Abstract

In 1977, Davis et al. proposed a method to generate an arrangement of that avoids three-term monotone arithmetic progressions. Consequently, this arrangement avoids k-term monotone arithmetic progressions in for . Hence, we are interested in finding an arrangement of that avoids k-term monotone arithmetic progression, but allows -term monotone arithmetic progression. In this paper, we propose a method to rearrange the rows of a magic square of order and show that this arrangement does not contain a k-term monotone arithmetic progression. Consequently, we show that there exists an arrangement of n consecutive integers such that it does not contain a k-term monotone arithmetic progression, but it contains a -term monotone arithmetic progression.

1. Introduction

A sequence is said to have a k-term monotone arithmetic progression if there is a set of indices such that the k-term subsequence is either an increasing or a decreasing arithmetic progression.

Davis et al. [1] proposed a way to generate an arrangement of that avoids three-term monotone arithmetic progressions. An arrangement of is a sequence such that . An arrangement of is also called a permutation of .

Theorem 1

([1]). Let . There is a permutation of that does not contain a three-term monotone arithmetic progression.

Let be the set of positive integers. Davis et al. [1] and Sidorenko [2] showed that there is no permutation of that avoids three-term monotone arithmetic progressions. However, they [1] showed that there exists permutations of that avoid five-term monotone arithmetic progression, implying the existence of permutations of the integers avoiding arithmetic progressions of length seven. Recently, Geneson [3] constructed a permutation of the integers avoiding arithmetic progressions of length six. Up to now, an intriguing question, whose answer is still unknown, is whether there exists a permutation of that avoids four-term monotone arithmetic progressions [4].

Let denote the number of permutations of that contain no three-term monotone arithmetic progressions. Davis et al. [1] established that . These bounds were then improved by [5,6,7]. LeSaulnier and Vijay [5] also showed that any permutation of the positive integers must contain a three-term arithmetic progression with an odd common difference as a subsequence and constructed a permutation of the positive integers that does not contain any four-term arithmetic progression with an odd common difference. Geneson [3] also proved a lower bound of on the lower density of subsets of positive integers that can be permuted to avoid arithmetic progressions of length four, sharpening the lower bound of from [5].

As a consequence of Theorem 1, there exists an arrangement of that avoids k-term monotone arithmetic progression, where . However, up to now, there is no proposed arrangement of that avoids a k-term monotone arithmetic progression, but contains a -term monotone arithmetic progression. In this paper, for , we show that the rows of a magic square of order can be arranged in a way that the resulting arrangement does not contain a k-term monotone arithmetic progression, but it contains a -term monotone arithmetic progression. Then, we apply the result to show that there exists an arrangement of n consecutive integers such that it does not contain a k-term monotone arithmetic progression, but it contains a -term monotone arithmetic progression.

2. -Term Monotone Arithmetic Progression

In this section, we prove that given any n consecutive integers with , there is an arrangement that avoids k-term monotone arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term monotone arithmetic progression.

2.1. Magic Square

In 1624 France, Claude Gaspard Bachet described the following “diamond method” for constructing odd ordered magic squares in his book Problèmes Plaisants [8].

Step 1:

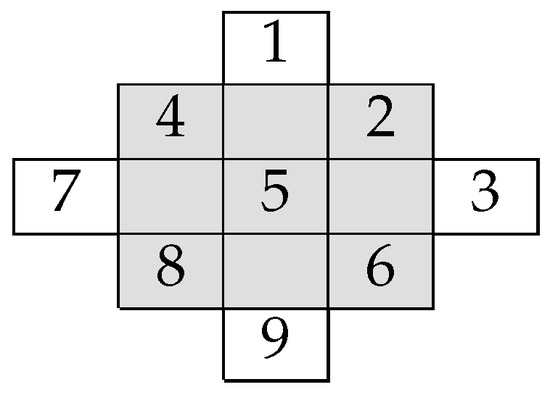

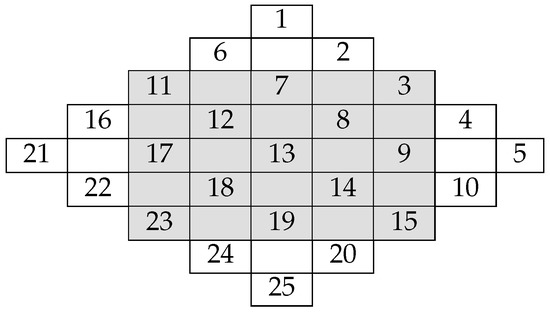

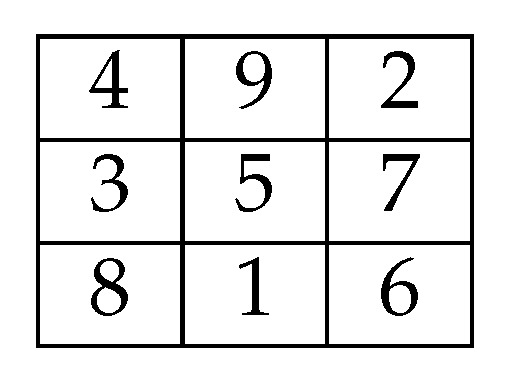

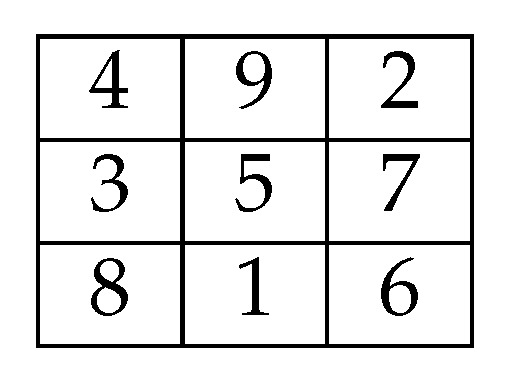

First, for , we arrange in an square. We extend a square to form a diamond structure as in Figure 1. Then, we put the integers in order along descending diagonals into the square. For and , Figure 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the and extended squares, respectively.

Figure 1.

A square.

Figure 2.

A square.

Step 2:

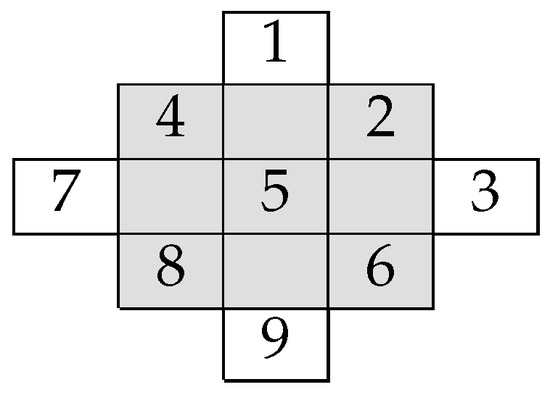

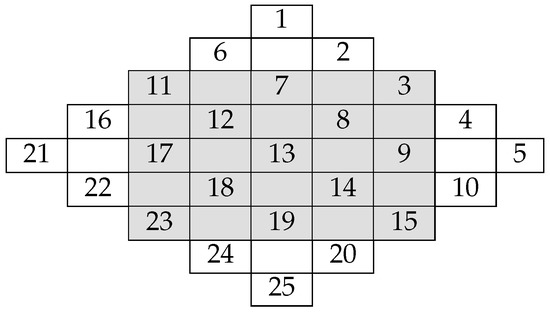

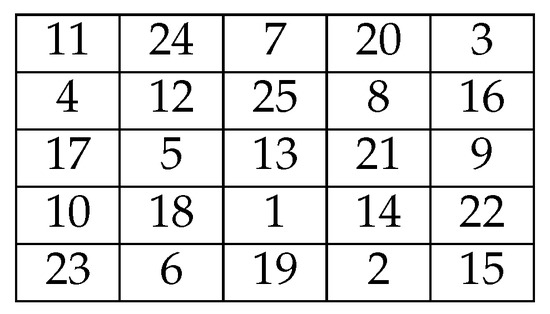

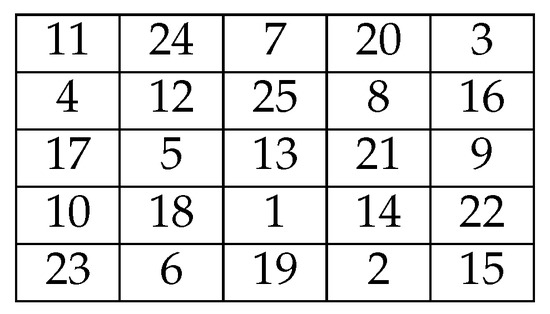

Then, move the numbers on the right leftwards in the same row. Similarly, move the numbers on the left rightwards in the same row. Furthermore, move the numbers on the top downwards in the same column, and move the numbers at the bottom upwards in the same column. See Figure 3 and Figure 4 for and 4. This gives a magic square with magic sum .

Figure 3.

A magic square.

Figure 4.

A magic square.

Let be the i-th row of the magic square constructed this way, i.e.,

Note that for the first row , we have:

For the last row , we have:

For row , if k is odd, then:

whereas if k is even, then:

For row with , if i is odd, then:

whereas if i is even, then:

For row with , if i is odd, then:

whereas if i is even, then:

2.2. Arrangement That Avoids K-Term Arithmetic Progressions

In this section, we form a sequence P, which is an arrangement of the rows of the magic square from Section 2.1 that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions.

Theorem 2.

Suppose . Let be the sequence of integers in the i-th row from left to right in the magic square formed by using the method in Section 2.1 where . Then, the sequence avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but it has a -term arithmetic progression, .

Remark 1.

Note that Theorem 2 is not true for . In fact, the row has a three-term arithmetic progression.

Proof.

Note that for ,

does not contain a 4-term arithmetic progression, but has a 3-term arithmetic progression . Therefore, we may assume that .

By Equations (1), (5) and (6), for , every integer in the row is either congruent with or . By Equations (2), (7) and (8), for , every integer in the row is either congruent with or . Lastly, by Equations (3) and (4), every integer in the row is congruent with . Note that the only integer congruent with in row is , whereas the only integer congruent with in row is one. Thus, all the integers congruent with in appear in rows , and . For , all the integers congruent with in appear in exactly two different rows.

Since is in for and , the progression is a -term arithmetic progression in P. Now, we proceed to show that P does not have any k-term arithmetic progressions. We prove it by contradiction. Assume that there exists a k-term monotone arithmetic progression in P. Then, there exists a nonzero integer d such that:

for all . Note that .

Since:

should appear before if we read the elements from left to right in P. Thus, if is in for some , then will be in where or , and if is in , then will be in . Furthermore, if and are both in for some , then will appear after in the sequence P when we read from left to right.

Suppose or for some . If the former holds, then and , a contradiction. If the latter holds, then and , a contradiction. Hence, we may assume that or for all .

If two consecutive terms of T are in for some , then or . Suppose no two consecutive terms of T are in . This means that if is in , then will be in where or and . Since , either there exists such that and are in and , respectively, for some or and are in and , respectively, or and are in and , respectively. If such a exists, then or , otherwise, or .

Case 1:

Suppose . This means no two consecutive terms of T are in and and are in and , respectively. Furthermore, and . Note that . Therefore, is in or . If is in , then will be in , a contradiction. If is in , then , a contradiction. If is in , then , a contradiction.

Case 2:

Suppose . This means no two consecutive terms of T are in and and are in and , respectively. Furthermore, and . Note that and . If , then is in or , whereas is in or . This is not possible as should appear before in the sequence P. Suppose . Now, is in or , whereas is in or , again not possible.

Case 3:

Suppose . This means no two consecutive terms of T are in and there exists such that and are in and , respectively, for some or and are in and , respectively. Now, cannot be in ; otherwise, will be in . Note that . Suppose is in for some . Then, or . If , then . Since , it must be in . Therefore, is in , a contradiction. Suppose . Since must appear after in P, we have and is in for some and is in . This implies that either is in the same row as or is in the same row as , a contradiction. Similarly, we also cannot have in for some .

Case 4:

Suppose . Now, cannot be in ; otherwise, will be in and . Suppose is in for some . Then, is either congruent with or . Suppose . Then, . Since and , it must be in . Thus, is also in and , a contradiction. Suppose . Then, . If , then must be in . Therefore, is also in and , a contradiction. Suppose . Then, and it is in . Therefore, . Now, . Since , is in or , which is not possible as is in .

Suppose is in for some . Then, is either congruent with or . Suppose . Then, . If , then is in or , which is not possible. If , then and . Therefore, is in or , again not possible. Suppose . Then, . If , then is in or , which is not possible. If , then and . Therefore, is in or , again not possible.

Case 5:

Suppose .

If two consecutive terms of T, say and are in , then , a contradiction. Suppose and are in . Then, and . By Equation (1), for some and for some . Now,

Therefore, , a contradiction.

Suppose and are in . Then, and . By Equation (2), for some and for some . Furthermore, . Now,

Therefore, , a contradiction. Hence, we may assume that no consecutive terms of T are in or .

Suppose is in . Then, is either congruent with or . Suppose . Then, . Note that is not in , for no two consecutive terms of T are in . Therefore, is in . This means is in , for no two consecutive terms of T are in . Therefore, must be in , a contradiction as no two consecutive terms of T are in .

Suppose . Then, . Therefore, is in , or . Note that cannot be in , otherwise will be in . If is in , then , a contradiction. If is in , then , a contradiction.

Suppose is in for some . Then, is either congruent with or . Suppose . Then, and . Since is not in , it must be in . If , then must be in , for it cannot be in . Since , we must have in or . Both cases also cannot happen. If , then is in or , which is not possible. Suppose . Then, . If , then must be in . Since is not in , it must be in . However, then is also in , a contradiction. If , then is in or , which is not possible.

Suppose is in for some . Then, is either congruent with or . Suppose . Then, . Therefore, is in , or . Note that cannot be in ; otherwise, will be in . If is in , then , a contradiction. If is in , then , a contradiction.

Case 6:

Suppose .

Then, for all j and or . If , then . Therefore, we must have and . Therefore, is in row , whereas is in , which is not possible. If , then . Therefore, we must have and . Now, for imply that for all . This is also not possible as should appear after , but before in P. Hence, we may assume that .

Case 6.1:

Suppose . Then, is either in or for all j. Note that and for all . Therefore, we may assume that is in for all .

Case 6.1.1:

Suppose k is odd. Let

Note that , and are disjoint. By Equation (3), . Therefore, one of the where must contain at least two elements. Thus, .

Suppose . If , then for some . Now,

and . Therefore, is in . This is not possible. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , then for some . Since is the last term in , is not in , a contradiction. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , then for some . Now, is the last term in . Therefore, and:

a contradiction. Thus, if , then .

Hence, for exactly one . Now, , , and . Thus, , a contradiction.

Case 6.1.2:

Suppose k is even. Let:

Note that , and are disjoint. By Equation (4), . Therefore, one of the where must contain at least two elements. Thus, .

Suppose . If , then for some . Since is the last term in , is not in , a contradiction. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , then for some . Now,

and . Therefore, is in . This is not possible. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , for some . Now, is the last term in . Therefore, and:

a contradiction. Thus, if , then .

Hence, for exactly one . Now, , , and . Thus, and . This means can only be in or . Since , must be in , that is . Now,

a contradiction.

Case 6.2:

Suppose . Then is either in or for all j. Since there are at most integers in that are congruent with , we must have in . Suppose both and are in . By Equation (1), we must have and and for some . Since there are at most integers in that are congruent with , we must have in . The largest integer congruent with in is , and the smallest integer congruent with in is . Note that . Let s be the smallest integer such that is in and is in . Since both and are in , . Therefore,

a contradiction. Suppose is in , but is in . Then, we must have for all . By Equation (2), . On the other hand,

a contradiction.

Case 6.3:

Suppose where . Then, for all j, is either in or .

Case 6.3.1:

Suppose is odd. Let:

Note that , and are disjoint. By Equations (5) and (6) (or Equations (1) and (6) when ), . Therefore, one of the where must contain at least two elements. Thus, .

Suppose . If , then for some . Now, is the last term in . Therefore, and:

a contradiction. Thus, if , then . Now, if , then for some . By Equation (6), . This is not possible as should appear before in P. Thus, if , then one and k must be in . This implies that for all . This is not possible as . Hence, and .

Suppose . If , then for some . Now,

and , a contradiction. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , then for some . Since is the last term in , is not in , a contradiction. Thus, if , then .

Hence, for at most one . If , then:

a contradiction. Similarly, if , then , again a contradiction.

Case 6.3.2:

Suppose is even. Let:

Note that , and are disjoint. By Equations (5) and (6), . Therefore, one of the where must contain at least two elements. Thus, .

Suppose . If , then for some . Since is the last term in , is not in , a contradiction. Thus, if , then . Now, if is not in , then for some . By Equation (5) . This is not possible as should appear before in P. Thus, if , then one and k must be in . This implies that for all . This is not possible as . Hence, and .

Suppose . If , then for some . Now,

and , a contradiction. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , then for some . By Equation (5), , which is not possible. Thus, if , then .

Hence, for at most one . If , then:

a contradiction. Similarly, if , then , again a contradiction.

Case 6.4:

Suppose where . Then, is either in or for all j.

Case 6.4.1:

Suppose is odd. Let:

Note that , and are disjoint. By Equations (7) and (8), . Therefore, one of the where must contain at least two elements. Thus, .

Suppose . If , then for some . Therefore, , and this is not possible. Thus, if , then . Now, if , then for some . Therefore, , again not possible. Thus, if , then one and k must be in . This implies that for all . Therefore, , a contradiction. Hence, and .

Suppose . If , then for some . Therefore, , and this is not possible. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , then for some . Therefore,

and , a contradiction. Thus, if , then . Hence, for at most one . If , then:

a contradiction. Similarly, if , then , again a contradiction.

Case 6.4.2:

Suppose is even. Let:

Note that , and are disjoint. By Equations (7) and (8) (or Equations (2) and (6) when ), . Therefore, one of the where must contain at least two elements. Thus, .

Suppose . If , then for some . Therefore, , and this is not possible. Thus, if , then . Now, if , then for some . Therefore, , again not possible. Thus, if , then one and k must be in . This implies that for all . Therefore, , a contradiction. Hence, and .

Suppose . If , then for some . Therefore, , and this is not possible. Thus, if , then .

Suppose . If , then for some . Therefore,

and , a contradiction. Thus, if , then . Hence, for at most one . On the other hand, if , then:

a contradiction. Similarly, if , then , again a contradiction.

Hence, P does not contain any k-term monotone arithmetic progressions. This completes the proof of the theorem. □

Corollary 1.

Let . For each integer n with , there is an arrangement of that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression.

Proof.

For , the sequence avoids three-term arithmetic progressions. Now, for , remove from P, and denote the resulting sequence as . For instance, if , then , and if , then . Note that avoids three-term arithmetic progressions. Therefore, we may assume that .

Suppose . First, we show that if , then there is an arrangement of that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression. By Theorem 2, such an arrangement exists. Let us denote the arrangement by P. Now, remove from P, and denote the resulting sequence as . Note that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression, that is .

Suppose . Let . Then, it avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression, that is . Now, remove from Q, and denote the resulting sequence as . Thus, avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression, that is . □

Lemma 1.

Let for some real numbers . Then, the sequence contains a k-term monotone arithmetic progression if and only if contains a k-term monotone arithmetic progression.

Proof.

It is sufficient to show that if contains a k-term monotone arithmetic progression, then contains a k-term monotone arithmetic progression. Let be such that is a k-term monotone arithmetic progression. Therefore,

for some real number d. This implies that:

Hence, is a k-term monotone arithmetic progression. □

Let be the smallest integer such that and be the largest integer such that .

Theorem 3.

Let . For each integer n with , there is an arrangement of that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression.

Proof.

By Corollary 1, this theorem is true for . Now, we may assume . We also assume that the theorem is true for all such that . Let where and are odd and even integers, respectively. Note that and . Note that:

Since , by assumption, the theorem is true for . Let be an arrangement of that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression. Furthermore, let be an arrangement of that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression. We claim that:

is an arrangement that avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression. In fact, if is a k-term monotone arithmetic progression in P, then . Let:

Since , one of the where must contain at least two elements. Thus, d is even. If both and are nonempty, then there is a such that and . Now, is odd, a contradiction. Hence, for at most one . If , then by Lemma 1, contains a k-term arithmetic progression, a contradiction. Similarly, if , then contains a k-term arithmetic progression. Hence, P avoids k-term arithmetic progressions, but contains a -term arithmetic progression. □

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.A.S. and K.B.W.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.S. and K.B.W.; writing—review and editing, K.A.S. and K.B.W.; funding acquisition, K.A.S. and K.B.W. All authors read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) Grant Number FRGS/1/2020/STG06/SYUC/03/1 by Malaysia Ministry of Higher Education and Publication Support Scheme by Sunway University, Malaysia.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Davis, J.A.; Entringer, R.C.; Graham, R.L.; Simmons, G.J. On permutations contains no long arithmetic progressions. Acta Arith. 1977, 34, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidorenko, A.F. An infinite permutation without arithmetic progressions. Discret. Math. 1988, 69, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geneson, J. Forbidden arithmetic progressions in permutations of subsets of the integers. Discret. Math. 2019, 342, 1489–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landman, B.; Robertson, A. Ramsey Theory on the Integers, 2nd ed.; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- LeSaulnier, T.D.; Vijay, S. On permutations avoiding arithmetic progressions. Discret. Math. 2011, 311, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sharma, A. Enumerating permutations that avoid three term arithmetic progressions. Electron. J. Comb. 2009, 16, #R63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correll, B., Jr.; Ho, R.W. A note on 3-free permutations. Integers 2017, 17, #A55. [Google Scholar]

- Bachet, C.-G. Problèmes Plaisants & Délectables Qui se Font par les Nombres; Gauthier-Villars: Paris, France, 1884. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).