypical Chemerin Receptor GPR1 Displays Different Modes of Interaction with-Arrestins in Humans and Mice with Important Consequences on Subcellular Localization and Trafficking. Cells 2022, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochal, M.; Mosińska, P.; Fichna, J. Diagnostic value of chemerin in lower gastrointestinal diseases-a review. Peptides 2018, 108, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somja, J.; Demoulin, S.; Roncarati, P.; Herfs, M.; Bletard, N.; Delvenne, P.; Hubert, P. Dendritic cells in Barrett′s esophagus carcinogenesis: An inadequate microenvironment for antitumor immunity? Am. J. Pathol. 2013, 182, 2168–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.D.; Holmberg, C.; Kandola, S.; Steele, I.; Hegyi, P.; Tiszlavicz, L.; Jenkins, R.; Beynon, R.J.; Peeney, D.; Giger, O.T.; et al. Increased expression of chemerin in squamous esophageal cancer myofibroblasts and role in recruitment of mesenchymal stromal cells. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e104877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.D.; Holmberg, C.; Balabanova, S.; Borysova, L.; Burdyga, T.; Beynon, R.; Dockray, G.J.; Varro, A. Mesenchymal Stem Cells Exhibit Regulated Exocytosis in Response to Chemerin and IGF. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0141331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, J.D.; Kandola, S.; Tiszlavicz, L.; Reisz, Z.; Dockray, G.J.; Varro, A. The role of chemerin and ChemR23 in stimulating the invasion of squamous oesophageal cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 114, 1152–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Yan, C.; Xu, B.; Hu, R.; Ma, M.; Wei, H.; Meng, Y. A comparative study on the efficacy of fast-track surgery in the treatment of esophageal cancer patients combined with metabolic syndrome. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 4812–4816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, R.; Nakayama, I.; Markar, S.R.; Shitara, K.; van Laarhoven, H.W.M.; Janjigian, Y.Y.; Smyth, E.C. Gastric cancer. Lancet 2025, 405, 2087–2102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, W.K.; Liu, X.; To, K.F.; Chen, G.G.; Yu, J.; Ng, E.K. Increased serum chemerin level promotes cellular invasiveness in gastric cancer: A clinical and experimental study. Peptides 2014, 51, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jin, H.C.; Zhu, A.K.; Ying, R.C.; Wei, W.; Zhang, F.J. Prognostic significance of plasma chemerin levels in patients with gastric cancer. Peptides 2014, 61, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rourke, J.L.; Dranse, H.J.; Sinal, C.J. CMKLR1 and GPR1 mediate chemerin signaling through the RhoA/ROCK pathway. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2015, 417, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, J.D.; Aolymat, I.; Tiszlavicz, L.; Reisz, Z.; Garalla, H.M.; Beynon, R.; Simpson, D.; Dockray, G.J.; Varro, A. Chemerin acts via CMKLR1 and GPR1 to stimulate migration and invasion of gastric cancer cells: Putative role of decreased TIMP-1 and TIMP-2. Oncotarget 2019, 10, 98–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabassum, M. The Role of Chemerin in Helicobacter pylori–Induced Gastric Pathogenesis. Master’s Thesis, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, M.; Okimura, Y.; Iguchi, G.; Nishizawa, H.; Yamamoto, M.; Suda, K.; Kitazawa, R.; Fujimoto, W.; Takahashi, K.; Zolotaryov, F.N.; et al. Chemerin regulates β-cell function in mice. Sci. Rep. 2011, 1, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koksal, A.R.; Boga, S.; Alkim, H.; Sen, I.; Neijmann, S.T.; Alkim, C. Chemerin: A new biomarker to predict postendoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 714–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Wei, N.; Zheng, Z.; Liang, H. Relationship between apoA-I, chemerin, Procalcitonin and severity of hyperlipidaemia-induced acute pancreatitis. JPMA. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2022, 72, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaworek, J.; Szklarczyk, J.; Kot, M.; Góralska, M.; Jaworek, A.; Bonior, J.; Leja-Szpak, A.; Nawrot-Porąbka, K.; Link-Lenczowski, P.; Ceranowicz, P.; et al. Chemerin alleviates acute pancreatitis in the rat thorough modulation of NF-κB signal. Pancreatology 2019, 19, 401–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adrych, K.; Stojek, M.; Smoczynski, M.; Sledzinski, T.; Sylwia, S.W.; Swierczynski, J. Increased serum chemerin concentration in patients with chronic pancreatitis. Dig. Liver Dis. Off. J. Ital. Soc. Gastroenterol. Ital. Assoc. Study Liver 2012, 44, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiczmer, P.; Szydło, B.; Seńkowska, A.P.; Jopek, J.; Wiewióra, M.; Piecuch, J.; Ostrowska, Z.; Świętochowska, E. Serum omentin-1 and chemerin concentrations in pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis. Folia Med. Cracov. 2018, 58, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Lu, G.; Ke, L.; Tong, Z.; Kasimu, M.; Hu, D.; Xu, Q.; Li, W. Regulatory effect of chemerin and therapeutic efficacy of chemerin-9 in pancreatogenic diabetes mellitus. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 21, 981–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffranchi, M.; Schioppa, T.; Sozio, F.; Piserà, A.; Tiberio, L.; Salvi, V.; Bosisio, D.; Musso, T.; Sozzani, S.; Del Prete, A. Chemerin in immunity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2025, 117, qiae181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, R.; Eichelberger, L.; Feder, S.; Haberl, E.M.; Rein-Fischboeck, L.; McMullen, N.; Sinal, C.J.; Bruckmann, A.; Weiss, T.S.; Beck, M.; et al. Hepatocyte expressed chemerin-156 does not protect from experimental non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2022, 477, 2059–2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindraj, R.; Renuka, P.; Vinodhini, V.M.; Meenakshi Sundari, S.N. Circulating Chemerin Levels in Obese and Non-obese Individuals and Its Association With Obesity in Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Cureus 2024, 16, e68105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinella, M.E.; Sookoian, S. From NAFLD to MASLD: Updated naming and diagnosis criteria for fatty liver disease. J. Lipid Res. 2024, 65, 100485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautbauer, S.; Wanninger, J.; Eisinger, K.; Hader, Y.; Beck, M.; Kopp, A.; Schmid, A.; Weiss, T.S.; Dorn, C.; Buechler, C. Chemerin is highly expressed in hepatocytes and is induced in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis liver. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2013, 95, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, R.; Feder, S.; Haberl, E.M.; Rein-Fischboeck, L.; Weiss, T.S.; Spirk, M.; Bruckmann, A.; McMullen, N.; Sinal, C.J.; Buechler, C. Chemerin Overexpression in the Liver Protects against Inflammation in Experimental Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Dou, Z.; Li, N.; Suo, Y.; Ma, Y.; Sun, M.; Tian, Z.; Xu, L. Chemerin/CMKLR1 ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by promoting autophagy and alleviating oxidative stress through the JAK2-STAT3 pathway. Peptides 2021, 135, 170422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Lu, F.; Wu, L.; He, B.; Chen, Z.; Yan, M. Berberine attenuates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by regulating chemerin/CMKLR1 signalling pathway and Treg/Th17 ratio. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg′s Arch. Pharmacol. 2021, 394, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukla, M.; Zwirska-Korczala, K.; Hartleb, M.; Waluga, M.; Chwist, A.; Kajor, M.; Ciupinska-Kajor, M.; Berdowska, A.; Wozniak-Grygiel, E.; Buldak, R. Serum chemerin and vaspin in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 45, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, Y.; Yonal, O.; Kurt, R.; Alahdab, Y.O.; Eren, F.; Ozdogan, O.; Celikel, C.A.; Imeryuz, N.; Kalayci, C.; Avsar, E. Serum levels of omentin, chemerin and adipsin in patients with biopsy-proven nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2011, 46, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamza, R.T.; Elkabbany, Z.A.; Shedid, A.M.; Hamed, A.I.; Ebrahim, A.O. Serum Chemerin in Obese Children and Adolescents Before and After L-Carnitine Therapy: Relation to Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Other Features of Metabolic Syndrome. Arch. Med. Res. 2016, 47, 541–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Sun, F.; Li, L.; Jiang, D.; Li, X.; Sun, A.; Pan, Z.; Lou, N.; Zhang, L.; Lou, F. Therapeutic Effect of Metformin on Chemerin in Non-Obese Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD). Clin. Lab. 2015, 61, 1409–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, H. Correlation of blood glucose, serum chemerin and insulin resistance with NAFLD in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 15, 2936–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, L.M.; Völzke, H.; Lerch, M.M.; Kühn, J.P.; Nauck, M.; Friedrich, N.; Zylla, S. Associations of circulating chemerin and adiponectin concentrations with hepatic steatosis. Endocr. Connect. 2019, 8, 1097–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohl, R.; Haberl, E.M.; Rein-Fischboeck, L.; Zimny, S.; Neumann, M.; Aslanidis, C.; Schacherer, D.; Krautbauer, S.; Eisinger, K.; Weiss, T.S.; et al. Hepatic chemerin mRNA expression is reduced in human nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 47, 7–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kajor, M.; Kukla, M.; Waluga, M.; Liszka, Ł.; Dyaczyński, M.; Kowalski, G.; Żądło, D.; Berdowska, A.; Chapuła, M.; Kostrząb-Zdebel, A.; et al. Hepatic chemerin mRNA in morbidly obese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pol. J. Pathol. 2017, 68, 117–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaert, M.; Ouwens, D.M.; Hörbelt, T.; Van de Velde, F.; Fahlbusch, P.; Herzfeld de Wiza, D.; Van Nieuwenhove, Y.; Calders, P.; Praet, M.; Hoorens, A.; et al. Reduced expression of chemerin in visceral adipose tissue associates with hepatic steatosis in patients with obesity. Obesity 2016, 24, 2544–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Y.; Fang, X.; Wang, M.; Li, D.; Huang, W.; Xu, Y. Circulating chemerin levels in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis. 2022, 21, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisinger, K.; Krautbauer, S.; Wiest, R.; Weiss, T.S.; Buechler, C. Reduced serum chemerin in patients with more severe liver cirrhosis. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2015, 98, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horn, P.; von Loeffelholz, C.; Forkert, F.; Stengel, S.; Reuken, P.; Aschenbach, R.; Stallmach, A.; Bruns, T. Low circulating chemerin levels correlate with hepatic dysfunction and increased mortality in decompensated liver cirrhosis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peschel, G.; Grimm, J.; Gülow, K.; Müller, M.; Buechler, C.; Weigand, K. Chemerin Is a Valuable Biomarker in Patients with HCV Infection and Correlates with Liver Injury. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prystupa, A.; Kiciński, P.; Luchowska-Kocot, D.; Sak, J.; Prystupa, T.K.; Tan, Y.H.; Panasiuk, L.; Załuska, W. Factors influencing serum chemerin and kallistatin concentrations in patients with alcohol-induced liver cirrhosis. Ann. Agric. Environ. Med. 2019, 26, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazgan-Simon, M.; Szymanek-Pasternal, A.; Górka-Dynysiewicz, J.; Nowicka, A.; Simon, K.; Grzebyk, E.; Kukla, M. Serum chemerin level in patients with liver cirrhosis and primary and multifocal hepatocellular carcinoma with consideration of insulin level. Arch. Med. Sci. 2024, 20, 1504–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francisco, V.; Sanz, M.J.; Real, J.T.; Marques, P.; Capuozzo, M.; Ait Eldjoudi, D.; Gualillo, O. Adipokines in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Are we on the road toward new biomarkers and therapeutic targets? Biology 2022, 11, 1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabia, B.; Andrade, S.; Carreira, M.C.; Casanueva, F.F.; Crujeiras, A.B. A role for novel adipose tissue-secreted factors in obesity-related carcinogenesis. Obes. Rev. Off. J. Int. Assoc. Study Obes. 2016, 17, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, E.M.; Pohl, R.; Rein-Fischboeck, L.; Feder, S.; Sinal, C.J.; Buechler, C. Chemerin in a mouse model of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and hepatocarcinogenesis. Anticancer. Res. 2018, 38, 2649–2657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, J.; Huang, C.; Wang, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, X.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Nuclear translocation of metabolic enzyme PKM2 participates in high glucose-promoted HCC metastasis by strengthening immunosuppressive environment. Redox Biol. 2024, 71, 103103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, S.; Bruckmann, A.; McMullen, N.; Sinal, C.J.; Buechler, C. Chemerin isoform-specific effects on hepatocyte migration and immune cell inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, W.; Li, B.; Yin, W.; Shi, Y.; He, R. Chemerin has a protective role in hepatocellular carcinoma by inhibiting the expression of IL-6 and GM-CSF and MDSC accumulation. Oncogene 2017, 36, 3599–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.J.; Yin, H.K.; Guan, D.X.; Zhao, J.S.; Feng, Y.X.; Deng, Y.Z.; Wang, X.; Li, N.; Wang, X.F.; Cheng, S.Q.; et al. Chemerin suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis through CMKLR1-PTEN-Akt axis. Br. J. Cancer 2018, 118, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, P.; Dong, K.; Xin, Y.; Tailulu, A.; Li, Q.; Sun, J.; Peng, M.; Shi, P. Chemerin reverses the malignant phenotype and induces differentiation of human hepatoma SMMC7721 cells. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2021, 44, 194–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, J.; Peng, M.; Shi, P. The involvement of iron in chemerin-induced cell cycle arrest in human hepatic carcinoma SMMC7721 cells. Met: Integr. Biometal Sci. 2018, 10, 838–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, E.M.; Feder, S.; Pohl, R.; Rein-Fischboeck, L.; Dürholz, K.; Eichelberger, L.; Wanninger, J.; Weiss, T.S.; Buechler, C. Chemerin is induced in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers 2020, 12, 2967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Y.; Bu, Z.; Qin, Y.; Qian, S.; Qin, L.; Zhou, S.; Wang, Q.; Xian, L.; Hu, L.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Exploring the role of adipokines in exercise-induced inhibition of tumor growth. Sports Med. Health Sci. 2024, 7, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feder, S.; Kandulski, A.; Schacherer, D.; Weiss, T.S.; Buechler, C. Serum adiponectin levels do not distinguish primary from metastatic liver tumors. Anticancer. Res. 2020, 40, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q. A Comprehensive Review and Update on the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2019, 7247238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowan, C.R.; McManus, J.; Boland, K.; O′Toole, A. Visceral adiposity and inflammatory bowel disease. Int. J. Color. Dis. 2021, 36, 2305–2319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buechler, C. Chemerin, a novel player in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 11, 315–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, X.; Yue, W.; Xu, X.; Li, B.; Zou, L.; He, R. Chemerin aggravates DSS-induced colitis by suppressing M2 macrophage polarization. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2014, 11, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranse, H.J.; Rourke, J.L.; Stadnyk, A.W.; Sinal, C.J. Local chemerin levels are positively associated with DSS-induced colitis but constitutive loss of CMKLR1 does not protect against development of colitis. Physiol. Rep. 2015, 3, e12497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szandruk-Bender, M.; Rutkowska, M.; Merwid-Ląd, A.; Wiatrak, B.; Szeląg, A.; Dzimira, S.; Sobieszczańska, B.; Krzystek-Korpacka, M.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Matuszewska, A.; et al. Cornelian Cherry Iridoid-Polyphenolic Extract Improves Mucosal Epithelial Barrier Integrity in Rat Experimental Colitis and Exerts Antimicrobial and Antiadhesive Activities In Vitro. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 7697851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Cai, Q.; Luo, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Xuan, Y.; Yang, H.; He, R. Epithelial chemerin-CMKLR1 signaling restricts microbiota-driven colonic neutrophilia and tumorigenesis by up-regulating lactoperoxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2205574119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, J.; Obermeier, F.; Neumeier, M.; Wanninger, J.; Filarsky, M.; Bauer, S.; Aslanidis, C.; Rogler, G.; Ott, C.; Schäffler, A.; et al. Circulating levels of chemerin and adiponectin are higher in ulcerative colitis and chemerin is elevated in Crohn′s disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2010, 16, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waluga, M.; Hartleb, M.; Boryczka, G.; Kukla, M.; Zwirska-Korczala, K. Serum adipokines in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014, 20, 6912–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzoudis, S.; Malliaraki, N.; Damilakis, J.; Dimitriadou, D.A.; Zavos, C.; Koutroubakis, I.E. Chemerin, visfatin, and vaspin serum levels in relation to bone mineral density in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 28, 814–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sochal, M.; Fichna, J.; Gabryelska, A.; Talar-Wojnarowska, R.; Białasiewicz, P.; Małecka-Wojciesko, E. Serum Levels of Chemerin in Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease as an Indicator of Anti-TNF Treatment Efficacy. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 4615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawan, S.; Elger, T.; Loibl, J.; Fererberger, T.; Sommersberger, S.; Kandulski, A.; Müller, M.; Tews, H.C.; Buechler, C. Urinary chemerin as a potential biomarker for inflammatory bowel disease. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1058108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, A.C.; Sperber, A.D.; Corsetti, M.; Camilleri, M. Irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet 2020, 396, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nozu, T.; Okumura, T. Pathophysiological Commonality Between Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Metabolic Syndrome: Role of Corticotropin-releasing Factor-Toll-like Receptor 4-Proinflammatory Cytokine Signaling. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2022, 28, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baram, M.A.; Abbasnezhad, A.; Ghanadi, K.; Anbari, K.; Choghakhori, R.; Ahmadvand, H. Serum Levels of Chemerin, Apelin, and Adiponectin in Relation to Clinical Symptoms, Quality of Life, and Psychological Factors in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2020, 54, e40–e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roczniak, W.; Szymlak, A.; Mazur, B.; Chobot, A.; Stojewska, M.; Oświęcimska, J. Nutritional Status and Selected Adipokines in Children with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nutrients 2020, 14, 5282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roshandel, G.; Ghasemi-Kebria, F.; Malekzadeh, R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers 2024, 16, 1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yagi, M.; Sasaki, Y.; Abe, Y.; Yaoita, T.; Sakuta, K.; Mizumoto, N.; Shoji, M.; Onozato, Y.; Kon, T.; Nishise, S.; et al. Association between High Levels of Circulating Chemerin and Colorectal Adenoma in Men. Digestion 2020, 101, 571–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eichelmann, F.; Schulze, M.B.; Wittenbecher, C.; Menzel, J.; Weikert, C.; di Giuseppe, R.; Biemann, R.; Isermann, B.; Fritsche, A.; Boeing, H.; et al. Association of Chemerin Plasma Concentration With Risk of Colorectal Cancer. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e190896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkady, M.M.; Abdel-Messeih, P.L.; Nosseir, N.M. Assessment of Serum Levels of the Adipocytokine Chemerin in Colorectal Cancer Patients. J. Med. Biochem. 2018, 37, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, S.; Yilmaz, F.M.; Yazici, O.; Yozgat, A.; Sezer, S.; Ozdemir, N.; Uysal, S.; Purnak, T.; Sendur, M.A.; Ozaslan, E. Inflammation and chemerin in colorectal cancer. Tumour Biol. J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelopmental Biol. Med. 2016, 37, 6337–6342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, M.K.; Kim, N.K.; Chu, S.H.; Lee, D.C.; Lee, H.S.; Lee, J.W.; Jeon, J.Y. Serum chemerin levels are independently associated with quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors: A pilot study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0176929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waniczek, D.; Świętochowska, E.; Śnietura, M.; Kiczmer, P.; Lorenc, Z.; Muc-Wierzgoń, M. Salivary Concentrations of Chemerin, α-Defensin 1, and TNF-α as Potential Biomarkers in the Early Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer. Metabolites 2022, 12, 704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiczmer, P.; Seńkowska, A.P.; Kula, A.; Dawidowicz, M.; Strzelczyk, J.K.; Zajdel, E.N.; Walkiewicz, K.; Waniczek, D.; Ostrowska, Z.; Świętochowska, E. Assessment of CMKLR1 level in colorectal cancer and its correlation with angiogenic markers. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 2020, 113, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiczmer, P.; Mielcarska, S.; Chrabańska, M.; Dawidowicz, M.; Kula, A.; Rynkiewicz, M.; Seńkowska, A.P.; Waniczek, D.; Piecuch, J.; Jopek, J.; et al. The Concentration of CMKLR1 Expression on Clinicopathological Parameters of Colorectal Cancer: A Preliminary Study. Medicina 2021, 57, 1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Villanueva, A.; Jordà, M.; Carreras-Torres, R.; Alonso, H.; Cordero, D.; Guinó, E.; Sanjuan, X.; Santos, C.; Salazar, R.; Sanz-Pamplona, R.; et al. Identifying causal models between genetically regulated methylation patterns and gene expression in healthy colon tissue. Clin. Epigenetics 2021, 13, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Sun, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Xun, Z.; Li, Z.; Ding, X.; Bao, R.; Hong, L.; Jia, W.; et al. Single-cell and spatial analysis reveal interaction of FAP+ fibroblasts and SPP1+ macrophages in colorectal cancer. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suriano, F.; Van Hul, M.; Cani, P.D. Gut microbiota and regulation of myokine-adipokine function. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 52, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Weiß, T.; Cheng, M.H.; Chen, S.; Ambrosius, C.K.; Czerniak, A.S.; Li, K.; Feng, M.; Bahar, I.; Beck-Sickinger, A.G.; et al. Structural basis of G protein-Coupled receptor CMKLR1 activation and signaling induced by a chemerin-derived agonist. PLoS Biol. 2023, 21, e3002188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OSE Immunotherapeutics. OSE Immunotherapeutics’ Global License to Develop a Novel Monoclonal Antibody for the Treatment of Chronic Inflammation Becomes Effective. 2024. Available online: https://www.ose-immuno.com/ (accessed on 17 October 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).