Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This umbrella review identified 35 needs assessment tools for patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, with only a limited number integrating both general and disease-specific palliative care indicators.

- Significant gaps were found in the psychometric evidence of most tools, with NAT: PD-HF, SPICT, and NECPAL emerging as the most promising for this patient population.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Early identification of palliative care needs should prioritize tools that predict functional decline and incorporate both general and disease-specific indicators to support timely and targeted interventions.

- Further research is required to strengthen the psychometric properties and clinical utility of existing tools and to develop more holistic assessment tools covering physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains.

Abstract

Background/Objectives: Patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions experience illness burdens and palliative care needs comparable to those of oncology patients, yet palliative care is often introduced late. Identifying individuals with potential palliative care needs is complex, and although multiple tools exist, the most appropriate approach for assessing needs in this population remains unclear. This umbrella review aimed to identify and evaluate tools used to systematically assess palliative care in adults with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, with a specific focus on their content, structure, and psychometric properties. Methods: An umbrella review of systematic reviews was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guidance. Four electronic databases (Cochrane Library, CINAHL, PubMed, and PsycINFO) were searched from inception to 30 June 2025. Eligible systematic reviews were screened, critically appraised, and synthesized narratively. Results: Seven systematic reviews met the inclusion criteria, collectively identifying 35 unique needs-assessment tools. Five tools (SPICT, GSF-PIG, QUICK GUIDE, NECPAL, and P-CaRes) incorporated both general and disease-specific palliative care indicators. At the same time, four (PC-NAT, SPEED, NAT, and IPOS) addressed needs across physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. Psychometric data were available for six tools across three reviews. The original NAT and SPICT demonstrated good reliability; however, the Dutch version of the NAT showed poor validity. SPEED and one unnamed palliative care tool showed good reliability, whereas the Surprise Question demonstrated unclear validity. Italian-SPICT and Israeli-NECPAL exhibited strong content validity. Conclusions: Despite limited evidence, the NAT: PD-HF shows particular promise for identifying palliative care needs in patients with heart failure. Tools such as SPICT and NECPAL are widely used and adapted for advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, but further psychometric evaluation is required. Additional studies are needed to clarify the clinical utility of these tools for broader implementation in assessing palliative care needs.

1. Introduction

Chronic conditions are of increasing concern as the global population ages [1]. Conditions such as heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and dementia are prevalent and associated with substantial symptom burden, high utilization of healthcare services, and reduced quality of life [2,3]. Palliative care aims to enhance quality of life, alleviate suffering, and support decision-making for individuals with serious illness and their caregivers [4]. While palliative care research has traditionally focused on oncology, the population living with advanced non-malignant conditions is substantially larger and experiences comparable needs. Applying evidence generated primarily from malignant diseases can be misleading, given the unique, fluctuating trajectories and functional decline patterns observed in non-malignant conditions [5,6,7,8]. Patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions frequently experience heightened physical and psychological symptom burden [9,10,11,12]. Τhere is growing evidence that timely palliative care involvement improves quality of life, reduces unnecessary hospitalizations, and may even prolong survival [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Despite this, palliative care for non-malignant diseases is often initiated late, inconsistently, and inequitably—a pattern pointing to systemic challenges in early identification [20].

In this umbrella review, the term palliative care needs refers to the constellation of physical symptoms (e.g., pain, breathlessness), psychological distress (e.g., anxiety, depression), social support needs, and existential or spiritual concerns [4]. These needs are often multidimensional, persistent, and episodic, arising throughout the course of progressive chronic illness [12,21,22]. Their early recognition is essential for integrated, person-centred care [10]. Generalist palliative care—delivered by primary care clinicians, nurses, and other non-specialists—plays a key role in this process, while specialist services are typically reserved for complex or refractory needs [5,6,23].

A key barrier to delivering timely palliative care is the systematic identification of patients who may benefit from it [24,25]. Not all individuals with advanced non-malignant conditions require palliative care at a given moment, and busy clinical environments make comprehensive assessments impractical for all patients [26]. This underscores the need for efficient, evidence-based tools that support clinicians in proactively and consistently recognizing potential palliative care needs. A growing array of assessment tools has been developed for this purpose, varying widely in scope, structure, and intended use. Some tools focus on illness severity, disease progression, or frailty; others are tailored for specific clinical settings (e.g., emergency department, intensive care) [27] or particular patient groups, such as those with interstitial lung disease [28] or older adults [29]. Some tools are clinician-administered, whereas others can be self-reported by patients or caregivers [30,31]. Importantly, only a minority have been systematically validated for non-malignant conditions, and many remain underused in clinical practice. Existing systematic reviews tend to examine isolated conditions or narrow subsets of tools [32,33].

Given the multiplicity of tools, their conceptual differences, and the lack of consolidated evidence on their suitability for advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, a comprehensive synthesis is needed. Understanding which tools support early identification, which provide multidimensional assessment, and which combine both functions is crucial for guiding clinical practice and future research. Therefore, this umbrella review aimed to systematically identify and evaluate tools used to assess palliative care needs in adults with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, with particular attention to their content, structure, purpose, target population, and psychometric properties. Specifically, this review sought to answer the following research question:

What tools are available for assessing palliative care needs in patients with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, and what evidence exists regarding their content, structure, purpose, and psychometric properties?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

An umbrella review is a comprehensive examination of evidence compiled from multiple systematic research syntheses focusing on different interventions or perspectives on a particular topic [34]. Such reviews emphasize clinical conditions that are broad enough to have been evaluated with multiple interventions and aim to synthesize this diverse evidence base into a single accessible summary [34]. In the context of palliative care needs assessment—where numerous systematic reviews have examined different tools, populations, and settings using heterogeneous methods and sometimes reporting conflicting findings—an umbrella review provides a higher-level, methodologically rigorous synthesis capable of integrating and comparing this fragmented evidence base [34,35,36].

Accordingly, in this study, we applied an umbrella review design to collate and synthesize findings from existing systematic reviews on tools used to identify palliative care needs in adults with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions. This approach enables a broad overview of the available tools, their use across different care settings, and their psychometric properties [34], while allowing healthcare professionals to efficiently survey published evidence relevant to the research problem and identify the most suitable approaches for clinical decision-making [35].

The review process followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodological guidance for umbrella reviews [34,37]. This review was prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024553053) and conducted according to the PRIOR (Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews) statement to ensure methodological transparency in reporting objectives, methods, results, and conclusions. Critical methodological components—including eligibility criteria based on PICOTSS parameters, the search strategy, study screening and selection procedures, data extraction, risk of bias assessment, and the synthesis plan—were predefined in the registered protocol. The search and reporting procedures also complied with PRISMA 2020, with particular attention paid to documenting the search process and study flow to enhance clarity and rigor [38].

2.2. Search Strategy

The umbrella review search strategy was designed according to JBI’s methodological guidelines, and its conduct adhered to the standards outlined in the PROSPERO-registered protocol. Given our aim to evaluate needs-assessment tools that reflect current clinical practice, eligibility was restricted to systematic reviews published between 2014 and 2024. Older tools were excluded because they are frequently outdated, insufficiently validated, or no longer aligned with contemporary palliative care models. Search reporting followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines to ensure transparency and reproducibility [38]. The search was conducted by two independent reviewers across all selected databases using systematic combinations of a priori-defined keywords, Boolean operators, and eligibility criteria. Both the inclusion and exclusion criteria were guided by the PICOTSS framework, which refers to Population, Intervention (or Indicator), Comparison, Outcome, Time, Setting, and Study Design (Table 1). Restricting inclusion to tools evaluated in systematic reviews was intentional to preserve methodological rigor; however, we acknowledge that this decision may have led to the exclusion of newly developed tools that have not yet undergone systematic review.

Table 1.

Selection criteria for inclusion or exclusion of reviews.

We systematically reviewed four databases—the Cochrane Library (Table 2), CINAHL (Table S2), PubMed (Table S3), and PsycINFO (Table S4)—for studies meeting the eligibility criteria (Table 1). The database search was conducted from inception to 30 June 2025 to ensure that all potentially relevant reviews were captured. However, eligibility for inclusion was restricted a priori (as specified in the PROSPERO protocol) to systematic reviews published within the last ten full calendar years (2014–2024), to reflect contemporary clinical practice and avoid distortions introduced by partial publication years. One exception was made for a single earlier review published in 2013, which was retained because it represents the only systematic review covering several core palliative care identification tools (e.g., NECPAL, SPICT, RADPAC) for which no subsequent or updated systematic reviews exist. Excluding this review would have resulted in the omission of key tools still in current international use and would have introduced a content-related bias. This rationale is consistent with JBI, which notes that limits on a search strategy—such as the use of date restrictions—should be appropriate and explicitly justified, as guidance that allows the inclusion of older reviews when they provide unique, irreplaceable evidence [37].

Table 2.

Search strategy Database: Cochrane Library, from inception up to 30 June 2025.

2.3. Study Selection and Quality Appraisal

Two members of the review team independently conducted a critical appraisal of the reviews, utilizing a modified version of the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews [37]. The tool incorporates specific questions designed to verify the use of appropriate search methods and a systematic approach to reviewing data before extraction and synthesis. When discrepancies arose in the appraisal outcomes, they were resolved through discussion; if necessary, two additional reviewers were consulted.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

The characteristics of the included reviews and the needs assessment tools were collected before synthesis. Whenever possible, information on psychometric properties (e.g., validity, reliability, sensitivity, specificity) was also extracted; however, such data were not consistently reported across all reviews, and their presence or absence was explicitly noted in the synthesis. One reviewer extracted data on review characteristics, tool features, target populations, and reported psychometric properties, and three additional reviewers independently checked the extracted dataset for accuracy and completeness. The verification process addressed only the correctness and completeness of the extracted data, not the quality or suitability of the individual tools; any discrepancies were resolved by consensus.

Due to the heterogeneity of the included reviews in terms of populations, settings, and outcomes, and the predominantly qualitative nature of the reported findings, we used a narrative synthesis approach. We organized the tools in a comparative matrix according to four key domains: (a) scope (general vs. disease-specific); (b) purpose (early identification vs. comprehensive multidimensional needs assessment vs. end-of-life planning); (c) target population (e.g., heart failure, COPD, dementia); and (d) reported psychometric properties. When available, we extracted summary psychometric indices (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, inter-rater reliability, and validity types) directly from the systematic reviews.

Given that our unit of analysis was systematic reviews rather than primary psychometric or diagnostic accuracy studies, structured tools such as the COSMIN Risk of Bias checklist and QUADAS-2 were not applied; instead, we relied on the psychometric information as summarized by the included reviews. The narrative synthesis was conducted independently by two reviewers, with any disagreements resolved through discussion with a third reviewer. In line with our overarching aim, we did not conduct new psychometric analyses but instead integrated and interpreted the available evidence on validity and reliability reported in the systematic reviews. To enhance comparability and practical utility, the identified tools were ultimately grouped by target population, tool type (general vs. disease-specific), and primary purpose (early identification, comprehensive multidomain assessment, or mixed purpose).

3. Results

3.1. Selected Studies

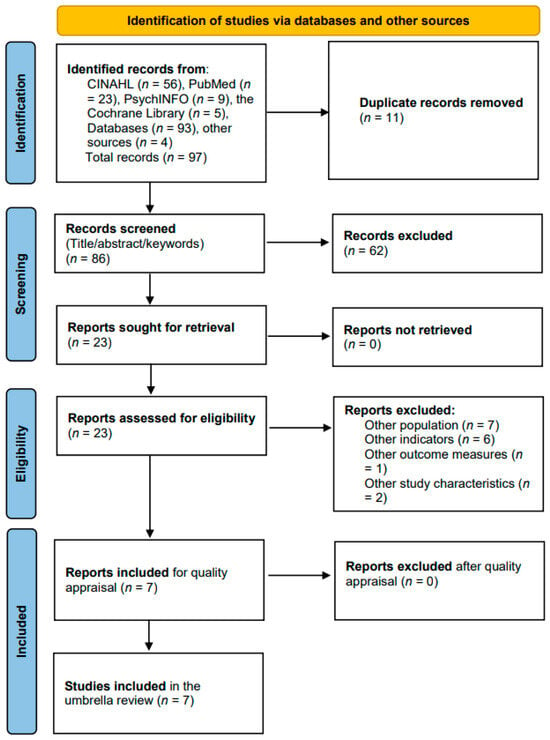

The search strategy identified 97 records across the four databases and additional sources. After removing 11 duplicates, 86 records were screened based on title, abstract, and keywords. Twenty-three full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, of which 16 did not meet the inclusion criteria. The remaining seven systematic reviews were critically appraised and included in the umbrella review (Figure 1, PRISMA flowchart).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart outlining the selection process, critical appraisal, and data extraction.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

Seven reviews were included: three systematic literature reviews, two systematic reviews with narrative synthesis, one systematic review with meta-analysis, and one mixed-method systematic review (Table 3). Most were published between 2019 and 2023, with one older review from 2013. Five reviews appeared in palliative care journals (e.g., BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, Palliative Medicine, BMC Palliative Care), and two in broader medical journals (Heart Failure Reviews, Academic Emergency Medicine). Most reviews searched four to seven databases, and all included PubMed/MEDLINE and Embase in their strategies. Three reviews reported psychometric data for at least one tool, while all seven reported on multiple needs-assessment tools.

Table 3.

Overview of the included reviews and their methodological characteristics.

3.3. Risk of Bias Across Studies

The risk of bias for the included reviews is summarized in Table S5. All seven systematic reviews met at least 9 of the 11 JBI critical appraisal criteria, indicating overall good methodological quality. Methodological limitations were most often related to the absence of an explicitly formulated research question or eligibility criteria structured in PICOTSS format, as well as incomplete reporting of publication bias assessment in several reviews (Table S5, Q1, Q9) [44]. In one review, the procedures used to minimize data extraction errors were insufficiently detailed, and publication bias assessment was not reported (Q7, Q9) [32]. Across several reviews [32,39,42,43,44], research questions were not fully specified in PICOTSS format, although study objectives were clearly articulated. Only one review presented uncertainty regarding whether specific directives for future research were appropriately addressed (Q11) [44]. Overall, the methodological quality of the included reviews was judged to be sufficient to support synthesis of findings on needs-assessment tools for adults with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions, given that all reviews demonstrated generally robust methodological standards and captured a diverse range of tools across multiple healthcare settings.

3.4. Characteristics of the Needs Assessment Tools

A total of 35 needs-assessment tools were identified across North America, Europe, Asia, and South America, developed for use in diverse chronic non-malignant and mixed populations. Most tools were originally developed in English, with many translated into multiple languages, supporting international applicability. Tools varied in format—predominantly paper-based, with a smaller number of electronic versions—and were designed for use in a range of settings including primary care, hospitals, emergency departments, hospice, and community services. Detailed characteristics for all tools are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the identified needs assessment tools (n = 35).

To facilitate comparison, tools were classified according to target population (e.g., heart failure–specific, dementia-specific, frailty, intellectual disability), scope (general vs. disease-specific; mixed where both were combined), and primary purpose. Purpose was categorized as: (i) early-identification tools designed to flag patients who may benefit from a palliative approach; (ii) comprehensive multidomain assessment tools that systematically evaluate physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs; and (iii) mixed-purpose tools, including tools assessing functional status, frailty, or quality of life, or tools combining screening with partial needs assessment. Some tools served more than one function. A summary classification by purpose is provided in Table 5.

Table 5.

Summary classification of needs-assessment tools by primary purpose.

Across the 35 tools, most were general in scope, while a smaller number were disease-specific or combined general and disease-specific indicators. Early-identification and end-of-life–focused tools constituted a substantial proportion of tools, whereas comprehensive multidomain assessments represented a smaller subset. Several tools combined early-identification with broader assessments, although no single tool explicitly addressed all three purposes concurrently. Paper-based formats predominated, with relatively few electronic versions and limited reporting of mixed formats. Most tools were clinician-administered, and only a minority permitted completion by patients or caregivers. Only a small subset incorporated a structured follow-up or action-planning component, indicating a persistent implementation gap between needs identification and care delivery.

Several tools included prognostic triggers such as the SQ, and when completion time was reported, some tools could be completed within minutes, supporting feasibility in routine clinical practice. While some tools combined general and disease-specific indicators, others relied exclusively on markers of decline or functional deterioration. Only a limited number of tools assessed all four core palliative care domains. Approximately two-thirds of the tools applied explicit criteria or cut-off values for identifying potential palliative care needs, whereas others provided structured clinical profiles without specified thresholds (Table 4).

3.5. Psychometric Properties of the Needs Assessment Tools

Overall, psychometric evidence for the identified tools was limited and unevenly reported across the included reviews (Table 6). Only three of the seven reviews provided data on validity or reliability, allowing tools to be grouped into three categories: (i) tools with the strongest and most consistent psychometric support, (ii) tools with weak or inconsistent evidence, and (iii) tools for which no psychometric evaluation was reported at the review level.

Table 6.

Summary of reported psychometric properties of the needs assessment tools.

3.5.1. Tools with Strongest Validity and/or Reliability

Evidence of good psychometric performance was reported for several tools. The original NAT: PD-HF demonstrated good reliability and validity across all evaluated domains [41]. The 13-item SPEED tool and the Peruvian Palliative Care Tool (Unnamed) also showed good reliability [42]. Xie et al. [44] reported good reliability for the original SPICT and very good content validity for the Italian-SPICT and Israeli-NECPAL, indicating solid measurement properties for these tools.

3.5.2. Tools with Inconsistent or Weak Psychometric Findings

Some tools showed mixed psychometric profiles. The Dutch version of NAT: PD-HF demonstrated poor validity despite the strong performance of the original version [41]. The SQ, although widely used, showed doubtful construct validity as a standalone prognostic measure, with weak correlations against several comparator tools [42].

3.5.3. Tools Lacking Psychometric Evaluation in the Included Reviews

For the remaining tools, including widely used tools such as IPOS, ESAS, PPS, GSF-PIG, NECPAL (original version), RADPAC, and many others, the included systematic reviews did not report psychometric findings. This absence reflects limitations in reporting within the reviews rather than an absence of validation studies in the broader literature. Table 6 summarizes the available psychometric evidence extracted exclusively from the systematic reviews included in this umbrella review.

It should be noted that widely used tools such as IPOS and ESAS have established psychometric support in primary validation studies; however, this evidence was not consistently reported in the included systematic reviews. Because our umbrella review relied exclusively on data extracted from systematic reviews, gaps in Table 5 and Table 6 mainly reflect limitations in reporting at the review level rather than the absence of underlying validation work. Future syntheses that integrate both umbrella review data and primary psychometric studies would be valuable for generating firm tool-specific recommendations.

4. Discussion

This umbrella review synthesizes evidence from seven systematic reviews and maps 35 needs-assessment tools designed to identify potential palliative care needs among adults with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions. By integrating findings across heterogeneous reviews—each differing in scope, definitions, populations, and methodological emphasis—this review offers a level of conceptual consolidation not previously available in the literature. Whereas individual reviews have focused narrowly on specific clinical groups (e.g., frailty, heart failure, emergency care) or on isolated types of tools, the present synthesis brings together the full spectrum of tools spanning early identification, multidimensional assessment, and end-of-life planning. In doing so, it highlights cross-cutting limitations, persistent operational barriers, and long-standing conceptual inconsistencies in how palliative care needs are defined and assessed.

A central insight emerging from this synthesis is that palliative care needs in non-malignant conditions cannot be reliably identified using mortality prediction alone. Patients with advanced heart failure, COPD, neurodegenerative disorders, frailty, and multimorbidity experience highly variable and non-linear trajectories, with fluctuating needs that often diverge from classical terminal decline patterns observed in cancer [23]. Reliance on mortality forecasting or deterioration prediction therefore reflects a conceptual lag, given that anticipatory, needs-based assessment—not survival estimation—is the essence of contemporary palliative care frameworks [40,77]. Tools combining both general and disease-specific indicators (e.g., SPICT, GSF-PIG, QUICK GUIDE, NECPAL, P-CaRES) show stronger conceptual alignment with these fluctuating patterns; however, they represent only a minority of the tools identified.

The widespread incorporation of the SQ across nearly one-third of included tools underscores its appeal as a rapid screening mechanism, especially in time-pressured environments such as emergency departments [42]. Yet evidence consistently demonstrates substantial limitations. SQ’s predictive accuracy varies markedly across malignant and non-malignant trajectories, with poorer performance in chronic non-cancer conditions [26]. Its utility is further constrained by heavy reliance on clinician intuition, which is influenced by experience, familiarity with specific disease trajectories, and comfort with prognostication [26]. The result is wide variability and a risk of both false-positive and false-negative identification, raising questions about its suitability as a standalone trigger. Tools integrating the SQ within a broader clinical framework (e.g., P-CaRES, Rainone tool) partially mitigate these limitations by contextualizing prognostic intuition with objective indicators.

Operational characteristics of the tools further illuminate challenges in clinical adoption. Completion times range from less than two minutes (ESAS, CSHA-CFS) to approximately 30 min for culturally adapted versions of NAT: PD-HF [21]. These discrepancies reflect a fundamental tension between feasibility and comprehensiveness. Tools assessing multidimensional needs require higher cognitive load, patient involvement, and clinical interpretation, and may be difficult to integrate into routine workflows without dedicated resources or multidisciplinary structures [33,78]. Only a minority of tools include an explicit action-planning component (e.g., NAT: PD-HF, SPEED), despite evidence that such mechanisms enhance clinical integration and care coordination [79]. In contrast, tools such as IPOS—despite well-established psychometric properties—lack formally embedded follow-up mechanisms, which may limit their practical impact in busy clinical environments [23].

A notable conceptual limitation across the identified tools is the incomplete incorporation of holistic palliative care domains. Only four tools (PC-NAT, SPEED, NAT: PD-HF, IPOS) explicitly cover physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions. This reflects a broader systemic challenge in operationalizing the biopsychosocial-spiritual model in routine care [22,80]. Psychosocial and spiritual needs often co-occur with physical symptom burden in patients with advanced non-malignant conditions [81,82,83,84,85] yet remain under-represented in most tools. Failure to capture these domains risks delayed referral, fragmented assessment, and suboptimal symptom management [86,87]. The omission of spiritual and social dimensions in particular points to a disconnect between theoretical palliative care models and the practical constraints of clinical assessment.

Psychometric evaluation remains another area of concern. Despite decades of tool development, rigorous validation evidence is scarce. The strongest psychometric support identified in the included reviews relates to the original NAT: PD-HF, SPEED, the Peruvian Palliative Care Tool, SPICT, Italian-SPICT, and Israeli-NECPAL [41,42,44]. Weak or inconsistent findings, such as the poor validity of the Dutch NAT: PD-HF, illustrate the consequences of insufficient cultural adaptation, inadequate sample sizes, and limited methodological rigor [21,41]. The absence of psychometric reporting for widely used tools such as IPOS, ESAS, PPS, GSF-PIG, and NECPAL (original version) in the included reviews reflects methodological constraints in systematic review practices rather than an absence of validation work in primary literature. Nonetheless, these persistent gaps signal a structural misalignment between tool development, validation, and implementation.

Finally, this umbrella review reveals significant conceptual inconsistency in how “palliative care needs” are defined across the literature. Some reviews operationalize needs narrowly in terms of proximity to end-of-life [39], others emphasize early identification [44], while others link needs primarily to prognostic triggers [24,25]. Such variation mirrors ongoing debate in the field regarding the scope and timing of palliative care, especially beyond oncology [88]. The structured classification used in this review (by purpose, scope, and population) offers a more coherent framework through which tools can be meaningfully compared and selected for clinical use.

4.1. Implications

The findings of this umbrella review have several implications for clinical practice, tool development, health systems, and future research. In clinical practice, the use of tools that incorporate both general and disease-specific indicators and that assess needs across physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains should be prioritized, as these tools offer a more holistic and clinically meaningful understanding of patient needs. Reliance on prognostic triggers such as the SQ should be supplemented with broader assessment approaches, particularly for non-malignant chronic conditions where disease trajectories are highly variable and prognostication remains uncertain. Tools that include explicit mechanisms for documenting or triggering action plans may further support decision-making and care coordination by linking identified needs to concrete clinical responses.

From a tool development perspective, future tools would benefit from being firmly grounded in a biopsychosocial-spiritual framework to ensure comprehensive coverage of the full spectrum of patient needs. Embedding structured action pathways within these tools is likely to enhance their clinical utility, while rigorous psychometric testing—including validity, reliability, and cultural adaptation—should be integral to their development to ensure their applicability across diverse populations and settings. At the health system and policy level, effective integration of validated needs-assessment tools into routine care requires adequate training, resource allocation, and supportive digital infrastructures. Policies that promote early identification and multidimensional assessment may reduce variability in care by decreasing reliance on clinician intuition alone. Achieving consistency in the use of such tools also depends on the standardization of terminology related to “palliative care needs,” which is currently used inconsistently across the literature and clinical practice.

Finally, several research priorities emerge. There is a clear need for high-quality validation studies, especially for tools that are widely implemented but have limited psychometric evaluation in existing systematic reviews. Future research should compare tools in real-world settings to determine their feasibility, performance, and impact on patient outcomes. Studies exploring how multidimensional needs assessment can be operationalized within time-constrained clinical environments will be essential for improving applicability. Moreover, longitudinal investigations are required to understand how these tools perform across the fluctuating trajectories typical of advanced non-malignant chronic conditions.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first umbrella review to systematically synthesize tools designed to identify potential palliative care needs in adults with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions. A comprehensive search strategy was employed across four major databases (Cochrane Library, CINAHL, PubMed, PsycINFO), and the quality of the included systematic reviews was independently appraised by multiple reviewers in accordance with JBI and PRISMA guidance. In contrast to the quality appraisal process for the systematic reviews, the assessment of “validation studies” within this umbrella review refers to primary research reporting psychometric properties (e.g., reliability, validity), which is essential for determining the appropriateness and methodological strength of needs-assessment tools in clinical practice.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, although every effort was made to retrieve all relevant systematic reviews, some omissions are possible. Because the umbrella-review design relies exclusively on published systematic reviews, emerging tools such as ID-Pall [89] or newly validated tools such as IPOS [90] were not captured unless already included within an eligible review. This introduces a structural limitation, whereby innovative or updated tools may be underrepresented due to the inherent lag between primary validation work and inclusion in systematic reviews.

Second, the depth and completeness of psychometric data available in this umbrella review were constrained by the reporting practices of the included systematic reviews. Only three of the seven reviews provided detailed psychometric information, limiting the extent to which meaningful comparisons could be drawn across tools. Although all available psychometric data were extracted and summarized (Table 6), the absence of standardized reporting (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha, inter-rater reliability, criterion validity) in several reviews reduced comparability. Moreover, three of the included systematic reviews were based on searches older than five years; they were retained because they contributed unique information about widely used tools still in practice, though future umbrella reviews may benefit from more targeted updates.

Third, several methodological considerations apply to the search strategy. By restricting inclusion to studies published in English, the review may be subject to language bias. Relevant studies published in other languages—especially given the global development of palliative care tools—may therefore have been excluded. We also excluded full-text-unavailable studies, which, while ensuring rigorous data extraction, may have inadvertently omitted relevant evidence. Additionally, our keyword strategy may not have fully captured semantic variations in terminology (e.g., “screening tools,” “palliative needs,” “supportive care”), leaving open the possibility of missing studies that use alternate descriptors. Future reviews may mitigate these issues through broader terminology mapping and inclusion of grey literature.

Fourth, this umbrella review did not evaluate clinical performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, accuracy) because these were rarely reported in the systematic reviews and were not the primary focus of the synthesis. Nevertheless, these measures are critical for determining the practical applicability of screening tools, and targeted searches of primary literature may be required to supplement future analyses. Another limitation concerns the potential for duplication bias, whereby the same primary studies may have been included across multiple systematic reviews. Such overlap, which is inherent in umbrella reviews, may disproportionately influence the representation of evidence for certain tools. Although we mitigated this by synthesizing at the level of the systematic review rather than weighting individual primary studies, some degree of duplication remains possible.

Finally, an overarching challenge arose from the conceptual heterogeneity in how “palliative care needs” were defined across the systematic reviews—from end-of-life identification [39] to early needs screening [44]. Although we addressed this issue by categorizing tools according to scope, population, and purpose, differences in underlying theoretical models and operational definitions may still influence interpretation. The limited and inconsistent reporting of psychometric properties across tools further restricts the ability to formulate strong, generalizable recommendations for clinical implementation.

5. Conclusions

This umbrella review synthesized evidence from seven systematic reviews and identified thirty-five tools developed or used to detect potential palliative care needs in adults with advanced non-malignant chronic conditions. Although these tools represent substantial effort to standardize early identification, most lack robust psychometric evaluation, limiting confidence in their accuracy and consistency. Among the available tools, the original NAT: PD-HF demonstrates the strongest evidence base for heart failure populations, while SPICT and NECPAL—particularly their validated international adaptations—appear most suitable for broader non-malignant chronic conditions due to their integration of general and disease-specific indicators. For clinical practice, the findings highlight the need to favour tools that offer multidimensional assessment, incorporate both general and condition-specific indicators, and provide actionable outputs that support care planning. Clinicians should avoid relying solely on prognostic triggers such as the SQ and instead adopt tools that enable systematic, holistic identification of evolving needs across physical, psychological, social, and spiritual domains. At the same time, the field requires more rigorous validation and comparative effectiveness research. Future work should evaluate tools within a shared conceptual and clinical framework, incorporating psychometric testing, diagnostic accuracy, and real-world usability across diverse settings. Strengthening this evidence base will allow clinicians and health systems to select tools that are not only conceptually sound but also operationally feasible and capable of improving patient outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare14010046/s1. Table S1: PRIOR Checklist (Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews); Table S2: Search strategy Database: EBSCO host, CINAHL from inception to 30 June 2025; Table S3: Search strategy Database: PubMed from inception to 30 June 2025; Table S4: Search strategy Database: PsycINFO from inception to 30 June 2025; Table S5: Risk of Bias Assessment of Included Systematic Reviews; Table S6: Potential Appraisal Tools Considered for Future Umbrella Reviews (COSMIN RoB and QUADAS-2).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K., S.C., D.P. and T.B.; methodology, C.K. and T.B.; literature search and screening, C.K. and T.B.; validation, C.K., S.C., D.P. and T.B.; formal analysis and synthesis of evidence, C.K. and T.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K.; writing—review and editing, S.C., D.P. and T.B.; visualization, C.K.; supervision, D.P. and T.B.; project administration, C.K. and T.B. Funding acquisition, not applicable. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its design as an umbrella review of previously published systematic reviews. No new data involving humans or animals were collected, and all data were obtained from publicly available published sources.

Registration

PROSPERO (CRD42024553053).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve the recruitment of human participants or the collection of individual patient data.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the colleagues who provided methodological and clinical feedback during the development of this umbrella review. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5.1 Thinking) for editorial and linguistic refinement (e.g., grammar, clarity, and phrasing). The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADL | Activities of Daily Living |

| A-qCPR | Admission Quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment for the Chronic Palliative Risk |

| ALS | Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis |

| COPD | Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease |

| COSMIN | COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments |

| CSHA-CFS | Canadian Study of Health and Aging–Clinical Frailty Scale |

| ED | Emergency Department |

| EDs | Emergency Departments |

| eFI | Electronic Frailty Index |

| ESAS | Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale |

| FAST | Functional Assessment Staging Test |

| GSF-PIG | Gold Standards Framework–Proactive Identification Guidance |

| HF | Heart Failure |

| IPOS | Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| KCCQ | Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| MQOL | McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| NAT: PD-HF | Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease–Heart Failure |

| NECPAL | NECesidades Paliativas |

| PC | Palliative Care |

| PC-NAT | Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool |

| PPS | Palliative Performance Scale |

| PRIOR | Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PROSPERO | International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews |

| QUADAS-2 | Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 |

| RAI | Risk Analysis Index |

| SPEED | Screening for Palliative and End-of-life care needs in the Emergency Department |

| SPICT | Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool |

| SQ | Surprise Question |

| SST | Simplified Screening Tool |

| TW-PCST | Taiwanese version–Palliative Care Screening Tool |

References

- Patel, P.; Lyons, L. Examining the Knowledge, Awareness, and Perceptions of Palliative Care in the General Public Over Time: A Scoping Literature Review. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2020, 37, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanuseputro, P.; Wodchis, W.P.; Fowler, R.; Walker, P.; Bai, Y.Q.; Bronskill, S.E.; Manuel, D. The Health Care Cost of Dying: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study of the Last Year of Life in Ontario, Canada. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0121759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, J.J.; Alam, S.; Cahill, L.E.; Drucker, A.M.; Gotay, C.; Kayibanda, J.F.; Kozloff, N.; Mate, K.K.V.; Patten, S.B.; Orpana, H.M. Global Burden of Disease Study Trends for Canada from 1990 to 2016. CMAJ 2018, 190, E1296–E1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavalieratos, D.; Corbelli, J.; Zhang, D.; Dionne-Odom, J.N.; Ernecoff, N.C.; Hanmer, J.; Hoydich, Z.P.; Ikejiani, D.Z.; Klein-Fedyshin, M.; Zimmermann, C.; et al. Association Between Palliative Care and Patient and Caregiver Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIlvennan, C.K.; Allen, L.A. Palliative Care in Patients with Heart Failure. BMJ 2016, 353, i1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance; World Health Organization. Global Atlas of Palliative Care, 2nd ed.; The Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lunney, J.R. Patterns of Functional Decline at the End of Life. JAMA 2003, 289, 2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seow, H.; O’Leary, E.; Perez, R.; Tanuseputro, P. Access to Palliative Care by Disease Trajectory: A Population-Based Cohort of Ontario Decedents. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e021147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidiac, C. The Evidence of Early Specialist Palliative Care on Patient and Caregiver Outcomes. Int. J. Palliat. Nurs. 2018, 24, 230–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaul, F.M.; Farmer, P.E.; Krakauer, E.L.; De Lima, L.; Bhadelia, A.; Jiang Kwete, X.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Gómez-Dantés, O.; Rodriguez, N.M.; Alleyne, G.A.O.; et al. Alleviating the Access Abyss in Palliative Care and Pain Relief—An Imperative of Universal Health Coverage: The Lancet Commission Report. Lancet 2018, 391, 1391–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwete, X.J.; Bhadelia, A.; Arreola-Ornelas, H.; Mendez, O.; Rosa, W.E.; Connor, S.; Downing, J.; Jamison, D.; Watkins, D.; Calderon, R.; et al. Global Assessment of Palliative Care Need: Serious Health-Related Suffering Measurement Methodology. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2024, 68, e116–e137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moens, K.; Higginson, I.J.; Harding, R.; Brearley, S.; Caraceni, A.; Cohen, J.; Costantini, M.; Deliens, L.; Francke, A.L.; Kaasa, S.; et al. Are There Differences in the Prevalence of Palliative Care-Related Problems in People Living with Advanced Cancer and Eight Non-Cancer Conditions? A Systematic Review. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2014, 48, 660–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currow, D.C.; Allingham, S.; Bird, S.; Yates, P.; Lewis, J.; Dawber, J.; Eagar, K. Referral Patterns and Proximity to Palliative Care Inpatient Services by Level of Socio-Economic Disadvantage. A National Study Using Spatial Analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.; Calanzani, N.; Curiale, V.; McCrone, P.; Higginson, I.J.; De Brito, M. Effectiveness and Cost-Effectiveness of Home Palliative Care Services for Adults with Advanced Illness and Their Caregivers. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2022, CD007760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, J.; Siemens, W.; Meerpohl, J.J.; Antes, G.; Meffert, C.; Xander, C.; Stock, S.; Mueller, D.; Schwarzer, G.; Becker, G. Effect of Specialist Palliative Care Services on Quality of Life in Adults with Advanced Incurable Illness in Hospital, Hospice, or Community Settings: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2017, 357, j2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, C.; Swami, N.; Krzyzanowska, M.; Hannon, B.; Leighl, N.; Oza, A.; Moore, M.; Rydall, A.; Rodin, G.; Tannock, I.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Cluster-Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet 2014, 383, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanbutsele, G.; Pardon, K.; Van Belle, S.; Surmont, V.; De Laat, M.; Colman, R.; Eecloo, K.; Cocquyt, V.; Geboes, K.; Deliens, L. Effect of Early and Systematic Integration of Palliative Care in Patients with Advanced Cancer: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2018, 19, 394–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bornais, C.; Deravin-Malone, L. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Lung Cancer: Evidence for and Barriers Against. Nurs. Palliat. Care 2016, 1, 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temel, J.S.; Greer, J.A.; Muzikansky, A.; Gallagher, E.R.; Admane, S.; Jackson, V.A.; Dahlin, C.M.; Blinderman, C.D.; Jacobsen, J.; Pirl, W.F.; et al. Early Palliative Care for Patients with Metastatic Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 733–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allsop, M.J.; Ziegler, L.E.; Mulvey, M.R.; Russell, S.; Taylor, R.; Bennett, M.I. Duration and Determinants of Hospice-Based Specialist Palliative Care: A National Retrospective Cohort Study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 1322–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssen, D.J.; Boyne, J.; Currow, D.C.; Schols, J.M.; Johnson, M.J.; La Rocca, H.-P.B. Timely Recognition of Palliative Care Needs of Patients with Advanced Chronic Heart Failure: A Pilot Study of a Dutch Translation of the Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease—Heart Failure (NAT:PD-HF). Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2019, 18, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rego, F.; Nunes, R. The Interface Between Psychology and Spirituality in Palliative Care. J. Health Psychol. 2019, 24, 279–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bausewein, C.; Daveson, B.A.; Currow, D.C.; Downing, J.; Deliens, L.; Radbruch, L.; Defilippi, K.; Lopes Ferreira, P.; Costantini, M.; Harding, R.; et al. EAPC White Paper on Outcome Measurement in Palliative Care: Improving Practice, Attaining Outcomes and Delivering Quality Services—Recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) Task Force on Outcome Measurement. Palliat. Med. 2016, 30, 6–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, N.; Phillips, E.; Zaurova, M.; Song, C.; Lamba, S.; Grudzen, C. Palliative Care Screening and Assessment in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2016, 51, 108–119.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, R.I.; Mitchell, G.; Francis, L.; Van Driel, M.L. What Diagnostic Tools Exist for the Early Identification of Palliative Care Patients in General Practice? A Systematic Review. J. Palliat. Care 2015, 31, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Downar, J.; Wegier, P.; Tanuseputro, P. Early Identification of People Who Would Benefit from a Palliative Approach—Moving From Surprise to Routine. JAMA Netw. Open 2019, 2, e1911146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.; Greenslade, J.; Shanmugathasan, S.; Doucet, K.; Widdicombe, N.; Chu, K.; Brown, A. PREDICT: A Diagnostic Accuracy Study of a Tool for Predicting Mortality within One Year: Who Should Have an Advance Healthcare Directive? Palliat. Med. 2015, 29, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, J.W.; Reigada, C.; Yorke, J.; Hart, S.P.; Bajwah, S.; Ross, J.; Wells, A.; Papadopoulos, A.; Currow, D.C.; Grande, G.; et al. The Adaptation, Face, and Content Validation of a Needs Assessment Tool: Progressive Disease for People with Interstitial Lung Disease. J. Palliat. Med. 2016, 19, 549–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardona-Morrell, M.; Hillman, K. Development of a Tool for Defining and Identifying the Dying Patient in Hospital: Criteria for Screening and Triaging to Appropriate aLternative Care (CriSTAL). BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2015, 5, 78–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K.; Noble, B. Improving the Delivery of Palliative Care in General Practice: An Evaluation of the First Phase of the Gold Standards Framework. Palliat. Med. 2007, 21, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highet, G.; Crawford, D.; Murray, S.A.; Boyd, K. Development and Evaluation of the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT): A Mixed-Methods Study. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2014, 4, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, E.A.T.; Murray, S.A.; Engels, Y.; Campbell, C. What Tools Are Available to Identify Patients with Palliative Care Needs in Primary Care: A Systematic Literature Review and Survey of European Practice. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A.; Girgis, A.; Davidson, P.M.; Newton, P.J.; Lecathelinais, C.; Macdonald, P.S.; Hayward, C.S.; Currow, D.C. Facilitating Needs-Based Support and Palliative Care for People with Chronic Heart Failure: Preliminary Evidence for the Acceptability, Inter-Rater Reliability, and Validity of a Needs Assessment Tool. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2013, 45, 912–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing Systematic Reviews: Methodological Development, Conduct and Reporting of an Umbrella Review Approach. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellali, I.; Miziou, S.; Dimitriadou-Maninia, D. Typology and Methodology of Reviews in Health Research. Nurs. Care Res. 2022, 2022, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wiechula, R.; Conroy, T.; Kitson, A.L.; Marshall, R.J.; Whitaker, N.; Rasmussen, P. Umbrella Review of the Evidence: What Factors Influence the Caring Relationship between a Nurse and Patient? J. Adv. Nurs. 2016, 72, 723–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Lockwood, C.; Porritt, K.; Pilla, B.; Jordan, Z. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stow, D.; Spiers, G.; Matthews, F.E.; Hanratty, B. What Is the Evidence That People with Frailty Have Needs for Palliative Care at the End of Life? A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElMokhallalati, Y.; Bradley, S.H.; Chapman, E.; Ziegler, L.; Murtagh, F.E.; Johnson, M.J.; Bennett, M.I. Identification of Patients with Potential Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review of Screening Tools in Primary Care. Palliat. Med. 2020, 34, 989–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remawi, B.N.; Gadoud, A.; Murphy, I.M.J.; Preston, N. Palliative Care Needs-Assessment and Measurement Tools Used in Patients with Heart Failure: A Systematic Mixed-Studies Review with Narrative Synthesis. Heart Fail. Rev. 2021, 26, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, S.W.; Yang, E.H.; Garrido Clua, M.; Kruhlak, M.; Campbell, S.; Villa-Roel, C.; Rowe, B.H. Screening Tools to Identify Patients with Unmet Palliative Care Needs in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2022, 29, 1229–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, A.; Evans, C.J. Needs-Based Triggers for Timely Referral to Palliative Care for Older Adults Severely Affected by Noncancer Conditions: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis. BMC Palliat. Care 2023, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Z.; Ding, J.; Jiao, J.; Tang, S.; Huang, C. Screening Instruments for Early Identification of Unmet Palliative Care Needs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2024, 14, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisberg, B. Functional Assessment Staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol. Bull. 1988, 24, 653–659. [Google Scholar]

- Bruera, E.; Kuehn, N.; Miller, M.J.; Selmser, P.; Macmillan, K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): A Simple Method for the Assessment of Palliative Care Patients. J. Palliat. Care 1991, 7, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.R.; Mount, B.M.; Strobel, M.G.; Bui, F. The McGill Quality of Life Questionnaire: A Measure of Quality of Life Appropriate for People with Advanced Disease. A Preliminary Study of Validity and Acceptability. Palliat. Med. 1995, 9, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, F.; Downing, G.M.; Hill, J.; Casorso, L.; Lerch, N. Palliative Performance Scale (PPS): A New Tool. J. Palliat. Care 1996, 12, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, C.P.; Porter, C.B.; Bresnahan, D.R.; Spertus, J.A. Development and Evaluation of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire: A New Health Status Measure for Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2000, 35, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emanuel, L.L.; Alpert, H.R.; Emanuel, E.E. Concise Screening Questions for Clinical Assessments of Terminal Care: The Needs Near the End-of-Life Care Screening Tool. J. Palliat. Med. 2001, 4, 465–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, K. The Gold Standards Framework in Community Palliative Care. Eur. J. Palliat. Care 2003, 10, 113–115. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, J.; Racine, E. The Racine Tool: Identifying Patients for Palliative Care in Family Practice. In Proceedings of the 15th International Congress on Care of the Terminally Ill, Montreal, QC, Canada, 19–23 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood, K. A Global Clinical Measure of Fitness and Frailty in Elderly People. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2005, 173, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainone, F.; Blank, A.; Selwyn, P.A. The Early Identification of Palliative Care Patients: Preliminary Processes and Estimates from Urban, Family Medicine Practices. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2007, 24, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, A.H.; Ganjoo, J.; Sharma, S.; Gansor, J.; Senft, S.; Weaner, B.; Dalton, C.; MacKay, K.; Pellegrino, B.; Anantharaman, P.; et al. Utility of the “Surprise” Question to Identify Dialysis Patients with High Mortality. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2008, 3, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waller, A.; Girgis, A.; Currow, D.; Lecathelinais, C. Development of the Palliative Care Needs Assessment Tool (PC-NAT) for Use by Multi-Disciplinary Health Professionals. Palliat. Med. 2008, 22, 956–964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissman, D.E.; Meier, D.E. Identifying Patients in Need of a Palliative Care Assessment in the Hospital Setting a Consensus Report from the Center to Advance Palliative Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richards, C.T.; Gisondi, M.A.; Chang, C.-H.; Courtney, D.M.; Engel, K.G.; Emanuel, L.; Quest, T. Palliative Care Symptom Assessment for Patients with Cancer in the Emergency Department: Validation of the Screen for Palliative and End-of-Life Care Needs in the Emergency Department Instrument. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glajchen, M.; Lawson, R.; Homel, P.; DeSandre, P.; Todd, K.H. A Rapid Two-Stage Screening Protocol for Palliative Care in the Emergency Department: A Quality Improvement Initiative. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2011, 42, 657–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaid, P. A Quick Guide to Identifying Patients for Supportive and Palliative Care; NHS: Leeds, UK, 2011.

- Grudzen, C.R.; Stone, S.C.; Morrison, R.S. The Palliative Care Model for Emergency Department Patients with Advanced Illness. J. Palliat. Med. 2011, 14, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoonsen, B.; Engels, Y.; Van Rijswijk, E.; Verhagen, S.; Van Weel, C.; Groot, M.; Vissers, K. Early Identification of Palliative Care Patients in General Practice: Development of RADboud Indicators for PAlliative Care Needs (RADPAC). Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2012, 62, e625–e631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Batiste, X.; Martínez-Muñoz, M.; Blay, C.; Amblàs, J.; Vila, L.; Costa, X.; Villanueva, A.; Espaulella, J.; Espinosa, J.; Figuerola, M.; et al. Identifying Patients with Chronic Conditions in Need of Palliative Care in the General Population: Development of the NECPAL Tool and Preliminary Prevalence Rates in Catalonia. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2013, 3, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quest, T.; Herr, S.; Lamba, S.; Weissman, D. Demonstrations of Clinical Initiatives to Improve Palliative Care in the Emergency Department: A Report From the IPAL-EM Initiative. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2013, 61, 661–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schulman, K.A.; Zalenski, R.J.; Johnson, C. Palliative Care Screening in the Emergency Department: 660. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, S283–S284. [Google Scholar]

- George, N.; Barrett, N.; McPeake, L.; Goett, R.; Anderson, K.; Baird, J. Content Validation of a Novel Screening Tool to Identify Emergency Department Patients with Significant Palliative Care Needs. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2015, 22, 823–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clegg, A.; Bates, C.; Young, J.; Ryan, R.; Nichols, L.; Ann Teale, E.; Mohammed, M.A.; Parry, J.; Marshall, T. Development and Validation of an Electronic Frailty Index Using Routine Primary Care Electronic Health Record Data. Age Ageing 2016, 45, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.E.; Arya, S.; Schmid, K.K.; Blaser, C.; Carlson, M.A.; Bailey, T.L.; Purviance, G.; Bockman, T.; Lynch, T.G.; Johanning, J. Development and Initial Validation of the Risk Analysis Index for Measuring Frailty in Surgical Populations. JAMA Surg. 2017, 152, 175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotogni, P.; De Luca, A.; Evangelista, A.; Filippini, C.; Gili, R.; Scarmozzino, A.; Ciccone, G.; Brazzi, L. A Simplified Screening Tool to Identify Seriously Ill Patients in the Emergency Department for Referral to a Palliative Care Team. Minerva Anestesiol. 2017, 83, 474–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B.; Boyd, K.; Steyn, J.; Kendall, M.; Macpherson, S.; Murray, S.A. Computer Screening for Palliative Care Needs in Primary Care: A Mixed-Methods Study. Br. J. Gen. Pr. 2018, 68, e360–e369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijmoeth, C.; Echteld, M.A.; Assendelft, P.; Christians, M.; Festen, D.; Van Schrojenstein Lantman-de Valk, H.; Vissers, K.; Groot, M. Development and Applicability of a Tool for Identification of People with Intellectual Disabilities in Need of Palliative Care (PALLI). Res. Intellect. Disabil. 2018, 31, 1122–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtagh, F.E.; Ramsenthaler, C.; Firth, A.; Groeneveld, E.I.; Lovell, N.; Simon, S.T.; Denzel, J.; Guo, P.; Bernhardt, F.; Schildmann, E.; et al. A Brief, Patient- and Proxy-Reported Outcome Measure in Advanced Illness: Validity, Reliability and Responsiveness of the Integrated Palliative Care Outcome Scale (IPOS). Palliat. Med. 2019, 33, 1045–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veldhoven, C.M.M.; Nutma, N.; De Graaf, W.; Schers, H.; Verhagen, C.A.H.H.V.M.; Vissers, K.C.P.; Engels, Y. Screening with the Double Surprise Question to Predict Deterioration and Death: An Explorative Study. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakan, G.; Ozen, M.; Azak, A.; Erdur, B. Determination of the Characteristics and Outcomes of the Palliative Care Patients Admitted to the Emergency Department. Int. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 53, 100934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amado Tineo, J.P.; Vasquez Alva, R.; Huari Pastrana, R.; Huamán Manrique, P.Z.; Oscanoa Espinoza, T. Need for Palliative Care in Patients Admitted to Emergency Departments of Three Tertiary Hospitals: Evidence from a Latin-American City. Palliat. Med. Pr. 2020, 14, 236–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.-F.; Lai, C.-C.; Fu, P.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C.; Huang, S.-J.; Chu, D.; Lin, S.-P.; Chaou, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Chen, H.-H. A-qCPR Risk Score Screening Model for Predicting 1-Year Mortality Associated with Hospice and Palliative Care in the Emergency Department. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, R.T.; Petrie, M.C.; Jackson, C.E.; Jhund, P.S.; Wright, A.; Gardner, R.S.; Sonecki, P.; Pozzi, A.; McSkimming, P.; McConnachie, A.; et al. Which Patients with Heart Failure Should Receive Specialist Palliative Care? Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2018, 20, 1338–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, G.K.; Senior, H.E.; Rhee, J.J.; Ware, R.S.; Young, S.; Teo, P.C.; Murray, S.; Boyd, K.; Clayton, J.M. Using Intuition or a Formal Palliative Care Needs Assessment Screening Process in General Practice to Predict Death within 12 Months: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 384–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, P.M.; Ellis-Smith, C.I.; Daveson, B.A.; Ryan, K.; Mahon, N.G.; McAdam, B.; McQuillan, R.; Tracey, C.; Howley, C.; O’Gara, G.; et al. Understanding How a Palliative-Specific Patient-Reported Outcome Intervention Works to Facilitate Patient-Centred Care in Advanced Heart Failure: A Qualitative Study. Palliat. Med. 2018, 32, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulmasy, D.P. A Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Model for the Care of Patients at the End of Life. Gerontol. 2002, 42, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, Z.J.; Xue, S.; Jones, M.P.; Ravindran, A.V. Depression, Anxiety, and Other Mental Disorders in Patients with Cancer in Low- and Lower-Middle–Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JCO Glob. Oncol. 2021, 7, 1233–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerullo, G.; Videira-Silva, A.; Carrancha, M.; Rego, F.; Nunes, R. Complexity of Patient Care Needs in Palliative Care: A Scoping Review. Ann. Palliat. Med. 2023, 12, 791–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seven, A.; Sert, H. Anxiety, Dyspnea Management, and Quality of Life in Palliative Care Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial. FNJN 2023, 31, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batstone, E.; Bailey, C.; Hallett, N. Spiritual Care Provision to End-of-life Patients: A Systematic Literature Review. J. Clin. Nurs. 2020, 29, 3609–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fradelos, E.C. Spiritual Well-Being and Associated Factors in End-Stage Renal Disease. Sci. World J. 2021, 2021, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, C.P.H.; Bowsher, J.; Maloney, J.P.; Lillis, P.P. Social Support: A Conceptual Analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Molassiotis, A.; Chung, B.P.M.; Tan, J.-Y. Unmet Care Needs of Advanced Cancer Patients and Their Informal Caregivers: A Systematic Review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, C.; Ingleton, C.; Gott, M.; Ryan, T. Exploring the Transition from Curative Care to Palliative Care: A Systematic Review of the Literature. BMJ Support. Palliat. Care 2011, 1, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teike Lüthi, F.; Bernard, M.; Vanderlinden, K.; Ballabeni, P.; Gamondi, C.; Ramelet, A.-S.; Borasio, G.D. Measurement Properties of ID-PALL, A New Instrument for the Identification of Patients with General and Specialized Palliative Care Needs. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2021, 62, e75–e84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, E.; Müller, M.J.; Boehlke, C.; Schäfer, H.; Quante, M.; Becker, G. Screening for Palliative Care Need in Oncology: Validation of Patient-Reported Outcome Measures. J. Pain. Symptom Manag. 2024, 67, 279–289.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.