Establishment and Evaluation of Nomogram Model for Predicting the Risk of Arteriovenous Fistula Dysfunction in Patients Undergoing MHD

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

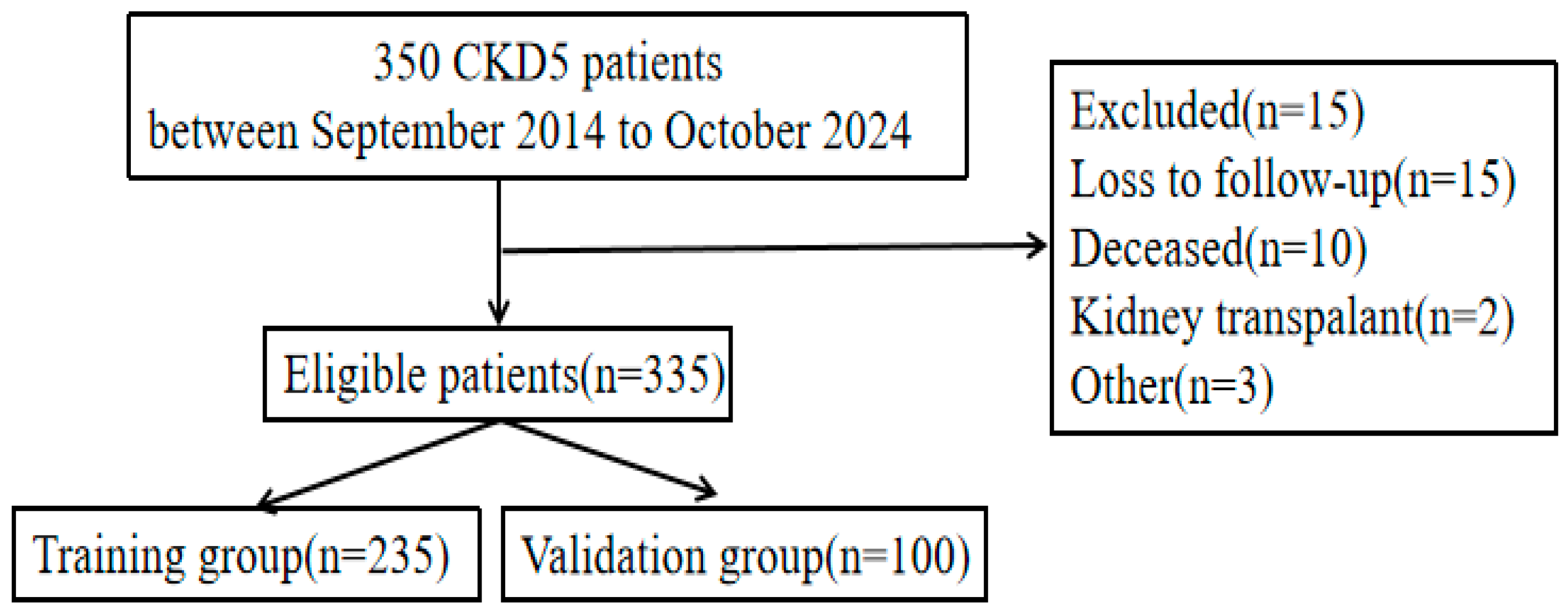

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Methods

2.3. Criteria for Selection

2.4. AVF Functional Assessment: Methodology and Criteria

2.5. Observational Indicators

2.5.1. Data Collection

2.5.2. Laboratory Indicators

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. The Baseline Data and Clinical Indicators of Patients in the Modeling Group

3.2. Collinearity Assessment

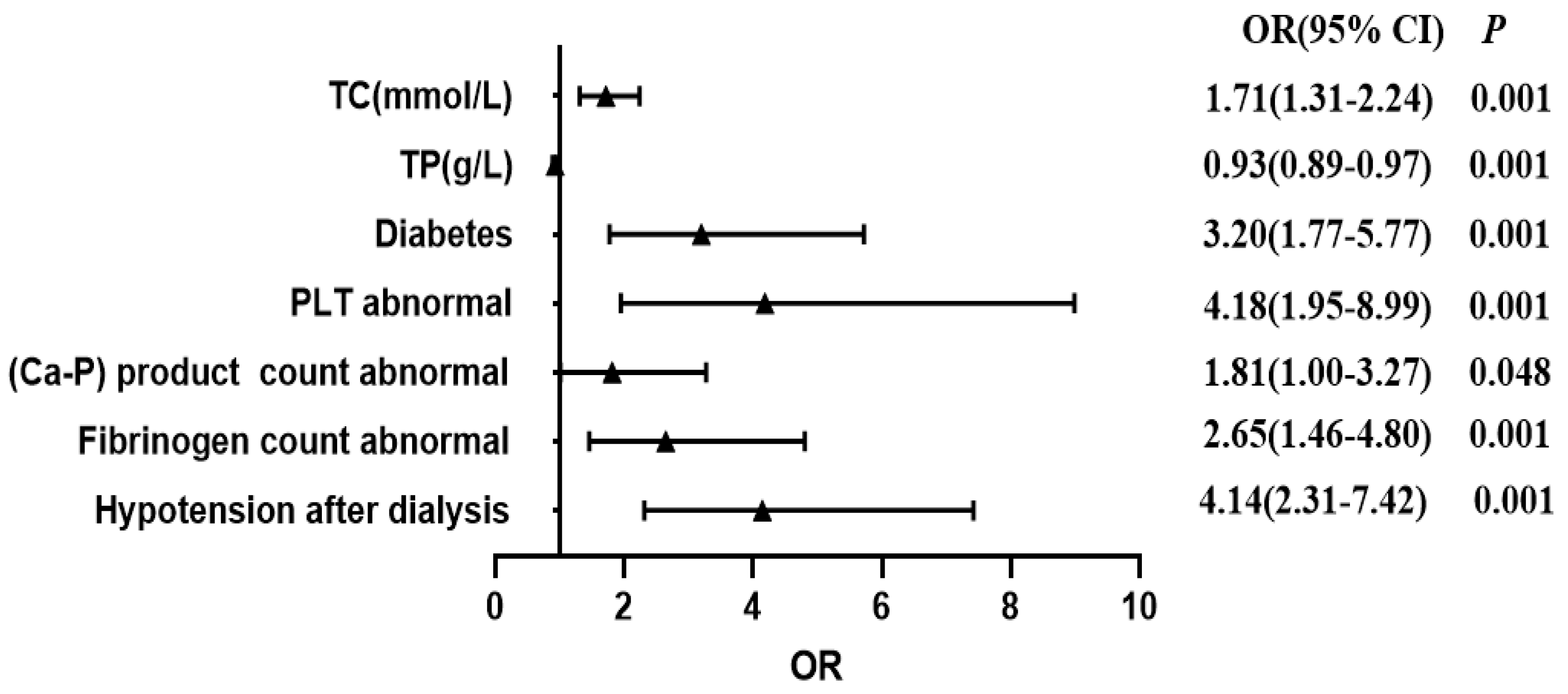

3.3. Analysis of Risk Factors for Arteriovenous Fistula Dysfunction in the Modeling Group

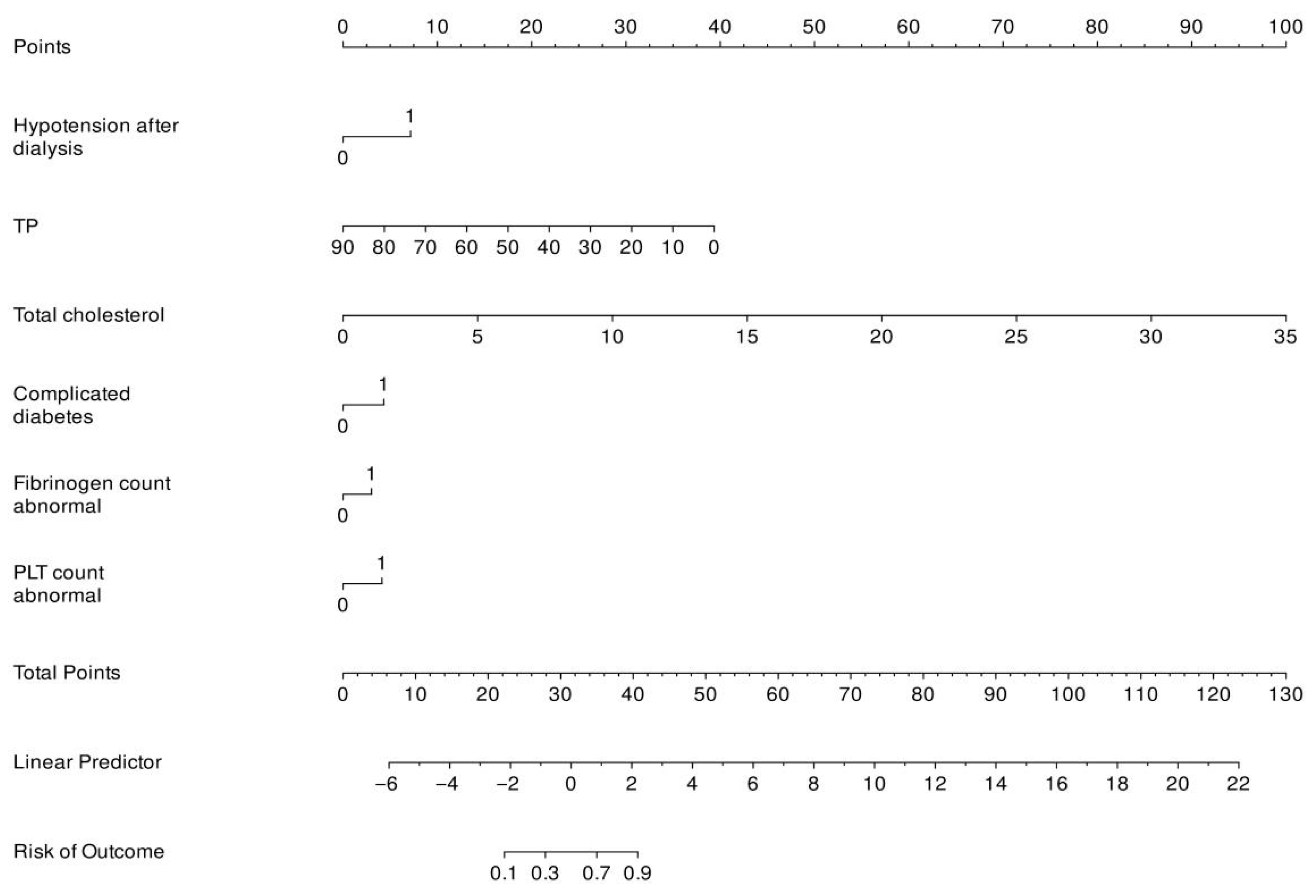

3.4. Establishing a Predictive Model for AVF Dysfunction

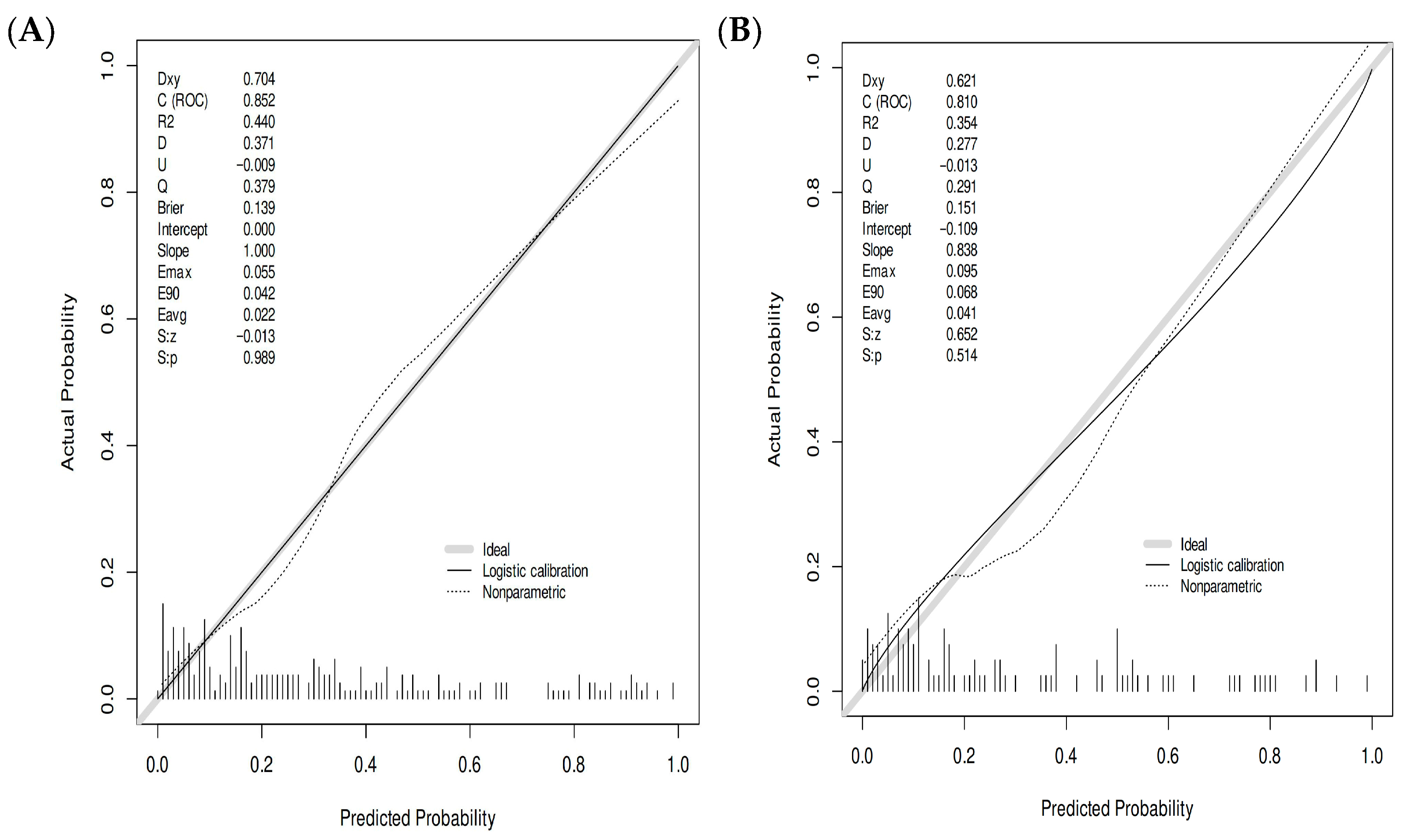

3.5. Internal Validation of the AVF Dysfunction Risk Prediction Model

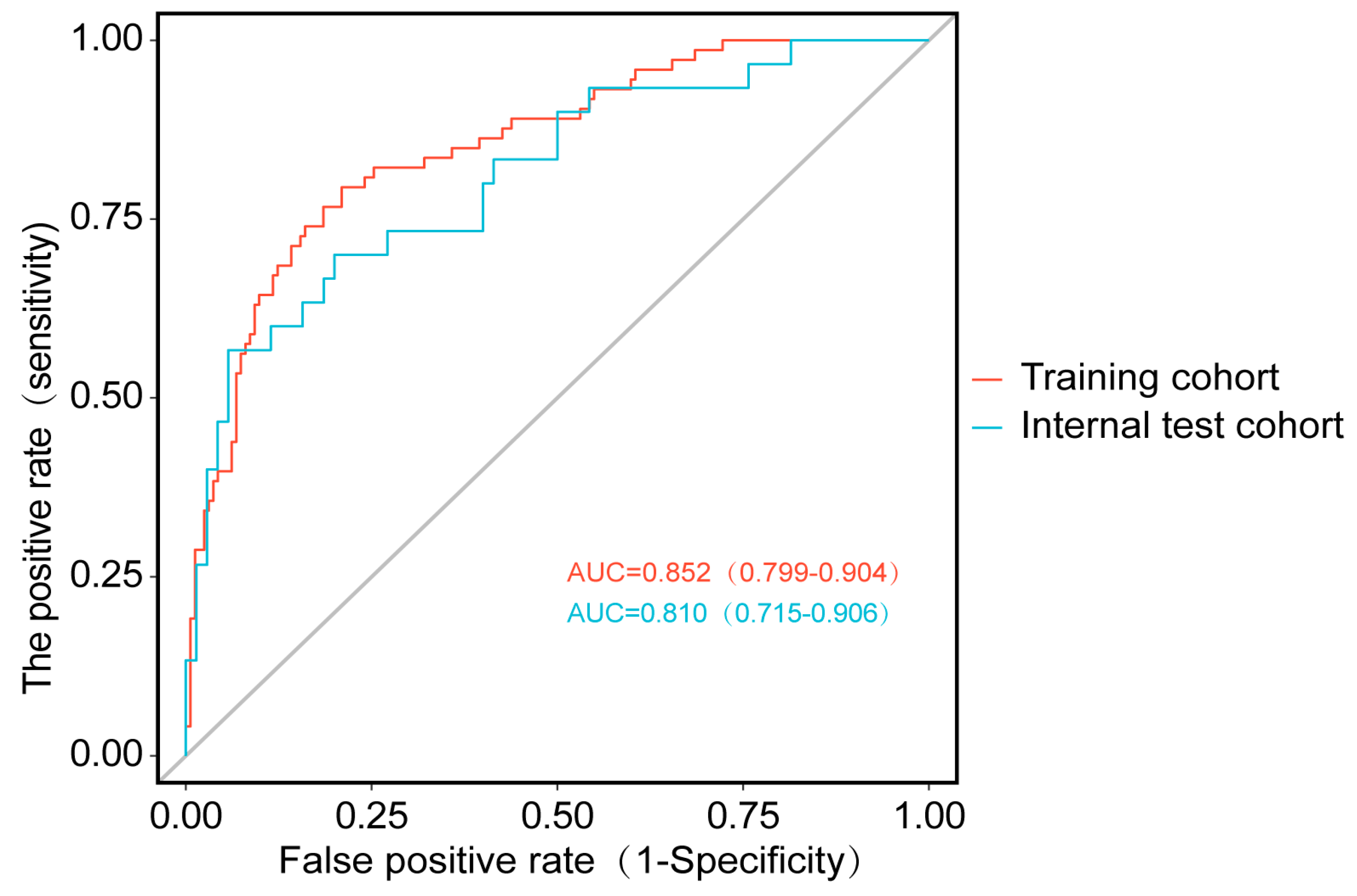

3.5.1. Discriminative Ability Assessment

3.5.2. Calibration Performance Assessment

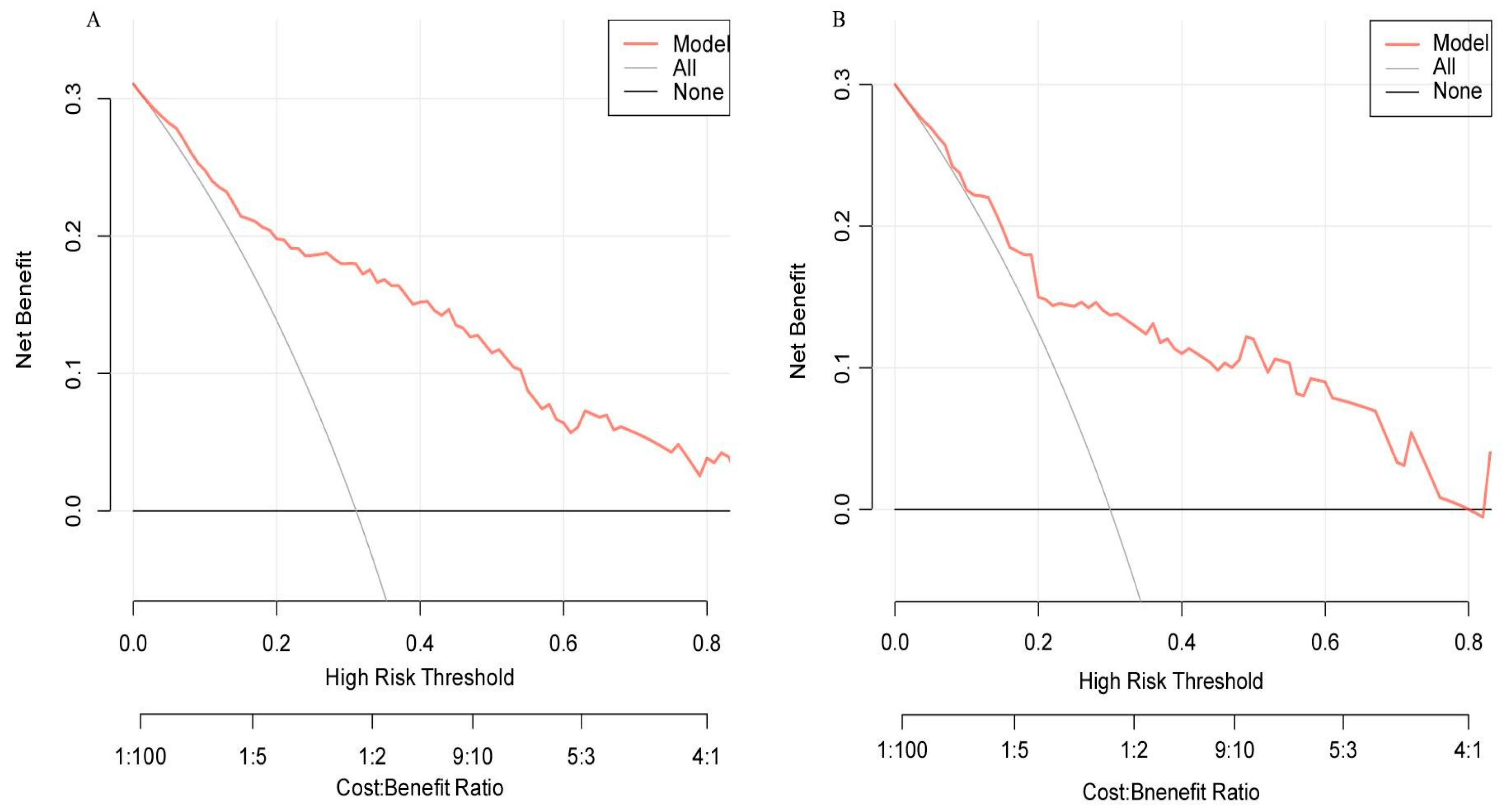

3.5.3. Clinical Applicability Assessment

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MHD | Hemodialysis |

| AVF | Arteriovenous fistula |

| ROC | Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve |

| TC | Cholesterol |

| PLT | Platelet |

| Alb | Albumin |

| TP | Total Protein |

References

- Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Wang, L.; Wang, W.; Liu, B.; Liu, J.; Chen, M.; He, Q.; Liao, Y.; Yu, X.; et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in China: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2012, 379, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravani, P.; Palmer, S.C.; Oliver, M.J.; Quinn, R.R.; MacRae, J.M.; Tai, D.J.; Pannu, N.I.; Thomas, C.; Hemmelgarn, B.R.; Craig, J.C.; et al. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: A systematic review. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2013, 24, 465–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besarab, A.; Frinak, S.; Margassery, S.; Wish, J.B. Hemodialysis Vascular Access: A Historical Perspective on Access Promotion, Barriers, and Lessons for the Future. Kidney Med. 2024, 6, 100871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Zou, C.; Liu, L.; He, T.; Sun, C.; Gan, X.; Tian, X.; Yuan, L. Analysis of arteriovenous fistula failure factors and construction of nomogram prediction model in patients with maintenance hemodialysis. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2500665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bashar, K.; Conlon, P.J.; Kheirelseid, E.A.; Aherne, T.; Walsh, S.R.; Leahy, A. Arteriovenous fistula in dialysis patients: Factors implicated in early and late AVF maturation failure. Surgeon 2016, 14, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbin, M.L.; Greene, T.; Allon, M.; Dember, L.M.; Imrey, P.B.; Cheung, A.K.; Himmelfarb, J.; Huber, T.S.; Kaufman, J.S.; Radeva, M.K.; et al. Prediction of arteriovenous fistula clinical maturation from postoperative ultrasound measurements: Findings from the hemodialysis fistula maturation study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2018, 29, 2735–2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Cui, W.; Wang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhu, L.; Bian, C.; Luo, T. Prognostic nomogram for the patency of wrist autologous arteriovenous fistula in first year. iScience 2024, 27, 110727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhan, S.; Yu, P. Nomogram-based prediction of the risk of AVF maturation: A retrospective study. Front. Med. 2024, 11, 1432437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy-Cuadros, M.; Yilmaz, S.; Salazar-Bañuelos, A.; Doig, C. Risk factors associated with patency loss of hemodialysis vascular access within 6 months. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2010, 5, 1787–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Fan, Y.; Li, J.; Qi, X.; Li, X.; Li, H. Construction of Risk-Prediction Models for Autogenous Arteriovenous Fistula Thrombosis in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Blood Purif. 2024, 53, 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, J.; Cai, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, M.; Pan, M.; Zhang, P. Development and validation of a risk prediction model for autologous arteriovenous fistula thrombosis in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Ren. Fail. 2025, 47, 2477832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkhumpornpat, C.; Boonchieng, E.; Chouvatut, V.; Lipsky, D. FLEX-SMOTE: Synthetic over-sampling technique that flexibly adjusts to different minority class distributions. Patterns 2024, 5, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, S.; Ma, G.; Dong, Y.; Zhao, M.; Chen, L.; Qi, W.; Shen, H. Systematic review of risk prediction models for arteriovenous fistula dysfunction in maintenance hemodialysis patients. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Li, J.; Ding, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, M.; Xu, J. Relationship between effective blood flow rate and clinical outcomes in maintenance hemodialysis patients: A single-center study. Ren. Fail. 2024, 46, 2344655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Cao, Y.; Lan, X.; Hu, X.; Mou, F.; Chen, H.; Gong, X.; Li, L.; Tang, S.; et al. Nomogram for Predicting Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Response in Breast Cancer Using MRI-based Intratumoral Heterogeneity Quantification. Radiology 2025, 315, e241805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, J.; Zhong, H.; Jiang, M.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S. Development of a nomogram for predicting myopia risk among school-age children: A case-control study. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2331056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhou, R.; Yu, D.; Chen, D.; Zhao, A. A nomogram and risk stratification to predict subsequent pregnancy loss in patients with recurrent pregnancy loss. Hum. Reprod. 2024, 39, 2221–2232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, J.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, P.; Zhao, D. Development and validation of a nomogram to predict the depressive symptoms among older adults: A national survey in China. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 361, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhu, S.; Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Mo, X.; Xu, W.; Xu, Z. Development, validation, and visualization of a novel nomogram to predict depression risk in patients with stroke. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 365, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, P.; Huang, L.; Wang, X.; Wen, Z.; Luo, Y.; Xu, F. Machine learning-based prediction model for arteriovenous fistula thrombosis risk: A retrospective cohort study from 2017 to 2024. BMC Nephrol. 2025, 26, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.C.; Tian, K.; Zhang, Y.T. Nomogram for Predicting Early AVF Failure in Elderly Diabetic Patients: Methodological and Clinical Considerations [Letter]. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 2025, 18, 677–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, R.M.; Calabrese, V.; Zirino, F.; Lipari, A.; Giuffrida, A.E.; Sessa, C.; Galeano, D.; Alessandrello, I.; Distefano, G.; Scollo, V.; et al. Platelet-To-Lymphocyte Ratio and Arteriovenous Fistula for Hemodialysis: An Early Marker to Identify AVF Dysfunction. G. Ital. Nefrol. 2024, 41, 2024-vol6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Min, Y.; Tu, C.; Wan, S.; Zhu, Q.; Chen, J.; Qiu, W.; Jiang, N.; Li, H. The Prognosis of Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients with Various Types of Vascular Access in Hemodialysis Centers in Wuhan: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Int. J. Nephrol. 2025, 2025, 5865205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Jiang, P. Risk factors for coronary artery calcification in Chinese patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: A meta-analysis. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 2025, 57, 3307–3318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grosu, I.D.; Stirbu, O.; Schiller, A.; Bob, F. Arterio-Venous Fistula Calcifications-Risk Factors and Clinical Relevance. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ushinsky, A.; Kiani, A.Z.; Shenoy, S. Intravascular Arterial Lithotripsy of Medial Calcinosis Causing Low Flow in Dialysis Arteriovenous Fistulas. J. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2025, 36, 1730–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudlou, F.; Tayebi, P.; Moghadamnia, A.A.; Bijani, A. An investigation of the Effect of Antihypertensive drugs on Arteriovenous Fistula Maturation in Patients with Hemodialysis. Casp. J. Intern. Med. 2025, 16, 500–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachid, A.; Chaaban, B.; Mohammed, M.; Kazma, H.; Khalil, N.H.M. Severe Left Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction Following Arteriovenous Fistula Reopening in a Dialysis Patient with Left Ventricular Hypertrophy. Cureus 2025, 17, e81284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, Ö.; Arslan, Ü. Sex-Specific Impact of Inflammation and Nutritional Indices on AVF Blood Flow and Maturation: A Retrospective Analysis. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Wang, R.; Ma, T.; Lei, Q.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Cheng, J. Association between preoperative C-reactive protein to albumin ratio and late arteriovenous fistula dysfunction in hemodialysis patients: A cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, Y.; He, X.; Li, X. Construction and Evaluation of a Predictive Nomogram for Identifying Premature Failure of Arteriovenous Fistulas in Elderly Diabetic Patients. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2024, 17, 4825–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, J.; Xue, X.; Wu, H. Risk prediction models for autogenous arteriovenous fistula failure in maintenance hemodialysis patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J. Surg. 2024, 48, 2526–2542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Dysfunction Group (n = 103) | Non-Dysfunction Group (n = 232) | t/Z/χ2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 57.75 ± 13.66 | 58.20 ± 14.78 | −0.266 | 0.790 | |

| Height (cm) | 164.08 ± 0.90 | 165.62 ± 7.93 | −1.649 | 0.100 | |

| Sex | Male | 64 (62%) | 136 (59%) | 0.366 | 0.545 |

| Female | 39 (38%) | 96 (41%) | |||

| CO2CP (mmol/L) | 23.09 ± 4.18 | 21.19 ± 3.10 | 4.615 | 0.001 | |

| Uric acid (mmol/L) | 455.92 (388.89, 529.12) | 396.91 (315.94, 496.29) | −6.170 | 0.001 | |

| Total Protein (g/L) | 64.84 ± 10.59 | 67.54 ± 5.39 | −3.093 | 0.002 | |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.05 ± 0.24 | 0.99 ± 0.29 | 1.937 | 0.054 | |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 2.17 ± 0.63 | 2.10 ± 0.71 | 0.779 | 0.437 | |

| Hs-CRP (mg/L) | 10.20 ± 18.59 | 6.59 ± 13.25 | 2.018 | 0.044 | |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 266.66 ± 90.90 | 220.93 ± 160.06 | 2.271 | 0.024 | |

| Calcium (mmol/L) | 2.26 ± 0.21 | 2.24 ± 0.19 | 0.550 | 0.583 | |

| Phosphorus (mmol/L) | 1.91 ± 0.58 | 1.97 ± 0.58 | −0.953 | 0.341 | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 37.67 ± 5.05 | 37.079 ± 4.10 | 1.130 | 0.259 | |

| Glucose (mmol/L) | 7.53 ± 4.66 | 7.73 ± 3.89 | −0.394 | 0.694 | |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 4.74 ± 0.66 | 4.71 ± 0.60 | 0.868 | 0.386 | |

| Hematocrit (%) | 0.69 ± 3.365 | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 1.570 | 0.117 | |

| BUN (mmol/L) | 22.48 ± 8.41 | 23.31 ± 7.09 | −0.930 | 0.353 | |

| Cretine (μmol/L) | 976.04 ± 331.89 | 995.22 ± 286.53 | −0.538 | 0.591 | |

| Aspartate transaminase (g/L) | 15.69 ± 7.56 | 16.52 ± 9.01 | −0.810 | 0.419 | |

| Alanine transaminase (μ/L) | 12.89 ± 6.34 | 14.51 ± 10.90 | −1.403 | 0.161 | |

| Total Iron Binding Capacity (mmol/L) | 10.89 ± 4.31 | 10.95 ± 3.91 | −0.133 | 0.894 | |

| Triglyceride (g/L) | 2.04 ± 1.613 | 1.83 ± 1.525 | 1.156 | 0.248 | |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.20 (2.34, 4.01) | 3.82 (3.32, 4.30) | −4.682 | 0.001 | |

| LLDL (mmol/L) | 2.42 ± 1.68 | 2.05 ± 0.72 | 2.847 | 0.005 | |

| DHDL (mmol/L) | 1.07 ± 0.35 | 0.99 ± 0.29 | 2.297 | 0.022 | |

| Fibrinogen count (g/L) | Normal | 31 (30%) | 126 (54%) | 16.794 | 0.001 |

| Abnomal | 72 (70%) | 106 (46%) | |||

| Complicated diabetes | Yes | 55 (54%) | 54 (23.3%) | 29.485 | 0.001 |

| No | 48 (46%) | 178 (77.0%) | |||

| Platelet count (×109/L) | Normal | 31 (30%) | 126 (54%) | 16.794 | 0.001 |

| Abnromal | 72 (70%) | 106 (45.6%) | |||

| (Ca-P) product count | Normal | 31 (30%) | 126 (54%) | 16.794 | 0.001 |

| Abnormal | 72 (70%) | 106 (46%) | |||

| Hypotension after dialysis | Yes | 70 (68%) | 77 (33.2%) | 35.022 | 0.001 |

| No | 33 (32%) | 155 (66.8%) |

| Item | Tolerance | VIF |

|---|---|---|

| Hypotension after dialysis | 0.947 | 1.056 |

| Fibrinogen abnormal | 0.968 | 1.033 |

| (Ca-P) product count abnormal | 0.980 | 1.021 |

| PLT abnormal | 0.989 | 1.012 |

| Complicated diabetes | 0.933 | 1.072 |

| TP (g/L) | 0.995 | 1.006 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 0.972 | 1.029 |

| Item | Assignment |

|---|---|

| Hypotension after dialysis | 1: Yes; 0: No |

| Fibrinogen abnormal | 1: Yes; 0: No |

| (Ca-P) product count abnormal | 1: Yes; 0: No |

| PLT abnormal | Continuity variables |

| Complicated diabetes | 1: Yes; 0: No |

| TP (g/L) | Continuity variables |

| TC (mmol/L) | Continuity variables |

| Item | β | SE | Wald | p | OR | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypotension after dialysis | 1.421 | 0.298 | 22.765 | 0.001 | 4.141 | 2.310–7.422 |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 0.937 | 0.304 | 10.217 | 0.001 | 2.645 | 1.457–4.802 |

| (Ca-P) product count | 0.594 | 0.301 | 3.899 | 0.048 | 1.812 | 1.004–3.267 |

| PLT (×109/L) | 1.431 | 0.390 | 13.433 | 0.001 | 4.182 | 1.946–8.988 |

| Complicated diabetes | 1.161 | 0.302 | 14.810 | 0.001 | 3.194 | 1.768–5.772 |

| TP (g/L) | −0.076 | 0.022 | 11.597 | 0.001 | 0.927 | 0.887–0.968 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 0.538 | 0.136 | 15.570 | 0.001 | 1.712 | 1.311–2.237 |

| Model | Group | AUC | SE | SP | Cut-off | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LR | training | 0.852 (0.799–0.904) | 0.866 | 0.722 | 0.355 | 0.646 | 0.870 |

| validation | 0.810 (0.715–0.906) | 0.867 | 0.768 | 0.392 | 0.619 | 0.930 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, D.; Sun, L.; Wang, M.; Han, Y.; Liao, Y.; Wang, L.; Fu, X. Establishment and Evaluation of Nomogram Model for Predicting the Risk of Arteriovenous Fistula Dysfunction in Patients Undergoing MHD. Healthcare 2025, 13, 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233161

Jiang D, Sun L, Wang M, Han Y, Liao Y, Wang L, Fu X. Establishment and Evaluation of Nomogram Model for Predicting the Risk of Arteriovenous Fistula Dysfunction in Patients Undergoing MHD. Healthcare. 2025; 13(23):3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233161

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Dan, Ling Sun, Minghui Wang, Yahui Han, Youfen Liao, Ling Wang, and Xia Fu. 2025. "Establishment and Evaluation of Nomogram Model for Predicting the Risk of Arteriovenous Fistula Dysfunction in Patients Undergoing MHD" Healthcare 13, no. 23: 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233161

APA StyleJiang, D., Sun, L., Wang, M., Han, Y., Liao, Y., Wang, L., & Fu, X. (2025). Establishment and Evaluation of Nomogram Model for Predicting the Risk of Arteriovenous Fistula Dysfunction in Patients Undergoing MHD. Healthcare, 13(23), 3161. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13233161