Exploring the Pain Situation, Pain Impact, and Educational Preferences of Pain Among Adults in Mainland China, a Cross-Sectional Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Measures

2.3. Ethical Consideration

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Pain Situations

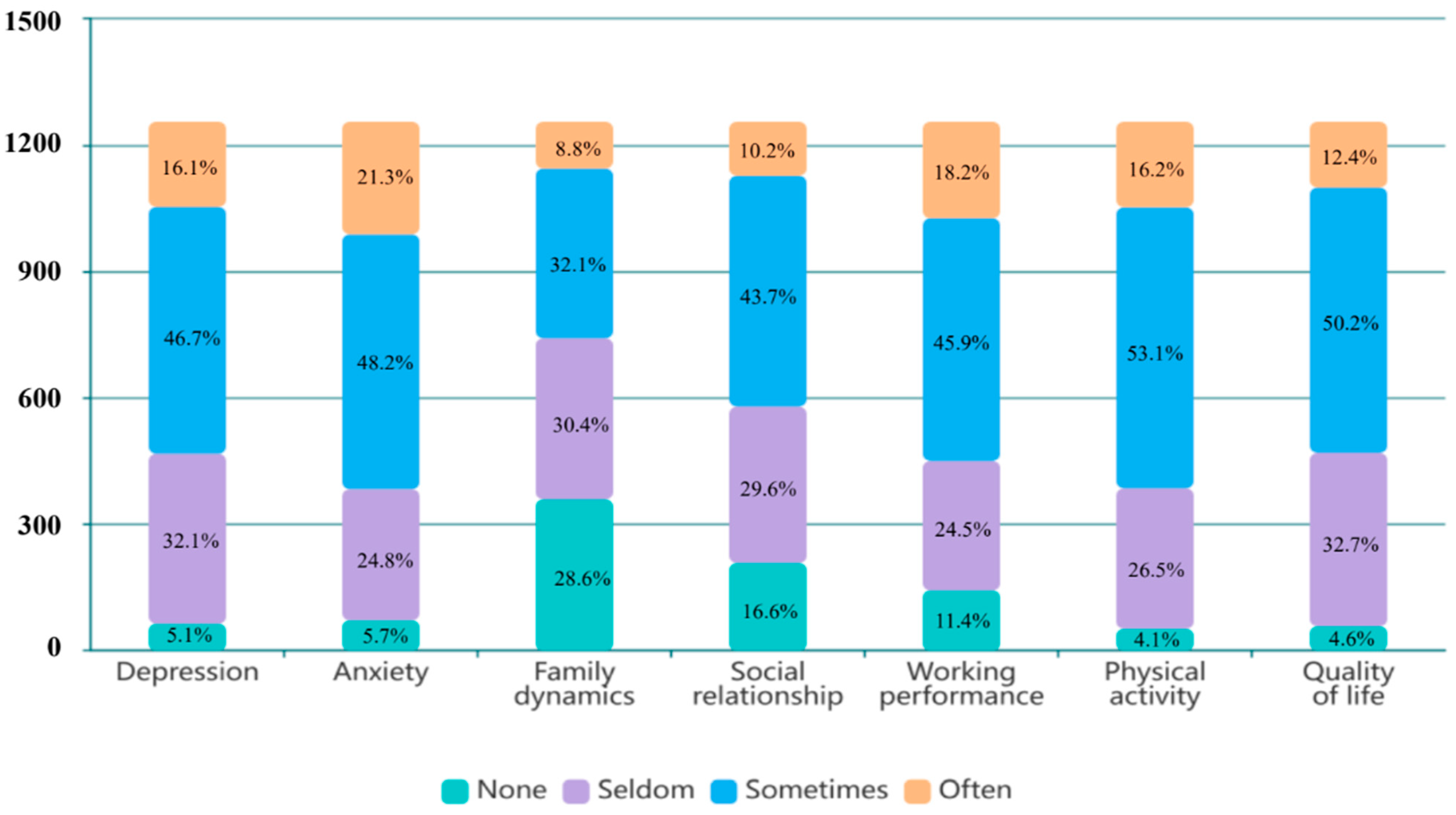

3.2. Psychological Impact of Pain

3.3. Physical and Functional Impact of Pain

3.4. Perceived Effectiveness of Pain Treatment and Care-Seeking Behaviours

3.5. Pain Education Preferences

4. Discussion

4.1. Pain Situations

4.2. Pain Impacts

4.3. Perceived Effectiveness of Pain Treatment and Care-Seeking Behaviours

4.4. Pain Education Preferences

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1789–1858, Erratum in: Lancet 2019, 393, e44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2017 Mortality Collaborators. Global regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality and life expectancy, 1950–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1684–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scholz, J.; Finnerup, N.B.; Attal, N.; Aziz, Q.; Baron, R.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Cruccu, G.; Davis, K.D.; et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic neuropathic pain. Pain 2019, 160, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadni, M.S.; You, D.S.; Cramer, E.M.; Anderson, S.R.; Hettie, G.; Darnall, B.D.; Mackey, S.C. The impact of COVID-19 on patients with chronic pain seeking care at a tertiary pain clinic. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 6435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Wu, X.; Shen, S.; Hong, W.; Qin, Y.; Sun, M.; Luan, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, B. Relationship between locomotive syndrome and musculoskeletal pain and generalized joint laxity in young Chinese adults. Healthcare 2023, 11, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Tse, M.M.Y. Pain situations among working adults and the educational needs identified: An exploratory survey via WeChat. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Li, B.; Liu, L.; Zhao, Y. Body pain intensity and interference in adults (45–53 years old): A cross-sectional survey in Chongqing, China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badarin, K.; Hemmingsson, T.; Hillert, L.; Kjellberg, K. The impact of musculoskeletal pain and strenuous work on self-reported physical work ability: A cohort study of Swedish men and women. Int. Arch. Occup. Environ. Health 2021, 95, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Rosa, J.S.; Brady, B.R.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Herder, K.E.; Wallace, J.S.; Padilla, A.R.; Vanderah, T.W. Co-occurrence of chronic pain and anxiety/depression symptoms in U.S. adults: Prevalence, functional impacts, and opportunities. Pain 2023, 165, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novick, D.; Shi, Q.; Yue, L.; Moneta, M.V.; Siddi, S.; Haro, J.M. Impact of pain and remission in the functioning of patients with depression in Mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 2017, 10, e12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yongjun, Z.; Tingjie, Z.; Xiaoqiu, Y.; Zhiying, F.; Feng, Q.; Guangke, X.; Jinfeng, L.; Fachuan, N.; Xiaohong, J.; Yanqing, L. A survey of chronic pain in China. Libyan J. Med. 2020, 15, 1730550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, M.; Dong, D.; Lo, H.H.-M.; Wong, S.Y.-S.; Mo, P.K.-H.; Sit, R.W.-S. Patient preferences in the treatment of chronic musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review of discrete choice experiments. Pain 2022, 164, 675–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Guzman, J.; van Tulder, M.W. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2015, 350, h444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martorella, G.; Boitor, M.; Berube, M.; Fredericks, S.; Le May, S.; Gélinas, C. Tailored web-based interventions for pain: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, M.; Verret, M.; Martorella, G.; Bourque, L.; Déry, M.-P.; Hudon, A.; Singer, L.N.; Richard-Denis, A.; Ouellet, S.; Côté, C.; et al. Educational needs and preferences of adult patients with acute or chronic pain: A mixed methods systematic review protocol. JBI Évid. Synth. 2023, 21, 2092–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucinski, K.; Cook, J.L. Effects of preoperative opioid education on postoperative opioid use and pain management in orthopaedics: A systematic review. J. Orthop. 2020, 20, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, J.; Patton, R.A.; Park, I. Comparing perceptions of addiction treatment between professionals and individuals in recovery. Subst. Use Misuse 2022, 57, 983–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leake, H.B.; Moseley, G.L.; Stanton, T.R.; O’hagan, E.T.; Heathcote, L.C. What do patients value learning about pain? A mixed-methods survey on the relevance of target concepts after pain science education. Pain 2021, 162, 2558–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R.; Robinson, V.; Elliott-Button, H.L.; Watson, J.A.; Ryan, C.G.; Martin, D.J. Pain reconceptualisation after pain neurophysiology education in adults with chronic low back pain: A qualitative study. Pain Res. Manag. 2018, 2018, 3745651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenjuanxing (Questionnaire Star). Available online: https://www.wjx.cn (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Charan, J.; Biswas, T. How to calculate sample size for different study designs in medical research? Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2013, 35, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.K.; Tse, M.M.Y.; Leung, S.F.; Fotis, T. Acute and chronic musculoskeletal pain situations among the working population and their pain education needs: An exploratory study. Fam. Pract. 2020, 37, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- China Internet Network Information Center. The 53rd Statistical Report on China’s Internet Development; China Internet Network Information Center: Beijing, China, 2024; Available online: https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/ReportDownloads/202405/P020240509518443205347.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Kishore, K.; Jaswal, V.; Kulkarni, V.; De, D. Practical guidelines to develop and evaluate a questionnaire. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 12, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.; Tang, C.; Peng, P.; Wen, X.; Tang, S. Prevalence and influencing factors of chronic pain in middle-aged and older adults in China: Results of a nationally representative survey. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1110216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, D. Characteristics of Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders in Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, K.; Fujii, T.; Kubota, Y.; Ikeda, T.; Hanazato, M.; Kondo, N.; Matsudaira, K.; Kondo, K. Prevalence and municipal variation in chronic musculoskeletal pain among independent older people: Data from the Japan Gerontological Evaluation Study (JAGES). BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2133–2161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corp, N.; Mansell, G.; Stynes, S.; Wynne-Jones, G.; Morsø, L.; Hill, J.C.; van der Windt, D.A. Evidence-based treatment recommendations for neck and low back pain across Europe: A systematic review of guidelines. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 25, 275–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.P.; Hooten, W.M. Advances in the diagnosis and management of neck pain. BMJ 2017, 358, j3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooleri, A.; Yeduri, R.; Horne, G.; Frech, A.; Tumin, D. Pain interference in young adulthood and work participation. Pain 2023, 164, 705–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, S.; Waterfield, J. Cultural aspects of pain: A study of Indian Asian women in the UK. Musculoskelet. Care 2018, 16, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perugino, F.; De Angelis, V.; Pompili, M.; Martelletti, P. Stigma and chronic pain. Pain Ther. 2022, 11, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Sherwood, G.D.; Liang, S.; Gong, Z.; Ren, L.; Liu, H.; Van, I.K. Comparison of postoperative pain management outcomes in the United States and China. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewis, G.N.; Shaikh, N.; Wang, G.; Chaudhary, S.; Bean, D.J.; Terry, G. Chinese and Indian interpretations of pain: A qualitative evidence synthesis to facilitate chronic pain management. Pain Pract. 2023, 23, 647–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Chen, H.; Luo, C.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Wu, D.; Cheng, H. Storage, disposal, and use of opioids among cancer patients in Central China: A multi-center cross-sectional study. Oncologist 2024, 29, e941–e948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NICE. Chronic Pain (Primary and Secondary) in over 16s: Assessment of All Chronic Pain and Management of Chronic Primary Pain; NICE Guidelines; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE): London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Busse, J.W.; Craigie, S.; Juurlink, D.N.; Buckley, D.N.; Wang, L.; Couban, R.J.; Agoritsas, T.; Akl, E.A.; Carrasco-Labra, A.; Cooper, L.; et al. Guideline for opioid therapy and chronic noncancer pain. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2017, 189, E659–E666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, W.-C.; Li, Z. Pain Beliefs and Behaviors Among Chinese. Home Health Care Manag. Pract. 2014, 27, 95–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepri, B.; Romani, D.; Storari, L.; Barbari, V. Effectiveness of pain neuroscience education in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and central sensitization: A systematic review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medical Device Innovation Consortium. Medical Device Innovation Consortium (MDIC) Patient Centered Risk-Benefit Project Report; Medical Device Innovation Consortium: Arlington, VA, USA, 2015; Available online: https://mdic.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/MDIC_PCBR_Framework_Web1.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Xu, Y.; Jiang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, L.; Ma, S. Pain perception of older adults in nursing home and home care settings: Evidence from China. BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Méndez, J.; Núñez-Cortés, R.; Suso-Martí, L.; Ribeiro, I.L.; Garrido-Castillo, M.; Gacitúa, J.; Mendez-Rebolledo, G.; Cruz-Montecinos, C.; López-Bueno, R.; Calatayud, J. Dosage matters: Uncovering the optimal duration of pain neuroscience education to improve psychosocial variables in chronic musculoskeletal pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis with moderator analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 153, 105328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashton-James, C.E.; Anderson, S.R.; Mackey, S.C.; Darnall, B.D. Beyond pain, distress, and disability: The importance of social outcomes in pain management research and practice. Pain 2021, 163, e426–e431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, Y.; Yue, Y.; Sheng, Y. The mediating role of aging attitudes between social isolation and self-neglect: A cross-sectional study of older adults living alone in rural China. BMC Nurs. 2025, 24, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slater, H.B.; Jordan, J.E.B.; O’sullivan, P.B.D.P.; Schütze, R.B.; Goucke, R.M.; Chua, J.B.; Browne, A.B.; Horgan, B.; De Morgan, S.B.; Briggs, A.M.B. “Listen to me, learn from me”: A priority setting partnership for shaping interdisciplinary pain training to strengthen chronic pain care. Pain 2022, 163, e1145–e1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toye, F.; Belton, J.; Hannink, E.; Seers, K.; Barker, K. A healing journey with chronic pain: A meta-ethnography synthesizing 195 qualitative studies. Pain Med. 2021, 22, 1333–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquié, L.; Raufaste, E.; Lauque, D.; Mariné, C.; Ecoiffier, M.; Sorum, P. Pain rating by patients and physicians: Evidence of systematic pain miscalibration. Pain 2003, 102, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, K.; Henceroth, M.; Lu, Q.; LeRoy, A. Cultural differences in pain experience among four ethnic groups: A qualitative pilot study. J. Behav. Health 2016, 5, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholz, S.M.; Thalmann, N.F.; Müller, D.; Trippolini, M.A.; Wertli, M.M. Factors influencing pain medication and opioid use in patients with musculoskeletal injuries: A retrospective insurance claims database study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeybek, N.; Saygı, E. Gamification in Education: Why, Where, When, and How?—A Systematic Review. Games Cult. 2023, 19, 237–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Scott, K.; Dukewich, M. Innovative technology using virtual reality in the treatment of pain: Does it reduce pain via distraction, or is there more to it? Pain Med. 2017, 19, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, H.; Wang, C.; Jin, Y.; Tian, X.; Qiao, X.; Liu, N.; Dong, L. Prevalence, Factors, and Health Impacts of Chronic Pain Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults in China. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2019, 20, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Total (n = 1566) | Non-Pain Group (n = 311, 19.9%) | Pain Group | p-Values a | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 1255, 80.1%) | Acute Pain (n = 381, 30.4%) | Chronic Pain (n = 873, 69.6%) | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Gender | 0.004 | ||||||||||

| Male | 951 | 60.7 | 182 | 11.6% | 769 | 49.1% | 211 | 13.5% | 558 | 35.6% | |

| Female | 615 | 39.3 | 129 | 8.2% | 486 | 31.0% | 171 | 10.9% | 315 | 20.1% | |

| Age | |||||||||||

| Mean age | 30.24 (9.20) | 30.37 (10.59) | 30.21 (8.81) | 29.50 (8.17) | 30.52 (9.06) | 0.170 | |||||

| Marital status | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| Single | 697 | 44.5 | 175 | 11.2% | 522 | 33.3% | 199 | 12.7% | 323 | 20.6% | |

| Married | 843 | 53.8 | 130 | 8.3% | 713 | 45.5% | 177 | 11.3% | 536 | 34.2% | |

| Divorced/Widowed | 26 | 1.7 | 6 | 0.4% | 20 | 1.3% | 6 | 0.4% | 14 | 0.9% | |

| Occupation type | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Managers and administrators | 88 | 5.6 | 18 | 1.1% | 70 | 4.5% | 27 | 1.7% | 43 | 2.7% | |

| Professionals | 455 | 29.1 | 89 | 5.7% | 366 | 23.4% | 79 | 5.0% | 287 | 18.3% | |

| Clerical support workers | 391 | 25.0 | 73 | 4.7% | 318 | 20.3% | 114 | 7.3% | 204 | 13.0% | |

| Service and sale workers | 238 | 15.2 | 46 | 2.9% | 192 | 12.3% | 52 | 3.3% | 140 | 8.9% | |

| Craft and related workers | 96 | 6.1 | 22 | 1.4% | 74 | 4.7% | 28 | 1.8% | 46 | 2.9% | |

| Plant and machine operators and assemblers | 113 | 7.2 | 20 | 1.3% | 93 | 5.9% | 33 | 2.1% | 60 | 3.8% | |

| Elementary occupations | 107 | 6.8 | 26 | 1.7% | 81 | 5.2% | 26 | 1.7% | 55 | 3.5% | |

| Personnel in government | 78 | 5.0 | 17 | 1.1% | 61 | 3.9% | 23 | 1.5% | 38 | 2.4% | |

| Education level | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| Lower than senior secondary | 219 | 14.0 | 24 | 1.5% | 195 | 12.5% | 26 | 1.7% | 169 | 10.8% | |

| Senior secondary | 204 | 13.0 | 48 | 3.1% | 156 | 10.0% | 45 | 2.9% | 111 | 7.1% | |

| Bachelor | 988 | 63.1 | 188 | 12.0% | 800 | 51.1% | 270 | 17.2% | 530 | 33.8% | |

| Master and doctorate | 155 | 9.9 | 51 | 3.3% | 104 | 6.6% | 41 | 2.6% | 63 | 4.0% | |

| Resident area | 0.001 | ||||||||||

| Northeast China | 168 | 10.7 | 45 | 2.9% | 123 | 7.9% | 50 | 3.2% | 73 | 4.7% | |

| North China | 291 | 18.6 | 53 | 3.4% | 238 | 15.2% | 87 | 5.6% | 151 | 9.6% | |

| Northwest China | 138 | 8.8 | 23 | 1.5% | 115 | 7.3% | 32 | 2.0% | 83 | 5.3% | |

| Central China | 395 | 25.2 | 53 | 3.4% | 342 | 21.8% | 74 | 4.7% | 268 | 17.1% | |

| South China | 318 | 20.3 | 85 | 5.4% | 233 | 14.9% | 76 | 4.9% | 157 | 10.0% | |

| East China | 163 | 10.4 | 32 | 2.0% | 131 | 8.4% | 41 | 2.6% | 90 | 5.7% | |

| Southwest China | 93 | 5.9 | 20 | 1.3% | 73 | 4.7% | 22 | 1.4% | 51 | 3.3% | |

| Monthly DPI (RMB) | 0.000 | ||||||||||

| 3000 or below | 162 | 10.3 | 58 | 3.7% | 104 | 6.6% | 41 | 2.6% | 63 | 4.0% | |

| 3001–6000 | 356 | 22.7 | 81 | 5.2% | 275 | 17.6% | 106 | 6.8% | 169 | 10.8% | |

| 6001–10,000 | 501 | 32.0 | 82 | 5.2% | 419 | 26.8% | 130 | 8.3% | 289 | 18.5% | |

| 10,001–20,000 | 267 | 17.0 | 46 | 2.9% | 221 | 14.1% | 62 | 4.0% | 159 | 10.2% | |

| 20,001–30,000 | 101 | 6.4 | 30 | 1.9% | 71 | 4.5% | 20 | 1.3% | 51 | 3.3% | |

| 30,001–40,000 | 123 | 7.9 | 8 | 0.5% | 115 | 7.3% | 6 | 0.4% | 109 | 7.0% | |

| 40,001 or above | 56 | 3.6 | 6 | 0.4% | 50 | 3.2% | 17 | 1.1% | 33 | 2.1% | |

| Personal health history (multiple answers can be chosen) | |||||||||||

| No chronic illness | 621 | 39.7 | 208 | 13.3% | 413 | 26.4% | 177 | 11.3% | 236 | 15.1% | 0.000 |

| Hypertension | 206 | 13.2 | 31 | 2.0% | 175 | 11.2% | 40 | 2.6% | 135 | 8.6% | 0.019 |

| Diabetes | 167 | 10.7 | 26 | 1.7% | 141 | 9.0% | 32 | 2.0% | 109 | 7.0% | 0.034 |

| Heart disease | 129 | 8.2 | 18 | 1.1% | 111 | 7.1% | 23 | 1.5% | 88 | 5.6% | 0.020 |

| Stroke | 192 | 12.3 | 14 | 0.9% | 178 | 11.4% | 22 | 1.4% | 156 | 10.0% | 0.000 |

| Gout | 208 | 13.3 | 6 | 0.4% | 202 | 12.9% | 32 | 2.0% | 170 | 10.9% | 0.000 |

| Lung disease | 117 | 7.5 | 13 | 0.8% | 104 | 6.6% | 17 | 1.1% | 87 | 5.6% | 0.001 |

| Arthritis | 286 | 18.3 | 19 | 1.2% | 267 | 17.0% | 64 | 4.1% | 203 | 13.0% | 0.010 |

| Cataracts | 32 | 2.0 | 4 | 0.3% | 28 | 1.8% | 10 | 0.6% | 18 | 1.1% | 0.539 |

| Neurological disorders | 109 | 7.0 | 9 | 0.6% | 100 | 6.4% | 20 | 1.3% | 80 | 5.1% | 0.018 |

| Stomach disease | 307 | 19.6 | 40 | 2.6% | 267 | 17.0% | 81 | 5.2% | 186 | 11.9% | 0.968 |

| Other | 49 | 3.1 | 8 | 0.5% | 41 | 2.6% | 9 | 0.6% | 32 | 2.0% | 0.230 |

| Total (n = 1255) | Pain Group | p-Value a | |||||

| Acute Pain (n = 381, 24.4%) | Chronic Pain (n = 873, 55.7%) | ||||||

| M (SD) | Mdn (25%IQR) | M (SD) | Mdn (25%IQR) | M (SD) | Mdn (25%IQR) | ||

| Mood | 5.59 (1.40) | 6.00 (5.00) | 5.29 (1.50) | 5.00 (4.00) | 5.72 (1.33) | 6.00 (5.00) | 0.000 |

| Family dynamics | 2.21 (0.96) | 2.00 (1.00) | 2.03 (0.89) | 2.00 (1.00) | 2.29 (0.97) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.000 |

| Social relationship | 2.47 (0.89) | 3.00 (2.00) | 2.18 (0.87) | 2.00 (1.00) | 2.60 (0.86) | 3.00 (2.00) | 0.000 |

| Working performance | 2.71 (0.89) | 3.00 (2.00) | 2.50 (0.94) | 3.00 (2.00) | 2.80 (0.86) | 3.00 (2.00) | 0.000 |

| Physical activity | 2.81 (0,75) | 3.00 (2.00) | 2.64 (0.80) | 3.00 (2.00) | 2.89 (0.71) | 3.00 (3.00) | 0.000 |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | p-value b | |

| Impact of pain on family dynamics | |||||||

| Unable to take care of children | 307 | 24.5 | 83 | 21.7 | 224 | 25.7 | 0.033 |

| Unable to take care of the elderly | 414 | 33.0 | 109 | 28.5 | 305 | 34.9 | 0.019 |

| Family members cannot understand my pain | 553 | 44.1 | 141 | 36.9 | 412 | 47.2 | 0.002 |

| Unable to do housework | 473 | 37.7 | 125 | 32.7 | 348 | 39.9 | 0.017 |

| Impact of pain on social relationships | |||||||

| Do not want to leave the house and hang out with friends | 437 | 34.8 | 126 | 33.0 | 311 | 35.6 | 0.000 |

| Unwilling to share my suffering with others | 599 | 47.7 | 143 | 37.4 | 456 | 52.2 | 0.000 |

| Fear that I must leave due to sudden pain while meeting with others | 665 | 53.0 | 181 | 47.4 | 484 | 55.4 | 0.000 |

| Impact of pain on working performance | |||||||

| Cannot concentrate on my work | 655 | 52.2 | 209 | 54.7 | 446 | 51.1 | 0.000 |

| Working procrastination due to frequent hospital visits | 614 | 48.9 | 148 | 38.7 | 466 | 53.4 | 0.000 |

| Absenteeism | 457 | 36.4 | 118 | 30.9 | 339 | 38.8 | 0.000 |

| Lack of work competence | 481 | 38.3 | 137 | 35.9 | 344 | 39.4 | 0.000 |

| Total (n = 1255) | Pain Group | p-Values a | |||||

| Acute Pain (n = 381, 24.4%) | Chronic Pain (n = 873, 55.7%) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Analgesics used | 0.000 | ||||||

| Yes | 840 | 66.9 | 201 | 52.6 | 639 | 73.2 | |

| No | 415 | 33.1 | 181 | 47.4 | 234 | 26.8 | |

| n | % | M (SD) | Mdn (25%IQR) | M (SD) | Mdn (25%IQR) | p-values b | |

| Non-pharmacological interventions used | |||||||

| Bed rest | 1184 | 94.3 | 1.39 (0.98) | 1.00 (1.00) | 1.36 (0.91) | 1.00 (1.00) | 0.698 |

| Massage | 1166 | 92.9 | 1.57 (0.95) | 2.00 (1.00) | 1.66 (0.94) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.243 |

| Deep breathing | 1094 | 87.2 | 1.15 (0.97) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.20 (0.97) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.563 |

| Exercise | 1027 | 81.8 | 1.20 (0.99) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.35 (1.05) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.033 |

| Hot compress | 1002 | 79.8 | 1.47 (0.98) | 2.00 (1.00) | 1.48 (1.00) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.947 |

| Analgesic balm/oil | 1019 | 81.2 | 1.38 (1.06) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.56 (1.06) | 2.00 (1.00) | 0.027 |

| Recreation | 1000 | 79.7 | 0.91 (0.96) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.13 (1.08) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.003 |

| Talking to others | 1013 | 80.7 | 0.83 (0.86) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.92 (0.90) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.124 |

| Listening to music | 1010 | 80.5 | 0.94 (0.98) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.93 (1.00) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.839 |

| Cold compress | 956 | 76.2 | 1.04 (0.97) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.09 (0.97) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.464 |

| Acupuncture | 908 | 72.4 | 1.09 (1.11) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.29 (1.08) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.003 |

| Nerve stimulation therapy | 843 | 67.2 | 0.98 (1.14) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.26 (1.09) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.000 |

| Aromatherapy | 795 | 63.3 | 0.71 (0.98) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.84 (1.04) | 0.00 (0.00) | 0.042 |

| Psychotherapy | 851 | 67.8 | 0.99 (1.06) | 1.00 (0.00) | 1.21 (1.16) | 1.00 (0.00) | 0.004 |

| Total (n = 1255) | Pain Group | p-Value a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Pain (n = 381, 24.4%) | Chronic Pain (n = 873, 55.7%) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sources of pain information acquisition | |||||||

| No idea | 304 | 24.2 | 294 | 77.0 | 216 | 24.7 | 0.516 |

| Websites | 618 | 49.2 | 201 | 52.6 | 417 | 47.8 | 0.114 |

| Mobile applications | 684 | 54.5 | 213 | 55.8 | 471 | 54.0 | 0.554 |

| Medical staff | 592 | 47.2 | 182 | 47.6 | 410 | 47.0 | 0.824 |

| Friends | 492 | 39.2 | 118 | 30.9 | 374 | 42.8 | 0.000 |

| Posters | 170 | 13.5 | 32 | 8.4 | 138 | 15.8 | 0.000 |

| Newspaper/magazine | 104 | 8.3 | 23 | 6.0 | 81 | 9.3 | 0.054 |

| Internet usage for pain-related purposes | |||||||

| Chronic pain information search | 674 | 53.7 | 207 | 54.2 | 467 | 53.5 | 0.820 |

| Pain treatment search | 792 | 63.1 | 224 | 58.6 | 568 | 65.1 | 0.030 |

| Therapists | 444 | 35.4 | 136 | 35.6 | 308 | 35.3 | 0.913 |

| Entertainment for distraction | 429 | 34.2 | 123 | 32.2 | 306 | 35.1 | 0.327 |

| Contacting peer patients | 337 | 26.9 | 80 | 20.9 | 257 | 29.4 | 0.002 |

| Contacting support group | 233 | 18.6 | 32 | 8.4 | 201 | 23.0 | 0.000 |

| Relaxation training | 189 | 15.1 | 57 | 14.9 | 132 | 15.1 | 0.928 |

| Total (n = 1255) | Pain Group a | p-Value a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute Pain (n = 381, 24.4%) | Chronic Pain (n = 873, 55.7%) | ||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Received pain education before | 0.000 | ||||||

| Yes | 39 | 3.1 | 4 | 1.0 | 35 | 4.0 | |

| No | 1216 | 96.9 | 378 | 99.0 | 838 | 96.0 | |

| Willingness to participate in online pain education interventions | 0.016 | ||||||

| Yes | 1172 | 93.4 | 347 | 90.8 | 825 | 94.5 | |

| No | 83 | 6.6 | 35 | 9.2 | 48 | 5.5 | |

| Preferences of pain education methods | |||||||

| Printed handbook | 477 | 38.0 | 155 | 40.6 | 322 | 36.9 | 0.215 |

| On-site education | 593 | 47.3 | 195 | 51.0 | 398 | 45.6 | 0.075 |

| Peer support group | 804 | 64.1 | 211 | 55.2 | 593 | 67.9 | 0.000 |

| Online education led by intervention deliverer | 542 | 43.2 | 146 | 38.2 | 396 | 45.4 | 0.019 |

| Self-management via mobile application | 635 | 50.6 | 201 | 52.6 | 434 | 49.7 | 0.344 |

| Preferences of pain education duration | 0.000 | ||||||

| Up to one week | 184 | 14.7 | 96 | 25.1 | 88 | 10.1 | |

| 2–4 weeks | 536 | 42.7 | 159 | 41.6 | 377 | 43.2 | |

| 5–8 weeks | 308 | 24.5 | 71 | 18.6 | 237 | 27.1 | |

| More than 2 months | 221 | 17.6 | 55 | 14.4 | 166 | 19.0 | |

| Other | 6 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.3 | 5 | 0.6 | |

| Preferences of pain education settings | 0.000 | ||||||

| 30 min, once a week | 254 | 20.2 | 121 | 31.7 | 133 | 15.2 | |

| 1 h, once a week | 282 | 22.5 | 88 | 23.0 | 194 | 22.2 | |

| 30 min, 2–3 times a week | 370 | 29.5 | 112 | 29.3 | 258 | 29.6 | |

| 1 h, 2–3 times a week | 230 | 18.3 | 37 | 9.7 | 193 | 22.1 | |

| 30 min, over 3 times a week | 79 | 6.3 | 17 | 4.5 | 62 | 7.1 | |

| 1 h, over 3 times a week | 40 | 3.2 | 7 | 1.8 | 33 | 3.8 | |

| Preferences of pain education topic | |||||||

| Definition and mechanism of pain | 482 | 38.4 | 174 | 45.5 | 308 | 35.3 | 0.001 |

| Self-assessment of pain | 659 | 52.5 | 207 | 54.2 | 452 | 51.8 | 0.431 |

| Effects of pain | 764 | 60.9 | 211 | 55.2 | 553 | 63.3 | 0.007 |

| How acute pain become chronic | 630 | 50.2 | 207 | 54.2 | 423 | 48.5 | 0.062 |

| Disease and pain | 545 | 43.4 | 168 | 44.0 | 377 | 43.2 | 0.794 |

| Medications and side-effects | 717 | 57.1 | 199 | 52.1 | 518 | 59.3 | 0.017 |

| Non-drug treatment | 407 | 32.4 | 135 | 35.3 | 272 | 31.2 | 0.145 |

| Preferences of other pain management methods | |||||||

| Exercise therapy | 718 | 57.2 | 217 | 56.8 | 501 | 57.4 | 0.848 |

| Psychotherapy | 783 | 62.4 | 208 | 54.5 | 575 | 65.9 | 0.000 |

| Game therapy | 461 | 36.7 | 134 | 35.1 | 327 | 37.5 | 0.421 |

| Massage therapy | 608 | 48.4 | 189 | 49.5 | 419 | 48.0 | 0.629 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

He, J.; Tse, M.M.Y.; Kwok, T.T.O.; Wu, T.C.M.; Tang, S. Exploring the Pain Situation, Pain Impact, and Educational Preferences of Pain Among Adults in Mainland China, a Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030289

He J, Tse MMY, Kwok TTO, Wu TCM, Tang S. Exploring the Pain Situation, Pain Impact, and Educational Preferences of Pain Among Adults in Mainland China, a Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(3):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030289

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Jiafan, Mimi Mun Yee Tse, Tyrone Tai On Kwok, Timothy Chung Ming Wu, and Shukkwan Tang. 2025. "Exploring the Pain Situation, Pain Impact, and Educational Preferences of Pain Among Adults in Mainland China, a Cross-Sectional Study" Healthcare 13, no. 3: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030289

APA StyleHe, J., Tse, M. M. Y., Kwok, T. T. O., Wu, T. C. M., & Tang, S. (2025). Exploring the Pain Situation, Pain Impact, and Educational Preferences of Pain Among Adults in Mainland China, a Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare, 13(3), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13030289