Abstract

The graph centroids defined through a topological property of a graph called g-convexity found its application in various fields. They have classified under the “facility location” problem. However, the g-centroid location for an arbitrary graph is -hard. Thus, it is necessary to devise an approximation algorithm for general graphs and polynomial-time algorithms for some special classes of graphs. In this paper, we study the relationship between the g-centroids of composite graphs and their factors under various well-known graph operations such as graph Joins, Cartesian products, Prism, and the Corona. For the join of two graphs and , the weight sequence of the composite graph does not depend on the weight sequences of its factors; rather it depends on the incident pattern of the maximum cliques of and . We also characterize the structure of the g-centroid under various cases. For the Cartesian product of and and the prism of a graph, we establish the relationship between the g-centroid of a composite graph and its factors. Our results will facilitate the academic community to focus on the factor graphs while designing an approximate algorithm for a composite graph.

MSC:

05C05; 05C25; 05C75

1. Introduction

Graph theory is a branch of mathematics that has applications in every other field including Arts, Humanities, Sociology, Anthropology, and Engineering. Whenever there is a pairwise relation existing among any entities, graphs are then used to model the system. This paper deals with finding a central structure. The problem of finding a central structure is an active research area. They are classified under facility location problems. Using discrete mathematical models, centrality can be defined in several different ways. One of them is using the eccentricity of vertices. This concept uses the traditional Euclidean distance metric applied to the underlying graph. Centrality can also be defined through the topological properties of graphs. This paper deals with geodesic-convexity (g-convexity for short). g-convexity in graphs have been studied by several different authors. A good review is presented in our earlier paper [1]. In [1], we define the g-convex weight sequences for graphs based on g-convexity and provided characterization for certain classes of graphs including trees.

A central structure called the g-centroid is defined through g-convexity. In another paper [2], the author demonstrated an application of g-convexity and g-centroids in Mobile Ad hoc Networks (MANET). They also find applications in other areas, including measuring dissimilarities in dynamical systems and dynamic search in graphs. In [3], Prakash constituted a first to a systematic study on the size of convex sets in graphs. Due to its application, the location of g-centroid for any arbitrary graphs as well as its characterization had gained importance. In [4], we have demonstrated that the g-centroid location problem is -hard for disconnected graphs. In a later paper [2], Prakash closed the gap by proving -hardness for connected graphs.

As there are no tractable solutions available to locate the g-centroid for arbitrary graphs, it is essential to design an approximate solution for the location problem. A graph is defined as a composite graph if it can be obtained from two or more graphs through well-defined graph operations. Currently, there is no work available in the literature that analyze the relation between the structure of the g-centroid of a graph and its factors. In this paper, we study the structure of g-centroid and the g-convex weight sequences (gcws) of composite graphs through some popular graph operations such as graph-joins, cartesian products, and corona. Through the derived properties, we may able to design efficient approximate algorithms to locate the g-centroid for composite graphs in the future.

In this paper, we make the following contributions.

- We present an application of g-convexity and g-centroids in MANET. This forms a strong motivation. We then present an overview of the -hardness proof for the g-centroid location for arbitrary graphs.

- For the join of two graphs and , the weight sequence of the composite graph does not depend on the weight sequences of its factors; rather it depends on the incident pattern of the maximum cliques of and . We also characterize the structure of the g-centroid under various cases.

- For the Cartesian product of and and the prism of a graph, we establish the relationship between the composite graph and its factors.

- For Corona operations, we characterize the g-centroid based on its factors.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows.

In Section 2, we present preliminary definitions that are necessary for this paper. We also outline the -hardness algorithm for the g-centroid location problem. In Section 3, we present our main results. We consider three important types of graph operations in this paper. They are Graph Joins, Cartesian Products, and Corona. As a special case of Cartesian products, we considered the prism of a graph. Section 4 deals with the Conclusion and Future direction. In this section, we present two important open problems.

2. Definitions and Preliminary Results

In this section, we present some of the important definitions that are needed to understand the rest of this paper. Standard graph-theoretic definitions that are not given here; the reader may refer to the work in [5]. We now present a recent application of the g-convexity. A Mobile Ad hoc Network (MANET) is a decentralized type of wireless network. It is ad hoc in nature because it does not rely on any preexisting infrastructure such as an Access Point (AP) or a router to route packets from a source to a destination node. The network is formed in fly and mobile nodes may join and leave the network as they wish. Thus, there is no admission or access control mechanism in a MANET. Due to this nature, MANETs are deployed during emergency response operations. Wireless nodes that are within each other’s radio range communicate directly like a point-to-point network. There is no switch to facilitate communication as a wired network. Nodes that are not within the radio range of each other can still communicate, provided that intermediate nodes act as a router to rely on their packets. Thus, the network is formed through cooperation from all other nodes in the network. Due to this cooperative process, nodes lose their energy on forwarding packets on behalf of other nodes. This is in addition to their transmission and reception. A mobile node spends more than 60% of its power on transmission and reception compared with its internal processing. Thus, energy conservation is one of the important problems in MANET. Therefore, every node needs to know how many pairs of nodes that require its help in forwarding a data packet. Several routing protocols designed for MANET uses some form of the shortest path algorithm to forward packets between a pair of nodes. Thus, if a mobile node z lies in the shortest path between two other nodes u and v, then z is expected to route packets for u and v.

The following is one of the important problems in MANETs.

For a mobile node u, locating the maximum set S of nodes that can communicate with each other without the help of u.

WiFi interface is known to be a primary energy consumption in mobile devices. The “idle listening” consumes more energy compared with transmission or reception. It is estimated that about 60% of the energy is wasted in idle listening. The only solution for reducing idle listening is to implement a sleep schedule. Thus, intuitively whenever the nodes in S are communicating, u can go to sleep mode to conserve its battery power from idle listening.

MANET can be modeled as a simple undirected graph. An edge between the mobile hosts u and v indicates that both u and v are within their radio ranges. To simplify our discussion, we assume that if u is within the transmission range of v, then v will be in the transmission range of u (i.e., the relation between the nodes are symmetric. This may not be true in general due to different factors like the transmission power of a node, geographical conditions, etc.; thus, the resulting graph is a directed graph). Thus, the resulting graph is undirected.

We formally define the g-convexity and various parameters that are defined through the g-convexity.

Definition 1.

A set is geodetic convex (g-convex for short) if for every pair of vertices , all vertices on any shortest path (also called a geodesic path) belong to S.

From the above definition, it easily follows that a singleton set, vertex pair of an edge, and the whole vertex set are g-convex sets of G. We call them as trivial g-convex sets. Moreover, if S is a clique (S induces a complete subgraph of G), then S is a g-convex set of G.

A convex set is a set of vertices which is “closed” for the flow of information (routing, control, or data packets). This is in line with Mulder’s treatment of Interval functions in a graph [6]. For a connected graph G and two vertices u and v of G, the interval function is defined as follows; = {z:z lies on any geodesic path in G}. In our application terminology, contains the set of all vertices that may be involved in communication between u and v. Based on his definition, a set is g-convex if and only if for every pair .

We define the cardinality of the maximum g-convex set not containing u as the g-weight of u, denoted by . We then turn our attention to the set of nodes having the least weight. Intuitively, these nodes participate in more routes than others. We now formally define these parameters:

Definition 2.

Let G = (V,E) be any connected graph. For , the g-weight = max{: S is a g-convex set of G not containing v}. Let = min{: }. Then is called the g-centroidal number of G and the vertices v for which = are called the g-centroidal vertices. The g-centroid is the set of all g-centroidal vertices of G (i.e., g-centroid is a set of vertices which satisfies the min-max relation).

For , we denote by , any maximum g-convex set of G not containing v.

If the context is clear, we may call g-convexity and g-centroid by simply convexity and centroid.

Let G = (V, E) be a connected graph and . Then, the eccentricity is defined as = max {.

2.1. The G-Centroid Location Problem for Arbirtary Connected Graphs

The g-centroid location has several practical applications. One such application domain is MANET. It also has an application in measuring dissimilarities and information retrieval [5]. Due to its practical applications, it is thus necessary to devise an efficient algorithm to locate the g-centroid for an arbitrary graph. In this subsection, we outline the -hardness of the g-centroid location algorithm. For the detailed proof, the readers may refer to our original paper [2].

If the context is clear, in what follows, by the term graph we always mean a connected graph.

The following proposition specifies the structure of a g-centroid and its convexity.

Proposition 1.

For any connected graph G, is a g-convex set of G and is connected.

Based on this proposition, we have the following results.

Proposition 2.

For a connected graph G, lies in a block of G.

We now define the k-th neighborhood of a vertex u.

Let G = (V,E) be a connected graph and . The k-th neighborhood of u, denoted by consists of all vertices in G that are at a distance k from u, i.e., = {: }.

The next result is obvious from the definition of the k-th neighborhood of a vertex and its maximal g-convex set realizing its weight.

Proposition 3.

Let G be a connected graph and u be a vertex of G. If , then .

The following corollary is immediate from Proposition 3.

Corollary 1.

Let be a connected graph. For every vertex u in G, is either empty or induces a complete subgraph of G.

Note that for a vertex u of G, may be empty. As a nice open problem it will be interesting to classify all graphs for which , for every vertex u and any arbitrary . One such class is a tree.

We now outline the -hardness of the g-centroid location algorithm. The proof is by polynomially reducing the “clique decision” problem to the g-centroid location problem. However, we could not establish the membership of the g-centroid location problem in -class to establish the -completeness. g-convexity is closely related to the clique incident pattern of the graph.

We recall the definition of the “clique decision problem”:

Given a connected graph G and an integer r with , does G has a clique of size r?

The clique decision problem is one of the classical -complete problem in graph theory. Several graph-theoretic and optimization problems were proved to be -complete or -hard by reducing to the clique decision problem [7].

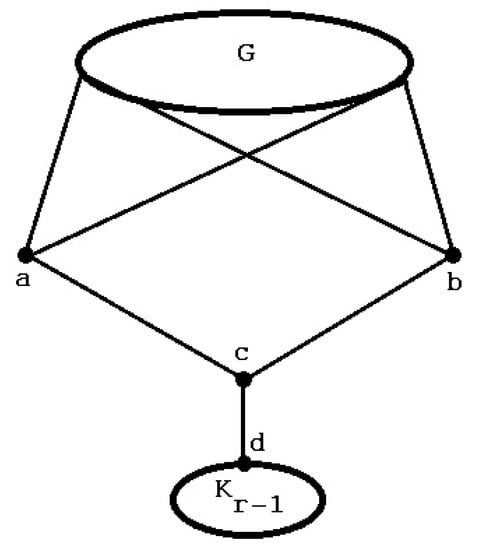

Definition 3.

For a given connected graph G and an integer r with , we construct the graph from a copy of G, (the complete graph on vertices) and three new vertices a, b, and c as follows.

- =

- The edge set of consists of all the edges of G, , and the following new edges.

- -

- Join a and b to all the vertices of G.

- -

- Join c to a and b and to some arbitrary vertex d of .

For a given graph G, the graph will look as in Figure 1. Furthermore, it is easy to see that for a given graph G and a r, , can be constructed in polynomial time. We explain this polynomial-time construction now:

Figure 1.

for a given graph G.

We may assume that the graph is stored as an “adjacency matrix”. To obtain , we need to add vertices that corresponds to and the three new vertices a, b, and c. This is done by adding rows and columns to the “adjacency matrix”. Creating adjacency entries that represents takes time. Joining a to all the vertices of G is obtained by setting 1 for all columns that correspond to the vertices of G. This can be done in linear time. Similarly, joining b to all vertices of G can be done in linear time. Joining c to a and b and to some arbitrary vertex d of can be done in a constant time. Thus, the entire construction of from G takes polynomial time.

For an arbitrary connected graph G, we now analyze the structure of the g-centroid of for various values of r.

In what follows in this section, if the context is clear, we assume that the graph under consideration is .

The following facts can easily be established.

Proposition 4.

Let G be a connected graph and be defined as in Definition 3. Let x be a vertex in the copy of of , then .

The proof follows from the fact that is complete and therefore .

Proposition 5.

Let G be a connected graph and be defined as in Definition 3. .

The next proposition specifies the weight of the two vertices a and b based on the maximum clique size of G.

Proposition 6.

Let G be a connected graph and be defined as in Definition 3. , where is the maximum clique size of G.

The following proposition determines the weight of the vertex c based on the chosen r and the maximum clique size of G.

Proposition 7.

Let G be a connected graph and be defined as in Definition 3. = max {, }, where .

We now determine the weight of every vertex . The weight of these vertices depends on the maximum clique incident pattern of G and the chosen r.

Proposition 8.

Let G be a connected graph and be defined as in Definition 3. Let be the maximum cliques of G, , and . Then, the following hold.

- If , then for every , = max {,}.

- If , then for every , = max {w,}. For every , = max {,}.

From the above propositions, for a given connected graph G and an integer r with , we can find the weight of every vertex of .

The following proposition analyze the structure of for various values of r.

Proposition 9.

Let G be an arbitrary graph with the maximum clique size = w. Let r be an integer such that . Let be defined as in Definition 3. Then, the g-centroid of , = or M, depending upon whether the intersection of all the maximum cliques of G denoted by M is empty or not.

The following two propositions relate the chosen r and the maximum clique size of G.

Proposition 10.

Let G be a connected graph with the maximum clique size = w and be defined as in Definition 3. Let . Then, = {c}.

Proposition 11.

Let G be a connected graph with the maximum clique size = w and be defined as in Definition 3. Let . Then, = , irrespective of whether M is empty or not.

Combining all the results for , we have the following theorem.

Theorem 1.

Let G be any connected graph and r be an integer such that . Let be defined as in Definition 3. Let be the maximum clique size of G. If , then = M or depending upon whether the intersection of all the maximum cliques of G denoted by M is non-empty or not. If , = , , = {c} irrespective of whether M is empty or not.

Based on Theorem 1, we can address the clique decision problem in polynomial time.

If , then the g-centroid of is either or M depending upon whether the intersection of all the maximum clique of G is empty of not. For , the g-centroid = . For , . Thus, G has a clique of size k if and only if or M.

3. Graph Compositions

In Section 2.1 we outlined the -hardness for a g-centroid location algorithm. It will be worth focusing on designing efficient approximation algorithms for the g-centroid location for a general graph or provide a polynomial-time algorithm for the g-centroid location for graphs with some special structure (such as chordal, interval, or unit disc graph). In this section, we analyze the structure of the g-centroid of composite graphs under some well-known graph operations. We now formally present some of the definitions of well-known graph operations:

Definition 4.

Let = (, ) and = (, ) be two graphs. Their join denoted by G = has the vertex set V = and the edge set E = {: }.

The Cartesian product G = has the vertex set V = and the edge set E is defined as follows; (, ) and (, ) are adjacent in G if and only if either = and or and = .

As a special case of the cartesian product, we have the prism of a graph. The prism of a graph is G = , where is a complete graph on two vertices.

The corona of two graphs and of order and (where = and = ), denoted by G = is the graph obtained by taking one copy of and copies of and joining the i-th copy of to the i-th vertex of , .

Remark 1.

If G is a composition of , , ⋯, , then we say that G is a composite graph and , , ⋯, are its factors.

We now analyze the g-centroids and gcws for composite graphs under the above-defined graph operations.

3.1. The Join of Graphs

In this subsection, we show that the weight sequence of G = does not depend on the weight sequence of and , rather it depends on the incident pattern of the maximum cliques of and .

If and are either complete or if both are incomplete, we give the weight sequence of G explicitly. If is complete and is incomplete, it is shown that for each , = , where K is a maximum g-convex set of not containing u.

The following Proposition is immediate from the definition of join of graphs.

Proposition 12.

Let and be two graphs and G = . Then, the following holds.

- G has an induced subgraph isomorphic to as well as to .

- G is complete if and only if both and are complete.

If both and are complete, then G is a complete graph on n = + vertices and the weight sequence of G is {} and = .

Now consider the case when and are incomplete. The following proposition determines the structure of a g-convex sets when both and are incomplete.

Proposition 13.

Let and be two incomplete graphs and G = . Then a proper subset S of is a g-convex set of G if and only if is a complete subgraph of G.

Proof.

Let S be a proper g-convex set of V. If possible, let u and v be two non adjacent vertices of G in S. From the construction of G, both u and v belong to either or . Let u and v belong to . Let z be any vertex of . Then u,z,v is a geodesic joining u and v in G. As S is convex, . Thus as z is arbitrary. As is incomplete, has a pair of non-adjacent vertices. Therefore by a similar argument, . Hence S = , which is a contradiction.

Proof of the sufficiency part follows trivially as cliques are always g-convex sets of G. □

Remark 2.

If M and N are the maximum cliques of and , respectively, then is a maximum clique of G.

We now characterize the g-convex sequences of graph joins based on the incident pattern of the maximum cliques of their factor graphs.

Proposition 14.

Let and be two incomplete graphs and G = . Let , , ⋯, and , , ⋯, be the maximum cliques of and , respectively, of sizes and . Let M = , N = , n = , = and = .

- If and , then the gcws of G is {,}

- If and , then the gcws of G is {, }

- If M and N are empty, then the gcws of G is {}.

Let u be a vertex of G. Then, by Proposition 13, induces a complete subgraph of G.

(1) Let M,. Let and . Then there exists an i, such that . Therefore () are maximum g-convex sets of G not containing x (as they are complete). Thus, = . Similarly, = also if and . If , then , and are maximum g-convex sets of G not containing x, of cardinality . Similarly if , then = . Therefore, the gcws of G is {,}.

Proofs of (2) and (3) are similar to the proof given above.

We now give the structure of under the above cases. If the first case of Proposition 14 is arises, then = and hence is a clique of G. In the second case, is either M or N depending upon whether N or M is empty. Thus in this case also is a clique. In the third case, G is self centroidal. Thus, the following corollary is obvious.

Corollary 2.

If and are incomplete graphs and G = , then is either a clique of G or the entire vertex set of G.

We now discuss the case when is complete and is incomplete. Here, we show that , where K is a maximum g-convex set in not containing u.

Proposition 15.

Let be a complete graph and be an incomplete graph and G = . Let . Then induces a complete subgraph of G.

The proof follows as in Proposition 13.

Proposition 16.

Let be a complete graph and be an incomplete graph and G = . Let . Then = , where K is a maximum g-convex set in not containing u.

Proof.

Let be a maximum g-convex set of not containing u. We show that S = is a g-convex set of G not containing u. Let x,y be a pair of non-adjacent vertices in S. Then, by our definition of G, x,. If , then for any , x,z,y is a geodesic joining x and y in G. Thus, in this case all geodesics lie in as . Suppose that = 2. Let x,z,y be any geodesic in G. If , then as otherwise , as is a g-convex set in . Thus, in this case also, all geodesics lie in . Therefore, S is a g-convex set of G. From the definition of g-weight, it follows that . To prove the equality, it is enough to show that for any , is a g-convex set of not containing u. Let K = .

First, we show that K is non-empty. If K is empty, then . As is incomplete, . Let v be a vertex of different from u. Then S = is a g-convex set of G, not containing u, properly containing . This is a contradiction.

Next we show that K is a g-convex set of . If K is a clique, then K is trivially a g-convex set. Let such that = 2. Let x,z,y be a geodesic joining x and y in . From the definition of G, = 2 and x,z,y is a geodesic joining x and y in G. By the convexity of , , and thus . Thus K is a g-convex set of . □

Next we describe the structure of when is complete and is incomplete.

Proposition 17.

Let be a complete graph and be an incomplete graph and G = . .

Proof.

Let . Then, by Proposition 15, induces a complete subgraph of G. Thus, = , where = . Let y be any vertex of and M be a maximum clique of , not containing y. Then, is a g-convex set of G not containing y and = . Thus, . Since y is arbitrary, we have . □

Corollary 3.

Let be a complete graph and be an incomplete graph and G = . Let ,, ⋯, be the maximum cliques of and N = . If , then = .

Proof.

If , then by the proof of the above Proposition, = . Let . Since , there exists an i, such that . Then, is a g-convex set of G not containing y with cardinality . Thus, , and therefore . □

Next, we describe the structure of under this case.

Proposition 18.

Let G = with complete and incomplete. Then induces a complete subgraph of G.

Proof.

From Proposition 17, . If = , then is complete. If = 1, then also is complete. Let . Let . We now show that . As = , for each vertex x of , we have = = (as ). If M is any maximum clique of , then (otherwise, is a g-convex set of G not containing them of cardinality ). As M is a clique, , and hence u and v are adjacent in G also. This proves that is complete. □

The proof for the following corollary is immediate from Proposition 18.

Corollary 4.

Let be a complete graph and be an incomplete graph and G = . Let ,, ⋯, be the maximum cliques of . If , then .

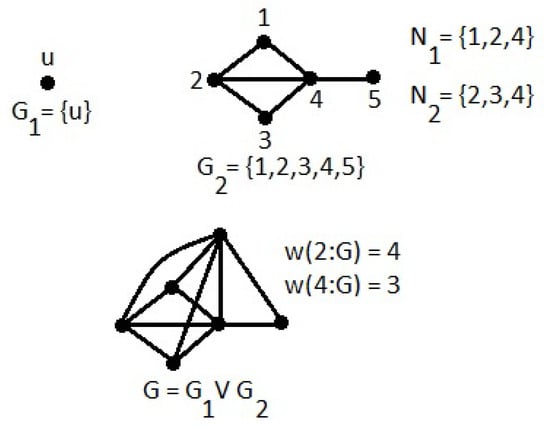

The containment can be proper. This is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The proper containment: .

Proposition 19.

Let be a complete graph and be an incomplete graph and G = . If , then .

Proof.

From the above corollary, . Thus all the maximum cliques of are contained in . Suppose that . Let . Then is a convex set of G (as any geodesic path passes through only vertices from ), geodesic contains vertices only from with cardinality . This is a contradiction. This proves that . □

3.2. Cartesian Product

In this section, we deal with the gcws of the cartesian product of two graphs. First, we prove that is a g-convex set in if and only if , where and are g-convex sets of and , respectively.

Proposition 20.

Let and be two connected graphs. Let G = . Then, is a g-convex set of G iff S = , where and are g-convex sets of and , respectively.

Proof.

Let S be any g-convex set of G. Let = {u: (u,v) } and = {v:(u,v) } (i.e., the projection of S on and ). Then, clearly . First, we show that S = . Suppose (u,v) and (u,v) . As and , by the definition of and , there exist x,y such that (u,x), (y,v) . Let u = ,, ⋯, be a geodesic in and , , ⋯, be a geodesic in . Then , , ⋯, , , ⋯, is a geodesic joining and in G. Since S is convex, , a contradiction. This proves that .

Our next task is to show that and are convex sets of and , respectively. Let and u = ,, ⋯, be any geodesic in . Let x be any arbitrary vertex in . Then , . Now, , , ⋯, is a geodesic joining and in G. Since S is convex, for , and therefore . Thus, is a g-convex set of . Similarly is a g-convex set of .

The proof of the sufficiency part follows trivially. □

Corollary 5.

Let and be two connected graphs. Let G = . Let and be g-convex sets of and respectively, then and are g-convex sets of G.

The proof follows from the above proposition and the fact that and are g-convex sets of and .

Proposition 21.

Let and be two connected graphs. Let G = . Let . Then the weight of is

Proof.

Let S be a maximum g-convex set of G not containing . Then, by Proposition 20, S = , where and are g-convex sets of and , respectively. Since , one of the following holds good.

- and

- and

- and

By the maximality of S, if , then is a maximum g-convex set of not containing u and similarly, if , then is a maximum g-convex set of not containing v. Thus case (1) cannot happen (as . In case (2), = and in case (3), = . Thus, we have

□

From the Proposition 21, we see that if and are known, then can be computed.

We now relate the centroid of G to those of and . We show that and the equality holds if .

Proposition 22.

Let and be two connected graphs. Let G = . Let = ; = ; = and = . If = , then = .

Proof.

Let . From Proposition 21, = max {,}. Let . Then, either or or both. In the first case . (as ). Similarly, in all the other cases, we can show that . Therefore, = . □

Remark 3.

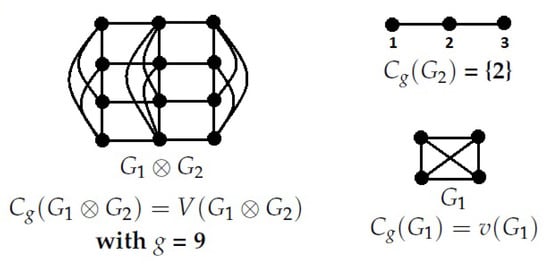

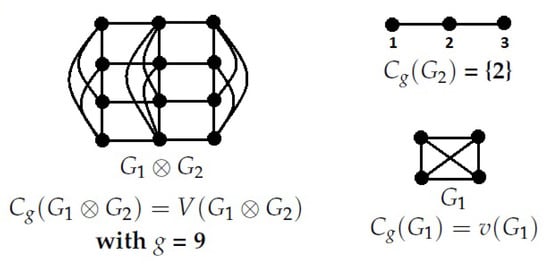

The converse of this proposition is not true. For, consider G = . Here, = 1, = 2, = 1, and = 3. Clearly but = .

Proposition 23.

Let and be two connected graphs. Let G = . Let = ; = ; = and = .

If , then .

Proof.

Let . From Proposition 10, = max{,}. Without loss of generality, assume that = . Let . if and , then (as and is a g-convex set of G not containing ). If and , then (as ). Therefore in this case . If , then = max{,} = . Thus for all , for every and . This proves that . □

Remark 4.

It can easily be seen that the containment can be proper. This is illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The proper containment of Proposition 23.

3.3. Prism of a Graph

As a special case of the cartesian product, we consider the prism of a graph. Let G be any connected graph. Take two copies of G, say and . Label the vertices of the first copy with ,,⋯, and the second copy with ,,⋯, in the same order. Then, the prism of G denoted by has the vertex set and the edge set defined as follows:

Remark 5.

It is easy to see that the prism of a graph is the cartesican product of itself with . That is, = .

Proposition 24.

Let G be a connected graph and . Then, = max { , }.

The proof follows from the above remark and Proposition 21.

Proposition 25.

Let G be a connected graph and g = . If , then = {, i = 1,2: }; otherwise = .

Proof.

Let . Let . Then, . Therefore, from Proposition 24, = = n. Similarly if is any vertex of G with , then also = = n. If is any vertex of G with , then = . Thus, in this case, = {: }.

Proof of the other part follows similarly. □

3.4. The Corona

In this section, we deal with the corona of two graphs. Let G be the corona of with . Then, we prove that = .

Proposition 26.

Let G = . Let and . Then,

- = and

- = , where S is a maximum g-convex set in not containing v.

Proof.

(1) Let be any maximum g-convex set of not containing u. i.e, = . We now show that S = is a g-convex set of G.

If , then and all geodesics will lie in (as ).

Let . In this case, if , then is the only geodesic joining x and y in G, and by our definition of S, . If , then as before and if is any other geodesic joining in G, then clearly . Therefore, in all these cases, all geodesics lie in .

Let and with . In this case it is easy to see that if P is a geodesic joining i and j in , then is a geodesic joining x and y in G and conversely. Since , all geodesics lie in . Thus all geodesics lie in .

Proof of the case when and is similar to that of the above case.

Thus the convexity of S is established. Obviously, S does not contain u. The reason that every such g-convex set S of G arises this way follows from the fact that = is a g-convex set of not containing u and every is a g-convex set of G. A maximum g-convex set of G not containing u is obtained by taking for a maximum g-convex set of not containing u; that is an . This establishes (1).

(2) Let . Let be a maximum -convex set in not containing v. Then as before by considering various cases, we can prove that is a g-convex set of G not containing v. If S is a maximum g-convex set of G not containing v, then trivially is a -convex set in not containing v. Therefore = . □

In the case of the corona, we prove that the g-centroid of G and are the same.

Proposition 27.

Let , be two connected graphs. Let G = . Then, .

Proof.

Let . Then = (by (1) of the above proposition). If y is any vertex not in , then (as ). If , then is a convex set of G not containing z with cardinality . Therefore . For any , = = . Thus . Therefore . □

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

In this paper, we have considered the join of graphs and have shown that the gcws of G = depends on the intersection pattern of the maximum cliques of and .

For cartesican products, we have proved that is a convex set of G iff S = , where and are convex sets of and , respectively, and deduced that . As a special case of this, we have considered the prism of a graph.

Finally, we have dealt with the corona of a graph with another and shown that the centroid of the corona is that of the farmer graph.

There are several other important graph compositions such as wreath products, normal products (see [8]. Cf. 3), etc. Establishing the relation between the gcws and the g-centroid of the composite graph and its factor graphs under these graph operations is an interesting open problem in this area. It is also interesting to classify all classes of graphs such that for any arbitrary member graph G, for all . One such member class is trees.

The concept of convexity may be extended to directed graphs. It will be interesting to study the algorithmic complexity of g-centroid location algorithm for certain classes of directed graphs such as “strongly connected graphs”.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Veeraraghavan, P. g-Convex Weight Sequences. Mathematics 2018, 6, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeraraghavan, P. Application of g-Convexity in mobile ad hoc networks. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE International Conference on Information Technology in Asia 2009 (CITA’09), Kuching, Malaysia, 6–9 July 2009; pp. 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, V. Convexity Studies in Graphs. Ph.D. Dissertation, Indian Institute of Technology, Madras, India, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rangan, C.P.; Parthasarathy, K.R.; Prakash, V. On the g-centroidal problem in special classes of perfect graphs. Ars Comb. 1998, 50, 267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Bukley, F.; Harary, F. Distance in Graphs; Addison-Wesley: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Mulder, H.M. The Interval Function of a Graph; Mathematisch Centrum: Amsterdam, The Netherland, 1980; Volume 132. [Google Scholar]

- Garey, M.R.; Johnson, D.S.; Klee, V. (Eds.) Computers and Intractability: A Guide to the Theory of NP-Completeness; A Series of Books in the Mathematical Sciences; W. H. Freeman and Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Parthasarathy, K.R. Basic Graph Theory; Tata McGraw-Hill: New Delhi, India, 1994. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).