Prevalence and Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases Among Middle-Aged Migrants in Japan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

2.2. Ethical Considerations

2.3. Data Collection

- Socio-demographic data (education level, living conditions)

- Health-related data (having had a health screening, last time having a health screening, having been diagnosed with a chronic disease, on medication for any chronic disease, family history of chronic diseases)

- NCD risk factors

- tobacco use (Cigarettes, e-cigarettes, chewable tobacco)

- alcohol consumption

- dietary habits:

- consumption and frequency of fruit and vegetables

- consumption of UPF

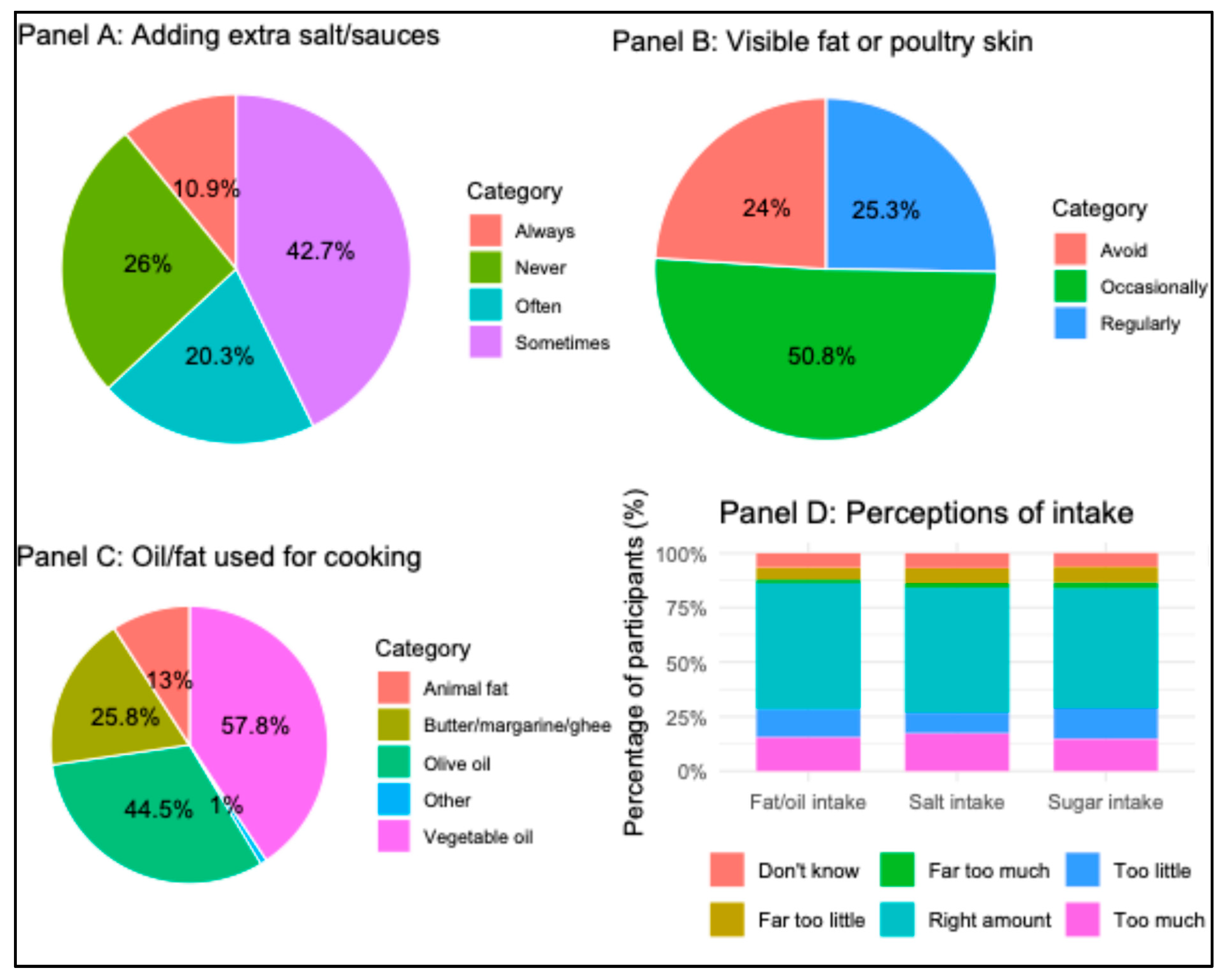

- consumption of excess salt, sugar, and fat

- type of oil used in cooking

- engaging in PA

- moderate (activities that cause moderate increases in breathing or heart rate, such as brisk walking, lifting light loads, general cleaning, cycling, etc.) PA

- vigorous (activities that cause large increases in breathing or heart rate, such as sports, fitness, carrying or lifting heavy loads, climbing stairs, digging, construction work, etc.) PA

- stress:

- frequency of stress

- sources of stress

- methods to relieve stress

- perceived stress level

- sleep

- duration of sleep at night

- sleep disturbance

- self-reported anthropometric data

- weight

- height

- waist circumference (WC)

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Survey Respondents

3.2. Prevalence of NCD Risk Factors

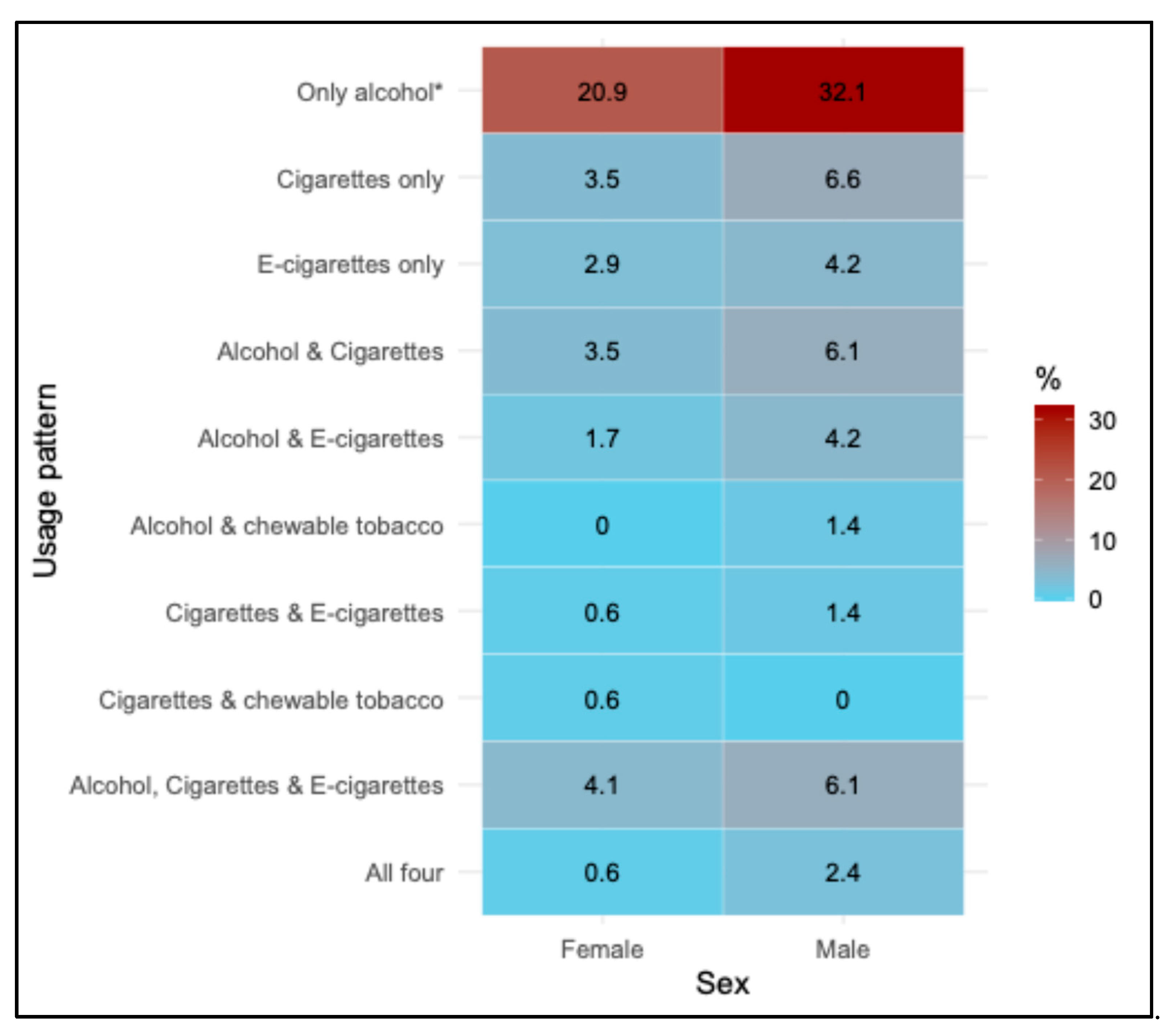

3.2.1. Tobacco and Alcohol Use

3.2.2. Fruit and Vegetable Consumption

3.2.3. Consumption of Ultra-Processed Food

3.2.4. Physical Activity

3.2.5. Sleep and Stress

3.2.6. High BMI and Abdominal Obesity

3.3. Co-Occurrence of NCD Risk Factors

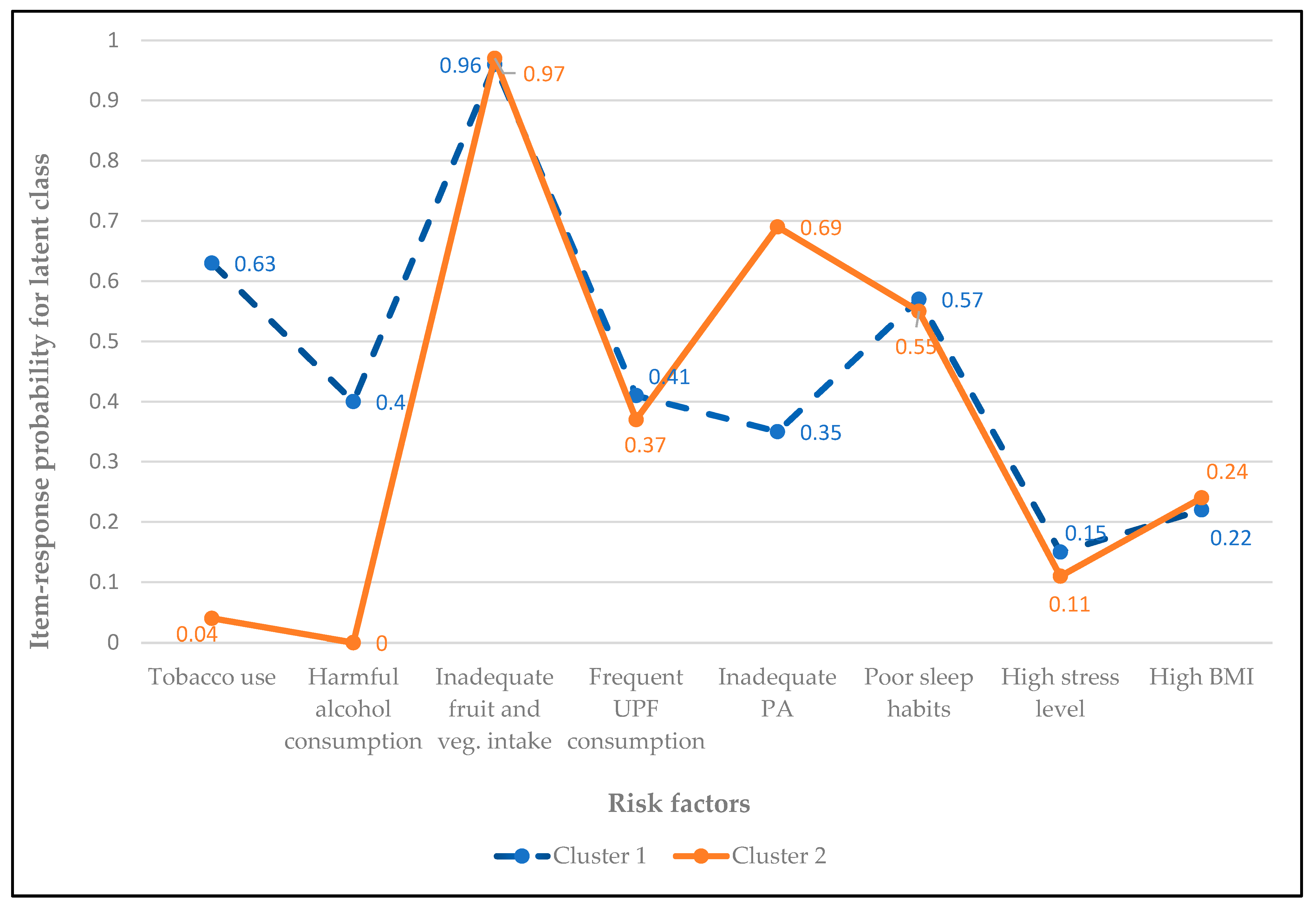

3.4. Clustering of NCD Risk Factors

4. Discussion

4.1. Prevalence of Risk Factors

4.2. Co-Occurrence and Clustering of Risk Factors

4.3. Implications for Practice and Research

4.4. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMI | Body mass index |

| NCDs | Non-communicable diseases |

| LCA | Latent class analysis |

| PA | Physical activity |

| UPF | Ultra-processed foods |

| WC | Waist circumference |

References

- WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Li, J.; Pandian, V.; Davidson, P.M.; Song, Y.; Chen, N.; Fong, D.Y.T. Burden and attributable risk factors of non-communicable diseases and subtypes in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2021: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2021. Int. J. Surg. 2025, 111, 2385–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crielaard, L.; Nicolaou, M.; Sawyer, A.; Quax, R.; Stronks, K. Understanding the impact of exposure to adverse socioeconomic conditions on chronic stress from a complexity science perspective. BMC Med. 2021, 19, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, N.S.; Annis, J.; Master, H.; Han, L.; Gleichauf, K.; Ching, J.H.; Nasser, M.; Coleman, P.; Desine, S.; Ruderfer, D.M.; et al. Sleep patterns and risk of chronic disease as measured by long-term monitoring with commercial wearable devices in the All of Us Research Program. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 2648–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meader, N.; King, K.; Moe-Byrne, T.; Wright, K.; Graham, H.; Petticrew, M.; Power, C.; White, M.; Sowden, A.J. A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health 2016, 16, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regan, C.; Fehily, C.; Campbell, E.; Bowman, J.; Faulkner, J.; Oldmeadow, C.; Bartlem, K. Clustering of chronic disease risks among people accessing community mental health services. Prev. Med. Rep. 2022, 28, 101870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. World Report on the Health of Refugees and Migrants. 2022. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/sites/g/files/tmzbdl251/files/2023-09/World-report-on-the-health-of-refugees-and-migrants.pdf (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Nisar, M.; Uddin, R.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Khan, A. The prevalence of chronic diseases in international immigrants: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand. J. Public Health 2022, 51, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, D.; Agyemang, C.; Beune, E.; Meeks, K.; Smeeth, L.; Schulze, M.; Addo, J.; de-Graft Aikins, A.; Galbete, C.; Bahendeka, S.; et al. Migration and Cardiovascular Disease Risk Among Ghanaian Populations in Europe: The RODAM Study (Research on Obesity and Diabetes Among African Migrants). Circulation Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 2017, 10, e004013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, C.; van der Linden, E.L.; Chilunga, F.; van den Born, B.H. International Migration and Cardiovascular Health: Unraveling the Disease Burden Among Migrants to North America and Europe. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2024, 13, e030228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyemang, C.; van den Born, B.J. Non-communicable diseases in migrants: An expert review. J. Travel Med. 2019, 26, tay107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehwish, N.; Tracy, K.-A.; Asaduzzaman, K. Chronic diseases and their behavioural risk factors among South Asian immigrants in Australia. Aust. Health Rev. 2025, 49, AH24032. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, M.; Bose, M.; Gawron, K.M.; Blumberg, R. Metabolic Syndrome and Chronic Disease Risk in South Asian Immigrants: A Review of Prevalence, Factors, and Interventions. Healthcare 2023, 11, 720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saquib, J.; Umar, A.; Sula, I.; Almazrou, A.; Halim, Y.H.A.; Jihwaprani, M.C.; Mousa, A.A.; Ali, A.E.; Darwish, M.H.; Alhaimi, M.N.; et al. Chronic disease burden and its associated risk factors among migrant workers in Saudi Arabia. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2025, 31, 101889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.M.; Loney, T.; Dhaheri, S.A.; Vatanparast, H.; Elbarazi, I.; Agarwal, M.; Blair, I.; Ali, R. Association between acculturation, obesity and cardiovascular risk factors among male South Asian migrants in the United Arab Emirates—A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Yun, J.M.; Han, J.S.; Park, S.M.; Park, Y.S.; Hong, S.K. The Prevalence of Chronic Diseases among Migrants in Korea According to Their Length of Stay and Residential Status. Korean J. Fam. Med. 2012, 33, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piao, H.; Yun, J.M.; Shin, A.; Cho, B.; Kang, D. Comparing Non-Communicable Disease Risk Factors in Asian Migrants and Native Koreans among the Asian Population. Biomol. Ther. 2022, 30, 603–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattar, S.A.M.; Kan, J.Y.L.; Goh, O.Q.M.; Tan, Y.; Kumaran, S.S.; Shum, K.L.; Lee, G.; Balakrishnan, T.; Zhu, L.; Chong, C.J.; et al. COVID-19 pandemic unmasking cardiovascular risk factors and non-communicable diseases among migrant workers: A cross-sectional study in Singapore. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e055903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistics On Foreign Residents. Immigration Services Agency. Available online: https://www.moj.go.jp/isa/policies/statistics/index.html (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- International Migrant Stock 2024: Destination and Origin. United Nations (UN). Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Stafford, M.; Newbold, B.K.; Ross, N.A. Psychological distress among immigrants and visible minorities in Canada: A contextual analysis. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2011, 57, 428–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobori, E.; Maeda, Y.; Kamata, K.; Nozue, M.; Fukuda, H.; Miura, H. Health transition of Thai migrant women in Japan: A preliminary cross-sectional study in a country with insufficient migrant health data. Arch. Public Health 2025, 83, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagamatsu, Y.; Barroga, E.; Sakyo, Y.; Igarashi, Y.; Yuko, O. Risks and perception of non-communicable diseases and health promotion behavior of middle-aged female immigrants in Japan: A qualitative exploratory study. BMC Women's Health 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, H.; Nishino, Y.; Aizawa, N.; Takahashi, K.; Itagaki, A. Health problems and lifestyles of uninsured immigrants: A report from a free health check-up at a hospital in Japan. BMC Res. Notes 2025, 18, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, M.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Burton, N.W.; Khan, A. A Longitudinal Assessment of Risk Factors and Chronic Diseases among Immigrant and Non-Immigrant Adults in Australia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, T.N.N.; Shirayama, Y.; Moolphate, S.; Lorga, T.; Jamnongprasatporn, W.; Yuasa, M.; Aung, M.N. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Hypertension among Myanmar Migrant Workers in Thailand. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhter, N.; Begum, K.; Nahar, P.; Cooper, G.; Vallis, D.; Kasim, A.; Bentley, G.R. Risk factors for non-communicable diseases related to obesity among first- and second-generation Bangladeshi migrants living in north-east or south-east England. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 1588–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, S.U.; Kumar, B.N.; Nugegoda, D.B.; Meyer, H.E. Comparison of cardiovascular risk factors between Sri Lankans living in Kandy and Oslo. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarich, P.E.A.; Ding, D.; Sitas, F.; Weber, M.F. Co-occurrence of chronic disease lifestyle risk factors in middle-aged and older immigrants: A cross-sectional analysis of 264,102 Australians. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, M. Clustering of health behaviors among Japanese adults and their association with socio-demographics and happiness. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0266009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurven, M.; Blackwell, A.D.; Rodríguez, D.E.; Stieglitz, J.; Kaplan, H. Does blood pressure inevitably rise with age? Longitudinal evidence among forager-horticulturalists. Hypertension 2012, 60, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, C.W.; Egan, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Age-related changes in glucose metabolism, hyperglycemia, and cardiovascular risk. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 886–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019, 9th ed. Available online: https://diabetesatlas.org/ (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Lachman, M.E. Development in midlife. Annual Review of Psychology. 2004, 55, 305–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijeratne, D.; Pathmeswaran, A. Factors associated with behavioural risk factors of non-communicable diseases among returnee Sri Lankan migrant workers from the Middle East. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanga, S.K.; Lemeshow, S. Sample Size Determination in Health Studies: A Practical Manual; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007, 4, e296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. STEPS Instrument. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/noncommunicable-diseases/surveillance/systems-tools/steps/instrument (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Batista, P.; Neves-Amado, J.; Pereira, A.; Amado, J. FANTASTIC lifestyle questionnaire from 1983 until 2022: A review. Health Promot. Perspect. 2023, 13, 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waist circumference and waist–hip ratio: Report of a WHO expert consultation. In Proceedings of the 12th WHOPE Working Group Meeting, Geneva, Switzerland, 8–11 December 2008; Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/44583/9789241501491_eng.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- WHO. Tobacco. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Pleasants, R.A.; Rivera, M.P.; Tilley, S.L.; Bhatt, S.P. Both Duration and Pack-Years of Tobacco Smoking Should Be Used for Clinical Practice and Research. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, 17, 804–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core Resource on Alcohol. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Available online: https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/ (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Smith, L.; Guillermo, F.L.S.; Veronese, N.; Soysal, P.; Oh, H.; Barnett, Y.; Keyes, H.; Butler, L.; Allen, P.; Kostev, K.; et al. Fruit and Vegetable Intake and Non-Communicable Diseases among Adults Aged ≥50 Years in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2022, 26, 1003–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health and Department of Census and Statistics. Non Communicable Diseases Risk Factor Survey (STEPS Survey); Sumathi Printers: Colombo, Sri Lanka, 2021; ISBN 978-624-5719-78-5. [Google Scholar]

- Srour, B.; Fezeu, L.K.; Kesse-Guyot, E.; Allès, B.; Mèjean, C.; Andrianasolo, R.M.; Chazelas, E.; Deschasaux, M.; Hercberg, S.; Glan, P.; et al. Ultra-processed food intake and risk of cardiovascular disease: Prospective cohort study (NutriNet-Santè). BMJ 2019, 365, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consensus Conference Panel, Recommended amount of sleep for a Healthy Adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2015, 38, 843–844. [CrossRef]

- Lesage, F.X.; Berjot, S.; Deschamps, F. Clinical stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occup. Med. 2012, 62, 600–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Ng, M.; Fleming, T.; Robinson, M.; Thomson, B.; Graetz, N.; Margono, C.; Mullany, E.C.; Biryukov, S.; Abbafati, C.; Ferede Abera, S.; et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of adult overweight and obesity, 1990–2021, with forecasts to 2050: A forecasting study for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2025, 405, 813–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, C.D.; English, D.R.; Milne, E.; Winter, M.G. Meta-analysis of alcohol and all-cause mortality: A validation of NHMRC recommendations. Med. J. Aust. 1996, 164, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gmel, G.; Gutjahr, E.; Rehm, J. How stable is the risk curve between alcohol and all-cause mortality and what factors influence the shape? A precision-weighted hierarchical meta-analysis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2003, 18, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griswold, M.G.; Fullman, N.; Hawley, C.; Arian, N.; Zimsen, S.R.M.; Tymeson, H.D.; Venkateswaran, V.; Tapp, A.D.; Forouzanfar, M.H.; Salama, J.S.; et al. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018, 392, 1015–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhong, F.; Huang, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Zhang, S. Global burden of disease related to tobacco products and trends projected: 1990–2021. Addict. Behav. 2025, 169, 108391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simet, S.M.; Sisson, J.H. Alcohol’s effects on lung health and immunity. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2015, 37, 199–208. [Google Scholar]

- Mawditt, C.; Sasayama, K.; Katanoda, K.; Gilmour, S. The Clustering of Health-Related Behaviors in the Adult Japanese Population. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 31, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popkin, B.M.; Ng, S.W. The nutrition transition to a stage of high obesity and noncommunicable disease prevalence dominated by ultra-processed foods is not inevitable. Obes. Rev. 2022, 23, e13366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delavari, M.; Sonderlund, A.L.; Swinburn, B.; Mellor, D.; Renzaho, A. Acculturation and obesity among migrant populations in high income countries—A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeywickrama, H.M.; Uchiyama, M.; Sakagami, M.; Saitoh, A.; Yokono, T.; Koyama, Y. Post-Migration Changes in Dietary Patterns and Physical Activity among Adult Foreign Residents in Niigata Prefecture, Japan: A Mixed-Methods Study. Nutrients 2023, 15, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, E.B.; Elmose-Østerlund, K.; Ibsen, B. A survey study of physical activity participation in different organisational forms among groups of immigrants and descendants in Denmark. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippou, K.; Knappe, K.; Morres, I.D.; Tzormpatzakis, E.; Proskinitopoulos, T.; Theodorakis, Y.; Gerber, M.; Hatzigeorgiadis, A. Objectively measured physical activity and mental health among asylum seekers residing in a camp. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2025, 77, 102794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S. Obesity and overweight prevalence in immigration: A meta-analysis. Obes. Med. 2021, 22, 100321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amlashi, S.; Majzoobi, M.; Forstmeier, S. The relationship between acculturative stress and psychological outcomes in international students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1403807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuit, J.A.; van Loon, A.J.M.; Tijhuis, M.; Ocké, M.C. Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors in a General Adult Population. Prev. Med. 2002, 35, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaw, K.T.; Wareham, N.; Bingham, S.; Welch, A.; Luben, R.; Day, N. Combined impact of health behaviours and mortality in men and women: The EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. PLoS Med. 2008, 5, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, M.M.; Bhuiyan, M.R.; Karim, M.N.; Zaman, M.; Rahman, M.; Akanda, A.W.; Fernando, T. Clustering of non-communicable diseases risk factors in Bangladeshi adults: An analysis of STEPS survey 2013. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalene, K.E.; Lergenmuller, S.; Sund, E.R.; Hopstock, L.A.; Robsahm, T.E.; Nilssen, Y.; Nystad, W.; Larsen, I.K.; Ariansen, I. Clustering and trajectories of key noncommunicable disease risk factors in Norway: The NCDNOR project. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 14479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, T.; Townsend, N.; Gupta, R.D.; Ghosh, A.; Rawal, L.B.; Mørkrid, K.; Mamun, A. Clustering of metabolic and behavioural risk factors for cardiovascular diseases among the adult population in South and Southeast Asia: Findings from WHO STEPS data. Lancet Reg. Health—Southeast Asia 2023, 12, 100164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, B.; Sherman, K.A.; Jones, M.; Bayl-Smith, P. The Clustering of health behaviours in older Australians and its association with physical and psychological status, and sociodemographic indicators. Ann. Behav. Med. 2014, 48, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noble, N.; Paul, C.; Turon, H.; Oldmeadow, C. Which modifiable health risk behaviours are related? A systematic review of the Clustering of Smoking, Nutrition, Alcohol and Physical activity (‘SNAP’) health risk factors. Prev. Med. 2015, 81, 16–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettigrew, S.; Dana, L.M.; McAleese, A.; Bastable, A.; Drane, C.; Sapountsis, N. Brief report: A latent class analysis of guideline compliance across nine health behaviors. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2021, 29, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenton, S.; Burrows, T.L.; Collins, C.E.; Holliday, E.G.; Kolt, G.S.; Murawski, B.; Rayward, A.T.; Stamatakis, E.; Vandelanotte, C.; Duncan, M.J. Behavioural mediators of reduced energy intake in a physical activity, diet, and sleep behaviour weight loss intervention in adults. Appetite 2021, 165, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A.M. Gender Differences in the Epidemiology of Alcohol Use and Related Harms in the United States. Alcohol. Res. 2020, 40, 01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, G.I.; da Silva, I.C.M.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.L.; Brown, W.J. Shifting the Physical Inactivity Curve Worldwide by Closing the Gender Gap. Sports Med. 2018, 48, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthold, R.; Stevens, G.A.; Riley, L.M.; Bull, F.C. Worldwide trends in insufficient physical activity from 2001 to 2016: A pooled analysis of 358 population-based surveys with 1·9 million participants. The Lancet. Glob. Health 2018, 6, e1077–e1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdarevic, M.; Choi, A.N.; Gimeno Ruiz de Porras, D.; Barnett, T.E. Examining Associations Between Smoking Patterns and Employment Status Among a Nationally Representative Sample of U.S. Adults. AJPM Focus 2025, 4, 100376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thørrisen, M.M.; Skogen, J.C.; Bonsaksen, T.; Skarpaas, L.S.; Aas, R.W. Are workplace factors associated with employee alcohol use? The WIRUS cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e064352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Murata, C.; Ninomiya, T.; Takabayashi, T.; Noda, T.; Hayasaka, S.; Nakamura, M.; Ojima, T. Occupational factors and problem drinking among a Japanese working population. Ind. Health 2013, 51, 490–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Risk Factor | Related Measures (Response Options Used in the Survey) | Definition of ‘Risk’ |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Tobacco use (Cigarettes, e-cigarettes, chewable tobacco) | Practice: Current, past, or never Among current and past users:

| Current users: Any type and level of tobacco use [41]. Former risk exposure: ≥10 unit-years b [42] |

| 2. Harmful alcohol consumption | Practice: Current, past, or never Among current and past users:

| Current users: For women—2 or more drinks in a day For men—3 or more drinks in a day [43]. Former risk exposure: consumption of three or more drinks for more than 1 year c. |

| 3. Insufficient fruit and vegetable consumption (green vegetables, legumes, roots and tubers, and other vegetables) d | Consumption frequency: Everyday, 5–6 days, 3–4 days, 1–2 days, once/week, rarely/never Number of servings per day e: <1, 1, 2, 3, >4 | Fruit intake: no daily consumption or consumption of <2 servings/day Vegetable intake f: <3 servings/day across all vegetable categories and consuming on <5 days/week [44,45]. |

| 4. Frequent consumption of UPF g | Consumption frequency: Everyday, 5–6 days, 3–4 days, 1–2 days, 2–3 times/ month, once/ month, rarely/never | Consumption of any type of UPF almost every day or 5–6 days/week [46]. |

| 5. Inadequate PA | Number of days per week engaged in moderate PA and/or vigorous PA for at least ten minutes at a time h [frequency]; Minutes spent engaged in vigorous and/or moderate PA h [duration] | <150 min weekly moderate activity i or, <75 min weekly vigorous activity i or, less than an equivalent combination of both j [6]. |

| 6. Poor sleep habits | Number of hours sleep at night | Individuals with shorter (≤6 h) or longer (>9 h) daily sleep duration [47] |

| 7. High stress level | Frequency of stress (often, sometimes, rarely, never) Perceived stress level, ranging from 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest). | Feeling stressed ‘often’ and self-reported stress level ≥ 7 [48] |

| 8. High BMI | Current weight (kg) Current height (cm) | BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 (Overweight or obese) k [49] |

| n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30–39 years | 116 | 30.2 |

| 40–49 years | 149 | 38.7 | |

| 50–60 years | 119 | 31.0 | |

| Sex | Male | 212 | 55.2 |

| Female | 172 | 44.8 | |

| Marital status | Married | 234 | 60.9 |

| Unmarried | 150 | 39.1 | |

| Residential region | Hokkaido | 15 | 3.9 |

| Tohoku | 20 | 5.2 | |

| Kanto | 165 | 43.0 | |

| Chubu | 62 | 16.1 | |

| Kansai | 84 | 21.9 | |

| Chugoku | 21 | 5.5 | |

| Shikoku | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Kyushu and Okinawa | 29 | 7.6 | |

| Employment status | Company employee (Full-time) | 193 | 50.3 |

| Company employee (Contract) | 27 | 7.0 | |

| Part-time work | 53 | 13.8 | |

| Government employee | 19 | 4.9 | |

| Self-employee | 13 | 3.4 | |

| Housewife | 31 | 8.1 | |

| Business owner/ executive | 10 | 2.6 | |

| Doctor/ medical personnel | 4 | 1.0 | |

| Freelancer | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Unemployed | 14 | 3.6 | |

| Student | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Other | 9 | 2.3 | |

| Annual household income | <1,000,000¥ | 19 | 4.9 |

| 1,000,000–4,999,999¥ | 133 | 34.7 | |

| 5,000,000–9,999,999¥ | 158 | 41.2 | |

| 10,000,000–14,999,999¥ | 44 | 11.5 | |

| 15,000,000–19,999,999¥ | 18 | 4.7 | |

| >20,000,000¥ | 12 | 3.1 | |

| Degree of Education | No formal schooling | 6 | 1.6 |

| Primary/elementary school | 6 | 1.6 | |

| Secondary/junior high school | 14 | 3.6 | |

| High school | 101 | 26.3 | |

| College/university | 194 | 50.5 | |

| Postgraduate | 60 | 15.6 | |

| Other | 3 | 0.8 | |

| Living condition | Living alone | 100 | 26.0 |

| Living with spouse/partner | 84 | 21.9 | |

| Living with family | 198 | 51.6 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.5 | |

| Health screening history | Yes | 293 | 76.3 |

| Time since last screening | A year ago | 235 | 61.2 |

| 2 years ago | 21 | 5.5 | |

| 3 years ago | 19 | 4.9 | |

| 4 or more years ago | 18 | 4.7 | |

| Presence of medical conditions | High blood pressure | 69 | 18.0 |

| Diabetes | 27 | 7.0 | |

| High cholesterol | 67 | 17.4 | |

| Heart diseases | 22 | 5.7 | |

| Currently on medication | High blood pressure | 39 | 10.2 |

| Diabetes | 16 | 4.2 | |

| High cholesterol level | 26 | 6.8 | |

| Heart disease | 7 | 1.8 | |

| Family history | High blood pressure | 81 | 21.0 |

| Diabetes | 52 | 13.5 | |

| High cholesterol level | 51 | 13.2 | |

| Heart disease | 23 | 6.0 |

| Cigarettes | E-Cigarettes | Chewable Tobacco | Alcohol | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice (n = 384) | Current users | 70 (18.2) | 55 (14.3) | 11 (2.9) | 164 (42.7) |

| Former users | 109 (28.4) | 77 (20.1) | 44 (11.5) | 90 (23.4) | |

| Never used | 205 (53.4) | 252 (65.6) | 329 (85.7) | 130 (33.9) | |

| Heavy exposure * | Current users | 52 (74.3) | 42 (76.4) | 1 (9.1) | 59 (36.0) |

| Former users | 60 (55.0) | 16 (20.8) | 11 (25.0) | 29 (32.2) |

| Female (n = 172) | Male (n = 212) | |

|---|---|---|

| Processed salty food | 26 (15.1) | 30 (14.2) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages | 44 (25.6) | 41 (19.3) |

| Sweet snacks * | 46 (26.7) | 28 (13.2) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages or sweet snacks * | 62 (36.0) | 51 (24.1) |

| Sugar-sweetened beverages and sweet snacks * | 28 (16.3) | 18 (8.5) |

| Deep-fried foods | 20 (11.6) | 23 (10.8) |

| Processed high-fat foods | 27 (15.7) | 27 (12.7) |

| Deep-fried or high-fat processed foods | 32 (18.6) | 38 (17.9) |

| Deep-fried and high-fat processed foods | 15 (8.7) | 12 (5.7) |

| Number of UPF categories consumed | ||

| 5 | 10 (5.8) | 8 (3.8) |

| 4 | 5 (2.9) | 2 (0.9) |

| 3 | 9 (5.2) | 8 (3.8) |

| 2 | 18 (10.5) | 16 (7.5) |

| 1 | 30 (17.4) | 45 (21.2) |

| 0 | 100 (58.1) | 133 (62.7) |

| Vigorous PA | Moderate PA | Sports/Fitness | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Practice (n = 384) | 131 (34.1) | 199 (51.8) | 158 (41.1) | |

| Frequency * | Everyday | 22 (5.7) | 52 (13.5) | 23 (6.0) |

| 6 days/week | 14 (3.6) | 13 (3.4) | 10 (2.6) | |

| 5 days/week | 27 (7.0) | 47 (12.2) | 22 (5.7) | |

| 4 days/week | 16 (4.2) | 19 (4.9) | 26 (6.8) | |

| 3 days/week | 13 (3.4) | 17 (4.4) | 16 (4.2) | |

| 2 days/week | 16 (4.2) | 25 (6.5) | 20 (5.2) | |

| Once/week | 23 (6.0) | 26 (6.8) | 41 (10.7) | |

| Duration of PA * | <30 min | 38 (9.9) | 66 (17.2) | 40 (10.4) |

| 30–59 min | 46 (12.0) | 74 (19.3) | 60 (15.6) | |

| 1–2 h | 27 (7.0) | 35 (9.1) | 47 (12.2) | |

| >2 h | 20 (5.2) | 24 (6.3) | 11 (2.9) |

| Total (n = 384) | Male (n = 212) | Female (n = 172) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shorter sleep time (≤6 h) | 204 (53.1) | 112 (52.8) | 92 (53.5) |

| Longer sleep time (>9 h) | 12 (3.1) | 3 (1.4) | 9 (5.2) |

| Difficulty falling or staying asleep | |||

| Often | 66 (17.2) | 37 (17.5) | 29 (16.9) |

| Sometimes | 93 (24.2) | 45 (21.2) | 48 (27.9) |

| Rarely | 166 (43.2) | 95 (44.8) | 71 (41.3) |

| Never | 59 (15.4) | 35 (16.5) | 24 (14.0) |

| Frequency of stress | |||

| Often | 70 (18.2) | 40 (18.9) | 30 (17.4) |

| Sometimes | 187 (48.7) | 101 (47.6) | 86 (50.0) |

| Rarely | 100 (26.0) | 57 (26.9) | 43 (25.0) |

| Never | 27 (7.0) | 14 (6.6) | 13 (7.6) |

| Intensity of stress | |||

| Low (0–3) | 36 (9.4) | 16 (7.5) | 20 (11.6) |

| Moderate (4–6) | 112 (29.2) | 61 (28.8) | 51 (29.7) |

| High (7–10) | 109 (28.4) | 64 (30.2) | 45 (26.2) |

| At risk stress level * | 52 (13.6) | 32 (15.1) | 20 (11.7) |

| Sources of stress | |||

| Work | 151 (39.3) | 92 (43.4) | 59 (34.3) |

| Finances | 115 (29.9) | 68 (32.1) | 47 (27.3) |

| Language barriers | 31 (8.1) | 15 (7.1) | 16 (9.3) |

| Family | 68 (17.7) | 30 (14.2) | 38 (22.1) |

| Health | 68 (17.7) | 31 (14.6) | 37 (21.5) |

| Coping strategies # | |||

| Sleeping or resting | 154 (40.1) | 86 (40.6) | 68 (39.5) |

| Talking to someone | 85 (22.1) | 35 (16.5) | 50 (29.1) |

| Exercise | 80 (20.8) | 51 (24.1) | 29 (16.9) |

| Religious or spiritual practice | 22 (5.7) | 16 (7.5) | 6 (3.5) |

| Other | 15 (3.9) | 9 (4.2) | 6 (3.5) |

| Female | Male | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI * (Median, IQR) | 20.03 (4.26) | 23.13 (4.50) | <0.001 |

| WC # (Median, IQR) | 67.0 (15.5) | 80.0 (12.0) | <0.001 |

| General obesity, n (%) * | <0.001 | ||

| Underweight | 38 (22.1) | 11 (5.2) | |

| Normal weight | 111 (64.5) | 136 (64.2) | |

| Overweight | 16 (9.3) | 47 (22.2) | |

| Obesity | 7 (4.1) | 18 (8.5) | |

| Abdominal obesity, # n (%) | |||

| WC—Increased risk $ | 19 (11.3) | 17 (8.1) | 0.162 |

| WC—Substantially increased risk $ | 6 (3.6) | 16 (7.6) |

| No. of Risk Factors | Age Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 30–39 (n = 116) | 40–49 (n = 149) | 50–60 (n = 119) | |

| Female (n = 172) | |||

| 1 | 2 (4.3) | 5 (7.6) | 2 (3.4) |

| 2 | 16 (34.0) | 18 (27.3) | 12 (20.3) |

| 3 | 12 (25.5) | 17 (25.8) | 21 (35.6) |

| 4 | 12 (25.5) | 13 (19.7) | 19 (32.2) |

| 5 | 4 (8.5) | 9 (13.6) | 5 (8.5) |

| 6 | 1 (2.1) | 4 (6.1) | 0 |

| Male (n = 212) | |||

| 1 | 4 (5.7) | 2 (2.4) | 3 (5.1) |

| 2 | 11 (15.7) | 9 (10.8) | 7 (11.9) |

| 3 | 31 (44.3) | 29 (34.9) | 13 (22.0) |

| 4 | 15 (21.4) | 25 (30.1) | 20 (33.9) |

| 5 | 8 (11.4) | 12 (14.5) | 11 (18.6) |

| 6 | 1 (1.4) | 6 (7.2) | 3 (5.1) |

| 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 (3.4) |

| Tobacco/Alcohol-Diet Cluster (n = 180) | Sedentary Life-Diet Cluster (n = 204) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30–39 years | 54 (30.0) | 63 (30.9) | 0.980 |

| 40–49 years | 70 (38.9) | 79 (38.7) | ||

| 50–60 years | 56 (31.1) | 62 (30.4) | ||

| Sex | Male | 123 (68.3) | 89 (43.6) | <0.001 |

| Female | 57 (31.7) | 115 (56.4) | ||

| Employment status | Company employee (Full-time) | 102 (56.7) | 91 (44.6) | 0.021 |

| Company employee (Contract) | 12 (6.7) | 15 (7.4) | ||

| Part-time work | 20 (11.1) | 33 (16.2) | ||

| Government employee | 14 (7.8) | 5 (2.5) | ||

| Self-employee | 4 (2.2) | 9 (4.4) | ||

| Housewife | 7 (3.9) | 24 (11.8) | ||

| Business owner/executive | 4 (2.2) | 5 (2.5) | ||

| Doctor/medical personnel | 3 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Freelancer | 4 (2.2) | 5 (2.5) | ||

| Unemployed | 7 (3.9) | 7 (3.4) | ||

| Student | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| Other | 2 (1.1) | 7 (3.4) | ||

| Annual household income | <1,000,000¥ | 9 (5.0) | 10 (4.9) | 0.823 |

| 1,000,000–4,999,999¥ | 57 (31.7) | 76 (37.3) | ||

| 5,000,000–9,999,999¥ | 77 (37.7) | 81 (39.7) | ||

| 10,000,000–14,999,999¥ | 24 (13.3) | 20 (9.8) | ||

| 15,000,000–19,999,999¥ | 9 (5.0) | 9 (4.4) | ||

| >20,000,000¥ | 4 (2.2) | 8 (3.9) | ||

| Degree of Education | No formal schooling | 2 (1.1) | 4 (2.0) | 0.180 |

| Primary/elementary school | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.0) | ||

| Secondary/junior high school | 6 (3.3) | 8 (3.9) | ||

| High school | 57 (31.7) | 44 (21.6) | ||

| College/university | 89 (49.4) | 105 (51.5) | ||

| Postgraduate | 21 (11.7) | 39 (19.1) | ||

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 2 (1.0) | ||

| Living condition | Living alone | 50 (27.8) | 50 (24.5) | 0.398 |

| Living with spouse/partner | 39 (21.7) | 45 (22.1) | ||

| Living with family | 89 (49.4) | 109 (53.4) | ||

| Other | 2 (1.1) | 0 | ||

| Presence of medical conditions | High blood pressure | 45 (25.0) | 24 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 18 (10.0) | 9 (4.4) | 0.033 | |

| High cholesterol | 41 (22.8) | 26 (12.7) | 0.010 | |

| Heart diseases | 18 (10.0) | 4 (2.0) | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Abeywickrama, H.M.; Koyama, Y.; Uchiyama, M.; Okuda, A. Prevalence and Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases Among Middle-Aged Migrants in Japan. Healthcare 2025, 13, 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212781

Abeywickrama HM, Koyama Y, Uchiyama M, Okuda A. Prevalence and Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases Among Middle-Aged Migrants in Japan. Healthcare. 2025; 13(21):2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212781

Chicago/Turabian StyleAbeywickrama, Hansani Madushika, Yu Koyama, Mieko Uchiyama, and Akiko Okuda. 2025. "Prevalence and Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases Among Middle-Aged Migrants in Japan" Healthcare 13, no. 21: 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212781

APA StyleAbeywickrama, H. M., Koyama, Y., Uchiyama, M., & Okuda, A. (2025). Prevalence and Clustering of Lifestyle Risk Factors for Chronic Diseases Among Middle-Aged Migrants in Japan. Healthcare, 13(21), 2781. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare13212781