Abstract

The construction industry is an important industry because of its effects on different aspects of human life experiences and circumstances. Environmental concerns have been considered in designing and planning processes of construction supply chains in the recent past. One of the most crucial problems in managing supply chains is the process of evaluation and selection of green suppliers. This process can be categorized as a multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) problem. The aim of this study is to propose a novel and efficient methodology for evaluation of green construction suppliers with uncertain information. The framework of the proposed methodology is based on weighted aggregated sum product assessment (WASPAS) and the simple multi-attribute rating technique (SMART), and Fermatean fuzzy sets (FFSs) are used to deal with uncertainty of information. The methodology was applied to a green supplier evaluation and selection in the construction industry. Fifteen suppliers were chosen to be evaluated with respect to seven criteria including “estimated cost”, “delivery efficiency”, “product flexibility”, “reputation and management level”, “eco-design”, and “green image pollution”. Sensitivity and comparative analyses were also conducted to assess the efficiency and validity of the proposed methodology. The analyses showed that the results of the proposed methodology were stable and also congruent with those of some existing methods.

1. Introduction

The construction industry has considerable importance in human civilization. In other words, it is a significant economic sector that provides infrastructure and facilities for cities and built environments. Moreover, the construction industry can indirectly affect other industries and underline the development of social activities and quality of life [1]. Studies on supply chains in the construction industry have appeared from about the mid-1990s [2]. A supply chain includes all participants that try to meet customers’ demands. In general, a supply chain involves all the activities related to the flow of goods, transforming raw materials and components to final products and delivering products to customers. The main objective of a supply chain is to maximize the overall value created [3,4,5,6].

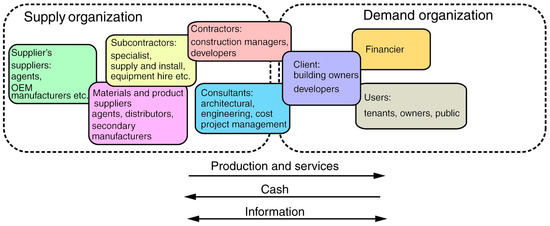

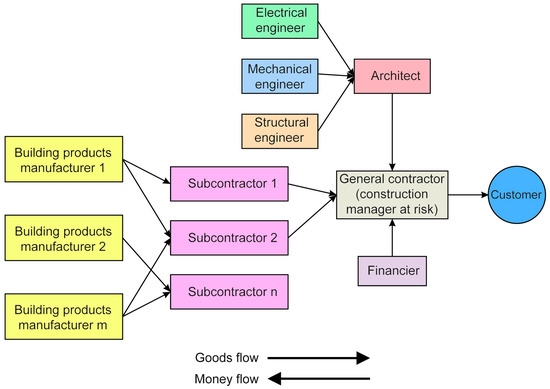

A construction supply chain comprises the entire process of construction businesses from the customer demands, conceptualization, design, and production to maintenance and repair, replacements, and after-sales services. Key elements of a construction supply chain are owners/customers, designers, main contractors, sub-contractors, and suppliers [7]. Because of diversity in dimensions, technologies, supplies, materials, and so on, in the construction industry, there is not a common concept that can be used to provide a certain definition for construction supply chains. However, in Figure 1 and Figure 2, two schematic diagrams are depicted which can show some important elements of a construction supply chain [8,9].

Figure 1.

The framework of construction supply chains presented by London [8].

Figure 2.

The framework of construction supply chains presented by O’Brien et al. [9].

In the past, the aim of supply chain management (SCM) was integration and coordination of different elements of supply chains, improvement in the performance of businesses, and increasing the profitability of them. The importance of environmental aspects was neglected in initial definitions of SCM. The pressure of governmental laws and rules, which force companies to behave in compliance with environmental standards, and also the growing demand of green products led to the appearance of green supply chain management (GSCM) and its related concepts [10,11,12,13]. Researchers have defined GSCM in different ways; not all of them are in agreement that GSCM has positive effects on the environment. Therefore, we can say that GSCM aims to consider environmental aspects in all stages of a supply chain [14,15,16,17].

Activities connected with the construction industry can result in environmental problems such as increasing use of global resources, producing environmental pollution, and climate change. Although increasing the amount of construction is needed in many countries, especially in developing countries, we have to consider the harmful effects of expanding this industry on our environment [18,19,20]. In general, some characteristics of the construction industry restrain the efficiency of construction companies. Temporary organizations and production in a fixed place (construction site) are among these characteristics. For example, in a construction project, only a small part of the production process is fulfilled by the main construction contractor and its staff, tools, and equipment, and the major part (usually more than 75 percent of the value of the project) is performed with the help of suppliers and sub-contractors [21].

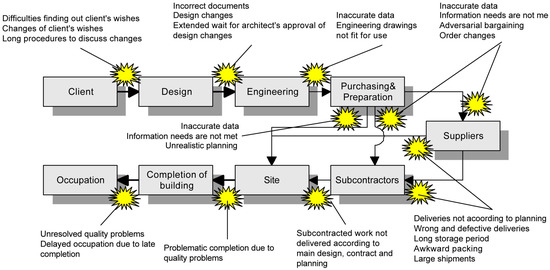

Base on the research of Vrijhoef et al. [22], Figure 3 shows some of the general problems that can occur in the process of construction projects. As we can see, suppliers have a special position in this figure, and they can affect the process more than the other elements. Therefore, the construction industry is highly dependent on contracts with suppliers, and selecting appropriate suppliers for construction companies could be a vital concern [23].

Figure 3.

General problems in the process of construction [22].

If we want to have a green construction supply chain, we should take environmental aspects into consideration for selecting suitable suppliers. Many studies have been made on the evaluation and selection of green suppliers in different types of supply chains [24,25]. Since the evaluation and selection of suppliers usually involves several criteria and alternatives, most of these studies have used multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) methods or developed them to deal with the problem [26,27]. MCDM methods have also been applied to many problems in the construction industry, and some of them are presented in the next section.

The weighted aggregated sum product assessment (WASPAS) method is one of the most efficient MCDM methods, which has been applied to several real-world engineering and managerial problems. This method is an integration of two basic MCDM models: weighted product model (WPM) and weighted sum model (WSM). Integrating WPM with WSM needs a combination parameter which usually is set to 0.5. The integration of these models results in more reliable ranks in solving an MCDM problem. Many studies have been made using this method because of its advantages. The WASPAS method has also been extended in different uncertain and fuzzy environments such as hesitant fuzzy, intuitionistic fuzzy, spherical fuzzy, interval type-2 fuzzy, Pythagorean fuzzy, and single-valued neutrosophic. These developments show that the WASPAS method is capable of being extended and used in many other environments and problems. In other words, we have chosen this method in the current study because the effectiveness of the WASPAS method has been demonstrated in many studies [28,29].

The uncertainty of information is one of the inevitable characteristics in dealing with decision-making problems. This uncertainty usually originates from decision-makers’ opinions and expressions. We can define and capture the uncertainty of information in different ways. In recent years, the fuzzy set theory has become a prevailing tool to handle the uncertainty in decision-making problems. After introducing the theory of fuzzy sets, different types have been developed in various studies such as the intuitionistic fuzzy set (IFS), bipolar-valued fuzzy set (BVFS), fuzzy rough set (FRS), fuzzy soft set (FSS), hesitant fuzzy set (HFS), interval-valued fuzzy set (IVFS), interval type-2 fuzzy set (IT2FS), and Pythagorean fuzzy set (PFS). Recently, the idea of Fermatean fuzzy sets (FFSs) was introduced as a new type of fuzzy set. The notion of FFSs originates from intuitionistic fuzzy set (IFS) and Pythagorean fuzzy set (PFS) concepts. However, FFSs employ new definitions that make them more flexible and more efficient than IFSs and PFSs to handle uncertain information [30,31,32]. The flexibility of FFSs in dealing with uncertain information is the main reason that we use them in developing the approach of the current study.

The aim of this study is to propose a novel and efficient methodology for the evaluation and selection of green suppliers in a construction supply chain under uncertainty. The methodology proposed in this research considers the uncertainty of information expressed by decision-makers in the evaluation procedure. We used Fermatean fuzzy sets to deal with the uncertainty of information. The proposed methodology is based on the WASPAS method as an efficient and useful MCDM method. In addition, the simple multi-attribute rating technique (SMART) was utilized to obtain the weights of criteria according to the ratings given by decision-makers. The WASPAS method has been developed in different fuzzy environments. The main contribution of this study is extending the WASPAS method with Fermatean fuzzy sets and applying the extended methodology to evaluate green construction suppliers. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is no previous research using the WASPAS method with FFSs to deal with multi-criteria decision-making. We can summarize the main contributions of this paper as follows:

- A novel decision-making approach based on WASPAS and Fermatean fuzzy sets is proposed to handle MCDM problems with uncertain information that can be expressed by a group of decision-makers.

- The efficiency of the proposed approach for evaluation of green construction suppliers is demonstrated through an example.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, some recent applications of multi-criteria decision-making methods and techniques in the construction industry are reviewed and summarized. In Section 3, we present preliminaries and basic definitions of Fermatean fuzzy sets. Section 3 introduces a new methodology based on WASPAS, SMART, and FFSs to handle MCDM problems. In Section 4, we present the application of the proposed methodology in the evaluation and selection of green construction suppliers. Sensitivity and comparative analyses are illustrated in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 presents concluding remarks and suggestions for future research.

2. Related Studies on MCDM

In this section, we review some recent studies on the application of MCDM methods in the construction industry. In MCDM, we deal with different decision criteria that can be quantitative or qualitative, and this flexibility in MCDM has led researchers to widely use this approach in various decision-making issues. Assessing and analyzing various features and criteria in various decision-making issues is an exciting aspect of MCDM, and the construction industry can be a convenient case for the application of MCDM.

To prioritize non-critical factors, a new method was proposed based on the technique of order preference similarity to the ideal solution (TOPSIS). The proposed method helped project managers to optimize float times in construction projects as well as better management of concurrent activities in projects [33]. In another study, with the aim of finding the best place to build a hospital according to sustainability criteria, the best–worst method (BWM) was used to determine the decision criteria weights, and the TOPSIS method was used to select and rank the possible construction sites for the hospital. In addition, the construction sites of the hospital were analyzed using mathematical formulations [34]. The TODIM (tomada de decisao interativa multicriterio) method was used to identify the best and most cost-effective under-construction housing project in Calcutta. For this purpose, fourteen under-construction housing projects were evaluated according to ten criteria, and the desired alternatives were identified. The TODIM method was used due to its ability to deal with quantitative and qualitative criteria [35]. A new hybrid fuzzy MCDM approach was proposed to evaluate construction equipment with respect to sustainability criteria. The proposed approach was developed based on SWARA (step-wise weight assessment ratio analysis), CRITIC (criteria importance through intercriteria correlation), and EDAS (evaluation based on distance from average solution) methods in fuzzy environments. Then, by comparing the results of the proposed approach with the results of a number of other MCDM methods, the efficiency and validity of the results were confirmed [36].

In another study, critical success factors of development projects were identified through literature review and evaluated using various criteria. For this purpose, fuzzy TOPSIS and entropy-based fuzzy multi-MOORA (which are among the MCDM methods) were used to rank the critical success factors, and the impact of each factor on construction projects in Iran was illustrated [37]. The application of the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (AHP) for complex construction projects was investigated. Different combinations of fuzzy AHP methods were examined, and these methods were used to evaluate transportation projects. Evaluation of transportation projects is important for prioritizing the resources and evaluating the performance of construction projects [38]. In order to eliminate construction barriers to facilitate the transportation of physically disabled people, a decision support system based on AHP and the preference ranking organization method for enrichment evaluation (PROMETHEE) was introduced to prioritize facilities and select appropriate policies for schools [39]. In a study, a MCDM framework based on AHP method was introduced to investigate the effect of competitive conditions on the evaluation of suppliers in construction supply chains [40]. In order to evaluate the accelerated bridge construction (ABC) method and traditional bridge construction methods, the TOPSIS approach was used in certain and uncertain conditions, and also return-on-investment analysis was performed. The results showed that ABC can provide better results than the traditional methods [41].

Chatterjee et al. [42] proposed a hybrid D-ANP-MABAC model to assess and manage risk in construction projects. In their proposed approach, they used the analytic network process (ANP), multi-attributive border approximation area comparison (MABAC), and consistent fuzzy preference relation (CFPR) developed based on D-numbers. They examined the feasibility and robustness of the proposed approach using a numerical example. In another study, Wang et al. [43] proposed a new approach based on a combination of picture fuzzy normalized projection (PFNP) and vlsekriterijumska optimizacija i kompromisno resenje (VIKOR) methods and used the proposed approach to identify and prioritize risk factors in construction projects. In order to select the most appropriate materials for construction operations according to different criteria, a new MCDM method based on AHP and fuzzy multi-objective optimization on the basis of ratio analysis (MOORA) was developed [44].

In order to select the most appropriate contract from among the highway construction contracts in Greece, an MCDM approach, including multi attribute utility theory, TOPSIS, PROMETHEE, and PROMETHEE group decision-making support system was proposed. The proposed approach was used in two case studies which included seven contracts and nine criteria [45]. In another study, an integrated MCDM approach including ANP and simulation-based sensitivity evaluation methods was proposed to evaluate the planning of facilities. The method turned the spatial layout planning problem into a mathematical planning problem [46]. In a study, sustainability in highway construction projects was evaluated. For this purpose, a new integrated approach for group decision making was proposed based on decision-making trial and evaluation laboratory (DEMATEL), fuzzy cognitive map (FCM), and nonparametric bootstrap simulation methods. The proposed approach was used in a case study to evaluate and prioritize highway construction projects considering economic, environmental, and social aspects [47]. ANP-based decision-making support system was provided to select the most qualified contractor in road construction projects. Five case studies performed in road construction projects were reviewed to validate the results of the proposed approach [48].

Roy et al. [49] proposed an MCDM framework for selecting sustainable material in construction projects. In their proposed approach, the combinative distance assessment (CODAS) method was developed using interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy numbers (IVIF); then, a real case study on brick selection in sustainable building construction projects was evaluated. Yazdani et al. [50] proposed an innovative approach for risk assessment and solving MCDM problems in project selection problems. For this purpose, a fuzzy ANP method was used to examine the interrelationships of different risk factors; failure mode and effect analysis (FMEA) was used to analyze the rankings and develop the decision matrix; and EDAS (evaluation based on the distance from the average solution) was used to determine the rankings of the projects. A case study was performed to assess the proposed approach in the construction industry and confirmed the validity of the proposed approach.

A multi-criteria decision-making support system was proposed to select the compensation method for highway construction contractors in Greece. The proposed approach was developed based on TOPSIS and multi attribute utility theory (MAUT), and the weights of decision criteria were determined by two experts using a revised Simos method (a technique created by J. Simos), AHP, and goal programming [51]. Badalpur and Nurbakhsh [52] identified and assessed the level of risk in a road construction project in Iran using the WASPAS method. They suggested that the WASPAS method was an appropriate method for risk assessment among other MCDM methods. Hashemizadeh and Ju [53] proposed a hybrid approach based on MCDM and geographic information system (GIS) to select a project portfolio for construction contractors. They first scored the decision criteria using the AHP method and then prioritized the projects using TOPSIS. In another study, a multi-criteria decision-making approach was used to select materials in construction projects; 23 criteria and 4 alternatives were identified, decision criteria weights were determined using BWM, and then the alternatives were prioritized using the fuzzy TOPSIS method and the criteria weights [54].

A new GIS-based fuzzy AHP and Dempster–Shafer theory (DST) were used to select the appropriate site for a power plant. The results showed that the DST model had the ability to calculate outputs with different levels of reliability for power plants. However, the Fuzzy AHP method was faster, and a disadvantage of the DST method was its lower speed [55]. Chalekaee et al. [56] proposed a new MCDM approach for the construction delay change response problem. In the proposed approach, four multi-criteria decision-making methods, including SWARA, TOPSIS, additive ratio assessment (ARAS), and geometric mean were used with gray numbers. The proposed approach was implemented in a case study with four alternatives and eight performance criteria, and the results were evaluated. In another study, the AHP method was used to select the best alternative for sustainable construction management. A comprehensive set of decision criteria for construction management was identified and used in a case study in Turkey [57].

The ANP method and fuzzy set theory were used to develop a construction quality index to obtain the desired results in construction inspections. A construction quality index model was developed to determine the quality of concrete according to targeted standards [58]. In a recent study, a decision-making tool was developed based on a hybrid model composed of fuzzy set theory, multi-objective optimization, and MCDM multi-criteria decision making to identify the most sustainable construction alternatives. Six different types of environmental emissions were examined. Fuzzy set theory was used to control the uncertainty, and a multi-objective optimization problem was designed to find optimal solutions. Then, the TOPSIS method was used to select the best solution among the available alternatives [59].

The ANP method was used to identify and prioritize potential risks in the construction sector; 14 interconnections and their frequencies were analyzed based on the data obtained from 106 construction professionals [60]. Zagorskas and Turskis [61] proposed a decision support system based on the Eckenrode rating and the ARAS-F method. The proposed approach was used in a case study to rank and prioritize the factors related to development and renewal of cycling routes. In another study, Fallahpour et al. [62] provided a decision support framework for selecting sustainable construction projects. In their approach, they used an integrated MCDM model to take into account uncertain conditions, and they used fuzzy preference programming (FPP) to modify the fuzzy analytical hierarchy process (FAHP). They also used the fuzzy inference system (FIS) as an expert system based on fuzzy rules.

A new risk assessment model was proposed by Mohandes et al. [63] to assess the safety of construction workers. The proposed model was developed by combining the fuzzy best–worst method (FBWM) and the interval-valued fuzzy technique for order of preference by similarity to ideal solution (IVFTOPSIS), and finally, three experts validated the developed evaluation model. In another study, a decision support model was proposed by Kedir et al. [64] based on fuzzy agent-based modeling (FABM) and MCDM. The proposed approach (by expanding the scope of MCDM through integrating FABM into it) was able to assess the complex relationships and social interactions between crews and crew members and help improve construction decision-making processes.

Dortaj et al. [65] used the modified ELECTRE III method to find suitable locations for construction of subsurface dams (SSDs); 10 regions out of 50 regions were selected as SSD alternatives in Isfahan province in Iran, and 14 criteria were identified for this purpose. The results showed that the Hoseinabad area was a suitable place for constructing a subsurface dam. A decision support system was proposed by Mahdi et al. [66] to select the optimal method for soft clay improvement. In the proposed approach, the value engineering (VE) method was combined with AHP. The validity of the proposed approach was examined using a case study on the highways of northern Egypt. A heterogeneous decision-making framework was developed by Zhang et al. [67] in order to select the most suitable construction equipment among the available alternatives. They used different input data in their proposed approach, and also AHP and EDAS methods were used to determine the weights of decision criteria and rankings of alternatives. Shojaei and Bolvardizadeh [68] used a hybrid MCDM approach to select a green supplier for an academic construction project. Their proposed approach included a combination of rough AHP (for determining the weights of criteria) and rough TOPSIS (for prioritizing the suppliers).

In a recent study, a new hybrid MCDM method was proposed in order to select a suitable contract for outsourcing construction projects. The proposed approach was based on BWM and gray relation analysis (GRA). First, the weights of the decision criteria were determined using BWM; then the alternatives were ranked using the GRA method [69]. A study was conducted by Khoshnava et al. [70] to evaluate the unsafe behaviors of workers and reduce the risk in construction projects. For this purpose, the interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy-improved score function and weighted divergence-based approximation (IVIF-ISF-WDBA) was proposed and implemented. The results showed that the unsafe behaviors of workers can be related to the stakeholder duties in complex and dynamic conditions of the construction industry. Dehdasht et al. [71] proposed a hybrid approach including entropy and TOPSIS methods in order to select key success factors and sustainable drivers in the implementation of the lean construction industry. An experimental study was conducted in the Malaysian construction industry, and a sensitivity analysis of the results was performed to demonstrate the performance of the proposed approach.

Finally, if the readers need more information about the existing literature on multi-criteria decision making in the construction industry, they can refer to articles that have comprehensively reviewed this discussion (e.g., [72,73,74,75,76]). Table 1 shows some important studies on the application of MCDM methods in the construction industry.

Table 1.

Some important studies on MCDM applications in construction Industry.

3. Fermatean Fuzzy Sets

Senapati and Yager [30] proposed Fermatean fuzzy sets as a tool for handling uncertain information more easily. Although this is a new type of fuzzy set, in the previous studies on FFSs, it has been shown that this type of fuzzy set can be very useful in the process of decision-making. We can say that the essence of the Fermatean fuzzy set is derived from the intuitionistic fuzzy sets and Pythagorean fuzzy sets, but FFSs are more flexible to capture uncertain information than IFSs and PFSs. Like IFSs and PFSs, three important components are utilized in definitions of Fermatean fuzzy sets. These three components are the degree of membership (α), the degree of non-membership (β), and the degree of indeterminacy (π). In the following, some features and operators of FFSs used in this study are defined.

Definition 1.

Suppose that X is a universe of discourse. Then a Fermatean fuzzy set can be defined in the following form:

where,, and. In addition, the degree of indeterminacy is. For convenience, we useto represent this FFS [32].

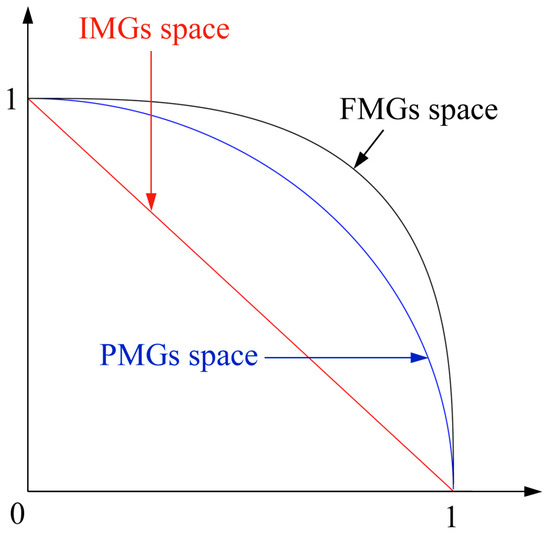

In Figure 4, we can see the difference between the spaces related to intuitionistic membership grades (IMGs), Pythagorean membership grades (PMGs), and Fermatean membership grades (FMGs).

Figure 4.

Spaces related to IMGs, PMGs, and FMGs.

Definition 2.

Let

and be two Fermatean fuzzy sets, and be a positive real number (). Then the following operators can be defined for FFSs [32].

Definition 3.

Suppose that

is an FFS. The score function () and accuracy function () for this FFS are defined as follows [32]:

These functions can be used for comparing two FFSs, namely and . There are different conditions when we compare them [32].

- If , then ;

- If , then ;

- If , then

- If , then ;

- If , then ;

- If , then .

Definition 4.

The complement of an FFS

is defined as follows [32]:

Definition 5.

Let

() be a set of FFSs, and be the corresponding weight vector for (). Then the Fermatean fuzzy weighted average (FFWA) aggregation operator is defined based on the following equation [31]:

Definition 6.

In Definition 3, the score function of an FFS was defined. Suppose that

is an FFS. The value of can be varied in the range of −1 to 1. According to this range, we define here a positive score function for an FFS that always gives a positive defuzzified value.

4. Proposed Methodology

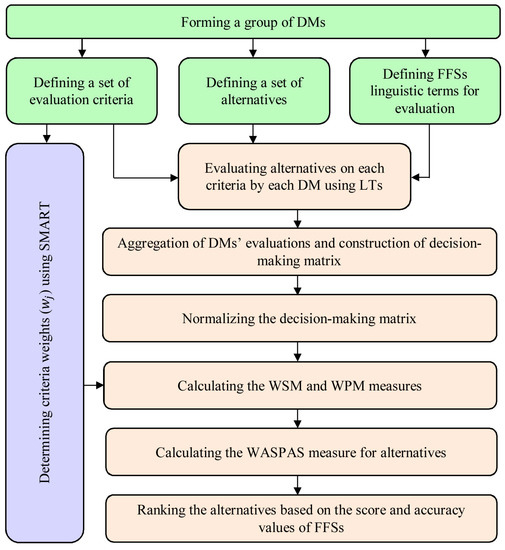

WASPAS is an MCDM method that has widely been used for different decision-making problems. This method is a combination of two popular MCDM methods: weighted sum model (WSM), and weighted product model (WPM) [77]. In this section, we aim to introduce a new and efficient method based on Fermatean fuzzy sets and WASPAS to evaluate green construction suppliers in an uncertain environment. The definitions and operators of Fermatean fuzzy sets presented in the previous section are used to extend the WASPAS method. The framework needed for using the FF-WASPAS method is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The framework of using Fermatean fuzzy WASPAS.

According to Figure 5, there are several parts in the depicted framework. Suppose that , , and denote the number of alternatives, criteria, and decision-makers, respectively. To simplify the procedure of using the proposed approach, we present it in a step-by-step way as follows:

Step 1: Form a group of decision-makers. In this step, some experts are chosen to define the problem. These experts should have enough knowledge about the subject.

Step 2: Define a set of alternatives. The group of decision-makers should assess the problem and list the possible and important alternatives for the evaluation process.

Step 3: Define a set of evaluation criteria. The alternatives need to be evaluated with respect to some criteria. The evaluation criteria should be explored and defined by the group of decision-makers. These criteria should be defined according to data obtained about the alternatives and previous studies made on the related subjects.

Step 4: Determine the weight of each criterion (). In this step, the SMART method is used for the determination of criteria weights [78]. In this method, the decision-makers are asked to assign 10 points to the least important criterion/criteria. They should assign an increasing number of points (up to 100) to the other criteria that are more important. Then the sum of points of each criterion assigned by the decision-makers is calculated. By normalization of the sum of the points, the final criteria weights are determined.

Step 5: Define linguistic terms and the corresponding Fermatean fuzzy sets. Some linguistic terms like “very low” and “very high” and their corresponding FFSs should be defined by decision-makers in this step.

Step 6: Obtain the evaluation of alternatives on each criterion made by each decision-maker. In this step, each DM should evaluate alternatives with respect to each defined criterion. Linguistic terms defined in the previous step based on Fermatean fuzzy sets are used for the evaluation process. Here, the evaluation of the th alternative on the th criterion made by the th decision-maker is symbolized by .

Step 7: Aggregate the evaluations made by decision-makers. In the previous section, we defined an aggregation operator in Equation (9). Using this equation and equal weights (), we should aggregate the evaluations made by each DM in Step 6. Accordingly, the aggregated evaluations or the elements of decision matrix () are presented as follows:

Step 8: Normalize the decision matrix. In the classic WASPAS, a linear normalization method is used to normalize the decision matrix. When we use Fermatean fuzzy sets, we deal with the elements that are in the range of 0 to 1. Therefore, we do not need to use a normalization method for changing the scale of the values. However, if we have non-beneficial (cost) criteria, we need to make some modifications. In this study, we use the concept of the complement of FFSs to transform the values related to non-beneficial criteria. The complement of an FFS was defined in Equation (8). Let BC and NC be the sets of beneficial and non-beneficial criteria, respectively. The elements of the normalized decision-matrix can be determined as follows:

Step 9: Calculate the WSM and WPM measures. Based on the addition, multiplication, and other operators of FFSs defined in the previous section (Equations (2) to (5)), we can calculate the measures concerning WSM and WPM.

Step 10: Calculate the measure of WASPAS. The WASPAS measure is calculated by combining the WSM and WPM measures. We need to define a combination parameter (γ) and set its value in this step. The following formula is used for the computations of this step.

Step 11: Rank the alternatives based on the positive score values of . We use Definition 6, which was presented in the previous section, to compare the values of and rank the alternatives.

5. Application to Green Construction Supplier Evaluation

In this section, we apply the proposed Fermatean fuzzy WASPAS method to solve a construction supplier selection problem. Here, we consider a company which plays the role of subcontractor in a construction supply chain. The company is an electrical subcontractor and wants to make an initial assessment on several suppliers for procurement of more than 30 types of components and materials, e.g., cables, switches, panelboards, transformers, light bulbs, and ducts. Since the company asked us to remain anonymous, we cannot mention its name and provide more details. It is important for the company that the suppliers have environmental concerns and conduct their processes in accordance with green criteria. The greener a supplier is, the more preferable it is for the company. In addition, establishing a long-term and collaborative relationship with green suppliers can be a rational option. The steps of the proposed FF-WASPAS for the assessment of the suppliers of this company are presented as follows:

Step 1: The company formed a group of decision-makers including three experts (D1, D2, and D3) from purchasing, project, and engineering departments of the company. The experts were chosen from thirteen experts of these departments. The first expert was the procurement and strategic sourcing director of the company, the second expert was the project manager of the company, and the third expert was the manufacturing and process engineering manager of the company. The board of directors of the company was responsible for selecting the experts.

Step 2: The experts checked the history of purchasing materials and components to obtain a list of possible suppliers. After screening the list of possible suppliers based on their distance from the main location of the construction projects, they reached a consensus on a set of 15 suppliers (S1 to S15) or alternatives for the evaluation process.

Step 3: For defining the evaluation criteria, the experts referred to the literature of the supplier selection problem in the construction industry. They succeeded in defining a set of seven criteria to evaluate the set of alternatives. The criteria include estimated cost, delivery efficiency, product flexibility, reputation and management level, eco-design, green image, and pollution [79,80,81,82,83,84]. Some of the criteria are economic while some other criteria are environmental (green). It should be noted that carbon emissions is an important criterion that usually is considered for green supplier evaluation processes [85]. However, since this study uses an expert-based methodology, we preferred not to measure this quantitative criterion by subjective linguistic terms. Therefore, we asked the experts to consider carbon emissions of the suppliers as a factor that can affect their green images.

Step 4: In this step, to use the SMART method, the experts assigned a point between 10 and 100 to each criterion. For determination of the normalized weights, the sum of the points of each criterion is divided by the total sum of the points. Table 2 shows the points assigned by each DM and the normalized weights of criteria. As can be seen in this table, estimated cost, delivery efficiency, and pollution are more important than the other criteria.

Table 2.

Determination of the criteria weights using SMART.

Step 5: The decision-makers defined linguistic terms with nine levels from “very very low” to “very very high”. The Fermatean fuzzy sets concerning these terms were defined based on intuitionistic fuzzy sets presented by Boran et al. [86]. The nine levels of linguistic terms and the corresponding FFSs are represented in Table 3.

Table 3.

The linguistic terms and FFSs.

Step 6: Each of the DMs evaluated the alternatives on each criterion in this step. They used the linguistic terms defined in Step 5 for the evaluation process. The evaluations made by each decision-maker are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

The evaluations of the suppliers by each DM.

Step 7: The evaluations of decision-makers are aggregated in this step based on Table 4, Equation (11), and p = 3. According to this aggregation, the FFSs related to the elements of the decision matrix are calculated, as shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

The elements of the decision-matrix.

Step 8: The normalized decision matrix is calculated using Table 5 and Equation (12). The elements of this matrix are presented in Table 6. As can be seen in this table, because we have two non-beneficial criteria in this problem, only two columns (first and last columns) are different from Table 5.

Table 6.

The elements of the normalized decision-matrix.

Steps 9 to 11: Based on Equations (13) and (14) and weights determined in Step 4, we can calculate the WSM and WPM measures. Then the WASPAS measure for each supplier is computed with respect to Equation (15). In this study, we used γ = 0.5 for computation of the WASPAS measure of the alternatives. The rank of the alternatives is obtained using these values and Definition 3. The results of this step including the WSM, WPM, WASPAS measures, scores, and final ranks are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

The measures of FF-WASPAS and final ranks.

In Table 7, we can see that S15 is the best supplier. In addition, S8 and S9 are the second and third ranked suppliers, respectively. Although this is an initial assessment of suppliers, the company needs to use the validated results to ensure that the selected supplier is suitable. For this aim, we need to perform an analysis on the obtained results.

6. Sensitivity and Comparative Analyses

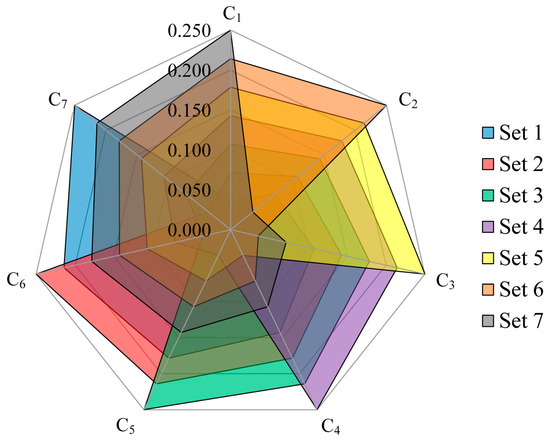

In this section, we aim to analyze the results obtained in the previous section. Firstly, the sensitivity of results is examined by varying the weights of criteria, which are the main parameters of the problem. There were different methods used in the studies of the literature in this field. Here, we use a logical pattern used by Keshavarz Ghorabaee et al. [87]. In this pattern, a number of sets for criteria weights are defined with respect to the number of criteria. In other words, if we have criteria, we should define sets of criteria weights for the sensitivity analysis. In each of the sets, one criterion has the most importance (weight) and another has the least importance, and the other criteria have importance or weights between the most and least important criteria. Using this pattern, we can examine varying the weights of criteria in an efficient and simple way. In the case addressed in the previous section, we used seven criteria to evaluate construction suppliers, so seven sets of criteria weights should be defined for making the sensitivity analysis. The weight of each criterion in each of the sets is presented in Table 8. In addition, the graphical representation of each set can be seen in Figure 6.

Table 8.

The criteria weights for sensitivity analysis [87].

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of the pattern for sensitivity analysis.

The pattern used in this section helps the decision-makers to see that how the results change when the importance of a criterion is increased or decreased. Here, we use the criteria weights presented in Table 8 instead of obtained in Step 4 of the previous section and rank the construction suppliers in each set. The results of the sensitivity analysis based on varying criteria weights are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Results of the sensitivity analysis.

To see the changes of construction suppliers’ ranks, the Spearman’s correlation coefficient (signified by ) is used. This coefficient can measure the strength of relationship between two variables. It will have a value close to 1 if observations have similarities in ranks. Walters [88] presented the interpretation of the values for Spearman’s correlation coefficient, which can be seen in Table 10.

Table 10.

Interpretation of Spearman’s correlation coefficient [88].

In Table 11, the Spearman’s correlation coefficients, which represent the relationship between different sets of the sensitivity analysis, are shown. As it can be seen in this table, all the values related to this coefficient are greater than 0.9, so the relationship between different sets of the sensitivity analysis is very strong. In other words, varying the weights of criteria has not a high impact on the ranks of the construction suppliers. Therefore, we can conclude that the results of the proposed Fermatean fuzzy WASPAS approach are stable when the criteria weights as the main parameters of the problem are varied.

Table 11.

The values of Spearman’s correlation coefficient between different sets.

To validate the obtained results, we aimed to compare them with the results of some existing decision-making methods. Since using Fermatean fuzzy sets in decision-making problems is relatively a new idea and the current study is one of the first studies in this field, we could not compare the proposed approach with other Fermatean fuzzy MCDM approaches here. Instead, to validate the results, we compared the results obtained with the results of TOPSIS, EDAS, COPRAS, and classic WASPAS by using a defuzzified decision-matrix defined based on the Fermatean fuzzy decision-matrix (Table 5). To defuzzify the elements of Table 5, the score function defined in Equation (6) can be used. However, using this function may lead to negative elements in decision-matrix. Some MCDM techniques have problems with negative values of decision-matrix in their procedures. To avoid this issue, Equation (10) of Definition 6 or positive score function was used.

Based on Equation (10), the defuzzified decision-matrix was determined, as shown in Table 12. Then, TOPSIS, EDAS, COPRAS, and classic WASPAS were used to rank the construction suppliers with respect to the types of the criteria and defuzzified decision-matrix. Ranking results of these methods are presented in Table 13, in addition to the results obtained by the Fermatean fuzzy WASPAS.

Table 12.

The defuzzified decision-matrix for the comparative analysis.

Table 13.

The rank of alternatives obtained by different methods.

The last row of Table 13 represents the Spearman’s correlation coefficients between the results of FF-WASPAS and those of the considered MCDM methods of comparison. We can see that the values of this coefficient are greater than 0.8 in all cases. Therefore, our comparative results can demonstrate that the proposed FF-WASPAS approach yields valid results in a construction supplier evaluation problem with multiple criteria.

7. Conclusions

The construction industry can affect different aspects of human society. Thus, managing construction supply chains has been considered as a significant subject in many studies. Environmental concerns made new directions in the field of supply chain management, and this led to the appearance of the concept of green supply chain management. Subsequently, green supplier evaluation and selection has become an important problem in SCM. In this paper, we discussed the vital role of supplier evaluation and selection in supply chains of the construction industry. Because of the nature of this problem, we proposed a new multi-criteria decision-making methodology. The uncertainty of information is a common characteristic of evaluation problems. Therefore, a relatively new type of fuzzy sets, called Fermatean fuzzy sets, was utilized in this study. FFSs are more flexible than IFSs and PFSs in capturing the uncertainty of information. We integrated the efficiency of the WASPAS method as an MCDM method and the flexibility of FFSs to develop a new methodology. For evaluation and selection of green construction suppliers, the SMART technique was also used in the proposed methodology for determination of the weights of criteria according the ratings given by decision-makers. Then, the proposed methodology was applied to a green construction supplier evaluation and selection problem. Two analyses, including a sensitivity analysis and a comparative analysis, were performed to determine if the proposed methodology yields stable and valid results. The sensitivity analysis showed that the changes in results are not significant when criteria weights vary. Moreover, the comparative analysis demonstrated that the proposed methodology yields valid results. Overall, we conclude that the proposed methodology can be considered as an efficient MCDM approach to deal with uncertain information and evaluation problems.

The main advantages of the proposed approach is using WASPAS as an efficient method in an uncertain environment, the flexibility of defining the information expressed by decision-makers using Fermatean fuzzy sets and linguistic terms, and the applicability of the approach to a wide range of MCDM problems. Future research can address other MCDM problems such as construction equipment evaluation, construction contractor evaluation, construction material selection, and so on. We used crisp values in the SMART technique, so another area for future research could be directed towards developing SMART based on FFSs. However, the proposed approach has some disadvantages and limitations. Unlike some other types of fuzzy sets, we cannot examine the effect of changing the level of uncertainty (e.g., α-level) in the evaluation results. Another limitation of the proposed approach is the inability of it to calculate several values such as supplier’s performance, market, hedonic, and customer-perceived values.

Therefore, improvement of this approach by integrating it with other methods like multi-attribute market value assessment (MAMVA) [89,90] can be considered in future research. In this way, we may develop a new technique to define supplier performance that directly relates to the quantitative and qualitative indicators of suppliers. In the new technique, the supplier in question can be compared with the best-performing supplier to determine a supplier’s performance. Using MAMVA, the values that define the supplier’s performance range from 0% to 100%. This makes it possible to make a visual assessment of the supplier’s performance. The supplier’s performance, market, hedonic, and customer-perceived values are directly proportional to a system of adequate indicators and the weights and values of these indicators. Therefore, the results of this research, neuro decision matrices [91,92], and MAMVA methods [89,90] can be used as a basis to determine the market, hedonic, and customer-perceived values of suppliers.

The decision process (the determination of system, values, weights of decision criteria, validation of the developed evaluation approach, etc.) has a high dependence on experts. To improve this decision-making process, neuro decision-making and neuro-questionnaires can be incorporated in future research. This can provide a chance for interested parties to interpret the multifaceted decision process in a more effective and reliable manner.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.-G., E.K.Z., and A.K.; Methodology, M.K.-G., M.A., E.K.Z., and M.H.-T.; Validation, M.K.-G. and A.K.; Formal analysis, M.K.-G. and M.A.; Investigation, M.K.-G., M.A., and M.H.-T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.K.-G. and M.H.-T.; Writing—Review and Editing, E.K.Z. and A.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research was funded by European Regional Development Fund under a grant agreement No 01.2.2-LMT-K-718-01-0073 with the Research Council of Lithuania (LMTLT).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bragança, L.; Vieira, S.M.; Andrade, J.B. Early Stage Design Decisions: The Way to Achieve Sustainable Buildings at Lower Costs. Sci. World J. 2014, 2014, 365364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wibowo, M.A.; Sholeh, M.N. The Analysis of Supply Chain Performance Measurement at Construction Project. Procedia Eng. 2015, 125, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, D.M.; Cooper, M.C.; Pagh, J.D. Supply chain management: Implementation issues and research opportunities. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 1998, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M.; Amiri, M.; Olfat, L.; Khatami Firouzabadi, S.M.A. Designing a multi-product multi-period supply chain network with reverse logistics and multiple objectives under uncertainty. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2017, 23, 520–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowersox, D.J.; Closs, D.J. Logistical Management: The Integrated Supply Chain Process; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Boone, T.; Jayaraman, V.; Ganeshan, R. Sustainable Supply Chains: Models, Methods, and Public Policy Implications; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, X.; Wang, Y.; Shen, Q.; Yu, X. Coordination mechanisms for construction supply chain management in the Internet environment. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2007, 25, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- London, K. Construction Supply Chain Economics; Routledge: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, W.J.; Formoso, C.T.; Ruben, V.; London, K. Construction Supply Chain Management Handbook; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava, S.K. Green supply-chain management: A state-of-the-art literature review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 53–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbounjimi, M.; Abdulnour, G.; Ait-KadiI, D. Green Closed-loop Supply Chain Network Design: A Literature Review. Int. J. Oper. Logist. Manag. 2014, 3, 275–286. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis, J.; Zhu, Q.; Lai, K.-H. An organizational theoretic review of green supply chain management literature. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 130, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahimnia, B.; Sarkis, J.; Davarzani, H. Green supply chain management: A review and bibliometric analysis. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, M.-L.; Islam, M.S.; Karia, N.; Fauzi, F.A.; Afrin, S. A literature review on green supply chain management: Trends and future challenges. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 141, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, U.R.; Espindola, L.S.; da Silva, I.R.; da Silva, I.N.; Rocha, H.M. A systematic literature review on green supply chain management: Research implications and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 187, 537–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervani Aref, A.; Helms Marilyn, M.; Sarkis, J. Performance measurement for green supply chain management. Benchmarking Int. J. 2005, 12, 330–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Gunasekaran, A.; Papadopoulos, T.; Hazen, B. Green supply chain performance measures: A review and bibliometric analysis. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2017, 10, 85–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyas, S.; Ahmed, S.; Parashar, A. BEE (Bureau of energy efficiency) and Green Buildings. Int. J. Res. 2014, 1, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, B.-G.; Ng, W.J. Project management knowledge and skills for green construction: Overcoming challenges. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2013, 31, 272–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavinich, T.E. Contractor’s Guide to Green Building Construction: Management, Project Delivery, Documentation, and Risk Reduction; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Segerstedt, A.; Olofsson, T. Supply chains in the construction industry. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2010, 15, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrijhoef, R.; Koskela, L.; Howell, G. Understanding Construction Supply Chains: An Alternative Interpretation. In Proceedings of the 9th International Group for Lean Construction Conference, Singapore, 6–8 August 2001; pp. 185–199. [Google Scholar]

- Dubois, A.; Gadde, L.-E. Supply strategy and network effects—purchasing behaviour in the construction industry. Eur. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2000, 6, 207–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-J.; Liu, R.; Liu, H.-C.; Shi, H. Green Supplier Evaluation and Selections: A State-of-the-Art Literature Review of Models, Methods, and Applications. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemaa, S.; Alayidi, A.; Migdalas, A.; Baourakis, G.; Drakos, P. Green Supplier Evaluation and Selection: An Updated Literature Review. In Operational Research in Agriculture and Tourism; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 169–196. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M.; Amiri, M.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Antucheviciene, J. Supplier evaluation and selection in fuzzy environments: A review of MADM approaches. Econ. Res. 2017, 30, 1073–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Rajendran, S.; Sarkis, J.; Murugesan, P. Multi criteria decision making approaches for green supplier evaluation and selection: A literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 98, 66–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Nilashi, M.; Zakuan, N.; Loganathan, N.; Soheilirad, S.; Saman, M.Z.M.; Ibrahim, O. A systematic review and meta-Analysis of SWARA and WASPAS methods: Theory and applications with recent fuzzy developments. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 57, 265–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamucar, D.; Deveci, M.; Canıtez, F.; Lukovac, V. Selecting an airport ground access mode using novel fuzzy LBWA-WASPAS-H decision making model. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 93, 103703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, T.; Yager, R.R. Fermatean fuzzy sets. J. Ambient Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2020, 11, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, T.; Yager, R.R. Fermatean fuzzy weighted averaging/geometric operators and its application in multi-criteria decision-making methods. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 85, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, T.; Yager, R.R. Some new operations over Fermatean fuzzy numbers and application of Fermatean fuzzy WPM in multiple criteria decision making. Informatica 2019, 30, 391–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heravi, G.; Seresht, N.G. A Multi Criteria Decision Making Model for Prioritizing the Non-Critical Activities in Construction Projects. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 3753–3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadnazari, Z.; Ghannadpour, S.F. Employment of multi criteria decision making techniques and mathematical formulation for Construction of the sustainable hospital. Int. J. Hosp. Res. 2018, 7, 112–127. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty, S.; Chakraborty, A. Application of TODIM (TOmada de Decisao Interativa Multicriterio) method for under-construction housing project selection in Kolkata. J. Proj. Manag. 2018, 3, 207–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M.; Amiri, M.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Antucheviciene, J. A new hybrid fuzzy MCDM approach for evaluation of construction equipment with sustainability considerations. Arch. Civ. Mech. Eng. 2018, 18, 32–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghsoodi, A.I.; Khalilzadeh, M. Identification and Evaluation of Construction Projects’ Critical Success Factors Employing Fuzzy-TOPSIS Approach. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 1593–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen Long, D.; Le-Hoai, L.; Tran Dai, Q.; Dang Chau, N.; Nguyen Chau, V. Fuzzy AHP with Applications in Evaluating Construction Project Complexity. In Fuzzy Hybrid Computing in Construction Engineering and Management; Aminah Robinson, F., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 277–299. [Google Scholar]

- Rogulj, K.; Jajac, N. Achieving a Construction Barrier–Free Environment: Decision Support to Policy Selection. J. Manag. Eng. 2018, 34, 04018020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, D.; Nemani, V.S.R.K.; Pokharel, S.; Al Sayed, A.Y. Impact of competitive conditions on supplier evaluation: A construction supply chain case study. Prod. Plan. Control 2018, 29, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Ibrahim, M.; Hadi, M.; Orabi, W.; Xiao, Y. Multi-Criteria Evaluation Framework in Selection of Accelerated Bridge Construction (ABC) Method. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Tamošaitienė, J.; Adhikary, K.; Kar, S. A Hybrid MCDM Technique for Risk Management in Construction Projects. Symmetry 2018, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Wang, J.-q.; Li, L. Picture fuzzy normalized projection-based VIKOR method for the risk evaluation of construction project. Appl. Soft Comput. 2018, 64, 216–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilce, A.C.; Ozkaya, K. An integrated intelligent system for construction industry: A case study of raised floor material. Technol. Econ. Dev. Econ. 2018, 24, 1866–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, F.; Aretoulis, G.N. Comparative analysis of multi-criteria decision making methods in choosing contract type for highway construction in Greece. Int. J. Manag. Decis. Mak. 2018, 17, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, H.; Zhang, M.; Yuan, Y. Analytic Network Process-Based Multi-Criteria Decision Approach and Sensitivity Analysis for Temporary Facility Layout Planning in Construction Projects. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghoddousi, P.; Nasirzadeh, F.; Hashemi, H. Evaluating Highway Construction Projects’ Sustainability Using a Multicriteria Group Decision-Making Model Based on Bootstrap Simulation. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2018, 144, 04018092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasnain, M.; Thaheem, M.J.; Ullah, F. Best Value Contractor Selection in Road Construction Projects: ANP-Based Decision Support System. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 16, 695–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J.; Das, S.; Kar, S.; Pamučar, D. An Extension of the CODAS Approach Using Interval-Valued Intuitionistic Fuzzy Set for Sustainable Material Selection in Construction Projects with Incomplete Weight Information. Symmetry 2019, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Abdi, M.R.; Kumar, N.; Keshavarz-Ghorabaee, M.; Chan, F.T. Improved decision model for evaluating risks in construction projects. J. Constr. Eng. Manag. 2019, 145, 04019024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, F.; Aretoulis, G. A multi-criteria decision-making support system for choice of method of compensation for highway construction contractors in Greece. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 19, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badalpur, M.; Nurbakhsh, E. An application of WASPAS method in risk qualitative analysis: A case study of a road construction project in Iran. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemizadeh, A.; Ju, Y. Project portfolio selection for construction contractors by MCDM–GIS approach. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 16, 8283–8296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiyazhagan, K.; Gnanavelbabu, A.; Lokesh Prabhuraj, B. A sustainable assessment model for material selection in construction industries perspective using hybrid MCDM approaches. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 16, 234–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokarram, M.; Sathyamoorthy, D. Determination of suitable locations for the construction of gas power plant using multicriteria decision and Dempster–Shafer model in GIS. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2019, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalekaee, A.; Turskis, Z.; Khanzadi, M.; Ghodrati Amiri, G.; Keršulienė, V. A New Hybrid MCDM Model with Grey Numbers for the Construction Delay Change Response Problem. Sustainability 2019, 11, 776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, S.A.; Šaparauskas, J.; Turskis, Z. A Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Model to Choose the Best Option for Sustainable Construction Management. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.-L. Application of the ANP and fuzzy set to develop a construction quality index: A case study of Taiwan construction inspection. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 38, 3011–3026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzouk, M.; Abdelakder, E. A hybrid fuzzy-optimization method for modeling construction emissions. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2020, 9, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunduz, M.; Khader, B.K. Construction Project Safety Performance Management Using Analytic Network Process (ANP) as a Multicriteria Decision-Making (MCDM) Tool. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2020, 2020, 2610306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagorskas, J.; Turskis, Z. Setting priority list for construction works of bicycle path segments based on Eckenrode rating and ARAS-F decision support method integrated in GIS. Transport 2020, 35, 179–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallahpour, A.; Wong, K.Y.; Rajoo, S.; Olugu, E.U.; Nilashi, M.; Turskis, Z. A fuzzy decision support system for sustainable construction project selection: An integrated FPP-FIS model. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2020, 26, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohandes, S.R.; Sadeghi, H.; Mahdiyar, A.; Durdyev, S.; Banaitis, A.; Yahya, K.; Ismail, S. Assessing construction labours’ safety level: A fuzzy MCDM approach. J. Civ. Eng. Manag. 2020, 26, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedir, N.S.; Raoufi, M.; Fayek, A.R. Fuzzy Agent-Based Multicriteria Decision-Making Model for Analyzing Construction Crew Performance. J. Manag. Eng. 2020, 36, 04020053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dortaj, A.; Maghsoudy, S.; Doulati Ardejani, F.; Eskandari, Z. Locating suitable sites for construction of subsurface dams in semiarid region of Iran: Using modified ELECTRE III. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2020, 6, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, I.M.; Ebid, A.M.; Khallaf, R. Decision support system for optimum soft clay improvement technique for highway construction projects. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2020, 11, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Ju, Y.; Santibanez Gonzalez, E.D.R.; Wang, A. SNA-based multi-criteria evaluation of multiple construction equipment: A case study of loaders selection. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2020, 44, 101056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shojaei, P.; Bolvardizadeh, A. Rough MCDM model for green supplier selection in Iran: A case of university construction project. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2020, 10, 437–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, A.; Abbasi, M.; Deng, X.; Ikram, M.; Yeganeh, S. A novel model for risk management of outsourced construction projects using decision-making methods: A case study. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 2020, 10, 97–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnava, S.M.; Rostami, R.; Zin, R.M.; Mishra, A.R.; Rani, P.; Mardani, A.; Alrasheedi, M. Assessing the impact of construction industry stakeholders on workers’ unsafe behaviours using extended decision making approach. Autom. Constr. 2020, 118, 103162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehdasht, G.; Ferwati, M.S.; Zin, R.M.; Abidin, N.Z. A hybrid approach using entropy and TOPSIS to select key drivers for a successful and sustainable lean construction implementation. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0228746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minhas, M.R.; Potdar, V. Decision Support Systems in Construction: A Bibliometric Analysis. Buildings 2020, 10, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darko, A.; Chan, A.P.C.; Ameyaw, E.E.; Owusu, E.K.; Pärn, E.; Edwards, D.J. Review of application of analytic hierarchy process (AHP) in construction. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2019, 19, 436–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utama, W.P.; Chan, A.P.C.; Gao, R.; Zahoor, H. Making international expansion decision for construction enterprises with multiple criteria: A literature review approach. Int. J. Constr. Manag. 2018, 18, 221–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Antucheviciene, J.; Vilutiene, T.; Adeli, H. Sustainable Decision-Making in Civil Engineering, Construction and Building Technology. Sustainability 2018, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Pan, W. Fuzzy Set Theory and Extensions for Multi-criteria Decision-making in Construction Management. In Fuzzy Hybrid Computing in Construction Engineering and Management; Aminah Robinson, F., Ed.; Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 179–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z.; Antucheviciene, J.; Zakarevicius, A. Optimization of weighted aggregated sum product assessment. Elektron. Elektrotechnika 2012, 122, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zardari, N.H.; Ahmed, K.; Shirazi, S.M.; Yusop, Z.B. Weighting Methods and their Effects on Multi-Criteria Decision Making Model Outcomes in Water Resources Management; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Karsak, E.E.; Dursun, M. An integrated fuzzy MCDM approach for supplier evaluation and selection. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 82, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghodsypour, S.H.; O’Brien, C. A decision support system for supplier selection using an integrated analytic hierarchy process and linear programming. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 1998, 56–57, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindan, K.; Khodaverdi, R.; Jafarian, A. A fuzzy multi criteria approach for measuring sustainability performance of a supplier based on triple bottom line approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 47, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottani, E.; Rizzi, A. An adapted multi-criteria approach to suppliers and products selection—An application oriented to lead-time reduction. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 763–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Wei, G.; Gao, H. Models for multiple attribute decision making with interval-valued pythagorean fuzzy Muirhead mean operators and their application to green suppliers selection. Informatica 2019, 30, 153–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Z.-P.; Zhang, H.-Y.; Wang, J.-Q.; Wang, T.-L. Green supplier selection using improved TOPSIS and best-worst method under intuitionistic fuzzy environment. Informatica 2018, 29, 773–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Tayyab, M.; Kim, N.; Habib, M.S. Optimal production delivery policies for supplier and manufacturer in a constrained closed-loop supply chain for returnable transport packaging through metaheuristic approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 135, 987–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boran, F.E.; Genç, S.; Kurt, M.; Akay, D. A multi-criteria intuitionistic fuzzy group decision making for supplier selection with TOPSIS method. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11363–11368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M.; Amiri, M.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z.; Antucheviciene, J. Stochastic EDAS method for multi-criteria decision-making with normally distributed data. J. Intell. Fuzzy Syst. 2017, 33, 1627–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, S.J. Quality of Life Outcomes in Clinical Trials and Health-Care Evaluation: A Practical Guide to Analysis and Interpretation; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Bausys, R.; Kaklauskas, A.; Ubarte, I.; Kuzminske, A.; Gudiene, N. Sustainable market valuation of buildings by the single-valued neutrosophic MAMVA method. Appl. Soft Comput. 2017, 57, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Bausys, R.; Kaklauskas, A.; Raslanas, S. Hedonic shopping rent valuation by one-to-one neuromarketing and neutrosophic PROMETHEE method. Appl. Soft Comput. 2019, 85, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Bardauskiene, D.; Cerkauskas, J.; Ubarte, I.; Seniut, M.; Dzemyda, G.; Kaklauskaitė, M.; Vinogradova, I.; Velykorusova, A. An Affect-Based Built Environment Video Analytics. Autom. Constr. 2019, 106, 102888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaklauskas, A.; Jokubauskas, D.; Cerkauskas, J.; Dzemyda, G.; Ubarte, I.; Skirmantas, D.; Podviezko, A.; Simkute, I. Affective analytics of demonstration sites. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2019, 81, 346–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).