Abstract

We consider a cooperative packing game in which the characteristic function is defined as the maximum number of independent simple paths of a fixed length included in a given coalition. The conditions under which the core exists in this game are established, and its form is obtained. For several particular graphs, the explicit form of the core is presented.

1. Introduction

In this paper, we study cooperative games on a graph in which the vertices represent the players, and the characteristic function is defined using the maximum packing of the graph by connected coalitions. Simple paths in the graph are considered coalitions.

In particular, coalitions can be pairs of vertices connected by edges. In real life, there are many examples of paired relationships: supplier–customer, man–woman, predator–prey, source–sink, and so forth. Moreover, agents can interact with each other via vehicles, mobile devices, or social networks, forming paired communications. For example, in a mobile network, the vertices of the corresponding graph represent mobile devices, and the connections between them occur within the network coverage. In practice, it is important to find the maximum load on a mobile network under which any two devices can simultaneously communicate with one another. In sociology and various TV shows, it is important to divide the participants into the maximum number of pairs (see, for example, the popular show “Speed Dating”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speed_dating (accessed on 10 July 2021); https://www.imdb.com/find?q=speed+dating&ref_=nv_sr_sm (accessed on 10 July 2021). The same problems arise in electrical and radio networks or the physics of magnetic structures of solid crystals.

The maximum packing is not necessarily realized through pairs of connected vertices. For example, simple paths of a fixed length can be chosen as packing coalitions. Such problems arise when laying fiber-optic lines to connect urban areas to the Internet. Another application is the development of transportation networks in a city or between cities. The network packing determines a partition of the set of players into coalitions. After defining the characteristic function, an imputation can be found to rank the graph vertices by their value for organizing links in the network or transmitting data, depending on the problem under consideration.

In the papers [1,2], a general class of such cooperative games was formulated and called combinatorial optimization games. This class includes packing games as well. In such games, the characteristic function is defined as follows. Let a matrix of zeros and ones, and integer vector c be given. The value of a coalition is a solution of the integer linear programming problem

where the matrix is a submatrix of A with the columns from the set K. This problem is known as the set packing problem [3]. In a similar form, such games were investigated in [4] as linear production games. In the cooperative game of this type, the core (if itexists) is a solution of the dual problem. The balancedness (non-emptiness of the core) of the cooperative game is closely related to solving both problems. As some applications, games with maximum flows on a graph, and graph packing games with pairs of connected vertices, were considered.

In packing games, other allocation principles can be adopted as imputations. Since the cooperative game is defined on a graph, the most natural approach to determine the significance of a particular graph vertex is the Myerson value [5,6]. In the papers [7,8], the Owen value [9,10,11] was used as an allocation principle in the cover game. In the paper [12], the nucleolus was proposed, including an algorithm for its construction. The paper [13] was dedicated to the Shapley value: its properties were investigated and an algorithm for calculating this value was proposed.

There are other games related to packing undirected graphs. For example, in graph coloring problems, the chromatic number of a graph can be taken as the characteristic function [1,14,15,16]. Graph clustering problems can be treated as cooperative games with a Nash stable coalition partition when none of the players benefit from changing the coalition structure. In this case, the Myerson value is used as an allocation principle; see [17,18].

In packing by pairs of connected vertices, two approaches to graph packing problems are well known: vertex cover and edge cover [1,19]. A vertex cover of a graph is any subset U of its vertex set N, such that any edge of this graph is incident to at least one vertex of the set U. Here, the characteristic function is defined using the vertex cover with the minimum number of vertices (the so-called minimum vertex cover of the graph). Given an edge cover, the characteristic function is defined as the maximum number of edges in a graph without shared vertices.

This paper deals with cooperative games on graphs in which the characteristic function is defined as the maximum number of independent simple paths of a fixed length. Note that we are interested in the paths without shared vertices. This feature distinguishes the current statement from the cooperative game in which the characteristic function is defined as the number of all simple paths of a fixed length. The latter definition of a game is often used for determining the centrality of graph vertices.

Here, it will be convenient to use “graph packing” for referring to the coalitions (paths) included in a corresponding coalition partition. The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: In Section 2, we define a cooperative packing game. Section 3 considers the graph packing problem with pairs of connected vertices. In Section 4, these results are extended to the general case. Section 5 presents the explicit-form solution of the cooperative graph packing game for several particular graphs.

2. Basic Definitions

Let be the set of players. A subset is called a coalition. Consider a cooperative game .

Definition 1.

A coalition K is said to be winning if .

Definition 2.

A coalition K is said to be minimal winning if and .

Definition 3.

A coalition partition of the players set N is a set satisfying the following conditions:

We denote by an element of a coalition partition containing player i. Further analysis will be confined to effective coalition partitions.

Definition 4.

An effective coalition partition of the set N is a partition in which the number of minimal winning coalitions is the maximum.

According to this definition, an effective coalition partition has minimal winning coalitions and players not belonging to the minimal winning coalitions. For the sake of convenience, assume that these players act independently, that is, form coalitions of one player. Therefore, an effective coalition partition can be written as , where are the minimal winning coalitions, and are individual players acting independently.

Consider an undirected graph , in which N and E are the sets of players and edges, respectively. Consider a new cooperative game , defining the characteristic function as the maximum number of minimal winning coalitions:

where . A solution of the cooperative game is an imputation.

Definition 5.

An imputation in the cooperative game Γ is a vector , such that

For the given characteristic function, we will adopt the core as an allocation principle.

Definition 6.

In the cooperative game with the characteristic function the core is the set of imputations

This paper deals with cooperative games on graphs in which minimal winning coalitions are defined as simple paths of a fixed length . For a graph G, a sequence of distinct vertices is a simple path connecting vertices and , if for all , . The length d of a path is the number of edges in it: . The length of the shortest path connecting vertices i and j is called the distance between i and j. A graph G is said to be connected if there is a path in G connecting any two vertices i and

Thus, in an effective coalition partition

the minimal winning coalitions represent simple paths of a length d in the graph G, and are separate vertices not included in these paths. A set will henceforth be called graph packing, and the corresponding game on the graph the packing game.

First, we study packing games in which the minimal winning coalitions are of the form where is an edge in the graph G.

3. Graph Packing Game with Pairs of Connected Vertices (Maximum Matching Game)

Consider a cooperative game where denotes the set of players, and is a graph with N as the vertex set and E as the edge set. The notation will also be used for a subgraph of the graph G defined on a vertex subset .

We define the characteristic function for a coalition as the maximum number of edges included in K without shared vertices (also called a maximum cardinality matching) [20]. This characteristic function is monotonic and superadditive. Let us demonstrate that is not necessarily a convex function. Recall that convexity means that the inequality holds for all and .

Example 1.

Consider and . For and we have

At the same time,

Thus, the function v is not convex.

The vertices of degree 1 in the graph G will be called terminal and the vertices adjacent to them preterminal. We denote these sets by and , respectively. In addition, an edge connecting terminal and preterminal vertices will be called terminal. By a packing of the graph G we mean a set of edges on which is achieved. The set of all packings will be denoted by . The set may be non-unique and composed of several sets.

Example 2.

Consider and . Then is unique. If , there are two such sets:

.

The set of vertices forming the edges from a packing will be denoted by . We emphasize that the packing game definition implies

Let us explore the core’s properties in the graph packing game. First of all, the core does not necessarily exist.

Lemma 1.

Let G be an arbitrary connected graph such that the set of terminal vertices is non-empty. Then among all packings, there exists a packing with the following property:

Proof.

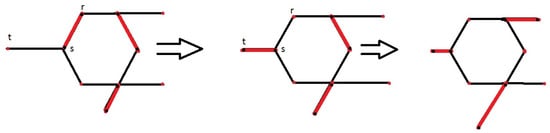

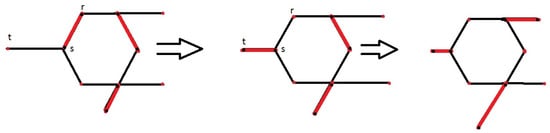

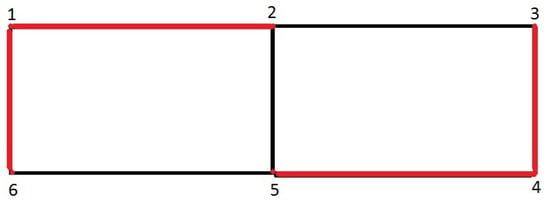

Consider an arbitrary packing . Assume that, in the graph there is a preterminal vertex s without a pair among the terminal vertices in That is, , where (Figure 1). We take an arbitrary edge if s is connected to another non-terminal edge r in we replace the link with a new link . The new packing will be denoted by . It is important that |. We perform the same procedure for all such vertices finally obtaining a packing with the property (2). □

Figure 1.

Covers of graph G.

Lemma 2.

Let G be an arbitrary connected graph such that the set of terminal vertices is non-empty. In addition, let be the set of all neighbors of a vertex in the terminal set, and be a subgraph of G defined on the vertex set . Then

Proof.

According to Lemma 1, for any , such that , there exists a packing such that , where (Figure 2). Then . Let and be a subset on . Then, , but is a set of independent edges in , then .

Figure 2.

Terminal vertices in graph.

Let be a packing of . Then, Let , then , but is a set of independent edges in G, then . Consequently, . □

Lemma 3.

Condition (1) for the core is equivalent to

Proof.

Assume that condition (1) holds for some x. Then the inequality is satisfied for all coalitions S and, particularly, for a coalition , where .

Now, assume that an imputation x satisfies (3). Consider an arbitrary coalition . Let a packing of the graph be composed of k edges, that is,

Remark 1.

Note that condition (1), like (3), may not hold, meaning that the core is empty. The balancedness of this cooperative game can be established by solving the linear programming problem,

If the solution of this problem satisfies , then the game is balanced; otherwise, unbalanced.

Lemma 4.

If x belongs to the core, then .

Proof.

By definition, we have , where the cover is composed of k edges . According to Lemma 3, . If at least one element is , then the entire sum becomes

which contradicts the condition . □

Note that the same contradicting inequality (5) will be derived by assuming for some edge from the cover . The proof is complete.

Lemma 5.

Let the core be non-empty and x belong to the core. In addition, let be some cover. Then for any edge ; for all vertices l outside the cover, .

Lemma 5 leads to the following unbalancedness condition for the cover game.

Corollary 1.

Let be the set of all vertices that do not simultaneously belong to all covers of the graph G. If the subgraph has at least one edge, then the core in the cover game is empty.

Proof.

Assume that the core is non-empty. Let be an edge in the subgraph . Due to Lemma 5, we obtain . However, according to Lemma 3, . This contradiction completes the proof. □

Corollary 2.

Let the core be non-empty, and let be the set of all vertices that do not simultaneously belong to all covers of the graph G (Corollary 1). In addition, let be the set of all vertices adjacent to those from . Then for all

Proof.

Let . According to Lemma 3, we have for an edge . On the other hand, due to Lemma 5, . Therefore, , and by Lemma 4, . This finally yields . □

Corollary 3.

Let G be a connected graph and n be an odd number. In addition, let the core be non-empty and x belong to the core. Then and .

Proof.

Since the cover of G is composed of an even number of vertices, the set is non-empty. For any . We take a vertex j adjacent to vertex i. According to Corollary 2, . □

Lemma 6.

Let a graph G have an even number of vertices, and . Then the core is non-empty. Moreover, belongs to the core.

Proof.

Consider a cover It has the form being composed of k edges. Letting , we obtain for any edge of the cover Due to Lemma 3, x belongs to the core. □

Lemma 7.

Let G be a connected graph and t be a pendant vertex. In addition, let be a vertex adjacent to t. If the core in the cover game on the subgraph is non-empty (empty), then the core in the cover game on the graph is non-empty (empty, respectively) as well.

Proof.

For a terminal vertex t there exists a cover such that (Lemma 1). Consequently,

Assume that in the game on the subgraph the core is non-empty, and belongs to the core. According to Lemma 3, for all edges . Since vertex t is connected to vertex s only, the imputation satisfies inequalities (3). Hence, belongs to the core in the game on the graph G.

Now let the game on the subgraph have an empty core. In this game, the system of inequalities for all edges will therefore contradict the condition . In the game on the graph the core needs to satisfy the additional condition meaning that the system of inequalities (3) will also contradict

due to (6).

Here, is a corresponding element of the adjacency matrix of the graph G.

Its dual problem has the form

In (7), a variable is associated with each edge of the graph For any pairs not representing edges, . Thus, problem (7) contains non-zero variables.

Theorem 1

Example 3.

4. Graph Packing Game with Simple Paths of Length d > 2

Now consider a cooperative game , in which the characteristic function for a coalition is defined as the maximum number of simple paths of a fixed length d included in K without shared vertices. This characteristic function is monotonic and superadditive as well.

A set of disjoint simple paths of a length d, on which is achieved, will be called a packing of a graph The set of all packings will be denoted by . The set may be non-unique and composed of several sets.

The set of vertices forming paths from a packing will be denoted by . We emphasize that the packing game definition implies

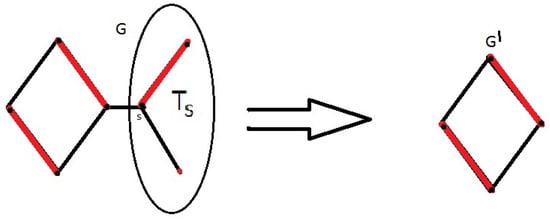

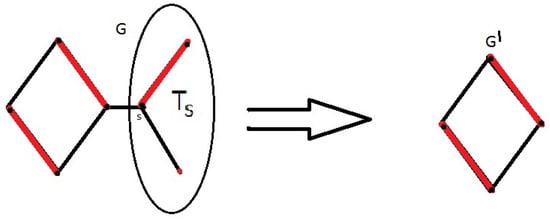

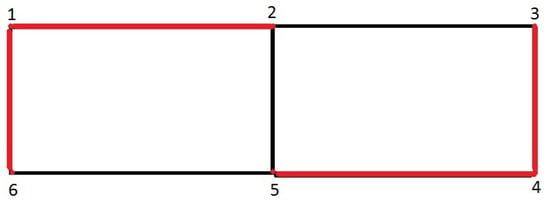

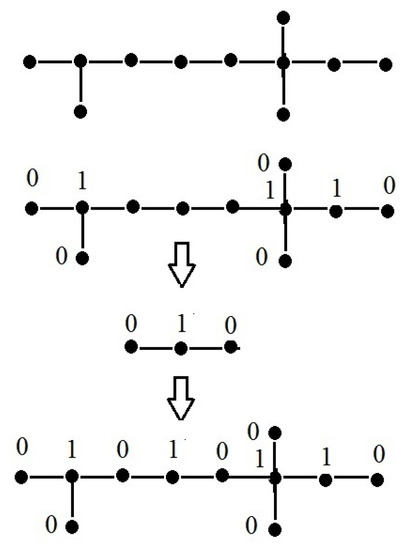

Example 5.

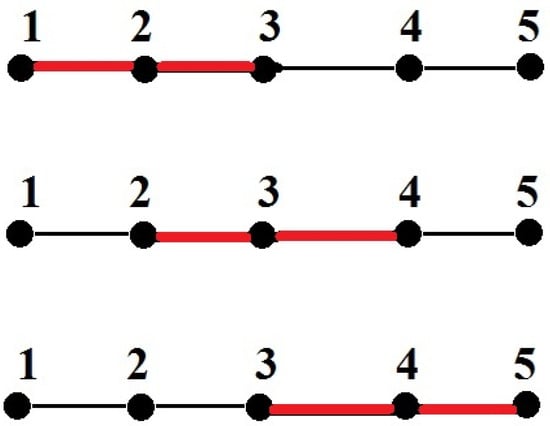

Consider a packing game on a graph , where and (Figure 3), and let . Then the packings are the coalition partitions , and .

Figure 3.

Graph packing by vertex triplets.

Lemma 8.

Let the core be non-empty and x belong to the core. In addition, let be some packing. Then for any path ; for all vertices j outside the packing, .

Proof.

Let . Then and since , the existence condition of the core (1) implies . The effectiveness condition has the form . On the other hand, . This non-strict inequality turns into equality if and only if and . □

Lemma 9.

Let the number of vertices in a graph G be a multiple of the packing path length and . Then the core of G is non-empty, and the point belongs to the core.

Proof.

Assume that is the optimal packing of G composed of k disjoint paths of the length d. Letting , we obtain (the effectiveness condition holds) and (the inequality constraints over all possible paths are satisfied as equalities). Thus, the point belongs to the core of G because it satisfies the appropriate requirements. □

Lemma 10.

Let L be the set of paths of a fixed length d in the graph G. Then condition (1) for the core is equivalent to

Proof.

Assume that condition (1) holds. By the definition of , we have , and consequently, .

Now assume that condition (8) holds. Consider an arbitrary coalition S. If , then the coalition S contains k disjoint simple paths of the length each satisfying the inequality As a result, . □

Remark 2.

Notice that the number of constraints for the core drops from exponential () to at most , which is polynomial in n for a fixed d.

We denote by L the set of all simple paths of a fixed length d in the graph G. With each simple path of the length d in the graph G we associate a row vector , where for and for other We compile the matrix from the rows

Consider the linear programming problem:

The constraints can be written in the matrix form:

With each path we associate the variable

For problem (9), the dual problem is given by:

Both problems—the primal (9) and dual (10) problems—have admissible solutions. Therefore, there exist optimal solutions whose values coincide. Problem (10) contains n constraints, that is, there are no more than n non-zero variables in the solution.

Theorem 2.

Proof.

Notice that the problem of maximum packing of the graph G can be presented as the integer linear program

So, if the optimal solution of the problem (10) is an integer then it gives some optimal packing of the graph. with optimal value . Then, a solution of primal linear problem (9) x will satisfy the conditions:

and the optimal value be equal to

From Lemma 10, it yields that x is in the core. Hence, the sufficiency of the statement follows.

Now assume that the core is not empty. According to Lemma 10, for x from the core: and , for all simple paths of length d. According to the conditions of the problem, is the maximum packing in the graph G. So, is integer and a packing exists, such that . This packing gives a corresponding solution of the integer linear program (11). By the duality property of linear programming, this solution is an integer optimal solution of the linear program (10). It proves the necessity of the statement. □

Example 6

(continued).Let and the links be described by the graph in Figure 3. A solution of problems (9) and (10) is . The values of both linear programming problems coincide, being equal to 2. The solution of the dual problem is indicated by red edges: the optimal packing is . Other solutions of (9) are: , , .

5. Examples of Graph Packing

5.1. Chain Graphs

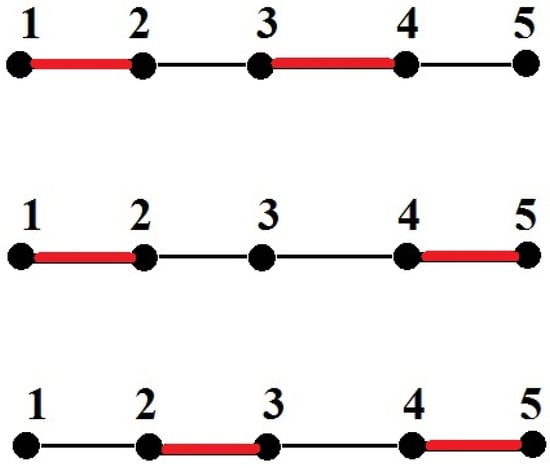

5.1.1. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Chain Graph with Odd Number of Vertices

Let and be a chain graph, that is, . Then and there are packings of the following configuration. First, all vertices with even numbers are included in all these packings. Second, each vertex with odd numbers is not included in some packing. According to Lemma 5, for all odd numbers Hence, by Corollary 2 of Lemma 5, for all even numbers The resulting solution satisfies the effectiveness condition:

Therefore, the core exists and is composed of the unique point (singleton). See Figure 4.

Figure 4.

There are three possible packings of by pairs. According to Lemma 8, . Moreover, , so . There is only unique point in the core: .

5.1.2. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Chain Graph with Even Number of Vertices

Let and be a chain graph. Then and the unique packing has the form . The core of this game is non-empty and contains an infinite set of points, for example, the straight-line segment connecting the points (0, 1, …, 0, 1) and (1, 0, …, 1, 0) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

There is only unique packing of by pairs.

5.1.3. Packing by Vertex Triples

Let and be a chain graph. Then and the packing is composed of the set . The core is non-empty. For example, it contains the convex hull of the points , and .

For the chain graph . The packing is composed of the set . The core is non-empty and contains, for example, the straight-line segment connecting the points and .

For the chain graph . The packing is composed of the set . The core is composed of the unique point (singleton). See Figure 6.

Figure 6.

There are three possible packings of by triples. According to Lemma 8, . Moreover, , so . There is only unique point in the core: .

5.2. Cycle Graphs

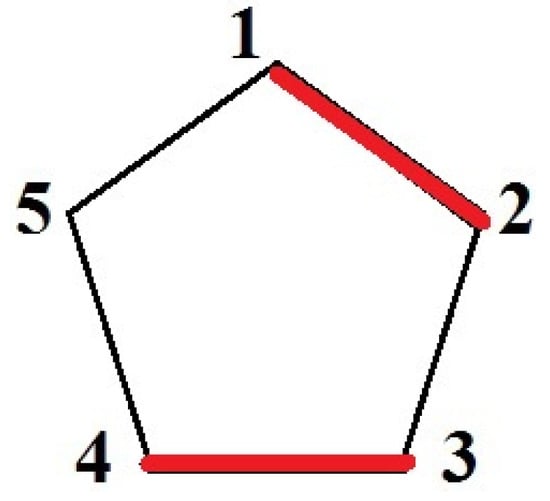

5.2.1. Parking by Vertex Pairs. Cycle Graph with Odd Number of Vertices

Let and be a cycle graph, that is, . Then , and there are packings of this graph. First, one of the vertices is not included in any packing. Second, each vertex from N is not included in some packing. According to Lemma 5, which contradicts the effectiveness condition . Hence, the core of the graph is empty (see Figure 7).

Figure 7.

: by “rotating” the packing set, one can see that each vertex is not included in some packing. So, , which contradicts condition .

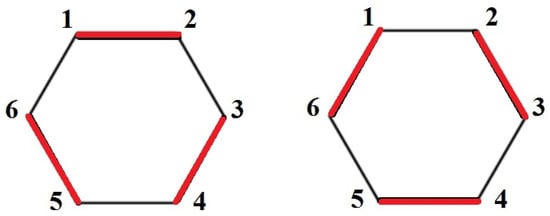

5.2.2. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Cycle Graph with Even Number of Vertices

Let and be a cycle graph. Then and there are two packings only. According to Lemma 6, the core of the graph G is non-empty: it contains at least the point but this point is not the only one.

In this case, the system of constraints (3) for the core reduces to . Summing all inequalities and dividing the resulting expression by 2 gives . This inequality will not contradict the equality if and only if it turns into equality. To this effect, all inequalities must hold as equalities: . Letting we obtain . Hence, the core of the graph has the form . See Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Two packings of . All vertices are in the packing.

5.2.3. Packing by Vertex Triples. Cycle Graph

Let and be a cycle graph of length 3. Then and there are three packings, , , and . According to Lemma 8, this case generates the system of equations . Its solution is defined by two degrees of freedom: , for example: and . The core is non-empty.

Now let and be cycle graphs of some length not representing a multiple of 3. Then in both cases, Some vertex is not included in any packing, and each vertex is not included in some packing. According to Lemma 8, , which contradicts the effectiveness condition . Hence, the core is empty (see Figure 9).

Figure 9.

: by “rotating” the packing set, one can see that each vertex is not included in some packing, so , which contradicts condition .

5.2.4. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Hamiltonian Cycle

Let and the graph G contain the Hamiltonian cycle . Then . We compare the systems of constraints (3) describing the cores for G and . In both cases, the same equality constraint appears, corresponding to the effectiveness condition. The system of inequality constraints for G includes all inequality constraints for plus some additional ones. As mentioned above, the core of is empty. Therefore, the core of G is empty as well.

5.3. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Trees

Using mathematical induction, we will demonstrate that the core of the tree is non-empty. Obviously, the core of the trivial graph i is non-empty (equal to 0). The core of the graph is also non-empty: it coincides with the straight-line segment connecting the points and . Assume that for all trees with at most k vertices, the core is non-empty. Let be a tree with vertices. There are pendant vertices in G. Removing any of the pendant vertices t and the adjacent one s, we pass to the graph , which is a tree or a forest. According to Lemma 7, the conclusions about the existence of the core in G and are the same. By the induction hypothesis, the core of is non-empty. Hence, the core of G is non-empty as well. We can easily describe the procedure for finding a point from the core. If is a pendant vertex, and is the adjacent vertex for t, then we pass to the graph , letting , , and so forth. If the graph splits into connected components, we apply this procedure for each component separately. See Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Finding a point in the core.

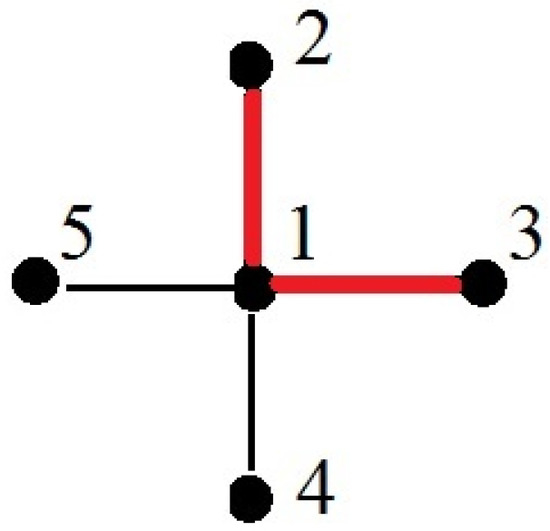

5.4. Packing by Vertex Triplets. Star Graph

Let and G be a star graph, that is, . Then and there are packings, each composed of vertex 1 and two elements from the set . Moreover, some vertices from are not included in any packing; each vertex from is not included in some packing. According to Lemma 8, and consequently, . The point is the unique one belonging to the core (see Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Star graph, . When the graph is rotated, each vertex of the graph except vertex 1 is not included in some packing, so . yields .

5.5. Complete Graphs

5.5.1. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Complete Graph with Odd Number of Vertices

Let and G be a complete graph. Then . The complete graph contains a Hamiltonian cycle, so that is a subcase of Section 5.2.4. Hence, the core of the graph is empty.

5.5.2. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Complete Graph with Even Number of Vertices

Let , where and G are complete graphs. Then and by Lemma 6, the core contains the point . Consider the system of constraints (3) describing the core. This system includes the equality and inequalities of the form . Summing all these constraints and dividing the resulting expression by gives . This condition holds only if all inequality constraints from (3) are equalities, that is, . It yields . Assuming that , we obtain and, consequently, . Analogously, the case . Therefore, the core is composed of the unique point .

5.5.3. Packing by Vertex Triplets. Complete Graph with Number of Vertices Multiple of 3

Let and G be a complete graph. Then and the set of packings has the following configuration. First, all vertices are included in each packing; second, any vertex triplet is included in some packing. Consequently, all admissible vertex triplets satisfy the equality . This system has the unique solution . For example, from , it follows that and, in a similar way, . So, the core is non-empty and is composed of the unique point (singleton) .

Now let or and let G be a complete graph. Then in both cases, and the set of optimal packings has the following configuration. First, some vertices are not included in all packings. Second, each vertex is not included in some packings. According to Lemma 8, , which contradicts the effectiveness condition . Hence, the core is empty.

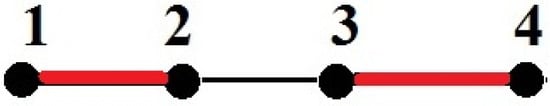

5.6. Complete Bipartite Graphs

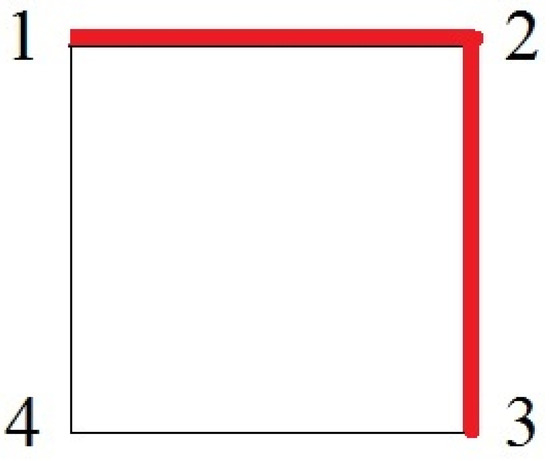

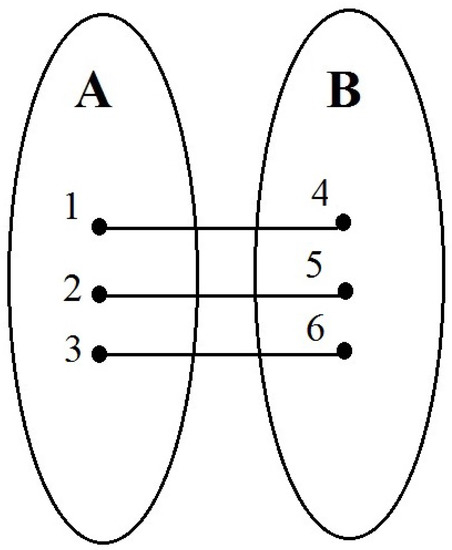

5.6.1. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Same Number of Vertices in Graph Parts

Consider the bipartite graph . Then and there are packings, each composed of all vertices. We renumber the vertices of G so that the graph parts are composed of the sets and .

Then, condition (3), under which a point belongs to the core, reduces to , . However, and this non-strict inequality must hold as equality. (Otherwise, it will contradict the effectiveness condition.) The equality is the case if and only if and . Hence, the core has the form (see Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Each vertex is at any packing.

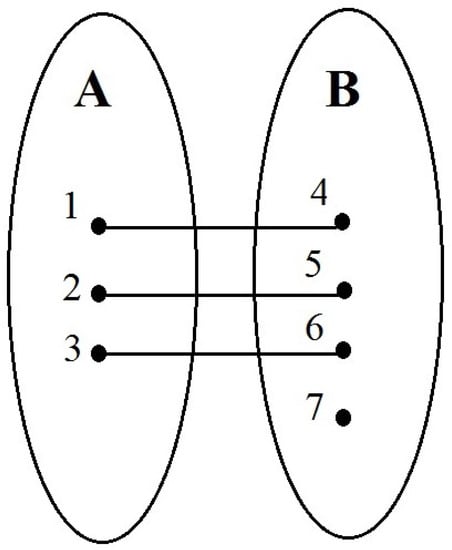

5.6.2. Packing by Vertex Pairs. Different Number of Vertices in Graph Parts

Consider a graph , where . Then and there are packings of the following configuration. First, all m vertices from the smaller part and some m vertices from the greater part are included in each packing. Second, each vertex from the greater part is not included in some packings. According to Lemma 5, the components are 0 for all vertices from the greater part. Due to Corollary 2 of Lemma 5, the components are 1 for all vertices from the smaller part. Consequently, (see Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Each vertex from B is not included in some packings, so , and .

5.7. Zachary’s Karate Club Network

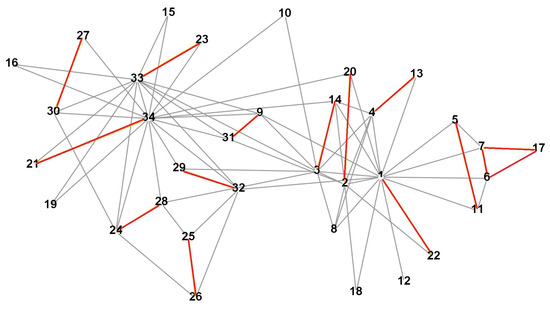

Consider the packing game for the well-known Zachary’s karate club network [21]. The graph of this network (Figure 14) describes the relations among 34 karate club members. There are 77 edges in total. The principal persons of the network are vertices 1 and 34.

Figure 14.

Packing by pairs for Zachary’s karate club network.

First, we analyze the packing by pairs case. The primal problem (4) has the solution

and the optimal value is 13.5.

The solution of the dual problem (7) is given by

the other variables being equal to 0. In Figure 14, the packing corresponding to the nonzero variables is indicated by the red color. The optimal values of both problems are the same and are equal to 13.5. This game is unbalanced, and the core is empty. This result can be established directly using the lemmas provided above. There is a pendant vertex 12 in the graph. According to Lemma 7, we remove vertex 12 and its adjacent vertex 1. (The conclusions regarding the existence of the core in the original and resulting graphs will coincide.) The graph obtained by removing vertices 1 and 12 splits into two connected components, one of which contains five vertices. They are connected by the Hamiltonian cycle 5-7-17-6-11-5. Hence (see Section 5.2.4), the core of this graph is empty. This means that the core of the original graph is empty as well.

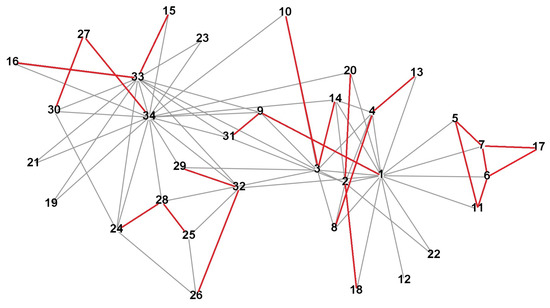

Now, consider the packing game with paths of length 3 (triplets) for this graph. The primal problem (9) have the solution:

and the optimal value is .

The solution of the dual problems (10) is given by

the other variables being equal to 0. In Figure 15, the cover corresponding to the nonzero variables is indicated by the red color. The optimal values of both problems coincide and are equal to . This game is also unbalanced, and the core is empty.

Figure 15.

Packing by triplets for Zachary’s karate club network.

6. Conclusions

Important aspects in the structural analysis of networks include determining the centrality of graph vertices and the clustering of graphs, that is, identifying their most connected components. The centrality of a vertex estimates its significance for the entire network, in some sense reflected by the characteristic function. For example, if we are interested in the number of descendants, the characteristic function is the number of all edges of the graph belonging to a given coalition. If we are interested in the dissemination of information or the propagation of epidemics through a network, the characteristic function is the number of simple paths of various lengths in a given coalition.

In this paper, the characteristic function has been defined as the maximum number of disjoint simple paths of a fixed length. In a sense, this is also a centrality measure for graph vertices, which describes their significance when covering the network by independent paths of a fixed length. Possible applications include the design of telecommunications or transportation networks.

The corresponding cooperative game has been considered using the core as an optimality principle. As has been demonstrated, in this case, the graph packing problem is solved (and the centrality of graph vertices is determined) by solving primal and dual linear programming problems of a special form. Even if the game is unbalanced (the core is empty), the solution of the two linear programming problems always exists, makes sense, and can be used in practice.

The authors wish to thank the anonymous referees for their valuable suggestions which have improved the presentation of this paper.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.D. and V.M.; methodology, S.D. and V.M.; software, S.D. and V.M.; validation, S.D. and V.M.; formal analysis, S.D. and V.M.; investigation, S.D. and V.M.; resources, S.D. and V.M.; data curation, S.D. and V.M.; writing—original draft preparation, S.D. and V.M.; writing—review and editing, S.D. and V.M.; visualization, S.D. and V.M.; supervision, S.D. and V.M.; project administration, S.D. and V.M.; funding acquisition, V.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (grant no. 17-11-01079).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Deng, X.; Ibaraki, T.; Nagamochi, N. Algorithmic aspects of the core of combinatorial optimization games. Math. Oper. Res. 1999, 24, 751–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Ibaraki, T.; Nagamochi, N. Totally balanced combinatorial optimization games. Math. Program. (Ser. A) 2000, 87, 441C452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S. Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; W.H. Freeman and Company: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, G. On the core of linear production games. Math. Program. 1975, 9, 358–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, M.O.; Wolinsky, J. A strategic model of social and economic networks. J. Econ. Theory 1996, 71, 44–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myerson, R.B. Graphs and cooperation in games. Math. Oper. Res. 1977, 2, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajir, M.; Langar, R.; Gagnon, F. Coalitional games for joint co-tier and cross-tier cooperative spectrum sharing in dense heterogeneous networks. IEEE Access 2016, 4, 2450–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazalov, V.V.; Gusev, V.V. Generating functions and Owen value in cooperative network cover game. Perform. Eval. 2020, 144, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamiache, G. The Owen value values friendship. Int. J. Game Theory 2001, 29, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owen, G. Values of games with a priori unions. In Mathematical Economics and Game Theory; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1977; pp. 76–88. [Google Scholar]

- Puente, M.; Gimenez, J. A new procedure to calculate the Owen value. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Operations Research and Enterprise Systems, Porto, Portugal, 23–25 February 2017; pp. 228–233. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, X.; Fang, Q.; Sun, X. Finding nucleolus of flow game. J. Comb. Optim. 2009, 18, 64–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusev, V.V. The vertex cover game: Application to transport networks. Omega 2020, 27, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bietenhader, T.; Okamoto, Y. Core stability of minimum coloring games. Math. Oper. Res. 2006, 31, 418–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Q.; Kong, L.; Zhao, J. Core stability of vertex cover games. Internet Math. 2010, 5, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Okamoto, Y. Submodularity of some classes of the combinatorial optimization games. Math. Methods Oper. Res. 2003, 58, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazalov, V.V.; Trukhina, L.I. Generating functions and the Myerson vector in communication networks. Discret. Math. Appl. 2014, 24, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avrachenkov, K.E.; Kondratev, A.Y.; Mazalov, V.V.; Rubanov, D.G. Network partitioning algorithm as cooperative games. Comput. Soc. Netw. 2018, 5, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakostas, G. A better approximation ratio for the Vertex Cover problem. ACM Trans. Algorithms 2009, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, J. Paths, trees and flowers. Can. J. Math. 1965, 17, 449–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachary, W.W. An information flow model for conflict and fission in small groups. J. Anthropol. Res. 1977, 33, 452–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).