Abstract

Motivated by the recent doubts concerning the compatibility of the purely imaginary one-dimensional cubic-oscillator model with the standard postulates of quantum mechanics, we propose to replace its potential by an elementary piece-wise constant function. We prove that such a simplified non-Hermitian model with a purely imaginary interaction potential still possesses infinitely many bound states with real energies. These states are shown to coincide, incidentally, with their Hermitian square-well analogues in the strong-coupling limit.

Keywords:

quasi-Hermitian quantum Hamiltonians; PT symmetry; purely imaginary square-well potential; construction of exact bound states; strong-coupling limit MSC:

81Q05; 81Q10

1. Introduction

In the context of the recently popular quasi-Hermitian [1,2], also known as -symmetric [3] or pseudo-Hermitian [4] reformulations of quantum mechanics, a key role of a benchmark toy-model example has been represented by the Hamiltonian

Besides the marginal phenomenological relevance of such a model in field theory [5,6] and in the related methodical studies of the properties of perturbation expansions [7,8], extensive studies were only initiated when Bender, with Boettcher, pointed out that the models of dynamics of such a type “may be viewed as analytic continuations of conventional theories from real to complex phase space” [9].

The idea became fairly influential [10,11]. The related and not quite expectable strict reality of eigenvalues of the toy model of Equation (1) proved quite puzzling. In the context of physics, it inspired a conjecture of the existence of the whole “modified quantum mechanics”, paying attention to many other Hamiltonians containing the anomalous complex potentials [12,13,14]. Within this upgraded theoretical framework, many new and interesting questions were raised by an underlying replacement of the current Hermiticity of Hamiltonians through an alternative condition. For example, Mezincescu [15] pointed out that one of the new challenges emerges in connection with the less usual forms of the asymptotic behavior of the wave functions [16,17,18].

During the early developments in the field, multiple innovative proofs of the reality of the energies emerged. They were based on the WKB and perturbation-expansion techniques [19,20] as well as on the algebraic and analytic constructions [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29]. New insight into these proofs was also obtained via the studies of the most elementary polynomial interactions [30,31,32].

From the point of view of experimental physics, the latter theoretical developments seem to have opened a broad new domain in the study of phenomena connected with such a change in paradigm, redirecting attention, e.g., to the well known but, until recently, rather formal concept of the so-called exceptional point (EP, [33]). In particular, especially the latter concept found, indeed, a broad new area of the real-world applicability ranging from classical optics [34] and non-linear optics [35,36] up to multiple new forms of various open systems [37,38,39].

The discovery and intensive experimental studies of the latter new classes of phenomena re-attracted, naturally, the attention of theoretical physicists (strongly inspired by the brand new ideas of an “analytically continued quantum mechanics” [9,16]) as well as of the much less enthusiastic mathematicians (who were always well aware of the deep subtlety of many related formal questions—see, e.g., [1,40,41]).

A climax in the latter skepticism can be dated back to the year 2012 when, in paper [42], Siegl, with Krejčiřík, published a rigorous mathematical proof that “the eigenvectors of the imaginary cubic oscillator do not form a Riesz basis” so that, as a consequence, “there is no quantum-mechanical Hamiltonian associated with it” [42].

Naturally, such a discovery (reconfirmed, in a not yet published preprint [43], by Günther and Stefani who, incidentally, used a rather different mathematical approach) was truly revolutionary. Indeed, in the abstract theoretical framework of the so-called quasi-Hermitian reformulation of quantum mechanics (QHQM; see, e.g., comprehensive reviews [1,2,4]) the problem of a correct physical interpretation of model (1) remains, at present, unresolved (cf., e.g., the recent review [44]).

2. Model

In such a context, we intend to propose here an extremely elementary symmetric model which would replace the BZ interaction (which admits just a numerical treatment) with its exactly solvable imaginary-square-well alternative

This means that we will consider and solve the ordinary differential Schrödinger equation

under the conventional Dirichlet boundary conditions

Putting , we will assume the unbroken symmetry. This means that at any energy (in the case of the unbroken symmetry, this energy will be real and positive [9]), we may abbreviate and obtain the asymptotically decreasing (i.e., normalizable though not yet normalized) wave function solutions such that

provided only that we set with and . We also recall that , and that as a consequence.

Due to the unbroken symmetry (cf., e.g., Ref. [45] for the details of this terminology) we will have wave functions such as so that we may analyze just their half-line part with and, in the limit, with a variable G in the conditions

Under the unbroken -symmetry, we may, therefore, work with the ansatz

with a purely imaginary constant . Now, our goal and intention is to guarantee the full compatibility of ansatz (6) with the boundary-value convention of Equation (5).

3. Matching Conditions at

The triplet of our most relevant parameters can be perceived as varying with an auxiliary variable ,

Moreover, using another complex upper-case parameter , we denote , and we deduce that

The conventional condition of the matching of the logarithmic derivatives at then implies that

As long as we may abbreviate and find the two solutions of such a quadratic algebraic equation. Their form is compact,

and it implies that in their fully expanded form we have two relations

Thus, what remains for us is to localize their real roots which have to be intrepreted as characterizing the two respective infinite series of bound states.

4. Energies

A more detailed analysis of our two final Equations (10) and (11) reveals that the simpler expressions and are just the slowly varying functions of their argument. This enables us to abbreviate , and to predict that

Next, due to Equation (7), both of our fundamental Equations (10) and (11) become simplified, significantly, by the change in notation,

It is now worth adding that there exists a possibility of a truly elegant further compactification of the two rules (10) and (11). For reasons which will be visible immediately (cf., in particular, Equation (13) below), it will make sense to abbreviate and . On these grounds, we may finally combine the two relations of Equation (12) and obtain the ultimate single secular equation

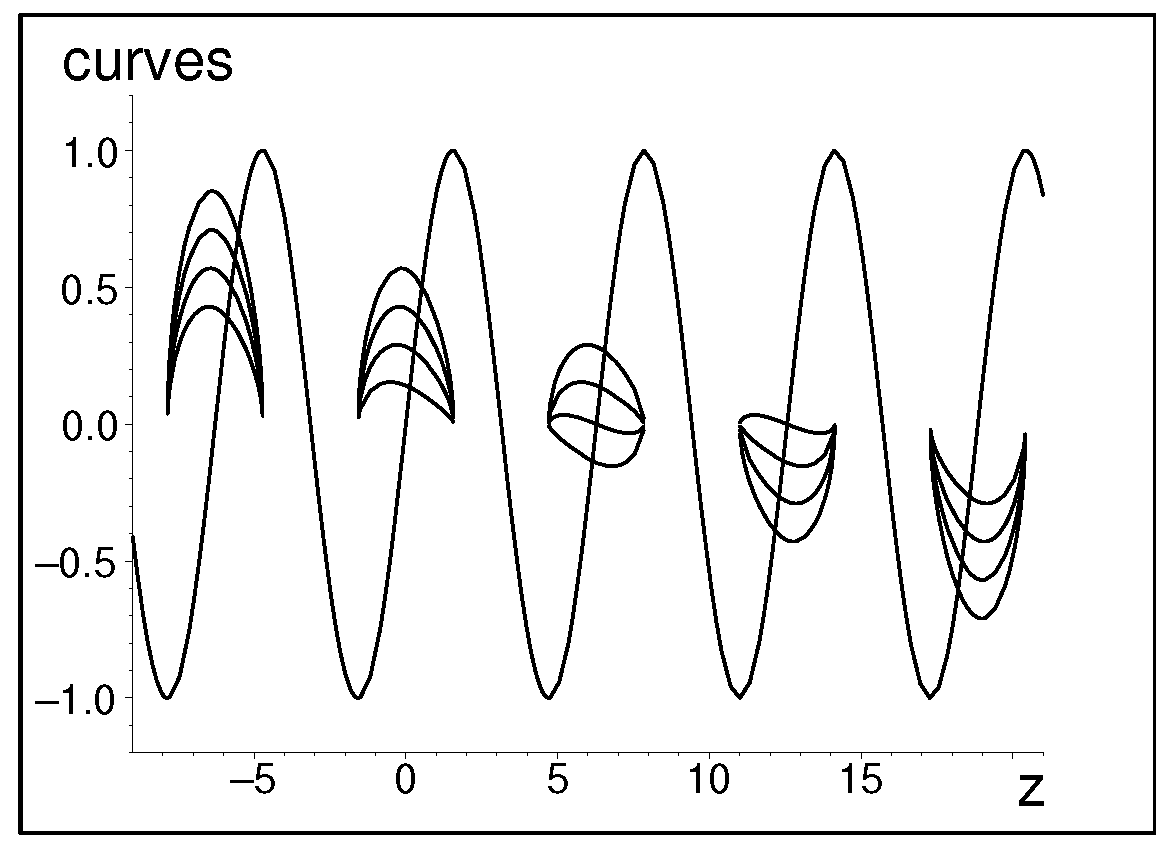

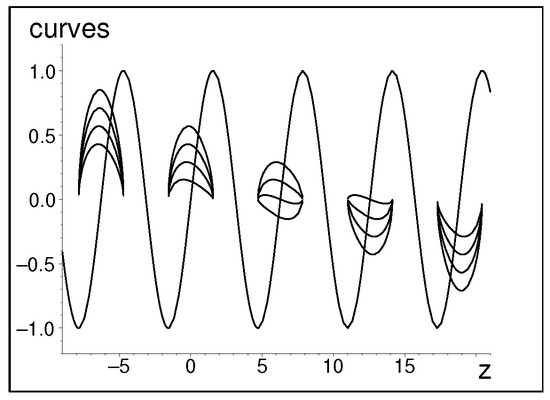

In a graphical interpretation (cf., e.g., Figure 1, which samples the graphical solution of the latter equation), this equation represents, at every level-counting integer N, an intersection of two sinus-like curves. One finds, therefore, infinitely many bound-state-energy roots which are numbered by the integer N.

Figure 1.

Graphical solution of Equation (13) at with for and 3).

5. The Case of the Small Square-Well Height

Once we have

(cf. Equation (8) together with (10) and (11)), we have a full control of the shape of our bound-state wave functions near the origin [one just has to insert in Equation (6)]. In this setting, another auxiliary abbreviation

enables us to rewrite our secular Equation (13) with unknown (cf. also Figure 1) in the following equivalent form

This is the common quadratic equation with two solutions, with the positive one having the elementary form

Obviously, this is just another, fully equivalent form of our secular equation.

In the domain of the large and almost constant (i.e., in the weak-coupling dynamical regime with small T, or at the higher excitations), our new secular Equation (15) gives a better picture of our bound-state parameters which all lie very close to 1. The estimate

represents also a quickly convergent iterative algorithm for the efficient numerical evaluation of the roots . One can conclude that in a way compatible with our a priori expectations, the value of is very close to zero and, as a consequence, the asymptotic decrease of our wave functions remains slow. We have so that, asymptotically, our wave functions very much resemble free waves . In the light of Equation (14), we also have near the origin.

6. The Case of the Large Square-Well Height

Let us now turn our attention to the opposite dynamical regime in which the constant T is small and the confinement is strong. In such a case (involving, typically, the low-lying excitations in a deep square well with ), of course, the values of R are small. This leads to the asymptotic expansion

Such a formula enables us to formulate several conclusions. Firstly, one can notice that there emerges an unexpected correspondence between our present model (based on a purely imaginary potential) and its conventional self-adjoint square-well analogue. Indeed, keeping their respective widths the same, , and moving the respective couplings to infinity, the respective spectra happen to coincide.

The wave functions exhibit the similar tendency towards the unexpected parallels. In the outer region, they are proportional to and decay very quickly since . The parameter becomes strongly superscript-dependent,

This means that in the interior domain of , the wave functions with the superscript (+) and (−) become dominated by their spatially even and odd components and , respectively. In this sense, the superscript mimics (or at least keeps the trace of) the quantum number of the slightly broken spatial parity .

Marginally, let us add that even at the finite Ts, the bound-state-energy values of our present imaginary square-well model grow quadratically with the quantum number N. Moreover, we may use the estimate

which implies that the individual energy levels remain, at any excitation quantum number N, well separated. This means that the spectrum does not exhibit a tendency towards the Kato’s exceptional-point degeneracy [33].

7. Outlook

Our present constructive demonstration of the exact solvability of a quasi-Hermitian quantum system with Schrödinger Equation (3) throws new light on the possible mathematical structures behind the symmetric quantum systems which may be hardly accessible by approximative techniques. In the current literature, many new puzzles emerging in the field are being revealed.

Pars pro toto, let us mention the Siegl’s and Krejčiřík’s [42] critical comments on the emergence of certain mathematical “intrinsic-exceptional-point” pathologies characterizing the full-fledged imaginary cubic oscillator model (1) (cf. also an outline of their various possible phenomenological consequences in [46]). Indeed, for the reasons explained in [44], one of the remedies of these physics-influencing pathologies could be sought in a suitable discretization of the Hamiltonian as sampled, here, by our present toy model of Equation (2).

Another more mathematically oriented open question which emerged in connection with a deeper study of the imaginary cubic oscillator problem was mentioned in ref. [47], in which the authors revealed the existence of an irregular behavior of the nodal zeros in the complex plane. Our present example indicates that a surprising alternative to the conventional and standard Sturm–Liouville oscillation theorem could, perhaps, emerge in connection with a deeper study of some other exactly solvable models.

Funding

This research was funded, partially, by the GA AS grant number Nr. A 104 8004.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Scholtz, F.G.; Geyer, H.B.; Hahne, F.J.W. Quasi-Hermitian Operators in Quantum Mechanics and the Variational Principle. Ann. Phys. 1992, 213, 74–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagarello, F.; Gazeau, J.-P.; Szafraniec, F.; Znojil, M. (Eds.) Non-Selfadjoint Operators in Quantum Physics: Mathematical Aspects; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, C.M. Making sense of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2007, 70, 947–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafazadeh, A. Pseudo Hermitian representation of quantum mechanics. Int. J. Geom. Meth. Mod. Phys. 2010, 7, 1191–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, M.E. Yang-Lee edge singularity and φ3 field theory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1978, 40, 1610–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.M.; Milton, K.A. Nonperturbative calculation of symmetry breaking in quantum field theory. Phys. Rev. D 1997, 55, R3255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliceti, E.; Graffi, S.; Maioli, M. Perturbation theory of odd anharmonic oscillators. Commun. Math. Phys. 1980, 75, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessis, D. (Service de Physique Théorique, CEA Saclay, Gif-sur-Yvette, France). Private communication, 1992.

- Bender, C.M.; Boettcher, S. Real specctra in non-Hermitian Hamiltonians having PT symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1998, 24, 5243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.M.; Milton, K.A. Model of supersymmetric quantum field theory with broken parity symmetry. Phys. Rev. D 1998, 57, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bender, C.M.; Milton, K.A. A Nonunitary Version of Massless Quantum Electrodynamics Possessing a Critical Point. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1999, 32, L87–L92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.M.; Boettcher, S.; Meisinger, P.N. PT-Symmetric Quantum Mechanics. J. Math. Phys. 1999, 40, 2201–2229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znojil, M.; Tater, M. Complex Calogero model with real energies. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2001, 34, 1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znojil, M. Three-Hilbert-space formulation of Quantum Mechanics. Symm. Integ. Geom. Meth. Appl. (SIGMA) 2009, 5, 001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezincescu, G.A. Some properties of eigenvalues and eigenfunctions of the cubic oscillator with imaginary coupling constant. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2000, 33, 4911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.M.; Turbiner, A. Analytic continuation of eigenvalue problems. Phys. Lett. A 1993, 173, 442–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buslaev, V.; Grecchi, V. Equivalence of unstable anharmonic oscillators and double wells. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1993, 26, 5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.; Guardiola, R.; Ros, J.; Znojil, M. A family of complex potentials with real spectrum. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1999, 32, 3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, G. Bender-Wu branch points in the cubic oscillator. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1995, 28, 4589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabaere, E.; Trinh, D.T. Spectral analysis of the complex cubic oscillator. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2000, 33, 8771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.M.; Boettcher, S. Quasi-exactly solvable quartic potential. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1998, 31, L273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannata, F.; Junker, G.; Trost, J. Schrödinger operators with complex potential but real spectrum. Phys. Lett. A 1998, 246, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabaere, E.; Pham, F. Eigenvalues of complex Hamiltonians with PT-symmetry. I. Phys. Lett. A 1998, 250, 25–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagchi, B.; Cannata, F.; Quesne, C. PT-symmetric sextic potentials. Phys. Lett. A 2000, 269, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Znojil, M. Shape invariant potentials with symmetry. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2000, 33, L61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znojil, M. Quasi-exactly solvable quartic potentials with centrifugal and Coulombic terms. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2000, 33, 4203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Znojil, M. PT-symmetrically regularized Eckart, Pöschl-Teller and Hulthén potentials. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2000, 33, 4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znojil, M. Spiked and PT-symmetrized decadic potentials supporting elementary N-plets of bound states. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2000, 33, 6825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lévai, G.; Znojil, M. Systematic search for PT-symmetric potentials with real energy spectra. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2000, 33, 7165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Znojil, M. PT–symmetric harmonic oscillators. Phys. Lett. A 1999, 259, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, A.; Mandel, B.P. A PT-invariant potential with complex QES eigenvalues. Phys. Lett. A 2000, 272, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.M.; Berry, M.; Meisinger, P.N.; Savage, V.M.; Simsek, M. Complex WKB analysis of energy-level degeneracies of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 2001, 34, L31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, T. Perturbation Theory for Linear Operators; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Rüter, C.E.; Makris, K.G.; El-Ganainy, R.; Christodoulides, D.N.; Segev, M.; Kip, D. Observation of parity-time symmetry in optics. Nat. Phys. 2010, 6, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranowicz, A.; Paprzycka, M.; Liu, Y.X.; Bajer, J.; Nori, F. Two-photon and three-photon blockades in driven nonlinear systems. Phys. Rev. A 2013, 87, 023809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konotop, V.V.; Yang, J.; Zezyulin, D.A. Nonlinear waves in PT-symmetric systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2016, 88, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moiseyev, N. Non-Hermitian Quantum Mechanics; CUP: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sergi, A.; Zloshchastiev, K.G. Non-Hermitian quantum dynamics of a two-level system and models of dissipative environments. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 2013, 27, 1350163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.Y.; Shen, H.Z. Photon blockade in non-Hermitian optomechanical systems with nonreciprocal couplings. Phys. Rev. A 2023, 107, 043715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dieudonné, J. Quasi-Hermitian operators. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Linear Spaces, Jerusalem, Israel, 5–12 July 1961; Pergamon: Oxford, UK; pp. 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Trefethen, L.N.; Embree, M. Spectra and Pseudospectra: The Behavior of Nonnormal Matrices and Operators; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Siegl, P.; Krejčiřík, D. On the metric operator for the imaginary cubic oscillator. Phys. Rev. D 2012, 86, 121702(R). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, U.; Stefani, F. IR-truncated PT -symmetric ix3 model and its asymptotic spectral scaling graph. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.08526. [Google Scholar]

- Znojil, M. The Intrinsic Exceptional Point: A Challenge in Quantum Theory. Foundations 2025, 5, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, F.; Guardiola, R.; Ros, J.; Znojil, M. Strong-coupling expansions for the -symmetric oscillators. J. Phys. A Math. Gen. 1998, 31, 10105–10112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krejčiřík, D.; Siegl, P.; Tater, M.; Viola, J. Pseudospectra in non-Hermitian quantum mechanics. J. Math. Phys. 2015, 56, 103513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, C.M.; Boettcher, S.; Savage, V.M. Conjecture on the interlacing of zeros in complex Sturm–Liouville problems. J. Math. Phys. 2000, 41, 6381–6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.