Abstract

Face unmasking is a critical task in image restoration, as masks conceal essential facial features like the mouth, nose, and chin. Current inpainting methods often struggle with structural fidelity when handling large-area occlusions, leading to blurred or inconsistent results. To address this gap, we propose the Masked-to-Unmasked Network (M2UNet), a segmentation-guided generative framework. M2UNet leverages a segmentation-derived mask prior to accurately localize occluded regions and employs a multi-scale, attention-enhanced generator to restore fine-grained facial textures. The framework focuses on producing visually and semantically plausible reconstructions that preserve the structural logic of the face. Evaluated on a synthetic masked-face dataset derived from CelebA, M2UNet achieves state-of-the-art performance with a PSNR of 31.3375 dB and an SSIM of 0.9576. These results significantly outperform recent inpainting methods while maintaining high computational efficiency.

Keywords:

face unmasking; image inpainting; U2-Net; generative adversarial networks (GANs); face mask removal MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

Image inpainting is a fundamental and long-standing problem in computer vision that aims to reconstruct missing or corrupted regions of an image while maintaining semantic coherence and perceptual realism. It serves as the foundation for a wide range of applications, including object removal [1,2,3,4], image restoration [5], and creative image editing [6,7,8,9]. Early inpainting methods relied on handcrafted priors and optimization strategies [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. While effective in propagating low-level textures and structures, these approaches often struggled to generate semantically meaningful completions when large or complex regions were missing. The advent of deep learning has significantly accelerated progress in this field, with convolutional neural network (CNN) and generative adversarial network (GAN)-based approaches [3,20,21,22] enabling models to learn high-level semantic priors and synthesize visually plausible results. More recently, transformer architectures [23,24] and diffusion-based methods [25,26] have pushed the boundaries of inpainting by capturing long-range dependencies and enabling iterative refinement. Furthermore, multimodal approaches [8,27] have emerged, integrating complementary modalities such as text guidance to further enhance semantic plausibility and controllability.

A specialized branch of image inpainting is face inpainting, which focuses on reconstructing corrupted or occluded facial regions. This task is particularly critical in biometric recognition, digital forensics, and entertainment, for which maintaining both structural fidelity and perceptual realism is essential. Unlike general natural images, human faces exhibit strict structural regularities, making even subtle distortions perceptually noticeable. Consequently, face inpainting becomes especially challenging under large occlusions that hide key facial components. Traditional approaches [10,18], which rely primarily on neighboring pixels or patch similarity, are insufficient in such cases, as they fail to capture global semantic structure. Successful face inpainting not only requires local pixel-level consistency in color and texture but also demands high-level attribute alignment between the reconstructed and observed regions. To address this, deep learning methods have incorporated structural priors such as edges [28], landmarks [29], or facial attributes [30] to guide the inpainting process. While these priors improve semantic plausibility, they also introduce sensitivity to inaccuracies in the auxiliary information, often resulting in visible artifacts.

Within this domain, a particularly relevant problem is face mask removal, or face unmasking, which gained interest during and after the COVID-19 pandemic as widespread mask usage became necessary. Face masks occlude semantically critical regions such as the nose, mouth, and chin, thereby degrading the performance of face recognition and other vision-based applications. Unlike generic occlusions, masks cover large, identity-defining regions, making unmasking significantly more challenging. To address this, existing approaches have either extended general-purpose inpainting frameworks to this task or developed multi-stage architectures tailored to unmasking [1,25,30,31]. Although these state-of-the-art methods have achieved notable progress, they frequently suffer from structural blurring and identity degradation when handling the large-area facial occlusions typical of masks.

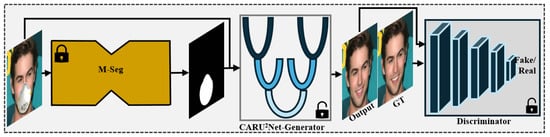

To address these challenges, we propose the Masked-to-Unmasked Network (M2UNet), a segmentation-guided GAN framework. In contrast to existing models, M2UNet combines explicit mask localization with a nested U2-Net architecture and channel attention mechanisms to ensure structural fidelity and identity preservation. The framework comprises two key components: (1) a pretrained Mask Segmentation (M-Seg) network, adapted from GANMasker [31], which generates binary mask maps to guide the inpainting process, and (2) a CARU2-Net generator enhanced with channel attention and paired with a spectral CNN discriminator, which synthesizes realistic and semantically consistent facial textures. Figure 1 illustrates the overall pipeline of the proposed framework along with representative examples of masked inputs, predicted masks, reconstructed outputs, and ground-truth faces. By integrating segmentation priors with a multi-scale, attention-driven generator, M2UNet effectively captures fine-grained details and reconstructs high-fidelity structures, even in the presence of large or complex occlusions. The proposed framework is evaluated on a synthetic masked-face dataset constructed by applying MaskTheFace [32] to CelebA [33]. However, it is important to distinguish the scope of this work: while our objective is to maximize structural and identity-preserving fidelity, the outputs generated via M2UNet are intended as plausible visual reconstructions that maintain semantic coherence, rather than guaranteed biometric recoveries of the individual’s true underlying identity.

Figure 1.

Overview of the proposed M2UNet framework. The pipeline consists of two stages: a pre-trained segmentation module (M-Seg) for binary mask generation, and a GAN-based inpainting network featuring a CARU2-Net generator with channel attention and a spectral-normalized discriminator.

The main contributions of our work can be summarized as follows:

- 1.

- We introduce M2UNet, a segmentation-guided GAN framework tailored to face unmasking, which explicitly leverages binary mask priors to better localize and restore occluded facial regions.

- 2.

- We propose the novel adaptation of the Nested U2-Net architecture—traditionally utilized for saliency detection—to the task of generative face inpainting. By integrating intra-stage multi-scale feature propagation, the rou CARU2-Net generator overcomes the information bottlenecks of standard U-Nets, enabling the precise recovery of fine-grained facial geometry and texture.

- 3.

- We provide a controlled evaluation setting by constructing a synthetic masked-face dataset using the MaskTheFace tool on CelebA, enabling a systematic assessment of face unmasking performance.

- 4.

- We conduct extensive experiments and demonstrate that M2UNet achieves superior performance compared to state-of-the-art methods, evaluated across five widely used metrics: the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), the Fréchet Inception Distance (FID), the L1 reconstruction error, and Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS).

2. Related Works

Image inpainting is a long-standing problem in computer vision that predates the rise of deep learning. Classical methods are generally divided into three families: interpolation-based, patch-based, and diffusion-based approaches. Interpolation methods estimate missing or corrupted pixels from neighboring information [10,11]. Patch-based approaches decompose the image into smaller patches and search for similar candidates in unmasked regions to reconstruct missing parts [12,13,14,15,16]. Diffusion-based methods rely on partial differential equations (PDEs) to iteratively propagate boundary information inward [17,18,19]. While effective for filling small gaps or extending low-level structures, these methods are limited due to their dependence on local features, often failing to generate semantically coherent or realistic content in complex cases.

With the advent of deep learning, inpainting research has shifted toward data-driven approaches capable of learning high-level semantic priors. Neural networks leverage large-scale datasets to reconstruct content that is both visually plausible and globally coherent. Over the past decade, several paradigms have been explored, most prominently GAN-based architectures, followed by transformers, diffusion models, and multimodal frameworks that integrate external cues.

2.1. GAN-Based Methods

Generative adversarial networks (GANs) have been central to the success of deep learning–based inpainting, offering sharper and more realistic completions than classical approaches. Pathak et al. [34] pioneered the use of an encoder–decoder with adversarial loss in Context Encoders, demonstrating the feasibility of learning semantically consistent completions. Iizuka et al. [20] improved upon this by introducing both local and global discriminators, while Yeh et al. [35] formulated semantic inpainting as an optimization problem in the latent space of pretrained GANs. For face images, Li et al. [30] developed a completion framework that integrates adversarial, reconstruction, and semantic parsing losses to preserve both global structure and local details in key regions such as the eyes and mouth.

Subsequent advances targeted free-form occlusions and irregular masks. Liu et al. [36] introduced Partial Convolutions, which confine convolutions to valid pixels, whereas Yu et al. [6] proposed Gated Convolutions to learn soft masks automatically. Liu et al. [22] further enhanced GAN-based pipelines with Channel and Spatially Adaptive Batch Normalization (CSA-BN) and Selective Latent-Space Mapping Contextual Attention (SLSM-CA), enabling adaptive normalization and multi-scale feature integration. Zuo et al. [21] proposed SCAT, which augments adversarial training with segmentation-guided feedback, combined with textural and semantic contrastive losses to improve alignment between generated and ground-truth features.

Another stream of work incorporated explicit structure guidance. Nazeri et al. [28] presented EdgeConnect, a two-stage framework that predicts missing edges before content synthesis. Similarly, Xu et al. [37] introduced E2I, which generates edge maps for edge-guided completion, while Yang et al. [29] combined landmark prediction with face inpainting to ensure identity and expression consistency. Works such as LaMa [3] and SmartFill [5] further demonstrated that semantic maps, user cues, or structural priors can be effectively combined with generative models to enhance realism and controllability.

In parallel, research has increasingly focused on face unmasking, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Din et al. [1] proposed a two-stage approach with mask segmentation, followed by GAN-based completion using local and global discriminators. Mahmoud et al. [31] introduced GANMasker, which augments this pipeline with a segmentation autoencoder, attention mechanisms, and a Masked–Unmasked Region Fusion (MURF) strategy for more accurate facial restoration. Building on these developments, we introduce M2UNet, a GAN-based model employing a nested U-Net generator with channel attention, specifically designed to achieve robust face unmasking. Despite the emergence of alternative paradigms such as transformers and diffusion models, GAN-based designs continue to provide a strong backbone for high-quality face restoration.

2.2. Transformer- and Diffusion-Based Methods

Beyond GANs, transformer architectures and diffusion models have recently gained traction for inpainting. Transformers, with their self-attention mechanisms, excel at modeling long-range dependencies and global context. Yu et al. [23] proposed BAT-Fill, a Bidirectional and Autoregressive Transformer that combines autoregressive pixel modeling with bidirectional masked–language reasoning for diverse and coherent generation. Wan et al. [38] developed a high-fidelity transformer with sparse attention to improve efficiency while maintaining structural integrity. Li et al. [24] introduced MAT, a mask-aware transformer that integrates local convolutions with global attention to balance fine detail and semantic consistency. Liu et al. [39] further refined this design with an encoder–decoder pipeline, where semantic correlations are captured globally and masked regions are reconstructed using structure–texture matching attention.

Diffusion models offer an alternative by iteratively denoising random noise into structured outputs, often achieving higher stability and fidelity than adversarial training. Lugmayr et al. [25] introduced RePaint, which employs resampling strategies to align known and generated regions. Zhang et al. [40] proposed COPAINT, a Bayesian framework that jointly updates revealed and unrevealed areas to ensure global coherence. Rombach et al. [7] presented Latent Diffusion Models (LDMs), which shift the generative process to a latent space and enable flexible conditioning via cross-attention layers. Most recently, Liu et al. [26] developed StrDiffusion, a structure-guided diffusion model with a two-stage denoising strategy—sparse structures guide early synthesis, while dense textures refine semantics—supported by adaptive resampling for coherent completion.

While these recent approaches have shifted toward transformer-based architectures (e.g., MAT [24]) or diffusion models (e.g., RePaint [25]) to capture long-range dependencies, they often incur high computational costs and suffer from slow inference times. Furthermore, diffusion models can introduce stochastic variations that compromise identity preservation in biometric tasks. In contrast, M2UNet demonstrates that maintaining a CNN-based inductive bias is advantageous for structural fidelity. By integrating Channel-Attention Residual (CAR) blocks within a nested U2 structure, we achieve the global receptive field benefits of transformers without their quadratic complexity, offering a distinct trade-off that balances efficiency with high-fidelity face unmasking.

2.3. Multimodal-Based Methods

A more recent trend integrates multimodal cues—such as text descriptions or facial attributes—into the inpainting process to enhance semantic plausibility and user controllability. Lin et al. [8] introduced MMFL, a text-guided framework that employs an image-adaptive word demand module, text-guided attention loss, and image–text matching loss to generate semantically consistent completions. Zhang et al. [41] proposed TDANet, which aligns image regions with textual descriptions through a dual-attention mechanism and image–text matching loss, enabling flexible text-driven restoration. Nichol et al. [9] extended multimodal inpainting into the diffusion paradigm with GLIDE, a text-conditional diffusion model that leverages classifier-free guidance to achieve photorealistic and text-consistent completions.

In the domain of face inpainting, multimodal guidance has been especially effective due to the importance of preserving identity and expression. Xiao et al. [42] developed AttrFaceNet, which predicts facial attributes from visible regions and uses them to guide completion, thereby improving consistency across gender, identity, and expression. Zhan et al. [27] proposed MuFIN, which fuses descriptive text and visual cues through a Multi-Scale Multi-Level Skip Fusion Module (MMSFM) and Multi-Scale Text-Image Fusion Block (MTIFB), allowing local and global cross-modal integration for high-fidelity reconstructions. Together, these works underscore that multimodal cues substantially enhance the semantic plausibility, controllability, and application potential of inpainting systems, particularly in tasks such as face unmasking.

3. Method

The proposed M2UNet is a segmentation-guided GAN framework designed specifically for face unmasking. It is composed of two sequential stages: (i) a segmentation stage that employs a pre-trained binary segmentation model (M-Seg) to identify occluded facial regions and generate a binary mask map and (ii) an inpainting stage that restores the missing regions using a GAN-based network. The inpainting stage integrates a CARU2-Net-inspired generator (denoted as G) and a lightweight discriminator (denoted as D) with spectral normalization. This design explicitly localizes masked areas and synthesizes realistic, high-fidelity facial reconstructions. The overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 1.

3.1. Segmentation Stage

The first stage of M2UNet employs the mask segmentation module (M-Seg) adapted from GANMasker [31]. This network predicts a binary mask map that explicitly identifies the occluded facial regions. The segmentation map serves as structural guidance for the inpainting stage, ensuring that the generator focuses reconstruction efforts only on the corrupted areas.

M-Seg is based on a modified autoencoder inspired by the U-Net architecture [43], further enhanced with the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) [44] to improve feature refinement and localization. By accurately delineating masked regions, M-Seg enables the reliable completion of occluded areas and facilitates high-quality face reconstruction. Since M-Seg is pre-trained and fixed in our pipeline, no additional training is required during the optimization of M2UNet.

The M-Seg module is adopted from GANMasker [31], where it was trained and evaluated on an identical synthetic configuration (CelebA processed via MaskTheFace). In that evaluation, the module demonstrated exceptional precision, achieving a Pixel Accuracy of 99.99% and a Dice Score of 99.97%. Given that our study utilizes the same dataset generation protocol, we leverage these pre-trained weights to ensure near-perfect mask localization, thereby minimizing the risk of error propagation to the inpainting stage.

3.2. Inpainting Stage

The inpainting stage serves as the core generative module of M2UNet, responsible for reconstructing realistic and semantically coherent facial regions in place of occluded areas. Building upon the segmentation stage, which identifies mask regions, this stage leverages a generative adversarial network (GAN) to synthesize plausible textures while preserving global structural coherence and identity features.

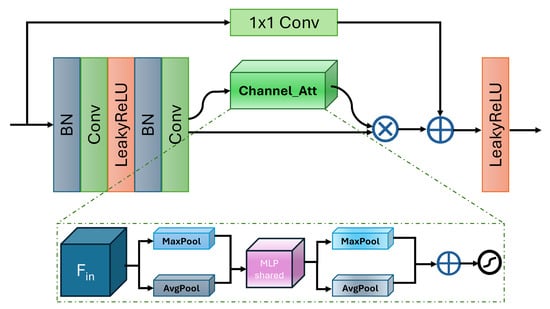

The backbone of this stage is built upon Conv-Attention Residual (CAR) blocks, illustrated in Figure 2, which enhance conventional residual connections with a channel attention mechanism. This design enables the network to emphasize informative features while selectively suppressing redundant ones. As a result, CAR blocks improve both structural fidelity and the synthesis of high-quality textures.

Figure 2.

Structure of the Conv-Attention Residual (CAR) block. The CAR block extends the conventional residual design by incorporating a channel attention mechanism.

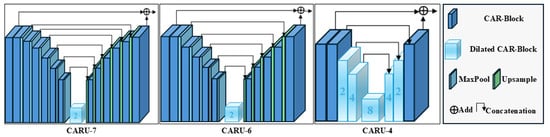

To capture multi-scale information, CAR blocks are organized into U-shaped encoder–decoder structures, called Conv-Attention Residual U-blocks (CARU). We employ multiple CARU variants—CARU-7, CARU-6, and CARU-4—each distinguished by its depth and use of dilated convolutions. CARU-7 and CARU-6 capture multi-scale contextual information through hierarchical encoding and decoding with skip connections, while CARU-4 leverages dilated convolutions to expand the receptive field without additional downsampling. Figure 3 illustrates the CARU variants side by side, highlighting their respective architectures and multi-scale feature propagation strategies. Together, these variants form a flexible and effective foundation for the inpainting generator, enabling fine-grained detail recovery and the robust handling of large occlusions.

Figure 3.

Overview of the Conv-Attention Residual U-block (CARU) variants used in the generator. From left to right, CARU-7, CARU-6, and CARU-4 are shown side by side, illustrating their encoder–decoder depths, skip connections, and multi-scale feature propagation strategies.

The choice of specific variants for each stage is based on the spatial resolution of the feature maps. In the outer stages (encoder and decoder), deeper CARU-7 and CARU-6 modules are employed because high-resolution maps require more hierarchical pooling levels within the nested block to capture the broad contextual information needed for large-area unmasking. At the bottleneck level, where spatial resolution is significantly reduced, the CARU-4 module is preferred; at this scale, additional nested pooling is computationally inefficient and risks losing spatial cues, whereas dilated convolutions can effectively capture long-range dependencies across the compressed features. This design enables the effective modeling of long-range dependencies across large occluded regions while maintaining computational efficiency and preventing over-smoothing. Together, this stage-wise configuration balances local detail recovery and global contextual reasoning within the generator.

- A.

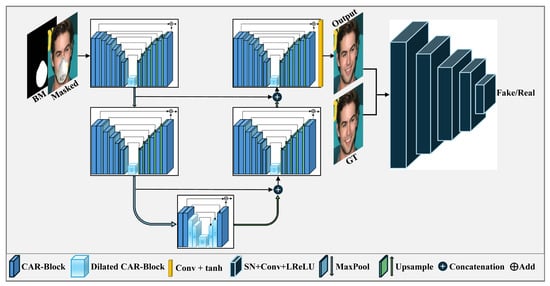

- Generator (CARU2-Net). The generator is responsible for reconstructing complete face images from masked inputs while preserving both global structure and local detail. Inspired by U2-Net, CARU2-Net nests Conv-Attention Residual U-blocks (CARU) inside a larger U-shaped encoder–decoder architecture, enabling multi-scale feature extraction and fine-grained detail reconstruction. To achieve this, the masked face image is concatenated with its binary mask map and passed to the network. The architecture follows a U2-Net backbone built from Conv-Attention Residual U-blocks (CARU), which we denote as CARU2-Net. The generator is organized into two encoder stages, a bottleneck, and two decoder stages, as illustrated in Figure 4. Each stage employs CARU variants (CARU-7, CARU-6, and CARU-4) designed to capture multi-scale contextual information while preserving fine-grained features through residual and channel-attention mechanisms. A final convolutional layer followed by a activation produces the three-channel unmasked output.

Figure 4. Architecture of the inpainting stage GAN for face unmasking. The generator (CARU2-Net) restores complete face images from masked inputs, while the discriminator guides the generator through adversarial learning to ensure photo-realistic reconstruction.

Figure 4. Architecture of the inpainting stage GAN for face unmasking. The generator (CARU2-Net) restores complete face images from masked inputs, while the discriminator guides the generator through adversarial learning to ensure photo-realistic reconstruction.- Encoder. The encoder consists of two hierarchical levels. The first level employs a CARU-7 module, composed of an input CAR layer followed by six CAR layers in the encoder path, interleaved with max-pooling for progressive downsampling. A dilated CAR layer with a dilation factor of 2 is introduced to enlarge the receptive field and improve contextual modeling. In the decoder path of the CARU block, the six CAR layers are mirrored by six upsampling operations. Skip connections are employed within the block, and the output of the input CAR layer is added to the final output, facilitating gradient flow and preserving local information. The second level employs a CARU-6 module, structurally similar to CARU-7 but with one fewer CAR layer (five instead of six). Both CARU-7 and CARU-6 modules are followed by max-pooling operations to progressively encode spatial hierarchies while maintaining discriminative feature representations.

- Bottleneck. At the network core lies the CARU-4 module. It begins with an input CAR layer, followed by three CAR layers in the encoder path with increasing dilation factors (1, 2, and 4), and symmetric layers in the decoder path with reversed dilation order. An additional CAR layer with a dilation factor of 8 is placed at the center of the module to further enlarge the receptive field without additional downsampling, enabling the robust modeling of long-range dependencies. Skip connections between the encoder and decoder sub-blocks within CARU-4 to facilitate effective information flow.

- Decoder. The decoder mirrors the encoder structure, using CARU-6 at the second level and CARU-7 at the first level. In contrast to the encoder, max-pooling operations are replaced by upsampling layers to recover spatial resolution. Skip connections concatenate encoder features with their corresponding decoder features, preserving fine spatial cues lost during downsampling. This design enables a sharper and more faithful reconstruction of facial details, even under large or irregular occlusions.

- Loss Function. The training of the generator is guided by a compound objective that balances realism, fidelity, and perceptual quality, as defined in Equation (1):where the weights are set to , , and . The reconstruction weight is assigned a significantly higher magnitude to enforce strict structural fidelity, ensuring that global facial geometry is preserved under large-area occlusions. This configuration aligns with established practices in face inpainting literature (e.g., GUMF [1], MuFIN [27]), where strong pixel-level supervision serves as an optimization anchor to prevent geometric distortion. The adversarial and perceptual terms act as complementary regularizers, refining high-frequency textures and enforcing semantic consistency to counteract the smoothing effects of the reconstruction loss.Adversarial Loss. The adversarial component drives the generator to synthesize outputs that the discriminator classifies as real. We employ the least-squares GAN (LSGAN) formulation [45] with one-sided label smoothing, as expressed in Equation (2):where D is the discriminator and denotes the generator output. Here, is the softened real label, which stabilizes adversarial training and reduces the risk of gradient saturation.Reconstruction Loss. To enforce pixel-level fidelity, we combine Smooth L1 loss with structural similarity (SSIM) into a hybrid objective, shown in Equation (3):where y is the ground-truth unmasked image. This hybrid formulation promotes both local accuracy and structural consistency.Perceptual Loss. The perceptual term measures semantic similarity in a pretrained VGG feature space, as given in Equation (4):where denotes the activation map of the l-th VGG layer. This encourages the generator to produce perceptually realistic textures and semantically faithful reconstructions.

Together, these architectural components and loss functions ensure that CARU2-Net achieves a balance between structural correctness, visual realism, and semantic coherence in face unmasking. - B.

- Discriminator. The discriminator is implemented as a five-layer convolutional network with spectral normalization [46], as illustrated in Figure 4. Spectral normalization stabilizes adversarial training by constraining the Lipschitz constant, preventing gradient explosion and mode collapse. Each convolutional layer employs kernels with a stride of 2 for the first three layers and a stride of 1 for the last two layers, combined with LeakyReLU activations (). The channel configuration progresses as , gradually increasing feature depth while reducing spatial resolution.To further improve stability, we adopt a least-squares adversarial formulation (LSGAN) with one-sided label smoothing [45]. Real samples are assigned a softened label, , and fake samples a label, , reducing overconfidence in the discriminator and mitigating oscillations during training. The discriminator loss is defined in Equation (5):where denotes the discriminator output for a real image, x, and for a generated image. Here, and are the softened real and fake labels, respectively.This design ensures that the discriminator effectively distinguishes real from generated samples while providing stable adversarial gradients that guide the generator toward photorealistic face reconstructions.

4. Experiments and Results

In this section, we present extensive experiments to evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed M2UNet framework. We benchmark our method against several state-of-the-art approaches in face unmasking. We first describe the dataset and implementation details, followed by quantitative and qualitative evaluations, and conclude with an ablation study analyzing the contribution of each component in M2UNet.

4.1. Dataset and Training Details

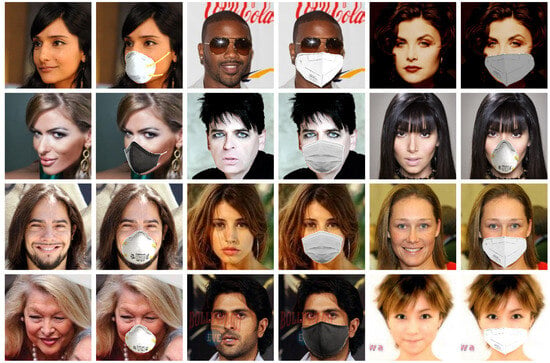

A key challenge in face unmasking is the lack of publicly available paired masked– unmasked face datasets. To address this issue, we construct a synthetic dataset using the MaskTheFace tool [32], which programmatically overlays various types of masks (e.g., surgical, cloth, KN95) with different shapes, colors, and structures onto facial images. We apply this tool to the widely used CelebA dataset [33], which contains over 200,000 celebrity face images commonly employed in facial analysis tasks. From CelebA, we randomly select 12,000 images, resize them to , and generate their corresponding masked versions. The resulting dataset is divided into 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. Figure 5 presents representative samples from this synthetic dataset, highlighting its diversity and visual quality.

Figure 5.

Synthetic dataset examples showing unmasked faces and their paired masked versions. The dataset includes diverse mask types, shapes, and colors to simulate realistic occlusion scenarios.

Our M2UNet framework is implemented in PyTorch (v2.4.1 with CUDA 12.1 support) [47]. The inpainting stage (GAN) is trained while the segmentation stage leverages a pretrained M-Seg model without additional fine-tuning. Network parameters are optimized using the Adam optimizer [48] with an initial learning rate of , which is decayed by a factor of 0.1 at 50,000, 75,000, and 90,000 iterations. Training is performed for 100 epochs with a batch size of 8. All experiments are conducted on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU (24 GB), CUDA v12.1, and Windows 10. To ensure the reproducibility and stability of the reported results, all experiments were conducted using fixed random seeds for both weight initialization and dataset splitting. Furthermore, unlike diffusion-based methods, which exhibit stochasticity during inference, the proposed M2UNet operates deterministically during the testing phase, ensuring that the generated reconstructions remain consistent across multiple evaluation runs.

4.2. Results

We comprehensively evaluate the performance of M2UNet for the task of realistic face mask removal through both quantitative and qualitative comparisons against eight state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods: GLCIC [20], GatedConv [6], GUMF [1], RePaint [25], CoPaint [40], SCAT [21], GANMasker [31], and MuFIN [27]. Among these, GUMF and GANMasker are specifically tailored to the face unmasking problem, while GLCIC, GatedConv, and SCAT represent GAN-based inpainting approaches primarily designed for general face completion. In contrast, RePaint and CoPaint are diffusion-based models, and MuFIN stands as the only multimodal approach included in the comparison. To ensure a fair and robust evaluation, we benchmark M2UNet against these methods under identical experimental settings. The results are presented in two parts: (1) quantitative comparisons using standard metrics, and (2) qualitative comparisons through a visual inspection of reconstructed faces.

- 1.

- Quantitative Comparisons We evaluate M2UNet using five widely adopted quality metrics: PSNR, SSIM [49], FID [50], loss, and LPIPS [51]. PSNR and SSIM measure fidelity and structural similarity, where higher values indicate better reconstruction quality. Conversely, lower values for FID, loss, and LPIPS correspond to more realistic image distributions, reduced pixel-wise errors, and improved perceptual similarity. Additionally, to address the critical requirement for practical deployment, we report three computational efficiency metrics: model parameters (Params), floating-point operations (FLOPs), and inference time.As is presented in Table 1, M2UNet achieves state-of-the-art restoration quality, surpassing all competing approaches in PSNR (31.34 dB) and SSIM (0.9576). Notably, M2UNet outperforms recent diffusion-based models (RePaint, CoPaint) and multimodal models (MuFIN) in fidelity metrics while maintaining a fraction of their computational cost. The generator contains only 3.17 million parameters, which is approximately half the size of the second-best GLCIC (6.07 M) and over 100× smaller than RePaint (552 M). Furthermore, with a computational cost of just 42.53 GFLOPs—the lowest among all compared models—M2UNet achieves an inference time of 0.12 s. This unique balance validates the effectiveness of the proposed Nested U2 architecture and CAR blocks, demonstrating that high-fidelity restoration can be achieved without the massive computational burden typically associated with modern diffusion or multimodal architectures.

Table 1. Quantitative comparison of M2UNet with state-of-the-art methods on the CelebA validation set. The table reports restoration quality metrics (PSNR, SSIM, FID, L1, and LPIPS) alongside computational efficiency measures, including model parameters, FLOPs, and inference time. Arrows indicate the desired direction (↑ higher is better, ↓ lower is better). The best-performing results are highlighted in bold, while the second-best results are underlined.

Table 1. Quantitative comparison of M2UNet with state-of-the-art methods on the CelebA validation set. The table reports restoration quality metrics (PSNR, SSIM, FID, L1, and LPIPS) alongside computational efficiency measures, including model parameters, FLOPs, and inference time. Arrows indicate the desired direction (↑ higher is better, ↓ lower is better). The best-performing results are highlighted in bold, while the second-best results are underlined. - 2.

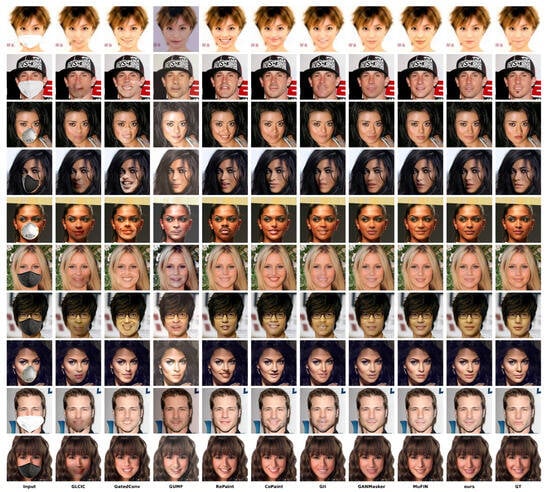

- Qualitative ComparisonsWhile quantitative metrics provide an objective evaluation, perceptual realism and visual fidelity are best assessed qualitatively. Figure 6 shows ten randomly selected masked face samples and the corresponding outputs of M2UNet compared with SOTA methods. M2UNet effectively restores occluded facial components such as the mouth, nose, and cheeks, producing sharper textures, consistent coloring, and natural expressions. In contrast, competing approaches often yield blurred, distorted, or artifact-prone outputs. Moreover, M2UNet demonstrates robustness across diverse mask types, sizes, and colors, as well as variations in age, gender, and skin tone. These observations confirm that the combined effect of segmentation guidance and the CARU2-Net generator leads to more perceptually convincing and identity-preserving reconstructions.

Figure 6. Qualitative comparison of inpainting results. Each row shows an example masked input image, followed by the outputs of representative SOTA and M2UNet, with the ground-truth face in the final column.

Figure 6. Qualitative comparison of inpainting results. Each row shows an example masked input image, followed by the outputs of representative SOTA and M2UNet, with the ground-truth face in the final column. - 3.

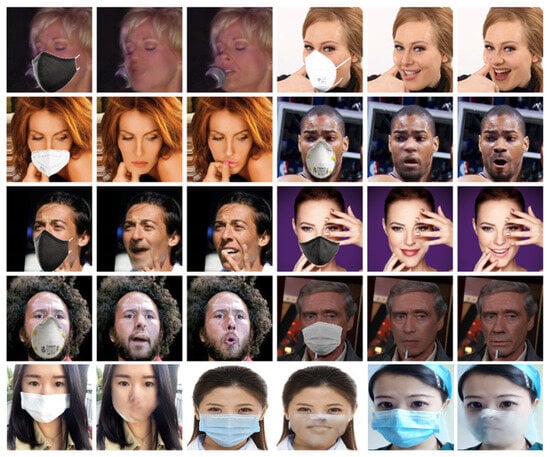

- Limitations and Failure CasesWhile M2UNet demonstrates robust performance across quantitative and qualitative benchmarks, it exhibits certain limitations that define its operational boundaries. As illustrated in Figure 7, the model encounters challenges in scenarios involving extreme facial poses (e.g., full profile views), excessively large masks that occlude the majority of facial landmarks, or complex cases featuring multiple overlapping occlusions, such as a mask combined with a microphone or a hand. In these instances, the generator may fail to preserve global structural coherence.

Figure 7. Representative failure cases of M2UNet. The first four rows compare the input masked images, our model’s reconstructions, and the corresponding ground-truth images for synthetic data. The bottom row showcases failures on real-world masked images.Furthermore, a notable performance gap exists when applying the framework to real-world masked faces (Figure 7, bottom row). Because the model is trained on simulated data, it occasionally fails to generalize to the intricate textures, varying lighting conditions, and diverse geometries characteristic of physical masks. These failures are primarily rooted in the inherent bias of the synthetic training set, which lacks “in-the-wild” variance and predominantly features frontal orientations.Consequently, bridging this synthetic-to-real gap represents a primary direction for future research. Enhancing the model’s robustness through the incorporation of diverse real-world datasets and the exploration of domain-invariant training strategies will be essential for ensuring reliable, high-fidelity unmasking under unconstrained conditions.

Figure 7. Representative failure cases of M2UNet. The first four rows compare the input masked images, our model’s reconstructions, and the corresponding ground-truth images for synthetic data. The bottom row showcases failures on real-world masked images.Furthermore, a notable performance gap exists when applying the framework to real-world masked faces (Figure 7, bottom row). Because the model is trained on simulated data, it occasionally fails to generalize to the intricate textures, varying lighting conditions, and diverse geometries characteristic of physical masks. These failures are primarily rooted in the inherent bias of the synthetic training set, which lacks “in-the-wild” variance and predominantly features frontal orientations.Consequently, bridging this synthetic-to-real gap represents a primary direction for future research. Enhancing the model’s robustness through the incorporation of diverse real-world datasets and the exploration of domain-invariant training strategies will be essential for ensuring reliable, high-fidelity unmasking under unconstrained conditions.

4.3. Ablation Study

To better understand the contribution of each component in M2UNet, we conducted an ablation study by systematically enabling or disabling the segmentation module and the channel attention mechanism, as well as varying the generator depth. All experiments were trained with identical hyperparameters and epochs to ensure fairness. During evaluation, a binary mask map was applied for all models (including those without segmentation) to ensure comparisons focused solely on the restoration regions.

The evaluated variants include: (i) a base model without segmentation and without attention (five-stage generator), (ii) a base model with channel attention but no segmentation (five-stage), (iii) a base model with segmentation but no attention (five-stage), (iv) a base model with segmentation but a reduced generator depth (three-stage), (v) a base model with segmentation and attention but a reduced generator depth (three-stage), and finally (vi) the full M2UNet with segmentation, attention, and a five-stage generator.

The quantitative results of all variants are summarized in Table 2, evaluated across five metrics: PSNR, SSIM, FID, L1, and LPIPS, with arrows indicating the desired direction of improvement (↑ higher is better; ↓ lower is better). The findings confirm that both segmentation guidance and channel attention enhance model performance, offering complementary strengths. Notably, their integration within the full five-stage generator delivers the most consistent improvements, yielding higher-fidelity reconstructions and closer alignment with ground-truth images.

Table 2.

Quantitative ablation results for M2UNet variants on the CelebA validation set. Seg. = segmentation stage, Att. = channel attention. The arrows indicate the desired direction (↑ higher is better; ↓ lower is better). The best results are highlighted in bold and the second-best with underline.

Interestingly, some three-stage variants (e.g., Base + Seg. + Att. (3-Stage)) achieve performance that is close to their five-stage counterparts. This can be attributed to the strong structural guidance provided by the segmentation module, which reduces the reliance on deeper encoding–decoding hierarchies. Nevertheless, the full five-stage M2UNet remains the most effective overall, particularly in perceptual metrics such as LPIPS.

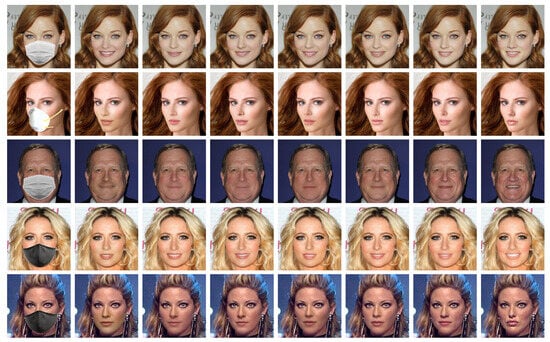

Qualitative comparisons in Figure 8 further illustrate these trends: models without segmentation or attention tend to produce blurrier or artifact-prone restorations, whereas the full M2UNet generates sharper, more realistic, and identity-preserving unmasked faces across diverse conditions.

Figure 8.

Qualitative ablation results of M2UNet variants. Each row presents a masked input image, followed by the outputs of ablated versions in the order described in the text, our full M2UNet, and finally the ground truth. The complete model delivers the most realistic and artifact-free reconstructions.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

In this work, we have introduced M2UNet, a robust segmentation-guided GAN framework designed for the challenging task of face unmasking. The method integrates binary mask priors from a pretrained M-Seg module with a CARU2-Net generator—an enhanced U2-Net architecture augmented with channel attention—and a spectral CNN discriminator. This design enables the precise localization of occluded regions and the faithful restoration of missing facial structures. Comprehensive experiments on a synthetic dataset derived from CelebA demonstrated that M2UNet consistently outperforms state-of-the-art inpainting and unmasking approaches, both quantitatively and qualitatively. Ablation studies further validated the complementary benefits of segmentation guidance, channel attention, and generator depth in achieving high-fidelity reconstructions.

Despite the promising results achieved on the synthetically masked CelebA dataset, we acknowledge certain limitations regarding generalization to real-world scenarios. Synthetic masks, while useful for quantitative evaluation where ground truth is required, often lack the physical complexities of real-world environments, such as irregular lighting, shadows cast by the mask on the skin, fabric breathability deformations, and elastic strap indentations. Consequently, a domain gap may exist when deploying the model in unconstrained, in-the-wild settings. Future work will focus on addressing this challenge by collecting and testing on a dataset of real-world masked faces to better benchmark performance in practical applications. Additionally, we plan to explore unsupervised or semi-supervised domain adaptation techniques to bridge the gap between synthetic training and real-world deployment, improving the model’s robustness against complex lighting and textural variations. Furthermore, we aim to investigate the integration of diffusion-based priors into the M2UNet framework to further enhance the generation of high-frequency details in cases of extreme occlusion.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M. and M.S.K.; methodology, M.M., M.S.K. and M.A.; software, M.M., M.F.S. and M.A.; validation, M.M. and H.-S.K.; formal analysis, M.M. and M.F.S.; investigation, H.-S.K.; resources, H.-S.K.; data curation, M.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.; writing—review and editing, M.M. and H.-S.K.; visualization, H.-S.K.; supervision, H.-S.K.; project administration, H.-S.K.; funding acquisition, H.-S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was partly supported by Innovative Human Resource Development for Local Intellectualization program through the Institute of Information & Communications Technology Planning & Evaluation(IITP) grant funded by the Korea government(MSIT) (IITP-2026-RS-2020-II201462, 50%), and partly by the Regional Innovation System & Education(RISE) program through the (Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center), funded by the Ministry of Education(MOE) and the (Chungcheongbuk-do), Republic of Korea: (2025-RISE-11-014-03).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| M2UNet | Masked-to-Unmasked Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| GAN | Generative Adversarial Network |

| M-Seg | Mask Segmentation |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index |

| FID | Fréchet Inception Distance |

| LPIPS | Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity |

| CAR | Conv-Attention Residual Block |

| CARU | Conv-Attention Residual U-blocks |

| CBAM | Convolutional Block Attention Module |

| SOTA | State-of-the-Art |

References

- Din, N.U.; Javed, K.; Bae, S.; Yi, J. A novel GAN-based network for unmasking of masked face. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 44276–44287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.; Kasem, M.S.; Kang, H.S. A comprehensive survey of masked faces: Recognition, detection, and unmasking. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.05900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorov, R.; Logacheva, E.; Mashikhin, A.; Remizova, A.; Ashukha, A.; Silvestrov, A.; Kong, N.; Goka, H.; Park, K.; Lempitsky, V. Resolution-robust large mask inpainting with fourier convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2022; pp. 2149–2159. [Google Scholar]

- Senussi, M.F.; Abdalla, M.; Kasem, M.S.; Mahmoud, M.; Yagoub, B.; Kang, H.S. A Comprehensive Review on Light Field Occlusion Removal: Trends, Challenges, and Future Directions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 42472–42493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Cham, T.J.; Cai, J. Pluralistic free-form image completion. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 2786–2805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Lin, Z.; Yang, J.; Shen, X.; Lu, X.; Huang, T.S. Free-form image inpainting with gated convolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 4471–4480. [Google Scholar]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q.; Yan, B.; Li, J.; Tan, W. Mmfl: Multimodal fusion learning for text-guided image inpainting. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 1094–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichol, A.; Dhariwal, P.; Ramesh, A.; Shyam, P.; Mishkin, P.; McGrew, B.; Sutskever, I.; Chen, M. Glide: Towards photorealistic image generation and editing with text-guided diffusion models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.10741. [Google Scholar]

- Jassim, F.A. Image inpainting by Kriging interpolation technique. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1306.0139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsalamah, M.; Amin, S. Medical image inpainting with RBF interpolation technique. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2016, 7, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Criminisi, A.; Pérez, P.; Toyama, K. Region filling and object removal by exemplar-based image inpainting. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 1200–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, C.; Shechtman, E.; Finkelstein, A.; Goldman, D.B. PatchMatch: A randomized correspondence algorithm for structural image editing. ACM Trans. Graph. 2009, 28, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Musialski, P.; Wonka, P.; Ye, J. Tensor completion for estimating missing values in visual data. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2012, 35, 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simakov, D.; Caspi, Y.; Shechtman, E.; Irani, M. Summarizing visual data using bidirectional similarity. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Anchorage, AK, USA, 23–28 June 2008; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darabi, S.; Shechtman, E.; Barnes, C.; Goldman, D.B.; Sen, P. Image melding: Combining inconsistent images using patch-based synthesis. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2012, 31, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertalmio, M.; Sapiro, G.; Caselles, V.; Ballester, C. Image inpainting. In Proceedings of the 27th Annual Conference on Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–28 July 2000; pp. 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biradar, R.L.; Kohir, V.V. A novel image inpainting technique based on median diffusion. Sadhana 2013, 38, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasath, V.S.; Thanh, D.N.; Hai, N.H.; Cuong, N.X. Image restoration with total variation and iterative regularization parameter estimation. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Information and Communication Technology, Nha Trang, Vietnam, 7–8 December 2017; pp. 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iizuka, S.; Simo-Serra, E.; Ishikawa, H. Globally and locally consistent image completion. ACM Trans. Graph. (ToG) 2017, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Z.; Zhao, L.; Li, A.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xing, W.; Lu, D. Generative image inpainting with segmentation confusion adversarial training and contrastive learning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Washington, DC, USA, 7–14 February 2023; The Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Volume 37, pp. 3888–3896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gong, M.; Tang, Z.; Qin, A.K.; Li, H.; Jiang, F. Deep image inpainting with enhanced normalization and contextual attention. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 32, 6599–6614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhan, F.; Wu, R.; Pan, J.; Cui, K.; Lu, S.; Ma, F.; Xie, X.; Miao, C. Diverse image inpainting with bidirectional and autoregressive transformers. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Chengdu, China, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, K.; Qi, L.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J. Mat: Mask-aware transformer for large hole image inpainting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 10758–10768. [Google Scholar]

- Lugmayr, A.; Danelljan, M.; Romero, A.; Yu, F.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. Repaint: Inpainting using denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11461–11471. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Qian, B.; Wang, M.; Rui, Y. Structure matters: Tackling the semantic discrepancy in diffusion models for image inpainting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 8038–8047. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, D.; Wu, J.; Luo, X.; Jin, Z. Learning from text: A multimodal face inpainting network for irregular holes. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 7484–7497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazeri, K.; Ng, E.; Joseph, T.; Qureshi, F.; Ebrahimi, M. Edgeconnect: Structure guided image inpainting using edge prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Guo, X. Generative landmark guided face inpainting. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV), Nanjing, China, 16–18 October 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Yang, J.; Yang, M.H. Generative face completion. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3911–3919. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoud, M.; Kang, H.S. Ganmasker: A two-stage generative adversarial network for high-quality face mask removal. Sensors 2023, 23, 7094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anwar, A.; Raychowdhury, A. Masked face recognition for secure authentication. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.11104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Luo, P.; Wang, X.; Tang, X. Deep learning face attributes in the wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pathak, D.; Krahenbuhl, P.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Efros, A.A. Context encoders: Feature learning by inpainting. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2536–2544. [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, R.A.; Chen, C.; Yian Lim, T.; Schwing, A.G.; Hasegawa-Johnson, M.; Do, M.N. Semantic image inpainting with deep generative models. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 5485–5493. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Reda, F.A.; Shih, K.J.; Wang, T.C.; Tao, A.; Catanzaro, B. Image inpainting for irregular holes using partial convolutions. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 85–100. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Liu, D.; Xiong, Z. E2I: Generative inpainting from edge to image. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2020, 31, 1308–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Liao, J. High-fidelity pluralistic image completion with transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 4692–4701. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Rui, Y. Delving globally into texture and structure for image inpainting. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Lisbon, Portugal, 10–14 October 2022; pp. 1270–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Ji, J.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, M.; Jaakkola, T.; Chang, S. Towards coherent image inpainting using denoising diffusion implicit models. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning, Honolulu, HI, USA, 23–29 July 2023; pp. 41164–41193. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Chen, Q.; Hu, B.; Jiang, S. Text-guided neural image inpainting. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 1302–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Zhan, D.; Qi, H.; Jin, Z. When face completion meets irregular holes: An attributes guided deep inpainting network. In Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Chengdu, China, 20–24 October 2021; pp. 3202–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Park, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Kweon, I.S. Cbam: Convolutional block attention module. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, X.; Li, Q.; Xie, H.; Lau, R.Y.; Wang, Z.; Paul Smolley, S. Least squares generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2794–2802. [Google Scholar]

- Miyato, T.; Kataoka, T.; Koyama, M.; Yoshida, Y. Spectral normalization for generative adversarial networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.05957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2019, 32, 8024–8035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A method for stochastic optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Bovik, A.C.; Sheikh, H.R.; Simoncelli, E.P. Image quality assessment: From error visibility to structural similarity. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2004, 13, 600–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. Gans trained by a two time-scale update rule converge to a local nash equilibrium. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2017, 30, 6626–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.