Abstract

Olfactory dysfunction (OD) is an early symptom associated with a variety of diseases, including COVID-19, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease, where patients commonly experience hyposmia or anosmia. Effective restoration of olfactory function is therefore crucial for disease diagnosis and management, and improving overall quality of life. Traditional treatment approaches have primarily relied on medication and surgical intervention. However, recent advances in bionic sensing and brain–computer interface (BCI) technologies have opened up novel avenues for olfactory rehabilitation, facilitating the reconstruction of neural circuits and the enhancement of connectivity within the central nervous system. This review provides an overview of the current research landscape on OD-related diseases and highlights emerging olfactory restoration strategies, including olfactory training (OT), electrical stimulation, neural regeneration, and BCI-based approaches. These developments lay a theoretical foundation for achieving more rapid and reliable clinical recovery of olfactory function.

1. Introduction

Although humans predominantly rely on vision, hearing, and touch, the sense of smell also plays a crucial role in how we perceive the world [1]. The olfactory system can detect a vast range of odorants [2]. These odorants are emitted from a source, transported through the air, and provide information to an organism through olfactory perception [3].

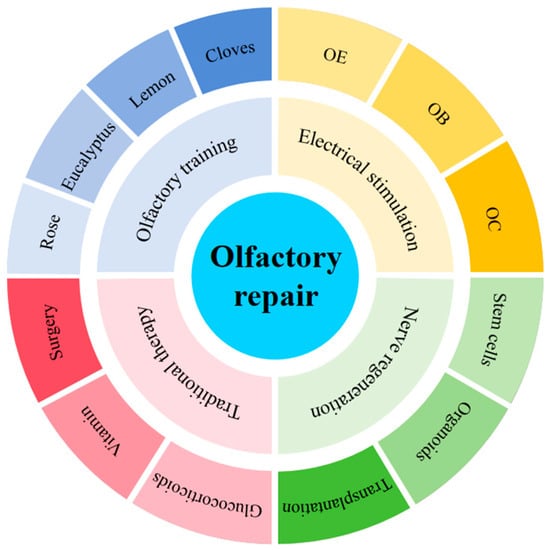

This review outlines the pathological mechanisms of OD, emphasizing emerging interventions such as olfactory training, electrical stimulation, and neural regeneration (Figure 1). It also explores the potential of brain–computer interfaces in olfactory rehabilitation, aiming to broaden therapeutic strategies in clinical practice.

Figure 1.

Methods for repairing and enhancing olfactory function. OE: olfactory epithelium; OB: olfactory bulb; OC: olfactory cortex. Rose, Eucalyptus, Lemon, Cloves: classic olfactory training odorant [rose (phenylethanol), clove (eugenol), eucalyptus (eucalyptol), lemon (citronellal)].

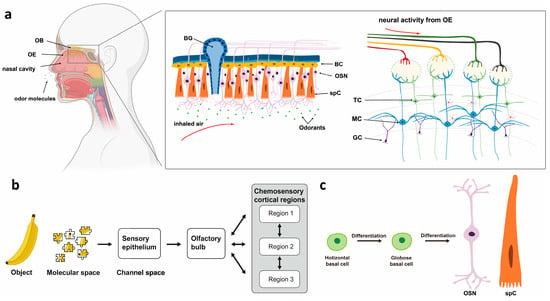

The human olfactory system is primarily composed of the olfactory epithelium (OE), olfactory bulb (OB), and olfactory cortex (OC). It underpins a wide range of functions, from basic survival to complex cognitive processes, through intricate neural mechanisms [4] (Figure 2). Olfactory information is first detected by olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) in the OE of the nasal cavity [5,6,7]. OSNs relay signals to the OB, which contains two types of projection neurons: mitral cells (MCs) and tufted cells (TCs) [8]. From the OB, MCs and TCs send information to several olfactory cortical areas in the brain [9]. The olfactory cortex refers to areas receiving direct input from the OB, including 9 major OC: anterior olfactory nucleus (AON), olfactory tubercule (OT), anterior piriform cortex (aPir), posterior piriform cortex (pPir), lateral entorhinal cortex (LEC), nucleus of the lateral olfactory tract (nLOT), anterior cortical amygdaloid nucleus (ACo), posterolateral cortical amygdaloid nucleus (PLCo) and tenia tecta (TT) [10,11]. TCs mainly signal to the anterior olfactory cortex (e.g., AON and OT), while MCs—regarded as the OB’s main output neurons—project to OC [9,12]. The OE, OB, and OC reflect the sensitivity, discriminatory capacity, and memory functions of the olfactory system, respectively [13].

Olfactory information not only reflects the chemical composition of the surrounding environment and guides behaviors such as foraging, escaping, and courtship, but is also closely linked to learning [14], declarative memory [15], emotion [16], and spatial navigation [17]. Studies have shown that the human olfactory system possesses remarkable discriminatory capabilities. It can distinguish over a trillion different odors through the activation of hundreds of distinct olfactory receptors, far exceeding the resolution of other sensory modalities [18]. Olfactory dysfunction (OD) can impair environmental alertness, reduce the enjoyment of eating, and weaken emotional resonance, thereby adversely affecting quality of life and social behavior. Despite recent advances in OD research, clinical treatment options remain limited, mostly involving medications, such as glucocorticoids and vitamins, and surgery (to correct nasal abnormalities) [19]. Effective treatments for inflammation-induced olfactory damage are still lacking.

2. Overview of OD

OD is a common disorder, with an estimated prevalence of 22.2% in the general population [20]. OD denotes impaired olfactory function, including partial or complete loss or qualitative distortions. Clinically, OD mainly manifests as hyposmia, anosmia, parosmia (distorted perception of an odor stimulus), phantosmia (an odor is perceived without a concurrent stimulus), and hyperosmia. Epidemiological studies indicate that the prevalence of OD in the general population is approximately 3.8% to 5.8%, increasing significantly with age and being higher in males than in females [21,22].

Because the nasal neuroepithelium is a direct appendage of the central nervous system in communication with the external environment without the protection of the blood–brain barrier (BBB), many factors can affect the sense of smell [23,24]. OD can be classified into six primary disease categories [25,26]: ① Congenital OD (e.g., Kallmann syndrome and underdevelopment of the OB [27])—Genetic mutations disrupt embryonic OSNs migration, causing OB underdevelopment and impaired olfactory signal processing. ② post-infectious OD (e.g., upper respiratory tract infections [28] and COVID-19 [29,30])—Pathogens damage ORNs and induce inflammation, leading to OD; ③ Nasal and paranasal sinus diseases (e.g., nasal polyps [31,32], allergic rhinitis [33,34,35], chronic rhinosinusitis(CRS) [36,37,38,39])—Polyps block odor access; rhinitis/CRS releases mediators to damage ORNs and reduces cilia density. ④ Systemic diseases (e.g., diabetes [40], systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [41,42], HIV infection [43], multiple sclerosis [44])—Olfactory dysfunction arises from two principal pathways: circulatory abnormalities, which cause ischemic and hypoxic damage, and immune abnormalities, which directly compromise olfactory tissue or facilitate pathogen invasion. ⑤ Post-traumatic OD (olfactory nerve transection [45])—Trauma severs olfactory nerve fibers, hindering regenerated ORN axon-OB glomerulus reconnection. ⑥ Neurodegenerative diseases (Parkinson’s disease (PD) [46,47], Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [46,48], Huntington’s disease (HD) [49])—PD has α-synuclein aggregation; AD has Aβ plaques/tau tangles; HD has mutant huntingtin aggregation—all cause neuronal death and OD.

Irreversible OD may result from persistent inflammation or severe injury, with mechanisms including morphological alterations and decreased counts of OSNs [50]. Physiological aging also contributes to olfactory decline [24]. Among neurodegenerative diseases, approximately 90% of early-stage PD patients exhibit OD, which is associated with abnormal dopaminergic cell expression in the OB [47]. Similarly, about 85% of early-stage AD patients show OD, linked to cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers [48]. In contrast, HD patients experience a progressive deterioration of olfactory function [49]. Although odor identification tests can assist in early screening for neurodegenerative diseases, their diagnostic specificity remains limited [51]. Additionally, OD has been found to exhibit a bidirectional relationship with psychiatric disorders such as depression, anxiety, and bipolar disorder [52,53]. Moreover, olfactory deprivation may induce emotional disturbances [54], suggesting complex interactions between the olfactory system and emotion regulation networks.

OD is an early biomarker of neurological and chronic diseases, driven by neuroinflammation, reduced synaptic plasticity, and impaired neurogenesis. Its progressive nature and impact on quality of life underscore the need for early detection and intervention. Emerging therapies—olfactory training, electrical stimulation, stem cell treatment, and microenvironment modulation—offer promising avenues for symptom relief and targeted management.

Figure 2.

Descriptive anatomy of odorant signal transmission and the human olfactory system. (a) Schematic configuration of the human olfactory system. OB: olfactory bulb; OE: olfactory epithelium; BC: basal cell; OSN: olfactory sensory neuron; spC: support cell; TC: tufted cell; MC: mitral cell; GC: granulosa cell. (b) Odor molecules activate sensory neurons in the olfactory epithelium, which project to the olfactory bulb and then to broader olfactory cortex regions [11]. (c) The differentiation ability of basal cells.

3. Olfactory Training

Olfactory training (OT), a relatively complete treatment method for olfactory disorders, was first developed by the Hummel group [55]. It involves repeated short-term exposure to a group of specific odors [rose (phenylethanol), clove (eugenol), eucalyptus (eucalyptol), lemon (citronellal)]. This method is also known as the Classical OT protocol. In recent years, OT has emerged as a key non-pharmacological intervention for OD, owing to its simplicity, safety, and broad applicability [56]. Studies have shown that classical OT can improve olfactory function in 20–30% of patients with smell loss of various etiologies [57], with subjective olfactory perception enhanced after at least 28 days of training [58]. The mechanism is believed to involve the reconstruction of olfactory pathways [59].

OT has shown efficacy across a range of OD etiologies, including post-infectious OD [60,61], COVID-19 related OD [58,62,63,64], PD [61,65], dementia [66], post-traumatic OD [61,65], and older (healthy) people [67,68,69]. It has been shown to enhance both odor identification and discrimination [61,70,71]. In addition, OT may also promote OE repair and receptor regeneration [72]. Notably, the improvement of olfaction in hyposmia is faster than that in anosmia [58].

Although OT can improve subjective olfactory perception in COVID-19 patients, its objective efficacy remains inconsistent, and clear evidence of superiority is lacking [73,74,75,76]. Considerable heterogeneity exists in current OT protocols, prompting efforts to optimize and standardize training approaches. Table 1 summarizes representative studies employing different OT protocols, highlighting variations in participant populations, duration, frequency, and odorant types. The etiologies of olfactory dysfunction are listed; however, the severity levels were not uniformly reported across studies. Recent studies have integrated OT with multisensory stimulation, such as visual and auditory cues, to develop enhanced training protocols, which have shown greater therapeutic potential compared to classical OT [77,78]. In healthy individuals, OT has a limited impact on olfactory function [79]; however, in patients with post-traumatic anosmia (PTA), it has shown significant effects on neural plasticity. Specifically, modified OT enhances functional connectivity between the medial orbitofrontal cortex and regions such as the anterior cingulate cortex, piriform cortex, and caudate nucleus, whereas classical OT tends to activate the insula and precentral gyrus. Both protocols induce distinct patterns of brain functional reorganization [80].

Table 1.

Summary of Olfactory Function Restoration Based on Olfactory Training.

In summary, OT remains a cornerstone in OD rehabilitation and a valuable model for studying olfactory neuroplasticity. However, its long-term effectiveness, optimal training parameters, and mechanistic underpinnings warrant further investigation. Future studies should focus on elucidating neural correlates of recovery and developing standardized, individualized protocols that address current limitations in efficacy and reproducibility.

4. Electrical Stimulation

Electrical stimulation represents a promising intervention for OD. Ottoson [81] first showed that stimulating frog olfactory mucosa (OM) induces potential changes in OSNs and OB. This finding provided indirect evidence that central stimulation could bypass peripheral neuronal damage, a strategy that has been successfully applied in the auditory system (e.g., in cochlear implants) [82,83]. This section reviews the research on electrical stimulation of olfactory regions, aiming to assess its potential for clinical translation.

Straschill [84] found OM stimulation suppressed perception of external odors without evoking smell sensations. Ishimaru [85] demonstrated that electrical stimulation of the human OM elicited evoked potentials in the frontal region without inducing any conscious smell perception. In a study involving 50 cases of nasal electrical stimulation, found that although non-olfactory sensations could be induced and interactions with olfactory pathways occurred, odor perception was never achieved [86]. In summary, current evidence indicates that direct electrical stimulation of the OM can activate olfactory perceptual pathways but is insufficient to elicit specific odor recognition.

In contrast, electrical stimulation of the OB has demonstrated greater potential in experimental studies. Arrays of stimulating electrodes can selectively activate OB regions, producing neural activity patterns that replicate natural olfaction [87,88]. Direct stimulation of the deafferented OB was effective in generating localized field potential responses [89]. Studies have shown the induction of specific odor perceptions through transethmoid electrical stimulation of the OB (e.g., onion, fruity scents), providing proof of concept for olfactory neuroprosthetics [90]. Strickland [91] demonstrated that direct OB stimulation can activate specific odor maps, replicating natural odor responses. Clinically, the optimal approach is endoscopic electrode implantation via the olfactory tract or frontal sinus. Electrode placement under the cribriform plate, extracranially, or intracranially achieves an optimal balance among surgical safety, procedural complexity, and stimulation efficacy [92]. Combining microelectrodes with machine learning may advance OD treatment.

Additionally, stimulation of cerebral cortex regions such as the orbitofrontal cortex and insula can also evoke olfactory perceptions. Stimulation of the areas medial to the medial orbital sulci triggered olfactory hallucinations [93]. Moreover, stimulation of the cortex of the olfactory sulcus, medial orbital sulcus, or medial orbitofrontal gyrus matter elicits specific pleasant olfactory hallucinations, with odor characteristics modulated by stimulation intensity [94]. Furthermore, a study demonstrated that stimulation of the human insular cortex activates olfactory, gustatory, and somatosensory representations, suggesting the presence of multimodal sensory integration [95]. In general, olfactory hallucinations are induced by stimulation proximal to the olfactory bulbs or tracts. These findings reveal a distributed coding mechanism of olfactory information in higher cortical areas, providing new directions for olfactory restoration strategies.

Electrical stimulation shows promise for treating olfactory dysfunction by activating olfactory pathways and evoking odor sensations. Yet, limited precision, unclear neural coding, and surgical risks hinder translation. Future research should develop minimally invasive, closed-loop systems to improve specificity, safety, and clinical applicability.

5. Nerve Regeneration

The mammalian olfactory system possesses a unique lifelong regenerative capacity, primarily supported by two types of basal cells: the mitotically active globose basal cells (GBCs) and the quiescent horizontal basal cells (HBCs) [96]. Under physiological conditions, GBCs continuously generate new olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs), which undergo an immature stage characterized by the expression of key transcription factors and metabolic regulators, and eventually reach terminal maturation through the monoallelic expression of a single odorant receptor gene [97]. Upon epithelial injury, quiescent HBCs are activated and differentiate into GBCs, which in turn regenerate neurons and other cell types of the olfactory epithelium [98,99].

5.1. Stem Cell of Olfaction

Recent studies have shown that OSN regeneration is regulated by multiple signaling pathways. The CXCR4/CXCL12 axis maintains neurogenesis by balancing self-renewal and differentiation of GBCs [100]. P63, a key regulator of HBC quiescence and activation, is downregulated during epithelial injury, leading to the activation of HBCs for tissue repair [101]. Mouse, rat, and human HBCs can be cultured and passaged in vitro as P63+ multipotent cells, exhibiting characteristics highly similar to those of in vivo HBCs [102]. However, under pathological conditions, persistent inflammation induces a shift in HBCs from a regenerative to an immune defense state via the NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby suppressing their regenerative capacity [103]. Lgr5+ GBCs exhibit features of cycling stem cells, including Ki67 expression and EdU incorporation [104]. Their regenerative potential declines with age but can be restored through activation of the Notch signaling pathway [105]. Notch signaling dynamically regulates the proliferation and differentiation of Lgr5+ cells to maintain olfactory epithelial homeostasis and facilitates the conversion of HBCs into progenitor cells following injury [106].

The mammalian olfactory system shows strong neuroplasticity and regenerative ability. Adult OE contains neurogenic cells, with more immature neurons than rodents [107]. Transgenic mice reveal that neuronal loss accelerates cellular turnover, though regeneration declines with age [108]. New OSNs axons accurately target the OB, restoring connections vital for odor recognition and memory [109,110,111]. Due to their short lifespan (1–3 months) and environmental exposure, ongoing neurogenesis is essential for epithelial maintenance and repair [97,112]. Odor stimuli selectively regulate OSNs subpopulations [113], and region-specific differentiation of progenitor cells suggests spatial control of regeneration [114]. OSNs’ cell bodies in the OM are modulated by dopamine [115], while their axons link peripheral and central systems, possibly mediating environmental effects on the central nervous system [116]. OSNs regeneration completes within 1–2 months after injury [117,118]. HBCs promote post-inflammatory repair by activating GBCs’ proliferation via ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) signaling [119]. Automated high-throughput tools now allow precise in vitro OSN regeneration quantification, advancing regenerative research [120]. Together, these findings highlight a complex, multilayered olfactory regeneration process from molecular control to functional recovery.

5.2. Olfactory Organoids

In 1946, Smith and Cochran first used the term ‘organoid,’ which means ‘resembling an organ,’ to describe a case of cystic teratoma [121]. However, now the term ‘organoid’ has a more restricted definition, i.e., organoids are self-assembled in vitro 3D structures, primarily generated from primary tissues or stem cells such as adult stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), and embryonic stem cells (ESCs). Their formation relies on cell self-assembly and differentiation, plus signals from the extracellular matrix (ECM) and the conditioned media [122]. The characteristics of the organoid depend on the starting cell type. This organoid technology, with its ability to mimic specific tissue structures, has also been applied to the study of the olfactory system.

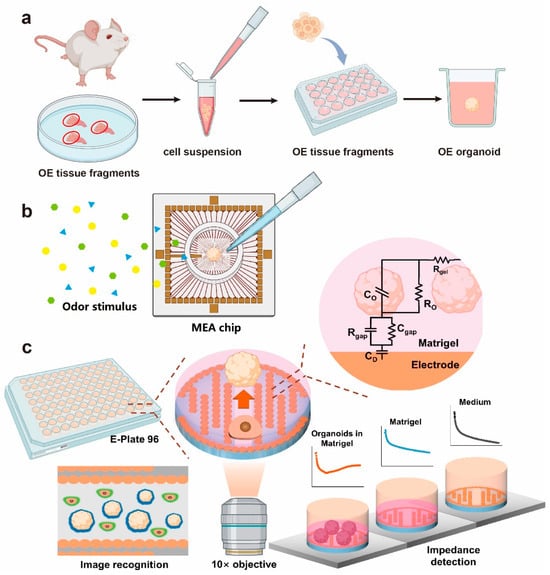

Richard [123] showed that olfactory progenitor cells cultured in 3D form multilineage colonies and integrate with host tissue, resembling natural OE, while cells grown in 2D lose this ability, emphasizing the importance of 3D structure. Ren [124] established an OE organoid model, emphasizing that VPA and CHIR99021 promote Lgr5+ stem cell proliferation and LY411575 induces mature neuron differentiation, with the TGF-β pathway as a key therapeutic target. Additionally, Chil4 from OE supporting cells aids regeneration by modulating inflammation [125], and Egr1 overexpression reverses regenerative deficits in aged mouse organoids [126]. However, abnormal MMP and EGFR expression impair organoid growth and HBC activation [127] (Figure 3a). Wang [128] further constructed biomimetic olfactory organoid models through small molecule screening and marker analysis, providing a novel platform for olfactory disease modeling and treatment.

Traditional 2D electrodes have a mechanical mismatch and low signal acquisition efficiency, where 3D electrodes offer better biocompatibility and advantages in organoid research and in vitro monitoring [129]. Our team [130] created an olfactory organoid-on-a-chip biosensor by integrating 3D-cultured olfactory organoids with a microelectrode array (MEA) chip, enabling a high-fidelity odor recognition through neural decoding (Figure 3b). Flexible electrodes implanted in live mammals enabled long-term stable electrophysiological recording of the olfactory system [131]. We also optimized high-throughput, uniform olfactory stem cell–derived organoid cultures [132], and developed a multimodal monitoring platform for spatiotemporal monitoring of Alzheimer’s-related OE organoids [133] (Figure 3c). These technologies provide powerful new tools for OD research and the diagnosis and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Despite significant advances, olfactory organoids still face challenges such as limited maturation, poor vascularization, and lack of standardization. Functional integration with neural circuits and stable electrical interfacing remains unresolved. Future work should enhance physiological relevance and reproducibility to advance translational and clinical applications.

Figure 3.

OE organoid culture and bionic sensing chips. (a) A schematic of OE organoid culture. (b) A schematic diagram of the olfactory organoids fixed on the MEA chip and subjected to odor stimulation. (c) The OE structure and model establishment of biomimetic OE organoid biosensing chips [133].

5.3. Transplantation

Earlier studies established the ectopic survival and neurogenic potential of OM tissue [134]. One study demonstrated that neonatal rat OM transplanted into the fourth ventricle or parietal cortex of neonatal and adult rats differentiated into OSNs and extended axons into the host brain, but did not reconstruct a typical OB structure [135]. Subsequent work by Holbrook [136] confirmed this by transplanting neonatal mouse OM into the parietal cortex of adult mice, with successful graft survival observed in 85% of recipients. Notably, transplantation of GFP-labeled OE strips from transgenic mice into wild-type OBs resulted in long-term graft survival (83% at 30 days), preservation of native histological features, and sustained GFP expression [137]. Kwon [138] transplanted bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) onto the OM of chemically injured mice and observed significant morphological restoration of the OM. Kurtenbach [139] demonstrated that transplanted c-KIT+ GBCs, which possess neuroregenerative potential, can differentiate into mature ciliated OSNs and promote functional recovery. Similarly, Seo [140] reported that MSCs alleviate age-related OD through Gal1-mediated anti-inflammatory effects. Nasal transplantation of neural stem cells (NSCs) promoted functional recovery and GFP+ cell integration [141].

Submucosal implantation of OM has also shown clinical potential in patients with empty nose syndrome, a condition often accompanied by OD. However, the optimal implantation site remains unclear. Lee [142] compared lateral nasal wall and inferior turbinate implantations, finding superior clinical outcomes with the former, suggesting it may be the preferred anatomical site for OM-based implants in otolaryngological patients. Furthermore, Chang [143] demonstrated that submucosal implantation (specifically, lateral wall implantation) significantly improved olfactory function in ENS patients, particularly in younger individuals.

6. Olfactory Bionic Sensing Technology

According to the overview of conventional approaches for olfactory improvement and reconstruction, the integration of advanced bionic sensing technology has opened new avenues for developing biomimetic bionic noses. The primary function of an electronic nose—also referred to as a bionic nose—is the recognition, quantification, and monitoring of volatile organic compounds (VOCs). While electronic and bionic noses share the same underlying principle of converting chemical signals into measurable outputs, the term “electronic nose” generally refers to devices that translate chemical information into electrical signals [144]. In contrast, the concept of a “bionic nose” is broader, encompassing not only electrical but also optical, mass-based, and other signal transduction mechanisms [145]. Commonly used bionic noses for VOC analysis include nanostructured metal oxide gas sensors [146], electrochemical gas sensors [147], optical sensors [148,149], and mass transducers [150].

Gas sensing and recognition are vital for societal sustainability. However, most current electronic noses (e-noses) are limited to detecting specific gases and struggle with the recognition of complex mixtures. In response, novel e-noses have emerged, including an intelligent olfactory biomimetic sensing system for complex environments [151], a bionic olfactory neuron with in-sensor reservoir computing [152], and a star-nose-like tactile-olfactory sensing array for non-visual environments [153].

Furthermore, advances in biomanufacturing have enabled the in vitro recapitulation of human sensory organs, including the nose, with substantial functionality. For instance, Jodat et al. [154] developed a hybrid device comprising a dual-bioink-printed nasal construct integrated with a biosensing system. This system demonstrated the ability to sense TNT and can be further functionalized to detect various natural odors, chemicals, and disease biomarkers. This work lays the groundwork for 3D-printed, viable cartilage-like tissues with integrated electronic olfactory systems, potentially serving as a functional nose organ for humanoid robots.

OD has seriously affected quality of life, and the COVID-19 pandemic has made this problem increasingly prominent. The loss of smell is more detrimental than commonly perceived, as it impairs flavor perception—affecting eating behavior—and increases risks related to undetected gas leaks, fires, and spoiled food. In some cases, it can also lead to depression [155].

Inspired by cochlear implants [156], researchers are developing an “electronic nose” for olfactory restoration—an electronic olfactory implant. The core of this technology involves bypassing damaged olfactory pathways to directly stimulate the brain’s olfactory processing regions electrically. As previously indicated, electrical stimulation of olfactory areas such as the OB [87,88,89] can promote olfactory improvement and reconstruction. A typical system consists of an external “e-nose” (chemical sensor) that detects environmental odor molecules and an implanted electrode array that delivers electrical signals to the OB or deeper olfactory cortical regions (e.g., the parietal cortex), thereby artificially inducing smell perception.

While safety concerns (e.g., surgical risks) and the challenge of encoding complex odors present significant hurdles, ongoing progress in sensors and neuroscience suggests that functional prototypes may be feasible within years. Although not a perfect substitute for natural smell, this technology holds the promise of restoring a functional sense of smell for severely impaired patients, substantially enhancing their daily living and safety.

7. Olfactory BCI-Based Approaches

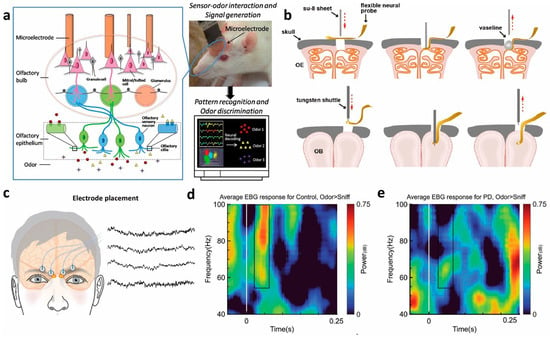

Advances in brain–computer interface (BCI) technology have enabled direct communication between the biological brain and external devices. Our team [157] utilized implanted microelectrode arrays to record and decode neural activity in the OB of rats, achieving 92.67% classification accuracy for odorants such as octanol, pentanal, and butyric acid (Figure 4a). Subsequent work [158] demonstrated that odor-specific firing patterns from mitral/tufted cells, recorded via multichannel arrays in behaving rats, can distinguish various natural fruit odors. Duan [131] simultaneously recorded OE and OB signals using flexible neural electrodes, revealing that spontaneous slow oscillations (<12 Hz) in both regions are respiration-locked and modulate the amplitude of faster oscillations (>20 Hz) associated with odor perception. Based on these findings, an olfactory BCI system was developed with an identification accuracy of 80% (Figure 4b).

Neurophysiological studies [159,160] have shown that synchronization between prefrontal EEG theta rhythms and the respiratory cycle significantly enhances BCI decoding performance, offering new strategies for OD rehabilitation. Leveraging this, Ninenko [161] developed an olfactory neurofeedback (O-NFB) system integrating EEG rhythms with respiratory patterns. In the non-invasive domain, Cakmak [162] proposed a transcutaneous electrical stimulation method targeting the human OB and OE. Iravani [163] introduced the Electrobulbogram (EBG) technique, which uses only four nasal electrodes to non-invasively monitor OB activity (Figure 4c). This method has been applied in PD studies [164], revealing characteristic abnormalities in gamma, beta, and theta frequency bands, highlighting its potential for early diagnosis (Figure 4d,e).

Figure 4.

(a) The OB’s neural activity is recorded by a microelectrode and then fed into a computer-based pattern recognition algorithm for identification of the input odors [158]. (b) Schematic of flexible electrode implanted into OE and OB [131]. (c) Electrode placement for the electrobulbogram (EBG) on the forehead and exemplary recordings [163]. (d,e) Sensor time–frequency decomposition of difference in power for Odor vs. Sniff condition for healthy controls and PD patient [164].

8. Conclusions

This review systematically examines the evolving landscape of olfactory restoration strategies, from olfactory training-induced plasticity to regenerative approaches using stem cells and organoids, and functional replacement via biosensing and BCI technologies. While each modality shows distinct advantages, the most promising direction lies in integrating biosensing with BCI to create closed-loop neuromodulation systems for comprehensive olfactory rehabilitation.

A fundamental challenge remains the establishment of bidirectional communication between artificial sensors and biological neural circuits. Current bionic noses achieve remarkable specificity in odor recognition, yet translating these chemical signatures into biologically meaningful neural codes remains elusive. Evidence from electrical stimulation studies [87,88,89,90] confirms that artificial activation of olfactory pathways can evoke perceptual responses, but the generated sensations lack the qualitative richness of natural smell. This encoding problem constitutes the central bottleneck in current systems.

Simultaneously, neural interface technology faces its own implementation constraints. While both invasive [131,157] and non-invasive [163] approaches show diagnostic potential, neither provides the ideal combination of spatial resolution, long-term stability, and minimal tissue disruption required for chronic implantation. The variability in individual neural anatomy and pathological presentation further complicates universal solution development.

Critical to advancing these technologies is the development of objective assessment methods. The limitations of current olfactory evaluations are particularly apparent when compared to emerging techniques like EBG [163]. While conventional smell identification tests (USA [165], Germany [166], and its extended version [167], Sweden [168], Japan [169], China [170] et al.) rely on subjective patient responses and are inherently influenced by semantic and cultural factors, EBG represents a paradigm shift toward physiological measurement of olfactory bulb activity [163]. This fundamental distinction highlights the need for integrated frameworks that combine physiological recordings with perceptual measures. Such objective biomarkers are essential not only for precise diagnosis but also for reliable quantification of therapeutic outcomes. Future progress depends on establishing standardized evaluation protocols that leverage both approaches to enable accurate, reproducible assessment across diverse clinical and research settings.

Looking forward, we identify three critical pathways for future research. First, machine learning approaches must bridge the sensing–neural divide by developing adaptive algorithms that map chemical features to optimal stimulation parameters. Second, materials science needs to advance toward next-generation interfaces that maintain signal fidelity while minimizing foreign body response. Finally, standardized evaluation frameworks integrating both physiological and perceptual measures are essential to accelerate clinical translation.

The ultimate goal remains developing integrated systems that not only detect environmental chemicals but also convey their perceptual significance through precisely targeted neural stimulation. While substantial challenges persist in neural encoding, interface design, and assessment standardization, the coordinated advancement of biosensing and BCI technologies provides a clear trajectory toward meaningful olfactory restoration for patients with severe smell dysfunction, potentially benefiting broader sensory rehabilitation applications.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (No. 2021ZD0200405), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62271443, 32250008, 82330064), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (226-2024-00059).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Firestein, S. How the olfactory system makes sense of scents. Nature 2001, 413, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de March, C.A.; Matsunami, H.; Abe, M.; Cobb, M.; Hoover, K.C. Genetic and functional odorant receptor variation in the Homo lineage. iScience 2023, 26, 105908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bratman, G.N.; Bembibre, C.; Daily, G.C.; Doty, R.L.; Hummel, T.; Jacobs, L.F.; Kahn, P.H., Jr.; Lashus, C.; Majid, A.; Miller, J.D.; et al. Nature and human well-being: The olfactory pathway. Sci. Adv. 2024, 10, eadn3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dikeçligil, G.N.; Gottfried, J.A. What Does the Human Olfactory System Do, and How Does It Do It? Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2024, 75, 155–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, K.; Nagao, H.; Yoshihara, Y. The olfactory bulb: Coding and processing of odor molecule information. Science 1999, 286, 711–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, L.B. Information coding in the vertebrate olfactory system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1996, 19, 517–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seubert, J.; Laukka, E.J.; Rizzuto, D.; Hummel, T.; Fratiglioni, L.; Bäckman, L.; Larsson, M. Prevalence and Correlates of Olfactory Dysfunction in Old Age: A Population-Based Study. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2017, 72, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Igarashi, K.M. Circuit dynamics of the olfactory pathway during olfactory learning. Front. Neural Circuits 2024, 18, 1437575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagayama, S.; Homma, R.; Imamura, F. Neuronal organization of olfactory bulb circuits. Front. Neural Circuits 2014, 8, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igarashi, K.M.; Ieki, N.; An, M.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Nagayama, S.; Kobayakawa, K.; Kobayakawa, R.; Tanifuji, M.; Sakano, H.; Chen, W.R.; et al. Parallel mitral and tufted cell pathways route distinct odor information to different targets in the olfactory cortex. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 7970–7985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokni, D.; Ben-Shaul, Y. Object-oriented olfaction: Challenges for chemosensation and for chemosensory research. Trends Neurosci. 2024, 47, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, X.; Baserdem, B.; Zhan, H.; Li, Y.; Davis, M.B.; Kebschull, J.M.; Zador, A.M.; Koulakov, A.A.; Albeanu, D.F. High-throughput sequencing of single neuron projections reveals spatial organization in the olfactory cortex. Cell 2022, 185, 4117–4134.e4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avaro, V.; Hummel, T.; Calegari, F. Scent of stem cells: How can neurogenesis make us smell better? Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 964395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, G.; Patel, J.M.; Tepe, B.; McClard, C.K.; Swanson, J.; Quast, K.B.; Arenkiel, B.R. An Objective and Reproducible Test of Olfactory Learning and Discrimination in Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 133, 57142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jobin, B.; Roy-Côté, F.; Frasnelli, J.; Boller, B. Olfaction and declarative memory in aging: A meta-analysis. Chem. Senses 2023, 48, bjad045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Liberles, S.D. Aversion and attraction through olfaction. Curr. Biol. 2015, 25, R120–R129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, K.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, W. Humans navigate with stereo olfaction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 16065–16071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushdid, C.; Magnasco, M.O.; Vosshall, L.B.; Keller, A. Humans can discriminate more than 1 trillion olfactory stimuli. Science 2014, 343, 1370–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, T.; Ikeda, K.; Ishibashi, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Kondo, K.; Matsuwaki, Y.; Ogawa, T.; Shiga, H.; Suzuki, M.; Tsuzuki, K.; et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of olfactory dysfunction—Secondary publication. Auris Nasus Larynx 2019, 46, 653–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desiato, V.M.; Levy, D.A.; Byun, Y.J.; Nguyen, S.A.; Soler, Z.M.; Schlosser, R.J. The Prevalence of Olfactory Dysfunction in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2021, 35, 195–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attems, J.; Walker, L.; Jellinger, K.A. Olfaction and Aging: A Mini-Review. Gerontology 2015, 61, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dintica, C.S.; Marseglia, A.; Rizzuto, D.; Wang, R.; Seubert, J.; Arfanakis, K.; Bennett, D.A.; Xu, W. Impaired olfaction is associated with cognitive decline and neurodegeneration in the brain. Neurology 2019, 92, e700–e709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, R.L. Olfactory dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases: Is there a common pathological substrate? Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 478–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatuzzo, I.; Niccolini, G.F.; Zoccali, F.; Cavalcanti, L.; Bellizzi, M.G.; Riccardi, G.; de Vincentiis, M.; Fiore, M.; Petrella, C.; Minni, A.; et al. Neurons, Nose, and Neurodegenerative Diseases: Olfactory Function and Cognitive Impairment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, A.; Malaspina, D. Hidden consequences of olfactory dysfunction: A patient report series. BMC Ear Nose Throat Disord. 2013, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boesveldt, S.; Postma, E.M.; Boak, D.; Welge-Luessen, A.; Schöpf, V.; Mainland, J.D.; Martens, J.; Ngai, J.; Duffy, V.B. Anosmia—A Clinical Review. Chem. Senses 2017, 42, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abolmaali, N.D.; Hietschold, V.; Vogl, T.J.; Hüttenbrink, K.B.; Hummel, T. MR evaluation in patients with isolated anosmia since birth or early childhood. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2002, 23, 157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Damm, M.; Eckel, H.E.; Jungehülsing, M.; Hummel, T. Olfactory changes at threshold and suprathreshold levels following septoplasty with partial inferior turbinectomy. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2003, 112, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.M.; Deng, X.; Tan, E.K. Olfactory dysfunction and COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamali, K.; Elliott, M.; Hopkins, C. COVID-19 related olfactory dysfunction. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 30, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishijima, H.; Kondo, K.; Yamamoto, T.; Nomura, T.; Kikuta, S.; Shimizu, Y.; Mizushima, Y.; Yamasoba, T. Influence of the location of nasal polyps on olfactory airflow and olfaction. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paksoy, Z.B.; Cayonu, M.; Yucel, C.; Turhan, T. The treatment efficacy of nasal polyposis on olfactory functions, clinical scoring systems and inflammation markers. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 276, 3367–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y. Olfactory Dysfunction in Allergic Rhinitis. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2024, 68, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornazieri, M.A.; Garcia, E.C.D.; Montero, R.H.; Borges, R.; Bezerra, T.F.P.; Pinna, F.R.; Doty, R.L.; Voegels, R.L. Prevalence and Magnitude of Olfactory Dysfunction in Allergic Rhinitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2024, 38, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutlug, S.; Gunbey, E.; Sogut, A.; Celiksoy, M.H.; Kardas, S.; Yildirim, U.; Karli, R.; Murat, N.; Sancak, R. Evaluation of olfactory function in children with allergic rhinitis and nonallergic rhinitis. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 86, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bachert, C.; Marple, B.; Schlosser, R.J.; Hopkins, C.; Schleimer, R.P.; Lambrecht, B.N.; Bröker, B.M.; Laidlaw, T.; Song, W.J. Adult chronic rhinosinusitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, O.G.; Rowan, N.R. Olfactory Dysfunction and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. N. Am. 2020, 40, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombaux, P.; Huart, C.; Levie, P.; Cingi, C.; Hummel, T. Olfaction in Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Curr. Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvack, J.R.; Mace, J.C.; Smith, T.L. Olfactory function and disease severity in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2009, 23, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz-Oleszkiewicz, B.; Hummel, T. Olfactory function in diabetes mellitus. J. Clin. Transl. Endocrinol. 2024, 36, 100342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Kong, W.; Liang, J.; Lu, J.; Chen, D.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qing, Z.; Feng, X.; Sun, L.; et al. Impaired olfactory neural circuit in patients with SLE at early stages. Lupus 2021, 30, 1078–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombini, M.F.; Peres, F.A.; Lapa, A.T.; Sinicato, N.A.; Quental, B.R.; Pincelli Á, S.M.; Amaral, T.N.; Gomes, C.C.; Del Rio, A.P.; Marques-Neto, J.F.; et al. Olfactory function in systemic lupus erythematosus and systemic sclerosis. A longitudinal study and review of the literature. Autoimmun. Rev. 2018, 17, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mete, A.; Bayar Muluk, N.; Şahan, M.H.; Karaoğlan, I. Evaluation of peripheral and central olfactory pathways in HIV-infected patients by MRI. Clin. Radiol. 2024, 79, e295–e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirmosayyeb, O.; Ebrahimi, N.; Barzegar, M.; Afshari-Safavi, A.; Bagherieh, S.; Shaygannejad, V. Olfactory dysfunction in patients with multiple sclerosis; A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, R.M. Regeneration and rewiring the olfactory bulb. Chem. Senses 2005, 30 (Suppl. S1), i133–i134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, X.; Wechter, N.; Gray, S.; Mohanty, J.G.; Croteau, D.L.; Bohr, V.A. Olfactory dysfunction in aging and neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res. Rev. 2021, 70, 101416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, R.L. Olfaction in Parkinson’s disease and related disorders. Neurobiol. Dis. 2012, 46, 527–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouzuki, M.; Suzuki, T.; Nagano, M.; Nakamura, S.; Katsumata, Y.; Takamura, A.; Urakami, K. Comparison of olfactory and gustatory disorders in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol. Sci. 2018, 39, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patino, J.; Karagas, N.E.; Chandra, S.; Thakur, N.; Stimming, E.F. Olfactory Dysfunction in Huntington’s Disease. J. Huntingt. Dis. 2021, 10, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuta, S.; Nagayama, S.; Hasegawa-Ishii, S. Structures and functions of the normal and injured human olfactory epithelium. Front. Neural Circuits 2024, 18, 1406218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalová, M.; Gottfriedová, N.; Mrázková, E.; Janout, V.; Janoutová, J. Cognitive impairment, neurodegenerative disorders, and olfactory impairment: A literature review. Otolaryngol. Pol. 2024, 78, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, V.; Paksarian, D.; Cui, L.; Moberg, P.J.; Turetsky, B.I.; Merikangas, K.R. Olfactory processing in bipolar disorder, major depression, and anxiety. Bipolar Disord. 2018, 20, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazour, F.; Richa, S.; Desmidt, T.; Lemaire, M.; Atanasova, B.; El Hage, W. Olfactory and gustatory functions in bipolar disorders: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 80, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassi, A.; Dorado Doncel, R.; Bath, K.G.; Mandairon, N. Relationship between depression and olfactory sensory function: A review. Chem. Senses 2021, 46, bjab044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, T.; Rissom, K.; Reden, J.; Hähner, A.; Weidenbecher, M.; Hüttenbrink, K.B. Effects of olfactory training in patients with olfactory loss. Laryngoscope 2009, 119, 496–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleszkiewicz, A.; Bottesi, L.; Pieniak, M.; Fujita, S.; Krasteva, N.; Nelles, G.; Hummel, T. Olfactory training with Aromastics: Olfactory and cognitive effects. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 279, 225–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moura, G.O.C.; da Silva, A.L.S.; de Santana, F.R.T.; Walker, C.I.B. Classical Olfactory Training for Smell Restoration: A Systematic Review. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2025, 15, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, F.; Septans, A.L.; Periers, L.; Maillard, J.M.; Legoff, F.; Gurden, H.; Moriniere, S. Olfactory Training and Visual Stimulation Assisted by a Web Application for Patients with Persistent Olfactory Dysfunction After SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Observational Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e29583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Kim, B.G.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, S.W. The neuroplastic effect of olfactory training to the recovery of olfactory system in mouse model. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damm, M.; Pikart, L.K.; Reimann, H.; Burkert, S.; Göktas, Ö.; Haxel, B.; Frey, S.; Charalampakis, I.; Beule, A.; Renner, B.; et al. Olfactory training is helpful in postinfectious olfactory loss: A randomized, controlled, multicenter study. Laryngoscope 2014, 124, 826–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorokowska, A.; Drechsler, E.; Karwowski, M.; Hummel, T. Effects of olfactory training: A meta-analysis. Rhinol. J. 2017, 55, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treder-Rochna, N.; Mańkowska, A.; Kujawa, W.; Harciarek, M. The effectiveness of olfactory training for chronic olfactory disorder following COVID-19: A systematic review. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1457527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.H.; Kim, S.W.; Basurrah, M.A.; Kim, D.H. The Efficacy of Olfactory Training as a Treatment for Olfactory Disorders Caused by Coronavirus Disease-2019: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2023, 37, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, P.; Dixit, A. Olfactory training for olfactory dysfunction in COVID-19: A promising mitigation amidst looming neurocognitive sequelae of the pandemic. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2022, 49, 462–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, T.; Wei, Y.; Wu, D. Effects of olfactory training on posttraumatic olfactory dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 1102–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.J.; Li, K.Y. Comparing the effects of olfactory-based sensory stimulation and board game training on cognition, emotion, and blood biomarkers among individuals with dementia: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1003325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birte-Antina, W.; Ilona, C.; Antje, H.; Thomas, H. Olfactory training with older people. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2018, 33, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambom-Ferraresi, F.; Zambom-Ferraresi, F.; Fernández-Irigoyen, J.; Lachén-Montes, M.; Cartas-Cejudo, P.; Lasarte, J.J.; Casares, N.; Fernández, S.; Cedeño-Veloz, B.A.; Maraví-Aznar, E.; et al. Olfactory Characterization and Training in Older Adults: Protocol Study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2021, 13, 757081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughnane, M.; Tischler, V.; Khalid Saifeldeen, R.; Kontaris, E. Aging and Olfactory Training: A Scoping Review. Innov. Aging 2024, 8, igae044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kattar, N.; Do, T.M.; Unis, G.D.; Migneron, M.R.; Thomas, A.J.; McCoul, E.D. Olfactory Training for Postviral Olfactory Dysfunction: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 164, 244–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, D.E.; Del Bene, V.A.; Kamath, V.; Frank, J.S.; Billings, R.; Cho, D.Y.; Byun, J.Y.; Jacob, A.; Anderson, J.N.; Visscher, K.; et al. Does Olfactory Training Improve Brain Function and Cognition? A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol. Rev. 2024, 34, 155–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, T.; Stupka, G.; Haehner, A.; Poletti, S.C. Olfactory training changes electrophysiological responses at the level of the olfactory epithelium. Rhinol. J. 2018, 56, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bérubé, S.; Demers, C.; Bussière, N.; Cloutier, F.; Pek, V.; Chen, A.; Bolduc-Bégin, J.; Frasnelli, J. Olfactory Training Impacts Olfactory Dysfunction Induced by COVID-19: A Pilot Study. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2023, 85, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Bon, S.D.; Konopnicki, D.; Pisarski, N.; Prunier, L.; Lechien, J.R.; Horoi, M. Efficacy and safety of oral corticosteroids and olfactory training in the management of COVID-19-related loss of smell. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2021, 278, 3113–3117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, T.L.I.; Antonio, M.A.; Giacomin, L.T.; Morcillo, A.M.; Dirceu Ribeiro, J.; Sakano, E. Olfactory training for the treatment of COVID-19 related smell loss: A randomised double-blind controlled trial. Rhinology 2025, 63, 325–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, A.; Naderi, M.; Jonaidi Jafari, N.; Emadi Koochak, H.; Saberi Esfeedvajani, M.; Abolghasemi, R. Therapeutic effects of olfactory training and systemic vitamin A in patients with COVID-19-related olfactory dysfunction: A double-blinded randomized controlled clinical trial. Braz. J. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 90, 101451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Aïn, S.; Poupon, D.; Hétu, S.; Mercier, N.; Steffener, J.; Frasnelli, J. Smell training improves olfactory function and alters brain structure. NeuroImage 2019, 189, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Anne, A.; Hummel, T. Olfactory training: Effects of multisensory integration, attention towards odors and physical activity. Chem. Senses 2023, 48, bjad037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heian, I.T.; Thorstensen, W.M.; Myklebust, T.A.; Hummel, T.; Nordgard, S.; Bratt, M.; Helvik, A.S.; Helvik, A.S. Olfactory training in normosmic individuals: A randomised controlled trial. Rhinology 2024, 62, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaeyan, A.; Asadi, S.; Kamrava, S.K.; Zare-Sadeghi, A. Olfactory training affects the correlation between brain structure and functional connectivity. Neuroradiol. J. 2025, 38, 450–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ottoson, D. Olfactory bulb potentials induced by electrical stimulation of the nasal mucosa in the frog. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1959, 47, 160–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, S.; Lu, T.; Chen, M.; Mao, J.; Hu, X.; Li, S. Forward Electric Stimulation-Induced Interference in Intracochlear Electrocochleography of Acoustic Stimulation in the Cochlea of Guinea Pigs. Front. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 853275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canfarotta, M.W.; Dillon, M.T.; Buss, E.; Pillsbury, H.C.; Brown, K.D.; O’Connell, B.P. Frequency-to-Place Mismatch: Characterizing Variability and the Influence on Speech Perception Outcomes in Cochlear Implant Recipients. Ear Hear. 2020, 41, 1349–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straschill, M.; Stahl, H.; Gorkisch, K. Effects of electrical stimulation of the human olfactory mucosa. Appl. Neurophysiol. 1983, 46, 286–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishimaru, T.; Shimada, T.; Sakumoto, M.; Miwa, T.; Kimura, Y.; Furukawa, M. Olfactory evoked potential produced by electrical stimulation of the human olfactory mucosa. Chem. Senses 1997, 22, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Weiss, T.; Shushan, S.; Ravia, A.; Hahamy, A.; Secundo, L.; Weissbrod, A.; Ben-Yakov, A.; Holtzman, Y.; Cohen-Atsmoni, S.; Roth, Y.; et al. From Nose to Brain: Un-Sensed Electrical Currents Applied in the Nose Alter Activity in Deep Brain Structures. Cereb. Cortex 2016, 26, 4180–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Dong, Q.; Du, L.; Zhuang, L.; Li, R.; Liu, Q.; Wang, P. A novel bioelectronic nose based on brain-machine interface using implanted electrode recording in vivo in olfactory bulb. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013, 49, 263–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coelho, D.H.; Costanzo, R.M. Spatial Mapping in the Rat Olfactory Bulb by Odor and Direct Electrical Stimulation. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2016, 155, 526–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, D.H.; Socolovsky, L.D.; Costanzo, R.M. Activation of the rat olfactory bulb by direct ventral stimulation after nerve transection. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018, 8, 922–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holbrook, E.H.; Puram, S.V.; See, R.B.; Tripp, A.G.; Nair, D.G. Induction of smell through transethmoid electrical stimulation of the olfactory bulb. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, E. A Bionic Nose to Smell the Roses Again: Covid Survivors Drive Demand for a Neuroprosthetic Nose. IEEE Spectr. 2022, 59, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menzel, S.; Konstantinidis, I.; Valentini, M.; Battaglia, P.; Turri-Zanoni, M.; Sileo, G.; Monti, G.; Castelnuovo, P.G.M.; Hummel, T.; Macchi, A. Surgical Approaches for Possible Positions of an Olfactory Implant to Stimulate the Olfactory Bulb. ORL J. Otorhinolaryngol. Relat. Spec. 2023, 85, 253–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, G.; Juhász, C.; Sood, S.; Asano, E. Olfactory hallucinations elicited by electrical stimulation via subdural electrodes: Effects of direct stimulation of olfactory bulb and tract. Epilepsy Behav. 2012, 24, 264–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bérard, N.; Landis, B.N.; Legrand, L.; Tyrand, R.; Grouiller, F.; Vulliémoz, S.; Momjian, S.; Boëx, C. Electrical stimulation of the medial orbitofrontal cortex in humans elicits pleasant olfactory perceptions. Epilepsy Behav. 2021, 114, 107559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzola, L.; Royet, J.P.; Catenoix, H.; Montavont, A.; Isnard, J.; Mauguière, F. Gustatory and olfactory responses to stimulation of the human insula. Ann. Neurol. 2017, 82, 360–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senf, K.; Karius, J.; Stumm, R.; Neuhaus, E.M. Chemokine signaling is required for homeostatic and injury-induced neurogenesis in the olfactory epithelium. Stem Cells 2021, 39, 617–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClintock, T.S.; Khan, N.; Xie, C.; Martens, J.R. Maturation of the Olfactory Sensory Neuron and Its Cilia. Chem. Senses 2020, 45, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, H.; Schwob, J.E. Multipotency of purified, transplanted globose basal cells in olfactory epithelium. J. Comp. Neurol. 2004, 469, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwob, J.E.; Jang, W.; Holbrook, E.H.; Lin, B.; Herrick, D.B.; Peterson, J.N.; Hewitt Coleman, J. Stem and progenitor cells of the mammalian olfactory epithelium: Taking poietic license. J. Comp. Neurol. 2017, 525, 1034–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldstein, B.J.; Goss, G.M.; Choi, R.; Saur, D.; Seidler, B.; Hare, J.M.; Chaudhari, N. Contribution of Polycomb group proteins to olfactory basal stem cell self-renewal in a novel c-KIT+ culture model and in vivo. Development 2016, 143, 4394–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, R.B.; Das, D.; Gadye, L.; Street, K.N.; Baudhuin, A.; Wagner, A.; Cole, M.B.; Flores, Q.; Choi, Y.G.; Yosef, N.; et al. Deconstructing Olfactory Stem Cell Trajectories at Single-Cell Resolution. Cell Stem Cell 2017, 20, 817–830.e818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, J.; Lin, B.; Barrios-Camacho, C.M.; Herrick, D.B.; Holbrook, E.H.; Jang, W.; Coleman, J.H.; Schwob, J.E. Activating a Reserve Neural Stem Cell Population In Vitro Enables Engraftment and Multipotency after Transplantation. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 12, 680–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Reed, R.R.; Lane, A.P. Chronic Inflammation Directs an Olfactory Stem Cell Functional Switch from Neuroregeneration to Immune Defense. Cell Stem Cell 2019, 25, 501–513.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.; Tian, S.; Yang, X.; Lane, A.P.; Reed, R.R.; Liu, H. Wnt-responsive Lgr5⁺ globose basal cells function as multipotent olfactory epithelium progenitor cells. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 8268–8276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Tong, M.; Wang, L.; Qin, Y.; Yu, H.; Yu, Y. Age-Dependent Activation and Neuronal Differentiation of Lgr5+ Basal Cells in Injured Olfactory Epithelium via Notch Signaling Pathway. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2020, 12, 602688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Duan, C.; Ren, W.; Li, F.; Zheng, Q.; Wang, L.; Li, W.; Lu, X.; Ni, W.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Notch Signaling Regulates Lgr5(+) Olfactory Epithelium Progenitor/Stem Cell Turnover and Mediates Recovery of Lesioned Olfactory Epithelium in Mouse Model. Stem Cells 2018, 36, 1259–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, M.A.; Kurtenbach, S.; Sargi, Z.B.; Harbour, J.W.; Choi, R.; Kurtenbach, S.; Goss, G.M.; Matsunami, H.; Goldstein, B.J. Single-cell analysis of olfactory neurogenesis and differentiation in adult humans. Nat. Neurosci. 2020, 23, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, K.M.; Herrick, D.B.; Schwob, J.E.; Holbrook, E.H.; Jang, W. The Neuroregenerative Capacity of Olfactory Stem Cells Is Not Limitless: Implications for Aging. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 6806–6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ressler, K.J.; Sullivan, S.L.; Buck, L.B. Information coding in the olfactory system: Evidence for a stereotyped and highly organized epitope map in the olfactory bulb. Cell 1994, 79, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.R.; Wu, Y. Regeneration and rewiring of rodent olfactory sensory neurons. Exp. Neurol. 2017, 287, 395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheusi, G.; Cremer, H.; McLean, H.; Chazal, G.; Vincent, J.D.; Lledo, P.M. Importance of newly generated neurons in the adult olfactory bulb for odor discrimination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 1823–1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondo, K.; Suzukawa, K.; Sakamoto, T.; Watanabe, K.; Kanaya, K.; Ushio, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nibu, K.; Kaga, K.; Yamasoba, T. Age-related changes in cell dynamics of the postnatal mouse olfactory neuroepithelium: Cell proliferation, neuronal differentiation, and cell death. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 518, 1962–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Linden, C.J.; Gupta, P.; Bhuiya, A.I.; Riddick, K.R.; Hossain, K.; Santoro, S.W. Olfactory Stimulation Regulates the Birth of Neurons That Express Specific Odorant Receptors. Cell Rep. 2020, 33, 108210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, J.H.; Lin, B.; Louie, J.D.; Peterson, J.; Lane, R.P.; Schwob, J.E. Spatial Determination of Neuronal Diversification in the Olfactory Epithelium. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 814–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.Q.; Zhuang, L.J.; Bao, H.Q.; Li, S.J.; Dai, F.Y.; Wang, P.; Li, Q.; Yin, D.M. Olfactory regulation by dopamine and DRD2 receptor in the nose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2118570119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doty, R.L. The olfactory vector hypothesis of neurodegenerative disease: Is it viable? Ann. Neurol. 2008, 63, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, F.; Hasegawa-Ishii, S. Environmental Toxicants-Induced Immune Responses in the Olfactory Mucosa. Front. Immunol. 2016, 7, 475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuta, S.; Sakamoto, T.; Nagayama, S.; Kanaya, K.; Kinoshita, M.; Kondo, K.; Tsunoda, K.; Mori, K.; Yamasoba, T. Sensory deprivation disrupts homeostatic regeneration of newly generated olfactory sensory neurons after injury in adult mice. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 2657–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, D.; Wang, B.; Oliver, J.; Pyburn, J.; Rodriguez-Gil, D.J.; Hagg, T.; Jia, C. Stem cell CNTF promotes olfactory epithelial neuroregeneration and functional recovery following injury. Stem Cells 2025, 43, sxaf033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sipione, R.; Liaudet, N.; Rousset, F.; Landis, B.N.; Hsieh, J.W.; Senn, P. Axonal Regrowth of Olfactory Sensory Neurons In Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 12863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzschmar, K.; Clevers, H. Organoids: Modeling Development and the Stem Cell Niche in a Dish. Dev. Cell 2016, 38, 590–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauth, S.; Karmakar, S.; Batra, S.K.; Ponnusamy, M.P. Recent advances in organoid development and applications in disease modeling. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Rev. Cancer 2021, 1875, 188527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krolewski, R.C.; Jang, W.; Schwob, J.E. The generation of olfactory epithelial neurospheres in vitro predicts engraftment capacity following transplantation in vivo. Exp. Neurol. 2011, 229, 308–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Feng, X.; Zhuang, L.; Jiang, N.; Xu, R.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Sun, X.; et al. Expansion of murine and human olfactory epithelium/mucosa colonies and generation of mature olfactory sensory neurons under chemically defined conditions. Theranostics 2021, 11, 684–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ren, W.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Tian, H.; Bhattarai, J.P.; Challis, R.C.; Lee, A.C.; Zhao, S.; Yu, H.; et al. Chitinase-Like Protein Ym2 (Chil4) Regulates Regeneration of the Olfactory Epithelium via Interaction with Inflammation. J. Neurosci. 2021, 41, 5620–5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Wu, T.; Zhu, K.; Ba, G.; Liu, J.; Zhou, P.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Liu, H.; Ren, W.; et al. A single-cell transcriptomic census of mammalian olfactory epithelium aging. Dev. Cell 2024, 59, 3043–3058.e3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.H.; Luo, X.C.; Yu, C.R.; Huang, L. Matrix metalloprotease-mediated cleavage of neural glial-related cell adhesion molecules activates quiescent olfactory stem cells via EGFR. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2020, 108, 103552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Deng, L.; Qin, X. Development of an olfactory epithelial organoid culture system based on small molecule screening. Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao 2023, 39, 318–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.H.; Park, Y.-G.; Kim, S.; Park, J.-U. 3D Electrodes for Bioelectronics. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2005805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Qin, C.; Yuan, Q.; Duan, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhuang, L.; Wang, P.; IEEE. A bioinspired olfactory sensor based on organoid-on-a-chip. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Olfaction and Electronic Nose (ISOEN 2022), Aveiro, Portugal, 29 May–1 June 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Wang, S.; Yuan, Q.; Shi, Y.; Jiang, N.; Jiang, D.; Song, J.; Wang, P.; Zhuang, L. Long-Term Flexible Neural Interface for Synchronous Recording of Cross-Regional Sensory Processing along the Olfactory Pathway. Small 2023, 19, 2205768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, N.; Liu, M.X.; Yuan, Q.C.; Zhuang, L.J.; Wang, P.; IEEE. Biomimetic olfactory sensor based on uniform OE organoids. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Olfaction and Electronic Nose (ISOEN), Grapevine, TX, USA, 12–15 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Jiang, N.; Qin, C.; Xue, Y.; Wu, J.; Qiu, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Chen, C.; Huang, L.; Zhuang, L.; et al. Multimodal spatiotemporal monitoring of basal stem cell-derived organoids reveals progression of olfactory dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 246, 115832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanzo, R.M.; Yagi, S. Olfactory epithelial transplantation: Possible mechanism for restoration of smell. Curr. Opin. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2011, 19, 54–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Morrison, E.E.; Graziadei, P.P. Transplants of olfactory mucosa in the rat brain I. A light microscopic study of transplant organization. Brain Res. 1983, 279, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holbrook, E.H.; DiNardo, L.J.; Costanzo, R.M. Olfactory epithelium grafts in the cerebral cortex: An immunohistochemical analysis. Laryngoscope 2001, 111, 1964–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Yagi, S.; Costanzo, R.M. Grafting the olfactory epithelium to the olfactory bulb. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2009, 23, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.W.; Jo, H.G.; Park, S.M.; Ku, C.H.; Park, D.J. Engraftment and regenerative effects of bone marrow stromal cell transplantation on damaged rat olfactory mucosa. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2016, 273, 2585–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtenbach, S.; Goss, G.M.; Goncalves, S.; Choi, R.; Hare, J.M.; Chaudhari, N.; Goldstein, B.J. Cell-Based Therapy Restores Olfactory Function in an Inducible Model of Hyposmia. Stem Cell Rep. 2019, 12, 1354–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.; Ahn, J.S.; Shin, Y.Y.; Oh, S.J.; Song, M.H.; Kang, M.J.; Oh, J.M.; Lee, D.; Kim, Y.H.; Lee, B.C.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells target microglia via galectin-1 production to rescue aged mice from olfactory dysfunction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 153, 113347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazir, B.; Ceylan, A.; Bagariack, E.; Dayanir, D.; Araz, M.; Ceylan, B.T.; Oruklu, N.; Sahin, M.M. Effects of intranasal neural stem cells transplantation on olfactory epithelium regeneration in an anosmia-induced mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, T.J.; Fu, C.H.; Wu, C.L.; Lee, Y.C.; Huang, C.C.; Chang, P.H.; Chen, Y.W.; Tseng, H.J. Surgical outcome for empty nose syndrome: Impact of implantation site. Laryngoscope 2018, 128, 554–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, F.-Y.; Fu, C.-H.; Lee, T.-J. Outcomes of olfaction in patients with empty nose syndrome after submucosal implantation. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, C. Electronic nose for volatile organic compounds analysis in rice aging. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 109, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Zogona, D.; Wu, T.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Applications, challenges and prospects of bionic nose in rapid perception of volatile organic compounds of food. Food Chem. 2023, 415, 135650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Yu, S.; Wang, X.; Huang, J.; Pan, W.; Zhang, J.; Meteku, B.E.; Zeng, J. UV illumination-enhanced ultrasensitive ammonia gas sensor based on (001)TiO2/MXene heterostructure for food spoilage detection. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 423, 127160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, P.F.M.; de Sousa Picciani, P.H.; Calado, V.; Tonon, R.V. Electrical gas sensors for meat freshness assessment and quality monitoring: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.W.; Zou, X.B.; Shi, J.Y.; Li, Z.H.; Zhao, J.W. Colorimetric sensor arrays based on chemo-responsive dyes for food odor visualization. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 81, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, R.S.; Sanfelice, R.C.; Pavinatto, A.; Mattoso, L.H.C.; Correa, D.S. Hybrid nanomaterials designed for volatile organic compounds sensors: A review. Mater. Des. 2018, 156, 154–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, C. Volatile organic compounds gas sensor based on quartz crystal microbalance for fruit freshness detection: A review. Food Chem. 2021, 334, 127615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Wang, J.; Yang, H.; Li, Z.; Zhao, F.; Liu, W.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Jiang, H.; Qin, N.; et al. A Drosophila-inspired intelligent olfactory biomimetic sensing system for gas recognition in complex environments. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shi, S.; Jiang, J.; Lin, D.; Song, J.; Wang, Z.; Huang, W. Bionic Olfactory Neuron with In-Sensor Reservoir Computing for Intelligent Gas Recognition. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, e2419159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Qin, N.; Yang, H.; Sun, K.; Hao, J.; Shu, L.; Liu, J.; Chen, Q.; et al. A star-nose-like tactile-olfactory bionic sensing array for robust object recognition in non-visual environments. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jodat, Y.A.; Kiaee, K.; Vela Jarquin, D.; De la Garza Hernández, R.L.; Wang, T.; Joshi, S.; Rezaei, Z.; de Melo, B.A.G.; Ge, D.; Mannoor, M.S.; et al. A 3D-Printed Hybrid Nasal Cartilage with Functional Electronic Olfaction. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1901878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makin, S. Restoring smell with an electronic nose. Nature 2022, 606, S12–S13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boisvert, I.; Reis, M.; Au, A.; Cowan, R.; Dowell, R.C. Cochlear implantation outcomes in adults: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.T.; Zhuang, L.J.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, B.; Hu, N.; Wang, P. Multi-odor discrimination by a novel bio-hybrid sensing preserving rat’s intact smell perception in vivo. Sens. Actuators B-Chem. 2016, 225, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Guo, T.; Cao, D.; Ling, L.; Su, K.; Hu, N.; Wang, P. Detection and classification of natural odors with an in vivo bioelectronic nose. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 67, 694–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninenko, I.; Kleeva, D.F.; Bukreev, N.; Lebedev, M.A. An experimental paradigm for studying EEG correlates of olfactory discrimination. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1117801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morozova, M.; Bikbavova, A.; Bulanov, V.; Lebedev, M.A. An olfactory-based Brain-Computer Interface: Electroencephalography changes during odor perception and discrimination. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1122849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninenko, I.; Medvedeva, A.; Efimova, V.L.; Kleeva, D.F.; Morozova, M.; Lebedev, M.A. Olfactory neurofeedback: Current state and possibilities for further development. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1419552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, Y.O.; Nazim, K.; Thomas, C.; Datta, A. Optimized Electrode Placements for Non-invasive Electrical Stimulation of the Olfactory Bulb and Olfactory Mucosa. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 581503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravani, B.; Arshamian, A.; Ohla, K.; Wilson, D.A.; Lundström, J.N. Non-invasive recording from the human olfactory bulb. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iravani, B.; Arshamian, A.; Schaefer, M.; Svenningsson, P.; Lundström, J.N. A non-invasive olfactory bulb measure dissociates Parkinson’s patients from healthy controls and discloses disease duration. npj Park. Dis. 2021, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doty, R.L.; Shaman, P.; Applebaum, S.L.; Giberson, R.; Siksorski, L.; Rosenberg, L. Smell identification ability: Changes with age. Science 1984, 226, 1441–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummel, T.; Sekinger, B.; Wolf, S.R.; Pauli, E.; Kobal, G. ‘Sniffin’ sticks’: Olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odor identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem. Senses 1997, 22, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehner, A.; Mayer, A.M.; Landis, B.N.; Pournaras, I.; Lill, K.; Gudziol, V.; Hummel, T. High test-retest reliability of the extended version of the “Sniffin’ Sticks” test. Chem. Senses 2009, 34, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, S.; Brämerson, A.; Lidén, E.; Bende, M. The Scandinavian Odor-Identification Test: Development, reliability, validity and normative data. Acta Otolaryngol. 1998, 118, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M. The Odor Stick Identification Test for the Japanese (OSIT-J): Clinical suitability for patients suffering from olfactory disturbance. Chem. Senses 2005, 30 (Suppl. S1), i216–i217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Zhuang, Y.; Yao, F.; Ye, Y.; Wan, Q.; Zhou, W. Development of the Chinese Smell Identification Test. Chem. Senses 2019, 44, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).