Abstract

Breast carcinoma is the most common cancer of women in Malaysia. The most common sites of metastasis are the lung, liver, bone and brain. A 45-year-old lady was diagnosed with left invasive breast carcinoma stage IV (T4cN1M1) with axillary lymph nodes and lung metastasis. She was noted to have a cervical mass through imaging, and biopsy showed CIN III. Post chemotherapy, the patient underwent left simple mastectomy with examination under anaesthesia of the cervix, cystoscopy and staging. The cervical histopathological examination (HPE) showed squamous cell carcinoma, and clinical staging was 2A. The breast tissue HPE showed invasive carcinoma with triple receptors positivity. The patient was given tamoxifen and put on concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) for the cervical cancer. The management of each pathology of this patient involved a multi-disciplinary team that included surgeons, oncologists, gynaecologists, pathologists and radiologists. Due to the complexity of the case with two concurrent cancers, the gene expression profiles may help predict the patient’s clinical outcome.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in Malaysia, while cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer among women in Malaysia [1]. The common sites for invasive breast cancer to metastasize are the lung, liver, bone and brain [2] while for cervical cancer, the frequent metastatic sites are the lungs, extra-pelvic nodes, liver and bones [3]. The most common histological finding for cervical cancer is squamous cell carcinoma. Both breast and cervical cancers are detected late, and many cancer patients do not receive care consistent with global standards. The current literature shows rare occurrence of concurrent breast cancer with cervical cancer, probably due to the contrasting predisposing factors [4]. We present a patient with dual pathology for breast with cervical cancer and the gene expression profiles obtained following palliative chemotherapy and concurrent chemotherapy and radiation (CCRT).

2. Case Presentation

Despite breast cancer being a common cancer in Malaysia, a concurrent presentation with cervical cancer is rare. Here, we present a case with a concurrent breast and cervical cancer with additional information on gene expression profiles following palliative chemotherapy and CCRT. A 45-year-old Malay lady with a history of two miscarriages and a life birth presented with firm, non-mobile left breast lump of 8 × 4 cm with no nipple discharge. She was diagnosed with invasive carcinoma with estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive. She had no known risk factors for breast cancer such as strong family history, early menarche nor late age at first pregnancy.

The staging of the disease showed axillary lymphadenopathy (up to level III) and diffused lung nodules suggestive of metastasis (T4cN1M1-stage IV). Uterus was bulky with hematometra. Per speculum vaginal examination showed cervix with confined fleshy growth at 9 to 3 o’clock position measuring 4 × 3 cm, with contact bleeding. Punch biopsy showed cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) stage III; however, invasion could not be ruled out. The patient was started on chemotherapy including 5-fluorouracil, epirubicin and cyclophosphamide, for six cycles for the breast cancer.

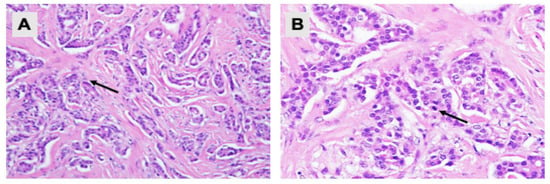

Reassessment computed tomography (CT) scan post chemotherapy for the breast cancer showed reduced breast lesion from 2.9 × 4.0 × 5.7 cm to 1.5 × 2.8 cm with no effect on the cervical mass. The patient underwent left simple mastectomy, and histopathological examination showed the same receptor status and morphological features as per biopsy (Figure 1). There were still abundant viable malignant epithelial cells with arranged tubules, cords and trabeculae pattern, exhibiting only a minor loss of neoplastic cells post neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. The final diagnosis was invasive breast carcinoma of no special type with grade 1 Modified Bloom Richardson grading system.

Figure 1.

Pathological examination of the left breast tissue. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing (A) malignant tumour cells arranged in tubules and cords (200× magnification); and (B) neoplastic cells with mild nuclear pleomorphism, round to oval nuclei, vesicular to hyperchromatic chromatin pattern and eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic activities are rarely seen (arrow) (400× magnification).

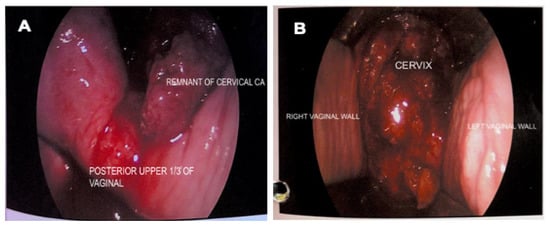

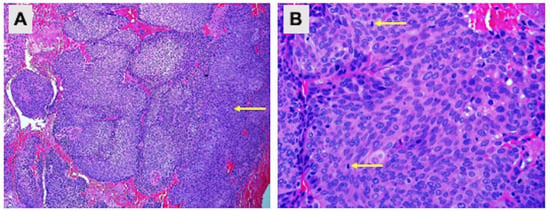

An examination under anaesthesia noted normal vulva and smooth vagina with no nodularity. However, a small raw area (1 × 1 cm) was noted at the upper 1/3 of the vagina (Figure 2A). An exophytic growth of 4 × 4 cm, occupied 9 to 5 o’clock position of the friable cervix which bled on touch (Figure 2B). Cystoscopy noted normal bladder mucosa and no evidence of tumour invasion. The assessment showed clinical staging of the cervical cancer as stage 2A. Histopathological examination of the upper 1/3 posterior vagina and cervix was consistent with human papillomavirus (HPV)-associated keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma (Figure 3). The tumour cells showed block positivity towards P16 immunohistochemical stains (not shown).

Figure 2.

Vaginal and cervical examination. (A) Remnant cervical growth and small raw area (1 × 1 cm) at posterior upper 1/3 of vagina; (B) Exophytic cervical cancer (4 × 4 cm) occupying 9 to 5 o’clock position of the cervix, was friable, and bled on touch.

Figure 3.

Pathological examination of the upper 1/3 posterior vagina and cervix. Hematoxylin and eosin staining showing (A) cell carcinoma infiltration (100× magnification) and (B) cells with enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli and moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm. Mitotic activities are brisk (arrow) (400× magnification).

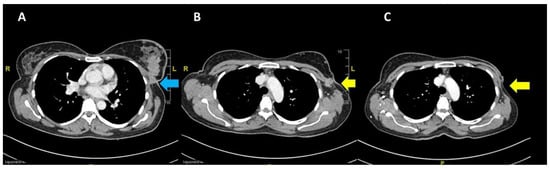

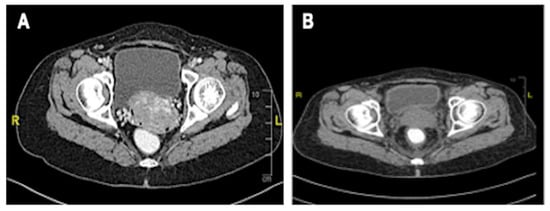

The patient was started on tamoxifen therapy for the breast cancer. A CT scan at 2 months post-op showed no local recurrence of the left breast carcinoma nor contralateral involvement, and showed resolution of the lung metastasis (Figure 4). However, the cervical carcinoma size increased with adjacent inflammatory changes, consistent with progressive disease (Figure 5A). No pelvic lymphadenopathy and no distant metastases in the abdomen were noted. The patient then completed CCRT consisting of 25 fractions of external beam radiation and weekly cisplatin 40 mg/m2, with additional 8 fractions of external beam radiation as booster. The size of the cervix was consequently reduced (Figure 5B); no tumour mass was noted on the cervix and vagina. In addition, no malignant cells were observed in the cervical smear.

Figure 4.

Pre-chemotherapy CT scan showing (A) the primary breast lesion (blue arrow) and (B) the level of arch of the aorta (yellow arrow indicates fixed nodes to the pectoral muscle laterally); (C) post mastectomy at 2 months showing no local recurrence at the left breast.

Figure 5.

CT scan of the cervix. (A) Increased size of cervical mass post chemotherapy for breast cancer, no clear plane with the urinary bladder; (B) Reduced size of cervix and clear bladder plane post-CCRT.

3. Gene Expression Profiling

Blood samples were obtained from the patient two months post mastectomy, after completion of the palliative therapy (Sample 1) and following completion of the CCRT (Sample 2). At this stage, the patient was considered cancer-free. Blood samples were collected in TempusTM Blood RNA Tubes (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the total RNA was extracted using a TempusTM Spin RNA Isolation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Gene expression analysis was then performed using the nCounter® SPRINT Profiler (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA), in triplicates. A total of 625 genes were profiled for Samples 1 and 2, against seven normal control samples. The control subjects were female of more than 40 years old, with no family cancer history or other critical or chronic diseases and were not on any medication.

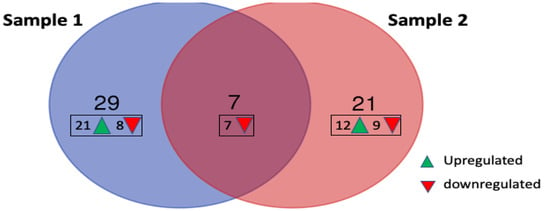

Data for all samples were processed and normalized using nSolver analysis software (version 4.0, NanoString Technologies, USA) followed by differential gene expression analysis using advanced nSolver analysis. Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) with a two-fold change or more are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2. Gene annotations were obtained from NCBI gene ID “https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/ (assessed on 27 March 2022)”. CEBPE (CCAAT/enhancer binding protein, epsilon), CD24 and CLC (Charcot-Leyden crystal) genes were highly upregulated in Sample 2 with 5-, 5.9- and 6.8-fold change, respectively. Results also show that both Sample 1 and Sample 2 display different gene profiles with only seven genes that are commonly downregulated in both (Figure 6). Two of these genes, CHI3L1 (Chitinase-3 like-protein-1) and DEFA1 (Defensin Alpha 1), were further downregulated in Sample 2 compared to Sample 1 (from 6.6- to 8.9-fold and 2.2- to 8.5-fold, respectively).

Table 1.

DEGs after completion of palliative chemotherapy and mastectomy (Sample 1).

Table 2.

DEGs following completion of CCRT, and patient is tumour-free (Sample 2).

Figure 6.

Number of upregulated and downregulated genes in patient samples 1 and 2 compared to the control group. Seven of the genes were downregulated in both samples, but none of the upregulated genes were similarly observed in both.

4. Discussion

Based on the Malaysian National Cancer registry report, the incidence of female breast cancer has been increasing from 18,206 in 2007–2011 to 21,634 in 2012–2016, accounting for 34.1% of all cancers among females [5]. Delay in seeking medical examination of breast symptoms is a significant problem associated with a lower breast cancer survival rate [6]. The delay in presentation is multifactorial, but some documented reasons include the use of alternative therapy, breast ulcer, palpable axillary lymph nodes, false-negative diagnostic test, non-cancer interpretation and negative attitude towards treatment [7]. Diagnosis is conducted with triple assessment, namely clinical, imaging and tissue biopsy. Surgical management of invasive breast carcinoma with axillary lymph node involvement requires breast conservation or mastectomy and axillary clearance. National comprehensive cancer network (NCCN) guidelines recommend neoadjuvant systemic therapy in women with inoperable breast cancer. It can render inoperable cancer to resectable cancer [8]. The role of chemotherapy, radiotherapy or hormonal therapy depends on the size of the primary tumour, the receptor status and nodal involvement [8]. According to the St. Gallen Consensus 2011, molecular subtypes of breast cancer can be classified into Luminal A (ER+/PR+/HER2-/lowKi-67); Luminal B (ER+/PR+/HER2-/+/high Ki-67); HER2-overexpression (ER-/PR-/HER2+); and triple negative breast cancers/TNBCs (ER-/PR-/HER2-). The basal-like subtype of breast cancer referred to as TNBC was found to be positive for basal marker (CK5/6) expression [9]. The prognosis is poorer in triple negative and HER2-enriched disease. The paradigm had shifted in these two subtypes in which the early-stage disease patients are subjected to neoadjuvant systemic therapy prior to surgery [10]. Hormonal therapy with the selective ER modulator, tamoxifen, is indicated for hormone receptor-positive patients and can be used in both premenopausal and post-menopausal women. On the other hand, selective aromatase inhibitors such as anastrozole and letrozole can be used as hormonal therapy for post-menopausal women [11]. Patients positive for ER, PR and HER2 are usually treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with adjuvant endocrine therapy, as well as an additional targeted therapy with trastuzumab for the HER2 positivity.

The case reported herein is an invasive breast carcinoma with luminal B triple positivity subtype, which is a common pathology in breast carcinoma. However dual pathology in a patient with both breast and cervical carcinoma is rare [4]. The patient had metastatic disease with the presence of lung nodules. She was therefore subjected to palliative chemotherapy to reduce the size of the tumour, axillary lymph node and lung nodules, after which she underwent mastectomy with axillary clearance. Patients with ER- and PR-positive breast carcinoma have improved prognosis with palliative chemotherapy, and evidence indicates that hormonal therapy for these patients also improves their quality of life [12].

There is currently no clear association between breast and cervical cancer. For cervical cancer, the management is based on the cancer stage, grade and histopathological type as well as general status of the patient. The treatment may include surgical resection, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or their combination. Our patient was also diagnosed with stage 2A cervical cancer and was counselled for radical hysterectomy. However, the patient refused surgical intervention in view of on-going chemotherapy for her breast cancer. Hence, the patient was given concurrent chemoradiation as the primary treatment for her cervical cancer. Primary chemoradiation is now often used to treat locally advanced cervical cancer, similar to that seen in this patient [13]. The treatment is based on combination therapy with platinum-based regimens and radiation that involves external beam and high-dose intracavity brachytherapy. Post-treatment hysterectomy is not associated with increased survival rates, and, therefore, it is generally not recommended [14]. However, hysterectomy may be performed in patients who have large, bulky tumours or high post-treatment tumour volumes [15].

Advances in genomics have paved the way for further understanding of cancer progression, and the identification of specific genomic patterns could help in diagnosis, prognosis and prediction of treatment response. Cluster of differentiation (CD) markers have a role in cancer diagnosis, choice of treatment and therapeutic monitoring. For example, CD24 is highly expressed in various cancers but is rarely expressed in normal tissues [16,17]. CD24 is a small mucin-like antigen on the cell surface with highly variable glycosylation [18]. The expression of CD24 was reported as an independent, unfavourable prognostic factor for disease-free survival of breast cancer patients [16], especially for those with luminal A and triple-negative subtypes [19]. Its high expression is also associated with aggressive breast cancer and poor survival of early-stage breast cancer patients [19]. Herein, CD24 is also upregulated in our patient with luminal B triple positivity subtype, following CCRT, and this could be associated with poor prognosis. Interestingly, CD24 transcription is regulated by ERalpha in breast cancer cells [20]. The expression of CD177 is reduced in our patient, which could also predict poor outcome. CD177 expression has been reported to be associated with a better prognosis in breast and other cancers [21]. CD177 is expressed in tumour-infiltrating, regulatory T (Treg) cells in breast, renal, lung and colorectal cancers. Treg cells suppress a variety of immune cells to maintain homeostasis and peripheral tolerance, and attenuation of this suppressive activity is associated with an increased anti-tumour immune response [22].

On the other hand, the expression of the transcription factor for granulocyte differentiation, CEBPE, was highly upregulated in our patient upon completion of CCRT. Datasets analysis indicates that CEBPE expression predicts better survival rate for patients with acute myeloid leukaemia [23]. CLCs are normally associated with eosinophilic diseases and have a role in type 2 immunity [24]. An upregulation of the CLC gene in the current patient may thus indicate an increased tissue-level defence mechanism against the cancer.

The expression of CHI3L1 and DEFA1 was downregulated after palliative chemotherapy and then further reduced following CCRT. CHI3L1 signalling promotes tumour progression by promoting cancer cell growth, proliferation, migration, invasion, metastasis, angiogenesis, activation of tumour-associated macrophages and Th2 polarisation of CD4+ T cells [25,26]. Increased CHI3L1 levels in breast and gastric cancer patients promote lung metastasis via activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signalling and upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) genes [27]. Rusak et al. [28] further reported a positive correlation between CHI3L1 expression and markers of angiogenesis in invasive ductal breast carcinoma, with higher expression observed in triple-negative cases. Hence, considering the significant role of CHI3L in cancer progression and metastasis, the low CHI3L1 expression in the current patient reflects an effective treatment. The expression of DEFA1 was also further reduced following CCRT. DEFA1 belongs to the α-defensin family that possesses antimicrobial and immunomodulatory functions, as well as antitumour activities [29]. DEFA1 and DEFA3 encode human neutrophil peptides, HNP1-3 [30], which contribute to tumour progression and invasion and, hence, are often detected in elevated levels in cancer patients [29]. The expression of DEFA1 and DEFA3 RNA transcripts in blood has been associated with improved response to docetaxel therapy in castration-resistant prostate cancer, suggesting their predictive value for the selection of personalized therapy [31].

The mainstay management of invasive breast carcinoma with axillary lymph node is surgical intervention through removal of the primary tumour with clear margins and axillary surgery. Locally advanced and metastatic diseases are given systemic neoadjuvant chemotherapy to reduce the size of the primary tumour and metastatic nodules for the surgical intervention decision. Responsive primary tumours have shown survival benefits.

In cervical cancer, therapeutic approaches must be carefully tailored to obtain the best outcome for each patient. The treatment options for early stage of the disease involve surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. However, in advanced stage (Stage 2B and above), the treatment is limited to radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

5. Conclusions

Patients with both conditions need to be addressed carefully. The prognosis of each individual disease should be considered prior to a decision for definitive treatment. The above patient had stage IV breast cancer and stage 2A cervical cancer. She had undergone aggressive treatment for both conditions, and the one-year post-treatment showed no progression of disease. The genetic findings are by no means conclusive, but the expression profile of a combination of different genetic markers may be useful in the selection of personalized therapy as well as in predicting long-term survival outcome.

Author Contributions

Patient clinical management, clinical data interpretation and manuscript writing, M.M.Y., M.P.I., S.R. and M.N.K.; pathological data analysis and interpretation and photo images, A.A. and N.B.C.I.; subject recruitment, data acquisition, and manuscript writing, review and editing, C.L.W.; sample preparation and gene expression profiling, Z.M.A.; project coordination, funding and resource, S.K.T.; datasets analysis, and manuscript writing, review and editing, S.M.-S.; study conception, project coordination, funding and resource, and manuscript writing, review and editing, N.S.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by ALPS Biotech Sdn. Bhd., awarded to Universiti Sains Malaysia, grant number 304/PPSP/6150184/A150.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Human Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Sains Malaysia (approval no. USM/JEPeM/20050259).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Thouvenot, A.; Bizet, Y.; Baccar, L.S.; Lamuraglia, M. Primary breast cancer relapse as metastasis to the cervix uteri: A case report. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 9, 96–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, L.; Han, B.; Siegel, E.; Cui, Y.; Giuliano, A.; Cui, X. Breast cancer lung metastasis: Molecular biology and therapeutic implications. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2018, 19, 858–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cholmondeley, K.; Callan, L.; Sangle, N.; D’Souza, D. Metastatic cervical adenocarcinoma to the breast: A case report and literature review. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 2019, 28, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padegaonkar, A.; Chadha, P.; Shetty, A. A rare case of synchronous cervical and breast carcinoma. Indian J. Surg. Oncol. 2018, 9, 622–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azizah, A.M.; Hashimah, B.; Nirmal, K.; Siti Zubaidah, A.R.; Puteri, N.A.; Nabihah, A.; Sukumaran, R.; Balqis, B.; Nadia, S.M.R.; Sharifah, S.S.S.; et al. Malaysia National Cancer Registry Report (MNCR) 2012-2016; National Cancer Institute: Putrajaya, Wilayah, 2019; pp. 1–116. [Google Scholar]

- Norsa’adah, B.; Rampal, K.G.; Rahmah, M.A.; Naing, N.N.; Biswal, B.M. Diagnosis delay of breast cancer and its associated factors in Malaysian women. BMC Cancer 2011, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meechan, G.; Collins, J.; Petrie, K.J. The relationship of symptoms and psychological factors to delay in seeking medical care for breast symptoms. Prev. Med. 2003, 36, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Breast Cancer; Version 3; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhirsch, A.; Winer, E.P.; Coates, A.S.; Gelber, R.D.; Piccart-Gebhart, M.; Thürlimann, B.; Senn, H.J.; Albain, K.S.; André, F.; Bergh, J.; et al. Personalizing the treatment of women with early breast cancer: Highlights of the St Gallen International Expert Consensus on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer 2013. Ann. Oncol. 2013, 24, 2206–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Breast Cancer; Version 4; National Comprehensive Cancer Network: Plymouth Meeting, PA, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Robert, N.J.; Denduluri, N. Patient case lessons: Endocrine management of advanced breast cancer. Clin. Breast Cancer 2018, 18, 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, D.; Ravi, B.; Kumar, N.; Chattopadhyay, D.; Syed, A.; Joshi, P. Invasive ductal carcinoma of breast and squamous cell carcinoma of anterior chest wall—A rare collision. Clin. Case Rep. 2020, 8, 1618–1621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chemoradiotherapy for Cervical Cancer Meta-Analysis Collaboration. Reducing uncertainties about the effects of chemoradiotherapy for cervical cancer: Individual patient data meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wang, X.; Tian, J.H.; Yang, K.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L.; Hao, X.Y. High dose rate versus low dose rate intracavity brachytherapy for locally advanced uterine cervix cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokka, F.; Bryant, A.; Brockbank, E.; Powell, M.; Oram, D. Hysterectomy with radiotherapy or chemotherapy or both for women with locally advanced cervical cancer. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2015, 7, CD010260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristiansen, G.; Sammar, M.; Altevogt, P. Tumour biological aspects of CD24, a mucin-like adhesion molecule. J. Mol. Histol. 2004, 35, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, E.S.; Kim, Y.S. CD24 overexpression in cancer development and progression: A meta-analysis. Oncol. Rep. 2009, 22, 1149–1156. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, X.; Zheng, P.; Tang, J.; Liu, Y. CD24: From A to, Z. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2010, 7, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, M.J.; Han, J.; Seo, J.H.; Song, K.; Jeong, H.M.; Choi, J.-S.; Kim, Y.J.; Lee, S.-H.; Choi, Y.-L.; Shin, Y.K. CD24 Overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in Luminal A and triple-negative breast cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0139112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaipparettu, B.A.; Malik, S.; Konduri, S.D.; Liu, W.; Rokavec, M.; van der Kuip, H.; Hoppe, R.; Hammerich-Hille, S.; Fritz, P.; Schroth, W.; et al. Estrogen-mediated downregulation of CD24 in breast cancer cells. Int. J. Cancer 2008, 123, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluz, P.N.; Kolb, R.; Xie, Q.; Borcherding, N.; Liu, Q.; Luo, Y.; Kim, M.C.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Cancer cell-intrinsic function of CD177 in attenuating β-catenin signaling. Oncogene 2020, 39, 2877–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.C.; Borcherding, N.; Ahmed, K.K.; Voigt, A.P.; Vishwakarma, A.; Kolb, R.; Kluz, P.N.; Pandey, G.; De, U.; Drashansky, T.; et al. CD177 modulates the function and homeostasis of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Du, Y.; Wei, D.Q.; Zhang, F. CEBPE expression is an independent prognostic factor for acute myeloid leukemia. J. Transl. Med. 2019, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aegerter, H.; Smole, U.; Heyndrickx, I.; Verstraete, K.; Savvides, S.N.; Hammad, H.; Lambrecht, B.N. Charcot–Leyden crystals and other protein crystals driving type 2 immunity and allergy. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2021, 72, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, T.; Su, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; You, Q. Chitinase-3 like-protein-1 function and its role in diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Q.C.; Wang, L.; Jin, S.S.; Liu, G.F.; Liu, J.; Ma, L.; Mao, R.F.; Ma, Y.Y.; Zhao, N.; Chen, M.; et al. CHI3L1 promotes tumor progression by activating TGF-β signaling pathway in hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X. Tumor-recruited M2 macrophages promote gastric and breast cancer metastasis via M2 macrophage-secreted CHI3L1 protein. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2017, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusak, A.; Jablonska, K.; Piotrowska, A.; Grzegrzolka, J.; Nowak, A.; Wojnar, A.; Dziegiel, P. The role of CHI3L1 expression in angiogenesis in invasive ductal breast carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2018, 38, 3357–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Lu, W. Defensins: A double-edged sword in host immunity. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganz, T. Defensins and host defense. Science 1999, 286, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, M.; Young, C.Y.; Tindall, D.J.; Nandy, D.; McKenzie, K.M.; Bevan, G.H.; Donkena, K.V. Whole blood defensin mRNA expression is a predictive biomarker of docetaxel response in castration-resistant prostate cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2015, 8, 1915–1922. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).