Abstract

Stochastic flows mimicking 2D turbulence in compressible media are considered. Particles driven by such flows can collide and we study the collision (caustic) frequency. Caustics occur when the Jacobian of a flow vanishes. First, a system of nonlinear stochastic differential equations involving the Jacobian is derived and reduced to a smaller number of unknowns. Then, for special cases of the stochastic forcing, upper and lower bounds are found for the mean number of caustics as a function of Stokes number. The bounds yield an exact asymptotic for small Stokes numbers. The efficiency of the bounds is verified numerically. As auxiliary results we give rigorous proofs of the well known expressions for the caustic frequency and Lyapunov exponent in the one-dimensional model. Our findings may also be used for estimating the mean time when a 2D Riemann type partial differential equation with a stochastic forcing loses uniqueness of solutions.

1. Introduction

We address a stochastic flow [1] covered by the following Ito stochastic differential equations

where phase variables and are interpreted as the position and velocity of fluid particles moving in a turbulent flow. Here the random forcing is assumed to be a Gaussian white noise in time and a statistically homogeneous random field in space, i.e.,

where is its space covariance matrix. A constant non-random parameter is called the Lagrangian correlation time.

In particular, the motion of a single particle in the framework (1) is covered by a Langevin equation for the velocity

where is a standard Brownian motion in 2D, thereby the Lagrangian velocity of the particle is simply a well known (two-dimensional) Ornstein–Uhlenback process and its position is an integrated Ornstein–Uhlenback process.

In general the motion of any number n of the particles is described by a diffusion process in for the vector of positions/velocities with a drift and diffusivity matrix expressed in terms of and [2].

To introduce the problem we focus on, let us supply (1) with initial conditions where is a given deterministic function (the initial Eulerian velocity field), i.e., each particle starts from a certain position with a certain velocity completely determined by its position, and introduce the Jacobian

where is the solution of (1) satisfying the above initial conditions or, in simple words, the position of the particle at moment t starting at position .

An important physical meaning of the Jacobian can be seen from the following. Let the initial position be a random variable independent of the flow with probability density , then for the conditional density conditioned on the flow is given by

It is well known [3] that for incompressible flows , hence the density of the particles does not change at any point in the fluid. A remarkable and one of the most important feature of model (1) is that it yields a compressible flow for any value of and any function , e.g., [4]. Moreover, may take zero values leading to an infinite density at certain points of the fluid called caustics.

Let be the mean frequency (intensity) of caustic occurrence and

the top Lyapunov exponent (LE) for (1).

Despite numerous studies of this important quantity in physical literature (see recent comprehensive reviews in [4,5]) almost all remarkable analytical results were obtained in the one dimensional case, among them explicit expressions [6,7] should be mentioned first

where , s is Stokes number (the ratio of Lagrangian and Eulerian time scales, e.g., [2]), M is the modulus of the Airy function. Furthermore, to our best knowledge no rigorous proofs of formulas (3) were presented so far. Furthermore, worth noting expressions for and in a quite different setup when the noise is a telegraph process rather then the Gaussian white noise [6]. Even though that results were proven rigorously it still was a one dimensional case that hard to consider as a turbulence model.

As for two dimensions, we found no analytical results whatsoever concerning with the dependence of on s, while some asymptotics for LE were obtained in [2,6,7]. Moreover, exact expressions for LE were derived as well in very special degenerate cases [7].

Advances in this work could be summarized as follows.

(i) Rigorous proofs of (3) were given.

(ii) In the framework of general 2D model (1) a system of stochastic differential equations was derived in four unknowns, involving the Jacobian.

(iii) The system was efficiently investigated for two cases of a special forcing in (1) yielding an exact asymptotic of as and reasonable numerical boundaries for in a wide range of s. That results may be used for estimating the mean time when the corresponding SPDE for the Eulerian velocity field loses its uniqueness.

(iv) In one of that cases it was found that LE has exactly same expression as given in (3).

(v) For an isotropic turbulence the system was elaborated via introducing longitudinal and normal Stokes numbers.

In physical literature the model (1) most often was used to describe so called inertial particles such as water drops in atmospheric clouds, particulate matter or living organisms in the turbulent upper layer of oceans, and many other phenomena. Undoubtedly, real turbulent flows in the ocean and atmosphere are essentially 3D phenomena. However, the introduction of three dimensional perturbations does not destroy the main features of the cascade picture according to [8], implying that 2D turbulence phenomenology establishes a realistic picture of turbulent fluid flows.

In Eulerian terms Equation (1) cover Lagrangian motion in the Eulerian velocity field satisfying the following equation

By the method of characteristics one can find that for some (maybe short) interval the solution of this equation exists and unique since at the initial moment . However, after some time the uniqueness is lost (the Jacobian vanishes) due to a very weak dissipation modeled by the last term on the left hand side (LHS). Thus, estimates of the mean of the first moment when hits zero would provide us with an idea when (4) loses uniqueness. In terms of the non-linear wave theory, one can treat that as the first moment of wave breaking.

Worth noting that if the dissipation term is replaced by a classical friction , then we arrive at the well known stochastic Burger’s equation which has a unique solution for all t thereby no caustics may occur.

Some of our results can be predicted by simply proceeding to dimensionless variables in (4). Let U and L be some typical velocity and length scales, respectively. Changing to one gets from (4)

where the dimensionless parameter

is called Stokes number.

Thus, if then the underlying Eulerian velocity field satisfies a linear equation and hence the intensity of caustics should tend to zero. In the opposite case the non-linear term dominates and one may expect that the number of caustics per time grows indefinitely.

The paper is organized as follows. A similar one-dimensional problem is exactly solved in Section 1. The solution is essentially used in investigating 2D phenomena. A deterministic case () is briefly discussed in Section 2. In Section 3, we derive a system of equations containing J in the general case of an arbitrary homogeneous forcing. For particular forms of the forcing rigorous estimates for the mean number of caustics are found in Section 4. Furthermore, is computed by solving a simple parabolic equation. The case of an isotropic forcing (unsolved yet) is mentioned in Section 5. Conclusions are gathered in Section 6 and some details are brought to Appendix A.

2. One-Dimensional Case

A part of results from this section is well known from physical literature [4,7,9], presented sometimes in a quite vague fashion. We formulate and prove them rigorously and give more details.

Consider

with and

Introduce the following dimensionless quantity and apply the Ito formula to the last system. As a result we have

Then we proceed to a dimensionless time and obtain

where w is a standard Wiener process and

Worth noting that if the velocity and length scales of the flow are chosen as and , respectively, then (8) coincides with the earlier introduced Stokes number (5).

Assume that zeros of are prime that is typical for stationary processes, then they can be identified with moments of explosion of .

Proposition 1.

Process p is explosive(e.g., [10]), more exactly

where the explosion time S is finite

and its expectation can be explicitly computed

where

are the Airy functions and their modulus.

Explosiveness of follows from the Feller’s criteria [10].

To prove (9) we introduce as the mean time to explosion under condition , then solve

where

is the generator of (7).

For the purpose of studying models the knowledge of the mean explosion time is not enough. Introduce

and let be the same probability under condition , then

In [12], it was shown that satisfies the initial value problem

To ensure uniqueness of solution of (10) we add the natural boundary conditions assuming that the limit exists similarly to .

A simplest Euler scheme was used for solving (10) numerically. Some details and validation of the choice of the scheme parameters are given in Appendix A. Notice that our goal is not to evaluate and minimize the error of the numerical computations, but rather to illustrate that (10) can be solved quite accurately and efficiently with very simple tools.

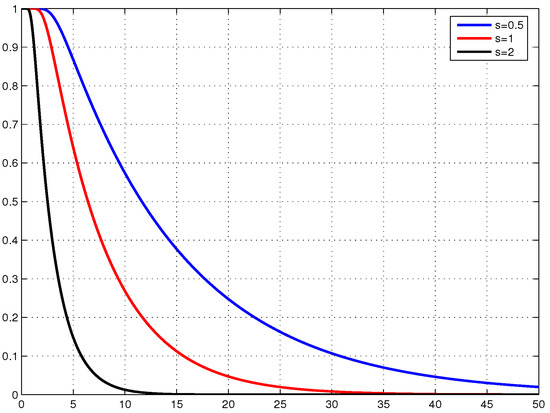

Graphs of for a few values of s are shown in Figure 1

Figure 1.

versus t for .

To proceed to investigating LE we notice that after explosion process can be continued by starting over, i.e., by solving same Equation (7) with the initial condition

The positive sign follows from relation and the fact that zeros of are prime. Thus, takes different signs on different sides of a zero of .

LE for flow (7) is expressible in terms of the ergodic mean of p

as follows from (2) and definition of , see [2] for details. It also can be exactly found

Proposition 2.

The ergodic mean of p is given by

The statement is proven in Appendix A and here we just make some comments. Notice that the density of the stationary distribution of does exist and is given by

where C is a normalized constant.

One can find the following asymptotic

Thus, the integral for the invariant mean

is formally divergent, however if the integral is meant as a Cauchy principal value then it coincides with the RHS of (11).

3. Deterministic 2D Case

In this section, we plug in (1) . The resulting linear equations are easy to solve and get the following expression for the Jacobian

in dimensionless form with Stokes number s defined in (5), where

and , ( are the initial position and velocity, respectively, related by .

Let

and S be the first time when . Easy to find that

where

In particular if and do not depend on at all, then and S, defined for all , does not depend on the initial point as well. Thus, the equation

loses uniqueness exactly at moment . If one defines after as a solution of (13) with the initial condition

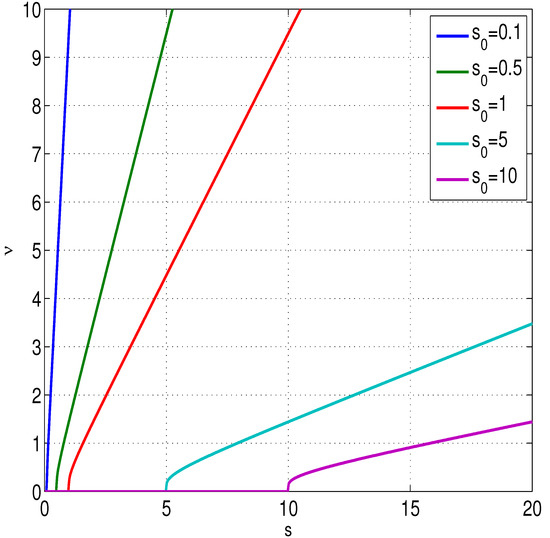

then could be interpreted as the intensity of caustics in time. In Figure 2, we show a few curves for different in order to compare them visually with a stochastic case addressed in the next sections.

Figure 2.

Dependence of the caustic rate on Stokes number s in absence of noise.

If S depends on the initial point, then its interpretation in terms of Eulerian setup (13) is not that simple and will not be discussed here.

4. System of Equations for Jacobian in General 2D Case

Now we return to the stochastic model (1). In a few works it was pointed out that there is a closed equation for the matrix

Namely, e.g., [2,4]

An analysis of that equation led to some general important conclusions, but it is of little help for our purposes because in general it cannot be reduced to efficiently handled scalar equations.

Let us first rewrite (1) in the coordinate-wise form with

where

and are entries of . The goal is to investigate time behavior of the Jacobian

It is not possible to obtain a closed equation for , but it can be included in a system of four equation as it is shown in Appendix A. Namely, for dimensionless time denoted by the same letter, Jacobian can be represented as

where dimensionless random function is included into the following system

s is Stokes number defined similarly to (8) and an exact expression for it is given in Appendix A.

To define processes we nondimensionalize and set

where the subs mean derivatives. Thus, ’s are dependent Wiener (non-standard) processes with a covariance matrix given by -4.6cm0cm

where is a dimensionless version of and partial derivatives are taken at .

5. Two Special Cases

Under certain conditions imposed on the forcing in (14) the first moment S of to hit zero turns out to be the minimum from the first explosion moments for two independent 1D processes described by (7).

In this section, we assume a zero initial velocity field

that implies zero initial conditions in (15)

Model 1. Assume

where are independent and

Next due to the zero initial conditions . Introduce

By adding and subtracting first two equations in (15) we get two separated equations

for independent identically distributed processes and

Model 2. In this model we assume

with independent U and V such that

where the prime means the derivative in the space coordinate. From (16, 17, 21, 22) it follows that

and

are independent identically distributed Wiener processes since and .

Thus, and introducing

arrive at the same equations (20).

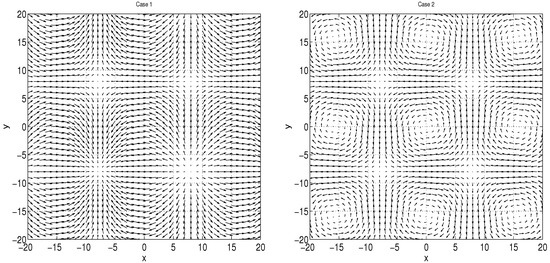

Below we show simulated velocity fields at a particular time moment for both models (Figure 3) where periodic in space forcings were used.

Figure 3.

Snapshots of velocity fields for Model 1 (left) and Model 2 (right).

Let and be the first explosion moments for and , respectively, then

Certainly the knowledge of is not enough to find , but the latter can be expressed in terms of as

Manipulating with this formula it is not difficult to present an example where the expected value of the minimum of two independent identically distributed random variables is finite while the expectation of each variable is infinite due to heavy tails of distribution. So, theoretically speaking and may differ by an order of magnitude. Fortunately it is not the case here since the tail of distribution of is exponential and can be evaluated [13].

Namely from Theorem 1.1 in [13] it follows that the exponential moment

is finite for all satisfying

and

On the other side obviously that

Thus, for the mean number of caustics one gets from (9)

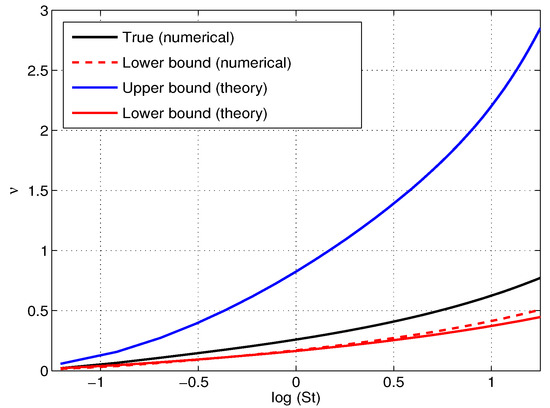

For small s asymptotics of the lower bound and upper bound coincide and we get

while for large s the corresponding asymptotics differ just by a constant

Approximation (25) is quite speculative and indeed it greatly overestimates . It can be seen by comparing the bounds with exact curve obtained from solving the corresponding PDE for (Section 1). The upper and lower bounds for are shown in Figure 4 as well as its numerical version.

Figure 4.

The theoretical upper and lower bounds for the caustic rate as functions of Stokes number s and its numerical version.

In Model 2 LE cannot be found by such simple tools because the equations for x and y components do not split.

6. Isotropic Forcing

Assume that in the original equations the forcing is isotropic, then its covariances are given by [3]

where . Assume smooth longitudinal and normal correlation functions

with . Introduce

Then from (17) it can be derived that (15) takes form

here are independent standard Wiener processes.

No essential progress is made in analyzing this system yet because none of variables can be eliminated. The only reason for presenting it here is a great importance of the isotropic case for applications.

7. Conclusions and Discussion

While one dimensional stochastic models for inertial particles have been comprehensively addressed, refs. [4,6,7,9] no essential progress in analytical studies for turbulence have been reported yet. In this work for the first time the intensity of the caustics was rigorously treated in the framework of two dimensional stochastic flows modeling turbulence in compressible media.

Namely, we revealed two cases, where the mean time to explosion in the particle density, , can be analytically estimated for the full range of Stokes number s and can be accurately evaluated by solving an initial/boundary problem for a one dimensional parabolic equation. Worth noting that both boundaries provide an exact asymptotic as . For both models the reciprocal , interpreted as the intensity of caustics, increases monotonically from zero to infinity that is in full agreement with physics of phenomena in question.

The reported advance in the proposed models is due to reduction in the number of unknowns in the system (15) from four to two. Alas, for the most interesting isotropic case such a reduction is not possible, but a hope for finding asymptotics of still remain. This is the main direction of our future studies.

Another interesting area of further consideration is the Equation (4) describing the Eulerian velocity field generating Lagrangian motion covered by model (1). It should be recognized that the interpretation of and in terms of solutions of (4) is not clear enough except the deterministic case with the initial velocity field for which and do not depend on at all. A natural and important question is how the mean time until the uniqueness loss depends on the initial velocity field.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Proof of Proposition 2

The proof is based on the following statement

Lemma A1.

If there exist real m and smooth bounded function such that

and

then with probability one

The second term on the right hand side goes to zero as due to the large numbers law. The difference on the left hand side (LHS) of (A4) also converges to zero because of the boundness of V and condition (A1). Lemma is proven.

Notice importance of (A1). If then the jumps of V at explosion moments can accumulate leading to a non-zero limit of LHS.

Now we directly construct such a function and determine m.

The integral for M is meant as Cauchy principal value. That allows for changing the order of integration after substitution

Integration in leads to

where

To complete the proof one should account for [11],

This relation also can be derived from the fact that the both sides satisfy the same differential equation and same initial conditions [14].

Finally, notice that the expression for m after changing the order of integration in (A4) turns to the mean of with respect to the invariant measure given in (12)

Proposition 2 is proven.

Appendix A.2. Details of the Computational Algorithm for solving (10)

Let h and be space and time, respectively, a big enough number, the corresponding space/time grid, where . Set . Then a standard Eulerian scheme for (23) is written as

Notice that (A5) is well posed because

The choice of parameters was dictated by standard conditions on ratio and constraints

where is the exact value of the expectation of S found from (9). In particular =8.7735 while under our choice of it was obtained that

A similar comparison for other s can be seen from Figure 4.

Appendix A.3. Derivation of (15)

For the purpose of nondimensionalizing let us redenote the forcing on RHS of (14) by capital letters . Then by differentiating (14) in a and b we get

where

and the covariance matrix of ’s is given by

where is the space covariance matrix of

Introduce

Applying Ito formula we obtain

To proceed to dimensionless variables assume

where are dimensionless Wiener processes, thereby in dimensionless variables

with

Introduce a Stokes number similarly to (8)

The result is

where

We do not need a stochastic equation for since it can be found from the following equation

which follows from

References

- Kunita, H. Stochastic Flows and Stochastic Differential Equations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Piterbarg, L.I. The top Lyapunov exponent for a stochastic flow modeling the upper ocean turbulence. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 2001, 62, 777–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monin, A.S.; Yaglom, A.M. Statistical Fluid Mechanics: Mechanics of Turbulence; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Gustavsson, K.; Mehlig, B. Statistical models for spatial patterns of inertial particles in turbulence. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.4374v1. [Google Scholar]

- Meibohm, J. On the Phase-Space Distribution of Heavy Particles in Turbulence. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Göteborg, Sweden, 3 January 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Falkovich, G.; Musacchio, S.; Piterbarg, L.; Vucelja, M. Inertial particles driven by a telegraph noise. Phys. Rev. E 2007, 76, 026313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horvai, P. Lyapunov exponent for inertial particles in the 2D Kraichnan model as a problem of Anderson localization with complex valued potential. arXiv 2005, arXiv:nlin/0511023. [Google Scholar]

- Boffetta, G.; Ecke, R.E. Two-dimensional turbulence. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 2012, 44, 427–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehlig, B.; Wilkinson, M. Coagulation by random velocity fields as a Kramers problem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 250602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karatzas, I.; Shreve, S.E. Brownian Motion and Stochastic Calculus; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Halperin, B.I. Green’s functions for a particle in a one-dimensional random potential. Phys. Rev. 1965, 139, A104–A117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatzas, I.I.; Shreve, S.E. Distribution of the time to explosion for one-dimensional diffusions. Probab. Theory Relat. Fields 2016, 164, 1027–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loukianov, O.; Loukianova, D.; Song, S. Spectral gaps and exponential integrability of hitting times for linear diffusions. Ann. Inst. Henri Poincaré Probab. Statist. 2011, 47, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. Handbook of Mathematical Functions; Dover Publications, INC.: New York, NY, USA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).