Abstract

The Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (GEPSVM) introduces a novel large-margin classifier that improves upon standard SVMs by constructing a pair of non-parallel hyperplanes derived from a generalized eigenvalue problem. However, the GEPSVM suffers from severe misclassification in the overlapped hyperplane region, known as the underdetermined hyperplane problem (UHP). A localized GEPSVM (LGEPSVM) alleviates this issue by building convex hulls on the hyperplanes for classification, but it still faces notable drawbacks: (1) an inability to integrate both local and global information, (2) a lack of consideration of the data’s statistical characteristics, and (3) high computational and storage costs. To address these limitations, we propose the Ellipsoid-structured Localized GEPSVM (EL-GEPSVM), which extends the GEPSVM by constructing ellipsoid-structured convex hulls under the Mahalanobis metric. This design incorporates statistical data characteristics and enables a classification scheme that simultaneously considers local and global information. Extensive theoretical analyses and experiments demonstrate that the proposed EL-GEPSVM achieves improved effectiveness and efficiency compared with existing methods.

Keywords:

proximal support vector machine; generalized eigenvalues; convex hull; computational geometry MSC:

68T10

1. Introduction

Based on statistical learning and structural risk minimization principles, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) is widely used in various classification problems. By maximizing the margin between two-class samples and meanwhile minimizing experience error, SVMs are capable of achieving better generalization and performance. Due to the high computation burden and low interpretability in complex data, the standard SVM is not suitable for learning in multimedia applications. Inherited from the standard SVMs, the Proximal Support Vector Machine (PSVM) uses two parallel hyperplanes to fit two-class samples instead of a single decision plane for classification [1]. The PSVM provided the brand new idea of constructing large-margin classifiers, which was a breakthrough in the SVM research area. Furthermore, the GEPSVM [2] introduced a generalized eigenvalue problem as its solution, which made possible flexible and efficient implementation in applications. Various derivatives were proposed recently to improve the performance and generalization in view of the GEPSVM and PSVM, for example, GEPSVML1 [3], TWSVM [4], and PCC [5].

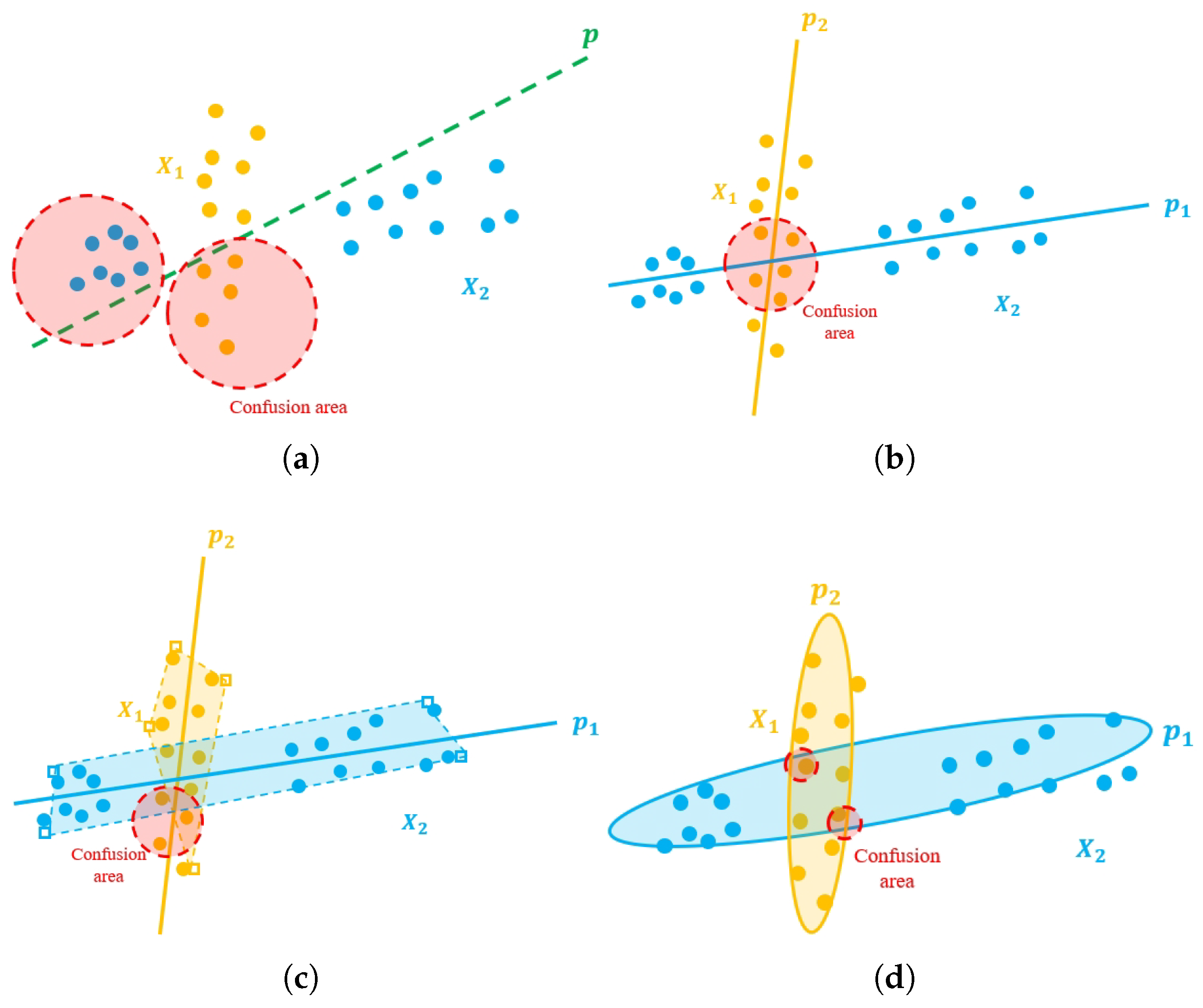

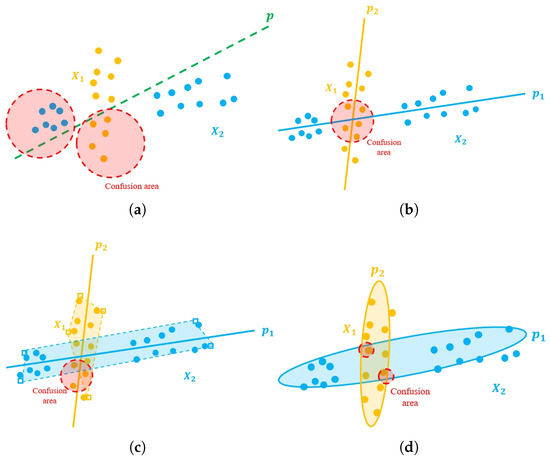

However, a self-contained drawback in the GEPSVM is inevitable, where it may misclassify two overlapped hyperplanes (as shown in Figure 1b). We can call this problem an undetermined hyperplane problem (UHP). Obviously, such misclassifications occur extensively in the intersection region of the two planes in Figure 1b. The LGEPSVM utilizes a convex hull to make classifications to deal with the drawback of the GEPSVM. It assigns samples to classes according to the nearest convex hull, which represents the local region of the decision hyperplane. Several algorithms are proposed that take this localization method and combine it with an SVM and GEPSVM, for instance, the LCTSVM [6,7,8]. However, the LGEPSVM cannot obtain results through batch computation, which takes much more time than the GEPSVM. Since the process of LGEPSVM convex hull construction is iterative and its time complexity is (n, m are the size and dimension of the sample), it is time-consuming when classifying large-scale datasets. In this case, constructing a convex hull differently to make improvements with higher efficiency is necessary. This will enhance the discriminability in the overlapped hyperplanes and meanwhile keep the superiority brought by the GEPSVM with the idea of the large-margin classifier.

Figure 1.

Illustration of SVM [9] (a), GEPSVM [2] (b), LGEPSVM [10] (c), and the proposed E-LGEPSVM (proposed) (d). and represent samples from two categories. The green plane p is the hyperplane of the SVM. (blue) and (yellow) are hyperplanes supported by and , respectively. The red circle is a confusion area where samples are likely to be misclassified.

Localization is an effective methodology to relieve the problems from the original GEPSVM [10]. Compared with the primitive GEPSVM, the localized GEPSVM produces two major advantages for machine training and classification: (1) it relieves the misclassification problem (see Figure 1c) in UHP region, and (2) it is able to be kernelized for classification in nonlinear space. Specifically, the localization is to construct a convex hull based on the hyperplane so that the classification can be performed with a convex set rather than with the whole hyperplane. This makes the decision boundary of a localized GEPSVM sensitive to the samples located in the UHP region of both planes. In other words, this makes the GEPSVM successful when dealing with ambiguous samples which may lead to failure in classification. Although the localization has success in the misclassification problem, it still lacks consideration of the statistical characteristics of data. Also, the construction of data needs to iterate each sample in the training data. Furthermore, samples involved in the convex set require extra storage space for the classification procedure. Both points above make the algorithm less efficient and more expensive when the scale of the dataset increases.

In this paper, we address the abovementioned problems of GEPSVMs: (1) the misclassification in the UHP region, (2) the mis-consideration of both local and global information, and (3) the lack of geometrical interpretation of the classification mechanism with brand new methodologies with theoretical fundamentals. To address these issues, we propose the Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (EL-GEPSVM), which constructs an ellipsoidal convex hull using the Mahalanobis metric for large-margin classification. The ellipsoidal convex hull alleviates the misclassification issue in the UHP region by reducing the area of the UHP region (see Figure 1d). Since the Mahalanobis metric is a typical non-Euclidean metric used frequently in different fields for model optimization, it can take global information into account while remaining scale-invariant [11]. Several research areas and applications support the importance and effectiveness of the Mahalanobis metric [8,12]. Compared with the Euclidean metric, the Mahalanobis metric adaptively incorporates the variance and correlation among features, allowing the classifier to model data distributions as anisotropic ellipsoids rather than isotropic spheres. This enables the EL-GEPSVM to better capture intra-class covariance and local geometry, thereby improving separability and robustness in complex, high-dimensional spaces. To provide a proper geometrical interpretation of the classification mechanism for the EL-GEPSVM, we proved that an ellipsoidal hyperplane can act both as a decision plane and as a convex hull with the Mahalanobis metric [13]. In this case, the proposed EL-GEPSVM can take advantage of the localization philosophy (realized by the ellipsoidal convex hull) to address the misclassification of the UHP in feature space. Also, since the constructed ellipsoidal hyperplane is taken as the decision plane, both local and global information are simultaneously considered. To deal with the classification problem in nonlinear space, we extend the standard EL-GEPSVM to a kernelized version. We theoretically proved that the EL-GEPSVM is able to be kernelized through the proof of the existence of a dual representation of the Mahalanobis norm. In addition, the EL-GEPSVM has higher efficiency than imposing localization directly on a GEPSVM (e.g., localized GEPSVM [10]). A series of EL-GEPSVM algorithms is developed and theoretically justified. The main contributions of this paper could be summarized as the following three aspects:

- Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (EL-GEPSVM). We propose the EL-GEPSVM to provide a solution to the misclassification issue of the UHP region of LGEPSVMs. A series of algorithms is designed for classification.

- Kernelized EL-GEPSVM. We extend the EL-GEPSVM to a nonlinear version with the proof of existence of dual representation of the Mahalanobis norm.

- Geometric interpretation of EL-GEPSVM. We provide the geometric interpretation of the effectiveness of the EL-GEPSVM by theoretically showing that the minimum ellipsoidal convex hull could be achieved with the Mahalanobis metric.

This paper is organized into the following sections: In Section 2, we briefly explain the background knowledge of GEPSVMs. In Section 3, we introduce the newly proposed Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (EL-GEPSVM). In Section 4, several numerical experiments are designed to verify the excellence of the Mahalanobis classifier mentioned in previous sections. In Section 5, the conclusion and future work are described based on experimental results and comparisons. We summarized the list of notations in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of notations.

2. Related Works

2.1. Proximal Support Vector Machines via Generalized Eigenvalues (GEPSVMs)

Given two m-dimensional samples in a binary classification problem, the task of the GEPSVM is to search for two hyperplanes:

where represent the norm vector and threshold of sample matrices A, B, respectively. Taking hyperplane as an example, to minimize the distance to A and maximize the distance to B, the objective function of optimization can be described as follows:

where A and B are the samples from classes 1 and 2, defines the hyperplane of class 1, and e represents the column vector filled with element 1. Equation (2) formulates the learning of the first hyperplane in the GEPSVM framework as a Rayleigh quotient minimization problem. The numerator measures the within-class fitting error for class 1, regularized by the term to avoid overfitting. The denominator expresses the distance from the opposite class 2, thereby enforcing large-margin separation. Minimizing this ratio yields a hyperplane that is close to samples in class 1 while distant from those in class 2. This optimization can be rewritten as a generalized eigenvalue problem:

where , , , and is the regularization factor. Likewise, hyperplane can be obtained as above. It is easy to see that the smallest eigenvalue of Equation (3) depends on the corresponding eigenvector. This derivation follows directly from the Rayleigh quotient principle (see Ref. [2]).

Based on the GEPSVM, the localized GEPSVM [10] focuses on the local region of each hyperplane. In other words, the convex hull of each fitted hyperplane is computed in an LGEPSVM. To avoid conventional quadratic programming problem solving as well as to improve classification speed, a convex hull construction algorithm is proposed in [10]. We denote points projected to the hyperplane from a dataset as , and · denotes the projection sample as shown in Figure 1. and are the two points farthest from each other, and is the norm vector of . Taking as a fixed point, we can find , which represents a projection point in the smallest angle and made through the formulation , in which represents the inner product of the vectors. will act as the next fixed point in place of . Then the process above is repeated until is selected as the fixed point again. All points selected are vertices of a convex set. In terms of [10], a localized GEPSVM is able to be transformed into an unconstrained linear equation problem with a time complexity of . Since convex hull computing is an iterative procedure, the initial condition is critical to the algorithm.

Recent works on GEPSVMs (e.g., GEPSVML1 [3], -LIGEPSVM [14], and LGSVM [15]) extend the GEPSVM along functional data, robustness, or training schemes, but they still operate in Euclidean geometry and/or rely on local heuristics for overlap. The EL-GEPSVM introduces a Mahalanobis-based ellipsoidal convex hull around each class and proves a kernelized M-norm dual, giving a principled way to encode intra-class covariance + local shape while remaining Rayleigh quotient solvable—this directly targets the UHP/overlap in a way prior GEPSVM variants did not formalize.

2.2. Metric Learning

Metric learning [16] is a branch of machine learning that aims to learn an appropriate similarity function from data so that samples from the same class are close together while samples from different classes are far apart. Several studies have explored the integration of Mahalanobis metric learning [17,18,19] with classical classifiers to adaptively shape the feature space. We provide a detailed definition of the Mahalanobis metric in Definition 1 below. For example, Ref. [20] proposes learning a global Mahalanobis distance to enhance the performance of k-nearest neighbor classification. Additionally, DMLCN [21] learns a distance metric to simultaneously preserve the class center structure and the nearest neighbor relationship between data samples. Despite these advances, none of the related works integrates statistical metric learning directly into the geometric localization of the GEPSVM [2]. In contrast, the proposed method embeds the Mahalanobis metric for closed-form ellipsoid hull construction, fusing statistical structure, localization, and margin-based classification in a theoretically grounded but computationally efficient framework.

Recent works use metric learning to optimize ellipsoids (e.g., Ref. [17], CHSMOTE [22]), but they are typically decoupled from the GEPSVM decision rule. Our proposed EL-GEPSVM integrates a Mahalanobis structure inside the GEPSVM objective and derives an M-norm dual that is kernelizable, so the ellipsoid statistics actively shape the proximal hyperplanes, they do not just serve as a pre-processing module.

2.3. Efficiency-Oriented Large-Margin Classifiers

Recent margin-based classifiers focus on improving both computational efficiency and generalization [9]. TWSVM [23] improves training speed by solving two smaller-sized quadratic programming problems. To further scale TWSVMs to large datasets and enhance robustness, Tanveer et al. introduced Large-scale Pinball TWSVM (LPTWSVM) [24], which replaces hinge loss with pinball loss for dealing with noisy and high-dimensional data. More recently, capped L1-norm proximal SVMs [3,25] improve both noise resilience and efficiency by replacing squared L2 norms with capped L1 norms. While these classifiers struggle with efficiency and resilience, they still lack the integration of statistical distribution awareness and geometric localization, which motivates us to propose our EL-GEPSVM.

3. Ellipsoid-Structured Localized GEPSVMs

3.1. Motivation

As we discussed before, a hyper-ellipsoid is a trajectory of fixed radius in the Mahalanobis metric. In a two-dimensional space, it degenerates into an ellipse. Since most samples tend to be distributed on a hyper-ellipsoid after mapping [26], this is one of the reasons why the Mahalanobis-based classifier can achieve better performance. Furthermore, the Mahalanobis distance is adopted in this work because it naturally accounts for both the variance and the correlation among features, thereby providing a statistically adaptive notion of distance. In contrast, the Euclidean metric treats all directions as equally scaled and mutually independent, which can distort class boundaries when the feature space exhibits anisotropy or covariance coupling. We first present the definition of the Mahalanobis metric (termed as the M-norm) in Definition 1:

Definition 1

(M-norm). Let be two distinct m-dimensional vectors from data samples X, and let Σ denote the covariance matrix. Assuming that Σ is a symmetric and positive-definite matrix, the Mahalanobis distance between x and y is defined as

By Definition 1, the Mahalanobis distance can be viewed as a linear re-scaling of the Euclidean distance under the covariance structure . Based on this equivalence, we can formally establish the distance-preserving property of the Mahalanobis metric in Theorem 1:

Theorem 1

(Distance-preserving property). In the same normed linear space, the Euclidean metric and Mahalanobis metric are distance-preserving.

where Σ is the covariance matrix, .

Proof.

As is a symmetric matrix [27], the inverse matrix of is symmetrical.

Therefore,

In this case, the Mahalanobis distance between any two points equals their Euclidean distance after the linear transformation . So the transformation is distance-preserving. □

Since the properties of an ellipsoid are dependent on its radius and centroid, constructing the convex hull construction of our proposed Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (EL-GEPSVM) requires only the mean of the projection points, which further enhances the efficiency. We will present the explanation, theory, and algorithm of the proposed method in detail in Section 3.2 and Section 3.3.

The convex hull is especially utilized in the localized GEPSVM (LGEPSVM), as mentioned in Section 1. The convex hull helps to alleviate the misclassification in the UHP region of the GEPSVM [10]. However, it still suffers from high computational and storage requirements, especially when dealing with larger-scale datasets. Based on the idea of a convex hull, our proposed Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (EL-GEPSVM) improves the localized GEPSVM and further makes it more efficient with less storage requirement. We will introduce it in the next subsection in detail.

3.2. Standard EL-GEPSVMs

We first present Definition 2, which formally defines the proposed Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machines (EL-GEPSVM). Then, we present how to realize the proposed EL-GEPSVM with the idea of a convex hull and the Mahalanobis metric in Theorems 2 and 3. We can define the proposed EL-GEPSVM as follows.

Definition 2

(EL-GEPSVM). Let be the samples in the class and be the samples from the class. The Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (termed EL-GEPSVM) learns the ellipsoidal convex hull and constructed from the GEPSVM hyperplanes to classify from .

In our proposed EL-GEPSVM, we established the concept of an ‘ellipsoidal convex hull’ to refer to a convex region bounded by an ellipsoidal surface constructed under the Mahalanobis metric. Although Ref. [28] formulates geometric ellipsoids with a parametric boundary in TWSVM, our proposed method generalizes the notion of a convex hull to Mahalanobis space. Since the classification rule is made based on the idea of the convex hull, the concept of the ‘ellipsoidal convex hull’ is critical. Compared with circular (or spherical) structures that assume isotropic data distributions, the ellipsoidal form naturally accommodates anisotropy and feature correlations within the sample covariance matrix . In real-world scenarios, class distributions rarely exhibit uniform variance across all dimensions. In this case, an ellipsoidal convex hull offers a more flexible and statistically consistent representation. This allows the proposed EL-GEPSVM to adaptively model the local covariance geometry of each class, improving boundary fitting and class separability. In the standard EL-GEPSVM, we take the maximum distance between the projection point on the hyperplane and the mean point as the radius of the ellipsoid for the ellipsoidal convex hull’s construction. First, we provide Theorem 2 of samples and a convex set:

Theorem 2

(Samples and convex set). Both of the two points in sample set X with the longest distance are included in the convex set as the smallest convex hull that contains all samples in X.

Proof.

Define the projection samples , as the farthest points from each other: . Define H as the convex hull set. Two assumptions are listed below:

Suppose (1) (Equation (8)) is established, then connect , , and extend the line in direction of . Thus, we note the following:

- I

- Ray does not intersect with convex polygon ;

- II

- Ray intersects with convex polygon .

Obviously, the above situation (I) breaks the condition that H is a convex hull set, so it will not be established.

In situation (II), by defining as the intersection of Ray and , as the points from H which are closest to , it is easy to get that and are located in the same line. Then, considering triangle , we can find that either or is established. Because is located in the extended line of the segment, we can obtain inequality . As a consequence, a point exists and it belongs to H, which contradicts condition with inequality . Therefore, the above situation (II) is rejected.

As both assumptions above are not established, the only assumption left is accepted, which is . □

Based on Theorem 2, we have Theorem 3 to construct the ellipsoidal convex hull with Definitions 1 and 2.

Theorem 3

(Minimum-radius ellipsoidal convex hull). Given , let be the projection of the geometric center μ on to hyperplane . The ellipsoid centered at is the smallest (minimum-radius) ellipsoid, in the Mahalanobis metric, that encloses all samples in X.

Proof.

We define

In other words,

According to Theorem 1, the Mahalanobis and Euclidean metrics are distance-preserving under the transformation , so the radius computation in the Mahalanobis space can be equivalently performed in the Euclidean space:

According to Theorem 1, it is easy to get that is the farthest point away from and its length is . Then, We obtain the equation . Combining Theorem 1 with Equation (12), then,

According to Equation (14), an ellipsoidal convex hull with mean point and radius contains points within the point set. In this case, this indicates that it is the minimum ellipsoidal convex hull. □

Next, we provide Lemma 1 for the ellipsoid-structured convex hull construction.

Lemma 1

(Distance in Mahalanobis metric). In Mahalanobis metric space, distance between a sample v and the hyperplane is given by

and projection of a point to hyperplane . can be expressed as

Then we can have the concrete construction algorithm as follows (Algorithm 1).

| Algorithm 1 Ellipsoid-structured convex hull construction. |

|

Depending on the different relationships between a point and the convex hull, the distance of a sample to a convex hull is not absolutely the same in each situation. According to Algorithm 2, there are three relationships that exist between a point and a convex hull, which are overlap (), tangent (), and separation (). In this case, we divided these three situations into two groups, where overlap and tangent are categorized as the same group, while separation is in a second group. For the situation in group I, we calculate as the distance between the test sample and the hyperplane to measure the closeness between the test sample and hyperplane. For the situation in group II, we calculate as the distance between the test sample and the convex hull. Next, we present the distance calculation in Algorithm 2.

| Algorithm 2 Calculation of the distance to the ellipsoid-structured convex hull. |

|

3.3. Nonlinear EL-GEPSVMs

To deal with data in the nonlinear space, we can extend our proposed EL-GEPSVM to the nonlinear version. First, we present Theorem 5 to prove the existence of dual representation of the M-norm.

Theorem 4

(Kernelized EL-GELSVM). Given a d-dimensional dataset , the covariance matrix is , and its inverse matrix is , where is an eigenvalue of Σ, and represents the symmetric matrix. Let denote the kernel mapping, the dual representation of kernelized : , where .

Proof.

Assuming the covariance matrix to be positive-definite, we perform singular value decomposition (SVD) [29] and get

According Equation (17), we have

The covariance matrix with kernel mapping can be described as follows:

where .

Next, we define , and we can get

Next, we define , and we can get

Note that the covariance matrix in feature space can be expressed via the kernel trick as

where is the centered kernel matrix and . In this case, and the Mahalanobis distance can be computed solely through kernel evaluations. □

To generalize the proposed EL-GEPSVM from linear to nonlinear space, it is essential to prove that the Mahalanobis norm used in the ellipsoidal metric admits a kernel-compatible form. Theorem 5 establishes the dual representation of the M-norm, which provides the mathematical basis for kernelizing the EL-GEPSVM.

Theorem 5

(Dual representation of M-norm). Given d-dimensional dataset , there exists a dual representation of the squared M-norm:

where , , and .

Proof.

According to Definition 1, we square the M-norm and get

Theorem 5 shows that the proposed ELGEPSVM can be extended to a nonlinear version since the M-norm has dual representation for kernelization of the EL-GEPSVM. Therefore, considering the above Lemma 4 and Theorem 5, we can have the definition of a nonlinear EL-GEPSVM, which can be described as follows.

Definition 3

(Nonlinear EL-GEPSVM). Let be the samples in the class, and be the samples from the class. Considering the standard EL-GEPSVM (as defined in Definition 2), the nonlinear EL-GEPSVM learns the hyperplanes and in the nonlinear space with the kernelized EL-GEPSVM (Theorem 4) and M-norm (Theorem 5).

We summarize the proposed EL-GEPSVM method in Algorithm 3.

| Algorithm 3 EL-GEPSVM algorithm. |

|

3.4. Computational and Space Complexity Analysis

We analyze the computational and space complexity of Algorithms 1–3. In Algorithm 1, the calculation of the mean, covariance, and projection requires operations, respectively, where n is the number of samples and m the feature dimension. Considering the iterative operations in steps 3 and 4, the overall computational cost is . In Algorithm 2, for each data sample, the Mahalanobis distance computation requires time, resulting in an overall complexity of . In Algorithm 3, the total training cost is , while the inference phase requires per sample. For the kernelized version, the formation of the G ram matrix and its inversion introduce an additional cost. For the space complexity, the primary storage requirements come from the covariance matrix , the hyperplane parameters , and the mean vectors . Hence, the total space complexity is for the linear case. For the kernelized implementation, storing the Gram matrix requires space.

4. Experiments and Analysis

4.1. Experimental Data and Settings

We evaluated the proposed EL-GEPSVM method by designing the following experiments: (1) visualization of EL-GEPSVM, (2) experiments on multi-class classification with EL-GEPSVM, (3) parameter analysis, and (4) computational time analysis. In the first experiment, we visualized the construction of a convex hull in the EL-GEPSVM to show the feasibility and basic idea of the proposed algorithm. We demonstrated the performance of the EL-GEPSVM (the standard and kernelized versions) in the second experiments. Then, we performed parameter analysis to show the stability of the proposed algorithms with changing parameters as mentioned in Algorithms 1 and 3. Lastly, we tested the efficiency of the proposed algorithms in the fourth experiment. All experiments in this section follow the following settings:

Data: We utilized 11 datasets from the UCI repository [30] to evaluate the performance of linear and nonlinear EL-GEPSVMs on multi-class classification.

Comparisons: We made comparisons with 11 state-of-the-art methods including SVM-based methods and popular GEPSVM variants: SVM [9], SRC [31], SVM-2K [32], GEPSVM [2], LGEPSVM [10], TWSVM [27], GNPSVM [33], and L1GEPSVM [25].

Experimental setup: Our experiments and comparisons are based on data from the UCI repository and synthetic datasets. All experiments are conducted on an Intel Core(TM) i5-4210M 2.60GHz on MATLAB R2016a.

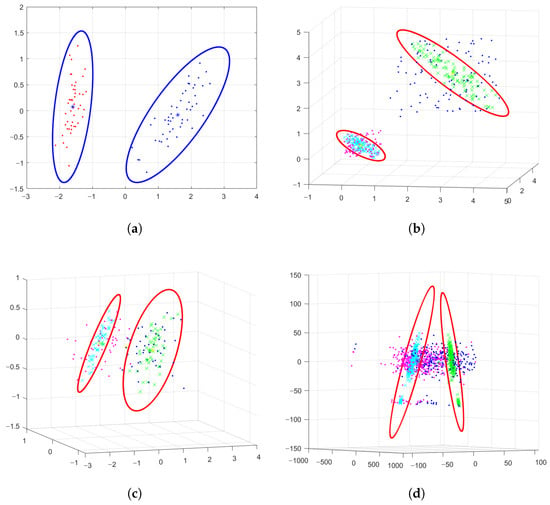

4.2. Visualization of EL-GEPSVM

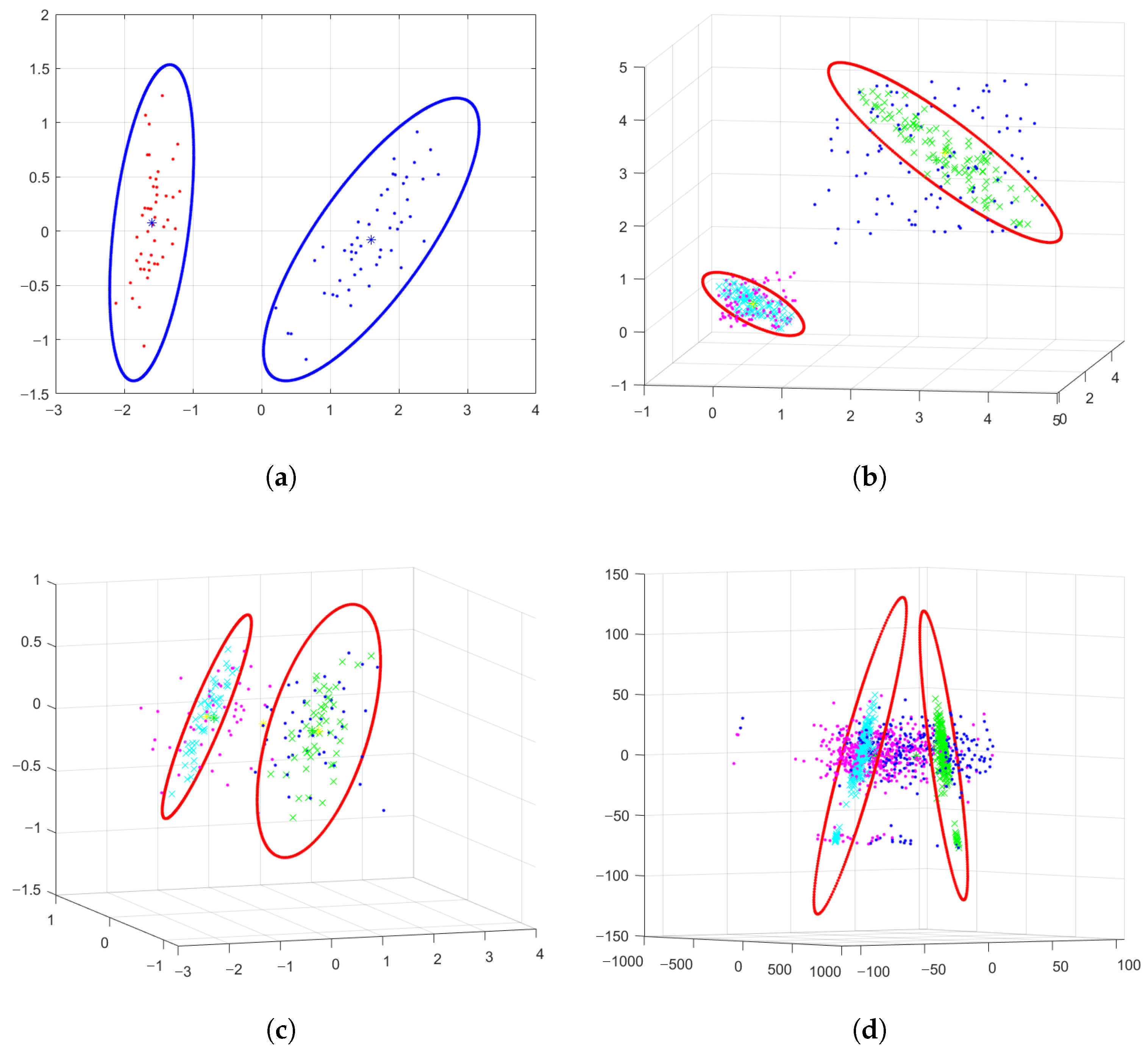

We visualized the EL-GEPSVM in Figure 2 on four datasets: Iris2D, Uniform3D, Iris3D, and Pimadata3D. For the Iris2D dataset, we selected classes 1 and 2 from the full iris dataset, then we projected the raw data samples to a 2D linear space with PCA algorithm. Similarly, for Iris3D, we selected classes 2 and 3 from the full iris dataset, then utilized PCA to reduce the dimensions of the raw data to three. For Uniform 3D, we randomly generated 100 data samples for two different classes. The samples of each class follow the uniform distribution. For Pimadata3D, we reduced the dimensions of raw data samples from the Pima dataset to three. According to Figure 2a–c, we can clearly see that the ellipsoidal convex hull supported by two hyperplanes can cover the sample of each category. Samples of two categories are projected to the hyperplane (in green and cyan colors). After the construction of two hyperplanes with the EL-GEPSVM, two ellipsoidal convex hulls are solved as well (two ellipses), which describe the location relationship between the convex hull and the projection points directly. The ellipsoidal convex hull is able to separate data from two categories for better classification. This shows that the ellipsoid-structured LGEPSVM can feasibly act as a classifier. From Figure 2d, the EL-GEPSVM makes a clear separation with convex hulls to distinguish samples from two different classes in 3D space. Each pair of projection points and the ellipse lie on the same plane, proving the correctness of Theorem 3 and Algorithm 1.

Figure 2.

Visualization of the proposed Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (EL-GEPSVM). The ellipsoids illustrate the localized convex hulls constructed in the Mahalanobis space, showing adaptive shapes that fit intra-class distributions. The subplots correspond to (a) Iris2D, (b) Uniform3D, (c) Iris3D, and (d) PimaData3D datasets.

4.3. Experiments on EL-GEPSVM

This experiment was conducted on the UCI dataset and a part of the synthetic dataset. In the synthetic dataset, iris12 is obtained from the iris dataset after PCA (Principal Component Analysis) processing, and the Cross2plane dataset is two crossing lines with uniform distribution noise added; these were used to validate the feasibility of the GEPSVM classifier in the XOR problem. We used 10-fold cross-validation to test the accuracy and demonstrate results through accuracy and standard deviation. Furthermore, we utilized a paired T-test as the test of statistical significance between the proposed EL-GEPSVM and LGEPSVM methods to make sure that the experimental results are reliable, and we quantify it by using the p-value. We performed the significance test with the LGEPSVM since the proposed method originates from it and can be taken as a variant of this method. In addition, we use the star notation (*) to indicate a significant difference. Results of linear kernel are recorded in Table 2. As to nonlinear circumstances, we utilized a Gaussian kernel whose results are demonstrated in Table 3.

Table 2.

Accuracies (%) and comparisons of the linear EL-GEPSVM and the state-of-the-art methods.

Table 3.

Accuracies (%) and comparisons of the kernelized EL-GEPSVM and the state-of-the-art methods.

In Table 2, we bold the highest accuracy of each row (dataset). Results of the linear EL-GEPSVM are listed in Table 2. Based on the results shown in Table 2, we can observe that the EL-GEPSVM not only achieves similar accuracy to the LGEPSVM but performs even better on some of the datasets, such as monk2 and waveform. Accordingly, it is fair to say that the MGEPSVM is equipped with a more powerful classification ability compared with the LGEPSVM in the linear kernel. Noticeably, we found our proposed method achieved lower performance than the highest accuracy in the comparison (L1-GEPSVM) on the monk3 dataset. Since our proposed method directly originates from the LGEPSVM, the achieved accuracy is still higher than that of the LGEPSVM, which demonstrates the superiority of introducing the ellipsoidal structure and Mahalanobis metric into the GEPSVM framework. This result suggests that although Mahalanobis-based convex modeling may not always outperform all variants in specific datasets, it provides a more stable and theoretically grounded decision representation that effectively balances local geometric information and intra-class covariance. Consequently, the performance on Monk3 highlights a trade-off between model generalization and dataset-specific adaptiveness, which will be further optimized in our future work. In addition, the paired T-test results demonstrate that these improvements are statistically significant rather than due to random variation. This consistency across multiple datasets suggests that the proposed Mahalanobis-based convex hull modeling enhances the robustness of large-margin learning. In Table 3, we denote the Gaussian kernel and polynomial kernel as EL-GEPSVM (G) and EL-GEPSVM (P). We can find that the EL-GEPSVM performs better compared with the GEPSVM and LGEPSVM, especially in Checkdata. What is noticeable is that although the EL-GEPSVM in the Water dataset has lower accuracy in the Gaussian kernel, its accuracy in the linear kernel is much higher than the other two classifiers, which reflects the fact that classification accuracy is changeable upon kernel selection. The kernelized EL-GEPSVM benefits from mapping the ellipsoidal boundary into a higher-dimensional reproducing kernel Hilbert space, where the Mahalanobis metric translates into a weighted inner product. This joint kernel–Mahalanobis interaction increases nonlinear discriminability while retaining the convexity of the original optimization. The empirical gains over the kernel GEPSVM highlight the robustness of our dual representation of the M-norm (Theorem 5) and its contribution to improved convergence stability.

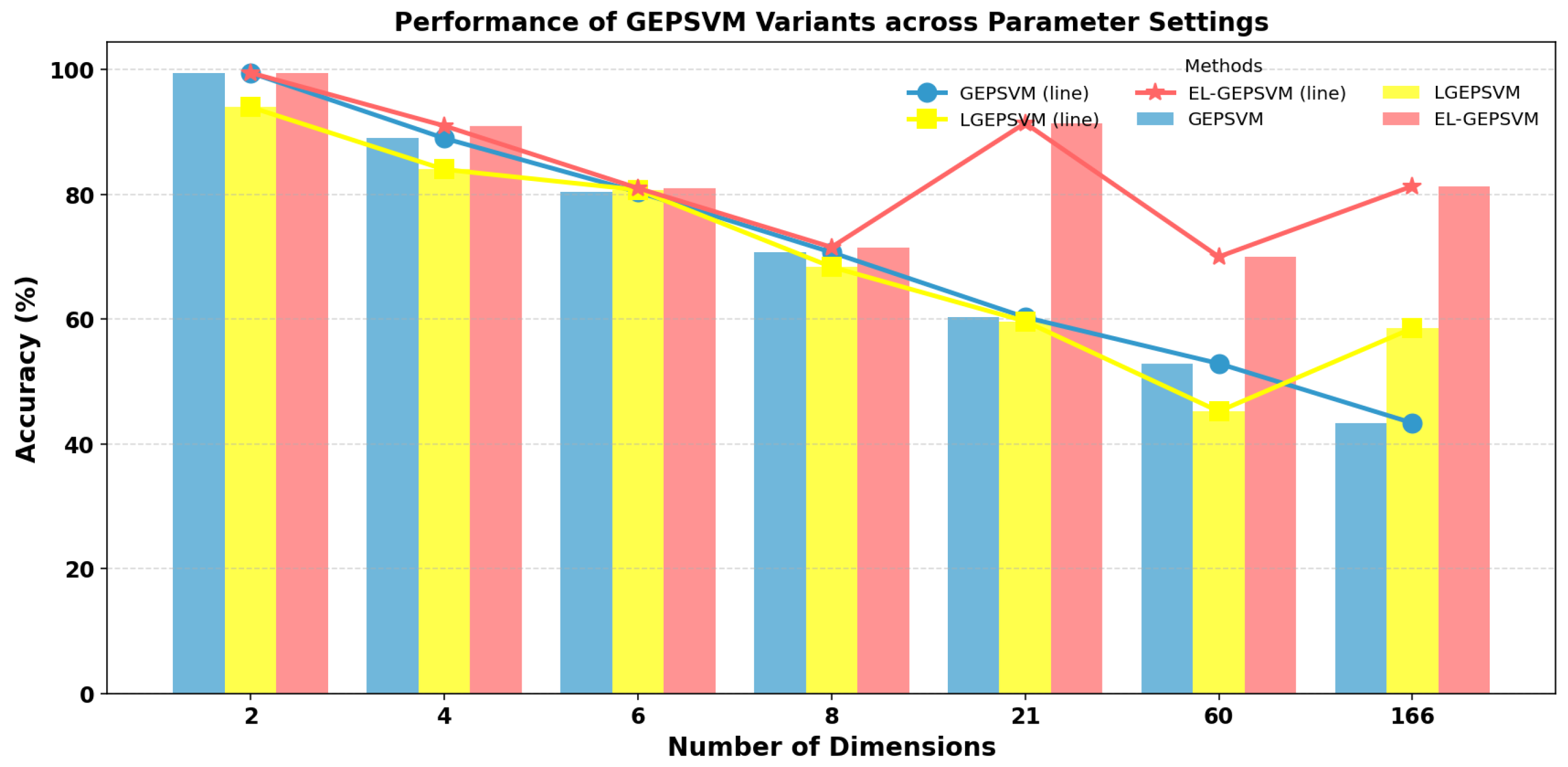

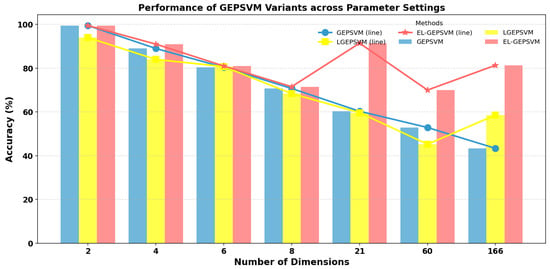

We show the performance tendency of the GEPSVM, the LGEPSVM, and the proposed EGEPSVM in Figure 3. As we find, when the number of dimensions of data is higher, the gap between the EL-GEPSVM and the other two methods becomes much larger. This indicates that the proposed method has a stronger ability to deal with data in high-dimensional space. Since the data distribution is more complicated in high-dimensional space, the difficulty will be higher in generating a separable hyperplane. This explains how the GEPSVM fails in high-dimensional space. Furthermore, the statistical information becomes more critical to the performance with a higher number of dimensions, which means the ELGPSVM will have superiority over the LGEPSVM in the high-dimensional space. As we can see in Table 2, our proposed EL-GEPSVM achieved the best performance in most cases (BUPA, Water, Checkdata, Pima). Although in cross2plane dataset, the proposed method did not obtain the highest accuracy, it is still the second highest (99.50%). The gap between the highest one (100%, TWSVM) and the proposed method is 0.5%.

Figure 3.

Comparative performance of GEPSVM, LGEPSVM, and the proposed EL-GEPSVM under varying feature dimensions. Bar colors represent the linear versions of each method (blue—GEPSVM, yellow—LGEPSVM, red—EL-GEPSVM), while the overlaid lines of corresponding colors indicate their kernelized counterparts. The x-axis denotes the number of dimensions, and the y-axis shows the classification accuracy (%).

Compared with the standard GEPSVM [2] and its variants, the proposed EL-GEPSVM achieves higher accuracy because the Mahalanobis-based ellipsoidal representation better captures class covariance and intrinsic geometry. Furthermore, we found the use of adaptive covariance weighting stabilizes the optimization, avoiding the numerical divergence observed in large-variance datasets. Theoretically speaking, this corresponds to an implicit regularization that aligns with the minimum-radius ellipsoidal convex hull, improving both margin stability and generalization.

To show how the proposed method deals with high-dimensional data, we show the performance of the GEPSVM, LGEPSVM, and proposed EL-GEPSVM on an increasing number of dimensions. Observing Figure 3, we find that the proposed EL-GEPSVM consistently achieves superior performance across most dimensional settings compared with the GEPSVM and LGEPSVM. In lower dimensions (e.g., two to eight), our proposed EL-GEPSVM yields notably higher accuracies, while in higher-dimensional cases, it maintains a smoother degradation curve, indicating stronger robustness to dimensional expansion. Overall, the EL-GEPSVM achieves the best trade-off between accuracy and scalability among the compared methods.

4.4. Parameter Analysis

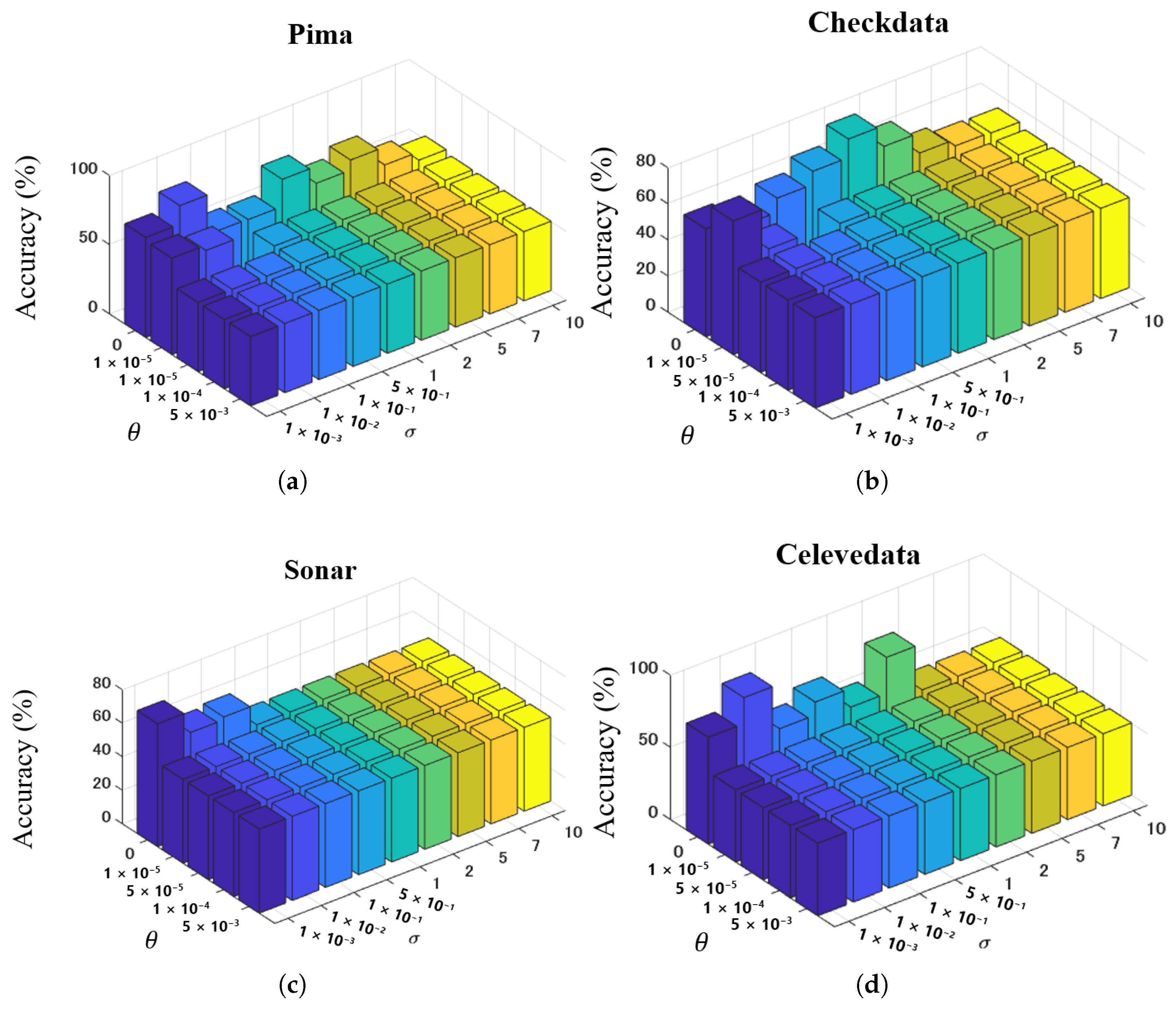

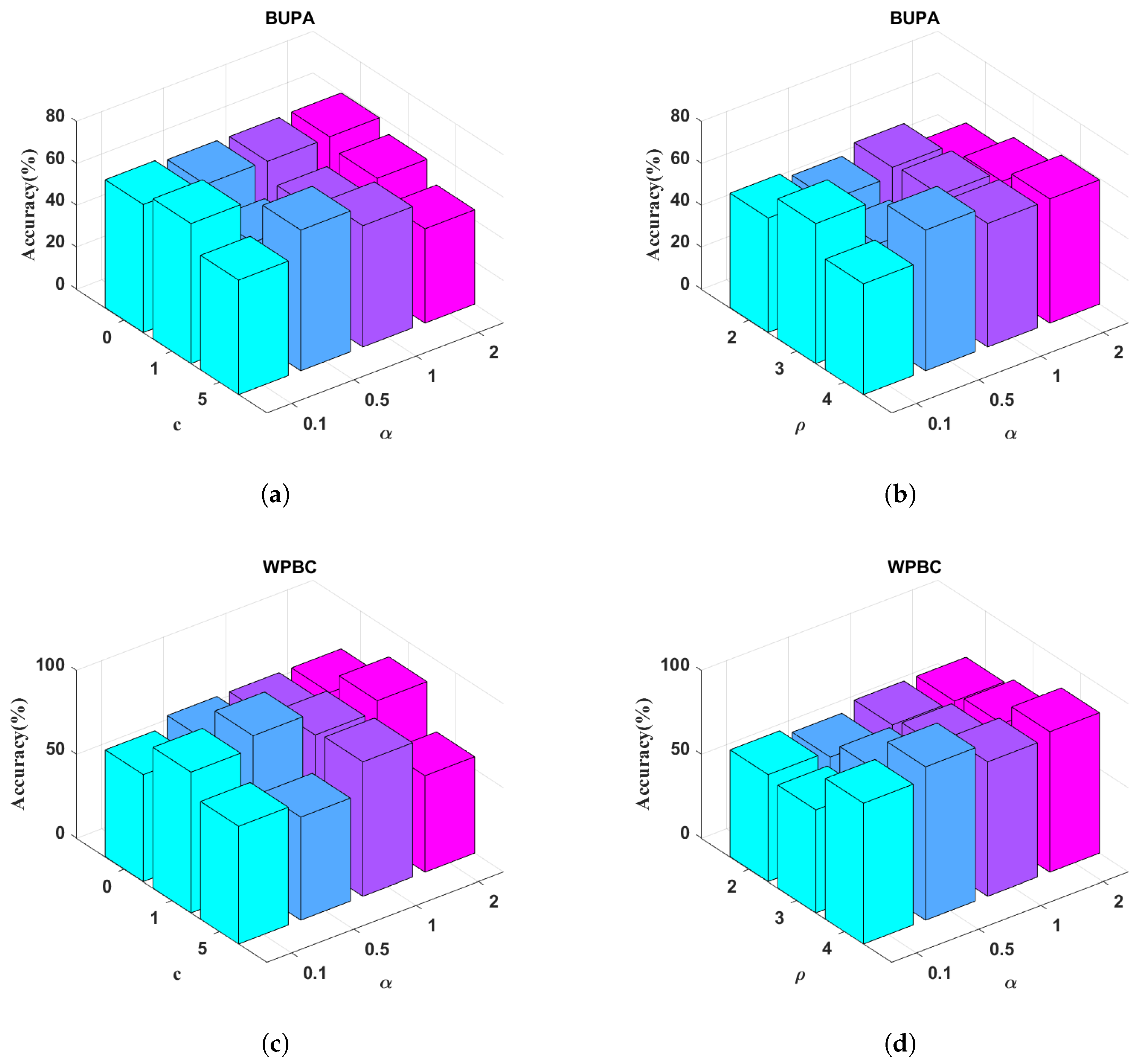

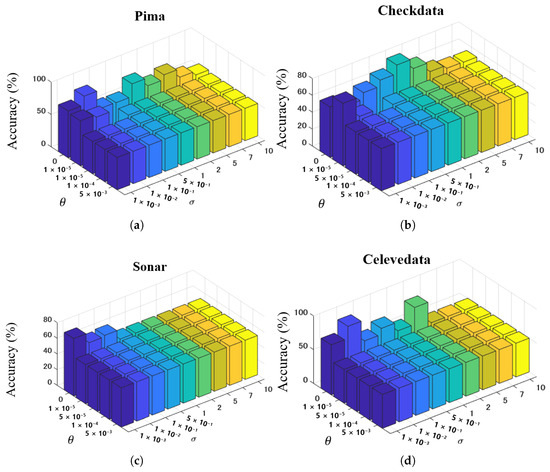

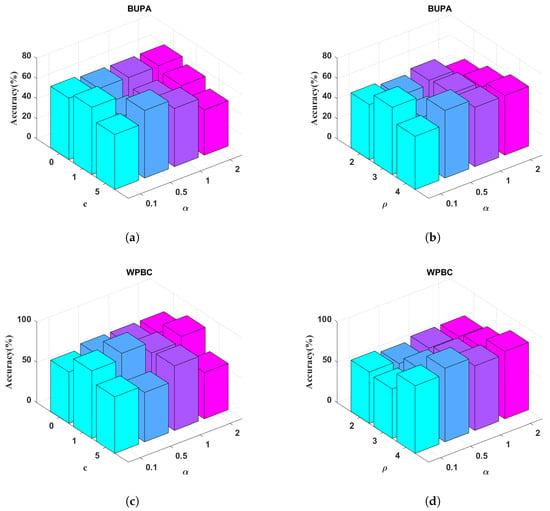

We performed parameter analysis of the proposed method on four datasets. We analyzed both regularization factor and the standard deviation in the E-LGEPSVM. We set and , then showed the performance of the method. The results are shown in Figure 4 and Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Parameter analysis of proposed EL-GEPSVM on and in (a) Pima, (b) Checkdata, (c) Sonar, and (d) Celevedata.

Figure 5.

Parameter analysis of proposed E-LGEPSVM on scaling factor , bias c, and degree in (a) BUPA [ vs. c], (b) BUPA [ vs. d], (c) WPBC [ vs. c], and (d) WPBC [ vs. d].

From Figure 4, we can observe the following: (1) The best performance of the proposed method is located in and . (2) The setting of is critical to the performance of classification. For example, in the Pima dataset (see Figure 4a), the proposed method shows better performance when setting a lower value. In contrast, the changing is stable when . (3) The accuracy varies when . In Checkdata (see Figure 4b), the highest accuracy is achieved when . In Sonar data, the highest accuracy is on . We also tuned the parameters of the polynomial kernel: scaling factor , bias c, and degree . The parameter analysis results on the BUPA and WPBC datasets are shown in Figure 5. The parameter analysis on the BUPA and WPBC datasets demonstrates that the performance of the EL-GEPSVM is sensitive to the choice of kernel parameters. However, stable high accuracies can be obtained within certain ranges. For BUPA, the best results are achieved when or , combined with moderate values [0.5, 1]. For WPBC, the method consistently performs well when or with an accuracy peak above 90% at . These results confirm that appropriate parameter selection can significantly enhance the performance.

Overall, the parameter analysis demonstrates that the proposed EL-GEPSVM maintains stable and high performance across a broad range of and values. For example, in WPBC, the polynomial kernel EL-GEPSVM achieves 91.25% ± 1.87%, outperforming the LGEPSVM (74.21%, Table 3) by nearly 17%, confirming robustness even in small-sample, high-dimension settings. In BUPA, stable regions appear when or with , maintaining accuracies between 66 and 68%, while WPBC keeps accuracies above 90% for or (see Figure 5). These consistent high-accuracy zones reveal that the proposed metric regularization term effectively bounds the covariance eigen-structure , ensuring smooth convergence and resilience against parameter perturbations. Hence, the method achieves both stability and interpretability under varying and , validating the theoretical claim that Mahalanobis-based regularization provides a well-conditioned optimization landscape.

4.5. Computational Time Analysis

We evaluated the efficiency of the EL-GEPSVM and made comparisons. As mentioned above, we proposed the EL-GEPSVM to improve the efficiency of the LGEPSVM. Since the LGEPSVM spends a large portion of its computational time on convex hull construction in the training stage, we mainly made comparisons on the convex hull construction among the EL-GEPSVM, GEPSVM, and LGEPSVM. The evaluation results are shown in Table 4 with the muskclean dataset. We also compared the efficiency with the state-of-the-art TWSVM method. Besides the computational time (Time) and accuracy (Accuracy), we also calculated the -score to evaluate the accuracy–time ratio of the comparison methods. This metric directly shows how much accuracy is achieved per second:

Table 4.

Computational time comparison on GEPSVM, LGEPSVM, and EL-GEPSVM on muskclean data.

In Table 4, the LGEPSVM takes 3.6 times the computation time that the GEPSVM takes in the classification period, while the EL-GEPSVM takes only 0.624 s, which is much less than the LGEPSVM. Obviously, the EL-GEPSVM increases the classification speed to a large extent (approximately 187% increase in speed) by reducing complexity in the convex hull construction. Due to the similarity in classification rules, both the LGEPSVM and EL-GEPSVM should compute distance for each point rather than compute in batches like the GEPSVM. In this case, they are slower than the GEPSVM. However, the EL-GEPSVM requires less storage room, which can be considered another advantage over the LGEPSVM and GEPSVM. Using the -score as an efficiency metric, the EL-GEPSVM achieves the highest score (1303.53), far surpassing the GEPSVM (121.22), LGEPSVM (43.67), and TWSVM (5.21), which highlights its outstanding efficiency advantage. We can see that although the TWSVM achieved the best performance on the muskclean data, it had the lowest -score in the comparison, indicating the low efficiency of the model. In contrast, the EL-GEPSVM obtained moderately acceptable performance with the least computational time and highest -score, showing its stronger ability to maintain a balanced trade-off between the performance and computational time.

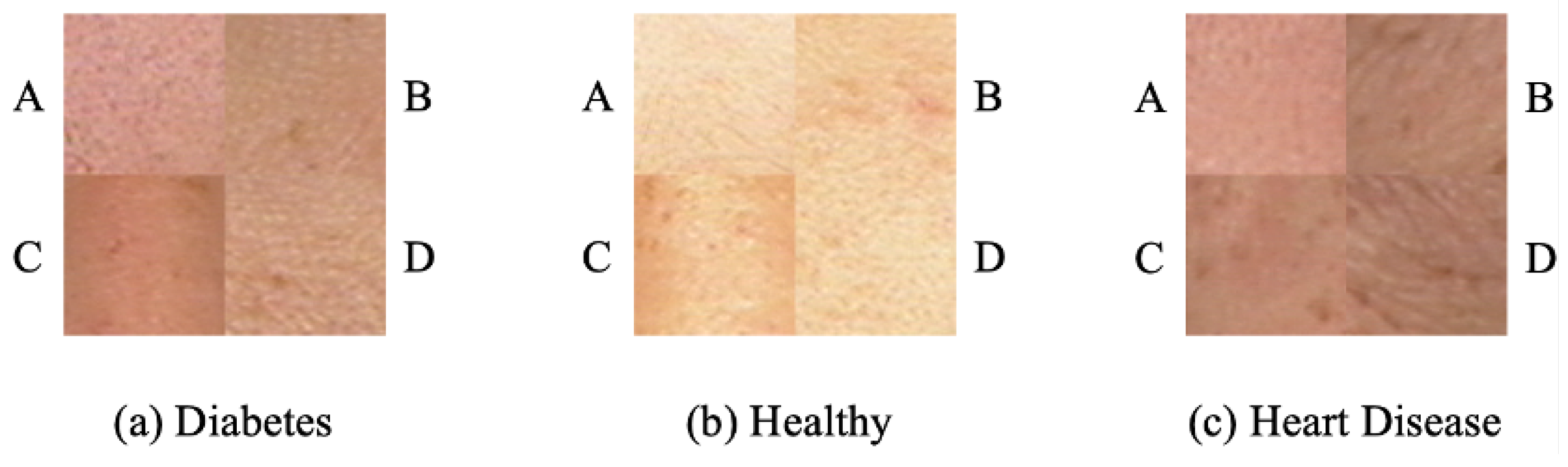

4.6. Application to Real-World Data

We performed validation using our proposed EL-GEPSVM method in a real-world application. The dataset is collected for medical biometrics [34], and it contains multimodal data such as face, tongue, sublingual vein, pulse, odor, etc. The idea of medical biometrics is to perform computerized disease diagnosis by observing human biometrics characteristics. In this experiment, we adopted face biometrics to detect diabetes and heart disease. Follow the idea in [35], four blocks from specific regions from the candidate’s face are extracted in the experiment. Examples of facial blocks are shown in the Figure 6. We show the validation results in Table 5. As shown in the results, we can observe that the proposed EL-GEPSVM achieved satisfactory performance when detecting diabetes and heart disease. Noticeably, we can see the precision of block A when detecting diabetes is 100%, indicating that the EL-GEPSVM could precisely capture the characteristics of diabetes and made a highly separable decision boundary. We also recorded the computational time of disease detection. The proposed method could use 0.0033 s and 0.0019 s to perform the detection. This shows the EL-GEPSVM’s efficiency and practical applicability in a real-world application.

Figure 6.

Samples of four blocks of diabetes, health control, and heart disease. A: block A, B: block B, C: block C, D: block D.

Table 5.

Validation results of proposed method for medical biometrics.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed the Ellipsoid-structured Localized Generalized Eigenvalue Proximal Support Vector Machine (EL-GEPSVM) for dealing with the underdetermined hyperplane problem (UPH). We utilized Mahalanobis distance for ellipsoidal convex hull construction to fully consider the local information and global information with statistical awareness. With the convex hull, the EL-GEPSVM unifies local and global information in pattern classification. In addition, we proved that the EL-GEPSVM is able to be kernelized for dealing with nonlinear data. The main novelty of this work lies in introducing the Mahalanobis-based ellipsoidal constraint into the GEPSVM framework, which enables adaptive class modeling through intra-class covariance and achieves a theoretically grounded distance-preserving property between Euclidean and Mahalanobis spaces. Furthermore, we established a kernelized dual representation for the M-norm, proving that the proposed ellipsoidal GEPSVM can be extended to nonlinear feature spaces while maintaining computational efficiency. Theoretical analysis and experiments showed that the EL-GEPSVM achieves higher accuracy and efficiency, especially in high-dimensional spaces. Experiments on several benchmarks show consistent gains over the GEPSVM/LGEPSVM and competitive baselines, together with a lower runtime in the linear case, indicating that modeling intra-class covariance and local geometry improves separability and stability of the learned hyperplanes. Since the establishment of the ellipsoidal convex hull in our proposed method does not organically integrate with GEPSVM optimization, in the future, we plan to explore the implementation of second-order cone programming to minimize the Mahalanobis distance on an ellipsoid under GEPSVM and LGEPSVM optimization frameworks. Furthermore, we will extend the EL-GEPSVM to larger and multimodal datasets using scalable kernel approximations and task-specific features.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Z.; Methodology, J.Z.; Validation, J.Z.; Formal Analysis, J.Z.; Investigation, X.Y.; Resources, Q.Z., X.Y., and J.G.; Data Curation, Q.Z. and X.Y.; Writing—Original Draft, J.Z. and X.Y.; Writing—Review and Editing, Q.Z. and J.G.; Visualization, Q.Z.; Supervision, X.Y. and J.G.; Project Administration, J.G.; Funding Acquisition, J.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Technology Development Fund of Macao under Grant 0002/2024/RIA1, and the National Natural Science Foundation of China No. 62506224.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ (accessed on 17 November 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Fung, G.; Mangasarian, O.L. Proximal support vector machine classifiers. In Proceedings of the Seventh ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 26–29 August 2001; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2001; pp. 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Mangasarian, O.L.; Wild, E.W. Multisurface proximal support vector machine classification via generalized eigenvalues. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2005, 28, 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, Q.; Yu, D.J.; Qi, Y. Robust GEPSVM classifier: An efficient iterative optimization framework. Inf. Sci. 2024, 657, 119986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Rajani, T.; Rastogi, R.; Shao, Y.H.; Ganaie, M. Comprehensive review on twin support vector machines. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 339, 1223–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.H.; Deng, N.Y.; Chen, W.J. A proximal classifier with consistency. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2013, 49, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooshmand, F.; Peik-Mortazavi, S. A novel convex-hull-based algorithm for classification problems with imbalanced and overlapping data. Expert Syst. Appl. 2026, 298, 129691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadir, A.; Ganaie, M.; Tanveer, M. Intuitionistic fuzzy generalized eigenvalue proximal support vector machine. Neurocomputing 2024, 608, 128258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Santillán, I.D.; Pajares, G. On-line crop/weed discrimination through the Mahalanobis distance from images in maize fields. Biosyst. Eng. 2018, 166, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervantes, J.; Garcia-Lamont, F.; Rodríguez-Mazahua, L.; Lopez, A. A comprehensive survey on support vector machine classification: Applications, challenges and trends. Neurocomputing 2020, 408, 189–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, S.; Yang, Y.M. Localized proximal support vector machine via generalized eigenvalues. Chin. J. Comput.-Chin. Ed. 2007, 30, 1227. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, B. Research on several key problems of mahalanobis metric learning and corresponding geometrical interpretaions. J. Nanjing Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2013, 49, 133–141. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, J.; Chen, M.; Zhang, H. Fault detection based on augmented kernel Mahalanobis distance for nonlinear dynamic processes. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2018, 109, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, M.P. On the Generalised Distance in Statistics; National Institute of Sciences of India: Prayagraj, India, 1936; Volume 2, pp. 49–55. [Google Scholar]

- Xiong, W.; Yu, G.; Ma, J.; Liu, S. A novel robust generalized eigenvalue proximal support vector machine for pattern classification. Pattern Anal. Appl. 2024, 27, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti, F.; Perracchione, E. Local-to-global support vector machines (LGSVMs). Pattern Recognit. 2022, 132, 108920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moutafis, P.; Leng, M.; Kakadiaris, I.A. An overview and empirical comparison of distance metric learning methods. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2016, 47, 612–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wei, W.; Liang, J.; Dang, C.; Liang, J. Metric learning via perturbing hard-to-classify instances. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 132, 108928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Y.; Fan, B.; Wu, F. Beyond mahalanobis metric: Cayley-klein metric learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 2339–2347. [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan, A.; Medikonda, J.; Namboothiri, P.K.; Natarajan, M. Mahalanobis metric-based oversampling technique for Parkinson’s disease severity assessment using spatiotemporal gait parameters. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 86, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, T.; Lei, Z.; Zhu, T.; Zeng, S.; Li, Y.; Yuan, C. Deep metric learning for K nearest neighbor classification. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2021, 35, 264–275. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Yang, L. Distance metric learning based on the class center and nearest neighbor relationship. Neural Netw. 2023, 164, 631–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Chen, S.; Zhou, H.; Sun, C.; Yuwen, L. CHSMOTE: Convex hull-based synthetic minority oversampling technique for alleviating the class imbalance problem. Inf. Sci. 2023, 623, 324–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.H.; Deng, N.Y. A coordinate descent margin based-twin support vector machine for classification. Neural Netw. 2012, 25, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanveer, M.; Tiwari, A.; Choudhary, R.; Ganaie, M. Large-scale pinball twin support vector machines. Mach. Learn. 2022, 111, 3525–3548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, T.; Yu, D.J.; Xu, Y. L1-norm GEPSVM classifier based on an effective iterative algorithm for classification. Neural Process. Lett. 2018, 48, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Xia, Y. Semi-supervised sparse least squares support vector machine based on Mahalanobis distance. Appl. Intell. 2022, 52, 14294–14312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayadeva; Khemchandani, R.; Chandra, S. Twin support vector machines for pattern classification. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2007, 29, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, S.; López, J.; Carrasco, M. A second-order cone programming formulation for twin support vector machines. Appl. Intell. 2016, 45, 265–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegner, S.A. Mathematical Introduction to Data Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bache, K.; Lichman, M. UCI Machine Learning Repository; University of California: Oakland, CA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, J.; Yang, A.Y.; Ganesh, A.; Sastry, S.S.; Ma, Y. Robust face recognition via sparse representation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2008, 31, 210–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farquhar, J.; Hardoon, D.; Meng, H.; Shawe-Taylor, J.; Szedmak, S. Two view learning: SVM-2K, theory and practice. In Proceedings of the 19th Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS 2005), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 5–8 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.N.; Ren, P.W.; Shao, Y.H.; Ye, Y.F.; Guo, Y.R. Generalized elastic net Lp-norm nonparallel support vector machine. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2020, 88, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Zuo, W. Medical Biometrics: Computerized TCM Data Analysis; World Scientific: Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, D. Noninvasive diabetes mellitus detection using facial block color with a sparse representation classifier. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 61, 1027–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).