Mirror Neurons and Pain: A Scoping Review of Experimental, Social, and Clinical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Search Strategy

- Population: Human participants (healthy individuals and/or patients with pain conditions).

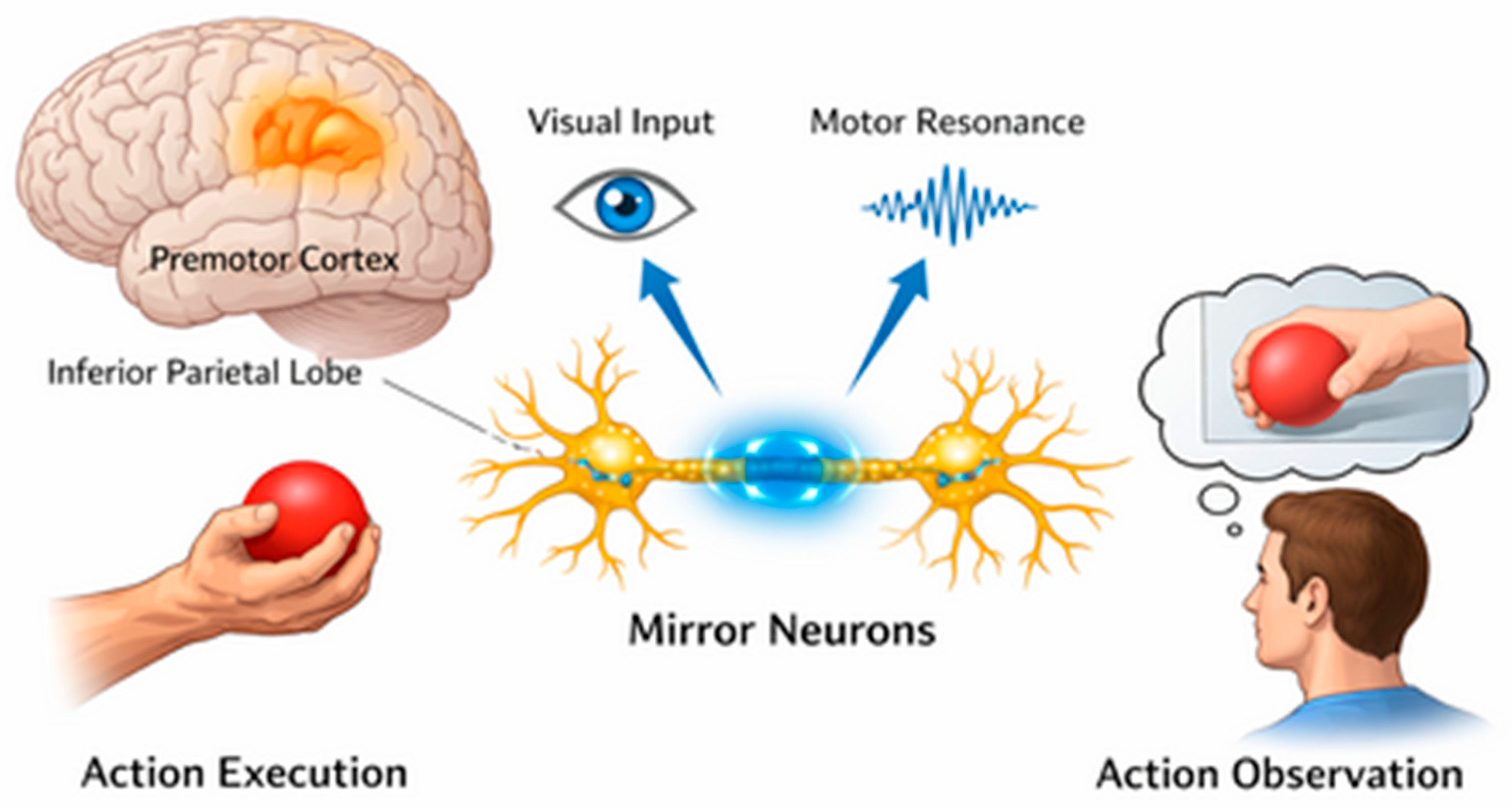

- Concept: MNS or closely related constructs (e.g., action observation, motor imagery, mirror visual feedback, embodied simulation), explicitly linked to pain, nociception, analgesia, or pain empathy.

- Context: Experimental laboratory studies, social neuroscience paradigms, and clinical or rehabilitative settings.

2.4. Information Sources

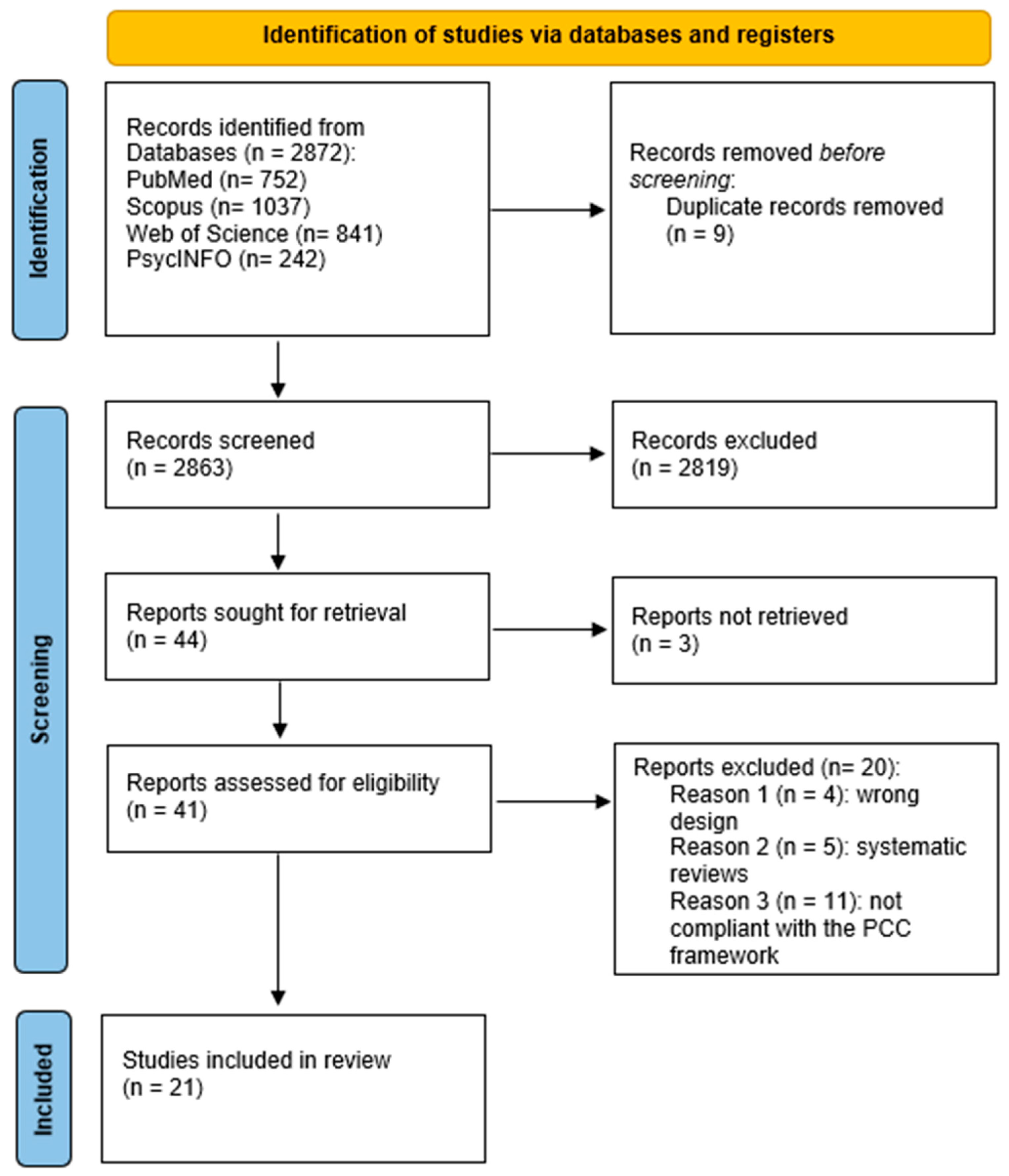

Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.5. Data Charting Process

- Bibliographic details (author, year, country);

- Study aims and design;

- Population characteristics (sample size, health status);

- Definition and operationalization of mirror neuron system-related constructs;

- Experimental or clinical paradigm (e.g., fMRI, EEG, mirror therapy, action observation);

- Type and context of pain (e.g., experimentally induced pain, chronic pain, pain empathy);

- Outcomes assessed (neural, behavioral, clinical);

- Main findings related to MNS and pain;

- Reported limitations.

2.6. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.7. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

3.3. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Practice

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.J.; Mogil, J.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiech, K. Deconstructing the sensation of pain: The influence of cognitive processes on pain perception. Science 2016, 354, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schafer, S.M.; Geuter, S.; Wager, T.D. Mechanisms of placebo analgesia: A dual-process model informed by insights from cross-species comparisons. Prog. Neurobiol. 2018, 160, 101–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, L.; Rizzolatti, G. The mirror neuron system. Arch. Neurol. 2009, 66, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- di Pellegrino, G.; Fadiga, L.; Fogassi, L.; Gallese, V.; Rizzolatti, G. Understanding motor events: A neurophysiological study. Exp. Brain Res. 1992, 91, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzolatti, G.; Sinigaglia, C. The functional role of the parieto-frontal mirror circuit: Interpretations and misinterpretations. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2010, 11, 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsytsarev, V. Methodological aspects of studying the mechanisms of consciousness. Behav. Brain Res. 2022, 419, 113684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, M.M.Y.; Han, Y.M.Y. Differential mirror neuron system (MNS) activation during action observation with and without social-emotional components in autism: A meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies. Mol. Autism 2020, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; George, T.G.; Sobolewski, C.M.; McMorrow, S.R.; Pacheco, C.; King, K.T.; Rochowiak, R.; Daniels-Day, E.; Park, S.M.; Speh, E.; et al. Mapping brain function underlying naturalistic motor observation and imitation using high-density diffuse optical tomography. Imaging Neurosci. 2025, 3, IMAG.a.153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamm, C.; Decety, J.; Singer, T. Meta-analytic evidence for common and distinct neural networks associated with directly experienced pain and empathy for pain. Neuroimage 2011, 54, 2492–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bieniek, H.; Bąbel, P. The Effect of the Model’s Social Status on Placebo Analgesia Induced by Social Observational Learning. Pain Med. 2022, 23, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atlas, L.Y. How Instructions, Learning, and Expectations Shape Pain and Neurobiological Responses. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2023, 46, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.M.; Zhang, K.X.; Wang, S.; Wang, N.; Wang, N.; Li, X.; Huang, L.P. Effectiveness of Mirror Therapy for Phantom Limb Pain: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 103, 988–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khoramdel, F.; Ravanbod, R.; Akbari, H. Effect of high-intensity laser therapy and mirror therapy on complex regional pain syndrome type I in the hand area: A randomized controlled trial. J. Hand Ther. 2025, 38, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Chen, S.; Li, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, G.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Shi, X.; Chen, X.; et al. Comparison of Sensory Observation and Somatosensory Stimulation in Mirror Neurons and the Sensorimotor Network: A Task-Based fMRI Study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 916990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, N.A.; Bakermans-Kranenburg, M.J.; Yoo, K.H.; Bowman, L.C.; Cannon, E.N.; Vanderwert, R.E.; Ferrari, P.F.; van Ijzendoorn, M.H. Assessing human mirror activity with EEG mu rhythm: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2016, 142, 291–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickok, G. Eight problems for the mirror neuron theory of action understanding in monkeys and humans. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2009, 21, 1229–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Implement. 2021, 19, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abolfazli, M.; Lajevardi, L.; Mirzaei, L.; Abdorazaghi, H.A.; Azad, A.; Taghizadeh, G. The effect of early intervention of mirror visual feedback on pain, disability and motor function following hand reconstructive surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 33, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunelli, S.; D’Auria, L.; Stefani, A.; Giglioni, F.; Mariani, G.; Ciccarello, M.; Benedetti, M.G. Is mirror therapy associated with progressive muscle relaxation more effective than mirror therapy alone in reducing phantom limb pain in patients with lower limb amputation? Int. J. Rehabil. Res. 2023, 46, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureen, A.; Ahmad, A.; Fatima, A.; Fatima, S.N. Effectiveness of mirror therapy on management of phantom limb pain and adjustment to limitation among prosthetic users; A single blinded randomized controlled trial. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2025, 42, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ol, H.; Van Heng, Y.; Danielsson, L.; Husum, H. Mirror therapy for phantom limb and stump pain: A randomized controlled clinical trial in landmine amputees in Cambodia. Scand. J. Pain 2018, 18, 603–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purushothaman, S.; Kundra, P.; Senthilnathan, M.; Sistla, S.C.; Kumar, S. Assessment of efficiency of mirror therapy in preventing phantom limb pain in patients undergoing below-knee amputation surgery-a randomized clinical trial. J. Anesth. 2023, 37, 387–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rothgangel, A.; Braun, S.; Winkens, B.; Beurskens, A.; Smeets, R. Traditional and augmented reality mirror therapy for patients with chronic phantom limb pain (PACT study): Results of a three-group, multicentre single-blind randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 1591–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, M.; Kanan, N. The effect of mirror therapy on the management of phantom limb pain. Agri 2016, 28, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariaty, S.; Taheri, A. The home-based mirror therapy in the reduction of phantom limb pain in unilateral below-knee amputees. J. Neurosci. Rural Pract. 2024, 15, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, S.B.; Perry, B.N.; Clasing, J.E.; Walters, L.S.; Jarzombek, S.L.; Curran, S.; Rouhanian, M.; Keszler, M.S.; Hussey-Andersen, L.K.; Weeks, S.R.; et al. A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Mirror Therapy for Upper Extremity Phantom Limb Pain in Male Amputees. Front. Neurol. 2017, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnall, B.D.; Li, H. Home-based self-delivered mirror therapy for phantom pain: A pilot study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2012, 44, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghelescu, D.L.; Kelly, C.N.; Steen, B.D.; Wu, J.; Wu, H.; DeFeo, B.M.; Scobey, K.; Burgoyne, L. Mirror Therapy for Phantom Limb Pain at a Pediatric Oncology Institution. Rehabil. Oncol. (Am. Phys. Ther. Association. Oncol. Sect.) 2016, 34, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Külünkoğlu, B.A.; Erbahçeci, F.; Alkan, A. A comparison of the effects of mirror therapy and phantom exercises on phantom limb pain. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2019, 49, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallik, A.K.; Pandey, S.K.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, S.; Kumar, A. Comparison of Relative Benefits of Mirror Therapy and Mental Imagery in Phantom Limb Pain in Amputee Patients at a Tertiary Care Center. Arch. Rehabil. Res. Clin. Transl. 2020, 2, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchio, A.; De Blasis, E.; De Blasis, V.; Santilli, V.; Spacca, G. Mirror therapy in complex regional pain syndrome type 1 of the upper limb in stroke patients. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2009, 23, 792–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCabe, C.S.; Haigh, R.C.; Ring, E.F.; Halligan, P.W.; Wall, P.D.; Blake, D.R. A controlled pilot study of the utility of mirror visual feedback in the treatment of complex regional pain syndrome (type 1). Rheumatology 2003, 42, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özdemir, E.C.; Elhan, A.H.; Küçükdeveci, A.A. Effects of mirror therapy in post-traumatic complex regional pain syndrome type-1: A randomized controlled study. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, jrm40417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, C.M.; de Carvalho, C.D.; Gomes, R.; Bonifácio de Assis, E.D.; Andrade, S.M. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation and Mirror Therapy for Neuropathic Pain After Brachial Plexus Avulsion: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Pilot Study. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 568261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Shrbaji, T.; Bou-Assaf, M.; Andias, R.; Silva, A.G. A single session of action observation therapy versus observing a natural landscape in adults with chronic neck pain–a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2023, 24, 983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suso-Martí, L.; León-Hernández, J.V.; La Touche, R.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Cuenca-Martínez, F. Motor Imagery and Action Observation of Specific Neck Therapeutic Exercises Induced Hypoalgesia in Patients with Chronic Neck Pain: A Randomized Single-Blind Placebo Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín Pérez, S.E.; Rodríguez, J.D.; Kalitovics, A.; de Miguel Rodríguez, P.; Bortolussi Cegarra, D.S.; Rodríguez Villanueva, I.; García Molina, Á.; Ruiz Rodríguez, I.; Montaño Ocaña, J.; Martín Pérez, I.M.; et al. Effect of Mirror Therapy on Post-Needling Pain Following Deep Dry Needling of Myofascial Trigger Point in Lateral Elbow Pain: Prospective Controlled Pilot Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, D.-E.P.; Msa, K.; Pt, M.-K. Effects of mirror therapy on muscle activity, muscle tone, pain, and function in patients with mutilating injuries: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2019, 98, e15157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.; Platano, D.; Donati, D.; Giorgi, F. Harnessing Mirror Neurons: A New Frontier in Parkinson’s Disease Rehabilitation-A Scoping Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossettini, G.; Carlino, E.; Testa, M. Clinical relevance of contextual factors as triggers of placebo and nocebo effects in musculoskeletal pain. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2018, 19, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, T.D.; Atlas, L.Y. The neuroscience of placebo effects: Connecting context, learning and health. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2015, 16, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.Y.; Lapanan, K.; Lin, Y.H.; Huang, C.W.; Lin, W.W.; Lin, M.M.; Lu, Z.L.; Lin, F.S.; Tseng, M.T. Integration of Prior Expectations and Suppression of Prediction Errors During Expectancy-Induced Pain Modulation: The Influence of Anxiety and Pleasantness. J. Neurosci. 2024, 44, e1627232024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benuzzi, F.; Lui, F.; Ardizzi, M.; Ambrosecchia, M.; Ballotta, D.; Righi, S.; Pagnoni, G.; Gallese, V.; Porro, C.A. Pain Mirrors: Neural Correlates of Observing Self or Others’ Facial Expressions of Pain. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schott, G.D. Pictures of pain: Their contribution to the neuroscience of empathy. Brain 2015, 138, 812–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pessoa, L. Understanding brain networks and brain organization. Phys. Life Rev. 2014, 11, 400–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heukamp, N.J.; Moliadze, V.; Mišić, M.; Usai, K.; Löffler, M.; Flor, H.; Nees, F. Beyond the chronic pain stage: Default mode network perturbation depends on years lived with back pain. Pain 2024, 166, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palese, A.; Rossettini, G.; Colloca, L.; Testa, M. The impact of contextual factors on nursing outcomes and the role of placebo/nocebo effects: A discussion paper. Pain Rep. 2019, 4, e716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author, Year, Country | Study Aims and Design | Population (n; Health Status) | MNS Construct (Definition/Operationalization) | Paradigm (Experimental/Clinical) | Type and Context of Pain | Outcomes Assessed | Main Findings | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abolfazli et al., 2019, Iran [20] | To evaluate the early effect of mirror visual feedback after hand surgery; RCT | n = 40; Adult Post-Hand Reconstructive Surgery | Mirror visual feedback as a visual-motor activation of the mirror system | Mirror therapy in clinical rehabilitation | Post-operative pain | Clinical (McGill Pain Questionnaire), functional | Improvement in pain and function in the MVF group compared to the control group | Small sample; Short follow-up |

| Al Shrbaji et al., 2023, Jordan [37] | Effect of a single action observation session in neck pain; RCT | n = 60; adults with chronic neck pain | Action observation is explicitly based on the mirror neuron system | Observation of movements vs. landscape | Chronic musculoskeletal pain | Clinical (VAS), Behavioral (PPT) | Pain reduction and increased pain threshold after AO | Single session intervention; No follow-up |

| Brunelli et al., 2023, Italy [21] | Compare MT + PMR vs. MT + relax vs. PT in PLP; RCT | n = 30; amputees with PLP | Mirror therapy as visual feedback for cortical reorganization | Clinical mirror therapy | Chronic neuropathic pain (PLP) | Clinical (BPI, PEQ) | Major pain benefits with PMR + MT | Limited sample; Short follow-up |

| Cacchio et al., 2009, Italy [33] | Evaluate MT in post-stroke CRPS-I; Placebo RCT | n = 48; post-stroke with CRPS-I upper limb | Mirror visual feedback to modulate sensory-motor maps | MT vs. Mirror Covered | Chronic Pain CRPS-I | Clinical (VAS), functional | Pain reduction only in the MT group | Specific population; Limited generalizability |

| McCabe et al., 2002, UK [34] | Explore MVF in CRPS-I; controlled pilot study | n = 8; CRPS-I upper limb | Mirror visual feedback to modulate body perception | Experimental MVF | Early/intermediate CRPS pain | Clinical (VAS) | Analgesic effect in the early stages | Very small sample; pilot design |

| Noureen et al., 2024, Pakistan [22] | Compare MT vs. PT in PLP; Single-blind RCT | n = 60; amputees with PLP | MT as mirror visuomotor activation | Rehabilitation TM | Chronic PLP | Clinical (NRS, TAPES) | Pain Improvement and Prosthetic Fit with TM | Single core; Limited follow-up |

| Ol et al., 2018, Cambodia [23] | To evaluate MT ± tactile stimulation in mine amputees; RCT | n = 60; PLP and stump pain | Mirror feedback for sensory integration | Clinical TM | PLP and stump pain | Clinical (VAS) | Pain reduction in the TM group | Specific context; Limited resources |

| Özdemir et al., 2024, Turkey [35] | MT added to rehab in CRPS-I hand; RCT | n = 34; Post-traumatic CRPS-I | Visual Mirror Feedback | MT + rehab | Chronic CRPS-I | Clinical (NRS) | No significant differences between groups | Small sample; short duration |

| Purushothaman et al., 2023, India [24] | Pre-emptive MT to prevent PLP; RCT | n = 50; BK amputation | Early mirror feedback to prevent maladaptive reorganization | Preventive MT | Post-operative PLP prevention | Clinical (incidence and NRS PLP) | Lower incidence and intensity of PLP in the MT group | Limited follow-up; Single center |

| Rothgangel et al., 2018, Netherlands [25] | Traditional MT vs. AR-MT vs. usual care (PACT); multicentre RCT | n = 75; Chronic PLP | Traditional and AR visual mirror feedback | MT/AR-MT clinical | Chronic PLP | Clinical (intensity, duration), functional | No clinically relevant differences between groups | Variable adherence; possible placebo effect |

| Yun & Kim, 2019, Korea [40] | Evaluate MT in mutilating hand injuries; RCT | n = 30; mutilating hand injuries | Mirror therapy for sensory-motor reorganization | MT + PT | Traumatic upper limb pain | Clinical (VAS), functional | Improvement of pain and function with TM | Small sample; short follow-up |

| Yildirim & Kanan, 2016, Turkey [26] | MT in the management of PLP; quasi-experimental | n = 15; amputees with PLP | Mirror feedback as visual limb replacement | Clinical TM | Chronic PLP | Clinical (Numeric Pain Intensity Scale) | Progressive reduction in PLP over 4 weeks | No control; Small sample |

| Ferreira et al., 2020, Brazil [36] | To evaluate the effect of tDCS associated with mirror therapy in post-avulsion neuropathic pain of the brachial plexus; Pilot Double-Blind RCT | n = 16; patients with brachial plexus avulsion and neuropathic pain | Mirror therapy as visual-motor feedback to modulate cortical reorganization | tDCS + MT vs. sham + MT | Chronic neuropathic pain | Clinical (VAS), functional | Greater pain reduction in the tDCS + MT group compared to the control | Small sample; pilot study; short follow-up |

| Suso-Martí et al., 2019, Spain [38] | To evaluate the effect of motor imagery and action observation on hypoalgesia in chronic neck pain; Single-blind RCT | n = 42; patients with chronic neck pain | Action observation and motor imagery as activation of the mirror neuron system | AO/MI of therapeutic exercises vs. placebo | Chronic musculoskeletal pain | Clinical (VAS), Behavioral (PPT) | AO/MI induce hypoalgesia and increased pain threshold compared to control | Short-term intervention; No follow-up |

| Shariaty & Taheri, 2024, Iran [27] | To evaluate the efficacy of home mirror therapy in PLP; RCT | n = 40; below-the-knee amputees with PLP | Mirror therapy as visual limb replacement for sensory-motor reorganization | Home-based MT vs. usual care | Chronic Phantom limb pain | Clinical (VAS) | Significant reduction in PLP intensity in the MT group | Home self-management; Possible variability of adherence |

| Martín Pérez et al., 2024, Spain [39] | To evaluate MT on post-needling pain in lateral elbow pain; Pilot Prospective Controlled Study | n = 44; patients with lateral epicondylalgia | Mirror visual feedback to modulate the perception of movement and pain | MVF after dry needling | Acute iatrogenic pain | Clinical (VAS), functional | Lower post-procedure pain intensity in the MT group | Pilot study; acute, non-chronic pain; short follow-up |

| Finn et al., 2017, USA [28] | To evaluate the efficacy of mirror therapy in upper limb PLP; RCT | n = 15; male amputees with upper limb PLP | Mirror therapy as a visual-motor activation of the mirror system | MT vs. Mirror Covered/Imagery | Chronic Phantom limb pain | Clinical (VAS), PLP frequency/duration | Improvement in PLP intensity and duration in the MT group | Small sample; Males only |

| Darnall & Li, 2012, USA [29] | To evaluate the feasibility and preliminary effects of home TM in PLP; Pilot prospective study | n = 40; amputees with PLP | Mirror therapy as self-administered visual feedback | Home-based self-delivered MT | Chronic Phantom limb pain | Clinical (NRS), sleep quality | Pain reduction and improved sleep after TM | Absence of control group; pilot design |

| Anghelescu et al., 2016, USA [30] | Describe the incidence/duration of PLP and compare pediatric patients treated with MT + standard care vs. standard care; Comparative retrospective study | n = 21; Children/adolescents and young adults with oncological amputation | Mirror therapy as visual-motor feedback to reverse the maladaptive reorganization of the sensory-motor system | Mirror therapy in the pediatric clinical setting | Phantom limb pain in pediatric oncology | Clinical: PLP incidence, PLP duration, pain intensity, analgesic use | MT is associated with a lower incidence of PLP at 1 year and shorter duration of PLP compared to the non-MT group | Retrospective drawing; small sample; non-randomized; possible therapeutic confounding |

| Anaforoğlu Külünkoğlu et al., 2019, Turkey [31] | Compare MT vs. phantom exercises on pain, QoL, and psychological status in PLP; Prospective RCT | n = 40; unilateral transtibial amputees with chronic PLP | MT as a visual illusion to modulate cortical reorganization; PE based on mental imagery | MT vs. Phantom Exercises for 4 weeks + 3- and 6-month follow-up | Chronic Phantom limb pain | Clinical (VAS), QoL (SF-36), Psychological Status (BDI) | Both improve, but MT is more effective than PE on pain intensity and BDI; better QoL outcomes in the MT group | Limited sample; impossibility of blindness; Variable home adherence |

| Mallik et al., 2020, India [32] | Compare relative benefits of MT vs. mental imagery in PLP; Prospective non-blinded RCT | n = 92; amputees with PLP in rehabilitation | MT as visual feedback for cortical reorganization; mental imagery as imaginative activation of motor circuits | MT vs. Mental imagery + conventional rehab | Chronic Phantom limb pain | Clinical: VAS at baseline, 4, 8, 12 months | Significant reduction in pain in both groups, but more effective MT than mental imagery (VAS 7 to 2.7 vs. 5.9) | Not blind; only clinical assessment of pain; absence of functional outcomes |

| Conceptual Domain | MNS-Related Construct | Paradigm or Intervention | Level of Inference on MNS | Pain Type or Context | Outcomes Assessed | Main Evidence Gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical rehabilitation | MT/MVF | Visual–motor illusion using mirror feedback | Indirect | Chronic pain, mainly phantom limb pain and CRPS | Pain intensity (e.g., VAS, NRS), functional measures, QoL | Absence of direct neurophysiological or neuroimaging markers of MNS activity; heterogeneity of protocols |

| Clinical rehabilitation | Action observation | Observation of goal-directed movements | Indirect | Chronic musculoskeletal pain | Pain intensity, PPT | Short-term outcomes; limited follow-up; small number of studies |

| Clinical rehabilitation | MI | Mental simulation of movement | Indirect | Chronic musculoskeletal pain | Pain intensity, PPT | Difficulty isolating MI-specific effects; variability in training protocols |

| Experimental or social neuroscience | Pain empathy | Observation of others in pain | Theoretical or inferential | Experimental pain, social contexts | Neural activation patterns, behavioral responses | Limited translation into clinical pain interventions |

| Experimental neuroscience | Sensorimotor resonance | Neurophysiological or neuroimaging proxies (e.g., EEG mu suppression, fMRI activation) | Indirect or proxy-based | Experimental paradigms | Neural markers of sensorimotor engagement | Rarely used as primary outcomes in clinical pain studies |

| Translational approaches | Combined or augmented interventions (e.g., MT + neuromodulation) | MT combined with adjunctive techniques | Indirect | Neuropathic and chronic pain | Pain intensity, functional outcomes | Small samples; pilot designs; lack of mechanistic clarification |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cascella, M.; Manchiaro, P.; Marinangeli, F.; Di Fabio, C.; Sollecchia, G.; Vittori, A.; Cerrone, V. Mirror Neurons and Pain: A Scoping Review of Experimental, Social, and Clinical Evidence. Healthcare 2026, 14, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020280

Cascella M, Manchiaro P, Marinangeli F, Di Fabio C, Sollecchia G, Vittori A, Cerrone V. Mirror Neurons and Pain: A Scoping Review of Experimental, Social, and Clinical Evidence. Healthcare. 2026; 14(2):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020280

Chicago/Turabian StyleCascella, Marco, Pierluigi Manchiaro, Franco Marinangeli, Cecilia Di Fabio, Giacomo Sollecchia, Alessandro Vittori, and Valentina Cerrone. 2026. "Mirror Neurons and Pain: A Scoping Review of Experimental, Social, and Clinical Evidence" Healthcare 14, no. 2: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020280

APA StyleCascella, M., Manchiaro, P., Marinangeli, F., Di Fabio, C., Sollecchia, G., Vittori, A., & Cerrone, V. (2026). Mirror Neurons and Pain: A Scoping Review of Experimental, Social, and Clinical Evidence. Healthcare, 14(2), 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14020280