Abstract

In this paper, a single-species population model with distributed delay and Michaelis-Menten type harvesting is established. Through an appropriate transformation, the mathematical model is converted into a two-dimensional system. Applying qualitative theory of ordinary differential equations, we obtain sufficient conditions for the stability of the equilibria of this system under three cases. The equilibrium of system is globally asymptotically stable when and . Using Poincare-Bendixson theorem, we determine the existence and stability of limit cycle when and . By computing Lyapunov number, we obtain that a supercritical Hopf bifurcation occurs when passes through 0. High order singularity of the system, such as saddle node, degenerate critical point, unstable node, saddle point, etc, is studied by the theory of ordinary differential equations. Numerical simulations are provided to verify our main results in this paper.

1. Introduction

Single-species is a unit of the whole ecosphere. Although most biological populations are multi-species, there is no single population in the strict sense, but because of artificial breeding, there are a lot of single population resources in many human-created environments, which provide indispensable roles for human production and life. Due to the economic interests and production needs, people need to develop the single population resources for a long time and continuously, and to give full play to the best use value on the basis of the lowest cost consumption as possible, so the control and prediction of the single population is particularly important.

Single-species models are widely used in the field of mathematical biology, such as pest management, optimal management of biological resources, epidemic prevention and control, cell growth regulation and so on. Many scholars (see [1,2,3]) have obtained some good properties of these models by quantitative analysis, and the results help us forecast and control the actual production. Wang et al. [4] studied a single-species model and found an optimal harvesting strategy which allows the output to reach a maximum and remains constant. At the same time, the population quantity can attain the maximum level in a precise time interval when the population has been harvested. Dou et al. [5] addressed a non-autonomous Logistic single-species model. The analytical expressions about the best harvesting strategy have been obtained by Pontryagin control and optimization principles of impulsive systems. Recently, many articles have also focused on the study of single-species population model (see [6,7,8,9]).

We know that both discrete and distributed delays tend to bring more rich and complex dynamics to a population dynamic system. For researchers, although models with delay are more complex than without delay, the research results of these models are closer to actual life. In 1948, Hutchinson [10] analyzed a Logistic delay equation characterizing animal populations, and the form is

which could vividly simulate the population size. In (1), the food supply at time t depends on the population number at time . More generally, many scholars studied some models in which the current population density continuously depends on the population density in the past period. For example, Cushing [11] proposed the following single population model with distributed delay

and detailed qualitative results were obtained. Pang et al. [12] considered the following single population model with distributed delay and impulsive state feedback control

and sufficient conditions for the existence and stability of the order-1 periodic solution and limit cycles were obtained, where . Ruan and Wolkowicz [13] built a chemostat model about single population with distributed delay, and they obtained that the system existed Hopf bifurcations by taking the average time delay as the bifurcation parameter. Lian et al. [14] considered a predator-prey system with Holling type IV functional response and time delay. They studied the effects of time delay on this system and obtained the conditions of local asymptotic stability of the positive equilibrium and the existence of local Hopf bifurcations by applying the delay as a bifurcation parameter. Yao et al. [15] investigated the global asymptotic stability of fractional-order complex-valued differential equations with distributed delays. Based on the Laplace transform method, a novel necessary and sufficient condition for the stability is established by embedding the characteristic equation into a two-dimensional complex system. The algebraic criterion is expressed by the fractional exponent, coefficients, and the delay. Many single-species population models with time delay were studied and rich results were obtained (see [16,17,18,19,20,21,22]).

In addition, many scholars have studied the single population model with different forms of harvest. Clark [23] introduced the following single population model with linear harvest,

Clark introduced the single population model (4) with linear harvest, analytical expressions for optimal harvest of a renewable resource stock, which is subject to a stochastic process are found. These expressions give the optimal harvest as an explicit feedback control law. All relations in system (4), including the stochastic process, may be arbitrary functions of the state variable (stock). In 1978, Ludwig et al. [24] put forward the following single population model with nonlinear harvest,

Nonlinear harvesting has been proposed and some novel conclusions have been obtained. Tan et al. [25] considered the following single population system with implusive disturbance and nonlinear harvest:

They obtained good dynamic properties. Li et al. [26] established and analyzed a single-species model with delay weak kernel and constant rate harvesting:

The existence of the equilibrium point of the model (7) is obtained, and the properties of the positive equilibrium state of the population are studied.

Population model with distributed delay and harvest plays an important role in ecosystem, which can reflect the growth rule of invertebrate population better and help us get the best policy of harvesting. This paper is mainly aimed at qualitative analysis of a single-species population model with distributed delay and nonlinear harvest. By the establishment of a single-species population model of differential equations, and using stability analysis methods to discuss the existence and stability of equilibria of the system, we can forecast the development of the population.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we establish a single-species model with distributed delay and nonlinear harvest and make a statement about the model. Then, we will discuss the existence and stability of the equilibria of the system under three different cases from Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5. In Section 6, we verify our results by numerical simulations. The conclusions will be given in Section 7.

2. The Model

We combine distributed delay and nonlinear harvest to consider a new single-species model. From biological and economic points of view, Michaelis-Menten type harvesting is more realistic among the several types of harvesting. Thus, a single-species model with distributed delay and Michaelis-Menten type harvesting is established as follows:

where denotes the density of the population at time t, r denotes the intrinsic rate of increase of the population, and c are positive constants. indicates the impact of distributed time delay. The term represents the effect of distributed delay from the following aspects: The integral for s from to t represents the continuous influence on current state from the past time, which shows the influence interval for distributed delay. That is, the entire interval from the past to current time t has impact on current state . The kernel function represents the influential degree to current state from time s to t. represents the density of population at the past time s. Therefore, the term represents the distributed delay in the model. is simplified Michaelis-Menten type harvesting (the details of this kind of harvesting can be seen in the Refs. [27,28,29]).

Take the transform

which yields the following equivalent system

We consider the existence of equilibria of system (9). Let

the solutions of the equations are and ( if ), where

Denoting

we can also write

We denote , and throughout this paper. In the following discussion, we always assume . Next, we analyze the existence and stability of the equilibria of system (9) under three cases.

3. The Existence and Stability of the Equilibria for

Let us consider the existence and stability of the equilibria of system (9) for the case . Obviously, and in this case.

(1) is clearly an equilibrium of system (9).

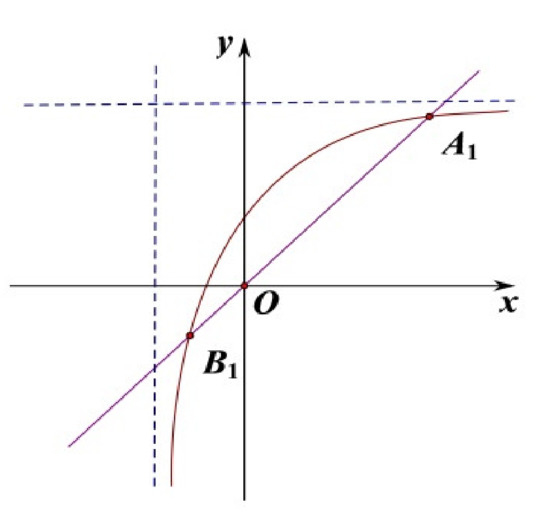

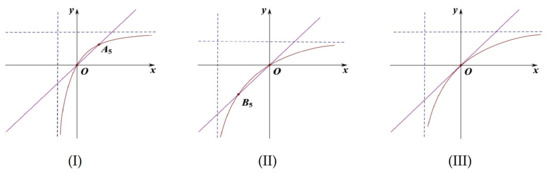

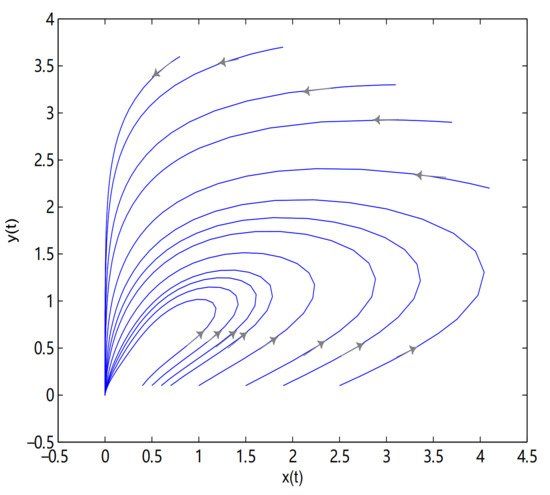

(2) When , is a positive equilibrium of system (9), is a negative equilibrium of system (9) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The locations of the equilibria under the case . x denotes the density of the population and y indicates the impact of distributed time delay.

x denotes the density of the population, y indicates the impact of distributed time delay. There are two solid lines on every sub-chart. The straight line is the equation: , the curve is the equation: . The dotted lines in the Figures are asymptotes to the equation: . The intersections of two solid lines are shown in the following figure.

Theorem 1.

Proof.

When , the Jacobi matrix of system (9) is

At the equilibrium O, the Jacobi matrix of system (9) becomes

which allows us to obtain

Since , then . Obviously, is a saddle point.

Since we can also write and , it is easy for us to simplify as follows

Since , we know that and , then .

Next, we simplify as follows

Let

We have for , as , when .

We discuss the situation of i.e., .

If , then , the positive equilibrium is locally stable in this case. Next, we are going to prove that there is no closed cycle in . There is a unique positive equilibrium in , for convenience, we substitute for . Suppose that there is a closed orbit around , which is, , so there must exist a periodic T such that .

We calculate the index of the closed orbit

where

We rewrite system (9) as follows

Integrating the two sides along the closed orbit , we get

So we know that and also satisfy the following algebraic equation

Hence

where is the coordinate of the equilibrium . We obtain the index of the closed orbit

As , we have

The closed orbit is stable as , which is contradicted by the fact that the equilibrium is asymptotically stable. Therefore, there is no closed orbit.

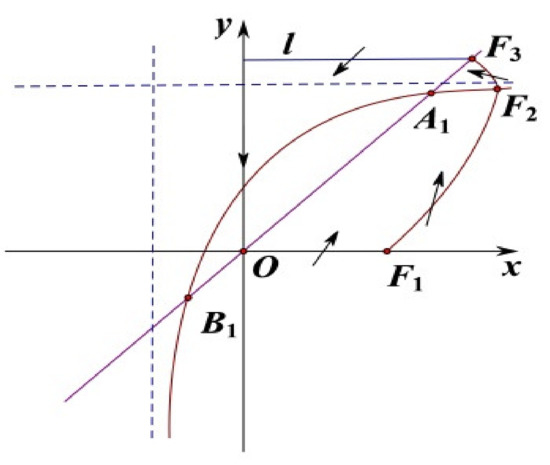

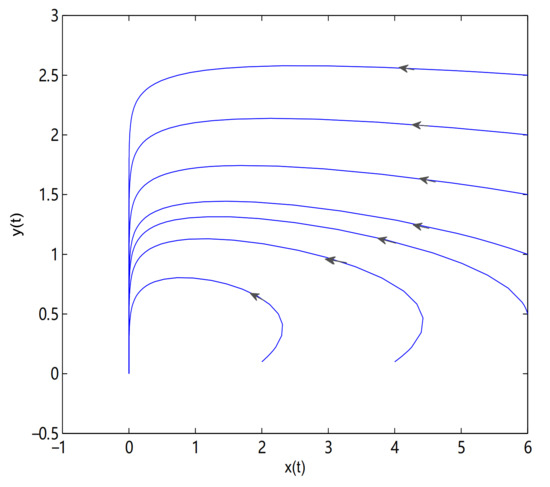

Now, we are going to prove that the solution of system (9) is eventually uniformly bounded (see Figure 2). Take a point on x-axis, draw the trajectory passing through the point of the following equation

and the trajectory intersects isoclinic line at . Comparing the direction of trajectory of system (9) with the tangent direction of trajectory of the above system on yields that

Figure 2.

It shows that the solution of system (9) is uniformly bounded in .

So the trajectory on of system (9) goes through into the interior of from the outer of when the trajectory of system (9) intersects . Then draw the trajectory of the following equation

passing through the point , and the trajectory will intersect isoclinic line at . Comparing the direction of trajectory of system (9) with the tangent direction of trajectory of above system on , we have

So the trajectory on of system (9) goes through into the interior of from the outer of when the trajectory of system (9) intersects . Then draw the line l from the point , which is perpendicular to y-axis. The trajectory of system (9) goes through into the interior of l from the outer of l when the trajectory of system (9) intersects line l. Furthermore, y-axis is an isoclinic line, and the trajectory of system (9) goes through into the interior of x-axis from the outer of x-axis when intersects x-axis. According to the above analysis, the solution of system (9) is eventually uniformly bounded in . In addition, there is no closed orbit in . So the unique positive equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable. □

Next, we discuss the case of i.e., .

We shift point of system (9) to the origin and system (9) can be rewritten as

where is a function of at least fourth order about x. In this case, , that is , then becomes

We can obtain by . So we can know that the eigenvalues of are and (i is the complex unit, similarly hereinafter) by simple calculation. Taking non-singular transformations and , and also denoting by , respectively, system (11) becomes

where

where is a function of at least fourth order about x and y. and are functions and satisfy .

Using the formula for the Lyapunov number of Andronov et al. [30], we have the first Lyapunov number of the equilibrium of system (9) as follows

If

holds, it follows that , where So we obtain the following theorem:

Theorem 2.

If and condition (12) holds, a supercritical Hopf bifurcation occurs near when η passes through 0, where .

Then, we discuss the case of i.e., .

When and , the positive equilibrium is an unstable focus or node. Given what has been proved before, it is not difficult to obtain that the solution of system (9) is also uniformly bounded in . Since the unique positive equilibrium is unstable, we can obtain that there exists at least one limit cycle which is stable in region by Poincaré-Bendixson Theorem.

Particularly, we have known that a Hopf bifurcation occurs when and condition (12) holds. That is to say, the equilibrium is not a true center. The derivative of system (9) at the point is denoted as . We can get the eigenvalues of are , i.e.,

We also define the matrix which satisfies

We obtain that . Using the Friedrich Theorem of Hopf bifurcation, we get the truth that there exists a unique stable limit cycle near when and condition (12) holds. So we get the following Theorem:

Theorem 3.

If and , there exists at least one limit cycle which is stable in Ω. Particularly, there exists a unique stable limit cycle near when and condition (12) holds, where .

4. The Existence and Stability of the Equilibria for

Let us consider the existence and stability of the equilibria for the case .

(1) is clearly an equilibrium of system (9).

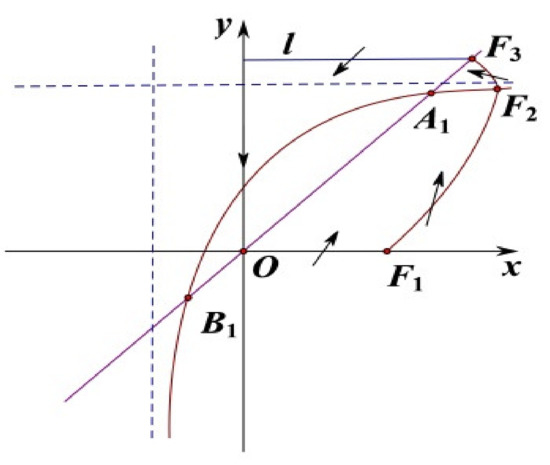

Figure 3.

Figure (I–V) show the locations of the equilibria under the case . x denotes the density of the population and y indicates the impact of distributed time delay. Figure (I) shows the locations of the equilibra in the case and ; The conditions for Figure (II) are and ; and correspond to Figure (II); and are the conditions of Figure (IV); Figure (V) represents the equilibrium of the system under the case and .

(4) When and , and are negative equilibria of system (9), where . Considering the practical significance, this case will not be discussed (see Figure 3III).

(5) When and , is a negative equilibrium of system (9), this case will not be discussed (see Figure 3IV).

Theorem 4.

If , the equilibrium of system (9) is locally stable. More precisely, If and , the positive equilibrium of system (9) is globally asymptotically stable. If and , the positive equilibrium of system (9) is a saddle point. If and , the positive equilibrium of system (9) is locally stable. If and , the positive equilibrium of system (9) is unstable, where .

Proof.

Firstly, we analyze the stability of the equilibrium of system (9). Through the preceding discussion, we have

When , it is easy to get and . So the equilibrium O is locally stable. Particularly, when and , System (9) has only one equilibrium . According to what we have proved before, the solution of system (9) is eventually uniformly bounded in under this case. Since is the isoclinic line, it is not possible in the whole plane to have a closed orbit which surrounds the equilibrium O. If system (9) has a limit cycle which exists in first quadrant, it must contain the equilibrium in the limit cycle. However, under this circumstance, system (9) has no other equilibria except , so we have the conclusion that system (9) has no limit cycle when and . Like the proof of Theorem 1, we know that equilibrium O is globally asymptotically stable when and ; that is, all trajectories of the solution tend to equilibrium O if and .

Secondly, we discuss the stability of the positive equilibrium . We substitute into (10) to get

and we have

It follows from and that becomes

Since and we get

Apparently, when and the positive equilibrium is a saddle point.

Finally, we analyze the stability of the positive equilibrium . We substitute into (10) to get

which yields

Through simplification, we obtain

It follows from the inequalities and that . We also simplify to get

Let

Suppose that then , which means the positive equilibrium is locally stable. Under this circumstance, there are three equilibria for system (9). Therefore, we only consider the local situation of system (9). Since is locally stable, and is always a saddle point, and is locally asymptotically stable, the trajectory of the solution tends to the equilibrium point when the initial value is selected in the attraction domain of equilibrium point , or the trajectory of the solution tends to the equilibrium point O when the initial value is selected in the attraction domain of equilibrium point O.

Suppose that then , which means is a center-type singular point. Under this circumstance, the trajectory of the solution tends to the equilibrium point O or forms a closed trajectory near . In this case, system (9) admits the probability that a Hopf bifurcation occurs near . Since the form of is the same with , we use the result of Theorem 2 to obtain the first Lyapunov number of :

If

holds, it follows that . So we get that a supercritical Hopf bifurcation occurs near .

Suppose that then , which means the positive equilibrium is unstable. Under this circumstance, if is locally stable, and is always a saddle point, and is unstable, then, there is a stable limit cycle generated by Hopf bifurcation in the neighborhood of when . All trajectories of system (9) will be far away from and tend to O. □

Next, we analyze the situation that and are merged into a single equilibrium point . We first give the Theorem 5 and then prove it.

Theorem 5.

If and , the unique positive equilibrium is degenerate, and system (9) has no limit cycle in Ω. The equilibrium O is globally asymptotically stable. More precisely, if and , the equilibrium is a saddle node. If and , the equilibrium is a degenerate critical point.

Proof.

We substitute into (10) to obtain

which yields

where and , it is easy to get . It can easily be shown that this equilibrium point is a higher order singular point. Now we do this work. We shift this point of system (9) to the origin, then, system (9) can be written as

where is a function of at least third order about x.

When , (14) changes into

Then the eigenvalues of are and . At this time, is a codimension 1 singular point. Using , and , we also denote and by and t, respectively. System (15) becomes

Apply to get

We take the above equality into and obtain

where is a function of at least third order about x and y. It follows that the right side of the above equality is a polynomial about x and y, and the order of it is at least two.

By Theorem 7.1 in Chapter 2 of Zhang et al. [31], we know that is a saddle node.

When , (14) changes into

Then the eigenvalues of are and . That is, is a codimension 1 singular point. System (15) becomes

Taking the non-singular transformations , and , we also denote and by and t, respectively. System (16) becomes

By a one-to-one transformation in a sufficiently small neighborhood of the origin

system (17) becomes

We still denote by with terms of order no less than two. We write

where and are analytic functions, moreover, . Hence the origin of system (18) is a double singularity.

By Theorem 7.3 in Chapter 2 and its Corollary of Zhang et al. [31], we find that the origin of system (17) is a degenerate critical point. That is, the equilibrium point of system (9) is a degenerate critical point.

According to what we have proved before, the solution of system (9) is eventually uniformly bounded in under this case. Since is the isoclinic line, it is not possible in the whole plane to have a closed orbit which surrounds the equilibrium O. If system (9) has a limit cycle which exists in first quadrant, there must contain the equilibrium in the limit cycle, and the index of it must be one. However, the index of equilibrium is zero whether it is a saddle node or a degenerate critical point, so we have the conclusion that system (9) has no limit cycle when . The same to the proof of Theorem 1, we know that equilibrium O is globally asymptotically stable when and . That is, all trajectories of the solution tend to equilibrium O when and . □

5. The Existence and Stability of the Equilibria for

Let us consider the existence and stability of the equilibria for the case .

(1) is clearly an equilibrium of system (9).

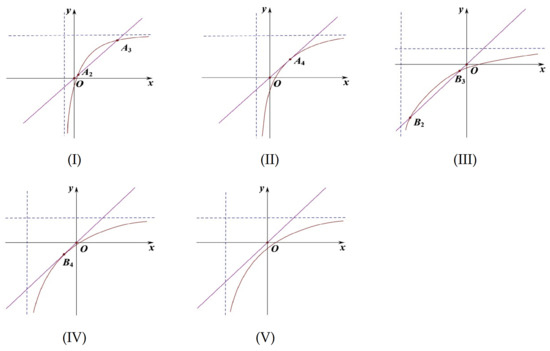

Figure 4.

Figure (I–III) show the locations of the equilibria under the case , respectively. x denotes the density of the population. y indicates the impact of distributed time delay. Figure (I) corresponds to the case and ; Fiure (II) shows the case and and Figure (III) corresponds to the case and .

(3) When and , is a negative equilibrium of system (9). This case will not be discussed (see Figure 4II).

Theorem 6.

Proof.

When , we get . It can easily be shown that the equilibrium O is a higher order singular point. We change (9) into (19).

Performing the nonsingular transformations , and , we still denote and by and t, and (19) becomes

When , i.e., , the positive equilibrium does not exist under this condition, that is, the equilibrium O is a triple singularity (20) becomes

Let , then

by Taylor expansion at , we have

After some calculations, we have

By Theorem 7.1 in Chapter 2 of Zhang et al. [31], we know that O is an unstable node.

According to what we have proved before, the solution of system (9) is eventually uniformly bounded in under this case. Since is the isoclinic line, it is not possible in the whole plane to have a closed orbit which surrounds the equilibrium O. In addition, if the closed orbit exists in some quadrant, then there must be an equilibrium in the closed orbit. So we have the conclusion that there is no closed orbit in the whole plane when and . Meanwhile, the linear system of system (19) is as follows

and . It follows that system (19) has a singular line , i.e., when and . Then all the trajectories tend to the singular line .

When , i.e., , the positive equilibrium exists if , and the negative equilibrium exists if , that is, the equilibrium O is a double singularity. We rewrite (20) into the following equation

Let , then

By some calculations, we derive

By Theorem 7.1 in Chapter 2 of [31], we know that O is a saddle node. □

Next, we are going to analyze the stability of the equilibrium . Obviously, the equilibrium O as a saddle node simultaneously exists with the equilibrium when and . We first give the Theorem 7 and then prove it.

Theorem 7.

If and , the unique positive equilibrium point is locally stable. If and , the unique positive equilibrium is unstable and there exists at least one limit cycle in a small neighborhood of .

Proof.

It is difficult to check the sign of , so we set .

When then , which means the positive equilibrium is locally stable. When then , which means the positive equilibrium is unstable. In addition, the solution of system (9) is eventually uniformly bounded in , so there exists at least one limit cycle in a small neighborhood of .

When then , which implies a Hopf bifurcation may occur in system (9). □

Next, we are going to talk about the situation of i.e., .

Theorem 8.

If and condition (22) holds, a supercritical Hopf bifurcation occurs near when ξ passes through 0, where .

Proof.

Let us now verify the existence of a Hopf bifurcation under the condition . Suppose we have . We shift this point of system (9) to the origin. Then, system (9) can be written as

Setting , the eigenvalues of are and . Using the nonsingular transformations , , and also denoting by , respectively, system (21) becomes

where

and are functions and satisfy .

Applying the formula for the Lyapunov number of Andronov et al. [30], we have the first Lyapunov number of the equilibrium point of system (9) as follows

If

holds, then . The Theorem 8 is proved. □

Applying the Friedrich Theorem of Hopf bifurcation as before, we can know that there exists a unique stable limit cycle near when and condition (22) holds.

6. Numerical Simulation

In the following, applying dde23 in matlab, we verify our theoretical results by numerical simulations for system (9). According to the numerical constraints in the theorems, we first determine the values of b, r and c. Combined with numerical simulations, and try several times to find the value of that meets the conditions. For the value of , it is easy to calculate with the given conditions. All figures correspond to the cases in the table above.

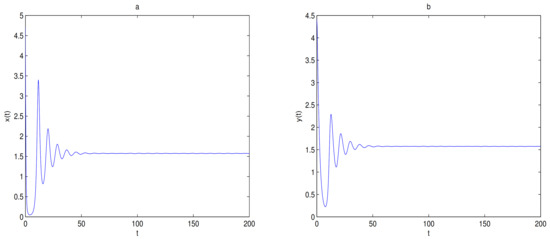

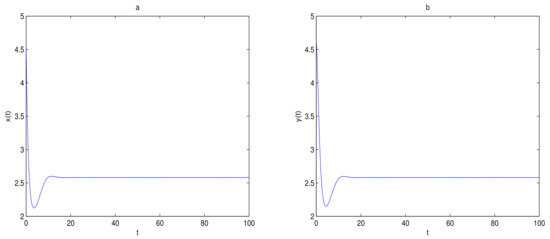

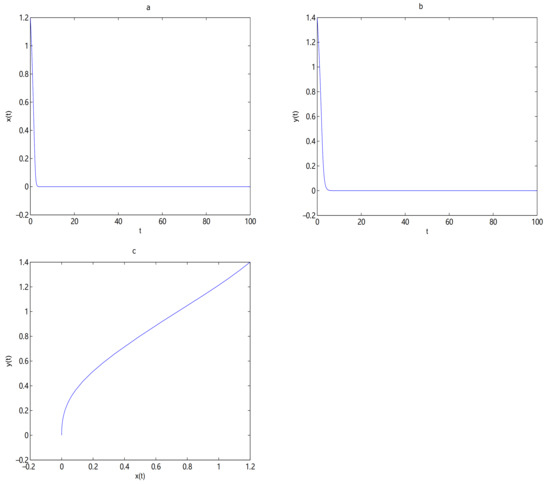

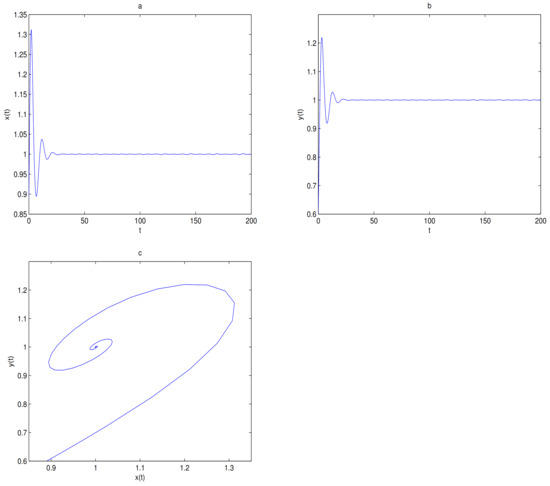

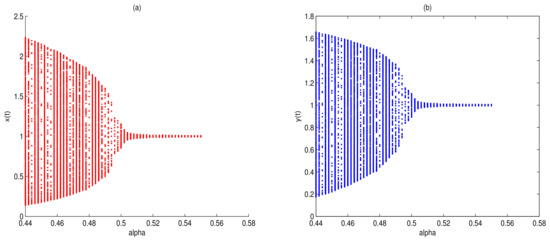

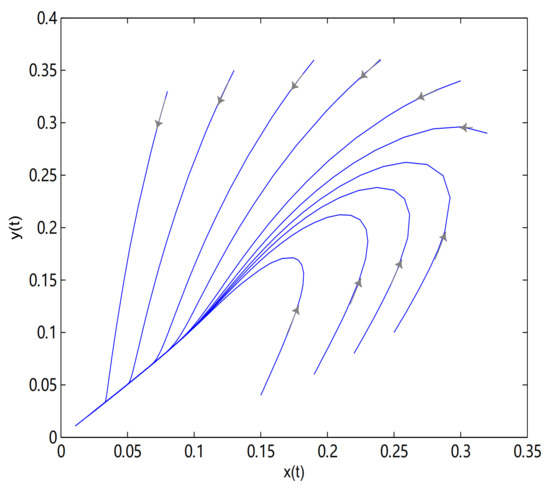

For Theorems 1–3, let and , O is always a saddle. is globally asymptotically stable when (see Figure 5) and there exists one limit cycle in when , in here (see Figure 6). Choosing as a bifurcation parameter, a supercritical Hopf bifurcation occurs near when passes through 0.288, in here (see Figure 7).

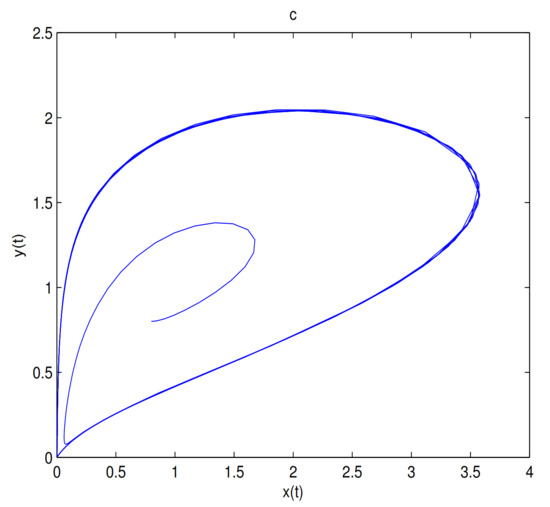

Figure 6.

There exists a limit cycle in when . . Subfigure (a) is time series of , subfigure (b) is time series of , and subfigure (c) is phase diagram of system (9).

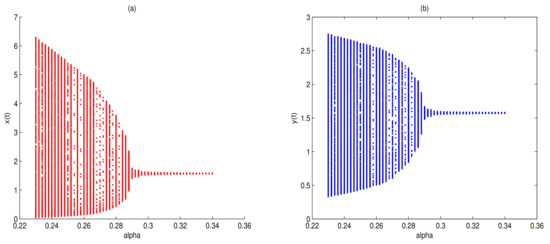

Figure 7.

There is a supercritical Hopf bifurcation when passes through 0, i.e., passes through 0.288. Here , . Figure (a) is a biurcation diagram of with respect to , and Figure (b) is a bifurcation diagram of with respect to .

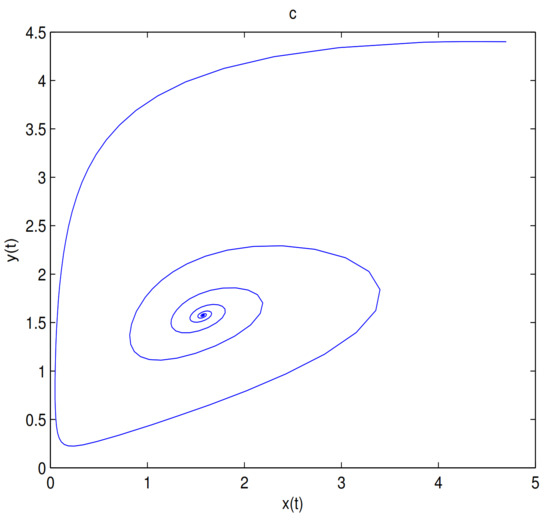

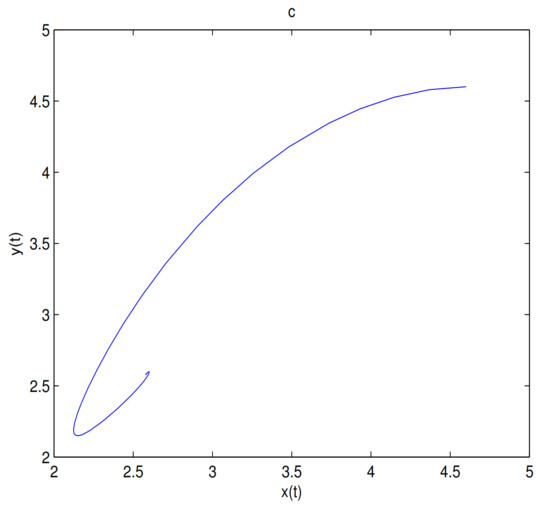

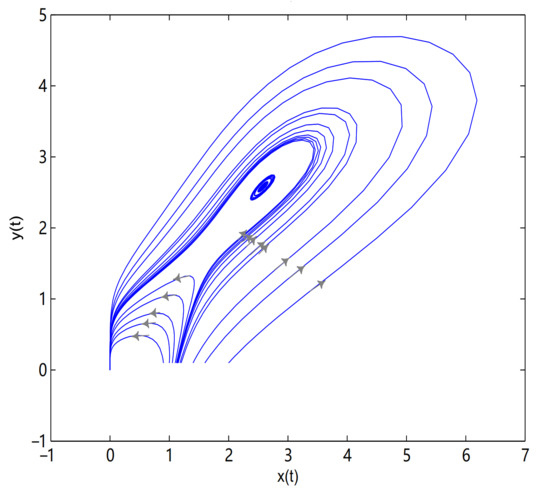

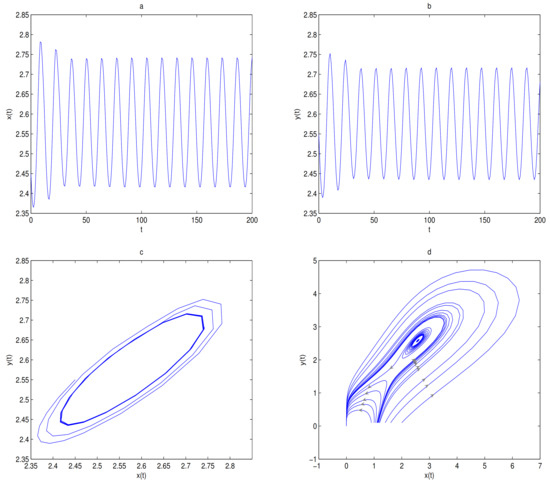

For Theorem 4, let and , O is the only equilibrium point of system (9) at this time, and O is globally asymptotically stable. In here initial values are (6, 2.5), (6, 2), (6, 1.5), (6, 1), (4, 0.1) and (2, 0.1), we see that all trajectories tend to O (see Figure 8). Let and , O is always locally stable, and is always a saddle. is locally stable when . the trajectory tends to when the initial value is selected in the attraction domain of , for example, (see Figure 9). The trajectory tends to O when the initial value is selected in the attraction domain of O, for example, (see Figure 10). is a center-type equilibrium point when , in here initial values are (2.57, 2.57), (2.42, 2.42), (2.1, 0.1), (1.6, 0.1), (1.4, 0.1), (1.2, 0.1), (1.18, 0.1), (1.15, 0.1), (1.14, 0.1), (1.135, 0.1), (1.133, 0.1), (1.131, 0.1), (1.13, 0.1), (1.1, 0.1), (1.05, 0.1), (1, 0.1) and (0.9, 0.1) (see Figure 11). is unstable when , and a limit cycle is generated by Hopf supercritical bifurcation in the neighborhood of . We choose as initial value (see Figure 12c). We choose the same initial values as in Figure 11, and we see that the trajectory forms a limit cycle with (2.57,2.57) as the initial value, and everything else tends to O (Figure 12d).

Figure 8.

O is globally asymptotically stable. All trajectories tend to O. In here , .

Figure 9.

O is locally stable. (1.75, 1.75) is a saddle. (2.581, 2.581) is locally stable. The trajectory tends to when the initial value is . In here , . Subfigure (a) is time series of , subfigure (b) is time series of and subfigure (c) is phase diagram of system (9).

Figure 10.

O is locally stable. (1.75, 1.75) is a saddle. (2.581, 2.581) is locally stable. The trajectory tends to O when the initial value is . In here , . Subfigure (a) is time series of , subfigure (b) is time series of , and subfigure (c) is phase diagram of system (9).

Figure 11.

O is locally stable. (1.75, 1.75) is a saddle. (2.581, 2.581) is a center-type equilibrium point. In here .

Figure 12.

Subfigure (a) is time series of , subfigure (b) is time series of and subfigure (c) is phase diagram of system (9). O is locally stable, (1.75, 1.75) is a saddle and (2.581, 2.581) is unstable. A limit cycle is generated by Hopf supercritical bifurcarion near in subfigure (c), and subfigure (d) shows that directions of these trajectories. In here , . The initial value in subfigure (c) is . The initial values in subfigure (d) are the same as in Figure 11.

For Theorem 5, let , O is always globally asymptotically stable, and are merged into a single equilibrium . Meanwhile, is a saddle node when , in here initial values are (2.7, 3.3), (2.9, 2.9), (0.8, 3.6), (3.2, 2.2), (1.9, 3.7), (2.5, 0.1), (1.9, 0.1), (1.5, 0.1), (1, 0.1), (0.7, 0.1), (0.6, 0.1), (0.5, 0.1) and (0.4, 0.1) (see Figure 13). is a degenerate critical point when , in here initial values are (3.1, 3.3), (3.7, 2.9), (0.8, 3.6), (4.1, 2.2), (1.9, 3.7), (2.5, 0.1), (1.9, 0.1), (1.5, 0.1), (1, 0.1), (0.7, 0.1), (0.6, 0.1), (0.5, 0.1) and (0.4, 0.1) (see Figure 14).

Figure 13.

O is globally asymptotically stable. (0.5, 0.5) is a saddle node. In here , .

Figure 14.

O is globally asymptotically stable. (0.5, 0.5) is a degenerate critical point. In here .

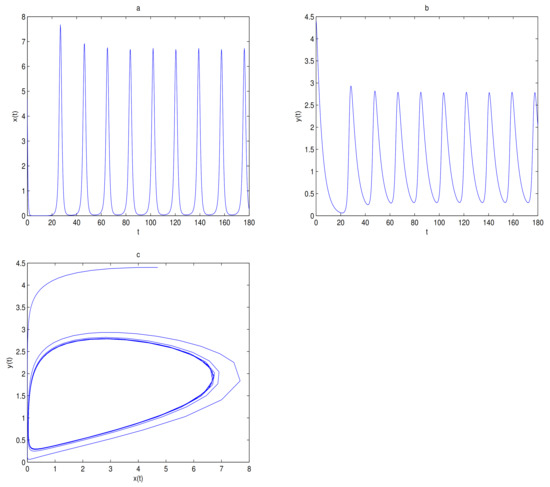

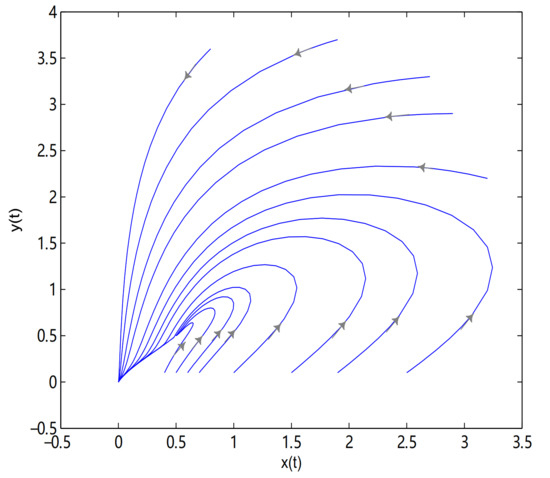

For Theorems 6–8, first, let and ; O is always a saddle node. is unstable and there exists a limit cycle near when , the initial value is (0.8, 0.8) (see Figure 15). is locally stable when , and the initial value is (0.89, 0.6) (see Figure 16). By choosing as a bifurcation parameter, a supercritical Hopf bifurcation occurs near when passes through 0.5 (see Figure 17). Let and , O is an unstable node, in here initial values are (0.28, 0.34), (0.32, 0.29), (0.19, 0.06), (0.25, 0.1), (0.13, 0.35), (0.08, 0.33), (0.24, 0.36), (0.22, 0.08), (0.15, 0.04) and (0.19, 0.36), all trajectories tend to singular line (see Figure 18).

Figure 15.

O is a saddle node, and there exists at least one limit cycle near . In here . Subfigure (a) is time series of , subfigure (b) is time series of and subfigure (c) is phase diagram of system (9).

Figure 16.

O is a saddle node. is locally stable. In here . Subfigure (a) is time series of , subfigure (b) is time series of , and subfigure (c) is a phase diagram of system (9).

Figure 17.

There is a supercritical Hopf bifurcation when passes through 0, i.e., passes through 0.5. In here . . . Subigure (a) is a bifurcation diagram of with respect to and subfigure (b) is a bifurcation diagram of with respect to .

Figure 18.

O is an unstable node. The trajectories tend to . In here , .

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we established a single population with distributed delay and nonlinear harvesting. Sufficient conditions of existence and stability of equilibria in three different cases have been derived. We presented the results in Table 1. We choose as a function for the impact of distributed delay, and choose as a function for the harvest. Since this type of harvest exists in the ecosphere especially for vertebrates, and single species population model with distributed delay and Michaelis-Menten type harvesting has never been considered and studied by other scholars, our work is novel. Our results show that the qualitative conclusions obtained are rich and have certain guiding significance for some species with nonlinear harvest. In the future work, we will study single-species models with other harvesting types, such as , etc.

Table 1.

The results under different conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.L.; Formal analysis, Z.L., S.F., H.X. and H.W.; Funding acquisition, Z.L. and H.X.; Investigation, Z.L.; Software, H.W.; Supervision, Z.L.; Writing original draft, S.F.; Writing review editing, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 11961023, 11701163).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the anonymous referees and the editor for their careful reading of the original manuscript and their kind comments and valuable suggestions that lead to truly significant improvement of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Brauer, F.; Castillo-Chavez, C. Continuous Single-Species Population Models with Delays. In Mathematical Models in Population Biology and Epidemiology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkel, G. Single species model for population growth depending on past history. In Seminar on Differential Equations and Dynamical Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Shuai, Z.S.; Wang, K. Optimal impulsive harvesting policy for single population. Nonlinear Anal. RWA 2003, 4, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, K. Optimal control of harvesting for single population. Appl. Math. Comput. 2004, 156, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, J.W.; Li, S.D. Optimal impulsive harvesting policies for single-species populations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2017, 292, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.D.; Zhang, T.H. Permanence and extinction of a single species model in polluted environment. Int. J. Biomath. 2020, 13, 2050031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, F.; Hu, G. Dynamical behaviors of a stochastic single-species model with Allee effects. Methodol. Comput. Appl. Probab. 2021, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.C.; Zhang, C.Y.; Feng, Z.S. Hopf bifurcation in a delayed single species network system. Int. J. Bifurcat. Chaos 2021, 31, 2130008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves Luis, R.T.; Maia, L.P. A simple individual-based population growth model with limited resources. Phys. A 2021, 567, 125721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchinson, G.E. Circular causal systems in ecology. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1948, 50, 221–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cushing, J.M. Bifurcation of periodic solutions of integrodifferential systems with application to time delay model in population dynamics. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1977, 33, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, G.P.; Chen, L.S. Periodic solution of the system with impulsive state feedback control. Nonlinear Dyn. 2014, 78, 743–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.G.; Wolkowicz Gail, S.K. Bifurcation analysis of a chemostat model with a distributed delay. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 1996, 204, 786–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lian, F.Y.; Xu, Y.T. Hopf bifurcation analysis of a predator-prey system with Holling type IV functional response and time delay. Appl. Math. Comput. 2009, 215, 1484–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.C.; Yang, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.S. A stability criterion for fractional-order complex-valued differential equations with distributed delays. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 152, 111277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiello, W.G.; Freedman, H.I. A time-delay model of single-species growth with stage structure. Math. Biosci. 1990, 101, 139–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, H.I.; Wu, J.H. Periodic solutions of single-species models with periodic delay. SIAM J. Math. Anal. 1992, 23, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, G. On a delay-differential equation for single specie population variations. Nonlinear Anal. TMA 1987, 11, 1051–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, F.; Li, J.B. On the existence of periodic solutions of a neutral delay model of single-species population growth. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2001, 259, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yin, F.Q.; Li, Y.K. Positive periodic solutions of a single species model with feedback regulation and distributed time delay. Appl. Math. Comput. 2004, 153, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, S.G. Delay differential equations in single species dynamics. In Delay Differential Equations and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.C.; Zhang, W.Z. Bifurcation analysis in single-species population model with delay. Sci. China Math. 2010, 53, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.W. Mathematical Bioeconomics: The Optimal Management of Renewable Resources; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, D.; Jones, D.D.; Holling, C.S. Qualitative analysis of insect outbreak systems: The spruce budworm and forest. J. Anim. Ecol. 1978, 47, 315–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tan, R.H.; Liu, Z.J.; Robert, A.C. Periodicity and stability in a single-species model governed by impulsive differential equation. Appl. Math. Model. 2012, 36, 1085–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Huang, S.B. Stability and bifurcation for a single-species model with delay weak kernel and constant rate harvesting. Complexity 2019, 2019, 1810385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, R.P.; Chandra, P. Bifurcation analysis of modified Leslie-Gower predator-prey model with Michaelis-Menten type prey harvesting. J. Math. Anal. Appl. 2013, 398, 278–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C.W. Mathematical models in the economics of renewable resources. SIAM Rev. 1979, 21, 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, T.; Mukherjee, R.N.; Chaudhari, K.S. Bioeconomic harvesting of a prey-predator fishery. J. Biol. Dyn. 2009, 3, 447–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Andronov, A.; Leontovich, E.A.; Gordon, I.I.; Maier, A.G. Theory of Bifurcations of Dynamical Systems on a Plane; Israel Program for Scientific Translations: Jerusalem, Israel, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.F.; Ding, T.R.; Huang, W.Z.; Dong, Z.X. Qualitative Theory of Differential Equations. In Translations of Mathematical Monographs, Volume 101; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).