Abstract

This paper presents a broad study on the evaluation of explanatory capabilities of machine learning models, with a focus on Decision Trees, Random Forest, and XGBoost using a pancreatic cancer data set. We use Human-in-the-Loop-related techniques and medical guidelines as a source of domain knowledge to establish the importance of the different features that are relevant to select a pancreatic cancer treatment. These features are not only used as a dimensionality reduction approach for the machine learning models but also as a way to evaluate the explainability capabilities of the different models using agnostic and non-agnostic explainability techniques. To facilitate the interpretation of explanatory results, we propose the use of similarity measures such as the Weighted Jaccard Similarity coefficient. The goal is to select not only the best performing model but also the one that can best explain its conclusions and better aligns with human domain knowledge.

MSC:

68T01; 68T05

1. Introduction

Explainable AI (XAI) [1] is a field of research dedicated to enhancing the comprehensibility of Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems overall, with a specific focus on machine learning (ML) systems.

XAI brings numerous benefits, including bolstering confidence in model predictions through increased transparency in decision-making processes, facilitating responsible AI advancement, assisting in the detection and resolution of errors, and enabling thorough auditing of AI models to ensure compliance with regulatory standards.

The inherent explainability of AI systems has not remained static but has changed considerably as a result of technological progress. In fact, explainability has become an increasingly difficult issue to tackle, as the internal functioning of AI systems has become less intelligible as they have become more complex [2].

At first, symbolic AI models were inherently explainable. For instance, rule-based expert systems could readily display to users the specific rules they adhered to in reaching a particular decision, even when these rules encompassed elements of uncertainty and imprecision, as seen in fuzzy systems. Such AI models are often deemed transparent, indicating that the model’s operations are easily comprehensible [3]. Transparency entails the capacity of a model to enable human understanding of its function without necessitating an explanation of its internal structure or the algorithmic processes it employs to handle data internally [4].

However, rule-based systems presented too many limitations that hindered their development: they were rigid, with poor scalability and limited learning capabilities. To overcome the problems associated with symbolic AI, machine learning models were developed. Instead of following rigid programming, these models autonomously refine their accuracy through continuous exposure to data. They are obviously very dependent on data to obtain their results, but, in general, their performance, scalability, and generalization features are superior to those present on symbolic models.

But these machine learning models often lack interpretability. Some of them can be considered transparent, such as Logistic Regression or Decision Trees, but these are usually the simplest models that offer lower performance in complex domains. It is evident that more sophisticated models, incorporating Random Forest and deep learning algorithms, tend to be opaque in nature.

We can see that there seems to be a trade-off between model interpretability and model performance. Less interpretable models tend to perform better than more interpretable ones.

Therefore, the main question is not whether it is possible to arrive at explainable solutions—this has been true for a long time—but whether it is possible to obtain explainable solutions with an accuracy that is comparable to the highly effective but comparably opaque deep learning systems [2].

In an attempt to include explainability in the opaque models, “agnostic” techniques have been developed. These techniques might be applied to any machine learning (ML) model, irrespective of its internal processing or internal representations [3].

The issue with these agnostic explainability methods is their consistency. As noted by some authors [5], these systems have been found to be inconsistent, unstable, and to provide very little insight into their veracity and trustworthiness. They have also been identified as computationally inefficient. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a method of validating the explanatory capabilities obtained by these models, especially in complex domains such as medical environments, where it may not be easy to determine the correct answer to a given problem.

In this article, we face a problem related to pancreatic cancer, deciding the best treatment for a patient given his or her clinical characteristics. Since our data set is tabular in nature and does not have too many cases, we decided to try to solve the problem using classical machine learning models, such as Decision Trees (DT) [6], Random Forest (RF) [7], or XGBoost models [8]. We have already seen that DT are transparent models, but RF and XGBoost are opaque.

Since we are in a medical domain, we understand that the models must offer adequate explainability, but how can we validate the results? The first way would be to apply different methods of explainability on the same model and compare the results with each other, analyzing their coherence. But we want to go further and check if the explainability of the models has medical significance, which would allow us to have more trust in them.

To verify the medical significance, we can rely on the opinions of medical experts and also use medical guidelines that act as a “gold standard” in the field. The former option involves some kind of Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) approach [9], which is often a complex process and requires the active participation of human experts. The latter option relies on bibliography and manuals, which tend to be exhaustive and sometimes hard to navigate through.

The contribution of this paper is, in addition to the comparison between methods of explainability, the development of different ways of evaluation of explainability models based on the collaboration of human experts and the guidelines available in the domain—using similarity metrics—and its application to a pancreatic cancer treatment problem.

The content of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines current knowledge in the field of explainable AI and briefly explains our current domain: pancreatic cancer. Section 3 describes the data set used and the methodology followed that includes a description of the feature selection process, the different ML models used, and the different XAI methods considered. Section 4 describes the results obtained by each ML model using different feature sets in terms of accuracy but also in terms of interpretability. The discussion (Section 5 is concluded with the presentation of the conclusions in Section 6).

2. State of the Art

This section introduces the explainability concept and important related aspects, followed by an introduction of the application domain.

2.1. Explainability

Explainable AI is frequently characterized as a set of methodologies that facilitate the comprehension, reliable reliance, and adept oversight of machine learning systems by human users.

The terms “explainability” and “interpretability” have often been used in the literature as synonyms. However, researchers such as Gilpin et al. [10] argue that explainability goes beyond mere interpretability. Explainable models are interpretable by nature, but the opposite is not necessarily true. To be explainable, models must be auditable and capable of defending their actions and offering relevant responses to inquiries. In this regard, authors such as Lipton [11] seek to refine the discourse on interpretability and question the commonly accepted idea that linear models are interpretable and that deep neural networks are not. The aim is to refine the discourse on interpretability and challenge the commonly held views that linear models are interpretable and that deep neural networks are not.

When analyzing explainability methods, we have to take into account how to characterize these methods. A first division can be made regarding scope and generality [12]. In scope we can classify the methods as

- Local: Try to elucidate the rationale behind the model’s specific prediction for a particular instance or a group of proximate instances.

- Global: Try to comprehend the overall behavior of the model.

Regarding generality, we can classify methods as

- Model-Agnostic: These methods function independently of the specific ML model employed; they can be implemented across a range of models, irrespective of their architecture or underlying algorithms. They use techniques such as perturbing input features and observing the impact on model predictions.

- Model-Specific: These methods are tailored to a particular type of ML model and exploit the model’s internal structure and characteristics to provide explanations. The complexity of these methods depends on how transparent the models are.

Building trust is a key pillar when creating AI systems intended to work in collaboration with humans. Without an understanding of how those systems make their decisions, humans will not trust them [13], especially in domains such as defense, medicine, finance, or law, where trust is an essential aspect. As pointed out by Adadi and Berrada [14], the delegation of significant decisions to a system that lacks the capacity to provide a coherent explanation of its own processes and functions is a practice that is fraught with obvious dangers.

2.1.1. Explainability in Healthcare

In the specific domain of our research, that is, healthcare, Holzinger et al. [15] remarked that if medical professionals are complemented by sophisticated AI systems, they should have the means to understand the machine decision process. Also they investigated the requirements for building explainable AI systems for the medical domain [16]. First of all, we must emphasize that, given the criticality of the domain, humans must be able to understand and actively influence the decision processes. Regulatory aspects must also be considered (e.g., the GDPR of the European Union), as well as legal ones (e.g., the written text of medical reports is legally binding). Holzinger et al. [16] argue that for this domain at least, the only way forward appears to be the integration of knowledge-based approaches (due to their interpretability) and neural approaches (due to their high efficiency). In particular, authors recommend hybrid distributional models combining sparse graph-based representations with dense vector representations, linking to lexical resources and knowledge bases.

When citing examples of explainability, we can refer to a review of the XAI literature of the last decade in healthcare by Loh et al. [17], as well as some recent specific cases where it has been applied on medical ML models; for example, a two-stage prognostic framework for renal cell carcinoma [18], a diagnostic classification model for brain tumor detection [19], a multi-label classification of electrocardiograms [20], and a breast cancer survival model [21]. We found more examples of the medical imaging field using deep learning cancer detection models [22], or in skin cancer recognition methods [23].

In fact, the vast majority of the high-impact literature on XAI started to appear in 2018, since that was when interest in XAI really began to take off. In the reviewed literature, the most used technique by far was SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP), followed by Gradient-Weighted Class Activation Mapping (GradCAM). SHAP is especially popular for traditional ML models, and Loh et al. [17] conclude that “SHAP has the potential to be used in healthcare by analyzing the contribution of biomarkers or clinical features (players) to a specific disease outcome (reward)”. The next most used technique was GradCAM, which, unlike SHAP, was overwhelmingly popular for deep learning models and suitable for visual explanations. The remaining techniques reported in the literature were LIME, rule-based systems, layer-wise relevance propagation (LRP), case-based reasoning (CBR), explainable boosting machine (EBM), heatmaps, and saliency map generation approaches [17].

2.1.2. Problems with Explainability Methods

Explainability is not immune to criticism. As Slack et al. [5] have noted, the efficacy of explainability methods is questionable due to their inconsistent and unstable nature, which provides minimal insight into their reliability and correctness. Furthermore, there are no reliable metrics to ascertain the quality of the explanations, and the existent ones rely heavily on the implementation details of the explanation method and do not provide a true picture of the explanation quality [24].

Other authors such as Bhatt et al. [25] have conducted studies on the manner in which explainability techniques are utilized by organizations that employ machine learning (ML) models within their operational processes. They are focused on the most popularly deployed local explainability techniques: feature importance, counterfactual explanations, adversarial training, and influential samples. These techniques elucidate the rationale behind individual predictions, thereby rendering them the most pertinent form of model transparency for end users. The authors of the study found that while ML engineers are gradually incorporating explainability techniques as a form of quality control during the development process, there are still substantial limitations to existing techniques that prevent their direct use to inform end users. These limitations encompass the necessity for domain experts to evaluate explanations, the potential for spurious correlations reflected in model explanations, the absence of causal intuition, and the latency in computing and presenting explanations in real time.

In Dimanov et al. [26], the authors present a method for modifying a pre-trained model that can be used to manipulate the output of many popular feature importance explanation methods with minimal impact on accuracy. This demonstration highlights the potential risks associated with relying on these explanation methods. This research suggests that the prevalent explanation methods employed in real-world settings are often incapable of accurately determining the fairness of a model.

All these approaches work on the model to demonstrate their findings, but there are also recent works that demonstrate the downsides of the post hoc explanation techniques modifying the inputs [27,28,29]. In this sense, perturbation-based explanation methods such as LIME and SHAP are subject to additional problems: results vary between runs of the algorithms [24,30,31,32], and hyperparameters used to select the perturbations can greatly influence the resulting explanation [24].

This leads us to wonder how reliable these explainability techniques are and to what extent we can rely on them in complex environments such as medical settings. As commented by Bhatt et al. [25] in these scenarios, it is necessary to rely on the collaboration of domain human experts to verify that both the models and the explainability mechanisms are doing the right thing.

2.1.3. Frameworks for Explainability Assessment

In this paper, we have developed a method to validate explainability techniques using the Weighted Jaccard Similarity index. This approach addresses the need to evaluate machine learning models not only by their performance but also by how well their reasoning aligns with human domain knowledge. In the bibliography, we can find several similar frameworks and metrics that have been developed to evaluate and compare explainability methods by measuring their alignment with ground truth or human reasoning. All of them are fairly recent, indicating a clear growing interest in the area.

For example, we have the Explanation Alignment Framework [33], which quantifies the correctness of model reasoning by measuring the aggregate agreement between model and human explanations. Another one is PASTA (Perceptual Assessment System for explanaTion of Artificial Intelligence) [34], a human-centric framework designed for computer vision that uses a large-scale data set of human preferences to automate XAI evaluation. EvaluateXAI [35] is a framework specifically designed to assess the reliability and consistency of rule-based XAI techniques (such as PyExplainer and LIME) using granular-level metrics. We can also find benchmarks like CLEVR-XAI [36] that use synthetic data where the ground truth is programmatically defined to test if XAI exactly identifies the correct features.

There are several differences between our approach and these techniques that make our approach the most appropriate for the problem we are dealing with. For example, Explanation Alignment typically measures the agreement between a model’s explanation and human-generated rationales on a large scale and is focused on images. Our approach also uses formal clinical guidelines as the ground truth. This is more “authoritative” than individual human annotations because it represents an established scientific consensus, which is critical for clinical adoption in high-stakes fields like pancreatic cancer treatment. PASTA is also focused on computer vision. EvaluateXAI focuses on the technical robustness of the methods, checking if the explanation changes if you slightly perturb the input or if the rules generated are logically consistent. Finally, CLEVR-XAI is more like a general-purpose benchmark, but it is not specifically for our problem.

We can summarize the differences of all these methods with our approach by saying that our method is highly specialized for tabular medical data and aligns with standardized clinical guidelines. Our use of the Weighted Jaccard index is particularly effective for features that have a clear hierarchy of importance. It moves beyond “Does the human like the explanation?” or “Is the explanation stable?” to ask: “Does the model’s logic comply with established medical protocols?”.

2.2. Application Domain: Pancreatic Cancer

In the context of industrialized nations, pancreatic cancer holds a significant position as it stands as the seventh most prevalent cause of cancer-related deaths. It produced approximately half a million cases and caused almost the same number of deaths (4.5% of all deaths caused by cancer) in 2018 [37].

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma represents the most prevalent form of pancreatic cancer, accounting for over 80% of cases. The disease originates in the cells of the pancreas ducts, which facilitate the transport of juices containing digestive enzymes into the small intestine. There are several risk factors to consider, including a family history of the disease, a history of chronic inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis), Lynch syndrome, diabetes, being overweight or obese, and smoking [38].

In the current medical landscape, surgical resection remains the sole treatment modality that offers a potential cure for pancreatic cancer. Moreover, the incorporation of chemotherapy in the adjuvant setting has been demonstrated to enhance survival rates [39].

The application of AI in the healthcare domain, and particularly to pancreatic cancer, has spread widely in recent years. It is highly demanded and could be applied in different scenarios, ranging from early cancer diagnosis [40,41], classification of lesions [42], or survival prediction [43,44].

Although there are many successful examples of AI applied to pancreatic cancer [45], several challenges remain unsolved, such as the lack of a sufficient volume of data on the experiments carried out by different research teams to statistically validate their results [46].

2.2.1. Cancer Staging

The process of determining the extent of cancer in a patient’s body and ascertaining its precise location is referred to as cancer staging. It allows for the establishment of the severity of the cancer based on the main tumor and also for a diagnosis if there are other organs affected by the cancer.

The correct diagnosis of cancer and its staging are key factors in understanding the patient’s situation and establishing a treatment plan. It also serves as a basis for communication between physicians and patients. The most widely used staging system worldwide is TNM staging, which was proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) [47] and the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) to serve as the standard staging system [48], as referenced in the literature.

The meanings of T, N, and M for pancreatic cancer are explained below:

- T: Tumor size and possible growth outside the pancreas into nearby blood vessels.

- N: Cancer spread to nearby number of lymph nodes.

- M: Cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs (metastasized) such as the liver, peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), lungs, or bones.

Furthermore, based on the clinical stage of the main tumor, pancreatic cancer is classified into four types:

- Stage 0: Cancer is present but it has not spread.

- Stage I (no spread or resectable): Cancer is limited to the pancreas and has grown 2 cm (stage IA) or its size is greater than 2 cm but less than 4 cm (stage IB).

- Stage II (local spread or borderline resectable): The cancer is limited to the pancreas and its size is greater than 4 cm, or there is spread locally to the nearby lymph nodes.

- Stage III (wider spread or unresectable): Cancer may have expanded to nearby blood vessels or nerves but has not metastasized to distant sites.

- Stage IV (metastatic): Cancer has spread to distant organs.

This classification creates a common understanding among the medical experts, and provides us with several features to build ML models based on them.

2.2.2. Pancreatic Cancer Medical Guidelines

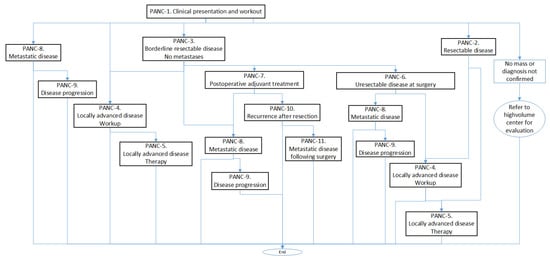

In this work, we have used the “Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma—NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology” [49], which is one of the most widely used guidelines by oncologists for the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic cancer. These guidelines are organized in processes (PANCs) that can be performed at different stages of diagnosis and treatment, for example, when there is a clinical suspicion of pancreatic cancer (PANC-1), when the cancer is resectable (PANC-2), when the cancer is borderline resectable (PANC-3) or unresectable (PANC-4), and so on.

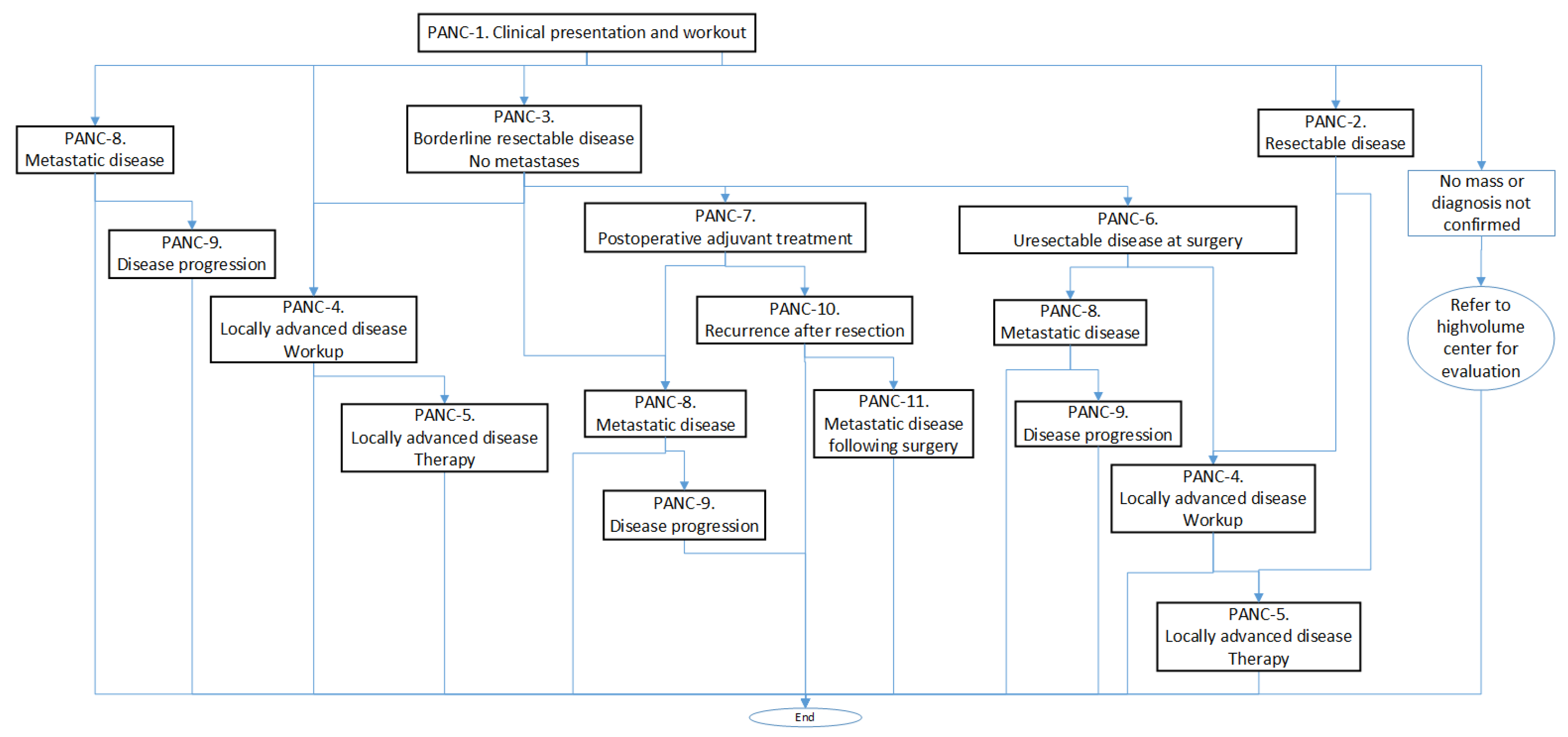

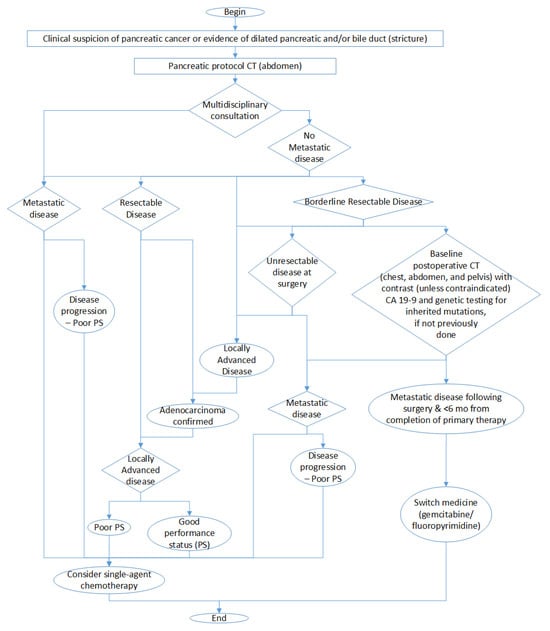

Each PANC is organized in a sort of algorithm represented by a flowchart with the different tasks to be performed. For example, in Figure 1, we can see the calling scheme between different PANCs, and in Algorithm 1, we can see a summary of the contents of PANC-1.

Figure 1.

Calling scheme between the different processes (PANCs).

Following this guideline, we can observe, in the procedure corresponding to the clinical presentation and workup, the four main diagnostic groups that are used to establish the treatment to be followed and that correspond with the stages presented in the Cancer Staging Subsection (Section 2.2.1):

- Resectable disease. In this case, the guidelines suggest proceeding with surgery (without neoadjuvant therapy) or endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy if neoadjuvant therapy is considered and if not previously done, and they consider stenting if clinically indicated.

- Borderline resectable disease. Here, an endoscopic ultrasound-guided biopsy is preferred (if not previously done), and a staging laparoscopy and baseline CA19-9 (important biomarker for pancreas cancer) are considered.

- Locally advanced disease. In this case, a biopsy should be performed if not previously done, which may result in (a) cancer not confirmed, (b) adenocarcinoma confirmed, and (c) other cancer confirmed.

- Metastatic disease. According to the guidelines, the following measures should be taken: (a) In cases of jaundice, a self-expanding metal stent should be placed. (b) Genetic testing should be performed for any inherited mutations, if not previously conducted. (c) Molecular profiling of tumor tissue should be conducted, if not previously performed.

| Algorithm 1 Clinical presentation and workup (PANC-1) [49] |

-Clinical suspicion of pancreatic cancer or evidence of dilated pancreatic and/or bile duct (indicators: age, gender) -Pancreatic protocol CT (abdomen) -Multidisciplinary consultation if No metastatic disease then Medical tests: * Chest and pelvic CT * Consider endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) * Consider MRI as clinically indicated for indeterminate liver lesions * Consider PET/CT in high-risk patients * Consider endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with stent placement * Liver function test and baseline CA19-9 after adequate biliary drainage * Genetic testing for inherited mutations if diagnosis confirmed Possible outcomes: * Refer to high-volume center for evaluation * Resectable Disease, Treatment (indicators: primary diagnosis, site of resection or biopsy) * Borderline Resectable Disease, No Metastases (indicators: primary diagnosis, site of resection or biopsy) * Locally Advanced Disease (indicators: primary diagnosis, site of resection or biopsy) * Metastatic Disease, First-Line Therapy, and Maintenance Therapy else if Metastatic disease then Metastatic Disease Biopsy confirmation, from a metastatic site preferred Medical test: * Genetic testing for inherited mutations * Molecular profiling of tumor tissue is recommended * Complete staging with chest and pelvic CT Outcomes: (indicators: primary diagnosis, site of resection or biopsy) * Metastatic Disease: First-Line and Maintenance Therapy end if |

In this context, it should be borne in mind that many of the diagnostic tests require a multidisciplinary consultation, including an appropriate set of imaging studies, which implies that the diagnostic and treatment process is often subject to the heuristic knowledge of oncologists.

Algorithm 1 also shows a first approximation to the main indicators in the steps of the diagnosis and treatment process. In addition, after the interdisciplinary consultation, in the case of non-metastatic disease, the size and extent of the tumor (pathologic T), the number of nearby lymph nodes that are cancerous (pathologic N), the presence of metastases (pathologic M) and, from these, the pathological status is considered in the treatment of unresectable disease at surgery (for cases of resectable disease and borderline resectable disease) and in the treatment of locally advanced disease.

3. Data and Methodology

In this section, we describe the data set used to illustrate the use case, and then we detail the process followed to evaluate the different ML models and explainability techniques.

3.1. Data Set

The data set utilized in this study was obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas Program [50], a collaborative endeavor between the United States National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute. The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) is a seminal cancer genomics program that has sequenced and molecularly characterized over 11,000 cases of primary cancer samples.

One of the projects included in the program is called TCGA-PAAD, which is focused on pancreatic cancer. This project provides 185 diagnosed cases with the necessary details to carry out its complete analysis. For instance, the following elements are included: the “stage event,” which delineates the pathological state of the tumor; “clinical data,” which characterizes the tumor’s attributes; and the occurrence of “new tumor events,” which details the patient’s subsequent monitoring.

We have only considered 181 cases, since the remaining 4 were incomplete. In contrast with some of our previous research work, we have avoided data augmentation. The motivation is to avoid falsifying or obscuring the results of the interpretability measurements. In this case, we are more concerned with analyzing the reliability of the explanations than improving the accuracy of the models.

From the 181 cases considered, 117 received chemotherapy treatment. Each of the cases has a total of 158 features, ranging from family history data to treatment and follow-up information. It should be noted that the data set includes demographic variables such as age and gender, which, in other contexts, may introduce bias in the system. However, neither the guidelines nor the medical experts consider those attributes relevant for this particular problem and, typically, they are ultimately omitted from the decision process.

3.2. Feature Selection

For our experiment, we did a meticulous feature selection process in which only those features that added relevant information to the use case of whether to apply a chemotherapy treatment were selected [39].

As a first step, we analyzed the data set with all available information. Even if the data provided by the PAAD repository allowed us to upload many variables for each patient case, the projects that had collaborated with the institution did not provide all the information possible.

The second step was a pruning process performed over the features without information or with very few informed cases. We removed unnecessary data as the PAAD database includes many variables that do not intervene in the treatment decision process. Moreover, some information provided on the data set was redundant, for example, the size of the tumor, which can be inferred from the TNM diagnosis (as commented in Section 2.2.1), so we eliminated the unnecessary data.

Finally, we asked a panel of oncologists, who participated as human experts, to select only the features they considered relevant to treatment selection in pancreatic cancer patients. Our goal in including human experts in the feature selection process was not only to obtain the best features for the ML process but also to improve the explanatory power of the resulting models. Ref. [51] described another contribution of human experts, which collaborated in the data augmentation process carried out with the aim of improving the performance and generalization capabilities of the models developed.

Our group of oncologists typically works by consensus. In order to avoid subjective biases, each feature is collectively discussed by the panel until a final decision is made. After the expert selection and pruning process, we ended up with a set of recommended features and the target variable which is the therapy type. From this set of recommended features, we created two other sets of features—maximum and minimum—as explained below.

3.2.1. Recommended Set

The inclusion of expert knowledge in the training of ML models can help to obtain better results and improve their interpretability. In this work, we first consider the collaboration of experts during the feature engineering process. We asked a panel of medical doctors to rate the relevance regarding the prescription of chemotherapy treatment, of the 27 features selected during the feature selection process. Each feature should receive a value between 1 and 3, 1 being highly relevant, 2 being relevant, and 3 being barely relevant.

From the results provided by the medical experts, we extracted a set of recommended features that includes those features that received a value of 1 or 2. Among the features selected by the experts, three of them were dependent on the treatment prescribed, so we also decided to remove them from the set as the objective is treatment prescription. They were namely the primary therapy outcome success, new tumor events, and days to new tumor event after the initial treatment.

The details of the 14 features selected, the expert value received, and a brief description extracted from the GDC Data dictionary (https://docs.gdc.cancer.gov/Data_Dictionary/viewer/, accessed on 5 January 2024) are shown in Table 1. The descriptions of the different features uses the criteria established by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).

Table 1.

‘Recommended’ set of features.

3.2.2. Maximum Set

From this point, we explore two different alternatives: (1) adding all available information and (2) reducing the set of features to a minimum.

We enhance the feature set, adding all the available information gathered (i.e., all 27 features). This data included the therapy outcome success, the new tumor events, and the days to new tumor, which are relevant for the medical doctors but happen after the treatment has been administered. Even if some features were “barely relevant” for medical doctors, there are studies in which some evidence is assigned to them as risk factors for pancreatic cancer as it is a case of gender, race, or ethnicity [52,53].

The idea behind this was to retain all the information available for the development of the ML models, so they can detect complex relationships among the features and ultimately produce a robust model. Therefore, we added 13 more features to our recommended set (shown in Table 2), ending up with the maximum feature set. The criteria for ethnicity or race are based on the categories defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Business and used by the U.S. Census Bureau.

Table 2.

Features added to the ‘maximum’ set (jointly with those presented in Table 1).

3.2.3. Minimum Set

The other option explored was to reduce the dimensionality of the recommended set of features, as some of the features already include valuable information about the status of the cancer and they are set as part of the medical diagnosis. It is the case, for example, of the pathologic T that informs the size of the tumor or the pathologic M that indicates whether metastasis has occurred (see Section 2.2.1). The stage is also established during the evaluation of the cancer. Furthermore, the patient’s age is a significant factor in the decision-making process concerning the administration of chemotherapy [54], and it has also shown evidence in other types of cancers [55]. Therefore, we ended up with five features (age, T, N, M, and stage) that we can see in Table 3, along with their range of values. We considered the minimum set of features as a dimensionality reduction with the goal of transforming high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional representation without losing any important information.

Table 3.

Minimum set with the range of values.

3.2.4. Features and Guidelines

In order to evaluate feature importance, we decided to follow the medical guidelines from the “Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma—NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology” [49] to see how they consider each feature in terms of importance. As we have seen in Figure 1 and Algorithm 1, these guidelines are quite complex and detail the sequential management decisions and interventions regarding pancreatic cancer, providing recommendations for some of the key issues in cancer prevention, screening, and care.

Therefore, feature importance regarding chemotherapy treatment is not clearly specified in these guidelines, so it is necessary to carry out a process of knowledge elicitation that allows us to extract such information. For this purpose, we analyzed the different procedural sheets into which the guideline is divided, taking into account that the same sheet can be considered in different diagnostic lines. This implies that successive tests may involve refinements or changes in determining the diagnosis and treatments to be used.

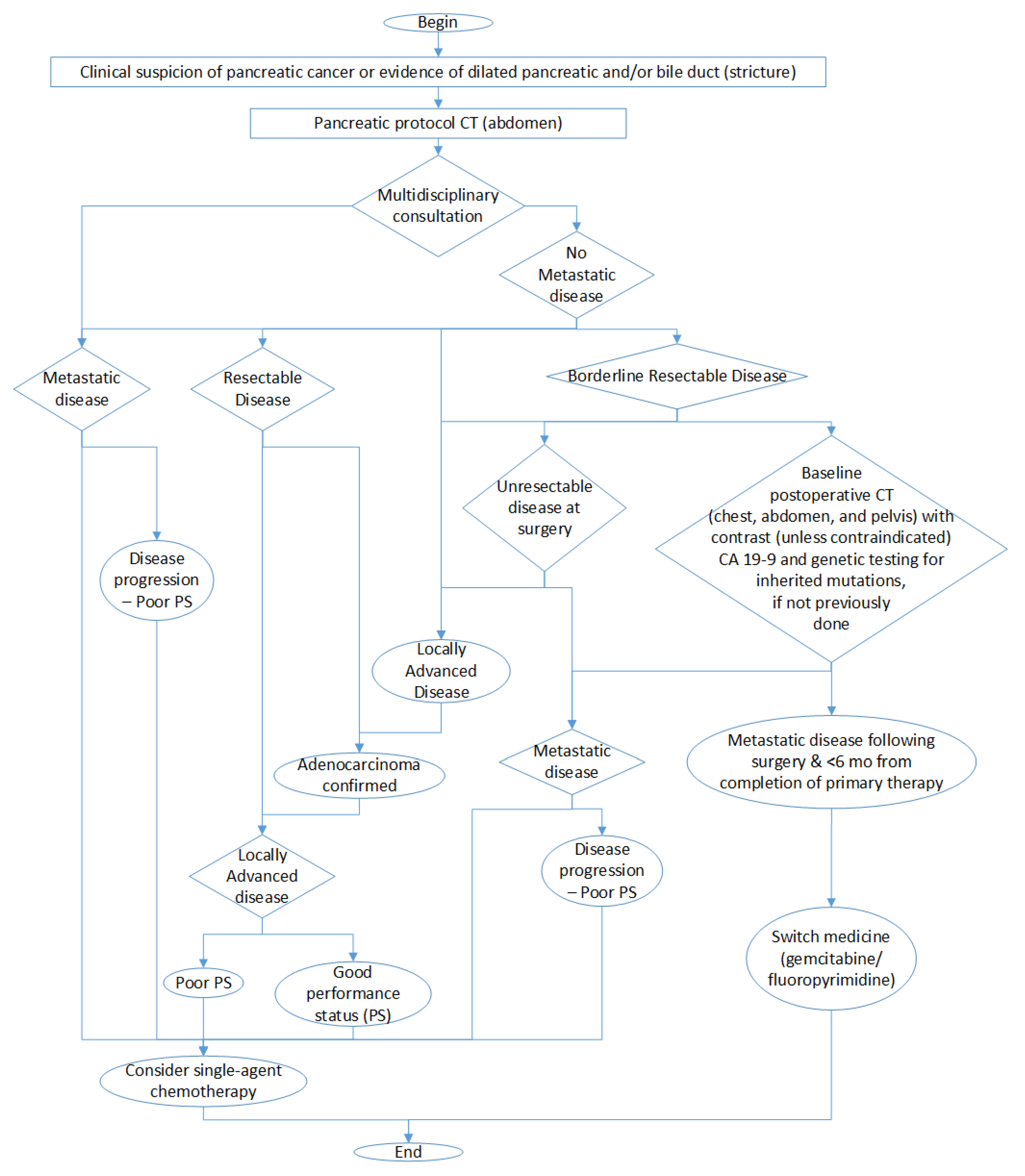

The final result of this analysis is presented in Figure 2 in which we show the decisions that we have to take leading to chemotherapy treatment. It is important to remark that this figure is a simplification to highlight the fundamental decisions and considerations involved in chemotherapy treatment and that the complete diagnostic process is more complex.

Figure 2.

Simplified graph of diagnostic decisions involving chemotherapy treatment.

Each of the nodes represent an evaluation that we have roughly mapped onto a feature value, so that we can follow the diagnosis path. We could use the staging M as an evaluation of metastatic disease, the size of the tumor T to determine whether it is resectable or not, and the N to evaluate if the cancer is locally advanced or not.

In Table 4, we can see the maximum set of features ranked by the medical experts, as commented before, but also ranked using the information extracted from the medical guidelines.

Table 4.

Feature importance from the expert criteria and medical guidelines.

3.3. Machine Learning Models

With the aim of comparing different models in terms of accuracy and understandability, we chose three types of ML models: a Decision Tree, a Random Forest, and an XGBoost. All of them are tree-based algorithms that are known to be easily understandable, but as they increase in complexity, they need to be enhanced with ad hoc explainability methods to be able to interpret their results. They are also the best models for dealing with tabular data of increasing difficulty. We do include a brief description of all of them, highlighting the advantages and disadvantages in terms of accuracy and understandability.

As a general rule, when efficiency improvement is needed, aggregation techniques as bagging or bootstrapping are applied.

- Bagging, also referred to as bootstrap aggregation, is an ensemble learning method that is frequently employed to minimize variability within a noisy data set by integrating the predictions of multiple models through the implementation of diverse aggregation techniques.

- Bootstrapping is a technique that is employed to enhance the performance of a classifier through iterative refinement. In conventional machine learning methodologies, a multitude of classifiers are typically trained on disparate sets of input data. Subsequently, the outputs of these classifiers are integrated to formulate a composite prediction.

These methods are based on tree ensembles, which combine different single trees to obtain an aggregated prediction. Although the results are usually more efficient and mitigate overfitting, the interpretation of these models is far more complex.

3.3.1. Decision Trees

A Decision Tree (DT) is a hierarchical tree structure consisting of a root node, branches, internal nodes, and leaf nodes. It is a non-parametric supervised learning algorithm that can be used for both classification and regression tasks [56].

DTs offer advantages over other AI models as they are easy to interpret. They do not require advance knowledge of AI to understand how they are built, as they are a common structure used in many other fields. They allow a graphical representation of the algorithm, which makes them a perfect candidate in scenarios where understandability is key. Another significant advantage in these models is that they require a minimum set of data and the features are directly included in the model. The calculations required to get a decision are also simple and easy to understand. They can handle both numerical and categorical data, and inherently perform feature selection.

Nevertheless, they can produce overfitting, not generalizing competently when fed with new data. They are also sensitive to small changes in the input data, so small variations can generate very different trees. And finally, they are not good at discovering complex relationships between features.

To overcome these issues, simple models can be combined to get an aggregated model. However, and as usual, increasing the complexity of the model makes it harder to understand. Therefore, to be able to explain the decisions performed by the model, and infer which are the most relevant features taken into consideration, a complementary method is required.

3.3.2. Random Forests

Random Forests (RFs) are the result of combining a set of DTs forming ensembles. Each DT output is combined to reach a single result [7]. It operates through the construction of numerous Decision Trees during the training phase, subsequently determining the predominant category of each individual tree.

The main advantages of the RFs include high accuracy, robustness to overfitting, and the capacity to handle large data sets. In terms of understandability, they provide a way to measure the feature importance. Another great advantage is that RFs do not make assumptions about the distribution of the data and are able to capture complex relationships between features and the target variable. They scale in both number of features or observations, and their computation could be parallelized to get faster training times.

In simple scenarios, due to the complexity of the structure, it requires more computation than single trees, and its interpretability decreases. Even though the algorithm required to compute predictions can be parallelized, they are computationally intensive and consume more memory than individual Decision Trees.

3.3.3. XGBoost

XGBoost stands for “eXtreme Gradient Boosting”, and it is built combining many simple models to create an ensemble with higher prediction capabilities [57]. The model is composed of a sequence of weak learners (typically Decision Trees) successively, with each subsequent model attempting to rectify the errors made by the preceding ones. It employs a gradient-based optimization algorithm to construct the trees, with the objective of minimizing a user-defined loss function.

XGBoost is one of the most efficient models in terms of accuracy, and it can be applied over data sets where both categorical and numeric features are included. It often outperforms RF in terms of predictive accuracy, especially when dealing with structured/tabular data. While RF has some mechanism to mitigate overfitting, XGBoost incorporates regularization, which provides better control.

On the other hand, the interpretability of the resulting models is far more complicated than a single tree and it requires specific knowledge to be able to tune its parameters. While both XGBoost and RF are ensemble models, RF models are often considered more interpretable than XGBoost due to their simpler structure.

3.4. Explainability Models

Explainability models or techniques are used to enhance the interpretability and understanding of ML models. In particular, in this work, we focused on using Feature Importance [58] as an explainability method. Feature importance is a term used to describe a class of techniques for assigning scores to input features of a predictive model. These techniques indicate the relative importance of each feature when making a prediction.

We have included two model-specific explainability methods for tree-based models and two model-agnostic explainability methods, which we will briefly explain in the next sections.

3.4.1. Model-Specific Methods

Feature importance scores for tree-based models can be divided into two categories [59]:

- Split-improvement scores that are specific to tree-based methods. These scores naturally aggregate the improvement associated with each node split. They can be readily recorded during the tree-building process.

- Permutation methods that involves quantifying the alteration in value or precision when the values of one feature are substituted with irrelevant noise, typically produced by a permutation.

Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI)

Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI) is a split-improvement score that measures the inherent importance of different measures [7]. The extent to which each feature contributes to reducing the uncertainty in the target variable is a critical factor in this determination. MDI is measured by the extent of reduction in Gini impurity or entropy that is achieved by splitting on a particular feature.

Mean Decrease Accuracy (MDA)

Mean Decrease Accuracy (MDA) (also known as “Permutation Importance”) [7] measures how the accuracy score decreases when a feature is not available. It randomly discards each feature and computes the change in the performance of the model and orders them based on their impact.

3.4.2. Model-Agnostic Methods

Among the agnostic methods of explainability, we have selected SHAP and LIME.

SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP)

Presented by Lundberg and Lee [60], SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) is a framework for interpreting predictions. It is a model-agnostic method that assigns each feature an importance value for a particular prediction. Its origins are related to the cooperative game theory where players collaborate together to obtain a certain score. In the AI scenario, the players are the features and the score is the prediction.

At a general level, SHAP gives us the insights about the weight of each of the features involved in the classification process. The SHAP framework allows for a practical visualization of the feature contribution using an “importance” diagram.

We are then interested in the contribution of each of the features to the final decision, which is calculated by the SHAP value.

Locally Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME)

Proposed by Ribeiro et al. [61], LIME (Locally Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) tries to understand the features that influence a prediction in a single instance. It focuses on a local level where a linear model is enough to explain the model behavior. LIME creates a surrogate model around the example for which we try to understand the prediction made.

Its scope is inherently local; therefore, in order to compare the results of LIME at a global level, it is necessary to iterate over all the examples and gather the most frequent features in terms of importance.

4. Results

In this section, we will present the results of the different ML models in terms of accuracy and interpretability given the three feature sets discussed in Section 3.2 and compare them with the medical guidelines and the medical criteria used as reference.

4.1. Accuracy of the Resulting Models

As the basis for the evaluation of accuracy of the different models included in this experiment, we have used the following metrics:

- Accuracy indicates the frequency with which a classification machine learning (ML) model is accurate in its overall predictions.

- Precision indicates the frequency with which an ML model accurately predicts the target class.

- Recall indicates the capacity of an ML model to identify all objects of the target class.

- F1-score provides an equilibrium between precision and recall, thereby rendering it a more comprehensive metric for evaluating classification models.

In our specific scenario with a data set unbalanced to chemotherapy cases, the F1-score provides a more robust metric. The model parameters (e.g., max depth, min samples per leaf, etc.) have been established by selecting the optimal configuration in every case. Each model was evaluated using different configurations, and we only kept the one with the highest accuracy. Here is a description of the different hyperparameter settings:

- Maximum Depth (md): This parameter defines the maximum number of levels allowed in a tree. It controls the complexity of the model by limiting how many times the data can be split. For Decision Trees, a lower depth (e.g., md = 2 or 3) was used to keep the models transparent and easy to interpret. For Random Forests and XGBoost, the depth was varied between 2 and 4 to find a balance between capturing complex relationships and avoiding overfitting.

- Minimum Samples per Leaf (msl): This parameter sets the minimum number of data points (samples) that must exist in a leaf node (a terminal node at the end of a branch) for a split to be valid. It acts as a regularization tool to prevent the tree from creating branches that account for only a few specific, possibly outlier, cases. In Decision Trees, this was set as high as 30 for the “Recommended” set to simplify the tree structure. In Random Forests, it was consistently set to 5 to maintain a level of detail across the ensemble.

- Number of Estimators (ne): This parameter is specific to ensemble models like XGBoost. It specifies the number of individual trees (weak learners) to be built and combined in the final model. The XGBoost models used either 40 or 50 estimators depending on the feature set being tested. Generally, more estimators can improve model accuracy by allowing the system to correct more errors from previous trees. However, after a certain point, adding more trees provides diminishing returns and increases computational cost and the risk of overfitting. The value has been chosen between 40 and 50 because a low value is most appropriate for small data sets such as ours.

Results can be seen in Table 5. The criterion for the tree node evaluation for both the DT and RF was the Gini index. The XGBoost objective was set to binary logistic.

Table 5.

Accuracy results for three ML models using three different feature sets.

From Table 5, we can state that the best models in terms of accuracy have been those built with the minimum set of features. This circumstance suggests that adding additional information to a data set does not always result in better accuracy, and moreover, it could make the models more complex.

Referring to the types of models, DTs are more accurate in general, but their results are very close to those produced by XGBoost. The assumption we had when using an advanced type of model, such as XGBoost, was that the increased complexity would translate into improved performance. The failure to obtain any gain in accuracy could be explained by the small size of the training set, as it is known that, typically, ML algorithms require a great amount of data to produce acceptable results. However, there exist approaches to mitigate this, as will be explained in Section 5.

4.2. Interpretability of the Resulting Models

Presenting interpretability information is a bit complex, since there is no defined measure of how correct the interpretation of an ML model is. We intend to move in this direction by comparing the interpretability of the models with the medical criteria of the field expressed through guidelines and the opinions of the physicians. In the following sections, we will discuss how to analyze the importance of the different features according to the different explainability methods used for the different feature sets.

4.2.1. Extracting Feature Importance from XAI Methods

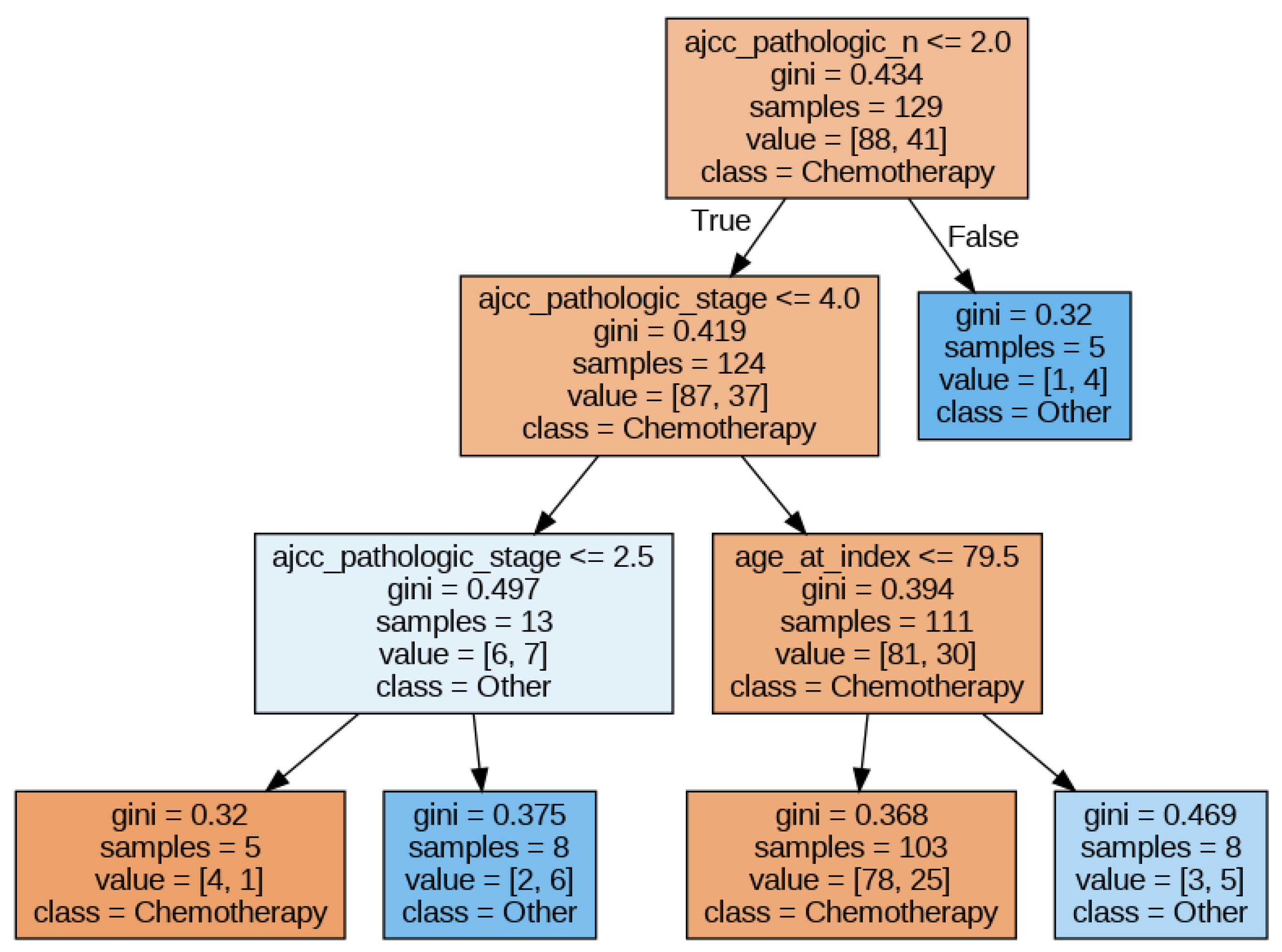

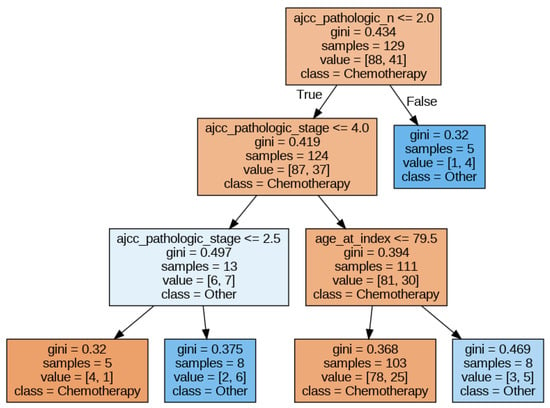

In this section, we will illustrate how to extract the feature importance that the XAI methods assign to the different features given to an ML model. To this end, we chose a DT model (since it is transparent regarding interpretability) trained with the minimum set of features (to make the figures more readable). The DT hyperparameters that obtain the best accuracy are a maximum depth of the tree of 3, the minimum samples per leaf set to 5, and Gini as the split criterion. The best accuracy obtained was approximately 0.66.

Figure 3 shows the DT obtained. In this figure, we can observe that pathologic N, pathologic stage, and age are the most relevant features. In the following sections, we will apply different explainability methods and extract the feature importance delivered by them.

Figure 3.

Decision Tree for the ‘minimum’ set of features.

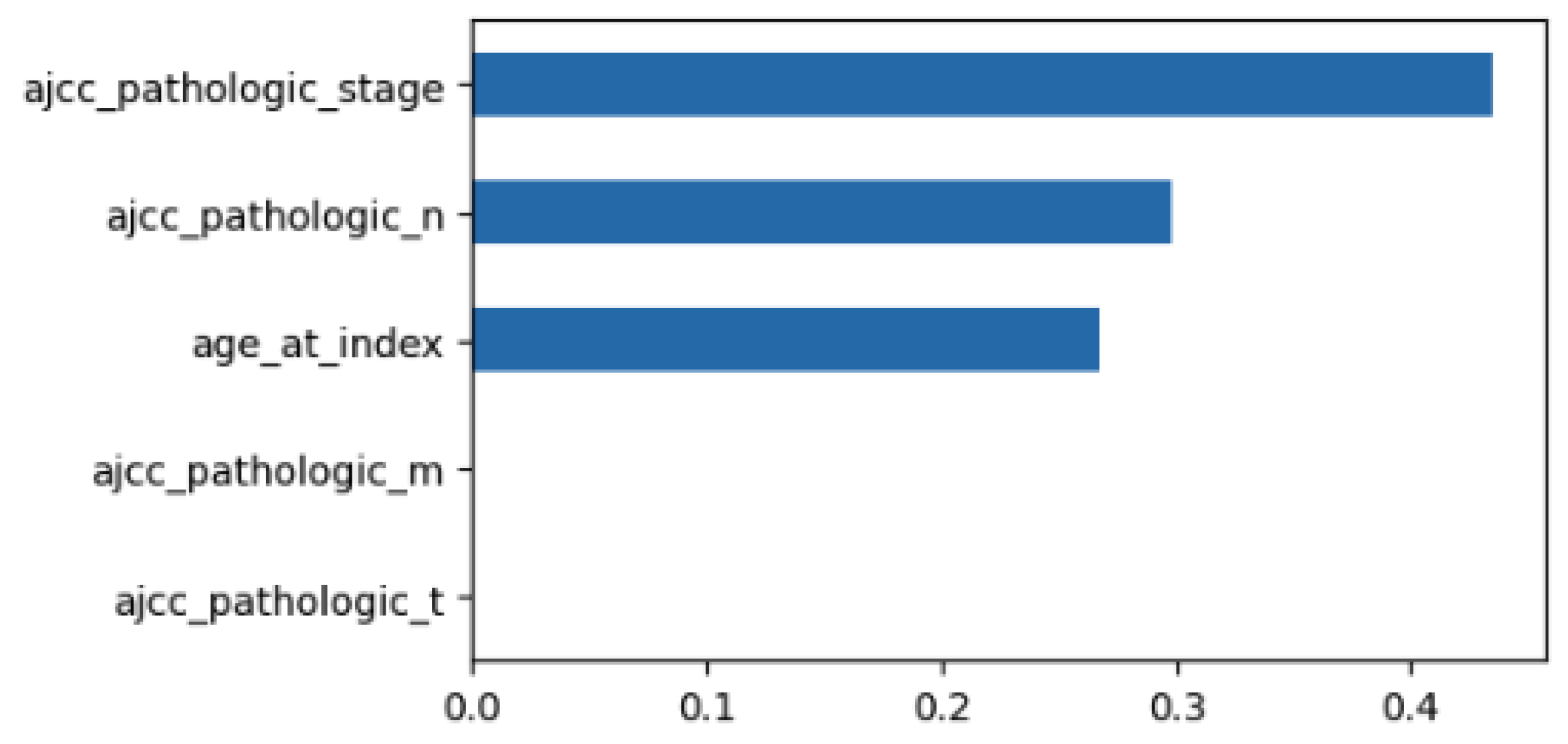

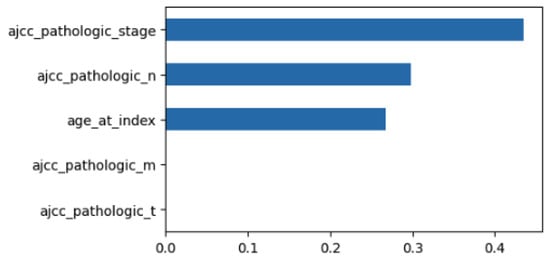

Using MDI to examine the feature importance of the classifier with the minimum feature set, we obtain the results of Figure 4. The size of each bar is related to the relevance of the feature. So, in this case, stage is the most relevant feature followed by pathologic N and age.

Figure 4.

MDI for the DT with the ‘minimum’ set of features.

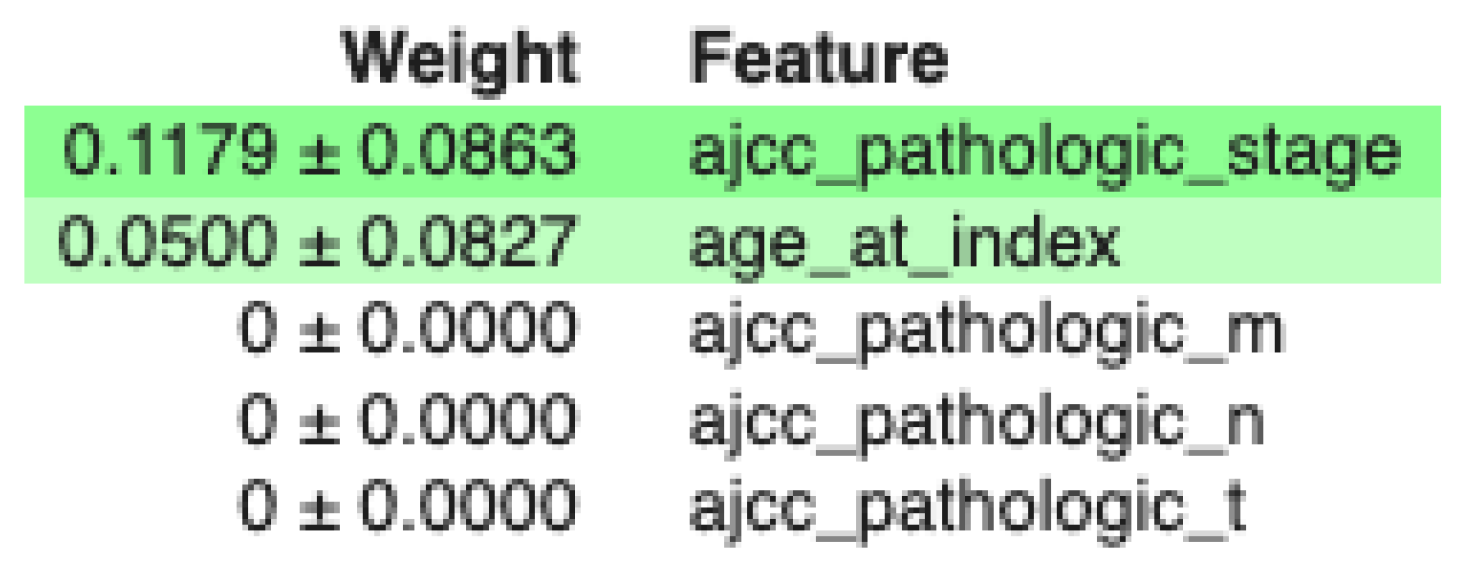

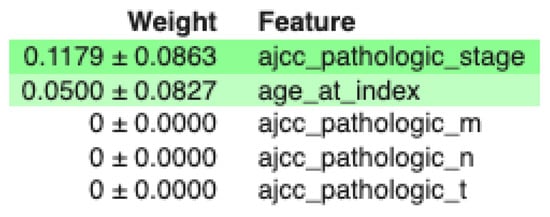

On the other hand, using MDA to examine the feature importance of the classifier using the minimum feature set, we obtain the results of Figure 5. Here, relevant features are highlighted. In this case, stage is the most relevant feature followed by age.

Figure 5.

MDA for the DT with the minimum set of features.

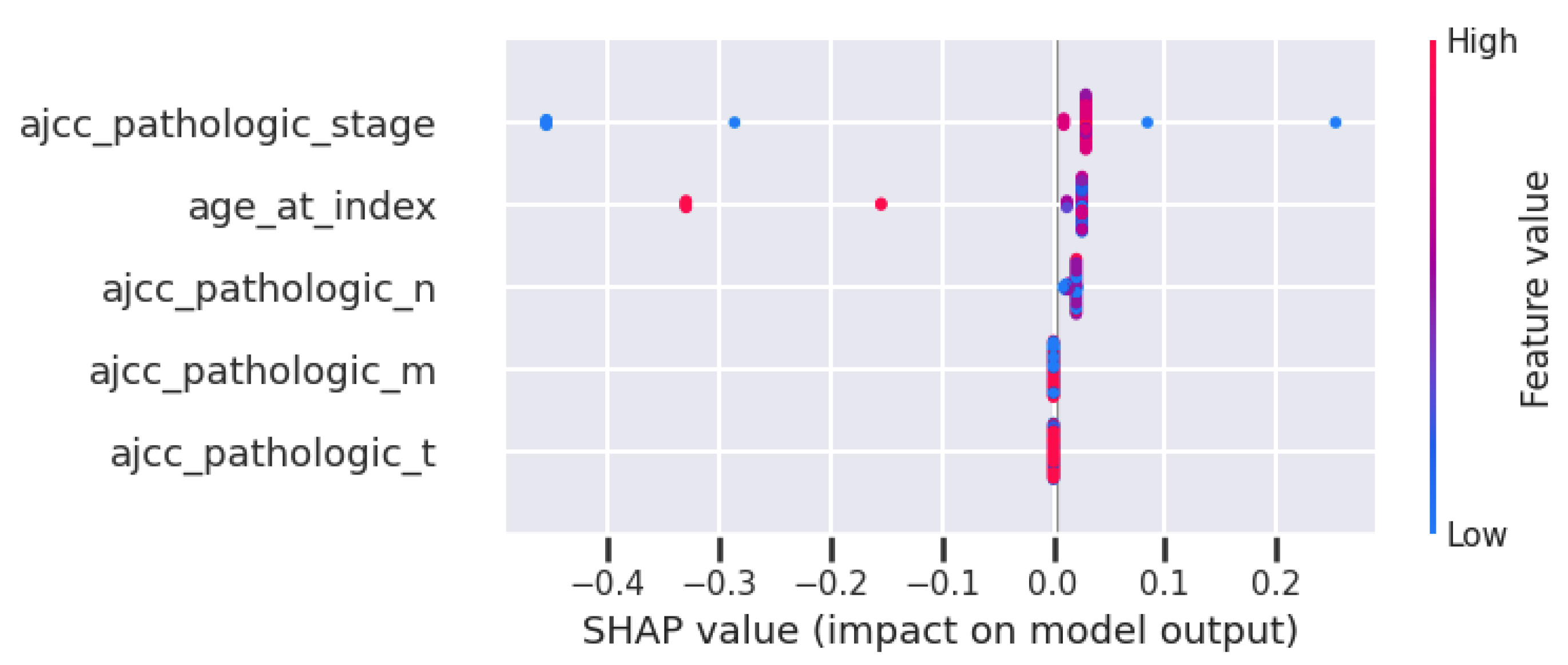

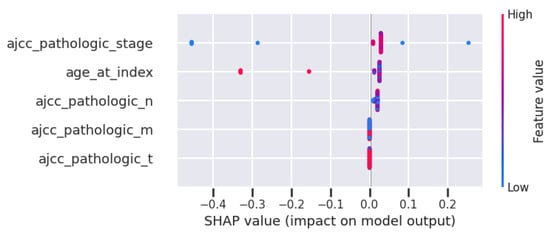

Taking into account the model-agnostic method SHAP, Figure 6 presents the feature importance of the classifier using the minimum feature set. This figure is the summary chart of SHAP, which presents the features in order of relevance on the left axis. In this case, stage, age, and pathologic N are the most important ones.

Figure 6.

SHAP for the DT with the ‘minimum’ set of features.

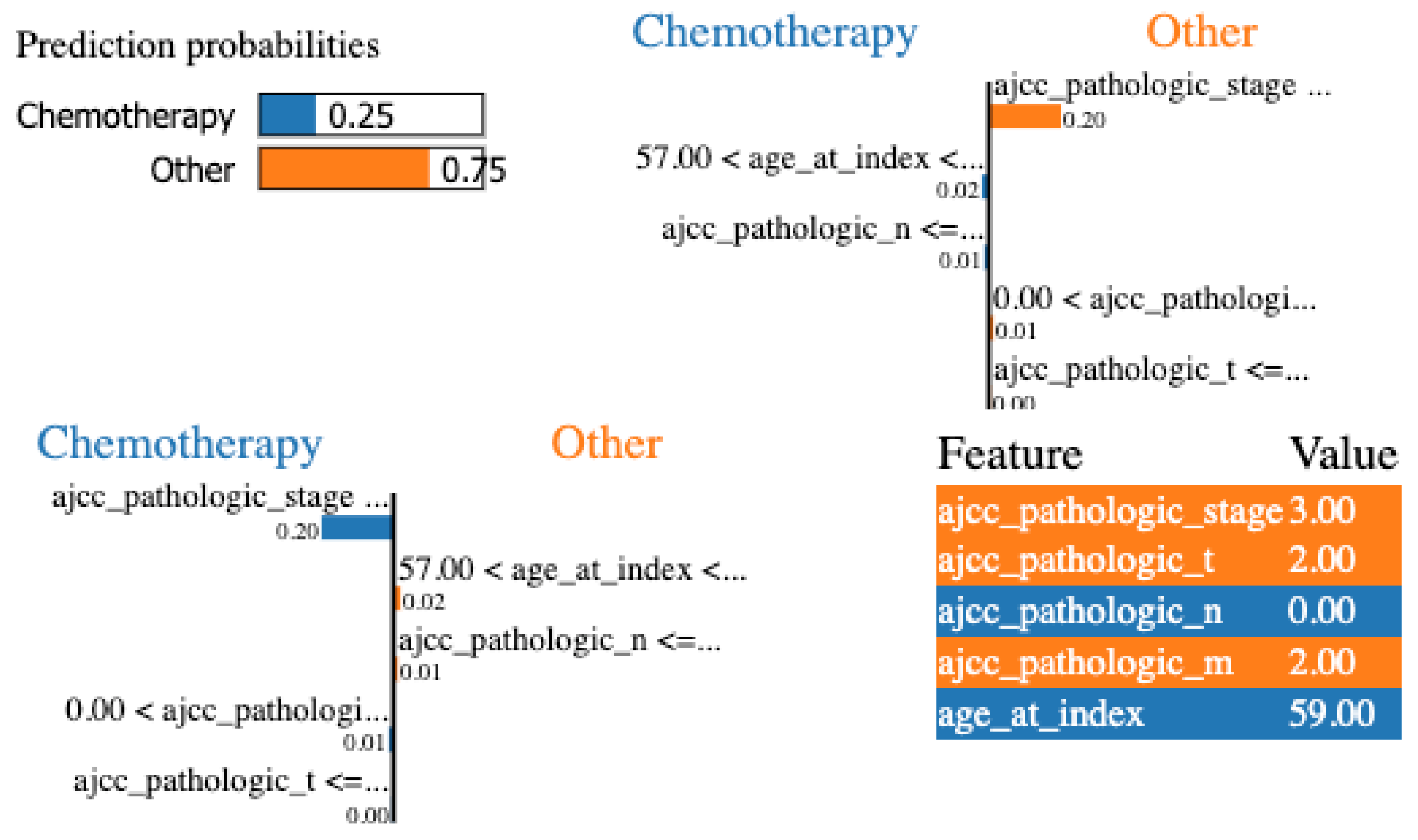

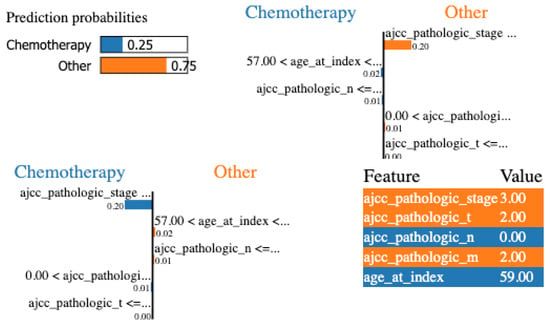

Finally, LIME was applied to the same configuration. In Figure 7, we show the local explanation of a particular patient that indicates stage, pathologic T, and pathologic N as the most important features. Nevertheless, to be able to evaluate and compare LIME results at a global level, we iterate over all the local explanations and keep the most frequent features for all the examples. Stage, pathologic N, and age are the most relevant features at a global level.

Figure 7.

LIME for the DT with the minimum set of features for a specific patient.

For LIME, we configured the following hyperparameters:

- num_features = 10. Balances sparsity; low levels ensure that the explanation is simple and remains interpretable for humans.

- discretize_continuous = True. Recommended for tabular data; it makes the results much easier to read as simple if–then rules.

- top_labels = 5. Chooses which labels or classes to explain; in this case, the highest-scored labels.

- kernel_width = 0.75 (default for tabular). Smaller values are recommended for very local behavior (more unstable); larger values for more global behavior (smoother results).

- n_permutations = 5000 (default). Should be increased whenever explanations vary significantly between runs.

All these results for the DT classifier using the minimum feature set are summarized in Table 6 assigning a “1” to the highly relevant features, “2” for relevant features, and “3” for the less relevant features, and leaving blank values if the feature is not relevant to the XAI method. We also include, for comparison, the relevance of the features using the medical guidelines and the medical expert criteria.

Table 6.

Feature importance for the ‘minimum’ set of features.

4.2.2. Jaccard Similarity Index

Similarity Index

We need a metric that allows us to compare the results obtained. One good candidate is the Jaccard Similarity index [62] that measures the similarity between two sets dividing the size of the intersection by the size of the union of the two sets. Mathematically, given two finite sets S and T from a universe U, the Jaccard Similarity of S and T is defined as

In our case, the elements of the set are the different features and the importance that the different models of explainability give to these features. In addition, we not only want to see if the elements of the different sets coincide, we also want to see if they coincide in order, giving more importance to the coincidences in the first positions. For that reason, the Weighted Jaccard Similarity index [62] is more convenient, since it allows us to handle cases where elements in the data have different weights or importance.

The Weighted Jaccard Similarity index assumes that a weighted set exists that associates a real weight to each element in it (being this weight ). Therefore, a weighted set is defined by a map . In our case, since we want to give more importance to the first position matches, we assign a weight of 3 to the first position, 2 to the second position, 1 to the third position, and 0 to the non-ranked elements.

Thus, given two vectors of weights and with all real , their Weighted Jaccard Similarity coefficient is defined as

Other similarity measures we could have used are measures that come from statistics, such as Rank Correlation Coefficients (Spearman and Kendall), which are the “standard” statistical metrics for comparing two ranked lists. Spearman’s Rho () [63] measures the Pearson correlation between the rank values. It tells us if the “direction” of importance is the same across models. Kendall’s Tau () [64] measures the number of “concordant” and “discordant” pairs. It is often considered more robust than Spearman for small sample sizes or when there are many ties in the data. However, these metrics treat all positions equally; a disagreement at rank 1 (the most critical feature) is penalized the same as a disagreement at rank 50.

From the information retrieval domain and the recommendation systems, we can find metrics such as Rank Biased Overlap (RBO) [65], a similarity measure designed to compare ranked lists, particularly when the lists may have different lengths, incomplete rankings, or non-conjoint elements. Unlike traditional metrics like Kendall Tau, RBO is weighted, giving more importance to higher-ranked items, making it especially useful in search engines, recommendation systems, and ranking problems. Also, we have Mean Average Precision (MAP) [66], and some XAI frameworks use MAP to compare model explanations to human rationales.

While rank-based metrics like RBO or MAP are common in recommendation systems, we chose Weighted Jaccard Similarity because medical guidelines often define “sets” of relevant clinical factors rather than strict linear rankings. Jaccard provides a more robust and intuitive measure of “clinical alignment” by penalizing the inclusion of irrelevant features while rewarding the identification of the consensus-based feature set.

In summary, we have chosen the Jaccard measure because

- The “Gold Standard” is often a set, not a ranking. In information retrieval, there is a clear difference between the 1st and 10th result. However, in medical guidelines (like NCCN), clinical variables are often presented as a category of importance rather than a strict linear list.

- Handling “Zero-Importance” Features. Medical data often has many features that should have zero importance (noise). Recommendation metrics (RBO and MAP) are designed to measure how well you rank relevant items. They do not have a natural way of handling the “negative space”, that is, the features that should be ignored. Jaccard naturally penalizes “false positives” (when the model gives high importance to a variable the doctor knows is irrelevant). This is crucial for medical safety to ensure the model is not hallucinating importance.

- Complexity vs. Interpretability. Our goal is to make AI results “interpretable” for clinicians. In that sense, Jaccard is highly intuitive: “What percentage of the features we care about did the AI actually pick up?”. By using the weighted version, we keep the simplicity of the Jaccard logic but allow the specific importance values to influence the score, without needing the complex “convergence parameters” required by RBO.

- Robustness to Small Perturbations. Recent studies in XAI stability show that rank-based metrics (like Kendall’s Tau) can be hyper-sensitive to tiny changes in feature weights that do not actually change the clinical meaning of the explanation. Jaccard is more stable because it looks at the “overlap” of significant features rather than the “order” of every single minor feature.

4.2.3. Feature Importance Using the Minimum Feature Set

In Table 7 and Table 8, we can see the results of calculating the weighted Jaccard index for the DT and XGB models, respectively, according to the data included in Table 6. We decided to focus our analysis on the two models that offer the best performance.

Table 7.

Similarity measures for the different XAI methods using the DT model and the “minimum” set of features.

Table 8.

Similarity measures for the different XAI methods using the XGB model and the “minimum” set of features.

From these tables, we can see several things: first, that the degree of similarity between the guides and the experts is high (0.75), and the same occurs between the different methods of explainability. We see that the main similarity is that they all agree in assigning the stage as the most important feature, while the main difference is that the ML models give less importance to features such as T and M.

4.2.4. Feature Importance Using the Recommended Feature Set

In this section, we will present the interpretability results for each ML model and each feature relevance method using the recommended features set. The results are summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Feature importance for the ‘recommended’ set of features.

In Table 10 and Table 11, we can see the similarity results for the DT and XGB models, respectively, according to the data included in Table 9. From these two tables, we can see that again there is a high similarity between experts and guides, and that the similarity between the XAI methods is quite consistent.

Table 10.

Similarity measures for the different XAI methods using the DT model and the “recommended” set of features.

Table 11.

Similarity measures for the different XAI methods using the XGB model and the “recommended” set of features.

If we focus on the DT data, we can see that the Decision Trees take into consideration fewer features than the experts and the guides, which is normal since they only consider those that are necessary to establish a decision. This results in low similarity values with guidelines and experts. On the other hand, the XGB model spreads the importance along the different measures; therefore, the similarity values with experts and guides are higher.

We see that the features chosen as the important ones by the DT model and according to the XAI methods are Age, Stage, Year of initial diagnosis, Neoplasm cancer status, and Residual tumor. Except for Age and Year, the rest are considered very or fairly important by experts and guides. On the other hand, XGB again considers features such as Age, Stage, Residual tumor, or Neoplasm cancer status. But the biggest difference is that it considers features that are completely irrelevant for the DTs but relevant for experts and guides such as histological type or initial diagnosis method.

4.2.5. Feature Importance Using the Maximum Feature Set

In this section, the interpretability results for each ML model and each feature relevance method using the maximum features set are presented. Table 12 summarizes the results.

Table 12.

Feature importance for the ‘maximum’ set of features.

In Table 13 and Table 14, we can see the similarity results for the DT and XGB models, respectively, according to the data included in Table 12. As the number of features increases, similarity values decrease, which is to some extent normal since the ambiguity inherent in assigning concrete values of importance to the different measures must be taken into account.

Table 13.

Similarity measures for the different XAI methods using the DT model and the “maximum” set of features.

Table 14.

Similarity measures for the different XAI methods using the XGB model and the “maximum” set of features.

From these tables, we can see that in DT, the results of the XAI methods are quite consistent with each other, highlighting few features, but they are almost always the same (Age, Stage, Year, Family history). XGB takes into account the influence of more features but the explanatory methods are not as consistent with each other, indicating that it is a more opaque model from which it is more difficult to find consistent explanatory measures.

5. Discussion

5.1. Performance

Regarding the performance of the different ML models, as described throughout the Section 4, the accuracy obtained is low; all of them present similar accuracy values near but not reaching 0.7. On this point, it is important to note that this study did not aim to develop a decision support system in the medical field. This is because we were aware that we were working with a data set containing few cases and that obtaining generalization capabilities with this data that would lead to high accuracy values was not considered a realistic goal. This is a clear data bottleneck problem and, as discussed in [51], a possible solution is to use data augmentation strategies to improve data quality and quantity. In that work, the accuracy increased more than 10 percent with the collaboration of human experts who helped to improve the labeling and the generation of synthetic cases. The objective of this study was to verify the feasibility and effectiveness of similarity measures when analyzing the quality of explainability measures using medical guidelines and human experts as a reference. We use these measures not only to evaluate the explanatory capabilities of ML models but also to analyze the consistency between different XAI methods. Adding synthetic data could improve accuracy but at the cost of introducing correlations that might not be real and could affect explanatory capabilities.

Comparing the different ML models, we can see that DT and XGBoost models deliver similar results in terms of accuracy in all scenarios. The fact of increasing or decreasing the set of features did not make the RF model nor the XGBoost model better in terms of performance. It could be due to the small number of examples used to train the model. Normally, they are expected to find complex relationships between the different features, but in our work, it was not the case. Although all ML models are tree-based and bagging and boosting techniques are included in the RF and XGBoost models, respectively, we have found no gain in terms of accuracy nor in explicability matters.

Regarding the different feature sets used, it is interesting to highlight that the minimum feature set was the one that obtained better results in terms of accuracy. One possible explanation could be the type of features included in this set. Apart from age, features like pathologic T (code to define the size or contiguous extension of the primary tumor), pathologic N (code to represent the stage of cancer based on the nodes present), pathologic M (code to represent the defined absence or presence of distant spread or metastases to locations via vascular channels or lymphatics beyond the regional lymph nodes), and stage (code to represent the extent of a cancer, especially whether the disease has spread from the original site to other parts of the body) are summarizing codes of the cancer status. Therefore, they are a sort of dimensionality-reduction technique applied by physicians to better understand and communicate cancer status. In these features, much of the information needed to decide whether to give chemotherapy treatment is included, although, obviously, the detailed treatment itself requires more information. The remaining sets of features offer lower results but are very close to the results of the minimum feature set.

5.2. Human-in-the-Loop

The participation of humans in the process of developing ML systems (also known as Human-in-the-Loop or HITL) could help in enhancing transparency, improving trust, and achieving better performance [67]. Nowadays, there exist many tools supporting the inclusion of human experts both as ML practitioners or as domain experts [68].

Regarding feature engineering (FE), we have seen that it is an important part of every ML project. There have been other works that focus on the HITL feature engineering process. For example, Anderson et al. [69] propose an interactive HITL FE scheme, based on state-of-the-art dimensionality reduction for nowcasting features for economic and social science models; and Gkorou et al. [70] propose an interactive FE scheme based on dimensionality reduction for Integrated Circuit (IC) manufacturing. Both cases show that by engineering features, it is possible to obtain higher predictive capabilities and to improve the interpretability of the model.

In our case, we collaborated with medical experts for (1) selecting the best features available from the specialized data set and (2) establishing a relevance value creating a recommended set of features and giving insights about the pancreatic cancer diagnosis. This collaboration required the active participation of human experts, something that adds complexity to the process.

But we also used medical expertise through medical guidelines that are standard procedures in the field. This process of analyzing medical guidelines does not require the active participation of human experts but also has its complexities as these guidelines tend to be exhaustive and sometimes hard to navigate through.

This collaboration with human experts in the domain and the analysis of guidelines available in the same domain can be used not only as a feature engineering process but also as a way to evaluate explainability methods.

5.3. Explainability

When it comes to explainability, it is important to notice that each available approach measures specific responses of the model using different techniques, and thus, they could produce different results. However, in this work, we have been able to see that, as a general rule, the explanatory methods, given a specific ML model, provide fairly consistent results among themselves, with high levels of similarity.

We can see that methods such as MDI and SHAP use very different procedures to reach their conclusions, but they are very similar in terms of feature importance. Also SHAP provides several charts that allow us to better understand the explainability results and it also has the advantage of being model-agnostic so that we can compare the results over different ML models.

In any case, we should not expect these tools on their own to produce human understanding of the models. Normally, they require a thoughtful interpretation to understand the underlying decision making process. Furthermore, explainability of black-box models has been criticized because the explanations either do not provide enough detail to understand what the black box is doing or they do not make sense [71].

To try to facilitate the interpretation of these explanatory results, we use a similarity measure such as the Weighted Jaccard Similarity coefficient. From their results, we can see several things: First, models like DT are more “decisive” when it comes to giving importance to features; for this ML model, only a few features are important for the final result. On the other hand, and due to the very nature of the model, XGB distributes this importance more evenly among the different features. This has an effect on our results; as guides and experts also distribute the importance among the different features, the similarity index of XGB with experts and guides is usually higher than that of DT.

We could say then that this behavior of XGB is more “human”, since it tries to take more information into account when making a decision. Although, in this case, taking into account more features does not correspond to a better performance, this may be due to problems inherent to the data set itself and its low number of cases. Thus, for example, we see that the DT model eliminates from its consideration features such as histological type or initial diagnosis which are taken into account by experts and guides. A model such as XGB does take them into account.

Regarding the importance given by the experts and the guides to the different features, we can see that the similarity index between them is always high, with some variations that are easy to explain by the subjectivity of the assignment of values.

Regarding how the models assign importance to the features in comparison with guidelines and experts, in general, we can say that the features pointed out as relevant by physicians and guidelines have been taken into account by the models, with some notable exceptions. Thus, for example, staging M has been generally forgotten by ML models when physicians assigned it a high importance. On the other hand, we have also observed that some features with low relevance for the experts are considered by the XAI methods, such as, for example, Age.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, we can highlight that, in this last “spring” of AI, researchers have decided to leave symbolic AI aside because its results were not entirely good, and these AI models were very difficult to scale to larger problems. However, by embracing ML and subsymbolic AI, we are getting better results, but these results have a worse interpretability because they have lost that symbolic character.

By trying to analyze ML results and compare their explainability through information from domain experts and guides, what we are trying to do is to give “symbolism” to these results, to try to understand them from a human point of view. This approach is not problem-free; it requires active collaboration on the part of physicians, and medical guidelines are complex documents that require time for analysis.

However, we believe that the similarity measures used to analyze the importance of the different features can be an interesting way to evaluate explainability methods. The fact that the best models are the most opaque may cause such models to be discarded in critical domains such as health. Explainability agnostic methods and similarity measures can be used as techniques to better understand how the model works and whether the model adheres to recommended medical practices.

Until now, the feature importance was used as a measure of dimensionality reduction, allowing to simplify the problem being modeled in order to try to speed up the learning process and, in some cases, to improve the performance of the ML model. In our case, what we intend to do is to use the feature importance as a way of evaluating the explainability of the different models.

As future work, we plan to further develop the field of explainability metrics; we believe that in the future, this type of metric will be as common as performance metrics (accuracy and F1-score) are today. The idea is to choose not only the model that offers the best performance but also the model that can best explain its conclusions and whose reasoning is best aligned with human knowledge of the domain. Other aspects to consider are expansion to multi-center data validation, the development of real-time interaction systems, or the standardization of interpretability indicators.

Also, we believe that this work is easily transferable to other decision-making domains that rely on feature importance-based interpretability. However, adjustments would naturally be required for the hyperparameters of both the machine learning models and the explainability techniques to adapt to each specific problem. For instance, we envision that the Jaccard index could be readily applied to fields such as sleep medicine, where an expert can identify specific signal segments deemed important for certain classifications—such as identifying sleep stages—and compare this clinical importance with the relevance assigned by explainability metrics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.B.-B., E.M.-R., Á.F.-L. and D.A.-R.; methodology, J.B.-B., E.M.-R., Á.F.-L. and D.A.-R.; software, J.B.-B. and I.F.-A.; validation, J.B.-B., E.M.-R., Á.F.-L. and D.A.-R.; formal analysis, J.B.-B., E.M.-R., Á.F.-L. and D.A.-R.; investigation, J.B.-B., E.M.-R., Á.F.-L. and D.A.-R.; resources, J.B.-B., Á.F.-L. and Y.V.-Í.; data curation, J.B.-B., I.F.-A., Á.F.-L. and Y.V.-Í.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B.-B., E.M.-R., Á.F.-L. and D.A.-R.; writing—review and editing, J.B.-B., E.M.-R. and D.A.-R.; visualization, J.B.-B., I.F.-A. and Á.F.-L.; supervision, E.M.-R. and D.A.-R.; project administration, E.M.-R.; funding acquisition, E.M.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work has been supported by the State Research Agency of the Spanish Government (Grant PID2019-107194GB-I00/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and Grant PID2023-147422OB-I00) and by the Xunta de Galicia (Grant ED431C 2022/44), supported by the EU European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). We wish to acknowledge support received from the Centro de Investigación de Galicia CITIC, funded by the Xunta de Galicia and ERDF (Grant ED431G 2023/01).

Data Availability Statement

The results published here are in whole or part based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: https://www.cancer.gov/tcga, accessed on 5 January 2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| XAI | Explainable AI |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| HITL | Human-in-the-Loop |

| DT | Decision Tree |

| RF | Random Forest |

| XGBoost | eXtreme Gradient Boosting |

| MDI | Mean Decrease in Impurity |

| MDA | Mean Decrease Accuracy |

| SHAP | SHapley Additive exPlanations |

| LIME | Locally Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations |

References

- Linardatos, P.; Papastefanopoulos, V.; Kotsiantis, S. Explainable AI: A Review of Machine Learning Interpretability Methods. Entropy 2021, 23, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelov, P.P.; Soares, E.A.; Jiang, R.; Arnold, N.I.; Atkinson, P.M. Explainable artificial intelligence: An analytical review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2021, 11, e1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barredo Arrieta, A.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; Garcia, S.; Gil-Lopez, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Inf. Fusion 2020, 58, 82–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montavon, G.; Samek, W.; Müller, K.R. Methods for interpreting and understanding deep neural networks. Digit. Signal Process. 2018, 73, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, D.; Hilgard, A.; Singh, S.; Lakkaraju, H. Reliable Post hoc Explanations: Modeling Uncertainty in Explainability. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 9391–9404. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsiantis, S.B. Decision trees: A recent overview. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2013, 39, 261–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; KDD ’16. pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]