Abstract

Manual pill identification is often inefficient and error-prone due to the large variety of medications and frequent visual similarity among pills, leading to misuse or dispensing errors. These challenges are exacerbated when pill imprints are engraved, curved, or irregularly arranged, conditions under which conventional optical character recognition (OCR)-based methods degrade significantly. To address this problem, we propose GO-PILL, a geometry-aware OCR pipeline for robust pill imprint recognition. The framework extracts text centerlines and imprint regions using the TextSnake algorithm. During imprint refinement, background noise is suppressed and contrast is enhanced to improve the visibility of embossed and debossed imprints. The imprint localization and alignment stage then rectifies curved or obliquely oriented text into a linear representation, producing geometrically normalized inputs suitable for OCR decoding. The refined imprints are processed by a multimodal OCR module that integrates a non-autoregressive language–vision fusion architecture for accurate character-level recognition. Experiments on a pill image dataset from the U.S. National Library of Medicine show that GO-PILL achieves an F1-score of 81.83% under set-based evaluation and a Top-10 pill identification accuracy of 76.52% in a simulated clinical scenario. GO-PILL consistently outperforms existing methods under challenging imprint conditions, demonstrating strong robustness and practical feasibility.

MSC:

68T07

1. Introduction

Medication errors remain a critical global health concern, posing serious risks to patient safety and clinical outcomes. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 1.3 million patients in the United States alone experience preventable medication errors each year [1,2]. Older adults are particularly vulnerable due to the high prevalence of polypharmacy, which increases the likelihood of adverse drug reactions, drug–drug interactions, and confusion among visually similar medications. Consequently, accurate and reliable drug identification has become a fundamental requirement in safe clinical practice. In recognition of this need, the WHO has identified the development of robust drug identification systems capable of distinguishing visually similar pills as a global health priority [3].

Medication errors frequently occur during the prescription, dispensing, and administration stages, where healthcare professionals must identify medications rapidly and accurately under time constraints and visually challenging conditions. To mitigate these risks, automated pill identification systems have attracted increasing attention and can generally be categorized into shape-based and imprint-based approaches [4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. Shape-based methods rely primarily on visual attributes such as pill shape, color, and size. However, their discriminative capability is inherently limited when different medications share similar physical characteristics—a common situation in real-world clinical environments, where regulatory standards and manufacturing practices often result in overlapping pill designs.

To overcome these limitations, imprint-based approaches have been developed to directly exploit engraved characters or symbols on pill surfaces. Such imprints typically encode drug-specific information, including active ingredients, dosage strength, and manufacturer identifiers, making them more effective for distinguishing visually similar medications. Nevertheless, the performance of imprint-based methods is often compromised by background interference, inconsistent illumination, and degradation of the imprinted text due to wear, embossing, or poor imaging conditions. Moreover, many existing approaches rely heavily on pretrained classification models, which tend to exhibit reduced generalization performance when encountering newly introduced imprint designs or subtle variations in existing ones.

With recent advances in deep learning and computer vision, optical character recognition (OCR)-based approaches have emerged as a promising alternative for pill identification. By directly extracting imprint text at the character level, OCR-based methods can significantly enhance discriminative accuracy. However, conventional OCR models still face substantial challenges when dealing with embossed or low-contrast imprints, where text and background textures are visually similar. In addition, many OCR architectures assume a linear and horizontally aligned text layout, rendering them ill-suited for curved, slanted, or irregular imprint arrangements that are commonly observed on pill surfaces.

To address these challenges, we propose GO-PILL, a geometry-aware OCR pipeline specifically designed for robust pill imprint recognition under real-world imaging conditions. The proposed framework aims to maintain high recognition accuracy even in the presence of embossing, curvature, surface reflectance, and low contrast. GO-PILL comprises three sequential stages. The first stage, imprint refinement (IR), employs TextSnake-based centerline extraction [11] to accurately isolate imprint regions while enhancing contrast and suppressing background noise. This stage improves the perceptual clarity of imprints that are otherwise difficult to distinguish from the pill surface. The second stage, imprint localization and rectification (ILR), addresses geometric distortions by transforming curved or obliquely oriented text into rectified, linear representations. By providing geometrically normalized inputs, ILR improves the robustness and accuracy of subsequent OCR processing. In the final stage, the refined and rectified imprints are processed using a multimodal OCR (MMOCR) framework [12] with an ABINet-based recognizer [13], which integrates visual and language modeling to achieve accurate character-level recognition.

The proposed GO-PILL framework is evaluated using pill images from the United States National Library of Medicine (NLM) dataset [14]. Experimental results demonstrate that GO-PILL consistently outperforms existing methods across key evaluation metrics, including precision, recall, and F1-score. Notably, the proposed approach exhibits stable and reliable performance in challenging scenarios involving embossed imprints, low illumination, weak contrast, and irregular text layouts, highlighting its suitability for deployment in practical clinical environments.

The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- We propose a geometry-aware IR-ILR framework that explicitly models the physical morphology of pill imprints. By repurposing centerline extraction for adaptive contrast enhancement and nonlinear rectification, we bridge the structural gap between irregular pill surfaces and generic OCR engines.

- We introduce a text alignment and rectification strategy that transforms curved, diagonal, and irregular imprint arrangements into geometrically normalized representations, thereby reducing distortion and improving OCR accuracy.

- We develop a unified three-stage pipeline—comprising IR, ILR, and OCR—and demonstrate its superior robustness and consistent performance across diverse imprint conditions, validating its effectiveness for real-world clinical applications.

2. Related Works

2.1. Shape-Based Identification Methods

Shape-based pill identification methods primarily rely on macroscopic visual attributes, including pill shape, color, and size. Kwon et al. [15] employed a Mask Region-based Convolutional Neural Network (Mask R-CNN) [16] for contour segmentation and feature extraction to classify pills. Kim et al. [17] combined the You Only Look Once (YOLO) object detector [18] with CNN-based classifiers to achieve rotation-invariant pill recognition. These approaches are computationally efficient and perform well when pills exhibit distinctive structural characteristics.

However, in real-world clinical environments, many medications share nearly identical shapes and colors due to manufacturing constraints, regulatory standards, or pharmacological equivalence. As a result, shape-based features alone often lack sufficient discriminative power, substantially limiting the reliability and practical applicability of such methods for accurate pill identification.

2.2. Imprint-Based Identification Methods

Imprint-based identification methods aim to exploit drug-specific textual or symbolic information engraved on pill surfaces. Lee et al. [19] extracted imprint descriptors using the Scale-Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) [20] and multiscale Local Binary Patterns (LBP) [21], enabling similarity-based matching against reference databases. Al-Hussaeni et al. [22] enhanced pill imprints through Canny edge detection [23] and SIFT-based preprocessing prior to classification using CNN models.

Although imprint-based approaches generally provide stronger discriminative capability than shape-based methods, they remain vulnerable to practical imaging challenges. Uneven illumination, background interference, low-contrast markings, and degradation of imprints caused by wear or embossing often compromise feature extraction quality, leading to unstable or unreliable identification performance.

2.3. OCR-Based Imprint Recognition

OCR-based approaches aim to directly interpret engraved or printed characters on pill surfaces, enabling fine-grained differentiation among visually similar medications. Ponte et al. [24] converted pill images from the RGB color space to HSV to facilitate background suppression and applied PaddleOCR [25] for text recognition. Suntronsuk et al. [26] employed convolutional filtering with Otsu thresholding [27] for image binarization, followed by text extraction using Tesseract OCR [28]. Heo et al. [29] detected text regions using YOLOv5 and refined recognition through a recurrent neural network–based post-processing module, while Dhivya et al. [30] incorporated support vector machine classification [31] combined with n-gram–based post-correction.

While recent deep OCR architectures such as Vision Transformers (e.g., TrOCR [32]) have shown remarkable performance on scene text, they still struggle with the geometric distortions inherent in pill imprints without specialized rectification. This motivates our focus on a pipeline that prioritizes geometric normalization before character recognition.

Despite these advances, most conventional OCR frameworks assume straight, horizontally aligned text layouts. This assumption is frequently violated on real pill surfaces, where imprints are often curved, embossed, irregularly spaced, or partially deformed. To improve recognition performance for such complex forms, recent studies have increasingly shifted beyond simple sequence modeling to explicitly utilize geometric information, such as spatial relationships and morphological structures. For instance, Aluri et al. [33] integrated U-Net-based [34] component extraction with graph convolutional networks [35] to model inter-character adjacency, thereby preserving text continuity in irregular layouts. Similarly, Hu et al. [36] achieved robust recognition in complex scene text using a shape-driven alignment strategy that incorporates geometric priors derived from character shapes.

While these geometry-aware approaches have advanced general scene text recognition, their effectiveness is often limited in pill-specific environments characterized by extreme curvature and low-contrast embossed textures. Under such conditions, OCR performance deteriorates significantly, underscoring the necessity for geometry-aware OCR approaches—such as the method proposed in this study—that explicitly account for geometric distortions in pill imprints.

3. Methodology

Text recognition–based pill identification systems typically involve two main stages: detection of imprint regions within pill images, followed by text extraction using OCR. However, such conventional pipelines suffer from two fundamental limitations. First, when imprints are debossed or engraved into the pill surface, variations in illumination, surface reflections, and texture similarities between characters and background often obscure text boundaries, substantially degrading visibility and recognition accuracy. Second, most OCR algorithms assume that text appears in straight, horizontally aligned sequences. As a result, they perform poorly when handling curved, slanted, or irregular imprint layouts, which are frequently encountered on real pill surfaces.

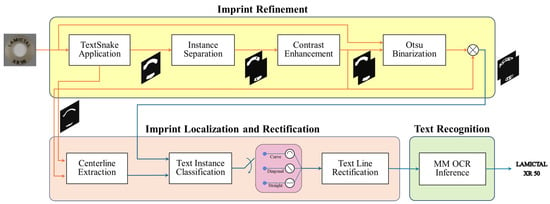

To overcome these challenges, we propose GO-PILL, a geometry-aware OCR pipeline specifically designed for robust pill imprint recognition under realistic imaging conditions. GO-PILL comprises three sequential stages: IR, ILR, and OCR-based text recognition. The overall architecture of the proposed pipeline is illustrated in Figure 1. Each block in the figure represents a critical functional transition, further detailed in the subsequent subsections.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed GO-PILL pipeline, consisting of IR, ILR, and OCR stages.

3.1. Imprint Refinement

Debossed pill imprints often exhibit indistinct boundaries between text and background due to factors such as surface material, curvature, and non-uniform lighting. These effects severely compromise the performance of OCR-based recognition. Previous studies have attempted to address this issue using image processing techniques such as contour enhancement and high-frequency filtering. However, these methods frequently amplify background textures along with the text, leading to increased false positives (FPs). To mitigate this problem, we introduce a preprocessing strategy that combines precise text-region extraction based on text centerlines with selective contrast enhancement. This approach suppresses background interference while enhancing text visibility, producing refined images that are well suited for OCR input.

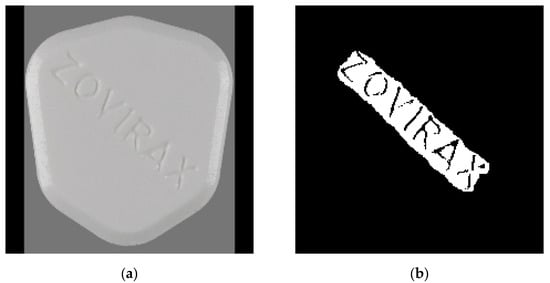

3.1.1. TextSnake-Based Text-Region Extraction

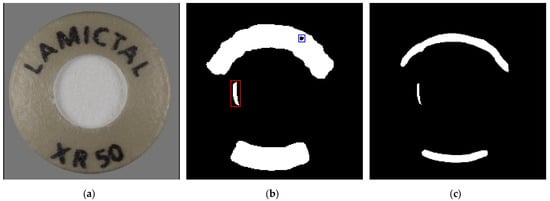

In the first stage of IR, the TextSnake algorithm proposed by Long et al. [11] is employed to detect diverse text arrangements. TextSnake represents text as a sequence of centerlines augmented with local geometric descriptors, enabling flexible reconstruction of curved or irregularly shaped text. Given an input image , TextSnake generates two binary masks. The first is the text centerline mask, , which captures the central axis of the text and is used to estimate text flow and orientation. The second is the text-region mask, , which encompasses the full character area and serves as the primary input for subsequent OCR processing.

For each pixel along the centerline, TextSnake predicts its location , orientation, and radius , and constructs a circular disk centered at with radius , defined as

The complete text region is obtained by taking the union of all such disks and is expressed as , where denotes the number of valid disks along the centerline. The continuous aggregation of these disks reconstructs the overall text structure, effectively representing curved and irregular text layouts. This formulation enables accurate extraction of text regions while minimizing background interference. Figure 2 illustrates examples of the extracted text centerline and text-region masks. As shown in Figure 2b, the text-region mask may contain FPs, where background textures or reflections are incorrectly identified as text due to visual similarity. These regions are highlighted by red boxes. In addition, discontinuities caused by small gaps within characters or image degradation can be observed in both the centerline and region masks, appearing as missing areas indicated by blue boxes.

Figure 2.

Examples of text centerline and region masks: (a) input image ; (b) text-region mask ; (c) centerline mask .

Because pill images may contain multiple text instances, connected component analysis is applied to the text-region mask to isolate individual text blocks. Each connected component is treated as an independent text instance. Area-based filtering is then performed to remove spurious detections with excessively small regions, which are likely to correspond to background noise. The resulting binary mask generated for each selected instance is defined as follows:

Here, denotes a set of pixels comprising the -th text instance, represents the area of the block (i.e., the number of pixels), and is the minimum area threshold set to remove FP detections.

3.1.2. Morphological Contrast Enhancement

Within extracted text blocks, hole-like defects may arise due to complex character shapes, uneven illumination, or image noise. Such defects can introduce structural distortions during subsequent text centerline extraction and geometric alignment, ultimately reducing OCR accuracy. To alleviate these issues, morphological closing operations are applied to each binary mask to fill internal gaps and restore text blocks into more continuous and stable shapes. The operation is defined as

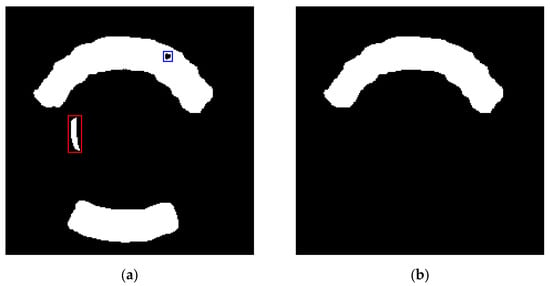

where denotes a structural kernel, represents the dilation operation, and denotes the erosion operation. Figure 3 shows a comparison of the text-region masks before and after applying the morphological closing operation. After processing, each text instance exhibits smoother outer boundaries, and internal gaps within characters are effectively filled. These refined masks significantly improve the robustness of subsequent centerline extraction and geometric alignment.

Figure 3.

Visual comparison of text region masks before and after morphological closing: (a) raw mask exhibiting internal hole noise and discontinuities; (b) refined mask with restored character integrity and filled gaps.

3.1.3. Localized Otsu Binarization

The refined mask contains predominantly zero-valued pixels. When directly multiplied with the full input image III, this imbalance introduces substantial histogram distortion during Otsu threshold computation, as the large background area dominates the intensity distribution. To address this issue, a minimum bounding rectangle is constructed for each text instance by determining the extreme top, bottom, left, and right coordinates of its mask . This rectangle, denoted as , is defined as the region of interest (ROI) for each individual text instance. Using this ROI, a localized image is extracted as , which contains only the pixels relevant to the corresponding imprint.

Otsu thresholding is then applied independently to each localized region, preventing interference from large background areas and enabling clearer separation between text and background. The binarized result for each instance is defined as

where denotes the pixel threshold that maximizes the between-class variance:

Here, and denote the class probabilities of background and text pixels, respectively, and and represent their corresponding mean intensities. The Otsu algorithm selects a threshold that maximizes the between-class variance, thereby achieving optimal separation. In this study, Otsu binarization is performed on a per-instance basis rather than on the entire image. This localized strategy effectively avoids histogram distortion and preserves fine text structures, even under low-contrast or engraved conditions.

After thresholding, a logical AND operation is performed between the refined mask and the Otsu output , producing the final binary test image . This step removes residual background noise while preserving sharp character boundaries, yielding a binarized imprint optimized for OCR processing.

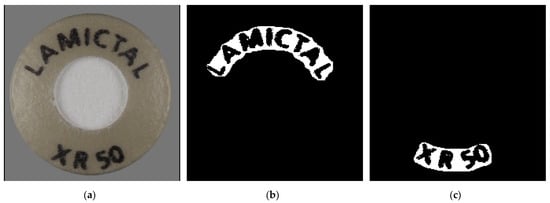

Figure 4 shows two embossed text instances extracted from a single pill image. Figure 4a presents the original image, while Figure 4b,c display the final binarized text images for the first and second instances, respectively. The proposed refinement successfully eliminates background interference and clearly delineates embossed character boundaries.

Figure 4.

Refinement results of embossed imprint text: (a) original image; (b) binary text image of the first text instance, (c) binary text image of the second text instance.

Figure 5 illustrates the refinement process for a debossed imprint. Although the original image in Figure 5a exhibits faint, low-contrast boundaries due to the concave imprint structure, the refined result in Figure 5b demonstrates a clear separation between text and background. This confirms that the proposed preprocessing provides sufficient visibility and structural clarity for reliable OCR.

Figure 5.

Refinement results of debossed imprint text: (a) original image; (b) binary text image generated after preprocessing.

3.2. Imprint Localization and Rectification

Most conventional text recognition systems rely on OCR algorithms that assume characters are arranged in straight, horizontally aligned sequences. In real clinical imaging scenarios, however, pill imprints frequently exhibit curved, diagonal, or otherwise irregular geometric patterns arising from pill surface curvature, manufacturing variability, and imaging perspectives. These geometric distortions violate the assumptions underlying standard OCR models and consequently result in substantial degradation in recognition accuracy. To address this limitation, the proposed GO-PILL framework incorporates an ILR module. ILR explicitly analyzes the geometric configuration of each detected text instance and transforms it into a rectified, linear representation suitable for OCR processing. By correcting spatial distortions and enforcing consistent geometric alignment, ILR significantly enhances the robustness and reliability of subsequent text recognition.

3.2.1. Centerline Refinement

The ILR process begins with refinement of the centerline representation for each text instance. Specifically, a logical AND operation is applied between the global text centerline mask , generated in the IR stage, and the corresponding instance-specific refined mask . This operation suppresses residual background responses and produces a refined centerline mask . The resulting refined centerline accurately preserves the spatial trajectory of the -th text instance, providing a clean and continuous representation of its geometric layout. This information forms the basis for subsequent alignment and rectification operations and is particularly critical for modeling curvature in imprints that deviate from linear text arrangements.

3.2.2. Text Instance Classification

To select an appropriate geometric transformation for alignment, each binary text mask is classified into one of three structural categories: linear , curved , or diagonal . This classification is performed in two stages. During first-stage preliminary filtering, if the number of centerline points N falls below a threshold , or if the area of the centerline mask is smaller than a threshold , reliable geometric analysis is not feasible. In such cases, the text instance is conservatively classified as linear :

For text instances that pass the initial filtering, a slope-based analysis is performed on the ordered centerline points. The following metrics are computed: the mean slope angle , the slope variation (standard deviation) , the overall slope threshold , and the number of centerline points . Based on these metrics, the text instance is classified accordingly:

Here, and denote the mean angle and angle variation thresholds used to identify curved text, respectively, while specifies the minimum number of centerline points required for curved classification. Similarly, and define the allowable range of mean angles for diagonal classification, whereas and correspond to the slope and variation thresholds, respectively; indicates the minimum number of centerline points required for diagonal classification. Text instances that do not satisfy any of these criteria are classified as linear text by default.

This centerline-based classification enables accurate categorization of imprint geometries and guides the selection of an optimal rectification strategy for subsequent alignment.

3.2.3. Text Line Rectification

For text instances classified as curved or diagonal , a geometric rectification procedure is required to transform the text into a linear, OCR-compatible representation. In particular, curved text cannot be reliably rectified using simple projection-based approaches, as these methods introduce shape distortions, especially near segment boundaries. To overcome this limitation, the centerline is reconstructed using cubic spline interpolation. For each segment , the spline function is defined as

where the coefficients , , , and ensure continuity of the curve and its first and second derivatives across adjacent segments. Points sampled as along the spline define the reference baseline for alignment.

To mitigate distortion at the extremities, each curved text instance is divided into two sub-blocks around its midpoint: the left sub-block and the right sub-block . For each sub-block, the straight line connecting its endpoints is used to estimate the rotation angle . In this context, denotes one of the two sub-blocks, defined as . The corresponding rotation transformation is defined as

where denotes the spline reference coordinate at the center of the cropped region, and represents the angle between the line connecting the two spline endpoints and the x-axis.

Within the rotated image , vertical slicing is performed at each x-coordinate. Let denote the centerline point at which the absolute slope is minimized. Using this point as a reference, the text is vertically shifted to align the baseline. For each x-coordinate, the upper and lower text boundaries are computed as and , respectively. The rectified text image is then obtained as

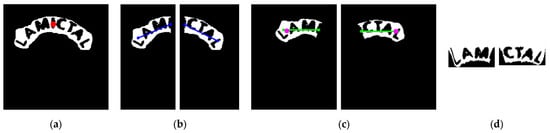

This procedure straightens the entire text instance while preserving character geometry, producing an OCR-ready representation. Figure 6 illustrates the complete curved-text rectification workflow: red dots indicate spline centerline points, the blue curve represents the original centerline, the green curve denotes the aligned centerline, and the pink dot marks the slope-minimizing reference point.

Figure 6.

Curved-text rectification process: (a) Original curved-text image; (b) Text sub-blocks after left-right splitting; (c) Rotated and translated text image for horizontal alignment; (d) Final rectified text image obtained through spline interpolation.

3.3. Text Recognition

To enable robust recognition of the refined and geometrically aligned imprint images, the GO-PILL framework employs an ABINet-based text recognition module within the MMOCR framework. This module operates through a dual-stream architecture, where visual features and linguistic context are independently extracted and subsequently integrated by a fusion module to ensure character-level robustness. The preprocessed outputs from the IR and ILR stages are directly fed into this recognizer, allowing accurate character-level recognition under challenging imaging conditions such as low contrast, embossing, and curved-text layouts.

ABINet comprises three main components: a vision model, a language model, and a fusion module. The vision model uses a ResNet-based CNN encoder to convert input text images into visual feature maps, capturing local spatial and structural character details. The language model, implemented with a transformer architecture, learns contextual dependencies between characters and generates an initial character sequence. The fusion module iteratively integrates visual and linguistic information, resolving inconsistencies and producing the final robust character prediction.

For pill imprint recognition, the ABINet model is trained on 36 character classes, including uppercase letters (A–Z) and digits (0–9), which are predominantly found in real-world pill images. The network is optimized using a composite loss function defined as

where , , and represent the vision, language, and fusion losses, respectively.

The vision loss evaluates sequence prediction accuracy based solely on visual features extracted by the CNN encoder. Given an input text image and the corresponding ground-truth sequence of length , the loss is defined as

where denotes the probability of the ground-truth sequence predicted by the vision model using connectionist temporal classification. The formulation enables sequence learning without explicit character-level alignment, enabling robust geometries. The language loss evaluates the ability of the transformer-based language model to predict each character conditioned on all preceding characters :

where represents the Softmax probability output of the language model at each decoding step. This loss ensures that the model learns contextual dependencies between characters, improving recognition when visual cues are ambiguous.

The fusion loss quantifies alignment between the final predicted sequence and the ground truth by integrating both visual and linguistic information:

where denotes the Softmax probability of the -th character produced by the fusion module. This loss enables iterative refinement of predictions, mitigating errors arising from visual distortions or irregular imprint structures. By minimizing the total loss , the network learns to accurately recover character sequences from pill imprints despite visual distortions, curved layouts, debossing, or partial occlusions. This design ensures reliable OCR performance across diverse and irregular imprint patterns, reinforcing the effectiveness of the GO-PILL framework for real-world clinical applications.

4. Experimental Results

This section presents a comprehensive empirical evaluation of the proposed GO-PILL framework on complex pill imprint patterns exhibiting diverse geometric characteristics, including curved, diagonal, embossed, and debossed imprints. The experiments compare three categories of methods:

- (1)

- Baseline OCR, which applies OCR directly to raw images;

- (2)

- Non-OCR approaches, which rely on detection or classification rather than text decoding; and

- (3)

- Preprocessed OCR, which incorporates the proposed IR and ILR modules prior to OCR.

All evaluations were conducted on the NLM pill image dataset [14], which includes realistic imaging challenges covering a vast range of FDA-approved medications from various pharmaceutical manufacturers, ensuring that the imprint styles (font types, debossing depths, and logos) reflect those found in global clinical practice.

4.1. Experimental Setup

All experiments were performed on a workstation equipped with an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU and an Intel Core i7-12700 CPU. The dataset comprises 2032 pill images with visible imprints, divided into a training set of 1427 images and a test set of 605 images, corresponding to an approximate 7:3 split. The training set contains 330 embossed and 1097 debossed imprints, with 131 curved, 2 diagonal, and 1294 linear text arrangements. The test set includes 44 embossed and 561 debossed imprints, with 143 curved, 164 diagonal, and 298 linear arrangements. This data partitioning ensures that no imprint appears in both sets, enabling an unbiased evaluation of generalization to unseen imprint structures. Consequently, we effectively evaluate the model’s zero-shot generalization capability to previously unseen pharmaceutical markings, reflecting real-world clinical scenarios where new drug formulations are continuously introduced.

All images were pre-cropped to pill boundaries and resized to 224 × 224 pixels. Recognition performance was evaluated using a set-based metric, in which character order is disregarded. A character present in both the predicted and ground-truth sets is counted as a true positive (TP), a predicted but absent character is considered an FP, and a missing ground-truth character is treated as a false negative (FN). Precision, recall, and F1-score were computed using standard definitions. This evaluation protocol is particularly appropriate for imprint elements such as manufacturer names or brand identifiers, where the relative order of characters is often non-critical. Performance is quantified by Precision (TP/(TP + FP)), Recall (TP/(TP + FN)), and F1-score (2 × Precision × Recall/(Precision + Recall)), providing a balanced assessment of accuracy and completeness.

The key hyperparameters of the IR and ILR modules were determined through preliminary experiments. Table 1 summarizes the optimized thresholds used for text-region filtering, centerline extraction, and geometric classification. These values were empirically determined via sensitivity tests to ensure robust performance across various pill morphologies. For instance, the minimum text region area was set to effectively filter out small texture-induced noise while preserving fragmented character strokes. Similarly, the angular variance threshold for curved text ensures precise differentiation between naturally curved imprints and slight misalignments in linear text. These optimized parameters serve as a standardized configuration for all subsequent evaluations on the NLM dataset.

Table 1.

Key parameters and optimized thresholds of the GO-PILL pipeline.

4.2. Ablation Study

An ablation study was conducted to assess the individual and combined contributions of the proposed IR and ILR modules. As detailed in Table 2, the recognition performance—measured by precision, recall, and F1-score—highlights the architectural necessity of the GO-PILL pipeline; neither IR nor ILR alone is sufficient. Their synergy suggests that the proposed integration is a non-trivial coupling designed to handle the specific noise-to-geometry transition in pill imprints.

Table 2.

Performance comparison of individual and integrated IR and ILR modules [%].

When applied directly to raw RGB images, the baseline OCR system achieves an F1-score of 72.97%, as it does not address geometric distortions or contrast variations. Applying the IR module alone results in a reduced F1-score of 51.30%, because geometric distortions—such as curved or diagonal text—remain uncorrected, leading to misaligned OCR predictions despite improved text visibility. Similarly, ILR alone yields a lower F1-score of 42.49%, as residual noise and hole artifacts in the extracted text regions impede reliable centerline estimation and geometric rectification.

The IR module mitigates these issues by suppressing false-positive noise through thresholding and filling holes using morphological operations, thereby producing structurally coherent text regions suitable for ILR processing. When IR and ILR are jointly applied, both precision and recall increase substantially, resulting in an F1-score of 81.83%, representing an improvement of approximately 9% over the baseline OCR. These results confirm that the integrated pipeline effectively addresses challenges arising from curved, diagonal, and low-contrast imprints that typically degrade OCR performance.

The significant performance gap observed between the ‘IR-only’ and ‘IR+ILR’ configurations proves that visual enhancement alone is insufficient for pill imprints. ILR is indispensable for rectifying the physical curvature of the medication surface, which standard OCR decoders are not designed to perceive.

To further analyze the impact of binarization on debossed imprint enhancement, Table 3 compares three thresholding techniques.

Table 3.

Performance evaluation according to binarization methods [%].

Adaptive Gaussian and Sauvola thresholding reduce texture-induced noise but inadequately enhance shallow or low-contrast debossed imprints, leading to information loss. In contrast, the localized Otsu-based binarization adopted in GO-PILL slightly increases background noise but significantly improves the visibility of faint imprints, yielding the highest recognition accuracy. These findings underscore the importance of the IR module in generating contrast-enhanced, well-defined text regions for reliable geometric rectification and OCR.

Furthermore, to validate the statistical reliability of the proposed system, we conducted five independent trials for the GO-PILL pipeline. The results showed remarkably consistent performance, yielding a mean F1-score of 81.83% with a low standard deviation of 0.56. Similar levels of stability were observed for Precision and Recall (std < 0.6), confirming that the proposed geometry-aware approach provides stable and reproducible recognition accuracy, which is a critical requirement for automated pill identification in practical clinical environments.

4.3. Comparative Evaluation

To evaluate the practical applicability of GO-PILL, comparative experiments were conducted using both a set-based imprint recognition task and a Top-N pill identification task. In the set-based evaluation, predicted characters were compared with ground-truth characters regardless of sequence. The resulting recognition outputs were then integrated with visual attributes such as pill shape and color to form comprehensive query descriptors. Candidate pills were ranked based on similarity scores, and Top-N accuracy, defined as the probability of retrieving the correct pill within the top N candidates, was used as the primary metric for assessing clinical usability.

Table 4 presents a detailed comparison of set-based imprint recognition performance across baseline OCR, non-OCR, preprocessed OCR methods, and GO-PILL. Baseline OCR models exhibit notable performance degradation when handling curved, diagonal, or low-contrast debossed imprints. Among them, MMOCR [12] achieves the highest F1-score, owing to its iterative vision–language fusion mechanism, which partially compensates for missing or distorted characters.

Non-OCR approaches, including YOLOv11 [39] and the method proposed by Heo et al. [29], demonstrate limited robustness under complex imprint geometries. YOLOv11, in particular, struggles to discriminate between morphologically similar characters (e.g., “O” vs. “0” and “S” vs. “5”). The method of Heo et al. [29], which relies on YOLOv5 detection followed by RNN-based post-processing, is prone to misinterpreting background textures as imprints, leading to alignment instability. While preprocessed OCR approaches such as Ponte et al. [24] benefit from background separation and contrast enhancement, they remain vulnerable to geometric distortions and challenging debossed text conditions.

In contrast, GO-PILL consistently outperforms all competing methods across all imprint types. The IR module enhances both embossed and debossed imprints by improving local contrast and suppressing background artifacts, while the ILR module rectifies curved and diagonal layouts into linear sequences compatible with OCR. This integration yields substantial gains in both precision and recall, resulting in the highest overall F1-score of 81.83%. GO-PILL also demonstrates strong generalization across printed, debossed, curved, diagonal, and linear imprints, highlighting its robustness under realistic clinical imaging conditions. In particular, the significant performance gap between standalone PaddleOCR and GO-PILL (81.83% vs. 54.80%) indicates that even robust industrial-grade OCR engines require specialized geometric normalization to handle the ‘non-cooperative’ surfaces of medical pills.

Table 4.

Set-based imprint recognition performance [%]. Bold values denote the best performance in each category. Set-based evaluation requires the entire character sequence on a pill to be correctly identified. GO-PILL achieves the highest overall F1-score (81.83%), showing superior robustness in curved and debossed imprints compared to baseline and non-OCR methods.

Table 4.

Set-based imprint recognition performance [%]. Bold values denote the best performance in each category. Set-based evaluation requires the entire character sequence on a pill to be correctly identified. GO-PILL achieves the highest overall F1-score (81.83%), showing superior robustness in curved and debossed imprints compared to baseline and non-OCR methods.

| Category | Recognition Model | Class Type | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline OCR | Paddle OCR [25] | All | 80.66 | 41.50 | 54.80 |

| Printed | 96.60 | 81.95 | 88.67 | ||

| Debossed | 76.68 | 35.92 | 48.93 | ||

| Curved | 71.61 | 16.83 | 27.26 | ||

| Diagonal | 80.71 | 59.11 | 68.24 | ||

| Linear | 83.72 | 57.40 | 68.11 | ||

| Easy OCR [40] | All | 81.01 | 35.36 | 49.24 | |

| Printed | 93.91 | 77.98 | 85.21 | ||

| Debossed | 77.22 | 29.52 | 42.71 | ||

| Curved | 68.04 | 19.72 | 30.58 | ||

| Diagonal | 86.21 | 46.47 | 60.39 | ||

| Linear | 85.29 | 45.56 | 59.39 | ||

| TrOCR [36] | All | 59.01 | 53.90 | 56.34 | |

| Printed | 56.56 | 49.82 | 52.98 | ||

| Debossed | 59.40 | 54.43 | 56.81 | ||

| Curved | 63.16 | 51.39 | 56.67 | ||

| Diagonal | 50.11 | 43.31 | 46.46 | ||

| Linear | 60.43 | 63.67 | 62.01 | ||

| MMOCR [12] | All | 71.88 | 74.09 | 72.97 | |

| Printed | 64.71 | 59.57 | 62.03 | ||

| Debossed | 72.48 | 75.52 | 73.97 | ||

| Curved | 50.87 | 52.69 | 51.76 | ||

| Diagonal | 83.36 | 83.83 | 83.60 | ||

| Linear | 85.76 | 85.08 | 85.42 | ||

| Non-OCR approach | YOLOv11 [39] | All | 73.14 | 66.40 | 69.61 |

| Printed | 75.57 | 60.29 | 67.07 | ||

| Debossed | 72.86 | 67.03 | 69.82 | ||

| Curved | 62.23 | 49.85 | 55.36 | ||

| Diagonal | 70.87 | 67.42 | 69.10 | ||

| Linear | 84.06 | 83.49 | 83.77 | ||

| Heo et al. [29] | All | 51.47 | 70.94 | 59.66 | |

| Printed | 72.84 | 88.09 | 79.74 | ||

| Debossed | 48.93 | 68.60 | 57.11 | ||

| Curved | 31.69 | 28.88 | 30.22 | ||

| Diagonal | 38.11 | 56.88 | 45.64 | ||

| Linear | 74.90 | 89.75 | 81.66 | ||

| Preprocessed OCR | Ponte et al. [24] | All | 80.60 | 42.54 | 55.69 |

| Printed | 92.47 | 79.78 | 85.66 | ||

| Debossed | 77.66 | 37.48 | 50.56 | ||

| Curved | 73.75 | 17.63 | 28.46 | ||

| Diagonal | 80.35 | 60.04 | 68.72 | ||

| Linear | 83.01 | 59.00 | 68.97 | ||

| GO-PILL | All | 81.93 | 81.73 | 81.83 | |

| Printed | 96.88 | 89.53 | 93.06 | ||

| Debossed | 80.05 | 80.61 | 80.33 | ||

| Curved | 63.72 | 65.44 | 64.57 | ||

| Diagonal | 87.91 | 85.13 | 86.50 | ||

| Linear | 99.19 | 98.05 | 98.62 |

Table 5 summarizes Top-N pill identification performance. MMOCR [12], used as the baseline OCR method, achieves a Top-10 accuracy of 69.62%, but its performance is limited by unstable sequence predictions and occasional over-segmentation of faint imprints. Non-OCR and preprocessed approaches—including YOLOv11 [39], Heo et al. [29], and Ponte et al. [24]—show substantially lower Top-10 accuracies, ranging from 43.14% to 62.07%, highlighting the challenges of imprint recognition under diverse imaging conditions. In contrast, GO-PILL consistently outperforms all alternatives, achieving Top-1, Top-5, and Top-10 accuracies of 46.63%, 68.80%, and 76.52%, respectively. These improvements stem from effective preservation of imprint structure through geometric rectification and robust retrieval performance despite minor character losses, demonstrating resilience to variations in illumination, background texture, and imprint geometry.

Table 5.

Top-N pill identification accuracy [%].

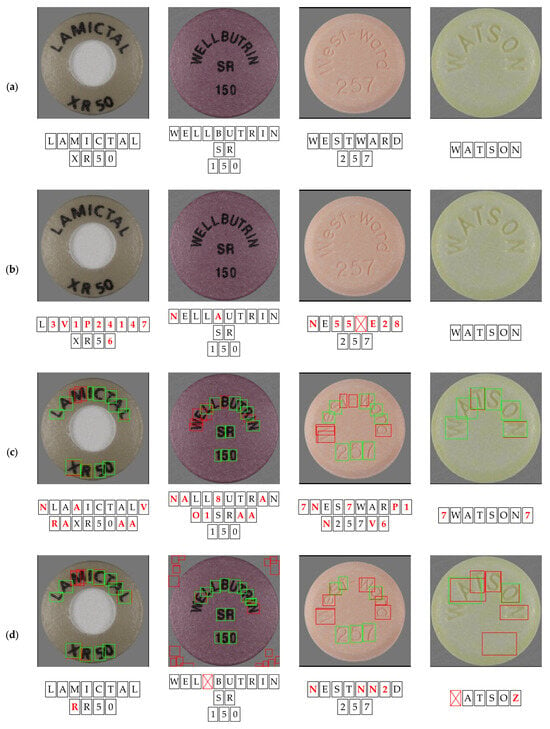

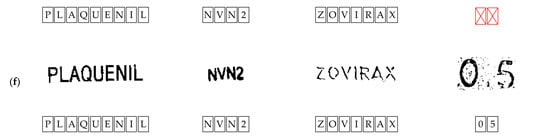

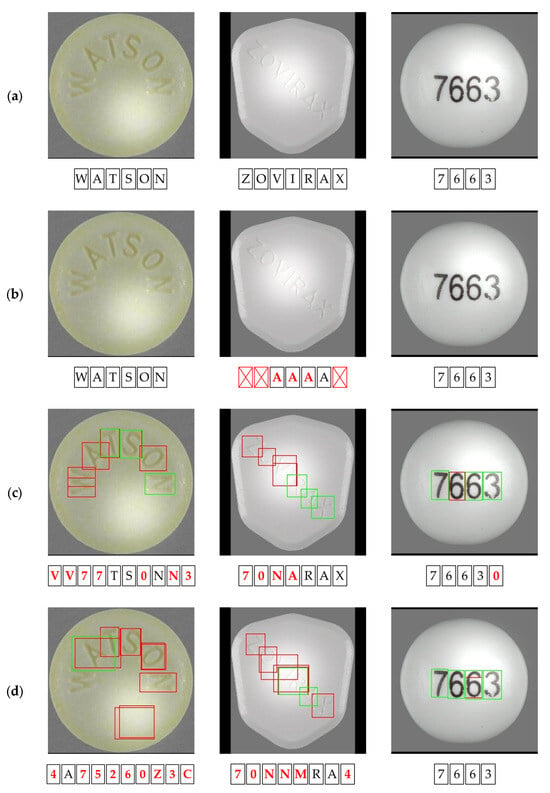

Figure 7 illustrates recognition results for curved-shaped imprints. Red boxes marked with an “X” below each image indicate missed characters, while red-colored characters denote FPs. In the detection-based visualizations, green boxes represent correct detections, and red boxes indicate FPs. As shown, existing methods (Figure 7b–e) exhibit instability when handling nonlinear text trajectories. MMOCR [12] partially mitigates these issues through its multi-stage detection and recognition pipeline but still produces fragmented or spatially shifted outputs in tightly curved regions. Specifically, because YOLOv11 [39] lacks a text-rectification mechanism, it frequently over-segments individual characters; for example, as shown in the first column of Figure 7c, the character “M” is incorrectly predicted as “AA.” Similarly, the method of Heo et al. [29] demonstrates inconsistent stroke preservation under curvature-induced distortions. Ponte et al. [24] continues to suffer from the inherent limitations of conventional OCR when applied to irregular text layouts. In particular, when multiple text regions are present on a single pill, their model often converges on a less complex region, failing to detect or recognize imprints in other areas.

Figure 7.

Recognition results for curved-shaped imprints: (a) ground truth; (b) MMOCR [12]; (c) Al-YOLOv11 [39]; (d) Heo et al. [29]; (e) Ponte et al. [24]; (f) GO-PILL. In the detection results, green boxes indicate correct detections, while red boxes represent FPs. For recognition results shown below each image, red-colored characters denote FPs, and red boxes marked with an “X” indicate FNs. Unlike baseline methods that exhibit instability in nonlinear trajectories, GO-PILL (f) improves accuracy by transforming curved structures into linear sequences via layout rectification.

In contrast, GO-PILL (Figure 7f) applies an imprint layout rectification procedure that transforms curved-text structures into linear sequences compatible with OCR decoding. This geometric normalization significantly improves recognition stability and accuracy for curved and debossed imprints, directly contributing to the superior quantitative performance reported in Table 4.

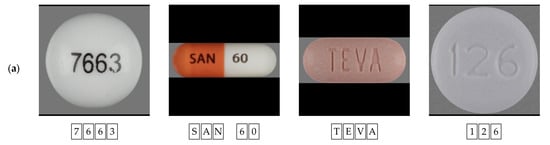

Figure 8 presents recognition results for diagonal-shaped imprints. MMOCR [12] (Figure 8b) partially compensates for moderate angular variations through its multi-stage detection pipeline; however, strong text inclination still leads to unstable character ordering and occasional boundary shifts. For YOLOv11 [34], the absence of rotation-invariant processing frequently results in misidentifications when imprints are diagonally arranged. For example, as shown in the third column of Figure 8c, a rotated “Z” is incorrectly recognized as an “N” due to orientation ambiguity. The method proposed by Heo et al. [29] (Figure 8d) reduces some errors using detection-based processing, yet residual rotational misalignment continues to distort character features. While Ponte et al. [24] (Figure 8e) demonstrate relatively stable performance for diagonal layouts, their recognition accuracy degrades substantially when diagonal orientation is combined with debossed textures, particularly as surface complexity increases.

Figure 8.

Recognition results for diagonal-shaped imprints: (a) ground truth; (b) MMOCR [12]; (c) YOLOv11 [39]; (d) Heo et al. [29]; (e) Ponte et al. [24]; (f) GO-PILL. Box/color notations are identical to Figure 7. GO-PILL (f) effectively handles rotation-induced distortions through a rotation-aware alignment strategy, whereas baseline methods (b–e) show frequent character orientation errors.

In contrast, GO-PILL (Figure 8f) employs rotation-aware alignment to generate text lines with consistent orientation and spacing. This rectification strategy enhances recognition robustness for diagonal imprints, complementing the improvements observed for curved imprints in Figure 7.

Figure 9 compares recognition results for straight-shaped imprints. Although straight text poses fewer geometric challenges, baseline methods remain sensitive to contrast variation, surface reflectance, and background texture. In particular, methods such as MMOCR [12] (Figure 9b) and Ponte et al. [24] (Figure 9e), which lack explicit mechanisms for enhancing debossed imprint contrast, perform adequately on clearly engraved linear text but often misinterpret shallow or low-contrast imprints. For instance, excessive emphasis on surface texture can cause “60” to be misidentified as “500” or missed entirely. YOLOv11 [39] (Figure 9c) frequently generates redundant detections, where internal character loops are incorrectly predicted as separate entities, such as confusing the “0” inside a “6” or mistaking “S” for “5,” highlighting the need for geometric post-processing. Meanwhile, the approach of Heo et al. [29] (Figure 9d) occasionally produces FPs from textured backgrounds, and Ponte et al. [24] (Figure 9e) struggles when foreground–background contrast is insufficient.

Figure 9.

Recognition results for straight-shaped imprints: (a) ground truth; (b) MMOCR [12]; (c) YOLOv11 [39]; (d) Heo et al. [29]; (e) Ponte et al. [24]; (f) GO-PILL. Box/color notations are identical to Figure 7. While baseline methods are sensitive to low contrast and surface reflectance, GO-PILL (f) ensures robust recognition by integrating contrast enhancement with geometric normalization.

In contrast, GO-PILL (Figure 9f) integrates contrast enhancement with precise geometric rectification, enabling stable recognition for both embossed and engraved straight imprints. This robustness is consistent with the high F1-scores reported in Table 4 and demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed pipeline even under relatively simple imprint geometries.

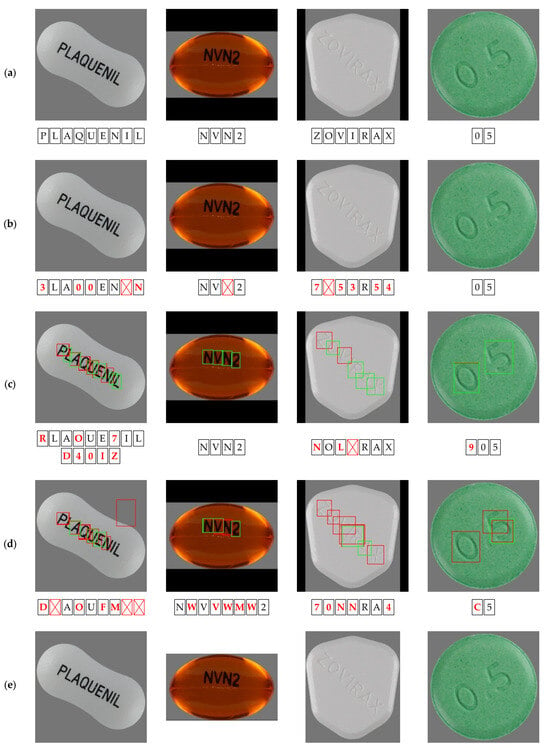

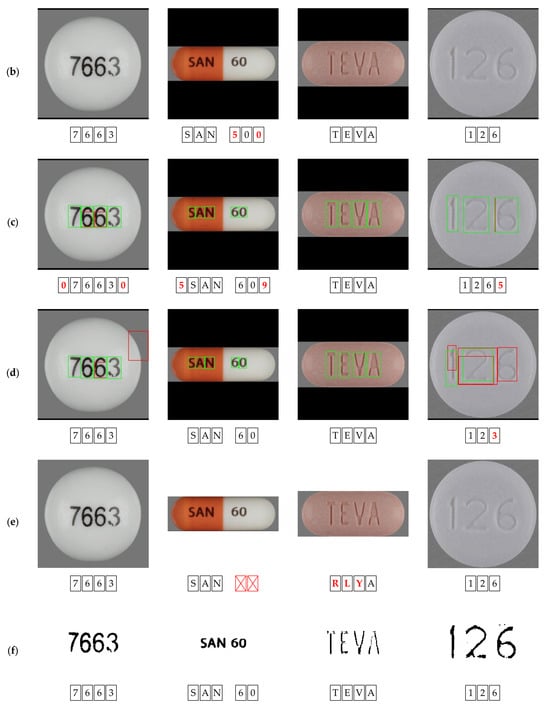

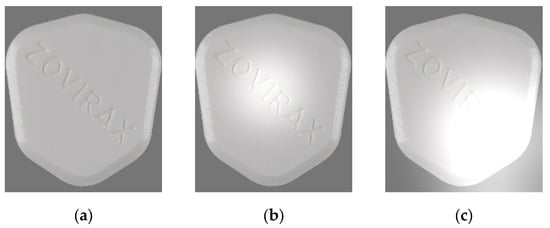

4.4. Performance Evaluation Under Glare Noise Conditions

To evaluate robustness under glare commonly observed on reflective pill surfaces, a synthetic glare model was applied to the test images, generating localized brightness-saturated regions. Glare centers were randomly positioned, and radius and intensity parameters were adjusted to simulate varying reflection patterns. Gaussian blurring was applied to emulate natural light diffusion. Figure 10 illustrates example glare conditions: Level 1 (intensity 0.3, size 0.2) represents moderate reflection, while Level 2 (intensity 0.5, size 0.3) simulates severe overexposure. As glare intensity increases, local character contrast progressively decreases, posing significant challenges for conventional OCR systems.

Figure 10.

Example images under varying glare intensity levels: (a) original image; (b) glare intensity Level 1; (c) glare intensity Level 2.

Recognition performance under varying glare intensities is summarized in Table 6. As glare intensity increases, all methods exhibit a more pronounced decline in recall than in precision, indicating partial character occlusion and localized blurring. MMOCR [12] shows moderate robustness, achieving F1-scores of 73.13% and 62.62% at glare Levels 1 and 2, respectively; however, its predictions become unstable under severe glare conditions. In contrast, GO-PILL consistently outperforms all competing methods by leveraging IR for contrast enhancement and ILR for geometric alignment, enabling reliable recognition despite glare-induced information loss. Baseline approaches, including YOLOv11 [39], Heo et al. [29], and Ponte et al. [24], exhibit substantial performance degradation, underscoring the limitations of conventional OCR- and classification-based pipelines under reflective imaging conditions.

Table 6.

Comparison of set-based imprint recognition performance under glare noise [%].

Figure 11 presents qualitative recognition results under moderate glare conditions. MMOCR [12] generally maintains consistent performance; however, predictions become unstable when glare overlaps with curved or slanted text, leading to character ordering drift (Figure 11b). For YOLOv11 [39], glare on debossed imprints reduces visual contrast, resulting in frequent misidentifications in affected regions (Figure 11c). Heo et al. [29] often misinterpret specular reflections as imprint features, causing alignment errors during RNN-based correction (Figure 11d). Ponte et al. [24] exhibit similar limitations, where glare is either mistaken for valid features or leads to misrecognition or complete omission of imprints obscured by reflections (Figure 11e). In contrast, GO-PILL (Figure 11f) accurately aligns and recognizes characters even under localized glare, demonstrating strong robustness against reflection-induced recognition failures.

Figure 11.

Recognition results under glare intensity Level 1: (a) ground truth; (b) MMOCR [12]; (c) YOLOv11 [39]; (d) Heo et al. [29]; (e) Ponte et al. [24]; (f) GO-PILL. Box/color notations are identical to Figure 7. While glare-induced loss of detail causes frequent misses and FPs in baseline methods, GO-PILL (f) maintains robust performance by utilizing contrast enhancement and layout rectification to mitigate surface reflectance.

5. Discussion

This study examined the limitations of conventional OCR-based pill imprint recognition methods, which often suffer performance degradation under low-contrast debossed engravings, curved-text layouts, and uneven illumination. To address these challenges, we proposed GO-PILL, a geometry-aware OCR framework that integrates IR and ILR to enhance robustness across diverse imprint structures.

The IR stage employs TextSnake-based centerline extraction combined with Otsu thresholding to emphasize genuine text regions while suppressing background textures, thereby improving imprint visibility for both embossed and debossed pills. The subsequent ILR stage performs geometric rectification of curved and diagonal text layouts, aligning them with the linear text assumptions underlying standard OCR models. This rectification is critical for restoring structural consistency in scenarios where baseline OCR approaches fail due to irregular text geometry.

Experimental results demonstrate that GO-PILL consistently outperforms existing OCR-based and non-OCR approaches in terms of precision, recall, and F1-score across a wide range of realistic clinical scenarios, including non-uniform illumination, varied surface materials, and complex imprint layouts. In addition, Top-N retrieval evaluations further confirm the framework’s practical utility, enabling reliable pill identification even when some characters are partially missing or distorted.

Despite these strengths, several limitations remain. Minor distortions or partial loss of central characters may occur during geometric rectification, particularly for severely degraded imprints. Extreme lighting conditions or highly reflective pill surfaces can also reduce the effectiveness of the IR module. In some shallow debossed samples with curved layouts, Otsu-based thresholding may produce overly large regions in , occasionally omitting portions of imprint segments due to insufficient contrast and interference from surface textures. These observations suggest that further improvements could be achieved through adaptive thresholding strategies or depth-aware enhancement mechanisms. Furthermore, because the proposed IR and ILR modules prioritize the structural normalization of physical imprints over semantic decoding, the GO-PILL framework remains inherently language-agnostic. This modularity allows for straightforward adaptation to multilingual pharmaceutical markets by integrating OCR backends pre-trained on diverse character sets.

Future research could explore context-aware post-processing, learning-based confidence correction, and multi-view image fusion to further enhance recognition stability under extreme conditions. Additionally, incorporating lightweight uncertainty estimation may improve reliability and interpretability in clinical decision-support systems.

In summary, GO-PILL provides a practical and robust geometry-aware solution to the persistent challenges of pill imprint recognition. Its strong generalization and high identification accuracy underscore its potential for clinical deployment, supporting medication safety and reducing human error.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we introduced GO-PILL, a geometry-aware pill imprint recognition framework designed to deliver robust performance under challenging clinical conditions, including low-contrast debossed engravings, curved or diagonal text layouts, and complex background textures. By combining IR, geometry-driven text rectification, and a sequence-attention-based OCR decoder, GO-PILL effectively overcomes the structural and visual limitations that compromise conventional OCR-based approaches.

Comprehensive experimental evaluations demonstrate that GO-PILL consistently outperforms existing OCR and non-OCR methods, achieving significant improvements in precision, recall, and F1-score across diverse imprint types. The framework also exhibits strong reliability in Top-N pill retrieval tasks, confirming its practical suitability for clinical applications such as medication verification and automated pill identification. These results underscore the potential of GO-PILL as a robust and dependable technology to enhance medication safety and reduce human error in healthcare settings.

Future work will focus on extending the framework to more challenging scenarios, including severely worn or damaged imprints, extreme illumination variations, and multi-pill images with overlapping instances. Potential enhancements, such as adaptive geometric alignment, context-aware post-recognition correction using natural language processing techniques, and multimodal fusion incorporating shape or three-dimensional surface cues, are expected to further improve robustness, scalability, and real-world applicability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.J.; Methodology, J.J.; Software, J.J.; Validation, S.Y.; Formal analysis, J.J. and S.Y.; Investigation, S.Y. and J.C.; Data curation, J.J.; Writing—original draft, J.J.; Writing—review and editing, S.Y. and J.C.; Supervision, J.C.; Project administration, J.C.; Funding acquisition, J.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MOE) (No. 2021R1I1A3055973) and the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in National Library of Medicine at https://datadiscovery.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- El Hajj, M.; Asiri, R.; Husband, A.; Todd, A. Medication errors in community pharmacies: A systematic review of the international literature. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0322392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Burden of Preventable Medication-Related Harm in Health Care: A Systematic Review; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/f208903d-b47d-4a8c-9fac-d8136c2bdbb6/content (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- World Health Organization. Medication Safety for Look-Alike, Sound-Alike Medicines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/5a2f5a2c-e95c-45b8-ad44-f15c9351f9f1/content (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Bates, D.; Slight, S. Medication errors: What is their impact? Mayo Clin. Proc. 2014, 89, 1027–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.; Ng, H.; Leung, K.; Chan, K.; Chan, S.; Loy, C. Development of fine-grained pill identification algorithm using deep convolutional network. J. Biomed. Inform. 2017, 74, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ou, Y.; Tsai, A.; Zhou, X.; Wang, J. Automatic drug pills detection based on enhanced feature pyramid network and convolution neural networks. IET Comput. Vis. 2020, 14, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Huangfu, T.; Wu, L.; Chen, W. Comparison of RetinaNet, SSD, and YOLO v3 for real-time pill identification. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 2021, 21, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larios Delgado, N.; Usuyama, N.; Hall, A.; Hazen, R.; Ma, M.; Sahu, S.; Lundin, J. Fast and accurate medication identification. npj Digit. Med. 2019, 2, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, A.; Pham, H.; Trung, H.; Nguyen, Q.; Truong, T.; Nguyen, P. High accurate and explainable multi-pill detection framework with graph neural network-assisted multimodal data fusion. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0291865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- My, L.N.T.; Le, V.-T.; Vo, T.; Hoang, V.T. A comprehensive review of pill image recognition. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 82, 3693–3740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Ruan, J.; Zhang, W.; He, X.; Wu, W.; Yao, C. TextSnake: A flexible representation for detecting text of arbitrary shapes. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.01544. [Google Scholar]

- OpenMMLab. MMOCR. Available online: https://github.com/open-mmlab/mmocr (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Fang, S.; Xie, H.; Wang, Y.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, Y. read like humans: Autonomous, bidirectional and iterative language modeling for scene text recognition. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.06495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Library of Medicine (US). RxImage Dataset. Available online: https://datadiscovery.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Kwon, H.; Kim, H.; Lee, S. Pill detection model for medicine inspection based on deep learning. Chemosensors 2022, 10, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask R-CNN. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Park, E.; Kim, J.; Ihm, S. Combination pattern method using deep learning for pill classification. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G. YOLOv5. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- Lee, Y.; Park, U.; Jain, A.; Lee, S. Pill-ID: Matching and retrieval of drug pill images. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2012, 33, 904–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, D. Distinctive image features from scale-invariant keypoints. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2004, 60, 91–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, D. A completed modeling of local binary pattern operator for texture classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2010, 19, 1657–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Hussaeni, K.; Karamitsos, I.; Adewumi, E.; Amawi, R. CNN-based pill image recognition for retrieval systems. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canny, J. A computational approach to edge detection. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1986, 8, 679–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponte, E.; Amparo, X.; Huang, K.; Kwak, D. Automatic pill identification system based on deep learning and image preprocessing. In Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering, & Applied Computing (CSCE), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 24–27 July 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, C.; Sun, T.; Lin, M.; Gao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Liu, H.; et al. PaddleOCR 3.0 technical report. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.05595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntronsuk, S.; Ratanotayanon, S. Pill image binarization for detecting text imprints. In Proceedings of the 2016 13th International Joint Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (JCSSE), Khon Kaen, Thailand, 13–15 July 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Otsu, N. A threshold selection method from gray-level histograms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1979, 9, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R. An overview of the Tesseract OCR engine. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR 2007), Curitiba, Brazil, 23–26 September 2007; Volume 2, pp. 629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, J.; Kang, Y.; Lee, S.; Jeong, D.; Kim, K. An accurate deep learning-based system for automatic pill identification: Model development and validation. J. Med. Internet Res. 2023, 25, e41043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhivya, A.; Sundaresan, M. Tablet identification using support vector machine-based text recognition and error correction by enhanced n-grams algorithm. IET Image Process. 2020, 14, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Lv, T.; Chen, J.; Cui, L.; Lu, Y.; Florencio, D.; Zhang, C.; Li, Z.; Wei, F. TrOCR: Transformer-based optical character recognition with pre-trained models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.10282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluri, M.; Tatavarthi, U. Geometric deep learning for enhancing irregular scene text detection. Rev. D’intelligence Artif. 2024, 38, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional networks for biomedical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.; Welling, M. Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1609.02907. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y.; Dong, B.; Huang, K.; Ding, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, X.; Wang, Q. Scene text recognition via dual-path network with shape-driven attention alignment. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, N.; Haroon, F. Adaptive Gaussian and double thresholding for contour detection and character recognition of two-dimensional area using computer vision. Eng. Proc. 2023, 32, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Sauvola, J.; Pietikäinen, M. Adaptive document image binarization. Pattern Recognit. 2000, 33, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Qiu, J. Ultralytics YOLO11. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/ultralytics (accessed on 2 December 2025).

- JaidedAI. EasyOCR. Available online: https://github.com/JaidedAI/EasyOCR (accessed on 15 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.