Abstract

Background: Interprofessional collaboration is vital for comprehensive, patient-centered care. Despite growing recognition of oral–systemic health links, the integration of dentists into healthcare teams remains limited. This scoping review mapped existing evidence on dental professionals’ roles within interprofessional healthcare, identifying key benefits, barriers, and facilitators. Methods: A systematic search of PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science identified English-language studies (2014 to 2024) focused on collaboration between dental and non-dental providers. Studies addressing oral–systemic health without team-based integration were excluded. Screening and data charting followed the PRISMA-ScR framework using JBI data extraction and critical appraisal tools. Data were synthesized thematically by collaboration model, outcomes, and influencing factors. Results: Nine studies met the inclusion criteria. Integrating dental professionals into healthcare teams improved patient outcomes, quality of life, and satisfaction. Effective models included nurse practitioner–dentist partnerships and medical–dental collaboration in pediatrics and chronic disease care. Barriers included poor communication, lack of interoperable electronic health records, role ambiguity, and limited interprofessional training. Key facilitators were supportive policies, integrated care structures, professional education, and strong team communication. Conclusions: Integrating dentists into interprofessional teams enhances healthcare delivery and patient outcomes. However, significant barriers remain. Addressing communication gaps, implementing shared health records, and expanding interprofessional education are essential steps toward more cohesive care. Future research should evaluate scalable integration frameworks and incorporate patient perspectives to inform team-based care.

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization defines interprofessional collaboration (IPC) as the process by which multiple healthcare professionals work together with patients, families, caregivers, and communities to deliver coordinated, patient-centered care [1]. Health professionals involved include mental health providers, specialty and primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, registered dietitians, social workers, psychologists, and pharmacists [2]. Dentists are essential members of this network, contributing to disease prevention, early detection, and health promotion throughout the lifespan. The FDI World Dental Federation emphasizes oral health as integral to overall health, defining it as the capacity to speak, smile, chew, and swallow effectively [3]. Poor oral health, particularly periodontal disease and chronic inflammation, has been linked to systemic conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory illness, and cognitive decline [4,5], underscoring the need to integrate dental professionals into broader healthcare systems.

Opportunities for integration have been documented across populations and chronic conditions. Primary care providers frequently interact with at-risk groups such as children, pregnant individuals, and patients with chronic diseases like diabetes [6]. Research shows that children are more likely to attend dental appointments when referred by a primary care provider [7,8], and pediatric patients tend to see their medical providers more regularly than their dentists [9]. National survey data confirm these patterns: younger children have more frequent physician visits, while older children are more likely to see a dentist, suggesting an opportunity for both professions to reinforce each other’s preventive roles [10]. The increased medical contact correlates with a lower incidence of dental decay among children [11]. Interprofessional interventions in pediatric and maternal–child health settings also demonstrate measurable benefits. For example, a randomized trial in Peru found that collaboration between nurses and dentists within mother–child health clinics significantly reduced early childhood caries [12]. Additionally, it is now common for pediatric providers to apply fluoride varnish during routine checkups, a preventive practice that strengthens teeth and reduces decay [13]. Similarly, collaborative efforts in underserved communities also demonstrate feasibility and effectiveness in improving oral health outcomes [14].

Among pregnant individuals, misconceptions about dental care safety [15] limit care use despite a higher risk for gingivitis and caries [16,17]. Obstetricians and gynecologists, as well as other maternal health professionals, can play a key role in addressing these gaps through coordinated patient education [18]. Similarly, people with diabetes, who are more prone to periodontal disease, often underutilize preventive dental services and engage less in recommended oral hygiene practices [19,20]. Because diabetic patients are typically managed by multidisciplinary teams—including physicians, endocrinologists, dietitians, podiatrists, diabetes educators, and optometrists—each professional can reinforce oral health promotion [21]. Collectively, these examples show how IPC can close preventive and therapeutic gaps in oral–systemic health.

Beyond medical settings, community-based and social service professionals can play a role in oral health promotion. Older adults benefit when nonmedical service providers, such as home care aides or community nutrition programs, incorporate oral health assessments or referral prompts into their workflows [22]. Such intersectoral collaboration demonstrates that diverse professional networks can advance oral health more effectively than siloed care models [23]. Community–academic partnerships and extramural dental education rotations further expand access to care and foster IPC in underserved areas [24].

Dentists are also vital in detecting systemic conditions manifesting in the oral cavity. The U.S. Surgeon General’s report emphasizes their unique role in early disease identification [25]. For instance, dentists can detect signs of eating disorders and refer patients for medical and mental health evaluation [26]. Oral indicators such as halitosis, bleeding gums, or chronic inflammation may suggest diabetes [27]; bone loss in the jaw may indicate osteoporosis [28]; pallor of oral tissues or persistent ulcers may suggest anemia or nutritional deficiencies [29]; and recurrent oral yeast infections could indicate HIV [30]. Emerging evidence also highlights their role in identifying systemic complications of neurological diseases such as Parkinson’s, where oral dysfunction can accelerate overall decline [31]. These findings underscore the importance of integrating dental and medical providers through IPC.

Dentists also contribute to emergency and public health responses, participating in disaster teams and supporting immunization, triage, and preparedness efforts [32]. Effective IPC depends on trust, psychological safety, and shared mental models within healthcare teams [33]. Despite these benefits, dental–medical integration remains limited [13,34]. Barriers include insufficient resources, unclear role definitions, inadequate training, policy gaps, poor interdisciplinary education, and implementation challenges [35]. Time constraints during medical appointments [34] and the inability to share integrated electronic health records (i.e., the interoperable systems that allow medical and dental providers to access and exchange patient data in real time) further hinder collaboration [36].

Prior reviews offer insights into oral–systemic health and interprofessional education (IPE) but rarely examine how dentists are embedded within healthcare delivery teams. Rawlinson et al. [2] identify general IPC barriers (e.g., communication, role clarity, culture) but do not focus on dentistry. Khabeer et al. [37] and Alqutaibi et al. [38] examine IPE outcomes in dental education but not clinical practice. Thus, existing reviews stop short of analyzing operational models of interprofessional care involving dentists.

This review addressed that gap by examining the models, benefits, barriers, and facilitators of dentist integration into interprofessional healthcare teams in U.S. settings. This U.S. focus allowed a targeted examination of healthcare delivery systems shaped by similar policy, reimbursement, and technological infrastructures.

2. Methods

This scoping review was preregistered on the Open Science Framework (OSF; https://osf.io/76uzj, accessed on 9 September 2025) and utilized articles sourced from PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science—databases selected for their extensive and relevant collections of biomedical research on interprofessional collaboration. The scoping review approach was chosen because the evidence base on dental integration within interprofessional healthcare remains conceptually broad and methodologically diverse, spanning multiple study designs, populations, and care models. This approach allows for mapping the range, nature, and characteristics of existing research rather than evaluating intervention effectiveness, which aligns with the study’s exploratory objectives. Article selection followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) [39] guidelines, ensuring transparency and reproducibility. To assess methodological quality, we applied the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tool [40] for Scoping Reviews, which evaluates key domains such as study design appropriateness, data clarity, analytical rigor, and alignment between objectives and conclusions.

As detailed in Table 1, inclusion and exclusion criteria were established before data extraction. Inclusion criteria required studies to (1) be peer-reviewed; (2) focus on interprofessional healthcare teams involving dentists; (3) report benefits, challenges, or outcomes related to such collaboration; (4) be based on human subjects; and (5) be conducted in the United States (U.S.). Only studies published between 2014 and 2024 were included to ensure contemporary relevance. Accepted study designs included randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective clinical trials, case–control studies, cross-sectional studies, and case series or reports. Reviews, editorials, letters, conference abstracts, animal studies, and other secondary sources were excluded to maintain a focus on original research. Consistent with PRISMA-ScR guidance, we excluded purely educational IPE reports unless they directly examined clinical collaboration involving dental professionals.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for article selection.

As summarized in Table 2, tailored search terms were used across all three databases to identify relevant literature. In PubMed, search terms such as “interprofessional” and “multidisciplinary” were applied to locate studies addressing clinical outcomes and healthcare quality. In SCOPUS and Web of Science, the search incorporated terms like “interprofessional” and “interdisciplinary” with an emphasis on clinical outcomes involving dentists and dental specialists. All searches were restricted to English-language publications.

Table 2.

Summaries of the search strategies utilized for the three databases used in this study.

Two authors (MH and MT) independently screened all retrieved articles using a standardized screening form, identifying 25 from PubMed, 588 from SCOPUS, and 75 from Web of Science. These were then narrowed down to 20, 230, and 67, respectively, after excluding studies published before 2014. A secondary screening was conducted by the same two authors to ensure consistency in applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion, and unresolved discrepancies were adjudicated by a third reviewer. The final article selection was based on relevance to study design, types of healthcare sectors represented, reported challenges and benefits, and the outcomes described. To reduce bias, a third independent reviewer (AM) validated the final article selection and cross-checked extracted data for accuracy and completeness.

A standardized data-charting form was piloted to ensure consistency. Extracted variables included: author(s), year, study design, population, healthcare setting, team composition, outcomes assessed, and reported barriers/facilitators. Data were charted independently by two reviewers (MH and MT) and verified by a third (AM). This rigorous, multi-stage process ensured a transparent, reproducible synthesis of studies addressing the integration of dentists within interprofessional healthcare teams.

3. Results

3.1. Article Selection

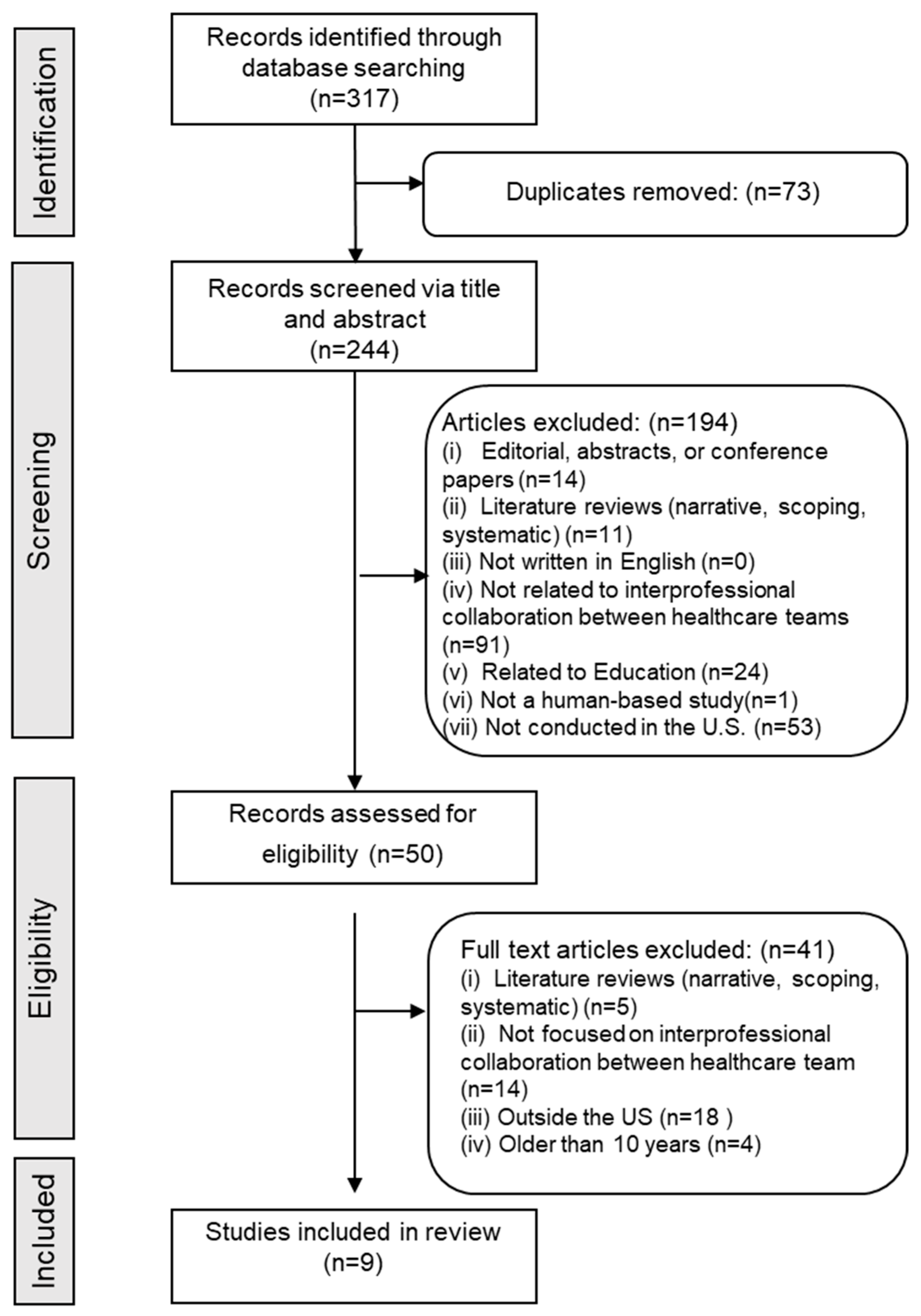

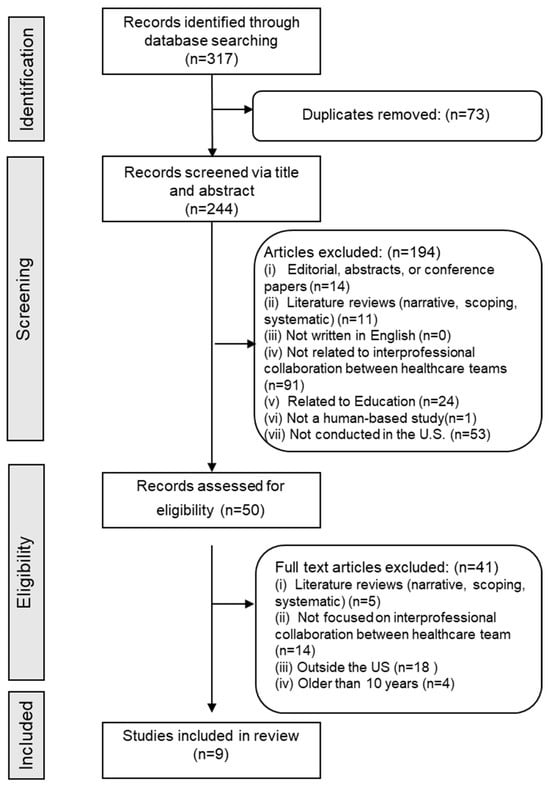

The PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (Figure 1) summarizes the article selection and screening. A total of 317 titles and abstracts were initially screened. After removing duplicates, 244 unique articles remained. These were reviewed, resulting in the exclusion of 194 articles for the following reasons: 14 were editorials, abstracts, or conference papers; 11 were literature reviews; 91 did not focus on interprofessional collaboration among healthcare teams; 1 was not based on human studies; 53 were conducted outside the U.S.; and 24 were related to education.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the article selection process.

Fifty articles were selected for full-text review. After a second round of screening, 41 additional articles were excluded: 5 were literature reviews; 14 did not examine interprofessional collaboration; 18 were conducted outside the U.S.; and 4 were published before 2014. Ultimately, nine studies met all inclusion criteria and were included in the final analysis (Figure 1).

3.2. Study Characteristics

Table 3 outlines the various types of IPC models identified across the nine included studies. Examples include partnerships among primary care providers (PCPs), nurses, and dentists, which reflect integrated teamwork within primary care. More complex interdisciplinary models, such as those involving PCPs, physician assistants, dentists, and dental hygienists, demonstrate the multifaceted nature of IPC and highlight ongoing efforts to enhance healthcare delivery through collaboration.

Table 3.

Different types of interprofessional collaboration identified.

Barriers to IPC (Table 4) were grouped into four domains: system level, organizational, inter-individual, and individual level. The most prevalent obstacles were organizational and inter-individual barriers, particularly the absence of shared EHR systems, limited role clarity, and communication breakdowns among providers. System-level challenges, such as inadequate training and limited policy support, were identified in three studies. Individual-level barriers, including low provider motivation or limited understanding of IPC value, were reported less frequently but remained relevant to implementation success.

Table 4.

Barriers to interprofessional collaboration.

Facilitators of IPC are presented in Table 5. Key enablers included the availability of funding and financial resources, supportive institutional and governmental policies, and the implementation of educational programs designed to promote collaboration within healthcare facilities. These factors were particularly influential in supporting models involving dentists, nurses, and primary care providers.

Table 5.

Facilitators of interprofessional collaboration.

Table 6 further details study characteristics, design, and participant demographics. Case reports accounted for 44% of included studies, ethnographies 22%, and cross-sectional designs 22% (Table 7). Participant ages ranged from 9 to 82 years, reflecting a broad spectrum of patient populations (Table 6). The studied health domains included oral-systemic disease links such as diabetes, sleep apnea, early childhood caries, general oral health integration, and pregnancy-related oral health (Table 7).

Table 6.

Summary of basic characteristics of the studies.

Table 7.

Distribution of studies by location, health condition, and study design.

3.3. Thematic Synthesis of Findings

The analysis of nine studies on IPC in healthcare highlighted multiple successes in integrating dentists into healthcare teams, yielding measurable benefits for patient well-being and care quality (Table 8).

Table 8.

Overview of studies examining interprofessional collaboration involving dental professionals.

Alexander et al. [43] reported a 98% reduction in apnea–hypopnea index scores and a 75% increase in quality-of-life scores among pediatric sleep apnea patients through interdisciplinary treatment. Similarly, Wood et al. [49] found that shared expertise within federally qualified health center teams improved patient outcomes and satisfaction, while Dolce et al. [41] demonstrated that the nurse practitioner–dentist model enhanced prevention, awareness, and education. These examples underscore the positive impact of collaborative healthcare models on patient health.

Gibson et al. [44] illustrated the clinical value of interdisciplinary collaboration in managing complex conditions such as cleft palate, where coordinated treatment among an orthodontist, periodontist, and general dentist improved both functional and aesthetic outcomes. Inglehart et al. [47] emphasized the importance of integrating oral health into holistic, patient-centered care—particularly during pregnancy—reinforcing the need to incorporate dental health into broader health management strategies.

Across studies, effective communication, shared learning, and cross-disciplinary education were identified as critical facilitators of safe, coordinated, and comprehensive care. These elements enable all providers to recognize the contribution of oral health to overall well-being and to collaborate more efficiently in addressing systemic health concerns. Despite these successes, persistent barriers continue to limit the full implementation of IPC involving dental professionals. Communication challenges remain prominent: Inglehart et al. [47] identified limited oral-health training among non-dental providers as a barrier to interdisciplinary care during pregnancy, while Horowitz et al. [45] reported insufficient engagement of hygienists and dentists in addressing early childhood caries, underscoring the need for improved communication and professional development. The absence of integrated EHR systems constrains responsiveness among providers and disrupts care continuity, whereas unclear professional roles and the lack of standardized protocols contribute to inconsistent patient management [49].

Knowledge gaps in systemic disease management, such as diabetes, were highlighted by Shimpi et al. [46], who emphasized the importance of integrated care frameworks and enhanced professional education. Referral inefficiencies also pose challenges; Long et al. [48] found that improving referral acceptance requires clearer triage protocols and strengthened interprofessional collaboration. Finally, Griffin et al. [42] and Dolce et al. [41] advocated for systemic interventions, including structured communication pathways and EHR integration, to facilitate seamless information exchange and coordination across care settings.

4. Discussion

This scoping review of nine studies on IPC highlights how integrating dentists into healthcare teams enhances patient outcomes and care coordination. The synthesis confirms the value of dental integration while identifying persistent organizational and policy barriers to widespread adoption. These findings are consistent with broader literature emphasizing that sustainable oral health integration must address both access disparities and system-level coordination challenges [24].

IPC consistently improved outcomes and continuity of care. Their significance does not just lie in the outcomes themselves but in the mechanisms enabling them—shared accountability, interdisciplinary communication, and patient-centered coordination. The evidence indicates that interprofessional models may help mitigate medical errors and enhance diagnostic accuracy, as clinical decisions are informed by diverse expertise. These findings also align with broader evidence demonstrating the importance of preventive oral health interventions, such as those evaluated by Lile et al. [50], who compared natural mouthrinses and chlorhexidine for plaque management, as part of a comprehensive, team-based approach to improving patient outcomes. This pattern is consistent with work in other domains, where improved team function—grounded in trust, psychological safety, and shared mental models—has been shown to enhance both patient and organizational outcomes across clinical settings [33]. Collectively, these benefits underscore the central role of oral health in whole-person care and support calls for stronger inclusion of dental professionals in primary and specialty healthcare teams.

The main barriers identified are interrelated system-level issues rather than isolated challenges. Fragmented communication, limited IPE, and non-interoperable EHRs persist as primary obstacles. Financial and policy misalignments, such as separate reimbursement structures, further restrict integration. These factors compound each other: inadequate training weakens understanding of oral–systemic connections, while data silos and unclear roles disrupt care continuity and efficiency. Overall, the issue is not conceptual support for IPC but the lack of enabling systems to implement it. Reforms in education, health information infrastructure, and policy alignment are essential to translate the demonstrated benefits of IPC into consistent, sustainable practice.

4.1. Implications

The findings of this review carry several important implications for healthcare practice, education, and policy. First, the demonstrated benefits of IPC affirm the need to embed oral health within broader medical and public health agendas. Health systems and educational institutions should promote shared training opportunities and team-based practice models that normalize collaboration among dentists, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and other providers.

Second, addressing the identified barriers requires multi-level strategies. At the institutional level, implementation of interoperable EHR systems is critical for enabling seamless data exchange and coordinated treatment planning. At the educational level, both medical and dental curricula should integrate interprofessional competencies and case-based training to foster communication and mutual understanding early in professional development. At the policy level, regulatory bodies and payers should incentivize interprofessional practice through shared reimbursement mechanisms, integrated quality metrics, and funding for team-based care pilots. Such approaches would help translate the conceptual value of IPC into operational practice.

Finally, research and evaluation frameworks should shift from descriptive case reporting to robust, mixed-method studies that quantify clinical and economic outcomes of interprofessional dental integration. This will strengthen the evidence base for policy and inform scalable implementation models.

4.2. IPE and Training Models

IPE is central to fostering the collaborative competencies necessary for effective integration of dental professionals within healthcare teams. The World Health Organization’s Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice (2010) [1] defines IPE as occasions when “students from two or more professions learn about, from, and with each other” to enable effective collaboration and improve health outcomes. This approach encourages the development of mutual understanding, respect, and communication across disciplines—skills that are essential for bridging the divide between oral and general healthcare.

Several U.S.-based models have demonstrated success in promoting oral–systemic collaboration. The Smiles for Life oral health curriculum, endorsed by the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, equips non-dental professionals with foundational knowledge of oral–systemic health and preventive oral care [51]. Similarly, studies by Reeves et al. [52] and Haber et al. [53] highlight the value of simulation-based and case-driven IPE interventions that improve teamwork, clinical communication, and shared accountability. These educational efforts align with calls from national organizations to strengthen interprofessional dental education and community-based learning as strategies for addressing access inequities and preparing a future workforce capable of collaborative care [24].

To strengthen IPC, educational institutions should incorporate oral health content into medical, nursing, and pharmacy curricula and expand team-based learning opportunities. Simulation exercises, joint clinical rotations, and problem-based learning modules can help future providers develop a shared understanding of oral–systemic interdependence. Embedding IPE across disciplines ensures that oral health is viewed as an integral component of comprehensive, patient-centered care.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

This scoping review has several strengths. It systematically identified and analyzed primary studies spanning multiple care settings and populations, providing a comprehensive overview of the current interprofessional practices involving dentists. The inclusion of diverse study designs, ranging from case reports to observational studies, allowed for triangulation of findings across contexts. The use of rigorous, pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, guided by the PRISMA-ScR framework, further enhances transparency and reproducibility.

However, limitations should be acknowledged. First, the review included studies published up to September 2024; therefore, more recent publications on this evolving topic may not have been captured. This reflects a standard practice in review methodology, where a defined cutoff ensures methodological consistency despite ongoing publication of new studies. The review was also limited to studies conducted within the U.S. and published in English, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to global contexts. This focus reflects the intention to analyze systems governed by similar reimbursement and regulatory structures but precludes insights from countries with more integrated health models (e.g., the U.K., Canada, or Australia). The findings primarily reflect systems shaped by U.S.-specific policy, reimbursement, and EHR infrastructures. Consequently, the generalizability of these results to countries with different healthcare financing or workforce models may be limited. However, several facilitators, such as role clarification, shared information systems, and interprofessional education, are broadly applicable across health systems. Additionally, the relatively small number of eligible studies and the predominance of descriptive designs constrain the ability to draw firm causal inferences about the impact of dentist integration. Few studies provided quantitative outcome measures or rigorous quality assessments, underscoring the need for future research employing controlled or longitudinal designs. Furthermore, while this review primarily examined provider-level collaboration, future research should incorporate patient perspectives to capture how interprofessional care is experienced at the individual level. Exploring patients’ perceptions of communication, continuity of care, satisfaction, and trust in collaborative healthcare environments would offer critical insights into the real-world impact of integrated dental–medical models. Qualitative and mixed-methods studies examining these experiences could inform strategies that enhance both patient engagement and the delivery of person-centered care.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review demonstrates that integrating dentists within interprofessional healthcare teams enhances diagnostic accuracy, preventive care, and patient satisfaction. However, current evidence base remains limited, with few large-scale or longitudinal studies evaluating the long-term impact of such collaboration.

Future work should move beyond descriptive designs to identify effective, scalable implementation strategies. Priorities include developing shared electronic health records, aligning reimbursement models, and embedding interprofessional education across health disciplines. By clarifying dentistry’s role within team-based care, future initiatives can strengthen oral–systemic integration and advance oral health as a core element of comprehensive healthcare.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.H.; methodology, M.H., W.C.B., M.T., C.S. and A.M.; software, M.H.; validation, M.H., W.C.B. and A.M.; formal analysis, M.H., W.C.B., M.T. and A.M.; investigation, M.H., W.C.B., M.T., C.S. and A.M.; resources, M.H., W.C.B. and A.M.; data curation, M.H., M.T., C.S. and A.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.H., W.C.B., M.T. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, M.H., W.C.B., M.T., C.S. and A.M.; visualization, M.H., C.S. and A.M.; supervision, M.H.; project administration, M.H.; funding acquisition, M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Clinical Outcomes Research and Education Center at Roseman University of Health Sciences for the support of the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education Collaborative Practice. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Rawlinson, C.; Carron, T.; Cohidon, C.; Arditi, C.; Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Peytremann-Bridevaux, I.; Gilles, I. An Overview of Reviews on Interprofessional Collaboration in Primary Care: Barriers and Facilitators. Int. J. Integr. Care 2021, 21, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glick, M.; Williams, D.M.; Kleinman, D.V.; Vujicic, M.; Watt, R.G.; Weyant, R.J. A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 915–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liccardo, D.; Cannavo, A.; Spagnuolo, G.; Ferrara, N.; Cittadini, A.; Rengo, C.; Rengo, G. Periodontal Disease: A Risk Factor for Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bansal, M.; Khatri, M.; Taneja, V. Potential role of periodontal infection in respiratory diseases—A review. J. Med. Life 2013, 6, 244–248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Phillips, K.E.; Hummel, J. Oral Health in Primary Care: A Framework for Action. JDR Clin. Transl. Res. 2016, 1, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, J.D.; Rozier, G.; Harris, R.; Lohr, K.N.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews. In Dental Caries Prevention: The Physician’s Role in Child Oral Health Systematic Evidence Review; Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US): Rockville, MD, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, J.; Gebel, C.; Vargas, C.; Geltman, P.; Walter, A.; Garcia, R.; Tinanoff, N. Listening to paediatric primary care nurses: A qualitative study of the potential for interprofessional oral health practice in six federally qualified health centres in Massachusetts and Maryland. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e014124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, J.; Berman, R.; Buse, K.; Doll, B.; Glick, M.; Metzl, J.; Touger-Decker, R. Achieving Oral Health for All through Public Health Approaches, Interprofessional, and Transdisciplinary Education. NAM Perspect. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuji, D.; Kritz-Silverstein, D.; Pham, H.; Chen, E.; Wu, Y.; Chan, W.Y. Opportunities for Age-Specific Interprofessional Collaboration Between Physicians and Dentists in Pediatric Patients. Pediatr. Dent. 2020, 42, 203–207. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, P.A.; Widmer-Racich, K.; Sevick, C.; Starzyk, E.J.; Mauritson, K.; Hambidge, S.J. Effectiveness on Early Childhood Caries of an Oral Health Promotion Program for Medical Providers. Am. J. Public Health 2017, 107, S97–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena, R.S.; Pesaressi, E.; Frencken, J.E. Reducing carious lesions during the first 4 years of life: An interprofessional approach. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 1004–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, V.H.; Collins, F.S.; D’Souza, R. Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges; National Institute of Health: Bethesda, MD, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, K.L.; Larsson, L.S. Interprofessional oral health initiative in a nondental, American Indian setting. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 2017, 29, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- da Silva, C.C.; Savian, C.M.; Prevedello, B.P.; Zamberlan, C.; Dalpian, D.M.; dos Santos, B.Z. Access and use of dental services by pregnant women: An integrative literature review. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moimaz, S.A.S.; Saliba, O.; Santos, K.T.D.; Queiroz, A.P.D.G.; Garbin, C.A.S. Prevalência de cárie dentária em gestantes atendidas no Sistema Único de Saúde em Município Paulista. Rev. Odontol. Araçatuba 2011, 32, 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- da Rosa, P.C.; Iser, B.P.M.; da Rosa, M.A.C.; de Slavutzky, S.M.B. Indicadores de saúde bucal de gestantes vinculadas ao programa de pré-natal em duas unidades básicas de saúde em Porto Alegre/RS. Arq. Em Odontol. 2007, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Acquaye, S.N.; Spatz, D.L. Professional Roles in Provision of Breastfeeding and Lactation Support: A Scoping Review. MCN Am. J. Matern. Child. Nurs. 2025, 50, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.; Genco, R.; Working Group 2 of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop*. Diabetes and periodontal diseases: Consensus report of the Joint EFP/AAP Workshop on Periodontitis and Systemic Diseases. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, S106–S112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Leveille, S.G.; Shi, L.; Camhi, S.M. Disparities in Preventive Oral Health Care and Periodontal Health Among Adults with Diabetes. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2021, 18, E47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, P.; Griffiths, R.; Wong, V.W.; Arora, A.; George, A. Knowledge and practices of diabetes care providers in oral health care and their potential role in oral health promotion: A scoping review. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2017, 130, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamut, S.; Boroumand, S.; Iafolla, T.J.; Adesanya, M.; Fazio, E.M.; Dye, B.A. Self-Reported Dental Visits Among Older Adults Receiving Home- and Community-Based Services. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2021, 40, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, B.N.; Johnson, C.D. Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: Working together for a better future. J. Chiropr. Educ. 2015, 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajendra, S.; Psoter, W. The Importance of Interprofessional Dental Care in the Community in the United States. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2025, 10, 17S–24S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General; National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, S.; Gopi-Firth, S. Eating disorders and the role of the dental team. Br. Dent. J. 2023, 234, 445–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, R.; Haque, M. Oral health messiers: Diabetes mellitus relevance. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2021, 14, 3001–3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Twardowski, S.E.; Wactawski-Wende, J. Chapter 55—Relationship between periodontal disease, tooth loss, and osteoporosis. In Marcus and Feldman’s Osteoporosis, 5th ed.; Dempster, D.W., Cauley, J.A., Bouxsein, M.L., Cosman, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 1381–1394. [Google Scholar]

- Velliyagounder, K.; Chavan, K.; Markowitz, K. Iron Deficiency Anemia and Its Impact on Oral Health—A Literature Review. Dent. J. 2024, 12, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritano, D.; Moreo, G.; Oberti, L.; Lucchese, A.; Di Stasio, D.; Conese, M.; Carinci, F. Oral Manifestations in HIV-Positive Children: A Systematic Review. Pathogens 2020, 9, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozas, N.S.; Sadowsky, J.M.; Jones, D.J.; Jeter, C.B. Incorporating oral health into interprofessional care teams for patients with Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2017, 43, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colvard, M.D.; Vesper, B.J.; Kaste, L.M.; Hirst, J.L.; Peters, D.E.; James, J.; Villalobos, R.; Wipfler, E.J. The Evolving Role of Dental Responders on Interprofessional Emergency Response Teams. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 60, 907–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leykum, L.K.; Khan, A.; Blakeney, E.A.-R.; Kennedy, K.C. Interprofessional Collaboration: Creating Effective Teams within and across Organizations. Med. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 109, 1009–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, J.; Phillips, K.D.; Holt, B.; Hayes, C. Oral Health: An Essential Component of Primary Care; Qualis Health: Seattle, WA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harnagea, H.; Couturier, Y.; Shrivastava, R.; Girard, F.; Lamothe, L.; Bedos, C.P.; Emami, E. Barriers and facilitators in the integration of oral health into primary care: A scoping review. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e016078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Manjunath, C.; Murthy, A.K.; Sampath, A.; Jaiswal, S.; Mohapatra, A. Integration of oral health into primary health care: A systematic review. J. Fam. Med. Prim. Care 2019, 8, 1838–1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khabeer, A.; Faridi, M.A. Interprofessional Education in Dentistry: Exploring the Current Status and Barriers in the United States and Canada. Cureus 2024, 16, e72768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqutaibi, A.Y.; Rahhal, M.M.; Awad, R.; Sultan, O.S.; Iesa, M.A.M.; Zafar, M.S.; Jaber, M. Foundations of Interprofessional Education in Dental Schools: A Narrative Review. Eur. J. Dent. 2025, 19, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O′Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JBI. Critical Appraisal Tools. Available online: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Dolce, M.C.; Barrow, J.; Jivraj, A.; Pham, D.; Da Silva, J.D. Interprofessional value-based health care: Nurse practitioner-dentist model. J. Public. Health Dent. 2020, 80 (Suppl. S2), S44–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, A.; Brain, P.; Hancock, C.; Jeyapalina, S. A Dentist’s Perspective on the Need for Interdisciplinary Collaboration to Reduce Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw. Sr. Care Pharm. 2022, 37, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, N.; Boota, A.; Hooks, K.; White, J.R. Rapid Maxillary Expansion and Adenotonsillectomy in 9-Year-Old Twins with Pediatric Obstructive Sleep Apnea Syndrome: An Interdisciplinary Effort. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc. 2019, 119, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.F.; Mandelaris, G.A. Restoration of the Anterior Segment in a Cleft Palate in Conjunction with Surgically Facilitated Orthodontic Therapy: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 59, 733–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horowitz, A.M.; Kleinman, D.V.; Child, W.; Radice, S.D.; Maybury, C. Perceptions of Dental Hygienists and Dentists about Preventing Early Childhood Caries: A Qualitative Study. J. Dent. Hyg. 2017, 91, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Shimpi, N.; Glurich, I.; Panny, A.; Acharya, A. Knowledgeability, attitude, and practice behaviors of primary care providers toward managing patients’ oral health care in medical practice: Wisconsin statewide survey. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2019, 150, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, M.R.; Albino, J.; Feine, J.S.; Okunseri, C. Sociodemographic Changes and Oral Health Inequities: Dental Workforce Considerations. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2022, 7, 5s–15s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, C.M.; Quinonez, R.B.; Rozier, R.G.; Kranz, A.M.; Lee, J.Y. Barriers to pediatricians’ adherence to American Academy of Pediatrics oral health referral guidelines: North Carolina general dentists’ opinions. Pediatr. Dent. 2014, 36, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed Central]

- Wood, M.; Gurenlian, J.; Freudenthal, J.; Cartwright, E. Interprofessional Health Care Delivery: Perceptions of oral health care integration in a Federally Qualified Health Center. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 94, 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Lile, I.E.; Hajaj, T.; Veja, I.; Hosszu, T.; Vaida, L.L.; Todor, L.; Stana, O.; Popovici, R.A.; Marian, D. Comparative Evaluation of Natural Mouthrinses and Chlorhexidine in Dental Plaque Management: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Healthcare 2025, 13, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglass, A.B.; Gonsalves, W.; Maier, R.; Silk, H.; Stevens, N.; Tysinger, J.; Wrightson, A.S. Smiles for Life: A National Oral Health Curriculum for Family Medicine. A model for curriculum development by STFM groups. Fam. Med. 2007, 39, 88–90. [Google Scholar]

- Reeves, S.; Fletcher, S.; Barr, H.; Birch, I.; Boet, S.; Davies, N.; McFadyen, A.; Rivera, J.; Kitto, S. A BEME systematic review of the effects of interprofessional education: BEME Guide No. 39. Med. Teach. 2016, 38, 656–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, J.; Hartnett, E.; Allen, K.; Hallas, D.; Dorsen, C.; Lange-Kessler, J.; Lloyd, M.; Thomas, E.; Wholihan, D. Putting the mouth back in the head: HEENT to HEENOT. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 437–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).