Relevant Criteria for Improving Quality of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Treatment: A Delphi Study

Highlights

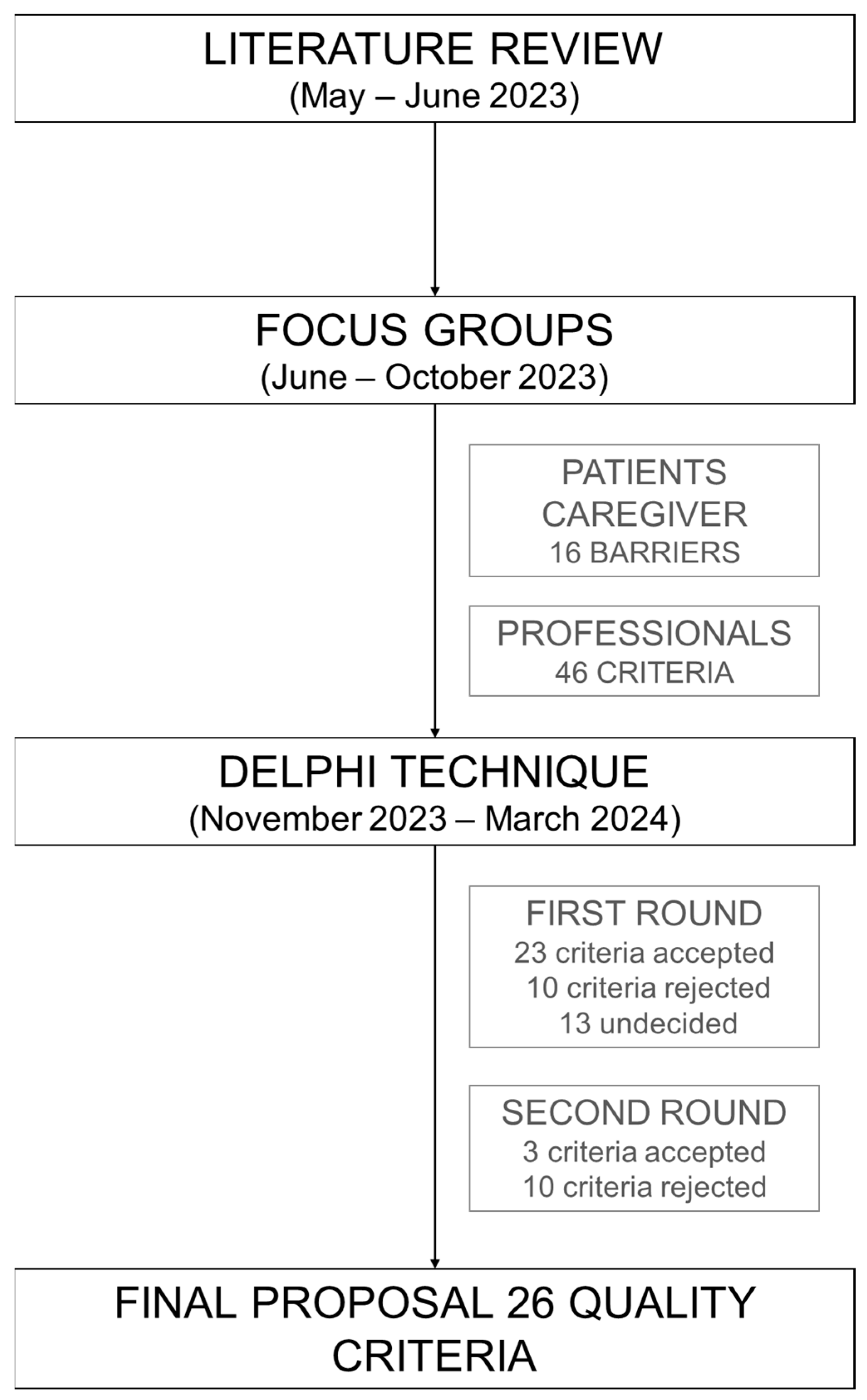

- A Delphi study identified 26 quality criteria for schizophrenia spectrum disorder (SSD) care.

- Consensus prioritized key areas: early diagnosis, care coordination, and access.

- Professionals and patients highlighted critical barriers in SSD healthcare.

- Results provide a foundation for a quality certification system in SSD care.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Patients and Informal Caregivers Focus Group

2.3. Professionals Focus Group

2.4. Delphi

3. Results

3.1. Literature Review

3.2. Focus Group

3.3. Delphi

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SSD | Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders |

| PROM | Patient-Reported Outcome Measures |

| PREM | Patient-Reported Experience Measures |

| FI | Family Intervention Therapy |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Description of Barrier | Verbatim |

|---|---|

| “They don’t take you seriously. They say there’s no need to see a psychiatrist, and by the time you realize, you’re already in the emergency room with a severe psychotic episode.” “I went through several misdiagnoses before they got it right. There’s no clear process.” |

| “You need more time and more consultations to figure out exactly what you have and which medication works for you.” |

| “The time between one appointment and the next is too long.” |

| “The consultations are always the same, repetitive questions, following a protocol without adapting to how you feel at the moment. Sometimes, they don’t even have time to listen to you.” “They say things like ‘Schizophrenia? Is it under control?’ as if everything that happens to me is because of the illness.” |

| “At first, you don’t understand anything. Nobody explains what schizophrenia is or what to expect in the future.” “I needed them to give me hope, some certainty that I could achieve things.” |

| “You see that your family needs support because they carry a heavy burden of the illness. Taking care of them too.” |

| “The psychosocial problems behind the disorder remain unresolved.” “Psychiatrists should provide us with information about patient associations and available resources.” |

| “When you go to the emergency room, they don’t have access to your medical history. They don’t know what medication you take or if you have any allergies. You have to explain it yourself in the middle of a crisis.” |

| “Sometimes, you feel like they just leave you alone.” “There isn’t enough support to help us reintegrate into normal life. They treat the illness, and then you’re on your own.” |

| “The transition was really difficult. Just when you finally know and trust your doctor, you have to start over with someone new.” |

| “The worst part was not knowing that I would have those side effects with this medication. You lack information to be prepared.” “It took me years to find the right medication. Until then, the side effects were unbearable.” |

| “For example, medication affects libido and weight, but they don’t offer a specialist”. “There is a lack of psychological services. We need more access to therapy, but it’s not available.” |

| “During hospitalization, the only thing you understand is that you have to behave well to be discharged.” “There is little information during the process, and you leave more scared and confused than when you entered.” “My friends couldn’t visit me while I was hospitalized, and I don’t have family.” |

| “In the emergency room, you see other patients who are much worse than you, and you think: is that what awaits me?” |

| “Sometimes they treat you like you’re dangerous, even when you’re not”. “They (the ambulance staff) doesn’t really understand the illness” |

| “People talk a lot about anxiety and depression, but no one talks about schizophrenia. It’s like we don’t exist.” |

Appendix A.2

Barrier 1: Delay in Diagnosis. Insufficient knowledge of the disease among healthcare professionals treating patients with schizophrenia (SSD).

|

Barrier 2: Insufficient specialized consultations for an adequate diagnosis.

|

Barrier 3: Delays in follow-up visits or lack of them.

|

Barrier 4: Repetitive, protocolized consultations with little patient-centered focus.

|

Barrier 5: Room for improvement in healthcare professionals’ communication skills. Improve patient education about their illness, treatment, and care process.

|

Barrier 6: Improve training for families and caregivers to better support patients. Strengthen family support.

|

Barrier 7: Insufficient generalized support and deficiencies in addressing associated psychosocial problems.

|

Barrier 8: Improve Comprehensive Care and address the lack of coordination and communication between services and levels of care.

|

Barrier 9: Gaps in the transition between the healthcare system and daily life during the stabilization phase.

|

Barrier 10: Risks in the transition from child-adolescent to adult mental health services.

|

Barrier 11: Delays in finding the appropriate pharmacological treatment.

|

Barrier 12: Improve accessibility to healthcare resources (psychiatry, psychology, nutrition, sexology).

|

Barrier 13: Improve inpatient care for SSD patients (enhance the humanization of hospitalizations).

|

Barrier 14: Improve emergency care for SSD patients.

|

Barrier 15: Improve ambulance services for transporting SSD patients.

|

Barrier 16: Need to promote awareness and give a voice to individuals with SSD. Combat social stigma.

|

Cross-cutting Criteria for Outcome Evaluation:

|

Appendix A.3

| Criteria Selected After the First Round | Mean | CV (%) 1 | N ≥ 9 (%) 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Criterion 8.3. Implement an electronic health record system accessible to all services and levels of care involved in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia (SSD). | 9.91 | 2.73 | 96.88 |

| Criterion 14.3. Provide a dedicated emergency cubicle for psychiatric patients that ensures patient privacy and high-quality care for individuals with SSD. | 9.47 | 7.28 | 93.75 |

| Criterion 15.2. Establish a specific protocol for hospital transportation of patients with SSD in the acute phase, including urgent and involuntary transfers. | 9.56 | 7.71 | 93.75 |

| Criterion 10.2. Implement intensive case management and community support services for patients with early-onset SSD. | 9.38 | 8.53 | 90.63 |

| Criterion 1.4. Provide a consultation channel for the mental health specialist responsible for patients with SSD. | 9.38 | 7.66 | 87.50 |

| Criterion 2.3. Offer priority appointments for psychiatry in cases of suspected SSD. | 9.31 | 12.36 | 87.50 |

| Criterion 3.2. Ensure early follow-up in psychiatric consultation after the first episode of schizophrenia (≤15 days). | 9.28 | 15.38 | 87.50 |

| Criterion 8.1. Patients with severe mental disorders (SSD) should be treated in a multidisciplinary unit. | 9.44 | 8.03 | 87.50 |

| Criterion 11.2. Achieve disease stability while avoiding hospital admissions. | 9.5 | 9.12 | 87.50 |

| Criterion 3.3. Provide access to consultation outside routine follow-up controls for situations of risk of relapse. | 9.19 | 12.38 | 84.38 |

| Criterion 10.1. Establish a care protocol to ensure a coordinated and effective transition from pediatric to adult care. | 9.34 | 9.17 | 84.38 |

| Criterion 12.3. Establish a Social and Healthcare Network for Severe Mental Illness. Clarification: This network brings together available resources and allows for the evaluation of specific cases. | 8.88 | 17.88 | 84.38 |

| Criterion 1. Assess the quality of life of SSD patients (Patient-Reported Outcome Measures, PROM). | 9.34 | 9.17 | 84.38 |

| Criterion 2.2. Provide multidisciplinary teams for disease detection and treatment. | 9.19 | 12.38 | 81.25 |

| Criterion 6.2. Inform SSD patients and their families about available social and healthcare support resources. | 9.28 | 9.94 | 81.25 |

| Criterion 6.3. Conduct educational activities and workshops for SSD patients and their families in collaboration with associations. | 9.22 | 9.53 | 81.25 |

| Criterion 1.3. Develop a protocol in Primary Care that includes criteria for early detection (prodromal symptoms) and referral criteria to Psychiatry. | 9.16 | 13.09 | 78.13 |

| Criterion 2.1. Establish a communication channel between Primary Care and Psychiatry for consultation on uncertain cases. | 9.06 | 10.20 | 78.13 |

| Criterion 9.1. Provide SSD patients who require it with training in social skills and daily life activities. | 9.31 | 8.98 | 78.13 |

| Criterion 15.1. Conduct training and awareness activities for professionals involved in transporting SSD patients to enhance compassionate care. | 9.09 | 16.6 | 78.13 |

| Criterion 6.1. Implement psychoeducational family intervention therapy (FI) to prevent relapses and improve disease prognosis. | 9.16 | 9.06 | 75.00 |

| Criterion 7.1. SSD patients should receive psychosocial care from the multidisciplinary team. | 9.25 | 11.14 | 75.00 |

| Criterion 14.1. Develop a clinical protocol for the management of SSD patients in emergency settings. | 9.13 | 13.5 | 75.00 |

| Criteria Selected After the Second Round | Mean | CV (%) 1 | N ≥ 9 (%) 2 |

| Criterion 13.1. Establish a protocol to determine when and how restraint should be applied to patients with schizophrenia (SSD). | 9.06 | 20.02 | 84.38 |

| Criterion 13.2. Assess physical harm (fractures, falls) in patients with SSD. | 8.84 | 13.32 | 75.00 |

| Cross-cutting Criterion 2. Implement a system for measuring patient experience (Patient-Reported Experience Measures, PREM) in mental health services for individuals with SSD. | 9.09 | 10.45 | 75.00 |

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, M.J.; Sawa, A.; Mortensen, P.B. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2016, 388, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishi, T.; Ikuta, T.; Matsui, Y.; Mishima, K.; Iwata, N. Effect of discontinuation v. maintenance of antipsychotic medication on relapse rates in patients with remitted/stable first-episode psychosis: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 772–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauhar, S.; Johnstone, M.; McKenna, P.J. Schizophrenia. Lancet 2022, 399, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Zhong, Y.; Yang, K.; Zhang, X.-Y. Effects of comorbid alexithymia in chronic schizophrenia: A large-sample study on the Han Chinese population. Front. Psychiatry 2025, 16, 1517540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The Global Burden of Disease: 2004 Update; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://iris.who.int/items/99c37bf2-a023-4afa-ae67-27dd6fdcc93f (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Buckley, P.F.; Miller, B.J.; Lehrer, D.S.; Castle, D.J. Psychiatric Comorbidities and Schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 2009, 35, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oud, M.J.T.; Meyboom-de Jong, B. Somatic Diseases in Patients with Schizophrenia in General Practice: Their Prevalence and Health Care. BMC Fam. Pract. 2009, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, E.R.; McGee, R.E.; Druss, B.G. Mortality in Mental Disorders and Global Disease Burden Implications: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015, 72, 334–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millan, M.J.; Andrieux, A.; Bartzokis, G.; Cadenhead, K.; Dazzan, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Gallinat, J.; Giedd, J.; Grayson, D.R.; Heinrichs, M.; et al. Altering the Course of Schizophrenia: Progress and Perspectives. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 485–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagiu, C.; Dionisie, V.; Manea, M.C.; Mazilu, D.C.; Manea, M. Internalised Stigma, Self-Steem and Perceived Social Support as Psychosocial Predictors of Quality of Life in Adult Patients with Schizophrenia. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, S.; Massarou, C.; Pfister, T.; Bleich, S.; Proskynitopoulos, P.J.; Heck, J.; Westhoff, M.S.; Glahn, A. Drug interactions in patients with alcohol use disorder: Results from a real-world study on an addiction-specific ward. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2025, 16, 20420986241311214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.H.; Lee, T.L.; Hsuan, C.F.; Wu, C.-C.; Wang, C.-P.; Lu, Y.-C.; Wei, C.-T.; Chung, F.-M.; Lee, Y.-J.; Tsai, I.-T.; et al. Inter-relationships of risk factors and pathways associated with all-cause mortality in patients with chronic schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 14, 1309822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taipale, H.; Tanskanen, A.; Mehtälä, J.; Vattulainen, P.; Correll, C.U.; Tiihonen, J. 20-year follow-up study of physical morbidity and mortality in relationship to antipsychotic treatment in a nationwide cohort of 62,250 patients with schizophrenia (FIN20). World Psychiatry 2020, 19, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, N.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Jin, M.; Liu, Y.; Cui, X.; Hu, G.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Yu, Q. Long-term effects of antipsychotics on mortality in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Braz. J. Psychiatry 2022, 44, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.C.; Seitz, D.P.; Crockford, D.; Addington, D.; Baek, H.; Lorenzetti, D.L.; Barry, R.; Bolton, J.M.; Taylor, V.H.; Kurdyak, P.; et al. Quality indicators for schizophrenia care: A scoping review. Schizophr. Res. 2024, 274, 406–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kronenberg, C.; Doran, T.; Goddard, M.; Kendrick, T.; Gilbody, S.; Dare, C.R.; Aylott, L.; Jacobs, R. Identifying primary care quality indicators for people with serious mental illness: A systematic review. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2017, 67, e519–e530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, J.J.; Pérez-Jover, V.; Lorenzo, S.; Aranaz, J.; Vitaller, J. La investigación cualitativa: Una alternativa también válida. Aten. Primaria 2004, 34, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, B.J.; Amick, H.R.; Lund, J.L.; Lee, S.Y.D.; Hoff, T.J. Use of Qualitative Methods in Published Health Services and Management Research: A 10-Year Review. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2011, 68, 3–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry 2015, 49, 887–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yañez Gallardo, R.; Cuadra Olmos, R. La técnica Delphi y la investigación en los servicios de salud. Cienc. Enferm. 2008, 14, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Vita, A.; Barlati, S.; Porcellana, M.; Sala, E.; Lisoni, J.; Brogonzoli, L.; Percudani, M.E.; Iardino, R. The patient journey project in Italian mental health services: Results from a co-designed survey on clinical interventions and current barriers to improve the care of people living with schizophrenia. Front. Psychiatry 2024, 15, 1382326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matin Bk Williamson, H.J.; Karyani, A.K.; Rezaei, S.; Soof, M.; Soltani, S. Barriers in access to healthcare for women with disabilities: A systematic review in qualitative studies. BMC Womens Health 2021, 21, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, S.; Islam, F.m.A.; Kingsley, J.; McDonald, R. Heathcare access for autistic adults: A systematic review. Medicine 2020, 99, e20899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radez, J.; Reardon, T.; Creswell, C.; Lawrence, P.J.; EvdokaBurton, G.; Waite, P. Why do children and adolescents (not) seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2021, 30, 183–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arango, C.; Bernardo, M.; Bonet, P.; Cabrera, A.; Crespo-Facorro, B.; Cuesta, M.J.; González, N.; Parrabera, S.; Sanjuan, J.; Serrano, A.; et al. When the healthcare does not follow the evidence: The case of the lack of early intervention programs for psychosis in Spain. Rev. Psiquiatr. Salud Ment. 2017, 10, 78–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda-Muñoz, J.; Quemada-González, C.; Hurtado-Lara, M.M.; García, Á.M.G.; Martí-García, C.; Pérez-Bryan, J.M.G.-H.; Morales-Asencio, J.M. Management of psychosis and schizophrenia by primary care GPs: A cross-sectional study in Spain. J. Prim. Care Community Health 2025, 16, 21501319241306177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlati, S.; Nibbio, G.; Vita, A. Evidence-based psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia: A critical review. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2024, 37, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente, J.; Algaba Arrea, F.; Buisan Rueda, O.; Gauna, D.C.; Durán, I.; Ávila, J.J.F.; Gómez-Iturriaga, A.; Blázquez, M.J.P.; Fentes, D.P.; Pardo, G.S.; et al. Criteria and indicators to evaluate quality of care in genitourinary tumour boards. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2024, 26, 1639–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, C.; Martin-Delgado, J.; Vinuesa, M.; Ibor, P.J.; Guilabert, M.; Gomez, J.; Beato, C.; Sánchez-Jiménez, J.; Velázquez, I.; Calvo-Espinos, C.; et al. Pain standards for Accredited Healthcare Organizations (ACDON Project): A mixed methods study. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 102102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estrategia de Salud Mental del Sistema Nacional de Salud 2022-2026. Ministerio de Sanidad. Secretaria General Técnica. 2022. Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/bibliotecaPub/repositorio/libros/29236_estrategia_de_salud_mental_del_Sistema_Nacional_de_Salud_2022-2026.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Vieta, E.; Menchón Magriña, J.M.; Bernardo Arroyo, M.; Pérez Sola, V.; Moreno Ruiz, C.; Arango López, C.; Bobes García, J.; Martín Carrasco, M.; Palao Vidal, D.; González-Pinto Arrillaga, A. Basic quality indicators for clinical care of patients with major depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Span. J. Psychiatry Ment. Health 2024, 17, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuhec, M. Antipsychotic treatment in elderly patients on polypharmacy with schizophrenia. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2022, 35, 332–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuhec, M.; Batinic, B. Clinical pharmacist interventions in the transition of care in a mental health hospital: Case reports focused on the medication reconciliation process. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1263464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Women | 23 | 71.88 |

| Men | 9 | 28.13 |

| Age | ||

| Mean age | 49.41 | |

| Standard deviation | 10.17 | |

| Professional Profile | ||

| Professionals: | ||

| Psychiatrist | 11 | 34.38 |

| Physician (non-psychiatrist) | 7 | 21.88 |

| Specialist Pharmacist in Hospital Pharmacy | 4 | 12.50 |

| Mental Health Specialist Nurse | 4 | 12.50 |

| Director | 2 | 6.25 |

| Patients: | ||

| Janitor | 1 | 3.13 |

| IT specialist | 1 | 3.13 |

| Administrative Staff | 1 | 3.13 |

| Retired | 1 | 3.13 |

| Place of origin | ||

| Community of Madrid | 8 | 25.00 |

| Catalonia | 4 | 12.50 |

| Andalusia | 3 | 9.38 |

| Aragon | 3 | 9.38 |

| Basque Country | 3 | 9.38 |

| Valencian Community | 3 | 9.38 |

| Principality of Asturias | 2 | 6.25 |

| Canary Islands | 2 | 6.25 |

| Galicia | 2 | 6.25 |

| Castile and Leon | 1 | 3.13 |

| Chartered Community of Navarre | 1 | 3.13 |

| Round | Consensus Level | Rating ≥ 9 |

|---|---|---|

| 1st round | Acceptance | Agreement rate ≥ 75% |

| Rejection | Agreement rate ≤ 60% | |

| Moves to the 2nd round | Agreement between 60% and 75% | |

| 2nd round | Acceptance | Agreement rate ≥ 75% |

| Rejection | Does not meet acceptance criteria |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roncero, C.; Sánchez-García, A.; Conesa Burguet, L.; Fernández Moreno, A.; Barbero, M.L.M.; Aguilera-Serrano, C.; Olmo Dorado, V.; Guajardo Remacha, J.; Rico Prieto, J.; Pérez-Esteve, C.; et al. Relevant Criteria for Improving Quality of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Treatment: A Delphi Study. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222847

Roncero C, Sánchez-García A, Conesa Burguet L, Fernández Moreno A, Barbero MLM, Aguilera-Serrano C, Olmo Dorado V, Guajardo Remacha J, Rico Prieto J, Pérez-Esteve C, et al. Relevant Criteria for Improving Quality of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Treatment: A Delphi Study. Healthcare. 2025; 13(22):2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222847

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoncero, Carlos, Alicia Sánchez-García, Llanos Conesa Burguet, Aurora Fernández Moreno, María Luisa Martin Barbero, Carlos Aguilera-Serrano, Verónica Olmo Dorado, Jon Guajardo Remacha, Joseba Rico Prieto, Clara Pérez-Esteve, and et al. 2025. "Relevant Criteria for Improving Quality of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Treatment: A Delphi Study" Healthcare 13, no. 22: 2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222847

APA StyleRoncero, C., Sánchez-García, A., Conesa Burguet, L., Fernández Moreno, A., Barbero, M. L. M., Aguilera-Serrano, C., Olmo Dorado, V., Guajardo Remacha, J., Rico Prieto, J., Pérez-Esteve, C., Vila, M. S., & Solves, J. J. M. (2025). Relevant Criteria for Improving Quality of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders Treatment: A Delphi Study. Healthcare, 13(22), 2847. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13222847