Abstract

Inactivity during pregnancy and postpartum is largely a result of women’s attitudes and misunderstandings of physical activity, especially in Iran. This scoping review critically assesses the barriers and facilitators influencing physical activity among pregnant and postpartum Iranian women to provide the basis for future physical activity interventions. Ten databases and platforms were searched up to 1 June 2024: Medline, SportDISCUS, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Review Database, Clinical Trial, SID, ISC, and Web of Science. Grey literature sources were included to retrieve original publications on barriers and facilitators during pregnancy and postpartum among Iranian women. The search resulted in 2470 identified studies screened for inclusion criteria. After screening both abstracts and full texts, 33 of the studies were included, and data were extracted and charted. Findings were summarized in alignment with the objectives. The results show that the basic physical activity barriers are intrapersonal, interpersonal, and environmental factors. Facilitating factors include using E-learning resources and combined interventions to educate women and provide awareness of the existence of exercise classes. Social and emotional support by family members and other women in the same situation can be effective. Overall, the study of obstacles to and enablers of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum is ongoing. In addition to highlighting the present situation in Iran, this study identifies further opportunities for future research on the development of appropriate interventions to reduce the barriers and strengthen the facilitators for physical activity among pregnant and postpartum Iranian women with trained groups, including skilled healthcare providers.

1. Introduction

Many guidelines recommend that regular physical activity (PA) has several health benefits for mothers and their children during pregnancy and postpartum [1,2,3]. However, women report declining PA levels as pregnancy progresses [4,5]. Several studies report evidence demonstrating that PA can prevent birth complications for mothers and infants [1,3,6]. For instance, PA during pregnancy decreases the risk of placenta previa, hypertension, gestational diabetes, and cesarean section [7]; improves maternal glucose levels [8]; supports healthy neonatal birth weight [6]; improves the quality of life (health, physical comfort, mental and social dimensions) [5]; develops the motor and social skills in infancy [9]; and leads to postpartum benefits [10,11]. Moreover, PA throughout gestation is associated with postpartum weight loss, higher scores on psychosocial health measures [6,11], improved sleep [1], and reduced postpartum depression [12]. Considering these outcomes and the beneficial effects of PA during pregnancy on birth outcomes [13,14], it is advantageous for every woman to engage in exercise; however, the rate of PA decreases during pregnancy and postpartum [1,4,5,6].

In a comprehensive study conducted in Iran, the patterns of PA domains, insufficient PA, the intensity of PA, and sedentary behavior at both the national and provincial levels were assessed in 2021. The findings revealed that 49.42% of males and 51.95% of females had an age-standardized prevalence of a sedentary lifestyle in daily life [15]. Moreover, it was reported that active women tended to reduce their PA levels during pregnancy, and this pattern could persist into the postpartum period [16]. Abedzadeh et al. stated that only 22% of pregnant women were aware of the benefits of exercise during pregnancy [17]. The study by Esmailzadeh et al. showed that 70% of pregnant women did not participate in any PA [4], and Bahadoran et al. reported that 98% of individuals engaged in light-intensity PA, while less than 2% participated in moderate-intensity PA [5]. In a study in Tehran, 52% of the pregnant women in the first trimester did not participate in any exercise, 44% of this population participated in low-intensity, and 3.6% did moderate-intensity PA. In the second trimester, 70% of women did not engage in PA, while only 28.9% performed low-intensity and 0.4% achieved moderate-intensity PA. Also, within three months after delivery, 79.6% of postpartum women did not achieve the PA guidelines. Among 21.4% of active women, 18.2% performed low-intensity and 2.2% participated in moderate-intensity PA [4]. From the limited research available, several reasons have been reported to affect an individual’s ability to meet exercise recommendations [18]. Although the literature reports some barriers to participating in PA for women during pregnancy and postpartum around the world [16,18,19], there are also special factors that affect the PA level among Iranian women. These factors include intrapersonal struggles [20,21,22], interpersonal constraints [23,24,25], and environmental opportunities [20,26].

The focus of this study on Iranian women is particularly relevant given the cultural and social norms that influence health behaviors, including physical activity, in Iran [4,5,17]. These unique barriers, such as cultural restrictions on physical activity [27] and limited access to resources [23], necessitate targeted interventions. Furthermore, Iran is experiencing rising rates of pregnancy-related health issues, such as gestational diabetes and hypertension [28], making it crucial to address PA during these periods to prevent long-term health consequences. Additionally, aligning with national health goals to reduce maternal health disparities [29], this study aims to fill the gap in the literature by identifying the barriers and facilitators of PA, supporting efforts to maintain or increase PA levels, and using the findings to guide future exercise interventions for pregnant and postpartum women.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review was conducted based on the protocol by Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (2010) in five stages [30]. The review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).

2.1. First Stage: Aim and Research Questions

This scoping review aimed (1) to identify the barriers and facilitators of PA during pregnancy and postpartum among Iranian women, (2) to support maintaining or increasing PA levels in this population, as well as (3) to use the study outcomes to develop future exercise interventions during pregnancy and postpartum.

2.2. Second Step: Relevant Studies Identified

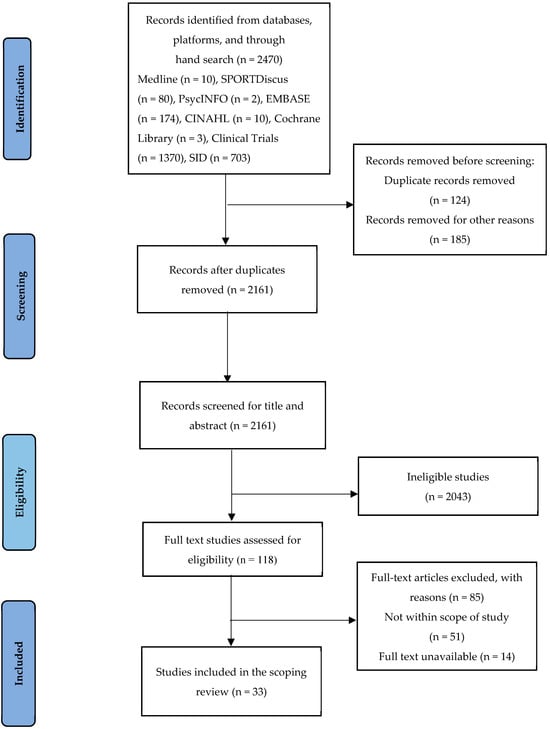

All qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies as well as systematic and non-systematic reviews published in English or Persian were eligible. Gray literature was also searched. The search included information up to June 2024. Ten electronic databases were consulted, including Medline (n = 10), SPORTDiscus (n = 80), PsycINFO (n = 2), EMBASE (n = 174), CINAHL (n = 10), Cochrane Library (n = 3), Clinical Trials (n = 1370), SID (n = 703), ISC (n = 113), and Web of Science (n = 5). The following keywords and MeSH terms were used in the searches: “physical activity, exercise, facilitators, barriers, pregnancy and postpartum, Iranian women”. Databases were searched for titles, abstracts, and keywords containing the terms “women”, “facilitator”, and “barrier”, as recommended for effective search criteria in scoping reviews [31]. A comprehensive search strategy was developed combining the following keywords: [(barriers OR constraints), (facilitator OR enabler), (physical activity OR exercise OR motor activity), (pregnancy OR pregnant women OR antenatal OR prenatal) AND (postpartum period OR postnatal)]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Table 1) were applied during the selection process for eligibility. A full electronic search strategy can be found in Table 2 and Table 3 and Supplementary Materials.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion search criteria for electronic database search.

Table 2.

Main characteristics of studies.

Table 3.

Themes, sub-themes, and categories and sub-categories of barriers and facilitators of PA during pregnancy and postpartum.

2.3. Third Step: Study Selection

After entering the searched articles into the Mendeley software (version 1.19.8) and removing duplicates, the screening process was performed by examining the title and abstract of the articles. Then, the full texts were examined by authors separately based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. If there was a difference of opinion, then it was resolved through discussion and exchange of viewpoints. All studies adhering to the inclusion criteria were first screened according to the titles, then the abstracts and full texts were reviewed for the included articles. The study selection process and reason for exclusion are presented in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection PRISMA flowchart.

2.4. Fourth Step: Charting the Data

A data extraction template was constructed using Microsoft Excel to extract the “barriers and facilities of PA” information stated within each included study (see Supplementary Materials). The following information was extracted in addition to the barriers and facilitators, number of participants, region, population characteristics, concept, and context of the study.

2.5. Fifth Step: Collating, Summarizing, and Reporting Results

The data extracted from the publications were collated and summarized based on the study design, participant characteristics, physical activity features, and findings reported. The summary provided insights into the nature and distribution of the included studies. To identify themes, a thematic analysis was conducted on the extracted data, focusing specifically on barriers to and facilitators of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum. The key findings from each study were reviewed and categorized into sub-themes related to each of the two main themes (barriers and facilitators).

Researchers independently reviewed each study, and their findings were discussed in consensus meetings to ensure accuracy and consistency in identifying the themes. This iterative process allowed for the refinement and grouping of the data into overarching themes that addressed the research questions of the review. As part of this process, the key findings from Table 2 were grouped into categories that reflected the central factors influencing physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum. These categories were further distilled into themes that directly addressed the barriers and facilitators identified across the studies. The sub-themes were further refined to create categories and sub-categories.

To enhance transparency and clarity, we quantified the prevalence of each theme. For example, 51% of the studies (n = 17) identified lack of knowledge about exercise programs as a major barrier to physical activity during pregnancy, while 49% of the studies (n = 16) reported social and emotional support as a facilitator. Other barriers, such as cultural restrictions, and facilitators, such as healthcare provider support, were similarly categorized and quantified based on their frequency across studies.

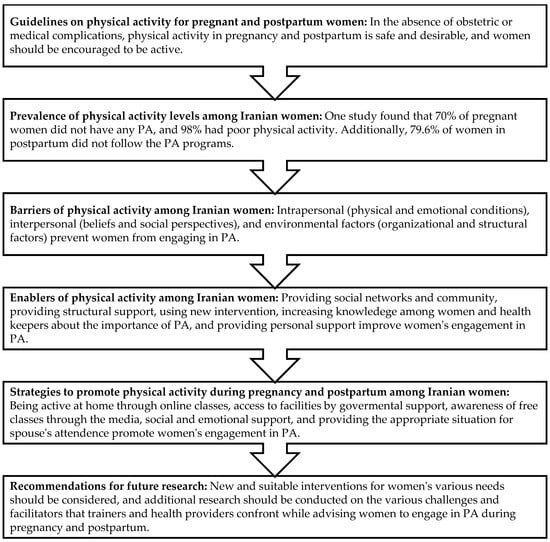

The themes presented in Table 3 and Figure 2 were derived from this analysis and represent the central factors influencing physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum among Iranian women. Figure 2 provides a visual summary of these key themes and sub-themes, directly informed by the thematic analysis process described above. This figure categorizes the factors under six main headings: guidelines on physical activity, prevalence of activity levels, barriers to activity, enablers of activity, strategies to promote activity, and recommendations for future research. Each of these headings encompasses specific sub-themes, highlighting the factors that play a crucial role in shaping physical activity behaviors during pregnancy and postpartum.

Figure 2.

Infographic of the scoping review. This figure illustrates the main findings related to physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum in Iranian women. Guidelines for physical activity, prevalence levels, and the barriers and enablers to physical activity are shown, with specific recommendations for promoting physical activity. References such as Hajimiri et al. [11], Arefi et al. [36] and Dolatabadi et al. [48] highlight significant barriers, while other sources [19,29,32,51] discuss effective interventions for improving engagement in physical activity. Further, strategies to promote PA are discussed through social and structural supports [20,26,32,53].

Consultation

People other than the authors were not involved in this review’s design, reporting, or dissemination.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

A total of 2470 studies were identified for screening (pregnancy n = 1805, postpartum n = 563), with 33 studies included in the final analysis (see Table 2). The studies included a variety of designs, including descriptive methods, randomized clinical trials, and qualitative research. Figure 1 presents a study selection flowchart, with a summary of included studies detailed in the Supplementary Materials. Also, the narrative summary of findings is organized according to our research questions (Table 2). Two major themes followed by seven subthemes, 16 categories, and 40 subcategories were developed in this study (Table 3).

We included 24 studies with a total of 4217 pregnant women [17,20,23,24,26,27,29,32,33,35,36,37,39,41,42,43,44,46,48,49,50,52,54,55], 54 care providers [26,37,51], and 1890 postpartum women [4,11,21,22,25,34,40,45,47] ages 18 to 45 years old. Most pregnant women were recruited between the second and third trimesters [20,24,26,27,32,33,35,43,44,50]. Meanwhile, six papers were started in the first trimester [29,38,39,42,46,48].

Some inclusion criteria for pregnant women were as follows: Iranian women with a healthy or low-risk pregnancy, nulliparous or second pregnancy, and singleton [17,23,26,27,32,41,42,44,46,48,52]. The inclusion criteria for postpartum women included being healthy and primiparous [4,11,22,34,40,45,47]. All women had no restriction on PA. In five papers, the study participants had a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 [26,40,43,46,47,52], and one study had participants with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) [37]. All postpartum women participated between 6 months and 1 year after delivery [4,11,21,22,25,34,40,45].

Regarding the barriers and facilitators of PA during pregnancy and postpartum, datasets were derived from in-depth interviews [25,26,33,36,37,38], questionnaires [4,11,17,20,21,22,24,25,26,27,29,32,33,34,36,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,48,50,51,52,55], open-ended questions [23,26,43,44], and semi-structured interviews [32,37,47,49].

The quality of the studies included in this review was assessed based on the clarity of the research design, sampling methods, data collection and reporting procedures, and the validity and reliability of the measure instruments used. While many studies included validated questionnaires [11,20,22,23,43,48], some did not provide detailed information about the psychometric properties of the tools used [17,25,42,52]. Additionally, a variety of study designs were employed, including randomized controlled trial [29,34,35], cross-sectional studies [17,46,48], quasi-experimental designs [20,42,43], and qualitative research [25,26,40]. Despite this variation, all studies attempted to address the key factors affecting physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum. However, the heterogeneity of these studies in terms of design, measurement tools, and reporting practices may limit the ability to directly compare findings.

Several limitations of the retrieved studies should be acknowledged. Common limitations in the retrieved studies included small sample sizes [17,21,26,33,39,41,47], which limited the generalizability of findings. Moreover, several studies were conducted in specific geographic regions, such as urban centers, which limited the applicability of the findings to broader populations, including those in rural areas or from different racial or ethnic backgrounds [17,22,23,33,39,41,43,46]. Furthermore, many studies relied on self-reported data [11,21,27,39,41,51], which may introduce recall bias or inaccuracies in the reporting of physical activity levels. Another limitation was that some studies did not consider the attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors of husbands and healthcare providers (e.g., physicians and midwives), which could have provided valuable insights into the reasons for physical inactivity among pregnant and postpartum women [21,37,44,55]. This exclusion could have led to an incomplete understanding of the social and cultural factors influencing physical activity levels among pregnant and postpartum women. These factors, if considered, may have provided valuable insights into why some women engage in physical activity while others do not.

3.2. What Barriers Affect the Physical Activity Level in Pregnancy and Postpartum?

In this study, eight papers (28%) reported the barriers [11,24,25,32,38,47,48,51], 13 studies (39%) showed facilitators [20,22,26,29,33,34,35,36,39,40,43,49,50,55], and 12 papers (37%) mentioned both facilitators and barriers [4,17,21,26,27,37,41,42,44,45,46,52]. Generally, women reported numerous barriers to PA. Three themes were identified from the content of PA barriers: intrapersonal factors [32,46], interpersonal factors [27,37], and the environment [47,51]. More details are discussed in the following text.

3.2.1. Intrapersonal Factors

Intrapersonal factors (derived from individuals) were dichotomized into health-related and non-health-related categories [56]. Examples of health-related barriers included physical limitations [48,52], health conditions [4,32,46], tiredness, dizziness, and fatigue [26,32,47,48]. Non-health-related barriers were related to psychosocial attitudes toward PA, a specific lack of motivation [19,26], or a lack of self-efficacy [11,22,36,39,41,45].

Despite participants usually being aware of the current guidelines for PA for non-pregnant adults, they were not aware of separate guidelines for PA during pregnancy [16] or postpartum [19]. In 17 studies, a lack of knowledge regarding exercise classes and educational programs for pregnant women in hospitals, health centers, or sports facilities was reported to affect the rate of PA participation [17,21,23,24,25,26,29,32,37,39,40,41,42,43,44,48,52]. Additionally, these studies stated that these opportunities for pregnant women are limited in developing countries [24,26,37]. Two studies indicated motivation as an important factor for exercising during pregnancy and postpartum [26,44]. In an in-depth interview, a few women who felt at risk of pregnancy-induced complications tried prenatal exercise classes, for example, women with a history of familial diseases or high blood pressure [26]. Physiological and physical conditions and heaviness were noted in nine papers [4,21,23,26,32,44,46,48,52]. For instance, the morphological changes experienced during pregnancy were an important reason for limiting PA. As pregnancy progresses, the growing abdomen makes it difficult to carry out certain activities, such as running. Consequently, pregnant women often feel that they should reduce the amount and type of exercise during the advanced stages of pregnancy [4,5]. Another key barrier is physiological changes. Shortness of breath and fatigue are important obstacles among postpartum women that prevent them from being active [4,16,32,47]. A survey in Tehran indicated that 68% of pregnant, and 49.9% of postpartum women felt fatigue [4].

Five papers directly mentioned that pre-pregnancy or early pregnancy body mass index (BMI), and exercise habits before pregnancy had a significant relationship with the total PA intensity [21,22,39,46,48]. Specifically, women with a BMI above 30 kg/m2 before or at the beginning of pregnancy had a higher mean energy expenditure and intensity [46,48]. Additionally, gestational age had a significant correlation with energy expenditure. Two studies found that engagement in PA levels is higher during the first trimester of pregnancy compared to the second and third trimesters [39,46].

3.2.2. Interpersonal Factors

The interpersonal factors (elements that affect how people interact with each other) are included in social interaction [25,36,42,44,46], social support [19,20,22,25,36,41,44,46,47], and cultural and religious beliefs prevailing within the society [27,32,36,37]. While normative beliefs or subjective norms are derived from an intrapersonal level, for this review, they were examined at the interpersonal level, as they describe persons identified as valuable for informational and motivational support for PA during pregnancy.

In 17 papers, the role of social support was mentioned [5,20,21,23,26,27,32,36,37,40,42,44,46,47,48,52,55]. Pregnancy is a critical period for family members, and the role of spouses is considerable. These studies in Iran examined the barriers and facilitators of Iranian men’s involvement in perinatal care. The findings showed that gender authoritarian attitudes (including subjective norms, stereotypes, and hidden fears), constraints (including individual, organizational, socio-economic, and legislative constraints), and incentives (including individual, family, economic, legislative, and organizational incentives) are the main factors that men face which affect maternal and neonatal health promotion programs [53,57,58]. For example, it was noted that some husbands did not permit their wives to engage in PA because they believed it to be dangerous for their babies [5,26].

Additionally, family discouragement was perceived as a great barrier to PA [32,46]. In some Iranian regions, it is still common for couples to live with the husband’s family. Therefore, the effects of family attitudes and behaviors, especially during pregnancy, are more pronounced. Pregnant women mentioned that the bustling atmosphere of the family and a lack of understanding of their conditions led to increased stress [32,37]. Through in-depth interviews with pregnant women, it was revealed that, despite their belief that the presence of other women in pregnancy classes can motivate them to attend [44], many sociocultural norms prevented them from offering mutual support [26,32]. In seven studies, a lack of communication (role of healthcare and physicians, other pregnant people) was discussed [4,26,32,37,44,47]. The results of a questionnaire completed by postpartum women indicated that physicians (91.6%) and midwives (84.4%) had a significant influence on physical activity (PA) participation. However, studies showed that only 62% of women consulted with a physician. Furthermore, health centers play an effective role in the postpartum period, with physicians (88.9%) and midwives (82.2%) significantly influencing PA participation [4].

The roles of pregnant and postpartum women as child caregivers, along with domestic responsibilities, lead to a lack of time and energy to exercise regularly [24,38]. Ahmadi et al. (2021) found that the number of children in the household negatively impacts mothers’ PA. Women with a higher number of children expended more energy by carrying out light and moderate household/caregiving responsibilities. In contrast, childless pregnant women had a higher energy expenditure for carrying out occupational, sports, and vigorous activities [46]. However, a study in Southeast Asia found that the number of children in the household did not impact maternal PA levels. Indonesian mothers who had one child did not differ in PA levels and sitting times compared to mothers who had more than one child in their household [19].

In 15 studies, cultural and social beliefs and attitudes were revealed [4,17,21,24,26,32,33,36,37,40,43,44,46,48,52]. Bahadoran et al. (2015) claimed that differences in cultural, social, and religious beliefs can be effective in increasing the amount and the mode of PA [5]. Structural problems, such as husband’s opposition and the affordability of classes, affected their ability to attend classes and be more physically active [19,26,27,37,48,53]. In developing countries, culture is affected by religion and beliefs [26]. Although the Islamic religion emphasizes the importance of PA and demands an active lifestyle, it is difficult for women to be physically active in this strict culture. One aspect of the Islamic faith is the expectation for modest dress, including clothing that covers most of the body [18,46]. It was reported that dress and negative perceptions toward Arab Muslim women who are involved in sports or exercise are the main barriers to participation in PA. Among the participants, 36.3% strongly agreed that the lack of female facilities was a barrier to being active. Additionally, most women felt stressed (76.1%), embarrassed to exercise in public (59.8%), and uncomfortable wearing gym clothes (82.7%). The majority of women had high levels of religious affiliation and reported that their religious faith influenced their choices, personality, and behavior [18].

3.2.3. Environmental Factors

There are a variety of environmental factors and socioeconomic restrictions. These are composed of two categories: physical factors (lack of health and safety principles in sports environments, long distance to PA facilities) and organizational and structural factors associated with sports environments (costs, facilities, equipment, and location) [32,34,47,48].

In nine studies, a lack of equipment and sports facilities were mentioned [23,26,32,40,44,46,47,48,51]. Ahmadi et al. (2021) stated that the location affects the participation rate in PA. Although all participants in the study lived in the city, it is noted that PA promotion may need tailoring to address the needs of women living in both rural and urban settings, particularly since women in urban areas generally have greater access to sports facilities (such as clubs) than women in rural areas [46]. However, urban areas are often not suitable for walking or other activities due to air pollution and crowded, built-up environments [46,48]. In a study examining the relationship between intensity, barriers, and correlates of PA among Iranian pregnant women in their second trimester, the findings revealed that women who did not attend childbirth preparation classes expended more energy (MET-hour/week). Contrary to expectations, these classes in Iran do not provide training on the importance and safety of PA during pregnancy [46]. In a study conducted on midwifery personnel at health centers in Isfahan city, it was found that all research units exhibited poor performance (100%), and most individuals had only average awareness (50%) regarding exercise training during pregnancy [51]. Therefore, there are significant opportunities to integrate PA promotion into childbirth preparation classes.

Several studies on pregnant women noted that homes are small and not suitable for PA. Some pregnant women believed that completing chores like washing and cleaning was adequate exercise [26,48]. The economic situation and financial problems were other barriers to participation in PA classes in six studies [23,26,27,36,44,46]. Some participants stated that they preferred to participate in a sports class that was not expensive and that had a private trainer. Furthermore, most pregnant women were unaware of free programs [35,46]. According to the study by Ahmadi, a higher income was also associated with increased energy expenditure, and lower income levels have similarly been associated with decreased PA; the researchers suggested that those with lower incomes should be targeted in the future promotion of PA [46]. It seems that there is a relationship between income, job, and rate of PA. Pregnant and postpartum women spend a significantly greater amount of time sitting compared to being physically active. The time spent sitting might be related to their employment status. Increased technology has led to changes in employees’ lifestyles, with prolonged desk-based work and reduced activity [19].

3.3. What Facilitators Affect the Physical Activity Level in Pregnancy and Postpartum?

A survey in Iran showed that exercise during pregnancy and postpartum elicited a sense of happiness and enjoyment among women (94.7% and 94.2%, respectively) [4]. Therefore, it seems that some factors could help women to improve their PA. The findings of Kianfard’s research (2021) indicated that maternal health is not the primary motivation for implementing exercise programs during pregnancy [26]. Related to this issue, providing a bonus for exercising (e.g., earning points toward gifts) might help motivate pregnant women to exercise regularly [19]. Some women claimed that they did not have enough money or time to attend exercise classes. Employing a variety of strategies, including having mobility at home [26,32,35], access to facilities [16,48], and awareness of free classes [23,37], were identified as essential motivators for PA.

Social and emotional support from husbands or partners, family, and friends is necessary [5,20,21,23,26,27,32,36,37,40,42,44,46,48,52,55]. In five papers, the role of family members was mentioned as a facilitator [21,23,32,36,55]. For example, some women’s husbands gave general encouragement, whereas others accompanied women while walking or exercising in gymnasiums or parks [21,23]. Social networks and the community [16,23,32] played an important role in making regular exercise possible. Women described neighborhoods where they felt free to walk, even at night, and where there were places for children to play [59].

Educational methods and interventions were suggested by 12 papers [20,25,26,29,32,33,34,37,42,45,49,50]. Combined exercise intervention methods, such as face-to-face plus monitored home programs, have a lower cost and could improve PA levels [35]. Women also said that providing guidance or education about how to safely do exercises during pregnancy and postpartum through different methods (including face-to-face, phone, and SMS counseling and a booklet) would make it easier for them to be physically active [22,24,25,34,50,59]. This means that healthcare providers must provide all information about the existence of these classes to pregnant women, and social networks and media must inform them as well [5,17,26,27,37,48,52]. Many studies stated that online training and E-learning applications could increase antenatal and postnatal PA [20,26,34,49,60]. E-learning was described as having a significant effect on training factors (the role of people who communicate with pregnant women), enabling factors (including appropriate places) [23], perceptual factors (awareness of type, intensity, frequency of exercise, reasons for doing exercises), and attitude (social and individual attitude) [43] that increase PA among women.

In a study by Ahmadi, a mobile application (app) was developed to promote PA among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. The app was designed based on a needs assessment with pregnant women, childbirth preparation teachers, and health experts, ensuring the content met their specific needs. The app included multimedia elements (text, photos, videos, GIFs) and covered 12 domains, such as the benefits of PA, safe exercises (e.g., walking, yoga), daily activities, posture, and relaxation exercises. It also addressed perceived barriers, social support, and enjoyment. The app was provided to the intervention group with training on usage and weekly reminders through a national messaging platform. Data from pre- and post-intervention questionnaires showed significant improvements in perceived benefits, enjoyment, and overall PA levels in the intervention group compared to the control group. The study demonstrated that mobile apps can effectively promote PA among pregnant women, especially when access to in-person classes is limited, and suggested integrating such apps with face-to-face sessions in health centers for better results [20]. Another study employed a mixed-methods design (both quantitative and qualitative) to investigate the impact of an E-learning intervention on PA levels among pregnant women. The first phase involved a comprehensive literature review followed by semi-organized interviews with pregnant women. This stage utilized qualitative methods to capture the perspectives and experiences of the participants, providing a deep understanding of the barriers to and facilitators of PA during pregnancy [26].

The second stage involved the implementation of an E-learning program intervention based on the insights obtained from the first stage. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) design was employed, with a pre-test/post-test structure and a control group. The results highlighted the potential of E-learning interventions as an effective tool for promoting health behaviors, such as physical activity, in pregnant women, especially in contexts where cultural norms or access to traditional health education are limited [26].

3.4. The Role of Men as a Barrier or Facilitator

Although the role of social support (i.e., family members, friends, and other pregnant women) has been mentioned, the importance of the spouse’s attendance during these periods is crucial. In Iranian culture, men view themselves as more involved in significant life decisions (paternal role) and often perceive helping a spouse as a sign of weakness and a diminishment of their status [32,47,58]. The existence of gender roles in society and the traditional patriarchal culture dominant in Iranian families affect both the supportive role of their wives and contribute to negative attitudes toward men’s participation in pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum care. Participants mentioned that men’s fear of social stigma associated with participating in pregnancy and delivery care is a barrier to their involvement during this period [53,58].

Women’s preference to maintain their privacy was another reason for the limited role of men. Additionally, educational poverty affects the knowledge of men and families in prenatal care. Lack of awareness, men’s inadequate experiences, communication problems, structural problems in health centers, issues related to human resources, policymaking and managerial problems, socioeconomic barriers, and men’s occupational problems are other barriers to the role of men in supporting their wives’ pregnancy and exercise [27,53,57,58]. The results of a study demonstrated that the emotional attention and presence of men were important for their wives [21], but some were deprived of this attention and were only accompanied to clinics [32,37].

In contrast to these findings, some women commented on the benefits of PA with their partners, which helped strengthen the relationships and bonds between them [21,23]. A study assessed the effect of teaching an educational package to spouses using two methods—in-person and distance education—in childbirth preparation classes on women’s mental health [55]. The results of this study showed that the distance education method led to a decrease in physical symptoms, anxiety and insomnia, social dysfunction, and depression [55]. A majority of men preferred to receive training in pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum care face to face, with the presence of their wives in the morning or on holidays at health centers preferably by a female doctor. In all public and private centers in Iran, maternity and postnatal services are provided by women (midwives, nurses, health personnel, and gynecologists). The results of a study by Nasiri et al. indicated that 30% of men agreed with the content of exercise during pregnancy and after childbirth [58]. Moreover, it seems that reducing the costs of pregnancy and delivery care and para-clinical measures during pregnancy, financial support from the government for expecting families, and effective implementation of the leave law would provide more relief for men and create opportunities for their participation in perinatal care [53].

3.5. What Strategies Increase Physical Activity Levels in Pregnancy and Postpartum?

In the following table, the strategies identified in the studies are listed (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Evidence from Iranian studies and strategies for promoting physical activity.

4. Discussion

The gestational and postpartum periods provide opportunities to promote maternal health behaviors and enhance quality of life. Exercise is recognized as a positive health behavior with multidimensional benefits [4,40]. Despite guidelines recommending that women without contraindications engage in PA [1,2], fewer than 19% of women meet recommended levels of PA during their pregnancy [17] and postpartum [4]. Pregnancy and the postpartum period can affect the amount of PA women engage in due to various barriers that make maintaining adequate PA challenging. Therefore, it is crucial to explore and identify these barriers within this population [11,18,38]. In this review article, the authors addressed several questions, including the current state of PA and the identification of barriers and enablers of PA among the Iranian population. We present the following key points from the scoping review.

First, our review indicates that various factors, including cultural expectations, traditional beliefs, ethnicities [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,38], personal circumstances [34,43], and societal pressures limit women’s participation in PA during pregnancy and postpartum. The finding that many pregnant women prefer to exercise indoors due to the wearing of the hijab highlights the need for more accessible indoor exercise options [46]. Additionally, the economic and environmental barriers to PA [32,47], such as the high cost of exercise classes [32,35] and inadequate facilities [40,47], must be addressed to promote physical activity among these women. Postpartum women also face the challenge of balancing PA with childcare responsibilities [11,21], leading to reduced time for exercise. The impact of low income and higher numbers of pregnancies on PA participation suggests that targeted interventions for women with a lower socioeconomic status or those in later pregnancies may be particularly beneficial [46]. Moreover, societal pressure on women to prioritize family duties, along with the perception that pregnancy is a high-risk period, further compounds these barriers, highlighting the importance of social support in overcoming these obstacles [5,27,47].

Second, the limited involvement of spouses in promoting physical activity is a significant barrier in Iranian communities, where cultural norms reinforce traditional gender roles and care [27,37,53,55]. In these communities, men’s participation in perinatal care is often hindered by societal expectations, where women are primarily responsible for household and childcare duties, and men are expected to provide financially. Furthermore, senior women, such as mothers-in-law, hold substantial influence over caregiving, further restricting men’s participation in PA promotion [53]. Although there is some evidence of increased male involvement in perinatal care, this change is not yet widespread, and many barriers still exist. Given the central role of spouses in women’s health and well-being, further research is necessary to explore how male support can be better integrated into physical activity promotion and what strategies could help overcome these cultural constraints.

Third, the effectiveness of virtual training in promoting physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum is supported by emerging evidence, particularly through E-learning initiatives. These programs not only provide flexibility but also have the potential to improve mental health outcomes, demonstrating their utility as a cost-effective solution to increase engagement in PA [20,23,53,55]. The findings underscore the importance of making physical activity more accessible through virtual platforms, which can reach a broader population, particularly in areas where physical space and financial resources are limited [32]. Furthermore, enhancing the availability of sports facilities and offering free or subsidized exercise programs can eliminate some of the barriers to participation [26,44]. Some studies highlighted that E-learning [26] and mobile app [20] interventions are highly effective at increasing physical activity levels among pregnant women, particularly when in-person classes are not feasible due to constraints such as the COVID-19 pandemic [20]. These findings emphasize the significant role of technology in supporting health behaviors and overcoming the practical limitations faced by pregnant and postpartum women.

Fourth, the findings suggest that healthcare providers have a significant influence on physical activity levels during pregnancy and postpartum [4,27,44,49]. This influence is particularly important given the challenge of limited awareness among women about available exercise opportunities. Physicians, midwives, and other healthcare providers are in a unique position to inform and educate women on the benefits of physical activity and to guide them toward safe, accessible, and effective exercise programs [44,47]. Given that many women rely on healthcare professionals for advice during this critical period, their proactive involvement in promoting PA could help overcome one of the major barriers identified in this review stage.

Finally, to effectively reduce physical inactivity, it is essential to diversify the facilitators of physical activity, recognizing that some factors such as individuals (e.g., healthcare providers and experts [51]) and situations (i.e., during and after global pandemics [20,47]) have indirect effects on PA levels. The findings suggest that several promotional strategies can be effective in educating pregnant and postpartum women. These strategies include face-to-face training, mobile applications, broadcasts, SMS communications, local newspapers, billboards, and structured exercise programs [20,25,26,29,32,33,34,37,42,45,49]. Additionally, utilizing social support from neighbors, family, and friends can enhance the impact of these educational efforts [20,25,36,41,44,61]. Societies must amplify efforts to reduce physical inactivity by educating and training professional workforces. A diverse and well-trained group of professionals represents a promising opportunity to improve PA levels.

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this scoping review lies in its comprehensive search, which identified 33 publications encompassing both qualitative and quantitative research across a range of racial, cultural, and educational backgrounds, as well as distinct health needs. By synthesizing findings from diverse studies, this review provides in-depth insights from women’s narratives, which can guide the development of strategies to enhance PA and healthcare during pregnancy and postpartum. However, there are limitations to consider. The studies included participants from only certain regions of Iran, meaning the results may not be representative of all Iranian women. Additionally, the review predominantly focused on women during pregnancy, with limited information on the postpartum period. Furthermore, many qualitative studies did not directly report relevant factors, potentially introducing bias.

4.2. Recommendation for Practice and Research

This review was designed to inform those involved in creating lifestyle interventions, guidelines, and care models for pregnant and postpartum women in Iran. The findings highlight several key criteria, barriers, facilitators, and essential components for designing effective interventions that cater to the unique needs of this population. To address the challenges that women face during pregnancy and postpartum, it is imperative to adopt a comprehensive approach that considers the contextual and socio-cultural factors that influence PA participation. Specifically, the challenges experienced by women may differ significantly between rural and urban settings, requiring interventions to be tailored accordingly. Women in urban areas often have better access to facilities, while those in rural settings may face more significant logistical and financial barriers. Therefore, it is essential to develop culturally appropriate interventions that are adaptable to local contexts. Educational programs and interventions should emphasize the importance of physical activity while incorporating local cultural beliefs and practices regarding health and exercise. Additionally, social support from family members, particularly husbands, as well as healthcare providers, plays a critical role in encouraging PA. Interventions should therefore aim to increase social support by involving both family members and healthcare providers in the promotion of PA, making it an integrated part of the routine care process.

Furthermore, this review identifies a notable gap in the training and support provided to healthcare providers and exercise instructors. These professionals play a pivotal role in facilitating PA among pregnant and postpartum women, yet they often face challenges in effectively promoting and supporting PA. To address this gap, it is recommended that training programs for healthcare providers, including physicians and midwives, be developed to enhance their ability to support women’s physical and mental health during pregnancy and postpartum. These programs should be evidence-based and culturally tailored to improve the effectiveness of healthcare providers’ recommendations. There is also a need for further research to examine the psychosocial factors that influence women’s engagement in PA during pregnancy and postpartum, particularly factors such as self-efficacy, knowledge, and social support. Research should focus on understanding how these factors vary across different populations, especially in rural versus urban areas, and how interventions can be tailored to address the specific barriers and facilitators that exist in these settings.

Finally, the limited literature on facilitators of PA during pregnancy and postpartum underscores the need for more targeted studies. Future research should explore the unique challenges and opportunities in rural and urban populations, considering cultural and regional differences. It should also investigate the role of family members, particularly husbands, in supporting PA during these periods. By addressing these gaps, future studies will contribute to a more nuanced understanding of how to design effective lifestyle interventions that meet the needs of Iranian women during pregnancy and postpartum. Ultimately, these recommendations aim to provide a clear framework for improving the design and implementation of interventions that encourage PA in this population, ensuring they are both effective and culturally appropriate.

5. Conclusions

Women during pregnancy and postpartum experience barriers to engaging in physical activities. The main PA barriers are captured by three themes: intrapersonal variables (physical and emotional dimensions), interpersonal factors (cultural poverty, social beliefs, and the role of family members), and the environment (organizational structures and economic situation). This review article discusses how pregnancy and the postpartum period provide an excellent opportunity to educate women about the benefits of PA and a healthy lifestyle. Raising women’s awareness of PA during pregnancy and postpartum, as well as changing their attitudes, may lead to behavioral adjustments. Meanwhile, the role of clinicians is very prominent. Healthcare providers encounter additional barriers while offering care to pregnant and postpartum women, such as skill limitations and a lack of communication between practical interventions and clinical concerns. Understanding the views of two key stakeholders—women and healthcare providers—is critical for developing effective interventions. This review highlights some facilitators and barriers that are crucial to the design and implementation of PA interventions for pregnant and postpartum Iranian women (see Figure 2).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/healthcare12232416/s1, Table S1: Detailed Overview of Reviewed Studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.A.S.; data curation: N.A.S.; formal analysis: N.A.S., A.S., S.J.M., L.E.M. and R.S.-R.; investigation: N.A.S., A.S., S.J.M., L.E.M. and R.S.-R.; methodology: N.A.S., A.S., S.J.M., L.E.M. and R.S.-R.; supervision: N.A.S.; roles/writing—original draft: N.A.S.; and writing—review and editing: N.A.S., A.S., S.J.M., L.E.M. and R.S.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partially financed by the Polish National Academic Exchange Agency (NAWA) within the SPINNAKER program—Intensive International Education Programs, as part of the project entitled “The New Era of Pre- and Postnatal Exercise—Training for Instructors and Trainers of Various Forms of Physical Activity in the Field of Online Provision of Exercise for Pregnant and Postpartum Women—The NEPPE Project” (No. PPI/SPI/2020/1/00082/DEC/02).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- ACOG. Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. 2020. Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2020/04/physical-activity-and-exercise-during-pregnancy-and-the-postpartum-period (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Mottola, M.F.; Davenport, M.H.; Ruchat, S.-M.; Davies, G.A.; Poitras, V.J.; Gray, C.E.; Garcia, A.J.; Barrowman, N.; Adamo, K.B.; Duggan, M.; et al. 2019 Canadian guideline for physical activity throughout pregnancy. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1339–1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szumilewicz, A.; Worska, A.; Santos-Rocha, R.; Oviedo-Caro, M.Á. Evidence-based and practice-oriented guidelines for exercising during pregnancy. In Exercise and Physical Activity During Pregnancy and Postpartum; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 177–217. [Google Scholar]

- Esmaelzadeh Saeyeh, S.; Taavoni, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Haghani, H. Trend of exercise before, During, and after Pregnancy. Iran. J. Nurs. 2008, 21, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadoran, P.; Mohamadirizi, S. Relationship between physical activity and quality of life in pregnant women. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2015, 20, 282–286. [Google Scholar]

- Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report; Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Saftlas, A.F.; Logsden-Sackett, N.; Wang, W.; Woolson, R.; Bracken, M.B. Work, leisure-time physical activity, and risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004, 160, 758–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Rocha, R.; Gutiérrez, I.C.; Szumilewicz, A.; Pajaujiene, S. Exercise testing and prescription for pregnant women. In Exercise and Sporting Activity During Pregnancy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 183–230. [Google Scholar]

- Shojaeian, N.A.; Shojaei, M.; Ghasemi, A.; Glascoe, F. Does Maternal Exercise Program During Pregnancy Affect Infants Development? A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Exerc. Health Sci. 2021, 1, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, W.J.; Hayman, M.; Haakstad, L.A.H.; Lamerton, T.; Mena, G.P.; Green, A.; Keating, S.E.; Gomes, G.A.; Coombes, J.S.; Mielke, G.I. Australian guidelines for physical activity in pregnancy and postpartum. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2022, 25, 511–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hajimiri, K.; Shakibazadeh, E.; Haeri Mehrizi, A.A.; Shab-Bidar, S.; Sadeghi, R. The role of perceived barrier in the postpartum women’s health promoting lifestyle: A partial mediator between self-efficacy and health promoting lifestyle. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2018, 7, 38. [Google Scholar]

- Szumilewicz, A.; Santos-Rocha, R.; Worska, A.; Piernicka, M.; Yu, H.; Pajaujiene, S.; Shojaeian, N.A.; Caro, M.A.O. How to HIIT while pregnant? The protocol characteristics and effects of high intensity interval training implemented during pregnancy—A systematic review. Balt. J. Health Phys. Act. 2022, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaeian, N.; Shojaei, M.; Ghasemi, A. The Effect of Physical Activity during Pregnancy on Development of Social Skills in Infants: A Short Report. J. Rafsanjan Univ. Med. Sci. 2017, 16, 381–388. [Google Scholar]

- Newton, E.R.; May, L. Adaptation of Maternal-Fetal Physiology to Exercise in Pregnancy: The Basis of Guidelines for Physical Activity in Pregnancy. Clin. Med. Insights Women’s Health 2017, 10, 1179562X17693224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejadghaderi, S.A.; Ahmadi, N.; Rashidi, M.-M.; Ghanbari, A.; Noori, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Nasserinejad, M.; Rezaei, N.; Yoosefi, M.; Fattahi, N.; et al. Physical activity pattern in Iran: Findings from STEPS 2021. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 1036219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian MK, P.; Van der Graaf, P.; Dawson, R.; Hayes, L.; Ells, L.J.; Sachdeva, K.; Azevedo, L. Barriers and Facilitators for Physical Activity in Already Active Pregnant and Postpartum Women? Findings from a Qualitative Study to Inform the Design of an Intervention for Active Women. Obstet. Gynecol. Res. 2022, 5, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedzadeh, M.; Taebi, M.; Sadat, Z.; Saberi, F. Knowledge and performance of pregnant women referring to Shabihkhani hospital on exercises during pregnancy and postpartum periods. J. Jahrom Univ. Med. Sci. 2011, 8, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eldoumi, H.; Gates, G. Physical Activity of Arab Muslim Mothers of Young Children Living in the United States: Barriers and Influences. Ethn. Dis. 2019, 29, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juwono, I.D. Barriers and Incentives to Physical Activity: Findings from Indonesian Pregnant and Postpartum Mothers. Physical Activity Review. Phys. Act. Rev. 2022, 10, 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani, N.; Pirzadeh, A. Mobile-application intervention on physical activity of pregnant women in Iran during the COVID-19 epidemic 2020. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2021, 10, 328. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garshasbi, A.; Moayed Mohseni, S.; Rafeiy, M.G.Z. Evaluation of women’s exercise and physical activity beliefs and behaviors during their pregnancy and postpartum based on the planned behavior theory. Daneshvar Med. 2020, 22, 7–16. [Google Scholar]

- Safarzade, S.; Behboodi Moghaddam, Z.; Saffari, M. The Impact of Education on Performing Postpartum Exercise Based on Health Belief Model. Med. J. Mashhad Univ. Med. Sci. 2014, 57, 776–784. [Google Scholar]

- Kianfard, L.; SHokravi, F.A.; Rakhshanderou, S.; Niknami, S. Investigating the Effect of Positive, Intermediate, and Negative Enabling and Training Factors Affecting Physical Activity in Pregnant Women. Res. Sq. 2021; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noohi, E.; Nazemzadeh, M.; Nakhei, N. The study of knowledge, attitude and practice of puerperal women about exercise during pregnancy. Iran. J. Nurs. 2010, 23, 64–72. [Google Scholar]

- Riyazi, H.; Bashirian, S.; Ghelich Khani, S. Kegel Exercise Application during Pregnancy and Postpartum in Women Visited at Hamadan Health Care Centers. Iran. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Infertil. 2006, 10, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kianfard, L.; Niknami, S.; Shokravi, F.; Rakhshanderou, S. Determine Facilitators, Barriers and Structural Factors of Physical Activity in Nulliparous Pregnant Women: A Qualitative Study Using Maxqda. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 10, 555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Fathnezhad-Kazemi, A.; Aslani, A.; Hajian, S. Association between Perceived Social Support and Health-Promoting Lifestyle in Pregnant Women: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Caring Sci. 2021, 10, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, S.; Khatibi, S.R.; Mahdizadeh, M.; Peyman, N.; Zare Dorniani, S. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes in Iran: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Med. J. Islam. Repub. Iran 2023, 37, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaderpanah, N.; Mohaddesi, H.; Vahabzadeh, D.; Khalkhali, H. The effect of 5A model on behavior change of physical activity in overweight pregnant women. Iran. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Infertil. 2017, 20, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtari, F.; Mokhtari, L.; Rezaei Adariani, A. Preparation of protocol for removing physical, psychological, environmental, and social barriers of physical activity in pregnant women. J. Birjand Univ. Med. Sci. 2019, 26, 259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Moridi, M. Examining Exercise Behavior Beliefs of Pregnant Women in Second and third trimester: Using Health Belief Model. Int. J. Musculoskelet. Pain Prev. 2016, 1, 69–74. [Google Scholar]

- Khodabandeh, F.; Mirghafourvand, M.; KamaliFard, M.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Ch, S.; Asghari Jafarabadi, M. Effect of educational package on lifestyle of primiparous mothers during postpartum period: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veisy, A.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Ch, S.; Abbas-Alizadeh, S.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Ghaderi, F.; Haghighi, M. Monitored home-based with or without face-to-face exercise for maternal mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Reprod. Infant Psychol. 2022, 42, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arefi, Z.; Sadeghi, R.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Yaseri, M.; Shahbazi Sighaldeh, S. Development and Psychometric Properties of the Physical Activity Scale for Pregnant Women. Health Educ. Health Promot. 2022, 10, 467–475. [Google Scholar]

- Kolivand, M.; Keramat, A.; Rahimi, M.; Motaghi, Z.; Shariati, M.; Emamian, M. Self-care Education Needs in Gestational Diabetes Tailored to the Iranian Culture: A Qualitative Content Analysis. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2018, 23, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Amiri-Farahani, L.; Ahmadi, K.; Hasanpoor-Azghady, S.B.; Pezaro, S. Development and psychometric testing of the ‘barriers to physical activity during pregnancy scale’ (BPAPS). BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akbari, Z.; Tol, A.; Shojaeizadeh, D.; Aazam, K.; Kia, F. Assessing of physical activity self-efficacy and knowledge about benefits and safety during pregnancy among women. Razi J. Med. Sci. 2016, 22, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ouji, Z.; Barati, M.; Bashirian, S. Application of BASNEF Model to Predict Postpartum Physical Activity in Mothers Visiting Health Centers in Kermanshah. J. Educ. Community Health 2014, 1, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Mousavi, A.; Shakibazadeh, E.; Sadeghi, R.; Tol, A.; Rahimi Foroushani, A.; Mohebbi, B. The effect of educational intervention on physical activity self-efficacy and knowledge about benefits and safety among pregnant women. Razi J. Med. Sci. 2020, 26, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Solhi, M.; Ahmadi, L.; Taghdisi, M.H.; Haghani, H. The Effect of Trans Theoretical Model (TTM) on Exercise Behavior in Pregnant Women Referred to Dehaghan Rural Health Center. Iran. J. Med. Educ. 2012, 11, 942–950. [Google Scholar]

- Kianfard, L.; SHokravi, F.A.; Rakhshanderou, S.; Niknami, S. Perceptual Factors (Awareness, Attitude) and Positive, Indeterminate and Negative Nurturing Factors Affecting Physical Activity of Pregnant Women Visiting Health-care Centers in Tehran: Examination and Analyses. Res. Sq. 2021; Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianfard, L.; Niknami, S.; SHokravi, F.A.; Rakhshanderou, S. Facilitators, Barriers, and Structural Determinants of Physical Activity in Nulliparous Pregnant Women: A Qualitative Study. J. Pregnancy 2022, 2022, 5543684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Peyman, N. The effect of education based on self-efficacy strategies in changing postpartum physical activity. Med. J. Mashhad Univ. Med. Sci. 2016, 59, 328–336. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi, K.; Amiri-Farahani, L.; Haghani, S.; Hasanpoor-Azghady, S.B.; Pezaro, S. Exploring the intensity, barriers, and correlates of physical activity In Iranian pregnant women: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2021, 7, e001020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidari Dehui, P.; Negarandeh, R.; Pashaeypoor, S. Weight Management Challenges in Nulliparous Women Being Overweight or Obese Due to Pregnancy: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Community Based Nurs. Midwifery 2023, 11, 190–200. [Google Scholar]

- Dolatabadi, Z.; Amiri-Farahani, L.; Ahmadi, K.; Pezaro, S. Barriers to physical activity in pregnant women living in Iran and its predictors: A cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouriayevali, B.; Ehteshami, A.; Kohan, S.; Saghaeiannejad Isfahani, S. Mothers’ views on mobile health in self-care for pregnancy: A step towards mobile application development. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2023, 12, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakeri, M.; Fekri, S.; Shahnavaz, A.; Shakibazadeh, E. Effectiveness of a Group-based Educational Program on Physical Activity among Pregnant Women. J. Hayat 2012, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Shayanmanesh, M.; Goli, S.; Soleymani, B. Survey of Midwives’ Practice and its Related Factors toward Exercise Instruction during Pregnancy in Health Centers of Isfahan in 2011. Iran. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Infertil. 2013, 15, 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani, F.; Maddadzadeh, N.; Heidarnia, B. Examining how to exercise and the effective factors on it based on perspective of pregnant women referring to health centers in Astara city. J. Health Breeze 2012, 1, 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Firouzan, V.; Noroozi, M.; Farajzadegan, Z.; Mirghafourvand, M. Barriers to men’s participation in perinatal care: A qualitative study in Iran. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019, 19, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdolalipour, S.; Mousavi, S.; Hadian, T.; Meedya, S.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S.; Mohammadi, E.; Mirghafourvand, M. Adolescent pregnant women’s perception of health practices: A qualitative study. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 6186–6196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmanian, F.; Seifi, F.; Tafazolim, M.; Tatari, M. Comparison of the Effect of Teaching an Educational Package to Spouses Using Two Methods of In-Person and Distance Education in Childbirth Preparation Classes on Pregnant Women’s Mental Health. J. Midwifery Reprod. Health 2021, 9, 2853–2862. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, E.L.; Vamos, C.A.; Daley, E.M. Physical activity during pregnancy and the role of theory in promoting positive behavior change: A systematic review. J. Sport Health Sci. 2017, 6, 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajian, S.; Mehran, N.; Simbar, M.; Alavi Majd, H. The Barriers and Facilitators of Iranian Men’s Involvement in Perinatal Care: A Qualitative Study. Reprod. Health 2020, 19, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, S.; Vaseghi, F.; Moravvaji, S.A.; Babaei, M. Men’s educational needs assessment in terms of their participation in prenatal, childbirth, and postnatal care. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kieffer, E.C.; Willis, S.K.; Arellano, N.; Guzman, R. Perspectives of pregnant and postpartum Latino women on diabetes, physical activity, and health. Health Educ. Behav. 2002, 29, 542–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiferman, J.; Gutilla, M.J.; Nicklas, J.M.; Paulson, J. Effect of Online Training on Antenatal Physical Activity Counseling. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 2016, 12, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabatabaei, S.V.A.; Ardabili, H.E.; Haghdoost, A.A.; Nakhaee, N.; Shams, M. Promoting physical activity in Iranian women: A qualitative study using social marketing. Electron. Physician 2017, 9, 5279–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).