Abstract

Background: The COVID-19 lockdown posed unprecedented psychological challenges worldwide. In Spain, Mutual Collaborators with Social Security manage work-related disabilities, including mental health cases. Objectives: To describe and analyze work-related disabilities with mental health diagnoses during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain from the perspective of a Mutual Collaborator with Social Security in the Spanish healthcare system. Methods: Descriptive, retrospective, and cross-sectional study of a sample of 5135 patients. Descriptive statistics reported mean values and standard deviation by sex and age. Inferential analyses were conducted using the Mann–Whitney U-test and correlation analysis. Results: The study population included 5135 patients managed by a Mutual Collaborator with Social Security during the COVID-19 lockdown, 63.5% of whom were women. Cantabria reported the highest average sick leave duration (62.80 days), while La Rioja had the lowest (39.19 days). Generalized anxiety disorder was the most prevalent diagnosis (69.17%), followed by adaptive disorders and mild depression. Women had a slightly higher prevalence of anxiety, while men showed higher rates of adaptive disorders. Conclusions: The findings underscore the psychological impact of the COVID-19 lockdown, revealing significant sex and regional differences in mental health diagnoses and sick leave duration. Generalized anxiety disorder was the predominant diagnosis, highlighting the need for targeted mental health interventions during crises.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic created an unprecedented global crisis with significant consequences worldwide [1]. The public health emergency caused by this novel disease required quarantine measures in many countries and the isolation of infected individuals to reduce the risk of contagion [2,3]. People exposed to the stress of the outbreak may experience marked distress, leading to adjustment disorders, and in cases of persistent sadness, major depressive disorder (MDD) can develop [4].

Depression can manifest and worsen due to multiple factors, such as genetic predispositions, personal experiences, and social-environmental conditions [5]. In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, various studies have reported a significant increase in stress and anxiety levels, which can lead to the onset or exacerbation of depressive symptoms [6,7]. Moreover, the coexistence of multiple mental disorders often shares common etiological pathways, further complicating clinical management [8].

In Spain, psychiatric disorders are the second leading cause of temporary disability [9]. Globally, psychiatric conditions account for approximately 25% of the disease burden, as reported by the World Bank and the World Health Organization (WHO), resulting in substantial economic repercussions [10]. The mental health toll of quarantine measures is evident, with large-scale studies underway to better understand the effects of lockdowns, particularly in Europe. During pandemics, fear increases stress and anxiety in healthy individuals while exacerbating symptoms in those with pre-existing mental health disorders [11]. These conditions can evolve into depression, panic attacks, PTSD, psychotic symptoms, and even suicide [12], especially in quarantined patients, who tend to experience higher levels of psychological stress [2,7].

Mutual Collaborators with Social Security (MCSS)—formerly known as Mutual Societies for Work Accidents and Occupational Diseases until 2014—are private, non-profit organizations operating under the supervision of the Ministry of Labor and Social Economy. Their primary role is to manage professional contingencies, including healthcare services. They may also oversee the management of temporary disability benefits for common contingencies (ITCC) and provide prevention activities for affiliated companies [13].

A “common contingency” (CC) is defined as a situation in which a worker is unable to perform their job due to a non-work-related illness or injury lasting more than 72 h, receiving healthcare through the Public Health System (SPS) [14]. Psychiatric disorders are highly prevalent among primary care patients, with studies estimating a prevalence rate of 23–30% in the general population [9]. Specifically, these conditions disproportionately affect women, younger individuals, and those with lower educational and cultural levels. Women are more likely to experience generalized anxiety disorder and depression, while younger individuals often present with adjustment disorders [15]. Additionally, lower educational and cultural levels are associated with reduced access to mental health resources and delayed treatment initiation, exacerbating the chronicity and severity of these conditions [16]. Psychiatric disorders are typically chronic, prone to relapses, and often necessitate prolonged periods of temporary disability, occasionally progressing to permanent incapacity [17].

Emerging mental health issues associated with SARS-CoV-2 may lead to long-term health challenges. Evidence from past epidemics, such as the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak and the 2012 MERS-CoV outbreak, revealed that up to 35% of SARS survivors developed psychiatric symptoms during recovery [18,19], while nearly 40% of MERS patients required psychiatric intervention [20]. These historical precedents underscore the urgency of understanding the mental health impacts of COVID-19 to inform public health strategies and interventions better.

For this reason, this study aims to describe and analyze mental health-related temporary disabilities during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain, with a focus on their prevalence, duration, and demographic characteristics, including sex, age, and regional distribution. These disabilities include Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), adjustment disorder with Conduct Disturbance, Major Depressive Disorder (Single Mild Episode), Nervousness, Acute Stress Reaction, Neurotic Depression, Unspecified Depression, Panic Disorder (Episodic Paroxysmal Anxiety), Major Depressive Disorder (Recurrent), Agoraphobia (with/without Panic Attacks), Social Phobias, Demoralization and Apathy, and Unspecified Insomnia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Setting

This study employed a descriptive, retrospective, observational, cross-sectional, and analytical design. It aimed to assess the prevalence of temporary incapacity for work due to common contingencies (ITCC) with a diagnosis of mental health conditions during the COVID-19 lockdown period from 14 March 2020 to 21 June 2020 among workers affiliated with the Asepeyo mutual insurance, Spain. The study utilized pre-existing data from medical records and databases, focusing on events and variables recorded before and during the specified period. The study was conducted in Spain, and the analysis included all patients who experienced ITCC due to mental health conditions during the specified period.

2.2. Sample

The sample consisted of patients who met the following inclusion criteria. (1) Individuals who ITCC leave certified by the Public Health Service (SPS) with a mental health diagnosis. (2) Patients whose incapacity was managed by Asepeyo mutual insurance during the COVID-19 lockdown period. The exclusion criteria were as follows. (1) Patients who were already on psychiatric leave before the COVID-19 lockdown. (2) Patients with relevant mental health diagnoses who have not been evaluated by the responsible healthcare personnel. (3) Cases where psychiatric conditions are deemed unrelated to COVID-19. (4) Patients whose medical records lacked sufficient data to confirm the mental health diagnosis or the duration of ITCC leave.

2.3. Procedure

Data for this study were exclusively obtained from the CHAMAN database, maintained by Asepeyo, and authorized by Social Security in compliance with the applicable Spanish data protection regulations (LOPD). Patient records were pseudo-anonymized using numerical codes (Medical Record Number) and based on ICD-10 coded diagnoses. No personally identifiable information, such as names, surnames, or ID numbers, was accessed.

2.4. Variables

The primary variables of interest in this study were the prevalence of ITCC due to mental health conditions, defined as the frequency of patients diagnosed with mental health disorders who were granted ITCC during the study period, and the duration of ITCC, measured as the total number of days on leave for each patient. Secondary variables included sex, analyzed to explore potential differences in ITCC prevalence between genders and age and examined to assess correlations between age and the duration of incapacity.

2.5. Data Collection

Data were collected from the CHAMAN database, a secure database managed by Asepeyo mutual insurance. The records were accessed under strict data protection protocols to ensure patient confidentiality. Data were pseudo-anonymized to maintain the anonymity of participants. The database contains records based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes and is authorized by Social Security for use in research. Only data relevant to the study, such as ITCC records, diagnosis, age, and sex, were extracted.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables (e.g., sex) and means with standard deviations for continuous variables (e.g., age and total days on leave). The analysis was carried out for the total sample and stratified by ACs. A Z-test for differences in proportions was applied to prevalence data to assess differences by sex across ACs. The nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare age and days on leave between different sex groups.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA), with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Asepeyo Ethical Committee, Spain (Approval Code: 2022/48-MLA-ASEPEYO. Approval Date: 31 May 2022). All procedures adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (October 2013, Fortaleza, Brazil). This study ensured strict confidentiality of patient data, and no personally identifiable information was used.

3. Results

The Asepeyo mutual insurance population who experienced temporary incapacity for work (ITCC) with a mental health-related diagnosis during the COVID-19 lockdown period in 2020 consisted of 5135 patients, with 3259 (63.5%) being women and 1876 (36.5%) men. Across all Autonomous Communities (ACs.), more women than men experienced ITCC; however, this difference was not statistically significant in Murcia and La Rioja. The regions with the highest proportion of women experiencing ITCC were Aragón (83.8%), followed by Castilla-La Mancha (70.9%) and Castilla y León (69.7%). The overall mean age was 44.4 years, with a standard deviation of 0.49 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patients with mental health-related ITCC during COVID-19 lockdown, by sex and ACs n = 5135.

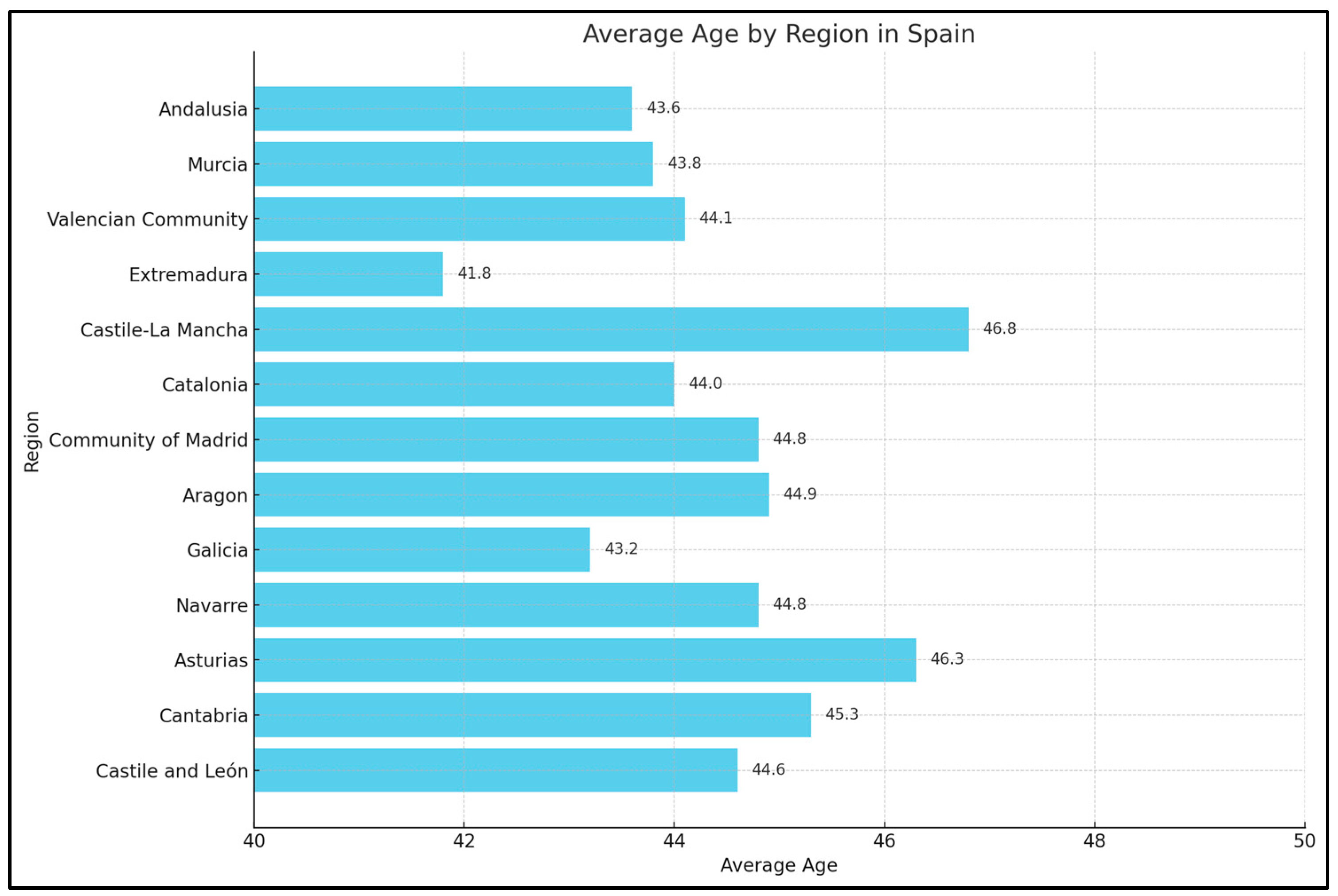

Castilla-La Mancha had the highest mean age (46.8 years), with women having a mean age of 47.7 years and men 44.5 years. In contrast, Extremadura had the lowest mean age at 41.8 years, with women having a mean age of 42.8 years and men 39.7 years. Other regions with lower average ages included Illes Balears (43.0 years), Andalucía (43.6 years), and Canarias (43.8 years). The only statistically significant difference in mean age between men and women was observed in Andalucía (p = 0.001). Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2.

Age and sex distribution of patients with mental-health related ITCC during COVID-19 lockdown, ACs.

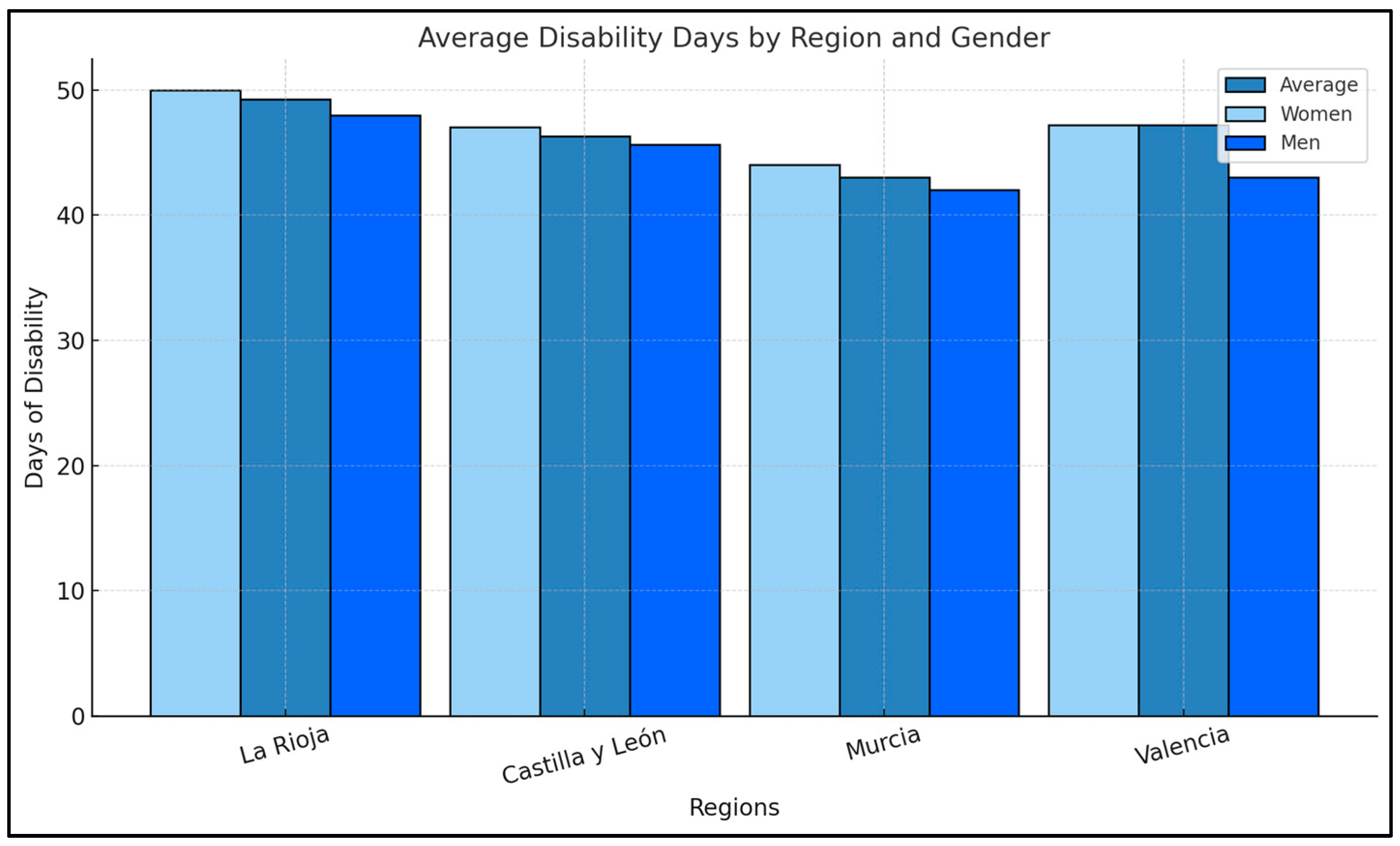

Figure 1.

Average Disability Days by Region and Gender.

Cantabria had the highest average number of sick leave days, with a mean of 62.80 days, while La Rioja had the lowest, 39.19 days. Significant differences in the average number of sick leave days were observed in Castilla y León (p = 0.002). Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 3.

Sick leave duration of patients with mental health-related ITCC during COVID-19 lockdown, by ACs.

Figure 2.

Average Age by Region and Gender in Spain.

The most prevalent diagnoses identified in this study were 13, ranked from the highest to the lowest prevalence: Generalized anxiety disorder (69.17%), with 2252 women (69.10%) and 1300 men (69.30%). (1) Adjustment disorder with conduct disturbance (11.47%), with 351 women (10.77%) and 238 men (12.69%). (2) Major depressive disorder, single mild episode (7.52%), with 236 women (7.24%) and 150 men (8%). (3) Nervousness (3.14%), with 100 women (3.07%) and 61 men (3.25%). (4) Acute stress reaction (2.59%), with 102 women (3.13%) and 31 men (1.65%), statistically significant (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

The most prevalent diagnoses during the COVID-19 lockdown across ACs.

4. Discussion

This study sheds light on the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of workers, as evidenced by the analysis of 5135 cases of temporary incapacity for work due to mental health disorders managed by MCSS Asepeyo.

The findings align with previous research that has highlighted the extensive mental health repercussions of global health crises, such as SARS and MERS, where the combination of isolation and uncertainty amplifies psychological distress [18,19]. Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) emerged as the most frequently diagnosed condition, accounting for 69.17% of cases, followed by adjustment disorders (11.47%) and mild major depressive disorder (7.52%). These trends are consistent with global patterns observed during the pandemic [6,15].

One of the most important findings is the gender disparity in ITCC cases, with women comprising 63.5% of the cohort. This trend is consistent with studies, such as by Hartman et al. [21], which indicate that women are disproportionately affected by mental health conditions due to biological predispositions, societal expectations, and occupational pressures, including caregiving responsibilities and work environments with reduced job security The additional caregiving and professional demands that many women faced during the pandemic likely compounded their mental health challenges [22]. This gender-specific vulnerability is further underscored by the higher prevalence of acute stress reactions in women (3.13%) compared to men (1.65%). Similar patterns were observed by Pappa et al. [15], who documented elevated rates of anxiety, depression, and insomnia among women, particularly those working in healthcare, during the pandemic.

The age group most affected by the pandemic’s mental health impacts consisted of individuals aged 40–49, with an average age of 44.4 years in the studied cohort. This observation aligns with findings by Charlson et al. [23], who reported a peak prevalence of anxiety disorders in this demographic. The dual pressures of professional responsibilities and family obligations likely contribute to the heightened vulnerability of middle-aged adults. These results highlight the necessity of tailored mental health interventions for this age group.

Regional disparities also provide significant insights into the pandemic’s mental health impact. While the study focused on various regions, evidence from Andalusia, as highlighted in Rodríguez-Rey et al., [24] indicates elevated levels of psychological distress in the general population during the initial stages of the pandemic [2]. Women in Andalusia were particularly vulnerable, facing unique challenges stemming from professional caregiving roles and family obligations. This aligns with broader findings from our cohort, emphasizing the disproportionate burden borne by women during the pandemic. Addressing these regional-specific dynamics is critical for developing equitable and effective mental health interventions.

Cantabria recorded the most extended average duration of sick leave (62.80 days), while La Rioja had the shortest (39.19 days). Such regional variations likely reflect differences in healthcare infrastructure, socioeconomic conditions, and the availability of mental health resources. Vicente-Pardo et al. highlighted similar findings during the pandemic, emphasizing the importance of harmonizing mental healthcare policies and ensuring equitable resource allocation [25].

This study also brings attention to the chronic nature of some mental health conditions, particularly generalized anxiety disorder. Research by Cuijpers et al. [26] has shown that such disorders can persist for years if left untreated, raising questions about the readiness of affected individuals to reintegrate into the workforce. These findings underscore the critical need for sustained therapeutic and occupational support to facilitate long-term recovery and effective reintegration.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

This study provides a robust analysis of ITCC cases during the pandemic, leveraging an extensive and comprehensive dataset to examine trends in diagnostic prevalence, demographic patterns, and regional disparities. Including gender-specific and region-specific analyses offers valuable insights that can inform more tailored mental health policies.

However, this study has certain limitations. The retrospective nature of the design restricts the ability to draw causal inferences. Additionally, relying on data from a single mutual insurance organization, Asepeyo may limit the findings’ generalizability to other regions or populations. The exclusion of individuals already on sick leave for mental health conditions before the pandemic could also result in an underestimation of the actual burden of these disorders.

4.2. Implications for Practice and Future Research

The findings emphasize the need for proactive strategies, such as gender-sensitive interventions and tailored support for middle-aged workers, to address the psychological toll of the pandemic. Addressing regional disparities through equitable resource allocation and program stabilization can strengthen workforce resilience for future crises.

Policymakers, healthcare providers, and employers can develop effective strategies to support a healthier, more resilient workforce capable of navigating future public health challenges.

Future investigations should prioritize longitudinal studies to monitor recovery trajectories and assess the effectiveness of mental health interventions implemented during the pandemic. Investigating the particular vulnerabilities of high-stress occupations, such as those in healthcare, could further inform targeted support strategies, as suggested by Pappa et al. and other studies focusing on psychological distress during health crises [15,27]. Additionally, incorporating qualitative perspectives could provide a richer understanding of the lived experiences of affected workers, complementing quantitative findings.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights the significant psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the Spanish workforce, particularly among those with temporary incapacity for work due to mental health diagnoses. Key findings include gender disparities, age-specific vulnerabilities, and regional differences in sick leave duration and prevalence. The results indicated that 63.5% of the patients were especially vulnerable women, possibly due to additional responsibilities during the pandemic. Aragon reported the highest percentage of affected women (83.8%).

The average age of the patients was 44.4 years, with women being older on average (47.7 years) than men (44.5 years). Regarding the duration of sick leave, Cantabria had the highest average duration (62.8 days), with notable differences between men (70.4 days) and women (58.8 days). In contrast, La Rioja recorded the shortest duration (39.19 days).

Generalized anxiety disorder was the most common diagnosis, accounting for 69.17% of cases, followed by adjustment disorders (11.47%) and mild major depressive disorder (7.52%). Women exhibited higher rates of acute stress reactions (3.13%) compared to men.

This analysis reveals how factors such as sex and regional differences influenced emotional responses during the pandemic. These findings underscore the need for mental health policies tailored to gender and regional contexts to enhance care delivery during future crises. By addressing the chronicity of conditions like generalized anxiety disorder and ensuring sustained support, policymakers can foster a healthier and more resilient workforce.

Future research should focus on exploring the long-term implications of the pandemic on mental health and refine intervention strategies to better support workforce well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.G.N., J.F.S. and P.T.E.; methodology, E.M.G.N. and J.F.S.; software, J.F.S.; validation, E.M.G.N. and J.F.S.; formal analysis, E.M.G.N. and J.F.S.; funding acquisition, A.S.S.; investigation, E.M.G.N.; resources, E.M.G.N. and J.F.S.; data curation, E.M.G.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.G.N., P.T.E. and A.S.S.; writing—review and editing, E.M.G.N., P.T.E., J.F.S. and A.S.S.; visualization, E.M.G.N. and A.S.S.; supervision, J.F.S. and J.A.P.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Asepeyo Scientific and Ethical Committee (Approval Code: 2022/48-MLA-ASEPEYO. Approval Date: 31 May 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of this study, which involved the analysis of anonymized statistical data previously collected by the center. The data was processed per ethical guidelines and current data protection regulations, ensuring no directly identifiable information was linked to the participants. Consequently, informed consent was not required as the study did not involve interventions or identifiable personal data. This methodology safeguards the privacy and confidentiality of the individuals involved while adhering to legal and ethical principles. No identifiable patients or individuals are included in this publication; therefore, written informed consent for publication was not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Aggregated data supporting this study’s findings are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, A.S.-S., and are subject to review. These data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns and the potential for compromising research participant privacy/consent.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank MCSS Asepeyo for providing access to the anonymized data used in this study. Their collaboration and assistance enabled the retrospective analysis of mental health-related temporary incapacity cases during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Pau Tolo Espinet was employed by the company Mutua Intercomarcal. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Shigemura, J.; Ursano, R.J.; Morganstein, J.C.; Kurosawa, M.; Benedek, D.M. Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 281–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, S.K.; Webster, R.K.; Smith, L.E.; Woodland, L.; Wessely, S.; Greenberg, N.; Rubin, G.J. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 2020, 395, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaumer-Streit, B.; Mayr, V.; Dobrescu, A.I.; Chapman, A.; Persad, E.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Siebert, U.; Ledinger, D.; Zachariah, C.; et al. Quarantine alone or in combination with other public health measures to control COVID-19: A rapid review. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 4, CD013574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huremovic, D. Psychiatry of Pandemics: A Mental Health Response to Infection Outbreak; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kupfer, D.J.; Frank, E.; Phillips, M.L. Major depressive disorder: New clinical, neurobiological, and treatment perspectives. Lancet 2012, 379, 1045–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickens, C.M.; Popal, V.; Fecteau, V.; Amoroso, C.; Stoduto, G.; Rodak, T.; Li, L.Y.; Hartford, A.; Wells, S.; Elton-Marshall, T.; et al. The mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals with depressive, anxiety, and stressor-related disorders: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0295496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Styra, R.; Hawryluck, L.; Robinson, S.; Kasapinovic, S.; Fones, C.; Gold, W.L. Impact on healthcare workers employed in high-risk areas during the Toronto SARS outbreak. J. Psychosom. Res. 2008, 64, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.-E.; Harris, C.; Danielle, L.-C. The prevalence of mental health conditions in healthcare workers during and after a pandemic: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2022, 78, 1551–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henares Montiel, J.; Ruiz-Pérez, I.; Sordo, L. Mental Health in Spain and Differences by Gender and Autonomous Communities. Gac. Sanit. 2020, 34, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velavan, T.P.; Meyer, C.G. The COVID-19 epidemic. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2020, 25, 278–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Cheung, T.; Ng, C.H. Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 228–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Constitution of the World Health Organization; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1946; Available online: https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Castellano, M.; Molina, A. La IT y su control médico. Aspectos médico-legales. La Mutua. Rev. Téc. Salud Lab. Prev. 2006, 10, 9–35. [Google Scholar]

- Royal Decree 625/2014, of July 18, Regulating Certain Aspects of the Management and Control of Temporary Disability Processes During the First 365 Days of Their Duration. B.O.E. 2014, p. 176. Available online: https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2014-12345 (accessed on 19 January 2025).

- Pappa, S.; Ntella, V.; Giannakas, T.; Giannakoulis, V.G.; Papoutsi, E.; Katsaounou, P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 88, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada-Baltar, A.; Jiménez-Gonzalo, L.; Gallego-Alberto, L.; Pedroso-Chaparro, M.D.S.; Fernandes-Pires, J.; Márquez-González, M. “We Are Staying at Home”. Association of Self-perceptions of Aging, Personal and Family Resources, and Loneliness With Psychological Distress During the Lock-Down Period of COVID-19. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2020, 76, e10–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez, J.F.; Martínez, J.A.; Rodado, C.; Martínez, D.; Sánchez, P.; Reyes, A. Incidence of Sick Leaves in an Urban Health Centre: Considerations Regarding the Diagnostic Groups (WONCA). That Orig. Them Med. Trab. 1996, 5, 11–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, K.K.; Chan, S.K.; Ma, T.M. Posttraumatic stress after SARS. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2005, 11, 1297–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, I.W.; Chu, C.M.; Pan, P.C.; Yiu, M.G.; Chan, V.L. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2009, 31, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.C.; Yoo, S.Y.; Lee, B.H.; Lee, S.H.; Shin, H.S. Psychiatric findings in suspected and confirmed Middle East Respiratory Syndrome patients quarantined in hospital: A retrospective chart analysis. Psychiatry Investig. 2018, 15, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, C.A.; Larsson, H.; Vos, M.; Bellato, A.; Libutzki, B.; Solberg, B.S.; Chen, Q.; Du Rietz, E.; Mostert, J.C.; Kittel-Schneider, S.; et al. Anxiety, Mood, and substance use disorders in Adult Men and Women with and without ADHD: A Substantive and Methodological Overview. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2023, 151, 105209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, H.S.; Alves, R.M.; Nunes, A.D.D.; Barbosa, I.R. Prevalence and Associated Factors of Common Mental Disorders in Women: A Systematic Review. Public Health Rev. 2021, 42, 1604234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlson, F.; van Ommeren, M.; Flaxman, A.; Cornett, J.; Whiteford, H.; Saxena, S. New WHO Prevalence Estimates of Mental Disorders in Conflict Settings: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet 2019, 394, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rey, R.; Garrido-Hernansaiz, H.; Collado, S. Psychological Impact and Associated Factors During the Initial Stage of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Among the General Population in Spain. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Pardo, J.M.; López-Guillén-García, A. Labor Incapacity during COVID-19, Preventive Aspects, and Consequences. Med. Segur. Trab. 2021, 67, 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuijpers, P.; Sijbrandij, M.; Koole, S.L.; Huibers, M.J.H.; Berking, M.; Andersson, G. Psychological Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2014, 34, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glowacz, F.; Schmits, E. Psychological distress during the COVID-19 lockdown: The young adults most at risk. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 293, 113486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).