Abstract

Background: The present study aimed to identify the differences between experiences, in terms of oral health-related quality of life, pain, side effects and/or other complications, of adults undergoing orthodontic treatment using removable aligners and fixed labial or lingual appliances. Methods: The review was registered with PROSPERO, and a comprehensive electronic search was undertaken without language or date restrictions. Randomised and non-randomised trials and prospective cohort and cross-sectional studies along with case series were included. The Cochrane Collaboration’s Risk of Bias 2 Tool, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale and The Risk Of Bias In Non-Randomized Studies—of Interventions tools were used to assess quality. Data were grouped in terms of oral health-related quality of life, pain side effects and/or other complications. Results: Data from 35 studies were included; 9 were eligible for meta-analysis. Thus 2611 participants were included related to removable aligners (n = 513), fixed labial (n = 1816) and lingual (n = 218) appliances or a combination (n = 64) of appliances. The standardised mean differences in visual analogue scale pain reports between 24 h and 7 days were −10.02 (95% CI: −11.13, −8.91) for aligners and −6.40 (95%CI: −10.42, −2.38) for labial appliances (p = 0.09). There was a significant improvement in dental self-confidence following fixed labial appliance treatment (p = 0.001). Conclusions: No difference was detected in short-term pain with aligners and labial appliances. Aligners may have less impact on oral health-related quality of life measures compared to labial appliances. Lingual appliances have a persistent impact on speech, despite some adaptability. Any deterioration in oral health-related quality of life measures during treatment appears temporary. Further randomised trials using validated assessment tools and comparing aligners and labial and lingual appliances are required.

Keywords:

oral health; quality; life; pain; side effects; adults; orthodontic; treatment; braces; aligners 1. Introduction

With the increased demand for adult orthodontic treatment, orthodontics has evolved to facilitate the corresponding demand for appliances that are aesthetically pleasing and have little impact on everyday lives [1]. Generational differences may influence patients’ decisions to seek aesthetically pleasing appliances, with millennials reported to be more focused on image compared to previous generations [2].

Clinician-based outcomes have traditionally been the focus of much orthodontic research, with patient-based measures not being reported as frequently in the literature [3]. The drive of manufacturers to fabricate aesthetically pleasing appliances needs to be met with research evaluating these new appliances in terms of both clinician- and patient-based outcome measures.

Optimal oral health enables an individual to eat, speak and socialise without active disease, discomfort or embarrassment, which contributes to general well-being [4]. Quality of life (QoL) is defined as a person’s sense of well-being that stems from satisfaction or dissatisfaction with the areas of life that are important to them [5]. The impact of oral health and disease on QoL is known as oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL). OHRQoL changes during treatment warrant more understanding to help the clinician understand how patients cope with the treatment [6]. Treatment experience is influenced by functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical disability, psychological disability, social disability and other disabilities [7].

An in-depth understanding of adult patient experiences with the different range of appliances now available would allow clinicians to provide more relevant information to patients and, in turn, facilitate the development of a patient-centred approach to providing more optimal care and informed consent. However, to date, there is relatively very little understanding of the impact of these appliance choices on their daily lives, with only two quantitative studies comparing the three appliance systems in relation to pain and oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in adults, with their findings being inconclusive [8,9].

In contrast, a greater number of studies exist to compare clear aligner therapy with fixed labial appliances. They report participants treated with the former report less pain, eating difficulties and an overall lower in-treatment negative experience during the early stages of treatment [10,11,12,13]. In contrast, comparison of fixed labial and lingual appliances does not appear to demonstrate any significant differences in pain experience, but the latter were associated with greater oral discomfort, dietary changes, swallowing and speech disturbances and social problems than the labial appliance [14,15].

In light of the increasing uptake of adult orthodontic treatment and the availability of aesthetically pleasing alternative appliances, there is a need to systematically review the research in this field, in particular taking into account patient-centred outcomes. Thus, the present study aimed to identify the differences between experiences, in terms of oral health-related quality of life, pain, side effects and/or other complications, of adults undergoing orthodontic treatment using removable aligners and fixed labial or lingual appliances.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO international prospective register of systematic reviews (www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO, accessed on 1 July 2020, CRD42020192841). The current systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [8].

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The following PICO selection criteria were applied:

Participants: Adults (older than 18 years) requiring orthodontic treatment (extraction or non-extraction).

Intervention: Orthodontic treatment with fixed (labial or lingual) appliances or removable (clear aligner) appliances.

Comparator: A comparison and/or control group was not essential for inclusion.

Outcomes:

- (i)

- Participant experiences and the impact of the various appliances on OHRQoL and self-esteem.

- (ii)

- Severity and nature of pain or discomfort experienced with orthodontic appliances.

- (iii)

- Other side effects and/or complications, including the effect on function.

The following were considered eligible: Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised controlled clinical trials (CCTs), observational cohort and cross-sectional studies, prospective case series (minimum sample size of 10 patients) and qualitative studies exploring adults’ views and experiences were also included.

Exclusion criteria: Craniofacial syndromes, temporomandibular dysfunction, those prescribed analgesics or antidepressant medication for psychiatric disease or chronic medical conditions and participants undergoing dento-alveolar or orthognathic surgery.

2.3. Information Sources, Search Strategy and Study Selection

The search strategy is described in Appendix A Table A1. Comprehensive searches, without date or language restrictions, were conducted using the following electronic databases: MEDLINE via PubMed and Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane and Embase. Databases were searched from inception until 3 May 2023. Unpublished or “grey” literature was searched using Google Scholar, OpenGrey, Directory of Open Access Journals, Digital Dissertations and the Meta-Register of Controlled Trials. Hand searching was performed from the reference lists of the full-text articles and other relevant systematic reviews. Full-text assessments of the studies for inclusion in the review were performed independently and in duplicate by two authors (HB and CS), and any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer (AJ). If further information was required, the authors were contacted for clarification.

2.4. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment in Individual Studies

The risk of bias assessment was performed independently and in duplicate by two authors (HB; CS), and any disagreements were resolved with a third reviewer (AJ). Different tools were used to assess research quality due to the diversity of study designs included. Randomised trials were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2 (RoB2) [16].

The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of non-randomised studies including cohort studies [17]. An appropriately adapted version of the scale suitable for the assessment of cross-sectional studies was used for studies of this nature.

The Risk of Bias In Non-Randomised Studies—of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool was used to assess one quasi-experimental study [18].

Studies with low or unclear risk of bias or medium to high quality were chosen for inclusion in any subsequent meta-analysis.

2.5. Data Items and Collection

The following characteristics were recorded: study design, sample size, participant details, treatment modality and outcome measures, e.g., OHRQoL, self-esteem, pain, side effects and other complications. Data was extracted and described according to the treatment modality (removable aligners, fixed labial or lingual appliances). Data was managed using Covidence© online systematic review software (https://www.covidence.org, accessed on 1 July 2020, Veritas Health Innovation Ltd, Melbourne, Australia).

2.6. Summary Measures and Approach to Statistical Analysis

OHRQoL scores reporting on the same domain at common timepoints were combined to obtain pooled mean proportion values, with standard deviation and/or 95% confidence intervals (CIs) if applicable. Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores for pain, when recorded at the same time interval, were managed in a similar manner. Data from qualitative studies was planned for synthesis if the same outcome was reported in more than two studies, followed by integration of quantitative and qualitative results.

2.7. Additional Analysis

A meta-analysis was carried out on studies with low/unclear risk of bias or with moderate/high quality, where the study designs were similar and data could be grouped. Cochrane’s Review Manager (version 5.4.1, available at revman.cochrane.org, accessed 07/2025) was used for meta-analysis, applying the inverse variance method with random effects and testing for the standardised mean difference. Results are presented as forest plots with weighted values and 95% CIs, with a p-value of less than 0.05 being considered statistically significant. The I2 statistic test was applied to quantify heterogeneity among studies.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics of Included Studies

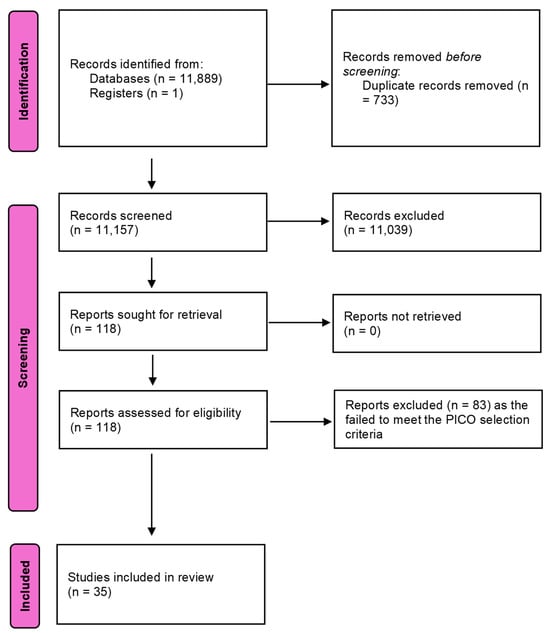

In total, 11,890 articles were identified, and following removal of duplicates, 11,157 studies were screened for eligibility. Title and abstract screening resulted in the identification of 118 articles which were suitable for full-text review. Subsequently 83 articles were excluded for not meeting the PICO selection criteria (Figure 1) and 35 studies were included, consisting of 6 randomised clinical trials, 1 controlled clinical trial, 1 quasi-experimental study, 23 prospective cohort studies, 2 cross-sectional studies, 1 longitudinal observational study and 1 qualitative study (Table 1). Nine studies met the inclusion criteria for meta-analysis, as illustrated in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 35).

A total of 2752 participants were identified from the 35 included studies. Two studies published a variety of outcomes from the same cohort [14,15] and a cross-sectional study by Flores-Mir et al. [10] included the data from the same Invisalign® cohort as Pacheco-Pereira et al. [35]. Of the 2611 independent participants included, 1816 were treated with labial appliances, 513 with aligners (of which 307 were Invisalign®) and 218 with lingual appliances (of which 86 were Incognito). A further 52 participants were managed with a combination of labial appliances and Invisalign® aligners, while 12 participants were included in a study involving thermoplastic retainers with appliances bonded to their lingual aspect for speech assessment.

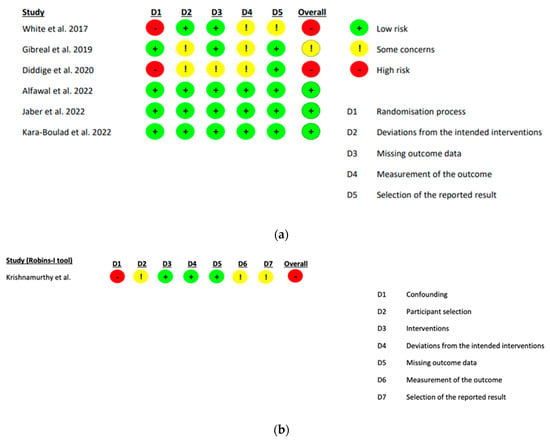

3.2. Risk of Bias Within Studies

RoB2 was used to assess six studies (Figure 2a), NOS was used to assess 25 studies (Appendix A Table A2) with an adapted version used for two cross-sectional studies (Appendix A Table A3) and the ROBINS-I tool was used to assess one quasi-experimental study (Figure 2b). The one qualitative study was not assessed for risk of bias as this is not a commonly undertaken approach.

Figure 2.

(a) Cochrane risk of bias 2 assessment of bias within randomised studies [11,19,20,21,22,23]. (b) ROBINS-I assessment tool for quasi-experimental studies [25].

3.3. Results of Individual Studies, Meta-Analysis and Additional Analysis

The findings were reported in a descriptive manner as the wide variety in appliance type, outcome measures and timepoints meant that quantitative data could not be described in a meaningful way in the data extraction table (Table 1).

3.4. Qualitative Analysis of Results

3.4.1. Three-Arm Studies (Aligners, Labial and Lingual Appliances)

Five studies compared the three treatment modalities in relation to pain and OHRQoL [9,27,28,29,41]). Findings were inconclusive across these studies as Shalish et al. [41] concluded pain was most severe in the lingual appliance group, in contrast to Antonio-Zancajo et al. (2020) [9] who reported lower levels of pain with lingual appliances. Antonio-Zancajo et al. [28] also reported that pain was mild in all groups apart from the labial appliance group, where pain was mild/moderate.

Zamora-Martinez [29] reported that QoL decreased significantly in all groups at the start of treatment but increased at the end of treatment. Alseraidi et al. [27] found that the aligner group reported the highest QoL scores and the labial appliance reported the lowest QoL scores.

3.4.2. Two-Arm Studies

Aligners and labial appliances

Six publications described how participants with aligners experienced less pain than those with labial appliances [11,12,13,23,33,40]. Miller et al. [12] and Gao et al. [13] concluded that participants with aligners reported fewer negative impacts on overall OHRQoL during the initial phase of treatment.

Aligners appeared to be associated with lower in-treatment negative experiences, compared with fixed labial appliances during the first two weeks of treatment [10,11,12,13]. Four studies [10,11,19,20] described how those with fixed appliances had more difficulty eating and chewing compared to aligners.

Labial and lingual appliances

Two publications using the same participant cohort [14,15] found no significant difference in pain among those treated with labial or lingual appliances and that pain decreased for both groups over three months.

Participants with lingual appliances reported more oral discomfort, dietary changes, swallowing difficulty, speech disturbances and social problems than those with labial appliances [14,21].

3.4.3. Single-Arm Studies

Labial appliances

Three studies reported pain during fixed appliance treatment [22,24,34]. Shen et al. [24] and Gibreal et al. [22] reported that pain peaks at 24 h while Johal et al. [34] described how pain peaked between 24 h and 3 days following appliance fit.

Three cohort studies used OHIP-14 to evaluate changes in OHRQoL [36,38,39]. Participants reported a negative effect on OHRQoL during treatment, but OHIP-14 scores returned to pre-treatment norms following appliance removal [36,39]. Two studies used OHIP-14 to assess OHRQoL [13,25] and showed a significant improvement at the end of treatment.

Several studies investigated the influence of labial appliances on OHRQoL using the Psychosocial Impact of Daily Aesthetics Questionnaire (PIDAQ) [31,32,37,45]. Psychological impact was shown to improve over the course of fixed appliance treatment with two authors reporting this as early as six months into treatment [31,37]. Studies that followed their participants for their entire course of orthodontic treatment showed improvements in all domains post-treatment [31,32].

Changes in self-esteem were measured using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale in three studies [36,39,45]. Johal et al. [39] reported no significant changes, while Choi et al. [36] reported significantly lower values 12 months into treatment. Both studies demonstrated improvements in participant scores following removal of appliances, with Choi et al. [36] reporting a level similar to pre-treatment scores and Johal et al. [39] concluding there were improvements in self-esteem. Varela & Garciacamba [44] reported no significant changes in self-esteem; however, these authors used the Tennessee Self Concept Scale which may not be comparable to the Rosenberg self-esteem scale.

Lingual appliances

Two studies investigated the influence that lingual appliances have on speech [42,43] and found that smaller profile lingual brackets had less negative influence. The investigators concluded there was a significant deterioration in speech, which improved at three months but was still worse than pre-treatment.

3.5. Aligners

Pacheco-Pereira et al. [35] reported high levels of satisfaction in eating and chewing which were attributed to the removable nature of aligners. Al Nazeh [30] found that aligner treatment had a less negative impact on OHRQoL in females.

3.6. Quantitative Analysis of Studies

A total of nine studies met the criteria for a meta-analysis [12,13,22,24,31,32,34,36,39].

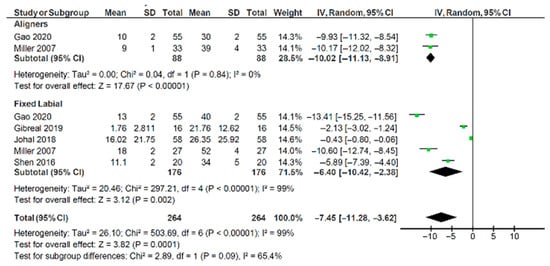

3.7. Pain Experience

Figure 3 shows a forest plot with the combined VAS pain scores for studies that met the inclusion criteria. Aligners showed a significant reduction in pain scores between 24 h and 7 days after appliance fit, with an estimated reduction of −10.02 (95% CI: −11.13, −8.91). The two aligner studies were homogenous (I2 = 0%), adding significantly to the validity of the findings. The five labial appliance studies had high heterogeneity (I2 = 99%). The standardised mean difference in pain VAS scores between 24 h and 7 days was estimated −6.4 (95% CI: −10.42, −2.36) for labial appliances. The test for significant differences between them was not confirmed (χ2 = 2.89, p = 0.09). The heterogeneity for this comparison was moderate (I2 = 65.4%), suggesting a greater degree of caution in interpreting the findings from the studies evaluating labial appliances.

Figure 3.

Forest plot illustrating pain visual analogue scale scores for aligners and labial appliances [12,13,22,24,34].

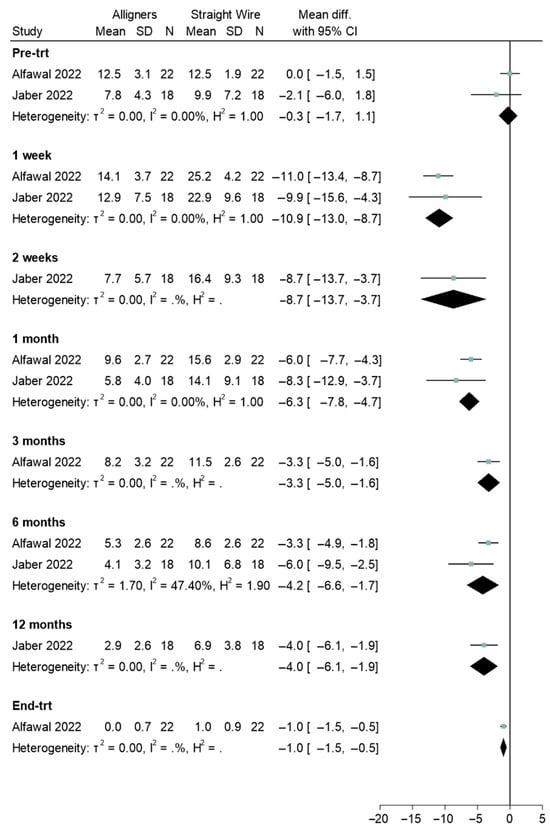

3.8. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life and Self-Esteem

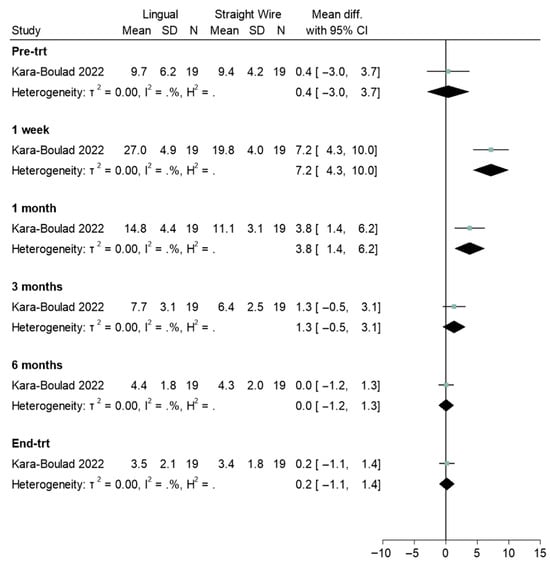

Four studies reported pre- and post-treatment experiences [31,32,36,39]. There was no difference pre-treatment when comparing aligners and labial appliances (Std. mean difference = 0.0, 95% CI: −1.5, 1.5; Figure 4). However, at all other timepoints a significant difference was found, with aligners scoring significantly lower than labial appliances (Figure 4). Lingual and straight wire appliances were also compared (Figure 5). There was no difference between appliances pre-treatment (Std. mean difference = 0.4, 95% CI: −3.0, 3.7). Statistically significant differences were observed at 1-week (Std. mean difference = 7.2, 95% CI: 4.3, 10.0) and 1-month (Std. mean difference = 3.8, 95% CI: 1.4, 6.1). Where a difference was observed, OHRQoL scores were significantly higher for the lingual appliance. Where heterogeneity could be assessed, there was relatively little heterogeneity in terms of sizes of group differences.

Figure 4.

Forest plot illustrating the comparison of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQOL) scores between aligners and straight wire (labial) appliances [19,20].

Figure 5.

Forest plot illustrating the comparison of oral health-related quality of life (OHRQOL) scores between lingual and straight wire (labial) appliances [21].

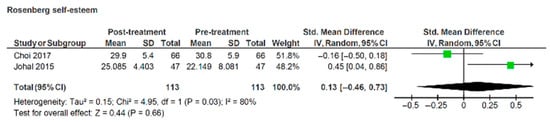

Choi et al. [36] indicated a non-significant reduction over time in Rosenberg self-esteem scale measurements (Std. mean difference = −0.16, 95% CI: −0.5, 0.18), while Johal et al. [39] indicated a significant increase (Std. mean difference = 0.45, 95% CI: −0.04, 0.86) (Figure 6). The pooled data test was insignificantly positive.

Figure 6.

Forest plot illustrating Rosenberg self-esteem scores pre- and post-treatment with labial appliances [36,39].

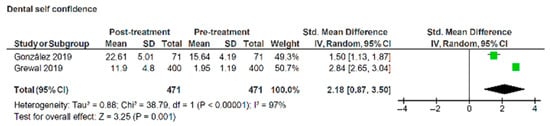

Two studies reported changes in OHRQoL using the PIDA [31,32]. The standardised mean difference for dental self-confidence tested across two publications indicated a significant increase between pre- and post-treatment scores of 2.18 (95% CI:0.87, 3.5) (z = 3.25, p = 0.001) (Figure 7). However, the heterogeneity was high between the studies (I2 = 97%), suggesting a greater degree of caution in interpreting the findings from these studies.

Figure 7.

Forest plot illustrating changes in dental self-confidence domain of psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics questionnaire pre- and post- treatment with labial appliances [31,32].

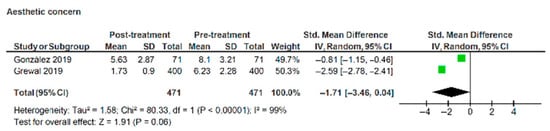

A reduction in aesthetic concern was not significant when the data were pooled (Figure 8), with scores of −1.71 (95% CI: −3.46, 0.04) (z = 1.91, p = 0.06). Heterogeneity across the studies was very high (I2 = 99%), again suggesting a greater degree of caution in interpreting the findings from these studies.

Figure 8.

Forest plot illustrating changes in aesthetic concern domain of psychosocial impact of dental aesthetics questionnaire pre- and post- treatment with labial appliances [31,32].

4. Discussion

Pain experienced by adults undergoing orthodontic treatment with aligners and labial appliances was not statistically significant in this meta-analysis (Figure 3; p = 0.09). Many low quality or high risk of bias studies reported that aligners were less painful than labial appliances; these were not included in the quantitative analysis [11,23,33,40].

This systematic review did not conclude whether labial or lingual appliances inflict more pain during orthodontic treatment. The differences reported between studies may be related to the lack of randomisation and potential confounding factors. Meta-analysis of these studies was deemed inappropriate due to shortcomings in study design. A recent qualitative study looking at the motivations for treatment, choice and impact of aligners and labial and lingual appliances also reported similar experiences in adults [47].

Selection criteria varied widely between studies. The need for dental extractions may influence pain experienced by a participant undergoing orthodontics and also the overall treatment experience.

It is evident from this review that all adult orthodontic treatment will inflict a certain degree of pain and orthodontic pain was commonly described to peak at 24 h following appliance fit. Irrespective of appliance, pain was reported to be less severe following subsequent visits for adjustments [15,23,34,40]. This change likely represents participants becoming accustomed to the experience of orthodontic treatment as it progressed.

Aligners appear to outperform labial appliances within the first two weeks of treatment in terms of in-treatment participant experiences [8,11,12,13]. Data available is short-term and there is little longitudinal data comparing OHRQoL between participants treated with aligners and other orthodontic treatment modalities.

Aligners were used to manage relatively mild malocclusions on a non-extraction basis, while fixed appliances are routinely used in conjunction with extractions, if deemed necessary. One would expect participants treated on an extraction basis to report more negative influences on function secondary to food packing; however, the studies included in this review did not develop participant experiences with this in mind. These are important confounding variables that may adversely affect the conclusions of the individual investigations.

This review suggests that lingual appliances are problematic in terms of speech and tongue soreness [8,42,43]. Longitudinal data reported by Hohoff et al. [42] and Wu et al. [14] describes how speech improves throughout the course of treatment but is still substantial several months into treatment. These findings are supported by a recent qualitative study [47] and patients should be counselled regarding this potential treatment experience.

Several studies reported the negative impact labial appliances have on OHRQoL during treatment, followed by an improvement after removal of the appliance. Meta-analysis of the pre- and post-treatment results comparing labial appliances with aligners showed that at all timepoints OHRQoL scores for aligners were significantly lower than for labial appliances. In contrast, OHRQoL scores for the lingual appliance suggested a worse quality of life. Patients should be counselled on the potential negative sequalae that take place after appliance fit and these negative discussions may be balanced by informing the patient of positive changes in dental self-confidence that are likely to occur as result of treatment, as portrayed by the forest plot in Figure 7.

Three authors reported no significant deterioration in self-esteem during treatment with labial appliances [39,44,45] while one [36] described a worsening amongst their cohort. Following removal of the appliances, two studies reported no changes compared to pre-treatment self-esteem [36,44], while one study suggested a significant improvement [39]. Romero-Maroto et al. [45] did not follow their cohort until treatment was completed. The results of two studies that used the Rosenberg self-esteem scale were combined in a meta-analysis; however, only pre- and post- treatment scores were available as common timepoints [36,39]. Meta-analysis concluded that orthodontic treatment with labial appliances does not result in a statistically significant change in self-esteem, compared to pre-treatment (p = 0.66; Figure 6).

Limitations

The findings may not be extrapolated to all clinical settings in which these appliances are used, for example, adolescent patients. The present study only evaluated the evidence in relation to adults seeking orthodontic treatment to identify any differences between their experiences with these appliances. Whilst systematic reviews offer high-level evidence, the quality of some included studies varied. However, retrospective studies were excluded due to high selection bias risk, but few studies used proper randomisation; issues like poor allocation concealment were common. Randomisation is challenging in adult orthodontics due to strong aesthetic preferences, risking dropout or refusal to participate if adults felt less aesthetically pleasing treatment options were being used. Within the review, studies showed high variability in populations, outcome measures, appliance types and diverse tools (e.g., VAS, OHIP-14, PIDAQ, Rosenberg scale), which limited comparability. The contents of the publication have been verified against the PRISMA checklist (see File S1).

5. Conclusions

- There is a lack of consistency measuring in-treatment experiences with a number of both validated and non-validated questionnaires used to assess changes in OHRQoL in adults undergoing orthodontic treatment.

- From the evidence currently available, there appears to be no significant difference in the pain experienced by adults undergoing orthodontic treatment with aligners or labial appliances during the first week of treatment.

- Aligners may have less impact on OHRQoL when compared to labial appliances within the first two weeks of treatment, as their removable nature allows participants to eat and chew effectively.

- Despite some adaptability, lingual appliances have a persistent impact on speech throughout the duration of treatment.

- Any deterioration in OHRQoL measures with labial appliances during treatment is temporary, and these return to pre-treatment norms following appliance removal, with a statistically significant improvement in dental self-confidence.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13243317/s1, Supplementary File S1: PRISMA checklist.

Author Contributions

A.J.: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, review and editing of manuscript. B.D., H.B. and C.S.: investigation, data curation, writing—original draft. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search Strategy as Used in Databases.

Table A1.

Search Strategy as Used in Databases.

| Database | Search Criteria | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Medline via PubMed | (Orthodont* OR aligners OR Invisalign® OR “lingual orthodont*” OR “adult orthodont*”) AND (“Quality of life” OR “patient-experiences” OR “pain” OR “OHRQoL” OR “patient-concerns” | 2344 |

| Web of Science | #1 = (Orthodont* OR “clear aligner*” OR Invisalign® OR “lingual orthodontic*” OR “adult orthodontic*”) #2 = (“impact” OR “patient experience” OR pain OR OHRQoL OR “patient concern” OR speech OR complication* OR “side-effect”) #3 = (#1 and #2) | 3114 |

| Embase | Same as PubMed search | 2040 |

| Scopus | Same as web of science | 3620 |

| Cochrane | Same as web of science | 771 |

Table A2.

Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale—Cohort Studies (n = 25).

Table A2.

Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale—Cohort Studies (n = 25).

| Study ID | Selection (Max 4 Stars) | Comparability (Max 2 Stars) | Outcome Assessment (Max 3 Stars) | Total Scores (Max 9 Stars) | High Quality: 9 Moderate Quality: 6–8 Low Quality: 1–5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | |||

| Johal et al. [34] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

| Shalish et al. [41] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * | * | 4 | Low |

| Wu et al. [14] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | * | 0 | * | * | 5 | Low |

| Pacheco-Pereira et al. [35] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Wu et al. [15] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | * | 0 | * | * | 5 | Low |

| Varela & Garciacamba [44] | * | * | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

| Shen et al. [24] | * | 0 | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Prado et al. [37] | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0 | * | * | 8 | Moderate |

| Miller et al. [12] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

| Johal et al. [39] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | 0 | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Hohoff et al. [42] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Hohoff et al. [43] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

| Choi et al. [36] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | 0 | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Almasoud et al. [33] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | * | 0 | * | * | 5 | Low |

| Fujiyama et al. [40] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * | * | 4 | Low |

| Chen et al. [38] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | * | * | 5 | Low |

| González et al. [31] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | 0 | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Antonio-Zancajo et al. [9] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | * | * | 4 | Low |

| Grewal et al. [32] | * | * | * | * | * | * | 0 | * | * | 8 | Moderate |

| Lau et al. [26] | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | * | * | 5 | Low |

| AlSeraidi et al. [27] | * | * | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

| Antonio-Zancajo et al. [28] | * | * | * | 0 | 0 | * | 0 | * | * | 6 | Moderate |

| Gao et al. [13] | * | * | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

| Zampora-Martínez et al. [29] | * | * | * | 0 | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

| Al Nazeh et al. [30] | * | 0 | * | * | * | * | 0 | * | * | 7 | Moderate |

*: 1, 0: no, I: representativeness of the exposed cohort; II: selection of the non-exposed cohort; III: ascertainment of exposure; IV: demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at start of study; V: study controls for adult orthodontic treatment; VI: study controls for any additional factor (gender, age, index of orthodontic treatment need, Little’s irregularity); VII: assessment of outcome; VIII: follow up sufficient for outcomes to occur; IX: adequacy of follow up of cohorts.

Table A3.

Modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale Adapted for Cross-Sectional Studies (n = 2).

Table A3.

Modified Newcastle–Ottawa Scale Adapted for Cross-Sectional Studies (n = 2).

| Study ID | Selection (Max 4 Stars) | Comparability (Max 2 Stars) | Outcome Assessment (Max 3 Stars) | Total Scores (Max 9 Stars) | High Quality: 9 Moderate Quality: 6–8 Low Quality: 1–5 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VIII | IX | |||

| Flores-Mir et al. [10] | * | 0 | * | 0 | 0 | 0 | * | * | * | 5 | Low |

| Romero-Maroto et al. [45] | * | * | * | 0 | * | * | * | * | * | 8 | Moderate |

*: 1, 0: no, I: representativeness of the sample; II: non-respondents or selection of controls; III: ascertainment of exposure (validity of measurement tool, secure records); IV: justification of study sample size; V: study controls for Class II treatment. VI: Study controls for additional confounding factor (e.g., gender, age); VII: assessment of outcome (independent blind assessment, self-report, no description); VIII: was follow up long enough for outcome to occur; IX: statistical test (was appropriate and described?).

References

- Rosvall, M.D.; Fields, H.W.; Ziuchkovski, J.; Rosenstiel, S.F.; Johnston, W.M. Attractiveness, acceptability, and value of orthodontic appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2009, 135, 276-e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J.M.; Campbell, W.K.; Freeman, E.C. Generational differences in young adults’ life goals, concern for others, and civic orientation, 1966–2009. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 102, 1045–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsichlaki, A.; O’Brien, K. Do orthodontic research outcomes reflect patient values? A systematic review of randomized controlled trials involving children. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2014, 146, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health Department (Ed.) Assessing the Effects of Health Technologies: Principles, Practice, Proposals, Advisory Group on Health Technology Assessment; His Majesty’s Stationery Office: London, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, G.A.; Smith, D.F.; Dewey, M.; Jacoby, A.; Chadwick, D.W. The initial development of a health-related quality of life model as an outcome measure in epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 1993, 16, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Mcgrath, C.; Hägg, U. The impact of malocclusion and its treatment on quality of life: A literature review. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2006, 16, 381–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slade, G.D. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent. Oral Epidemiol. 1997, 25, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonio-Zancajo, L.; Montero, J.; Albaladejo, A.; Oteo-Calatayud, M.D.; Alvarado-Lorenzo, A. Pain and Oral-Health-Related Quality of Life in Orthodontic Patients During Initial Therapy with Conventional, Low-Friction, and Lingual Brackets and Aligners (Invisalign): A Prospective Clinical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Mir, C.; Brandelli, J.; Pacheco-Pereira, C. Patient satisfaction and quality of life status after 2 treatment modalities: Invisalign and conventional fixed appliances. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 154, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diddige, R.; Negi, G.; Kiran, K.V.S.; Chitra, P. Comparison of pain levels in patients treated with 3 different orthodontic appliances—A randomized trial. Med. Pharm. Rep. 2020, 93, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.B.; McGorray, S.P.; Womack, R.; Quintero, J.C.; Perelmuter, M.; Gibson, J.; Dolan, T.A.; Wheeler, T.T. A comparison of treatment impacts between Invisalign aligner and fixed appliance therapy during the first week of treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2007, 131, 302.e1–302.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M.; Yan, X.; Zhao, R.; Shan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Jian, F.; Long, H.; Lai, W. Comparison of pain perception, anxiety, and impacts on oral health-related quality of life between patients receiving clear aligners and fixed appliances during the initial stage of orthodontic treatment. Eur. J. Orthod. 2021, 43, 353–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, A.K.Y.; McGrath, C.P.J.; Wong, R.W.K.; Rabie, A.B.M.; Wiechmann, D. A comparison of pain experienced by patients treated with labial and lingual orthodontic appliances. Ann. R. Australas. Coll. Dent. Surg. 2008, 19, 176–178. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A.K.Y.; McGrath, C.; Wong, R.W.K.; Wiechmann, D.; Rabie, A.B.M. A comparison of pain experienced by patients treated with labial and lingual orthodontic appliances. Eur. J. Orthod. 2010, 32, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, G.A.; Shea, B.; O’Connell, D.; Peterson, J.; Welch, V.; Losos, M.; Tugwell, P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for Assessing the Quality of Nonrandomised Studies in Meta-Analyses. 2000. Available online: https://scholar.archive.org/work/zuw33wskgzf4bceqgi7opslsre/access/wayback/www3.med.unipmn.it/dispense_ebm/2009-2010/Corso%20Perfezionamento%20EBM_Faggiano/NOS_oxford.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Hernán, M.A.; Reeves, B.C.; Savović, J.; Berkman, N.D.; Viswanathan, M.; Henry, D.; Altman, D.G.; Ansari, M.T.; Boutron, I.; et al. ROBINS-I: A tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ 2016, 355, i4919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alfawal, A.M.H.; Burhan, A.S.; Mahmoud, G.; A Ajaj, M.; Nawaya, F.R.; Hanafi, I. The impact of non-extraction orthodontic treatment on oral health-related quality of life: Clear aligners versus fixed appliances-a randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Orthod. 2022, 44, 595–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaber, S.T.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Burhan, A.S.; Latifeh, Y. The Effect of Treatment With Clear Aligners Versus Fixed Appliances on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients With Severe Crowding: A One-Year Follow-Up Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Cureus 2022, 14, e25472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara-Boulad, J.M.; Burhan, A.S.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Khattab, T.Z.; Nawaya, F.R. Evaluation of the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQoL) in Patients Undergoing Lingual Versus Labial Fixed Orthodontic Appliances: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Cureus 2022, 14, e23379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibreal, O.; Hajeer, M.Y.; Brad, B. Evaluation of the levels of pain and discomfort of piezocision-assisted flapless corticotomy when treating severely crowded lower anterior teeth: A single-center, randomized controlled clinical trial. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, D.W.; Julien, K.C.; Jacob, H.; Campbell, P.M.; Buschang, P.H. Discomfort associated with Invisalign and traditional brackets: A randomized, prospective trial. Angle Orthod. 2017, 87, 801–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Shao, S.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Z.; Lv, D.; Chen, W.; Svensson, P.; Wang, K. Fixed orthodontic appliances cause pain and disturbance in somatosensory function. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2016, 124, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Shivamurthy, P.G.; Sagarkar, R.; Sabrish, S.; Bhaduri, N. Quality of Life Before and After Orthodontic Treatment in Adult Patients with Malocclusion: A Quasi-experimental Study. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2022, 16, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.C.M.; Savoldi, F.; Yang, Y.; Hägg, U.; McGrath, C.P.; Gu, M. Minimally important differences in oral health-related quality of life after fixed orthodontic treatment: A prospective cohort study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2023, 45, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlSeraidi, M.; Hansa, I.; Dhaval, F.; Ferguson, D.J.; Vaid, N.R. The effect of vestibular, lingual, and aligner appliances on the quality of life of adult patients during the initial stages of orthodontic treatment. Prog. Orthod. 2021, 22, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio-Zancajo, L.; Montero, J.; Garcovich, D.; Alvarado-Lorenzo, M.; Albaladejo, A.; Alvarado-Lorenzo, A. Comparative Analysis of Periodontal Pain According to the Type of Precision Orthodontic Appliances: Vestibular, Lingual and Aligners. A Prospective Clinical Study. Biology 2021, 10, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zamora-Martínez, N.; Paredes-Gallardo, V.; García-Sanz, V.; Gandía-Franco, J.L.; Tarazona-Álvarez, B. Comparative Study of Oral Health-Related Quality of Life (OHRQL) between Different Types of Orthodontic Treatment. Medicina 2021, 57, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nazeh, A.A.; Alshahrani, I.; Badran, S.A.; Almoammar, S.; Alshahrani, A.; Almomani, B.A.; Al-Omiri, M.K. Relationship between oral health impacts and personality profiles among orthodontic patients treated with Invisalign clear aligners. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M.J.; Romero, M.; Peñacoba, C. Psychosocial dental impact in adult orthodontic patients: What about health competence? Health Qual. Life Outcomes 2019, 17, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grewal, H.; Sapawat, P.; Modi, P.; Aggarwal, S. Psychological impact of orthodontic treatment on quality of life—A longitudinal study. Int. Orthod. 2019, 17, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasoud, N.N. Pain perception among patients treated with passive self-ligating fixed appliances and Invisalign® aligners during the first week of orthodontic treatment. Korean J. Orthod. 2018, 48, 326–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johal, A.; Ashari, A.B.; Alamiri, N.; Fleming, P.S.; Qureshi, U.; Cox, S.; Pandis, N. Pain experience in adults undergoing treatment: A longitudinal evaluation. Angle Orthod. 2018, 88, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Pereira, C.; Brandelli, J.; Flores-Mir, C. Patient satisfaction and quality of life changes after Invisalign treatment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2018, 153, 834–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Cha, J.Y.; Lee, K.J.; Yu, H.S.; Hwang, C.J. Changes in psychological health, subjective food intake ability and oral health-related quality of life during orthodontic treatment. J. Oral Rehabil. 2017, 44, 860–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, R.F.; Ramos-Jorge, J.; Marques, L.S.; de Paiva, S.M.; Melgaço, C.A.; Pazzini, C.A. Prospective evaluation of the psychosocial impact of the first 6 months of orthodontic treatment with fixed appliance among young adults. Angle Orthod. 2016, 86, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Feng, Z.-C.; Liu, X.; Li, Z.-M.; Cai, B.; Wang, D.-W. Impact of malocclusion on oral health-related quality of life in young adults. Angle Orthod. 2015, 85, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johal, A.; Alyaqoobi, I.; Patel, R.; Cox, S. The impact of orthodontic treatment on quality of life and self-esteem in adult patients. Eur. J. Orthod. 2015, 37, 233–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujiyama, K.; Honjo, T.; Suzuki, M.; Matsuoka, S.; Deguchi, T. Analysis of pain level in cases treated with Invisalign aligner: Comparison with fixed edgewise appliance therapy. Prog. Orthod. 2014, 15, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalish, M.; Cooper-Kazaz, R.; Ivgi, I.; Canetti, L.; Tsur, B.; Bachar, E.; Chaushu, S. Adult patients’ adjustability to orthodontic appliances. Part I: A comparison between Labial, Lingual, and Invisalign™. Eur. J. Orthod. 2012, 34, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohoff, A.; Stamm, T.; Goder, G.; Sauerland, C.; Ehmer, U.; Seifert, E. Comparison of 3 bonded lingual appliances by auditive analysis and subjective assessment. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 124, 737–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohoff, A.; Seifert, E.; Fillion, D.; Stamm, T.; Heinecke, A.; Ehmer, U. Speech performance in lingual orthodontic patients measured by sonagraphy and auditive analysis. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2003, 123, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varela, M.; García-Camba, J.E. Impact of orthodontics on the psychologic profile of adult patients: A prospective study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 1995, 108, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Maroto, M.; Santos-Puerta, N.; Olmo, M.J.G.; Peñacoba-Puente, C. The impact of dental appearance and anxiety on self-esteem in adult orthodontic patients. Orthod. Craniofacial Res. 2015, 18, 143–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, L.; Ryan, F.S.; Christensen, L.R.; Cunningham, S.J. Factors influencing satisfaction with the process of orthodontic treatment in adult patients. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofacial. Orthop. 2018, 153, 362–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johal, A.; Damanhuri, S.H.; Colonio-Salazar, F. Adult orthodontics, motivations for treatment, choice, and impact of appliances: A qualitative study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2024, 166, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).