Abstract

We introduce the concrete category [resp. ] of cubic H-relational spaces and P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mappings between them and study it in a topological universe viewpoint. In addition, we prove that it is Cartesian closed over . Next, we introduce the subcategory [resp. ] of [resp. ] and investigate it in the sense of a topological universe. In particular, we obtain exponential objects in [resp. ] quite different from those in [resp. ].

1. Introduction

In 1984, Nel [1] introduced the concept of a topological universe which implies quasitopos [2]. Its notion has already been put to effective use several areas of mathematics in [3,4,5]. After then, Kim et al. [6] and Lee et al. [7] constructed the category of neutrosophic H-sets and morphisms between them and the category of neutrosophic crisp sets and morphisms between them, and they studied each category in the sense of a topological universe. On the other hand, Cerruti [8] constructed the category of L-fuzzy relations and obtained some of its properties. Hur [9,10] [resp. Hur et al. [11] and Lim et al [12] formed the category of H-fuzzy relational spaces [resp. of H-intuitionistic fuzzy relational spaces and of vague relational spaces] and each category was investigated in topological universe viewpoint.

In 2012, Jun et al. [13] introduced the notion of a cubic set and investigated some of its properties. After that time, Ahn and Ko [14] studied cubic subalgebras and filters of -algebras. Akram et al. [15] applied the concept of cubic sets to -algebras. Jun et al. [16] dealt with cubic structures of ideals of -algebras. Jun and Khan [17] found some properties of cubic ideals in semigroups. Jun et al. [18] studied cubic subgroups. Zeb et al. [19] defined the notion of a cubic topology and investigated some of its properties. Recently, Mahmood et al. [20] dealt with multicriteria decision making based on cubic sets. Rashed et al. [21] applied the concept of cubic sets to graph theory. Yaqoob et al. [22] introduced the notion of a cubic finite switchboard state machine and studied its various properties. Ma et al. [23] define a cubic relation on -LA-semigroup and investigated some of its properties. Kim et al. [24] defined cubic relations and obtained some their properties.

In this paper, we study the category of cubic relations and morphisms between them in the sense of a topological universe proposed by Nel. First, we define the concept of a cubic H-relational space for a Heyting algebra H and introduce the concrete category [resp. ] of cubic H-relational spaces and P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mappings between them, and obtained some categorical structures and give examples. In particular, we prove that the category [resp. ] is Cartesian closed over , where denotes the category consisting of ordinary sets and ordinary mappings between them. Next, we introduce the subcategory [resp. ] of [resp. ] and investigate it in the sense of a topological universe. In particular, we obtain exponential objects in [resp. ] quite different from those in [resp. ].

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we list some basic definitions for category theory which are needed in the next sections. Let us recall that a concrete category is a category of sets which are endowed with an unspecified structure. Refer to [25] for the notions of a topological category and a cotopological category.

Definition 1

([25]). Let be a concrete category.

- (i)

- The -fiber of a set X is the class of all -structures on X.

- (ii)

- is said to be properly fibered over , if it satisfies the following:

- (a)

- (Fiber-smallness) for each set X, the -fiber of X is a set,

- (b)

- (Terminal separator property) for each singleton set X, the -fiber of X has precisely one element,

- (c)

- if ξ and η are -structures on a set X such that and are -morphisms, then .

Definition 2

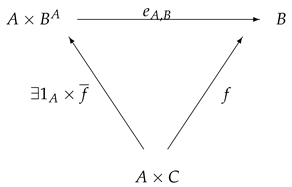

([26]). A category is said to be Cartesian closed, if it satisfies the following conditions:

- (i)

- for each -object A and B, there exists a product in ,

- (ii)

- exponential objects exist in A, i.e., for each -object A, the functor has a right adjoint, i.e., for any -object B, there exist an -object and a -morphism (called the evaluation) such that for any -object C and any -morphism , there exists a unique -morphism such that , i.e., the diagram commutes:

Definition 3

([1]). A category is called a topological universe over if it satisfies the following conditions:

- (i)

- is well-structured, i.e., (a) is concrete category; (b) fiber-smallness condition; (c) has the terminal separator property,

- (ii)

- is cotopological over ,

- (iii)

- final episinks in A are preserved by pullbacks, i.e., for any episink and any -morphism , the family obtained by taking the pullback f and , for each , is again a final episink.

Now refer to [13,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34] for the concepts of fuzzy sets, fuzzy relations, interval-valued fuzzy sets and interval-valued fuzzy relations, neutrosophic crisp sets, neutrosophic sets and operation between them, respectively.

3. Properties of the Categories and

In this section, first, we write the concept of a cubic set introduced by Jun et al. [13] (Also, see [13] for the equality and orders for any cubic sets the complement of a cubic set , and the unions and intersections of two cubic sets ). Next, we introduce the category [resp. ] consisting of all cubic H-relational spaces and all P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mappings between any two cubic H-relational spaces and it has the similar structures as those of [resp. ] (See [35]).

Throughout this section and next section, H denotes a complete Heyting algebra (Refer to [36,37] for its definition) and denotes the set of all closed subintervals of H.

Definition 4

([13]). Let X be a nonempty set. Then a complex mapping is called a cubic set in X, where and be the set of all closed subintervals of I.

A cubic set in which and (resp. and ) for each is denoted by (resp. ).

A cubic set in which and (resp. and ) for each is denoted by (resp. ). In this case, (resp. ) will be called a cubic empty (resp. whole) set in X.

We denote the set of all cubic sets in X by .

Definition 5.

Let X be a nonempty set. Then a complex mapping is called a cubic H-relation in X. The pair is called a cubic H-relational space. In particular, a cubic H-relation from X to X is called a H-relation in or on X. We will denote the set of all cubic H-relations in X as resp. . In fact, each member is a cubic H-set in (See [35]).

Definition 6.

Let and be two cubic H-relational spaces. Then a mapping is called:

- (i)

- a P-order preserving mapping, if it satisfies the following condition:

- (ii)

- a R-order preserving mapping, if it satisfies the following condition:where .

Proposition 1.

Let , and be three cubic H- relational spaces.

- (1)

- The identity mapping is a P-order [resp. R-oder] preserving mapping.

- (2)

- If and are P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mappings, then is a P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mapping.

Proof.

(1) The proof follows from the definitions of P-orders and R-orders, and identity mappings.

(2) Suppose and are P-preserving mappings and let . Then

f is a P-preserving mapping]

g is a P-preserving mapping]

.

Thus, . So is a P-preserving mapping. □

We will denote the collection consisting of all cubic H-relational spaces and all P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mappings between any two cubic H-relational spaces as [resp. ]. Then from Proposition 1, we can easily see that [resp. ] forms a concrete category. In the sequel, a P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mapping between any two cubic H-spaces will be called a -mapping [resp. -mapping].

Lemma 1.

The category [resp. ] is topological over .

Proof.

Let X be a set and let be any family of cubic H-relational spaces indexed by a class J. Suppose be a source of mappings. We define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then clearly, for each and ,

Thus, , for each . So is a -mapping, for each .

For any object , let be any mapping for which is a -mapping, for each and let . Then for each ,

Thus,

[By the definition of ]

So Hence is a -mapping. Therefore is an initial source in .

Now define a mapping as below: for each ,

Then clearly, for each and ,

Thus, , for each . So is a -mapping, for each .

For any object , let be any mapping for which is a -mapping, for each and let . Then for each ,

Thus,

[By the definition of ]

So Hence is a -mapping. Therefore is an initial source in . This completes the proof. □

Example 1.

(1) (Inverse image of a cubicH-relation) Let X be a set, let be a cubic H-relational space and let be a mapping. Then there exists a unique initial cubic H-relation of P-order type [resp. R-order type ] in X for which is a -mapping [resp. is a -mapping]. In fact,

In this case, [resp. ] is called the inverse image under f of the cubic H-relation in Y.

In particular, if and is the inclusion mapping, then the inverse image [resp. ] of under f is called a cubic H-subrelation of . In fact,

(2) (CubicH-product relation) Let be any family of cubic H-relational spaces and let . For each , let be the ordinary projection. Then there exists a unique cubic H-relation of P-order type, in X for which is a -mapping, for each . In this case, is called the cubic H-product relation of and is called the cubic H-product relational space of , and denoted as the following, respectively:

and

In fact, , for each .

Similarly, there exists a unique cubic H-relation of R-order type, in X for which is a -mapping, for each . In this case, is called the cubic H-product relation of and is called the cubic H-product relational space of , and denoted as the following, respectively:

and

In fact, , for each .

In particular, if , then for each ,

and

.

The following is obvious from Lemma 3.9 and Theorem 1.6 in [25] or Proposition in Section 1 in [38].

Corollary 1.

The category [resp. ] is complete and cocomplete over .

Furthermore, we can easily see that [resp. ] is well-powered and cowell-powered. It is well-known that a concrete category is topological if and only if it is cotopological (See Theorem 1.5 in [25]). However, we prove directly that [resp. ] is cotopological.

Lemma 2.

The category [resp. ] is cotopological over .

Proof.

Let X be any set and let be any family of cubic H-relational spaces indexed by a class J. Suppose is a sink of mappings. We define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then we can easily see that

For any cubic H-relational space , let be any mapping such that is a -mapping, for each and let . Then for each and each ,

Thus, by the definition of , So . Hence is a -mapping. Therefore is cotopological over .

Now we define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then we can easily see that

For any cubic H-relational space , let be any mapping such that is a -mapping, for each and let . Then for each and each ,

Thus, by the definition of , So . Hence is a -mapping. Therefore is cotopological over . This completes the proof. □

Example 2.

(CubicH-quotient relation) Let be a cubic H-relational space, let ∼ be an equivalence relation on X and let be the canonical mapping. We define a mapping as below: for each ,

Then we can easily see that is a cubic H-relation in . Furthermore, is a -mapping. Thus, is the final cubic H-relation in .

Now we define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then we can easily see that is a cubic H-relation in . Furthermore, is a -mapping. Thus, is the final cubic H-relation in .

In this case, [resp. ] is called the cubic H-quotient [resp. H-quotient] relation in X induced by ∼.

Definition 7

([38]). Let be a concrete category and let be two -morphisms. Then a pair is called an equalizer in of f and g, if the following conditions hold:

- (i)

- is an -morphism,

- (ii)

- ,

- (iii)

- for any -morphism such that , there exists a unique -morphism such that .

In this case, we say that has equalizers.

Dual notion: Coequalizer.

Proposition 2.

The category [resp. ] has equalizers.

Proof.

Let be two -mappings, where and . Let and define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then clearly, is a cubic H-relation in E and . Consider the inclusion mapping . Then clearly, is a -mapping and .

Let be a -mapping such that . We define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then clearly, .

Let . Since is a -mapping,

Thus, . So is a -mapping.

Now in order to prove the uniqueness of , let such that . Then Thus, is unique. Hence has equalizers.

Similarly, we can prove that has the equalizer . □

For two cubic H-relations in X and in Y, the product of P-order type [resp. R-order type], denoted by [resp. ], is a cubic H-relation in defined by: for any ,

[resp. ].

Lemma 3.

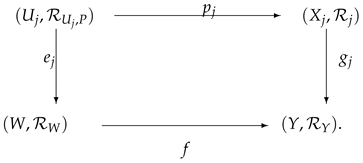

Final episinks in [resp. ] are preserved by pullbacks.

Proof.

Let be any final episink in and let be any -mapping, where , and . For each , let

and let us define a mapping as follows: for each ,

, i.e.,

For each , let and be the usual projections. Then clearly, and are -mappings and , for each . Thus, we have the following pullback square in :

We will prove that is a final episink in . Let . Since is an episink in , there is such that , for some . Thus, and . So is an episink in .

Finally, let us show that is final in . Let be the final structure in W regarding and let . Then

is a -mapping]

is a final episink in ]

.

Thus, . Since is final, is a -mapping. So . Hence . Therefore is final.

Now we define a mapping as follows: for each ,

For each , let and be the usual projections. Then we can similarly prove that final episinks in are preserved by pullbacks. This completes the proof. □

For any singleton set , since the cubic set in is not unique, the category is not properly fibered over . Then from Definitions 1 and 3, Lemmas 2 and 3, we have the following result.

Theorem 1.

The category [resp. ] satisfies all the conditions of a topological universe over except the terminal separator property.

Theorem 2.

The category [resp. ] is Cartesian closed over .

Proof.

From Lemma 1, it is clear that [resp. ] has products. Then it is sufficient to prove that [resp. ] has exponential objects.

For any cubic H-relational spaces and , let be the set of all ordinary mappings from X to Y. We define two mappings and as follows: for each ,

and

Then clearly, is a cubic H-relation in . Moreover, by the definitions of and ,

and

for each .

Let and let us define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Let Then

the definition of ]

and

.

Thus, is a -mapping, where .

For any cubic H-relational space , let be a -mapping. We define a mapping as follows: for each and each ,

Then we can prove that is a unique -mapping such that .

Now we define two mappings and as follows: for each and each ,

and

Then clearly, is a cubic H-relation in . Moreover, by the definitions of and ,

and

for each Let and let us define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Let Then by the definitions of and , we have the followings:

and

Thus, So is a -mapping, where .

For any cubic H-relational space , let be a -mapping. We define a mapping as follows: for each and each ,

Then we can prove that is a unique -mapping such that

This completes the proof. □

Remark 1.

The category [resp. ] is not a topos (See [39] for its definition), since it has no subobject classifier.

Example 3.

Let be two points chain, respectively and let . Let and be the cubic H-relations in X defined by:

Let be the identity mapping. Then clearly, is both monomorphism and epimorphism in [resp. ]. However, is not an isomorphism in [resp. ]. Thus, has no subobject classifier.

4. The Categories and

In this section, we obtain two subcategories and of and , respectively which are topological universes over .

It is interesting that final structures and exponential objects in [resp. ] are shown to be quite different from those in [resp. ].

First of all, we list two well-known results.

Result 1 (Theorem 2.5 [25]). Let be a well-powered and co(well-powered) topological category. Then the followings are equivalent:

- (1)

- is bireflective in ,

- (2)

- is closed under the formation of initial sources, i.e., for any initial source in with for each , then .

Result 2 (Theorem 2.6 [25]). If is a topological category and is a bireflective subcategory of , then is also a topological category. Moreover, every source in which is initial in is initial in .

Definition 8.

Let X be a nonempty set and let be a cubic H-relation in X. Then is said to be reflexive, if R and λ are reflexive, i.e., and , for each .

The class of all cubic H-reflexive relational spaces and -mappings [resp. -mappings between them forms a subcategory of [resp. ] denoted by [resp. ].

The following is the immediate result of Definitions 1 and 8.

Lemma 4.

The category [resp. ] is properly fibered over .

Lemma 5.

The category [resp. ] is closed under the formation of initial sources in The category [resp. ]

Proof.

Let be an initial source in such that each belongs to , where and . Let and let . Since and are reflexive, and . Then

Thus, . So is reflexive.

Now let be an initial source in such that each belongs to . Then clearly, for each ,

Thus, . So is reflexive. This completes the proof. □

From Results 1, 2 and Lemma 5, we have the followings.

Proposition 3.

(1) The category [resp. ] is a bireflective subcategory of [resp. ].

(2) The category [resp. ] is topological over .

It is well-known that a category is topological if and only if it is cotopological. Then by (2) of the above Proposition, the category [resp. ] is cotopological over . However, we will prove that [resp. ] is cotopological over , directly.

Lemma 6.

the category [resp. ] has final structure over .

Proof.

Let X be a nonempty set and let be any family of cubic H-relational spaces indexed by a class J. We define two mappings and , respectively as below: for each ,

and

where . Then clearly, is the cubic H-reflexive relation in X given by: for each ,

Moreover, we can easily check that is a final structure in . Thus, is a final sink in .

Now we define two mappings and , respectively as follows: for each ,

and

Then clearly, is the cubic H-reflexive relation in X given by: for each ,

Moreover, we can easily show that is a final sink in . □

Lemma 7.

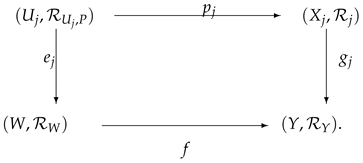

Final episinks in [resp. ] are preserved by pullbacks.

Proof.

Let be any final episink in and let be any -mapping, where is a cubic H-reflexive relational space. For each , let us take , , and as in the first proof of Lemma 3. Then we can easily check that is closed under the formation of pullbacks in . Thus, it is enough to prove that is final.

Suppose is the final cubic H-relation in W regarding and let . Then

is a -mapping]

is a final episink in ]

.

Thus, . On the other hand, by a similar argument in the first proof of Lemma 3, on . So on . Now let . Then clearly, . Thus, on . Hence on W.

Now for each , let us be the mapping as in the second proof of Lemma 3. Then we can similarly prove that final episinks in are preserved by pullbacks. This completes the proof. □

The following is the immediate result of Lemma 4, Proposition 3 (2) and Lemma 7.

Theorem 3.

The category [resp. ] is a topological universe over . In particular, [resp. ] is Cartesian closed over (See [1]) and a concrete quasitopos(See [40]).

In [41], Noh obtained exponential objects in , where denotes the category of fuzzy relations. By applying his construction of an exponential object in to the category [resp. ], we have the following.

Proposition 4.

The category [resp. ] has an exponential object.

Proof.

For any and let . For any , let

We define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then by the definition of , , for each . Thus, , for each . So is a cubic H-reflexive relation in .

Let and we define the mapping as follows: for each ,

Let .

Case 1: Suppose . Then

the definition of , , ]

[Since ]

.

Case 2: Suppose . Then

.

Thus, in either case, . So is a -mapping.

Let be any cubic H-reflexive relational space and let be any -mapping. We define the mapping as follows: for each and each ,

Let and let . Then

[Since is reflexive]

.

Thus, . So is a -mapping. Hence is well-defined. Let .

Case 1: Suppose . Then

[By the definition of ]

.

Case 2: Suppose . Then

.

On one hand, for any ,

.

Thus, . Similarly, we have . So

Hence in either cases, . Therefore is a -mapping. Furthermore, is unique and .

Now for any and let . For any , let

We define a mapping as follows: for each ,

Then we can easily check that is a cubic H-reflexive relation in . Moreover, by the similar argument of the above proof, we can show that is an exponential object in . This completes the proof. □

Remark 2.

(1) We can see that exponential objects in [resp. ] is quite different from those in [resp. ] constructed in Theorem 1.

(2) The category [resp. ] has no subject classifier.

Example 4.

Let be the two points chain and let . Let and be cubic H-reflexive relations in X given by:

and

Let be the identity mapping. Then clearly, is both monomorphism and epimorphism in . However, is not an isomorphism in .

5. Conclusions

We constructed the concrete category [resp. ] of cubic H-relational spaces and P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mappings between them and studied it in the sense of a topological universe. In particular, we proved that it is Cartesian closed over . Next, We introduced the category [resp. ] of cubic H-reflexive relational spaces and P-preserving [resp. R-preserving] mappings between them and investigated it in a viewpoint of a topological universe. In particular, we obtained exponential objects in [resp. ] quite different from those in [resp. ]. Also we proved that [resp. ] is a topological universe but [resp. ] not a topological universe. In the future, we will expect one to study some full subcategories of the category [resp. ].

Author Contributions

Creation and mathematical ideas, J.-G.L. and K.H.; writing–original draft preparation, J.-G.L. and K.H.; writing–review and editing, X.C. and K.H.; funding acquisition, J.-G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by Wonkwang University in 2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Nel, L.D. Topological universes and smooth Gelfand Naimark duality, mathematical applications of category theory. Contemp. Math. 1984, 30, 224–276. [Google Scholar]

- Adamek, J.; Herlich, H. Cartesian closed categories, quasitopoi and topological universes. Comment. Math. Univ. Carlin. 1986, 27, 235–257. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegl, A.; Nel, L.D. A convenient setting for holomorphy. Cah. Topol. Geom. Differ. Categ. 1985, 26, 273–309. [Google Scholar]

- Kriegl, A.; Nel, L.D. Convenient vector spaces of smooth functions. Math. Nachr. 1990, 147, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, L.D. Enriched locally convex structures, differential calculus and Riesz representation. J. Pure Appl. Algebra 1986, 42, 165–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hur, K.; Lim, P.K.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, J. The category of neutrosophic sets. Neutrosophic Sets Syst. 2016, 14, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, K.; Lim, P.K.; Lee, J.G.; Kim, J. The category of neutrosophic crisp sets. Ann. Fuzzy Math. Imform. 2017, 14, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerruti, U. Categories of L-Fuzzy Relations. In Proceedings International Conference on Cybernetics and Applied Systems Research (Acapulco 1980); Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1980; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- Hur, K. H-fuzzy relations (I): A topological universe viewpoint. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1994, 61, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K. H-fuzzy relations (II): A topological universe viewpoint. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1995, 63, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K.; Jang, S.Y.; Kang, H.W. Intuitionistic H-fuzzy relations. Int. J. Math. Math. Sci. 2005, 17, 2723–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, P.K.; Kim, S.H.; Hur, K. The category VRel(H). Int. Math. Forum 2010, 5, 1443–1462. [Google Scholar]

- Jun, Y.B.; Kim, C.S.; Yang, K.O. Cubic sets. Ann. Fuzzy Math. Inform. 2012, 4, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.S.; Ko, J.M. Cubic subalgebras and filters of CI-algebras. Honam Math. J. 2014, 36, 43–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akram, M.; Yaqoob, N.; Gulistan, M. Cubic KU-subalgebras. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2013, 89, 659–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.B.; Lee, K.J.; Kang, M.S. Cubic structures applied to ideals of BCI-algebras. Comput. Math. Appl. 2011, 62, 3334–3342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.B.; Khan, A. Cubic ideals in semigroups. Honam Math. J. 2013, 35, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.B.; Jung, S.T.; Kim, M.S. Cubic subgroups. Ann. Fuzzy Math. Inform. 2011, 2, 9–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zeb, A.; Abdullah, S.; Khan, M.; Majid, A. Cubic topoloiy. Int. J. Comput. Inf. Secur. (IJCSIS) 2016, 14, 659–669. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, T.; Abdullah, S. Saeed-ur-Rashid and M. Bilal, Multicriteria decision making based on cubic set. J. New Theory 2017, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, S.; Yaqoob, N.; Akram, M.; Gulistan, M. Cubic Graphs with Application. Int. J. Anal. Appl. 2018, 16, 733–750. [Google Scholar]

- Yaqoob, N.; Abughazalah, N. Finite Switchboard State Machines Based on Cubic Sets. Complexity 2019, 2019, 2548735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-L.; Zhan, J.; Khan, M.; Gulistan, M.; Yaqoob, N. Generalized cubic relations in Hv-LA-semigroups. J. Discret. Math. Sci. Cryptogr. 2018, 21, 607–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lim, P.K.; Lee, J.G.; Hur, K. Cubic relations. Ann. Fuzzy Math. Inform. 2020, 19, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.Y.; Hong, S.S.; Hong, Y.H.; Park, P.H. Algebras in Cartesian Closed Topological Categories. Lect. Note Ser. 1985, 1, 273–309. [Google Scholar]

- Herrlich, H. Catesian closed topological categories. Math. Coll. Univ. Cape Town 1974, 9, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gorzalczany, M.B. A method of inference in approximate reasoning based on interval-valued fuzzy sets. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1987, 21, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hur, K.; Lee, J.G.; Choi, J.Y. Interval-valued fuzzy relations. JKIIS 2009, 19, 425–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondal, T.K.; Samanta, S.K. Topology of interval-valued fuzzy sets. Indian J. Pure Appl. Math. 1999, 30, 133–189. [Google Scholar]

- Salama, A.A.; Smarandache, F. Neutrosophic Crips Set Theory; The Educational Publisher Columbus: Grandview Heights, OH, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Smarandache, F. Neutrosophy Neutrisophic Property, Sets, and Logic; Amer Res Press: Rehoboth, DE, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy sets. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Similarity relations and fuzzy ordering. Inf. Sci. 1971, 3, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. The concept of a linguistic variable and its application to approximate reasoning-I. Inf. Sci. 1975, 8, 199–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Jun, Y.B.; Lim, P.K.; Lee, J.G.; Hur, K. The category of Cubic H-sets. J. Inequal. Appl. 2020. To Be Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Birkhoff, G. Lattice Theory; A. M. S. Colloquim Publication; American Mathematical Society: Providence, RI, USA, 1967; Volume 25. [Google Scholar]

- Jhonstone, P.T. Stone Spaces; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Herrlich, H.; Strecker, G.E. Category Theory; Allyn and Bacon: Newton, MA, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Ponasse, D. Some remarks on the category Fuz(H) of M. Eytan. Fuzzy Sets Syst. 1983, 9, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubuc, E.J. Concrete quasitopoi. In Applications of Sheaves; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1979; Volume 753, pp. 239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Noh, Y. Categorical Aspects of Fuzzy Relations. Master’s Thesis, Yon Sei University, Seoul, Korea, 1985. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).