Abstract

Introduction: Ambiguous loss is a profound yet underexplored phenomenon in the lives of aging migrants. Older adults who have experienced migration often face disruptions to their sense of belonging, identity, and continuity across borders. These losses are compounded by aging, health challenges, and social isolation. Despite its significance, ambiguous loss among aging migrants has not been conceptually analyzed in depth, limiting the development of culturally responsive care practices. Aim: This concept analysis aimed to identify the defining attributes of ambiguous loss among aging migrants and to develop a conceptual definition that enhances our understanding of the phenomenon and informs future research and practice. Method: Walker and Avant’s eight-step concept analysis framework was applied to examine the concept of ambiguous loss in the context of aging migrants. A systematic keyword search was conducted across four databases (CINAHL, Medline, SCOPUS, PsycINFO), Google Scholar, and relevant gray literature, covering the years of 2010–2024. Covidence software supported the screening process. From 367 records identified, 146 underwent full-text review, and 74 met inclusion criteria. The analysis drew on literature synthesis, case exemplars, antecedents, consequences, and empirical referents. This review followed PRISMA (2020) reporting guidelines. Results: Four defining attributes of ambiguous loss among aging migrants were identified: (a) physical, social, and emotional loss; (b) displacement and loss of homeland; (c) erosion of social identity and agency; and (d) cultural and transnational bereavement. A conceptual definition emerged, describing ambiguous loss as a multifaceted experience of disconnection, intensified by aging, illness, economic hardship, and social isolation. The analysis also highlighted antecedents such as forced migration and health decline, as well as consequences including diminished well-being, resilience challenges, and barriers to integration. Conclusions: Ambiguous loss among aging migrants is a complex construct encompassing intertwined physical, social, and cultural dimensions of loss. This conceptual clarity provides a foundation for developing culturally responsive care models that promote adaptation, resilience, and social inclusion among older migrants.

1. Introduction

By mid-2020, an estimated 34.3 million migrants aged 65+ made up 12.2% of the global migrant population, with their numbers increasing by nearly 16 million in different countries [1]. Aging migrants are the fastest growing segment of the elderly population in Europe and North America [2]. An aging migrant is a foreign-born older adult who migrated in late life at age 65 or near retirement—whether through family reunification or forced displacement—and is now experiencing retirement while displaced in the host country [1]. In the past decade, over two-thirds of migrant deaths remain unidentified, leaving families and communities enduring uncertainty and ambiguous loss [3]. As migration rates rise and the proportion of aging migrants grows, ambiguous loss has become a key focus in understanding the psychological and social well-being of older adults [4]. Ambiguous loss is a profound psychological experience characterized by uncertainty and lack of closure regarding relationships, identity, and belonging [5,6]. Unlike concrete losses, such as the death of a loved one, ambiguous loss lacks closure and resolution [7], making it difficult for migrants to process and adapt. This phenomenon is especially relevant to aging migrants, who face prolonged separation from their homeland and family, as well as psychological disconnection due to cultural transitions and acculturation challenges [8]. Ambiguous loss in aging migrants is significant due to the psychological and emotional challenges of permanent uncertainty, unfinished loss, and the lack of closure [4,7]. Ambiguous loss in aging migrants extends beyond physical loss to include identity and belonging, as migration leads to the gradual loss of their original sense of self, traditions, and autonomy [8,9]. According to Perez and Arnold-Berkovits [10]), ambiguous loss may be associated with post immigration stress that is more intense for those of forced displacement due to sickness, aging, or financial instability.

Ambiguous loss arises when a person disappears or is psychologically absent, producing enduring uncertainty with psychological, social, economic, and administrative consequences. In the Mediterranean migration crisis, this affects families who remain behind or await relatives’ arrival [11]. For instance, families experience prolonged ambiguous loss—loved ones absent yet psychologically present—moving from anticipation to disappearance, searching, and chronic unknowing [12]. In Arizona and Sonora, this uncertainty triggers headaches, insomnia, anxiety, depression, and chronic disease, underscoring the need for system-level, culturally responsive support [12].

Unresolved losses associated with changes in family grieving process [13] and migration elevate the risks of depression, loneliness, and identity dissonance among aging migrants, affecting their overall quality of life and integration into host societies [2,14]. Ambiguous loss includes two main types impacting migrants’ well-being. Physical ambiguous loss occurs when someone is physically absent but psychologically present, such as older parents separated from their children by migration [7]. This type of loss is common among migrants unable to return to their homeland due to political, economic, or personal reasons, resulting in lasting emotional distress and a longing for reunification [8,10,15]. The second, psychological ambiguous loss, manifests when an individual is physically present but emotionally or cognitively absent, as commonly seen in aging migrants experiencing dementia, mental illness, or the erosion of cultural identity [16]. Many aging migrants experience both forms of ambiguous loss simultaneously, compounding their distress, complicating their adaptation to new environments, and challenging their sense of belonging [8,9,16].

Coping strategies for ambiguous loss among aging migrants encompass psychological adaptation, social support, and meaning making [16,17]. Studies indicate that transnational communication, maintaining strong ethnic community ties, and engaging in cultural or religious practices serve as protective factors against emotional distress [9,10,18]. For many aging migrants, religious beliefs and practices provide a source of continuity and resilience, reinforcing a sense of belonging and stability amidst the uncertainties of migration [19]. Additionally, the concept of both/and thinking, where individuals acknowledge both loss and presence; has been associated with greater emotional stability and adaptive coping [17]. Maladaptive coping mechanisms, like avoidance, emotional suppression, or idealizing the homeland, can result in prolonged grief, identity fragmentation, and difficulty integrating into host communities [18,20]. Interventions for ambiguous loss focus on cognitive reframing, community support, and culturally tailored mental health services [17]. Therapy models based on ambiguous loss theory emphasize increasing tolerance for uncertainty, recognizing that closure may not be possible [7]. Group therapies have been effective in validating experiences and fostering shared understanding, reducing isolation, and building resilience [21,22]. Language acquisition programs promote psychological well-being by enhancing social integration and access to healthcare [20,23].

Healthcare providers, particularly nurses, play a pivotal role in addressing the holistic care needs including emotional and psychological needs of aging migrants experiencing ambiguous loss [24]. Nurses can support family reunification, strengthen social networks, and implement psychoeducational programs to help aging migrants navigate the complexities of ambiguous loss [2]. Transcultural nursing care, which incorporates migrants’ beliefs, languages, and social norms, is instrumental in delivering effective and culturally competent interventions [10]. Training healthcare providers in cultural competence ensures care strategies meet the unique needs of migrant populations, improving their healthcare access and overall psychological well-being [20].

To translate this concept into practice, we position nursing as the point-of-care interface where ambiguous loss is most visible and actionable among aging migrants (home care, primary/community care, long-term care). Drawing on relational, culturally safe, grief- and trauma-informed principles, nursing operationalizes the concept’s antecedents, attributes, and consequences within interprofessional, community-anchored systems [16,25]. This orientation clarifies how assessment, communication, and pathway coordination can mitigate boundary ambiguity, disenfranchised grief, and social isolation.

As ambiguous loss continues to shape the lived experiences of aging migrants, further research is needed to explore its intersections with mental health, migration, social integration, and nursing care [26,27,28]. Existing literature highlights the importance of resilience, community belonging, and culturally sensitive interventions [2,17,29], yet gaps remain in understanding how healthcare systems can better support aging migrants experiencing ambiguous loss. This analysis will inform nursing interventions designed to enhance the well-being of aging migrants, contributing to the development of culturally sensitive and evidence-based nursing practices. This paper aims to (1) analyze and conceptually define ambiguous loss among aging migrants and (2) develop a conceptual model that links ambiguous loss among aging migrants with nursing care for older migrants.

2. Materials & Method

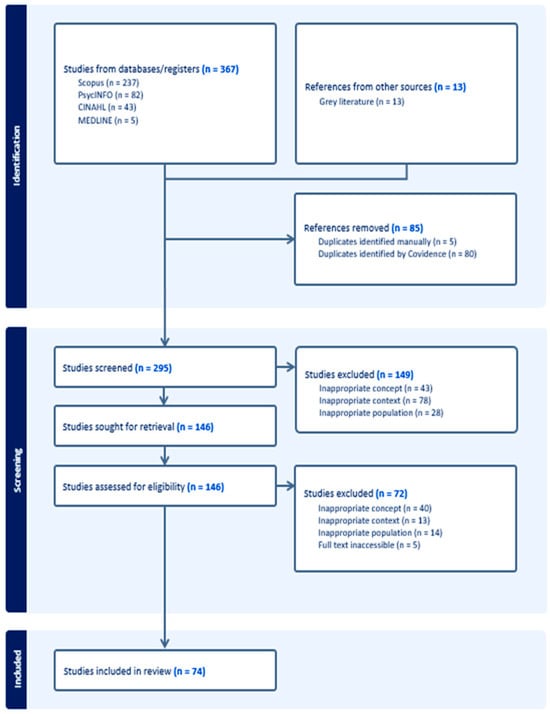

Our analysis applied the Walker and Avant [30] concept analysis framework, which is widely applied in nursing to systematically clarify underdeveloped concepts. This framework was selected because of its structured eight-step process, which strengthens theoretical precision and facilitates translation into nursing practice [30]. These steps include (1) identifying the concept of interest, (2) establishing the purpose of the analysis, (3) examining various uses of the concept, (4) outlining its defining characteristics, (5) constructing model cases that exemplify the concept, (6) identifying borderline and contradictory cases, (7) exploring antecedents and consequences, and (8) determining empirical indicators. This concept analysis adheres to the PRISMA (2020) reporting guidelines for systematic reviews. We applied Walker and Avant’s [30] concept analysis as the main methodological framework. PRISMA/PRISMA-ScR elements were used only to document and report the search and selection process (Figure 1), not as a study design. We conducted the concept analysis following Walker and Avant’s framework and interpreted the resulting attributes/antecedents through a nursing care lens to outline system-embedded assessment and intervention touchpoints [30].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

2.1. Identifying the Concept and Search Strategy

The analysis began by defining key terms using various dictionaries (see Table 1), followed by a review of literature on “ambiguous loss,” “older adults,” and “migration.” A comprehensive search was conducted across multiple databases, developed in collaboration with a research librarian. The search used broad keywords, refined with MeSH terms and adapted for each database using Boolean operators and wildcards. To ensure accuracy, the strategy was reviewed by a second librarian following PRESS guidelines [31]. The finalized search strategy is detailed in (Appendix A). A cross-disciplinary uses (nursing, gerontology, migration studies, psychology, anthropology, social work) was conducted to ensure a comprehensive search and to prevent construct overlap and to delineate the boundaries of ambiguous loss. See Table 1 for the defining and distinguishing related constructs including migratory loss and grief and transnational bereavement.

Table 1.

Term definitions and relevant concepts.

2.2. Screening Process

The review identified 367 records from databases including CINAHL (n = 43), Medline (n = 5), SCOPUS (n = 237), PsycINFO (n = 82), and Google Scholar (n = 13), limited to publications from 2010 to 2024. After removing 85 duplicates and incomplete entries, 295 records were screened. Three reviewers (LY, SA, AZ) independently assessed titles and abstracts, with discrepancies resolved by discussion or a third reviewer (AA). Of these, 149 were excluded, and 146 full-text articles were reviewed. Following eligibility assessment, 72 were excluded, resulting in 74 studies included in the final review. No additional sources were identified through reference list checks. Eligibility criteria were: (a) population/focus on aging migrants and/or their caregivers/providers addressing ambiguous loss in later life; (b) concept relevance defined as explicit discussion of ambiguous loss or closely related constructs (see Table 1) linked to aging/migration; (c) host-country health, social, or community contexts; and (d) empirical or theoretical/conceptual peer-reviewed articles (editorials/letters excluded unless providing definitional clarity). Records were limited to English due to team language fluency and lack of translation funds; the date range was unrestricted with an emphasis on recent literature. We followed the PRISMA-ScR guidelines [36] to ensure a systematic and transparent literature review, supporting rigorous record selection, synthesis, and strengthening the concept’s theoretical foundation and relevance to practice. The PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) illustrates the entire search and selection process.

2.3. Analysis

Titles and abstracts were first screened for eligibility, followed by full-text reviews based on inclusion criteria. Using inductive content analysis [37]. Three reviewers (LY, SA, AZ) independently coded all included sources using inductive content analysis in NVivo. A shared codebook—containing operational definitions, inclusion/exclusion notes, and exemplar excerpts—was developed and iteratively refined. Coding disagreements were resolved by consensus, with a third reviewer (YY) adjudicating unresolved items, and an audit trail of decisions and analytic memos was maintained. We also included a brief reflexivity statement to acknowledge team positionality and steps taken to minimize bias. The findings were organized into attributes, antecedents, consequences, and empirical referents. Model and supporting cases were developed from literature these cases were derived from published literature and synthesized to exemplify defining attributes and boundaries and authors’ practice experience served only for ecological plausibility checks. Ethical approval was not required.

Our team includes researchers with prior work in migration, aging, and bereavement. We recognize that our practice-oriented lens could foreground care-system solutions and nursing perspectives. To minimize bias, we bracketed assumptions through independent double-coding, iterative codebook development, consensus adjudication with third-reviewer input, and an audit trail of analytic decisions/memos. We also triangulated definitions across disciplines and explicitly distinguished related constructs to reduce construct overlap.

3. Results

3.1. Term Definitions and Relevant Concepts

To understand “ambiguous loss among aging migrants,” it is useful to define key terms and examine related concepts. The literature reveals varied terminology describing similar experiences. This review clarifies the term aging migrant and explores related concepts, migratory loss and grief and transnational bereavement, highlighting their theoretical distinctions and evolution over time (see Table 1).

3.2. Defining Attributes

According to Walker and Avant [30], attributes represent the fundamental traits that define a concept, making it distinguishable from related ideas.

Physical, Social and Emotional Loss: Physical loss among older migrants includes the loss of possessions [38], land [39], housing and financial resources [40,41], increasing reliance on social capital [38]. Social loss involves disruptions in networks, such as losing a spouse [42,43], family [44,45], friends [46], caregivers [47], and employers [48], often due to death [49,50] or migration [51]. Older migrant women may feel loneliness after losing male authority figures [39,52]. Emotional loss accompanies these physical and social losses, including declining self-confidence [44] regret after bereavement [53], and emotional effects of childhood separations, such as rootlessness and guilt [54].

Loss of Homeland and Displacement: Loss of homeland due to forced displacement often results from threats to personal safety, including war, conflict, violence, and political persecution [4,38,39,45,55]. Contributing factors include regime changes, government corruption [39], and environmental crises such as climate change, pollution, and natural disasters [56]. Displacement leads to cultural losses, including loss of heritage, shared culture, and language [4,45], often resulting in migratory grief [57]. In response, migrants remake a sense of home in host countries through cultural practices and community engagement [4].

Loss of Social Identity and Agency: Migration often leads to the loss of social roles for older migrants, causing devaluation and disempowerment, especially among men who lose leadership roles [45,52,58,59]. Many adopt nontraditional roles, but culture shock and lifestyle changes disrupt identity [46,60]. An inability to continue traditional practices, like farming, further challenges identity [60]. Loss of home ownership and independence, as seen in older Chinese migrants, reduces autonomy [40]. Older African migrants also struggle with identity renegotiation due to forced displacement [61]. Discrimination, ageism, and declining health further impact social identity and increase reliance on family support [42,47,62].

Cultural and Transnational Bereavement: Cultural bereavement involves grieving the loss of social structures, identity, and cultural practices due to being uprooted from one’s homeland [60]. Korean and Egyptian migrants, for example, experience the erosion of cultural identity and traditions during acculturation [39,57]. This grief is often tied to cultural trauma and fears about losing language, religion, and customs across generations [60]. Transnational bereavement occurs when migrants grieve distant losses without traditional mourning rituals, leading to disenfranchised grief, guilt, and isolation [49,63]. Migrants may rely on digital communication for transnational caregiving, while children and kin often take on roles as mediators of care and mourning across borders [38,48,63].

3.3. Identifying Model, Borderline and Contrary Cases

In concept analysis, Walker & Avant [30] emphasize the use of illustrative cases to clarify meaning and boundaries of a concept. A model case represents the concept in its most complete form, demonstrating all of its defining attributes and showing readers exactly what the phenomenon looks like in practice [30]. In contrast, a borderline case includes only some of the defining attributes, which helps highlight situations that share partial features of the concept but do not fully represent it [30]. Finally, a contrary case contains none of the defining attributes and therefore illustrates what the concept is not [30]. Together, these cases function as practical tools for sharpening conceptual clarity, allowing scholars and practitioners to distinguish the essential elements of a phenomenon from its partial or unrelated forms. To illustrate the concept of ambiguous loss among aging migrants, the authors constructed model, borderline, and contrary cases, as presented in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Model and additional cases of “ambiguous loss among aging migrants”.

3.4. Antecedents

According to Walker and Avant [30] concept analysis method, antecedents are the prior events or conditions that must be in place for a concept to develop or take form. The following discusses the antecedents of ambiguous loss among aging migrants:

Physical Aging and Frailty: Physical aging among older migrants involves losses such as sensory decline [42], memory loss from dementia [64,65], hearing loss [66], immobility [47], and disability [59,67]. Frailty, chronic illness, and cognitive decline reduce independence and self-identity [10,20,44,68]. These issues often stem from past hardships like war, forced displacement, and limited healthcare access [61,69]. Cognitive decline leads to psychological absence, affecting familial relationships and emotional well-being [20,60]. Language attrition further isolates older migrants, deepening ambiguous loss and disconnect from both past and present identities [62,70,71,72].

Economic Strain and Detachment: Aging migrants often face economic insecurity due to disrupted career paths, low-paying jobs, and limited pension eligibility [68,73,74]. These financial pressures increase dependence on family, leading to feelings of burdensomeness and reduced autonomy [18]. Economic hardship also limits access to healthcare, forcing reliance on community services that may lack cultural sensitivity [72,75]. Social isolation is intensified by language barriers, cultural differences, and the loss of support networks from the home country, resulting in emotional distress and a sense of detachment [45,76,77].

Shifting Family Dynamics and Caregiving: Older adults, respected for guiding younger generations, experience a loss of status and decision-making power due to migration, especially when children adopt Western caregiving models [8,18,70]. This shift can create intergenerational tension, leaving aging migrants feeling undervalued and disconnected [55,58]. As filial piety erodes, institutional care and reduced family support may follow [4,69]. Transnational caregiving also causes emotional distress from physical separation [63]. Older women, in particular, experience greater losses in status and autonomy due to changing gender roles [59]. These evolving caregiving structures often lead to cultural tensions between independence and familial duty, intensifying feelings of ambiguous loss [4,49].

Changing Cultural, Aging and Grief Rituals: Cultural adaptation poses significant challenges for aging migrants as they balance preserving their cultural identity with adapting to new societal norms [60,72]. This often leads to the gradual loss of traditional values, creating internal conflict, emotional distress, and identity struggles [61,62,71]. Difficulty adapting can increase anxiety and depression due to displacement and social exclusion [75,78]. Migration disrupts traditional mourning practices, preventing participation in meaningful rituals like visiting ancestral graves or holding funerals, deepening the sense of loss [4,49,50,79]. Aging migrants often report feeling unsupported due to the lack of culturally sensitive end-of-life care in host countries [63,72].

3.5. Consequences

According to Walker and Avant [30] concept analysis method, consequences are the outcomes or effects that follow the occurrence of the concept being analyzed, highlighting its results or implications. The following are the consequences of ambiguous loss among aging migrants:

Strained Family Ties and Generational Tensions: Weakened family ties and intergenerational tensions are common among aging migrants due to cultural shifts, language barriers, and migration-related separation. Transnational caregivers often feel guilt and distress over unmet caregiving expectations [2,8]. Older immigrants report strained relationships as younger generations adopt host country values [18,45,51]. Refugee elders face isolation and reversed caregiving roles, relying on younger relatives for daily support, which can lead to resentment and loss of autonomy [4,20,58,60]. Historical trauma among post-war migrants further disrupts intergenerational bonds where past experiences remain unspoken [39,54].

Declined Health with Limited Care Access: Older immigrants and refugees face declining physical and mental health, with limited care access, report poor social support and increased vulnerability [51], and elders with hearing loss struggle due to stigma and financial barriers [66]. Refugees experience PTSD and depression linked to language and financial issues [58]. Environmental and economic stressors, including COVID-19, have worsened mental health [56,80]. Loss of social networks from forced migration adds emotional strain [76]. Language barriers and inadequate healthcare contribute to loneliness and poor disease management [10,18,81].

Increased Loneliness, Isolation and Grief: Older immigrants with spousal bereavement, facing cultural and linguistic barriers that hinder emotional support, leading to prolonged grief and isolation [82]. Latino immigrants experience ambiguous loss of their homeland and contributing to social withdrawal [10]. Hmong older immigrants report loneliness due to loss of cultural identity and intergenerational disconnection [52]. Similarly, Muslim immigrants experience existential loneliness from losing religious and communal spaces [62]. Bhutanese refugee elders face cultural trauma and bereavement, intensifying isolation and distress [60]. These cumulative losses lead to avoidant behaviors, further reinforcing cycles of loneliness and grief [75,83].

Heightened Displacement and Diminished Belonging: Bhutanese refugee elders face cultural trauma in exile, leading to loss of identity and disconnection [60]. Cuban American exiles experience ambiguous loss of their homeland, deepening cultural fragmentation and nostalgia [10]. Older Italian migrants in Australia struggle with intergenerational family ties, reinforcing their outsider status [42]. Southeast Asian refugees in the U.S. feel distanced from their children due to acculturation gaps, intensifying familial tensions [58]. Forced migration strains social networks, as seen among Japanese immigrant widows navigating bereavement in cultural marginalization [50]. Syrian refugees experience ongoing mourning due to the inability to return home [4]. Hmong elders report loneliness from disrupted cultural continuity and intergenerational misunderstandings [52,55]. Mizrahi women in Tel Aviv reflect on their eroded cultural presence due to shifting communal structures [79]. These experiences highlight how displacement affects identity and deepens cultural grief [18,76].

3.6. Empirical Referents

Empirical referents are observable indicators that align with a concept’s defining attributes, helping to identify and measure its presence in practice as explained by Walker& Avant [30]. For aging migrants, empirical referents of “ambiguous loss” include: Perez and Arnold-Berkovits [10] categorize migrants based on their levels of ambiguous loss of homeland (ALH) and relative satisfaction (RS) with their host country, considering how nostalgia, homesickness, and socio-political factors influence their experiences. Segmented Assimilation theory by Poryes and Zhou Min [84] explains how migrants integrate into new societies at different rates, with some achieving upward mobility and inclusion, while others face systemic barriers and persistent uncertainty. The psychological impact of migration can also be understood through the Continuity Theory of Normal Aging [85] that suggests that individuals strive to maintain a consistent sense of self despite external disruptions, such as migration. Disengagement Theory [86] posits that aging individuals naturally withdraw from previous roles and relationships, a process heightened for older migrants who feel disconnected from both their homeland and host society. Stress and Coping Theories [87], explores how individuals manage stressful situations, including cultural displacement and legal precarity, and the emotional toll of migration. Additionally, FRAIL Scale [88] is a valuable tool for assessing physical and cognitive vulnerabilities. Psychosocial distress related to ambiguous loss can also be measured using the Social Screening Scale [89] which evaluates risk factors such as sadness, outside activity, cognition, income adequacy, attachment to neighbors, and lethargy.

3.7. Model Development

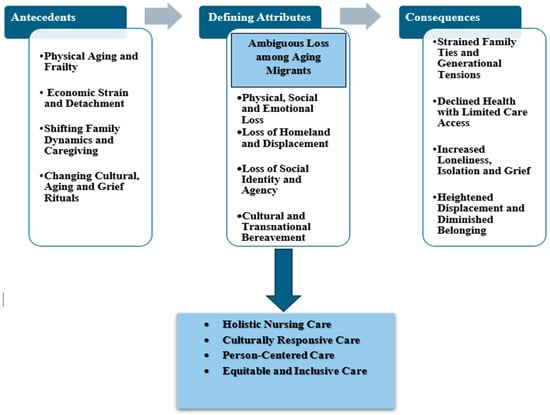

Having established the defining attributes, antecedents, and consequences of ambiguous loss among aging migrants, we now translate these elements into a conceptual model. The model specifies the pathways by which contextual moderators (e.g., migration trajectory, language access) shape the expression of attributes and the downstream consequences and identifies system touchpoints for assessment and support.

Drawing on the defining attributes outlined in the existing literature, ambiguous loss among aging migrants can be conceptualized as a multifaceted experience marked by physical, social, and emotional loss, displacement, diminished identity, and cultural bereavement. Rooted in aging-related frailty, chronic illness, and cognitive decline, it is intensified by economic hardship, social isolation, and shifting family roles. Struggles with cultural adaptation and changing mourning rituals deepen feelings of displacement, weakened identity, and loss of belonging, leading to loneliness, grief, avoidant behaviors, strained family ties, and declining health.

Having delineated the defining attributes (e.g., boundary ambiguity, chronic sorrow, ambivalence) and antecedents (e.g., separation, role disruption, legal/linguistic barriers), we map these elements to system touchpoints where nursing actions occur within interprofessional pathways: (a) language access and therapeutic communication, (b) navigation and continuity, (c) grief-/trauma-informed mental-health supports, and (d) community linkage and social prescribing. Where language discordance is an antecedent, nurses ensure routine use of professional interpreters, enabling accurate assessment of ambiguous loss and safer care [90]. When legal/organizational barriers contribute to antecedents (eligibility gaps, fragmented referrals), nurses coordinate “no-wrong-door” navigation and continuity with primary care and settlement services [25,91]. For attributes such as disenfranchised grief or hypervigilance, nurses initiate screening, brief interventions, and stepped-care referrals within interprofessional teams [16,25]. Where isolation sustains consequences, nurses connect clients to culturally meaningful groups and social-prescribing options, with attention to equity and evaluation [92].

Having established the concept’s antecedents, attributes, and consequences, we synthesize these elements into a conceptual model that specifies pathways and system touchpoints, directly informed by and traceable to the analysis by Walker & Avant. A conceptual model for ambiguous loss among aging migrants and nursing care is proposed, illustrating its defining attributes, antecedents, consequences, and connection to core nursing principles (Figure 2). The model emphasizes the attributes at the heart of aging migrants’ experiences, framed by antecedents necessary for the concept’s emergence. The consequences of these attributes are then linked to the core principles of nursing care for older adults highlighting the importance of holistic, person-centered, culturally responsive, and inclusive care in addressing ambiguous loss.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model for ambiguous loss among aging migrants and nursing care for older migrants.

4. Discussion

The aim of this concept analysis was to explore the defining attributes of ambiguous loss among aging migrants, develop a clear definition, and propose a model illustrating its factors and outcomes. Key attributes include physical, social, and emotional loss, loss of homeland, social identity, and cultural bereavement. As shown in the model (Figure 2), these attributes stem from antecedents like aging, economic strain, family dynamics, and shifting cultural practices. Consequences may include strained family ties, health decline, isolation, and diminished belonging. The model emphasizes holistic, person-centered, culturally responsive care, highlighting how nurses can address the emotional and social needs of aging migrants. This analysis draws on literature focused on ambiguous loss in aging and migration contexts. While the term is gaining recognition, definitions and applications remain inconsistent across studies [17,20]. This analysis synthesizes existing literature and aligns it with nursing practices for older adults, offering a clearer understanding of ambiguous loss among aging migrants. Further development can be achieved by linking the concept to nursing theories and practices, ensuring that care models address the diverse experiences and needs of aging migrants.

When applying this concept analysis to aging migrants, it is important to consider that the relevance of ambiguous loss may vary based on the nature of the loss [17]. Aging migrants experience unresolved grief over lost loved ones and homeland [93], traditions, oscillating between hope, mourning, and assimilation in their new society [11]. These losses are intensified by life’s discontinuity, making aging migrants more vulnerable as they idealize the past while trying to create a sense of home in a new environment [2]. Ambiguous loss, such as uncertainty around social security, war, or abduction, affects aging migrants with family in their homeland, leading to guilt and increased risk of depression and anxiety due to their inability to support loved ones [10]. The loss of agency, control over health, and inability to engage in traditional mourning rituals contribute to significant psychological distress for aging migrants [2]. Ambiguous loss, often a lifelong process [10], can have a significant psychological impact, leading to fatigue, depression, and exacerbating comorbidities among aging migrants especially those from diverse ethnic backgrounds [94]. Shen [18] highlights that processing ambiguous loss and migratory grief is complex for the elderly, as they may suppress pain to avoid feeling burdensome. Addressing this loss is crucial for social inclusion, mental well-being, and culturally adaptive coping, as grief varies across ethnicities [10]. Culturally safe communication and recognition of their experiences can help aging migrants navigate loss and, in some cases, reclaim their identities [11]. Aging migrants’ well-being is influenced by discriminatory policies and their control over their new lives and their grief is often dismissed, with expectations of assimilation [10].

Older migrants with limited English proficiency experience worse health outcomes, highlighting the need for nurses to communicate in their native language to improve care and well-being [8]. Identity loss can foster worthlessness and social isolation, particularly among older migrants, as it often goes unrecognized [18]. Aging migrants’ diminished sense of purpose, compounded by language barriers, dependency, family conflict, and the dual burden of hope and mourning, fosters silent grief and accelerates their decline [20]. Additionally, older migrants play a vital yet often overlooked role in society through unpaid household labor, lacking social identity or personal pursuits [95]. Their heightened risk for chronic illnesses and mental health challenges emphasizes the need for nurses to monitor their well-being and ensure proper support systems [94]. Social support is vital in easing suffering, restoring purpose, and helping aging migrants manage ambiguous loss by allowing them to release grief and personal burdens [18]. Mazzarelli et al. [11] emphasize the need for an ethno-psychological approach in nursing care, requiring cultural humility [96] to understand migrants’ mourning and coping within their specific contexts. By providing culturally sensitive care [96], mental health support and embracing an anti-ageist and anti-racist approach, nurses can assist aging migrants in achieving a sense of closure, peace and well-being [97].

4.1. Systemic Barriers and Health-System Responsibilities in Addressing Ambiguous Loss

Although our definition encompasses voluntary, family-reunification, and forced migration, ambiguous loss is not experienced uniformly. The migration trajectory modulates both antecedents and attributes. In conflict-related or forced displacement, antecedents more often include acute trauma, legal precarity, and prolonged separation with disrupted communication, attributes commonly present as boundary ambiguity, hypervigilance, and disenfranchised grief. In family reunification, antecedents tend to involve bureaucratic delays, role renegotiation, and transnational caregiving; attributes include ambivalence, role confusion, and intergenerational tension. In labor/education-driven migration, antecedents may include circular mobility and economic obligations; attributes often manifest as chronic homesickness and identity liminality amid relatively stable ties. These variations underscore the need to tailor assessment and support to sociocultural context and migration pathway.

Ambiguous loss among aging migrants rooted in separation from people/places and the uncertainty of return—manifests as boundary ambiguity, chronic sorrow, and disenfranchised grief [4,98]. Access to care is constrained by structural and informational barriers, including limited knowledge of entitlements, language discordance, eligibility gaps, cost, and mistrust, which delay help-seeking and intensify antecedents and attributes of ambiguous loss [91]. A system response is therefore required. Scholars argued that the WHO’s Integrated People-Centred Health Services framework supports community-anchored, coordinated models that embed proactive outreach with settlement/faith partners, “no-wrong-door” navigation, and co-located primary, mental-health, and social services [25]. Routine language access using professional interpreters improves safety, quality, and utilization [90]. Community-linking interventions such as social prescribing may help rebuild meaning and connection but should be implemented with equity safeguards and ongoing evaluation [92]. Within this larger effort, nursing roles include public/community health and Nurse Practitioner-led outreach and navigation; gerontological nursing for screening, caregiver support, and continuity; and mental-health/psychiatric nursing for grief- and trauma-informed care ideally integrated with community organizations and interpreter services.

4.2. Nursing Core Principles for Working with Older Migrants

Addressing ambiguous loss requires system-level redesign embedded interpretation, coordinated navigation, and community-partnered care so that nursing contributions (public/community health, gerontological, and mental-health nursing) operate within integrated pathways rather than isolated encounters [25,91]. Embedding these functions in routine practice clarifies role boundaries, improves access, and aligns with the concept’s emphasis on continuity of ties and meaning reconstruction [16].

Holistic, culturally responsive, person-centered, and equitable care approaches are essential in supporting aging migrants who experience ambiguous loss. Holistic nursing care acknowledges not only physical health but also the psychological, emotional, and cultural disruptions older migrants face due to displacement and identity shifts [24]. By integrating strategies like reminiscence therapy for loneliness [22], life review therapy [21], and spiritual support [99], nurses can help aging migrants find meaning in their experiences while promoting their resourcefulness [100] and continuity of identity [101]. Culturally responsive care complements this approach by recognizing the importance of cultural beliefs, languages, and practices in shaping how aging migrants’ express grief and cope with separation or dislocation [102]. When nurses incorporate culturally meaningful traditions such as religious practices, native language use, or community ties into care plans [29], they foster emotional safety and connection, while also reducing feelings of invisibility and cultural alienation [103]. In parallel, person-centered care emphasizes the individual’s narrative, values, and lived experiences [104]. For aging migrants, who often face fragmented family ties and shifting social roles [105], this approach respects their autonomy and acknowledges the depth of their loss [26]. Nurses can enhance engagement by tailoring care strategies to each individual’s cultural background, communication style, and emotional needs [106]. Equitable and inclusive care ensures that access to quality healthcare is not limited by age, migration status, language, or socioeconomic factors [107,108]. Many aging migrants face systemic barriers such as language inaccessibility, legal precarity, and discrimination [109,110], which exacerbate feelings of isolation and loss [111]. Nurses play a pivotal role in advocating for inclusive services such as interpreter support and culturally tailored programming [100] while affirming diverse expressions of grief [2]. Collectively, these interwoven nursing approaches offer compassionate, responsive and supportive frameworks [15] for addressing the complex emotional and cultural realities of ambiguous loss among aging migrants.

The developed model is tentative and intended to guide assessment and care, not to claim a fully validated theory. Future work should (1) qualitatively test pathway plausibility across migration trajectories and contexts; (2) develop/adapt empirical referents (e.g., boundary-ambiguity indicators) with psychometric evaluation; (3) conduct feasibility and mixed-methods studies of interpreter-enabled navigation, grief-informed groups, and role-clarification interventions; and (4) use longitudinal designs to examine changes in ambiguous loss attributes and consequences with targeted supports.

4.3. Implications

The findings of this concept analysis highlight the urgent need for tailored, culturally sensitive nursing models to support aging migrants experiencing ambiguous loss. Nurses working with older migrants must be equipped to address the complex interplay of psychological distress, cultural bereavement, and social isolation among this population [2,17]. Integrating holistic [24], person-centered [106,112,113], culturally responsive and equitable care [114] can promote emotional resilience and foster belonging [115]. Health systems should prioritize language access, intergenerational support strategies, and health services tailored to migrants’ diverse backgrounds [20]. Furthermore, training healthcare providers in cultural humility and trauma-informed approaches will strengthen inclusive care practices and mitigate identity loss and marginalization [10,18]. Nurses can use this model to enhance aging migrants’ well-being and address the long-term effects of ambiguous loss. Future research should focus on developing tailored care models that address the intersection of aging, migration and loss, [28], ensuring that healthcare services remain inclusive and responsive to the needs of aging migrant population.

The developed model is tentative and intended to guide assessment and care, not to claim a fully validated theory. Future work should: (1) qualitatively test pathway plausibility across migration trajectories and contexts; (2) develop/adapt empirical referents (e.g., boundary-ambiguity indicators) with psychometric evaluation; (3) conduct feasibility and mixed-methods studies of interpreter-enabled navigation, grief-informed groups, and role-clarification interventions; and (4) use longitudinal designs to examine changes in ambiguous loss attributes and consequences with targeted supports.

4.4. Limitations

This analysis is limited to English-language literature, potentially excluding non-English perspectives. Perceptions of ambiguous loss may vary by cultural background and migration experience, affecting the generalizability of findings. While the proposed model offers a useful framework, it requires further empirical testing. Future research should explore ambiguous loss in diverse cultural contexts to refine the model. Despite these limitations, this analysis provides valuable insights for advancing the field.

5. Conclusions

Ambiguous loss among aging migrants is shaped by physical, social, and emotional displacement, the loss of identity, and cultural bereavement. This analysis highlights the psychological and health impacts of unresolved grief, isolation, and changing family dynamics. Nurses play a vital role in addressing these effects through holistic, culturally responsive, and person-centered care. This concept analysis offers a clearer definition of ambiguous loss among aging migrants, identifies four defining attributes and key antecedents/consequences, and organizes these elements into a practice-oriented conceptual model. Centering AL—rather than a general catalog of losses—clarifies why boundary ambiguity, disenfranchised grief, liminality/chronic sorrow, and ambivalence co-occur under sustained uncertainty and where practice can intervene. By fostering inclusive healthcare, nurses can help aging migrants navigate loss, regain agency, and maintain a sense of belonging. In sum, a nursing-led, system-enabled approach grounded in language access, navigation, grief/trauma-informed care, and community linkage operationalizes the concept of ambiguous loss for aging migrants and strengthens equity-oriented practice.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare13202606/s1, Data Extraction Table [116,117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128,129,130].

Author Contributions

A.A.-H. conceptualized and designed the study, provided oversight throughout the review process, and contributed to the manuscript’s development. A.Z., L.Y. and S.A. conducted the literature search, screened titles and abstracts, performed full-text reviews, and extracted relevant data using Covidence software. They also carried out the initial coding and thematic analysis. Y.M.Y. served as a third reviewer to resolve disagreements at all stages of data search, study selection, data extraction, and analysis. A.A.-H. and Y.M.Y. provided critical revisions to the manuscript, ensuring alignment with the study objectives and methodological rigor. All authors contributed to writing, reviewing, and approving the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statements

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

Special appreciation goes to the research team members for their valuable insights.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Refined Search Strategy with the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) Terms

| Ambiguous Loss Concepts | Older Adult Terms | Migration Terms |

| Loss | “Older adult” | “Migrant” |

| “Ambiguous loss” | “Aging” | “Refugee” |

| “Unresolved loss” | “Elderly” | “Displaced person” |

| “Non-death loss” | “Senior” | “Asylum seeker” |

| “Migration and loss” | “Older person” | “Immigrant” |

| “Psychosocial loss” | “Geriatrics” | “Undocumented migrant” |

| “Physical loss” | “Late-life” | |

| “Family separation” | ||

| “Loss and identity” |

Appendix B. Database Search

| Database | Interface | Search String | Limiters | Findings |

| Medline | Ovid | (“Loss” or “Ambiguous loss” or “Unresolved loss” or “Non-death loss” or “Migration and loss” or “Psychosocial loss” or “Physical loss” or “Family separation” or “Loss and identity”) AND (Migrant* or Refugee* or “Displaced person*” or “Asylum seeker*” or Immigrant* or “Undocumented migrant*”) AND (“Older adult$” or Aging or Elderly or Senior$ or “Older person$” or Geriatrics or “Late-life”).mp. [mp = title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | limit 4 to (English language and yr = “2010”) | 5 |

| CINAHL | EBASCOhost | (“loss” OR “Ambiguous loss” OR “Unresolved loss” OR “Non-death loss” OR “Migration and loss” OR “Psychosocial loss” “Physical loss” OR “Family separation” OR “Loss and identity”) AND (Migrant? OR Refugee? OR “Displaced person?” OR “Asylum seeker?” OR Immigrant? OR “Undocumented migrant?”) AND (“Older adult$” OR Aging OR Elderly OR Senior$ OR “Older person$” OR Geriatrics OR “Late-life”) | Publication Date: 20100101-; English Language | 43 |

| PsycINFO | EBASCOhost | (“loss” OR “Ambiguous loss” OR “Unresolved loss” OR “Non-death loss” OR “Migration and loss” OR “Psychosocial loss” “Physical loss” OR “Family separation” OR “Loss and identity”) AND (Migrant? OR Refugee? OR “Displaced person?” OR “Asylum seeker?” OR Immigrant? OR “Undocumented migrant?”) AND (“Older adult$” OR Aging OR Elderly OR Senior$ OR “Older person$” OR Geriatrics OR “Late-life”) | Publication Date: 20100101-; English Language | 82 |

| Scopus | Scopus (Elsevier) | (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Loss” OR “Ambiguous loss” OR “Unresolved loss” OR “Non-death loss” OR “Migration and loss” OR “Psychosocial loss” OR “Physical loss” OR “Family separation” OR “Loss and identity”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(Migrant* OR Refugee* OR “Displaced person*” OR “Asylum seeker*” OR Immigrant* OR “Undocumented migrant*”)) AND (TITLE-ABS-KEY(“Older adult*” OR Aging OR Elderly OR Senior* OR “Older person*” OR Geriatrics OR “Late-life”)) | Publication Date: 20100101-; English Language | 237 |

References

- Migration Data Portal. Older Persons and Migration. Available online: https://www.migrationdataportal.org/themes/older-persons-and-migration (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Nesteruk, O. Immigrants coping with transnational deaths and bereavement: The influence of migratory loss and anticipatory grief. Fam. Process 2018, 57, 1012–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerwin, D.; Martínez, D.E. Forced migration, deterrence, and solutions to the non-natural disaster of migrant deaths along the US-Mexico border and beyond. J. Migr. Hum. Secur. 2024, 12, 127–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunn, M.; Samuels, G.; Higson-Smith, C. Ambiguous loss of home: Syrian refugees and the process of losing and remaking home. Wellbeing Space Soc. 2023, 4, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauline, B.; Boss, P. Ambiguous loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nathanson, A.; Rogers, M. When Ambiguous Loss Becomes Ambiguous Grief: Clinical Work with Bereaved Dementia Caregivers. Health Soc. Work 2020, 45, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P. The trauma and complicated grief of ambiguous loss. Pastor. Psychol. 2010, 59, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solheim, C.; Zaid, S.; Ballard, J. Ambiguous Loss Experienced by Transnational Mexican Immigrant Families. Fam. Process 2016, 55, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solheim, C.; Williams-Wengerd, A.; Kodman-Jones, C.; Burke, K.; St James, C.; Lewis, M.; Sherman, M. Ambiguous loss: A focus on immigrant families, postincarceration family life, addiction and families, and military families. In Treating Contemporary Families: Toward a More Inclusive Clinical Practice; Browning, S.W., Eeden-Moorefield, B.M.V., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; pp. 187–218. [Google Scholar]

- Perez, R.M.; Arnold-Berkovits, I. A conceptual framework for understanding Latino immigrant’s ambiguous loss of homeland. Hisp. J. Behav. Sci. 2018, 40, 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzarelli, D.; Bertoglio, B.; Boscacci, M.; Caccia, G.; Ruffetta, C.; De Angelis, D.; Fracasso, T.; Baraybar, J.; Riccio, S.; Marzagalia, M.M.; et al. Ambiguous loss in the current migration crisis: A medico-legal, psychological, and psychiatric perspective. Forensic Sci. Int. Mind Law 2021, 2, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocker, R.M.; Reineke, R.C.; Tovar, M.E.R. Ambiguous loss and embodied grief related to Mexican migrant disappearances. Med. Anthropol. 2021, 40, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betz, G.; Thorngren, J.M. Ambiguous Loss and the Family Grieving Process. Fam. J. 2006, 14, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.C. Migratory Loss and Depression Among Adult Immigrants of Chinese Descent. Ph.D. Thesis, Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Klochok, G.; Herrera-Espiñeira, C. The grief of relatives of missing migrants and supportive interventions: A narrative review. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 1023–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boss, P. Building resilience: The example of ambiguous loss. In Approaches to Psychic Trauma: Theory and Practice; Huppertz, B., Ed.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, C.M.; Boss, P. Ambiguous loss: Theory-based guidelines for therapy with individuals, families, and communities. In The Handbook of Systemic Family Therapy; Wampler, K.S., Rastogi, M., Singh, R., Eds.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y. Adult Relatives’ Understandings of the Migratory Loss Experiences of Their Chinese Immigrant Elders and Their Support Strategies. Master’s Thesis, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia, 2019. Available online: https://flex.flinders.edu.au/file/04fbcdf0-8062-472f-88e3-2b388329c9a0/1/ThesisShen2019OA.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Wayland, S.; Myfanwy, M.; Kathy, M.; Glassock, G. Holding on to hope: A review of the literature exploring missing persons, hope and ambiguous loss. Death Stud. 2016, 40, 54–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S. Ambiguous Loss, Boundary Ambiguity, and English Learning: How Immigrants’ Functionality is Impacted by Language Proficiency. Ph.D. Thesis, Bellarmine University, Louisville, KY, USA, 2020. Available online: https://scholarworks.bellarmine.edu/tdc/94 (accessed on 25 August 2025).

- Lin, J.; Zhao, R.; Li, H.; Lei, Y.; Cuijpers, P. Looking back on life: An updated meta-analysis of the effect of life review therapy and reminiscence on late-life depression. J. Affect. Disord. 2024, 347, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, S.M.S.; Neville, C.; Scott, T. The effectiveness of group reminiscence therapy for loneliness, anxiety and depression in older adults in long-term care: A systematic review. Geriatr. Nurs. 2015, 36, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dakey, S.K.; Maxwell, H.; Siette, J. Towards cultural inclusion for older adults from culturally and linguistically diverse communities: A commentary on recent aged care reforms. Australas. J. Ageing 2025, 44, e13384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdi, K.; Talebi, R. Holistic nursing from the Dossey’s theory of integral nursing lens: A narrative review study. J. Nurs. Educ. 2023, 12, 88–103. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafiz, O.; Yin, X.; Sun, S.; Yang, J.; Liu, H. Examining the use and application of the WHO integrated people-centred health services framework in research globally–a systematic scoping review. Int. J. Integr. Care 2024, 24, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torensma, M.; de Voogd, X.; Oueslati, R.; van Valkengoed, I.G.M.; Willems, D.L.; Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B.D.; Suurmond, J.L. Care and decision-making at the end of life for migrants living in the Netherlands: An intersectional analysis. J. Migr. Health 2025, 11, 100293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K.M.; Prus, S.G. Examining the gender, ethnicity, and age dimensions of the healthy immigrant effect: Factors in the development of equitable health policy. Int. J. Equity Health 2012, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatia, P.; McLaren, H.; Huang, Y. Exploring social determinants of mental health of older unforced migrants: A systematic review. Gerontol. 2024, 64, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordes, C.C. Culturally responsive refugee and migrant health. Fam. Syst. Health 2021, 39, 670–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, L.O.; Avant, K.C. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing; Pearson Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan, J.; Sampson, M.; Salzwedel, D.M.; Cogo, E.; Foerster, V.; Lefebvre, C. PRESS peer review of electronic search strategies: 2015 guideline statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 75, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam-Webster, Ambiguous. ed.; Hachette Book Group: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Loss. ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025.

- The American Heritage Dictionary, Aging. ed.; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- The American Heritage Dictionary, Migrant. ed.; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2025.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyngäs, H. Inductive Content Analysis. In The Application of Content Analysis in Nursing Science Research; Kyngäs, H., Mikkonen, K., Kääriäinen, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Brandhorst, R. Older Vietnamese refugees’ transnational digital social capital and its impact on social inclusion. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2024, 50, 4642–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho Kim, S.; Manchester, C.; Lewis, A. Post-war immigration experiences of survivors of the Korean war. J. Aggress. Maltreatment Trauma 2019, 28, 977–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, W.-W.; Garcia, A. Later life migration: Sociocultural adaptation and changes in quality of life at settlement among recent older Chinese immigrants in Canada. Act. Adapt. Aging 2015, 39, 214–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, Y.K.; Mazumdar, S. Feeling at home: Korean Americans in senior public housing. J. Aging Stud. 2011, 25, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandhorst, R. Transnational ageing, intergenerational family ties and the social embedding of older Italian migrants in Australia. In Handbook of Transnational Families Around the World; Cienfuegos, J., Brandhorst, R., Bryceson, D.F., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 187–202. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H. My last husband and marriage: The impact of inheritance disputes on Chinese immigrants’ widowhood in the United States. Ageing Int. 2022, 47, 653–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.; Gee, S.; Jamieson, H.A.; Bergler, H.U. Correction to: What is frailty? Perspectives from chinese clinicians and older immigrants in New Zealand. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2021, 36, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, S.D. Perceptions of Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL) Experienced by Older Ethnic Somalis Aging Transculturally in the US: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Ph.D. Thesis, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA, 2021. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/perceptions-health-related-quality-life-hrqol/docview/2597467318/se-2 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- George, M.; Fitzgerald, R.P. Forty years in Aotearoa New Zealand: White identity, home and later life in an adopted country. Ageing Soc. 2012, 32, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeboah, C.; Barbara, B.; Rolls, C. Culturally and linguistically diverse older adults relocating to residential aged care. Contemp. Nurse 2013, 44, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babis, D. Digital mourning on Facebook: The case of Filipino migrant worker live-in caregivers in Israel. Media Cult. Soc. 2021, 43, 397–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinkson, G.M.; Huggins, C.L.; Doyle, M. Transnational Caregiving and Grief: An Autobiographical Case Study of Loss and Love During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Omega-J. Death Dying 2024, 90, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, C. Bereavement and meaning reconstruction among Japanese immigrant widows: Living with grief in a place of marginality and liminality in the United States. Pastor. Psychol. 2014, 63, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Au, A.; Hilario, C.; Meherali, S.; Salma, J.; Collins, T. Unveiling social belonging: Exploring the narratives of immigrant muslim older women. Health Soc. Care Community 2024, 2024, 5598247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, C.; Sieng, M.; Zheng, M. Conceptualizing loneliness among a Hmong older adult group: Using an intersectionality framework. Asian Am. J. Psychol. 2023, 14, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, O.E.; Ryu, S. Content and intensity of pride and regret among Asian American immigrant elders. Illn. Crisis Loss 2017, 25, 309–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilala, C.; Santavirta, N. Unveiling the war child syndrome: Finnish war children’s experiences of the evacuation to Sweden during WWII from a lifetime perspective. J. Loss Trauma 2016, 21, 575–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, C.; Thor, P.; Sieng, M. Influencing factors of loneliness among Hmong older adults in the premigration, displacement, and postmigration phases. J. Refug. Stud. 2021, 34, 3464–3485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayalon, L.; Ulitsa, N.; AboJabel, H.; Engdau-Vanda, S. “We used to have four seasons, but now there is only one”: Perceptions concerning the changing climate and environment in a diverse sample of Israeli older persons. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2024, 43, 527–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Girgis, I. The Immigration Experience among Elderly Egyptian Immigrants in the United States. Ph.D. Thesis, City University of New York United States, New York, NY, USA, 2015. Available online: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1957&context=gc_etds (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Dubus, N. “I feel like her daughter not her mother”: Ethnographic trans-cultural perspective of the experiences of aging for a group of Southeast Asian refugees in the United States. J. Aging Stud. 2010, 24, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Chan, D. The making of ageing migrant masculinities: Loss and recuperation in the lived experiences of Chinese and Korean older adult migrant men. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2025, 51, 1928–1943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H.; Neff, J. Spiral loss of culture: Cultural trauma and bereavement of Bhutanese refugee elders. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2021, 19, 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilpeläinen, F.; Zechner, M. Displaced selves: Older African adults in forced migration. J. Refug. Stud. 2022, 35, 1126–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, N.; Carri, H.; Rudman, D.L. Aging Muslim immigrants transitioning from Muslim majority countries to Muslim minority countries: A scoping review addressing dynamics of occupation, place, and identity. J. Occup. Sci. 2024, 31, 606–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Leon, C.; Blower-Nassiri, J. Aging Filipina migrants’ experiences of transnational end-of-life care and loss over time. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2024, 47, 3064–3083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iris, M.; Schrauf, R.W. Aging, memory loss, and Alzheimer’s disease: What do refugees from the former Soviet Union think? J. Relig. Spiritual. Aging 2017, 29, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.E.; Lee, H.Y.; Diwan, S. What do Korean American immigrants know about Alzheimer’s disease (AD)? The impact of acculturation and exposure to the disease on AD knowledge. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.S.; Shim, K.S.; Kim, K.; Nieman, C.L.; Mamo, S.K.; Lin, F.R.; Han, H.R. Understanding hearing loss and barriers to hearing health care among Korean American older adults: A focus group study. J. Appl. Gerontol. 2018, 37, 1344–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strong, J.; Varady, C.; Chahda, N.; Doocy, S.; Burnham, G. Health status and health needs of older refugees from Syria in Lebanon. Confl. Health 2015, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, D. Ageing ‘on the Edge’: Later-Life Migration in the Azores. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton and Hove, UK, 2018. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.23453489.v1 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Nashwan, A.; Cummings, S.M.; Gagnon, K. Older female Iraqi refugees in the United States: Voices of struggle and strength. Int. Soc. Work 2019, 62, 653–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, J.Y.; Lee, H. Barriers to and facilitators of diabetes self-management with elderly Korean-American immigrants. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, D.; Belford, N.; Lahiri-Roy, R. Transnational daughters in Australia: Caring remotely for ageing parents during COVID 19. Emot. Space Soc. 2022, 42, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paal, P.; Bükki, J. “If I had stayed back home, I would not be alive any more…”—Exploring end-of-life preferences in patients with migration background. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, R.; Waters, M.C. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older latino immigrants. RSF Russell Sage Found. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guha, P.; Islam, B.; Hussain, M.A. COVID-19 lockdown and penalty of joblessness on income and remittances: A study of inter-state migrant labourers from Assam, India. J. Public Aff. 2021, 21, e2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.; Bacsu, J.; McIntosh, T.; Jeffery, B.; Novik, N. Social isolation and loneliness among immigrant and refugee seniors in Canada: A scoping review. Int. J. Migr. Health Soc. Care 2019, 15, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekoh, P.C.; Iwuagwu, A.O.; George, E.O.; Walsh, C.A. Forced migration-induced diminished social networks and support, and its impact on the emotional wellbeing of older refugees in Western countries: A scoping review. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2023, 105, 104839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Weiyu, M.; Man, G.; Ling, X.; Iris, C.; Dong, X. Loss of friends and psychological well-being of older Chinese immigrants. Aging Ment. Health 2021, 25, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forte, A.; Trobia, F.; Gualtieri, F.; Lamis, D.A.; Cardamone, G.; Giallonardo, V.; Fiorillo, A.; Girardi, P.; Pompili, M. Suicide Risk among Immigrants and Ethnic Minorities: A Literature Overview. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamur, T. Age melancholy of older Mizrahi women residing in Tel Aviv as a social loss: Exploring intersections of health and social support in an ethnographic study. Qual. Health Res. 2025, 35, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton-Jeangros, C.; Duvoisin, A.; Lachat, S.; Consoli, L.; Fakhoury, J.; Jackson, Y. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown on the health and living conditions of undocumented migrants and migrants undergoing legal status regularization. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 596887. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, J.; Sjögren-Forss, K.; Bramhagen, A.-C.; Rämgård, M. Voices Unheard: A Reflective Lifeworld Research Study of Older Arabic-Speaking Female Migrants and Their Experience of Existential Loneliness. Int. J. Older People Nurs. 2024, 19, e12633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Walsh, C.A.; Tong, H. The lived experiences of spousal bereavement and adjustment among older Chinese immigrants in Calgary. J. Cross-Cult. Gerontol. 2023, 38, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Mack, S.; Yiwei, C.; Dong, X. Kinship bereavement and psychological well-being of U.S. Chinese older women and men. J. Women Aging 2022, 34, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poryes, A.; Min, Z. The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. Ann. Am. Acad. Political Soc. Sci. 1993, 530, 74–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atchley, R.C. A continuity theory of normal aging. Gerontol. 1989, 29, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cumming, M.E. New thoughts on the theory of disengagement. In New Thoughts on Old Age; Kastenbaum, R., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1964; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R.; Folkman, S. Stress and coping. New York 1985, 18, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E. The Frail Brain. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2013, 14, 453–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmstrom, T.K.; Morley, J.E. Frailty and cognition: Linking two common syndromes in older persons. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2013, 17, 723–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karliner, L.S.; Jacobs, E.A.; Chen, A.H.; Mutha, S. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res 2007, 42, 727–754. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, M.M.; Holliday, D.D.; Weinhardt, L.S.; Florsheim, P.; Ngui, E.; AbuZahra, T. Barriers and facilitators of health among older adult immigrants in the United States: An integrative review of 20 years of literature. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 755. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerdike, L.; Booth, A.; Wilson, P.M.; Farley, K.; Wright, K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013384. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.M. Paradise lost: Older Cuban American exiles’ ambiguous loss of leaving the homeland. J. Gerontol. Soc. Work 2013, 56, 596–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuittinen, S.; Mölsä, M.; Punamäki, R.-L.; Tiilikainen, M.; Honkasalo, M.-L. Causal attributions of mental health problems and depressive symptoms among older Somali refugees in Finland. Transcult. Psychiatry 2017, 54, 211–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.; Lerche, J. Migration and the invisible economies of care: Production, social reproduction and seasonal migrant labour in India. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2020, 45, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiszko, K.B. Cultural considerations for comprehensively assessing foreign born older adults in the United States. Curr. Geriatr. Rep. 2024, 13, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazan, H. On the Cultural Origins of Ageism. In Age into Race: The Coronization of the Old; Hazan, H., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar]

- Doka, K. Disenfranchised Grief: New Directions, Challenges, and Strategies for Practice, 1st ed.; Research Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2002; pp. 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, K.; Konaszewski, K.; Skalski, S.B.; Büssing, A.; Surzykiewicz, J. Spiritual Needs, Religious Coping and Mental Wellbeing: A Cross-Sectional Study among Migrants and Refugees in Germany. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hamad, A.; Yasin, Y.M.; Rahman, R.; Hayrabedian, V.; Metersky, K. Resourceful aging among migrants and refugees: A concept analysis and model development for holistic nursing care. J. Holist. Nurs. 2025; online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, P.S. Continuity, change and possibility in older age: Identity and ageing-as-discovery. J. Sociol. 2018, 54, 178–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseba Achotegui, M.D. Migrants living in very hard situations: Extreme migratory mourning (the ulysses syndrome). Psychoanal. Dialogues 2019, 29, 252–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallio, K.P.; Häkli, J. Trapped in (In)visibility: Contested Intercorporeality in Undocumented migrants’ Lives. Geopolitics 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, P.; Alajarmeh, S.; Alarjeh, G.; Alrjoub, W.; Al-Essa, A.; Abusalem, L.; Giusti, A.; Mansour, A.H.; Sullivan, R.; Shamieh, O. Providing person-centered palliative care in conflict-affected populations in the Middle East: What matters to patients with advanced cancer and families including refugees? Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1097471. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, R.; David, C.; Vitale, T. Beyond ethnic solidarity: The diversity and specialisation of social ties in a stigmatised migrant minority. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2022, 48, 3113–3141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, B.; McCance, T. Person-Centred Practice in Nursing and Health Care: Theory and Practice; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Maleku, A.; Megan, E.; Shannon, J.; Sharvari, K.; Parekh, R. We Are Aging Too! Exploring the Social Impact of Late-Life Migration among Older Immigrants in the United States. J. Immigr. Refug. Stud. 2022, 20, 365–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.C.-Y.; Newendorp, N. How age and life stage of relocation fosters social belonging: Comparing two groups of older migrants in the United States. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 2023, 79, gbad071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambushe, S.A.; Awoke, N.; Demissie, B.W.; Tekalign, T. Holistic nursing care practice and associated factors among nurses in public hospitals of Wolaita zone, South Ethiopia. BMC Nurs. 2023, 22, 390. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theodosopoulos, L.; Fradelos, E.C.; Panagiotou, A.; Dreliozi, A.; Tzavella, F. Delivering culturally competent care to migrants by healthcare personnel: A crucial aspect of delivering culturally sensitive care. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taiebine, M.; Marfak, A.; Al Hassani, W.; Nejjari, C. Cross-cultural barriers and facilitators of dementia care in Arabic-speaking migrants and refugees: Findings from a narrative scoping review. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2024, 25, 101498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filler, T.; Jameel, B.; Gagliardi, A.R. Barriers and facilitators of patient centered care for immigrant and refugee women: A scoping review. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arola, A.; Dahlin-Ivanoff, S.; Häggblom-Kronlöf, G. Impact of a person-centred group intervention on life satisfaction and engagement in activities among persons aging in the context of migration. Scand. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 27, 269–279. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, Z.; Patel, H.; Wijk, H.; Ekman, I.; Olaya-Contreras, P. A systematic review on implementation of person-centered care interventions for older people in out-of-hospital settings. Geriatr. Nurs. 2021, 42, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanengoni-Nyatara, B.; Watson, K.; Galindo, C.; Charania, N.A.; Mpofu, C.; Holroyd, E. Barriers to and recommendations for equitable access to healthcare for migrants and refugees in Aotearoa, New Zealand: An integrative review. J. Immigr. Minor. Health 2024, 26, 164–180. (In English) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.W. Art in health and identity: Visual narratives of older Chinese immigrants to New Zealand. Arts Health 2012, 4, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabandla, N.; Marchetti-Mercer, M.C.; Human, L. Meaning and Experience of International Migration in Black African South African Families. Contemp. Fam. Ther. 2023, 45, 475–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.; Ahmad, N.; Jolly, S. Tropical Cyclones and the Mobility of Older Persons: Insights from Coastal Bangladesh. In Climate-Related Human Mobility in Asia and the Pacific; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse, L. Working with Russian-Jewish Immigrants in End-of-Life Care Settings. J. Soc. Work. End-Life Palliat. Care 2013, 9, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pakulski, L.A. Addressing Hearing Loss of Palestinians Living in Refugee Camps. Perspect. ASHA Spec. Interest Groups 2024, 9, 1188–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappadis, M.R.; Sander, A.M.; Struchen, M.A.; Kurtz, D.M. Soydiferente: A qualitative study on the perceptions of recovery following traumatic brain injury among Spanish- speaking U.S. immigrants. Disabil. Rehabil. 2022, 44, 2400–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajesh, M. Getting Old in Little Lhasa: Experiences of Aging in Dharamsala. In Handbook of Research on Multicultural Perspectives on Gender and Aging; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Saadi, A.; Hampton, K.; de Assis, M.V.; Mishori, R.; Habbach, H.; Haar, R.J. Associations between memory loss and trauma in US asylum seekers: A retrospective review of medico-legal affidavits. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, D. A place to grow older … alone? Living and ageing as a single older lifestyle migrant in the Azores. Area (London 1969) 2018, 50, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Tran, D.; Bach, A.; Ngo, U.; Tran, T.; Do, T.; Meyer, O.L. Impact of War and Resettlement on Vietnamese Families Facing Dementia: A Qualitative Study. Clin. Gerontol. 2022, 45, 798–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhou, J.; Druta, O.; Li, X. Settlement in Nanjing among Chinese rural migrant families: The role of changing and persistent family norms. Urban Stud. 2023, 60, 1083–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang, C. Loneliness Experiences of Hmong Older Adults: A Constructivist Grounded Theory Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ, USA, ASU Electronis Theses and Dissertations. 2019. Available online: https://keep.lib.asu.edu/items/157586 (accessed on 12 July 2025).

- Wijekoon, S. We Were Meant to Go Down One Road, but Now We Have Rerouted: A Phenomenological Inquiry into the Experience of Aging Out-Of-Place. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Western Ontario, London, ON, Canada, 2018. Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository, Publication No. 5569. Available online: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5569 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Winterton, R.; Warburton, J. Ageing in the bush: The role of rural places in maintaining identity for long term rural residents and retirement migrants in north-east Victoria, Australia. J. Rural. Stud. 2012, 28, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]