Abstract

Background: Poor nutrition drives chronic disease, health disparities, and rising health care costs in the United States. Medically tailored meals (MTMs), designed by registered dietitians, are a Food-as-Medicine intervention with potential to improve outcomes and reduce costs. This review synthesizes evidence on the clinical, economic, and policy implications of MTMs. Methods: We conducted a narrative review of peer-reviewed studies, real-world program evaluations, and policy analyses. Sources included PubMed, Google Scholar, and grey literature from government, nonprofit, and industry organizations. Articles and reports were included if they examined MTMs in Medicare, Medicaid, or other high-risk populations. Results: Evidence demonstrates that MTMs improve health outcomes, reduce hospitalizations, and lower total cost of care. Case studies from Medicaid and Medicare Advantage plans, including those administered by Mom’s Meals®, report reductions in emergency department visits, hospital readmissions, and total cost of care, alongside sustained high member satisfaction. Despite these findings, gaps in coverage and limited stakeholder awareness hinder broader access and adoption. Conclusions: Federal policy action can expand MTM availability and maximize utilization of existing benefits. Opportunities include establishing a Medicare Fee-for-Service demonstration, expanding and encouraging use in Medicare Advantage, and leveraging MTMs within Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation models. Broader implementation and utilization could reduce the nation’s chronic disease burden, advance health equity, and promote value-based care.

1. Background

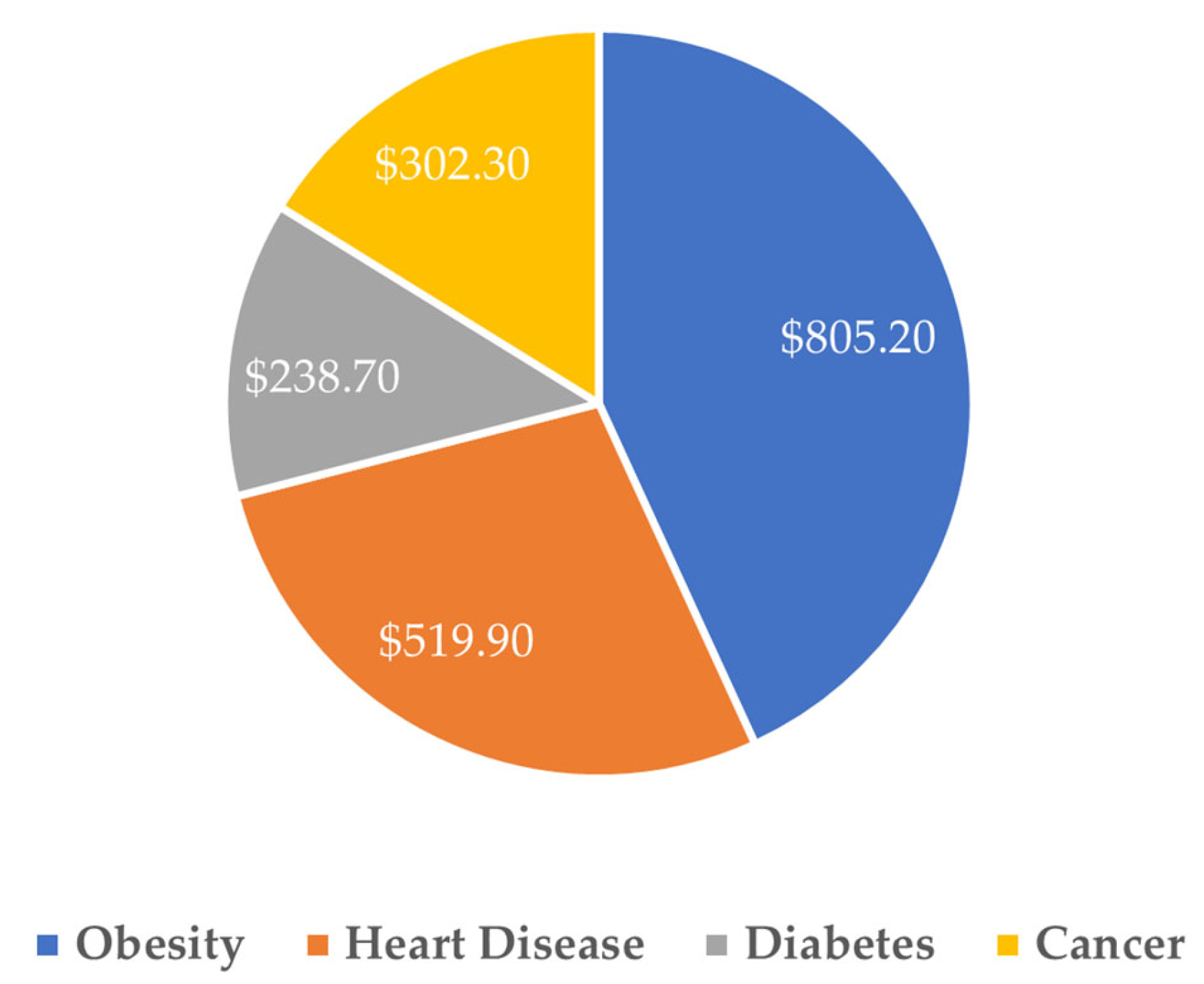

The role of poor nutrition in driving higher health care costs and poor outcomes has moved beyond debate. Inadequate nutrition has a multiplying effect in driving not only the costliest health care conditions and comorbidities but also the mortality rates associated with them, contributing to the nation’s leading causes of death, including heart disease (680,981 deaths), cancer (613,352), stroke (162,639), and diabetes (95,190) annually [1]. The American Action Forum recently quantified the estimated total cost due to treatment and lost productivity of four nutrition-impacted chronic conditions, finding that annual costs in 2020 totaled more than $1.8 trillion dollars as shown in Figure 1 [2].

Figure 1.

Total cost due to treatment and lost productivity, nutrition-impacted chronic conditions, 2020 (billions) [2]. Reproduced with permission from American Action Forum, The Economic Costs of Poor Nutrition; published by American Action Forum, 2022 [2].

Medicare-aged beneficiaries are among the most impacted populations in terms of nutrition-responsive issues, and it is estimated that 95% of older adults manage at least one chronic health care condition [3], while rates of adherence to dietary guidelines related to these conditions remain low. More than 50% of older adults are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition, which is associated with poorer health outcomes [4].

Food-insecure older adults, aged 60 and over, are 53% more likely to suffer a heart attack, 40% more likely to suffer from congestive heart failure, and 52% more likely to develop asthma [5]. From a cost perspective, food-insecure adults with chronic diseases have higher health care costs. One study found the incremental costs associated with food insecurity among older adults with a chronic condition ranged from $530 (cancer) to $1740 (arthritis) per person per year (2015 USD) [6]. The scale of the nutrition burden on Medicare-aged patients is clear. Together, poor nutrition and nutrition insecurity are meaningful drivers of higher health care cost and poor outcomes, with a disproportionate impact on government-sponsored insurance markets and historically marginalized communities [3,5].

While progress has been made in developing condition-specific nutrition interventions, a continued lack of access to and lack of utilization of these interventions threatens to both increase health care costs, estimated at $16 billion annually, including about $1800 in excess costs per affected adult, and hinder efforts to curtail rising rates of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [2,4,6]. Medically tailored meals (MTMs), designed to address individual clinical needs, offer a cost-effective strategy to improve outcomes and reduce avoidable utilization. However, their integration into federal programs remains inconsistent and underutilized [7]. Our review is particularly timely because of the growing role of nutrition in chronic disease prevention, alongside renewed federal interest in Food-is-Medicine (FIM) models, which has accelerated efforts to integrate MTMs into health care policy and practice. A narrative review is needed to synthesize emerging clinical and economic findings and to translate them into actionable policy opportunities.

This narrative review synthesizes peer-reviewed literature and real-world evaluations to assess the clinical and economic impacts of MTMs. Considering the growing burden of nutrition-related chronic disease and ongoing budgetary pressures, we examine the potential of MTMs as a scalable, evidence-based solution. We also explore policy pathways, including Medicare Fee-for-Service (FFS) demonstrations, Medicare Advantage (MA) FIM benefit models and expanded use within Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) programs, that could increase access and impact.

2. Methods

This paper is a narrative review intended to synthesize the existing peer-reviewed evidence, real-world program evaluations, and relevant policy analyses on MTMs. The purpose of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the clinical, economic, and policy implications of MTMs and to identify policy solutions to leverage the clinical and cost advantages of MTMs.

To identify relevant literature, we conducted searches of PubMed and Google Scholar for English-language publications through July 2025, using unstructured combinations of the following terms: “medically tailored meals”, “food is medicine”, “nutrition interventions”, “Medicare”, “Medicaid”, “health care utilization”, and “cost savings”. Roughly 30 sources of information were examined to provide a broad overview of available evidence.

We included studies and reports that examined MTMs in U.S. populations with diet-sensitive chronic conditions, post-discharge care, or high-risk Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, and that reported on clinical, utilization, or economic outcomes. Non-tailored nutritional interventions (e.g., general meal delivery not linked to medical need) were excluded.

In addition to peer-reviewed studies, we incorporated grey literature such as government reports, nonprofit white papers, and health plan evaluations. These sources were included because they represent some of the only available data on specific MTM implementations and provide timely and practical insights for policy discussions. Given the narrative design, no formal protocol or quality assessment was undertaken. Instead, the emphasis was on breadth of coverage and synthesis of evidence to inform future policy and research directions.

3. Results

3.1. Cost Savings of Medically Tailored Meals

In addressing the gap in adequate nutrition, MTMs have become a common offering in Medicaid and MA plans. MTMs are differentiated from other forms of FIM in that they are designed by a registered dietitian (RD) in order to alleviate or prevent a medical event through the provision of customized meals or menus. For example, a patient with kidney disease may receive meals lower in phosphorus and potassium, while a cardiac patient may receive meals lower in sodium or certain fats.

The Bipartisan Policy Center has estimated that $1.57 is saved for every dollar invested in MTMs for Medicare beneficiaries with certain chronic conditions through reductions in hospital readmissions post-discharge [8]. In Medicaid, it is estimated that spending is $712 lower per month for enrollees with chronic diseases who received two MTMs per day, 5 days a week, for an average of 12 months. Savings are primarily due to reductions in inpatient hospital and skilled nursing facility stays [9].

Furthermore, recently completed health plan case studies which leverage data from Mom’s Meals® MTM programs delivered in partnership with AmeriHealth Caritas District of Columbia and a Medicaid Plan in California and that are considered grey literature show that MTMs are a cost-effective method to reduce hospital readmissions, total cost of care, and emergency department (ED) utilization, reporting up to a $10 million total cost reduction and 20% fewer readmissions in post-discharge participants, all while maintaining high member satisfaction [10].

3.2. Clinical, Observational and Health Policy Modeling Evidence for Medically Tailored Meals

In addition to plan-specific case studies, evidence illustrating the impact of MTMs is diverse in terms of use cases and conditions treated. As summarized in Table 1 [9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27], recent clinical studies, health policy modeling, and health plan cohort analyses have quantified the health impact of MTM interventions. These analyses typically focus on MTMs used as part of either chronic condition treatment or following an acute event, with meaningful impact on overall spend, ED visits, inpatient hospital utilization, clinical status, and other measures of patient well-being.

Table 1.

Summary of clinical, observational, and modeled evidence for chronic care, post-discharge, and long-term care medically tailored meals programs.

These real-world case studies, modeled health policy studies, cohort analyses, and published clinical evidence illustrate the meaningful and specific impact that MTMs can have on a wide array of beneficiaries, and further the need for national policymaking to leverage the benefit of MTMs for a broader population.

3.3. Barriers to Medically Tailored Meals Access

Despite the established benefits of MTMs, particularly for Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, many barriers exist to widespread availability in the form of coverage gaps and awareness of FIM benefits. Addressing these barriers to access represents a meaningful opportunity to drive improved health outcomes for Americans.

Table 2 highlights the coverage barriers for MTMs in the context of Medicare FFS, MA, and state Medicaid plans [28]. Addressing these access gaps will require legislative or regulatory action on the part of policymakers and are likely to be dependent on a refined view of implementation and program design considerations.

Table 2.

Medically tailored meals benefit availability gaps.

In addition to a lack of coverage and access to MTM benefits, there remain meaningful gaps in the awareness of FIM and MTMs among key health care stakeholders. According to a recent national survey, knowledge of specific MTM offerings and coverage remains below 30% [32]. Yet, after learning what MTMs are, more than half of respondents expressed interest in participating, indicating a significant mismatch between knowledge and demand. This imbalance highlights a nearly two-to-one gap between the public’s enthusiasm for MTM participation and their baseline awareness of such programs.

These barriers represent meaningful challenges related to the scalability of MTM and FIM benefits, which will need to be addressed with specific legislative and regulatory solutions, as well as opportunities, which could yield innovative solutions from within or for the health care industry. Progress toward addressing these barriers and solutions will be necessary to ensure population-wide nutrition improvement.

4. Discussion

Based on this review of literature, there is both clinical and economic promise of MTMs across a range of populations and care settings. But despite these consistent findings, the benefits of MTMs remain unevenly realized due to coverage gaps, inconsistent implementation, and limited awareness among patients, providers, and policymakers. Specifically, we outline policy pathways that can translate the evidence base into sustained, equitable access to MTMs. By situating MTMs within federal programs, aligning benefits with clinical needs, and ensuring adequate awareness and uptake, policymakers can help unlock the full potential of this intervention to improve health outcomes, reduce costs, and advance health equity.

4.1. Policy Solutions to Leverage the Clinical and Cost Advantages of Medically Tailored Meals

4.1.1. Medicare FFS Demonstration for MTM

Under a four-year model, which aligns with bipartisan bills under consideration in the House and Senate, hospitals and clinicians would prescribe home-delivered MTMs to targeted Medicare FFS populations. This model would align with bipartisan legislation introduced in the Senate [33] and similar bipartisan legislation passed out of the House Ways and Means Committee [34] in the 118th Congress and reintroduced in the 119th Congress through the Medically Tailored Home-Delivered Meals Demonstration Pilot Act [35]. Unlike the legislation under consideration in Congress that applies only to Medicare Part A providers, this recommended model would apply to Part A and Part B providers. Availability under both Part A and Part B would allow for greater coordination and improved clinical outcomes in ongoing care, while also allowing the Innovation Center to explore which provider settings may offer the most beneficial outcomes in terms of both health improvements and cost savings. Key elements would include:

- Eligible beneficiaries: Eligible beneficiaries would include those who: (1) have one or more chronic disease(s); (2) are post-discharge; (3) are at risk for entering an institutional care setting; and/or (4) have limitations in activities of daily living (ADL).

- Eligible providers: Eligible providers would include inpatient and outpatient hospitals, as well as clinical group practices that have performed well historically in Medicare quality programs.

- Quality measures: Quality measures would assess reductions in: (1) all-cause inpatient admissions; (2) all-cause inpatient readmissions; (3) ED visits; and (4) post-acute institutional care.

- Cost measures: A cost measure would assess the reduction in total cost-of-care.

- Adherence to national nutrition guidelines: Home-delivered MTMs would have to adhere with the current and future Dietary Guidelines for Americans, which reflect standards for high-quality nutrition [36].

- No or minimal cost-sharing: Beneficiaries would not have any cost-sharing obligations for the home-delivered MTMs provided in the model or, in the alternative, may have modest cost sharing obligations, in order to encourage the widest possible participation to ensure a true test of the model.

- Awareness: By launching the program with providers instead of managed care plans, awareness among providers would be necessary, which would lead to greater member awareness. In addition to training, availability of information about MTM programs in provider electronic health records would further facilitate awareness of and timely discussions about, and patient referrals into, available MTM programs.

4.1.2. Medicare Advantage High-Value FIM Benefit Model

Under the multi-year model, MA plans would be able to provide high-value home-delivered MTMs or other evidence-based FIM interventions to targeted MA populations, such as duals and those living with chronic disease. Beneficiaries would actively engage with their providers to choose home-delivered MTMs or the combinations of solutions that best meet their individual health needs to advance their overall health and well-being at a lower cost to Medicare. The inclusion of healthcare providers in the program could drive higher utilization of MTMs than is seen in MA supplemental benefits programs today by overcoming the member awareness barrier. Key elements of the model would include:

- High-value benefit design: MA plans would work with contracted food providers to offer home-delivered MTMs and/or other FIM solutions that adhere to national nutrition standards (the current and future Dietary Guidelines for Americans) to at-risk MA enrollee populations at little or no cost at durations that extend beyond the current MA supplemental or Special Supplemental Benefits for the Chronically Ill limitations.

- Eligible beneficiaries: Beneficiaries electing to receive FIM benefit could include those who: (1) have one or more chronic disease(s); (2) are dual-eligible; (3) are post-discharge; (4) are at risk for entering an institutional care setting; and/or (5) have ADL limitations.

- Value assessment: MA plans and Medicare would share in savings from reductions in total cost-of-care spending. Quality measures would assess reductions in: (1) all-cause inpatient admissions; (2) all-cause inpatient readmissions; (3) ED visits; and (4) post-acute institutional care.

4.1.3. Use of FIM Benefits in Current CMMI Models

Certain models currently overseen by the Innovation Center allow for the provision of home-delivered MTMs—but not all participating entities (e.g., health systems, accountable care organizations, or state Medicaid agencies) may make the benefit available. Given the clinical and cost-effective value of home-delivered MTMs, the Innovation Center potentially could encourage those participants who have not yet made MTMs available to do so in the following models:

- Transforming Maternal Health (TMaH) Model: TMaH supports state Medicaid agencies in delivering whole-person maternity care by addressing physical, mental, and social needs during pregnancy. Participating states could incorporate home-delivered MTMs as part of care plans to improve maternal and infant health outcomes.

- Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP): Under the MSSP, Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) can provide in-kind services such as meal programs to improve patient outcomes as part of broader care coordination to effectively manage chronic disease.

- ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Model: In ACO REACH, providers can offer home-delivered MTMs as in-kind service to advance patient care.

- Transforming Episode Accountability Model (TEAM): Under TEAM, acute care hospitals have responsibility for cost and quality of care for 30 days following a Medicare FFS patient undergoing one of five types of surgical procedures. All TEAM-participating hospitals could ensure that post-discharge patients have access to home-delivered MTMs to improve health outcomes and lower total costs.

- Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program (MDPP) Expanded Model: The MDPP gives beneficiaries with prediabetes access to structured individual and group interventions with the goal of preventing the onset of type 2 diabetes. Providing home-delivered MTMs would complement the overall strategy of the model to engage the at-risk beneficiary in better managing his health to prevent type 2 diabetes onset.

- Enhancing Oncology Model (EOM): EOM providers can offer home-delivered MTMs as in-kind services to improve health outcomes and the overall care experience for beneficiaries with cancer participating in the model.

While this narrative review highlights the clinical, observational, and modeled evidence for chronic care, post-discharge, and long-term care MTMs programs, and policy opportunities surrounding MTMs, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, as a narrative review, this analysis did not employ a systematic methodology and therefore may be subject to selection bias in the studies and reports included. The evidence base itself is heterogeneous, with variations in study design, populations served, intervention protocols, and outcome measures, which limits the ability to make direct comparisons across programs. Much of the data comes from case studies, evaluations by health plans, and grey literature, which, while valuable for understanding real-world implementation, may lack the rigor and generalizability of randomized controlled trials. Additionally, many interventions combined MTMs with other supports, such as counseling from an RD, nurse case management, or supplemental food resources, making it difficult to isolate the independent contribution of MTMs to observed outcomes. Most published evaluations are also short term, and few address sustainability, scalability, or long-term health and cost outcomes. Finally, the focus on U.S.-based studies means the findings may not be generalizable to other health systems. These limitations underscore the need for additional high-quality, longitudinal, and comparative research to strengthen the evidence base and further inform federal policy decisions.

5. Conclusions

This narrative review suggests that MTMs are a cost-effective and common-sense solution to America’s chronic disease crisis. They alleviate food and nutrition insecurity, assist in managing the leading causes of disease and death in the United States, and are associated with savings in health care. They also provide social benefit to both patients and caregivers as they seek to remain healthy and active in community settings, ultimately playing a foundational role as part of a broader FIM ecosystem. Policymakers have a unique opportunity to expand access to MTMs through programs such as a Medicare FFS demonstration. Health care leaders have an opportunity to ensure MTMs are incorporated into benefit packages and care plans, and that members, patients, and providers have a clear understanding of available MTM benefits and programs, and the ability to easily access those services. The success of these initiatives will require coordinated effort from all health care stakeholders to make scaling FIM successful and realize the potential cost savings of MTMs and other FIM solutions.

Author Contributions

C.M. was responsible for conceptualization, conducting the literature search and reviewing the identified manuscripts. C.M., W.H.F. and E.G. were responsible for writing this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. The data supporting this narrative review’s results were obtained from PubMed and Google Scholar and are available in the supplied Table 1.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Catherine Macpherson has been employed at Mom’s Meals since March 2017. Author William H. Frist is a special partner at Cressey & Company, LP, where Mom’s Meals is a portfolio company. Author Emily Gillen was employed by the company Avalere Health at the time of drafting. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as potential conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| FFS | Fee-for-service |

| MTM | Medically tailored meal |

| MA | Medicare Advantage |

| FIM | Food-is-medicine |

| CMMI | Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation |

| RD | Registered dietitian |

| ED | Emergency department |

| ADL | Activities of daily living |

| MSSP | Medicare shared savings program |

| ACO | Accountable Care Organizations |

| REACH | Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health Model |

| TEAM | Transforming Episode Accountability Model |

| MDPP | Medicare Diabetes Prevention Program Expanded Model |

| EOM | Enhancing Oncology Model |

| TMaH | Transforming Maternal Health Model |

References

- Leading Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- The Economic Costs of Poor Nutrition. Available online: https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-economic-costs-of-poor-nutrition/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Equity and the Costs of Chronic Disease: Who’s Impacted the Most? Available online: https://www.ncoa.org/article/the-inequities-in-the-cost-of-chronic-disease-why-it-matters-for-older-adults/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Combatting Senior Malnutrition. Available online: https://acl.gov/news-and-events/acl-blog/combatting-senior-malnutrition (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Spotlight on Senior Health: Adverse Health Outcomes of Food Insecure Older Americans. Available online: https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/research/senior-hunger-research/or-spotlight-on-senior-health-executive-summary.pdf (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Basu, S.; Gundersen, C.; Seligman, H.K. State-level and county-level estimates of health care costs associated with food insecurity. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2019, 16, E90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- What Do Medicare Beneficiaries Value About Their Coverage? Available online: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/surveys/2024/feb/what-do-medicare-beneficiaries-value-about-their-coverage (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- Next Steps in Chronic Care: Expanding Innovative Medicare Benefits. Available online: https://bipartisanpolicy.org/download/?file=/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Next-Steps-in-Chronic-Care.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Terranova, J.; Randall, L.; Cranston, K.; Waters, D.B.; Hsu, J. Association between receipt of a medically tailored meal program and health care use. JAMA Intern. Med. 2019, 179, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mom’s Meals, AmeriHealth Caritas District of Columbia Food as Medicine Programs Reduce Health Care Costs and Readmissions. Available online: https://www.momsmeals.com/our-newsroom/moms-meals-amerihealth-caritas-district-of-columbia-food-as-medicine-programs-reduce-health-care-costs-and-readmissions/ (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Terranova, J.; Hill, C.; Ajayi, T.; Linsky, T.; Tishler, L.W.; DeWalt, D.A. Meal delivery programs reduce the use of costly health care in dually eligible Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2018, 37, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, D.L.; Frongillo, E.A., Jr.; Rauschenback, F.; Roe, D.A. Home-delivered meals benefit the diabetic elderly. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1993, 93, 587–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurvey, J.; Rand, K.; Daugherty, S.; Dinger, C.; Schmeling, J.; Laverty, N. Examining health care costs among MANNA clients and a comparison group. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2013, 4, 311–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hager, K.; Cudhea, F.P.; Wong, J.B.; Berkowitz, S.A.; Downer, S.; Lauren, B.N.; Mozaffarian, D. Association of national expansion of insurance coverage of medically tailored meals with estimated hospitalizations and health care expenditures in the US. JAMA Net. Open 2022, 5, e2236898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, S.; Hager, K.; Wang, L.; Cudhea, F.P.; Wong, J.B.; Kim, D.D.; Mozaffarian, D. Estimated impact of medically tailored meals on health care use and expenditures in 50 US states: Article examines the impact of medically tailored meals on health care use and expenditures in 50 US states. Health Aff. 2025, 44, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, E.N.; Miles, R.; Alejandro-Rodriguez, M.; Gorenflo, M.P.; Misirang, A.; Barbarotta, S.; Phillips, W.; Bharmal, N.; Yepes-Rios, M. Feasibility of self-investment in a medically tailored meals program by a large health enterprise: Cleveland Clinic experience. Nutr. Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palar, K.; Napoles, T.; Hufstedler, L.L.; Seligman, H.; Hecht, F.M.; Madsen, K.; Ryle, M.; Pitchford, S.; Frongillo, E.A.; Weiser, S.D. Comprehensive and medically appropriate food support is associated with improved HIV and diabetes health. J. Urban Health 2017, 94, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkowitz, S.A.; Delahanty, L.M.; Terranova, J.; Steiner, B.; Ruazol, M.P.; Singh, R.; Shahid, N.N.; Wexler, D.J. Medically tailored meal delivery for diabetes patients with food insecurity: A randomized cross-over trial. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, J.L.; Racine, E.F.; Ngugi, G.W.; McAuley, W.J. The effect of home-delivered Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) meals on the diets of older adults with cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustin Gleason, J.; Lundburg Bourdet, K.; Koehn, K.; Holay, S. Cardiovascular risk reduction and dietary compliance with a home-delivered diet and lifestyle modification program. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2002, 102, 1445–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callahan, C.N.; Hart, B.B.; McNeil, C.K.; Duerr, J.M.; Weller, G.B. Improved time in range during 28 days of meal delivery for people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2022, 35, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perez, L.M.; Fang, H.Y.; Ashrafi, S.A.; Burrows, B.T.; King, A.C.; Larsen, R.J.; Sutton, B.P.; Wilund, K.R. Pilot study to reduce interdialytic weight gain by provision of low-sodium, home-delivered meals in hemodialysis patients. Hemodial. Int. 2021, 25, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapper, E.; Baki, J.; Nikirk, S.; Hummel, S.; Asrani, S.K.; Lok, A. Medically tailored meals for the management of symptomatic ascites: The SALTYFOOD pilot randomized clinical trial. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2020, 8, 453–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.Q.; Duan, L.; Lee, J.S.; Winn, T.G.; Arakelian, A.; Akiyama-Ciganek, J.; Huynh, D.N.; Williams, D.D.; Han, B. Association of a medicare advantage posthospitalization home meal delivery benefit with rehospitalization and death. JAMA Health Forum 2023, 4, e231678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, S.L.; Karmally, W.; Gillespie, B.W.; Helmke, S.; Teruya, S.; Wells, J.; Trumble, E.; Jimenez, O.; Marolt, C.; Wessler, J.D.; et al. Home-delivered meals postdischarge from heart failure hospitalization. Circ. Heart Fail. 2018, 11, e004886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.L.; Connelly, N.; Parsons, C.; Blackstone, K. Simply delivered meals: A tale of collaboration. Am. J. Manag. Care 2018, 24, 301–304. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K.S.; Mor, V. Providing more home-delivered meals is one way to keep older adults with low care needs out of nursing homes. Health Aff. 2013, 32, 1796–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Implementation Considerations for Medically Tailored Meals: Summary of Expert Stakeholder Convening and Policy Recommendations. Available online: https://fimcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/FIMC-Tufts-FollowUpCMS-CMMI-Final.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Plans Generally Offered Some Supplemental Benefits, but CMS Has Limited Data on Utilization. Available online: https://www.gao.gov/assets/d23105527.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Campbell, A.D.; Godfryd, A.; Buys, D.R.; Locher, J.L. Does Participation in Home-Delivered Meals Programs Improve Outcomes for Older Adults? Results of a Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2015, 34, 124–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Medicaid Long Term Services and Supports Annual Expenditures Report. Available online: https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/downloads/ltssexpenditures2020.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Ridberg, R.; Sharib, J.R.; Garfield, K.; Hanson, E.; Mozaffarian, D. ‘Food is medicine’ in the US: A national survey of public perceptions of care, practices, and policies. Health Aff. 2025, 4, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S.2133—Medically Tailored Home-Delivered Meals Demonstration Act. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/2133/cosponsors (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Amendment in the Nature of a Substitute to H.R. 8816 Offered by Mr. Smith of Missouri. Available online: https://docs.house.gov/meetings/WM/WM00/20240627/117491/BILLS-118-HR8816-S001195-Amdt-3.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- McGovern, Malliotakis Introduce Bipartisan Bill to Address Link Between Diet and Chronic Disease. Available online: https://mcgovern.house.gov/news/documentsingle.aspx?DocumentID=400249 (accessed on 29 September 2025).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).