Abstract

Public announcement logic is a logic that studies epistemic updates. In this paper, we propose a sound and complete labelled natural deduction system for public announcement logic with the common knowledge operator (PAC). The completeness of the proposed system is proved indirectly through a Hilbert calculus for PAC known to be complete and sound. We conclude with several discussions regarding the system including some problems of the system in attaining normalisation and subformula property.

1. Introduction

An agent’s knowledge over a proposition may be updated when new information is given. Public announcement logic (PAL) is a logic that formalises the notion of this epistemic updates. The common knowledge operator on the other hand is an operator that attempts to formalise the notion of common or mutual knowledge among a group of agents. One can understand the common knowledge of proposition A as everyone knowing that A, everyone knowing that everyone knowing that A, and so on ad infinitum. The interaction between public announcement and common knowledge helps us understand the dynamic of (common) knowledge of a group in social interaction. One significant implication of understanding the dynamic of (common) knowledge may be realised in cryptography, particularly cryptographic protocol, as the information in a protocol is dynamic and the common knowledge of a piece of information between, say, two agents might be required to be achieved in a protocol.

We assume here that public announcement logic with common knowledge (PAC) is a multi-modal extension of the modal logic S5 and that an announced formula is always true. Several proof systems have been proposed for PAL: a display calculus [1], sequent calculi [2,3,4], a tableau calculus [5], and a Hilbert calculus [6]. The proposed proof systems for (normal) modal logics with the common knowledge operator, on the other hand, are for example the Tait calculus of [7,8,9] and the hypersequent calculus of [10]. So far, all known proof systems for the logic with the interaction of public announcement and common knowledge are formulated as Hilbert calculi for example the Hilbert calculus for public announcement logic with common knowledge (PAC) of [6].

In this paper, we propose a labelled natural deduction for public announcement logic with common knowledge (NPAC). We begin by presenting the syntax of PAC in which there are two types of formula: labelled and relational formulas. The Kripke semantics of the logic is based on the notion of a restricted model that gives meaning to an indexed or updated formula. Then, we present the labelled natural deduction for PAC. Its soundness is proved by translating PAC into NPAC. Finally, we discuss the assumption that we made regarding the announcement being always true and some difficulties of some of the rules that are needed to be resolved for NPAC to be normalisable and to satisfy the subformula property.

2. Syntax

We assume a countably infinite set of atomic propositions a set of worlds a finite set G of agent-symbols and corresponding knowledge operators and finite set of binary relation symbols We assume also sets of agent-symbols and corresponding group knowledge operators and common knowledge operators We use the sequence notation for a set of agent-symbols for brevity and it should intuitively be understood as an occurrence-insensitive, unordered sequence of agent-symbols as it should be in a set. For example, if then instead of writing and we occasionally write and . Finally, we assume a transitive closure symbol , a falsum symbol ⊥, an implication operator ⊃, and a binary announcement operator for arbitrary basic formulas A and B defined below.

A basic formula A is defined by the following scheme

is defined as and other propositional operators are defined in the obvious manner. Besides basic formulas, there are two forms of formula in PAC: labelled and relational formulas. A labelled formula is of the form where A is a basic formula, x is a world, and is a (possibly empty) finite sequence of basic formulas. A relational formula is of the form or . here is added as an index to keep track of the world updates in the syntax. For brevity, we use “formula” for labelled or relational formulas or basic formulas Whichever the situation is, it can be easily understood by the script or the non-script font used.

3. Semantics

A Kripke model for PAC is a structure such that is a non-empty finite set of worlds, where is an equivalence relation on , and is a valuation function that for every pair of world x and atomic proposition p yields the truth value of p at x.

Let be a Kripke model and A a basic formula. A restricted Kripke model for PAC is a structure such that is a non-empty finite set of worlds, where , and . We write or simply instead of , and similarly , , and . For instance, we have if since .

Let and be the transitive closure of a relation R. Truth for a formula in a model (notation: ) is defined by main induction on the length of with side induction on the complexity of :

- iff .

- iff .

- iff .

- for every and every pair of sequences of formulas and .

- iff .

- iff implies .

- iff, for every y, implies .

- iff, for every y, implies .

- iff, for every y, implies .

- iff implies .

We say that, for a set of labelled or relational formulas and a formula , if implies for every model . We also say that, for a set of basic formulas and a basic formula A, if implies for every model and every world x in .

The following propositions will be used to establish the soundness of NPAC in Section 5.

Proposition 1.

For every Kripke model , iff .

Proof.

This can be proved via an induction over the complexity of B. We show only cases where (1) B is atomic p, (2) B is , and (3) B is . (1) iff iff . (2) iff, for every y, implies iff, for every y, implies iff, for every y, implies iff . (3) iff implies iff . □

Given the standard definition of as , we have that iff and .

Proposition 2.

For every Kripke model , .

Proof.

iff iff and iff and implies iff and iff (by Proposition 1) and iff and iff . □

Proposition 3.

- iff , , and .

- .

- iff .

- For every , .

- If and, for every , implies ) then .

- .

- For every , .

- If , implies , and for every natural number n and implies ); then, .

Proof.

1. For an arbitrary , iff iff and iff and iff , , and iff , , and . 2. Clearly, . So, . Therefore, for an arbitrary , implies implies . 3. Use Proposition 2. 4. If then . Therefore . 5. Suppose that the antecedent is true. Then, . Then or . Then or . Therefore, since implies for every , . 6. Suppose that, for an arbitrary , . Then but . So, . 7. Suppose that, for an arbitrary and an arbitrary , and . Then . Since and is the transitive closure of , then by iteration . Therefore, . 8. Suppose that, for an arbitrary , , implies , and for every natural number n and implies . So, for some relation R. If then and, by the second supposition, . If not then but . By contradiction, assume that for every natural number n, or . In other words, for every natural number n there are no and such that . Then, since is a transitive closure, . This is a contradiction. Therefore, and for some natural number n. Therefore, by the third supposition, . Hence, from either of the two cases, . □

4. Hilbert Axiomatisation

The sound and complete Hilbert calculus PAC consists of the following axioms and rules [6]:

- All propositional tautologies

- From A and , infer B

- From A, infer

- From A, infer

- From A, infer

- From and , infer

5. Labelled Natural Deduction for PAC

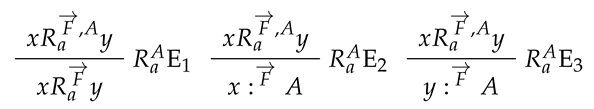

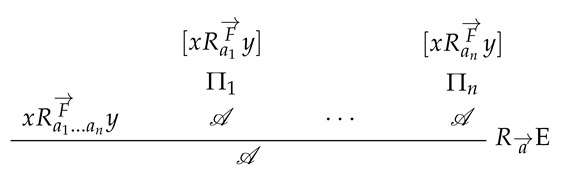

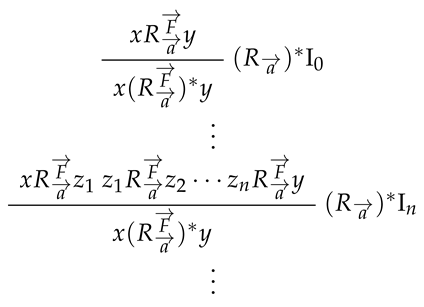

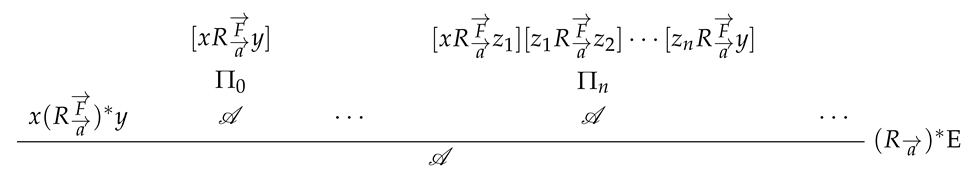

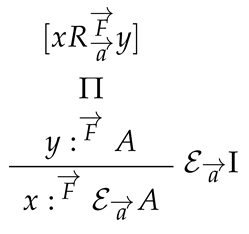

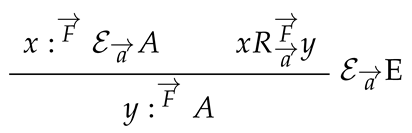

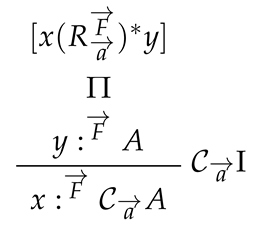

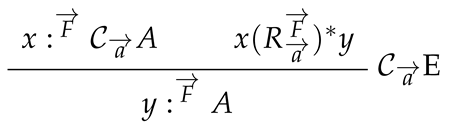

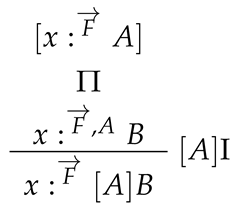

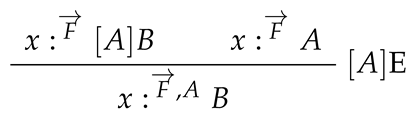

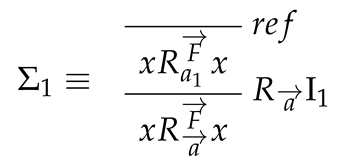

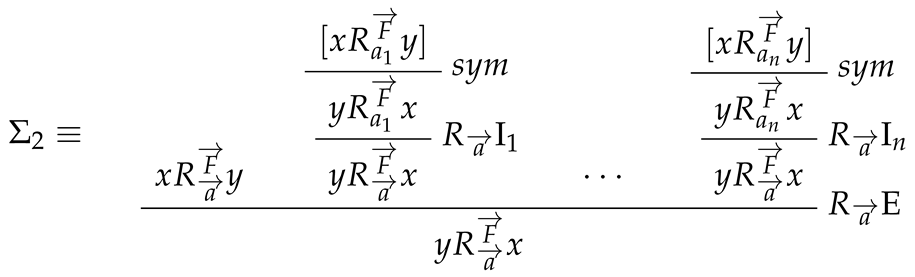

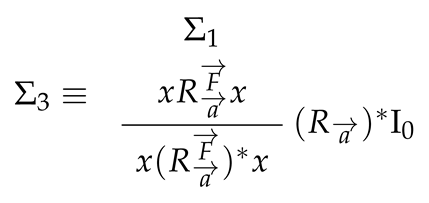

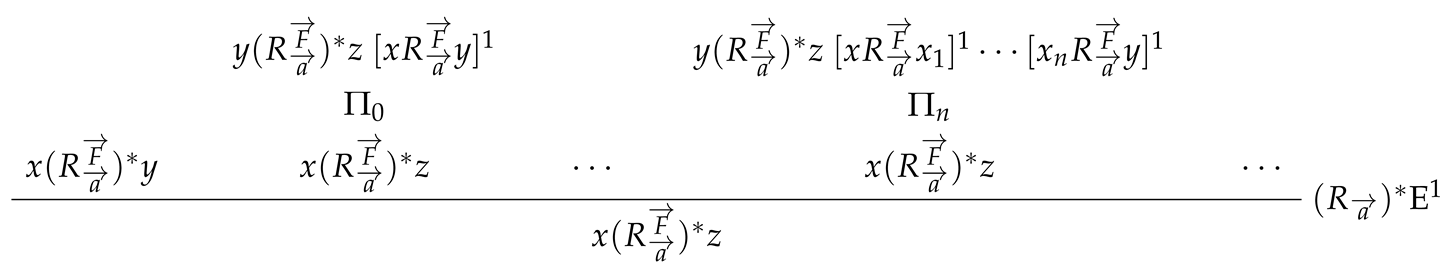

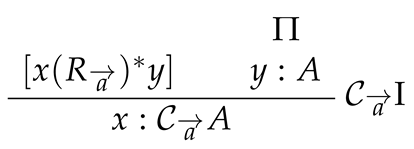

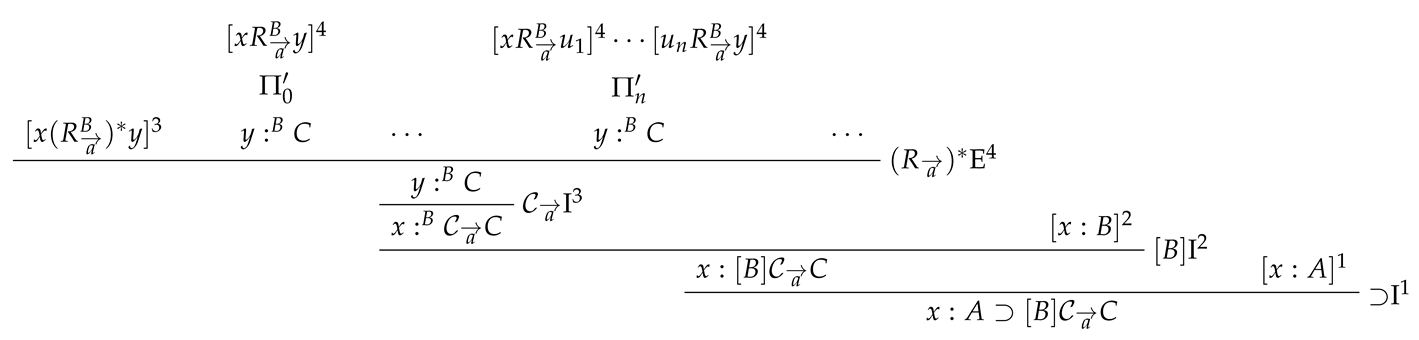

As we are internalising the worlds into the logic, we would of course want to exploit the behaviour of the relation between the worlds into NPAC from which we can introduce the common knowledge operator. While other proof systems introduce the common knowledge operator from the group knowledge operator, we want to introduce the common knowledge operator in a way that reflects the semantics where we use the transitive closure of a relation. Now, to introduce the transitive closure of a relation we can use the following property: if and only if or there exists a natural number n, and such that , and [6]. However, this is problematic since the natural number n is arbitrary. We resolve this by using infinitely many introduction rules of and a corresponding elimination rule with infinitely many minor premises. One can observe that by using infinitely many premises in the E rule in Table 1 we exhaust all possible number of worlds that connect the world x and y in a way similar to that in which we exhaust all individual constants in first-order logic by using an -rule for existential elimination.

Table 1.

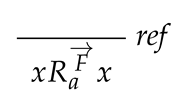

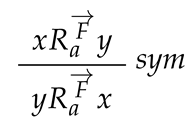

Relational rules for NPAC.

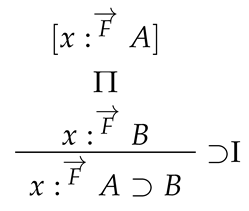

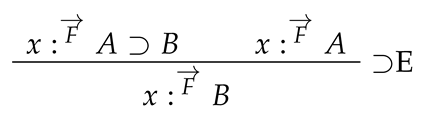

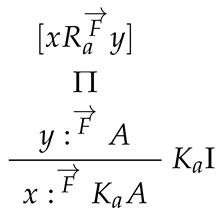

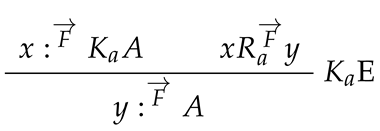

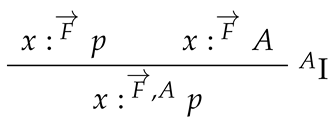

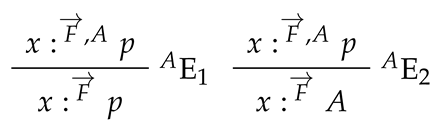

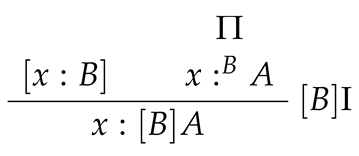

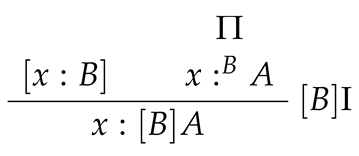

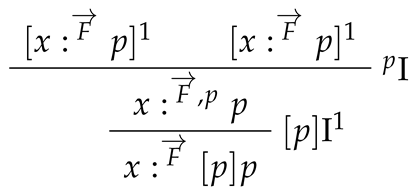

Labelled natural deduction for PAC (NPAC) consists of the rules in Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. Note that the standard introduction and elimination rules for conjunction ∧ and disjunction ∨ are derivable from those for ⊃ and ⊥ in the obvious way. In the sequel, we will make use of some of them to shorten some derivations, in particular of those for conjunction: ∧I, ∧E, and ∧E. We let p in the atom rules I, E, and E to be either a propositional formula or ⊥. To capture the arbitrariness of y, we impose y as an eigenvariable respectively in the I, I, and I rules. Similarly, we impose for every as eigenvariables in the E rule. As usual, we assume a formula in square brackets to indicate a discharged assumption. Each discharged assumption can be discharged zero or multiple times by each application of a rule. The subscript n in the symbol in Table 1 can be understood as the number of worlds that connect the world x to y.

Table 2.

Propositional rules for NPAC.

Table 3.

Modal rules for NPAC.

Table 4.

S5 rules for NPAC.

Table 5.

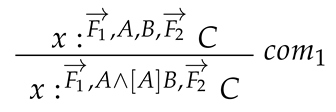

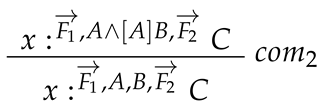

Composition rules for NPAC.

Note that has a finite number, n, of introduction rules according to the number of agents in and a corresponding elimination rule with n minor premises. On the other hand, has infinitely many introduction rules and a corresponding elimination rule with infinitely many minor premises, thereby making the derivations in the system to be trees with possibly infinitely many branches where each branch is, however, always finite in length.

We write to mean that there is a derivation of a labelled or relational formula in which all undischarged assumptions belong to the set of labelled or relational formula . One can refer to [11] for more details on the notion of derivation in natural deduction in general.

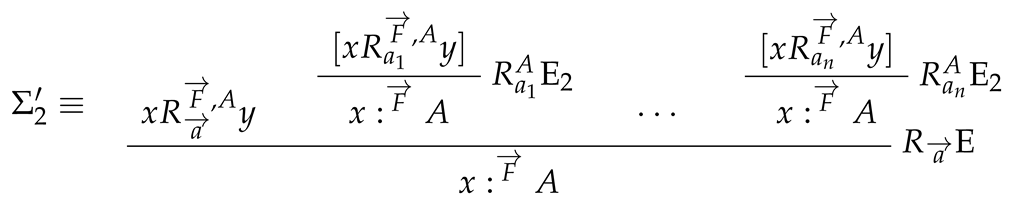

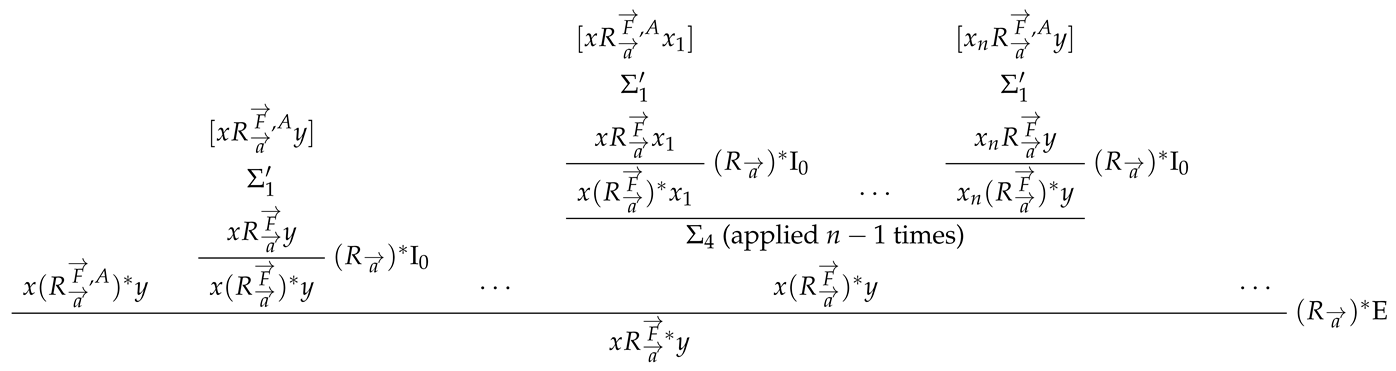

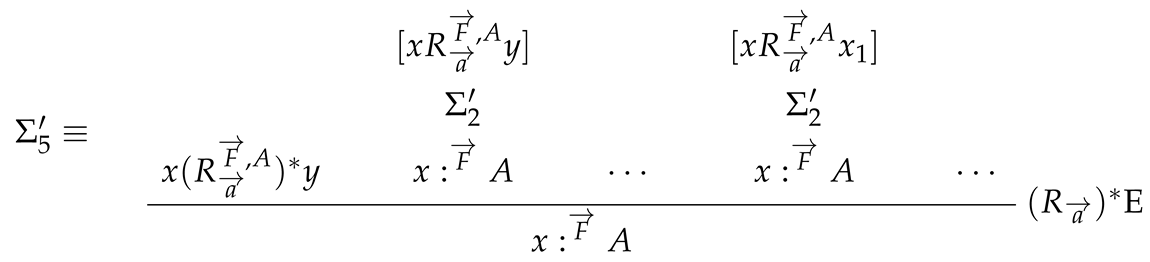

The following are needed for the completeness proof.

Proposition 4.

Proof.

- Let .

- Let .

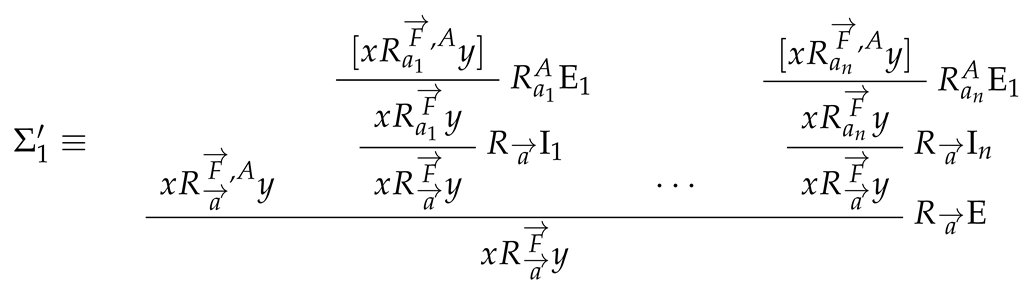

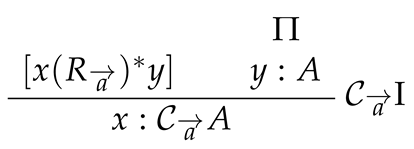

- where is

and similarly for for every but with and as its top most formulas.

and similarly for for every but with and as its top most formulas.

- where is

□

□

Proposition 5.

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

- 6.

Proof.

- □

6. Soundness and Completeness

Theorem 1

(Soundness). Let be a set of formulas. NPAC is sound (i.e., implies ).

Proof.

From the semantic definition, Proposition 2, and Proposition 3, it is easy to see that all NPAC rules are truth-preserving rules. The proof proceeds by induction over the number of applications of rules in the deduction of . □

Theorem 2

(Completeness). Let be a set of formulas. NPAC is complete (i.e., implies ).

Proof.

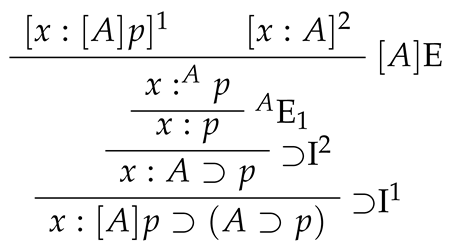

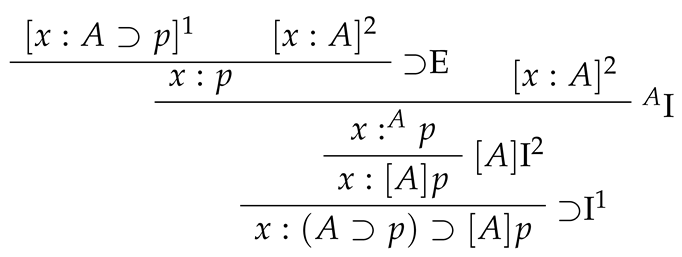

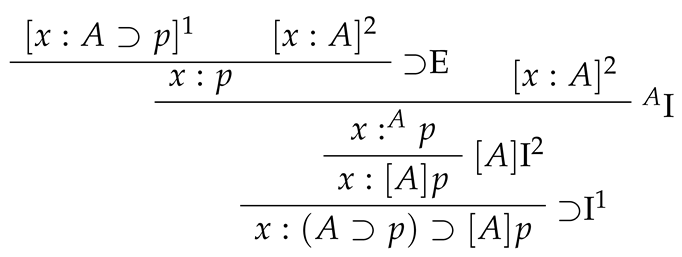

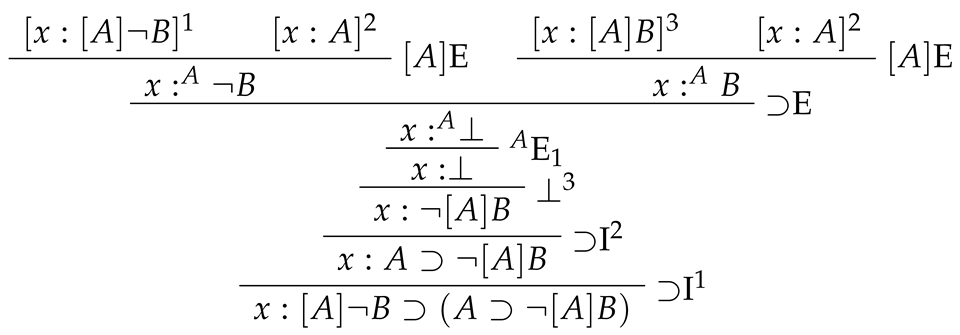

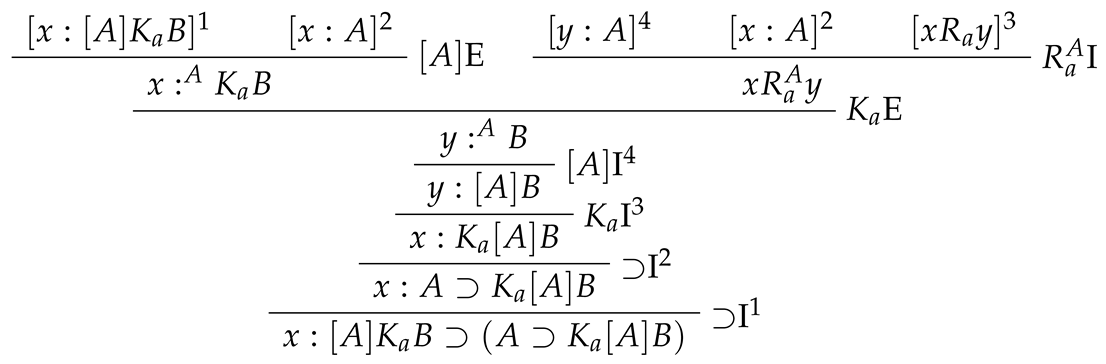

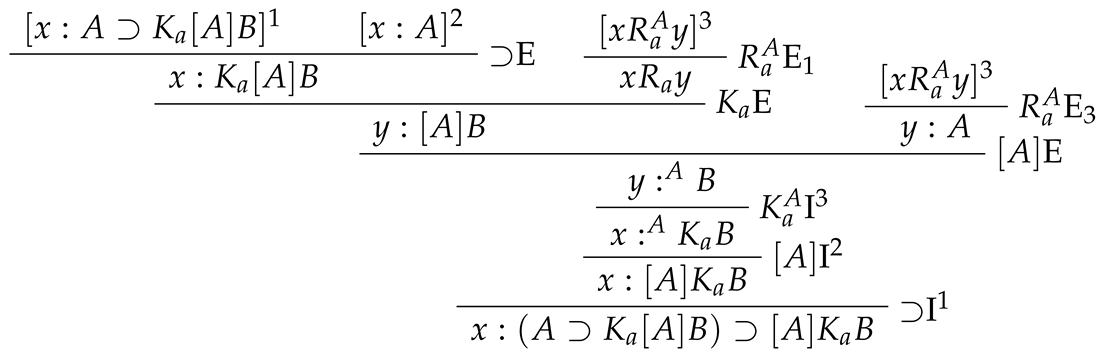

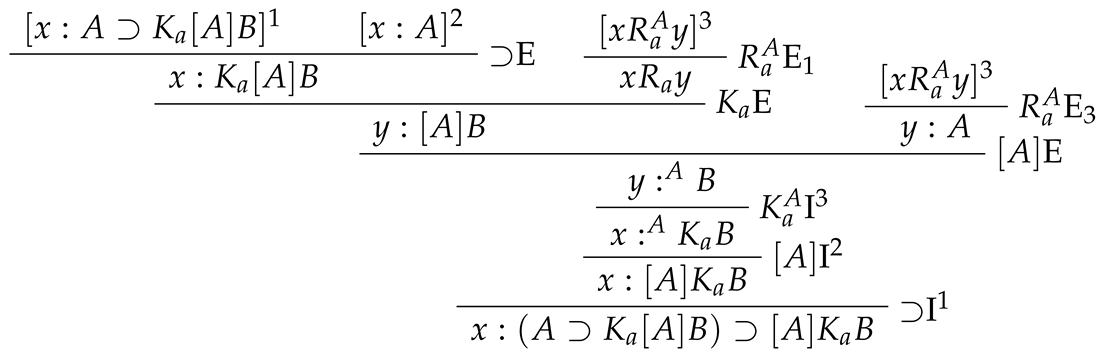

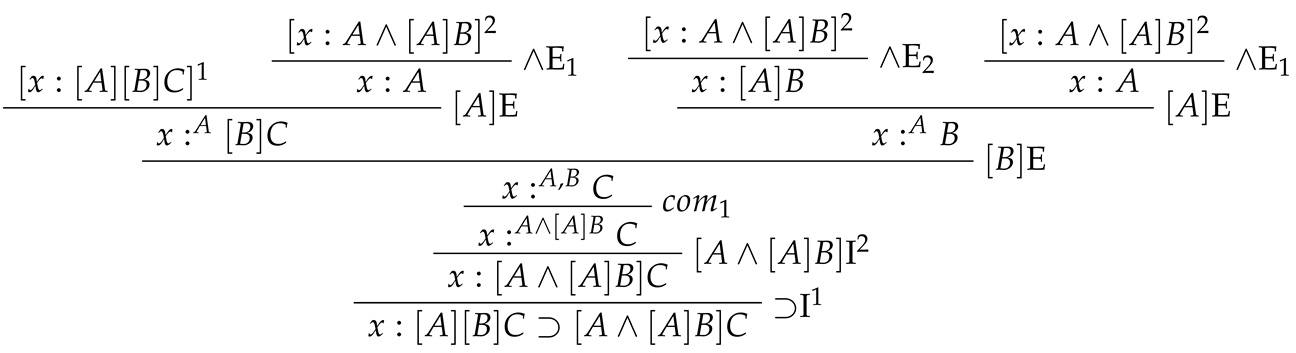

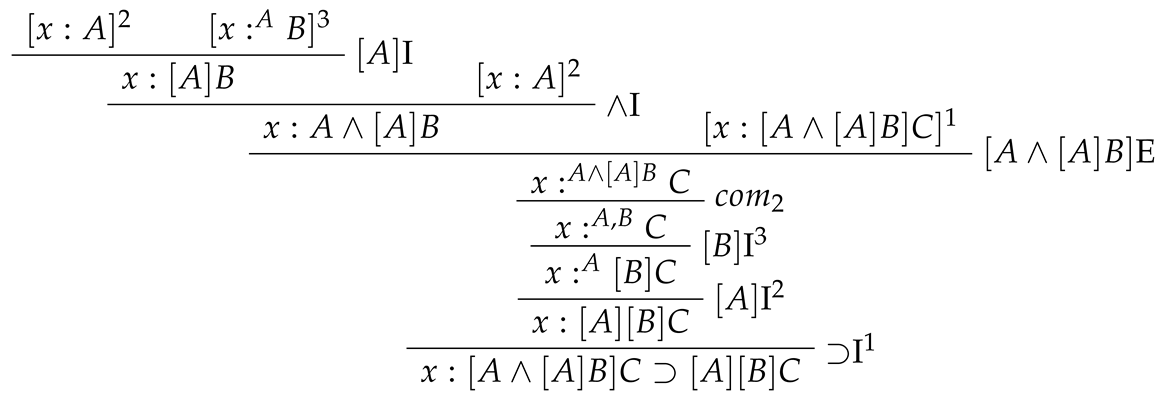

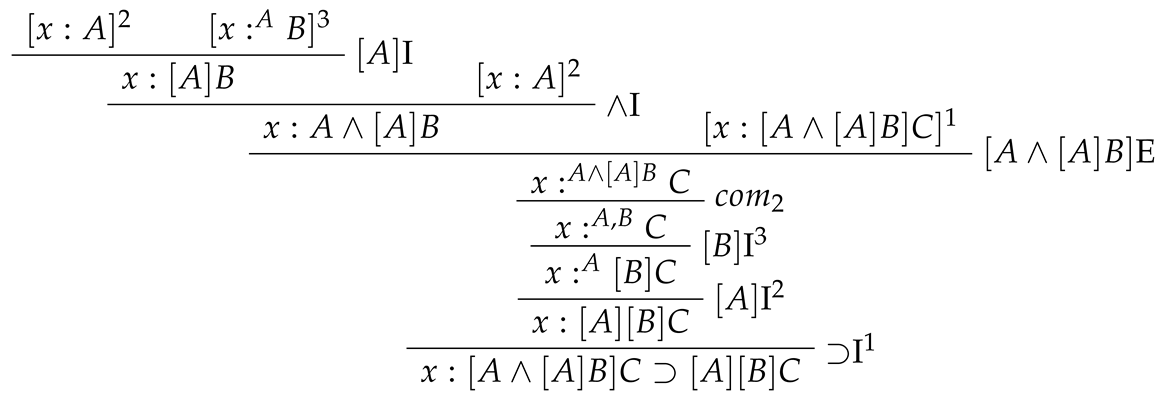

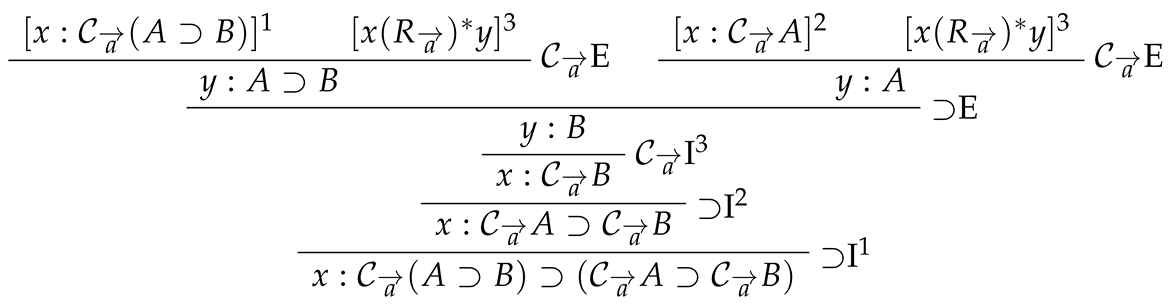

We prove completeness by showing that all axioms and rules of PAC are derivable in NPAC. As PAC is complete, it follows that NPAC is also complete. There are 17 axioms and rules needed to be shown to be derivable from NPAC. Observe that the axioms of PAC of the form “A” are captured by the derivability of in NPAC where x and are arbitrary and that rules of PAC of the form “from infer D’’ are captured by showing that the derivability of in NPAC implies the derivability of in NPAC where are arbitrary.

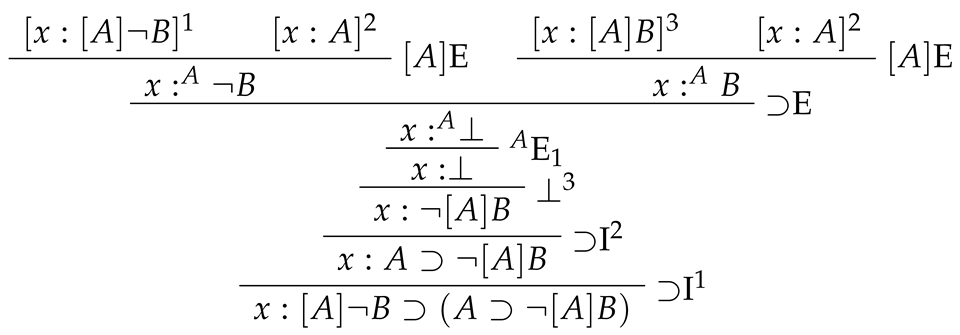

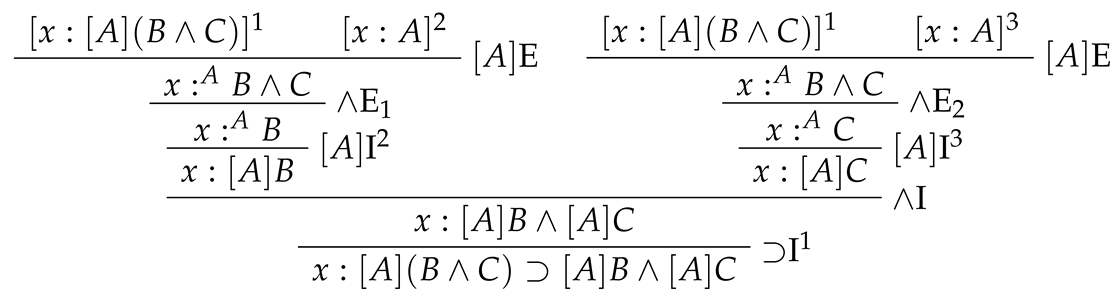

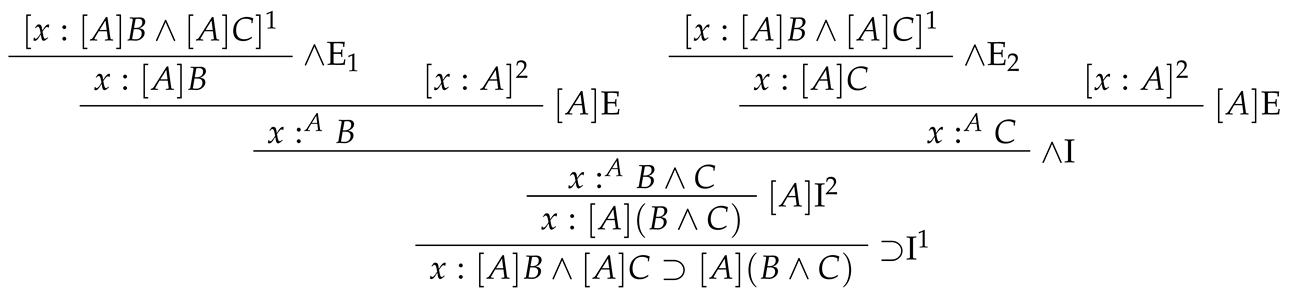

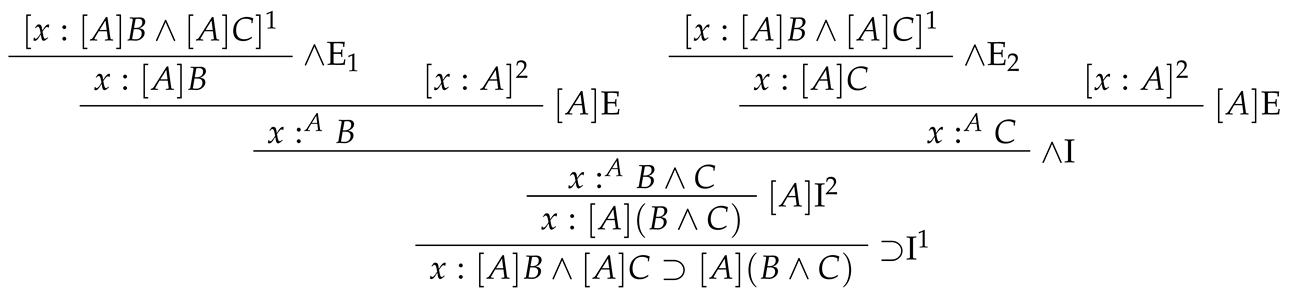

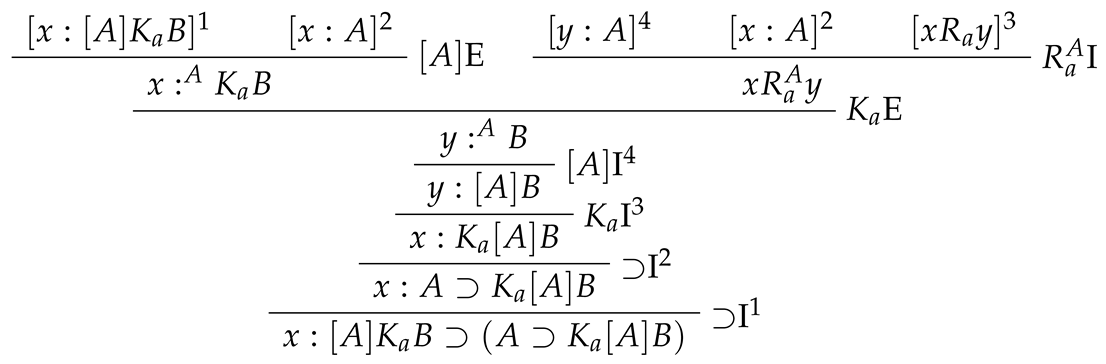

In the following proof, we let the world x and the sequence of formulas to be arbitrary. We remove the in the following proof (except in 16) without loss of generality. One can refer the proof for S5 axioms and rules (i.e., ) in [12]. The following is the rest of the proof.

6. Atomic permanence. For one direction,

For the other direction,

7. Announcement and negation. For one direction,

For the other direction,

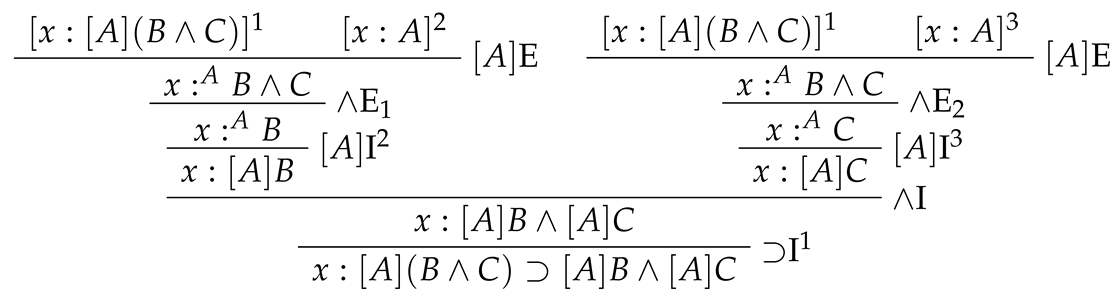

8. Announcement and conjunction. For one direction,

For the other direction,

9. Announcement and knowledge. For one direction,

For the other direction,

10. Announcement composition. For one direction,

For the other direction,

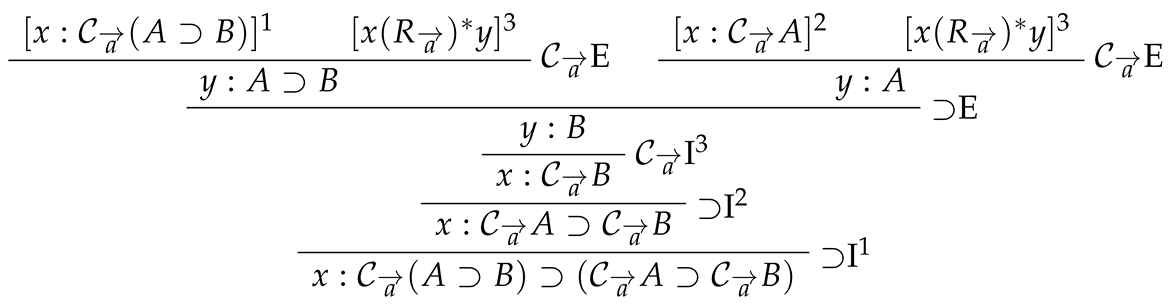

11. Distribution of .

12. Mix of common knowledge.

15. Necessitation of . Suppose that . Then, for every . Let be a derivation of and x be an arbitrary world. Then:

Therefore, for every . Hence, .

16. Necessitation of . Suppose that . Then for every and every sequence of formulas . Then:

Therefore, for every . Hence, .

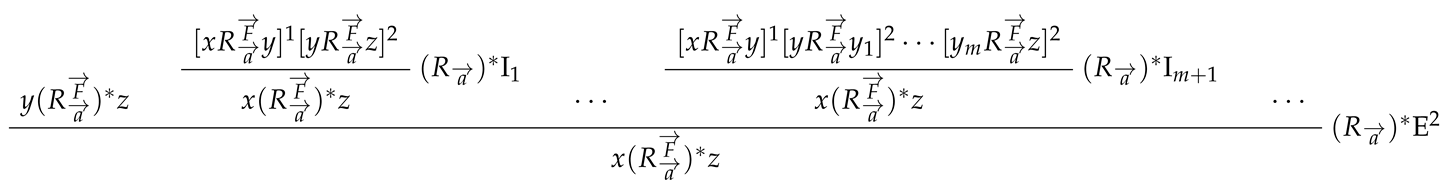

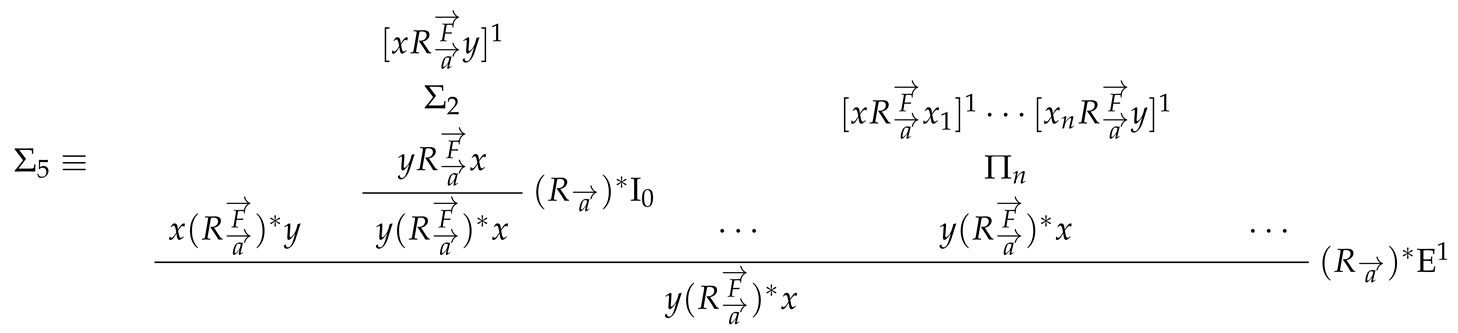

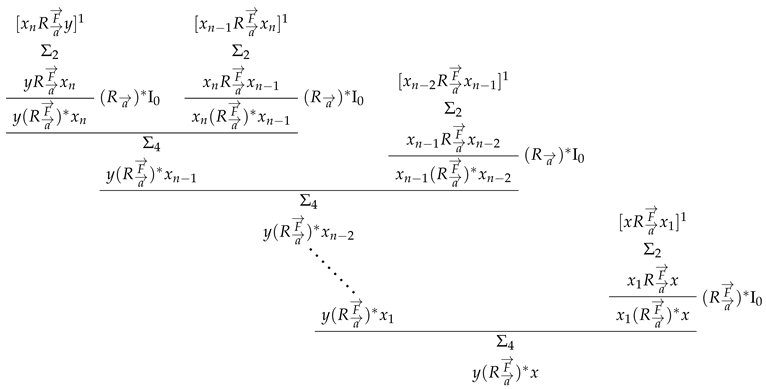

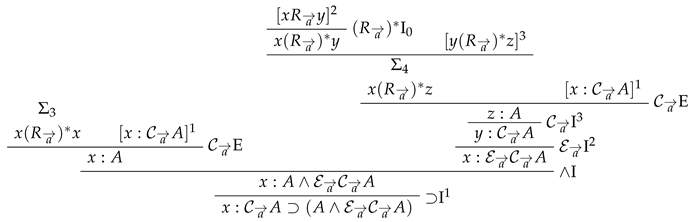

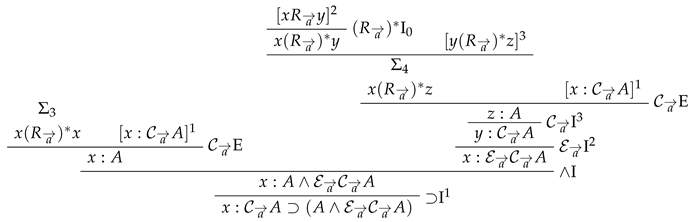

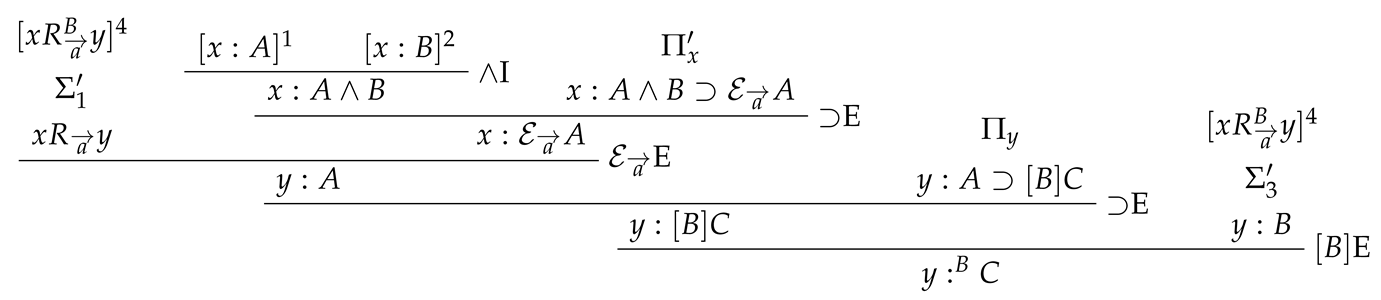

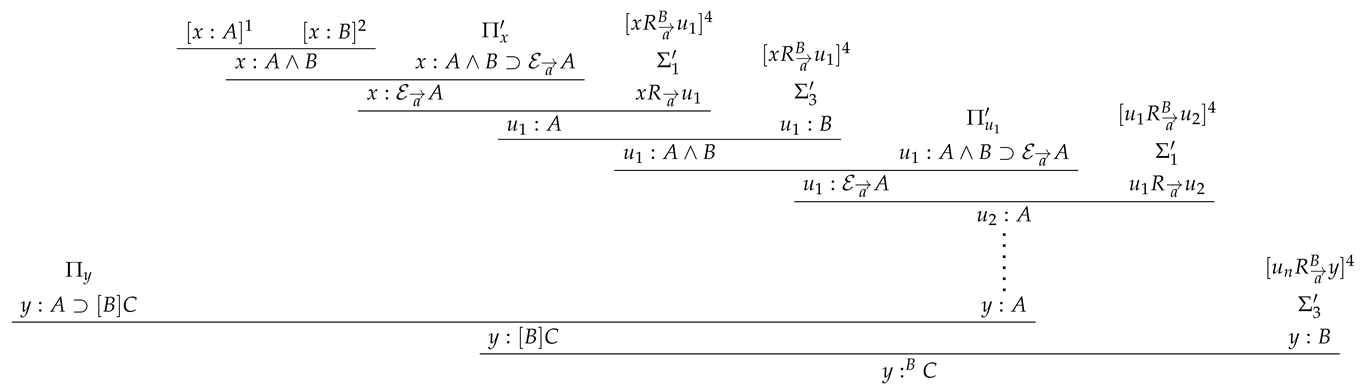

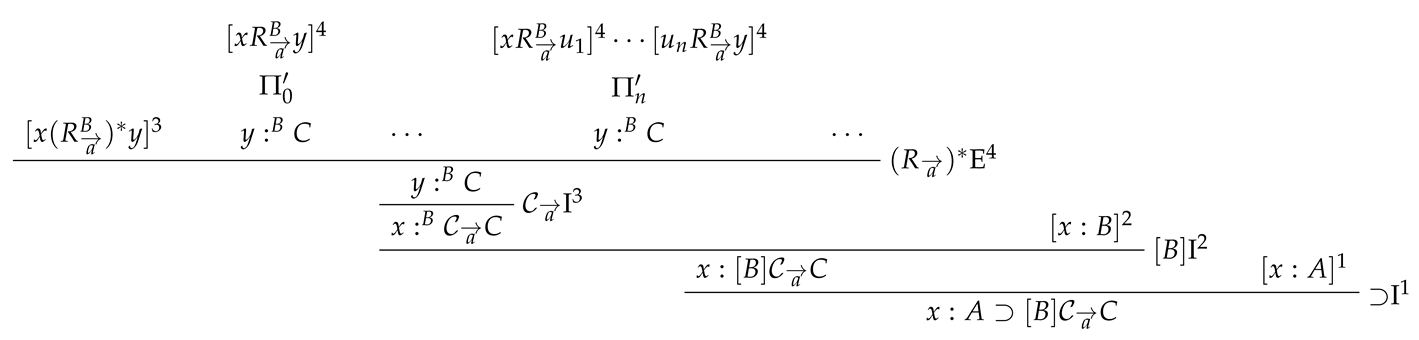

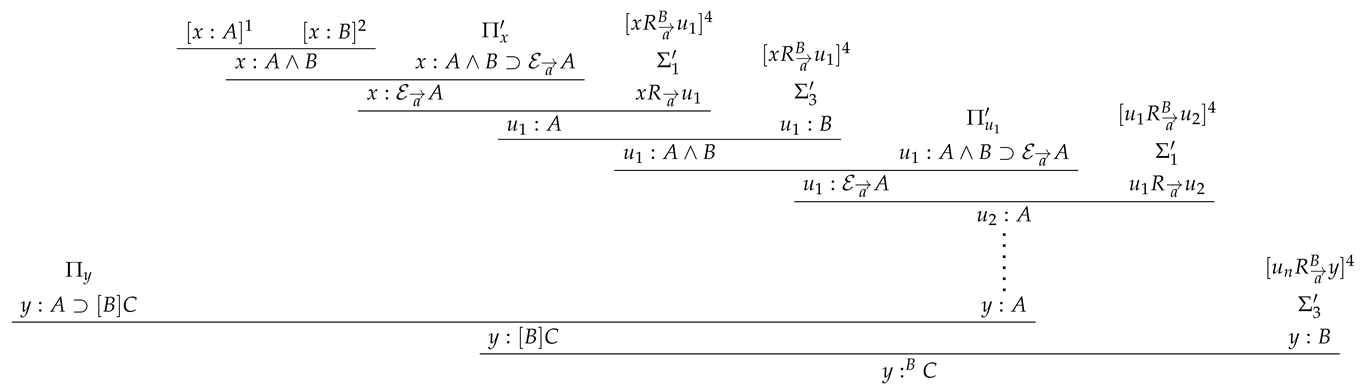

17. Announcement and common knowledge. Similarly as in 15 and 16, suppose that and . Now, for every let be a derivation of and be a derivation of . Then the derivation of is as follow:

where and are respectively

where and are respectively

and

and

Therefore, for every . Hence, . □

Note that although the soundness proof presented here establishes the validity of every derivable labelled or relational formula, the indirect completeness proof establishes only the derivability of every valid basic formula. In other words, we can at least sure that there is a derivation of a basic formula where it is true in every world given every update. Hence, we only establish weak completeness rather than strong completeness where all valid formulas (including relational and labelled) are derivable. There might still be a possibility of not having a derivation of a valid labelled formula where its basic formula is true in a specific world given a specific update, and a valid relational formula in general. One can refer to [13] for more discussion on weak and strong completeness in a labelled proof system.

7. Discussion

As we have stated in the introduction, we assume that the announcement made is always true. Public announcement logic with this assumption was initially proposed by Plaza in [14]. We can, however, make a weaker assumption by saying that an announcement can be either true or false, as done by Gerbrandy and Groenevel in [15]. There are several reasons why we allow an announcement to be false. One of them is that an announcement made in a social setting may not always be true. In a cryptographic perspective, for example, a piece of information announced by an agent is not always trustful. One can refer to [16] for more discussion on the differences between a Gerbrandy–Groenevel (GG) style public announcement logic and Plaza-style public announcement logic.

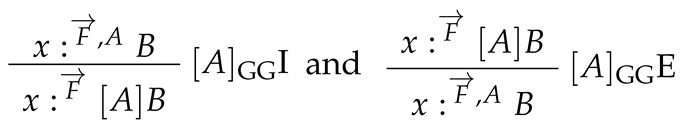

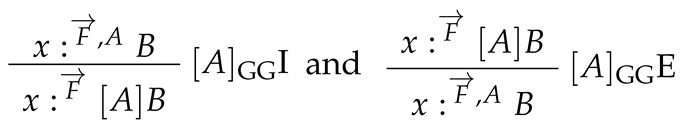

To obtain a labelled natural deduction system for PAC in GG-style, say, GG-NPAC, we therefore change the announcement rules I and E in NPAC as follows:

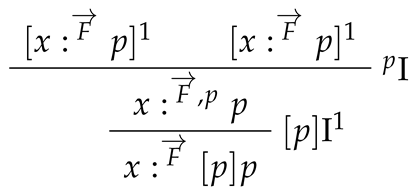

Now, these rules make it harder to establish an announcement formula . As shown in I rule, we do not make an assumption of as we do in I in Plaza-style NPAC. This captures that the formula A being announced is not necessarily true. As an obvious example, is a valid formula in Plaza-style PAC but not valid in GG-style PAC. Proof theoretically, we can capture this example since we can derive for arbitrary x and :

Hence is derivable in Plaza-style NPAC. On the other hand, we cannot derive for some x and in GG-NPAC since we have to derive to introduce by I. However, can only be obtained by atom introduction rule I which requires to be outright provable which is impossible for some atomic proposition p. Hence is not derivable in GG-NPAC. We will leave further investigations on GG-NPAC, especially on the interaction between common knowledge and announcement in GG-style, for future research.

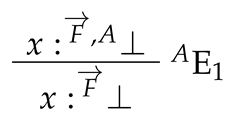

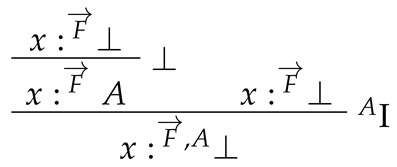

Now we will discuss several problems of NPAC in attaining normalisation and subformula property. At first glance, the rules of NPAC satisfy some principles laid down by proof-theoretic semantics [17,18]. Firstly, the rules are in harmony in the sense that everything that is required to introduce a formula is similar to everything that is obtained by eliminating that very formula. One possible way to see this is to observe that all rules follow almost identically the common pattern of propositional rules (e.g., the rules resemble the disjunction rules but with n many rules for the introduction and n many minor premises in the elimination instead of two). Secondly, by properly defining the rank of a formula, which will involve an ordinal analysis considering that introducing the common knowledge operator may require infinite premises, we can see that every formula is introduced (eliminated) with a rank higher (lower) than the rank of the premise(s).

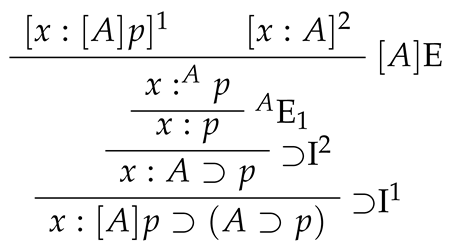

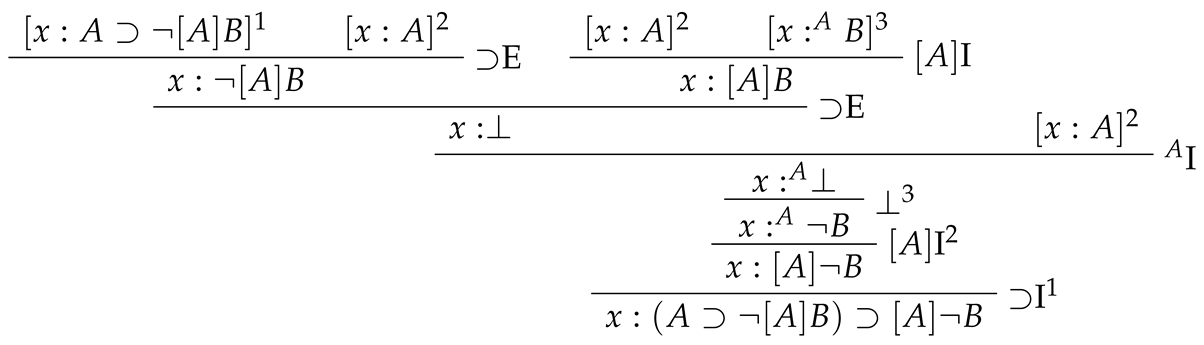

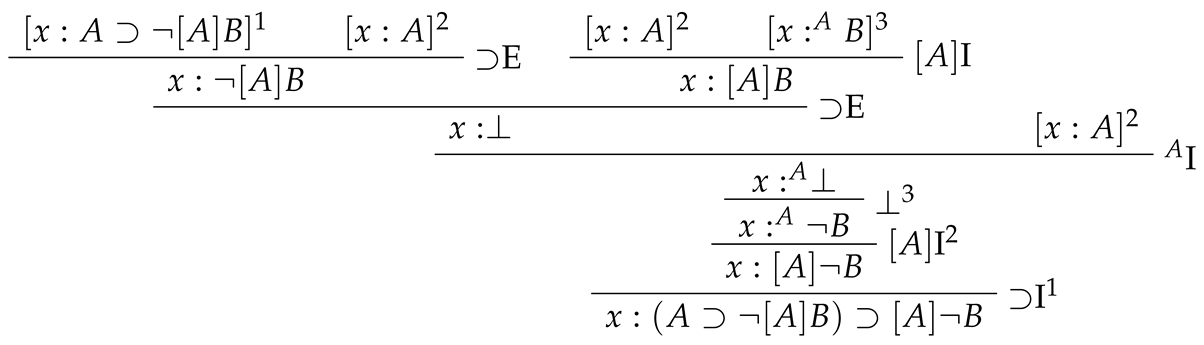

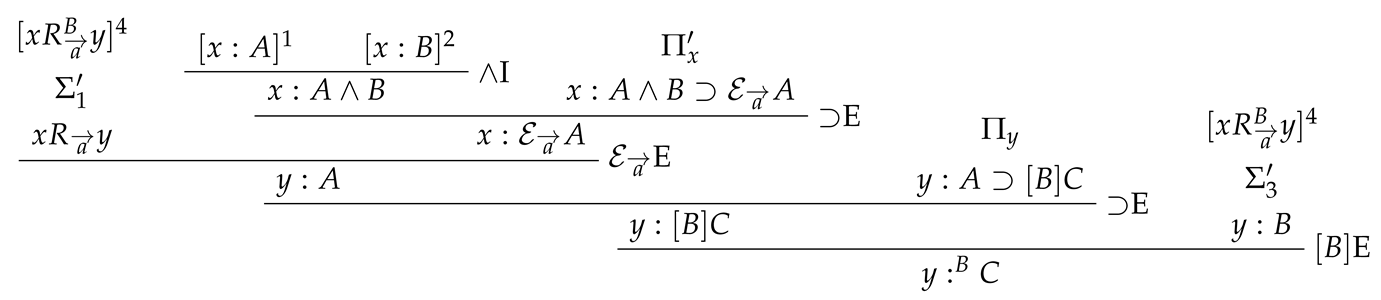

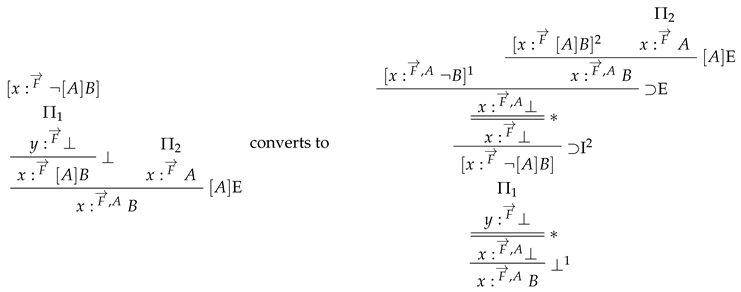

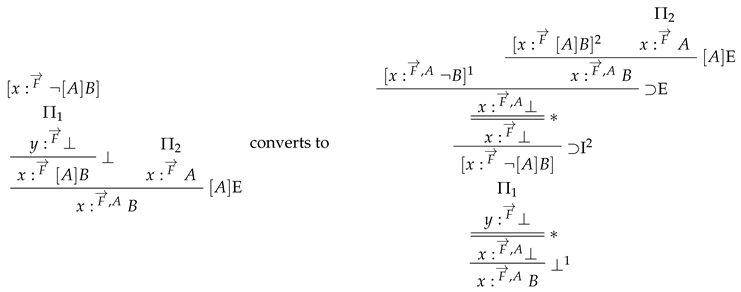

Another principle that is of main importance is normalisation. However, there are two main difficulties of showing the normalisation for NPAC. Firstly, the conclusion of an application of ⊥ rule may be the major premise of an elimination rule and such formula occurrences would violate the subformula property. However one can resolve this by introducing conversions involving the ⊥ rule as done in [19,20]. Nevertheless, to resolve this problem, one has to show the derivability of some formula from some formula as shown below as an example showing how to reduce a maximal formula of the form obtained by the ⊥ rule:

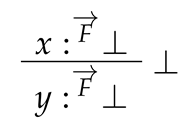

The critical step marked by * can be justified however if we can show that ⊥ is global: if ⊥ is proved to be in one of the worlds (even the updated ones) then ⊥ is proved to be in all worlds (including the updated ones). The condition of ⊥ is global is then sufficient to introduce the conversions to resolve the problem mentioned above. Using a similar method as in [12], the globality of ⊥ can be obtained by using two different world symbols as shown in ⊥ rule in Table 2. The globality of ⊥ in NPAC is shown in the following Proposition 6 in the point number 5.

Proposition 6.

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

- 4.

- 5.

Proof.

- We first remove all formulas in by application(s) of (2), then we add the formulas listed in by application(s) of (3).

- By (1) and (4). □

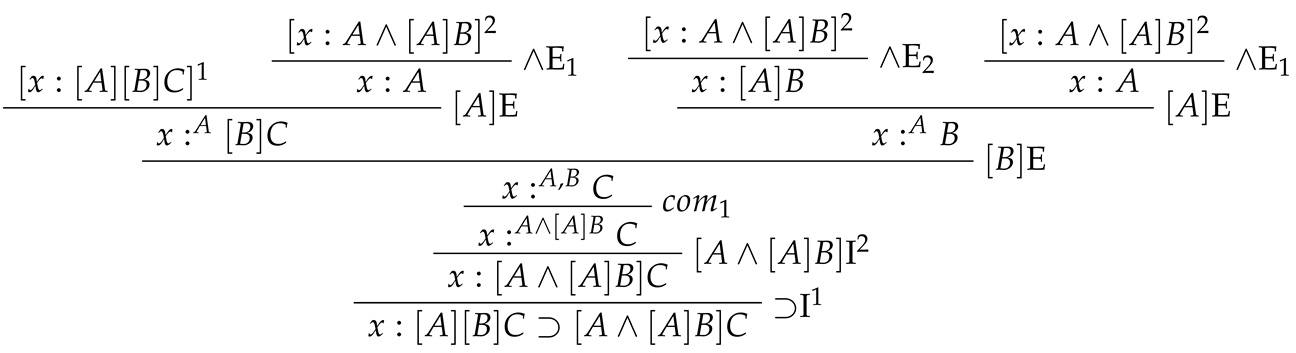

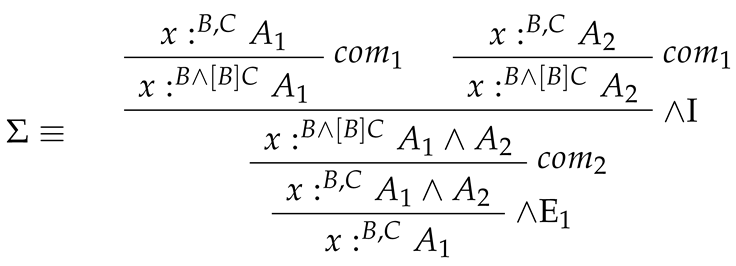

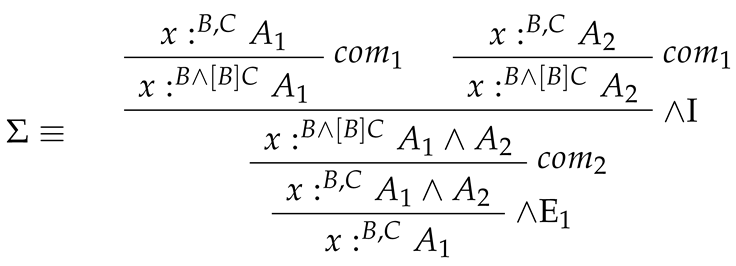

The second difficulty is connected with the composition rules. If one were to view that as an introduction rule and as an elimination rule they would seem to be in harmony (because we could define a conversion in an obvious way). However, the interaction of the composition rules with the rules for logical operators may introduce derivation like the following which obviously does not have the subformula property:

Clearly, the formula does not occur either in the conclusion nor in the premises but it is impossible to reduce by the conventional conversions. Situation of this kind could be resolved by defining permutative conversion for the composition rules. Another possible solution perhaps is to show that the composition rules are indeed admissible in NPAC which we conjecture is to be the case. In fact, more generally, we conjecture the following proposition of which the problem of the composition rules is just a specific case.

Proposition 7.

Without using the composition rules, if and then .

Now, we can show that and without using the composition rules. Then, by using Proposition 7, we can conclude that the composition rules are derivable, and a fortiori admissible in NPAC. We will leave this problem and the possible solutions for now for future research.

Author Contributions

Formal analysis, M.F.M.N.; Funding acquisition, W.A.M.O. and K.B.W.; Supervision, W.A.M.O. and K.B.W.; Writing—original draft, M.F.M.N.; Writing—review & editing, M.F.M.N., W.A.M.O. and K.B.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The first and the third authors were partially funded by University of Malaya grant number GPF025B-2018 and the second author was partially funded by Unversity of Malaya grant number GPF033B-2018.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions. We would also like to thank Peter Schroeder-Heister’s logic group of Tübingen University, Germany where we were given the opportunity to present the findings there on the 10th of February 2020. The feedback and advise, especially from Luca Tranchini, in making this manuscript presentable are greatly appreciated. Finally, we would like to thank the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) for the scholarship that made it possible for us to come to Germany to meet the people in the logic group mentioned.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| PAL | Public announcement logic |

| PAC | Public announcement logic with common knowledge |

| NPAC | Labelled natural deduction for public announcement logic with common knowledge |

| PAC | Hilbert calculus for public announcement logic with common knowledge |

References

- Frittella, S.; Greco, G.; Kurz, A.; Palmigiano, A.; Sikimic, V. A Proof-theoretic semantic analysis of dynamic epistemic logic. J. Log. Comput. 2016, 26, 1961–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffezioli, P.; Negri, S. A Gentzen-style analysis of public announcement Logic. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Logic and Philosophy of Knowledge, Communication and Action; Arrazola, X., Ponte, M., Eds.; University of the Basque Country Press: Donostia, Spain, 2010; pp. 293–313. [Google Scholar]

- Maffezioli, P.; Negri, S. A Proof-theoretical perspective on public announcement logic. Log. Philos. Sci. 2011, 9, 49–59. [Google Scholar]

- Nomura, S.; Sano, K.; Tojo, S. Revising a labelled sequent calculus for public announcement logic. In Structural Analysis of Non-Classical Logics: Studia Logica Library; Yang, S.M., Deng, D.M., Lin, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 131–157. [Google Scholar]

- Balbiani, P.; Van Ditmarsch, H.; Herzig, A.; De Lima, T. Tableaux for public announcement logic. J. Log. Comput. 2010, 20, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Ditmarsch, H.; van der Hoek, W.; Kooi, B. Dynamic Epistemic Logic; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marti, M.; Studer, T. The proof theory of common knowledge. In Jaako Hintikka on Knowledge and Game-Theoretical Semantics; van Ditmarsch, H., Sandu, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 433–455. [Google Scholar]

- Alberucci, L.; Jäger, G. About cut elimination for logics of common knowledge. Ann. Pure Appl. Log. 2005, 133, 73–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, G.; Kretz, M.; Studer, T. Cut-free common knowledge. J. Appl. Log. 2007, 5, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hill, B.; Poggiolesi, F. Common knowledge: Finite calculus with a syntactic cut-elimination procedure. Log. Et Anal. 2015, 58, 136–159. [Google Scholar]

- Prawitz, D. Natural Deduction: A Proof-Theoretical Study; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Viganò, L. Labelled Non-Classical Logics; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Minari, P. Labeled sequent calculi for modal logics and implicit contractions. Arch. Math. Log. 2013, 52, 881–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, J.A. Logics of public communications. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Methodologies for Intelligent Systems; Emrich, M.L., Pfeifer, M.S., Hadzikadic, M., Ras, Z.W., Eds.; Oak Ridge National Laboratory: Oak Ridge, TN, USA, 1989; pp. 201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Gerbrandy, J.; Groeneveld, W. Reasoning about information change. J. Log. Lang. Inf. 1997, 6, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucheli, S.; Kuznets, E.; Renne, B.; Sack, J.; Studer, T. Justified belief change. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Logic and Philosophy of Knowledge, Communication and Action; Arrazola, X., Ponte, M., Eds.; University of the Basque Country Press: Donostia, Spain, 2010; pp. 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Francez, N. Proof-Theoretic Semantics; College Publications: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder-Heister, P. Proof-Theoretic Semantics; Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Stanford, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, A.T.; Martins, L.R. Natural deduction for full S5 modal with weak normalization. Electron. Notes Theor. Comput. Sci. 2006, 143, 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stålmarck, G. Normalization theorems for full first order classical natural deduction. J. Symb. Log. 1991, 56, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).