Abstract

Statin non-adherence is a common problem in the management of cardiovascular disease (CVD), increasing patient morbidity and mortality. Mobile health (mHealth) interventions may be a scalable way to improve medication adherence. The objectives of this review were to assess the literature testing mHealth interventions for statin adherence and to identify the Behaviour-Change Techniques (BCTs) employed by effective and ineffective interventions. A systematic search was conducted of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) measuring the effectiveness of mHealth interventions to improve statin adherence against standard of care in those who had been prescribed statins for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD, published in English (1 January 2000–17 July 2020). For included studies, relevant data were extracted, the BCTs used in the trial arms were coded, and a quality assessment made using the Risk of Bias 2 (RoB2) questionnaire. The search identified 17 relevant studies. Twelve studies demonstrated a significant improvement in adherence in the mHealth intervention trial arm, and five reported no impact on adherence. Automated phone messages were the mHealth delivery method most frequently used in effective interventions. Studies including more BCTs were more effective. The BCTs most frequently associated with effective interventions were “Goal setting (behaviour)”, “Instruction on how to perform a behaviour”, and “Credible source”. Other effective techniques were “Information about health consequences”, “Feedback on behaviour”, and “Social support (unspecified)”. This review found moderate, positive evidence of the effect of mHealth interventions on statin adherence. There are four primary recommendations for practitioners using mHealth interventions to improve statin adherence: use multifaceted interventions using multiple BCTs, consider automated messages as a digital delivery method from a credible source, provide instructions on taking statins, and set adherence goals with patients. Further research should assess the optimal frequency of intervention delivery and investigate the generalisability of these interventions across settings and demographics.

1. Introduction

The global burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is rising, accounting for approximately 31% of global deaths [1]. Statins are the most commonly prescribed drug for those at risk of developing CVD (primary prevention) or those with CVD (secondary prevention) and are estimated to be taken by 200 million people [2,3,4,5]. Increased adherence to statins correlates with a reduced risk of CVD events, CVD-related mortality, and all-cause mortality [6,7,8]. In addition to the negative health impact of low adherence, non-adherence also results in significant healthcare costs, with one review estimating the annual per-patient cost of non-adherence to CVD medications (due to additional medical costs, unnecessary hospitalisations, and primary care visits) to range from $3347 to $19,472 [9].

A patient is typically described as adherent if they take more than 80% of their prescribed medication doses at the appropriate time over a specified period [10,11]. Statin adherence rates have been found to be 45–50% during the first six months of taking statins [12,13,14,15,16], reducing to 25% after two years [10]. This is comparable to adherence to other long-term medications [5], though there are significant negative media perceptions of statin side effects which may impact adherence to this particular medication [17].

Various factors correlate with medication non-adherence [10,18], including socioeconomic factors (female gender, younger age), disease-related factors (certain comorbidities), patient-related or psychological factors (lack of knowledge, mistrust), therapy-related factors (higher medication dose, side effects), and health system-related factors (cost of therapy, lack of appointments) [18]. As statins manage a so-called silent risk of CVD, patients may be less likely to prioritise taking them due to lack of salient symptoms [19] and therefore not perceive the benefits of taking them [18,20].

Interventions seek to alter patient-related drivers, although it is often difficult to tell which elements have successfully directed behaviour change, as many interventions are multi-faceted and use a variety of different behavioural components or techniques (e.g., using education to improve understanding [21,22] targeting patient beliefs [23], and harnessing trust in medical professionals [24,25]). The Behaviour-Change Techniques (BCT) taxonomy can systematically identify and compare the active ingredients of interventions, which may be described in different ways in different studies [26,27]. This enables effective comparisons to be made across interventions so that recommendations can be made about which specific techniques appear most effective at changing behaviour and should be used in future interventions.

There has been a rise in mobile health (mHealth) technologies, especially interventions delivered by mobile devices, such as phones and smartwatches, to alter adherence-related behaviours [28], as these technologies are scalable and relatively low cost [29]. There is a range of literature summarising the effectiveness of mHealth interventions and medication adherence for CVD [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. However, only one study has focused solely on statin adherence, though this also included interventions other than mHealth interventions [39]. This review by van Driel et al. found mixed evidence supporting the link between the use of various mHealth interventions and improved adherence, though it identified a positive impact from electronic reminders [39]. As that review was conducted in 2016, and there has been an increase in the use of mHealth interventions since then, an update is necessary. Other systematic reviews, whilst demonstrating a positive or mixed impact of mHealth technologies on adherence, only focused on a single aspect of mHealth, e.g., mobile phones [33,37,38], text messaging [30], or the use of applications [32].

This review systematically compiles and assesses the available literature on the effectiveness of mHealth interventions to improve statin adherence. It builds on van Driel’s review [39] and the other reviews of mHealth interventions [30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] by using the BCT taxonomy to identify the elements of interventions that effectively improve adherence and subsequently determine which BCTs are the most effective [26,27]. Two recent reviews assessed the effectiveness of mobile applications to improve medication adherence across a range of conditions using the BCT taxonomy [40,41]. Pfaeffli Dale conducted a systematic review in 2015 looking at the effectiveness of mHealth interventions in CVD medication adherence using the BCT taxonomy [36]. The current review builds on this existing research by including studies published since 2015 and focusing specifically on statin adherence, as it is the most widely prescribed medication for CVD and one that follows a typical dosing and administration form (tablets once daily).

The objectives of this review are to review the effectiveness of mHealth interventions on statin adherence, as evaluated by Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs), and to identify BCTs employed by mHealth interventions to improve statin adherence.

2. Materials and Methods

The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [42] and its accompanying Explanation and Elaboration document [43].

The search included peer-reviewed papers, published in English, from 1 January 2000 to 17 July 2020. With the growth in the technology used within mHealth, this time period allowed the review to assess studies using the most relevant technologies. The eligibility criteria and search strategy was developed using the PICOS (population, interventions, comparator, outcomes, study design) framework [43]. Details of the search strategy are included in Appendix A (Table A1. Search strategy for Medline database in Ovid (search conducted 17 July 2020).

2.1. Participants

Studies including patients of any age who were prescribed statins in any setting for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD were eligible for inclusion. Studies where statins are used for patients with diabetes or stroke only were not included.

2.2. Intervention and Comparator

Studies with interventions employing health practices, primarily targeted at the patient, supported by any type of mobile devices were eligible for inclusion [28]. Interventions could comprise of multiple delivery methods, including both mHealth and non-digital elements. The comparator should be the usual standard of care.

2.3. Outcome

The primary outcome assessed was statin adherence, measured by any metric, over any follow up period and with any follow up completion rate.

2.4. Study Design

The review included RCTs that measured the impact of mHealth interventions on statin adherence against the standard of care. Studies were identified by electronically searching CINAHL, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Additional studies were identified from a search of the grey literature and from the reference list of relevant reviews in this area and included studies.

Two reviewers (Z.B. and T.S.) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the studies for relevance and conflicts were resolved through discussion. Z.B. conducted a full-text review of all screened studies for inclusion, and T.S. screened 10% of these studies. The data extraction comprised study characteristics and results, quality assessment, and categorisation of interventions by BCT coding. Z.B. conducted all three stages and G.J. conducted BCT coding for 20% of the sample. Data was extracted into a customised template.

An assessment of the quality and internal validity of included trials was conducted using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool Version 2 (RoB2) [44]. Blinding of participants and personnel was not included in the final score calculation, as mHealth interventions were unable to be blinded.

Reviewers identified and coded the behaviour change techniques used in the interventions and standard of care using the BCT taxonomy and the accompanying coding manual [27]. Conflicts in coding were resolved through discussion. Where necessary, study authors were contacted by email for further or missing information. If there was still insufficient detail or no response, the reviewers coded at the category level rather than specify individual techniques. As per the BCT training, the coders used a (+) to indicate “BCT present in all probability” or a (++) to indicate “BCT present beyond all reasonable doubt” [45]. Only the techniques directed at patient behaviour were coded. A BCT was recorded once even if it was mentioned multiple times in the intervention process. The extracted data on intervention delivery method, frequency, trial length, and BCT codes were then categorised and analysed based on the reported effectiveness of the trial interventions.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

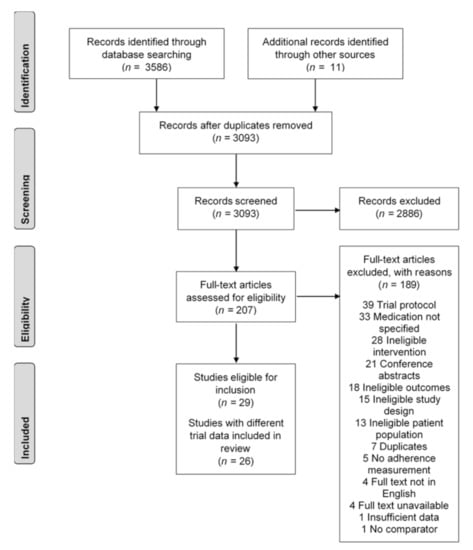

A total of 3597 studies were identified from the systematic literature search, and 504 duplicate records (14.0%) were removed to include 3093 in the initial screening (Figure 1). Two reviewers screened the title and abstract, identified 2886 studies as irrelevant, and discussed 446 records where their initial assessments differed for inclusion in the full-text review. A total of 207 full texts were reviewed for their eligibility.

Figure 1.

Study selection flowchart, based on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

Seventeen trials described in twenty articles were screened as eligible following the full-text review [46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. The three primary reasons for exclusion were studies being trial protocols (20.6%), the medication used in the study not specified (17.4%), and ineligible interventions (14.8%). Two studies from Park (2013, 2015), Reddy (2016, 2017), and Salisbury (2016, 2017) were identified as using the same trial data. The Park 2013 [61], Reddy 2016 [48], and Salisbury 2016 [49] papers were selected, as these were the first papers published with the trial data.

3.2. Study Characteristics

A summary of study characteristics is shown in Table 1. The majority of studies were published after 2012. The studies were mainly conducted in high-income countries in North America and Europe. Most trials were in primary care settings, particularly in local pharmacies; however, one was conducted from hospital settings [50].

Table 1.

Summary characteristics of included studies including author, setting, participant information, trial arms, adherence outcome data, Behaviour-Change Technique (BCT) used in the mobile health (mHealth) interventions, and overall risk of bias score from Risk of Bias 2 questionnaire.

3.2.1. Inclusion Criteria

Patients were primarily recruited from hospital or primary care settings. Descriptions of disease characteristics in the study inclusion criteria included diagnoses of cardiovascular disease, coronary artery or heart disease, acute coronary syndrome, and myocardial infarction. In five studies, these criteria also required participant hospitalisation [53,55,57,58,61]. Five studies required participants to be demonstrably non-adherent to statins prior to the trial [46,48,52,59,60], whilst two required participants to be newly prescribed statins in the year before the study [47,51].

3.2.2. Exclusion Criteria

The most frequently used exclusion criteria was disease characteristics, including those unlikely to survive the follow up [49,57,60], severe mental illness [49,55,62], or other stated severe co-morbidities [48,49,53,55,59]. In eight studies, participants were excluded due to a physical, cognitive, or technological inability to use the intervention, including those with no telephone [48,49,50,55,57,60,61,62]. In three studies, participants were excluded if they were in receipt of care (including residence in a nursing home or not being responsible for their own medication) [56,57,60]. In two studies, participants were excluded due to lack of language proficiency [49,62].

3.3. Effectiveness of Interventions to Improve Statin Adherence

Information on the reported effectiveness of mHealth interventions in all studies are included in Table 1. Twelve of the seventeen included studies (71%) reported a statistically significant improvement on participant adherence to statin medication for those using mHealth interventions compared to usual care, reported in Table 2 [46,47,48,50,51,55,56,57]. Of these twelve studies, three demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in adherence in only some of the participant groups, interventions, or timepoints tested [48,52,59]. The remaining five studies found no impact of mHealth interventions on adherence [53,58,60,61,62]. The trials used a variety of measurements of statin adherence, including mean adherence measured by the average proportion of days participants opened their pill bottles or filled their prescriptions [47,48,54,56,59], Proportion of Days Covered (PDC) [46,51,52,53,57], Morisky Medication Adherence Scale (MMAS) [49,50,55,61], and statin persistence and discontinuation [58,60,62]. Five studies used self-reported adherence measures to assess the outcomes [48,49,58,61,62], whilst the rest used pharmacy dispensation data or electronic devices such as pillboxes. The effect size was calculated in seven studies where the standard deviation (SD) was provided. The effect size ranged from 0.06 to 0.75. The relative improvement in adherence ranged from 2% to 63%, with five studies (29%) demonstrating less than 10% relative improvement, three studies (18%) between 10–25%, and six studies (35%) over 25% relative improvement.

Table 2.

Adherence rates reported in trials reporting statistically significant improvement in adherence, including adherence rate in usual care and intervention trial arms, the standard deviation (SD) of the usual care arm adherence if provided, effect size, and relative improvement in adherence.

3.4. Intervention Characteristics

The description, duration, timing, delivery, and providers involved in the mHealth interventions employed in the included studies are described in (Table 1). The majority of studies used complex interventions that were comprised of multiple delivery components (16 studies, 11 effective studies, 69%). The mean and median number of delivery methods used was three.

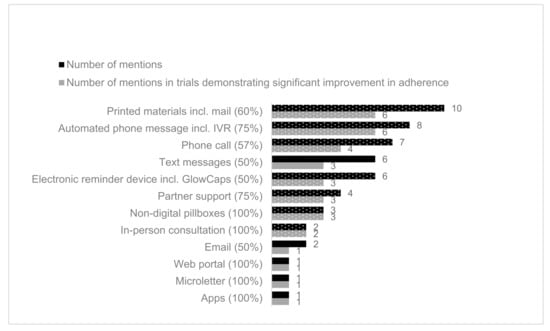

The percentage of studies that demonstrated significant results varied by the delivery type used in the studies, which was a mixture of mHealth and non-digital interventions (Figure 2). The most popular mHealth delivery type was automated phone messages (eight studies) followed by electronic reminder device (six studies). Non-digital interventions included printed materials (10 studies), telephone calls (seven studies), partner support from a pre-specified individual (e.g., friend or family) (four studies), non-electronic pillboxes (four studies), and in-person consultations (two studies). The least frequently used delivery types, email, web portal, microletter, and applications, were all associated with significant improvement in adherence. Of the delivery types used in more than three studies, automated phone messages, including Interactive Voice Recognition (IVR), partner support, and non-digital pillboxes, were associated with a higher percentage of studies reporting effective interventions (75%). Whereas printed materials, which were most frequently used, were only associated with 60% studies reporting a significant improvement in adherence.

Figure 2.

Number of mentions of delivery types in included studies (black) with effectiveness of intervention (grey). The proportion of delivery methods coded in effective interventions is provided in brackets after the delivery method name. Non mHealth delivery methods are shown in dotted. In Kessler 2018, two trial arms (alert and alert/partner) were effective, and the partner-only trial arm was not effective. For this chart, the delivery intervention “Partner” was still scored as effective for this study [59].

Pharmacists were the most common provider involved in the delivery of the intervention (five studies, four effective studies, 80%). Other providers included lay health workers and healthcare plan staff (six studies, four effective studies, 67%), partner support (four studies, three effective studies, 75%), and healthcare professionals (one study, no effective studies, 0%). In one study, the delivery staff was unknown [62].

The delivery period for the interventions ranged from 14 days to two years after the index date; however, the majority of studies had a delivery period of six months or less (nine studies, seven effective studies, 78%), and almost all of the trials had a delivery period of twelve months or less (15 studies, 9 effective studies, 60%). Two out of four studies (50%) where the treatment period was three months or less reported a significant improvement in adherence. This is compared to seven of nine studies (78%) when the intervention period was six months or less or five of eight studies (63%) where it was longer than six months (44 weeks to 2 years).

Whilst the delivery methods differed in their frequency of use, regular daily and monthly interventions were associated with higher rates of studies reporting significant improvement in adherence (83%, six studies and 86%, seven studies, respectively) compared to 71% in all studies. Interventions that were provided every 1–2 weeks, or on a non-recurrent basis, were associated with lower rates of studies reporting a significant improvement (50%, two studies and 0%, two studies, respectively).

3.5. Behaviour-Change Techniques (BCTs) Used in Included Studies

A total of 96 BCTs were coded in the intervention trial arms and 12 BCTs in usual care trial arms across the included studies. This was comprised of 30 unique BCT constructs of a possible 93 in the taxonomy (and one category of a possible 16, which was coded because there was insufficient detail to identify which individual technique was used in the intervention.) There were 64 BCTs employed in mHealth interventions, 22 BCTs employed in non-digital interventions, and 10 used by both mHealth and non-digital interventions in the same study. The number of BCTs coded in each study ranged from two BCTs (56) up to eleven BCTs (46). The mean number of BCTs coded in each study was six, and the median was five. Of the intervention BCTs coded, 33 were with a (+) to indicate “BCT present in all probability” and 63 coded with a (++) to indicate “BCT present beyond all reasonable doubt”.

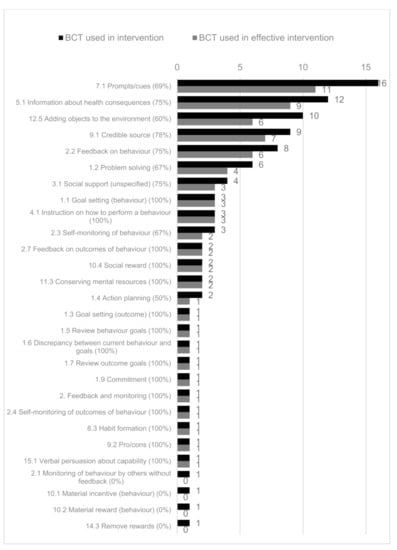

The BCT most frequently used in interventions were “7.1 Prompts/cues” (16 studies, 11 effective studies, 69%), followed by “5.1 Information about health consequences” (12 studies, 9 effective studies, 75%) and “12.5 Adding objects to the environment” (ten studies, six effective studies, 60%) (Figure 3). Of the BCTs coded in more than three studies, the BCTs with the highest proportion of successful interventions was “1.1 Goal setting (behaviour)” (three studies, three effective studies, 100%) and “4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behaviour” (three studies, three effective studies, 100%). In the BCTs coded in more than three studies, the next highest proportion of BCTs coded with effective interventions was “9.1 Credible source” (nine studies, seven effective studies, 78%). The lowest proportion was for “1.2 Problem solving” (six studies, four effective studies, 67%) and “2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour” (three studies, two effective studies, 67%).

Figure 3.

The number of Behaviour-Change Techniques (BCTs) used in all interventions (shown in black) and in effective interventions (shown in grey). The proportion of BCTs coded in effective interventions is provided in brackets after the BCT code name.

More interventions that included a greater number of BCTs were effective compared with interventions including a smaller number of techniques. In the ten trials that coded five or fewer BCTs, six had a significant improvement (60%). There was a significant improvement in six of seven trials (86%) that used 6–11 BCTs.

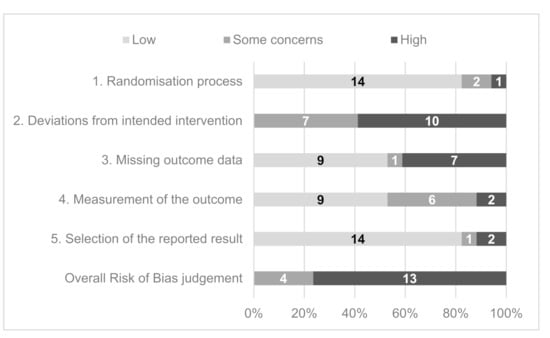

3.6. Study Quality and Risk of Bias

A summary of the RoB2 scores across the 17 studies is presented in Figure 4. Based on the overall risk of bias judgement, four studies were determined as having “some concerns”, and 13 had a “high” overall risk of bias. No included studies were deemed to have a “low” risk. “Deviations from intended intervention” had the greatest proportion of “high” risk scores. In 13 studies, there were potential or reported failures in implementing the intervention that could have affected the outcome, such as differential delivery of the intervention. Participant engagement with the intended intervention was not sufficiently assessed and accounted for in nine studies. This is a particular issue for automated interventions where it was not possible to assess participant engagement.

Figure 4.

Summary Risk of Bias 2 questionnaire domain and overall scores for included studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

There was moderate, positive evidence reported in this review of the effect of mHealth interventions to improve statin adherence. Twelve of the seventeen included studies (71%) demonstrating a significant effect, whilst five (29%) reported no impact on adherence. The studies used a variety of measures of adherence, including pharmacy refill data, electronically monitored pillbox openings, and self-reported adherence. Due to this heterogeneity, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis on the effect size of the mHealth interventions used. However, there was a wide range of reported relative improvement in adherence (2% to 63%) and effect size (0.06 to 0.75). There were no consistent characteristics (delivery method, length or frequency of intervention, control used, BCTs employed, or method of adherence measurement) between those with a higher relative improvement in adherence (>10%) compared to those with a lower relative improvement. The evidence on effectiveness from this review builds on the consensus from the literature that mHealth interventions improve statin adherence [30,31,34,39,63,64], though the inconsistency of results accords with the mixed evidence identified by other authors [33].

Twelve different delivery methods were used across the studies, consisting of seven mHealth and five non-digital. Most interventions were complex and multifaceted, utilising more than one delivery method, including a combination of mHealth and non-mHealth aspects. The methods used in the highest proportion of effective interventions were automated phone messages including IVR, partner support, and non-digital pillboxes. The only mHealth intervention of these three was automated phone messaging systems (IVR). There was limited evidence on the use of applications and websites, as they were only used in one study each. This was surprising given the current widespread use of apps and websites, though it may reflect the slower uptake rate of these technologies in the demographic of those taking statins. This trend may shift significantly if the study is to be repeated in a few years’ time. There is not a consensus across the literature on the most effective delivery methods to improve statin adherence. Other systematic reviews identified a range of successful delivery methods including automated phone messages and reminders [39,64], SMS [36,39,64], and pharmacist-led consultations [39]. In this review, three of six (50%) studies employing text messages were effective, while other reviews identified two of three (67%) studies [36], two of two (100%) studies [39], and nine of sixteen (56%) using IVR or SMS [64].

The majority of the included studies had relatively short trial periods (similar to trials reported in other reviews). From this review, fewer studies with treatment periods of three months or less demonstrated significant findings compared with studies with intervention periods longer than three months. However, other authors found no evidence of the impact of treatment duration on effectiveness [36,64].

The proportion of effective interventions was different with different frequencies of delivery. None of the studies that employed non-recurrent interventions demonstrated an improvement in adherence. However, there was not a clear pattern that more regular interventions were associated with higher levels of effectiveness. It may be hard to infer given the small numbers, or this may come from confounding with delivery methods (e.g., pillboxes, which are an effective intervention, are used daily). Different reviews found evidence that more frequent interventions improved effectiveness [22,64] or no evidence of a relationship [36]. Further evidence would be needed to enable conclusions to be drawn across different delivery methods.

The most frequently used Behaviour-Change Techniques (BCTs) in the identified mHealth interventions were “7.1 Prompts/cues” (16 studies, 69% effective), “5.1 Information about health consequences” (12 studies, 75% effective), and “12.5 Adding objects to the environment” (ten studies, 60% effective). In BCTs coded in more than three studies, the BCTs with the highest proportion of effective interventions were “1.1 Goal setting (behaviour)” (three studies), “4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behaviour” (three studies), and “9.1 Credible source” (nine studies), which had 100%, 100%, and 78% effective interventions, respectively. Following these, the next highest were “5.1 Information about health consequences” (12 studies), “2.2 Feedback on behaviour” (eight studies), and “3.1 Social support (unspecified)” (four studies), which all had 75% of studies with effective interventions. In this review, the BCT “7.1 Prompts/cues” was associated with 69% effective interventions, suggesting a relationship with improved effectiveness, though Kassavou found it was not associated with a larger effect size [64]. Interestingly, both the delivery method of partner support and the accompanying BCT of “3.1 Social support (unspecified)” were correlated with effective interventions (four studies, three effective studies, 75%), though there is mixed evidence for this relationship in the literature [23]. However, in one of these studies, the partner-support arm alone did not report significant results; it was only when the support was combined with an alert [59]. This review found that interventions that included more BCTs were more frequently associated with effective interventions, though other reviews that investigated CVD medication adherence and mHealth interventions found no evidence for this relationship [36,64].

The internal risk of bias for all of the included studies was rated as “some concerns” or “high”. There was a common risk of studies deviating from the protocol, as they could not measure how systematically the interventions were being delivered. In addition, automated mHealth interventions did not require a participant response, and it was difficult to gage patient engagement. Though the randomisation process appeared to be of low risk in many studies, it is important to recognise the potential for selection bias. Many trials used access to and capability of using mHealth technology as part of their inclusion and exclusion criteria, restricting certain groups and reducing their external validity.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

This review followed the PRISMA guidelines and used the checklist to report the appropriate information. It used the RoB2 framework to conduct suitable assessments on the quality of evidence gathered as recommended by the Cochrane Handbook. A comprehensive search strategy was developed, and papers were identified from both journals and the grey literature to identify the widest range of material possible.

The heterogeneity of approaches and recording of outcome measures in the included studies meant a meta-analysis was not appropriate. In some studies, the interventions were developed to improve general behaviours, such as physical activity or CV risk reduction, rather than purely medication adherence (though only the BCTs addressing adherence were coded). This intervention complexity may have reduced the impact of the intervention to improve adherence. In contrast, self-reported adherence measures may have overestimated the effect. In some studies, adherence rates of over 90% were reported in the usual care group, whilst the literature evaluates the true rate to be around 50%. This review, as others have done, included adherence measures for both the process of individuals filling prescriptions and for taking medication. However, it is plausible that optimal delivery methods and BCTs may differ between these two distinct behaviours.

The BCT analysis suffered from a lack of detail in the included studies, and approximately one-third of the BCTs were coded with lower confidence level. This has implications for the reproducibility and validity of the results. This review used a stringent method of coding BCTs and only recorded them when there was sufficient information provided. Whilst this may have strengthened the assessment validity, it may have underestimated the BCTs used. As with similar reviews, there was particularly limited information on usual care and the associated BCTs may have been underreported. Finally, although a BCT may have been used in multiple delivery arms within an intervention, it was only recorded once, which may have underestimated the impact of a BCT on individual behaviour.

4.3. Implications for Research and Practice

Statin non-adherence is a widespread problem, and there could be vast improvements in health outcomes and cost savings using mHealth interventions, which effectively improve adherence. mHealth interventions are likely to be scalable and cost-effective delivery mechanisms; however, it is important that they use intervention content that is most likely to be effective. This research indicates the delivery methods and BCTs employed in effective interventions that can be applied by healthcare professionals and policymakers to develop interventions that are more effective at improving patient adherence to statins adherence. The four primary recommendations from this review are for practitioners to use multifaceted interventions using multiple BCTs, consider automated messages as a digital delivery method from a credible source, provide instructions on taking statins, and set adherence goals with patients. Providers might also consider providing information about health consequences, feedback on adherence behaviour, and enlisting partner support. High proportions of interventions using these techniques were effective; however, further research into the optimal delivery frequency and treatment duration for each intervention mode is required. As part of a multifaceted intervention, developers and practitioners should consider combining automated messaging with non-digital delivery methods, such as partner support and pillboxes. Where possible, this should be delivered by healthcare professionals, such as pharmacists, doctors, or nurses. However, the inconsistency of results across studies may impact the generalisability of these recommendations across settings. These recommendations were identified from studies conducted in high- and middle-income countries with well-developed health systems. Caution should be taken to recognise the potential limited reproducibility of these results in other settings, particularly where access to statins or pharmacies or familiarity with mHealth technologies may be limited. In order to be able to learn from intervention design research, the intervention components should be described in more detail within journal articles. The Behaviour-Change Techniques Taxonomy [26,27] gives a recognised and consistent way of characterising the active ingredients of an intervention.

Although a suggested advantage of mHealth interventions is their relative cost, there was no information on the cost-effectiveness of the interventions included in this review. An understanding of this is important for the adoption and diffusion of these interventions amongst patients and practitioners.

5. Conclusions

Whilst the prevalence of CVD across the globe continues to rise, there is a growing role for statins as the primary medication for CV prevention and treatment. There are serious detrimental health impacts of poor adherence, yet methods to improve adherence are not well established. This review found positive evidence that mHealth interventions can improve statin adherence. The methods most related to effective interventions were automated phone messages, partner support, and non-digital pillboxes. Studies that employed more Behaviour-Change Techniques (BCTs) were correlated with higher effectiveness. The BCTs most frequently associated with effective interventions were “1.1 Goal setting (behaviour)”, “4.1 Instruction on how to perform a behaviour”, and “9.1 Credible source”. Other effective techniques were “5.1 Information about health consequences”, “2.2 Feedback on behaviour”, and “3.1 Social support (unspecified)”. Based on the results of this review, the four primary recommendations from this review are for practitioners to use multifaceted interventions using multiple BCTs, consider automated messages as a digital delivery method from a credible source, provide instructions on taking statins, and set adherence goals with patients. Further research should build on this review by assessing the optimal frequency of intervention delivery and understanding the generalisability of these suggested intervention techniques across settings and demographics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.B. and G.J.; methodology, Z.B. and G.J.; validation, Z.B., T.S. and G.J.; formal analysis, Z.B.; investigation, Z.B.; data curation, Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.B.; writing—review and editing, G.J. and T.S.; supervision, G.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search strategy for Medline database in Ovid (search conducted 17 July 2020).

Table A1.

Search strategy for Medline database in Ovid (search conducted 17 July 2020).

| Framework Element | # | Search Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Population Those prescribed statins for the primary or secondary prevention of CVD/dyslipidaemia. | 1 | Statin *.ti,ab,kw. |

| 2 | Atorvastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 3 | Cerivastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 4 | Fluvastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 5 | Fluindostatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 6 | Lovastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 7 | Mevastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 8 | Pitavastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 9 | Pravastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 10 | Rosuvastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 11 | Simvastatin *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 12 | HMG CoA reductase inhibitor *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 13 | Exp Hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA Reductase Inhibitors/ | |

| 14 | Hypercholesterol?emia.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 15 | Exp Hypercholesterolemia/ | |

| 16 | Dyslipid?emia.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 17 | Cholesterol *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 18 | Cardiovascular disease.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 19 | Cardiovascular disease/ | |

| 20 | CVD.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 21 | Heart disease.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 22 | CHD.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 23 | Coronary artery disease.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 24 | CAD.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 25 | Acute coronary syndrome *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 26 | ACS.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 27 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24 or 25 or 26 | |

| Intervention mHealth | 28 | Mobile health.ti,ab,kw. |

| 29 | mHealth.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 30 | M?health.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 31 | Telehealth *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 32 | Telemedicine.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 33 | Exp Telemedicine/ | |

| 34 | Telecomm *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 35 | Telecommunication/ | |

| 36 | Telephone *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 37 | Phone *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 38 | Ehealth.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 39 | Electronic health *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 40 | Digital health *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 41 | Web?based.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 42 | Internet.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 43 | Online.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 44 | Wireless technolog *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 45 | Health Information Technology.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 46 | Mobile technolog *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 47 | Text messag *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 48 | Texting.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 49 | Text-based.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 50 | SMS.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 51 | Short messag *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 52 | MMS.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 53 | Multimedia messag *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 54 | (Mobile adj1 app *).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 55 | Exp Mobile application/ | |

| 56 | Mobile phone *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 57 | Exp Mobile phone/ | |

| 58 | Cell phone *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 59 | Cellular phone *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 60 | Smartphone *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 61 | Exp Smartphone/ | |

| 62 | iPhone *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 63 | (Handheld adj1 computer *).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 64 | (Handheld adj1 device *).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 65 | (Tablet adj1 computer *).ti,ab,kw. | |

| 66 | iPad *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 67 | Smart watch *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 68 | Smart device *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 69 | Interactive voice respons *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 70 | IVR.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 71 | Exp Reminder system/ | |

| 72 | 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34 or 35 or 36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40 or 41 or 42 or 43 or 44 or 45 or 46 or 47 or 48 or 49 or 50 or 51 or 52 or 53 or 54 or 55 or 56 or 57 or 58 or 59 or 60 or 61 or 62 or 63 or 64 or 65 or 66 or 67 or 68 or 69 or 70 or 71 | |

| Outcome Medication adherence | 73 | Adheren *.ti,ab,kw. |

| 74 | Nonadheren *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 75 | Complian *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 76 | Noncomplian *.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 77 | Persistence.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 78 | Concordance.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 79 | Treatment refusal.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 80 | Drop out.ti,ab,kw. | |

| 81 | Exp Patient compliance/ | |

| 82 | exp Medication compliance/ | |

| 83 | 73 or 74 or 75 or 76 or 77 or 78 or 79 or 80 or 81 or 82 | |

| Study design RCTs | 84 | Randomized controlled trial.pt |

| 85 | Controlled clinical trial.pt | |

| 86 | Randomi?ed.ab | |

| 87 | Placebo.ab | |

| 88 | Drug therapy.fs | |

| 89 | Randomly.ab | |

| 90 | Trial.ab | |

| 91 | Groups.ab | |

| 92 | 85 or 86 or 87 or 88 or 89 or 90 or 91 or 92 | |

| COMBINE TERMS | 93 | 27 and 72 and 83 and 92 |

| 94 | limit 93 to yr = ”2000 − Current” |

Search strategy for Medline database in Ovid (search conducted 17 July 2020)—Search definitions: / = medical subject heading (MeSH); exp/ = exploded MeSH term; .ab = abstract; .fs = floating subheading; .kw = keyword; .pt = publication type; .sh = subject heading; .ti = title; * = search any number of characters at end of text; ? = search one or none characters in the text.

References

- Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.; Abajobir, A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abera, S.F.; Abyu, G.; Ahmed, M.; Aksut, B.; Alam, T.; Alam, K.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- How Statin Drugs Protect the Heart|Johns Hopkins Medicine. Available online: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/wellness-and-prevention/how-statin-drugs-protect-the-heart (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Cardiovascular Disease Prevention Overview—NICE Pathways. 2017. Available online: https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/cardiovascular-disease-prevention (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, e285–e350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaté, E. Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Guidelines for Assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. World Health Organization, 2007. Available online: www.inis.ie (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Martin-Ruiz, E.; Olry-de-Labry-Lima, A.; Ocaña-Riola, R.; Epstein, D. Systematic Review of the Effect of Adherence to Statin Treatment on Critical Cardiovascular Events and Mortality in Primary Prevention. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 23, 200–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, F.; Huffman, M.D.; Macedo, A.F.; Moore, T.H.M.; Burke, M.; Davey Smith, G.; Ward, K.; Ebrahim, S. Statins for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrecer, M.; Turk, S.; Drinovec, J.; Mrhar, A. Use of statins in primary and secondary prevention of coronary heart disease and ischemic stroke. Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 41, 567–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, R.L.; Fernandez-Llimos, F.; Frommer, M.; Benrimoj, C.; Garcia-Cardenas, V. Economic impact of medication non-adherence by disease groups: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e016982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.T.; Bussell, J.K. Medication adherence: WHO cares? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2011, 86, 304–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Evidence for Action. 2003, pp. 1–198. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42682/9241545992.pdf (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Perreault, S.; Dragomir, A.; Blais, L.; Bérard, A.; LaLonde, L.; White, M.; Pilon, D. Impact of better adherence to statin agents in the primary prevention of coronary artery disease. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 65, 1013–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poluzzi, E.; Strahinja, P.; Lanzoni, M.; Vargiu, A.; Silvani, M.C.; Motola, D.; Gaddi, A.; Vaccheri, A.; Montanaro, N. Adherence to statin therapy and patients’ cardiovascular risk: A pharmacoepidemiological study in Italy. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2008, 64, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mann, D.M.; Allegrante, J.; Natarajan, S.; Halm, E.A.; Charlson, M. Predictors of Adherence to Statins for Primary Prevention. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 2007, 21, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, S.P.; Alexander, K.P.; Lytle, B.; Heiss, G.; Peterson, E.D. Long-term adherence with cardiovascular drug regimens. Am. Hear. J. 2006, 151, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbass, I.; Revere, L.; Mitchell, J.; Appari, A. Medication Nonadherence: The Role of Cost, Community, and Individual Factors. Health Serv. Res. 2016, 52, 1511–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, A.J.; Puri, R.; Nissen, S.E. Statins in a Distorted Mirror of Media. 2020, Volume 22, pp. 1–8. Available online: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11883-020-00853-9 (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Ingersgaard, M.V.; Andersen, T.H.; Norgaard, O.; Grabowski, D.; Olesen, K. Reasons for Nonadherence to Statins—A Systematic Review of Reviews. Patient Prefer Adherence 2020, 14, 675–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicki, F.; Sinclair, F.; Wang, H.; Dailey, D.; Hsu, J.; Shaber, R. Patients’ Perspectives on Nonadherence to Statin Therapy: A Focus-Group Study. Perm. J. 2010, 14, 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rash, J.A.; Campbell, D.J.; Tonelli, M.; Campbell, T.S. A systematic review of interventions to improve adherence to statin medication: What do we know about what works? Prev. Med. 2016, 90, 155–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, E.; Giardini, A.; Savin, M.; Menditto, E.; Lehane, E.; Laosa, O.; Pecorelli, S.; Monaco, A.; Marengoni, A. Interventional tools to improve medication adherence: Review of literature. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2015, 9, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.; Berkhouse, H.; Schooler, M.; Pu, W.; Sun, A.; Gong, E.; Yan, L.L. Effectiveness of mHealth Interventions in Improving Medication Adherence Among People with Hypertension: A Systematic Review. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gellad, W.F.; Grenard, J.; McGlynn, E.A. A Review of Barriers to Medication Adherence: A Framework for Driving Policy Options; RAND Corporation PP: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 2009; Available online: https://www.rand.org/pubs/technical_reports/TR765.html (accessed on 12 January 2020).

- Ju, A.; Hanson, C.S.; Banks, E.; Korda, R.; Craig, J.C.; Usherwood, T.; Macdonald, P.; Tong, A. Patient beliefs and attitudes to taking statins: Systematic review of qualitative studies. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2018, 68, e408–e419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M.T.; Bussell, J.; Dutta, S.; Davis, K.; Strong, S.; Mathew, S. Medication Adherence: Truth and Consequences. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 351, 387–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Johnston, M. Theories and techniques of behaviour change: Developing a cumulative science of behaviour change. Health Psychol. Rev. 2012, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Richardson, M.; Johnston, M.; Abraham, C.; Francis, J.; Hardeman, W.; Eccles, M.P.; Cane, J.; Wood, C.E. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann. Behav. Med. 2013, 46, 81–95. Available online: https://academic.oup.com/abm/article/46/1/81-95/4563254 (accessed on 16 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. mHealth New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011; Available online: http://www.who.int/about/ (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Car, J.; Tan, W.S.; Huang, Z.; Sloot, P.; Franklin, B.D. eHealth in the future of medications management: Personalisation, monitoring and adherence. BMC Med. 2017, 15, 1–9. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28376771 (accessed on 14 April 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Dang, F.P.; Zhai, T.T.; Li, H.J.; Wang, R.J.; Ren, J.J. The effect of text message reminders on medication adherence among patients with coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019, 98, e18353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavradim, S.T.; Özer, Z.; Boz, I. Effectiveness of telehealth interventions as a part of secondary prevention in coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2019, 34, 585–603. Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/scs.12785 (accessed on 14 April 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coorey, G.M.; Neubeck, L.; Mulley, J.; Redfern, J. Effectiveness, acceptability and usefulness of mobile applications for cardiovascular disease self-management: Systematic review with meta-synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2018, 25, 505–521. Available online: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/2047487317750913 (accessed on 14 April 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, M.J.; Barnard, S.; Perel, P.; Free, C. Mobile phone-based interventions for improving adherence to medication prescribed for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 2018, CD012675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.; Chen, S.; Hong, L.; Sun, K.; Gong, E.; Li, C.; Yan, L.Y.; Schwalm, J.-D. Effect of Mobile Health Interventions on the Secondary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Can. J. Cardiol. 2017, 33, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandapur, Y.; Kianoush, S.; Kelli, H.M.; Misra, S.; Urrea, B.; Blaha, M.J.; Graham, G.; Marvel, F.A.; Martin, S.S. The role of mHealth for improving medication adherence in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Eur. Heart J. Qual. Care Clin. Outcomes 2016, 2, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dale, L.P.; Dobson, R.; Whittaker, R.; Maddison, R. The effectiveness of mobile-health behaviour change interventions for cardiovascular disease self-management: A systematic review. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2016, 23, 801–817. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26490093 (accessed on 14 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Sua, Y.S.; Jiang, Y.; Thompson, D.R.; Wang, W. Effectiveness of mobile phone-based self-management interventions for medication adherence and change in blood pressure in patients with coronary heart disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2020, 19, 192–200. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31856596 (accessed on 14 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Free, C.; Phillips, G.; Galli, L.; Watson, L.; Felix, L.; Edwards, P.; Patel, V.; Haines, A. The Effectiveness of Mobile-Health Technology-Based Health Behaviour Change or Disease Management Interventions for Health Care Consumers: A Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2013, 10, e1001362. Available online: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001362 (accessed on 14 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- van Driel, M.L.; Morledge, M.D.; Ulep, R.; Shaffer, J.P.; Davies, P.; Deichmann, R. Interventions to improve adherence to lipid-lowering medication. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, E.C.; Corbett, T.K.; Walsh, J.C.; Molloy, G.J. Behavior change techniques in apps for medication adherence: A content analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 50, e143–e146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armitage, L.C.; Kassavou, A.; Sutton, S. Do mobile device apps designed to support medication adherence demonstrate efficacy? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials, with meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, 32045. Available online: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/early/by/section (accessed on 14 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. Available online: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 (accessed on 15 April 2020). [CrossRef]

- Liberati, A.; Altman, D.G.; Tetzlaff, J.; Mulrow, C.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Clarke, M.; Devereaux, P.J.; Kleijnen, J.; Moher, D. The PRISMA Statement for Reporting Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Studies That Evaluate Health Care Interventions: Explanation and Elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000100. Available online: https://dx.plos.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100 (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.S.J. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in a randomized. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.0; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 15 April 2020).

- BCT Taxonomy Starter Pack. Available online: http://www.bct-taxonomy.com/pdf/StarterPack.pdf (accessed on 19 November 2020).

- Choudhry, N.K.; Isaac, T.; Lauffenburger, J.C.; Gopalakrishnan, C.; Lee, M.; Vachon, A.; Iliadis, T.L.; Hollands, W.; Elman, S.; Kraft, J.M.; et al. Effect of a Remotely Delivered Tailored Multicomponent Approach to Enhance Medication Taking for Patients With Hyperlipidemia, Hypertension, and Diabetes: The STIC2IT Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2018, 178, 1182–1189. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med15&NEWS=N&AN=30083727 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derose, S.; Green, K.; Marrett, E.; Tunceli, K.; Cheetham, T.C.; Chiu, V.Y.; Harrison, T.N.; Reynolds, K.; Vansomphone, S.S.; Scott, R.D. Automated outreach to increase primary adherence to cholesterol-lowering medications. JAMA Intern. Med. 2013, 173, 38–43. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med10&NEWS=N&AN=23403978 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, A.; Huseman, T.; Canamucio, A.; Marcus, S.C.; Asch, D.A.; Volpp, K.G.; Long, J. Evaluating individual feedback and partner feedback to improve statin medication adherence. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2016, 31, S213. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-01160482/full (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Salisbury, C.; O’Cathain, A.; Thomas, C.; Edwards, L.; Gaunt, D.; Dixon, P.; Hollinghurst, S.; Nicholl, J.; Large, S.; Yardley, L.; et al. Telehealth for patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: Pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2016, 353, i2647. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medc&NEWS=N&AN=27252245 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santo, K.; Singleton, A.; Rogers, K.; Thiagalingam, A.; Chalmers, J.; Chow, C.; Redfern, J. Medication reminder apps to improve medication adherence in coronary heart disease patients (MedApp-CHD): A randomised clinical trial. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 226. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-01935827/full (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Stacy, J.N.; Schwartz, S.M.; Ershoff, D.; Shreve, M.S. Incorporating tailored interactive patient solutions using interactive voice response technology to improve statin adherence: Results of a randomized clinical trial in a managed care setting. Popul. Health Manag. 2009, 12, 241–254. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med7&NEWS=N&AN=19848566 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, W.M.; Owen-Smith, A.A.; Tom, J.O.; Laws, R.; Ditmer, D.G.; Smith, D.H.; Waterbury, A.C.; Schneider, J.L.; Yonehara, C.Y.; Williams, A.; et al. Improving adherence to cardiovascular disease medications with information technology. Am. J. Manag. Care 2014, 20, SP502–SP510. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed15&NEWS=N&AN=606829929 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [PubMed]

- Volpp, K.G.; Troxel, A.B.; Mehta, S.J.; Norton, L.; Zhu, J.; Lim, R.; Wang, W.; Marcus, N.; Terweisch, C.; Caldarella, K.; et al. Effect of electronic reminders, financial incentives, and social support on outcomes after myocardial infarction the heartstrong randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2017, 177, 1093–1101. Available online: http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/data/journals/intemed/936414/jamainternal_volpp_2017_oi_170046.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vrijens, B.; Belmans, A.; Matthys, K.; de Klerk, E.; Lesaffre, E. Effect of intervention through a pharmaceutical care program on patient adherence with prescribed once-daily atorvastatin. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. 2006, 15, 115–121. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-00561702/full (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Fang, R.; Li, X. Electronic messaging support service programs improve adherence to lipid-lowering therapy among outpatients with coronary artery disease: An exploratory andomized control study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2016, 25, 664–671. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med13&NEWS=N&AN=26522838 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison, T.N.; Green, K.R.; Liu, I.-L.A.; Vansomphone, S.S.; Handler, J.; Scott, R.D.; Cheetham, T.C.; Reynolds, K. Automated Outreach for Cardiovascular-Related Medication Refill Reminders. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2016, 18, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, P.M.; Lambert-Kerzner, A.; Carey, E.P.; Fahdi, I.E.; Bryson, C.L.; Melnyk, S.D.; Bosworth, H.B.; Radcliff, T.; Davis, R.; Mun, H.; et al. Multifaceted intervention to improve medication adherence and secondary prevention measures after acute coronary syndrome hospital discharge: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 2014, 174, 186–193. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-00978324/full (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Ivers, N.; Schwalm, J.-D.; Bouck, Z.; McCready, T.; Taljaard, M.; Grace, S.L.; Cunningham, J.; Bosiak, B.; Presseau, J.; Witteman, H.O.; et al. Interventions supporting long term adherence and decreasing cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction (ISLAND): Pragmatic randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2020, 369, m1731. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=medl&NEWS=N&AN=32522811 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kessler, J.B.; Troxel, A.B.; Asch, D.A.; Mehta, S.J.; Marcus, N.; Lim, R.; Zhu, J.; Shrank, W.; Brennan, T.; Volpp, K.G. Partners and Alerts in Medication Adherence: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2018, 33, 1536–1542. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=med15&NEWS=N&AN=29546659 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kooy, M.J.; Van Wijk, B.; Heerdink, E.R.; De Boer, A.; Bouvy, M.L. A community pharmacist-led intervention to improve adherence to lipid-lowering treatment by counseling and an electronic reminder device: Results of a randomized controlled trial in The Netherlands. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2013, 35, 879–880. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-01006236/full (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Park, L.G.; Howie-Esquivel, J.; Chung, M. A text messaging intervention improves medication adherence for patients with coronary heart disease: A randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2013, 128, 261–268. Available online: http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed14&NEWS=N&AN=71338098 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Párraga-Martínez, I.; Rabanales-Sotos, J.; Lago-Deibe, F.; Téllez-Lapeira, J.M.; Escobar-Rabadán, F.; Villena-Ferrer, A.; Blasco-Valle, M.; Ferreras-Amez, J.M.; Morena-Rayo, S.; del Campo-del Campo, J.M.; et al. Effectiveness of a Combined Strategy to Improve Therapeutic Compliance and Degree of Control Among Patients With Hypercholesterolaemia. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2015, 15, 8. Available online: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/central/doi/10.1002/central/CN-02026850/full (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Marcolino, M.S.; Oliveira, J.A.Q.; D’Agostino, M.; Ribeiro, A.L.; Alkmim, M.B.M.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. The Impact of mHealth Interventions: Systematic Review of Systematic Reviews. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2018, 6, e23. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29343463 (accessed on 20 August 2020). [CrossRef]

- Kassavou, A.; Sutton, S. Automated telecommunication interventions to promote adherence to cardio-metabolic medications: Meta-analysis of effectiveness and meta-regression of behaviour change techniques. Health Psychol. Rev. 2018, 12, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).