Large Language Models for Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mental Disorders: A Review of Systematic Reviews

Abstract

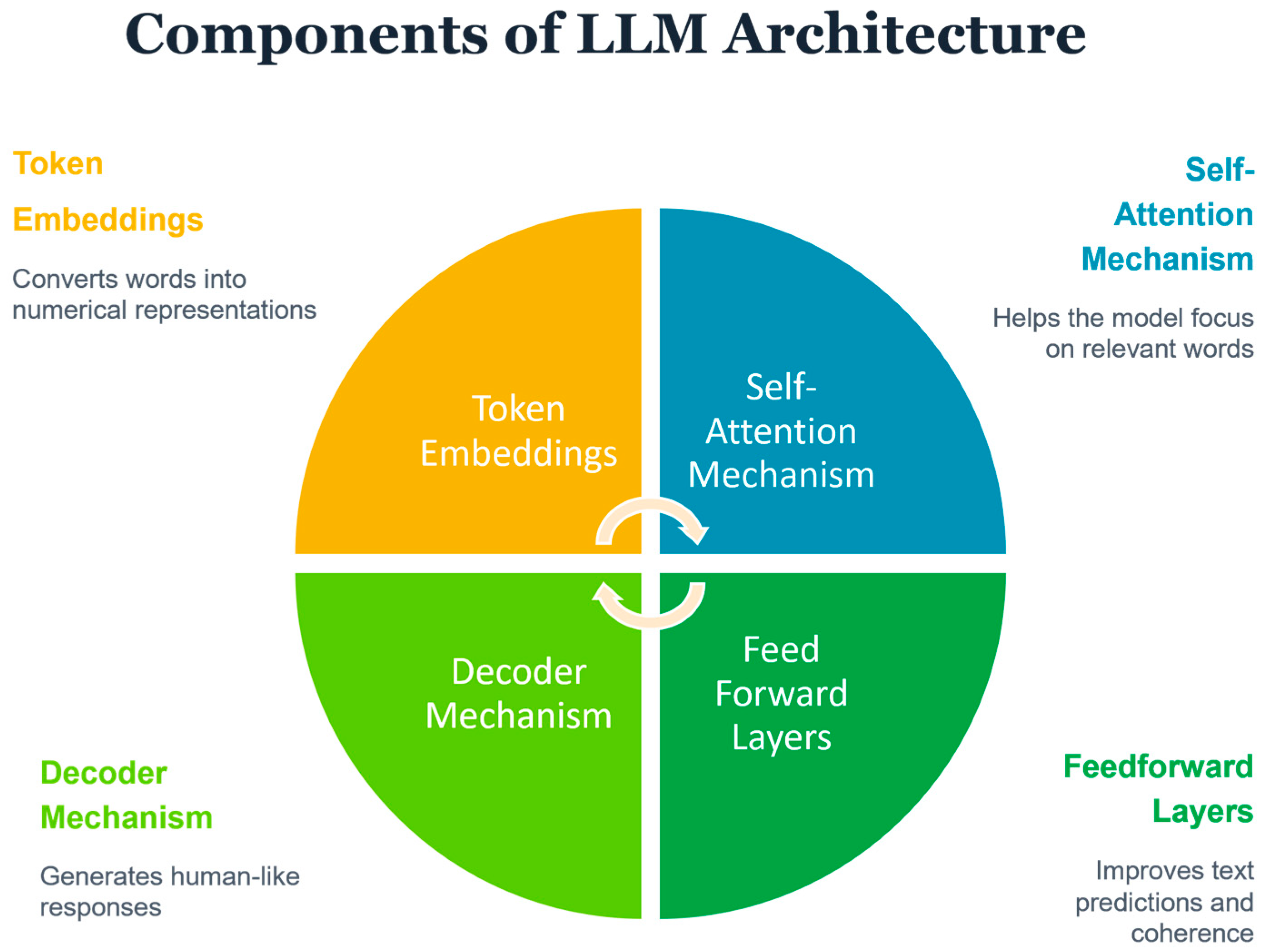

1. Introduction

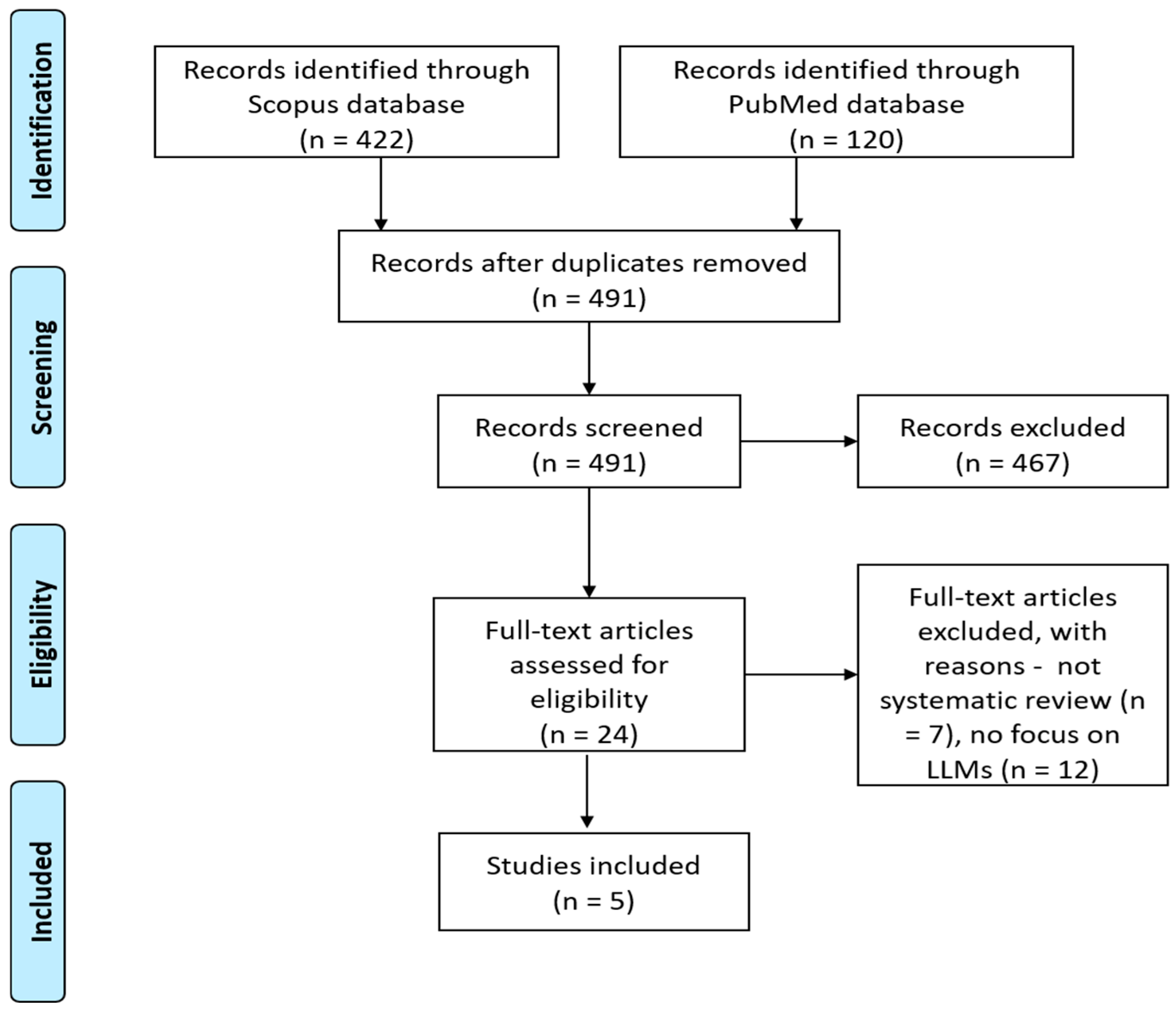

2. Methodology

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Outcomes

3.2. Quality Assessment of Reviews and Original Studies

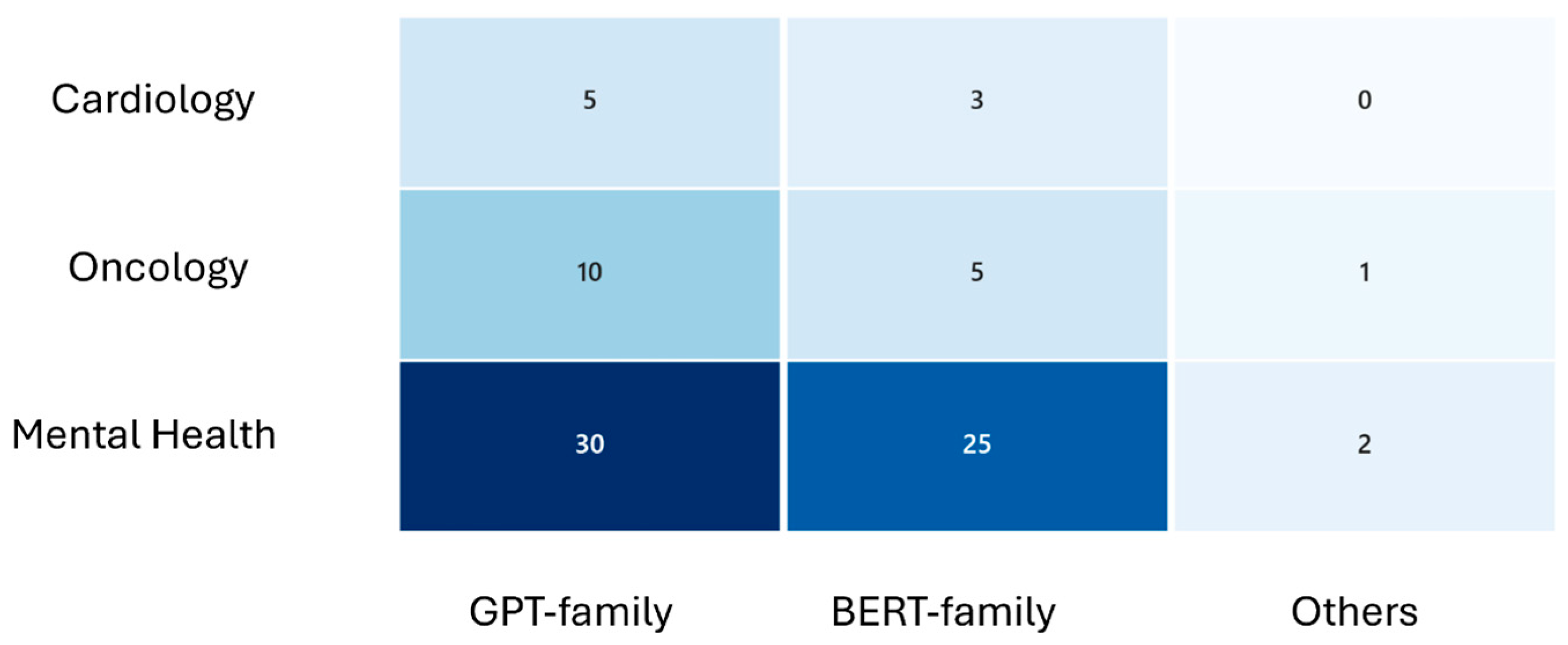

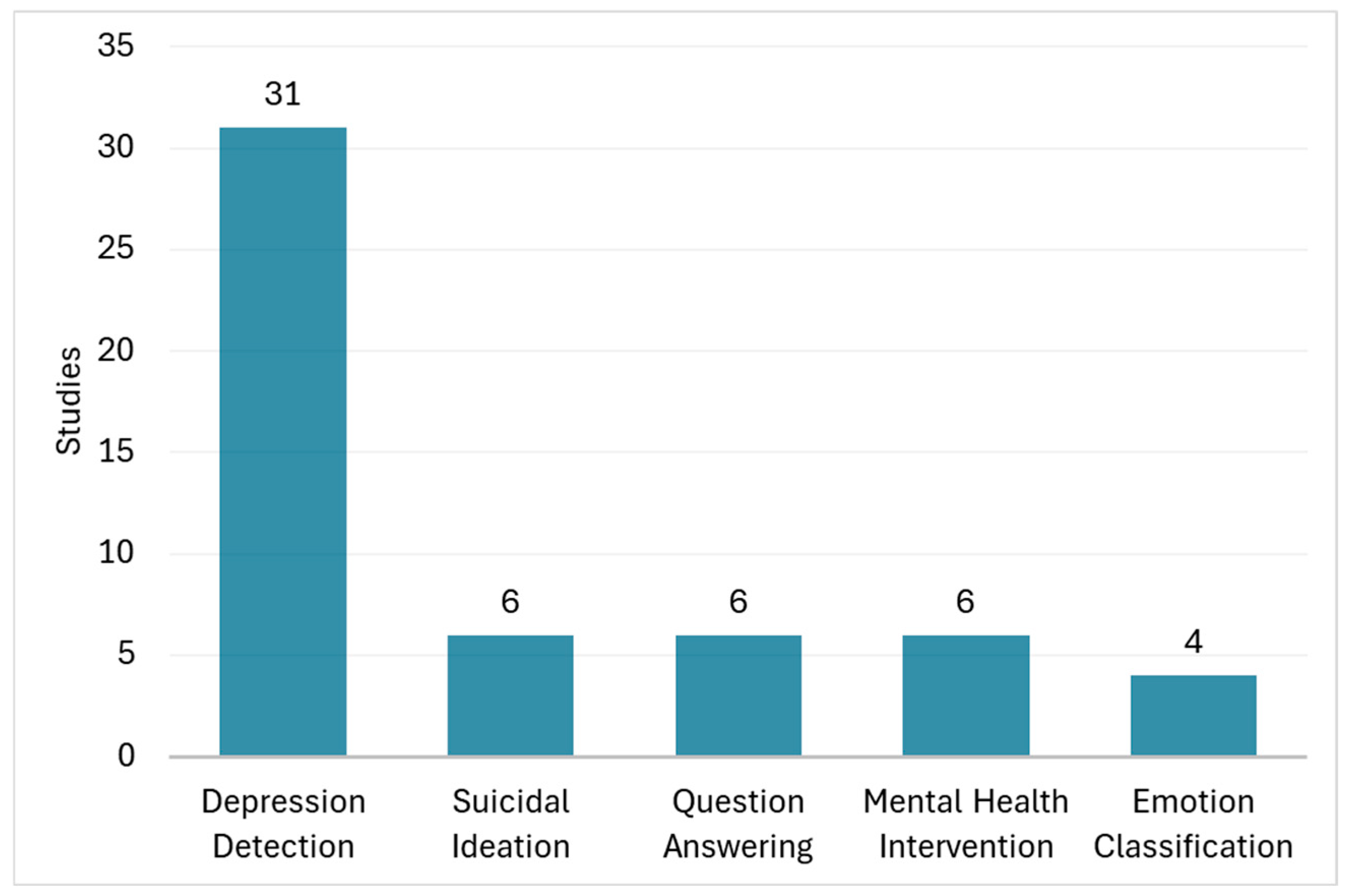

3.3. Characteristics of Individual Studies

3.4. Summary of LLMs Performance

3.5. Benefits of Using LLMs

3.5.1. Detection and Screening

3.5.2. Risk Assessment and Triage

3.5.3. Clinical Reasoning and Decision Support

3.5.4. Patient Education and Participation

3.5.5. Summary, Documentation, and Research Support

3.6. Challenges of Using LLMs

3.6.1. Accuracy, Safety, and Efficacy of LLMs in Real World Settings

3.6.2. Bias and Model Transparency

3.6.3. Data Privacy, Security, and Regulatory Challenges

3.6.4. Data Availability and Generalizability

3.6.5. Continuous Human Oversight and Ethical Governance Frameworks

3.6.6. Methodological Quality of LLM Studies

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Study | Target Disease | Application | LLM Used | Data Sources | Accuracy | Key Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kusunose et al. [42] | CVD | Question-answering based on Japanese Hypertension guidelines | GPT 3.5 | Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension | 64.50% | ChatGPT performed well on clinical questions, performance on hypertension treatment guidelines topics was less satisfactory |

| Rizwan et al. [43] | CVD | Question-answering on treatment and management plans | GPT 4.0 | Hypothetical questions simulating clinical consultation | N/A | Out of the 10 clinical scenarios inserted in ChatGPT, eight were perfectly diagnosed |

| Skalidis et al. [44] | CVD | Ability in European Cardiology exams | GPT (Version N/A) | Exam questions from the ESC website, StudyPRN and Braunwald’s Heart Disease Review and Assessment | 58.80% | Results demonstrate that ChatGPT succeeds in the European Cardiology exams |

| Van Bulck et al. [45] | CVD | Question-answering on common cardiovascular diseases | GPT (Version N/A) | Virtual patient questions | N/A | Experts considered ChatGPT-generated responses trustworthy and valuable, with few considering them dangerous. Forty percent of the experts found ChatGPT responses more valuable than Google |

| Williams et al. [46] | CVD | Question-answering on cardiovascular computed tomography | GPT 3.5 | Questions from the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography 2023 program as well as questions about high risk plaque (HRP), quantitative plaque analysis, and how AI will transform cardiovascular CT | N/A | The answers to debate questions were plausible and provided reasonable summaries of the key debate points |

| Choi et al. [47] | Breast Cancer | Evaluation of the time and cost of developing prompts using LLMs, tailored to extract clinical factors in breast cancer patients | GPT 3.5 | Data from reports of surgical pathology and ultrasound from 2931 breast cancer patients who underwent radiotherapy from 2020 to 2022 | 87.70% | Developing and processing the prompts took 3.5 h and 15 min, respectively. Utilizing the ChatGPT application programming interface cost US $65.8 and when factoring in the estimated wage, the total cost was US $95.4 |

| Griewing et al. [48] | Breast Cancer | Concordance to tumor board clinical decisions | GPT 3.5 | Fictious patient data with clinical and diagnostic data | 50−95% | ChatGPT 3.5 can provide treatment recommendations for breast cancer patients that are consistent with multidisciplinary tumor board decision making of a gynecologic oncology center in Germany |

| Haver et al. [49] | Breast Cancer | Question-answering on breast cancer prevention and screening | GPT 3.5 | 25 questions addressing fundamental concepts related to breast cancer prevention and screening | 88% | ChatGPT provided appropriate responses for most questions posed about breast cancer prevention and screening, as assessed by fellowship-trained breast radiologists |

| Lukac et al. [50] | Breast Cancer | Tumor board clinical decision support | GPT 3.5 | Tumor characteristics and age of the 10 consecutive pretreatment patient cases | 64.20% | ChatGPT provided mostly general answers based on inputs, generally in agreement with the decision of MDT |

| Rao et al. [51] | Breast Cancer | Question-answering based on American Collegy of Radilology recommendations | GPT 4.0, GPT 3.5 | Prompting mechanisms and clinical presentations based on American College of Radiology | 88.9−98.4% | ChatGPT displays impressive accuracy in identifying appropriateness of common imaging modalities for breast cancer screening and breast pain |

| Sorin et al. [52] | Breast Cancer | Tumor board clinical decision support | GPT 3.5 | Clinical and diagnostic data of 10 patients | 70% | Chatbot’s clinical recommendations were in-line with those of the tumor board in 70% of cases |

| Abilkaiyrkyzy et al. [53] | Mental Disease | Mental illness detection using a chatbot | BERT | 219 E-DAIC participants | 69% | Chatbot effectively detects and classifies mental health issues, highly usable for reducing barriers to mental health care |

| Adarsh et al. [54] | Mental Disease | Depression sign detection using BERT | BERT-small | Social media texts | 63.60% | Enhanced BERT model accurately classifies depression severity from social media texts, understanding nuances better than others |

| Alessa and Al-Khalifa [55] | Mental Disease | Mental health interventions using CAs for the elderly supported by LLMs | ChatGPT, Google Cloud API | Record of interactions with CA; results of the human experts’ assessment | N/A | The proposed ChatGPT-based system effectively serves as a companion for elderly individuals, helping to alleviate loneliness and social isolation. Preliminary evaluations showed that the system could generate relevant responses tailored to elderly personas |

| Beredo and Ong [56] | Mental Disease | Mental health interventions using CAs supported by LLMs | EREN, MHBot, PERMA | Empatheticdialogues (24,850 conversations); Well-Being Conversations; Perma Lexica | N/A | This study successfully demonstrated a hybrid conversation model, which combines generative and retrieval approaches to improve language fluency and empathetic response generation in chatbots. This model, tested through both automated metrics and human evaluation, showed that the medium variation in the FTER model outperformed the vanilla DialoGPT in perplexity and that the human-likeness, relevance, and empathetic qualities of responses were significantly enhanced, making VHope a more competent CA with empathetic abilities |

| Berrezueta-Guzman et al. [57] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of the efficacy of ChatGPT in mental intensive treatment | ChatGPT | Evaluations from 10 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) therapy experts and interactions between therapists and the custom ChatGPT | N/A | This paper found that the custom ChatGPT demonstrated strong capabilities in engaging language use, maintaining interest, promoting active participation, and fostering a positive atmosphere in ADHD therapy sessions, with high ratings in communication and language. However, areas needing improvement were identified, particularly in confidentiality and privacy, cultural and sensory sensitivity, and handling nonverbal cues |

| Blease et al. [58] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of psychiatrists’ perceptions of the LLMs | ChatGPT, Bard, Bing AI | Survey responses from 138 APA members on LLM chatbot use in psychiatry | N/A | This paper found that over half of psychiatrists used AI tools like ChatGPT for clinical questions, with nearly 70% agreeing on improved documentation efficiency and almost 90% indicating a need for more training while expressing mixed opinions on patient care impacts and privacy concerns |

| Bokolo et al. [29] | Mental Disease | Depression detection from Twitter | RoBERTa, DeBERTa | 632,000 tweets | 97.48% | Transformer models like RoBERTa excel in depression detection from Twitter data, outperforming traditional ML approaches |

| Crasto et al. [59] | Mental Disease | Mental health interventions using CAs supported by LLMs | DialoGPT | Counselchat (includes tags of illness); question answers from 100 college students | N/A | The DialoGPT model, demonstrating higher perplexity and preferred by 63% of college participants for its human-like and empathetic responses, was chosen as the most suitable system for addressing student mental health issues |

| Dai et al. [24] | Mental Disease | Psychiatric patient screening | BERT, DistilBERT, ALBERT, ROBERTa | 500 EHRs | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.830 | BERT models, especially with feature dependency, effectively classify psychiatric conditions from EHRs |

| Danner et al. [60] | Mental Disease | Detecting depression using LLMs through clinical interviews | BERT; GPT 3.5, ChatGPT 4 | DAIC-WOZ; Extended-DAIC; simulated data | 78% | The study assessed the abilities of GPT-3.5-turbo and ChatGPT-4 on the DAIC-WOZ dataset, which yielded F1 scores of 0.78 and 0.61, respectively, and a custom BERT model, extended-trained on a larger dataset, which achieved an F1 score of 0.82 on the Extended-DAIC dataset, in recognizing depression in text |

| Dergaa et al. [61] | Mental Disease | Simulated mental health assessments and interventions with ChatGPT | GPT 3.5 | Fictional patient data; 3 scenarios | N/A | ChatGPT showed limitations in complex medical scenarios, underlining its unpreparedness for standalone use in mental health practice |

| Diniz et al. [62] | Mental Disease | Detecting suicidal ideation using LLMs through Twitter texts | BERT model for Portuguese, Multilingual BERT (base), BERTimbau | Non-clinical texts from tweets (user posts of the online social network Twitter) | 95% | The Boamente system demonstrated effective text analysis for suicidal ideation with high privacy standards and actionable insights for mental health professionals. The best-performing BERTimbau Large model (accuracy: 0.955; precision: 0.961; F-score: 0.954; AUC: 0.954) significantly excelled in detecting suicidal tendencies, showcasing robust accuracy and recall in model evaluations |

| D’Souza et al. [27] | Mental Disease | Responding to psychiatric case vignettes with diagnostic and management strategies | GPT 3.5 | Fictional patient data from clinical case vignettes; 100 cases | 61% | ChatGPT 3.5 showed high competence in handling psychiatric case vignettes, with strong diagnostic and management strategy generation |

| Elyoseph et al. [63] | Mental Disease | Evaluating emotional awareness compared to general population norms | GPT 3.5 | Fictional scenarios from the LEAS; 750 participants | 85% | ChatGPT showed higher emotional awareness compared to the general population and improved over time |

| Elyoseph et al. [64] | Mental Disease | Assessing suicide risk in fictional scenarios and comparing to professional evaluations | GPT 3.5 | Fictional patient data; text vignettescompared to 379 professionals | N/A | ChatGPT underestimated suicide risks compared to mental health professionals, indicating the need for human judgment in complex assessments |

| Elyoseph et al. [30] | Mental Disease | Evaluating prognosis in depression compared to other LLMs and professionals | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Fictional patient data; text vignettescompared to 379 professionals | N/A | ChatGPT 3.5 showed a more pessimistic prognosis in depression compared to other LLMs and mental health professionals |

| Esackimuthu et al. [65] | Mental Disease | Depression detection from social media text | ALBERT base v1 | ALBERT base v1 data | 50% | ALBERT shows potential in detecting depression signs from social media texts but faces challenges due to complex human emotions |

| Farhat et al. [66] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of ChatGPT as a complementary mental health resource | ChatGPT | Responses generated by ChatGPT | N/A | ChatGPT displayed significant inconsistencies and low reliability when providing mental health support for anxiety and depression, underlining the necessity of validation by medical professionals and cautious use in mental health contexts |

| Farruque et al. [67] | Mental Disease | Depression level detection modeling | Mental BERT (MBERT) | 13,387 Reddit samples | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.81 | MBERT enhanced with text excerpts significantly improves depression level classification from social media posts |

| Farruque et al. [68] | Mental Disease | Depression symptoms modeling from Twitter | BERT, Mental-BERT | 6077 tweets and 1500 annotated tweets | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.45 | Semi-supervised learning models, iteratively refined with Twitter data, improve depression symptom detection accuracy |

| Friedman and Ballentine [69] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of LLMs in data-driven discovery: correlating sentiment changes with psychoactive experiences | BERTowid, BERTiment | Erowid testimonials; drug receptor affinities; brain gene expression data; 58K annotated Reddit posts | N/A | This paper found that LLM methods can create unified and robust quantifications of subjective experiences across various psychoactive substances and timescales. The representations learned are evocative and mutually confirmatory, indicating significant potential for LLMs in characterizing psychoactivity |

| Ghanadian et al. [70] | Mental Disease | Suicidal ideation detection using LLMs through social media texts | ALBERT, DistilBERT, ChatGPT, Flan-T5, Llama | UMD Dataset; Synthetic Datasets (Generated using LLMs like Flan-T5 and Llama2, these datasets augment the UMD dataset to enhance model performance) | 87% | The synthetic data-driven method achieved consistent F1-scores of 0.82, comparable to real-world data models yielding F1-scores between 0.75 and 0.87. When 30% of the real-world UMD dataset was combined with the synthetic data, the performance significantly improved, reaching an F1-score of 0.88 on the UMD test set. This result highlights the effectiveness of synthetic data in addressing data scarcity and enhancing model performance |

| Hadar- Shoval et al. [71] | Mental Disease | Differentiating emotional responses in BPD and SPD scenarios using mentalising abilities | GPT 3.5 | Fictional patient data (BPD and SPD scenarios); AI-generated data | N/A | ChatGPT effectively differentiated emotional responses in BPD and SPD scenarios, showing tailored mentalizing abilities |

| Hayati et al. [72] | Mental Disease | Detecting depression by Malay dialect speech using LLMs | GPT 3 | Interviews with 53 adults fluent in Kuala Lumpur (KL), Pahang, or Terengganu Malay dialects | 73% | GPT-3 was tested on three different dialectal Malay datasets (combined, KL, and non-KL). It performed best on the KL dataset with a max_example value of 10, which achieved the highest overall performance. Despite the promising results, the non-KL dataset showed the lowest performance, suggesting that larger or more homogeneous datasets might be necessary for improved accuracy in depression detection tasks |

| He et al. [73] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of CAs handling counseling for people with autism supported by LLMs | ChatGPT | Public available data from the web-based medical consultation platform DXY | N/A | The study found that 46.86% of assessors preferred responses from physicians, 34.87% favored ChatGPT, and 18.27% favored ERNIE Bot. Physicians and ChatGPT showed higher accuracy and usefulness compared to ERNIE Bot, while ChatGPT outperformed both in empathy. The study concluded that while physicians’ responses were generally superior, LLMs like ChatGPT can provide valuable guidance and greater empathy, though further optimization and research are needed for clinical integration |

| Hegde et al. [74] | Mental Disease | Depression detection using supervised learning | Ensemble of ML classifiers, BERT | Social media text data | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.479 | BERT-based Transfer Learning model outperforms traditional ML classifiers in detecting depression from social media texts |

| Heston T.F. et al. [75] | Mental Disease | Simulating depression scenarios and evaluating AI’s responses | GPT 3.5 | Fictional patient data; 25 conversational agents | N/A | ChatGPT-3.5 conversational agents recommended human support at critical points, highlighting the need for AI safety in mental health |

| Hond et al. [76] | Mental Disease | Early depression risk detection in cancer patients | BERT | 16,159 cancer patients’ EHR data | Accuracy not reported, AUROC 0.74 | Machine learning models predict depression risk in cancer patients using EHRs, with structured data models performing best |

| Howard et al. [77] | Mental Disease | Detecting suicidal ideation using LLMs through social media texts | DeepMoji, Universal Sentence Encoder, GPT 1 | 1588 labeled posts from the Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology 2017 shared task | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.414 | The top-performing system, utilizing features derived from the GPT-1 model fine-tuned on over 150,000 unlabeled Reachout.com posts, achieved a new state-of-the-art macro-averaged F1 score of 0.572 on the CLPsych 2017 task without relying on metadata or preceding posts. However, error analysis indicated that this system frequently misses expressions of hopelessness |

| Hwang et al. [78] | Mental Disease | Generating psychodynamic formulations in psychiatry based on patient history | GPT 4 | Fictional patient data from published psychoanalytic literature; 1 detailed case | N/A | GPT-4 successfully created relevant and accurate psychodynamic formulations based on patient history |

| Ilias et al. [79] | Mental Disease | Stress and depression identification in social media | BERT, MentalBERT | Public datasets | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.73 | Extra-linguistic features improve calibration and performance of models in detecting stress and depression from texts |

| Janatdoust et al. [80] | Mental Disease | Depression signs detection from social media text | Ensemble of BERT, ALBERT, DistilBERT, RoBERTa | 16,632 social media comments | 61% | Ensemble models effectively classify depression signs from social media, utilizing multiple language models for improved accuracy |

| Kabir et al. [81] | Mental Disease | Depression severity detection from tweets | BERT, DistilBERT | 40,191 tweets | Accuracy not reported, AUROC 0.74–0.86 | Models effectively classify social media texts into depression severity categories, with high confidence and accuracy |

| Kumar et al. [82] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of GPT 3 in mental health intervention | GPT 3 | 209 participants responses, with 189 valid responses after filtering | N/A | This paper found that interaction with either of the chatbots improved participants’ intent to practice mindfulness again, while the tutorial video enhanced their overall experience of the exercise. These findings highlighted the potential promise and outlined directions for exploring the use of LLM-based chatbots for awareness-related interventions |

| Lam et al. [83] | Mental Disease | Multi-modal depression detection | Transformer, 1D CNN | 189 DAIC-WOZ participants | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.87 | Multi-modal models combining text and audio data effectively detect depression, enhanced by data augmentation |

| Lau et al. [28] | Mental Disease | Depression severity assessment | Prefix-tuned LLM | 189 clinical interview transcripts | Accuracy not reported, RMSE 4.67 | LLMs with prefix-tuning significantly enhance depression severity assessment, surpassing traditional methods |

| Levkovich and Elyoseph [31] | Mental Disease | Diagnosing and treating depression, comparing GPT models with primary care physicians | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Fictional patient data from clinical case vignettes; repeated multiple times for consistency | N/A | ChatGPT aligned with guidelines for depression management, contrasting with primary care physicians and showing no gender or socioeconomic biases |

| Levkovich and Elyoseph [32] | Mental Disease | Evaluating suicide risk assessments by GPT models and mental health professionals | GPT 3.5, GPT 4 | Fictional patient data; text vignettes compared to 379 professionals | N/A | GPT 4’s evaluations of suicide risk were similar to mental health professionals, though with some overestimations and underestimations |

| Li et al. [84] | Mental Disease | Evaluating performance on psychiatric licensing exams and diagnostics | GPT 4, Bard and Llama-2 | Fictional patient data in exam and clinical scenario questions; 24 experienced psychiatrists | 69% | GPT 4 outperformed other models in psychiatric diagnostics, closely matching the capabilities of human psychiatrists |

| Liyanage et al. [85] | Mental Disease | Data augmentation for wellness dimension classification in Reddit posts | GPT 3.5 | Real patient data from Reddit posts; 3092 instances, post-augmentation 4376 records | 69% | ChatGPT models effectively augmented Reddit post data, significantly improving classification performance for wellness dimensions |

| Lossio-Ventura et al. [26] | Mental Disease | Evaluations of LLMs for sentiment analysis through social media texts | ChatGPT;Open Pre-Trained Transformers (OPT) | NIH Data Set; Stanford Data Set | 86% | This paper revealed high variability and disagreement among sentiment analysis tools when applied to health-related survey data. OPT and ChatGPT demonstrated superior performance, outperforming all other tools. Moreover, ChatGPT outperformed OPT, achieving a 6% higher accuracy and a 4% to 7% higher F-measure |

| Lu et al. [86] | Mental Disease | Depression detection via conversation turn classification | BERT, transformer encoder | DAIC dataset | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.75 | Novel deep learning framework enhances depression detection from psychiatric interview data, improving interpretability |

| Ma et al. [87] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of mental health intervention CAs supported by LLMs | GPT 3 | 120 Reddit posts (2913 user comments) | N/A | The study highlighted that CAs like Replika, powered by LLMs, offered crucial mental health support by providing immediate, unbiased assistance and fostering self-discovery. However, they struggled with content filtering, consistency, user dependency, and social stigma, underscoring the importance of cautious use and improvement in mental wellness applications |

| Mazumdar et al. [88] | Mental Disease | Classifying mental health disorders and generating explanations | GPT 3, BERT-large, MentalBERT, ClinicBERT, and PsychBERT | Real patient data sourced from Reddit posts | 87% | GPT 3 outperformed other models in classifying mental health disorders and generating explanations, showing promise for AI-IoMT deployment |

| Metzler et al. [89] | Mental Disease | Detecting suicidal ideation using LLMs through Twitter texts | BERT, XLNet | 3202 English tweets | 88.50% | BERT achieved F1-scores of 0.93 for accurately labeling tweets as about suicide and 0.74 for off-topic tweets in the binary classification task. Its performance was similar to or exceeded human performance and matched that of state-of-the-art models on similar tasks |

| Owen et al. [90] | Mental Disease | Depression signal detection in Reddit posts | BERT, MentalBERT | Reddit datasets | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.64 | Effective identification of depressive signals in online forums, with potential for early intervention |

| Parker et al. [91] | Mental Disease | Providing information on bipolar disorder and generating creative content | GPT 3 | N/A | N/A | GPT-3 provided basic material on bipolar disorders and creative song generation, but lacked depth for scientific review |

| Perlis et al. [34] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of GPT 4 for clinical decision support in bipolar depression | GPT 4 turbo (gpt-4-1106-preview) | Recommendations generated by the augmented GPT-4 model and responses from clinicians treating bipolar disorder | 50.80% | This paper found that the augmented GPT 4 model had a Cohen’s kappa of 0.31 with expert consensus, identifying the optimal treatment in 50.8% of cases and placing it in the top 3 in 84.4% of cases. In contrast, the base model had a Cohen’s kappa of 0.09 and identified the optimal treatment in 23.4% of cases, highlighting the enhanced performance of the augmented model in aligning with expert recommendations |

| Poświata and Perełkiewicz [92] | Mental Disease | Depression sign detection using RoBERTa | RoBERTa, DepRoBERTa | RoBERTa models’ data | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.583 | RoBERTa and DepRoBERTa ensemble excels in classifying depression signs, securing top performance in a competitive environment |

| Pourkeyvan et al. [25] | Mental Disease | Mental health disorder prediction from Twitter | BERT models from Hugging Face | 11,890,632 tweets and 553 bio-descriptions | 97% | Superior detection of depression symptoms from social media, demonstrating the efficacy of advanced NLP models |

| Sadeghi et al. [93] | Mental Disease | Detecting depression using LLMs through interviews | GPT 3.5-Turbo, RoBERTa | E-DAIC (219 participants) | N/A | The study achieved its lowest error rates, a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 3.65 on the dev set and 4.26 on the test set, by fine-tuning DepRoBERTa with a specific prompt, outperforming manual methods and highlighting the potential of automated text analysis for depression detection |

| Schubert et al. [94] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of LLMs’ performance on neurology board-style examinations | ChatGPT 3.5, ChatGPT 4.0 | A question bank from an educational company with 2036 questions that resemble neurology board questions | 85% | ChatGPT 4.0 excelled over ChatGPT 3.5, achieving 85.0% accuracy versus 66.8%. It surpassed human performance in specific areas and exhibited high confidence in responses. Longer questions tended to result in more incorrect answers for both models |

| Senn et al. [95] | Mental Disease | Depression classification from interviews | BERT, RoBERTa, DistilBERT | 189 clinical interviews | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.93 | Ensembles of BERT models enhance depression detection robustness in clinical interviews |

| Singh and Motlicek [96] | Mental Disease | Depression level classification using BERT, RoBERTa, XLNet | Ensemble of BERT, RoBERTa, XLNet | Ensemble of models | 54% | Ensemble model accurately classifies depression levels from social media text, ranking highly in competitive settings |

| Sivamanikandan S. et al. [97] | Mental Disease | Depression level classification | DistilBERT, RoBERTa, ALBERT | Social media posts | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.457 | Transformer models classify depression levels effectively, with RoBERTa achieving the best performance |

| Spallek et al. [98] | Mental Disease | Providing educational material on mental health and substance use | GPT-4 | Real-world queries from mental health and substance use portals; 10 queries | N/A | GPT 4’s outputs were substandard compared to expert materials in terms of depth and adherence to communication guidelines |

| Stigall et al. [99] | Mental Disease | Emotion classification using LLMs through social media texts | EmoBERTTiny | A collection of publicly available datasets hosted on Kaggle and Huggingface | 93.14% (sentiment analysis), 85.46% (emotion analysis) | EmoBERTTiny outperformed pre-trained and state-of-the-art models in all metrics and computational efficiency, achieving 93.14% accuracy in sentiment analysis and 85.48% in emotion classification. It processes a 256-token context window in 8.04 ms post-tokenization and 154.23 ms total processing speed |

| Suri et al. [100] | Mental Disease | Depressive tendencies detection using multimodal data | BERT | 5997 tweets | 97% | Multimodal BERT frameworks significantly enhance detection of depressive tendencies from complex social media data |

| Tao et al. [101] | Mental Disease | Detecting anxiety and depression using LLMs through dialogs in real-life scenarios | ChatGPT | Speech data from nine Q&A tasks related to daily activities (75 patients with anxiety and 64 patients with depression) | 67.62% | This paper introduced a virtual interaction framework using LLMs to mitigate negative psychological states. Analysis of Q&A dialogs demonstrated ChatGPT’s potential in identifying depression and anxiety. To enhance classification, four language features, including prosodic and speech rate, positively impacted classification |

| Tey et al. [102] | Mental Disease | Pre- and post-depressive detection from tweets | BERT, supplemented with emoji decoding | Over 3.5 million tweets | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.90 | Augmented BERT model classifies Twitter users into depressive categories, enhancing early depression detection |

| Toto et al. [103] | Mental Disease | Depression screening using audio and text | AudiBERT | 189 clinical interviews | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.92 | AudiBERT outperforms traditional and hybrid models in depression screening, utilizing multimodal data |

| Vajre et al. [104] | Mental Disease | Detecting mental health using LLMs through social media texts | PsychBERT | Twitter hashtags and Subreddit (6 domains: anxiety, mental health, suicide, etc) | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.63 | The study identified PsychBERT as the highest-performing model, achieving an F1 score of 0.98 in a binary classification task and 0.63 in a more challenging multi-class classification task, indicating its superiority in handling complex mental health-related data. Additionally, PsychBERT’s explainability was enhanced by using the Captum library, which confirmed its ability to accurately identify key phrases indicative of mental health issues |

| Verma et al. [105] | Mental Disease | Detecting depression using LLMs through textual data | RoBERTa | Mental health corpus | 96.86% | The study successfully used a RoBERTa-base model to detect depression with a high accuracy of 96.86%, showcasing the potential of AI in identifying mental health issues through linguistic analysis |

| Wan et al. [106] | Mental Disease | Family history identification in mood disorders | BERT–CNN | 12,006 admission notes | 97% | High accuracy in identifying family psychiatric history from EHRs, suggesting utility in understanding mood disorders |

| Wang et al. [107] | Mental Disease | Enhancing depression diagnosis and treatment through the use of LLMs | LLaMA-7B; ChatGLM-6B, Alpaca, LLMs + Knowledge | Chinese Incremental Pre-training Dataset | N/A | The study assessed LLMs’ performance in mental health, emphasizing safety, usability, and fluency and integrating mental health knowledge to improve model effectiveness, enabling more tailored dialogs for treatment while ensuring safety and usability |

| Wang et al. [33] | Mental Disease | Detecting depression using LLMs through microblogs | BERT, RoBERTa, XLNet | 13,993 microblogs collected from the Sina Weibo | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.424 | RoBERTa achieved the highest macro-averaged F1 score of 0.424 for depression classification, while BERT scored the highest micro-averaged F1 score of 0.856. Pretraining on an in-domain corpus improved model performance |

| Wei et al. [108] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of ChatGPT in psychiatry | ChatGPT | Theoretical analysis and literature reviews | N/A | The paper found ChatGPT useful in psychiatry, stressing ethical use and human oversight, while noting challenges in accuracy and bias, positioning AI as a supportive tool in care |

| Wu et al. [109] | Mental Disease | Expanding dataset of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) using LLMs | GPT 3.5 Turbo | E-DAIC (219 participants) | Accuracy not reported, F1 0.63 | This paper demonstrated that two novel text augmentation frameworks using LLMs significantly improved PTSD diagnosis by addressing data imbalances in NLP tasks. The zero-shot approach, which generated new standardized transcripts, achieved the highest performance improvements, while the few-shot approach, which rephrased existing training samples, also surpassed the original dataset’s efficacy |

| Yongsatianchot et al. [110] | Mental Disease | Evaluation of LLMs’ perception of emotion | Text-davinci-003, ChatGPT, GPT 4 | Responses from three OpenAI LLMs to the Stress and Coping Process Questionnaire | N/A | The study applied the SCPQ to three OpenAI LLMs—davinci-003, ChatGPT, and GPT 4—and found that while their responses aligned with human dynamics of appraisal and coping, they did not vary across key appraisal dimensions as predicted and differed significantly in response magnitude. Notably, all models reacted more negatively than humans to negative scenarios, potentially influenced by their training processes |

| Zhang et al. [111] | Mental Disease | Detecting depression trends using LLMs through Twitter texts | RoBERTa, XLNet | 2575 Twitter users with depression identified via tweets and profiles | 78.90% | This study developed a fusion model that accurately classified depression among Twitter users with 78.9% accuracy. It identified key linguistic and behavioral indicators of depression and demonstrated that depressive users responded to the pandemic later than controls. The findings suggest the model’s effectiveness in noninvasively monitoring mental health trends during major events like COVID-19 |

References

- Carchiolo, V.; Malgeri, M. Trends, Challenges, and Applications of Large Language Models in Healthcare: A Bibliometric and Scoping Review. Futur. Internet 2025, 17, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for Good? On Opportunities and Challenges of Large Language Models for Education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volkmer, S.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A.; Schwarz, E. Large Language Models in Psychiatry: Opportunities and Challenges. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 339, 116026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quer, G.; Topol, E.J. The Potential for Large Language Models to Transform Cardiovascular Medicine. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e767–e771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iannantuono, G.M.; Bracken-Clarke, D.; Floudas, C.S.; Roselli, M.; Gulley, J.L.; Karzai, F. Applications of Large Language Models in Cancer Care: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1268915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Brain, G.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Ayers, J.W.; Poliak, A.; Dredze, M.; Leas, E.C.; Zhu, Z.; Kelley, J.B.; Faix, D.J.; Goodman, A.M.; Longhurst, C.A.; Hogarth, M.; et al. Comparing Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Patient Questions Posted to a Public Social Media Forum. JAMA Intern. Med. 2023, 183, 589–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Veen, D.; Van Uden, C.; Blankemeier, L.; Delbrouck, J.B.; Aali, A.; Bluethgen, C.; Pareek, A.; Polacin, M.; Reis, E.P.; Seehofnerová, A.; et al. Adapted Large Language Models Can Outperform Medical Experts in Clinical Text Summarization. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 1134–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-Training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. arXiv 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, A.; PourNejatian, N.; Shin, H.C.; Smith, K.E.; Parisien, C.; Compas, C.; Martin, C.; Costa, A.B.; Flores, M.G.; et al. A Large Language Model for Electronic Health Records. Npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shool, S.; Adimi, S.; Saboori Amleshi, R.; Bitaraf, E.; Golpira, R.; Tara, M. A Systematic Review of Large Language Model (LLM) Evaluations in Clinical Medicine. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2025, 25, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, W.; Khoriba, G.; Maity, S.; Jyoti Saikia, M. Large Language Models in Healthcare and Medical Applications: A Review. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedi, S.; Liu, Y.; Orr-Ewing, L.; Dash, D.; Koyejo, S.; Callahan, A.; Fries, J.A.; Wornow, M.; Swaminathan, A.; Lehmann, L.S.; et al. Testing and Evaluation of Health Care Applications of Large Language Models: A Systematic Review. JAMA 2024, 333, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, T.P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.; Altman, D.G. Assessing Risk of Bias in Included Studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK; pp. 187–241. ISBN 9780470712184.

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, E.; Thelwall, M.; Haustein, S.; Larivière, V. Who Reads Research Articles? An Altmetrics Analysis of Mendeley User Categories. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2015, 66, 1832–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Medapalli, T.; Alexandrou, M.; Brilakis, E.; Prasad, A. Exploring the Role of ChatGPT in Cardiology: A Systematic Review of the Current Literature. Cureus 2024, 16, e58936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, V.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Artsi, Y.; Barash, Y.; Konen, E.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Klang, E. Utilizing Large Language Models in Breast Cancer Management: Systematic Review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 150, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, M.; Soffer, S.; Charney, A.W.; Landi, I.; Nadkarni, G.N.; Klang, E. Applications of Large Language Models in Psychiatry: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1422807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Lai, A.; Thygesen, J.H.; Farrington, J.; Keen, T.; Li, K. Large Language Models for Mental Health Applications: Systematic Review. JMIR Ment. Health 2024, 11, e57400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omar, M.; Levkovich, I. Exploring the Efficacy and Potential of Large Language Models for Depression: A Systematic Review. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 371, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.J.; Su, C.H.; Lee, Y.Q.; Zhang, Y.C.; Wang, C.K.; Kuo, C.J.; Wu, C.S. Deep Learning-Based Natural Language Processing for Screening Psychiatric Patients. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 11, 533949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourkeyvan, A.; Safa, R.; Sorourkhah, A. Harnessing the Power of Hugging Face Transformers for Predicting Mental Health Disorders in Social Networks. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 28025–28035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lossio-Ventura, J.A.; Weger, R.; Lee, A.Y.; Guinee, E.P.; Chung, J.; Atlas, L.; Linos, E.; Pereira, F. A Comparison of ChatGPT and Fine-Tuned Open Pre-Trained Transformers (OPT) Against Widely Used Sentiment Analysis Tools: Sentiment Analysis of COVID-19 Survey Data. JMIR Ment. Health 2024, 11, e50150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franco D’Souza, R.; Amanullah, S.; Mathew, M.; Surapaneni, K.M. Appraising the Performance of ChatGPT in Psychiatry Using 100 Clinical Case Vignettes. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 89, 103770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.; Zhu, X.; Chan, W.Y. Automatic Depression Severity Assessment with Deep Learning Using Parameter-Efficient Tuning. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1160291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokolo, B.G.; Liu, Q. Advanced Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning and Transformer Models for Depression and Suicide Detection in Social Media Texts. Electronics 2024, 13, 3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Levkovich, I.; Shinan-Altman, S. Assessing Prognosis in Depression: Comparing Perspectives of AI Models, Mental Health Professionals and the General Public. Fam. Med. Community Health 2024, 12, e002583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levkovich, I.; Elyoseph, Z. Identifying Depression and Its Determinants upon Initiating Treatment: ChatGPT versus Primary Care Physicians. Fam. Med. Community Health 2023, 11, e002391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levkovich, I.; Elyoseph, Z. Suicide Risk Assessments Through the Eyes of ChatGPT-3.5 Versus ChatGPT-4: Vignette Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2023, 10, e51232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Li, T.; Li, W.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Q.; Yan, J.; Tang, B. Depression Risk Prediction for Chinese Microblogs via Deep-Learning Methods: Content Analysis. JMIR Med. Inform. 2020, 8, e17958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlis, R.H.; Goldberg, J.F.; Ostacher, M.J.; Schneck, C.D. Clinical Decision Support for Bipolar Depression Using Large Language Models. Neuropsychopharmacology 2024, 49, 1412–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyam, A.N.; Wisniewski, H.; Halamka, J.D.; Kashavan, M.S.; Torous, J.B. Chatbots and Conversational Agents in Mental Health: A Review of the Psychiatric Landscape. Can. J. Psychiatry 2019, 64, 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.K.; Hussein, S.; Aziz, T.A.; Chakraborty, S.; Islam, M.R.; Dhama, K. The Power of ChatGPT in Revolutionizing Rural Healthcare Delivery. Health Sci. Rep. 2023, 6, e1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatziisaak, D.; Burri, P.; Sparn, M.; Hahnloser, D.; Steffen, T.; Bischofberger, S. Concordance of ChatGPT Artificial Intelligence Decision-Making in Colorectal Cancer Multidisciplinary Meetings: Retrospective Study. BJS Open 2025, 9, zraf040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, D.; Jackson, S.; Shanmugasundaram, R.; Seth, I.; Siu, A.; Ahmadi, N.; Kam, J.; Mehan, N.; Thanigasalam, R.; Jeffery, N.; et al. Evaluating the Efficacy of ChatGPT as a Patient Education Tool in Prostate Cancer: Multimetric Assessment. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e55939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracken, A.; Reilly, C.; Feeley, A.; Sheehan, E.; Merghani, K.; Feeley, I. Artificial Intelligence (AI)—Powered Documentation Systems in Healthcare: A Systematic Review. J. Med. Syst. 2025, 49, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, S.; Agarwal, A.; Singla, S. LLMs Will Always Hallucinate, and We Need to Live with This. In Intelligent Systems and Applications; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; Volume 1554, pp. 624–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Afroogh, S.; Xu, Y.; Phillips, C. Navigating LLM Ethics: Advancements, Challenges, and Future Directions. AI Ethics 2025, 5, 5795–5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusunose, K.; Kashima, S.; Sata, M. Evaluation of the Accuracy of ChatGPT in Answering Clinical Questions on the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines. Circ. J. 2023, 87, 1030–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizwan, A.; Sadiq, T. The Use of AI in Diagnosing Diseases and Providing Management Plans: A Consultation on Cardiovascular Disorders with ChatGPT. Cureus 2023, 15, e43106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalidis, I.; Cagnina, A.; Luangphiphat, W.; Mahendiran, T.; Muller, O.; Abbe, E.; Fournier, S. ChatGPT Takes on the European Exam in Core Cardiology: An Artificial Intelligence Success Story? Eur. Heart J. Digit. Health 2023, 4, 279–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bulck, L.; Moons, P. What If Your Patient Switches from Dr. Google to Dr. ChatGPT? A Vignette-Based Survey of the Trustworthiness, Value, and Danger of ChatGPT-Generated Responses to Health Questions. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 2024, 23, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.C.; Shambrook, J. How Will Artificial Intelligence Transform Cardiovascular Computed Tomography? A Conversation with an AI Model. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2023, 17, 281–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, H.S.; Song, J.Y.; Shin, K.H.; Chang, J.H.; Jang, B.S. Developing Prompts from Large Language Model for Extracting Clinical Information from Pathology and Ultrasound Reports in Breast Cancer. Radiat. Oncol. J. 2023, 41, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griewing, S.; Gremke, N.; Wagner, U.; Lingenfelder, M.; Kuhn, S.; Boekhoff, J. Challenging ChatGPT 3.5 in Senology—An Assessment of Concordance with Breast Cancer Tumor Board Decision Making. J. Pers. Med. 2023, 13, 1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haver, H.L.; Ambinder, E.B.; Bahl, M.; Oluyemi, E.T.; Jeudy, J.; Yi, P.H. Appropriateness of Breast Cancer Prevention and Screening Recommendations Provided by ChatGPT. Radiology 2023, 307, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukac, S.; Dayan, D.; Fink, V.; Leinert, E.; Hartkopf, A.; Veselinovic, K.; Janni, W.; Rack, B.; Pfister, K.; Heitmeir, B.; et al. Evaluating ChatGPT as an Adjunct for the Multidisciplinary Tumor Board Decision-Making in Primary Breast Cancer Cases. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2023, 308, 1831–1844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, A.; Kim, J.; Kamineni, M.; Pang, M.; Lie, W.; Dreyer, K.J.; Succi, M.D. Evaluating GPT as an Adjunct for Radiologic Decision Making: GPT-4 Versus GPT-3.5 in a Breast Imaging Pilot. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 2023, 20, 990–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorin, V.; Klang, E.; Sklair-Levy, M.; Cohen, I.; Zippel, D.B.; Balint Lahat, N.; Konen, E.; Barash, Y. Large Language Model (ChatGPT) as a Support Tool for Breast Tumor Board. npj Breast Cancer 2023, 9, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abilkaiyrkyzy, A.; Laamarti, F.; Hamdi, M.; Saddik, A. El Dialogue System for Early Mental Illness Detection: Toward a Digital Twin Solution. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 2007–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adarsh, S.; Antony, B. SSN@LT-EDI-ACL2022: Transfer Learning Using BERT for Detecting Signs of Depression from Social Media Texts. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessa, A.; Al-Khalifa, H. Towards Designing a ChatGPT Conversational Companion for Elderly People. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on PErvasive Technologies Related to Assistive Environments, Corfu, Greece, 5–7 July 2023; pp. 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beredo, J.L.; Ong, E.C. A Hybrid Response Generation Model for an Empathetic Conversational Agent. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Asian Language Processing (IALP), Shenzhen, China, 27–28 October 2022; pp. 300–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrezueta-Guzman, S.; Kandil, M.; Martín-Ruiz, M.L.; Pau de la Cruz, I.; Krusche, S. Future of ADHD Care: Evaluating the Efficacy of ChatGPT in Therapy Enhancement. Healthcare 2024, 12, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blease, C.; Worthen, A.; Torous, J. Psychiatrists’ Experiences and Opinions of Generative Artificial Intelligence in Mental Healthcare: An Online Mixed Methods Survey. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 333, 115724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crasto, R.; Dias, L.; Miranda, D.; Kayande, D. CareBot: A Mental Health Chatbot. In Proceedings of the 2021 2nd International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET), Belgaum, India, 21–23 May 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danner, M.; Hadzic, B.; Gerhardt, S.; Ludwig, S.; Uslu, I.; Shao, P.; Weber, T.; Shiban, Y.; Rätsch, M. Advancing Mental Health Diagnostics: GPT-Based Method for Depression Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 62nd Annual Conference of the Society of Instrument and Control Engineers (SICE), Tsu, Japan, 6–9 September 2023; pp. 1290–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dergaa, I.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Hallit, S.; Loch, A.A.; Glenn, J.M.; Fessi, M.S.; Ben Aissa, M.; Souissi, N.; Guelmami, N.; Swed, S.; et al. ChatGPT Is Not Ready yet for Use in Providing Mental Health Assessment and Interventions. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1277756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diniz, E.J.S.; Fontenele, J.E.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Bastos, V.H.; Teixeira, S.; Rabêlo, R.L.; Calçada, D.B.; Dos Santos, R.M.; de Oliveira, A.K.; Teles, A.S. Boamente: A Natural Language Processing-Based Digital Phenotyping Tool for Smart Monitoring of Suicidal Ideation. Healthcare 2022, 10, 698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Hadar-Shoval, D.; Asraf, K.; Lvovsky, M. ChatGPT Outperforms Humans in Emotional Awareness Evaluations. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1199058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Levkovich, I. Beyond Human Expertise: The Promise and Limitations of ChatGPT in Suicide Risk Assessment. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1213141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esackimuthu, S.; Shruthi, H.; Sivanaiah, R.; Angel Deborah, S.; Sakaya Milton, R.; Mirnalinee, T.T. SSN_MLRG3 @LT-EDI-ACL2022-Depression Detection System from Social Media Text Using Transformer Models. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhat, F. ChatGPT as a Complementary Mental Health Resource: A Boon or a Bane. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2024, 52, 1111–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farruque, N.; Zaïane, O.R.; Goebel, R.; Sivapalan, S. DeepBlues@LT-EDI-ACL2022: Depression Level Detection Modelling through Domain Specific BERT and Short Text Depression Classifiers. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022; pp. 167–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farruque, N.; Goebel, R.; Sivapalan, S.; Zaïane, O.R. Depression Symptoms Modelling from Social Media Text: An LLM Driven Semi-Supervised Learning Approach. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2024, 58, 1013–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.F.; Ballentine, G. Trajectories of Sentiment in 11,816 Psychoactive Narratives. Hum. Psychopharmacol. Clin. Exp. 2024, 39, e2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghanadian, H.; Nejadgholi, I.; Al Osman, H. Socially Aware Synthetic Data Generation for Suicidal Ideation Detection Using Large Language Models. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 14350–14363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadar-Shoval, D.; Elyoseph, Z.; Lvovsky, M. The Plasticity of ChatGPT’s Mentalizing Abilities: Personalization for Personality Structures. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1234397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayati, M.F.M.; Ali, M.A.M.; Rosli, A.N.M. Depression Detection on Malay Dialects Using GPT-3. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE-EMBS Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Sciences (IECBES), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 7–9 December 2022; pp. 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, W.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xia, Q. Physician Versus Large Language Model Chatbot Responses to Web-Based Questions From Autistic Patients in Chinese: Cross-Sectional Comparative Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2024, 26, e54706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, A.; Coelho, S.; Dashti, A.E.; Shashirekha, H.L. MUCS@Text-LT-EDI@ACL 2022: Detecting Sign of Depression from Social Media Text Using Supervised Learning Approach. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heston, T.F. Safety of Large Language Models in Addressing Depression. Cureus 2023, 15, e50729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Hond, A.; van Buchem, M.; Fanconi, C.; Roy, M.; Blayney, D.; Kant, I.; Steyerberg, E.; Hernandez-Boussard, T. Predicting Depression Risk in Patients with Cancer Using Multimodal Data: Algorithm Development Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2024, 12, e51925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard, D.; Maslej, M.M.; Lee, J.; Ritchie, J.; Woollard, G.; French, L. Transfer Learning for Risk Classification of Social Media Posts: Model Evaluation Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e15371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G.; Lee, D.Y.; Seol, S.; Jung, J.; Choi, Y.; Her, E.S.; An, M.H.; Park, R.W. Assessing the Potential of ChatGPT for Psychodynamic Formulations in Psychiatry: An Exploratory Study. Psychiatry Res. 2024, 331, 115655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilias, L.; Mouzakitis, S.; Askounis, D. Calibration of Transformer-Based Models for Identifying Stress and Depression in Social Media. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2024, 11, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janatdoust, M.; Ehsani-Besheli, F.; Zeinali, H. KADO@LT-EDI-ACL2022: BERT-Based Ensembles for Detecting Signs of Depression from Social Media Text. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, M.; Ahmed, T.; Hasan, M.B.; Laskar, M.T.R.; Joarder, T.K.; Mahmud, H.; Hasan, K. DEPTWEET: A Typology for Social Media Texts to Detect Depression Severities. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2023, 139, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, J.; Musabirov, I.; Farb, N.A.S.; Williams, J.J. Exploring the Use of Large Language Models for Improving the Awareness of Mindfulness. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Hamburg, Germany, 23–28 April 2023; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, G.; Dongyan, H.; Lin, W. Context-Aware Deep Learning for Multi-Modal Depression Detection. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2019—2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK, 12–17 May 2019; pp. 3946–3950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.J.; Kao, Y.C.; Tsai, S.J.; Bai, Y.M.; Yeh, T.C.; Chu, C.S.; Hsu, C.W.; Cheng, S.W.; Hsu, T.W.; Liang, C.S.; et al. Comparing the Performance of ChatGPT GPT-4, Bard, and Llama-2 in the Taiwan Psychiatric Licensing Examination and in Differential Diagnosis with Multi-Center Psychiatrists. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2024, 78, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liyanage, C.; Garg, M.; Mago, V.; Sohn, S. Augmenting Reddit Posts to Determine Wellness Dimensions Impacting Mental Health. In Proceedings of the 22nd Workshop on Biomedical Natural Language Processing and BioNLP Shared Tasks, Toronto, ON, Canada, 13 July 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.C.; Thamrin, S.A.; Chen, A.L.P. Depression Detection via Conversation Turn Classification. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 39393–39413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Mei, Y.; Su, Z. Understanding the Benefits and Challenges of Using Large Language Model-Based Conversational Agents for Mental Well-Being Support. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2024, 2023, 1105–1114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mazumdar, H.; Chakraborty, C.; Sathvik, M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Panigrahi, P.K. GPTFX: A Novel GPT-3 Based Framework for Mental Health Detection and Explanations. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2023, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzler, H.; Baginski, H.; Niederkrotenthaler, T.; Garcia, D. Detecting Potentially Harmful and Protective Suicide-Related Content on Twitter: Machine Learning Approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e34705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, D.; Antypas, D.; Hassoulas, A.; Pardiñas, A.F.; Espinosa-Anke, L.; Collados, J.C. Enabling Early Health Care Intervention by Detecting Depression in Users of Web-Based Forums Using Language Models: Longitudinal Analysis and Evaluation. JMIR AI 2023, 2, e41205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, G.; Spoelma, M.J. A Chat about Bipolar Disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2024, 26, 249–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poswiata, R.; Perełkiewicz, M. OPI@LT-EDI-ACL2022: Detecting Signs of Depression from Social Media Text Using RoBERTa Pre-Trained Language Models. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022; Association for Computational Linguistics: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi, M.; Egger, B.; Agahi, R.; Richer, R.; Capito, K.; Rupp, L.H.; Schindler-Gmelch, L.; Berking, M.; Eskofier, B.M. Exploring the Capabilities of a Language Model-Only Approach for Depression Detection in Text Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 15–18 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, M.C.; Wick, W.; Venkataramani, V. Performance of Large Language Models on a Neurology Board–Style Examination. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2346721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Senn, S.; Tlachac, M.L.; Flores, R.; Rundensteiner, E. Ensembles of BERT for Depression Classification. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC), Glasgow, UK, 11–15 July 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Volume 2022, pp. 4691–4694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Motlicek, P. IDIAP Submission@LT-EDI-ACL2022: Detecting Signs of Depression from Social Media Text. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivamanikandan, S.; Santhosh, V.; Sanjaykumar, N.; Jerin Mahibha, C.; Thenmozhi, D. ScubeMSEC@LT-EDI-ACL2022: Detection of Depression Using Transformer Models. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spallek, S.; Birrell, L.; Kershaw, S.; Devine, E.K.; Thornton, L. Can We Use ChatGPT for Mental Health and Substance Use Education? Examining Its Quality and Potential Harms. JMIR Med. Educ. 2023, 9, e51243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigall, W.; Al Hafiz Khan, M.A.; Attota, D.; Nweke, F.; Pei, Y. Large Language Models Performance Comparison of Emotion and Sentiment Classification. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM Southeast Conference, Marietta, GA, USA, 18–20 April 2024; pp. 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, M.; Semwal, N.; Chaudhary, D.; Gorton, I.; Kumar, B. I Don’t Feel so Good! Detecting Depressive Tendencies Using Transformer-Based Multimodal Frameworks. In Proceedings of the 2022 5th International Conference on Machine Learning and Natural Language Processing, Sanya, China, 23–25 December 2022; pp. 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Yang, M.; Shen, H.; Yang, Z.; Weng, Z.; Hu, B. Classifying Anxiety and Depression through LLMs Virtual Interactions: A Case Study with ChatGPT. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Istanbul, Turkey, 5–8 December 2023; pp. 2259–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tey, W.L.; Goh, H.N.; Lim, A.H.L.; Phang, C.K. Pre- and Post-Depressive Detection Using Deep Learning and Textual-Based Features. Int. J. Technol. 2023, 14, 1334–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toto, E.; Tlachac, M.L.; Rundensteiner, E.A. AudiBERT: A Deep Transfer Learning Multimodal Classification Framework for Depression Screening. In CIKM’21: Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual Event Queensland, Australia, 1–5 November 2021; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 4145–4154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vajre, V.; Naylor, M.; Kamath, U.; Shehu, A. PsychBERT: A Mental Health Language Model for Social Media Mental Health Behavioral Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM), Virtual, 9–12 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 1077–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Vishal; Joshi, R.C.; Dutta, M.K.; Jezek, S.; Burget, R. AI-Enhanced Mental Health Diagnosis: Leveraging Transformers for Early Detection of Depression Tendency in Textual Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 15th International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems and Workshops (ICUMT), Ghent, Belgium, 30 October–1 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Ge, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Yu, Y.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, H. Identification and Impact Analysis of Family History of Psychiatric Disorder in Mood Disorder Patients with Pretrained Language Model. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 861930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, K.; Wang, C. Knowledge-Enhanced Pre-Training Large Language Model for Depression Diagnosis and Treatment. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 9th International Conference on Cloud Computing and Intelligent Systems (CCIS), Dali, China, 12–13 August 2023; pp. 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Guo, L.; Lian, C.; Chen, J. ChatGPT: Opportunities, Risks and Priorities for Psychiatry. Asian J. Psychiatry 2023, 90, 103808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, J.; Mao, K.; Zhang, Y. Automatic Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis via Clinical Transcripts: A Novel Text Augmentation with Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 19–21 October 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongsatianchot, N.; Torshizi, P.G.; Marsella, S. Investigating Large Language Models’ Perception of Emotion Using Appraisal Theory. In Proceedings of the 2023 11th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction Workshops and Demos (ACIIW), Cambridge, MA, USA, 10–13 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lyu, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Luo, J. Monitoring Depression Trends on Twitter During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Observational Study. JMIR Infodemiology 2021, 1, e26769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AMSTAR 2 Criteria | Study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sharma et al. [19] | Sorin et al. [20] | Omar et al. [21] | Guo et al. [22] | Omar and Levkovich [23] | |

| 1. Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the components of PICO? | N | N | N | N | N |

| 2. Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol? | N | N | PY | PY | PY |

| 3. Did the review authors explain their selection of the study designs for inclusion in the review? | N | N | N | N | N |

| 4. Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy? | PY | N | PY | PY | PY |

| 5. Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 6. Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate? | Y | N | Y | Y | Y |

| 7. Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions? | N | PY | N | Y | PY |

| 8. Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail? | N | N | PY | PY | PY |

| 9. Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies that were included in the review? | N | Y | N | Y | Y |

| 10. Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review? | N | N | N | N | N |

| 11. Did the review authors account for RoB in individual studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review? | N | N | N | N | N |

| 12. Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 13. Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review? | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Category | Detailed Summary |

|---|---|

| Clinical Applications |

|

| |

| |

| Patient Engagement |

|

| |

| |

| Technical Challenges |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Ethical & Regulatory Issues |

|

| |

| |

| |

| Methodological Gaps |

|

| |

| |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Triantafyllidis, A.; Segkouli, S.; Kokkas, S.; Alexiadis, A.; Lithoxoidou, E.E.; Manias, G.; Antoniades, A.; Votis, K.; Tzovaras, D. Large Language Models for Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mental Disorders: A Review of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare 2026, 14, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010045

Triantafyllidis A, Segkouli S, Kokkas S, Alexiadis A, Lithoxoidou EE, Manias G, Antoniades A, Votis K, Tzovaras D. Large Language Models for Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mental Disorders: A Review of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare. 2026; 14(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleTriantafyllidis, Andreas, Sofia Segkouli, Stelios Kokkas, Anastasios Alexiadis, Evdoxia Eirini Lithoxoidou, George Manias, Athos Antoniades, Konstantinos Votis, and Dimitrios Tzovaras. 2026. "Large Language Models for Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mental Disorders: A Review of Systematic Reviews" Healthcare 14, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010045

APA StyleTriantafyllidis, A., Segkouli, S., Kokkas, S., Alexiadis, A., Lithoxoidou, E. E., Manias, G., Antoniades, A., Votis, K., & Tzovaras, D. (2026). Large Language Models for Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mental Disorders: A Review of Systematic Reviews. Healthcare, 14(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare14010045