Abstract

We define a process calculus to describe multi-agent systems with timeouts for communication and mobility able to handle knowledge. The knowledge of an agent is represented as sets of trees whose nodes carry information; it is used to decide the interactions with other agents. The evolution of the system with exchanges of knowledge between agents is presented by the operational semantics, capturing the concurrent executions by a multiset of actions in a labelled transition system. Several results concerning the relationship between the agents and their knowledge are presented. We introduce and study some specific behavioural equivalences in multi-agent systems, including a knowledge equivalence able to distinguish two systems based on the interaction of the agents with their local knowledge.

1. Introduction

Process calculi are used to describe concurrent systems, providing a high-level description of interactions, communications and synchronizations between independent processes or agents. The main features of a process calculus are: (i) interactions between agents/processes are by communication (message-passing), rather than modifying shared variables; (ii) large systems are described in a compositional way by using a small number of primitives and operators; (iii) processes can be manipulated by using equational reasoning and behavioural equivalences. The key primitive distinguishing the process calculi from other models of computation is the parallel composition. The compositionality offered by the parallel composition can help to describe large systems in a modular way, and to better organize their knowledge (for reasoning about them).

In this paper we define an extension of the process calculus TiMo [1] in order to model multi-agent systems and their knowledge. In this framework, the agents can move between locations and exchange information, having explicit timeouts for both migration and communication. Additionally, they have a knowledge of the network used to decide the next interactions with other agents. The knowledge of the agents is inspired by a model of semi-structured data [2] in which it is given by sets of unordered trees containing pairs of labels and values in each node. In our approach, the knowledge is described via sets of trees used to exchange information among agents about migration and communication. Overall, we present a formal way to describe the behaviour of mobile communicating agents and networks of agents in a compositional manner.

A network of mobile agents is a distributed environment composed of locations where several agents act in parallel. Each agent is represented by a process together with its knowledge that is used to decide interactions with other agents. Taking the advantage that there already exists a theory of parallel and concurrent systems, we define a prototyping language for multi-agent systems presented as a process calculus in concurrency theory. Its semantics is given formally by a labelled transition system; in this way we describe the behaviour of the entire network, and prove some useful properties.

In concurrency, the behavioural equality of two systems is captured by using bisimulations. Bisimulations are important contributions to computer science that appeared as refinements of ‘structure-preserving’ mappings (morphisms) in mathematics; they can be applied to new fields of study, including multi-agent systems. Bisimilarity is the finest behavioural equivalence; it abstracts from certain details of the systems, focusing only on the studied aspects. The equivalence relations should be compositional such that if two systems are equivalent, then the systems obtained by their compositions with a third system should also be equivalent. This compositional reasoning allows for the development of complex systems in which each component can be replaced by an equivalent one. Furthermore, there exist efficient algorithms for bisimilarity checking and compositionality properties of bisimilarity, algorithms that are usually used to minimize the state-space of systems. These are good reasons why we consider that it is important to define and study some specific behavioural equivalences for multi-agent systems enhanced with a knowledge of the network for deciding the next interactions. To be more realistic, we consider systems of agents with timing constraints on migration and communication. Therefore, a notable advantage of using our framework to model systems of mobile agents is the possibility to naturally express compositionality, mobility, local communication, timeouts, knowledge, and equivalences between systems in a given interval of time (up to a timeout).

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the syntax and semantics of the new process calculus knowTiMo and provides some results regarding the timing and knowledge aspects of the evolution. In Section 3 we define and study various bisimulations for the multi-agent systems described in knowTiMo . The conclusion, related work and references end the article.

2. The New Process Calculus knowTiMo

In order to model the evolution of multi-agent systems handling knowledge, timed communication and timed migration, we define a process calculus named knowTiMo, where know stands for ‘knowledge’ and TiMo stands for the family of calculi introduced in [1] and developed in several articles.

In Table 1 we present the syntax of knowTiMo, where:

Table 1.

Syntax of our Multi-Agent Systems.

- Loc is a set of distributed locations or location variables, Chan= is a set of channels used for communication among agents, Id is a set of names used to denote recursive processes, and is a set of networks;

- a unique process definition is available for all ;

- timeouts of actions are denoted by ; thresholds appearing in tests are denoted by ; variables are denoted by u; expressions (over values, variables and allowed operations) are denoted by v; fields are denoted by f; path of fields are denoted by p and are used to retrieve/update the value of the fields. Also, if and is a process definition, then for we obtain two different process instances and .

An agent A is a pair , where A behaves as prescribed by P and K is the knowledge used by process P during its execution. An agent is ready to migrate from its current location to the location l by consuming the action of agent A. In , the timer t indicates the fact that agent A is unavailable for t units of time at the current location; then, once the timer t expires, executes process P at the new location l. Since l can be a location variable, it may be instantiated after communication between agents. The use of location variables allows agents to adapt their behaviours based on the interactions among agents.

An agent is available for up-to t units of time to communicate on channel a the value v to another agent available for communication at the same location and awaiting for a value on the same communication channel a. In order to simplify the presentation in this paper, we consider a synchronous calculus; this means that when a communication takes place, the message sent by one process is instantly received by the other process. If the communication happens, then agent A executes process P, while agent executes process by making use of the received value v. If the timers t and of the agents A and expire, then they execute processes Q and , respectively.

An agent uses its knowledge K to check the truth value of the test. If the value is true, then agent A executes process P, while if the value is false, then agent A executes process Q.

The agent then extends its knowledge K by adding the new piece of knowledge in parallel with K, and then executes process P. The agent then updates its knowledge K by adding the value v into the field identified by f reached following path , and then executes process P; if the field f does not exist, then the field is created and the value v is assigned to it. The agent has no actions to execute, and its evolution terminates.

The knowledge K of an agent A is used either for storing information needed for communication with other agents or for deciding what process to execute. We define the knowledge as sets of trees in which the nodes carrying the information are of two types: and . Both types of nodes contain a field f and a knowledge ; they differ only in the value stored in the field f, which can be either the symbol indicating the empty value, or a non-empty value v. An agent can use the information stored in its knowledge K to perform tests. For example, a test is only if, following a path p in knowledge K, the value stored in the field f is greater than k (otherwise, it is evaluated to ); a path is used to select a node in knowledge K. Predicates, always embedded in square brackets and attached to fields in a path, are used to analyze either the value of the current node by using or the values of the inner nodes by using . We say that a knowledge K is included in another knowledge (denoted ) if for all paths p appearing in K it holds that .

In Table 1 there exist only one possibility to bind variables; namely, the variable u of the process is bound within process P, while it is not bound within process Q. We denote by and the sets of free variables appearing in process P and network N, respectively. Moreover, we impose that , where . We denote by the process P having all the free occurrences of the variable u replaced by value v, possibly after using -conversion to avoid name clashes in process P.

A network is composed of distributed locations, where denotes a location l containing a set of agents, while denotes a location without any agents. Over the set of networks we define the structural equivalence ≡ as the smallest congruence satisfying the equalities:

The structural congruence ≡ is needed when using the operational semantics presented in Table 2 and Table 3 for either executing actions or indicating time passing. In Table 2 the relation denotes the transformation of a network N into a network by executing the actions from the multiset of actions ; if the multiset of actions contains only a single action , namely , then we use instead of .

Table 2.

Operational Semantics for our Multi-Agent Systems.

Table 3.

Operational Semantics of knowTiMo: Time Passing.

The operational semantics of knowTiMo is presented in Table 2.

In rule (Stop), denotes a network without agents, and thus marks the fact that no action is available for execution. Rule (Com) is used if at location l two agents and can communicate successfully over channel a. After communication, both agents remain at the current location l with their knowledge unchanged; agent executes , while agent executes . The successful communication over channel a at location l is marked by label .

Rules (Put0) and (Get0) are used for an agent (where ) to remove action a when its timer expires. Afterwards, agent A is ready to execute Q. Knowledge K remains unchanged. Since rule (Com) can be applied even if and are zero, it follows that when a timer is 0, only one of the rules (Com), (Put0) and (Get0) is chosen for application in a nondeterministic manner.

Rule (Move0) is used when at location l an agent migrates to location to execute process P. Rules (IfT) and (IfF) are used when an agent should decide what process to execute (P or Q) based on the Boolean value returned by ; this value is determined by performing the test on the knowledge K of agent A. Notice that in order to perform a test, the agent A can only read its knowledge K.

Rule (Create) is used when an agent extends its knowledge K with ; afterwards, the agent A executes process P.

Rule (Update) is used when an agent updates to v the value of of the existing field f, while rule (Extend) is used when the agent expands (at the end of) an existing path p with a field f such that ; afterwards the agent A executes process P.

Rule (Call) is used when an agent is ready to unfold the process into . Rule (Par) is used to put together the behaviour of smaller subnetworks. while rule (Equiv) is used to apply the structures congruence over networks.

In Table 3 are presented the rules for describing time passing, while the knowledge of the involved agents remains unchanged. The relation indicates the transformation of a network N into a network after t units of time.

In rule (Stop), denotes a network without agents; the passing of time does not affect such a network. Rules (DPut), (DGet) and (DMove) are used to decrease the timers of actions, while rules (DPar) is used to put together the behaviour of composed networks. In rule (DPar), denotes a network that cannot execute any action; this is possible because the use of negative premises in our operational semantics does not lead to inconsistencies.

Given a finite multiset of actions and a timeout t, a derivation captures a complete computational step of the form:

The fact that a knowTiMo network N is able to perform zero or more actions steps and a time step in order to reach a network is denoted by . Notice that the consumed actions and elapsed time are not recorded. By we denote the fact that there exist networks and such that ; in this way we emphasize only the consumed action out of all consumed actions.

In our setting, at most one time passing rule can be applied for any arbitrary given process. This is the reason why, by inverting a rule, we can describe how the time passes in the subprocesses of a process. This result is useful when reasoning by induction on the structure of processes for which time passes.

Proposition 1.

Assume . Then exactly one of the following holds:

- and ;

- and , where ;

- and , where ;

- and , where ;

- such that , and there exist and such that , and .

Proof.

The following theorem claims that time passing does not introduce nondeterminism in the evolution of a network.

Theorem 1.

The next two statements hold for any three networks N, and :

- 1.

- if , then ;

- 2.

- if and , then .

Proof.

- 1.

- We proceed by induction on the structure of N.

- Case . Since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that , meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that , meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that , meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that , meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that there exist and such that , together with and . By induction the reductions and imply that and , respectively. Thus , meaning that (as desired).

- 2.

- We proceed by induction on the structure of N.

- Case . Since and , by using Proposition 1, it holds that and , respectively, meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since and , by using Proposition 1, it holds that and , respectively, meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since and , by using Proposition 1, it holds that and , respectively, meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since and , by using Proposition 1, it holds that and , respectively, meaning that (as desired).

- Case . Since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that there exist and such that , together with and . Similarly, since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that there exist and such that , together with and . By induction, and imply that , while and imply that . Thus, , meaning that (as desired). □

The following theorem claims that whenever only the rules of Table 3 can be applied for two time steps of lengths t and , then the rules can be applied also for a time step of length .

Theorem 2.

If , then .

Proof.

We proceed by induction on the structure of N.

- Case . Since by using Proposition 1, it holds that . Similarly, since by using Proposition 1, it holds that . Rule (DStop) can be used for network N, namely N (as desired).

- Case . Since by using Proposition 1, it holds that , where . Similarly, since by using Proposition 1, it holds that , where . Due to the fact that , rule (DGet) can be used for network N, namely (as desired).

- Case . Since by using Proposition 1, it holds that , with . Similarly, since by using Proposition 1, it holds that , where . Due to the fact that , rule (DPut) can be used for network N, namely (as desired).

- Case . Since by using Proposition 1, it holds that , where . Similarly, since by using Proposition 1, it holds that , where . Due to the fact that , rule (DMove) can be used for network N, namely (as desired).

- Case . Since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that and there exist and such that , together with and . Similarly, since , by using Proposition 1, it holds that there exist and such that , together with and . By induction, and imply that , while and imply that . Since , and , rule (DPar) can be used for network N, namely (as desired).

Regarding the knowledge of an agent, we have the following result showing that any given agent can be obtained starting from an agent without any knowledge.

Proposition 2.

If with , then

there exists with such that .

Proof.

We proceed by induction on the structure of .

- Consider . According to rule (Create), this knowledge can be obtain from a process . This implies that for with , it holds that (as desired).

- Consider , with . By induction, there exists a process P able to create the knowledge K. This implies that for with , it holds that . According to rule (Create), knowledge can be obtain starting from knowledge K by using a process . This implies that for with , it holds that (as desired).

- Consider . By induction, there exists a process P able to create the knowledge . This implies that for with , it holds that . According to rule (Extend), knowledge can be obtain starting from knowledge K by using a process , where . This implies that for with , it holds that (as desired). □

The next result is a consequence of the previous one; it claims that any given network in knowTiMo can be obtained starting from a network containing only agents without knowledge.

Theorem 3.

If , then there exists with (, ) such that .

The following example illustrates how agents communicate and make use of their knowledge.

Example 1.

To illustrate how multi-agent systems can be described in knowTiMo, we adapt the travel agency example from [3], where all the involved agents have a cyclic behaviour. Consider a travel agency with seven offices (one central and six locals) and five employees (two executives and three travel agents). As the agency is understaffed and all local offices need to be used from time to time, the executives meet with the agents daily at the central office in order to assign them local offices where they sell travel packages by interacting with potential customers. We consider two customers that are willing to visit the local offices closer to their homes. In what follows we show how each of the involved agents can be described by using the knowTiMo syntax.

Each day, agent executes the action in order to move after 10 time units from location to the central . After reaching the central office, in order to find out at which local office will work for the rest of the day, it executes the action to try to communicate with any of the executives in the next 5 time units. The location variable newloc is needed to model a dynamic evolution based on the local office assigned by an available executive. After successfully communicating with an executive, the agent moves to location after 5 time units in order to communicate with potential customers using channel in order to sell a travel package towards location at the cost of 100 monetary units. After each working day, the agent returns home by executing the action . The agents and behave similarly to , except that they begin and end their days at different locations, work locally at different offices and the travel packages they advertise are different.

Formally, the travel agents are described by the recursive processes :

.

The identifiers () are uniquely assigned to the three travel agents, and () indicate the six local offices.

Given the knowledge defined above, we exemplify how it can be used for some queries:

- is used to retrieve the price value by following the path in ;

- returns the local office in which the agent is trying to sell its travel package whenever the price of the package available by following the path is below 200 monetary units.

Executives and are placed in the central , being available for communication on channel b for 5 time minutes. In this way, they can assign to the travel agents (in a cyclic manner) the locations , , , and the locations , , , respectively. Formally, the executives are described by :

∅.

The identifiers (with ) are uniquely assigned to the two executives, while (with ) indicate the local offices that each executive can assign to travel agents. Defining the index of the local offices in this way ensures that the executives assign the existing local offices in a cyclic way.

The client initially resides at location ; being interested in a travel package, client is willing to visit the local offices closer to his location, namely , , and . For each of these three local offices, the visit has two possible outcomes: if client interacts with an agent then it will acquire a travel offer, while if the highoffice is closed then client moves to the next local office from its itinerary. Once its journey through the three local offices ends, client returns home whenever was unable to collect any travel offer, while goes at the destination for which he has to pay the lowest amount whenever got at least one offer. After the holiday period ends, client returns home, where can restart the process of searching for a holiday destination. Client behaves in a similar manner as client does, except looking for the most expensive travel package while visiting the local offices , and . Formally, the clients are described by :

ε)

ε)

,

ε)

ε)

,

ε)

ε)

,

εε

εε

εε.

The identifiers (with ) are uniquely assigned to the two clients, the identifiers uniquely identify the possible destinations the clients can visit, while (with ) are used to identify the local offices for each of the clients.

The tests used above are:

ε),

The initial state of the system given as the knowTiMo network N is:

,

where stands for:

.

In what follows we show how some of the rules of Table 2 and Table 3 are applied such that network N evolves. Since the network N is defined by means of recursive processes, in order to execute their actions we need to use the rules(Call)and(Par)for unfolding, namely

(Call), (Par)

.

The next step is represented by the two updates performed by the executives; thus, the rules(Extend)and(Par)are applied several times. Since the existing knowledge of the two executives is currently ∅, this means that these updates extend in fact their knowledge.

(Extend),(Par)

.

Since the rules of Table 2 are not applicable to the above network, then only time passing can be applied by using the rules of Table 3. The rules(DMove),(DGet)and(DPar)can be applied for , namely the maximum time units that can be performed.

(DMove),(DGet),(DPar)

.

Since after 5 time units of the evolution there are no agents to communicate with the executives on channel b, then the rules(Put0)and(Par)are applied such that the else branches of the two executives are chosen to be executed next.

(Put0), (Par)

.

Note that the evolution was deterministic during the first 5 time units. However, since there are two executives and three travel agents into the system, the communication on channel b will take place in a nondeterministic manner, and thus there exists several possible future evolutions of the system.

3. Behavioural Equivalences in knowTiMo

In what follows, we define and study bisimulations for multi-agent systems that consider knowledge dynamics as well as explicit time constraints for communication and migration. Since a bisimilarity is the union of all bisimulations of the same type, in order to demonstrate that two knowTiMo networks and are bisimilar it is enough to discover a bisimulation relation containing the pair . This standard bisimulation proof method is interesting for the following reasons:

- check-ups are local (only immediate transitions are used);

- No hierarchy exists between the pairs of a bisimulation, and thus we can effectively use bisimilarity to reason about infinite behaviours; this makes it different from inductive techniques, where we can reason about finite behaviour due to the required hierarchy.

3.1. Strong Timed Equivalences

Inspired by the approach taken in [4], we extend the standard notion of strong bisimilarity by allowing also timed transitions to be taken into account.

Definition 1

(Strong timed bisimulation).

Let be a symmetric binary relation over knowTiMo networks.

- 1.

- is a strong timed bisimulation if

- and implies that there exists such that and ;

- and implies that there exists such that and .

- 2.

- The strong timed bisimilarity is the union ∼ of all strong timed bisimulations .

Definition 1 treats in a similar manner the timed transitions and the labelled transitions, and so the bisimilarity notion is similar to the bisimilarity notion originally given for labelled transition systems. We can prove that the relation ∼ is the largest strong timed bisimulation, and also an equivalence relation.

Proposition 3.

- 1.

- Identity, inverse, composition and union of strong timed bisimulations are strong timed bisimulations.

- 2.

- ∼ is the largest strong timed bisimulation.

- 3.

- ∼ is an equivalence.

Proof.

- 1.

- We treat each relations separately showing that it respects the conditions from Definition 1 for being a strong timed bisimulation.

- (a)

- The identity relation is a strong timed bisimulation.

- Assume . Consider ; then .

- Assume . Consider N; then .

- (b)

- The inverse of a strong timed bisimulation is a strong timed bisimulation.

- Assume , namely . Consider ; then for some we have and , namely . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- Assume , namely . Consider ; then for some we have and , namely . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- (c)

- The composition of strong timed bisimulations is a strong timed bisimulation.

- Assume . Then for some N we have and . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Also, since we have for some that and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- Assume . Then for some N we have and . Consider ; then for some , since , we have N and . Also, since we have for some that and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- (d)

- The union of strong timed bisimulations is a strong timed bisimulation.

- Assume . Then for some we have . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and , namely .

- Assume . Then for some we have . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and , namely .

- 2.

- By the previous case (the union part), ∼ is a strong timed bisimulation and includes any other strong timed bisimulation.

- 3.

- Proving that relation ∼ is an equivalence requires proving that it satisfies reflexivity, symmetry and transitivity. We consider each of them in the following:

- (a)

- Reflexivity: For any network N, results from the fact that the identity relation is a strong timed bisimulation.

- (b)

- Symmetry: If , then for some strong timed bisimulation . Hence , and so because the inverse relation is a strong timed bisimulation.

- (c)

- Transitivity: If and then and for some strong timed bisimulations and . Thus, , and so due to the fact that the composition relation is a strong timed bisimulation.

□

The next result claims that the strong timed equivalence ∼ among processes is preserved even if the local knowledge of the agents is expanded. This is consistent with the fact that the processes affect the same portion of their knowledge. To simplify the presentation, in what follows we assume the notations and .

Proposition 4.

If for , , then

Proof.

We show that is a strong timed bisimulation, where:

The proof is by induction on the last performed step:

- Let us assume that . Depending on the value of , there are several cases:

- -

- Consider . Then there exists and such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists , where , such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists , where , such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , then also , and clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , then also , and clearly .

- Let us assume that . Then there exists , , such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

The symmetric cases follow by similar arguments. □

The following result shows that strong timed bisimulation is preserved even after complete computational steps of two knowTiMo networks.

Proposition 5.

Let be two knowTiMo networks.

If and , then there exists such that and .

Proof.

Assuming that the finite multiset of actions contains the labels , then the complete computational step can be detailed as . Since and , then according to Definition 1 there exists such that and . The same reasoning can be applied for another k steps, meaning that there exist such that and . By the definition of a complete computational step, it holds that can be written as . Thus, we obtained that there exists such that and (as desired). □

The next example illustrates that the relation ∼ is able to distinguish between agents with different knowledge if operations are performed.

Example 2.

Consider that client is at location , ready to communicate on channel . To simplify the presentation, we take only a simplified definition of as follows:

ε).

Consider the following three networks in knowTiMo:

,

,

,

where the knowledge of the agents is defined as:

εε,

εε,

.

According to Definition 1, it holds that , while and . This is due to the fact that while all three networks are able to perform a time step of length 4 and to choose the branch, only network is able to perform the operation. Formally:

and

3.2. Strong Bounded Timed Equivalences

We provide some notations used in the rest of the paper:

- A timed relation over the set of networks is any relation .

- The identity timed relation is

- The inverse of a timed relation is

- The composition of timed relations and is

- If is a timed relation and , thenis ’s t-projection. We also denote .

- A timed relation is a timed equivalence if is an equivalence relation, and is an equivalence up-to time if is an equivalence relation.

The equivalence ∼ requires an exact match of transitions of two networks during their entire evolutions. Sometimes this requirement is too strong. In many situations this requirement is relaxed [5], and real-time systems are allowed to behave in an expected way up to a certain amount t of time units. This impels one to define bounded timed equivalences up-to a given time t.

Definition 2

(Strong bounded timed bisimulation).

Let be a symmetric timed relation on and on networks in knowTiMo.

- 1.

- is a strong bounded timed bisimulation if

- and implies that there exists such that and ;

- and implies that there exists such that and .

- 2.

- The strong bounded timed bisimilarity is the union ≃ of all strong bounded timed bisimulations .

The following results illustrate some properties of the strong bounded timed bisimulations. In particular, we prove that the equivalence relation ≃ (that is strictly included in relation ∼) is the largest strong bounded timed bisimulation.

Proposition 6.

- 1.

- Identity, inverse, composition and union of strong bounded timed bisimulations are strong bounded timed bisimulations.

- 2.

- ≃ is the largest strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- 3.

- ≃ is a timed equivalence.

- 4.

- .

Proof.

- 1.

- We treat each relations separately showing that it respects the conditions from Definition 2 for being a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- (a)

- The identity relation is a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- Assume . Consider ; then .

- Assume . Consider N; then .

- (b)

- The inverse of a strong bounded timed bisimulation is a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- Assume , namely . Consider ; then for some we have and , namely . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- Assume , namely . Consider ; then for some we have and , namely . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- (c)

- The composition of strong bounded timed bisimulations is a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- Assume . Then for some N we have and . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Also, since we have for some that and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- Assume . Then for some N we have and . Consider ; then for some , since , we have N and . Also, since , for some we have and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- (d)

- The union of strong bounded timed bisimulations is a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- Assume . Then for some we have that . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and , namely .

- Assume . Then for some we have that . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and , namely .

- 2.

- By the previous case (the union part), ≃ is a strong bounded timed bisimulation and includes any other strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- 3.

- Proving that relation ≃ is a timed equivalence requires proving that it satisfies reflexivity, symmetry and transitivity. We consider each of them in what follows:

- (a)

- Reflexivity: For any network N, results from the fact that the identity relation is a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- (b)

- Symmetry: If , then for some strong bounded timed bisimulation . Hence , and so because the inverse relation is a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- (c)

- Transitivity: If and then and for some strong bounded timed bisimulations and . Thus, it holds that , and so due to the fact that the composition relation is a strong bounded timed bisimulation.

- 4.

- We provide Example 3 below that illustrates the strict inclusion. □

The next result claims that strong bounded timed equivalence over processes is preserved even if the local knowledge of the agents is expanded. This is consistent with the fact that the processes affect the same portion of their knowledge.

Proposition 7.

If , for , , then

Proof.

We show that is a strong bounded timed bisimulation, where:

The proof is by induction on the last performed step:

- Let us assume that . Depending on the value of , there are several cases:

- -

- Consider . Then there exists and such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists , where , such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists , where , such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , then also , and clearly .

- -

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , then also , and clearly .

- Let us assume that . Then there exists , , such that . Then there exists such that . Since , clearly .

The symmetric cases follow by similar arguments. □

The following result shows that strong bounded timed bisimulation is preserved even after complete computational steps of two networks in knowTiMo.

Proposition 8.

Let be two knowTiMo networks.

If and , then there is such that and .

Proof.

Assuming that the finite multiset of actions contains the labels , then the complete computational step can be detailed as . Note that means that . Since and , then according to Definition 2 there exists such that and . The same reasoning can be applied for another k steps, meaning that there exist such that and , namely . The definition of a complete computational step implies that can be written as . Thus, we obtained that there exists such that and (as desired). □

Strong bounded timed bisimulation satisfies the property that if two networks are equivalent up-to a certain deadline t, they are equivalent up-to any deadline before t, i.e., .

Proposition 9.

If and , then .

Proof.

Assume and that there exist the networks , the set of actions and the timers such that and also . According to Proposition 8, there exist the networks such that , and also , …, . Since , then there exists an and a such that . By using Theorem 1, it holds that there exists such that . In a similar manner, by using Theorem 1, it holds that there exists such that . Since and can perform only time passing steps of length at most , this means that , However, according to Definition 2, this means that we obtain the desired relation because the networks N and can match their behaviour for steps. □

The next example illustrates that the relation is able to treat as bisimilar some multi-agent systems that are not bisimilar using the relation ∼.

Example 3.

Let us consider the networks of Example 2, namely:

,

,

,

where the knowledge of the agents is defined as:

εε,

εε,

.

Even if it holds that while and , by applying Definition 2, it results that , and are strong bounded timed bisimilar before the time unit since they have the same evolutions during this deadline, namely , and . If , we have that , while and . Thus, both Definitions 1 and 2 return the same relations among , and for .

This example illustrates also the strict inclusion relation from item 4 of Proposition 6.

3.3. Weak Knowledge Equivalences

Both equivalence relations ∼ and ≃ require an exact match of transitions and time steps of two networks in knowTiMo; this makes them too restrictive. We can introduce a weaker version of network equivalence by looking only at the steps that affect the knowledge data, namely the and steps. Thus, we introduce a knowledge equivalence in order to distinguish between networks based on the interaction of the agents with their local knowledge: the networks are equivalent if we observe only and actions along same paths, regardless of the values added to the knowledge.

Definition 3

(Weak knowledge bisimulation).

Let be a symmetric binary relation over networks in knowTiMo.

- 1.

- is a weak knowledge bisimulation if

- and implies that there exists such that and ;

- and implies that there exists such that and ;

- 2.

- The weak knowledge bisimilarity is the union ≅ of all weak knowledge bisimulations .

The following results present some properties of the weak knowledge bisimulations. In particular, we prove that the equivalence relation ≅ (that is strictly included in relation ∼) is the largest weak knowledge bisimulation.

Proposition 10.

- 1.

- Identity, inverse, composition and union of weak knowledge bisimulations are weak knowledge bisimulations.

- 2.

- ≅ is the largest weak knowledge bisimulation.

- 3.

- ≅ is an equivalence.

- 4.

- .

Proof.

- 1.

- We treat each relation separately showing that it respects the conditions from Definition 3 for being a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- (a)

- The identity relation is a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- Assume . Consider ; then .

- Assume . Consider ; then .

- (b)

- The inverse of a weak knowledge bisimulation is a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- Assume , namely . Consider ; then for some we have and , namely . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- Assume , namely . Consider ; then for some we have and , namely . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- (c)

- The composition of weak knowledge bisimulations is a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- Assume . Then for some N we have and . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Also, since we have for some that and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- Assume . Then for some N we have and . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Also, since we have for some that and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and .

- (d)

- The union of weak knowledge bisimulations is a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- Assume . Then for some we have . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and , namely .

- Assume . Then for some we have . Consider ; then for some , since , we have and . Thus, . By similar reasoning, if then we can find such that and , namely .

- 2.

- By the previous case (the union part), ≅ is a weak knowledge bisimulation and includes any other weak knowledge bisimulation.

- 3.

- Proving that relation ≅ is an equivalence requires proving that it satisfies reflexivity, symmetry and transitivity. We consider each of them in what follows:

- (a)

- Reflexivity: For any network N, results from the fact that the identity relation is a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- (b)

- Symmetry: If , then for some weak knowledge bisimulation . Hence , and so because the inverse relation is a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- (c)

- Transitivity: If and then and for some weak knowledge bisimulations and . Thus, , and so due to the fact that the composition relation is a weak knowledge bisimulation.

- 4.

- We provide Example 4 below illustrating the strict inclusion. □

The next result claims that weak knowledge equivalence ≅ among processes is preserved even if the local knowledge of the agents is expanded. This is consistent with the fact that the processes affect the same portion of their knowledge.

Proposition 11.

If , for , , then

Proof.

We show that is a weak knowledge bisimulation, where:

The proof is by induction on the last performed step. Let us assume that

. Depending on the value of , there are several cases:

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , then also , and clearly .

- Consider . Then there exists such that . Then there exists such that . Since , then also , and clearly .

The symmetric cases follow by similar arguments. □

The following result shows that weak knowledge bisimulation is preserved after complete computational steps of two networks in knowTiMo only if the knowledge is modified at least once during such a step.

Proposition 12.

Let be two knowTiMo networks and or .

If and , then there exists such that and .

Proof.

Assuming that the finite multiset of actions contains the labels that denote modifications to the knowledge, then the complete computational step can be detailed as . Since and , then according to Definition 3 there exists such that and . The same reasoning can be applied for another k times, meaning that there exist such that and . By the definition of a complete computational step, it holds that can be written as . Thus, we obtained that there exists such that and (as desired). □

The next example illustrates that the relation ≅ is able to treat bisimilar systems that are not bisimilar using the relation ∼.

Example 4.

Consider the network of Example 2, and a network

,

in which the client can perform only an action:

.

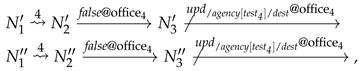

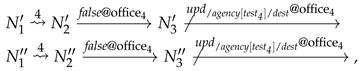

According to Definition 1, it holds that . This is due to the fact that the network can perform a time step of length 4 and choose the branch, while the network can perform only the operation. Formally:

and

The above reductions can also be written as

,

and

.

By applying Definition 3, it results that and are weak knowledge bisimilar because they are able to perform an update on the same path at the same location, i.e., .

This example is also an illustration of the strict inclusion relation from item 4 of Proposition 10.

4. Conclusions and Related Work

In multi-agent systems, knowledge is usually treated by using epistemic logics [6]; in particular, the multi-agent epistemic logic [7,8]. These epistemic logics are modal logics describing different types of knowledge, being different not only syntactically, but also in expressiveness and complexity. Essentially, they are based on two concepts: Kripke structures (to model their semantics) and logic formulas (to represent the knowledge of the agents).

The initial version of TiMo presented in [1] leads to some extensions: with access permissions in perTiMo [9], with real-time in rTiMo [10], combining TiMo and the bigraphs [11] to obtain the BigTiMo calculus [12]. However, in all these approaches an implicit knowledge is used inside the processes. In this article we defined knowTiMo to describe multi-agent systems operating according to their accumulated knowledge. Essentially, the agents get an explicit representation of the knowledge about the other agents of a distributed network in order to decide their next interactions. The knowledge is defined as sets of trees whose nodes contain pairs of labels and values; this tree representation is similar to the data representation in Petri nets with structured data [13] and Xd process calculus [14]. The network dynamics involving exchanges of knowledge between agents is presented by the operational semantics of this process calculus; its labelled transition system is able to capture the concurrent execution by using a multiset of actions. We proved that time passing in such a multi-agent system does not introduce any nondeterminism in the evolution of a network, and that the progression of the network is smooth (there are no time gaps). Several results are devoted to the relationship between the evolution of the agents and their knowledge.

According to [15], the notion of bisimulation was independently discovered in computer science [16,17], modal logic [18] and set theory [19,20]. Bisimulation is currently used in several domains: to test the behavioural equality of processes in concurrency [21]; to solve the state-explosion problem in model checking [22]; to index and compress semi-structured data in databases [23,24]; to solve Markov decision processes efficiently in stochastic planning [25]; to understand for some languages their expressiveness in description logics [26]; and to study the observational indistinguishability and computational complexity on data graphs in XPath (a language extending modal logic with equality tests for data) [27]. It is worth noting that the notion of bisimulation is related to the modal equivalence in various logics of knowledge and structures presented in [28]. In some of these logics it is proved that certain forms of bisimulation correspond to modal equivalence of knowledge, and this is used to compare the logics expressivity [29,30].

Inspired by the bisimulation notion defined in computer science, in this paper we defined and studied some specific behavioural equivalences involving the network knowledge and timing constraints on communication and migration; the defined behavioural equivalences are preserved during complete computational steps of two multi-agent systems. Strong timed bisimulation takes also into account timed transitions, being able to distinguish between different systems regardless of the evolution time; strong bounded timed bisimulation imposes limits for the evolution time, including the equivalences up to any bound below that deadline. A knowledge equivalence is able to distinguish between systems based on the interaction of the agents with their local knowledge. In the literature, a related but weaker/simpler approach of knowledge bisimulation appeared in [14], where the authors used only barbs (not equivalences), looking only at the steps.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors contributed equally to this work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- Ciobanu, G.; Koutny, M. Modelling and Verification of Timed Interaction and Migration. In Proceedings of the Fundamental Approaches to Software Engineering, 11th International Conference, FASE 2008, Held as Part of the Joint European Conferences on Theory and Practice of Software, ETAPS 2008, Budapest, Hungary, 29 March–6 April 2008; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Fiadeiro, J.L., Inverardi, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 4961, pp. 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abiteboul, S.; Buneman, P.; Suciu, D. Data on the Web: From Relations to Semistructured Data and XML; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, B.; Ciobanu, G. Verification of distributed systems involving bounded-time migration. Int. J. Crit.-Comput.-Based Syst. 2017, 7, 279–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, G. Behaviour Equivalences in Timed Distributed pi-Calculus. In Software-Intensive Systems and New Computing Paradigms—Challenges and Visions; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Wirsing, M., Banâtre, J., Hölzl, M.M., Rauschmayer, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5380, pp. 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posse, E.; Dingel, J. Theory and Implementation of a Real-Time Extension to the pi-Calculus. In Proceedings of the Formal Techniques for Distributed Systems, Joint 12th IFIP WG 6.1 International Conference, FMOODS 2010 and 30th IFIP WG 6.1 International Conference, FORTE 2010, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 7–9 June 2010; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Hatcliff, J., Zucca, E., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010; Volume 6117, pp. 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hintikka, J. Knowledge and Belief. An Introduction to the Logic of the Two Notions; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Fagin, R.; Halpern, J.Y. Belief, Awareness, and Limited Reasoning. Artif. Intell. 1987, 34, 39–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modica, S.; Rustichini, A. Awareness and partitional information structures. Theory Decis. 1994, 37, 107–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciobanu, G.; Koutny, M. Timed Migration and Interaction with Access Permissions. In Proceedings of the FM 2011: Formal Methods—17th International Symposium on Formal Methods, Limerick, Ireland, 20–24 June 2011; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Butler, M.J., Schulte, W., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; Volume 6664, pp. 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aman, B.; Ciobanu, G. Real-Time Migration Properties of rTiMo Verified in Uppaal. In Proceedings of the Software Engineering and Formal Methods—11th International Conference, SEFM 2013, Madrid, Spain, 25–27 September 2013; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Hierons, R.M., Merayo, M.G., Bravetti, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 8137, pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milner, R. The Space and Motion of Communicating Agents; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, W.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, M.; Lu, G.; Fang, Y. Formalization and Verification of Mobile Systems Calculus Using the Rewriting Engine Maude. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 42nd Annual Computer Software and Applications Conference, COMPSAC 2018, Tokyo, Japan, 23–27 July 2018; Reisman, S., Ahamed, S.I., Demartini, C., Conte, T.M., Liu, L., Claycomb, W.R., Nakamura, M., Tovar, E., Cimato, S., Lung, C., et al., Eds.; IEEE Computer Society: New York, NY, USA, 2018; Volume 1, pp. 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badouel, É.; Hélouët, L.; Morvan, C. Petri Nets with Structured Data. Fundam. Inform. 2016, 146, 35–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gardner, P.; Maffeis, S. Modelling dynamic web data. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2005, 342, 104–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sangiorgi, D. On the origins of bisimulation and coinduction. ACM Trans. Program. Lang. Syst. 2009, 31, 15:1–15:41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginzburg, A. Algebraic Theory of Automata, 1st ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, R. An Algebraic Definition of Simulation between Programs. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, London, UK, 1–3 September 1971; Cooper, D.C., Ed.; William Kaufmann: Pleasant Hill, CA, USA, 1971; pp. 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- van Benthem, J. Modal Logic and Classical Logic; Bibliopolis: Asheville, NC, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Forti, M.; Honsell, F. Set theory with free construction principles. Ann. Della Sc. Norm. Super. Pisa Cl. Sci. 4E SÉRie 1983, 10, 493–522. [Google Scholar]

- Hinnion, R. Extensional quotients of structures and applications to the study of the axiom of extensionality. Bull. Soci‘Et’E Mathmatique Belg. 1981, XXXIII, 173–206. [Google Scholar]

- Aman, B.; Ciobanu, G.; Koutny, M. Behavioural Equivalences over Migrating Processes with Timers. In Proceedings of the Formal Techniques for Distributed Systems—Joint 14th IFIP WG 6.1 International Conference, FMOODS 2012 and 32nd IFIP WG 6.1 International Conference, FORTE 2012, Stockholm, Sweden, 13–16 June 2012; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Giese, H., Rosu, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7273, pp. 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Clarke, E.M.; Grumberg, O.; Peled, D.A. Model Checking; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Milo, T.; Suciu, D. Index Structures for Path Expressions. In Proceedings of the Database Theory—ICDT ’99, 7th International Conference, Jerusalem, Israel, 10–12 January 1999; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Beeri, C., Buneman, P., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1540, pp. 277–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y. Query preserving graph compression. In Proceedings of the ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data, SIGMOD 2012, Scottsdale, AZ, USA, 20–24 May 2012; Candan, K.S., Chen, Y., Snodgrass, R.T., Gravano, L., Fuxman, A., Eds.; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Givan, R.; Dean, T.L.; Greig, M. Equivalence notions and model minimization in Markov decision processes. Artif. Intell. 2003, 147, 163–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kurtonina, N.; de Rijke, M. Expressiveness of Concept Expressions in First-Order Description Logics. Artif. Intell. 1999, 107, 303–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Abriola, S.; Barceló, P.; Figueira, D.; Figueira, S. Bisimulations on Data Graphs. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2018, 61, 171–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagin, R.; Halpern, J.Y.; Moses, Y.; Vardi, M.Y. Reasoning about Knowledge; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ditmarsch, H.; French, T.; Velázquez-Quesada, F.R.; Wáng, Y.N. Knowledge, awareness, and bisimulation. In Proceedings of the 14th Conference on Theoretical Aspects of Rationality and Knowledge (TARK 2013), Chennai, India, 7–9 January 2013; Schipper, B.C., Ed.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Quesada, F.R. Bisimulation characterization and expressivity hierarchy of languages for epistemic awareness models. J. Log. Comput. 2018, 28, 1805–1832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).