Abstract

Patient satisfaction with hospital services has been increasingly discussed as an important indicator of healthcare quality. It has been demonstrated that improving patient satisfaction is associated with better compliance with treatment plans and a decrease in patient complaints regarding doctors’ and nurses’ misconduct. This scoping review’s objective is to investigate the pertinent literature on the experiences and satisfaction of patients with mental disorders receiving inpatient psychiatric care. Our goals are to highlight important ideas and explore the data that might serve as a guide to enhance the standard of treatment and patient satisfaction in acute mental health environments. This study is a scoping review that was designed in adherence with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement. A systematic search was conducted in the following databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and EMBASE. A comprehensive review was completed, including articles from January 2012 to June 2022. Qualitative and quantitative studies were included in this review based on our eligibility criteria, such as patient satisfaction as a primary outcome, adult psychiatric inpatients, and non-review studies published in the English language. Studies were considered ineligible if they included nonpsychiatric patients or patients with neurocognitive disorders, review studies, or study measure outcomes other than inpatient satisfaction. For the eligible studies, data extraction was conducted, information was summarized, and the findings were reported. A total of 31 studies representing almost all the world’s continents were eligible for inclusion in this scoping review. Different assessment tools and instruments were used in the included studies to measure the level of patients’ satisfaction. The majority of the studies either utilized a pre-existing or newly created inpatient satisfaction questionnaire that appeared to be reliable and of acceptable quality. This review has identified a variety of possible factors that affect patients’ satisfaction and can be used as a guide for service improvement. More than half of the included studies revealed that the following factors were strongly recommended to enhance inpatient satisfaction with care: a clear discharge plan, less coercive treatment during the hospital stay, more individualized, higher quality information and teaching about the mental disorder to patients by staff, better therapeutic relationships with staff, and specific treatment components that patients enjoy, such as physical exercise sessions and music therapy. Patients also value staff who spend more time with them. The scope of patient satisfaction with inpatient mental health services is a growing source of concern. Patient satisfaction is associated with better adherence to treatment regimens and fewer complaints against health care professionals. This scoping review has identified several patient satisfaction research gaps as well as important determinants of satisfaction and how to measure and utilize patient satisfaction as a guide for service quality improvement. It would be useful for future research and reviews to consider broadening their scope to include the satisfaction of psychiatric patients with innovative services, like peer support groups and other technologically based interventions like text for support. Future research also could benefit from utilizing additional technological tools, such as electronic questionnaires.

Keywords:

satisfaction; appreciation; contentment; experience; inpatient; mental health; hospital care 1. Introduction

Patient satisfaction began to receive scientific attention in the 1950s when it was realized that higher patient satisfaction was associated with better patient adherence to doctors’ prescriptions and medication consumption. It was also found to be associated with a decrease in patient complaints regarding professional misconduct []. The majority of the funds allocated for mental health services are often directed to staffing and beds in psychiatric hospitals in many different parts of the world; however, there is a significant disregard for the evaluation of both out- and inpatient mental health services as rated directly by patients []. Although focusing on the treatment gap, such as the lack of or insufficient quantity of services, is important in the mental health agenda, the quality of care from the perspective of people using it is crucial as well []. High satisfaction and high-quality care are frequently correlated. Positive experiences help patients achieve better results in terms of their mental health. People are more likely to actively participate in their treatment plans when they are happy with the care they receive, which enhances their general well-being. Furthermore, the stigma attached to obtaining and using mental health services can be lessened with positive experiences in mental health facilities. Positive interactions increase the likelihood that people will share their experiences, which can foster a more understanding and encouraging community []. Additionally, in any healthcare relationship, trust is essential. Patients’ satisfaction with inpatient mental health services contributes to increased trust in medical professionals and the health system. This trust is essential for ongoing collaboration between patients and healthcare providers [,,]. In this context, the increased marketing of healthcare services has prompted the creation of tools used for evaluating patient satisfaction as an indicator of healthcare quality and the efficiency of the healthcare system [,]. Although there is no agreed-upon definition of “patient satisfaction”, it is occasionally used as a subjective measure of whether a patient’s expectations for medical contact were met []. In other sources, it is described as a measurement of the degree to which a patient is happy with the care they receive from their doctor, a healthcare facility, or another healthcare professional []. The lack of a universally agreed-upon definition of patient satisfaction can be attributed to several factors such as subjectivity and cultural difference: which means patient satisfaction varies from person to person and is inherently subjective. It can be difficult to come up with a single, all-encompassing term that encompasses everyone’s viewpoints because different people may value different aspects of their healthcare experiences more than others. Also, the complexity of the healthcare process, where patients, healthcare providers, administrators, insurers, and other stakeholders are all involved in this complex and multifaceted system and priorities and expectations of each of these stakeholders could differ, could make it more difficult to come up with a standard definition. Additionally, healthcare evolution is very dynamic and ever-changing; hence, patient expectations and experiences may be impacted by new technologies, treatment options, and modifications to healthcare delivery models that may influence patient satisfaction as healthcare changes [,]. The relevance of reporting patient satisfaction as a component of studies assessing treatment outcomes has recently increased. There is no doubt that this crucial aspect of patient care must be accurately assessed, but the techniques and metrics required to do so have not yet been sufficiently established, and up to now, no conclusion could be drawn regarding factors leading to higher patient satisfaction. Several factors contribute to inpatient satisfaction, including the following: quality of care, where patients often evaluate the efficacy of medical interventions and the skill of healthcare professionals; communication is another factor, where clear and effective communication between healthcare providers and patients is crucial; accessibility, which is a patient’s level of satisfaction that is affected by how simple it is for them to obtain healthcare services, including, waiting periods, and the location of the facility; empathy and compassion, where patients value medical professionals who exhibit these qualities because they indicate that they are aware of and concerned about their well-being; dignity and respect: upholding patients’ dignity, honoring their cultural and personal preferences, and treating them with respect all contribute to their general satisfaction; and finally, facility and environment: the hospital physical layout, level of comfort, cleanliness, and general ambience can all affect how satisfied patients are [,,,]. There is no clear instruction on how to utilize any of the several satisfaction scales and metrics available to psychiatric inpatients for the assessment of inpatient satisfaction [,,]. It is difficult to provide a general overview of patients’ satisfaction with inpatient care because different instruments and methodological approaches were used in different studies to measure satisfaction []. There are various methods and tools for measuring patient satisfaction, including anonymous survey questionnaires, feedback forms, and interviews. Different healthcare organizations may use different instruments, making it challenging to standardize the measurement process and arrive at a universally accepted definition or instrument [].

The primary aim of the studies included in this scoping review was the assessment of inpatient satisfaction against various factors in the healthcare facility, which are specific to each individual study or a group of studies.

To this end, the aim of this scoping review is to explore the published literature in the last ten years that is relevant to the experience and satisfaction of patients with mental health disorders in inpatient psychiatric units in various regions of the world and to shed light on the different tools of assessments that are used for this purpose, in addition to identifying the global distribution of the published studies in this field. We hope to provide information, identify the gaps that need to be filled, and explore the key concepts that may help to improve the quality of care and satisfaction in acute psychiatric settings.

2. Methods

This scoping review was structured in adherence with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) statement []. The review followed Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage approach to scoping reviews []. A publication search was conducted in five databases, including PubMed, MEDLINE, CINAHL PsycINFO, and EMBASE. A thorough analysis that included publications from January 2012 to June 2022 was carried out. The rationale behind choosing this particular time frame was to ensure that the articles were recent and that a sufficient number of pertinent studies were available. Extracts from pertinent papers were evaluated and analyzed. Finding a set of publications that concentrated on inpatient satisfaction with mental health care was the main objective of the article screening process. This review covered both qualitative and quantitative research. Review studies such as (systematic reviews, meta-analyses, or scoping reviews), Psychometric research, theses or protocols, publications written in a language other than English, and articles with a theoretical or opinion focus were all excluded from this review. Peer-reviewed journals published each of the featured publications.

The publications were assessed with the help of three reviewers/authors (HE, RS, EO), who independently screened the titles and abstracts and examined all full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria. Each piece required independent assessment by two reviewers, and conflicts were resolved by thorough discussions during personal or virtual meetings; a third reviewer joined to solve the conflicts if consensus was not made between the two reviewers.

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were considered eligible when the following criteria were met:

- (1)

- Outcome: Measurement/studying psychiatric inpatients’ satisfaction as a primary outcome;

- (2)

- Setting: Inpatient psychiatric care (to explore gaps and help in improvement);

- (3)

- Place: All countries and regions were included (for broadening the study scope);

- (4)

- Population:

- -

- Adult patients (more than or equal to 18y) (we chose to focus on adult age group);

- -

- Any mental health diagnosis of adult population, including addiction and alcohol use disorder, for purpose of broadening the study scope;

- (5)

- Type of study:

- -

- Articles published in English language;

- -

- Studies published within the last 10 years (to ensure the recency of evidence);

- -

- Quantitative or qualitative (for better understanding of patients’ viewpoints);

- -

- Individual (non-review) studies, such as cross-sectional, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort studies, case–control studies;

- (6)

- Type of the assessed service:

- -

- Structural design (e.g., hospital design and beds);

- -

- Hospital environment (e.g., cleanliness and food);

- -

- Therapeutic lines (e.g., clozapine, electro-convulsive therapy (ECT), exercise);

- -

- Personnel (e.g., nurses and doctors).

Studies were considered ineligible when any of the following criteria were met:

- (1)

- Setting: Non-psychiatric inpatient units, such as

- -

- Outpatient mental health services;

- -

- Emergency departments;

- -

- Day hospital;

- -

- Long-term care;

- -

- Rehabilitation care;

- (2)

- Outcome:

- -

- Studies measure outcomes other than inpatient satisfaction;

- -

- Satisfaction as a secondary outcome;

- -

- Studies measure the feasibility or acceptability of satisfaction assessment programs;

- (3)

- Population:

- -

- Non-psychiatric patients;

- -

- Non-patients, e.g., relatives, caregivers, healthcare workers, children, and adolescents;

- -

- Patients diagnosed with neurocognitive disorders (dementia and delirium) or primary pediatric mental health conditions (e.g., Tourette syndrome);

- (4)

- Type of study:

- -

- Studies published before 2012;

- -

- Review studies, e.g., systematic reviews, meta-analyses, scoping reviews, psychometric studies, theses, or protocols;

- -

- Studies in a language other than English;

2.2. Search Terms

The search strategy embraced a combination of keywords, including mental health, psychiatric inpatients, and hospital care, and descriptors, including satisfaction, appreciation, contentment, gratification, and experience. These search terms were combined using the AND Boolean operator, with each individual term connected with the OR Boolean operator within each search term.

2.3. Data Extraction

For eligible studies, the following data were extracted using a data extraction form: author name and year of publication, type of study, country of study, diagnosis, number of participants, aim of the study, tools for satisfaction assessment, and study results.

3. Results

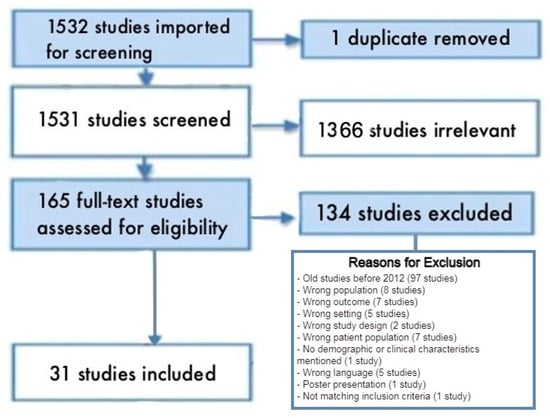

The search strategy identified a total of 1532 studies from the electronic databases searched using Covidence software 2022 (Covidence.org: Melbourne, VIC, Australia). Covidence is a web-based software platform designed to assist in the systematic review process in academic research. Systematic reviews involve the comprehensive and structured analysis of a specific research question by gathering and evaluating relevant studies. Covidence aims to streamline and facilitate this process for researchers []. One article was automatically reviewed by Covidence software and eliminated for duplication. Based only on the title and abstract of the remaining 1531 papers, 165 pieces of research that met the authors’ (HE, EO, RS) eligibility requirements were found. After full-text screening phase, 134 studies were excluded, leaving a total of 31 studies that were eligible to be included in this scoping review. The information is summarized in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

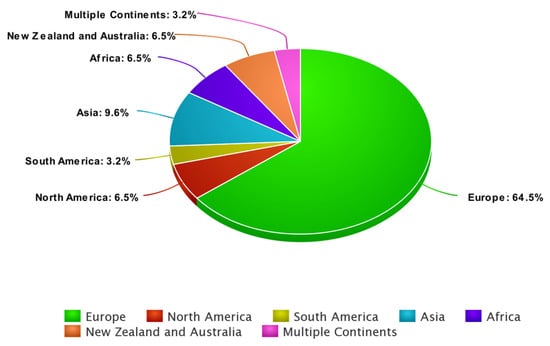

Continent distribution of the studies: Figure 2 demonstrates the summary of the global distribution of the studies included in this review, according to the place of the study (continent). From the figure, most of the studies were conducted in Europe (n = 20, 64.5%), while the other continents were represented to a lesser extent, including North America (n = 2, 6.5%), South America (n = 1, 3.2%), Asia (n = 3, 9.6%), Africa (n = 2, 6.5%), and New Zealand and Australia (n = 2, 6.5%), and multi-continental research (Europe, Africa, and South America) (n = 1, 3.2%). Numerous factors can affect the productivity of continents in mental health research, and it is crucial to remember that research productivity is a complicated and multidimensional phenomenon. Some factors that could be responsible for regional differences in the productivity of mental health research include research infrastructure []; investment in research; cultural attitudes toward mental health []; education and training opportunities []; data accessibility, especially pertinent population-based data; policy and regulatory environment; international collaborations and funding []; and the time frame of the review, which might show significant difference in continental distribution if we altered the time window of the search. According to the study results, Europe took the lead in producing research relevant to psychiatric inpatient satisfaction, which indicates the availability of many of the above-mentioned elements in European countries and the increased concern about the quality of mental health services in this region of the world.

Figure 2.

Summary of continents selected for the review.

Overview of the included studies:

The samples of these studies mainly included psychiatric inpatients with various mental health conditions. The sample size of each study ranged from (n = 15) [] to (n = 7302) []. More than half of the eligible studies (n = 20, 64.5%) were published in the last five years, and almost half of them (n = 14, 45.2%) used a cross-sectional study design. The remaining studies used various study designs such as pragmatic randomized trial (one study), exploratory study (three studies), quasi-experimental study (two studies), multi-center observational study (two studies), short semi-structured interviews (one study), two separate naturalistic trials (one study), qualitative study using a grounded theory (GT) design (one study), longitudinal, mixed-methods research project, using patients interviews with thematic analysis (one study), and pre–post study design (one study).

Diagnosis:

Most of the eligible studies in this scoping review included patients with common psychiatric disorders such as psychosis [,,,,,,], affective disorder [,,], anxiety disorder [,,,,,,,,,], bipolar disorder [,,], depression [,,,,,,,], and drug-related disorders [,,,,]. Some studies included personality disorders and eating disorders [,,].

Survey instruments for satisfaction assessment:

Patient satisfaction questionnaires and different assessment scales were used in each study, including qualitative and quantitative questionnaires to assess inpatient satisfaction. Some studies [,,,,] used the Client Assessment of Treatment (CAT) scale. Patient satisfaction is the main outcome of interest in the CAT scale; the scale is a seven-item survey that asks participants to assess how satisfied they are with various aspects of their inpatient treatment. In another study carried out in Norway [], they described the creation and validation of the Psychiatric Inpatient Patient Experience Questionnaire—On-Site (PIPEQ-OS). The core of the PIPEQ-OS consists of three patient-assessed measures: structure and facilities (six items), patient-centred interaction (six items), and outcome (five items). In another study carried out in Norway [], the UKU Consumer Satisfaction Rating Scale (the UKU-ConSat) was used to measure patient satisfaction at discharge and follow-up. The UKU-ConSat is provided as an interview with eight questions that investigate the patient’s experience with various elements of treatment and care. Mason satisfaction survey was created mainly as a quality improvement tool based on patient satisfaction with treatments []. The survey tool contained a Likert scale for each question ranging from ‘very important to me’ to ‘not at all’ to determine the relative significance of each topic to participants, as well as a final question bank of 50 questions organized into 14 separate subheadings. In some other studies [,], which focused on psychiatric patients’ satisfaction with different ward settings and door policies, all involuntarily committed patients with maintained mental ability were requested to complete the Zurich Satisfaction Questionnaire (ZUF-8), a German variant of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ). The Essen Climate Evaluation Scale (Essen-CES) was used to evaluate the ward atmosphere among other patients [,,]. An exploratory cross-sectional study in Brazil employed the Brazilian Mental Health Services Family Satisfaction Scale (SATIS-BR). The World Health Organization created the SATIS-BR measure to evaluate satisfaction with mental health treatment in three groups: patients, relatives, and professionals. The measure consists of 13 items with five-point Likert scale responses. Greater scores indicate a greater level of satisfaction [,]. In another research study carried out in China, there was no worldwide patient satisfaction scale accessible in the Chinese language for mental patients; thus, the authors created a psychiatric inpatient satisfaction questionnaire for this study. The writers created the questionnaire based on a survey of the literature and expert comments. The psychiatric inpatient satisfaction surveys have traditionally included five domains: quality of treatment, interpersonal interactions, costs of care, non-medical services, and overall satisfaction. The Menninger Quality of Care (MQOC) measure was developed in collaboration with hospital treatment program directors in a study conducted in Texas, USA. The MQOC was designed to be concise, straightforward, useful, relevant, acceptable, and readily accessible. The authors offered descriptive and psychometric assessments of the measure, as well as a technique for using this information to support quality improvement activities []. Another multicentre trial that was carried out across eleven countries used a five-item study-specific questionnaire that was created in consultation with the leaders of each study site to gauge participant satisfaction. Q1. Did you think your hospital stay helped? Q2: How satisfied were you with the staff? Q3. Do you think anything happened to you while you were in the hospital? Q4: Were your rights and preferences taken into account? Q5: Was your privacy right upheld? All questions were translated into the participating nations’ native tongues by the site leaders [].

Factors associated with inpatients satisfaction with mental health services.

Ward atmosphere

Efkemann et al. [], Jovanović N et al. [], Urbanoski et al. [], and Chevalier et al. [] assessed inpatient satisfaction against ward atmosphere and door policies, and they concluded that mixed-sex wards, ward renovation, and ward redesign to make family rooms off wards can potentially improve inpatients satisfaction; additionally, door control policies can impact voluntarily admitted patients’ satisfaction, but it has no significant effect on the satisfaction of involuntarily admitted patients.

Mental illness severity and patient satisfaction

Gebhardt et al. [,] and Kohler et al. [] studied the effect of the severity of mental illness on patient satisfaction and found that patient satisfaction is mostly correlated with low severity of the mental disorder and a high level of global functioning at discharge.

Staff–patient relationship

MacInnes et al. [], Jiang et al. [], Zendjidjian et al. [], Molin et al. [,] and Stewart et al. [] studied staff–patient relationships and focused on the influence of this important factor on patient satisfaction, and they established the value of a good therapeutic connection between clinicians and service users, concluding that patients in the studied psychiatric inpatient care units were overall satisfied with their interaction with healthcare staff, although younger patients reported lower levels of satisfaction.

Voluntary versus involuntary admission

Cannon et al. [], Soininen et al. [], Zahid et al. [], Bjertnaes et al. [], Smith et al. [], Bo et al. [], and Ritsner et al. [] evaluated patient satisfaction in the situation of voluntary versus involuntary admission including coercive measures such as seclusion and mechanical restraint. It was found that many patients felt that seclusion/restraint (S/R) was hardly necessary at all. Less satisfaction was reported by service users who were physically coerced, admitted involuntarily, and received less procedural justice. Higher levels of treatment satisfaction were linked to better functioning, enhanced insight, and therapeutic relationships. Older patients seemed to be against S/R. The results of this study suggested that coerced admission and incorrect or offensive treatment significantly affect satisfaction.

Gender

According to Bird V et al. [] and Faerden et al. [], men and women do not significantly differ in terms of service satisfaction or length of hospital stay; however, patients with personality disorders and short hospital stays are not as satisfied. During their study, Ratner et al. [] found that when it came to “staff”, “care”, and general satisfaction, women were far less satisfied than men. Although most of the participants expressed satisfaction with the inpatient services, they felt that the areas of personal experience, knowledge, and activity were the weakest aspects of the program. Additionally, the authors claimed that five indicators correlated with satisfaction with hospital medical care: insight, physical health satisfaction, self-efficacy, family support, and social anhedonia.

Cats in the ward

Templin et al. [] reported that patients living in wards with a cat had much greater overall satisfaction than patients living in wards without a cat; according to the authors, patients who lived in the company of a cat were also happier with the result of their therapy. Furthermore, they gave much higher ratings to their recreational options, common spaces, and teamwork with their main nurse, social worker, other therapists, and psychologists.

Migration background and procedural fairness

Gaigl et al. [] discovered that patients with a migration history were more satisfied with their mental health care treatment than those without. Simultaneously, no variations in treatment utilization or real obtained mental healthcare were found between individuals with and without a migratory past. Regardless of treatment efficacy, Silva et al. [] found that patients were happier with therapy if they felt it was delivered honestly and fairly. This finding, together with the discovery of a strong link between satisfaction with care and long-term treatment results, emphasizes the critical need to create treatments that increase the procedural fairness of psychiatric care.

Forensic mental illness

Forensic mentally ill patients are those who have interacted with the criminal justice system and have been sent to secure healthcare facilities. MacInnes et al. [] sought to investigate how service users in a forensic mental health context perceive the therapeutic relationship with staff, how they perceive service satisfaction, and whether therapeutic relationship variables are connected with service user satisfaction in secure mental health facilities. The findings of this research highlighted the importance of developing a healthy therapeutic relationship between physicians and service users when measuring their satisfaction with the care and treatment they received in secure hospitals.

Specific treatment components

In order to investigate the satisfaction of individuals receiving treatment in mental health inpatient facilities, as well as to evaluate the viability of such services in multi-country clinical settings (eleven countries), Krupchanka et al. [] carried out a cross-sectional international multi-centre study. The study’s findings showed that a large percentage of respondents were pleased with the inpatient care they received. Every study site had a positive skew in the satisfaction ratings. Paul et al. [] and Stanton et al. [] studied the comments of patients on a completed course of music therapy and physical activity for an MDD or an acute phase of SSD in a cross-sectional worldwide multi-centre research. The benefits of incorporating music therapy and physical exercise were documented as having fresh views, increased emotional fulfilment, being socially closer and more adept, and becoming free and artistically inspired, all of which favourably impacted overall patient satisfaction. Relevant and detailed information was extracted and summarized from the various studies and is presented in Table 1 below.

Table 1.

Summary of studies examining inpatient satisfaction with mental health services.

4. Discussion

This review has addressed patient satisfaction within inpatient mental healthcare settings. The review identified 31 eligible studies that fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The results in the reviewed studies generally demonstrated high levels of respondents’ satisfaction with the inpatient services provided. The satisfaction scores were positively reported across many study sites. More than half of the eligible studies in this review were published in the last five years, which indicates a growing interest in measuring inpatient satisfaction as an important indicator for the quality of hospital services provided to psychiatric inpatients. The results suggest that inpatient satisfaction is mostly correlated with a low severity of the mental disorder, a high level of global functioning at discharge, and an improvement of the disease severity during the course of the treatment, and most patients tend to positively value staff members who maintain a good relationship and spend more time with them [,,,,,]. Similar results of generally satisfied patients were obtained in comparative studies carried out in different parts of the world, e.g., India [], Kuwait [], Kenya [], Nigeria [], Poland [], Thailand [], Finland [], and Israel []. Additionally, unnecessary seclusion/restraint (S/R) of freedom was a significant source of dissatisfaction, and many patients felt that S/R was hardly necessary at all. Yet, they reported some benefits of S/R, such as helping them calm down and control agitation. Older patients seemed to be against S/R [,,]. Other comparative literature also revealed the lack of involvement of the patient or a family member in the care plan or decision making was a prime source of reported patient dissatisfaction, and thus, a therapeutic alliance was a key factor in achieving optimal outcomes through addressing patients’ needs and providing the information that meets their needs. Patients with severe mental conditions or severe incompetency seemed less satisfied with hospital services, which, according to studies, could be attributed to their misjudgment and mental disability [,].

When placed in a hospital ward or other healthcare environment, cats and other animals can benefit the mental health of the patients and increase their satisfaction. Pet therapy or animal-assisted therapy are common terms used to describe this kind of treatment. Some studies provided explanations for why ward cats can help inpatients’ mental health, such as stress reduction, distraction from illness, reduction in feelings of isolation, emotional support, physical activity, and routine altering [,]. It is crucial to remember that although many people can benefit from animal-assisted therapy, it might not be appropriate for everyone. Healthcare settings must take into account various factors, including individual preferences, cultural beliefs, and allergies when implementing such programs. To safeguard the health of both patients and animals, appropriate cleanliness and infection control procedures should also be implemented [,,,]. Migration history and procedural fairness’s impact on mental inpatient satisfaction is a complicated and multidimensional subject that includes a range of elements linked to treatment outcomes, cultural diversity, and the general equity of the healthcare system. The way that procedural fairness and migration background interact is a key factor in determining how satisfied mental inpatients are. Important components include effective communication, cultural competency, and a procedure for treating people fairly and with respect [,]. Regardless of the origin of migration, mental health care providers and systems should work to establish an inclusive and culturally sensitive environment to increase overall patient satisfaction. Furthermore, continuing studies and satisfaction surveys conducted among a variety of patient populations can offer insightful information for future advancements in the provision of mental health services [,,,]. One of the most important ways to guarantee the standard of care and general well-being of patients in forensic mental health settings is to evaluate how satisfied forensic mental inpatients are with mental health services. Assessment and treatment of people with mental health disorders who are involved in the legal system are common components of forensic mental health services. Some ward procedures were found to be of great value in improving satisfaction in forensic psychiatric inpatients, for example, regular staff training, which ensures that healthcare personnel receive training in handling difficult behaviours, empathy, and effective communication. Feedback from family and friends is also an effective tool; their observations can provide a more comprehensive picture of the patient’s experience and point out any gaps in care or communication. Addressing safety concerns is an additional factor because inpatients with forensic mental health issues may face particular safety risks, and for their general satisfaction with the services as well as their well-being, it is imperative to create a safe and encouraging environment as well as provide patients with information about their medications, treatment regimens, and the objectives of their forensic mental health services in a clear and understandable manner. Patients who are well-informed and educated are more likely to feel engaged in their treatment [,,,].

Interestingly, when the studies are assessing the quantitative outcomes of inpatient satisfaction and the emphasis of the research studies is shifted from overall satisfaction to particular difficulties and experiences that psychiatric inpatients encounter, the overall picture drastically changes. For example, patients reported that physical/psychological abuse, staff misbehaviour [,,,], inadequate living conditions, and limited information availability were major sources of discontent [,,,]. The gap between overall satisfaction and many particular or specific issues during hospital stays should be addressed. When studies adopt a qualitative research methodology, the evidence of patient suffering is more visible. Open-ended surveys, focus groups, and interviews are a few examples of qualitative research methodologies that are used to investigate and comprehend the richness and depth of human experiences. These approaches enable a more thorough and nuanced analysis of patients’ viewpoints when used to measure patient satisfaction in healthcare, including mental health services. Qualitative research methods increase the visibility of patient suffering for a number of reasons, including rich narrative data, which are directly gathered from patients using qualitative methods. Patients can use open-ended questions to verbally describe their experiences, feelings, and perceptions. This narrative method offers a thorough and contextualized comprehension of the elements impacting their level of satisfaction or discontent. Another reason is that qualitative research can reveal aspects of care that may go unnoticed in quantitative studies by involving patients in candid discussions. Patients may disclose concerns, unfulfilled needs, or areas in need of improvement. This can involve problems with emotional support, communication, and general care quality [,,,,,,]. In another context, expectations that were met or disregarded during the hospital stay play a crucial role in determining patient satisfaction because it is hypothesized that when expectations are met, people will be satisfied regardless of the calibre of care. Due to either the excellent care provided to the patient during their hospital stay or the mental inpatient’s low expectations and satisfaction threshold, for instance, when there is no chance of reaching their goal, a person may adjust to their surroundings by lowering their expectations [,]. Although the standards for each person in these facilities may differ, these environments usually have certain features in common, such as safety and security, respect for others, personal hygiene, medication management, family involvement, and discharge planning. Remember that exact expectations can change depending on the policies of the facility and laws in the area. Inpatient satisfaction has also been observed to be greater among elderly patients >44 years old. According to studies, older patients may be more adaptable to rigid ward routines, more compliant with treatment regimens, and more respectful, whereas younger patients may be more defiant, less accepting of their situation, and more resistant to staff instructions due to minor age differences [,]. Satisfaction with inpatient care has also been observed as lower among non-white patient groups in studies with a majority white population, which was ascribed in the research to the uneven level of services supplied to the white population [,,]. Furthermore, in some additional studies, it was discovered that patients with poor mental health had lower short-term and long-term satisfaction than the rest of the patients; in this case, the studies assumed that impaired mental function and poor judgement were the main reasons for this observation [,]. Overall, there is evidence that mental inpatients are less happy than individuals released from the hospital after treatment of acute physical diseases []. There are several factors that may contribute to the perception that mental inpatients are less happy on average compared to other patients with physical diseases; for example, there is a strong social stigma associated with mental health issues, which can affect how people see themselves and are seen by others. Mental health patients may experience feelings of shame, loneliness, and low self-esteem as a result of this stigma. Another factor is lack of knowledge; as compared to physical illnesses, society may not be as sympathetic or understanding of mental health problems. This ignorance can make mental health patients feel more alone and make it more difficult for them to get the support they need. Furthermore, managing mental health conditions can present ongoing challenges as well as a risk of relapse. Mental health patients can experience anxiety and decreased levels of happiness as a result of this uncertainty and the possibility of setbacks. Additionally, treatment duration compared to the treatment of certain acute physical diseases, especially in an inpatient setting, may take longer. Prolonged absences from familiar surroundings and one’s home can exacerbate feelings of unease and discontent [,,,,]. Patient satisfaction is a wide statistic that is often used to evaluate general healthcare interventions in the context of mental health treatment []. Despite a large body of research on inpatient satisfaction in mental health services, there are still some noteworthy research gaps that call for more study. By identifying and filling these gaps, we can improve the delivery of mental health care by gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing patient satisfaction. The following are some possible research gaps in the assessment of inpatient satisfaction. Diversity and cultural sensitivity: The effects of diversity and cultural factors on inpatient satisfaction have received little attention in the literature. Developing culturally sensitive care models requires examining how cultural differences affect patient expectations, preferences, and satisfaction with mental health services []. Patients’ expectations, prior treatment experiences, and knowledge about services should all be taken into consideration in future research on patient satisfaction. Patient-reported outcome: Results as reported by patients are in need of more research that directly incorporates patient-reported outcomes, as many studies currently rely on provider- or system-reported outcomes. For a thorough assessment, it is imperative to evaluate satisfaction from the patient’s point of view, taking into account their opinions about communication, participation in decision making, and overall experience []. Integration of mental and physical health services: Health Studies frequently concentrate on mental health services separately, but the significance of combining mental and physical healthcare is becoming increasingly acknowledged. There is growing interest in learning how the integration of these services affects overall health outcomes and inpatient satisfaction. Peer support’s impact: Further research is needed to fully understand the impact of peer support on inpatient satisfaction. Examining the impact of peer support programs on patient experiences, satisfaction, and engagement in inpatient mental health settings can yield important information for enhancing care [,,]. Telehealth and technology: Research on the effects of telehealth and technology on inpatient satisfaction is necessary, as these modalities are increasingly being used in mental health services. It is necessary to investigate how virtual interactions affect patient perceptions and satisfaction in comparison to traditional in-person care [,]. And finally, instruments and procedures for measurement: Measurement instruments that are validated and standardized are required for evaluating inpatient satisfaction in mental health settings. Furthermore, investigating cutting-edge research techniques like mixed methods and qualitative approaches can offer a more complex understanding of patient experiences [,,,]. The goal of this scoping review was to explore patient satisfaction in mental health inpatient facilities by explicitly evaluating such services from a patient viewpoint and analyzing their practicability in multi-country clinical settings. Using this technique for service evaluation, we were able to efficiently produce patient responses from all over the world and collect data for the aforementioned purpose. We were also able to identify the gaps in the current research works that need to be further addressed in future research. The majority of the studies used in this scoping review adopted a pre-existing inpatient satisfaction questionnaire or developed a new one, which seemed to be effective and acceptable in quality. It would also be useful for future studies to explore patient satisfaction with care by using other technological measures like electronic surveys, which seem to be easier and less time-consuming for patients to complete, as well as for the research team to interpret the results by using data analysis software like SPSS version 29 [,]. Currently, a pragmatic stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial is running in the province of Alberta, Canada, where the researchers meet with patients who are about to be discharged from the psychiatric units in the main hospitals all over the province and they invite them to fill out a satisfaction survey digitally, using an online link that includes questions related to their hospital experience and the degree of satisfaction with the services provided to them. In this multi-centre trial, the research team provides two main interventions: daily supportive text messages (text for support) and mental health peer support []. It would be useful to expand the focus of future studies and reviews to explore the satisfaction of psychiatric patients with novel and productive services, such as peer support programs and other technological supportive measures, such as text for support, which has demonstrated high effectiveness among patients [,,,].

According to the research we reviewed, we strongly recommend that clinicians and other healthcare professionals consider the following points to achieve better therapeutic alliance and satisfaction of their inpatients: a clear discharge plan, less coercive treatment during the hospital stay, more personalized higher quality information and teaching conducted by staff to patients about the mental disorders, and specific treatment components that are well perceived by patients, such as physical exercise sessions and music therapy, which all appear to be associated with higher inpatient satisfaction with care. Ward atmosphere and design are also crucial considerations. Personal contact, such as improved therapeutic connections with staff, particularly nurses, is another crucial element.

5. Limitations

The authors of this scoping review are aware of various limitations. First, we exclusively examined English language databases for this scoping review. Considering our criteria, great care was taken to find all pertinent studies for this evaluation. We could, however, have overlooked some important research, particularly those that were written in different languages. Non-English language studies with negative or null findings may go unpublished. This could result in a skewed representation of the available evidence. This limitation could be mitigated in future research, like conducting a broader search that includes databases in other languages. Additionally, this review did not assess the risk of bias or provide a meta-analysis outcome; given that the different nature of study outcomes, including qualitative information, measurement scales, and questionnaires from diverse geographical regions, this might potentially cause variations in the evaluations and outcomes. We suggest that future research may consider a more in-depth analysis of the risk of bias or conduct a meta-analysis if feasible. Finally, aiming to cover the recently updated research evidence, this review covered a certain time frame for searches in the literature, which could have overlooked other valuable previous research work carried out before this period. We encourage future researchers to consider a more extensive time frame to ensure a comprehensive review of the literature.

6. Conclusions

This scoping review highlighted the generally high levels of patient satisfaction within inpatient mental healthcare settings. The findings indicate a growing interest in measuring inpatient satisfaction as a crucial indicator of the quality of hospital services provided to psychiatric inpatients. Patient satisfaction is notably correlated with factors such as the severity of the mental disorder, global functioning at discharge, improvement during treatment, and positive interactions with staff. This review underscored the positive impact of interventions such as animal-assisted therapy or pet therapy for mental health and patient satisfaction, but it also highlighted the need to implement these programmes with consideration for individual preferences and cultural sensitivity. Furthermore, the complex relationship between migration history and procedural fairness on mental inpatient satisfaction is explored, emphasizing the importance of effective communication, cultural competency, and fair treatment. This review notes that although overall satisfaction is high, it is important to address certain problems that psychiatric inpatients face, like abuse, staff misbehaviour, living conditions, and information availability. The use of qualitative research methods was highlighted for a nuanced understanding of patient experiences and satisfaction, revealing aspects that may be overlooked in quantitative studies. Several factors influencing satisfaction were identified in this review, including age, cultural background, mental health conditions, societal stigma, and treatment duration. This emphasizes the need for future research to fill gaps in understanding diversity, cultural sensitivity, patient-reported outcomes, integration of mental and physical health services, the impact of peer support, and the effects of telehealth and technology on inpatient satisfaction. In addition to offering insights into the current status of inpatient satisfaction in mental health facilities, the scoping review identified important areas for relevant ongoing research. The ongoing stepped-wedge cluster-randomized trial in Alberta, Canada, using digital surveys and interventions like daily supportive text messages and mental health peer support, exemplifies the evolving landscape of research methodologies to further explore and enhance psychiatric patient satisfaction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, and supervision: V.I.O.A.; supervision: Y.W.; conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis, and writing original draft: H.E.; methodology and data curation: R.S.; data curation: E.O.; review and editing: H.E., R.S., E.O., N.N., Y.W. and V.I.O.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions (202010086). The funder had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the results for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Williams, B. Patient satisfaction: A valid concept? Soc. Sci. Med. 1994, 38, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Thornicroft, G.; Knapp, M.; Whiteford, H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 2007, 370, 878–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Druss, B.G.; Perlick, D.A. The Impact of Mental Illness Stigma on Seeking and Participating in Mental Health Care. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 2014, 15, 37–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; McCabe, R.; Bullenkamp, J.; Hansson, L.; Lauber, C.; Martinez-Leal, R.; Rössler, W.; Salize, H.; Svensson, B.; Torres-Gonzales, F.; et al. Structured patient-clinician communication and 1-year outcome in community mental healthcare: Cluster randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2007, 191, 420–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flückiger, C.; Del Re, A.C.; Wampold, B.E.; Symonds, D.; Horvath, A.O. How central is the alliance in psychotherapy? A multilevel longitudinal meta-analysis. J. Couns. Psychol. 2012, 59, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, B. Patient satisfaction. J. Cutan. Aesthet. Surg. 2010, 3, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, R.L. Satisfaction with care. In Understanding Health Care Outcome Research, 2nd ed.; Jones and Bartlett Publishers: Sudbury, MA, USA, 2006; pp. 185–216. [Google Scholar]

- Henn, R.F., 3rd; Kang, L.; Tashjian, R.Z.; Green, A. Patients′ preoperative expectations predict the outcome of rotator cuff repair. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2007, 89, 1913–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, B. Defining and Measuring Patient Satisfaction. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2016, 41, 929–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, R.N.; Hand Surgery Quality, C. Quality and Value in an Evolving Health Care Landscape. J. Hand Surg. Am. 2016, 41, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adib-Hajbaghery, M.; Aghajani, M. Patients dignity in nursing. Nurs. Midwifery Stud. 2015, 4, e22809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parandeh, A.; Khaghanizade, M.; Mohammadi, E.; Mokhtari-Nouri, J. Nurses′ human dignity in education and practice: An integrated literature review. Iran. J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 2016, 21, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moudatsou, M.; Stavropoulou, A.; Philalithis, A.; Koukouli, S. The Role of Empathy in Health and Social Care Professionals. Healthcare 2020, 8, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kippenbrock, T.; Emory, J.; Lee, P.; Odell, E.; Buron, B.; Morrison, B. A national survey of nurse practitioners′ patient satisfaction outcomes. Nurs. Outlook 2019, 67, 707–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O′Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O′Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Social. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Better Systematic Review Management. Available online: https://www.covidence.org/ (accessed on 28 May 2023).

- Saxena, S.; Funk, M.; Chisholm, D. WHO′s Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020: What can psychiatrists do to facilitate its implementation? World Psychiatry 2014, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirmayer, L.J. Cultural competence and evidence-based practice in mental health: Epistemic communities and the politics of pluralism. Soc. Sci. Med. 2012, 75, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Saxena, S.; Lund, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Baingana, F.; Bolton, P.; Chisholm, D.; Collins, P.Y.; Cooper, J.L.; Eaton, J.; et al. The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. Lancet 2018, 392, 1553–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, V.; Prince, M. Global mental health: A new global health field comes of age. JAMA 2010, 303, 1976–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, V.J.; Giacco, D.; Nicaise, P.; Pfennig, A.; Lasalvia, A.; Welbel, M.; Priebe, S. In-patient treatment in functional and sectorised care: Patient satisfaction and length of stay. Br. J. Psychiatry 2018, 212, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, N.; Lotter, C.; van Staden, W. Patient Reflections on Individual Music Therapy for a Major Depressive Disorder or Acute Phase Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorder. J. Music. Ther. 2020, 57, 168–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bo, B.; Ottesen, O.H.; Gjestad, R.; Jorgensen, H.A.; Kroken, R.A.; Loberg, E.M.; Johnsen, E. Patient satisfaction after acute admission for psychosis. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2016, 70, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, R.P.; Steinert, T. Should severely disturbed psychiatric patients be distributed or concentrated in specialized wards? An empirical study on the effects of hospital organization on ward atmosphere, aggressive behavior, and sexual molestation. Eur. Psychiatry 1999, 14, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godoy, J.A.; Pavan, G.; Monteiro, R.T.; Motta, L.S.; Pacheco, M.A.; Nogueira, E.L.; Spanemberg, L. Satisfaction with care in a Brazilian psychiatric inpatient unit: Differences in perceptions among patients according to type of health insurance. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2019, 41, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Rakofsky, J.; Zhou, H.; Hu, L.; Liu, T.; Wu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.L. Satisfaction of psychiatric inpatients in China: Clinical and institutional correlates in a national sample. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.; Pauli, G.; Diringer, O.; Morandi, S.; Bonsack, C.; Golay, P. Perceived fairness as main determinant of patients′ satisfaction with care during psychiatric hospitalisation: An observational study. Int. J. Law. Psychiatry 2022, 82, 101793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, D.; Roche, E.; O′Loughlin, K.; Brennan, D.; Madigan, K.; Lyne, J.; Feeney, L.; O′Donoghue, B. Satisfaction with services following voluntary and involuntary admission. J. Ment. Health 2014, 23, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Efkemann, S.A.; Bernard, J.; Kalagi, J.; Otte, I.; Ueberberg, B.; Assion, H.J.; Zeiss, S.; Nyhuis, P.W.; Vollmann, J.; Juckel, G.; et al. Ward Atmosphere and Patient Satisfaction in Psychiatric Hospitals with Different Ward Settings and Door Policies. Results from a Mixed Methods Study. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, V.; Miglietta, E.; Giacco, D.; Bauer, M.; Greenberg, L.; Lorant, V.; Moskalewicz, J.; Nicaise, P.; Pfennig, A.; Ruggeri, M.; et al. Factors associated with satisfaction of inpatient psychiatric care: A cross country comparison. Psychol. Med. 2020, 50, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, A.; Ntala, E.; Fung, C.; Priebe, S.; Bird, V.J. Exploring the initial experience of hospitalisation to an acute psychiatric ward. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman-Parra, J.; Aguilera-Serrano, C.; Garcia-Sanchez, J.A.; Garcia-Spinola, E.; Torres-Campos, D.; Villagran, J.M.; Moreno-Kustner, B.; Mayoral-Cleries, F. Experience coercion, post-traumatic stress, and satisfaction with treatment associated with different coercive measures during psychiatric hospitalization. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 448–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjertnaes, O.; Iversen, H.H. Inpatients′ assessment of outcome at psychiatric institutions: An analysis of predictors following a national cross-sectional survey in Norway. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e023587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jovanovic, N.; Miglietta, E.; Podlesek, A.; Malekzadeh, A.; Lasalvia, A.; Campbell, J.; Priebe, S. Impact of the hospital built environment on treatment satisfaction of psychiatric in-patients. Psychol. Med. 2022, 52, 1969–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molin, J.; Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.M. Quality of interactions influences everyday life in psychiatric inpatient care--patients′ perspectives. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-Being 2016, 11, 29897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molin, J.; Vestberg, M.; Lovgren, A.; Ringner, A.; Graneheim, U.H.; Lindgren, B.M. Rather a Competent Practitioner than a Compassionate Healer: Patients′ Satisfaction with Interactions in Psychiatric Inpatient Care. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 42, 549–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanoski, K.A.; Mulsant, B.H.; Novotna, G.; Ehtesham, S.; Rush, B.R. Does the redesign of a psychiatric inpatient unit change the treatment process and outcomes? Psychiatr. Serv. 2013, 64, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaigl, G.; Täumer, E.; Allgöwer, A.; Becker, T.; Breilmann, J.; Falkai, P.; Gühne, U.; Kilian, R.; Riedel-Heller, S.G.; Ajayi, K.; et al. The role of migration in mental healthcare: Treatment satisfaction and utilization. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Köhler, S.; Unger, T.; Hoffmann, S.; Steinacher, B.; Fydrich, T. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric treatment and its relation to treatment outcome in unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 2015, 19, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupchanka, D.; Khalifeh, H.; Abdulmalik, J.; Ardila-Gomez, S.; Armiya′u, A.Y.; Banjac, V.; Baranov, A.; Bezborodovs, N.; Brecic, P.; Cavajda, Z.; et al. Satisfaction with psychiatric in-patient care as rated by patients at discharge from hospitals in 11 countries. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2017, 52, 989–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Templin, J.C.; Hediger, K.; Wagner, C.; Lang, U.E. Relationship Between Patient Satisfaction and the Presence of Cats in Psychiatric Wards. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2018, 24, 1219–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soininen, P.; Välimäki, M.; Noda, T.; Puukka, P.; Korkeila, J.; Joffe, G.; Putkonen, H. Secluded and restrained patients′ perceptions of their treatment. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 22, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhardt, S.; Wolak, A.M.; Huber, M.T. Patient satisfaction and clinical parameters in psychiatric inpatients--the prevailing role of symptom severity and pharmacologic disturbances. Compr. Psychiatry 2013, 54, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Gruyters, T. Patients′ assessment of treatment predicting outcome. Schizophr. Bull. 1995, 21, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priebe, S.; Gruyters, T.; Heinze, M.; Hoffmann, C.; Jäkel, A. Subjective evaluation criteria in psychiatric care—Methods of assessment for research and general practice. Psychiatr. Prax. 1995, 22, 140–144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Johnsen, E.; Kroken, R.A.; Wentzel-Larsen, T.; Jorgensen, H.A. Effectiveness of second-generation antipsychotics: A naturalistic, randomized comparison of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone. BMC Psychiatry 2010, 10, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cannon, T.; Taylor, S.; Friedman, S.H. Satisfaction guaranteed? Forensic consumer satisfaction survey. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, J.; Lamprecht, F.; Wittmann, W.W. Satisfaction with inpatient management. Development of a questionnaire and initial validity studies. Psychother. Psychosom. Med. Psychol. 1989, 39, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schalast, N.; Tonkin, M. The Essen Climate Evaluation Schema EssenCES: A Manual and More; Hogrefe Verlag GmbH & Co. KG: Göttingen, Germany, 2016; p. 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandeira, M.; Silva, M. Patients′ Satisfaction with Mental Health Services Scale (SATIS-BR): Validation study. J. Bras. de Psiquiatr. 2011, 61, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, A.; Fowler, J.C.; Allen, J.G.; Ellis, T.E.; Hardesty, S.; Groat, M.; O′Malley, F.; Woodson, H.; Mahoney, J.; Frueh, B.C.; et al. Assessing and addressing patient satisfaction in a longer-term inpatient psychiatric hospital: Preliminary findings on the Menninger Quality of Care measure and methodology. Qual. Manag. Health Care 2014, 23, 178–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacInnes, D.; Courtney, H.; Flanagan, T.; Bressington, D.; Beer, D. A cross sectional survey examining the association between therapeutic relationships and service user satisfaction in forensic mental health settings. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zendjidjian, X.Y.; Auquier, P.; Lancon, C.; Loundou, A.; Parola, N.; Faugere, M.; Boyer, L. Determinants of patient satisfaction with hospital health care in psychiatry: Results based on the SATISPSY-22 questionnaire. Patient Prefer. Adherence 2014, 8, 1457–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Stewart, D.; Burrow, H.; Duckworth, A.; Dhillon, J.; Fife, S.; Kelly, S.; Marsh-Picksley, S.; Massey, E.; O′Sullivan, J.; Qureshi, M.; et al. Thematic analysis of psychiatric patients′ perceptions of nursing staff. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahid, M.A.; Ohaeri, J.U.; Al-Zayed, A.A. Factors associated with hospital service satisfaction in a sample of Arab subjects with schizophrenia. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ritsner, M.S.; Farkash, H.; Rauchberger, B.; Amrami-Weizman, A.; Zendjidjian, X.Y. Assessment of health needs, satisfaction with care, and quality of life in compulsorily admitted patients with severe mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 267, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Færden, A.; Bølgen, B.; Løvhaug, L.; Thoresen, C.; Dieset, I. Patient satisfaction and acute psychiatric inpatient treatment. Nord. J. Psychiatry 2020, 74, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ratner, Y.; Zendjidjian, X.Y.; Mendyk, N.; Timinsky, I.; Ritsner, M.S. Patients′ satisfaction with hospital health care: Identifying indicators for people with severe mental disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2018, 270, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, R.; Donohue, T.; Garnon, M.; Happell, B. Participation in and Satisfaction with an Exercise Program for Inpatient Mental Health Consumers. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2016, 52, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seed, M.S.; Torkelson, D.J.; Alnatour, R. The role of the inpatient psychiatric nurse and its effect on job satisfaction. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 31, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, M.M.; Chadda, R.K.; Bapna, S.J. Assessment of hospital services by consumers: A study from a psychiatric setting. Indian. J. Public Health 2003, 47, 14–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wagoro, M.C.; Othieno, C.J.; Musandu, J.; Karani, A. Structure and process factors that influence patients′ perception of inpatient psychiatric nursing care at Mathari Hospital, Nairobi. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2008, 15, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olusina, A.K.; Ohaeri, J.U.; Olatawura, M.O. Patient and staff satisfaction with the quality of in-patient psychiatric care in a Nigerian general hospital. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2002, 37, 283–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zajac, J.; Rymaszewska, J.; Hadryś, T.; Adamowski, T.; Szurmińska, M.; Kiejna, A. Patients′ opinions on psychiatric hospital treatment. Psychiatr. Pol. 2006, 40, 671–681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thapinta, D.; Anders, R.L.; Wiwatkunupakan, S.; Kitsumban, V.; Vadtanapong, S. Assessment of patient satisfaction of mentally ill patients hospitalized in Thailand. Nurs. Health Sci. 2004, 6, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuosmanen, L.; Hätönen, H.; Jyrkinen, A.R.; Katajisto, J.; Välimäki, M. Patient satisfaction with psychiatric inpatient care. J. Adv. Nurs. 2006, 55, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remnik, Y.; Melamed, Y.; Swartz, M.; Elizur, A.; Barak, Y. Patients′ satisfaction with psychiatric inpatient care. Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat. Sci. 2004, 41, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Krupchanka, D.; Kruk, N.; Murray, J.; Davey, S.; Bezborodovs, N.; Winkler, P.; Bukelskis, L.; Sartorius, N. Experience of stigma in private life of relatives of people diagnosed with schizophrenia in the Republic of Belarus. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2016, 51, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, S.B.; Dawson, K.S. The effects of animal-assisted therapy on anxiety ratings of hospitalized psychiatric patients. Psychiatr. Serv. 1998, 49, 797–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabei, V.; De Ronchi, D.; La Ferla, T.; Moretti, F.; Tonelli, L.; Ferrari, B.; Forlani, M.; Atti, A.R. Animal-assisted interventions for elderly patients affected by dementia or psychiatric disorders: A review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coakley, A.B.; Annese, C.D.; Empoliti, J.H.; Flanagan, J.M. The Experience of Animal Assisted Therapy on Patients in an Acute Care Setting. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2021, 30, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virupaksha, H.G.; Kumar, A.; Nirmala, B.P. Migration and mental health: An interface. J. Nat. Sci. Biol. Med. 2014, 5, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varkey, B. Principles of Clinical Ethics and Their Application to Practice. Med. Princ. Pract. 2021, 30, 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyle, S.; Walsh, T. Procedural fairness in mental health review tribunals: The views of patient advocates. Psychiatr. Psychol. Law. 2021, 28, 163–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiva, A.; Haden, S.C.; Brooks, J. Psychiatric civil and forensic inpatient satisfaction with care: The impact of provider and recipient characteristics. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2009, 44, 979–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macinnes, D.; Beer, D.; Reynolds, K.; Kinane, C. Carers of forensic mental health in-patients: What factors influence their satisfaction with services? J. Ment. Health 2013, 22, 528–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- MacInnes, D.; Masino, S. Psychological and psychosocial interventions offered to forensic mental health inpatients: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e024351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dickens, G.L.; Suesse, M.; Snyman, P.; Picchioni, M. Associations between ward climate and patient characteristics in a secure forensic mental health service. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2014, 25, 195–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, M.; Stevenson, D. Violence and abuse in psychiatric in-patient institutions: A South African perspective. Int. J. Law. Psychiatry 2006, 29, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anczewska, M.; Indulska, A.; Raduj, J.; Pałyska, M.; Prot, K. The patients’ view on psychiatric hospitalisation--a qualitative evaluation. Psychiatr. Pol. 2007, 41, 427–434. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, B.; Hansson, L. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care. The influence of personality traits, diagnosis and perceived coercion. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 1994, 90, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, L.; Baumstarck-Barrau, K.; Cano, N.; Zendjidjian, X.; Belzeaux, R.; Limousin, S.; Magalon, D.; Samuelian, J.C.; Lancon, C.; Auquier, P. Assessment of psychiatric inpatient satisfaction: A systematic review of self-reported instruments. Eur. Psychiatry 2009, 24, 540–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.A.; Furegato, A.R.; Pereira, A. The lived experience of long-term psychiatric hospitalization of four women in Brazil. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2005, 41, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, J.M. Qualitative Health Research: Creating a New Discipline; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Thorogood, N.; Green, J. Qualitative methods for health research. Qual. Methods Health Res. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Teaching Theory Construction with Initial Grounded Theory Tools: A Reflection on Lessons and Learning. Qual. Health Res. 2015, 25, 1610–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crow, R.; Gage, H.; Hampson, S.; Hart, J.; Kimber, A.; Storey, L.; Thomas, H. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: Implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol. Assess. 2002, 6, 1–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiva, A.; Haden, S.C.; Brooks, J. Forensic and civil psychiatric inpatients: Development of the inpatient satisfaction questionnaire. J. Am. Acad. Psychiatry Law. 2009, 37, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soergaard, K.W.; Nivison, M.; Hansen, V.; Oeiesvold, T. Treatment needs and acknowledgement of illness—importance for satisfaction with psychiatric inpatient treatment. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2008, 8, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkman, S.; Davies, S.; Leese, M.; Phelan, M.; Thornicroft, G. Ethnic differences in satisfaction with mental health services among representative people with psychosis in south London: PRiSM study 4. Br. J. Psychiatry 1997, 171, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, K.C.; Patel, M.R.; Nie, J.W.; Hartman, T.J.; Ribot, M.A.; Parsons, A.W.; Pawlowski, H.; Prabhu, M.C.; Vanjani, N.N.; Singh, K. Presenting Mental Health Influences Postoperative Clinical Trajectory and Long-Term Patient Satisfaction After Lumbar Decompression. World Neurosurg. 2022, 164, e649–e661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, G.S.; Khow, Y.Z.; Tay, D.K.; Lo, N.N.; Yeo, S.J.; Liow, M.H.L. Preoperative Mental Health Influences Patient-Reported Outcome Measures and Satisfaction After Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty 2021, 36, 2878–2886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoff, R.A.; Rosenheck, R.A.; Meterko, M.; Wilson, N.J. Mental illness as a predictor of satisfaction with inpatient care at Veterans Affairs hospitals. Psychiatr. Serv. 1999, 50, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrigan, P.W.; Watson, A.C. Understanding the impact of stigma on people with mental illness. World Psychiatry 2002, 1, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, M.; Uman, T. Experiences of acute care by persons with mental health problems: An integrative literature review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 27, 789–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molina-Mula, J.; Gallo-Estrada, J. Impact of Nurse-Patient Relationship on Quality of Care and Patient Autonomy in Decision-Making. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alegría, M.; NeMoyer, A.; Falgàs Bagué, I.; Wang, Y.; Alvarez, K. Social Determinants of Mental Health: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2018, 20, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Posluns, K.; Gall, T.L. Dear Mental Health Practitioners, Take Care of Yourselves: A Literature Review on Self-Care. Int. J. Adv. Couns. 2020, 42, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhui, K.; Bhugra, D.; Goldberg, D. Cross-cultural validity of the Amritsar Depression Inventory and the General Health Questionnaire amongst English and Punjabi primary care attenders. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2000, 35, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, A.; von Känel, R.; Slavich, G.M. The Psychobiology of Bereavement and Health: A Conceptual Review from the Perspective of Social Signal Transduction Theory of Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 565239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, G.; Bryant, W. Peer support in adult mental health services: A metasynthesis of qualitative findings. Psychiatr. Rehabil. J. 2013, 36, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, L.; Chinman, M.; Kloos, B.; Weingarten, R.; Stayner, D.; Tebes, J.K. Peer support among individuals with severe mental illness: A review of the evidence. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 1999, 6, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilty, D.M.; Luo, J.S.; Morache, C.; Marcelo, D.A.; Nesbitt, T.S. Telepsychiatry: An overview for psychiatrists. CNS Drugs 2002, 16, 527–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong, V.I.O.; Hrabok, M.; Vuong, W.; Shalaby, R.; Noble, J.M.; Gusnowski, A.; Mrklas, K.J.; Li, D.; Urichuk, L.; Snaterse, M.; et al. Changes in Stress, Anxiety, and Depression Levels of Subscribers to a Daily Supportive Text Message Program (Text4Hope) During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Cross-Sectional Survey Study. JMIR Ment. Health 2020, 7, e22423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agyapong, V.I.; McLoughlin, D.M.; Farren, C.K. Six-months outcomes of a randomised trial of supportive text messaging for depression and comorbid alcohol use disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 151, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eboreime, E.; Shalaby, R.; Mao, W.; Owusu, E.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Bales, K.; MacMaster, F.P.; McNeil, D.; Rittenbach, K.; et al. Reducing readmission rates for individuals discharged from acute psychiatric care in Alberta using peer and text message support: Protocol for an innovative supportive program. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaby, R.; Spurvey, P.; Knox, M.; Rathwell, R.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Urichuk, L.; Snaterse, M.; Greenshaw, A.J.; Li, X.M.; et al. Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation Measures for Patients Discharged from Acute Psychiatric Care: Four-Arm Peer and Text Messaging Support Controlled Observational Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shalaby, R.; Hrabok, M.; Spurvey, P.; Abou El-Magd, R.M.; Knox, M.; Rude, R.; Vuong, W.; Surood, S.; Urichuk, L.; Snaterse, M.; et al. Recovery following Peer and Text Messaging Support After Discharge from Acute Psychiatric Care in Edmonton, Alberta: Controlled Observational Study. JMIR Form. Res. 2021, 5, e27137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).