Abstract

Fibromyalgia is a common disease syndrome characterized by chronic pain and fatigue in conjunction with cognitive dysfunction such as memory difficulties. Patients currently face a difficult prognosis with limited treatment options and a diminished quality of life. Given its widespread use and potential efficacy in treating other types of pain, cannabis may prove to be an effective treatment for fibromyalgia. This review aims to examine and discuss current clinical evidence regarding the use of cannabis for the treatment of fibromyalgia. An electronic search was conducted on MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus using Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms on all literature published up to October 2022. A follow-up manual search included a complete verification of relevant studies. The results of four randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and five observational studies (a total of 564 patients) that investigated the effects of cannabis on fibromyalgia symptoms were included in this review. Of the RCTs, only one demonstrated that cannabinoids did not have a different effect than placebo on pain responses. Overall, this analysis shows low-quality evidence supporting short-term pain reduction in people with fibromyalgia treated with cannabinoid therapeutics. Although current evidence is limited, medical cannabis appears to be a safe alternative for treating fibromyalgia.

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia is a common and often debilitating disease syndrome characterized by chronic pain in conjunction with cognitive symptoms including fatigue, impaired sleep, and psychiatric comorbidities [1]. It is estimated to affect 2–8% of the population, with women more commonly affected than men [1]. Fibromyalgia is a clinical diagnosis based on defined criteria including widespread pain, chronicity of symptoms, and lack of an alternative explanation for symptoms [2]. While the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia remains unclear, the pain is thought to be due to derangements in central-nervous-system-mediated pain processing [3]. This disease adversely affects patients’ quality of life and can carry a significant monetary burden [4]. Current standard treatments include cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), antidepressant and neuropathic medications, and exercise therapy. However, the efficacy of these treatments is limited [5]. Patients currently face a difficult prognosis with limited treatment options and often diminished quality of life.

Cannabis has been proposed as an alternative therapy for the treatment of fibromyalgia. While the cannabis plant has a complex chemical makeup, the two components most commonly isolated for therapeutic effects are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) [6]. Their effects are mediated through the type 1 cannabinoid receptor (CB1), which is expressed in the central nervous system, and the type 2 cannabinoid receptor (CB2), which is expressed in peripheral inflammatory cells [7].

The use of medical cannabis has been explored in a wide variety of diseases. Currently, THC has the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)’s approval for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, and for appetite stimulation related to cancer, although it is not considered a first-line treatment [8]. It has also been explored in a variety of chronic pain disorders, such as muscle spasticity from multiple sclerosis [9] and neuropathic pain [10]. Given its widespread use and potential efficacy in treating other types of pain, there is speculation that cannabis may prove to be an effective treatment for fibromyalgia. The aim of this review is to examine current clinical evidence regarding the use of cannabis for the treatment of fibromyalgia.

2. Methods

A systematic search was conducted using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines to identify relevant literature. The databases searched were MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Scopus. The review focused on peer-reviewed studies published in the English language from database inception until 25 September 2022. The search utilized the following keywords: (fibromyalgia) OR (central sensitization) OR (chronic pain) AND (medical cannabis) OR (cannabis) OR (cannabinoids) AND (randomized controlled trial) OR (controlled clinical trial) OR (randomized) OR (placebo) OR (randomly) OR (trial). Two reviewers independently extracted the data, and any discrepancies were resolved by a third review author. The authors conducted the latest database search on 23 October 2022, before submission, and the details of the search strategy are presented in Table S1.

Original articles were included if they met the following criteria: (1) observational, retrospective, or prospective human study design; (2) published in the English language; (3) the target population comprised patients diagnosed with fibromyalgia; and (4) the study assessed the effects of cannabinoid products on fibromyalgia pain. The primary outcomes of interest included widespread pain index (WPI), symptom severity scale (SS), Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) score, and visual analog scale (VAS) pain. Exclusion criteria included duplicated studies, narrative reviews, integrative reviews, letters, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, as well as animal and cell studies.

Two authors (D.A.G. and V.T.F.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all identified studies for eligibility and, subsequently, assessed each study to determine whether it met the inclusion criteria. The following information was extracted for each study: (1) author, year of publication; (2) sample size, number of patients in FM and control groups, gender, age; (3) diagnostic criteria used to diagnose FM; and (4) data regarding outcomes of interest in both groups.

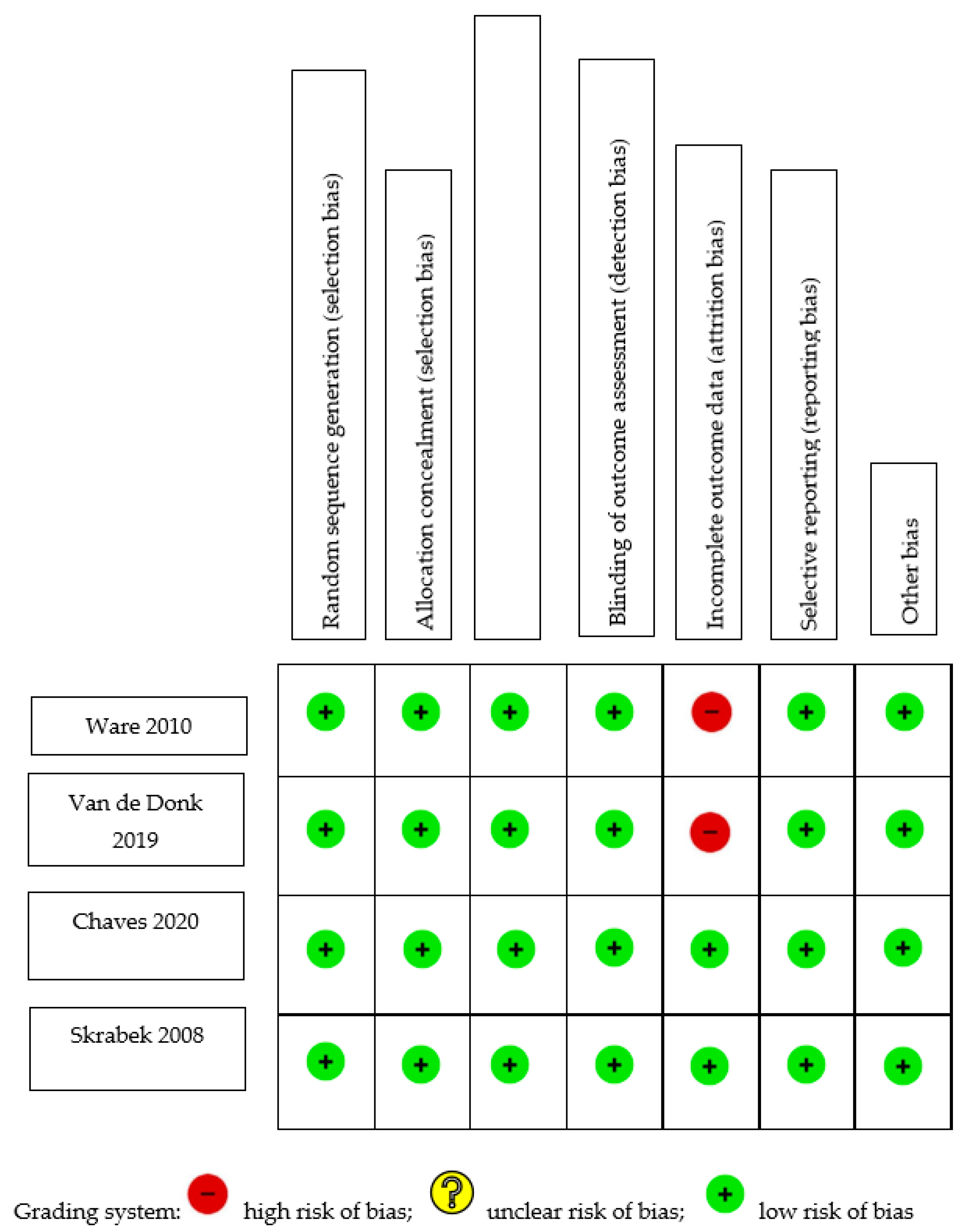

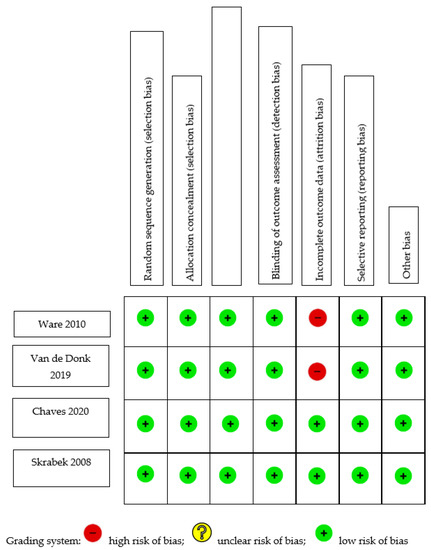

The risk of bias for this study was evaluated using either the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) or the Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Tool (C-ROB). The NOS was used to assess observational studies, while the C-ROB was used to evaluate randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The NOS evaluation focused on three domains: selection, comparability, and exposure/outcome. The maximum numbers of stars awarded for each domain were four, two, and three, respectively. A higher number of stars indicated a lower risk of bias. The C-ROB evaluated six domains: selection, performance, detection, attrition, reporting, and other biases, each of which could receive a score of high, low, or unclear risk. Two authors completed the assessments independently, with a third author resolving any discrepancies.

To assess the overall quality of evidence for cannabinoids in treating pain in fibromyalgia, the authors employed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach. GRADE evaluates the certainty of evidence using standard criteria and assigns a rating of very low, low, moderate, or high to each outcome.

Table 1 summarizes the risk-of-bias assessment for cohort studies. An adequate follow-up period was defined as at least six months, and a minimum of 95% of participants remaining under observation at the primary endpoint was considered sufficient (i.e., fewer than 5% of patients dropped out). Only one of the five studies [11] included a non-exposed control; thus, its selection of controls and comparability bias were evaluated by the authors. Four of the five studies did not select a control group and, therefore, were not evaluated for selection of controls or comparability. Two of the studies [12,13] began with an analgesic trial phase, after which the patients were initiated on medical cannabis therapy (MCT). The calculations concerning the duration of follow-up and the percentage of participants lost to follow-up were based on the number of patients who entered the MCT phase of the investigation. Out of the five studies analyzed, three exhibited a low risk of selection bias, whereas two [11,13] demonstrated high selection bias. This was attributed to their selection of a non-exposed cohort from a different source, and to their dependence on written self-reports to confirm exposure. All studies demonstrated moderate-to-high risk of bias pertaining to outcomes, owing to a high percentage of patients lost to follow-up [13,14], insufficient follow-up of cohorts [11,15], or inadequate assessment of outcomes [11]. Figure 1 shows the C-ROB assessment of the four included RCTs. All four studies demonstrated a low risk of bias in all domains. However, two studies demonstrated attrition bias due to attrition rates of 18% [16] and 20% [17].

Table 1.

Newcastle–Ottawa risk assessment.

Figure 1.

Cochrane Risk-of-Bias Assessment of randomized trials [16,17,18,19].

The evaluation conducted using GRADE determined that the evidence supporting the reduction in pain in fibromyalgia through the use of cannabinoids was generally of low quality. Although all studies incorporated in the analysis were prospective, only four of them were randomized controlled trials (RCTs), thereby diminishing the quality of evidence for this intervention. Stratifying the GRADE quality assessment by various methods of pain evaluation—such as the visual analog scale (VAS) and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ)—demonstrated low-quality evidence for the efficacy of cannabis treatment in reducing pain. A higher-quality RCT was identified, yielding moderate support for the reduction in lower-back pain following cannabis treatment in fibromyalgia. Another RCT was identified demonstrating high-quality evidence that cannabis did not decrease the number of tender points. A summary table with the GRADE assessment is displayed in Table 2.

Table 2.

GRADE assessment.

3. Results

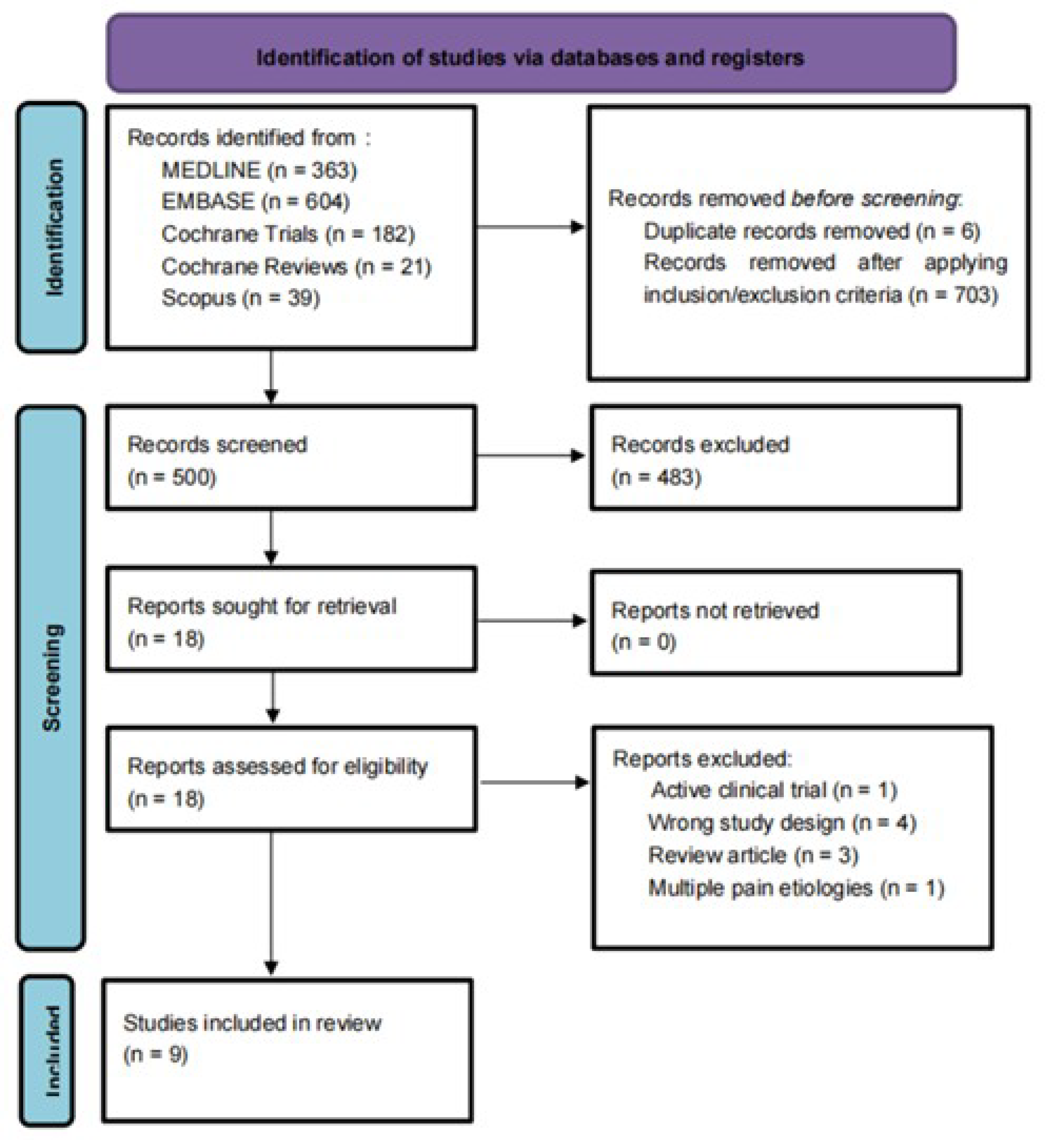

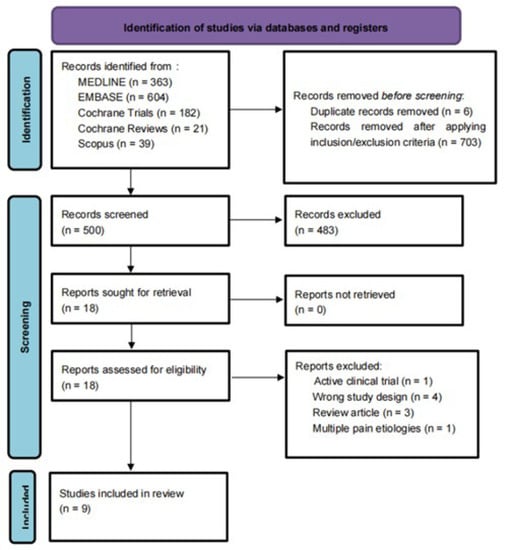

After duplicates were removed, we identified 1203 articles. After screening and assessing for eligibility, nine studies involving 564 participants were included in the systematic review [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. (Figure 2). For a comprehensive list of the excluded articles, see Supplementary Table S2 (Table S2). The exclusion criteria were incomplete clinical trials, duplicated studies, narrative reviews, integrative reviews, letters, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses, as well as animal and cell studies.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flowchart: PRISMA flow diagram for systematic review. Flowchart of the study selection process, inclusion and exclusion of studies, and reasons for exclusion are displayed.

Of the nine included studies, four were randomized controlled trials and five were observational studies. Of the four randomized controlled trials, two studies used a parallel design [18,19] and two used a crossover design [16,17]. Of the five observational studies, one used a crossover design [12], one used a cross-sectional design [11], and three used a prospective or retrospective design [13,14,15]. Of the eight longitudinal studies, five were short-term in duration (4 to 10 weeks), while three were intermediate-term studies (one was 16 weeks, two were 24 weeks). The study sizes ranged between 18 and 367. Table 3 summarizes the study characteristics.

Table 3.

Studies and outcomes.

The mean age of the participants ranged from 33.4 to 52.9 years. Three studies did not report the sex distribution of their participants; of the six that did, the percentage of females ranged from 73% to 100%. It should be noted that race was not reported in any of the studies.

All but one study [12] required that patients were diagnosed with fibromyalgia according to the most recent American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria. One study reported an inclusion criterion requiring a defined pain intensity at baseline (score of 5 or above on a 0–10 scale); this study was also one of only two studies to report a criterion that all patients be female [17]. Six studies required for inclusion that the pain was refractory to previous alternative analgesic therapy, without specifying the type and dosage of said therapies.

All but one study [12] listed exclusion criteria. All eight studies excluded people with major medical and psychiatric diseases. Two studies explicitly excluded people with a sensitivity to cannabinoids [16,18]. One study explicitly excluded people with a history of substance abuse [11].

One study excluded patients with recent cannabis use [17]. One study excluded patients with a history of oral cannabinoids for pain management but did not specify whether other routes of administration or use of cannabinoids for other purposes were allowed [19]. One study permitted patients with recent cannabis use to participate following a 2-week washout period [16].

The treatments used in the studies were oral synthetic THC (nabilone) [19] and cannabis in various forms. Treatments were administered as a pill, oil [16,18], smoke [14], or vapor. The cross-sectional study asked participants to clarify whether they consumed oral or inhaled cannabis but did not further specify the type [11]. Two studies focused on inhaled cannabis, with one using either smoked or vaporized cannabis [12] and the other having participants inhale it through a balloon [17]. One study selected the route of cannabis administration based on patient preferences [15]. Of the four randomized controlled trials, three compared to placebos [17,18,19], while one compared to amitriptyline [16].

Quality Assessment

There was overall low-quality evidence to support reduced pain in fibromyalgia with cannabinoid treatments. While all studies included in this analysis were prospective in nature, only four were RCTs, which reduced the quality of evidence per GRADE. When assessing by various methods of pain evaluation, such as the visual analog scale (VAS) and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), there was also low-quality evidence to support a reduction in pain with cannabis treatment.

Two randomized controlled trials found that nabilone is an effective, well-tolerated treatment option for pain reduction in fibromyalgia patients. Another randomized controlled trial and all three observational studies showed that cannabinoids improved quality of life and alleviated pain, respectively, in patients with fibromyalgia. Only one randomized controlled trial demonstrated that cannabinoids did not have a different effect than placebo on pain responses [17]. Table 4 summarizes the effects of the cannabis interventions.

Table 4.

Studies, outcomes, and conclusions.

4. Discussion

This systematic review found low-quality evidence supporting short-term pain reduction in people with fibromyalgia treated with cannabinoid therapeutics. There may be positive effects on measures of quality of life affected by this syndrome, including sleep quality [14,16], mood [11,14,18,19], libido [14,18], and appetite [14]. These improvements were largely inconsistent across studies.

Both THC and CBD use were explored as treatment options for fibromyalgia. THC has been found in studies to positively affect pain regulation, appetite, and mood [20]. CBD has been shown to have both anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving characteristics [21]. THC acts as a partial agonist on CB1 and CB2 receptors. CBD is a negative allosteric modulator of the CB1 receptor. In theory, when combined, the synergistic effects of both components could be beneficial in using cannabis as an anti-nociceptive agent [21]. However, antagonistic interactions between THC and CBD can also occur due to their varying properties.

One study explored the intricate relationship between THC and CBD using inhaled cannabis with varying dosages of both THC and CBD, including Bedrocan (22.4 mg THC, <1 mg CBD), Bediol (13.4 mg THC, 17.8 mg CBD), Bedrolite (<1 mg THC, 18.4 mg CBD), and a placebo without THC or CBD. The combination of high doses of both THC and CBD in Bediol was found to decrease spontaneous pain significantly. However, the other varieties with high THC or CBD contents did not have a more significant effect than the placebo on pain responses. Notably, Bedrolite—a cannabis variety with a high CBD content—displayed a lack of pain relief [17]. On the other hand, another study found a significant improvement in symptoms and quality of life of fibromyalgia patients, as measured by the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), using THC-rich, low-CBD-dose cannabis oil (mean dose 4.4 mg THC, 0.08 mg CBD). The authors concluded that cannabis oil offered a low-cost and well-tolerated management option for symptom relief and improved the quality of life for patients with fibromyalgia [18]. Although previous literature has reported that patients experience improvements in their chronic pain from CBD-only treatment [22,23], the findings from our review suggest that, currently, the most promising evidence is for THC as a treatment for fibromyalgia.

Further studies have been carried out to evaluate outcomes with nabilone—a synthetic analog of THC that is considered to be twice as active as THC [24]. A crossover randomized controlled trial of 31 patients treated for two weeks with each drug comparing nabilone to amitriptyline—a tricyclic antidepressant widely used to treat FM—found nabilone to be superior in improving sleep dysfunction. However, there was no effect on pain or mood [16]. The authors suggested that their findings may have been limited by the relatively short duration of drug exposure. In contrast, another RCT of 40 patients with fibromyalgia, investigating the efficacy of nabilone compared to a placebo in terms of pain reduction and quality of life improvement over a 4-week duration, described significant decreases in pain scores and anxiety [19]. Thus, it may be beneficial to design studies with an increased course of treatment in trials.

A potential downside associated with increasing the duration of treatment is an increased risk of adverse side effects. Both clinicians and patients must know that cannabinoid therapies may evoke various side effects, which is especially important given that patients with fibromyalgia are more sensitive to medications than the general population [25]. The most common side effects seen in this review included drowsiness [11,18,19], dizziness [11,14,18,19], nausea/vomiting [14], dry mouth [14,16,18,19], drug high [11,17], coughing [17], sore throat [12], tachycardia [11], conjunctival irritation [11,12], hypotension [11], and gastrointestinal symptoms [14]. No severe adverse side effects associated with cannabinoids were reported in the studies. Medical cannabis appears to be a safe alternative for treating fibromyalgia. In addition to beginning with low dosages and titration according to clinical symptoms, we recommend regular monitoring to prevent further risks—especially in the treatment of cannabis-naive patients.

In recent years, changing attitudes about marijuana have led to the use of cannabis becoming progressively more popular in medical settings, especially for conditions that have exhausted conventional therapies. Furthermore, in the context of the opioid crisis, there has been rising interest in the efficacy of cannabis use for chronic pain conditions such as chronic non-cancer pain [26], neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis [27], and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting [26,28], among others. Despite this heightened interest, there is still inconclusive and often contradictory evidence in the literature, with limited trials having been undertaken. Nevertheless, positive analgesic benefits reported by patients using cannabis to treat chronic pain are well established [29,30].

This systematic review had some limitations. First, our inclusion and exclusion criteria limited the number of studies examined and may have excluded valuable studies on this topic. Secondly, the heterogeneity of the treatments employed—in terms of chemical formulation, dosage, and route of administration—prevented us from making meaningful comparisons between studies. Furthermore, some studies observed notable attrition rates, had insufficient follow-up, and inadequately assessed clinical outcomes, preventing a high-powered robust investigation.

In conclusion, there remains a potential role for cannabinoids in the management of fibromyalgia, although current evidence is limited. Nonetheless, more research on this topic is needed to confirm the efficacy of cannabinoids, ascertain the most effective THC–CBD formulation, determine a more standardized assessment for clinical outcomes, and analyze long-term outcomes.

5. Conclusions

The use of cannabis in fibromyalgia treatment is still an area of ongoing study. CBD and THC have been studied for their potential therapeutic benefits in a variety of medical conditions with manifestations of pain and sleep disturbances. These cannabinoids interact with the body’s endocannabinoid system, which plays a role in regulating pain, mood, and other physiological processes, suggesting that they could play a role in managing the cardinal symptoms of fibromyalgia.

There remains a growing interest in the use of cannabinoids as potential treatment options for fibromyalgia. While some studies show promising results, others have been inconclusive. Overall, the effectiveness of these cannabinoids in treating fibromyalgia remains uncertain. Our investigation revealed that they may be effective in reducing pain and improving sleep in fibromyalgia patients, but more studies are needed to strengthen these findings.

The use of cannabinoids for medical purposes is still relatively new, and much is still unknown. To understand the potential benefits, risks, and optimal dosages and formulations, there is more work to be done through clinical trials. Overall, there remains a potential role for cannabinoids in the management of fibromyalgia, despite currently limited evidence. Nonetheless, more research on this topic is needed to confirm the efficacy of cannabinoids, ascertain the most effective THC–CBD formulation, determine a more standardized assessment for clinical outcomes, and analyze long-term outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines11061621/s1, Table S1. Database Search strategy. Table S2. Excluded articles.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| CBT | Cognitive behavioral therapy |

| THC | Delta-9- tetrahydrocannabinol |

| CBD | Cannabidiol |

| CB1 | Type 1 cannabinoid receptor |

| CB2 | Type 2 cannabinoid receptor |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

References

- Clauw, D.J. Fibromyalgia: A clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1547–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sluka, K.A.; Clauw, D.J. Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Neuroscience 2016, 338, 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Dukes, E.; Martin, S.; Edelsberg, J.; Oster, G. Characteristics and healthcare costs of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2007, 61, 1498–1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, R.O.; Souza, M.B.; Oliveira, M.X.; Lacerda, A.C.; Mendonça, V.A.; Henschke, N.; Oliveira, V.C. Association of Therapies with Reduced Pain and Improved Quality of Life in Patients With Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savage, S.R.; Romero-Sandoval, A.; Schatman, M.; Wallace, M.; Fanciullo, G.; Mccarberg, B.; Warell, M. Cannabis in Pain Treatment: Clinical and Research Considerations. J. Pain 2016, 17, 654–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebbert, J.O.; Scharf, E.L.; Hurt, R.T. Medical Cannabis. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2018, 93, 1842–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levinsohn, E.A.; Hill, K.P. Clinical uses of cannabis and cannabinoids in the United States. J. Neurol. Sci. 2020, 411, 116717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, V.; Bever, C., Jr.; Bowen, J.; Bowling, A.; Weinstock-Guttman, B.; Cameron, M.H.; Bourdette, D.; Gronseth, G.S.; Narayanaswami, P. Summary of evidence-based guideline: Complementary and alternative medicine in multiple sclerosis: Report of the guideline development subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2014, 82, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uberall, M.A. A Review of Scientific Evidence for THC:CBD Oromucosal Spray (Nabiximols) in the Management of Chronic Pain. J. Pain Res. 2020, 13, 399–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiz, J.; Duran, M.; Capella, D.; Carbonell, J.; Farré, M. Cannabis use in patients with fibromyalgia: Effect on symptoms relief and health-related quality of life. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e18440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin, M.; Oron, A.; Robinson, D. Effect of adding medical cannabis to analgesic treatment in patients with low back pain related to fibromyalgia: An observational cross-over single centre study. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2019, 37 (Suppl. S116), 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habib, G.; Artul, S. Medical Cannabis for the Treatment of Fibromyalgia. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2018, 24, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagy, I.; Bar-Lev Schleider, L.; Abu-Shakra, M.; Novack, V. Safety and Efficacy of Medical Cannabis in Fibromyalgia. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hershkovich, O.; Hayun, Y.; Oscar, N.; Shtein, A.; Lotan, R. The role of cannabis in treatment-resistant fibromyalgia women. Pain Pract. 2023, 23, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ware, M.A.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Joseph, L.; Shir, Y. The effects of nabilone on sleep in fibromyalgia: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Anesth. Analg. 2010, 110, 604–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Donk, T.; Niesters, M.; Kowal, M.A.; Olofsen, E.; Dahan, A.; van Velzen, M. An experimental randomized study on the analgesic effects of pharmaceutical-grade cannabis in chronic pain patients with fibromyalgia. Pain 2019, 160, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, C.; Bittencourt, P.C.T.; Pelegrini, A. Ingestion of a THC-Rich Cannabis Oil in People with Fibromyalgia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Pain Med. 2020, 21, 2212–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skrabek, R.Q.; Galimova, L.; Ethans, K.; Perry, D. Nabilone for the treatment of pain in fibromyalgia. J. Pain 2008, 9, 164–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kogan, N.M.; Mechoulam, R. Cannabinoids in health and disease. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2007, 9, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vuckovic, S.; Srebro, D.; Vujovic, K.S.; Vučetić, Č.; Prostran, M. Cannabinoids and Pain: New Insights from Old Molecules. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilling, J.M.; Hughes, C.G.; Wallace, M.S.; Sexton, M.; Backonja, M.; Moeller-Bertram, T. Cannabidiol as a Treatment for Chronic Pain: A Survey of Patients’ Perspectives and Attitudes. J. Pain Res. 2021, 14, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capano, A.; Weaver, R.; Burkman, E. Evaluation of the effects of CBD hemp extract on opioid use and quality of life indicators in chronic pain patients: A prospective cohort study. Postgrad. Med. 2020, 132, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabilone. Drug Bank Online 2005. Retrieved 6 April 2023. Available online: https://go.drugbank.com/drugs/DB00486 (accessed on 5 April 2023).

- Rehabilitation and Fibromyalgia. Medscape. Retrieved 6 April 2023. Available online: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/312778-overview (accessed on 5 February 2019).

- Whiting, P.F.; Wolff, R.F.; Deshpande, S.; Di Nisio, M.; Duffy, S.; Hernandez, A.V.; Keurentjes, J.C.; Lang, S.; Misso, K.; Ryder, S.; et al. Cannabinoids for Medical Use: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA 2015, 313, 2456–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attal, N.; Bouhassira, D. Pharmacotherapy of neuropathic pain: Which drugs, which treatment algorithms? Pain 2015, 156 (Suppl. S1), S104–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, L.A.; Azariah, F.; Lavender, V.T.; Stoner, N.S.; Bettiol, S. Cannabinoids for nausea and vomiting in adults with cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 2015, CD009464. [Google Scholar]

- Sexton, M.; Cuttler, C.; Finnell, J.S.; Mischley, L.K. A Cross-Sectional Survey of Medical Cannabis Users: Patterns of Use and Perceived Efficacy. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2016, 1, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corchero, J.; Manzanares, J.; Fuentes, J.A. Cannabinoid/opioid crosstalk in the central nervous system. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 2004, 16, 159–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).